Abstract

BACKGROUND: Atypical spinal tuberculosis (TB) usually presents in a slowly indolent manner with nonspecific clinical presentations making the diagnosis a great challenge for physicians. New technologies for the detection of atypical spinal TB are urgently needed. The aim of this study was to assess the diagnostic value of an enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay in clinically suspected cases of atypical spinal TB in China. METHODS: From March 2011 to September 2012, a total of 65 patients with suspected atypical spinal TB were enrolled. In addition to conventional tests for TB, we used ELISPOT assays to measure the IFN-I response to ESAT-γ and CFP-10 in T-cells in samples of peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Patients with suspected atypical spinal TB were classified by diagnostic category. Data on clinical characteristics of the patients and conventional laboratory results were collected. RESULTS: Out of 65 patients, 4 were excluded from the study. 18 (29.5%) subjects had cultureconfirmed TB, 11 (18.0%) subjects had probable TB, and the remaining 32 (52.5%) subjects did not have TB. Generally, the features of atypical spinal TB include the following aspects: (1) worm-eaten destruction of vertebral endplate; (2) destruction of centricity of the vertebral body or concentric collapse of vertebral body; (3) tuberculous abscess with no identifiable osseous lesion; (4) contiguous or skipped vertebral body destruction. 26 patients with atypical spinal TB had available biopsy or surgical specimens for histopathologic examination and 23 (88.5%) specimens had pathologic features consistent with TB infection. The sensitivities of the PPD skin test and ELISPOT assay for atypical spinal TB were 58.6% and 82.8%, and their specificities were 59.4% and 81.3%, respectively. Malnutrition and age were associated with ELISPOT positivity in atypical spinal TB patients. CONCLUSIONS: The ELISPOT assay is a useful adjunct to current tests for diagnosis of atypical spinal TB.

Atypical spinal tuberculosis; Enzyme-linked immunospot assay; T-SPOT.TB kit; Diagnosis

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Evaluation of an enzyme-linked immunospot assay for the immunodiagnosis of atypical spinal tuberculosis (atypical clinical presentation/atypical radiographic presentation) in China

Kai YuanI; Zhao-ming ZhongI; Qiang ZhangII; Shu-chai XuIII; Jian-ting ChenI,* * Corresponding author at: Department of Spinal Surgery, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, 1838 North Guangzhou Avenue, Guangzhou, 510515, China. E-mail address: chenjt99@yahoo.cn (J.-t. Chen).

IDepartment of Spinal Surgery, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, China

IIDepartment of Orthopedics, Guangzhou Thoracic Hospital, China

IIIDepartment of Orthopaedices, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Traditional Chinese Medicine University, China

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Atypical spinal tuberculosis (TB) usually presents in a slowly indolent manner with nonspecific clinical presentations making the diagnosis a great challenge for physicians. New technologies for the detection of atypical spinal TB are urgently needed. The aim of this study was to assess the diagnostic value of an enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay in clinically suspected cases of atypical spinal TB in China.

METHODS: From March 2011 to September 2012, a total of 65 patients with suspected atypical spinal TB were enrolled. In addition to conventional tests for TB, we used ELISPOT assays to measure the IFN-I response to ESAT-γ and CFP-10 in T-cells in samples of peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Patients with suspected atypical spinal TB were classified by diagnostic category. Data on clinical characteristics of the patients and conventional laboratory results were collected.

RESULTS: Out of 65 patients, 4 were excluded from the study. 18 (29.5%) subjects had cultureconfirmed TB, 11 (18.0%) subjects had probable TB, and the remaining 32 (52.5%) subjects did not have TB. Generally, the features of atypical spinal TB include the following aspects: (1) worm-eaten destruction of vertebral endplate; (2) destruction of centricity of the vertebral body or concentric collapse of vertebral body; (3) tuberculous abscess with no identifiable osseous lesion; (4) contiguous or skipped vertebral body destruction. 26 patients with atypical spinal TB had available biopsy or surgical specimens for histopathologic examination and 23 (88.5%) specimens had pathologic features consistent with TB infection. The sensitivities of the PPD skin test and ELISPOT assay for atypical spinal TB were 58.6% and 82.8%, and their specificities were 59.4% and 81.3%, respectively. Malnutrition and age were associated with ELISPOT positivity in atypical spinal TB patients.

