Abstract

In the last decades the oyster faming stands out as the main mitigating measure to the decline of the fishery, as it presents socio-economic and environmental viability. However, for the success of the activity, it is necessary to understand the stages of cultivation, as well as the growth performance of the species to be cultivated. The present work aims to characterize the growth and survival of Crassostrea tulipa, cultivated on the Amazon coast. For this purpose, oysters were grouped by commercial size class (seed, juvenile, baby, average and masters) and compared the growth rates and their relationships with the abiotic variables. There was no difference in the average growth between the oyster classes, however, when comparing them in the total and percentage growth rates, a higher performance was observed in the oysters classified by juvenile and seed, respectively. The relationship of salinity to oyster growth was evidenced only in the class of juvenile oysters. The cultivation time required to obtain native oysters in the commercial size varied between four and seven months, being inferior to those found in other Brazilian regions.

Keywords:

Amazon region; aquaculture; mollusk; oyster farming; native oyster; Crassostrea tulipa

INTRODUCTION

World production from bivalve mollusk aquaculture plays an important role in human nutrition, and from the 1980s onwards it has grown rapidly until 2014 [11 FAO. Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics. Rome: FAO; 2016.]. This growth in bivalve production is a result, for example, of the success of mussel farming and oyster farming, which appears as a viable alternative to mitigate fishery decline, reducing pressure on natural stocks [22 Montanhini-Neto R, Ostrensky A. Revisão: Uso de modelos matemáticos para avaliação da influência de variáveis ambientais sobre o desenvolvimento de ostras no Brasil. PUBVET. 2012;6(4):1-33.] and becoming a source of income for coastal communities [33 Ostrensky A, Borghetti JR, Soto D. Aqüicultura no Brasil: o desafio é crescer. Brasília: FAO; 2008.

4 Legat AP, Oliveira JAd, Lazoski CVS, Sole-Cava AM, Melo CMR, Galvéz AO. Caracterização genética de ostras nativas do gênero Crassostrea no Brasil: base para o estabelecimento de um programa nacional de melhoramento. Teresina: Embrapa Meio-Norte; 2009.-55 Sampaio DS, Tagliaro CH, Schneider H, Beasley CR. Oyster culture on the Amazon mangrove coast: asymmetries and advances in an emerging sector. Rev Aquac. 2017;11(1):88-104.].

In Brazil, oyster faming is restricted to the cultivation of four oysters of the genus Crassostrea Sacco, 1897: the native oysters Crassostrea tulipa (Lamarck, 1819) (sin. Crassostrea gasar (Deshayes, 1830)), Crassostrea rhizophorae (Guilding, 1828), Crassostrea brasiliana (Lamarck, 1819) and the exotic oyster Crassostrea gigas (Thunberg, 1793) [66 Legat JFA, Puchnick-Legat A, Fogaça FHdS, Tureck CR, Suhnel S, Melo CMRd. Growth and survival of bottom oyster Crassostrea gasar cultured in the northeast and south of Brazil. B. Inst. Pesca. 2017;43(2):172-84.,77 Chagas RA. Biofouling no cultivo da ostra-do-mangue Crassostrea rhizophorae (Guilding, 1828) (Bivalvia: Ostreidae) em um estuário amazônico. Belém, PA: Universidade Federal Rural da Amazônia; 2016.]. However, Brazil is only a producer of Crassostrea sp. oysters because of the taxonomical instability of oysters grown [see 88 Melo MAD, Silva ARB, Beasley CR, Tagliaro CH. Multiplex species-specific PCR identification of native and non-native oysters (Crassostrea) in Brazil: a useful tool for application in oyster culture and stock management. Aquac Int. 2013;21(6):1325-32. and their references].

There are oyster crops throughout the Brazilian coast, however in the North and Northeast regions they are handmade and, in the South and Southeast, industrially [99 Macedo ARG, Silva FL, Ribeiro SCA, Torres MF, Silva FNL, Medeiros LR. Perfil da ostreicultura na comunidade de Santo Antônio do Urindeua, Salinópolis, nordeste do Pará/Brasil. R Obs econ latinoam. 2016; Mar.]. In this scenario, the State of Santa Catarina stands out [22 Montanhini-Neto R, Ostrensky A. Revisão: Uso de modelos matemáticos para avaliação da influência de variáveis ambientais sobre o desenvolvimento de ostras no Brasil. PUBVET. 2012;6(4):1-33., 1010 Maccacchero GB, Ferreira JF, Guzenski J. Influence of stocking density and culture management on growth and mortality of the mangrove native oyster Crassostrea sp. in southern Brazil. Biotemas. 2007;20(3):47-53.], responsible for 97.9% of Brazilian production in 2016 [1111 IBGE. Produção da pecuária municipal 2016. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2017.]. In the same year, oyster faming in the State of Pará presented a productivity of ~ 42 tons, (0.2% of the national production) [1111 IBGE. Produção da pecuária municipal 2016. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2017.].

Success in oyster farming depends heavily on the environmental conditions of the growing area, that is the physical, chemical and biological characteristics of the environment [44 Legat AP, Oliveira JAd, Lazoski CVS, Sole-Cava AM, Melo CMR, Galvéz AO. Caracterização genética de ostras nativas do gênero Crassostrea no Brasil: base para o estabelecimento de um programa nacional de melhoramento. Teresina: Embrapa Meio-Norte; 2009.,77 Chagas RA. Biofouling no cultivo da ostra-do-mangue Crassostrea rhizophorae (Guilding, 1828) (Bivalvia: Ostreidae) em um estuário amazônico. Belém, PA: Universidade Federal Rural da Amazônia; 2016.,1010 Maccacchero GB, Ferreira JF, Guzenski J. Influence of stocking density and culture management on growth and mortality of the mangrove native oyster Crassostrea sp. in southern Brazil. Biotemas. 2007;20(3):47-53.,1212 Azevedo RV, Tonini WCT, Santos MJM, Braga LGT. Biofiltration, growth and body composition of oyster Crassostrea rhizophorae in effluents from shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Rev Ciênc Agron. 2015;46(1):193-203.

