Abstracts

Organizational theory has long emphasized the importance of contingent, environmental influences on organizational performance. Similarly, research has demonstrated the importance of local political culture and informal management on the performance of the local health system, establishing vicious and virtuous circles of influence that contribute to increasing inequalities in performance among decentralized local health systems. A longitudinal ethnography studied the relationship between these elements in the same rural municipality in Northeast Brazil after a four-year interval. The second study found the local health system performance much improved. Two main factors appear to have interacted to bring this about: leadership vision and power to implement of one individual; professionalization of the local health system by hiring a significant number of senior health staff. The origins of these influences combine initiatives at local, state and federal levels.

Sanitary reform; Public policies; Decentralization; Clientelism; Local government; Brazil

A teoria organizacional tem enfatizado por muito tempo a importância de influências contingentes e ambientais na performance e desempenho organizacional. Igualmente, pesquisas também demonstram a importância da cultura política local e de fatores informais na gerência e desempenho do sistema local de saúde, estabelecendo círculos viciosos e virtuosos que influenciam e contribuem para aumentar as desigualdades nos sistemas descentralizados da saúde. Com base em um estudo etnográfico longitudinal esta pesquisa buscou entender a inter-relação entre estes elementos em um município rural localizado no Nordeste do Brasil em um intervalo de quatro anos. No segundo momento da pesquisa foi constatado que o desempenho do sistema local de saúde tinha melhorado. Dois fatores principais parecem ter interagido para causar essa melhoria: a visão e o poder de liderança de um indivíduo; e a profissionalização do sistema local de saúde a partir da contratação de um número significativo de profissionais. As origens destes fatores podem ser encontradas nas esferas local, estadual e federal.

Reforma sanitária; Políticas públicas; Descentralização; Clientelismo; Governo local; Brasil

TEMAS LIVRES FREE THEMES

Performance of the local health system and contingent influences in Northeast-Brazil: breaking vicious and virtuous circles

Performance do sistema de saúde local e influências contingentes no Nordeste do Brasil: quebrando círculos viciosos e virtuosos

Regianne Leila Rolim MedeirosI; Sarah AtkinsonII

IUniversidade Estadual do Ceará, Centro de Humanidades, Departamento de História. Av. Paranjana 1700, Itaperi. 60.740-000 Fortaleza CE Brasil. regiannemedeiros@yahoo.com.br

IIDepartment of Geography, Durham University

ABSTRACT

Organizational theory has long emphasized the importance of contingent, environmental influences on organizational performance. Similarly, research has demonstrated the importance of local political culture and informal management on the performance of the local health system, establishing vicious and virtuous circles of influence that contribute to increasing inequalities in performance among decentralized local health systems. A longitudinal ethnography studied the relationship between these elements in the same rural municipality in Northeast Brazil after a four-year interval. The second study found the local health system performance much improved. Two main factors appear to have interacted to bring this about: leadership vision and power to implement of one individual; professionalization of the local health system by hiring a significant number of senior health staff. The origins of these influences combine initiatives at local, state and federal levels.

Key words: Sanitary reform, Public policies, Decentralization, Clientelism, Local government, Brazil

RESUMO

A teoria organizacional tem enfatizado por muito tempo a importância de influências contingentes e ambientais na performance e desempenho organizacional. Igualmente, pesquisas também demonstram a importância da cultura política local e de fatores informais na gerência e desempenho do sistema local de saúde, estabelecendo círculos viciosos e virtuosos que influenciam e contribuem para aumentar as desigualdades nos sistemas descentralizados da saúde. Com base em um estudo etnográfico longitudinal esta pesquisa buscou entender a inter-relação entre estes elementos em um município rural localizado no Nordeste do Brasil em um intervalo de quatro anos. No segundo momento da pesquisa foi constatado que o desempenho do sistema local de saúde tinha melhorado. Dois fatores principais parecem ter interagido para causar essa melhoria: a visão e o poder de liderança de um indivíduo; e a profissionalização do sistema local de saúde a partir da contratação de um número significativo de profissionais. As origens destes fatores podem ser encontradas nas esferas local, estadual e federal.

Palavras-chave: Reforma sanitária, Políticas públicas, Descentralização, Clientelismo, Governo local, Brasil

Introduction

The extensive literature on health sector or systems reform put out during the 'nineties has at its heart two questions with respect to change: first, what changes are needed and secondly how those changes can be effected. This paper addresses the second of these two questions with reference to health reform and changes in performance of one local health system in the Northeast of Brazil between 1996 and 2000. The question of what changes are needed is taken as a given in this study.

