Abstracts

INTRODUCTION: Child/adolescent mental health (CAMH) problems are associated with high burden and high costs across the patient's lifetime. Addressing mental health needs early on can be cost effective and improve the future quality of life. OBJECTIVE/METHODS: Analyzing most relevant papers databases and policies, this paper discusses how to best address current gaps in CAMH services and presents strategies for improving access to quality care using existing resources. RESULTS: The data suggest a notable scarcity of health services and providers to treat CAMH problems. Specialized services such as CAPSi (from Portuguese: Psychosocial Community Care Center for Children and Adolescents) are designed to assist severe cases; however, such services are insufficient in number and are unequally distributed. The majority of the population already has good access to primary care and further planning would allow them to become better equipped to address CAMH problems. Psychiatrists are scarce in the public health system, while psychologists and pediatricians are more available; but, additional specialized training in CAMH is recommended to optimize capabilities. Financial and career development incentives could be important drivers to motivate employment-seeking in the public health system. CONCLUSIONS: Although a long-term, comprehensive strategy addressing barriers to quality CAMH care is still necessary, implementation of these strategies could make.

Child, Adolescent, Mental Health, Community Mental Health Services; Primary Health Care

INTRODUÇÃO: Problemas de saúde mental na infância/adolescência (SMIA) trazem diversos prejuízos e geram altos custos. A assistência precoce pode ser custo efetiva, levando a melhor qualidade de vida a longo prazo. OBJETIVOS/MÉTODO: Analisando os artigos mais relevantes, documentos do governo, base de dados e a política nacional, este artigo discute como melhor administrar a atual falta de serviços na área da SMIA e propõe estratégias para maximizar os serviços já existentes. RESULTADOS: Dados apontam evidente falta de serviços e de profissionais para tratar dos problemas de SMIA. Serviços especializados, como o CAPSi (Centro de Atenção Psicossocial Infanto-Juvenil) estão estruturados para assistir casos severos, mas são insuficientes e desigualmente distribuídos. A maioria da população já tem bom acesso às unidades básicas de saúde e um melhor planejamento ajudaria a prepará-las para melhor assistir indivíduos com problemas de SMIA. Psiquiatras são escassos no sistema público, enquanto psicólogos e pediatras estão mais disponíveis; para estes recomenda-se capacitação mais especializada em SMIA. Incentivos financeiros e de carreira motivariam profissionais a procurarem emprego no sistema público de saúde. CONCLUSÕES: Apesar de estratégias complexas e de longo prazo serem necessárias para lidar com as atuais barreiras no campo da SMIA, a implantação de certas propostas simples já poderiam trazer impacto imediato e positivo neste cenário.

Criança, Adolescente; Saúde Mental, Serviços Comunitários de Saúde Mental; Atenção Primária à Saúde

SPECIAL ARTICLE

How to improve the mental health care of children and adolescents in Brazil: actions needed in the public sector

Cristiane S. PaulaI,IV; Edith Lauridsen-RibeiroII; Lawrence WissowIII; Isabel A. S. BordinIV; Sara Evans-LackoI

IUniversidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Distúrbios do Desenvolvimento, Brazil

IISão Paulo City Hall, Health City Secretariat, São Palo, Brazil

IIIJohns Hopkins University, School of Public Health, Baltimore, USA

IVDepartamento de Psiquiatria, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Brazil

VKing's College London, Institute of Psychiatry, Health Service and Population Research, England

Corresponding author Corresponding author: Cristiane Silvestre de Paula Universidade P Mackenzie Rua da consolação, 930. Prédio nº 38 São Paulo, SP, Brazil. CEP- 01302-000 E-mail: csilvestrep09@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: Child/adolescent mental health (CAMH) problems are associated with high burden and high costs across the patient's lifetime. Addressing mental health needs early on can be cost effective and improve the future quality of life.

OBJECTIVE/METHODS: Analyzing most relevant papers databases and policies, this paper discusses how to best address current gaps in CAMH services and presents strategies for improving access to quality care using existing resources.

RESULTS: The data suggest a notable scarcity of health services and providers to treat CAMH problems. Specialized services such as CAPSi (from Portuguese: Psychosocial Community Care Center for Children and Adolescents) are designed to assist severe cases; however, such services are insufficient in number and are unequally distributed. The majority of the population already has good access to primary care and further planning would allow them to become better equipped to address CAMH problems. Psychiatrists are scarce in the public health system, while psychologists and pediatricians are more available; but, additional specialized training in CAMH is recommended to optimize capabilities. Financial and career development incentives could be important drivers to motivate employment-seeking in the public health system.

CONCLUSIONS: Although a long-term, comprehensive strategy addressing barriers to quality CAMH care is still necessary, implementation of these strategies could make.

Descriptors: Child, Adolescent, Mental Health, Community Mental Health Services; Primary Health Care.

Introduction

Child mental health problems are relatively common, associated with high levels of burden and high costs over a lifetime.1,2 Addressing child mental health needs early on, however, can be cost effective and lead to improved quality of life for individuals later on. Despite the significant implications of untreated mental illness during childhood and adolescence, and potential benefits gained from early treatment and preventive programs, government spending on child mental health care is insufficient, especially in low and middle-income countries. In these countries, government spending on child mental health care is disproportionately smaller in comparison with investments in mental health care for older age groups and spending on physical health for all age groups.3,4

Overall, approximately 7% to 12% of Brazilian children and adolescents have mental health problems that require some form of mental health care.5-8 Estimates based on international studies suggest that approximately half of these problems can be considered severe.9 For many of these individuals, private care (not funded by the Brazilian government) is extremely expensive and inaccessible, and the possibility of finding appropriate mental health care in the public system is remote. These difficulties are compounded by a geographic maldistribution of services as well. In most Latin American countries, highly specialized services exist mainly in the private sector and are concentrated in large cities.10

