Abstracts

OBJECTIVE: The role of religious involvement in mental health has been increasingly investigated in psychiatric research; however, there is a shortage of scales on religiousness in Portuguese. The present study aimed to develop and validate a brief instrument to assess intrinsic religiosity (Intrinsic Religiousness Inventory - IRI) in two Brazilian samples. METHOD: The initial version was based on literature review and experts' suggestions. University students (sample 1; n = 323) and psychiatric patients (sample 2; n = 102) completed the Duke Religiosity Index (DUREL), the IRI, an instrument of spirituality measurement (WHOQOL-SRPB), as well as measurements of anxiety and depressive symptoms. RESULTS: The IRI showed adequate internal consistence reliability in sample 1 (Cronbach's α = 0.96; 95% CI; 0.95-0.97) and sample 2 (α = 0.96; 95% CI; 0.95-0.97). The IRI main component analyses indicated a single factor, which explained 73.7% and 74.9% of variance in samples 1 and 2, respectively. Strong correlations between IRI and intrinsic subscale of the DUREL were observed (Spearman's r ranging from 0.87 to 0.73 in samples 1 and 2, respectively, p < 0.001). The IRI showed good test-retest reliability (intraclass correlation coefficients > 0.70). CONCLUSION: These data indicate that the IRI is a valid instrument and may contribute to study intrinsic religiosity in Brazilian samples.

Religion; Validation Study; Instrument; Mental Health

OBJETIVO: O papel da religiosidade em saúde mental vem sendo objeto de intensa investigação. Estudos devem ser executados em diferentes locais e culturas. O presente estudo objetiva desenvolver e validar um instrumento breve para mensurar religiosidade intrínseca (Inventário de Religiosidade Intrínseca - IRI) em duas amostras brasileiras. MÉTODO: A versão inicial foi baseada na revisão de literatura e em sugestões de especialistas. Estudantes universitários (amostra 1; n = 323) e pacientes psiquiátricos (amostra 2; n = 102) preencheram o Índice de Religiosidade de Duke (DUREL), o IRI, uma medida de espiritualidade (WHOQOL-SRPB), bem como medidas de sintomas ansiosos e depressivos. RESULTADOS: O IRI apresentou consistência interna adequada nas amostras 1 (α de Cronbach = 0,96; IC 95%; 0,95-0,97) e 2 (α = 0,96; IC 95%; 0,95-0,97). Análises de componentes principais indicaram um único fator que explicou 73,7% e 74,9% da variância nas amostras 1 e 2, respectivamente. Foram observadas fortes correlações entre o IRI e a subescala de religiosidade intrínseca da DUREL (r de Spearman de 0,87 a 0,73 nas amostras 1 e 2, respectivamente, p < 0,001). O IRI apresentou boa validade teste-reteste (coeficientes de correlação intraclasse > 0,70). CONCLUSÃO: Os dados indicam que o IRI é um instrumento válido e pode contribuir para estudar religiosidade intrínseca em amostras brasileiras.

Religião; Estudo de validação; Instrumento; Saúde mental

BRIEF COMMUNICATION

Development and validation of the Intrinsic Religiousness Inventory (IRI)

Desenvolvimento e validação do Inventário de Religiosidade Intrínseca (IRI)

Tauily C. TaunayI,V; Eva D. CristinoV; Myrela O. MachadoV; Francisco H. RolaII; José W. O. LimaIII; Danielle S. MacêdoII,V; Francisco de Assis A. GondimVI; Alexander Moreira-AlmeidaIV; André F. CarvalhoI,V

IPostgraduate Program in Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC), Fortaleza, Brazil

IIDepartament of Physiology and Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC), Fortaleza, Brazil

IIIDepartament of Public Health, Health Sciences Center, Universidade Estadual do Ceará (UECE), Fortaleza, Brazil

IVCentro de Pesquisa em Religiosidade e Saúde (NUPES), Universidade Federal de Juíz de Fora, Juíz de Fora, Brazil