The political shift in Brazil in the mid-'eighties from military rule to democratic elections was accompanied by a new constitution and major reviews of public sector organisations. The review of the Brazilian health system resulted in a programme for reform based on four key principles: decentralisation; participation; unification (of the disparate parallel systems); universal access1. The driving factor behind this reform was the necessity to reorganize the national health system and overcome inequalities, linking democratization to the idea of health for all2.

Whilst much of the public wrangling around the reform agenda concerns payment schedules and the relationship with the large private sector, it is the policy for decentralisation that creates a rich research environment for exploring processes of change within an organisation. Decentralisation specifically gives space for decision-making and organisational structure to the local health system, which in the case of Brazil is the health system within a município, the third tier in the administrative structure (Federal, State, Município). The call for local determination of structure and process in health system management was a major element in the health reform movement during the years of military rule and can be seen to echo amongst other things a shift in management thinking seen around the same time in the 'sixties and 'seventies. A series of empirical studies on organisational form and performance demonstrated that different organisational forms suited different situations and became called the contingency approach3-5. Of particular relevance to a decentralised, local organisation is the work of contingency theorists that argued that organisational form should be contingent on the external, local environment of that organisation6. However, others have argued that this relationship is not one of simple determinism since all organisational forms are decided by people. The complex influences on purposeful human behaviour such as personal and group interests or local and organisational cultures need to be incorporated into understanding the relationships between organisations and their environments7,8.

These themes of the formal organisational structures, the contingent environment and the role of human agency found in debates in management theory are the themes explored through the empirical study presented here in order to contribute to addressing the question of how changes can be effected. The vast majority of work made on organisational change and management has been in the private business sector rather than the public service sector and located in the industrialised or developed countries of North America, Europe, Australia and Japan. Some explorations of the influence of different cultures in terms of values, acceptable patterns of behaviour and management roles have been made, again mainly in the private, business sector, such as Geert Hofstede's study on variations in work practices within IBM in different countries9,10. Our study, based on located the public health sector in Ceará, in the Northeast Brazil, provides a contribution towards expanding the coverage of empirical work taking a contingency type approach to study change in organisational performance.

The Contingent Local Environment, Northeast Brazil

An exploration of the influence of the contingent environment on the functioning of the local health system needs to be placed within the relevant contemporary debates on social relations in Brazil. These debates hinge around the legacy of so-called traditional relations within modernity11-13.

A common view is that traditional oligarchic elites and the importance of clientelism are in decline in contemporary Brazil as a result of the increasing process of industrialisation associated with changing relationships of production12, the acceleration of economic growth during the 'seventies14,15 and the intensification of social movements and social awareness during the 'eighties16. However, this view is contested. Some analysts argue that the economic modernisation programme of the military government was dependent on the support of local elites for implementation and in turn reaffirmed their oligarchic power17. Moreover, while the local landholding patriarch of a predominantly agrarian economy may be something of the past, the importance of clientelistic relationships may persist in new forms18,19 and co-exist with the new economic forms of industrialisation and liberalism. While social movements have been important in articulating new demands, their organisation has not been sufficient to revolutionise Brazilian social structure. There is greater agreement that any undermining of patron-client relationships has been much slower in the Northeast of Brazil, still largely structured around large landholdings, with this social system explicitly predominant at both local município and the regional state levels well into the 'eighties.

However, since the 'eighties, major social and economic changes have occurred in Ceará combining agrarian land reforms and a great expansion of the industrial sector. In Ceará, a new political alliance made up of business entrepreneurs won the state government elections in 1986 and identified themselves with words such as modernisation, efficiency and took as one of their slogans, 'the fight for the end of coronelismo'20-22. This group has now won four consecutive elections for control of the state government covering 16 years up to and including the present. This situation has led to the suggestion that Ceará may have become an exception to the traditional image of the Northeast15. Others remain sceptical23.

