Abstracts

This study aimed to identify differences in wing shape among populations of Melipona quadrifasciata anthidioides obtained in 23 locations in the semi-arid region of Bahia state (Brazil). Analysis of the Procrustes distances among mean wing shapes indicated that population structure did not determine shape variation. Instead, populations were structured geographically according to wing size. The Partial Mantel Test between morphometric (shape and size) distance matrices and altitude, taking geographic distances into account, was used for a more detailed understanding of size and shape determinants. A partial Mantel test between morphometris (shape and size) variation and altitude, taking geographic distances into account, revealed that size (but not shape) is largely influenced by altitude (r = 0.54 p < 0.01). These results indicate greater evolutionary constraints for the shape variation, which must be directly associated with aerodynamic issues in this structure. The size, however, indicates that the bees tend to have larger wings in populations located at higher altitudes.

stingless bee; Meliponini; altitude; partial correlation; geometric morphometrics

Este trabalho avaliou a divergência de forma entre populações de Melipona quadrifasciata anthidioides, utilizando caracteres morfométricos em 23 localidades da região semi-árida do estado da Bahia (Brasil). As análises das distâncias de Procrustes entre as formas médias das asas indicaram que não há estruturação populacional para a variação dessa estrutura. Entretanto, nossas análises demonstraram que as populações estavam estruturadas geograficamente pelo tamanho das asas. O teste parcial de Mantel entre matrizes de distâncias morfométricas (forma e tamanho) e altitude, levando em conta as distâncias geográficas, foi utilizado para uma compreensão mais detalhada dos determinantes de tamanho e forma. O teste de Mantel entre as variações morfométricas (forma e tamanho) e altitude, tendo em conta as distâncias geográficas, revelou que o tamanho (mas não a forma) é amplamente influenciado pela altitude (r = 0,54 p < 0,01). Tais resultados indicam maiores restrições evolutivas para a variação de forma, o que deve estar diretamente associado às questões aerodinâmicas dessa estrutura. O tamanho, por outro lado, indica que as abelhas estudadas tendem a apresentar asas maiores nas populações localizadas em regiões de maior altitude.

abelhas sem ferrão; altitude; correlação parcial; Meliponini; morfometria geométrica

Introduction

Morphometric analyses have been used to study patterns of geographic variation and intraspecific differentiation among bees (Diniz-Filho et al., 2000DINIZ-FILHO, JAF., HEPBURN, HR., RADLOFF, S. and FUCHS, S., 2000. Spatial analysis of morphological variation in African honeybees (Apis mellifera L.) on a continental scale. Apidologie, vol. 31, p. 191-204.; Batalha-Filho et al., 2006; Mendes et al., 2007MENDES, MFM., FRANCOY, TM., NUNES-SILVA, P., MENEZES, C. and IMPERATRIZ-FONSECA, VL., 2007. Intra-populational variability of Nannotrigona testaceicornis Lepeletier 1836 (Hymenoptera, Meliponini) using relative warp analysis. Bioscience journal, vol. 23, p. 147-152.; Rattanawannee et al., 2012RATTANAWANNEE, A., CHANCHAO, C. and WONGSIRI, S., 2012. Geometric morphometric analysis of giant honeybee (Apis dorsata Fabricius, 1793) populations in Thailand. Journal of Asia-Pacific Entomology, vol. 15, p. 611-618). The shape of a biologic structure is determined by procedures occurring at different magnitudes and organisational levels of complexity. Therefore, the macroscopic phenotype of a biologic structure is the result of interactions between morphogenetic rules and external mechanisms related to ecological phenomena, as well as other complex stochastic and/or determining evolutionary forces (Levin, 1992).