CONCLUSIONS: The ELISPOT assay is a useful adjunct to current tests for diagnosis of atypical spinal TB.

Keywords: Atypical spinal tuberculosis, Enzyme-linked immunospot assay, T-SPOT.TB kit, Diagnosis.

Introduction

Spinal tuberculosis (TB) has been an important public health issue, having serious medical, social and financial impacts, especially in developing countries.1 Skeletal TB occurs in 10% of extrapulmonary manifestations, of which spinal TB accounts for approximately 50%.2,3 The typical clinical presentation of a patient with spinal TB is back pain, kyphotic deformity, and in some cases a cold abscess.4 On plain radiographs, the classical spinal TB affected anterior aspect of the vertebral body as well as the disk leading to destruction of adjacent vertebral bodies, intervertebral disk and even soft tissues.5 However, a small number of cases do not have the typical characteristics of spinal TB. Atypical spinal tuberculosis can be classified into atypical radiographic presentation and atypical clinical presentation.4 Actually, these kinds of atypical spinal TB are a great challenge to physicians because of the nonspecific and wide spectrum of clinical presentations that result in delay of diagnosis and risk of significant potential morbidity and mortality due to several complications. Early diagnosis and treatment is the key to avoiding this long-term disability.6,7 Therefore, we urgently need a faster, more sensitive, and specific test for the diagnosis of atypical spinal TB in clinical practice.

Recently, an enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay using pools of early secretory antigenic target 6 (ESAT-γ) and culture filtrate protein 10 (CFP-10) peptides was manufactured and commercialized (Oxford Immunotec, Oxford, UK).8 It is based on the detection of interferon-gamma (IFN-I) released by activated T lymphocytes. The stimulants used, ESAT-6 and CFP-10 peptides, are located within the region of difference 1 (RD1) of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium bovis genomes, but is absent from all strains of M. bovis BCG, as well as from most NTM.9,10 The ELISPOT assay has been demonstrated to be useful for the diagnosis of skeletal TB.11,12 However, few studies have investigated the sensitivity and specificity of this assay for diagnosing atypical spinal TB. The aim of this study was to assess the diagnostic value of the ELISPOT assay in clinically suspected cases of atypical spinal TB.

Materias and methods

Setting and patients

This study was simultaneously conducted at three academic hospitals (Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, an 1800-bed medical center in southern China; Guangzhou thoracic hospital, a 600-bed medical center in southern China; and Guangdong hospital of traditional Chinese medicine, a 2000-bed medical center in southern China). The study protocol adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University. Patients were informed verbally and in writing of the potential benefits and risks of the study, and all patients signed an informed consent. After written consent had been obtained, all patients with suspected atypical spinal TB were prospectively enrolled from March 2011 to September 2012. Data on clinical characteristics of the patients and conventional laboratory results were collected. All cases were independently classified by three of the study investigators (Qiang Zhang, Shuchai Xu and Jianting Chen) who were blinded to the results of the ELISPOT assay. Classification was based on clinical, histopathological, radiological, and microbiological information. Atypical spinal TB had been classified into atypical radiographic presentation and atypical clinical presentation according to the criteria as follows4: (1) single vertebral disease; (2) multiple vertebral disease; (3) presentation as prolapsed intervertebral disk or failed back syndrome; (4) cold abscess without obvious bony lesion; (5) tubercular granulomas. Exclusion criteria: eliminating spinal TB patients with the typical presentation (lesion affecting the anterior part of two or more continuous vertebral levels and causes narrowing of the adjacent disk space and bone destruction).5 All patients were finally deemed to have confirmed tuberculosis if the clinical specimens on culture was positive for M. tuberculosis. Patients were classified as having probable TB if histopathological findings of a biopsy specimen were consistent with the diagnosis of TB infection (granulomatous inflammation and/or caseating necrosis) and if they responded clinically and radiologically to a full course of anti-TB treatment, or as not having TB if another diagnosis was made or if there was clinical improvement without anti-TB therapy.13-15

Laboratory procedures and histopathology

Microbiologic and pathologic specimens for diagnosing atypical spinal TB were processed by standard techniques and procedures. In brief, mycobacteria were cultured on solid culture medium. Smears of decontaminated specimens were stained with the Ziehl-Neelsen stain and examined for acidfast bacilli (AFB). The culture showing AFB was identified as M. tuberculosis complex with a commercial DNA probe (AccuProbe Mycobacterium complex culture identification kit; GenProbe; San Diego, CA). If the AccuProbe assay was negative, cultures were identified with a commercially available PCR test for NTM (Gaoteng, Nanchang, China). For histopathological examination, formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue blocks of biopsied specimens were stained with hematoxylin-eosin stain.