In 1996, we made partial ethnographies of three local health systems and their social and political environments in the state of Ceará to explore variation in health system performance and the role of local social and political factors through a comparative analysis. The findings suggested that the influence of the local history of social relationships and local cultures of political management were by far the most important influences on whether the local health system worked well or not under decentralisation24,25. The results echoed Robert Putnam's26 work over twenty years on local government in Italy in which he concludes that the types of social relationships (often termed social capital) historically developed in a local district determine whether a local government will work well or not and that districts are tied onto these trajectories such that some districts will benefit from being given greater autonomy while others will do badly. These results present a depressing picture of districts trapped into an historical trajectory and also imply that some districts should not be ceded decentralised status. But our study had only compared across geographical location; we decided to return to the worst performing of the three municípios four years later, in 2000, to add in a comparative dimension of time in order to explore the processes by which continuity or change occur.

Methods

The município selected for the case studies was Caridade in Ceará. The case study município was selected through consultation with colleagues at the Escola de Saúde Pública, Ceará (the Public Health School of Ceará) to represent a site typical of the poor, rural municípios located in the dry, interior regions of Ceará called the Sertões.

The study is based on empirical work using data generated through ethnographic approach. Ethnography can be considered as a means to discover what people understand of their social world and how they define and evaluate things27-28. Therefore, ethnography is highly appropriated methodoly for building an account that describes and interprets the interaction of health system with the social and political characteristics of the local context.

In both time periods, 1996 and 2000, one of the authors lived in Caridade: for fourteen months from February, 1996 to February, 1997 and for six months from January to June, 2000. The first period of field study work is substantially longer since by the second period the author was already well known and accepted in the município, had a good knowledge of the less overt relationships between people there and knew what issues to focus on for the research. A space of four years was the ideal comparative time frame since local governments hold power for four years and both study periods covered the build up to local government elections, a time when relationships of patronage and other personal links become more overt29.

The starting point of the analysis was a comparison of the performance of the health system in Caridade in 1996 and 2000, including an evaluation by the population. This in turn indicates what change or continuity there is to be explained. Potential explanatory information was collected on the formal inputs, organisation and procedures of the health system, the informal aspects of management style and how procedures were really carried out and the wider influences of the contingent local political culture or environment within which the health system was embedded.

The author kept an ethnographic diary in both periods of fieldwork in which informal methods of data collection such as observations, attendance at meetings, conversations and so forth were recorded on a daily basis. More formal data collection was made through open interviews, usually tape recorded and transcribed and from official documents, reports and statistics. All qualitative data from the diary and interviews were coded into topics using the QSR Nud*ist software package for ease of storage, retrieval and cross-referencing30-33.

In 1999, the population of Caridade was 14,665 in an area of 791.70 Km2 indicating a population dispersed across a large area. In 1958, Caridade was granted the status of município. Since then two main families have dominated the political scene; all prefects have belonged or had affiliation to one of these families. In the more rural areas of the municipality, people still live mainly from cattle-rearing and subsistence agriculture.

The health system in 1996 comprised a Unidade Mista (which is a small hospital that offers out-patient and in-patient care. It is more often found in the rural areas, especially in North, Northeast and Middle West regions of Brazil), a health centre, and four health posts. In 2000 the health system was similar to that of 1996, but one new health post was built.

Results

Heath system organisation and performance, 1996-2000

Comparing health system performance in both periods of study, a difference emerges. In 2000, the health system demonstrates significant improvement, and despite the challenges of providing health care in remote rural areas, the population had more reliable services. The improvements found can be seen in terms of availability, accessibility and quality.

Availability of infrastructure

The network of physical health facilities had been increased slightly with the creation of one more basic health post. In addition, two of the existing health posts had been renovated and expanded in size and capacity. A list of facilities and services offered at each for 1996 and 2000 is given in Chart 1.

Accessibility to care

Although the network had been slightly increased, the really dramatic improvement in both availability and accessibility had come from the introduction of a programme of Family Health Teams. These are mobile teams comprising a physician, a nurse, auxiliary and community health worker that are based at one of the health posts but visit other localities on a fixed schedule. This meant that once a week at least, a team was operating at a locality more accessible for the scattered population than the sites of the four health posts or the town centre. This model of health care provision seems to offer a feasible way to extend accessibility for rural populations.

A second cornerstone of an accessible system of health care provision in rural areas is an effective transport network such that patients brought to basic facilities or mobile teams needing more specialised care can be transferred to a hospital relatively easily. While the number of ambulances remained the same in the two time periods, in 2000 they were all well maintained, on the road and being used properly for their medical purposes, which had not been the case in 1996.

