Abstracts

To describe plant phenological patterns and correlate functioning for the quantity and quality of resources available for the pollinator, it is crucial to understand the temporal dynamics of biological communities. In this way, the pollination syndromes of 46 species with different growth habits (trees, shrubs, herbs, and vines) were examined in an area of Caatinga vegetation, northeastern Brazil (7° 28′ 45″ S and 36° 54′ 18″ W), during two years. Flowering was monitored monthly in all the species, over two years (from January 2003 to December 2004). Pollination syndromes were characterised based on floral traits such as size, colour, morphology, symmetry, floral resources, as well as on direct visual observation of floral visitors on focal plants and published information. We observed differences among the plant growth habits with respect to floral traits, types of resources offered, and floral syndromes. The flowering periods of the species varied among floral syndrome groups. The majority of the melittophilous species flowered during the rainy season in the two study years, while the species of the other pollination syndroms flowered at the end of the dry season. An asynchrony of flowering was noted among the chiropterophilous species, while the phalenophilous group concentrated during the rainy season. The overall availability of floral resources was different during the rainy and the dry seasons, and also it varied among plants with different growth habits. The availability of oil-flowers coincided with the period of low nectar availability. We observed a relationship between the temporal distribution of the pollination syndromes and the availability of floral resources among each growth habits in this tropical ecosystem. Resource allocation in seasonal environments, such as the Caatinga, can function as a strategy for maintaining pollinators, facilitating therefore the reproductive success of plant species. The availability of floral resources during all the year, specially in seasonal environments such as the Caatinga, may function as a strategy to maintain pollinator populations ensuring the reproductive success of the plants.

pollination syndromes; floral resources; dry forests; seasonality

Descrever o padrão fenológico das plantas e correlacionar com a quantidade e qualidade dos recursos disponíveis para os polinizadores é fundamental para entender a dinâmica temporal das comunidades biológicas. Neste sentido, foram estudadas as síndromes de polinização de 46 espécies com diferentes hábitos (árvores, arbustos, ervas, trepadeiras) em uma área de caatinga, no Cariri Paraibano no Nordeste do Brasil (7° 28′ 45″ S e 36° 54′ 18″ W) durante dois anos. Para as diferentes espécies foi acompanhado o período de floração, sendo destacada a fase de início e o pico. As síndromes de polinização foram caracterizadas com base nos atributos florais, como tamanho, cor, morfologia, simetria, tipo de recurso, bem como a partir de observações visuais diretas dos visitantes florais em plantas focais e informações de literatura. Foram encontradas diferenças entre os hábitos, relacionadas aos distintos atributos florais, tipo de recurso e síndrome floral. O período de floração das espécies mostrou-se distinto entre os diferentes tipos de síndromes. A maioria das espécies melitófilas floresceu na estação úmida, enquanto as demais no final da estação seca, nos dois anos de estudo. Foi observada assincronia na floração das espécies quiropterófilas e concentração entre as esfingófilas na estação úmida. A disponibilidade de recursos florais apresentou diferenças entre as estações seca e chuvosa, diferindo também entre os hábitos. A oferta de flores de óleo coincidiu com o período de menor disponibilidade de néctar. Foi observada relação entre a distribuição temporal das diferentes síndromes de polinização, juntamente com a disponibilidade dos recursos florais, nos diferentes hábitos para este ecossistema tropical. A alocação de recursos em ambientes sazonais, como a Caatinga estudada, pode funcionar como uma estratégia para manutenção de polinizadores, facilitando, portanto o sucesso reprodutivo das espécies vegetais.

sindromes de polinização; recursos florais; florestas secas; sazonalidade

1. Introduction

The seasonality of the climate influences the flowering patterns of tropical forest species (Janzen, 1967JANZEN, DH., 1967. Synchronization of sexual reproduction of trees within the dry season in Central America. Evolution, vol. 21, p. 620-637. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2406621

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2406621...

