Abstract

Objective:

The effects of exposure to violent events in adolescence have not been sufficiently studied in middle-income countries such as Brazil. The aims of this study are to investigate the prevalence of psychiatric disorders among 12-year-olds in two neighborhoods with different socioeconomic status (SES) levels in São Paulo and to examine the influence of previous violent events and SES on the prevalence of psychiatric disorders.

Methods:

Students from nine public schools in two neighborhoods of São Paulo were recruited. Students and parents answered questions about demographic characteristics, SES, urbanicity and violent experiences. All participants completed the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS) to obtain DSM-IV diagnoses. The data were analyzed using weighted logistic regression with neighborhood stratification after adjusting for neighborhood characteristics, gender, SES and previous traumatic events.

Results:

The sample included 180 individuals, of whom 61.3% were from low SES and 39.3% had experienced a traumatic event. The weighted prevalence of psychiatric disorders was 21.7%. Having experienced a traumatic event and having low SES were associated with having an internalizing (adjusted OR = 5.46; 2.17-13.74) or externalizing disorder (adjusted OR = 4.33; 1.85-10.15).

Conclusions:

Investment in reducing SES inequalities and preventing violent events during childhood may improve the mental health of youths from low SES backgrounds.

Adolescents; child psychiatry; epidemiology; social and political issues; violence/aggression

Introduction

In 2011, the Grand Challenges in Global Mental Health Initiative (GCGMHI) described the main priorities for mental health research for the next 10 years. Research on the relationships between environmental exposure and mental health problems was among these priorities. According to this document, a life course approach should guide researchers, since many mental health problems begin in childhood and continue throughout life.11. Collins PY, Patel V, Joestl SS, March D, Insel TR, Daar AS, et al. Grand challenges in global mental health. Nature. 2011;475:27-30. Mounting evidence appears to indicate that violence and poor neighborhood-level conditions (i.e., poverty and social exclusion) during childhood and adolescence may lead to the development of psychiatric disorders during both youth and adulthood.22. Greger HK, Myhre AK, Lydersen S, Jozefiak T. Previous maltreatment and present mental health in a high-risk adolescent population. Child Abus Negl. 2015;45:122-34.,33. Hartwell H. Social inequality and mental health. J R Soc Promot Health. 2008;128:98. In addition, adolescent mental health has been associated with several psychosocial factors. In addition to neighborhood sociodemographic characteristics,44. Green JG, Alegría M, Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, et al. Neighborhood sociodemographic predictors of serious emotional disturbance (SED) in schools: demonstrating a small area estimation method in the national comorbidity survey (NCS-A) adolescent supplement. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42:111-20.

5. Dupéré V, Leventhal T, Lacourse E. Neighborhood poverty and suicidal thoughts and attempts in late adolescence. Psychol Med. 2009;39:1295-306.-66. Xue Y, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J, Earls FJ. Neighborhood residence and mental health problems of 5- to 11-year-olds. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:554-63. individual-level characteristics, including family and school-related issues, are significant risk factors for the development of mental disorders.77. Pinto AC, Luna IT, Sivla Ade A, Pinheiro PN, Braga VA, Souza AM. [Risk factors associated with mental health issues in adolescents: an integrative review]. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2014;48:555-64.

Although progress has been made in understanding the role of neighborhood-level aspects and childhood violence on adolescent mental disorders, few studies focusing on data from low- and middle-income countries, such as Brazil, have been conducted to date. Such research is of particular interest in these countries, in which deep social inequality exists. Although Brazil is the ninth wealthiest country in the world, it has important social discrepancies, such as per capita income, years of education, and life expectancy. In Brazil, many city-level neighborhoods are largely segregated by socioeconomic and racial/ethnic status.88. Senicato C, Barros MB. Social inequality in health among women in Campinas, São Paulo State, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2012;28:1903-14.

9. Gawryszewski VP, Costa LS. [Social inequality and homicide rates in Sao Paulo City, Brazil]. Rev Saude Publica. 2005;39:191-7.-1010. Neri M, Soares W. [Social inequality and health in Brazil]. Cad Saude Publica. 2002;18:77-87.

Urban violence is considered one of the most important public health problems in Latino countries.1111. Velez-Gomez P, Restrepo-Ochoa DA, Berbesi-Fernandez D, Trejos-Castillo E. Depression and neighborhood violence among children and early adolescents in Medellin, Colombia. Span J Psychol. 2013;16:E64. However, urban violence affects the population unequally; its impact varies by gender, ethnicity, age and social space.1212. Souza ER de, Lima MLC de. Panorama da violência urbana no Brasil e suas capitais. Cienc Saude Colet. 2006;11:1211-22. Among children, exposure to urban violence has been linked to academic difficulties,1313. Henrich CC, Schwab-Stone M, Fanti K, Jones SM, Ruchkin V. The association of community violence exposure with middle-school achievement: a prospective study. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2004;25:327-48. aggressive behavior,1414. McCabe KM, Lucchini SE, Hough RL, Yeh M, Hazen A. The relation between violence exposure and conduct problems among adolescents: a prospective study. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75:575-84. and internalizing symptoms (i.e., symptoms of depression and anxiety).1515. Ho J. Community violence exposure of Southeast Asian American adolescents. J Interpers Violence. 2008;23:136-46. Together with urban violence (neighborhood crime), other aspects of an individual’s neighborhood can be associated with psychiatric disorders.1616. Lowe SR, Quinn JW, Richards CA, Pothen J, Rundle A, Galea S, et al. Childhood trauma and neighborhood-level crime interact in predicting adult posttraumatic stress and major depression symptoms. Child Abus Negl. 2016;51:212-22.