In 2011, the Grand Challenges in Global Mental Health Initiative (GCGMHI) emphasized the main priorities for mental health research for the next 10 years. Its main goal was to identify barriers that, if removed, would help to solve or reduce important mental health problems. This initiative involved more than four hundred researchers, advocates, program coordinators and clinicians from 60 countries. The panel members generated a list of the top 25 grand challenges, which can be summarized as follows: (1) Research should take a life-course approach because many mental health problems begin and/or manifest in childhood; (2) Major changes in the health system are critical, and social exclusion and discrimination must be considered. Furthermore, new models should integrate mental health care with care for chronic disease, should be more community-based and should include assistance for family members in addition to the patients themselves; (3) All care and treatment interventions should be evidence-based; and (4) More attention should be given to the relationships between environmental exposure and mental health problems.11 It is important to note that, among the top five priorities, was the improvement of children's access to evidence-based care by trained health providers in low and middle-income countries.

This paper builds on the GCGMHI framework to examine, for the Brazilian public sector mental health system: (1) the capacity of different service settings to assist children and adolescents in need of mental health care; (2) the current roles of services and healthcare practitioners regarding child mental health; (3) the main barriers to accessing high-quality child mental health care; and (4) suggest actions that could be taken by the public health system to improve mental health care for disadvantaged Brazilian children and adolescents.

Methods

We performed a comprehensive search of Medline and the main Brazilian scientific databases, Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO) and LILACS. Scielo is an electronic database developed specifically for low-and middle-income countries. It originated in Brazil and was funded by the Brazilian government in partnership with the Latin American and Caribbean Center for Health Sciences Information. LILACS is the most extensive index of scientific literature covering countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. To identify scientific papers relevant to child and adolescent mental health services in Brazil, we used such search terms as 'Mental Health', Mental Health Service, Unified Health System, Public Health, Health Policy, Health Personnel, CAPSI, Primary Health Care and Child and Adolescent. We included papers in Portuguese, English and Spanish, also searching the reference lists of the key Brazilian papers and incorporating additional relevant references into our paper.

In addition to published scientific literature, we searched grey literature, including the following sources: book chapters, national and regional documents, administrative databases and other policy documents related to mental health. Finally, we consulted public officials and health practitioners working in the mental health field in reference to unpublished documents.

Results and Discussion

The Brazilian Public Health System

In Brazil, the Unified National Health System (SUS from the Portuguese) provides universal access to health services for the entire Brazilian population. This system is organized regionally, is composed of clinics that integrate primary and specialty care, and is financed and coordinated by various government agencies. The SUS is mainly financed by federal funds (approximately US$ 15 billion in 2005), while state and municipal governments are obligated by law to spend 12% to 15% of their respective budgets on health care.12

Although the Brazilian mental health system is fully integrated with SUS,12,13 unequal distribution of resources among different regions of Brazil (both financial and human resources) and high levels of individual income inequality make access to care a significant challenge for many children and adolescents with mental health problems.14

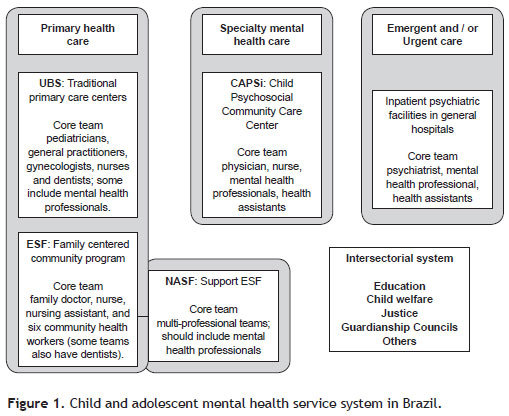

The current mental health policy for children and adolescents underscores the importance of an intersector system that coordinates care among the health education, child welfare and justice sectors.15 An additional unique feature of the system is the Guardianship Council. These Councils were created to protect the rights of children/adolescents and are mandated by the Brazilian Child and Adolescent Rights Act (Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente/ECA).16 The main function of the Councils is to ensure that children who are in need or at risk receive the best possible support; they respond to a wide range of situations, such as child abuse, school drop-out, legal issues. and inadequate health care. The councils do not provide services, but they mediate between the community and the local intersector system, ensuring the rights of children and adolescents.17

According to current Brazilian public policy, some services are considered strategic for the identification and treatment of of children and adolescents with mental health problems. These services are primarily the Psychosocial Community Care Center for Children and Adolescents (Centro de Atenção Psicossocial Infanto-Juvenil/CAPSi) and the primary care health units.15 For crisis situations, there are also emergency services and inpatient services in general hospitals.

Child Mental Health Services

(1) Psychosocial Community Care Center for Children and Adolescents (CAPSi)

The Psychosocial Community Care Center (CAPS) units are day treatment facilities staffed by multidisciplinary teams. There are 5 types of CAPS services: 3 for adults (CAPS I, CAPS II and CAPS III) which are categorized according to the size of the population they serve and their hours of availability; one for substance abuse (CAPS-AD); and one for children and adolescents (CAPSi). Established in 2002, they are relatively new. Overall, CAPS plays a strategic role in the coordination of mental health care (facilitating the integration of health care, education and social welfare services) at the regional level.18

CAPSi is the main source of healthcare for individuals younger than 24 years with severe and persistent mental illness and/or with a high level of impairment. Each CAPSi is expected to assist approximately 155 cases per month.19 The team consists of one physician (i.e., a psychiatrist, neurologist or pediatrician with a specialization in mental health), one nurse, four mental health professionals (i.e., psychologist, occupational therapist, social work, nurse, speech therapist, etc.) and five health assistants.

