Abstracts

OBJECTIVE: Revision and questioning of orthodox principles regarding the conduction of nerve impulse. DESIGN: Retrospective study with clinical analysis of results. SITE: Hospital das Clinicas (HCFMSP), public university institution with research programs and tertiary attention to health. GROUP MEMBERS: Author and a team of residents and trainees. OPERATION: Direct suture of nervous stumps utilizing auxiliary technical procedures:- joint-flexion, nerve transposition, tendon transplants, bone shortening. MEASUREMENT: Clinical evaluation and objective tests for tactile and stereognostic function recovery (WeberTest). RESULTS: Variable, depending on preoperative conditions: - type of lesion, time elapsed since injury. CONCLUSIONS: Neurorrhaphy should be the procedure of choice even for long term lesions, although the expected results may be less favourable. Periodical evaluation from 24 hs. postoperative, checking for early undefined signals of nervous function recovery. Association of specific drugs for chemical biophysics of the nerve.

Peripheral nerves; Accidents; Injuries; Compression syndromes; Hand surgery

OBJETIVO: Revisão e questionamento dos principais ortodoxos da transmissão do influxo nervoso. DESENHO: Estudo retrospectivo com análise clínica dos resultados. LOCAL: Hospital das Clínicas (HCFMUSP), instituição pública universitária com programa de pesquisa e atenção terciário à saúde. PARTICIPANTES: Autor e equipes de Residentes e estagiários. INTERVENÇÃO: Sutura direta dos cotos nervosos lançados mão de artifícios técnicos auxiliares: flexão de articulações de nervos, transplantes tendinosos, encurtamento ósseo. MENSURAÇÃO: Avaliação clínica associada a testes objetivos de recuperação da função táctil e estereognóstica (teste de Weber). RESULTADOS: Variáveis de acordo com as condições pré-operatórias, tipo de lesão, tempo decorrido desde o acidente. CONCLUSÕES: Deverá ser feita a neurorrafia, mesmo nos casos antigos, apesar do prognóstico menos favorável. Avaliação periódica desde as 24 hs, do pós-operatório, pesquisando sinais precoces mal definidos de recuperação da função nervosa. Associação de medicação específica para a bio-físico-química do nervo.

REVIEW ARTICLE

Upper extremity nerve lesions (diagnosis, indications, surgical techniques)

Lauro Barros de Abreu

University of São Paulo Medical School - São Paulo, Brazil

Address for correspondence Address for correspondence: Lauro Barros de Abreu Alameda Lorena, 965 - Apto 131 São Paulo/SP - Brasil - CEP 01424-001

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE: Revision and questioning of orthodox principles regarding the conduction of nerve impulse.

DESIGN: Retrospective study with clinical analysis of results.

SITE: Hospital das Clinicas (HCFMSP), public university institution with research programs and tertiary attention to health.

GROUP MEMBERS: Author and a team of residents and trainees.

OPERATION: Direct suture of nervous stumps utilizing auxiliary technical procedures:- joint-flexion, nerve transposition, tendon transplants, bone shortening.

MEASUREMENT: Clinical evaluation and objective tests for tactile and stereognostic function recovery (WeberTest).

RESULTS: Variable, depending on preoperative conditions: - type of lesion, time elapsed since injury.

CONCLUSIONS: Neurorrhaphy should be the procedure of choice even for long term lesions, although the expected results may be less favourable. Periodical evaluation from 24 hs. postoperative, checking for early undefined signals of nervous function recovery. Association of specific drugs for chemical biophysics of the nerve.

Uniterms: Peripheral nerves. Accidents. Injuries. Compression syndromes. Hand surgery.

RESUMO

OBJETIVO: Revisão e questionamento dos principais ortodoxos da transmissão do influxo nervoso.

DESENHO: Estudo retrospectivo com análise clínica dos resultados.

LOCAL: Hospital das Clínicas (HCFMUSP), instituição pública universitária com programa de pesquisa e atenção terciário à saúde.

PARTICIPANTES: Autor e equipes de Residentes e estagiários.

INTERVENÇÃO: Sutura direta dos cotos nervosos lançados mão de artifícios técnicos auxiliares: flexão de articulações de nervos, transplantes tendinosos, encurtamento ósseo.

MENSURAÇÃO: Avaliação clínica associada a testes objetivos de recuperação da função táctil e estereognóstica (teste de Weber).

RESULTADOS: Variáveis de acordo com as condições pré-operatórias, tipo de lesão, tempo decorrido desde o acidente.

CONCLUSÕES: Deverá ser feita a neurorrafia, mesmo nos casos antigos, apesar do prognóstico menos favorável. Avaliação periódica desde as 24 hs, do pós-operatório, pesquisando sinais precoces mal definidos de recuperação da função nervosa. Associação de medicação específica para a bio-físico-química do nervo.

INTRODUCTION

Upper extremity nerves are often injured. Epidemiological studies of these accidents, their effects on manual labor and the inherent socio-economical and psychological aspects, are very important.1

The mechanization of modern life both in the cities and in rural areas, the use of machinery and tools at home, in the factories and in the fields, the sophistication of modern transport and the invasion of homes by electrical and electronic appliances have contributed in a great scale to the increase in the accident rate.

