Abstracts

This study aims to describe the elements – context and resources –influencing social participation in a Municipal Health Council (MHC). It is a descriptive research using a qualitative approach. Data collection was done through direct observation of the MHC dynamics and semi-structured interviews with its members. Data analysis was based on thematic analysis, aiming to fit into the categories established by World Health Organization (WHO) regarding the dimensions of context and resources that influence participatory culture, such as: i) awareness related to political participation; ii) civil society organization; iii) structures and spaces; iv) resources; v) knowledge; and vi) impact of policies and past practices. As a result, authors found problems with regards to these components, as well as the fact that social participation is still weak and its biggest obstacles are related to communication between stakeholders and social institutions.

Social participation; Municipal health council; Participatory culture

Este estudo pretende descrever os elementos – contexto e recursos – que influenciam a participação social em um Conselho Municipal de Saúde (CMS). Trata-se de pesquisa descritiva com abordagem qualitativa. Os dados foram coletados por meio de observação direta da dinâmica do CMS estudado e de entrevistas semiestruturadas com seus membros. A análise dos dados baseou-se na análise temática, visando aproximar as categorias obtidas com as categorias estabelecidas pela OMS sobre as dimensões do contexto e dos recursos que influenciam a cultura participativa, quais sejam: i) políticos conscientes da questão da participação; ii) organização da sociedade civil; iii) estruturas e espaços; iv) recursos; v) conhecimento; e vi) impacto das políticas e práticas anteriores. Como resultado, constatou-se que os componentes são deficientes e a participação popular é ainda precária, e os maiores obstáculos são aqueles relacionados à comunicação entre vários atores e instituições sociais.

Participação social; Conselho municipal de saúde; Cultura participativa

El objetivo de este estudio es describir los elementos – contexto y recursos – que influyen en la participación social en un Consejo Municipal de Salud (CMS). Se trata de un estudio descriptivo con abordaje cualitativo. Los datos se colectaron por medio de la observación directa de la dinámica del CMS estudiado y de entrevistas semi-estructuradas con sus miembros. El análisis de los datos se basó en el análisis temático, con el objetivo de aproximar las categorías obtenidas con las establecidas por la Organizaciõn Mundial de Salud (OMS) sobre las dimensiones del contexto y de los recursos que influyen en la cultura participativa y que son los siguientes: i) políticos conscientes de la cuestión de la participación; ii) organización de la sociedad civil; iii) estructura y espacios; iv) recursos; v) conocimiento; y vi) impacto de las políticas y prácticas anteriores. Como resultado, se constató que los componentes son deficientes, que la participación popular todavía es precaria y que los mayores obstáculos son los relacionados a la comunicación entre diversos actores e instituciones sociales.

Participación social; Consejo municipal de salud; Cultura participativa

Introduction

The proposal of society's participation in political projects of any kind arose from the 1940s with two purposes: to reinforce the mechanisms of democracy, worldwide undermined by the two great wars, and as a way of minimizing the growing responsibilities of the modern-neoliberal State toward the citizens 11. Testa M. Pensar em saúde. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas, Abrasco; 1992. . With the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the right to health became a fundamental human right, consolidated with the 1966 United Nations International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Subsequently, the 1978 Alma-Ata Declaration on Primary Care, in addition to other Resolutions and Declarations approved in the context of the World Health Organization (WHO), base the understanding of social participation as a means of defending the right to health.

For that matter, although the outbreak of the social participation practice was initially motivated by the socially constructed need to supervise and control the State, through this participation, achieving progress in the construction of a network of health services is possible, in which all persons involved fight for their rights and are committed to the collective. Within the Municipal Health Councils (MHC), social participation can contribute to the organization of a more resolute and equitable local health network, emerging as a democratic space for the social participation manifestation.

In this perspective, the World Health Organization 22. Organização Mundial de Saúde (OMS). Diminuindo as diferenças: a prática das políticas sobre determinantes sociais de saúde: documento de discussão. Rio de Janeiro; 2011. built a participatory culture model, emphasizing the context and resources dimensions that influence social participation. This study aims to describe the elements – context and resources – that influence social participation in a MHC in a countryside of the state of São Paulo. Thus, at first, we present the relationship between social participation and the Unified Health System, listing the necessary components for participation; later, the history, structure and competencies of the MHC are addressed; and finally, the we discuss about the construction and the gaps of the participatory culture of the studied MHC.

The Unified Health System (UHS) and social participation

Since the 1988 Brazilian Constitution, the Unified Health System assures social participation, stimulating the understanding, controlling and supervising the society on the State actions. It is a way of achieving democracy, which represents a system of government in which political decisions follow the needs and orientations of citizens, through their representatives (council members, representatives and senators) or directly by the people. With social participation, citizens can interfere in the planning, implementation and evaluation of government activities in relation to guaranteeing the human right to health 33. Tribunal de Contas da União (BR). 4a Secretaria de Controle Externo. Orientações para conselheiros de saúde. Brasília; 2010. .

However, even with this democratic opening for the civil society political manifestation, deficiencies in social participation are evident. In the early 2000s, Baquero 44. Baquero M. Cultura política participativa e desconsolidação democrática – reflexões sobre o Brasil contemporâneo. São Paulo Perspec. 2001; 15(4):98-104. pointed out that still prevailed in national politics that the principle of social exclusion that "far from building a participatory and democratic political culture, it materializes as a fragmented and individualistic political culture with little social capital" (p.103).