Given the prevalence of severe mental health problems among children and adolescents, the number of CAPSi units currently available is insufficient to support the Brazilian population in need. In February 2011, there were only 136 accredited CAPSi units in the whole country, and each was expected to treat a maximum of 155 cases at any given time.18 Furthermore, units are unequally geographically distributed among Brazil's regions. They are mostly concentrated in the southeast and northeast of Brazil, while several states, particularly those in the Northern region, do not have any established unit.20 Despite a recommended distribution of one unit for every 200,000 inhabitants, in July 2011, there was only one CAPSi for every 1.3 million people in the Southeast region and one CAPSi for every 5 million people in the Northern region.20 São Paulo is the most populous state in Brazil (including 20% of the Brazilian population) and has the highest GDP in Brazil. Although it includes 30 CAPSi units, the largest number in the country,21 the number is still insufficient. In the case of Pervasive Developmental Disorders (PDD), a recent Brazilian study estimated the prevalence rate to be 0.3%.22 If there are approximately 12 million children and adolescents younger than 20 years of age living in São Paulo State, it is reasonable to expect the existence of almost 40,000 cases of PDD there. When considering that each CAPSi unit assists 155 cases, 258 units would be necessary to care for all children/adolescents with PDD alone in São Paulo State.

Although CAPSi units are designed to focus on children and adolescents with highly severe mental health problems few data are available describing the populations that they actually serve. We are aware of only one paper published on this topic describing, in 2003, data from seven CAPSi units from different regions of the country. It shows that a significant proportion of children and adolescents (44.5%) receiving treatment at CAPSi had a diagnosis of potentially less severe behavioral or emotional disorders (ICD-10: F90-F98), represented only 19.4% of the total. The authors concluded that these results suggest that CAPSi did not focus care on the most severe cases.23 In 2011, we analyzed data from all 30 accredited CAPSi units in São Paulo State.21 Our findings revealed a different pattern compared to the previous investigation23 the main diagnoses among the current clientele are: PDD (ICD-10: F84, F88, F89) (28.8%); Hyperkinetic Disorders (ICD-10: F90) (14.7%), and Mood [affective] Disorders (ICD-1-: F30-F39) (11.4%). These findings are almost identical to the percentages observed in all nine accredited CAPSi in São Paulo City (nine out of 17 existing units are accredited units).21 These data suggest that currently, at least in São Paulo State, the majority of cases cared for in CAPSi units seem to be the severe ones. It is important to mention that the diagnosis itself is not the only way to evaluate severity, but can be considered a proxy of severity.

Because CAPSi focuses on the individuals with the most complex needs, there is a gap in services for children and adolescents with less severe and more common mental illnesses (approximately 90% of cases). Because CAPSi was not designed to serve the entire population of children and adolescents with mental disorders, changes in its structure to accommodate the entire range of emotional and behavioral problems would require a significant and sustained investment. Additionally, changing the focus of CAPSi to treat more common mental health problems could divert resources from individuals with the highest level of need and favor the maintenance of its unequal distribution as services would be concentrated in existing geographic locations (i.e., they would continue to be unequally distributed). Whereas wealthier sites may have the capacity to see a greater range of severities the less wealthy sites would become even more overburdened.

Given that the number of existing CAPSi units is insufficient and that the units are not designed to treat all cases alternatives are necessary to reduce the burden of disease among children and adolescents with mental health problems. Existing services, particularly primary care units, are potential alternative resources which could contribute to child and adolescent mental health care.

(2) Primary Care System

Primary care units are the most accessible type of health service in Brazil. Their costs are relatively low, they reach a large proportion of the population and they are already utilized by many children and adolescents for other types of health problems and preventive care.24,13 Addressing mental health needs through a general health service, not primarily associated with mental illness could be advantageous, it is likely to be associated with lower levels of stigma, and, therefore, facilitate higher rates of engagement with families for preventing, initiating and maintaining mental health treatments. In primary care units, regular visits and/ or check-ups are emphasized during some or all of childhood and continuity of care (multiple return visits to the same site over a fairly short period of time) can facilitate a sense of comfort and trust with clinic personnel.13

Before 1994, the health system was composed of "traditional" primary care centers (Unidade Básica de Saúde - UBS) staffed by teams made up of pediatricians, general practitioners, gynecologists, nurses and dentists; some of them also have mental health. In the 1990s, the Ministry of Health launched the Family Health Program (Programa de Saúde Família) to replace the traditional medical model of care delivery with one that was more family centered and responsive to the health needs of a community. Recently the Family Health Program was renamed the Family Health Strategy (Estratégia de Saúde da Família -ESF). It cares for approximately 53.1% of the entire Brazilian population, and an even higher proportion in the northeast, the poorest Brazilian region. The ESF's typical team consists of one family doctor, one nurse, one nursing assistant, and six community health workers (some teams also have dentists). Each team is assigned one thousand families living in a specific geographic area (community), including children, adolescents, adults and the elderly.20

(3) Family Health Core (Núcleo de Apoio à Saúde da Família)

In 2008, the Family Health Core (Núcleo de Apoio à Saúde da Família -NASF) was launched. This strategy was developed to support the ESF by helping to broaden the scope of primary care and increase its capacity to solve problems.

NASF is comprised of multiprofessional teams and policy recommends that mental health professionals are included in each team.25 NASF works in partnership with the ESF teams, sharing responsibilities and supporting the health practices of patients under their responsibility; each NASF supports 8 to 20 ESF teams. Through case discussions, exchange of experiences and shared assistance, it is expected that professionals from the ESF will increase their knowledge and capacity for dealing with mental health problems in their clientele.26 Thus, the primary mission of NASF in regards to mental health is to share experiences and to train health professionals from ESF teams to treat less severe cases (90%) and correctly refer the most severe cases to CAPSi, when it is available in the region.