13 Manzoni GC, Schimitt JF. Capitulo 17: Cultivo de ostras japonesas Crassostrea gigas (Mollusca: Bivalvia), na Armação do Itapocoroy, Penha, SC. Bases ecológicas para um desenvolvimento sustentável: estudos de caso em Penha, SC. Penha. p. 245-52.

14 Pinto FMVS. Efeito de organismos incrustantes sobre o crescimento e a sobrevivência de ostras nativas do gênero Crassostrea em um cultivo suspenso na Baía de Guaratuba (Paraná – Brasil). Pontal do Paraná: Universidade Federal do Paraná; 2007.

15 Pereira OM, Galvão MSN, Tanji S. Época e método de seleção de sementes de ostra Crassostrea brasiliana (Lamarck, 1819) no complexo estuarino - Laugna de Cananéia, estado de São Paulo (25º S; 048º W). B. Inst. Pesca. 1991;18(único):41-9.

16 Alvarenga L, Nalesso RC. Preliminary assessment of the potential for mangrove oyster cultivation in Piraquê-açu River Estuary (Aracruz, ES). Braz Arch Biol Technol. 2006;49(1):163-9.

17 Chagas RA, Barros MRF, Santos WCR, Herrmann M. Composition of the biofouling community associated with oyster culture in an Amazon estuary, Para state, Northern Brazil. Rev Biol Mar Oceanogr. 2018; 53(1):9-17.

18 Oliveira LFS, Ferreira MAP, Juen L, Nunes ZMP, Pantoja JCD, Paixão LF, Lima MNB, Rocha RM. Influence of the proximity to the ocean and seasonality on the growth performance of farmed mangrove oysters (Crassostrea gasar) in tropical environments. Aquaculture. 2018;496:661-7.-1919 Vale AVP, Santos WCR, Barros MRF, Chagas RA, Herrmann M. Comparação de substratos artificiais na redução de bioincrustantes em um cultivo de ostras no estuário amazônico. Revista CEPSUL. 2020; 9(e2020001):1-16.]. These factors directly influence the growth of the cultivated oyster, and because of this, several studies have been carried out [66 Legat JFA, Puchnick-Legat A, Fogaça FHdS, Tureck CR, Suhnel S, Melo CMRd. Growth and survival of bottom oyster Crassostrea gasar cultured in the northeast and south of Brazil. B. Inst. Pesca. 2017;43(2):172-84.,1212 Azevedo RV, Tonini WCT, Santos MJM, Braga LGT. Biofiltration, growth and body composition of oyster Crassostrea rhizophorae in effluents from shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Rev Ciênc Agron. 2015;46(1):193-203.,1515 Pereira OM, Galvão MSN, Tanji S. Época e método de seleção de sementes de ostra Crassostrea brasiliana (Lamarck, 1819) no complexo estuarino - Laugna de Cananéia, estado de São Paulo (25º S; 048º W). B. Inst. Pesca. 1991;18(único):41-9.,1818 Oliveira LFS, Ferreira MAP, Juen L, Nunes ZMP, Pantoja JCD, Paixão LF, Lima MNB, Rocha RM. Influence of the proximity to the ocean and seasonality on the growth performance of farmed mangrove oysters (Crassostrea gasar) in tropical environments. Aquaculture. 2018;496:661-7.,2020 Pereira OM, Machado IC, Henriques MB, Yamanaka N. Crescimento da ostra Crassostrea brasiliana semeada sobre tabuleiro em diferentes densidades na região estuarino-lagunar de Cananéia-SP (25º s, 48º w). B. Inst. Pesca. 2001;27(2):163-74.

21 Cardoso Júnior LO, Lavander HD, Silva Neto SR, Souza AB, Silva LOB, Gálvez AO. Crescimento da ostra Crassostrea rhizophorae cultivada em diferentes densidades de estocagem no Litoral Norte de Pernambuco. Pesq Agropec Pernamb. 2012;17(único):10-4.

22 Rosa LC. Crescimento e sobrevivência da ostra Crassostrea brasiliana (Lamarck, 1819) mantida em um viveiro de cultivo de camarão. Arq Ciên Mar. 2014;47(1):64-8.

23 Pereira OM, Henriques MB, Machado IC. Estimativa da curva de crescimento da ostra Crassostrea brasiliana em bosques de mangue e proposta para sua extração ordenada no estuário de Cananéia, SP, Brasil. B. Inst. Pesca. 2003;29(1):19-28.

24 Lopes GR, Gomes CHAM, Tureck CR, Melo CMR. Growth of Crassostrea gasar cultured in marine and estuary environments in Brazilian waters. Pesq Agropec Bras. 2013;48(7):975-82.

25 Chagas RA, Herrmann M. Indução a desova de Crassostrea rhizophorae (Guilding, 1828) (Bivalvia: Ostreidae) através de métodos físico-químicos em condições controladas. Acta Fish Aquat Res. 2015;3(2):24-30.-2626 Chagas RA, Silva REO, Passos TAF, Assis AS, Abreu VS, Santos WCR, Barros MRF, Herrmann M. Análise biomorfométrica da ostra-do-mangue cultivada no litoral amazônico. Scientia Plena. 2019;15(10):1-13.].