Considering the Latin acceptation of culture, which derives from the Latin verb colere , meaning cultivation or care, "an action that leads to the full realization of the potentialities of something or someone" 55. Chauí M. Cultura e democracia. Crít Emancip. 2008; 1(1):53-76. (p.55), the construction of a participatory culture that respects "the autonomy of people and their rights" 22. Organização Mundial de Saúde (OMS). Diminuindo as diferenças: a prática das políticas sobre determinantes sociais de saúde: documento de discussão. Rio de Janeiro; 2011. (p.18), demands time, requiring a propitious ground so that the potentialities can flourish and manifest. Considering that in the Brazilian case, social exclusion in politics is still present, paradoxically, we must rely on the collaboration of governments and political representatives to build the necessary conditions for the emergence of social participation.

As a way to reduce social inequalities in health, governments can create mechanisms to facilitate social participation, ensuring a more equitable representation and ensuring "legitimacy and giving voice to all parties involved" 22. Organização Mundial de Saúde (OMS). Diminuindo as diferenças: a prática das políticas sobre determinantes sociais de saúde: documento de discussão. Rio de Janeiro; 2011. (p.13). This would occur through the institutionalization of formal, transparent and public mechanisms, offering incentives, subsidies, access to information and training to the interested parties, increasing community autonomy, reaching poor groups and dealing with existing conflicts of interest.

In turn, civil society must also take responsibility for building a new participatory culture. "Involving communities by monitoring responsibility for decision-making is particularly important" 22. Organização Mundial de Saúde (OMS). Diminuindo as diferenças: a prática das políticas sobre determinantes sociais de saúde: documento de discussão. Rio de Janeiro; 2011. (p.18). In addition to monitoring the implementation of policies and their outcomes, civil society can contribute by raising public awareness on health inequities, helping communities to organize and advocate for more inclusive governance 22. Organização Mundial de Saúde (OMS). Diminuindo as diferenças: a prática das políticas sobre determinantes sociais de saúde: documento de discussão. Rio de Janeiro; 2011. . Carvalho 66. Carvalho SR. Os múltiplos sentidos da categoria “empowerment” no projeto de Promoção à Saúde. Cad Saude Publica. 2004; 20(4):1088-95. would classify this as "community empowerment": whose "central aspect is the possibility in which individuals and collectives develop competences to participate in life in society, which includes skills, but also a reflexive thinking that qualifies political action" (p.1092).