VPsychiatry Research Group, Department of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universidade Federal do Ceará, Fortaleza, Brazil

VIFaculdade de Medicina Christus, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil

Corresponding authorCorresponding author: André F. Carvalho MD, PhD; Departamento de Medicina Clínica, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade Federal do Ceará Rua Professor Costa Mendes, 1608, 4ºandar 60430-040 Fortaleza, CE, Brazil Phone/Fax: (+55 85) 3261-7227 E-mail: andrefc7@terra.com.br

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE: The role of religious involvement in mental health has been increasingly investigated in psychiatric research; however, there is a shortage of scales on religiousness in Portuguese. The present study aimed to develop and validate a brief instrument to assess intrinsic religiosity (Intrinsic Religiousness Inventory - IRI) in two Brazilian samples.

METHOD: The initial version was based on literature review and experts' suggestions. University students (sample 1; n = 323) and psychiatric patients (sample 2; n = 102) completed the Duke Religiosity Index (DUREL), the IRI, an instrument of spirituality measurement (WHOQOL-SRPB), as well as measurements of anxiety and depressive symptoms.

RESULTS: The IRI showed adequate internal consistence reliability in sample 1 (Cronbach's α = 0.96; 95% CI; 0.95-0.97) and sample 2 (α = 0.96; 95% CI; 0.95-0.97). The IRI main component analyses indicated a single factor, which explained 73.7% and 74.9% of variance in samples 1 and 2, respectively. Strong correlations between IRI and intrinsic subscale of the DUREL were observed (Spearman's r ranging from 0.87 to 0.73 in samples 1 and 2, respectively, p < 0.001). The IRI showed good test-retest reliability (intraclass correlation coefficients > 0.70).

CONCLUSION: These data indicate that the IRI is a valid instrument and may contribute to study intrinsic religiosity in Brazilian samples.

Descriptors: Religion; Validation Study; Instrument; Mental Health.

RESUMO

OBJETIVO: O papel da religiosidade em saúde mental vem sendo objeto de intensa investigação. Estudos devem ser executados em diferentes locais e culturas. O presente estudo objetiva desenvolver e validar um instrumento breve para mensurar religiosidade intrínseca (Inventário de Religiosidade Intrínseca - IRI) em duas amostras brasileiras.

MÉTODO: A versão inicial foi baseada na revisão de literatura e em sugestões de especialistas. Estudantes universitários (amostra 1; n = 323) e pacientes psiquiátricos (amostra 2; n = 102) preencheram o Índice de Religiosidade de Duke (DUREL), o IRI, uma medida de espiritualidade (WHOQOL-SRPB), bem como medidas de sintomas ansiosos e depressivos.

RESULTADOS: O IRI apresentou consistência interna adequada nas amostras 1 (α de Cronbach = 0,96; IC 95%; 0,95-0,97) e 2 (α = 0,96; IC 95%; 0,95-0,97). Análises de componentes principais indicaram um único fator que explicou 73,7% e 74,9% da variância nas amostras 1 e 2, respectivamente. Foram observadas fortes correlações entre o IRI e a subescala de religiosidade intrínseca da DUREL (r de Spearman de 0,87 a 0,73 nas amostras 1 e 2, respectivamente, p < 0,001). O IRI apresentou boa validade teste-reteste (coeficientes de correlação intraclasse > 0,70).

CONCLUSÃO: Os dados indicam que o IRI é um instrumento válido e pode contribuir para estudar religiosidade intrínseca em amostras brasileiras.

Descritores: Religião; Estudo de validação; Instrumento; Saúde mental.