Healthcare Practitioners

Overall, there is a paucity of mental health providers in low- and middle-income countries. A recent study that included data from 58 low- and middle-income countries showed that 67% had a shortage of psychiatrists and 79% had a shortage of psychologists, occupational therapists and social workers.27 Data pertaining to healthcare practitioners within the Brazilian context, is summarized as follow.

(1) General Psychiatrists and Child Psychiatrists

Psychiatrists are one of the least accessible professionals in the Brazilian public health system (n = 6,003) and are scarce throughout the geographical region.28 Nationally, there is only one psychiatrist per 75 primary care units.21 The scenario is even worse for child and adolescent psychiatrists, as there are only approximately 300 in the entire country.29-30 Given the lack of child and adolescent psychiatrists in Brazil, alternatives involving the optimization of existing human resources and the development of supplementary training programs are essential to improve the country's child and adolescent mental health care capacity.

(2) Psychologists

According to the World Health Organization, psychologists are scarce in low- and middle-income countries. In Brazil, however, psychologists represent a significant existing human resource (31.8 per 100,000) compared with other uppermiddle-income countries in South America (e.g., Chile 15.7 per 100,000; Uruguay: 15.1 per 100,000), and the number of psychologists in Brazil is substantially higher than the median number of psychologists in upper middle income countries (1.8 per 100,000).31,32 Although Brazil has a high number of psychologists, almost 70% of them work outside of the public health system.21 In the public primary care system, approximately one of every seven primary care units includes a psychologist; but, the distribution is extremely unequal around the country.21

Brazilian academic training in psychology is often broad and does not emphasize skills applicable to public health or child mental health care. This training is designed to be broad to allow psychologists to study and work in a variety of areas (e.g. clinical psychology, educational psychology and research.20,33 However, bachelor's level university training does not fully prepare a psychologist to develop an area of expertise, and it includes little material specific to child mental health. Thus, many psychologists seek additional training after graduation to become an effective practitioner. In addition, some argue that psychology training in Brazil is geared toward preparing professionals to assist patients in private clinics, mainly using individual long-term psychotherapy,34 while training is lacking regarding briefer, more cost-effective, evidence-based treatments for mental health problems, more appropriate for the context of public clinics. Therefore, specific clinical training, particularly adapted to the public health system is recommended, such as, briefer individual psychotherapy, group psychotherapy, psychoeducational models, parenting training, etc.

Although most psychologists working in the public health system do not have adequate bachelor's level training to address child mental health problems, their broad mental health training base could be easily upgraded. Thus, with additional brief training, a large number of existing Psychology graduates could potentially be immediately incorporated into the public sector and quickly increase the availability of well-prepared human resources for child and adolescent mental health. Moreover, psychologists could collaborate more closely with the smaller number of existing psychiatrists. In Brazil, there are 31.8 psychologists per 100,000 people, compared to 4.8 psychiatrists per 100,000 people,32 broaden the scope of assistance in child and adolescent mental health. Because physicians are the only professionals responsible for providing medication, multidisciplinary collaboration is needed to provide effective mental health care as recommended by the Brazilian Ministry of Health.18,35 Nevertheless, as psychologists are offered more money to work in private clinics, additional financial or career development incentives would be important drivers to motivate employment-seeking in the public health system.30

Despite the potential for increasing the supply and knowledge of psychologists, it is unlikely that sufficient numbers will ever be available to meet children's mental health care needs. Thus, other medical professionals who provide care for children and adolescents will likely need to develop skills for recognizing and treating mental health problems either alone or via consultation or collaboration with specialists. Pediatricians, nurses, community health workers and other health professionals are potential candidates for such training and their potential contribution is discussed below.

(3) Pediatricians

Pediatricians in Brazil are almost as available as psychologists are in the public system. There are approximately 16,100 pediatricians working in the SUS (8.42 per 100,000 inhabitants) and 25% of them work in primary care.21 Pediatricians can also play an important role in mental health care, as they are often the first point of contact for children. and because much of pediatric care consists of general health monitoring, preventive care and health promotion, providing opportunities for discussion of issues surrounding parent-child interaction and child behavior.36

Although their time for consultation is limited, pediatricians are already specialized in child development and, thus, additional training may allow them to more efficiently identify, assistant and refer children and adolescents with mental health problems.37,38 On the other hand it is known that pediatricians have many competing demands and may be reluctant to treat mental health problems for several reasons, including a lack of confidence in their skills related to mental health, discomfort when discussing mental health issues and lack a of trust in the referral structure.38,39 Thus, further training of pediatricians to improve recognition, treatment and follow-up of less severe cases and capacity to make adequate referrals of more severe cases should be considered to minimize these issues and provide better care for children and adolescents.

(4) Nurses, Community Health Workers and other Professionals

Finally, nurses, community health workers and professionals from the Family Health Strategy and from the educational system could also be potential mental health providers, mainly identifying and, on some level, managing children/ adolescents with less severe mental health problems. Currently in Brazil, the majority of these professionals lack mental health training; therefore, substantial investment would be needed to prepare them to be effective mental health care providers.40

Actions needed

First, because child mental health care should be provided by multidisciplinary teams, the optimization of existing human resources from the public sector is essential for improving child and adolescent mental health care capacity. Several authors argue that an intersector system, particularly involving general health and education stakeholders, would improve the effectiveness of mental health services.41,42 Such a system would both provide the widest possible range of care for children's problems, but also create consultation networks so that scarce and highly-trained mental health professionals can be used efficiently to support the work of professionals with less specialized training. This type of system is recommended, but successful coordination depends on the clear articulation, specification and acceptance of responsibilities for those involved.15

Second, to meet the enormous existing service demands, it is vital to offer specialized training to psychologists who are already working in the public health system and to increase the number of public sector positions for trained psychologists and child psychiatrists. Recruiting more well-trained psychology graduates to work in primary care services would increase the number of child mental health specialists available in the public sector. Trained pediatricians could also be an important resource for treating less severe cases and making appropriate referrals for more severe ones.