Blood ELISPOT assays

The ELISPOT assays (T-SPOT.TB; Oxford Immunotec Ltd.) were performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations. 4-5 ml of venous blood samples taken from the study participants in heparinized glass tubes, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated and quantified at second day after the patients went into hospital. Briefly, 250,000 PBMCs were plated for 18 h on 96-well plates, which had been pre-coated with a mouse anti-human IFN-γ antibody per well. The cells were left unstimulated (negative control) or were stimulated with 50 µl PHA (positive control), with 50 µl ESAT-6 and CFP-10 peptides in separate wells. The response of stimulated cultures was considered positive when one or both test wells contained at least six more spots than the negative control wells or had at least twice as many as spot-forming cells (SFC) as the negative control wells. The number of SFC in each well was automatically counted with a CTL-ImmunoSpot® S5 Versa Analyzer (Cellular Technology Ltd., USA).

PPD skin test and serological(antibody detection) test

PPD produced from M. tuberculosis (50 IU/ml) was purchased from Guangzhou Longcheng Technology Inc., China. All patients with suspected atypical spinal TB were injected intradermally in the left forearm with 0.1 ml of 5 IU PPD (Mantoux technique) after extraction of blood for the ELISPOT assay. The diameters of both axes of skin induration were measured and recorded by a certified doctor 72 h after antigen injection. Results were expressed as the mean of the diameter of induration in millimeters. A positive result was defined as an induration >5 mm in diameter. Serological (antibody detection) test for atypical spinal TB was identified with a commercially antibody (IgG) detection kit (Yaji Inc., Shanghai, China).

Date management and statistical analyses

All data were entered into a Microsoft Office Excel file. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated to evaluate diagnostic performance for the ELISPOT and PPD skin test. Analyses were performed using the commercial statistical software SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).χ2 test or Fisher's exact test were used in contingency analyses. Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare nonparametric distribution of the SFC among different groups. The agreement beyond chance between the ELISPOT assay and the routine tuberculosis examination were assessed using the Kappa (κ) coefficient. Agreement was considered poor if κ < 0.2, fair if κ < 0.4, moderate if κ < 0.6, substantial if κ < 0.8 or good if κ > 0.8.16 All tests of significance were two-tailed, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics and clinical characteristics

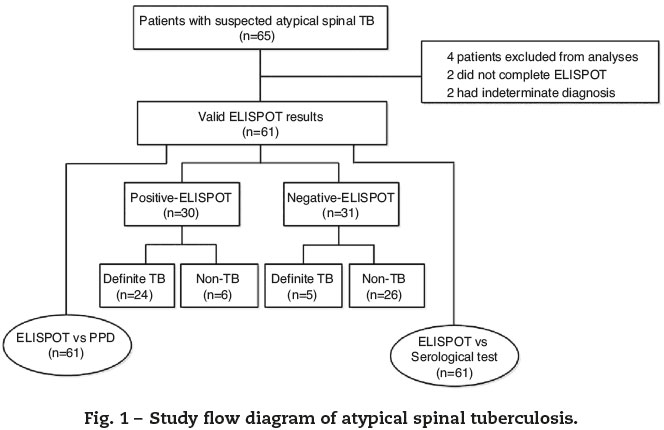

A total of 65 patients with suspected atypical spinal TB were recruited during the study period. Four patients were excluded from the study, among which two did not complete the ELISPOT assay and two had no final diagnosis. The remaining 61 patients were ultimately included for ELISPOT analyses (Fig. 1). The clinical characteristics of these 61 patients are summarized in Table 1. A diagnosis of TB (18 confirmed cases, 11 probable cases) was made in 29 patients (47.5%), and the remaining 32 patients (52.5%) did not have TB. The mean age (±standard deviation) of the patients with and without TB was 32.4 ± 14.9 and 47.9 ± 11.2 years, respectively. All patients enrolled in the present study were tested for HIV by serology and all had negative results. The median disease time course (± standard deviation) of atypical spinal TB patients was 9.7 ± 7.1 months.