Introduction

The intricate relationship between religiousness and mental health has been increasingly investigated in the last decades. While most studies indicate that religiosity has a protective role in the risk and course of several mental disorders,1 this is not always the case.2

The association between religiousness and mental health differs according to the several dimensions of religiousness.3 One of the best studied dimensions was the Allport and Ross' concept of religious commitment (the influence that religiousness has on decisions and lifestyle of a person). According to the authors, religious orientation may be intrinsic or extrinsic.4 In Extrinsic Orientation, individuals use religion for their own ends as they find religion useful in a variety of ways - to provide security and solace, sociability and distraction, status and self-justification. In Intrinsic Orientation, people find their main motive in religion. Other needs, strong as they may be, are regarded as of less ultimate significance.4 Intrinsic religiosity has consistently emerged as one of the most important dimensions of religiousness in terms of positive influence on physical and mental health outcomes.5,6

In Brazil, a country where 95% of the population have a religion and 84% consider religion as very important,7 there is growing interest in the relationship between religion and mental health.8 However, there is a shortage of religiousness scales in Portuguese. To the best of our knowledge, there is no religiousness scale in Portuguese validated on clinical psychiatric samples. The Duke Religious Index (DUREL),5 a brief and largely used worldwide scale, has been translated to Portuguese and validated in non-clinical samples.9 Furthermore, there is a lack of validation studies performed on clinical psychiatric samples.

The present study represents a collaborative effort to develop a brief measure of intrinsic religiosity, namely the Intrinsic Religiousness Inventory (IRI). Additionally, the psychometric properties of this new instrument were determined in two different samples (e.g., university students and psychiatric outpatients).

Method

Development of the IRI

Following assessment of relevant scientific literature regarding intrinsic religiosity (reference available upon request) in order to capture facets of this construct/dimension, three authors (TCT, FHR, and FAG) performed a qualitative study with a purposive sample of 29 individuals (university students and hospital personnel). Briefly, we used focus groups with 4-5 individuals. Interviews were semi-structured using prompts (such as 'What is the ultimate meaning of religion?'; 'How does religion give a purpose for your existence?) to maintain a focus. Interviews were audio-taped, transcribed and analyzed thematically. The transcripts were read several times by each senior author who independently developed themes that they considered relevant. A sociologist (Alexandre F. C. Vale, PhD) and an anthropologist (Antônio M. Cavalcante, PhD) with research focuses on religion participated in group discussions that led to the development of a draft version of the IRI with 14 items. This was a Likert-type scale in which each statement was followed by five possible responses. The criteria for removing items were as follows: (i) insufficient spread of responses: any statements for which 80% or more participants gave two adjacent answers; (ii) statements indicated by participants as ambiguous or unclear; (iii) statements that did not contribute to the factor structure or the overall variance explained. A final 10-item instrument was thus obtained and studied (see AppendixAppendix).

Samples

Two different samples participated in this investigation. Sample 1 was composed of undergraduate university students from the Psychology course and the Medical School of the Universidade Federal do Ceará. A total of 345 students (145 psychology students and 200 medical students) were consecutively approached prior to the beginning of regular classes and allowed to participate.

A consecutive sample of 113 patients (recruited from November 2010 to March 2011) attended at the general psychiatric outpatient clinic of the Hospital Universitário Walter Cantídio (HUWC) was also studied (Sample 2). This psychiatric service receives patients with heterogeneous psychiatric diagnosis through referrals from primary care services and from other clinics of the HUWC. This recruitment site was selected in order to avoid oversampling of patients with a particular diagnosis. This sample included any adult psychiatric patient regardless of gender and age. Exclusion criteria included: (i) refusal to participate; (ii) cognitive deficits (e.g., mental retardation and dementia) that could impair comprehension; and (iii) severely agitated or frankly psychotic patients.

Instruments and procedures

Following socio-demographic data collection, university students completed the IRI, DUREL,9 Beck depression inventory (BDI),10 Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI),11 and WHOQOL spirituality, religiousness and personal beliefs module (WHOQOLSRPB).12 The WHOQOL-SRPB is composed of 32 questions covering 8 spirituality facets.12 The general-SRPB domain scores were considered the primary spirituality measure throughout this research.