A high price is being paid for this improvement in the standard of living

Preventive measures and campaigns, especially at work, have slightly improved the situation, although the "Zero accident" slogan, still remains utopic.

The only alternative, therefore, is the improvement of treatment procedures in order to eliminate or at least minimize long term effects.

Peripheral nerve surgery has been practiced for nearly a century but only during the last fifty years has there been a major development in this branch of surgery.

Paradoxically, the great contributors to this development have been the wars.

Soon after the end of World War II, the return to the USA of "avalanches of injured and crippled soldiers", in the crude but justified words of Bunnell, forced General Norman T. Kirk., at the time Chief of the Health Care Services of the Armed Forces, to request emergency measures to tackle the problem.

Nine special centres were set up to handle these cases.

In 1946, specialized surgeons located in these centres, under the leadership of Bunnell, founded the American Society for Hand Surgery. Similar organizations were quickly founded in other countries and Hand Surgery became a specialized branch of medicine throughout the world.

The Brazilian Society for Hand Surgery was founded on June 17th, 1959.

HISTOLOGY 2,3

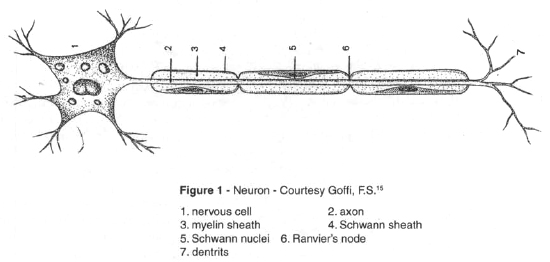

The nerve is formed by neurons and its axons (axocylinders, neurofibriles or nerve fibers) (Fig. 1, 2).

Some nerve fibers are covered by a whitish fatty sheath, the myelin (myelinic or medullary fibers). Others are devoid of this sheath (unmyelinated fibers).

The myelin sheath has minute gaps in its diameter - the nodes of Ranvier (Fig. 1, 2).

The myelin sheath is covered by another sheath (the neurilema or Schwann sheath) with its nuclei (Fig. 1, 2).

Neurofibriles form nervous bundles (funiculi), bound inside the connective tissue (endoneurium), separated from each other by the perineurium. The whole nerve is surrounded by a fibrous sheath, the epineurium (Fig. 2).

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOPATHOLOGY

Nerves are cylindrical whitish structures, variable in size and length, through which nervous impulses flow to the muscular , glandular and other nervous cells.

In the upper extremities the nerves connect the central nervous system to the distal parts (hands), through afferent and efferent stimulation, from the sensory organs to the cortex . For this purpose these nerves are mixed, with motor and sensitive fibers in variable proportions, and also with a varying topography along its course. 4,5

Traumatic lesions to the nerves of the wrist are very frequent and are usually associated with vascular lesions.6,7

The trauma may be slow and progressive, constant or intermittent, causing traumatic neuritis.8-10 The most frequent are the carpal tunnel syndrome (median nerve),11-14 the ulnar neuritis in the epitrochleo-olecranean groove generally in the valgus elbow15 and other sites.

Compression may be inside the nerve (interstitial neuritis), as in the Hansen disease 16, in the Déjérine-Sottas disease17 and many others.

The brachial plexus, located in the lateral side of the neck and supra-clavicular region, is formed by roots from the cervix (C5) to the first dorsal (TI).4, 9

Trunks and nerves of the brachial plexus on its way down and outwards to the distal part of the limb form a net with an X-like figure, with its center under the clavicle, in the so-called costo-clavicular or cervicoaxilliary canal, the isthmus of the brachial plexus. In addition to the nerves, the subclavean artery and vein run through this canal.

This narrow passage is part of the mobile osteo-articular compound of the shoulder blade and first rib.

Under certain circumstances, with alterations of the position of certain components, this passage becomes even narrower under strain creating a critical situation in its inner structure.

Abnormal structures (cervical ribs)18 are sometimes present in this region, mega-apophysis, ligaments, muscles, fibrous bands and/or spondylosis,19 disk lesions and others which may compress the brachial plexus causing cervicobrachialgies and/or vascular problems.

Brachial plexus may be pushed downwards by external traction, such as a bad posture and/or the carrying of heavy loads.

Age, due to the weakening of the body structures, may cause the shoulder to fall. In a similar manner, the flaccidity of the chest and abdominal muscles, obesity or the increase in the weight of the abdominal and pelvic tumors and pregnancy are frequent internal factors.

In some cases the plexus lesion may be iatrogenic, due to awkward obstetrical manoeuvres when the head of the foetus is pulled downwards during childbirth (obstetrical paralysis).20

Gunshot or stab wounds of the plexus present no major problem, except if extensive and in a site of difficult access.

However, lesions due to violent traction, such as those caused by falls on the head with trunk rotation (motorcycle accidents), may represent a serious problem. The traction, strain, tearing and avulsion of the roots require very complex procedures.21

DEGENERATION - REGENERATION

Following injury, the process of degeneration in the distal stump (wallerian degeneration) and regeneration in the proximal stump begins.2

Between the nerve stumps scar tissues are formed which make repair incomplete and disorganized. In the proximal stump an intumescence is formed, a neuroma. In the distal stump a larger one is formed the glioma or neuroglioma.