Clinical presentation and imaging study findings

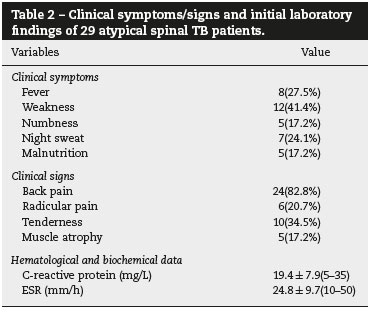

The clinical presentations of atypical spinal TB patients are summarized in Table 2. Back pain was the most common clinical complaint (24 patients, 82.8%), followed by tenderness (10 patients, 34.5%). Neurological deficit was found in one patient. All patients received an X-ray, computed tomography (CT) scan and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination. Radionuclide bone scanning was performed in five patients (17.2%), all of whom had foci of increased uptake. Through the imaging study, worm-eaten destruction of vertebral endplate was seen in five patients (Fig. 2). Destruction of centricity of the single vertebral body or concentric collapse of single vertebral body was seen in five patients (Fig. 3). Fifteen patients presented contiguous or skipped vertebral body destruction. Tuberculous abscess with no identifiable osseous lesion were visible by CT and MRI in four patients (Fig. 4).

Clinical diagnostic value of the ELISPOT assay for atypical spinal TB

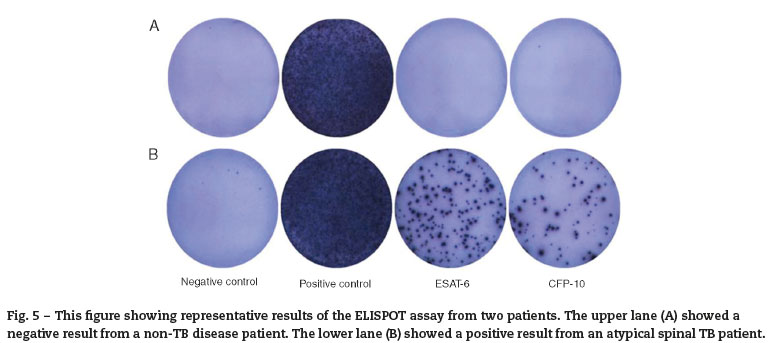

The ELISPOT was successfully performed on 61 enrolled subjects. The results are shown in Fig. 5. Out of 61 patients with suspected atypical spinal TB, 29 patients had positive ELISPOT results. The results of the various conventional diagnostic tests and the ELISPOT assay used to assess the samples from 61 patients with suspected atypical spinal TB are shown in Table 3. We found that 37.5% of the patients had a positive AFB smear and 78.3% had a positive culture for M. tuberculosis. All patients with culture-confirmed atypical spinal TB had positive ELISPOT results.

The overall sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values for atypical spinal TB diagnosis by the PPD skin test were 58.6%, 59.4%, 56.7% and 61.3%. By comparison, the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values for atypical spinal TB diagnosis by the ELISPOT assay were 82.8%, 81.3%, 80.0% and 83.9%, respectively. The overall sensitivity of the ELISPOT assay was higher than that of PPD skin test (p < 0.05).

The comparison of the ELISPOT assay with the conventional diagnostic tests is showed in Tables 4 and 5. Of the 23 patients with atypical spinal TB who had positive histopathological examination 21 showed positive ELISPOT results. When we assessed the agreement between the histopathology detection and the ELISPOT assay using the κ coefficient, we found moderate agreement between the two tests (κ = 0.506).