Quality of care

While there has been a new post built, two upgraded and the introduction of the Family Health Teams, the most important difference between 1996 and 2000 was that the health posts were functioning as they are supposed to. In 1996, two of the health posts were effectively shut and the other two had very little activity at them. Physicians and nurses due to work at the posts on given days of the week would be late or not come at all. They in turn were not paid their salaries on time, or even at all, and had little motivation to work well. The population most often resorted to local political councillors to access transport to the town centre hospital or to get drugs which the councillors would keep at their homes.

When the Family Health Programme Teams were first implemented, they too did not work all that well. But by 2000, the population was much happier with the health care in the município and the most important factors were the good working of the health posts and the Family Health Programme.

A summary of the issues most often commented on by members of the population is given for 1996 and for 2000 in Chart 2. The predominance of negative comments in 1996 changes to a much more positive picture by 2000.

While the local health system in Caridade is still relatively impoverished compared with other places, there have been big improvements in the availability, accessibility and quality of health care provided from 1996 to 2000. This apparent gain in a município which had very poorly run services in 1996 seems to be encouraging and leads to the question as to what factors have contributed to why and how these changes have been brought about.

Formal and informal processes influencing health system performance

There have been increases in the formal inputs into the health system. Financial resources were assured from the local government at 15%. Investment had been made into renovation and refurbishment of health facilities and one new health post had been added to the network. However, many of these observed increased inputs officially should have also been available in 1996. The main difference seen between 1996 and 2000 is not so much an increase in resources but the realisation of resource commitments. Health facilities and the ambulances were functioning as they were supposed to be functioning in 1996 but were not. New inputs came mainly from contracting into the Federally funded Family Health Programme which provides the finance needed to support a number of senior health professionals to work full-time in the município. So the question then is why was the local government more supportive to implementing health care provision according to the system's potential in 2000 as opposed to the neglect seen in 1996?

The municipal health system has always served as an important resource in local struggles for political power. As the most visible aspect of the system, the hospital became the main focus of any investment in health care and the health posts were largely neglected. In addition, local politicians or candidates kept medicines, other supplies and the local ambulances at their homes to distribute to those in need in return for political support. In this way, the provision of health care in Caridade up to 1996 was seen by all as a favour to be bestowed rather than a right of the population.

The local health system at this time had absolutely no control over any of its own resources. On paper, the management structure comprised a Municipal Health Secretary and a local health council with 50% lay representation, supposed to be the main decision-making body. In practice, the local government kept control over the financial and other material resources and thus the Health Secretariat had no control over anything except the day-to-day work-plans of the community health workers.

The relationship between the local health system, the local government and the political culture has been characterised as seamless integration 24, indicating that no boundary exists between health system and local politics. The new government taking up power at the beginning of 1997 came in on a political mandate to improve public services including health. Thus investing in visible inputs and improvements in the network of health facilities was a necessary activity. However, while improvements began to be seen, the municipal health system was still completely under the management of the local government rather than empowered to make its own decisions and manage its own resources. Key positions in the health system were held by family members of the prefect and local politicians retained access to health related resources to distribute as favours.

Initiatives were made to contract to Federal programmes offering resources to support specific kinds of activities, such as the Family Health Programme. However, this programme did not work well until 1999. Thus, in the first two years of the new government, although the provision of health care showed some improvements, the health system remained seamlessly integrated into the local political culture and as such remained vulnerable to the vagaries of politics and political commitment.

In 1999, a major change occurred in the formal organisation of the health system, which gave the Secretariat autonomy to manage its own resources and activities. Recognisable management procedures had been put into place in terms of staff meetings and local community meetings. Teams at the health posts were given some autonomy to manage activities for their area. The Family Health Programme teams were working well and both health staff and the population recognised a significant improvement in health care provision.

Nonetheless, the impetus for this reorganisation again comes from the political sphere. The management of the local health system was given to a business man who was also influential in the government political party and who was seeking to increase his political profile with the population. This person was able to demand control of the local health system because of his power as financier of the incumbent prefect's political campaigns and also possibly due to inside knowledge of irregularities in financial management procedures. On taking over the health sector, he restructured it creating a new position for himself, that of General Coordinator and appointed as the new Secretary of Health someone who was a business manager by background rather than a physician (and with no family ties with the local administration). Although the General Coordinator's wish for control of the health system is seen as predominantly politically motivated, equally important to his impact on the performance of the health system is the experience in management that he brought to the task. Indeed, his political ambitions did not overrule his professional management views. He was prepared to make political enemies in the interests of the best functioning of the health system. One of the people he replaced in the overhaul of the local health system was the director of the hospital, a nurse who was a cousin of the prefect and member of an influential branch of that family, indeed one with whom the General Coordinator himself had close social affiliations. The nurse was popular locally and there was a major outcry when she was sacked. The General Coordinator took this step because, although she was a good nurse, in his opinion she was not a good manager.