In this sense, the present work aims to characterize the growth of the C. tulipa mangrove oyster, cultivated in the Amazon coast, and compare it with the performance of oysters grown on the Brazilian coast.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The study site is located in the estuarine zone of the Urindeua river basin, Salinópolis Municipality, State of Pará, Northern Brazil (Figure 1). In “Associação dos Agricultores, Pecuaristas e Aquicultores – ASAPAQ” of the Vila de Santo Antônio de Urindeua the cultivate the oyster C. tulipa, buying the seed at the “Associação de Aquicultores de Vila de Lauro Sodré – AQUAVILA”, located in the Municipality of Curuçá [55 Sampaio DS, Tagliaro CH, Schneider H, Beasley CR. Oyster culture on the Amazon mangrove coast: asymmetries and advances in an emerging sector. Rev Aquac. 2017;11(1):88-104.,99 Macedo ARG, Silva FL, Ribeiro SCA, Torres MF, Silva FNL, Medeiros LR. Perfil da ostreicultura na comunidade de Santo Antônio do Urindeua, Salinópolis, nordeste do Pará/Brasil. R Obs econ latinoam. 2016; Mar.]. According to the authors, the cultivation system used in ASAPAQ is of the fixed table type, using pillows and lanterns. According to oyster farmers, the lanterns are replaced by pillows and bags, mainly because of the amount of predators (e.g., Stramonita brasiliensis) [77 Chagas RA. Biofouling no cultivo da ostra-do-mangue Crassostrea rhizophorae (Guilding, 1828) (Bivalvia: Ostreidae) em um estuário amazônico. Belém, PA: Universidade Federal Rural da Amazônia; 2016.].

Location of the oyster farms of the Association of Farmers, Pecuaristas and Aquicultores - ASAPAQ, located in the Urindeua river, Amazon coast.

In April 2016, for this growth study in oyster C. tulipa cultivated was used 600 oyster of ASAPAQ that was arranged in four lanterns and distributed in commercial size classes (seed: 15 to 29 mm long, juvenile: 30 to 59 mm, baby: 60 to 79 mm, average: 80 to 100 mm, and master:> 100 mm). In the sampling the oyster shells were cleaned, according to Chagas [77 Chagas RA. Biofouling no cultivo da ostra-do-mangue Crassostrea rhizophorae (Guilding, 1828) (Bivalvia: Ostreidae) em um estuário amazônico. Belém, PA: Universidade Federal Rural da Amazônia; 2016.], and the total shell length was measured according to Quayle [2727 Quayle DB. Pacific oyster culture in British Columbia. Canadian Bulletin of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 218. 1988.], using a digital caliper (mark: TESA - Datadirect, accuracy: 0.01 mm).

For characterization of C. tulipa growth, the morphometric data were previously grouped by size classes. From this, the average monthly growth () and total () were estimated according to Equation 1 and 2 below:

Where, Tcm is the average monthly growth rate, Cmt is the total length of each oyster measured in the current month, Cmi is the average of the total length of the oysters at the beginning of the experiment. Tct represents the average rate of total oyster growth at the end of the experiment, Cmf is the mean total length of the oysters measured in the last month and Nmonths the number of months of the experiment.

The survival rate of C. tulipa was estimated by size classes through Equation 3 below:

Where, S is the percentage survival of oysters at the end of the experiment, Nt is the number of surviving individuals and N0 is the initial number of individuals in the experiment.

The Shapiro-Wilk test (p <0.05) was applied to verify the normality of the data. Then, in order to compare the obtained from each class of total oyster length at the end of the study, the analysis of variance (ANOVA one-way) was performed. When differences between the , were found, the means were compared through the Tukey test, at a significance level of 5%.

It was verified the correlation between the abiotic variables (salinity and TSA) and the classes of cultivated oyster. For this, simple regressions were performed between the variables (through Equation 2), with the dependent variable (Y) corresponding to the Tcm per class of oysters and the independent variable (X) being the abiotic factors. The data were log transformed with the intention of reducing the amplitude of variation among the correlated variables. Pearson's correlation coefficients (r) were classified according to the classification proposed by Hopkins [2828 Hopkins WG. Correlation coefficient: a new view of statistics 2000. Available from: http://www.sportsci.org/resource/stats/correl.html

http://www.sportsci.org/resource/stats/c...

].

All statistical analyzes were considered at a significance level of 95% (α = 0.05) [2929 Zar JH. Biostatistical Analysis. 5th ed. New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 2010.], using the software PAST – PAlaeontological STatistics (Version 4.0) [3030 Hammer Ø. PAST - Palaeontological statistics. Version 4.0. Natural History Museum: University of Oslo. 2020.].

At the same time, the abiotic data (salinity and TSA) were measured during the ebb tide in each month, using a manual refractometer and a digital immersion thermometer, respectively. The rainfall data were obtained from the website of the National Water Agency (http://www3.ana.gov.br/).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

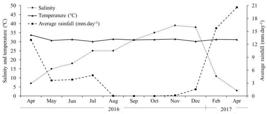

Variability in abiotic data is observed throughout the collection months. The highest variation was observed in the salinity, with a mean of 22.5±12.6 (mean±SD), minimum value of 3 (Apr/16) and maximum of 39 (Nov/16). The temperature presented little variation, with 31.2±0.9ºC, minimum of 30.1ºC (Jul/16) and maximum of 33.7 ºC (April/16). The average monthly rainfall was inversely proportional to salinity, with a mean of 5.8±7.3 mm.day-1, presenting months with no rainfall (Set/16 and Oct/16) and maximum of 20.59 mm. day-1 (Apr/17) (Figure 2).

Variation of salinity and surface water temperature (TSA) during spring tides and monthly average rainfall in ASAPAQ oysters in the Urindeua river, Salinópolis, Pará, between 2016/April and 2017/April.

The temperature is a variable that depends on the time of collection and the seasonal season, however the average surface temperature of the water found in the Urindeua river is in agreement with other rivers in the Amazon [3131 Miranda RG, Pereira SdFP, Alves DTV, Oliveira GRF. Qualidade dos recursos hídricos da Amazônia - Rio Tapajós: avaliação de caso em relação aos elementos químicos e parâmetros físico-químico. Ambi-Agua. 2009;4(2):75-92.]. The salinity rise and rainfall decline is related to the beginning of the less rainy season (dry season), delimited by the authors between June and November.

The monthly morphometric data of C. tulipa are available in Chagas [3232 Chagas RA, Abreu VS, Silva REO, Assis AS, Passos TAF, Barros MRF, Santos WCR, Herrmann M. Morphometric data of Crassostrea tulipa cultivated on the Amazonian coast. PANGAEA - Data Publisher for Earth & Environmental Science. 2018. Available from: https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.890779

https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.8...