17. Fink DS, Galea S. Life course epidemiology of trauma and related psychopathology in civilian populations. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17:31.-1818. Johns LE, Aiello AE, Cheng C, Galea S, Koenen KC, Uddin M. Neighborhood social cohesion and posttraumatic stress disorder in a community-based sample: findings from the Detroit neighborhood health study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47:1899-906.

Domestic violence also has an impact on child and adolescent mental health.1919. Mohammad ET, Shapiro ER, Wainwright LD, Carter AS. Impacts of family and community violence exposure on child coping and mental health. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2015;43:203-15. A 2012 meta-analysis found a significant association between physical abuse, emotional abuse and neglect in childhood and the future onset of depressive disorder, drug use and suicide attempts. Therefore, all forms of child maltreatment should be considered potential predictors of child and adolescent mental health problems.2020. Culpin I, Stapinski L, Miles ÖB, Araya R, Joinson C. Exposure to socioeconomic adversity in early life and risk of depression at 18 years: the mediating role of locus of control. J Affect Disord. 2015;183:269-78.

21. Hovens JG, Giltay EJ, Spinhoven P, van Hemert AM, Penninx BW. Impact of childhood life events and childhood trauma on the onset and recurrence of depressive and anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:931-8.

22. de Carvalho HW, Pereira R, Frozi J, Bisol LW, Ottoni GL, Lara DR. Childhood trauma is associated with maladaptive personality traits. Child Abus Negl. 2015;44:18-25.

23. Lansford JE, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Crozier J, Kaplow J. A 12-year prospective study of the long-term effects of early child physical maltreatment on psychological, behavioral, and academic problems in adolescence. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:824-30.-2424. Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001349. This is of special interest because psychiatric mental disorders in childhood and adolescence are associated with a disrupted transition to adulthood, even if the disorders do not persist into adulthood or the mental symptoms are subthreshold.2525. Copeland WE, Wolke D, Shanahan L, Costello EJ. Adult functional outcomes of common childhood psychiatric problems: a prospective, longitudinal study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:892-9.

Children and adolescents living in poverty are at high risk of multiple exposures to violence.1919. Mohammad ET, Shapiro ER, Wainwright LD, Carter AS. Impacts of family and community violence exposure on child coping and mental health. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2015;43:203-15. The relationship between socioeconomic status (SES) and violence and their impact on child and adolescent psychopathology, however, is still unclear. Although this association has been reported in a number of studies, longitudinal studies are needed to disentangle causal relationships.1919. Mohammad ET, Shapiro ER, Wainwright LD, Carter AS. Impacts of family and community violence exposure on child coping and mental health. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2015;43:203-15.

The aims of this study were as follows: 1) to investigate the prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders (depression, general anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder) among 12-year-old youth in two neighborhoods with different SES levels in São Paulo, Brazil; and 2) to examine the influence of previous violent events (mugging, aggression followed by mugging, domestic violence, physical abuse and sexual abuse) and SES on the prevalence of psychiatric disorders.

Methods

Study design and sample selection

The data were derived from a cross-sectional survey of school-attending youths in two very different neighborhoods in São Paulo. One of the neighborhoods, Vila Mariana, has low exposure to urban violence (13 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants) and a high Human Development Index (HDI) (0.950). The other neighborhood, Capão Redondo, has high exposure to urban violence (47 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants) and a lower HDI (0.782), being one of the most violent neighborhoods in the city of São Paulo. Both neighborhoods are in the southern region of the city of São Paulo, which comprises 3.6 million residents according to the 2010 Census (the total population of the city of São Paulo was 11.4 million).

Nine public schools were selected according to location: 5 in Vila Mariana and 4 in Capão Redondo, all from the poorest regions of each neighborhood. All students born between January 1, 2002 and December 31, 2002 and regularly enrolled in the 7th grade in 2014 were recruited (n=416). The caregivers of all students received a letter explaining the study’s research goals and procedures. Subsequently, the chief field supervisor telephoned all the caregivers to invite them to participate and to clarify questions about the research goals and procedures.

For a two-sided test of the equality of odds ratios at a significance level of 5%, a sample size of 180 subjects has at least 80% power to detect a difference when the true value of the odds ratio lies above 2.5 and the lowest disease prevalence is between 0.15 and 0.50.2626. Lwanga SK, Lemeshow S. Sample size determination in health studies: a practical manual. Geneva: WHO; 1991.