Thus, this one person had a critical influence on the performance of the health system through his personal power to act to reorganise the health system combined with his management vision. Nonetheless, there are other forces at work here that contribute to improving the performance of the health system. The effective management since the General Coordinator took control has meant that the Family Health Programme was working well. The introduction into the município of senior health professionals disrupts the dynamic of traditional relationships of clientelism and favour locally. The professional culture and social status of the physicians and nurses make them unlikely to accept interference from local politicians in their management of the district health care facilities and resources.

Explicit examples of conflict between the old ways and the new abound, but what was clear was that in just a short time, the influence of this professional group had been significant in this respect.

This was reflected in the population's evaluations of health care; that they feel much more that they have a right to seek care rather than having to ask for it as a favour.

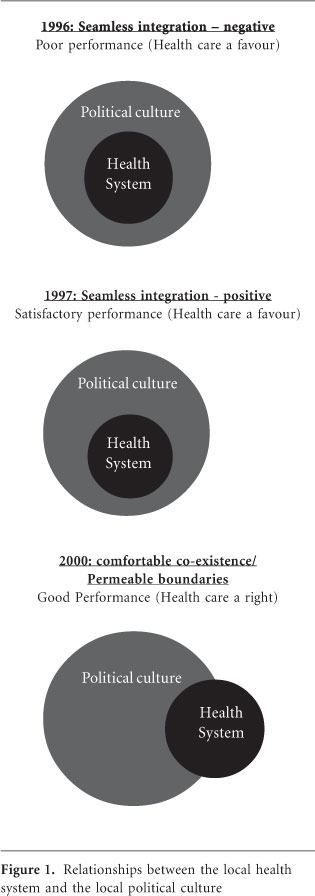

In summary, the comparative analysis of the formal and informal aspects of the local health system operations in 1996 and 2000 identify three different sets of relationships between the local political culture and the local health system, each influencing the performance of the local health system differently. In 1996, the health system is subsumed within the political culture with negative effects on its performance. This is termed seamless integration. In 1997, the health system is performing much better but is still seamlessly integrated with local political culture. However, by 2000, a boundary has been established between the political culture and the health system allowing autonomy to the running of the health system. This boundary is nonetheless highly permeable but the relationship with both local government and the local political culture is more one of a positive synergy rather than seamlessly integrated. These relationships are depicted in Figure 1. The improved performance in health care provision in Caridade between 1996 and 2000 is thus associated with two key changes in the informal aspects of local political dynamics: the creation of a boundary, albeit still a highly permeable one, between local politics and the municipal health system; the undermining of patron-client relationships such that health care becomes more of a right than a favour. These aspects in turn are brought about by the actions of a powerful person with a particular vision, indicating the importance of leadership in local health systems, and the disruption to the local dynamics of social and political relations caused by the introduction of a professional cadre.

Discussion

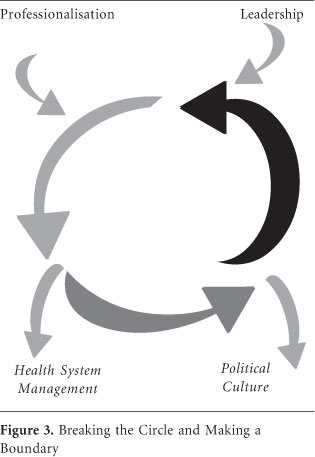

The interactions depicted in Figure 1 between local political culture, local health system management and performance can be seen also as forming vicious and virtuous circles of influence in 1996 and 1997. The joint influences of leadership and professionalisation serve to break these circles by creating a boundary. This more dynamic view of the research results are visualised in Figures 2 and 3.