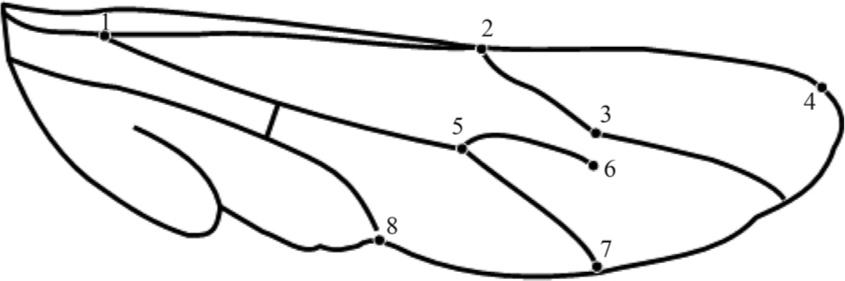

Geometric morphometrics is a suitable, fast and low-cost technique for analysing size and shape variation of organisms, and the anatomic markers help to identify shape variations among homologue morphological structures in different organisms (Francoy and Imperatiz-Fonseca, 2010). The flat insect wings can reveal much information on wing shape and allow for the insertion of various anatomic markers formed mainly in nervure intersections (Grodnitsky, 1999GRODNITSKY, DL., 1999. Form and Function of Insect Wings. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. 261p.).

Plenty of studies with morphometry have been carried out using bee wings, especially for the evaluation of populational structures among the species occurring in Brazil (Nunes et al., 2007NUNES, LA., COSTA-PINTO, MFF., CARNEIRO, PLS., PEREIRA, DG. and WALDSCHMIDT, AM., 2007. Divergência Genética em Melipona scutellaris Latreille (Hymenoptera: Apidae) com base em Caracteres Morfológicos. Bioscience Journal, vol. 23, p. 1-9.; Nunes et al., 2008NUNES, LA., ARAUJO, ED., CARVALHO, CAL. and WALDSCHMIDT, AM., 2008. Population Divergence of Melipona quadrifasciata anthidioides (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Endemic to the Semi-arid Region of the State of Bahia, Brazil. Sociobiology, vol. 52, p. 81-93.; Francoy et al., 2011FRANCOY, TM., GRASSI, ML., IMPERATRIZ-FONSECA, VL., MAY-ITZÁ, WJ. and QUEZADA-EUÁN, JJG., 2011. Geometric Morphometrics of the wing as a tool for assigning genetic lineages and geografic origin to Melipona beecheii (Hymenoptera: Meliponina). Apidologie, vol. 42, p. 499-507.). The Melipona quadrifasciata Lep., known as ‘mandaçaia’ is a well-studied stingless bee species found along the Brazilian coast, from the northeastern Paraíba state to the southern Rio Grande do Sul state (Moure and Kerr 1950MOURE, JS. and KERR, WE., 1950. Sugestões para modificação da sistemática do gênero Melipona (Hymenoptera, Apoidea). Dusenia, vol. 18, p. 105-29.; Nunes et al., 2008NUNES, LA., ARAUJO, ED., CARVALHO, CAL. and WALDSCHMIDT, AM., 2008. Population Divergence of Melipona quadrifasciata anthidioides (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Endemic to the Semi-arid Region of the State of Bahia, Brazil. Sociobiology, vol. 52, p. 81-93.). This bee species is considered suitable for rational keeping primarily due to traits such as being easy to rear, being widely spread in the country, and for producing a nicely-flavoured honey (Monteiro, 2000MONTEIRO, WR., 2000. Meliponicultura: A Mandaçaia (Melipona quadrifasciata). Mensagem Doce, vol. 57.). Melipona quadrifasciata Lep. has two subspecies, M. quadrifasciata quadrifasciata and M. quadrifasciata anthidioides, widely known for their morphology of tergal bands (yellow stripes in the abdomen) (Moreto and Arias, 2005MORETO, G. and ARIAS, MC., 2005. Detection of mitochondrial DNA restriction site differences between the subspecies of Melipona quadrifasciata Lepeletier (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Meliponini). Neotropical Entomology, vol. 34, p. 381-385.). Workers and males of M. quadrifasciata quadrifasciata have yellow and continuous tergal bands, three to five of them located in the third through the sixth segments. Workers and males of M. quadrifasciata anthidioides have two to five discontinued bands (Schwarz, 1948SCHWARZ, H., 1948. Stingless bees (Meliponidae) of the Western Hemisphere. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, vol. 90, p. 1-167.). The latter is found in the cooler and usually higher locations in the semi-arid Bahia state.