Sample 2 answered the IRI, DUREL, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),13 WHOQOL-SRPB, and a structured socio-demographic questionnaire. The HADS was selected because we considered the fact that patients with severe mental disorders (e.g., bipolar disorder, schizophrenia) have a higher frequency of medical comorbidities. The HADS reliably measures psychological distress symptoms in such samples, as this instrument does not emphasize somatic/vegetative symptoms.13 A senior research psychologist (TCT) determined the primary psychiatric diagnosis of each patient by means of the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID).

To determine the test-retest reliability of the IRI, research participants underwent a second face-to-face interview (one month after the initial interview). The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committees of the HUWC (process number 023.04.09) and the Department of Physiology and Pharmacology of the UFC (process number 085.08). A signed informed consent was obtained for each subject before inclusion in this investigation.

Statistical analyses

Data are reported as means ± SEM (Standard Error of the Mean). We used principal component analysis with orthogonal (Varimax) rotation to determine the factorial structure of the IRI. The factors were selected according to eigenvalues > 1 and scree plot inspection. For internal consistency reliability, the Cronbach's alpha coefficient value (with 95% CI) for the IRI was determined. Correlations between IRI and DUREL (intrinsic, organizational and non-organizational subscales) were determined (criterion validity). Relationships with the IRI, WHOQOL-SRPB, and anxiety/depressive symptoms were also calculated. Test-retest reliability was determined with intra-class correlation coefficients. Significant level was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed; null hypothesis: r = 0 and alternative hypothesis: r  0). Correlations were considered strong whenever r > 0.8. Statistical analyses were carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16.0 for Windows.

0). Correlations were considered strong whenever r > 0.8. Statistical analyses were carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16.0 for Windows.

Results

Description of the samples

Sample 1 was composed of 323 university students (135 psychology students and 188 medical students). Twenty-two students refused to participate in this study (response rate = 93.6%). Students were 20.6 ± 2.9 years old (111 male; 212 female), with the following distribution by religious orientation: 60% (n = 194) Catholics, 12% (n = 39) Protestants, 8% (n = 26) without religious affiliation, 8% (n = 26) atheists and agnostics, 3% (n = 10) Spiritualists , 2% (n = 6) Gnostics, and 7% (n = 25) lacked information. Twelve (4%) students had a part-time job. Gross monthly family income was US$ 3,400 ± 838.

In sample 2, five patients refused to participate in the study and 6 patients were excluded due to mental retardation (n = 2) and acute psychotic episodes (n = 4). The final sample (response rate = 90.2 %) consisted of 102 patients (70 female) with mean age of 41.3 ± 14.8 years. The distribution according to religious affiliation was: 59% (n = 60) Catholic, 12% (n = 12) Protestants, 8% (n = 8) Spiritualists, and 21% (n = 22) without religious affiliation. Regarding marital status, 32% (n = 33) were married, 9% (n = 9) widowed, 14% (n = 14) divorced, and 45% (n = 46) single. Regarding educational level, 38% (n = 38) completed primary school and 63 (62%) completed or were attending high school. As for employment status, 41% (n = 42) of the sample was working full time, whereas 30% (n = 31) were unemployed. Patients received the following DSM-IV primary diagnosis: bipolar disorder (29.4%; n = 30), major depression (8.8%; n = 9), substance-related disorders (18.6%; n = 19), schizophrenia (27.4%; n = 28), obsessive-compulsive disorder (8.8%; n = 9), and other disorders (6.8%; n = 7). Gross monthly family income was US$ 388 ± 109.

Principal component analysis

In both samples, a single factor solution for the IRI was obtained. Such factor explained 73.7% and 74.9% of the rotated variances in samples 1 and 2, respectively. Factor loadings of each item of the scale varied from 0.74 to 0.90 in sample 1 and from 0.58 to 0.95 in sample 2, thereby indicating that each statement contributed significantly to the underlying factor.