The implementation of decentralised health systems always risks becoming caught up in spiralling circles of influence, for good or for bad, virtuous or vicious. In the context of Northeast Brazil, the drawbacks of the virtuous form are in part the system's vulnerability to a change in government and in part the system's tendency to project the attitude of health care as a favour. The operation of these circles and the relationship of seamless integration between the local health system and its embedding political culture echo the work of Robert Putnam 26 in Italy over twenty years where similar influences of the trajectories of local history and social relations were documented to be the predominant determinants on local government performance. The research reported here presents a rather more optimistic outlook for health system development. Not only is a notable improvement in local health system performance found between the two time periods and not only are these time periods separated by a relatively short time of four years, but also the pervasive influence of traditional clientelistic relations of local political culture have been undermined and some element of a boundary established between the two spheres. This would seem to be a highly interesting finding for those engaged in health systems development and the source of the influences and the implications for policy-makers are explored further in this section.

Decentralisation raises questions related to the importance of different levels or scales of government. Recently, some authors have been discussing the importance of intergovernmental relations and federative coordination of health34, understanding that municípios are not isolated entities and to succeed in their process of reform need to compromise with different levels outside municipality borders35. The findings from Caridade show that the influence for health care improvement comes from three main sources. One is the role of the Federal government in promoting a particular model of health care, giving value to primary health care and to a family health care model by investing in them and giving the municípios capacity to implement health programmes. The support of the Federal government to this model of health care is especially important for rural municípios that are dependent on the Federal level of government for sources of revenue. This support provides the financial resources to bring a critical mass of senior health staff to the municípios. These professionals in turn bring their own culture of practice and the critical mass engenders peer pressure to perform according to this culture. In addition, the full-time employment and residency in the municipality means that the professionals develop a commitment to place. The second source of influence comes from the State level of government. The State of Ceará strongly supports the municípios in the implementation of programmes, particularly contributing technical support, training and capacity building of professionals. For example, the State offers the opportunity to take a specialisation course in Family Health Care, which gives status to this as a choice of career, which is proving particularly attractive for nurses.

However, the incentives and support from the Federal and State governments were shown not to be sufficient to fully promote improvements. In 1996 the Prefect did not bother to exploit the opportunities offered to support primary health care by the Federal government, and from 1997 to 1999 programmes such as the Family Health Programme were implemented but not working properly. The additional factor needed to promote improvements was the local capacity to manage the health system. The third influence comes then from the local level. From the dynamics of local politics, a leadership figure emerged. This is an individual who along with local power and political interests, comes with personal experience and training in management that contributes to the reorganisation of the health system in the municipality.

The joint action of the Federal government and the local management capacity contribute to break the vicious and virtuous circles established traditionally between the management of the health system and the local political culture. Breaking these circles acts to raise the population's expectations even further, especially after the introduction of the senior health professionals. The intended objectives of the Family Health Programme Teams may be to provide better health care to rural municípios, but the teams gradually create their own relationships locally with the population and the health system. This new set of relationships contributes both to moving the management of the health system onto a different trajectory, away from the spiralling circles of mutually reinforcing behaviours and to undermining traditional local clientelism by establishing a boundary between the health system and the local political culture where health care is now seen as a right rather than a favour.

The results of the research have important policy implications for the management of local rural health systems in terms of the potential actions at different scales in a decentralised health system to improve local performance. The Federal scale can influence the process through incentives and commitment to a model of health care that benefits rural populations. Although this commitment is not enough to ensure change, it is an important incentive in driving small and poor municípios along a defined reform path. The local scale with the specific personality of the leadership then becomes an important issue and raises the question of whether and how this might be replicated in other places. The power base of the leadership cannot be replicated and controlled by the other levels of government. However, as much as the power base, the different vision of management was determinant in the improvements that occurred. This indicates the potential for targeted training in a management culture towards not only local health managers but also the natural local leaders at the decentralised local government scale. Providing this training is a role that can be well taken on by the State scale.

With respect to the role of the population, although it did not play a direct role in promoting an improved health system performance, their action through the ballot box, demonstrating disappointment with the outgoing Prefect in 1996 was important in determining the inputs made to rehabilitate and staff the local health system under the new government. The expressed importance of service provision to the population also made the management of the health sector an attractive arena for the General Coordinator to take over in order to raise his political profile locally. Nonetheless, direct influence from the population is still very limited.

The study of change in the health system performance in Caridade has thus provided an optimistic example of the potential for formal inputs from Federal, State and local scales to disrupt established informal relations of political culture that can dominate the management of local health systems and thereby break the circularity of influence between these. The Caridade case study raises three broader considerations on which to end.