According to school records, only 210 of the 416 registered students had an active telephone or cell phone number at which they could be contacted for recruitment. Most of the Brazilian population has an active cell phone (84% of Brazilians have an active cell phone, including 97% of Brazilians with the highest SES and 64% of Brazilians with the lowest SES)2727. Comitê Gestor da Internet no Brasil. Pesquisa sobre o uso das tecnologias da informação e comunicação nos domicílios brasileiros – TIC domicílios 2014 [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2017 Jul 31]. www.cetic.br/media/docs/publicacoes/2/TIC_Domicilios_2014_livro_eletronico.pdf

www.cetic.br/media/docs/publicacoes/2/TI...

; therefore, outdated school telephone records were the likely cause of this discrepancy. All 210 of these students were contacted and 180 agreed to participate (an 85% acceptance rate).

Data collection and instruments

Two face-to-face interviews were conducted for each participant: one with the adolescent and one with the caregivers. Both interviews were conducted by a trained team of interviewers (child and adolescent psychiatrists and psychologists) using LUMIA 635, an app for inserting data into smartphones. The questionnaire included demographic information about the caregivers and child and their SES, including a standardized survey to assess SES called the ABEP index.2828. Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa (ABEP). Critério de Classificação Econômica Brasil [Internet]. São Paulo: ABEP; 2012. [cited 2017 Jul 31]. http://www.abep.org/Servicos/Download.aspx?id=07

http://www.abep.org/Servicos/Download.as...

This index is based on possession of various types of household goods, the head of the household’s educational level, and the number of housekeepers employed. According to their score, ABEP respondents can be sorted into eight subgroups, with A1 being the highest economic stratum and E the lowest.

The participants’ lifetime diagnoses of mental disorders were measured with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL). This instrument is a semi-structured psychiatric interview that ascertains both lifetime and current diagnostic status based on DSM-IV criteria, and it has been translated into Brazilian Portuguese.2929. Brasil HHA, Bordin IAS. Versão Brasileira da schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-aged children para crianças e adolescentes de 6 a 18 anos. 1996 Oct [cited 2017 Jul 31]. http://repositorio.unifesp.br/bitstream/handle/11600/18619/Publico-18619_pt2.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

http://repositorio.unifesp.br/bitstream/...

This instrument is designed for use by trained non-clinicians and clinicians. The K-SADS-PL is intended for children 6-18 years old and their parents, containing parallel questions for the parents and children that are asked separately. It includes three components: an introductory interview (demographic, health, and background information), a screening interview (20 diagnostic areas), and diagnostic supplements. The K-SADS-PL has the best test-retest reliability for anxious disorders and affective disorders.3030. Matuschek T, Jaeger S, Stadelmann S, Dölling K, Grunewald M, Weis S, et al. Implementing the K-SADS-PL as a standard diagnostic tool: effects on clinical diagnoses. Psychiatry Res. 2016;236:119-24.,3131. Renou S, Hergueta T, Flament M, Mouren-Simeoni MC, Lecrubier Y. [Diagnostic structured interviews in child and adolescent’s psychiatry]. Encephale. 2004;30:122-34. In this study, we used the screening interview and the following sections of the diagnostic supplements: depression, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), conduct disorder (CD), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and substance use/substance use disorders (SUD). All K-SADS-PL results were reviewed by a licensed child psychiatrist trained in the use of the test.

The interviews were conducted at the school, usually on Saturdays (never during class). The participant and his/her caregivers were interviewed separately by different interviewers. The entire interview process (discussing the consent form, answering questions about the study, and the actual interview) ranged from one to two hours, depending on the number of K-SADS-PL supplements used.

Measures

Due to the small sample size, we defined two ranks of SES based on the ABEP scale: high (A1, A2, B1 and B2) and low (C1, C2, D and E). The economic strata of three subjects from different schools in Capão Redondo was not initially determined due to missing data, so they were considered as the most prevalent SES in their schools (low).

Screening for violent events was performed using the PTSD screening interview from the K-SADS-PL. When a youth reported having experienced a mugging, aggression followed by mugging, domestic violence, physical abuse or sexual abuse, this was coded as an occurrence of a violent experience.

Due to the small number of children with any diagnosis according to the DSM-IV criteria, a binary variable was used (past or current diagnosis vs. no diagnosis). In addition to separately analyzing each diagnosis, we separately analyzed combinations of all internalizing disorders (depression, GAD and PTSD) and all externalizing disorders (ODD, CD and ADHD).

Statistical analysis

The analyses were conducted with data weighted to correct for unequal probabilities of selection into the sample. The complex survey design took the stratified sampling design, the difference between the gender distributions in the sample, and the corresponding distributions in each of the neighborhoods into account. Since the schools were fixed and not randomly chosen, the sampling level was students.