Because M. quadrifasciata has an important ecological and economical role in different Brazilian states, this species was chosen for this study as part of continuous research for preservation of endemic species. The aim of this study was to identify a spatial structure for wing shapes based on geometric morphometrics among worker bees Melipona quadrifasciata anthidioides Lep. in the semi-arid region, identifying potential evolutionary units inside the group and allowing a better understanding of the processes driving population differentiation.

2.Material and Methods

Samples of M. quadrifasciata anthidioides were collected from local populations in 23 municipalities in the semi-arid Bahia state (Figure 1). The samples were collected from 3 colonies at each location, with the exception of 3 cities (i.e, due to the lack of other colonies, only 2 samples were obtained for these 3 locations). The right rear and forewings of 10 workers from each of the 66 colonies were analysed.

Location of municipalities in semi-arid Bahia state, Brazil, where specimens of Melipona quadrifasciata anthidioides were collected. (Map adapted from SEI (Superintendência de Estudos Econômicos e Sociais da Bahia).

From the images obtained from pollen basket and wings, anatomic dotes were

made using the Tpsdig2 (Rohlf,

2006ROHLF, FJ., 2006. TPSDIG2 for Windows version 2.10. Available from:

http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/index.html. Accessed in

July 20, 2008.

http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/index.h...

), as shown in the Figures 2

and 3 outline. The cartesian coordinates were

given by the anatomic marks of each sampling group. These lined-up coordinates were

used as shape variables imported to MorphoJ (Klingenberg, 2010), and the

orthogonal superposition was conducted using Procrustes superposition. The technique

used for superposition minimises the sum of square distances between homologue

anatomic markers by means of parameters that rotate, translate and create

proportions in configurations. The resulting coordinates led to the mean shape of

each sample unit.

After the software adjusted for size, position and orientation we calculated the Procrustes and the Mahalanobis distances, and performed a Canonical Variate Analysis among the local populations, analysing the multivariate scores from CVA (the canonical variables). Then a cross-validation was performed to check the consistency of the data and confirm if each individual studied belonged to the group previously determined by CVA. The PAST software was used for the UPGMA cluster analysis.

After these analyses, four triangular matrices were generated for the exploratory analysis of population variation in M. quadrifasciata anthidioides: shape distance (Procrustes), geographic distance, altitude, and distance matrix for size (Mahalanobis). We applied the Mantel Test for partial correlation with the NTSYSpc software with 5,000 permutations. The purpose was to identify associations among those variables, including the single correlation between matrix pairs and the more complex correlation effects involving three simultaneous factors.

3.Results

According to the forewing data analysed using the Analysis of Canonical Variables (ACV), no significant structuring differences among colonies of different sites were observed and the first eight variables were needed to explain more than 80% variation.