Internal consistency reliability

Corrected item-total correlations of the IRI varied from 0.70 (item 9) to 0.88 (item 5) in sample 1, and from 0.53 (item 9) to 0.91 (item 1) in sample 2 (additional data available upon request). Cronbach´s alpha coefficients pointed to strong internal consistency reliabilities in samples 1 (α = 0.96; 95% CI; 0.95-0.97) and 2 (α = 0.96; 95% CI; 0.95-0.97).

Criterion validity

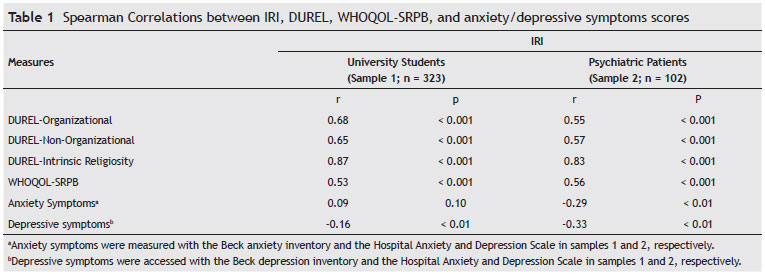

As expected, these data indicate that the IRI has adequate criterion validity. The strength and orientation of associations between measures cited above as determined through Spearman rank Correlation Coefficient were described in Table 1.

Test-retest reliability

The IRI had adequate test-retest reliability. 10 students and 6 patients were lost to follow-up and were not included in these analyses. For total scores intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) were 0.92 (p < 0.001) and 0.89 (p < 0.001) for samples 1 and 2, respectively. ICC for individual items ranged from 0.74 to 0.95 in sample 1 and from 0.71 to 0.92 in sample 2 (all p < 0.01).

Discussion

The present work developed and validated a new instrument to measure intrinsic religiosity in both psychiatric and non-clinical Brazilian populations. In fact, the present paper demonstrates that the IRI had adequate internal consistency, criterion, and test-retest reliabilities. Furthermore, a single factor solution, namely intrinsic religiosity, was obtained for the IRI.

The IRI has a strong correlation with the intrinsic sub-scale of the DUREL. Furthermore, in agreement to previous research, moderate correlations were observed between the IRI and other religious dimensions accessed by the DUREL.9 The relationship between religion and spirituality as research constructs has been a matter of debate.1,14 Furthermore, operative definitions of spirituality and religiousness are imprecise and consensus regarding these definitions remains elusive.15 Despite these considerations, our data suggest that spirituality and intrinsic religiosity are overlapping but distinct concepts. A tentative explanation for this finding relies on the fact that intrinsic religiosity may correlate with certain dimensions of spirituality. For example, Nelson et al. demonstrated that the faith dimension of spirituality has a strong correlation with intrinsic religiosity among prostate cancer patients.16

A small correlation between depression and intrinsic religiosity was observed in both samples. This finding relates to a meta-analysis of 147 studies that demonstrated an inverse correlation between religious involvement and depression (-0.10), which increased to -0.15 in stressed populations.17

This investigation has some limitations. First, our sample was composed of young students. The psychometric properties of the IRI should be determined in general population samples considering different age groups and educational levels. Second, our heterogeneous clinical sample was drawn from a tertiary center. It is worthwhile to investigate the psychometric properties of the IRI in mental health center communities with the inclusion of less severe cases. Third, the instrument was validated in a Brazilian sample with a Catholic and Protestant majority. More international studies are needed to verify its psychometric properties in different cultural and religious backgrounds.

In conclusion, the IRI is a brief, simple, and valid instrument for intrinsic religiousness measurement and it might significantly contribute to study the impact of religion on physical and mental health in Brazilian samples. It is plausible that the simultaneous application of related instruments might shed some light on some controversies of this field of scientific inquiry.