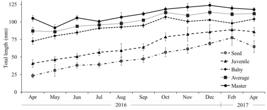

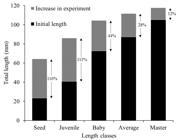

], on the Data Publisher for Earth & Environmental Science - PANGAEA (https://www.pangaea.de/) platform. From these data, oyster growth was observed in all commercial classes, by means of the monthly average lengths measured (Figure 3) and the percentage of growth over the sampled period (Figure 4). Greater performance in the growth of oysters classified by seeds (116%) in the study period.

Mean values of total length of oysters collected monthly in ASAPAQ cultivation in the Urindeua river, Salinópolis, Pará, between April/2016 and April/2017. Error bars (upper and lower) represent the standard deviation of the measured total length averages.

According to the review prepared by Chagas and Herrmann [3333 Chagas RA, Herrmann M. Relative growth of Crassostrea spp. oysters on the Brazilian coast: A review. PANGAEA-Data Publisher for Earth & Environmental Science. 2018. Available from: https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.890027.

https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.8...

], it is observed that 46% of the studies present the juvenile class as minimum size at the beginning of the experiment, 32% with pre-seed, 12% with seed and 10% with baby. Studies that address oyster growth performance in the Brazilian coast compare the average monthly growth without distinction of classes [66 Legat JFA, Puchnick-Legat A, Fogaça FHdS, Tureck CR, Suhnel S, Melo CMRd. Growth and survival of bottom oyster Crassostrea gasar cultured in the northeast and south of Brazil. B. Inst. Pesca. 2017;43(2):172-84.,2222 Rosa LC. Crescimento e sobrevivência da ostra Crassostrea brasiliana (Lamarck, 1819) mantida em um viveiro de cultivo de camarão. Arq Ciên Mar. 2014;47(1):64-8.], which leads to biased or misleading comparisons. As a result, at the standardization level, the performance of oysters grown with studies using equivalent grades was compared.

The commercial size of the oyster is related to the form of consumption, the species and the regional preference [66 Legat JFA, Puchnick-Legat A, Fogaça FHdS, Tureck CR, Suhnel S, Melo CMRd. Growth and survival of bottom oyster Crassostrea gasar cultured in the northeast and south of Brazil. B. Inst. Pesca. 2017;43(2):172-84.]. C. tulipa presents 60 mm as initial commercial size in the State of Pará [55 Sampaio DS, Tagliaro CH, Schneider H, Beasley CR. Oyster culture on the Amazon mangrove coast: asymmetries and advances in an emerging sector. Rev Aquac. 2017;11(1):88-104., 99 Macedo ARG, Silva FL, Ribeiro SCA, Torres MF, Silva FNL, Medeiros LR. Perfil da ostreicultura na comunidade de Santo Antônio do Urindeua, Salinópolis, nordeste do Pará/Brasil. R Obs econ latinoam. 2016; Mar.] and in this study, the oysters classified by seed and juveniles, took, on average, seven and four months, respectively, to reach commercial size (Figure 3).

The oysters classified by seeds presented =5.17±1.42mm (mean ± SD), varying between 3.07 and 7.63 mm, juveniles with =5.03±0.88mm, varying between 3.61 and 6.46mm, baby with =4.19±1.64mm, varying between 2.01 and 7.42mm, average with =4.08±1.80mm, varying between 1.40 and 7.94mm, and master with =6.22±4.10mm, varying between 2.36 and 14.12mm.

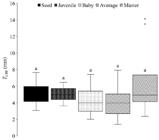

In the first three months of the experiment, there was a greater oscillation in the of the oysters, with emphasis on the oyster masters that showed a sharp decrease in between the months of June and July 2016. The considerable range of of the average oysters between May and June of the same year is highlighted. After July 2016, a balance was observed in the of the oysters, with small variations in the following months. It is noteworthy that juvenile oysters presented the smallest variation in the experiment period (Figure 5).

Variation of the average monthly growth rates (Tcm) in the respective oyster length classes: seed, juvenile, baby, average and master.

According to the ANOVA result, no evidence of significant differences was found (Fc=1.464 < Ft=2.578; p=0.22), accepting the null hypothesis. Therefore, the values of obtained in each class of total length of the oysters at the end of the study do not present differences (Figure 6). This result was also perpetuated in the Tukey test, with no significant differences.

Average monthly growth rates (Tcm) in oyster length classes. Equal letters indicate statistical equality at a significance level of 5%.

According to the classification proposed by Hopkins [2828 Hopkins WG. Correlation coefficient: a new view of statistics 2000. Available from: http://www.sportsci.org/resource/stats/correl.html

http://www.sportsci.org/resource/stats/c...

], from the Pearson correlation coefficient (r), they indicate a low correlation between the of the oyster classes and the monthly TSA (Table 1). When analyzing the of the oysters and the monthly variation of salinity, a correlation classified as “moderate” between the abiotic variable and the seed, baby, average and master classes is verified. The relationship between the juvenile class and the salinity is highlighted, classifying the correlation as “very high” (Table 1). This higher performance of juvenile oysters is evident in Figure 5, where in the months with the highest salinities (October, November and December 2016), the of this class was higher than the others.

Pearson correlation coefficients (r) obtained from the correlations between the size of oysters marketed and the abiotic variables (salinity and TSA) monthly, classifying them in: a=very low, b=low, c=moderate and d=very high.

Legat [66 Legat JFA, Puchnick-Legat A, Fogaça FHdS, Tureck CR, Suhnel S, Melo CMRd. Growth and survival of bottom oyster Crassostrea gasar cultured in the northeast and south of Brazil. B. Inst. Pesca. 2017;43(2):172-84.] reported that C. tulipa oysters presented better growth performance in Santa Catarina, when compared to those grown in the State of Maranhão. However, the growth performance found in this study is well above those found by other authors in the South and Southeast regions (Table 3).