First, we conducted exploratory analyses using basic contingency tables with chi-square tests, followed by logistic regression for complex samples. We described the students’ general sociodemographic variables, neighborhood-level scores, violent experiences and psychiatric diagnoses with weighted proportions. A seemingly unrelated logistic regression (SULR) approach was used to simultaneously analyze associations between both responses (internalizing disorders and externalizing disorders) with at least one of the attributes (gender, neighborhood of origin, SES, and violent experience), as well as for possible interactions among these variables in a forward selection method.3232. You J, Zhou H. Inference for seemingly unrelated varying-coefficient nonparametric regression models. Int J Stat Manag Syst. 2010;5:59-83.

The analyses were performed using Stata 13.0, with complex sample procedures to address variance estimation under the complex sample design in these regression models and to estimate all 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). The results are presented as weighted proportions (%wt), adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95%CI.

Ethical aspects

The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Columbia University Institutional Review Board (IRB-AAM4702) and by the Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP) research ethics committee (protocol no. 451.565 of 11/08/2013), provided that participants could participate anonymously, decline to participate, leave questions unanswered, and interrupt their participation at any time. The consent form was explained to both the child and his/her caregiver, and both signed it after any questions had been answered.

Results

Descriptive

Table 1 shows the descriptive results. Among the 180 students included in this study, most were girls (52.4%) and had a low SES (62.4%). The Capão Redondo neighborhood had significantly more adolescents with low SES (69.0%) than the Vila Mariana neighborhood (55.0%; p = 0.012). Regarding violence, 39.9% of the students had experienced at least one violent event. Mugging was the most common violent experience (24.8%; 95%CI 20.4-29.9), followed by domestic violence (17.5%; 95%CI 13.7-22.1) and physical abuse (7.1%; 95%CI 4.7-10.4). The rate of any violent event was similar in both neighborhoods (p = 0.419).

DSM-IV diagnostic criteria

Nearly one-quarter (21.7%; 95%CI 17.4-26.7) of the sample had a psychiatric disorder. Depression was the most common diagnosis (9.5%; 95%CI 6.7-13.4), followed by ADHD (9.3%; 95%CI 6.6-13.0) and GAD (6.1%; 95%CI 3.9-9.5). PTSD was more prevalent in Vila Mariana (6.2%; 95%CI 3.2-11.8) than Capão Redondo (4.0%; 95%CI 2.2-6.9; p = 0.046). Detailed information is presented in Table 1.

A total of 14.0% (95%CI 10.5-18.4) of the sample had an internalizing disorder. Most of them were males (44.8%), from Capão Redondo (41.1%), and with lower SES (68.3%). Another 15.5% (95%CI 11.9-20.0) had an externalizing disorder. Most of them were males (64.1%), from Capão Redondo (54.5%), and with higher SES (81.8%). Almost 60% of the adolescents with any diagnosis had experienced at least one violent event during their lifetime (Table 2).