Occasionally between the two stumps some axons are able to get through the scar tissue barrier and a partial repair of the nerve occurs.

Axons regeneration takes place distalwards, quicker in the first three weeks (3 to 5 millimetres/day) slowing down later to 1 millimetre/day, giving an average repair rate of 1 to 2 millimetres/day.

CLASSIFICATION OF LESIONS

Interruption, physiologic block, concussion, contusion, compression and other denominations were used to describe lesions to the nerves, creating confusion and complicating treatment procedures.22

As the nerves are comprised of many elements, each with its own specific function, a classification became necessary to organize the lesions according to their effects on the main structures.

The classification proposed by Seddon with the objective Greek terminology suggested by Cohen is the following:

Neurotmesis

Axonotmesis

Apraxia.

Some authors include Neurostenosis when there is internal axon compression. (Fig. 3) 15, 23

Neurotmesis means complete division (nerve transsection).

Axonotmesis means division of the axons, with no damage to the Schwann sheath.

Apraxia (neurapraxia) is just a functional lesion.

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis must be the result of a long and thorough clinical examination.23 Laboratory and other tests, such as X-ray, electromyography, electro-neuromyography, computarized tomography, magnetic resonance and others may be requested later, if necessary.

Obvious lesions constitute no problem. But the association for instance, of congenital anomalies in hands4 or forearms with cervical lesions18 may preclude diagnosis.19

Functional and structural high compressions, permanent or intermittent, may mimic lesions to the elbow, forearm and, hand; whereas distal lesions such as carpal tunnel or Guyon canal syndromes may cause damage to the elbow, arm and shoulder.24

In order to avoid mistakes and consequently wrong treatment indications, the diagnosis should be as precise as possible.25,26

A properly directed anamnesis and a careful assessment of the patient's general condition and complaints, is very important. We should not forget the patient's psychological profile, the basis of all human behaviour.

TREATMENT INDICATIONS

In the treament of nerve lesions various techniques and procedures, either alone or combined, must be considered.27,28 The general treatment plan will depend on the diagnosis, which, as already mentioned, is not always easy.

Axonotmesis and neurapraxia do not require surgical treatment as there is no damage to the Schwann sheath.

However, neurotmesis, with damaged structures, requires surgical treatment.

A conservative treatment , utilizing physical means and technical support may precede, complement or even substitute surgical treatment..

An example of this type of conduct is obstetric palsy, caused by traction of the roots with varying degrees of intensity depending on the extent of the trauma. The best initial approach should be the conservative one, with adequate positioning (elevated hand, abduction of the shoulder and external rotation of the arm). In the majority of cases there is a spontaneous recovery; only when this does not occur should other treatment methods be considered.29,30

The compression of a limb with a non-pneumatic tourniquet can provoke paralysis, i.e. an apraxia (temporary lesion).31

Whenever there is a violent localized compression an axonotmesis lesion may occur. Recovery, in these cases, is slow.

SURGICAL TIMING

Primary repair of the nerve is the ideal treatment,32-34 but certain conditions must be met; it must be done immediately.

In the prompt treatment of patients with open nerve lesions we must consider the aspects of each case, especially with reference to the time which has elapsed since the injury occured.

Primary repair is that done soon after the accident, within the first few hours. A typical example is an iatrogenic lesion caused by the surgeon during an operation, where the conditions are ideal.

As a safety measure we should consider that a primary repair is permissible when:

1. the wound is fresh, clean and regular;

2. the surgeon is well acquainted with the anatomy of the region, is well trained and in good physical and psychological conditions to perform a possibly long and tiring operation;

3. adequate instruments and all necessary equipment are available;

4. the operating theatre is adequate, well equipped and qualified surgical, general anaesthesia and nursing teams are available;

5. the patient is prepared for a long surgery under general anaesthesia;

6. primary repair is obviously obligatory when the nerve is cut accidentally by the surgeon during an operation. All conditions are present and the error has to be corrected at once.

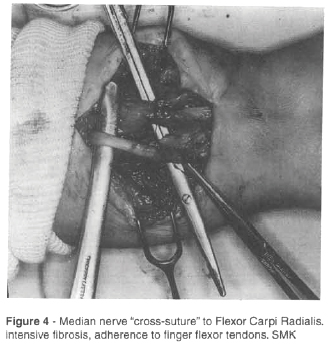

These are the main requirements to avoid unfortunate mistakes, not uncommon even in well developed countries. The well known "classical suture"32 or the "midnight suture" is one of these mistakes33 (Fig. 4). These serious mistakes usually occur at the end of a duty stretch, caused by tired and unskilled surgeons.

Primary delayed suture (the "Urgency deferrée" of the French) is the repair performed after the time limit (6 hours), owing to usual difficulties, such as: unavailable full staff, ill-prepared patient, patients; with multiple injuries and others. This delayed treatment is justified inasmuch as it allows the correction of certain conditions thus guaranteeing the safety of the patient.