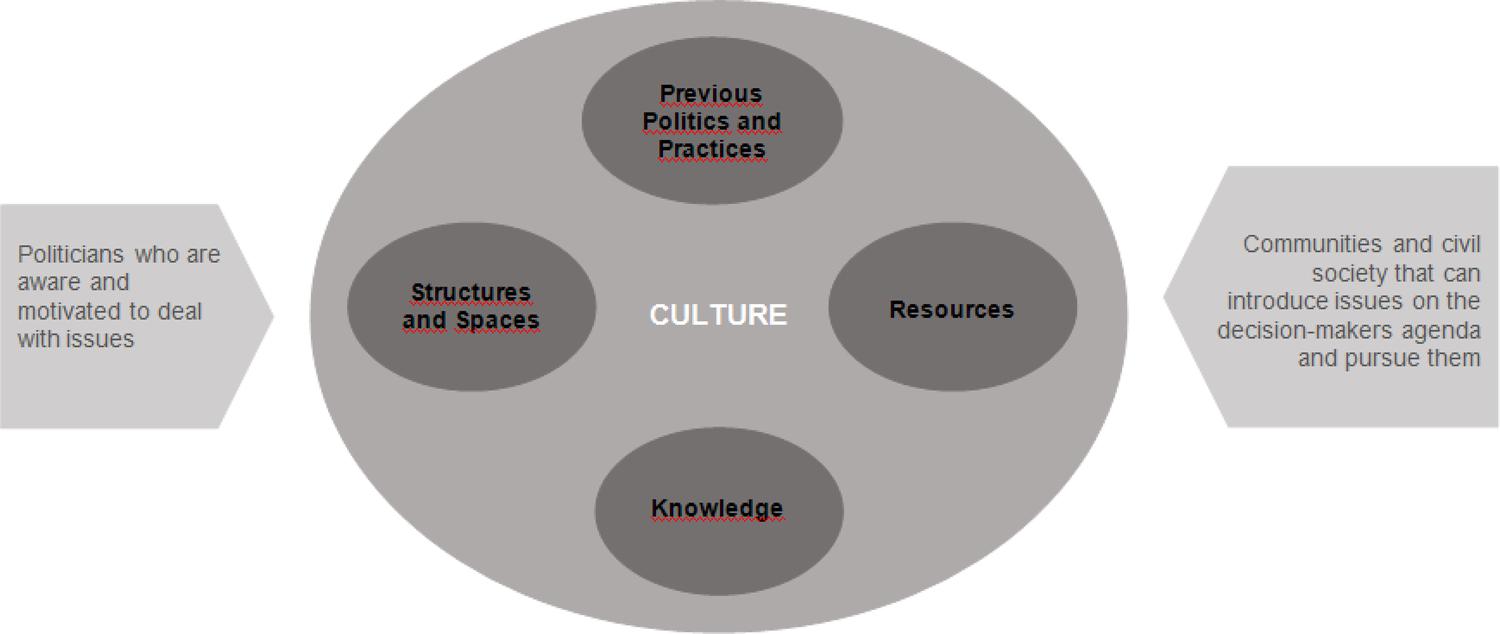

According to the World Health Organization 22. Organização Mundial de Saúde (OMS). Diminuindo as diferenças: a prática das políticas sobre determinantes sociais de saúde: documento de discussão. Rio de Janeiro; 2011. , in addition to governments and politicians sensitive to the participation issue and to a civil society organized and mobilized in defense of their interests and rights, constructing a participatory culture depends on four fundamental components:

a) structures and spaces that allow participation, including political, physical and institutional structures, such as, in the case of participation in health, appropriate institutions for the manifestation and presentation of community demands. In addition, these places should have adequate infrastructure to receive social segments, such as adequate physical space, service hours and meetings accessible to the population;

b) resources: the parties need the time, money and institutional capacity to promote their participation and defend their interests. The availability of resources depends not only on government, since the civil society can offer incentives for participation and "help communities to identify the issues they should prioritize" 22. Organização Mundial de Saúde (OMS). Diminuindo as diferenças: a prática das políticas sobre determinantes sociais de saúde: documento de discussão. Rio de Janeiro; 2011. (p.19);

c) knowledge: information should be available to the public and participants should have sufficient knowledge to participate in and understand bureaucratic processes. The provision of training courses, both for representatives of different social segments (managers, professionals and representatives of users) and for the community itself, contributes to building knowledge and strengthening participatory culture;

d) the impact of previous policies and practices on participation and its relationship with government: the experiences that social groups have about their relationship with governments and participating institutions can influence political perceptions and formulations. "Groups that suffer discrimination will be very refractory to integrate participating mechanisms" 22. Organização Mundial de Saúde (OMS). Diminuindo as diferenças: a prática das políticas sobre determinantes sociais de saúde: documento de discussão. Rio de Janeiro; 2011. (p.19). The crisis in representativeness, that is, the social segments feel not represented, also discourages the participatory culture. Figure 1 illustrates the dimensions of the context of participatory culture and resources that influence social participation.

In this scenario, several spheres of popular participation within the UHS hierarchy can assist the society in the social participation exercise in the health area: the Health Conferences and the Health Councils (federal, state and municipal). This study focuses on the Municipal Health Council as a social participation body.

The Brazilian Municipal Health Councils

In 1990, Law no. 8,142/90 established the creation of permanent and deliberative federal, state and municipal health councils, such as collegiate bodies composed of government representatives, service providers, healthcare professionals and users 77. Lei n° 8.142/90, de 28 de dezembro de 1990. Dispõe sobre a participação da comunidade na gestão do Sistema Único de Saúde e sobre as transferências intergovernamentais de recursos financeiros na área saúde. Diário Oficial da União. 19 Set 1990. with the capacity to evaluate and supervise health services and resources, and the Councils are responsible for disseminating the work and decisions to all media, including information on agendas, dates and places of meetings.

Therefore, the MHCs have a strategic importance in the process of restructuring health care and in reformulating relationships between managers, professionals and users. For that matter, the MHCs should function as instances of social participation, as spaces of expression of demands and expectations of the various segments that compose them 88. Cortes SMV. Construindo a possibilidade de participação de usuários: conselhos e conferências no Sistema Único de Saúde. Sociologias. 2002; 4(7):18-49. , 99. Van Stralen CJ. Conselhos de saúde: efetividade do controle social em municípios de Goiás e Mato Grosso do Sul. Cienc Saude Colet. 2006; 11(3):621-32. .

However, at times the councils are ineffective at inserting the grassroots in political discussion and claim to rights for the precariousness of communication, and the transmission of information among councilors and their own base of support 1010. Oliveira VC. Comunicação, informação e participação popular nos conselhos de saúde. Saude Soc. 2004; 13(2):56-69. discouraging engagement and the participation. In this context, the representativeness issue is problematic, since "not always the representatives of the users and the patients' associations can be representative of the needs of the entire population and, above all, of the most disadvantaged social sectors" 1111. Serapioni M. Os desafios da participação e da cidadania nos sistemas de saúde. Cienc Saude Colet. 2014; 19(12):4824-37. (p.4834).

Objectives and methods

This study aims to describe the dimensions of the context of participatory culture and resources that influence social participation in a MHC in a countryside of the State of São Paulo.

This is a descriptive research with a qualitative approach. Data were collect through direct observation of the MHC dynamics and semi-structured interviews with its members. For the direct observation, during the data collection period, one of the authors of this study attended MHC meetings as a listener to obtain more information about the MHC dynamics and the performance of the councilors. This observation was based on a pre-established script about the dynamics of meetings, quorum, the most evident segments and population presence, providing us with data about the resources, structures and spaces elements. As for the semi-structured interviews, they provided information on knowledge, policies and practices and culture, as well as on relations with the external environment, especially with politicians and civil society organizations.