; Morellato et al. 1989MORELLATO, LPC., RODRIGUES, RR., LEITÃO-FILHO, HF. and JOLY, CA., 1989. Estudo comparativo da fenologia de espécies arbóreas de floresta de altitude e floresta mesófila semidecídua na Serra do Japi, Jundiaí, SP. Revista Brasileira de Botânica, vol. 12, p. 85-98.; Morellato, 2003), with direct consequences for plant-pollinator relationships (Heithaus, 1974HEITHAUS, ER., 1974. The role of plant-pollinator interactions in determining community structure. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, vol. 61, p. 675-691. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2395023

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2395023...

; Stiles, 1977STILES, FG., 1977. Coadapted competitors: the flowering seasons of hummingbird-pollinated plants in a tropical forest. Science, vol. 198, p. 1177-1178. PMid:17818936. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.198.4322.1177

http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.198.43...

). The spatial and temporal distribution of species with different pollination syndromes may represent strategies to avoid competition for pollinators among synchronously flowering species (Ramírez, 2004).

Numerous studies have examined reproductive biology within plant communities (Baker, 1959BAKER, HG., 1959. Reproductive methods as factors in the speciation in flowering plants. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology, vol. 24, p. 177-191. PMid:13796002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/SQB.1959.024.01.019

http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/SQB.1959.024.0...

; Bawa, 1990, Oliveira and Gibbs, 2000OLIVEIRA, PE. and GIBBS, PE., 2000. Reproductive biology of woody plants in a cerrado community of central Brazil. Flora, vol. 195, p. 311-329.; Ramírez, 2004), although few of them have analysed the relationship between flowering periods and pollination systems, or the availability of floral resources in tropical plant communities (see Parra-Tabla and Bullock, 2002PARRA-TABLA, V. and BULLOCK, SH. 2002. La polinización en la selva tropical de Chamela. In NOGUEIRA, FA., VEGA RIVERA, JHA., GARCIA ALDRETE, N. and QUESADA AVENDAÑO, M. (Eds.). Historia Natural de Chamela. Instituto de Biologia, UNAM. p. 499-515.). According to Bullock (1985)BULLOCK, SH., 1985. Breeding systems in the flora of a tropical deciduos forest in Mexico. Biotropica, vol. 17, p. 287-301. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2388591

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2388591...

, the time and the duration of flowering among plant groups differ according to their pollen vectors. Morellato (1991)MORELLATO, LPC., 1991. Estudo da fenologia de árvores, arbustos e lianas de uma floresta semidecídua no sudeste do Brasil. São Paulo: Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Ph.D. Thesis. observed that the climate seasonality influence the temporal organisation of the plants (trees, shrubs, vines) and the pollinators.

In a region marked by a pronounced seasonality and low annual rainfall rates (500-700 mm) – does the Caatinga of northeastern Brazil present a strategy of resource allocation which facilitates the maintenance of pollinators? Is this distribution sufficient for maintenance of various groups of pollinators? What pollination syndromes are present in the community? In what proportions do the different syndromes occur? Do pollination syndromes differ between the strata of the community?

Recently the plants in this ecosystem have been examined for pollination syndromes (Machado, 1990MACHADO, IC., 1990. Biologia floral de espécies de caatinga no Município de Alagoinha- PE. São Paulo: Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Ph.D. Thesis.; Machado and Lopes, 2004MACHADO, IC. and LOPES, AV., 2004. Floral traits and pollination systems in the Caatinga, a Brazilian Tropical Dry Forest. Annals of Botany, vol. 94, p. 365-376. PMid:15286010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152...

) and sexual systems (Machado et al., 2006MACHADO, IC., LOPES, AV. and SAZIMA, M., 2006. Plant sexual systems and review of the breeding system studies in the Caatinga, a Brazilian Tropical Dry Forest. Annals of Botany, vol. 97, p. 277-287.). However, very little is known about the phenology of these species or the temporal availability of floral resources for the Caatinga plant communities.

We studied the floral biology of plant species, recording their sexual systems, flower shapes, dimensions, resources, colours, and syndromes. In addition, we monitored the flowering phenology so as to assess flower resource availability, throughout the year, for the pollinator groups. The present work examined the possible influences of climate seasonality on the frequencies of the different pollination syndromes and on the availability of floral resources during the rainy and dry seasons in an area of Caatinga vegetation in NE Brazil, with the objective of contributing to our understanding of pollination ecology and the flowering strategies encountered in dry forests.