The third week, with the skin in good conditions, when axon regeneration rate is high, is the appropriate time for reparatory surgery. This is the early secondary repair.9,24,32-34

Long delayed repair of nerve lesions, sometimes months or years later, should not be condemned.9,35-38

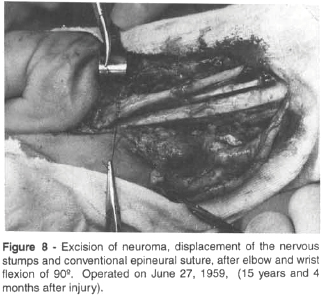

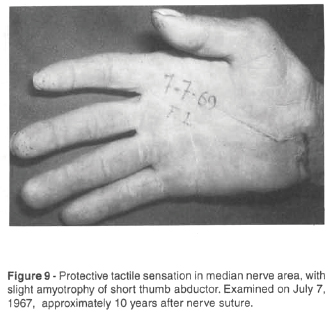

Although expected results, depending on the time elapsed, may be poor, the improvement of local trophic conditions, with healing of ulcers, reduction of edema and the establishment of slight protective sensations, justifies this procedure which is greatly beneficial to the patient (Fig. 5, 6, 7, 8 , 9, 10).

SURGICAL NERVE REPAIR TECHNIQUES

Neurolysis is the freeing of the nerve. It can be external, as in the case of scar compression or bone callous.

The compression factor may be inside the nerve,as in intersticial neuritis or lesions in continuity. In these cases internal neurolysis is obtained by "combing" the nerve fasciculi or by excising fibrous tissue through partial epineurium resection (Fig.11).

In the nerve transsection, the suture (neurorrhaphy) using the conventional approach, consists of the loosening of the stumps and suture of the epineurium39. The normal topography of the nerve should be maintained as far as possible.4,22 A non-tension suture should be done in the epineurium, with separate stitches, thus avoiding fibrosis between the nerve stumps (some authors do not agree with this procedure).40

The objective is to allow a wrapping which may serve as a guide to the progression of the axons during regeneration.

Before proceeding with the neurorrphaphy, the stumps are sectioned to allow suture in healthy tissue, the aspect is similar to a telegraphic cable, with minimum alterations in the internal topography of the nerve (Fig. 12).

In the case of neuroma fusiform or intraneural, the resection of the neuroma is also performed, trying to maintain as much as possible of the healthy part of the nerve.

The resection of lateral neuroma may be done apart from the neuroma with suture only of the area of the lesion.

The suture threads may be of various types, but should be innocuous, very fine, monofilaments and mounted on cylindrical atraumatic needles. The glycolic acid threads, 41,42 number 8 to 10/0, have now substituted the old materials (silk, nylon, steel, tantalum and even human hair)5 (Fig. 13,14).

Possibly, instead of the suture of the epineurium, fixation of the stumps may be done with adhesives.43-47

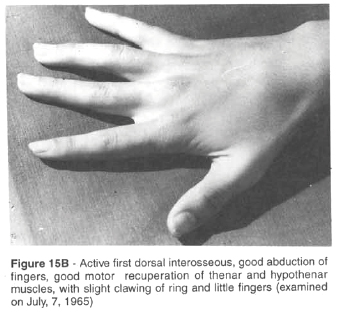

Delicate instruments and gentle manipulation of the nerve stumps are of great importance. Atraumatic technique, refraining from nipping the nerve with forceps, is only permitted on neuromas to be excised. The nerve may, under certain circumstances, be gently manipulated by the surgeon's fingers (Fig. 15).

In October 1952, assisting Pulvertaft in an operation, we did for the first time that which we now do on a routine basis: a delicate massage on the suture line of the nerve, with the thumb and index fingers , similar to rolling a cigarette between the fingers. He approved the technique and named it "Abreu's manoeuvre" (Fig. 15a, 15b).

Nerve grafts are used to fill large gaps,48-50 allowing a "non-tension suture".

The suture technique is the same as that for neurorrhaphy (Fig. 16).

When nerve and graft have different diameters, grafts are joined in bundles with stitches - "cable graft".9,49

In these cases, instead of suture with threads, especially in brachial plexus lesions an adhesive (fibrine glue or human plasma) is used. This type of adhesive was not used during many years.

The graft donor source is usually a segment of the sensitive nerve, either the sural nerves, the medial cutaneous nerve of the arm or forearm.

Some authors recommend the use of homografts. 45,51

Interfascicular or interfunicular grafts, proposed by Hashimoto (1917), Langley (1918) and Sunderland (1943) came back into use.52-56

Fasciculi are held together by only one stitch, with epineurum excision. The value of this procedure is still under discussion..

The technique is very delicate, requiring the use of magnifying lenses (2,6x) or microscopes (12,15x, or less) (Fig.17).

Sometimes, pedicle nerve graft57,58 may be used in the forearm, in especially difficult cases of double injury to median and ulnar nerve.

Neurotomy and neurectomy are not nerve repair techniques. They consist of the sectioning of a nerve with the purpose of minimizing or interrupting completely its function59,60

Neurotomy is a simple nerve division; neurectomy is a double division, with excision of the middle part, to avoid regenerative bridging.

It may be used to control muscle spasm as a palliative treatment in painful syndromes and in cerebral palsy.

Neurectomy is used frequently in large and painful neuromata in amputation stumps.