Factors associated with the ELISPOT results in atypical spinal TB

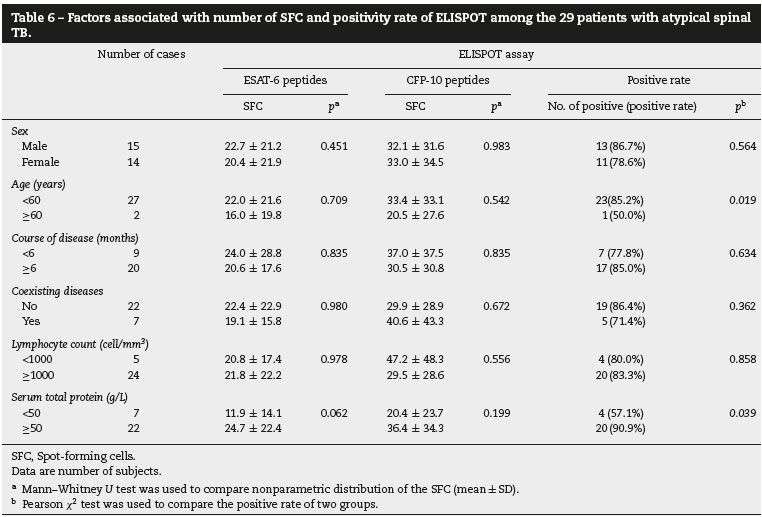

Table 6 shows clinical factors associated with number of SFC and positivity of the ELISPOT assay among the 29 patients with atypical spinal TB. The diagnostic sensitivity of the ELISPOT assay in atypical spinal TB patients with normal nutrition (serum total protein: >50 g/L) was higher (90.9%) than those with malnutrition (serum total protein: <50 g/L) (57.1%). Likewise, the diagnostic sensitivity of the ELISPOT assay in age-group <60 years was higher (85.2%) than among those aged > 60 years (50.0%). The number of SFC and positivity rate of the ELISPOT assay were not influenced by sex, course of disease, coexisting diseases and lymphocyte count.

Discussion

Tuberculosis (TB), more prevalent in immunocompromised persons, is an emerging international problem despite advances in the methods of diagnosis and treatment; it is still prevalent in developing countries and is on the rise in the developed ones.18,19In addition to the most common manifestation-pulmonary TB, atypical spinal TB also comprised a small proportion of extrapulmonary TB. Clinically, atypical spinal TB usually presents in a slowly indolent manner with nonspecific clinical presentations making the diagnosis a great challenge for physicians. Definite diagnosis is generally considered to require microbiological confirmation; however, the bacteriological gold-standard result, including solid media-based culture techniques using Lowenstein-Jensen slants and Middlebrook 7H10/7H11 agar and liquid media-based methods, such as with the BACTEC 960 MGIT system, usually takes several weeks to become available. These may lead to delay in diagnosis and initiation of treatment. In some atypical forms of the disease, this may have disastrous consequences. Therefore, rapid, sensitive and specific diagnostic tests for atypical spinal TB are required.

The ELISPOT assay is a rapid test, which only takes two days and has been used in the diagnosis of extrapulmonary TB,13,14 including skeletal TB, TB pleurisy, intestinal TB, cutaneous TB.11,12,20-22 We performed this study to evaluate the usefulness of the ELISPOT assay in diagnosing atypical spinal TB. In this study, we found that the sensitivity of the ELISPOT for diagnosing atypical spinal TB was 82.8%, which was higher than that of PPD skin test, AFB smear and M. tuberculosis culture from biopsy samples. In Taiwan, Lai et al.11 found that the ELISPOT had a sensitivity of 86.7% for diagnosing skeletal TB (sensitivity of 100% for diagnosing spinal TB). In Korea, Cho et al.12 found that the sensitivity of the ELISPOT for active osteoarticular TB (including 15 spinal TB patients) was 100%. Despite the limited sample size of the present work, this is the first study to specifically evaluate the diagnostic performance of the ELISPOT assay for atypical spinal TB. These findings indicate that the ELISPOT assay is a useful adjunct to current tests for diagnosis of atypical spinal TB.