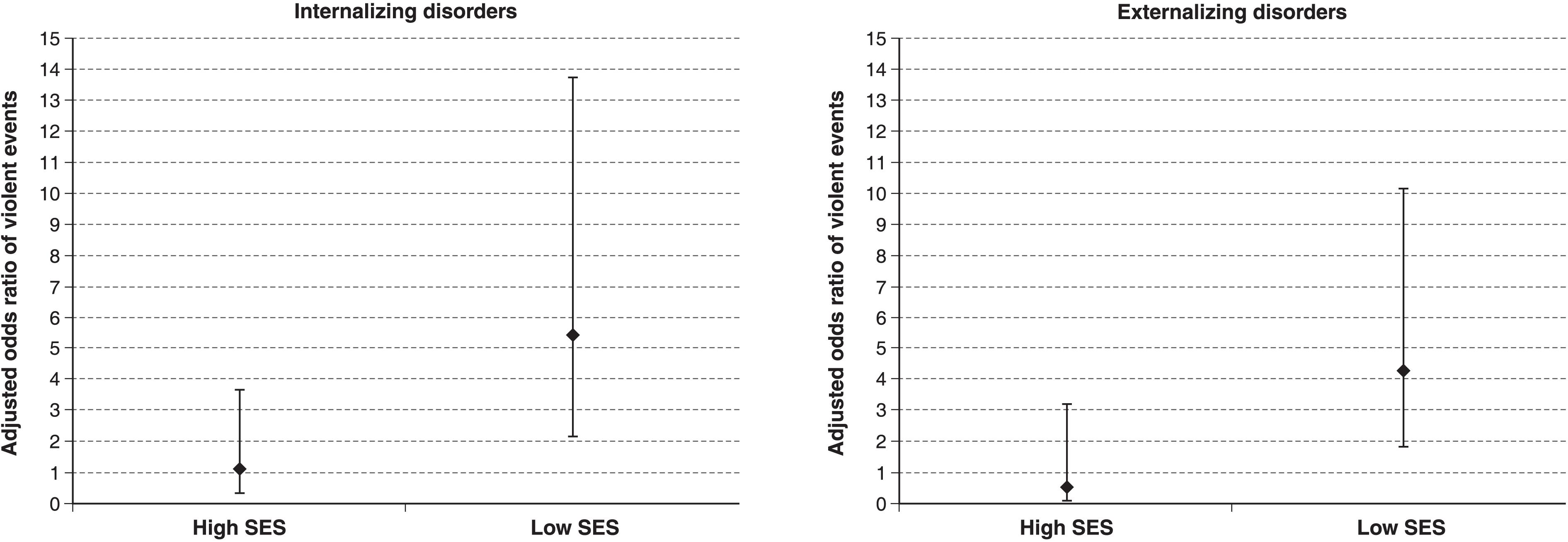

In the logistic regression model, the interaction between SES and violence was statistically significant in both tested models (Table 3). Having experienced any violent event and having low SES were significantly associated with having an internalizing disorder (aOR = 5.46; 2.17-13.74) and with having an externalizing disorder (aOR = 4.33; 1.85-10.15). Having experienced any violent event and having high SES was not associated with having an internalizing or externalizing disorder (p > 0.05). This is graphically represented in Figure 1. Being female (aOR = 2.33; 95%CI 1.13-4.81; p = 0.02) was significantly associated with having an internalizing disorder.

Graphic representation of the interaction between socioeconomic status and violent events on internalizing and externalizing disorders among 180 twelve-year-old public school students from two neighborhoods in Sa˜o Paulo, Brazil, 2014.SES = socioeconomic status according to the ABEP scale.2828. Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa (ABEP). Critério de Classificação Econômica Brasil [Internet]. São Paulo: ABEP; 2012. [cited 2017 Jul 31]. http://www.abep.org/Servicos/Download.aspx?id=07

http://www.abep.org/Servicos/Download.as...

Discussion

Our main finding is that having experienced any violent childhood event and having low SES were significantly associated with both having an internalizing disorder and having an externalizing disorder according to the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria.

A 2015 meta-analysis of 41 studies conducted in 27 countries found a worldwide prevalence rate of mental disorders in children and adolescents of 13.4%. Prevalence rates varied from 19.9% in North America to 8.3% in Africa. Studies that used the K-SADS as the diagnostic interview found a prevalence rate of 15.3% for any mental disorder in the age range of 6 to 18 years.3333. Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, Caye A, Rohde LA. Annual research review: a meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56:345-65. It has previously been established that the prevalence of mental health problems in children in low- and middle-income countries is similar to that in high-income countries.3434. Kieling C, Baker-Henningham H, Belfer M, Conti G, Ertem I, Omigbodun O, et al. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. Lancet. 2011;378:1515-25. In our study, the prevalence of any mental disorder using the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria was similar to those reported in the literature.

Concerning Brazilian prevalence data, studies have used a variety of screening instruments. In a birth cohort of 4,452 11-year-old preadolescents, 10.8% presented with at least one psychiatric disorder according to either the DSM-IV or ICD-10 based on the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), which was completed by caregivers only.3535. Anselmi L, Fleitlich-Bilyk B, Menezes AM, Araújo CL, Rohde LA. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in a Brazilian birth cohort of 11-year-olds. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45:135-42. Using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), Goodman et al.3636. Goodman R, Neves dos Santos D, Robatto Nunes AP, Pereira de Miranda D, Fleitlich-Bilyk B, Almeida Filho N. The Ilha de Maré study: a survey of child mental health problems in a predominantly African-Brazilian rural community. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:11-7. found a 7.0% prevalence of any mental disorder among 519 7- to 14-year-old subjects in a rural Afro-Brazilian community. The screening instruments in these studies differ from the K-SADS because the latter is a diagnostic instrument, and its correct use requires clinical experience. Screening instruments cannot be used to determine diagnoses. Fleitlich-Bilyk et al.3737. Fleitlich-Bilyk B, Goodman R. Prevalence of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders in southeast Brazil. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:727-34. also used a diagnostic instrument other than the K-SADS, namely, the Development and Well-Being Assessment (DAWBA).

Robust findings indicate that social relationships and neighborhood disorder are associated with mental disorders.3838. Kim J. Neighborhood disadvantage and mental health: the role of neighborhood disorder and social relationships. Soc Sci Res. 2010;39:260-71. In our study, having experienced a violent event by the age of 12 was significantly associated with having an internalizing or externalizing disorder. It is important to emphasize that SES was associated with violent events; subjects with low SES exhibited a negative impact from violent experiences on their mental health status. The magnitude of the effect of violent events on internalizing and externalizing disorders is lower in individuals of higher SES. Similar findings were presented by Andrews et al.3939. Andrews AR 3rd, Jobe-Shields L, López CM, Metzger IW, de Arellano MA, Saunders B, et al. Polyvictimization, income, and ethnic differences in trauma-related mental health during adolescence. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50:1223-34. based on data from the National Survey of Adolescents-Replication (NSA-R) study, which was conducted in the US in 2005. These authors examined the mediating and moderating effects of polyvictimization (i.e., the number of types of violent events/victimizations experienced by an individual) and household income on trauma-related mental health symptoms among children and adolescents. Compared to high-income backgrounds, low-income family environments appeared to be a risk factor for negative mental health outcomes following exposure to violence. It is always important to emphasize, however, that association does not imply causation. It is also possible that low SES is associated with a greater number of violent experiences and that these experiences are more intense among low SES neighborhoods.