Neurotization is an old technique used to stimulate paralysed muscles, by implanting nerves into the muscular body in severe lesions, mainly in the brachial plexus.61, 62

ALTERNATIVE TECHNIQUES

Simultaneous muscle or musculotendinous transplants are sound procedures to replace or reinforce muscular function. Nerve function recovery is never complete.63-66

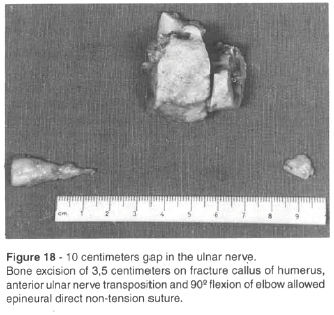

Nerve transsection with 2 or more centimetres gap is a challenge to the surgeon, who must face a dilemma: graft or bone shortening and direct suture.67-78

Both approaches have advantages and disadvantages.

The graft allows a non-tension nerve suture but creates two barriers to axon progression, and the defect in donor area must be considered.

Bone resection allows direct non-tension suture of the nerve. A less important tissue (bone) is sacrificed on behalf of a more important one (the nerve). A few centimetres shortening of an upper limb represents no problem.

For median and radial cases the resection is done at the diaphysis of the humerus, with immediate osteosynthesis in the cases of the radial, median and ulnar nerves (Fig. 18).

For ulnar cases, an easier technique is used: - transposition of the nerve from the epitrochleo-olecranean groove, shortens the course of the nerve. This technique can easily compensate for the loss of a two or more centimeters.8

In severe and extensive lesions to the forearm, arthrodese of the wrist with bone resection or resection of the first row of carpal bones are indicated.

Bone resection is a routine technique in limb reimplantation 75

DISCUSSION

In the surgical recovery of the nerves of upper limbs, two factors assume great importance: - microsurgery76,- 78 and new materials for the fixation of nerve stumps.

The use of microsurgery, with the aid of magnifying glasses and microscopes allows a clear view of the fine structures of the nerve and consequently a more precise reconstitution.

The fixation of the nerve stumps also improved greatly with the use of new suture threads,79 monofilaments, delicate, resistant and innocuous (many are reabsorbed by the body), attached to delicate cylindrical needles.41,42

In the plexus, in cases of severe lesions of difficult access, it is often necessary to use adhesives which make the reparation of the nerve stumps easier.43-47

CONCLUSIONS

With the facilities created by microsurgery, we have seen remarkable work done by determined surgeons whose enthusiasm has been boundless, a true saga challenging nature.80-88

Nerve graft is being widely used, replacing the conventional techniques - neurorraphy, plain suture.

But nerve graft, besides the problems inherent to the donor site, has another more serious problem - the second suture, a new barrier to be overcome by the axon in regeneration.81

Interfascicular (or interfunicular) sutures and grafts are unrealistic.

The task of repairing the minute, specific and peculiar structures is notable due to its details, a real Chinese art.

Optical magnification of those delicate structures with the aid of lenses, microscopes and computers has become routine.

Highly skilled surgeons, well trained medical and paramedical staff at specialized hospitals, the instruments, equipments and implements available enable the conduct of surgical operations using state-of-the-art technology, real high tech surgery.

Unfortunately, however, despite all the means available, the recovery of the nerve function has been only partial, not complete. This fact is recognized by many specialists and recorded in medical literature.81,82

Microsurgery, introduced in the sixties, is indispensable for the repair of vessels and microstructures of other parts of the body, such as the brain, spinal cord, eyes, ears and others. It is invaluable for the reconstruction of very fine nerves of the upper limbs, in the intraneural neurolysis or in grafts located in difficult sites such as in the branchial plexus. Microsurgery is greatly dependent on the surgeon's visual acuity.

Nevertheless, microsurgery should not be considered, as has been the case so far, as a miraculous resource, capable of solving all problems.

In our opinion, one that we have been expressing for a long time, this current approach is not the right one; it seems they have come to a "dead-end track" away from the "main road".

For a long time we have been questioning our patients, from the first day after the operation.

"I feel my finger (or hand) better", is the invariable reply. Vascular, sympathetic or nerve reaction?

We have come to the conclusion that, as with split electrical cords when put together, "the current flows". 89

We firmly believe that sectioned nerves should be repaired, regardless of the time which has elapsed since the lesion,37 even if bone shortening is required in severe cases.37, 38, 67-78

We insist in conventional epineural non-tension sutures.

The main steps of the operation are:

Displacement and freeing of the nerve stumps, slight traction on the nerve,9 if necessary, adequate flexion of the neighbouring joints, rerouting of the nerve to reduce the gap as in the ulnar nerve in the elbow.28

Clinical observation has led us to question the current nerve regeneration dogmas. Research in the biomedical sciences area and the like should be increased and conducted in greater depth.

Thus we suggest the maintenance of the conventional techniques with direct suture of the nerve, associated, if necessary, to alternative procedures, complemented with new data originating in current clinical studies in the areas of basic sciences (histoneurophysiopathology, chemical biophysics and related disciplines.90,92

With this global view of the problem, we must meditate on the depth and wisdom of the words written more than one hundred years ago but which still apply today:

"There is dead medical literature, and there is a liong one. The dead is not all ancient, and the live is not all modern".