In the Brazilian coastal studies, the oysters classified by pre-seeds had a mean growth rate (Tct) of 6.08±2.65mm (mean ± SD), ranging from 2.53 to 9.96 mm. When comparing the performance of those classified by seeds, it is observed that the average Tct found in this study (Tct=3.41mm) was well below the national average (Tct=5.19±2.74mm). This result is similar to that found by Pereira and Chagas Soares [3434 Pereira OM, Chagas Soares F. Análise da criação de ostra Crassostrea brasiliana (Lamarck, 1819), no sítio Guarapari, na região lagunar-estuarina de Cananéia-SP. B Inst Pesca. 1996;23(único):135-42.], in his experiment with C. brasiliana. A very different result was found when comparing the performance of juveniles and baby, who presented Tct well above the average found in other regions (Tct=2.95±2.24mm and Tct=0.16±0.03mm, respectively). The absence of experiments regarding the growth of average and master oysters and the high number of publications concerning pre-seeds and juveniles, occurs for different reasons. In the case of oysters classified by pre-seeds, it is important to understand their initial development, as well as their relation to environmental parameters. The juveniles, however, represent the most commercialized oyster lengths in Brazil, and because of this, the largest studies are aimed at these length classes.

Survival rates of oysters were high, with oysters classified as baby with a better percentage of survival (~85%) and masters with the lowest percentage (~66%) (Table 2). The survival rates of C. tulipa observed in the experiment period (Table 2) are considered optimal for man-oyster cultivation. The data obtained in other studies with the same cultivation period corroborate this assertion Legat [66 Legat JFA, Puchnick-Legat A, Fogaça FHdS, Tureck CR, Suhnel S, Melo CMRd. Growth and survival of bottom oyster Crassostrea gasar cultured in the northeast and south of Brazil. B. Inst. Pesca. 2017;43(2):172-84.] observed a superior survival rate (> 87% and 91%, respectively) to that found in this study (between 66 and 85%) in their experiment with C. tulipa, in the states of Maranhão and Santa Catarina. Oliveira [3535 Oliveira NL. Avaliação do crescimento da ostra nativa Crassostrea (Sacco, 1897) cultivada em estruturas de sistemas fixos nas localidades de Ponta Grossa (município de Vera Cruz) e Iguape (município de Cachoeira), região do Recôncavo, na Baía de Todos os Santos, Bahia. Cruz das Almas: Universidade Federal do Recôncavo da Bahia; 2014.] has survived between 73 and 80% of the C. brasiliana oyster and between 87 and 94% of C. rhizophorae, both cultivated in the state of Bahia. However, using the same culture period, other studies have a low survival, such as ~ 30% [3434 Pereira OM, Chagas Soares F. Análise da criação de ostra Crassostrea brasiliana (Lamarck, 1819), no sítio Guarapari, na região lagunar-estuarina de Cananéia-SP. B Inst Pesca. 1996;23(único):135-42.] and ~50% [3636 Pereira OM, Akaboshi S, Chagas Soares F. Cultivo experimental de Crassostrea brasiliana (Lamarck, 1819) no canal da Bertioga, São Paulo, Brasil (23°54'30”S, 45°13'42”W). B Inst Pesca. 1988;15(1):55-65.], both using the C. brasiliana oyster in the state of São Paulo, and survival of 40% found in C. gigas culture in Santa Catarina [1313 Manzoni GC, Schimitt JF. Capitulo 17: Cultivo de ostras japonesas Crassostrea gigas (Mollusca: Bivalvia), na Armação do Itapocoroy, Penha, SC. Bases ecológicas para um desenvolvimento sustentável: estudos de caso em Penha, SC. Penha. p. 245-52.].

Performance of oysters of the genus Crassostrea in different crops in the Brazilian coast, presenting values of initial length (C0), final length (Cf), growing period (T) in the month, average monthly growth rate (Tct) and percentage survival (S). Legend: Oysters sorted by semente (a), juvenile (b), baby (c), average (d) e master (e). Updated taxonomy of Crassostrea gasar (*) and values not available (**). Source: Chagas and Herrmann [3333 Chagas RA, Herrmann M. Relative growth of Crassostrea spp. oysters on the Brazilian coast: A review. PANGAEA-Data Publisher for Earth & Environmental Science. 2018. Available from: https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.890027.

https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.8... ].

On the other hand, some studies, using a shorter cultivation period, present a high survival rate of Crassostrea oysters on the Brazilian coast. Among these studies, we highlight ~ 90% survival, in ten months of cultivation of C. brasiliana, in São Paulo [2020 Pereira OM, Machado IC, Henriques MB, Yamanaka N. Crescimento da ostra Crassostrea brasiliana semeada sobre tabuleiro em diferentes densidades na região estuarino-lagunar de Cananéia-SP (25º s, 48º w). B. Inst. Pesca. 2001;27(2):163-74.], ~88% in four months of cultivation in Paraná [1414 Pinto FMVS. Efeito de organismos incrustantes sobre o crescimento e a sobrevivência de ostras nativas do gênero Crassostrea em um cultivo suspenso na Baía de Guaratuba (Paraná – Brasil). Pontal do Paraná: Universidade Federal do Paraná; 2007.] and ~93% in five months of cultivation in Santa Catarina [1010 Maccacchero GB, Ferreira JF, Guzenski J. Influence of stocking density and culture management on growth and mortality of the mangrove native oyster Crassostrea sp. in southern Brazil. Biotemas. 2007;20(3):47-53.], both using Crassostrea sp. in their experiments.