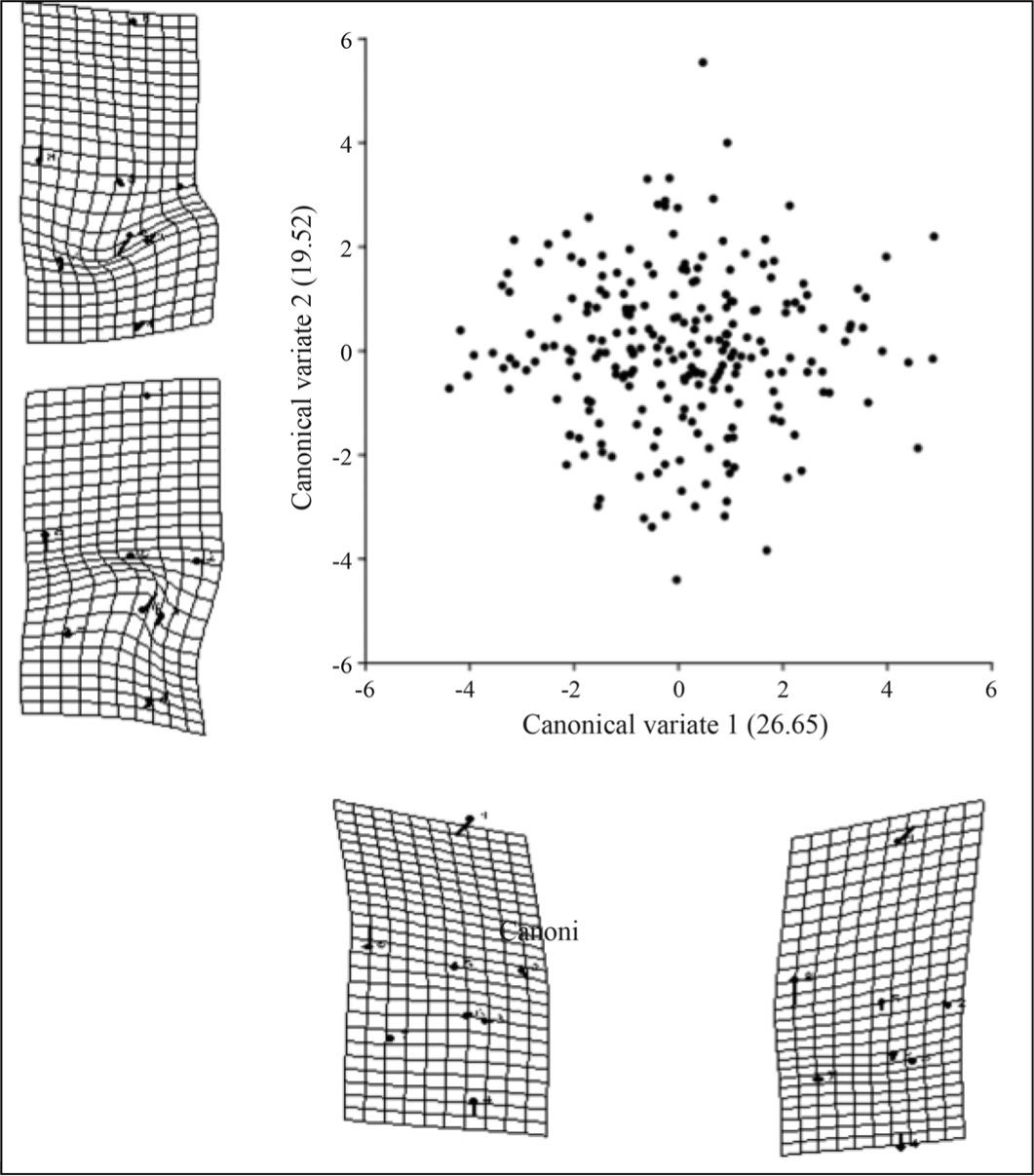

Mantel's correlation showed that wing shape was not determined by geographic distribution patterns. The dispersion diagram displays wing shapes with two uniform components and two relative deformations (Figures 4 and 5).

Dispersion and deformation diagrams of forewings of Melipona quadrifasciataanthidioides in the bidimensional spaces created after the analysis of positional coordinates in a Cartesian plan with 11 anatomic markers.

Dispersion and deformation diagrams of hind wings in Melipona quadrifasciataanthidioides in the bidimensional space created after the analysis of positional coordinates in Cartesian plan with 9 anatomic markers.

The forewing data were cross-validated to classify the individuals reaching 43% within each group. This percentage was expected because differences among colonies were not significant and variations in wing shape occurred by chance. Only the Itiruçu colony had 100% cross-validation in the classification of individuals. This population might be in a process of geographical isolation from other individuals.

Results for forewings and rear wings were similar. The dispersion graphs for individuals in the space determined by two axes for relative deformation I and II, using the first and the second canonical variables (Figures 4 and 5). Although these two variables explained only 46.09% of the variation, they were used to provide a better visualisation and understanding of the results. It shows that M. quadrifasciata anthidioides did not cluster in different groups. Diagrams for relative deformations located around the dispersion graphs were also created and show wing shapes of individuals.