OLIVER WENDELL HOLMES (1809 -1894)93

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our sincere thanks to Heloisa Abreu Dib, whose dedication and professionalism made this work possible.

- 1. Abreu LB. Clinical aspects of muscle imbalance in the hand due to ulnar nerve lesions. Anatomia Clínica, Springer Verlag, 1984, 6:177-182.

- 2. Junqueira LC, Carneiro J. Histologia básica. Ed. Guanabara Rio de Janeiro,1990, 131,136.

- 3. Schumacher S. Compêndio de histologia humana. Editorial Labor S.A.,3ª ed., Barcelona, Madrid, 1948,73-75.

- 4. Foerster O. Anatomie und Physiologie der peripheren Nerven in Handbuch der Neurologie, Berlin, Julius Springer Verlag,1929, 50b.

- 5. Seddon HJ. Three types of nerve injury. Brain,1943, 66 (4):237.

- 6. Abreu LB. Reparação secundária por enxerto tendinoso das lesões traumáticas dos tendões flexores dos dedos dentro da bainha osteofibrosa (experiência de 110 casos operados). 1959Thesis FMUSP, São Paulo.

- 7. Graner O. Lesões traumáticas dos nervos. In Atualização Terapêutica, Liv.Luso-Esp. e Brasileira Ltda., São Prado J., Ramos J., Vale JR., 1958:791-793.

- 8. Spinner M., Spencer FS. Nerve compression lesions of the upper extremity. Clin. Orthop., 1974,104:46.

- 9. Bunnell S. Surgery of the hand, 2nd.ed., JB Lippincott Co., Phil., London, Montreal,1948.

- 10. Leite VM. Sindrome compressiva do nervo interosseo posterior. Diagnostico e tratamento. 1988, Thesis EPM-UNIFESP, São Paulo.

- 11. Eversmann WV.(Jr) Compression entrapment neuropathies of the upper extremity. Hand Surgery, 1986,8 (5):759-766.

- 12. Lech O. A dor de braço. Proteção,2:120-123.

- 13. Abreu LB., Godoy-Moreira R. Median nerve compression at the wrist. J Bone J Surg, 1958,40A, 96:1426-1427.

- 14. Kojima T, Ide, Y. et al. Hemangioma of median nerve causing tunnel syndrome. The Hand, 1976,8 (1):62-65.

- 15. Abreu LB. Cirurgia dos nervos periféricos. In Goffi FS.-Técnica Cirúrgica.Livraria Atheneu, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, 1978:309-315.

- 16. Abreu LB. Cirurgia da mão nas lesões nervosas da lepra. Actas y Trabajos del III Congresso Argentino de Ortopedia y Traumatologia, Mar del Plata, 1961,2:199.

- 17. Iacovone M, Julião OF, Abreu, LB. Molestia de Dejerine-Sottas. III Jornada SBCM, Rio de Janeiro,1963.

- 18. Wolosker M. Tratamento da costela cervical. 1972, Thesis FMUSP, São Paulo.

- 19. Carvalho RDD Espondilose cervical; indicações e resultados no tratamento da mielopatia. 1974, Thesis Fac Med Santa Casa de São Paulo.

- 20. Abreu LB. Traumatismos do recém-nascido. Rev. Maternidade e Infância, 1953,12:211-224.

- 21. Azze RJ. Tratamento microcirúrgico das lesões traumáticas do plexo braquial. 1991, Thesis FMUSP,São Paulo.

- 22. Seddon HJ. A classification of nerve injuries. Brit.Med.J., 1942,2:237.

- 23. Palazzi Colli S, Palazzi Colli C. Diagnóstico. In Cirurgia de los nervios perifericos. III Congresso Nacional de la SECOT,1972, Madrid.

- 24. Littler JW. The Hand and Wrist in Howarth MB. Text book of orthopedics. WB Sanders Co., Phil, London, 1952,261.

- 25. Moberg E. Akute Handchirurgie-Köln, Lindenthal, Joseph Schumpe, Lund-CWK,Gleerup,Bokfortag,1953,p.9.

- 26. Caetano EB. Contribuição ao estudo da inervação dos musculos tenares e da anastomose de Canieu e Richet.1982,Thesis- Fac.Med., PUCSP, Sorocaba.

- 27. Abreu LB. Cirurgia dos nervos periféricos. In Carvalho RRD, Neurocirurgia, Sarvier, São Paulo,1979,119-134.

- 28. Gonçalves DC. Aspectos da cirurgia dos nervos periféricos. Rev.Med Municipal,Rio de Janeiro, 1957,24(4):253-270.

- 29. Peixinho M.. Tratamento cirúrgico das contraturas em aduação e em rotação interna do braço nas sequelas da paralisia obstétrica. 1970, Thesis FMUSP,São Paulo.

- 30. Peixinho M.. Tratamento cirúrgico das sequelas da paralisia obstétrica. 1971, Thesis FMUSP,São Paulo.

- 31. Moldaver J. Tourniquet paralysis syndrome.AMA, Archives Surg.,1954,68:136-144.

- 32. Littler JW. Median and ulnar nerve injuries. In Reconst. Surg. and Traumatology, 1953,1:227-240.