According to Gosling [4242 Gosling E. Marine Bivalve Molluscs. 2 nd. ed: John Wiley & Sons, 2015.], several factors are related to the growth of bivalve mollusks, however the synergy between them makes it difficult to estimate the effect of an isolated factor. Pereira [2020 Pereira OM, Machado IC, Henriques MB, Yamanaka N. Crescimento da ostra Crassostrea brasiliana semeada sobre tabuleiro em diferentes densidades na região estuarino-lagunar de Cananéia-SP (25º s, 48º w). B. Inst. Pesca. 2001;27(2):163-74.] cite that oyster growth and survival rates are directly influenced by biotic and abiotic factors (e.g., salinity, tidal amplitude, primary production, cropping systems). This assertion is corroborated by several authors [66 Legat JFA, Puchnick-Legat A, Fogaça FHdS, Tureck CR, Suhnel S, Melo CMRd. Growth and survival of bottom oyster Crassostrea gasar cultured in the northeast and south of Brazil. B. Inst. Pesca. 2017;43(2):172-84.,1010 Maccacchero GB, Ferreira JF, Guzenski J. Influence of stocking density and culture management on growth and mortality of the mangrove native oyster Crassostrea sp. in southern Brazil. Biotemas. 2007;20(3):47-53.,1313 Manzoni GC, Schimitt JF. Capitulo 17: Cultivo de ostras japonesas Crassostrea gigas (Mollusca: Bivalvia), na Armação do Itapocoroy, Penha, SC. Bases ecológicas para um desenvolvimento sustentável: estudos de caso em Penha, SC. Penha. p. 245-52.,2121 Cardoso Júnior LO, Lavander HD, Silva Neto SR, Souza AB, Silva LOB, Gálvez AO. Crescimento da ostra Crassostrea rhizophorae cultivada em diferentes densidades de estocagem no Litoral Norte de Pernambuco. Pesq Agropec Pernamb. 2012;17(único):10-4.,2222 Rosa LC. Crescimento e sobrevivência da ostra Crassostrea brasiliana (Lamarck, 1819) mantida em um viveiro de cultivo de camarão. Arq Ciên Mar. 2014;47(1):64-8.,3535 Oliveira NL. Avaliação do crescimento da ostra nativa Crassostrea (Sacco, 1897) cultivada em estruturas de sistemas fixos nas localidades de Ponta Grossa (município de Vera Cruz) e Iguape (município de Cachoeira), região do Recôncavo, na Baía de Todos os Santos, Bahia. Cruz das Almas: Universidade Federal do Recôncavo da Bahia; 2014.,3737 Maccacchero GB, Guzenski J, Ferreira JF. Allometric growth on mangrove oyster Crassostrea rhizophorae (Guilding, 1828), cultured in Southern Brazil. Rev Cienc Agron. 2005;36(3):400-3.,3939 Vilar TC. Crescimento da ostra-do-mangue Crassostrea rhizophorae (Guilding, 1828) cultivada em Barra de São Miguel, Alagoas, Brasil. Recife - PE: Universidade Federal de Pernambuco; 2012.].

For a precise estimation of the growth rates of the cultured oyster in a tropic climatic area, Chagas and Herrmann [4343 Chagas RA, Herrmann M. Estimativas de crescimento de bivalves tropicais e subtropicais: recomendação para um método padronizado. Acta Fish Aquat Res. 2016; 4(2):28-38.] recommend a marking-recapture experiment, using the in situ fluorescent labeling method (the calcein solution base) and sizes. This method is effective because it presents excellent markers and does not negatively influence the survival of tagged individuals [4343 Chagas RA, Herrmann M. Estimativas de crescimento de bivalves tropicais e subtropicais: recomendação para um método padronizado. Acta Fish Aquat Res. 2016; 4(2):28-38.

44 Herrmann M, Carstensen D, Fischer S, Laudien J, Penchaszadeh PE, Arntz WE. Population structure, growth and production of the wedge clam Donax hanleyanus (Bivalvia: Donacidae) from northern Argentinean beaches. J Shellfish Res. 2009; 28(3):511-26.

45 Herrmann M, Lepore ML, Laudien J, Arntz WE, Penchaszadeh PE. Growth estimations of the Argentinean wedge clam Donax hanleyanus: A comparison between length-frequency distribution and size-increment analysis. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2009; 379(1-2):8-15.

46 Lepore ML, Penchaszadeh PE, Alfaya JEF, Herrmann M. Aplicación de calceína para la estimación del crecimiento de la almeja amarilla Mesodesma mactroides Reeve, 1854. Rev Biol Mar Oceanogr. 2009;44(3):767-74.-4747 Herrmann M. A aptidão de calceína como mrcador de crescimento in situ nas ostras cultivadas e nativas em regiões subtropicais e tropicais do Brasil. In: Souza RAL (org.). Ecossistemas aquáticos: Tópicos especiais. Belém: Edufra; 2018. p. 239-46.].

CONCLUSION

The variability in the growth rates of the Crassotrea tulipa oysters in the first months of the crop evidences a stress to the environmental conditions. However, from the minimization of this stress (occurring in the third month of cultivation), the equilibrium of the growth rates occurs. It is concluded, through the statistical analysis, that there is no difference between oyster growth rates at the end of the experiment, however, there are differences in total and percentage growth rates, especially oysters classified by juveniles and seeds, respectively. The salinity influenced only the growth of juvenile oysters, mainly because these oysters presented the highest monthly growth rates in the months where it showed the highest salinity values. The survival rates of oysters in this study were satisfactory and correlated to those found in other studies in the Brazilian coast.

In this study, the period of oyster cultivation to reach commercial size was shorter (four to seven months) than in other regions (e.g., south and southeast), even when compared to the same species.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank the “Associação dos Agricultores, Pecuaristas e Aquicultores – ASAPAQ” of the Vila de Santo Antônio de Urindeua for the support to the development of the research. In particular the oyster farming: Dona Maria (current president), Tito, Miro and his Antônio (former president). The Federal Rural University of Amazon (UFRA), especially to the Socioenvironmental and Water Resources Institute (ISARH/UFRA), for the logistical support in the assignment of transportation to the authors' displacement to the research site.

-

HIGHLIGHTS

-

• Total and percentage growth rates, higher performance was observed in the oysters classified by juvenile and seed, respectively.

-

• The relationship of salinity to oyster growth was evidenced only in the class of juvenile oysters.