The data analysis collected through observation and interviews based on Bardin's thematic analysis 1212. Bardin L. Análise de conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70; 1995. , through an exhaustive reading of the material for data organization and subsequent identification and systematization of thematic units. This analysis sought to approximate the categories identified with the dimensions of the context and the resources that influence the participatory culture, shown in figure of the WHO 22. Organização Mundial de Saúde (OMS). Diminuindo as diferenças: a prática das políticas sobre determinantes sociais de saúde: documento de discussão. Rio de Janeiro; 2011. , namely: i) politicians aware of the participation issue; ii) organization of civil society; iii) structures and spaces; (iv) resources; v) knowledge; and vi) impact of previous policies and practices. Firstly, two authors carried out a thorough reading of the material separately, reviewing observation and interviews data, exploring, organizing and identifying thematic units and their subcategories. Afterwards, the other two authors reviewed the analyzes and categorizations, establishing the main themes. The results of this second stage were submitted to the appreciation of all authors until they reached a consensus on the final thematic units.

The Research Ethics Committee of the University of São Paulo at School of Nursing of Ribeirão Preto approved the project, protocol no. 1450/2011.

Results and Discussion: Participatory culture – context and resources

At the time of the research, 26 titular members were identified in the studied MHC, of which 13 (50%) were representatives of UHS users and the other 50% were representatives of healthcare professionals, service providers, scientific community and government. Nine were interviewed – two managers, two service providers and five representatives of users – with a 5-year average time working in the MHC. Among those interviewed, six were men and three were women, who had the following professions: business administrator, physician, pharmacist, administrative manager, social worker, general services, security, microentrepreneur and retired. One participant was single. Each interview lasted an average of one hour.

Thematic units according to the dimensions of resource and context that influence participatory culture based on the model proposed by WHO are presented next.

i) Government and politicians aware of the participation issue

Difficulties in the integration between the MHC and other organs of the Government

The functioning and performance of MHC depend on its relationship with other spheres of society, especially the government. In this regard, the councilors mentioned the need to receive more attention from the government towards their requests.

“Our rulers even consider us as Council when they have some self-interest, but when we claim, question that certain action is wrong; they ask why we are there. (...). Our rulers needed to listen to the Councils more, to listen more to organized society, because we have free ideas and they forget about the community discussion space”. (C1)

The lack of commitment of Brazilian political elites to democracy leads to the population disbelief in the concrete possibility of democratic effectiveness, leading to a reduction in the population's participation in social control and in the preservation and continuity of an authoritarian regime 1313. Fleury S. Democracia, descentralização e desenvolvimento: Brasil e Espanha. Rio de Janeiro: FGV; 2006. . The organization of social groups and the knowledge of the bureaucratic processes of the public sphere facilitate dialogue with the State 1414. Valla VV, Stotz EN, organizadores. Educação, saúde e cidadania. Petrópolis: Vozes; 1994. , 1515. Coelho JS. Construindo a participação social no SUS: um constante repensar em busca de equidade e transformação. Saude Soc. 2012; 21 Supl1:138-51. . However, organized groups with little representativeness, ties of belonging and fragile projects, acting only for interests, especially economic interests, are incapable of expanding democratic relations between population and government nor do they collaborate for justice and popular emancipation 1616. Cohn MG. Empoderamento e participação da comunidade em políticas sociais. Saude Soc. 2004; 13(2):20-31. .

Ii) Organization of civil society

Lack of deliberative quorum

As already mentioned, an organized civil society has a better dialogue with the government; however, in the case of the studied MHC, there was a disarticulation of the representatives of the social segments. The lack of a deliberative quorum disturbs the councilors who attend and commit to the meetings of the Council, since they declare that they spend time and energy to dedicate themselves to a cause that they consider important and that are hampered by other members who do not assume responsibility towards the councilor position, causing discomfort among the participants and lack of motivation for future participation.

“It's important to attend the meetings, I have my appointments, but I come here, but there are people who do not consider it like this and do not come... sometimes we cannot vote because there are not enough people... we lose a lot of time”. (C9)

Still based on the observation, we inferred that the presence of managers has increased due to the role assigned to them to conduct meetings, to bring as much information as possible about the raised issues and to clarify doubts that may arise. The segment of users also had a high presence.

The (Dis)integration between the MHC and civil society

According to those interviewed, what harms popular participation in the MHC is the fact that the population expresses itself individually and not organized in community. They reported realizing a timely participation of some members of the Council, since the representatives do not join the community to bring their demands, that is, there is no effective channel of communication with the population.

“I observe a very individual participation”. (C6)

“It ends up being restricted, for example, to a representative of Residents' Association who is part of the Council, or a relative; an acquaintance is more or less restricted to each councilor”. (C7).

This indicates a representativeness problem, as mentioned previously 1111. Serapioni M. Os desafios da participação e da cidadania nos sistemas de saúde. Cienc Saude Colet. 2014; 19(12):4824-37. , damaging the population's interest in the issues concerning the MHC actions and deliberations.

One of the media used by the population to meet their needs is the television.

“Not even when they have some difficulty they don't come [...]. Nowadays they are used to go to the media, to the press (...)”. (C3)

(iii) Structures and spaces

Physical and institutional difficulties for participation

The studied MHC consists of 26 holders, of which 50% (thirteen) are representatives of the UHS users and the other 50% are representatives of healthcare professionals, service providers, scientific community, health-related business entities and government representatives.