- 33. Abreu LB. Reparação primária de nervos e tendões na mão. Rev Hosp Clin, 1959,14(3):160-166.

- 34. Abreu LB. Pronto-atendimento de acidentados de mão. IMESP, São Paulo,1993.

- 35. Davis L. Neurological surgery through the years of World War II.In Abst Surg Gynec Obst, 1949,89(1),1-23.

- 36. Kirklin JW,Berkson J. Suture of peripheral nerve. In Abst. Surg. Gynec. Obstet. 1949,88 (6),719-730.

- 37. Abreu LB, Erhart EA. Considerações sobre neurorrafias em lesões antigas. Rev. Paulista de Medicina -1950,52(2):149-150.

- 38. Wertheimer P, Auet J. Les paralysies radiales dans les fractures fermées de la diaphyse humerale. Sem Hop. Paris. Ann.Chir. 11:675,1957. In. Abst Surg. Gynec. Obstet.1958, 106(4)390.

- 39. Azze RJ. Lesões de nervos in Pardini AG. Traumatismo da mão. Médica e Científica, Rio de Janeiro, 1985,189-197.

- 40. Clifton EE. Tension at the suture line in peripheral nerve surgery. Surgery, 1949,26:756.

- 41. Bratton BR, Kline DG, Hudson AR, Coleman WT. The use of monofilament polyglycolic acid suture for experimental peripheral nerve repair. Surg Res. 1981, 31:482.

- 42. Sunderland S, Smith GK. The relative merits of various materials for the repair of severed nerves. Austral. / N.Zealand J.Surg., 1950,20:85.

- 43. Medawar PB, Young JZ. Fibrin suture of peripheral nerves. Lancet, 1940,126.

- 44. Seddon HJ, Medawar PB. Fibrin suture of human nerves. Lancet 1942,143:87-88.

- 45. Davis L, Rude D. Functional recovery following the use of homogenous nerve grafts. Surgery,1950,27:102.

- 46. Mattar (Jr) R. Reparação microcirúrgica dos nervos periféricos;estudo comparativo entre sutura epineural e adesivo de fibrina..1989 Thesis FMUSP,São Paulo.

- 47. Freeman BS, Perry J, Brown D. Experimental study of adhesive surgical tape for nerve anastomosis. Plast Reconst Surg, 1969,43:174.

- 48. Seddon HJ. Surgery of nervous system.The use of autogenous grafts for the repair of large gaps in peripheral nerves. Brit. J. Surg., 1947,35:151.

- 49. Seddon HJ. Peripheral nerve injuries. Medical Research Council, Her Majesty's Stationery Office (special series), London, 1954, 282.

- 50. Terzis J, Faibisoff B,Williams H. Nerve gap; suture under tension vs. graft. Plast. Reconst. Surg., 1975, 56:166.

- 51. Rezende N. Enxerto de cadáver em Cirurgia Humana. Bol Col Brasileiro de Cirurgiões, 1944,19 (I).

- 52. Sunderland S. Funicular suture and funicular exclusion in the repair of severed nerves. Brit J. Surg.,1953, 40:580.

- 53. Millessi H, Berger A. The interfascicular nerve grafting of the median and ulnar nerve. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 1972, 52A:727-750.

- 54. Ferreira MC,Azze RJ, Abreu LB. Enxerto funicular de nervo com técnica microcirurgica. Rev. Paul. Med. 1975, 86:113-116.

- 55. Millessi H,Meissel G,Berger A. Further experience with interfascicular graft of median, ulnar and nerve. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 1976, 58A,209.

- 56. Bratton B,Kline DG,Hudson AR. Experimental interfascicular nerve grafting. J. Neurosurg, 1979,51:323.

- 57. Strange FGStC. An operation for nerve pedicle grafting; preliminary communication. Brit. J: Surg.,1947, 34:423.

- 58. Alpar EK, Brooks DM. Long term results of ulnar to median nerve pedicle graft. Hand Surg., 1978, 10:61.

- 59. Fusco EB. Paralisia cerebral; correção do espasmo de flexão dos dedos e do punho pela neurectomia de ramos do mediano (pesquisa e resultados sobre 45 casos operados). 1964, Thesis FMUSP, São Paulo.

- 60. Carroll RE,Craig FS. The surgical treatment of cerebral palsy. Surg. Clin. N. Am.,1951, 31(2):385-395.

- 61. Nutt JJ. Neurotization of paralised muscle grafting. A laboratory and clinical study. J. Bone J. Surg., 1918, XVI (5),May.

- 62. Narakas A. Les neurotisations on transferts nerveux dan les lesions du plexus brachial. Ann. Chir. Main, 1982, 1:101.

- 63. Hamlin (Jr) E,Watkins AL. Peripheral Nerves-Regeneration in the ulnar, median and radial nerve. Surg. Clin. N. Am 1947, 27:1052.

- 64. Abreu LB. Neurorrafia e transplantes tendinosos simultaneos nas lesões nervosas do membro superior. Actas y Trabajos del III Congresso Argentino de Ortopedia y Traumatologia Mar del Plata, 1961, 1:186-189.

- 65. Moberg E,McDowell CL,House JH. Third International Conference on Surgical Rehabilitation of the Upper Limb in tetraplegia (Quadriplegia). Hand Surg., 1988, 1064-1066.