Spinal TB in early stage has no specific features on radiological image, so plain radiography is of little help unless the collapse of disk margin or vertebra body appears. CT scan is valuable in revealing bony destruction and paraspinal abscesses formation. MRI is more sensitive in diagnosing spinal TB. It can detect abnormal bone marrow with a low signal on T1-weighted images as well as a high signal on T2-weighted images which cannot be detected by radiographs and CT scans.23,24 However, in case of inflammation of the vertebral body without any obvious deformity or cold abscess, the diagnostic value of MRI was very limited. In this study, three patients presented concentric collapse of single body without destruction of adjacent vertebral bodies and intervertebral disk. Among these three patients, there was no history of exposure to TB, no pulmonary tuberculosis, recent weight loss, low-grade fever, decreased appetite and night sweats. Laboratory examinations such as ESR and CRP were within the normal range. Mantoux test was nonconclusive. The results of MRI combined PET-CT prompted spinal tumor. Nevertheless, the results of the ELISPOT assay were positive in these three patients. At last, the three patients underwent invasive procedures to obtain a tissue specimen for diagnosic purposes. Histological analysis of fast frozen section demonstrated a chronic granulomatous inflammation with caseation, a character of tuberculosis. In this series, 26 patients with mycobacterial infection underwent invasive procedures to obtain a tissue specimen for diagnostic purposes, and 23 (88.5%) of these patients had histopathologic features consistent with a diagnosis of TB infection. Among these 23 patients, positive ELISPOT results were found in 21 patients. Although the sample size is too small to make a solid conclusion, this finding suggests that the use of the ELISPOT assay, a relatively less invasive but sensitive tool, appears to be used as a complementary method in the diagnosis of atypical spinal TB in clinical settings.

In this study, we found that age and malnutrition were associated with ELISPOT positivity in atypical spinal TB patients. Among these 29 patients with atypical spinal TB, there were three children aged less than 5 years. Only one child had a positive ELISPOT result. Previous studies also demonstrated that the ELISPOT assay had a sensitivity of 80-90% for the diagnosis of pediatric tuberculosis. A substantial proportion of young children with clinical and/or microbiologic evidence of active TB had negative ELISPOT assay results.25,2>6 The clinical utility of the ELISPOT for elderly patients with atypical spinal TB was not clear, because only two patients aged more than 60 years were enrolled in our study. Likewise, The diagnostic sensitivity of the ELISPOT assay in atypical spinal TB patients with normal nutrition (serum total protein: >50 g/L) was higher than that of atypical spinal TB patients with malnutrition (serum total protein: <50 g/L). Four of seven atypical spinal TB patients with malnutrition had false-negative ELISPOT results. A potential mechanism could underlie this finding. Severe wasting disease or malnutrition causes unhealthy emaciation with extremely low serum total protein, debilitating the patients and also suppressing systemic immune response.27 Hang et al., also found that emaciation was a risk factor for false-negative result of ELISPOT assay.28 These risk factors might result in a somewhat disappointing sensitivity for the ELISPOT assay in our study.

In the present work, six (18.6%) of 32 patients with positive ELISPOT results did not have active TB. This result can be explained by the following reason. The ELISPOT assay can detect latent TB infection (LTBI) as well as active TB, but it cannot differentiate LTBI from active TB. Therefore, a positive ELISPOT assay result might be due to LTBI. The inability of this test to discriminate active TB from LTBI might limit its application in the detection of active TB, especially in countries with a high prevalence of TB, such as China. Patients with LTBI are expected to have a positive ELISPOT assay.

This study had several limitations. First, we did not assess the immune function of atypical spinal TB patients so that we could discuss the relationship between sensitivity of this assay and the features of T lymphocyte subsets in atypical spinal TB patients, because only a limited number of immunocompromised patients were enrolled in this study. Thus, further studies are needed to assess the diagnostic performance of ELISPOT assay in immunocompromised patients. Second, the small sample size of atypical spinal TB patients limited the reliability of sensitivity estimates for the ELISPOT assay, and further large-scale studies are needed to clarify its diagnostic value in this disease category.

In conclusion, the ELISPOT assay appears to be a useful supplementary tool for diagnosing atypical spinal TB.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Received 20 November 2012

Accepted 8 January 2013

Available online 1 July 2013

- 1. Ferrer MF, Torres LG, Ramírez OA, Zarzuelo MR, González NDP. Tuberculosis of the spine. A systematic review of case series. Int Orthop. 2012;36:221-31.

- 2. Polley P, Dunn R. Noncontiguous spinal tuberculosis: incidence and management. Eur Spine J. 2009;118:1096-101.

- 3. Milburn H. Key issues in the diagnosis and management of tuberculosis. J R Soc Med. 2007;1100:134-41.

- 4. Pande KC, Babhnlkar SS. Atypical spinal tuberculosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;398:67-74.

- 5. Yu Y, Wang X, Du B, Yuan W, Ni B, Chen D. Isolated atypical spinal tuberculosis mistaken for neoplasia: case report and literature review. Eur Spine J. 2012, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00586-012-2294-z

- 6. Nagashima H, Yamane K, Nishi T, Nanjo Y, Teshima R. Recent trends in spinal infections: retrospective analysis of patients treated during the past 50 years. Int Orthop. 2010;34:395-9.