These theories could explain the impact of violent experiences on the development of mental health disorders. It is well established that violence negatively affects mental health in childhood, adolescence2424. Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001349.,4040. Zolotor AJ, Runyan DK. Social capital, family violence, and neglect. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e1124-31.,4141. Frissen A, Lieverse R, Drukker M, van Winkel R, Delespaul P; GROUP Investigators. Childhood trauma and childhood urbanicity in relation to psychotic disorder. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50:1481-8. and adulthood.4242. Ghafoori B, Fisher DG, Koresteleva O, Hong M. Factors associated with mental health service use in urban, impoverished, trauma-exposed adults. Psychol Serv. 2014;11:451-9.

43. Ghafoori B, Barragan B, Palinkas L. Mental health service use among trauma-exposed adults: a mixed-methods study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202:239-46.-4444. Keyser-Marcus L, Alvanzo A, Rieckmann T, Thacker L, Sepulveda A, Forcehimes A, et al. Trauma, gender, and mental health symptoms in individuals with substance use disorders. J Interpers Violence. 2015;30:3-24. Of even greater significance is the impact of these violent experiences throughout the lifespan; the consequences of exposure to violence continue to be felt throughout life, leading to an increased disease burden.44. Green JG, Alegría M, Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, et al. Neighborhood sociodemographic predictors of serious emotional disturbance (SED) in schools: demonstrating a small area estimation method in the national comorbidity survey (NCS-A) adolescent supplement. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42:111-20.,3939. Andrews AR 3rd, Jobe-Shields L, López CM, Metzger IW, de Arellano MA, Saunders B, et al. Polyvictimization, income, and ethnic differences in trauma-related mental health during adolescence. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50:1223-34.,4545. Rossiter A, Byrne F, Wota AP, Nisar Z, Ofuafor T, Murray I, et al. Childhood trauma levels in individuals attending adult mental health services: an evaluation of clinical records and structured measurement of childhood trauma. Child Abus Negl. 2015;44:36-45.

The literature still lacks consensus about the definition of a violent experience. In our study, we investigated mugging, aggression followed by mugging, domestic violence, physical abuse and sexual abuse. Moreover, the impact of these violent experiences may vary according to the victim’s age when they occur, since neuroplasticity varies according to neurodevelopment. Therefore, studies focusing on specific age ranges are necessary.2424. Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001349.

Concerning internalizing disorders, we found that females were at higher risk of an internalizing disorder. Similarly, we found that adolescents attending schools in Vila Mariana, which had less urban violence than Capão Redondo, had a higher risk of an internalizing disorder. In a study of 425 children from the 3rd to 5th grade in six Baltimore public schools, Milan et al.4646. Milam AJ, Furr-Holden CD, Whitaker D, Smart M, Leaf P, Cooley-Strickland M. Neighborhood environment and internalizing problems in African American children. Community Ment Health J. 2012;48:39-44. found that gender moderated the relationship between neighborhood context and mental health problems. Females were more adversely impacted by disordered neighborhood environments. The authors hypothesized that boys in hazardous environments develop coping strategies that include externalizing behaviors. In contrast, girls’ coping strategies lead to more internalizing symptoms. Similar findings have been reported concerning the influence of neighborhoods with high levels of violence on the development of internalizing disorders.4747. Rabinowitz JA, Drabick DA, Reynolds MD. Youth withdrawal moderates the relationhips between neighborhood factors and internalizing symptoms in adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 2016;45:427-39.

48. Goldner JS, Quimby D, Richards MH, Zakaryan A, Miller S, Dickson D, et al. Relations of parenting to adolescent externalizing and internalizing distress moderated by perception of neighborhood danger. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2016;45:141-54.-4949. White RM, Roosa MW. Neighborhood contexts, fathers, and Mexican American young adolescents' internalizing symptoms. J Marriage Fam. 2012;74:152-66.

Some limitations of this study should be noted. Although careful procedures were used to select the sample, we did not use a population-based representative sample. In addition, the sample size was small, which did not allow an investigation of each psychiatric disorder separately. Therefore, our findings should be extrapolated with caution. Moreover, because this was a school-based sample, some of the most severe cases may not have been included due to having dropped out of school already. However, we can hypothesize that among all the children invited to participate, those with the most severe symptoms may have been more likely to agree. In addition, this was a cross-sectional survey, and we reiterate that association does not imply causation. Finally, the relationship between the features of urbanicity is very complex. Many of the causal arrows are likely bidirectional, since low urbanicity can be both a cause and a consequence of mental disorders. More studies are necessary to clarify specific causal pathways.5050. Meléndez L. Disease and "broken windows". Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:A657; author reply A657.