Third, further training for nurses, community health workers, professionals from the Family Health Strategy and educators to improve the early identification and follow-up of children and adolescents with mental health problems presents an additional alternative that deserves appropriate investment. It would probably be more costly than the alternative mentioned above, since they generally don't have previous training in child development or child mental health; however, the investment could pay off given these professionals are often already the first point of contact for children.

Finally, changes in the psychology curriculum that emphasize evidence-based treatments for mental health problems (e.g.,briefer, psychoeducational models, parenting training, and cost-effectiveness) are needed to build future psychologists' capacity to adequately address child mental health problems in the public health system.

Additionally, higher salaries and career development opportunities in the public sector would provide important incentives.30 The same types of incentives should be considered for positions in less-developed regions of Brazil, given that the majority of professionals prefer to live and work in bigger cities, which offer higher salaries and better work infra-structure. Overall, financial incentives and additional training could benefit the public system and encourage more psychologists and psychiatrists to work in the public system,30 particularly in less developed areas of the country.

Conclusions and Recommendations

High-quality mental health provision and good access to it are essential for improving the mental health of children and adolescents with emotional and behavioral disorders. Therefore, public policy changes and new actions are mandatory to reducing the burden of disease and addressing the needs of this population. Realistic options, however, are required to be low cost both financially and in terms of infra-structure, training and human resources. For that reason, existing services, particularly primary care units, can be considered as potential alternative resources to address less severe child and adolescent mental health problems, while CAPSi would provide care for young people with more severe and disabling impairments. With good referral mechanisms between services, children initially identified in the general health sector who are found to need more intensive services can be moved up, and children who are initially seen through CAPSi can be monitored in the general sector once their conditions improve.

The number of CAPSi services has increased dramatically in Brazil, from 32 centers at the program's inception in 2002 to 136 centers in 2011.18 Considering the prevalence of mental health problems, however, the rate of increase still does not meet the present needs of the population. Around the world, the lack of government policy and inadequate funding to scaling up services development. This is especially apparent in the case of mental health services for young people.43 The false perception that this age group is 'healthy' is an additional barrier for improving services. This is a global public health problem; recent evidence suggests that the adolescent age group has been severely neglected, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, where mental disorders represent the leading burden of disease among 10- to 24-year-olds, as measured by the DALYs.44 Particularly in Brazil, only 8% of all CAPS are dedicated for young people. Thus, there is a need to increase attention toward the health needs of adolescents and act on the opportunities for advocacy and prevention.

An extra challenge in the Brazilian SUS is that data are not available regarding types of treatments provided within CAPSi services. Thus, it would be important to emphasize evaluation and implementation of evidence based practice alongside the scaling up of CAPSi services to ensure access to high quality services.

Although the scarcity of both financial and human resources limits what can be provided, this paper outlines several options for using existing resources in Brazil more efficiently. Overall, the following four main actions are recommended: (1) to increase capacity building around child and adolescent mental health care for health professionals already working in the public health system; (2) to improve the curriculum for undergraduate training of healthcare workers, especially psychologists, to better prepare them to assist children and adolescents with mental health problems in the public health system; (3) to increase the number of specialized psychologists and child psychiatrists in the public system, offering them higher salaries and better career opportunities; (4) to favor intersector collaboration (e.g. health, education, juvenile justice, child welfare) to more effectively assist children and adolescents with mental health problems. Addressing these gaps in the current system could have immediate impacts on access to care for many children and adolescents in need. Although these types of structural modifications could ameliorate problems with access to care, additional barriers must be taken into account, including cultural beliefs related to mental health (e.g., beliefs in the influence of evil spirits); stigma; a lack of awareness about mental disorders among parents, teachers and health professionals; a lack of information about existing public services; a lack of transportation or inexistence of services near the chidren's househod; financial costs for the family; and a lack of trust or fear regarding treatment.

Finally, the lack of research focused on child and adolescent mental health services must be addressed. Although some studies have emerged, data in this field remains scarce.13,45 Future research must be encouraged to create a comprehensive understanding of the various service system roles and the type of care and evidence for the effectiveness of care currently provided throughout Brazil. This type of investigation will ultimately lead to improved service delivery approaches and improved quality of life for children and adolescents with mental disorders, thus achieving the Grand Challenges in Global Mental Health Initiative goals.

References

1. Kilian R, Losert C, Park A, McDaid D, Knapp M. Cost-effectiveness analysis in child and adolescent mental health problems: an updated review of literature. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2010;12(4):45-57.

2. Zechmeister I, Kilian R, McDaid D. Is it worth investing in mental health promotion and prevention of mental illness? A systematic review of the evidence from economic evaluations. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:20.

3. Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, Whiteford H. Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet. 2007;370:878-89.

4. Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2005;62(6):603-13.

5. Paula CS, Vedovato MS, Bordin IA, Barros MG, D'Antino ME, Mercadante MT. Mental health and violence among sixth grade students from a city in the state of São Paulo. Rev Saude Publica, 2008;42(3):524-8.