Received on April 29, 2011; accepted on September 24, 2011

Appendix - Clique para Ampliar

Appendix - Clique para Ampliar

Appendix - Clique para Ampliar Appendix - Clique para Ampliar

Appendix - Click to enlarge

Appendix - Click to enlarge

Appendix - Click to enlarge Appendix - Click to enlarge

- 1. Koenig HG. Research on religion, spirituality, and mental health: a review. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(5):283-91.

- 2. Siddle R, Haddock G, Tarrier N, Faragher EB. Religious delusions in patients admitted to hospital with schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2002;37(3):130-8.

- 3. Hackney CH, Sanders GS. Religiosity and mental health: a metaanalysis of recent studies. J Sci Stud Relig. 2003;42(1):43-55.

- 4. Allport GW, Ross JM. Personal religious orientation and prejudice. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1967;5(4):432-43.

- 5. Koenig H, Parkerson GR, Jr., Meador KG. Religion index for psychiatric research. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(6):885-6.

- 6. Pirutinsky S, Rosmarin DH, Holt CL, Feldman RH, Caplan LS, Midlarsky E, Pargament KI. Does social support mediate the moderating effect of intrinsic religiosity on the relationship between physical health and depressive symptoms among Jews? J Behav Med. 2011; [Epub ahead of print]

- 7. Moreira-Almeida A, Neto FL, Koenig HG. Religiousness and mental health: a review. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2006;28(3):242-50.

- 8. Floriano PJ, Dalgalarrondo P. Mental health, quality of life and religion in an eldery sample of the Family Health Program. J Bras Psiquiatr. 2007;56(3):162-70

- 9. Lucchetti G, Granero-Lucchetti AL, Peres MF, Leao FC, Moreira-Almeida A, Koenig HG. Validation of the Duke Religion Index: DUREL (Portuguese Version). J Relig Health. 2010; [Epub ahead of print]

- 10. Gorenstein C, Andrade L. Validation of a Portuguese version of the Beck Depression Inventory and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory in Brazilian subjects. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1996;29(4):453-7.

- 11. Steer RA, Kumar G, Ranieri WF, Beck AT. Use of the Beck Anxiety Inventory with adolescent psychiatric outpatients. Psychol Rep. 1995;76(2):459-65.

- 12. Panzini RG, Maganha C, da Rocha NS, Bandeira DR, Fleck MP. Brazilian validation of the Quality of Life Instrument/ spirituality, religion and personal beliefs. Rev Saude Publica. 2011;45(1):153-65.

- 13. Botega NJ, Bio MR, Zomignani MA, Garcia C, Jr., Pereira WA. Mood disorders among inpatients in ambulatory and validation of the anxiety and depression scale HAD. Rev Saude Publica. 1995;29(5):355-63.

- 14. Moreira-Almeida A, Koenig HG. Retaining the meaning of the words religiousness and spirituality: a commentary on the WHOQOL SRPB group's "a cross-cultural study of spirituality, religion, and personal beliefs as components of quality of life" (62: 6, 2005, 1486-1497). Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(4):843-5.

- 15. Hall DE, Meador KG, Koenig HG. Measuring Religiousness in Health Research: Review and Critique. J Relig Health. 2008;47(2):134-63.

- 16. Nelson C, Jacobson CM, Weinberger MI, Bhaskaran V, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, Roth AJ. The role of spirituality in the relationship between religiosity and depression in prostate cancer patients. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38(2):105-14.

- 17. Smith TB, McCullough ME, Poll J. Religiousness and depression: evidence for a main effect and the moderating influence of stressful life events. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(4):614-36.

Appendix

Appendix - Clique para Ampliar

Appendix - Click to enlarge

Corresponding author:

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

18 June 2012 -

Date of issue

Mar 2012

History

-

Received

29 Apr 2011 -

Accepted

24 Sept 2011