In conclusion, SES was associated with the impact of exposure to violence in the development of mental disorders in youths. This finding has important implications for public health. Investment in reducing inequality could have a buffer effect on violent events for psychiatric symptoms. Strategies to prevent violent events during childhood, such as physical and sexual abuse and domestic violence, may also have a positive impact on adolescent mental health.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Columbia President’s Global Innovation Fund (principal investigator: SSM). We would like to acknowledge Prof. Sandro Galea and Prof. Magdalena Cerdá for their insightful comments.

References

-

1Collins PY, Patel V, Joestl SS, March D, Insel TR, Daar AS, et al. Grand challenges in global mental health. Nature. 2011;475:27-30.

-

2Greger HK, Myhre AK, Lydersen S, Jozefiak T. Previous maltreatment and present mental health in a high-risk adolescent population. Child Abus Negl. 2015;45:122-34.

-

3Hartwell H. Social inequality and mental health. J R Soc Promot Health. 2008;128:98.

-

4Green JG, Alegría M, Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, et al. Neighborhood sociodemographic predictors of serious emotional disturbance (SED) in schools: demonstrating a small area estimation method in the national comorbidity survey (NCS-A) adolescent supplement. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42:111-20.

-

5Dupéré V, Leventhal T, Lacourse E. Neighborhood poverty and suicidal thoughts and attempts in late adolescence. Psychol Med. 2009;39:1295-306.

-

6Xue Y, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J, Earls FJ. Neighborhood residence and mental health problems of 5- to 11-year-olds. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:554-63.

-

7Pinto AC, Luna IT, Sivla Ade A, Pinheiro PN, Braga VA, Souza AM. [Risk factors associated with mental health issues in adolescents: an integrative review]. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2014;48:555-64.

-

8Senicato C, Barros MB. Social inequality in health among women in Campinas, São Paulo State, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2012;28:1903-14.

-

9Gawryszewski VP, Costa LS. [Social inequality and homicide rates in Sao Paulo City, Brazil]. Rev Saude Publica. 2005;39:191-7.

-

10Neri M, Soares W. [Social inequality and health in Brazil]. Cad Saude Publica. 2002;18:77-87.

-

11Velez-Gomez P, Restrepo-Ochoa DA, Berbesi-Fernandez D, Trejos-Castillo E. Depression and neighborhood violence among children and early adolescents in Medellin, Colombia. Span J Psychol. 2013;16:E64.

-

12Souza ER de, Lima MLC de. Panorama da violência urbana no Brasil e suas capitais. Cienc Saude Colet. 2006;11:1211-22.

-

13Henrich CC, Schwab-Stone M, Fanti K, Jones SM, Ruchkin V. The association of community violence exposure with middle-school achievement: a prospective study. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2004;25:327-48.

-

14McCabe KM, Lucchini SE, Hough RL, Yeh M, Hazen A. The relation between violence exposure and conduct problems among adolescents: a prospective study. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75:575-84.

-

15Ho J. Community violence exposure of Southeast Asian American adolescents. J Interpers Violence. 2008;23:136-46.

-

16Lowe SR, Quinn JW, Richards CA, Pothen J, Rundle A, Galea S, et al. Childhood trauma and neighborhood-level crime interact in predicting adult posttraumatic stress and major depression symptoms. Child Abus Negl. 2016;51:212-22.

-

17Fink DS, Galea S. Life course epidemiology of trauma and related psychopathology in civilian populations. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17:31.

-

18Johns LE, Aiello AE, Cheng C, Galea S, Koenen KC, Uddin M. Neighborhood social cohesion and posttraumatic stress disorder in a community-based sample: findings from the Detroit neighborhood health study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47:1899-906.

-

19Mohammad ET, Shapiro ER, Wainwright LD, Carter AS. Impacts of family and community violence exposure on child coping and mental health. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2015;43:203-15.

-

20Culpin I, Stapinski L, Miles ÖB, Araya R, Joinson C. Exposure to socioeconomic adversity in early life and risk of depression at 18 years: the mediating role of locus of control. J Affect Disord. 2015;183:269-78.

-

21Hovens JG, Giltay EJ, Spinhoven P, van Hemert AM, Penninx BW. Impact of childhood life events and childhood trauma on the onset and recurrence of depressive and anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:931-8.

-

22de Carvalho HW, Pereira R, Frozi J, Bisol LW, Ottoni GL, Lara DR. Childhood trauma is associated with maladaptive personality traits. Child Abus Negl. 2015;44:18-25.

-

23Lansford JE, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Crozier J, Kaplow J. A 12-year prospective study of the long-term effects of early child physical maltreatment on psychological, behavioral, and academic problems in adolescence. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:824-30.

-

24Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001349.

-

25Copeland WE, Wolke D, Shanahan L, Costello EJ. Adult functional outcomes of common childhood psychiatric problems: a prospective, longitudinal study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:892-9.

-

26Lwanga SK, Lemeshow S. Sample size determination in health studies: a practical manual. Geneva: WHO; 1991.