- 66. Abreu LB. Early restoration of pinch grip after ulnar nerve repair and tendon transfer. Hand Surg., 1989, 14B,3:309-314.

- 67. Massie WK, Ecker A. Internal fixation of bone and neurorhaphy-combined lesions of radial nerves and humerus fractures. J. Bone J. Surg., 1947, 20 (4):977-979.

- 68. Speed JS, Smith H. In Campbell's Operative Orthopedics. CVMosby Co., St Louis, 949, 2nd.ed., vol. 1.

- 69. Murphy P. Peripheral nerve injuries. In Campbell's Operative Orthopedics. Speed JS, Smith, H, 2nd. ed, CVMosby Co., St. Louis, vol. 1, chap. XI, 1949, p. 745.

- 70. Brown JB. Restoration of major defects in the arm by combination of plastic, orthopedic neurological procedures. Plast. Reconst. Surg., 1949, 4 (4): 337.

- 71. Evans EM. The treatment of major injuries in the hand. Brit.J. of Plast. Surg., 1949, 2 (3):150-174.

- 72. Nichols HM. Shortening the forearm for serious soft tissue loss about the wrist. J. Bone J. Surg., 1958, 40A, (4):958-959.

- 73. Goldner JL,Kelley JM. Radial nerve injuries. J.Bone J. Surg., 1958, 40A , (4):966-967.

- 74. Abreu LB. Encurtamento ósseo no tratamento das lesões nervosas graves do membro superior. Actas y Trabajos del III Congresso Argentino de Ortopedia y Traumatologia. Mar del Plata, 1961, I:190-185.

- 75. Costa RC. Implante de membros superiores (aspectos ortopédicos).1972,Thesis FMUSP, São Paulo p.52.

- 76. Smith S.W. Microsurgery of peripheral nerves. Plast. Reconst. Surg., 1964, 33:317-329.

- 77. Watson N, Smith RJ. Methods and concepts in Hand Surgery. Butterworth & Co. Ltd., 1986, London, Boston; Durban, Sidney, Toronto, Wellington.

- 78. Dick PJ,Thomas PR,Griffith L,Poduslo JF,Low PA. Peripheral neuropathy 3rd. ed., WB Saunders Co., Phil, London, Toronto, Sydney, Tokyo, 1993, 2:1678-1689.

- 79. Naffziger HC. Method to secure suture of peripheral-nerves. J. Orthopedic Surgery, 1921, 3 (7):348-349.

- 80. Sunderland S. Clinical and experimental approaches to nerve repair, in perspective. In Jewett DL, McCarrol (Jr) HR. Nerve and repair and regeneration. CVMosby Company, St. Louis, Toronto, London, 1980:37:337-355.

- 81. Milford L. In Bunnell Symposium, Jewett DL, McCarrol (Jr) HR Nerve repair and regeneration. CVMosby Co., St Louis, Toronto London, 1980, 36:329-336.

- 82. Edgerton NT. What's new in surgery. Surg. Gynec. Obstet., 1963, 116,:155-157.

- 83. Bora TFW. Peripheral nerve repair in cats. J.Bone J. Surg., 1967, 49 (A), 4:659-666.

- 84. Michon J, Moberg E. Les lesions traumatiques des nerfs peripheriques. Exp. Scient. Française, Paris, 1973.

- 85. Erhart EA, Ferreira,MC, Marchese At et al. Sutura de nervos com técnica microcirurgica podem evitar total degeneração waleriana. Rev. Ass. Med. Brasil 1975, 21 (7):213-217.

- 86. Hudson AR,Hunter D,Kline D et al Histological studies of experimental interfascicular nerve graft repair. J. Neurosurg, 1979, 51:333.

- 87. Sunderland S. Nerves and nerve injuries. Edinburgh, Churchill, Livingstone, 1980, 2nd. ed.

- 88. Zumiotti A. Estudo sobre a influência da sutura distal em enxertos longos de nervo com emprego de técnica microcirurgica. 1988, Rev. Bras. Ortop. 23 (8):231-234.

- 89. Gonçalves DC. Atualidades em cirurgia dos nervos periféricos. 1978, Rev. Bras. Ortop.,13 (4):191-192.

- 90. Da-Silva CF, Madison R, Dikkes P. et al. An in vivo model to quantify motor and sensory peripheral nerve regeneration using bioresorbable nerve guide tubes. Brain Research-Elsevier Science Publishers, BV, Biomedical Division, 1985, 342:307-315.

- 91. Madison RD,Da-Silva CF,Dikkes P. Entubulation repair with protein additives increases the maximum nerve gaps distance successfully bridged with tubular prostheses. Brain Research-Elsevier Science Publishers, BV Biomedical Division ,1988, 447:325-334.

- 92. Lainetti RD, Da-Silva CF. Local addition of monosialoganglioside GM 1 structurates peripheral axon regeneration in vivo. Brasilian Med. Biol. Res.,1993, 26:841-845.

- 93. Bick EM. Source book of orthopedics. The Williams and Williams Co., 2nd.ed., Baltimore, 1948: front.

Address for correspondence:

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

05 Nov 2008 -

Date of issue

Aug 1997