-

• The cultivation time required to obtain native oysters in the commercial size varied between four and seven months.

-

Funding: To the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), for granting scholarships to carry out this research.

REFERENCES

-

1FAO. Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics. Rome: FAO; 2016.

-

2Montanhini-Neto R, Ostrensky A. Revisão: Uso de modelos matemáticos para avaliação da influência de variáveis ambientais sobre o desenvolvimento de ostras no Brasil. PUBVET. 2012;6(4):1-33.

-

3Ostrensky A, Borghetti JR, Soto D. Aqüicultura no Brasil: o desafio é crescer. Brasília: FAO; 2008.

-

4Legat AP, Oliveira JAd, Lazoski CVS, Sole-Cava AM, Melo CMR, Galvéz AO. Caracterização genética de ostras nativas do gênero Crassostrea no Brasil: base para o estabelecimento de um programa nacional de melhoramento. Teresina: Embrapa Meio-Norte; 2009.

-

5Sampaio DS, Tagliaro CH, Schneider H, Beasley CR. Oyster culture on the Amazon mangrove coast: asymmetries and advances in an emerging sector. Rev Aquac. 2017;11(1):88-104.

-

6Legat JFA, Puchnick-Legat A, Fogaça FHdS, Tureck CR, Suhnel S, Melo CMRd. Growth and survival of bottom oyster Crassostrea gasar cultured in the northeast and south of Brazil. B. Inst. Pesca. 2017;43(2):172-84.

-

7Chagas RA. Biofouling no cultivo da ostra-do-mangue Crassostrea rhizophorae (Guilding, 1828) (Bivalvia: Ostreidae) em um estuário amazônico. Belém, PA: Universidade Federal Rural da Amazônia; 2016.

-

8Melo MAD, Silva ARB, Beasley CR, Tagliaro CH. Multiplex species-specific PCR identification of native and non-native oysters (Crassostrea) in Brazil: a useful tool for application in oyster culture and stock management. Aquac Int. 2013;21(6):1325-32.

-

9Macedo ARG, Silva FL, Ribeiro SCA, Torres MF, Silva FNL, Medeiros LR. Perfil da ostreicultura na comunidade de Santo Antônio do Urindeua, Salinópolis, nordeste do Pará/Brasil. R Obs econ latinoam. 2016; Mar.

-

10Maccacchero GB, Ferreira JF, Guzenski J. Influence of stocking density and culture management on growth and mortality of the mangrove native oyster Crassostrea sp. in southern Brazil. Biotemas. 2007;20(3):47-53.

-

11IBGE. Produção da pecuária municipal 2016. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2017.

-

12Azevedo RV, Tonini WCT, Santos MJM, Braga LGT. Biofiltration, growth and body composition of oyster Crassostrea rhizophorae in effluents from shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei Rev Ciênc Agron. 2015;46(1):193-203.

-

13Manzoni GC, Schimitt JF. Capitulo 17: Cultivo de ostras japonesas Crassostrea gigas (Mollusca: Bivalvia), na Armação do Itapocoroy, Penha, SC. Bases ecológicas para um desenvolvimento sustentável: estudos de caso em Penha, SC. Penha. p. 245-52.

-

14Pinto FMVS. Efeito de organismos incrustantes sobre o crescimento e a sobrevivência de ostras nativas do gênero Crassostrea em um cultivo suspenso na Baía de Guaratuba (Paraná – Brasil). Pontal do Paraná: Universidade Federal do Paraná; 2007.

-

15Pereira OM, Galvão MSN, Tanji S. Época e método de seleção de sementes de ostra Crassostrea brasiliana (Lamarck, 1819) no complexo estuarino - Laugna de Cananéia, estado de São Paulo (25º S; 048º W). B. Inst. Pesca. 1991;18(único):41-9.

-

16Alvarenga L, Nalesso RC. Preliminary assessment of the potential for mangrove oyster cultivation in Piraquê-açu River Estuary (Aracruz, ES). Braz Arch Biol Technol. 2006;49(1):163-9.

-

17Chagas RA, Barros MRF, Santos WCR, Herrmann M. Composition of the biofouling community associated with oyster culture in an Amazon estuary, Para state, Northern Brazil. Rev Biol Mar Oceanogr. 2018; 53(1):9-17.

-

18Oliveira LFS, Ferreira MAP, Juen L, Nunes ZMP, Pantoja JCD, Paixão LF, Lima MNB, Rocha RM. Influence of the proximity to the ocean and seasonality on the growth performance of farmed mangrove oysters (Crassostrea gasar) in tropical environments. Aquaculture. 2018;496:661-7.

-

19Vale AVP, Santos WCR, Barros MRF, Chagas RA, Herrmann M. Comparação de substratos artificiais na redução de bioincrustantes em um cultivo de ostras no estuário amazônico. Revista CEPSUL. 2020; 9(e2020001):1-16.

-

20Pereira OM, Machado IC, Henriques MB, Yamanaka N. Crescimento da ostra Crassostrea brasiliana semeada sobre tabuleiro em diferentes densidades na região estuarino-lagunar de Cananéia-SP (25º s, 48º w). B. Inst. Pesca. 2001;27(2):163-74.

-

21Cardoso Júnior LO, Lavander HD, Silva Neto SR, Souza AB, Silva LOB, Gálvez AO. Crescimento da ostra Crassostrea rhizophorae cultivada em diferentes densidades de estocagem no Litoral Norte de Pernambuco. Pesq Agropec Pernamb. 2012;17(único):10-4.

-

22Rosa LC. Crescimento e sobrevivência da ostra Crassostrea brasiliana (Lamarck, 1819) mantida em um viveiro de cultivo de camarão. Arq Ciên Mar. 2014;47(1):64-8.

-

23Pereira OM, Henriques MB, Machado IC. Estimativa da curva de crescimento da ostra Crassostrea brasiliana em bosques de mangue e proposta para sua extração ordenada no estuário de Cananéia, SP, Brasil. B. Inst. Pesca. 2003;29(1):19-28.