According to councilors, people find physical difficulties, such as overloading activities, and institutional, such as meeting place and time, to cultivate a culture of participation.

“Due to lack of information and openness, she has not participated very much, it would be ideal if she participated much more. (...) we know that there is an effort to make access difficult, because the users are people who work, in a meeting at 2:00 p.m. he can't participate because he is working (...) Council meetings are at 7 p.m. only one meeting per month”. (C4).

“90% knows but does not participate; they do not come (...). Nowadays, people live to get up to work, come back at 6 o'clock in the afternoon, have dinner, wash clothes, take care of children, there is no time to come to the councils, to participate even in communities, neighborhood associations”. (C3)

In order to obtain greater popular participation, it was suggested that the MHC would meet "once a month with the population of each region of the municipality" (C4), in order to get closer to the community and better understand their demands. More media coverage of the MHC was also recommended, regarding achievements so that the population would understand how the MHC works and what improvements are made in the city from their actions.

iv) Resources

Inadequate infrastructure and lack of financial resources

Regarding the resources for participation, a study by Coelho 1515. Coelho JS. Construindo a participação social no SUS: um constante repensar em busca de equidade e transformação. Saude Soc. 2012; 21 Supl1:138-51. reported the population's disadvantage, since they have no time, transportation, institutional advice, in short, an entire infrastructure that should be present so that they could participate more in bodies such as the MHC.

In the studied MHC case is not different, besides facing some difficulties in the exercise of their tasks, such as lack of adequate infrastructure for small meetings, study, research and discussion; difficulty in attending training courses for new councilors; lack of financial resources to cover travel and participation of councilors in congresses or other meetings dealing with public health; the councilors, especially in the user segment, still find it difficult to present their demands, a fact that may undermine the construction of the participatory culture.

“I think members could at least receive the bus ticket to attend meetings”. (C8)

“Look, it was very hard to us to get this room and this computer, it's still not enough, but it's better than nothing, right?” (C5)

v) Knowledge

Gaps in the training of councilors

The knowledge issue is important for the quality of participation and social representativeness. From this perspective, in the studied MHC, there is a need for some members to get better trained.

During the observation, there were some difficulties related to the dynamics of the council, such as: lack of knowledge regarding the UHS functioning, legislation, subjects and technical terms of the healthcare area; repetition of the statements of other councilors or of the same subject several times during the same meeting; and the lack of previous study of the subjects discussed in the meetings, despite the guidelines delivery.

Moreover, in many situations, Council discussions restricted to bureaucratic issues such as accountability and health plans that could be addressed in the healthcare facilities, allowing the MHC to address broader issues for the municipality. Therefore, we observed that the Council still has little autonomy to define healthcare policies, often functioning as a bureaucratic instance and with minimal inter-sectoral articulation.

The respondents mentioned the need to improve representativeness, with the councilor adequately fulfilling his/her role, not only with regard to the councilor-segment articulation they represent, such as the councilor's own performance during the meetings. As suggestions to deal with the mentioned problems, the talked about the creation of a permanent training course for councilors, as well as a more judicious process of selection.

“ (...) permanent training course for councilors on UHS issues, how it works, what accumulated budget is, because we use many technical terms difficult to understand”. (C6)

The low number of councilors who receive training before taking the function exposes a fragility of the Council, which may be a consequence of the low supply of training in the area of social participation and/or a kind of "side effect" of the legal minimum rotation mechanism of councilors. From this perspective, capacity-building is considered essential to achieve adequate and effective participation 1717. Cotta RMM, Martins PC, Batista RS, Franceschinni SCC, Priore SE, Mendes FF. O controle social em cena: refletindo sobre a participação popular no contexto dos conselhos de saúde. Physis. 2011; 21(3):1121-37. , 1818. Duarte EB, Machado MFAS. O exercício do controle social no âmbito do conselho municipal de saúde de Canindé, CE. Saude Soc. 2012; 21 Supl1:126-37. , 1919. Cruz PJSC. Desafios para a participação popular em saúde: reflexões a partir da educação popular na construção do conselho local de saúde em comunidades de João Pessoa, PB. Saude Soc. 2012; 21(4):1087-100. , 2020. Silva EC, Pelicioni MCF. Participação social e promoção da saúde: estudo de caso na região de Paranapiacaba e Parque Andreense. Cienc Saude Colet. 2013; 18(2):563-72. .

In addition, the projects and training courses for health councils usually do not take into account daily needs, and the pedagogical methodologies and referrals often do not contemplate the diversity and heterogeneity of the groups. In this sense, it is challenging to develop experiences that can meet these premises, socializing "technical" knowledge, so that they are "appropriated" by heterogeneous groups such as councilors 2121. Alencar HHR. Educação permanente no âmbito do controle social no SUS: a experiência de Porto Alegre-RS. Saude Soc. 2012; 21 Supl1:223-33. .

Insufficiency of information on social participation and unfamiliarity of the population

Unfamiliarity and insufficiency of information comprehensible to the population about social participation do not only affect the participation of the councilors, but also the mobilization of the people. The majority of the councilors cited the population's lack of knowledge regarding their rights in the health area, as well as social participation, attributing this fact to the lack of sources of information and dissemination.