Analysis of the dispersion diagrams revealed no differences related to position of the anatomic markers responsible for the discrimination of population samples. The cross-validation of rear wing data showed 54% of the individuals properly classified in their respective sites.

Although shape was not geographically structured (p > 0.01), the Procrustes ANOVA showed significant differences in size (p < 0.001). The conclusion that wing size varies geographically was based on centroid size, due to centroid size being the only size variable that does not correlate to shape, thereby justifying the use of centroid size as the standard size variable in all the geometric analyses, rather than other variables (Bookstein, 1991BOOKSTEIN, FL., 1991. Morphometric Tools for Landmark Data. Geometry and Biology. New York: Cambridge University Press.). The forewings of M. quadrifasciata anthidioides are smaller in Iaçú and wing size varied more importantly within the colony. In Tanhaçú, rear wings were smaller and sizes were more variable within the colony (Figures 6 and 7).

Rear and forewings were not correlated (p > 0.05), that is, wing shape did not contribute for group formation nor differentiation among populations of M. quadrifasciata anthidioides. The correlation between geographic distribution and altitude was weak and did not significantly impact group formation (Table 1). Although previous studies reported important geographical distribution of bees according to body size (Nunes et al., 2007NUNES, LA., COSTA-PINTO, MFF., CARNEIRO, PLS., PEREIRA, DG. and WALDSCHMIDT, AM., 2007. Divergência Genética em Melipona scutellaris Latreille (Hymenoptera: Apidae) com base em Caracteres Morfológicos. Bioscience Journal, vol. 23, p. 1-9., 2008NUNES, LA., ARAUJO, ED., CARVALHO, CAL. and WALDSCHMIDT, AM., 2008. Population Divergence of Melipona quadrifasciata anthidioides (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Endemic to the Semi-arid Region of the State of Bahia, Brazil. Sociobiology, vol. 52, p. 81-93.), the same does not seem to occur for wing shape. This might be associated to evolutionary constraints related to wing aerodynamic structure for flights. Wing shape variations were small and seemed to occur by chance around a very rigid pattern. These constraints, however, may represent a very interesting aspect for the development of morphometric techniques for the identification of this bee species.

Comparison of distance matrices for shape, geographic location, and altitude using the Partial Mantel Test for 5,000 permutations.

The Mantel correlation between matrices shows a positive correlation between geographic distance and the Mahalanobis generalised size distance as well as a correlation between size distance and altitude with high significance and margins of error below 5%, indicating collinearity among these effects (Table 2). The wing size is influenced by geographic distribution and altitude, however the largest variation contributing to the formation of distinct groups of M. quadrifasciata anthidioides along the semi-arid region of Bahia State is the effect of altitude.

Wing size obtained from the Mahalanobis distance and wing shape obtained from the Procrustes distance were not correlated (r = 0.03, p > 0.05), that is, size did not affect shape and vice-versa, demonstrating that these variables are independent.

4.Discussion

Wing shape can have more evolutionary constraints compared to wing size because shape is not associated with altitude or geographic variations. Size, on the other hand, can be related to a pleiotropic effect. Therefore, adaptive factors such as climate, feeding (Peruquetti, 2003PERUQUETTI, RC., 2003. Variação do tamanho corporal de machos de Eulaema nigrita Lepeletier (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Euglossini). Resposta maternal à flutuação de recursos? Revista Brasileira de Zoologia, vol. 20, no. 2, p. 207-212.), altitude as found by Nunes et al. (2007NUNES, LA., COSTA-PINTO, MFF., CARNEIRO, PLS., PEREIRA, DG. and WALDSCHMIDT, AM., 2007. Divergência Genética em Melipona scutellaris Latreille (Hymenoptera: Apidae) com base em Caracteres Morfológicos. Bioscience Journal, vol. 23, p. 1-9.; 2008)NUNES, LA., ARAUJO, ED., CARVALHO, CAL. and WALDSCHMIDT, AM., 2008. Population Divergence of Melipona quadrifasciata anthidioides (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Endemic to the Semi-arid Region of the State of Bahia, Brazil. Sociobiology, vol. 52, p. 81-93. may affect the local population size. Similarly, the effect of genetic drift must also be considered particularly in situations of habitat fragmentation and formation of small local populations, both of which intensify genetic drift, decrease intra-population variance and increase inter-population polymorphism.