First, most models for policy implementation build on the role of personal or group interests36-39. Here, although the General Coordinator is motivated in part by personal political interests, this is not a sufficient explanation for his actions. Thus, the role of values or vision held by key actors is as important an element in explanation as motivation based on personal gain. Research on policy implementation or management tends to have given relatively little weight or in-depth attention to the influence of values or vision, the source of these or ways in which these are disseminated.

Secondly, it is almost an orthodoxy in current development literature that local networks of social association are a positive force, sometimes viewed as social capital40-42. In the Northeast of Brazil, some aspects of these traditional patterns of social relationships are recognised as more ambiguous in their benefit. Whilst the running of the decentralised health system in Caridade remained totally enmeshed within the traditional practices based on personalised, kin and clientelistic connections, the health system performed either poorly or precariously. Only once various forces have undermined the influence of these traditional relationships, at least within the health system, and established alternative ways of working does the health system really start to show substantial and potentially sustainable improvement. Thus, an assumption that local social relations are a good basis for development practice makes far too simplistic a starting point.

Thirdly, much of medical sociology has provided a critique of the autonomy and culture of medical professionals both on systems management grounds such as cost containment43-45 and on moral or ethical grounds with respect to vested interests46,47. The results here indicate an alternative viewpoint. In Caridade, the introduction into the local social interactions of a critical mass of senior health professionals has been one of the key factors that created the distance or boundary between the local health system and the local political culture. As a final comment therefore, the research has indicated the importance of exploring the local meanings and expression of commonly used conceptual categories, such as interests, social capital and professionalisation, for organisations located in their specific contingent settings through detailed empirical study.

Collaborations

RLR. Medeiros did the field research and worked on the organization, data analysis and theoretical conception of this paper. S Atkinson worked on the organization, data analysis and theoretical conception of this paper.

Acknowledgements

The first stage of research was funded by the Department for International Development (UK) and the second stage through studentships for a doctoral study from the Overseas Research Studentship - ORS and the University of Manchester.

Artigo apresentado em: 08/05/2009

Artigo aprovado em: 08/07/2009

Versão final: 20/07/2009

- 1. Carvalho GI, Santos L. Sistema único de saúde São Paulo: Hucitec; 1995.

- 2. Fleury S. Reforma sanitária brasileira: dilemas entre o instituinte e o instituído. Cien Saude Colet 2009; 14(3):743-752.

- 3. Woodward J. Industrial organization: theory and practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1965.

- 4. Perrow C. Organizational analysis: a sociological view. London: Tavistock; 1967.

- 5. Lawrence PR, Lorsch JW. Organization and environment Boston: Harvard University Press; 1967.

- 6. Burns T, Stalker GM. The management of innovation Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1961.

- 7. Trice HM, Beyer JM. Studying organizational cultures through rites and rituals. Academy of Management Review 1984; 9(4):653-669.

- 8. Drucker PF. The futures that have already happened. The Economist 1989; 21:27-30.

- 9. Hofstede G. Culture's consequences: international differences in work-related values. Newbury Park: Sage; 1980.

- 10. Hofstede G. Cultures and organizations: software of the mind. London: McGraw-Hill; 1991.

- 11. Faoro R. Os donos do poder: formação do patronato político brasileiro. 9th Edition. São Paulo: Globo; 1991.

- 12. Queiroz MIP. O mandonismo local na vida política brasileira e outros ensaios São Paulo: Alfa-Omega; 1976.

- 13. Leal VN. Coronelismo: the municipality and representative government in Brazil. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1977.

- 14. Roett R. Brazil: Politics in a patrimonial society. 3th Edition. New York: Praeger; 1984.

- 15. Hogopian F. Traditional politics and regime change in Brazil New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996.

- 16. Baierle SG. The explosion of experience: the emergence of a new ethical-political principle in popular movements in Porto Alegre, Brazil. In: Alvarez SE, Dagnino E, Escobar A, editors. Cultures of politics, politics of culture Colorado: Westview Press; 1998. p. 118-138.

- 17. Bursztyn M. O Poder dos donos: planejamento e clientelismo no nordeste. Petrópolis: Vozes; 1985.