“Health, as a citizen's universal right, is not disclosed as it should, and often the press (...) does not give the information, and does not spread all rights”. (C3)

In this process, the importance of valuing education movements in rights, as an essential step for the empowerment of health service users is highlighted in this process, because, despite the existing legal mechanisms and public policies, it is also difficult for the population to understand the meaning of their rights; they experience it more as a favor granted by the State than as a priority right to the exercise of their human dignity 2222. Ventura CAA, Mello DF, Andrade RD, Mendes IAC. Aliança da enfermagem com o usuário na defesa do SUS. Rev Bras Enferm. 2012; 65(6):893-8. .

The councilors widely criticized media as a communication channel and information diffuser, because they reported they did not receive media support in order to publicize the MHC achievements and inform the population about this democratization space.

“The media and the Secretariat [of Health] are not interested in disseminate information (...) I'm sure that if the population had more access to information, it would be participating more”. (C4)

Disseminating and circulating information among representatives of collegiate bodies and their representatives is a basic assumption for the effectiveness of social participation in the health system. However, the health services organization, which still reflects the model centered on the medical act aimed at healing actions, is not concerned with awakening the subject for social participation in health 2323. Faria EM. Comunicação na saúde: fim da simetria? Pelotas: Ed. Universitária; 1996. , 2424. Soratto J, Witt RR, Faria EM. Participação popular e controle social em saúde: desafios da Estratégia Saúde da Família. Physis. 2010; 20(4):1227-43. . In this movement, the MHC, through its representatives, could play a more active role with the represented segments in view of training and education in the rights of the population.

vi) Impact of previous policies and practices

MHC achievements

The effectiveness of participation topic is recurrent in the international literature of the last 10 years, since participation necessarily implies the ability to influence together with a public decision-making process. For Entwistle 2525. Entwistle VA. Public involvement in health service governance and development: questions of potential for influence [editorial]. Health Expect. 2009; 12(1):1-3. , "the notion of participation makes little sense if the potential for influence is lacking" (p.1). From this perspective, several national surveys have emphasized that the representatives' voice of user segments is not always able to influence the MHC deliberations 2626. Labra MH. Política nacional de participação na saúde: entre a utopia democrática do controle social e a práxis predatória do clientelismo empresarial. In: Fleury S, Lobato LVC, organizadores. Participação, democracia e saúde. Rio de Janeiro: Cebes; 2009. , 2727. Bispo Júnior JP, Gerschman S. Potencial participativo e função deliberativa: um debate sobre a ampliação da democracia por meio dos conselhos de saúde. Cienc Saude Colet. 2013; 18(1):7-16. . The results of this study confirm the challenge of the effectiveness of participation emphasized by both national and international literature. In this sense, this research has raised diverse opinions on the subject of influence, especially considering that the participants' previous experiences, their achievements and the relationships they establish with government agencies can influence their perception of participation and the existing political formulations.

Despite the data presented so far, which point out gaps in the participatory culture components, there was a positive aspect reported and emphasized by the councilors: the MHC achievements.

According to the participants of this study, during the 2009-2012 term, the Council achieved several achievements through its performance. Issues such as inauguration of Health Units, reforms, alteration of laws or codes and awards received were considered achievements, enabling councilors to visualize the resolution of some actions, which may generate, therefore, motivation for the continuation of their work. In this perspective, the Council's actions should be disclosed externally in order to promote the gains with the participation.

According to the councilors, the MHC influence perception in improving the local health system contributes to the strengthening of a participatory culture among the population. They argued that they observed many advances in the people's health and attributed these achievements to the MHC openness, to the Council's president position and to the society's organization.

“We have achieved so much in this term, but not in the others, which had lots of bureaucracy. And this is due to the Secretariat openness, the secretary gave us space to work with him”. (C2)

When asked about their participation, the councilors stated that they participate, express themselves and are assisted in their requests. They also stressed the Council's openness and the guaranteed space they have to manifest.

“I consider my participation 100%, I don't give up, (...) I oversee 100%. I can manifest myself within the council no doubt about it! (...) I don't come here to claim something that is not for the population, it's really necessary, I need a doctor in the unit, so where's the doctor? (...)”. (C3)

The MHC not always meets the popular claims

In contrast, other councilors stated that they participate, express themselves, sometimes they are assisted and at other times, they are not.

“I think my participation is good, I can defend my opinions, sometimes I can make it prevail, but sometimes not, but this is part of the game (...)”. (C5)

The statements also highlighted the councilors' association between social participation and the possibility of State supervision, as well as the use of the tactic of withdrawing from the meeting by some councilors as a means of demonstrating their dissatisfaction with the decisions taken or because of their requests being declined. Yet, while many councilors declare that representatives do not fulfill their role of seeking the communities' demands, in assessing their own participation, they are satisfied and, if they do not, blame their dissatisfaction to the plenary of the Council for failing to meet the demands.

However, the councilors also pointed out that the general population loses the incentive to participate because they often do not have their claims respected when they take their needs to the MHC.

“There is now a setback in the participation because the citizen ends up frustrated by not being familiar to this space and when they get to participate in a local health council, they end up making some claims that our rulers and managers do not respect, meaning that the important today is party politics (...) because they forget that power emanates from the people ”. (C1)

Lack of renewal of councilors

Another aspect that discourages popular engagement in the MHC issues is the lack of renewal of board members.