Genetic drift allows some alleles to move on to the next generation at higher or lower frequency, to be lost or to be randomly fixed. Allele fixation by genetic drift depends primarily on its initial frequency in the population as a process occurring within every finite population, being faster in smaller populations (Stearns and Hoekstra 2000STEARNS, SC. and HOEKSTRA, RF., 2000. Evolution: an introduction. New York: Oxford University Press. 381pp.; Araújo et al., 2000). Genetic drift is particularly intense among the Meliponinae because they are monoandric, their populations are small and their habitat is fragmented, causing differences among the local populations, lower genetic variability within each population, and greater risk of population extinction.

Habitat fragmentation is one of the causes leading to lowering genetic variability. Therefore, rational bee keeping is interesting for the development of appropriate management and preservation of local populations in disturbed environments.

Similar studies conducted by Diniz-Filho et al. (1998)DINIZ-FILHO, JAF., BALESTRA, R., RODRIGUES, FM. and ARAÚJO, ED., 1998. Geographic variation of Tetragonisca angustula angustula Latreille (Hymenoptera, Meliponinae) in central and southeastern Brazil. Naturalia, vol. 23, p. 193-203. with populations of Tetragonisca angustula angustula found low cophenetic correlation coefficients and no geographic structure, demonstrating that somehow this species must maintain some level of gene flow. Something similar may be happening with M. quadrifasciata anthidioides that does not have a geographically structured population. Similar results were found by Mendes et al. (2007)MENDES, MFM., FRANCOY, TM., NUNES-SILVA, P., MENEZES, C. and IMPERATRIZ-FONSECA, VL., 2007. Intra-populational variability of Nannotrigona testaceicornis Lepeletier 1836 (Hymenoptera, Meliponini) using relative warp analysis. Bioscience journal, vol. 23, p. 147-152. who characterised a population of Nanntrigona testaceicornis and found more similar subpopulations that were related to similarities in inbreeding by geometric morphometrics. On the other hand, Diniz-Filho et al. (1998)DINIZ-FILHO, JAF., BALESTRA, R., RODRIGUES, FM. and ARAÚJO, ED., 1998. Geographic variation of Tetragonisca angustula angustula Latreille (Hymenoptera, Meliponinae) in central and southeastern Brazil. Naturalia, vol. 23, p. 193-203. found differences associated with size and geographic location. Similar results were found in this study, where body size was apparently more affected by the different habitats than the shape of these individuals. Bidau et al. (2012)BIDAU, CJ., MIÑO, CI., CASTILLO, ER. and MARTÍ, DA., 2012. Effects of Abiotic Factors on the Geographic Distribution of Body Size Variation and Chromosomal Polymorphisms in Two Neotropical Grasshopper Species (Dichroplus: Melanoplinae: Acrididae). Psyche, vol. 2012, no. 863947, p. 1-11. found that body size in species of grasshoppers is positively correlated with latitude, altitude, and seasonality, and that these factors influence development and growth.

Geographical distance and altitude influence the size of the wing of M. quadrifasciata anthidioides. This result confirms those found by Nunes et al. (2007)NUNES, LA., COSTA-PINTO, MFF., CARNEIRO, PLS., PEREIRA, DG. and WALDSCHMIDT, AM., 2007. Divergência Genética em Melipona scutellaris Latreille (Hymenoptera: Apidae) com base em Caracteres Morfológicos. Bioscience Journal, vol. 23, p. 1-9., who reported that the altitude is a factor that influences the divergence between the colonies of M. scutellaris as analysed by wing size. And Nunes et al. (2008)NUNES, LA., ARAUJO, ED., CARVALHO, CAL. and WALDSCHMIDT, AM., 2008. Population Divergence of Melipona quadrifasciata anthidioides (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Endemic to the Semi-arid Region of the State of Bahia, Brazil. Sociobiology, vol. 52, p. 81-93. found that wing size is affected by geographic distance and by altitude, with altitude causing greater variance on group formation among M. quadrifasciata anthidioides in Semi-Arid Region of Bahia State.