- 7. Jain AK. Tuberculosis of the spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;460:2-3.

- 8. Porsa E, Cheng L, Graviss EA. Comparison of an ESAT-6/CFP-10 peptide-based enzyme-linked immunospot assay to a tuberculin skin test for screening of a population at moderate risk of contracting tuberculosis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2007;14:714-9.

- 9. Behr MA. Comparative genomics of BCG vaccines. Tuberculosis. 2001;81:165-8.

- 10. Harboe M, Oettinger T, Wiker HG, Rosenkrands I, Andersen P. Evidence for occurrence of the ESAT6 protein in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and virulent Mycobacterium bovis and for its absence in Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Infect Immun. 1996;64:16-22.

- 11. Lai CC, Tan CK, Liu WL, et al. Diagnostic performance of an enzyme-linked immunospot assay for interferon-I in skeletal tuberculosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30:767-71.

- 12. Cho OH, Park SJ, Park KH, et al. Diagnostic usefulness of a T-cell-based assay for osteoarticular tuberculosis. J Infect. 2010;61:228-34.

- 13. Kim SH, Choi SJ, Kim HB, Kim NJ, Oh MD, Choe KW. Diagnostic usefulness of a T-cell based assay for extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2255-9.

- 14. Liao CH, Chou CH, Lai CC, et al. Diagnostic performance of an enzyme-linked immunospot assay for interferon-gamma in extrapulmonary tuberculosis varies between different sites of disease. J Infect. 2009;59:402-8.

- 15. Kim SH, Song KH, Choi SJ, et al. Diagnostic usefulness of a T-cell-based assay for extrapulmonary tuberculosis in immunocompromised patients. Am J Med. 2005;122:189-95.

- 16. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159-74.

- 17. Jung JY, Lim JE, Lee H, et al. Questionable role of interferon-γ assays for smear-negative pulmonary TB in immunocompromised patients. J Infect. 2012;64:188-96.

- 18. Turgut M. Spinal tuberculosis (Pott's disease): its clinical presentation, surgical management, and outcome. A survey study on 694 patients. Neurosurg Rev. 2001;24:8-13.

- 19.Pertuiset E, Beaudreuil J, Liote F, et al. Spinal tuberculosis in adults. A study of 103 cases in a developed country, 1980-1994. Med (Baltimore). 1999;78:309-20.

- 20. Lee LN, Chou CH, Wang JY, et al. Enzyme-linked immunospot assay for interferon-gamma in the diagnosis of tuberculous pleurisy. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:173-9.

- 21. Lai CC, Lee TC, Hsiao CH, et al. Differential diagnosis of Crohn's disease and intestinal tuberculous by enzyme-linked immunospot assay for interferon-γ. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2121-2.

- 22. Lai CC, Tan CK, Lin SH, et al. Diagnostic value of an enzyme-linked immunospot assay for interferon-γ in cutaneous tuberculosis. Diag Microbiol Infect Disease. 2001;70:60-4.

- 23. Tsai C-Y, Tsai T-H, Lin C-H, et al. Unusual exophytic neurocytoma of thoracic spine mimicking meningioma: a case report and review of the literature. Eur Spine J. 2011;20:239-42.

- 24. Polley P, Dunn R. Noncontiguous spinal tuberculosis: incidence and management. Eur Spine J. 2009;18:1096-101.

- 25.Nicol MP, Davies MA, Wood K, et al. Comparison of T-SPOT.TB assay and tuberculin skin test for the evaluation of young children at high risk for tuberculosis in a community setting. Pediatrics. 2009;123:38-43.

- 26. Liebeschuetz S, Bamber S, Ewer K, Deeks J, Pathan AA, Lalvani A. Diagnosis of tuberculosis in South African children with a T-cell-based assay: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2004;364:2196-203.

- 27. Schluger NW, Rom WN. The host immune response to tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:679-91.

- 28. Hang NTL, Lien TL, Kobayashi N, et al. Analysis of factors lowering sensitivity of interferon-γ release assay for tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23806.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

21 Oct 2013 -

Date of issue

Oct 2013

History

-

Received

20 Nov 2012 -

Accepted

08 Jan 2013