“I think the MHC works fine, but it has representativeness problems, they are always the same”. (C5)

However, with regard to the experiences and participation of the councilors, in general, there was a positive evaluation both for the achievements and for the individual performance of the interviewed councilors.

Social participation: a culture in process of construction

Some participants related the difficulties of popular participation within the MHC to a cultural issue.

“ (...) of the 104 neighborhoods, only 30 have active associations. Of the 30, only seven sent candidates to participate in the Council (...) then this is a Brazilian typical participation, the Brazilian persons are not into participating (...). That is to say, the people do not feel responsible for their own history, (...), some changes occur, some signs that this new generation has a new consciousness, but it is still a very incipient movement. That's why the politician campaign is by giving soccer balls, dentures, it's that providing thing, it's the provider. You're going to vote for me because I'm going to help you whenever you need it”. (C5)

This statement corroborates the strong statesman culture in Brazil, in which people generally hold the state accountable for the solutions of their daily problems, accepting resignation, conformism and impotence. According to Gastal and Gutfreind 2828. Gastal CLC, Gutfreind C. Um estudo comparativo de dois serviços de saúde mental: relações entre participação popular e representações sociais relacionadas ao direito à saúde. Cad Saude Publica. 2007; 23(8):1835-44. , the State is perceived in its representations as an instance unconnected to the population, which is dominated: a sphere with physicians, public servants, politicians and employers, motivated by particular interests.

However, the construction of a participatory culture should not be attributed only to the relationship established with the State and rulers, since it also involves the context in which the subjects are inserted. Poor access to information, scarce resources and precarious infrastructure, as well as frustration in previous attempts at participation, contribute to undermining the interest and mobilization of civil society. Disinterest and social immobility, in turn, undermine the process of changing the context and participatory culture.

In summary, taking the schematic figure of dimensions and resources that influence the social participation elaborated by the WHO 22. Organização Mundial de Saúde (OMS). Diminuindo as diferenças: a prática das políticas sobre determinantes sociais de saúde: documento de discussão. Rio de Janeiro; 2011. , the MHC data collected and analyzed can be represented as follows:

: Interrelation between the findings of this study and the dimensions of the context and resources that influence social participation

Looking at the figure, about the conditions and elements for participatory culture in a MHC in a city of São Paulo, the components are deficient and popular participation is still precarious. The only positive elements reported by the councilors were those related to the MHC achievements, which, despite being important aspects for the increase of the participatory culture, are still little explored and disseminated. The literature emphasizes different elements that contribute to the quality and effectiveness of social participation, such as the political culture and the relationship of power among the MHC actors, which do not depend exclusively on information and communication about the developed activities. Furthermore, the councilors also highlighted these as relevant factors for the popular unfamiliarity of the Council's actions, negatively influencing the culture of participation.

Final remarks

Participatory culture, as a cultivation or care for the full realization of the population's political potential, still walks with timid steps. This study showed us that the biggest obstacles to be overcome are those related to the communication between the various actors and social institutions to make feasible the construction of participatory culture.

Considering communication and information as some of the elements that support participation, with respect to the dimensions and resources that influence it, the analyzed context characterizes with absences through lack of articulation with other government agencies, lack of quorum , lack of integration between the MHC and civil society, lack of infrastructure and resources, lack of training, lack of information, lack of renewal of councilors.

Thus, the participatory culture found obstacles related to the existence of asymmetric relations between interests and powers of the different actors involved in the studied MHC. These barriers are accentuated by lack of communication between the MHC and government, the MHC and civil society, and the difficulty of communication between civil society groups, and the precariousness of the population's information about the Council's actions and the councilors on the norms and dynamics of the MHC.

On the other hand, the councilors highlighted many achievements of the MHC, elements that could encourage the approach between the MHC and population. However, failure to disclose such actions undermines the process of "community empowerment". Expecting that the media alone is responsible for publicizing the achievements of the MHC and the popular demands is to pass on something to the other that is the responsibility and interest of both the Council and organized civil society.

Therefore, there are ways to stimulate participatory culture, many of them pointed out by the councilors: access to information, active search strategy of popular demands, permanent councilors training, improvement in the criteria for selecting councilors, change in the internal MHC regime with regard to the re-election of members, as well as financial support to representatives of the user segment (for transportation, hotel, etc.).

Another alternative for the MHC to establish positive relations with both the population and the government and favor a culture of participation may be the investment in the Local Health Councils (LHC). LHC are spaces close to communities, capable of generating bonds of belonging and elaborate projects with social groups. In addition to facilitating access to information and communication between the Council and population, proximity to the LHC can help the population to restore trust and demand from their representatives, thereby building a greater dialogue and awareness of their rights and democratic spaces to manifest and cultivate their culture of participation.

Referências

-

1Testa M. Pensar em saúde. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas, Abrasco; 1992.

-

2Organização Mundial de Saúde (OMS). Diminuindo as diferenças: a prática das políticas sobre determinantes sociais de saúde: documento de discussão. Rio de Janeiro; 2011.

-

3Tribunal de Contas da União (BR). 4a Secretaria de Controle Externo. Orientações para conselheiros de saúde. Brasília; 2010.