- 18. Barreira, C. Velhas e novas práticas do mandonismo local: um diálogo com Maria Isaura Pereira de Queiroz. Revista de Ciências Sociais 1999; 30(1/2):37-43.

- 19. DaMatta R. For an anthropology of Brazilian tradition or 'a virtude está no meio. In: Hess DJ, DaMatta R, editors. The Brazilian puzzle: culture on the borderlands of the western world. New York: Columbia University Press; 1995. p. 270-291.

- 20. Carvalho RMV. Voto rural e movimentos sociais no Ceará: sinais de ruptura nas formas tradicionais de dominação? Fortaleza: NEPS, UFC: 1990.

- 21. Parente JC. Construindo a hegemonia burguesa: as eleições municipais de 1988 no Ceará. Fortaleza: NEPS, UFC; 1992.

- 22. Teixeira FJS. CIC: a 'razão esclarecida' da FIEC. Fortaleza: IMOPEC; 1995.

- 23. Beserra BR. Clientelismo e modernidade: o caso do Programa de Reforma Agrária no governo Tasso Jereissati. Fortaleza: NEPS, UFC; 1994.

- 24. Atkinson S, Medeiros RLR, Oliveira PHL, Almeida RD. Going down to the local: incorporating social organisation and political culture into assessments of decentralised health care. Social Science and Medicine 2000; 51(4):619-636.

- 25. Atkinson S. Political cultures, health systems and health policy. Social Science and Medicine 2002; 55(1):113-124.

- 26. Putnam RD. Making democracy work: civic traditions in modern Italy. New Jersey: Princeton University Press; 1993.

- 27. Hammersley M, Atkinson P. Ethnography: principles in practice. 2nd Edition. London: Routledge; 1995.

- 28. Wolcott HF. Ethnography, a way of seeing Walnut Creek: Altamira Press; 1999.

- 29. Medeiros RLR. Influences for change across the boundary between the local health system and the local political culture [thesis] Manchester: University of Manchester; 2002.

- 30. Coffey A, Atkinson P. Making sense of qualitative data London: Sage; 1996.

- 31. Silverman D. Interpreting qualitative data: methods for analyzing talk, text and interaction. London: Sage; 1993.

- 32. Gahan C, Hannibal M. Doing qualitative research using QSR NUD*IST London: Sage; 1998.

-

33QSR NUD*IST: Software for qualitative data analysis, user guide. 2nd Edition. London: Sage; 1997.

- 34. Viana ALA, Machado CV. Descentralização e coordenação federativa: a experiência brasileira na saúde. Cien Saude Colet 2009; 14(3):807-817.

- 35. Campos CEA. O desafio da integralidade segundo as perspectivas da vigilância da saúde e da saúde da família. Cien Saude Colet 2003; 8(2):569-584.

- 36. Grindle MS, Thomas JW. Public choices and policy change Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press; 1991.

- 37. Ham C, Hill M. The policy process in the modern capitalist state 2nd Edition. London: Harvester Wheatsheaf; 1993.

- 38. Hill M. New agendas in the study of the policy process London: Harvester Wheatsheaf; 1993.

- 39. Barker C. The health care policy process London: Sage; 1996.

- 40. Ostrom E. Crossing the great divide: coproduction, synergy and development. World Development 1996; 24(6):1073-1087.

- 41. Evans P. Government action, social capital and development: reviewing the evidence on synergy. World Development 1996; 24(6):1119-1132.

- 42. Heller P. Social capital as a product of class mobilization and state intervention: industrial workers in Kerala, India. World Development 1996; 24(6):1055-1071.

- 43. Horner JS. Autonomy in the medical profession in the United Kingdom - and historical perspective. Theor Med Bioeth 2000; 21(5):409-423.

- 44. Nys H, Schotsman S. Professional autonomy in Belgium. Theor Med Bioeth 2000; 21(5):425-439.

- 45. Sacchini D, Antico L. The professional autonomy of the medical doctor in Italy. Theor Med Bioeth 2000; 21(5):441-456.

- 46. Freidson E. Profession of medicine. A study of the sociology of applied knowledge. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1988.

- 47. Dupuis HM. Professional autonomy: a stumbling block for good medical practice. An analysis and interpretation. Theor Med Bioeth 2000; 21(5):493-502.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

09 May 2013 -

Date of issue

Nov 2013

History

-

Received

08 May 2009 -

Accepted

20 July 2009 -

Reviewed

08 July 2009