2. Methods

2.1. Study area

Fieldwork was carried out at the Fazenda Almas Private Nature Reserve, in the municipality of São José dos Cordeiros (7° 28′ 45″ S and 36° 54′ 18″ W), Paraíba state, Brazil, between 1/2003 and 12/2004. The reserve is located in the Cariri Paraibano region, a depression zone 200 to 300 meters lower than the surrounding Borborema plateau. The local vegetation is arboreal and shrub Caatinga (Andrade-Lima, 1981ANDRADE-LIMA, D., 1981. The caatinga's dominium. Revista Brasileira de Botânica, vol. 4, p. 149-53.).

The local climate is classified as “hot semi-arid” (Bsh), with rainfall during the summer months, according to the classification system of Köppen. Rainfall is extremely irregular and usually totals less than 600 mm per year; solar radiation is high, relative humidity low as is cloud cover, and the average temperatures range from 26 to 30 °C (Prado, 2003PRADO, DE., 2003. As caatingas da América do Sul. In LEAL, IR., TABARELLI, M. and SILVA, JMC. (Orgs.). Ecologia e Conservação da Caatinga. Recife: Editora UFPE. p. 3-74.). Climatic records indicate the existence of two well-defined seasons, a rainy season concentrated into three months of the year (generally during the first trimester), and a dry season lasting from six to nine months (or occasionally longer) (Paraíba and UFPB, 1989).

2.2. Floral traits and species

A total of 46 different species were examined, including trees (36.9% of the total number of species), shrubs (32.6%), herbs (13%) and vines (17.4%). These plants belong to 22 plant families and 40 genera (Table 1) and corresponded to 23.6% of the total number of species known in that plant community (Lima, 2004LIMA, IB., 2004. Levantamento florístico da reserva particular do patrimônio natural Fazenda Almas, São José dos Cordeiros -PB. Universidade Federal da Paraíba. Monografia de Graduação.). The choice of the species selected for examination was based on phenological studies undertaken in the area (Quirino, 2006QUIRINO, ZGM., 2006. Fenologia, síndromes de polinização e dispersão e recursos florais de especies vegetais do Cariri Paraibano. Recife: Universidade Federal de Pernambuco. Ph.D. Thesis.; Quirino et al., in prep.) and took into consideration the most important Caatinga families and species (Rodal and Sampaio, 2002RODAL, MJN. and SAMPAIO, EVSB., 2002. A vegetação do bioma caatinga. In SAMPAIO, EVSB., GIULIETTI, AM., VIRGÍNIO, J. and ROJAS, CFLG. (Eds.). Vegetação e flora da caatinga. Recife: APNE/CNIP. p. 11-24.). The site was visited twice a month in order to monitor flowering activity during the entire two years of study. The floral traits of each species were observed or sampled, including flower type, colour, morphology, size, symmetry, type of floral resource, and animal visitors, and their sexual systems were classified according to the criteria described by Machado and Lopes (2004)MACHADO, IC. and LOPES, AV., 2004. Floral traits and pollination systems in the Caatinga, a Brazilian Tropical Dry Forest. Annals of Botany, vol. 94, p. 365-376. PMid:15286010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152...

and Machado et al. (2006)MACHADO, IC., LOPES, AV. and SAZIMA, M., 2006. Plant sexual systems and review of the breeding system studies in the Caatinga, a Brazilian Tropical Dry Forest. Annals of Botany, vol. 97, p. 277-287.. Flowers from all species were collected and fixed in 70% ethanol for complementary laboratory analyses.

Species observed at the Fazenda Almas Private Nature Reserve, municipality of São José dos Cordeiros, Paraíba state, Brazil, indicating their growth habits and pollination syndromes. N = numbers of individuals observed.

Flower types were determined following the classification system of Faegri and Pijl (1979)FAEGRI, K. and PIJL, L., 1979. The principles of pollination ecology. London: Pergamin Press.. To determine flower size, 10 samples from each species were measured and subsequently classified as either small (≤ 10 mm), medium (> 10 ≤ 20 mm), or large (> 20 mm). Flower colours were classified into seven categories, considering the most evident tone (white, red or pink, yellow, green, orange, purple, and violet).