-

4Baquero M. Cultura política participativa e desconsolidação democrática – reflexões sobre o Brasil contemporâneo. São Paulo Perspec. 2001; 15(4):98-104.

-

5Chauí M. Cultura e democracia. Crít Emancip. 2008; 1(1):53-76.

-

6Carvalho SR. Os múltiplos sentidos da categoria “empowerment” no projeto de Promoção à Saúde. Cad Saude Publica. 2004; 20(4):1088-95.

-

7Lei n° 8.142/90, de 28 de dezembro de 1990. Dispõe sobre a participação da comunidade na gestão do Sistema Único de Saúde e sobre as transferências intergovernamentais de recursos financeiros na área saúde. Diário Oficial da União. 19 Set 1990.

-

8Cortes SMV. Construindo a possibilidade de participação de usuários: conselhos e conferências no Sistema Único de Saúde. Sociologias. 2002; 4(7):18-49.

-

9Van Stralen CJ. Conselhos de saúde: efetividade do controle social em municípios de Goiás e Mato Grosso do Sul. Cienc Saude Colet. 2006; 11(3):621-32.

-

10Oliveira VC. Comunicação, informação e participação popular nos conselhos de saúde. Saude Soc. 2004; 13(2):56-69.

-

11Serapioni M. Os desafios da participação e da cidadania nos sistemas de saúde. Cienc Saude Colet. 2014; 19(12):4824-37.

-

12Bardin L. Análise de conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70; 1995.

-

13Fleury S. Democracia, descentralização e desenvolvimento: Brasil e Espanha. Rio de Janeiro: FGV; 2006.

-

14Valla VV, Stotz EN, organizadores. Educação, saúde e cidadania. Petrópolis: Vozes; 1994.

-

15Coelho JS. Construindo a participação social no SUS: um constante repensar em busca de equidade e transformação. Saude Soc. 2012; 21 Supl1:138-51.

-

16Cohn MG. Empoderamento e participação da comunidade em políticas sociais. Saude Soc. 2004; 13(2):20-31.

-

17Cotta RMM, Martins PC, Batista RS, Franceschinni SCC, Priore SE, Mendes FF. O controle social em cena: refletindo sobre a participação popular no contexto dos conselhos de saúde. Physis. 2011; 21(3):1121-37.

-

18Duarte EB, Machado MFAS. O exercício do controle social no âmbito do conselho municipal de saúde de Canindé, CE. Saude Soc. 2012; 21 Supl1:126-37.

-

19Cruz PJSC. Desafios para a participação popular em saúde: reflexões a partir da educação popular na construção do conselho local de saúde em comunidades de João Pessoa, PB. Saude Soc. 2012; 21(4):1087-100.

-

20Silva EC, Pelicioni MCF. Participação social e promoção da saúde: estudo de caso na região de Paranapiacaba e Parque Andreense. Cienc Saude Colet. 2013; 18(2):563-72.

-

21Alencar HHR. Educação permanente no âmbito do controle social no SUS: a experiência de Porto Alegre-RS. Saude Soc. 2012; 21 Supl1:223-33.

-

22Ventura CAA, Mello DF, Andrade RD, Mendes IAC. Aliança da enfermagem com o usuário na defesa do SUS. Rev Bras Enferm. 2012; 65(6):893-8.

-

23Faria EM. Comunicação na saúde: fim da simetria? Pelotas: Ed. Universitária; 1996.

-

24Soratto J, Witt RR, Faria EM. Participação popular e controle social em saúde: desafios da Estratégia Saúde da Família. Physis. 2010; 20(4):1227-43.

-

25Entwistle VA. Public involvement in health service governance and development: questions of potential for influence [editorial]. Health Expect. 2009; 12(1):1-3.

-

26Labra MH. Política nacional de participação na saúde: entre a utopia democrática do controle social e a práxis predatória do clientelismo empresarial. In: Fleury S, Lobato LVC, organizadores. Participação, democracia e saúde. Rio de Janeiro: Cebes; 2009.

-

27Bispo Júnior JP, Gerschman S. Potencial participativo e função deliberativa: um debate sobre a ampliação da democracia por meio dos conselhos de saúde. Cienc Saude Colet. 2013; 18(1):7-16.

-

28Gastal CLC, Gutfreind C. Um estudo comparativo de dois serviços de saúde mental: relações entre participação popular e representações sociais relacionadas ao direito à saúde. Cad Saude Publica. 2007; 23(8):1835-44.

-

Erratum

In the article “Participatory culture: citizenship-building process in Brazil”, DOI number: 10.1590/1807-57622015.0941, published in the journal, Interface - Comunicação, Saúde, Educação, 2017; 21(63):907-20, at page: 907:Where it reads:(c) Pós-doutorando, Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia de Portugal. Lisboa, Portugal. mauroserapioni@ces.uc.ptReads up:(c) Pós-doutorando, Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia de Portugal. Investigador, Centro de Estudos Sociais, Universidade de Coimbra. Coimbra, Portugal. mauroserapioni@ces.uc.pt

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

22 June 2017 -

Date of issue

Oct-Dec 2017

History

-

Received

23 Dec 2015 -

Accepted

30 Nov 2016

Source: WHO, 2011

Source: WHO, 2011