These results may be associated with Bergmans rule. According to this theory, animal body size varies with altitude and latitude (Bidau et al., 2012BIDAU, CJ., MIÑO, CI., CASTILLO, ER. and MARTÍ, DA., 2012. Effects of Abiotic Factors on the Geographic Distribution of Body Size Variation and Chromosomal Polymorphisms in Two Neotropical Grasshopper Species (Dichroplus: Melanoplinae: Acrididae). Psyche, vol. 2012, no. 863947, p. 1-11.). Hepburn et al. (2001)HEPBURN, HR., RADLOFF, SE., VERMA, S. and VERMA, LR., 2001. Morphometric analysis of Apis cerana populations in the southern Himalaya region. Apidologie, vol. 32, p. 435-447., by means of morphometric analysis, recorded that in the honeybee Apis cerana the body size increases with altitude, results congruent with this study. We conclude that there is a morphogenetic difference among populations of M. quadrifasciata antihidioides associated with wing size that is influenced by geographic location with emphasis on altitude. The thermal properties of bees are strongly dependent on body size and the size variation may be an adjust for environmental conditions that change with the altitude.

These results indicate greater evolutionary constraints for the shape variation, which must be directly associated with aerodynamic issues in this structure. The size, however, indicates that the bees tend to have larger wing in populations located at higher altitudes.

We thank the Coordination for Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), the Foundation for Research Support in the State of Bahia (FAPESB) for the financial support and the National Research Council of Brazil (CNPq) for the research fellowship to C.A.L. Carvalho (Process Number 303237/2010-4). We also thank the bee keepers for providing the biological material for this research.

References

- ARAÚJO. ED., DINIZ-FILHO, JAF. and OLIVEIRA, FA., 2000. Extinção de populações locais do gênero Melipona (Hymenoptera: Meliponinae): Efeito do tamanho populacional e da produção de machos por operárias. Naturalia, vol. 25, p. 287-299.

- BATALHA-FILHO, H., MELO, GAR., WALDSCHMIDT, AM., CAMPOS, LAO. and FERNANDES-SALOMÃO, TM., 2009. Geographic distribution and spatial differentiation in the color pattern of abdominal stripes of the Neotropical stingless bee Melipona quadrifasciata (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Zoologia, vol. 26, p. 213-219.

- BIDAU, CJ., MIÑO, CI., CASTILLO, ER. and MARTÍ, DA., 2012. Effects of Abiotic Factors on the Geographic Distribution of Body Size Variation and Chromosomal Polymorphisms in Two Neotropical Grasshopper Species (Dichroplus: Melanoplinae: Acrididae). Psyche, vol. 2012, no. 863947, p. 1-11.

- BOOKSTEIN, FL., 1991. Morphometric Tools for Landmark Data. Geometry and Biology. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- DINIZ-FILHO, JAF., BALESTRA, R., RODRIGUES, FM. and ARAÚJO, ED., 1998. Geographic variation of Tetragonisca angustula angustula Latreille (Hymenoptera, Meliponinae) in central and southeastern Brazil. Naturalia, vol. 23, p. 193-203.

- DINIZ-FILHO, JAF. and BINI, LM., 1994. Space-free correlation between morphometric and climatic data: a multivariate analysis of Africanized honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) in Brazil. Global Ecology and Biogeography Letters, vol. 4, p. 195-202.

- DINIZ-FILHO, JAF., HEPBURN, HR., RADLOFF, S. and FUCHS, S., 2000. Spatial analysis of morphological variation in African honeybees (Apis mellifera L.) on a continental scale. Apidologie, vol. 31, p. 191-204.

- FRANCOY, TM., GRASSI, ML., IMPERATRIZ-FONSECA, VL., MAY-ITZÁ, WJ. and QUEZADA-EUÁN, JJG., 2011. Geometric Morphometrics of the wing as a tool for assigning genetic lineages and geografic origin to Melipona beecheii (Hymenoptera: Meliponina). Apidologie, vol. 42, p. 499-507.