6. Paula CS, Duarte CS, Bordin IA. Prevalence of mental health problems in children and adolescents from the outskirts of Sao Paulo City: treatment needs and service capacity evaluation. Rev Bras Psiquiatr, 2007;29(1):11-7.

7. Paula CS, Barros MGS, Vedovato SM, D'Antino MEF, Mercadante MT. Problemas de saúde mental em adolescentes: como identificá-los? Mental health problems in adolescents: how to identify them? Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2006;28(3):254-5.

8. Fleitlich-Bilyk B, Goodman R. Prevalence of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders in southeast Brazil. Journal of the J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(6):727-34.

9. Merikangas KR, He JP, Brody D, Fisher PW, Bourdon K, Koretz DS. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders among U.S. children in the 2001-2004 NHANES. Pediatr. 2010;125(1):75-81.

10. Alarcón RD, Aguilar-Gaxiola SA. Mental health policy developments in Latin America. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(4):483-90.

11. Collins PY, Patel V, Joestl SS, March D, Insel TR, Daar AS, Scientific Advisory Board, and Executive Committee of the Grand Challenges on Global Mental Health. Grand challenges in global mental health. Nature. 2011;475:27-30.

12. Andreoli SB. Serviços de saúde mental no Brasil. In: Mello MF, Mello AAF, Kohn R. Epidemiologia da saude mental no Brasil. Porto Alegre, RS: Artmed; 2007. pp. 85-100.

13. Paula CS, Nakamura E, Wissow L, Bordin IA, Nascimento R, Leite A, Cunha A, Martin D. Primary care and children's mental health in Brazil. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9(4):249-55.

14. De Lima MS, Hotopf M, Mari JJ, Beria J, De Bastos AB, Mann A. Psychiatric disorder and the use of benzodiazepines: an example of the inverse care law from Brazil. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34(6):316-22.

15. Couto MCV, Duarte CS, Delgado PGG. A saúde mental infantil na Saúde Pública brasileira: situação atual e desafios; Child mental health and Public Health in Brazil: current situation and challenges. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2008;30(4):390-8.

16. Diário Oficial of the Federative Republic of Brazil. ECA: The Brazilian Child and Adolescent Rights Act. [http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/L8069.htm]; 1990.

17. Duarte CS, Rizzini I, Hoven C, Carlson M, Earls FJ. The Evolution of Child Rights Councils in Brazil. Int J Child Right. 2007;15:269-82.

18. Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. Portaria nº 336/GM de 19 de fevereiro de 2002. Diário Oficial da União. [http://portal.saude.gov.br/portal/arquivos/pdf/Portaria%20GM%20336-2002.pdf.2002] .

19. Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. Portaria nº 189/GM de 20 de março de 2002. Diário Oficial da União. [www.mp.go.gov.br/portalweb/hp/2/docs/189.pdf.2002] .

20. Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. Departamento de Atenção Básica: Saúde em Números. [http://dab.saude.gov.br/abnumeros.php.2011] .

21. Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. Cadastro Nacional de Estabelecimentos de Saúde -CNES. Year [cited. Secretaria Municial de Saúde - SIASUS/APAC. [http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/deftohtm.exe?cnes/cnv/prid02br.def.2011] .

22. Paula CS, Ribeiro SH, Fombonne E, Mercadante MT. Brief report: prevalence of pervasive developmental disorder in Brazil: a pilot study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41(12):1738-42.

23. Hoffmann MCCL, Santos DN, Mota ELA. Caracterização dos usuários e dos serviços prestados por Centros de Atenção Psicossocial e Infanto-juvenil. Cad Saude Publica. 2008 24(3):633-42.

24. Andrade LOMD, Barreto ICDHC, Bezerra RC. Atenção primária à saúde e estratégia saúde da família. In: Campos GWS. Tratado de saúde coletiva. Rio de Janeiro: Hucitec; Fiocruz; 2006. pp. 783-836.

25. Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. Cadernos de Atenção básica: Diretrizes do NASF - Núcleo de Atenção à Saúde da Família. [http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/caderno_atencao_basica_diretrizes_nasf.pdf]; 2009.

26. Peres EM, Andrade AM, Dal Poz MR, Grande NR. The practice of physicians and nurses in the Brazilian Family Health Program-evidences of change in the delivery health care model. Hum Resour Health. 2006;4:25.

27. Bruckner TA, Scheffler RM, Shen G, Yoon J, Chisholm D, Morris J, Fulton BD, Dal Poz MR, Saxena S. The mental health workforce gap in low- and middle-income countries: a needs-based approach. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:184-94.

28. Mateus MD, Mari JJ, Delgado PGG, Almeida-Filho N, Barrett T, Gerolin J, et al. The mental health system in Brazil: Policies and future challenges. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2008;2(1):12.

29. Associação Brasileira de Psiquiatria. Infância e Adolescência. Available at: [http://www.abpbrasil.org.br/newsletter/departamentos_abril07/pag_1.html]; 2007.

30. WHO. Atlas: Child and adolescent mental health resources: Global concerns: implications for the future. Geneve: World Health Organization; 2005.

31. Kakuma R, Minas H, van Ginneken N, Dal Poz MR, Desiraju K, Morris JE, Saxena S, Scheffler RM. Human resources for mental health care: current situation and strategies for action. Lancet. 2011;378(9803):1654-63.

32. WHO. Mental health atlas, 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011.

33. Ministério da Educação do Brasil. Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para os cursos de graduação em Psicologia -Resolução CNE/CES 5/2011. [http://www.abepsi.org.br/portal/wpcontent/uploads/2011/07/DCN-2011.pdf]; 2011.

34. Dimenstein MDB. O psicólogo nas Unidades Básicas de Saúde: desafios para a formação e atuação de profissionais. Estud Psicol. 1998;3(1):53-81.

35. Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. Caminhos para uma política de saúde mental infanto-juvenil. [http://dtr2001.saude.gov.br/editora/produtos/livros/pdf/05_0379_M.pdf]; 2005.

36. Stein RE, Horwitz SM, Storfer-Isser A, Heneghan A, Olson L, Hoagwood KE. Do pediatricians think they are responsible for identification and management of child mental health problems? Results of the AAP periodic survey. Ambul Pediatr. 2008;8(1):11-7.

37. Wissow L, Gadomski A, Roter D, Larson S, Lewis B, Brown J. Aspects of mental health communication skills training that predict parent and child outcomes in pediatric primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82(2):226-32.

38. Wissow LS, Gadomski A, Roter D, Larison S, Horn I, Bartlett E, et al. A cluster-randomized trial of mental health communication skills for pediatric generalists. Pediatr. 2008;121(2):266-75.

39. Tanaka OY, Lauridsen-Ribeiro E. Desafio para a Atenção Básica: Incorporação da Assistência em Saúde Mental. Cad Saude Publica. 2006;22(9):1845-53.

40. Kolko D, Campo J, Kelleher K, Cheng Y. Improving Access to Care and Clinical Outcome for Pediatric Behavioral Problems: A Randomized Trial of a Nurse-Administered Intervention in Primary Care. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2010;31(5):393-404.

41. Evans-Lacko SE, Zeber JE, Gonzalez JM, Olvera RL. Medical comorbidity among youth diagnosed with bipolar disorder in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009 70(10):1461-6.

42. Knapp M, McDaid D, Parsonage M. Mental health promotion and prevention: the economic case. Personal Social Services Research Unit, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK; 2011.

43. Kieling C, Baker-Henningham H, Belfer M, Conti G, Ertem I, Omigbodun O, Rohde LA, Srinath S, Ulkuer N, Rahman A. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. Lancet. 2011;378(9801):1515-25.

44. Gore FM, Bloem PJ, Patton GC, Ferguson J, Joseph V, Coffey C, Sawyer SM, Mathers CD. Global burden of disease in young people aged 10-24 years: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2011;377(9783):2093-102.

45. Mercadante MT, Evans-Lacko S, Paula CS. Perspectives of intellectual disability in Latin American countries: epidemiology, policy, and services for children and adults. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22(5):469-74.

Received on December 16, 2011; accepted on April 1, 2012

- 1. Kilian R, Losert C, Park A, McDaid D, Knapp M. Cost-effectiveness analysis in child and adolescent mental health problems: an updated review of literature. Int J Ment Health Promot. 2010;12(4):45-57.

- 2. Zechmeister I, Kilian R, McDaid D. Is it worth investing in mental health promotion and prevention of mental illness? A systematic review of the evidence from economic evaluations. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:20.

- 3. Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, Whiteford H. Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet. 2007;370:878-89.

- 4. Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2005;62(6):603-13.

- 5. Paula CS, Vedovato MS, Bordin IA, Barros MG, D'Antino ME, Mercadante MT. Mental health and violence among sixth grade students from a city in the state of São Paulo. Rev Saude Publica, 2008;42(3):524-8.

- 6. Paula CS, Duarte CS, Bordin IA. Prevalence of mental health problems in children and adolescents from the outskirts of Sao Paulo City: treatment needs and service capacity evaluation. Rev Bras Psiquiatr, 2007;29(1):11-7.

- 7. Paula CS, Barros MGS, Vedovato SM, D'Antino MEF, Mercadante MT. Problemas de saúde mental em adolescentes: como identificá-los? Mental health problems in adolescents: how to identify them? Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2006;28(3):254-5.

- 8. Fleitlich-Bilyk B, Goodman R. Prevalence of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders in southeast Brazil. Journal of the J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(6):727-34.

- 9. Merikangas KR, He JP, Brody D, Fisher PW, Bourdon K, Koretz DS. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders among U.S. children in the 2001-2004 NHANES. Pediatr. 2010;125(1):75-81.

- 10. Alarcón RD, Aguilar-Gaxiola SA. Mental health policy developments in Latin America. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(4):483-90.

- 11. Collins PY, Patel V, Joestl SS, March D, Insel TR, Daar AS, Scientific Advisory Board, and Executive Committee of the Grand Challenges on Global Mental Health. Grand challenges in global mental health. Nature. 2011;475:27-30.

- 12. Andreoli SB. Serviços de saúde mental no Brasil. In: Mello MF, Mello AAF, Kohn R. Epidemiologia da saude mental no Brasil. Porto Alegre, RS: Artmed; 2007. pp. 85-100.

- 13. Paula CS, Nakamura E, Wissow L, Bordin IA, Nascimento R, Leite A, Cunha A, Martin D. Primary care and children's mental health in Brazil. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9(4):249-55.

- 14. De Lima MS, Hotopf M, Mari JJ, Beria J, De Bastos AB, Mann A. Psychiatric disorder and the use of benzodiazepines: an example of the inverse care law from Brazil. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34(6):316-22.

- 15. Couto MCV, Duarte CS, Delgado PGG. A saúde mental infantil na Saúde Pública brasileira: situação atual e desafios; Child mental health and Public Health in Brazil: current situation and challenges. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2008;30(4):390-8.

- 16. Diário Oficial of the Federative Republic of Brazil. ECA: The Brazilian Child and Adolescent Rights Act. [http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/L8069.htm]; 1990.

- 17. Duarte CS, Rizzini I, Hoven C, Carlson M, Earls FJ. The Evolution of Child Rights Councils in Brazil. Int J Child Right. 2007;15:269-82.