-

27Comitê Gestor da Internet no Brasil. Pesquisa sobre o uso das tecnologias da informação e comunicação nos domicílios brasileiros – TIC domicílios 2014 [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2017 Jul 31]. www.cetic.br/media/docs/publicacoes/2/TIC_Domicilios_2014_livro_eletronico.pdf

» www.cetic.br/media/docs/publicacoes/2/TIC_Domicilios_2014_livro_eletronico.pdf -

28Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa (ABEP). Critério de Classificação Econômica Brasil [Internet]. São Paulo: ABEP; 2012. [cited 2017 Jul 31]. http://www.abep.org/Servicos/Download.aspx?id=07

» http://www.abep.org/Servicos/Download.aspx?id=07 -

29Brasil HHA, Bordin IAS. Versão Brasileira da schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-aged children para crianças e adolescentes de 6 a 18 anos. 1996 Oct [cited 2017 Jul 31]. http://repositorio.unifesp.br/bitstream/handle/11600/18619/Publico-18619_pt2.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

» http://repositorio.unifesp.br/bitstream/handle/11600/18619/Publico-18619_pt2.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y -

30Matuschek T, Jaeger S, Stadelmann S, Dölling K, Grunewald M, Weis S, et al. Implementing the K-SADS-PL as a standard diagnostic tool: effects on clinical diagnoses. Psychiatry Res. 2016;236:119-24.

-

31Renou S, Hergueta T, Flament M, Mouren-Simeoni MC, Lecrubier Y. [Diagnostic structured interviews in child and adolescent’s psychiatry]. Encephale. 2004;30:122-34.

-

32You J, Zhou H. Inference for seemingly unrelated varying-coefficient nonparametric regression models. Int J Stat Manag Syst. 2010;5:59-83.

-

33Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, Caye A, Rohde LA. Annual research review: a meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56:345-65.

-

34Kieling C, Baker-Henningham H, Belfer M, Conti G, Ertem I, Omigbodun O, et al. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. Lancet. 2011;378:1515-25.

-

35Anselmi L, Fleitlich-Bilyk B, Menezes AM, Araújo CL, Rohde LA. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in a Brazilian birth cohort of 11-year-olds. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45:135-42.

-

36Goodman R, Neves dos Santos D, Robatto Nunes AP, Pereira de Miranda D, Fleitlich-Bilyk B, Almeida Filho N. The Ilha de Maré study: a survey of child mental health problems in a predominantly African-Brazilian rural community. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:11-7.

-

37Fleitlich-Bilyk B, Goodman R. Prevalence of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders in southeast Brazil. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:727-34.

-

38Kim J. Neighborhood disadvantage and mental health: the role of neighborhood disorder and social relationships. Soc Sci Res. 2010;39:260-71.

-

39Andrews AR 3rd, Jobe-Shields L, López CM, Metzger IW, de Arellano MA, Saunders B, et al. Polyvictimization, income, and ethnic differences in trauma-related mental health during adolescence. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50:1223-34.

-

40Zolotor AJ, Runyan DK. Social capital, family violence, and neglect. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e1124-31.

-

41Frissen A, Lieverse R, Drukker M, van Winkel R, Delespaul P; GROUP Investigators. Childhood trauma and childhood urbanicity in relation to psychotic disorder. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50:1481-8.

-

42Ghafoori B, Fisher DG, Koresteleva O, Hong M. Factors associated with mental health service use in urban, impoverished, trauma-exposed adults. Psychol Serv. 2014;11:451-9.

-

43Ghafoori B, Barragan B, Palinkas L. Mental health service use among trauma-exposed adults: a mixed-methods study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202:239-46.

-

44Keyser-Marcus L, Alvanzo A, Rieckmann T, Thacker L, Sepulveda A, Forcehimes A, et al. Trauma, gender, and mental health symptoms in individuals with substance use disorders. J Interpers Violence. 2015;30:3-24.

-

45Rossiter A, Byrne F, Wota AP, Nisar Z, Ofuafor T, Murray I, et al. Childhood trauma levels in individuals attending adult mental health services: an evaluation of clinical records and structured measurement of childhood trauma. Child Abus Negl. 2015;44:36-45.

-

46Milam AJ, Furr-Holden CD, Whitaker D, Smart M, Leaf P, Cooley-Strickland M. Neighborhood environment and internalizing problems in African American children. Community Ment Health J. 2012;48:39-44.

-

47Rabinowitz JA, Drabick DA, Reynolds MD. Youth withdrawal moderates the relationhips between neighborhood factors and internalizing symptoms in adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 2016;45:427-39.

-

48Goldner JS, Quimby D, Richards MH, Zakaryan A, Miller S, Dickson D, et al. Relations of parenting to adolescent externalizing and internalizing distress moderated by perception of neighborhood danger. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2016;45:141-54.

-

49White RM, Roosa MW. Neighborhood contexts, fathers, and Mexican American young adolescents' internalizing symptoms. J Marriage Fam. 2012;74:152-66.

-

50Meléndez L. Disease and "broken windows". Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:A657; author reply A657.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

15 Feb 2018 -

Date of issue

Jul-Sep 2018

History

-

Received

26 Sept 2016 -

Accepted

27 June 2017