Flowers were also classified in terms of their pollination units, according to Ramírez et al. (1990)RAMÍREZ, N., GIL, C., HOKCHE, O., SERES, A. and BRITTO, Y. 1990. Biologia floral de uma comunidade arbustiva tropical em la Guayannna Venezolana. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, vol. 77, p. 1260-271. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2399554

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2399554...

: 1) individual, when a floral visit occurs on only a single flower; and 2) collective, when floral visitors enter into contact simultaneously with more than one flower when these are grouped into inflorescences. The species were also grouped into pollination guilds according to the principal pollen vector (sensu Faegri and Pijl, 1979FAEGRI, K. and PIJL, L., 1979. The principles of pollination ecology. London: Pergamin Press.).

3. Results

3.1. Floral traits and pollination syndromes

In general, the floral traits and the pollination syndromes of the species examined varied among the different growth habitats.

White flowers predominated, representing 39% of all observed species, followed by red/pink (24%), yellow (19.5%), green (8.7%), orange (4.3%), purple, and then violet (4.3%).

Small and medium-sized flowers were the most common among the species studied, representing 39% and 37% of the total, respectively. Small flowers were observed on more than half of the tree species, while a majority of the shrubs and herbs had medium-sized flowers (Table 1).

An examination of the pollination units of the plants revealed that the “individual” type was prevalent found in 63% of all the species, while “collective” units were observed in the other 37% of the species.

Seven floral types were observed (chamber, campanulate, disk, flag, inconspicuous, brush, and tube). The floral types encountered among each of the different plant growth habit types (trees, shrubs, herbs, and vines) had percentages similar to those of the general community.

Actinomorphic flowers were observed in a majority of the species (78.3%), and are associated with the most common floral types, such as tube and disk. Among the zygomorphic flowers (21.7%), the flag was the principal type. In relation to sexual systems, a greater frequency (82.6%) of hermaphroditic species, followed by monoecious plants (8.7%), dioecious (6.5%), and andromonoecious (2.1%) (represented only by one single species) (Table 1).

The pollination syndromes encountered in the plant community included: melittophily (65.2%), phalenophily (13%, including here flowers pollinated by sphingids and nocturnal moths), chiropterophily (11%), ornithophily (6.5%), as well as cantharophily and psychophily (4.3% each). Differences among the frequencies of pollination syndromes were noted among the different plant habits. Melittophily was most frequent, regardless the plant growth habit. Melittophily was observed 82% of the arboreal species, and no ornitophilous species were found among the tree species examined. Shrub species demonstrated the greatest diversity of pollination syndromes, with a diminished frequency of melittophilous (ca. 46%). The herbaceous demonstrated syndrome proportions similar to those of the shrubs, although ornitophilous species were observed in this habit. The proportion of melittophilous species found among vines was similar to that found among the tree, and both of these habit types had reduced diversities of pollination systems (only melittophily, chiropterophily, and ornithophily).

The numbers of species blooming in each pollination syndrome varied from month to month during the two years of the study (Figure 1). In January, all of the pollination syndromes were represented, while in the other months at least three floral syndromes were represented.

Distribution of the species flowering each month in terms of their pollination syndromes, at the Fazenda Almas Private Nature Reserve, municipality of São José dos Cordeiros, Paraíba state, Brazil, during the years 2003 and 2004.

Melittophilous species were observed flowering throughout the year, with two peaks – one during the rainy season (February) and another during the dry seanson (November/December) in both study years (Figure 1). Sequential flowering peaks occurred during the year, with a majority of the melittophilous species (66.7%) peaking during the rainy season or the transition; the other species (33.3%) peaked during the dry season. The flowering peaks of the melittophilous species occurred in the dry season during both study years (Figure 2).