- 18. Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. Portaria nş 336/GM de 19 de fevereiro de 2002. Diário Oficial da União. [http://portal.saude.gov.br/portal/arquivos/pdf/Portaria%20GM%20336-2002.pdf.2002]

- 19. Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. Portaria nş 189/GM de 20 de março de 2002. Diário Oficial da União. [www.mp.go.gov.br/portalweb/hp/2/docs/189.pdf.2002]

- 20. Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. Departamento de Atenção Básica: Saúde em Números. [http://dab.saude.gov.br/abnumeros.php.2011]

- 21. Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. Cadastro Nacional de Estabelecimentos de Saúde -CNES. Year [cited. Secretaria Municial de Saúde - SIASUS/APAC. [http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/deftohtm.exe?cnes/cnv/prid02br.def.2011]

- 22. Paula CS, Ribeiro SH, Fombonne E, Mercadante MT. Brief report: prevalence of pervasive developmental disorder in Brazil: a pilot study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41(12):1738-42.

- 23. Hoffmann MCCL, Santos DN, Mota ELA. Caracterização dos usuários e dos serviços prestados por Centros de Atenção Psicossocial e Infanto-juvenil. Cad Saude Publica. 2008 24(3):633-42.

- 25. Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. Cadernos de Atenção básica: Diretrizes do NASF - Núcleo de Atenção à Saúde da Família. [http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/caderno_atencao_basica_diretrizes_nasf.pdf]; 2009.

- 26. Peres EM, Andrade AM, Dal Poz MR, Grande NR. The practice of physicians and nurses in the Brazilian Family Health Program-evidences of change in the delivery health care model. Hum Resour Health. 2006;4:25.

- 27. Bruckner TA, Scheffler RM, Shen G, Yoon J, Chisholm D, Morris J, Fulton BD, Dal Poz MR, Saxena S. The mental health workforce gap in low- and middle-income countries: a needs-based approach. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:184-94.

- 28. Mateus MD, Mari JJ, Delgado PGG, Almeida-Filho N, Barrett T, Gerolin J, et al. The mental health system in Brazil: Policies and future challenges. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2008;2(1):12.

- 29. Associação Brasileira de Psiquiatria. Infância e Adolescência. Available at: [http://www.abpbrasil.org.br/newsletter/departamentos_abril07/pag_1.html]; 2007.

- 30. WHO. Atlas: Child and adolescent mental health resources: Global concerns: implications for the future. Geneve: World Health Organization; 2005.

- 31. Kakuma R, Minas H, van Ginneken N, Dal Poz MR, Desiraju K, Morris JE, Saxena S, Scheffler RM. Human resources for mental health care: current situation and strategies for action. Lancet. 2011;378(9803):1654-63.

- 32. WHO. Mental health atlas, 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011.

-

33Ministério da Educação do Brasil. Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para os cursos de graduação em Psicologia -Resolução CNE/CES 5/2011. [http://www.abepsi.org.br/portal/wpcontent/uploads/2011/07/DCN-2011.pdf]; 2011.

- 34. Dimenstein MDB. O psicólogo nas Unidades Básicas de Saúde: desafios para a formação e atuação de profissionais. Estud Psicol. 1998;3(1):53-81.

- 35. Ministério da Saúde do Brasil. Caminhos para uma política de saúde mental infanto-juvenil. [http://dtr2001.saude.gov.br/editora/produtos/livros/pdf/05_0379_M.pdf]; 2005.

- 36. Stein RE, Horwitz SM, Storfer-Isser A, Heneghan A, Olson L, Hoagwood KE. Do pediatricians think they are responsible for identification and management of child mental health problems? Results of the AAP periodic survey. Ambul Pediatr. 2008;8(1):11-7.

- 37. Wissow L, Gadomski A, Roter D, Larson S, Lewis B, Brown J. Aspects of mental health communication skills training that predict parent and child outcomes in pediatric primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82(2):226-32.

- 38. Wissow LS, Gadomski A, Roter D, Larison S, Horn I, Bartlett E, et al. A cluster-randomized trial of mental health communication skills for pediatric generalists. Pediatr. 2008;121(2):266-75.

- 39. Tanaka OY, Lauridsen-Ribeiro E. Desafio para a Atenção Básica: Incorporação da Assistência em Saúde Mental. Cad Saude Publica. 2006;22(9):1845-53.

- 40. Kolko D, Campo J, Kelleher K, Cheng Y. Improving Access to Care and Clinical Outcome for Pediatric Behavioral Problems: A Randomized Trial of a Nurse-Administered Intervention in Primary Care. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2010;31(5):393-404.

- 41. Evans-Lacko SE, Zeber JE, Gonzalez JM, Olvera RL. Medical comorbidity among youth diagnosed with bipolar disorder in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009 70(10):1461-6.

- 42. Knapp M, McDaid D, Parsonage M. Mental health promotion and prevention: the economic case. Personal Social Services Research Unit, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK; 2011.

- 43. Kieling C, Baker-Henningham H, Belfer M, Conti G, Ertem I, Omigbodun O, Rohde LA, Srinath S, Ulkuer N, Rahman A. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. Lancet. 2011;378(9801):1515-25.

- 44. Gore FM, Bloem PJ, Patton GC, Ferguson J, Joseph V, Coffey C, Sawyer SM, Mathers CD. Global burden of disease in young people aged 10-24 years: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2011;377(9783):2093-102.

- 45. Mercadante MT, Evans-Lacko S, Paula CS. Perspectives of intellectual disability in Latin American countries: epidemiology, policy, and services for children and adults. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22(5):469-74.

Corresponding author:

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

14 Nov 2012 -

Date of issue

Oct 2012

History

-

Received

16 Dec 2011 -

Accepted

01 Apr 2012