- FRANCOY, TM. and IMPERATRIZ-FONSECA, VL., 2010. A morfometria geométrica de asas e a identificação automática de espécies de abelhas. Oecologia Australis, vol. 14, p. 317-321.

- GRODNITSKY, DL., 1999. Form and Function of Insect Wings. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. 261p.

- HEPBURN, HR., RADLOFF, SE., VERMA, S. and VERMA, LR., 2001. Morphometric analysis of Apis cerana populations in the southern Himalaya region. Apidologie, vol. 32, p. 435-447.

- Klingenberg Lab, 2010. MorphoJ. Version 5.1. Available from: http://www.flywings.org.uk/MorphoJ_page.htm. Accessed in: 22 Dec. 2010.

» http://www.flywings.org.uk/MorphoJ_page.htm - MENDES, MFM., FRANCOY, TM., NUNES-SILVA, P., MENEZES, C. and IMPERATRIZ-FONSECA, VL., 2007. Intra-populational variability of Nannotrigona testaceicornis Lepeletier 1836 (Hymenoptera, Meliponini) using relative warp analysis. Bioscience journal, vol. 23, p. 147-152.

- MONTEIRO, LR., REIS, SF., DINIZ-FILHO, JAF. and ARAUJO, ED., 2002. Geometric estimates of heritability in biological shape. Evolution, vol. 56, p. 563-572.

- MONTEIRO, WR., 2000. Meliponicultura: A Mandaçaia (Melipona quadrifasciata). Mensagem Doce, vol. 57.

- MORETO, G. and ARIAS, MC., 2005. Detection of mitochondrial DNA restriction site differences between the subspecies of Melipona quadrifasciata Lepeletier (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Meliponini). Neotropical Entomology, vol. 34, p. 381-385.

- MOURE, JS. and KERR, WE., 1950. Sugestões para modificação da sistemática do gênero Melipona (Hymenoptera, Apoidea). Dusenia, vol. 18, p. 105-29.

- NUNES, LA., ARAUJO, ED., CARVALHO, CAL. and WALDSCHMIDT, AM., 2008. Population Divergence of Melipona quadrifasciata anthidioides (Hymenoptera: Apidae) Endemic to the Semi-arid Region of the State of Bahia, Brazil. Sociobiology, vol. 52, p. 81-93.

- NUNES, LA., COSTA-PINTO, MFF., CARNEIRO, PLS., PEREIRA, DG. and WALDSCHMIDT, AM., 2007. Divergência Genética em Melipona scutellaris Latreille (Hymenoptera: Apidae) com base em Caracteres Morfológicos. Bioscience Journal, vol. 23, p. 1-9.

- PERUQUETTI, RC., 2003. Variação do tamanho corporal de machos de Eulaema nigrita Lepeletier (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Euglossini). Resposta maternal à flutuação de recursos? Revista Brasileira de Zoologia, vol. 20, no. 2, p. 207-212.

- RATTANAWANNEE, A., CHANCHAO, C. and WONGSIRI, S., 2012. Geometric morphometric analysis of giant honeybee (Apis dorsata Fabricius, 1793) populations in Thailand. Journal of Asia-Pacific Entomology, vol. 15, p. 611-618

- ROHLF, FJ., 2006. TPSDIG2 for Windows version 2.10. Available from: http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/index.html. Accessed in July 20, 2008.

» http://life.bio.sunysb.edu/morph/index.html - SCHWARZ, H., 1948. Stingless bees (Meliponidae) of the Western Hemisphere. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, vol. 90, p. 1-167.

- STEARNS, SC. and HOEKSTRA, RF., 2000. Evolution: an introduction. New York: Oxford University Press. 381pp.

- TOFILSKI, A., 2008. Using geometric morphometrics and standard morphometry to discriminate three honeybee subspecies. Apidologie, vol. 39, p. 558-563.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

Nov 2013

History

-

Received

27 Aug 2012 -

Accepted

5 Nov 2012