-

24Lopes GR, Gomes CHAM, Tureck CR, Melo CMR. Growth of Crassostrea gasar cultured in marine and estuary environments in Brazilian waters. Pesq Agropec Bras. 2013;48(7):975-82.

-

25Chagas RA, Herrmann M. Indução a desova de Crassostrea rhizophorae (Guilding, 1828) (Bivalvia: Ostreidae) através de métodos físico-químicos em condições controladas. Acta Fish Aquat Res. 2015;3(2):24-30.

-

26Chagas RA, Silva REO, Passos TAF, Assis AS, Abreu VS, Santos WCR, Barros MRF, Herrmann M. Análise biomorfométrica da ostra-do-mangue cultivada no litoral amazônico. Scientia Plena. 2019;15(10):1-13.

-

27Quayle DB. Pacific oyster culture in British Columbia. Canadian Bulletin of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 218. 1988.

-

28Hopkins WG. Correlation coefficient: a new view of statistics 2000. Available from: http://www.sportsci.org/resource/stats/correl.html

» http://www.sportsci.org/resource/stats/correl.html -

29Zar JH. Biostatistical Analysis. 5th ed. New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 2010.

-

30Hammer Ø. PAST - Palaeontological statistics. Version 4.0. Natural History Museum: University of Oslo. 2020.

-

31Miranda RG, Pereira SdFP, Alves DTV, Oliveira GRF. Qualidade dos recursos hídricos da Amazônia - Rio Tapajós: avaliação de caso em relação aos elementos químicos e parâmetros físico-químico. Ambi-Agua. 2009;4(2):75-92.

-

32Chagas RA, Abreu VS, Silva REO, Assis AS, Passos TAF, Barros MRF, Santos WCR, Herrmann M. Morphometric data of Crassostrea tulipa cultivated on the Amazonian coast. PANGAEA - Data Publisher for Earth & Environmental Science. 2018. Available from: https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.890779

» https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.890779 -

33Chagas RA, Herrmann M. Relative growth of Crassostrea spp. oysters on the Brazilian coast: A review. PANGAEA-Data Publisher for Earth & Environmental Science. 2018. Available from: https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.890027

» https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.890027 -

34Pereira OM, Chagas Soares F. Análise da criação de ostra Crassostrea brasiliana (Lamarck, 1819), no sítio Guarapari, na região lagunar-estuarina de Cananéia-SP. B Inst Pesca. 1996;23(único):135-42.

-

35Oliveira NL. Avaliação do crescimento da ostra nativa Crassostrea (Sacco, 1897) cultivada em estruturas de sistemas fixos nas localidades de Ponta Grossa (município de Vera Cruz) e Iguape (município de Cachoeira), região do Recôncavo, na Baía de Todos os Santos, Bahia. Cruz das Almas: Universidade Federal do Recôncavo da Bahia; 2014.

-

36Pereira OM, Akaboshi S, Chagas Soares F. Cultivo experimental de Crassostrea brasiliana (Lamarck, 1819) no canal da Bertioga, São Paulo, Brasil (23°54'30”S, 45°13'42”W). B Inst Pesca. 1988;15(1):55-65.

-

37Maccacchero GB, Guzenski J, Ferreira JF. Allometric growth on mangrove oyster Crassostrea rhizophorae (Guilding, 1828), cultured in Southern Brazil. Rev Cienc Agron. 2005;36(3):400-3.

-

38Modesto GA, Maia EP, Olivera A, Brito LO. Utilização de Crassostrea rhizophorae (Guilding 1828) no tratamento dos efluentes do cultivo de Litopenaeus vannamei (Boone 1931). PanamJAS. 2010; 5(3):367-75.

-

39Vilar TC. Crescimento da ostra-do-mangue Crassostrea rhizophorae (Guilding, 1828) cultivada em Barra de São Miguel, Alagoas, Brasil. Recife - PE: Universidade Federal de Pernambuco; 2012.

-

40Nascimento IA. Crassostrea rhizophorae (Guilding) and C. brasiliana (Lamarck) in South and Central America. In: Menzel W, editor. Estuarine and marine bivalve mollusk culture. Boston: CRC Press; 1991. p. 125-34.

-

41Akaboshi S. Notas sobre o comportamento da ostra japonesa, Crassostrea gigas (Thunberg, 1795), no litoral do estado do São Paulo, Brasil. B Inst Pesca. 1979; 6(único):93-104.

-

42Gosling E. Marine Bivalve Molluscs. 2 nd. ed: John Wiley & Sons, 2015.

-

43Chagas RA, Herrmann M. Estimativas de crescimento de bivalves tropicais e subtropicais: recomendação para um método padronizado. Acta Fish Aquat Res. 2016; 4(2):28-38.

-

44Herrmann M, Carstensen D, Fischer S, Laudien J, Penchaszadeh PE, Arntz WE. Population structure, growth and production of the wedge clam Donax hanleyanus (Bivalvia: Donacidae) from northern Argentinean beaches. J Shellfish Res. 2009; 28(3):511-26.

-

45Herrmann M, Lepore ML, Laudien J, Arntz WE, Penchaszadeh PE. Growth estimations of the Argentinean wedge clam Donax hanleyanus: A comparison between length-frequency distribution and size-increment analysis. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2009; 379(1-2):8-15.

-

46Lepore ML, Penchaszadeh PE, Alfaya JEF, Herrmann M. Aplicación de calceína para la estimación del crecimiento de la almeja amarilla Mesodesma mactroides Reeve, 1854. Rev Biol Mar Oceanogr. 2009;44(3):767-74.

-

47Herrmann M. A aptidão de calceína como mrcador de crescimento in situ nas ostras cultivadas e nativas em regiões subtropicais e tropicais do Brasil. In: Souza RAL (org.). Ecossistemas aquáticos: Tópicos especiais. Belém: Edufra; 2018. p. 239-46.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

24 May 2021 -

Date of issue

2021

History

-

Received

28 Oct 2019 -

Accepted

10 Sept 2020