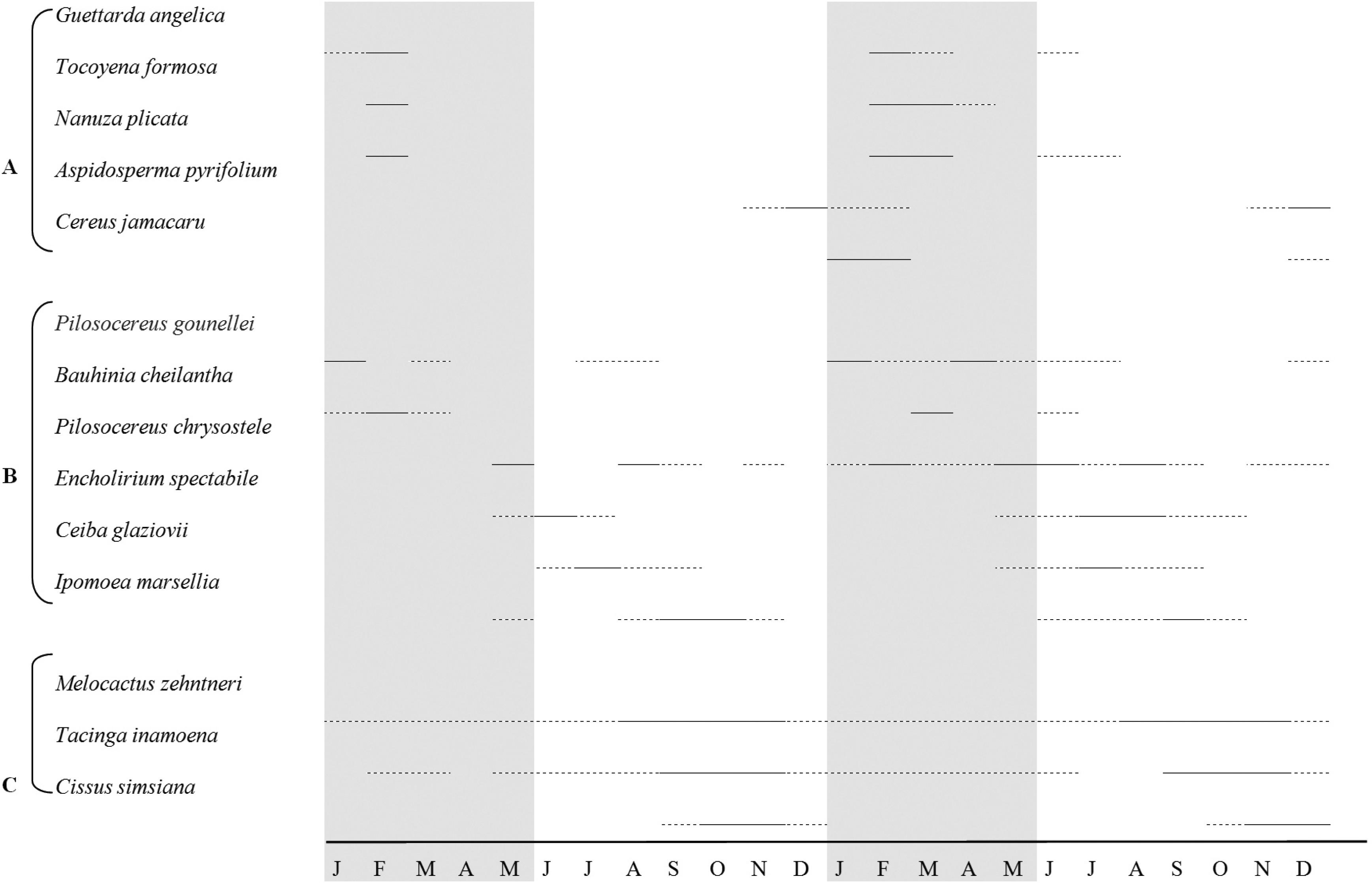

Flowering periods of melittophilous species during the years 2003 and 2004, at the Fazenda Almas Private Nature Reserve, municipality of São José dos Cordeiros, Paraíba state, Brazil. (- - -) Flowering; (–––) Flowering peak; rainy season indicated in grey tone.

The phalenophilous species generally show short and synchronous flowering (Figure 3). The majority of phalenophilous species initiated flower production during the rainy season (Figures 1 and 3), peaking in the wettest months. Only Aspidosperma pyrifolium (Apocynaceae) presented a flowering peak at the end of the dry season (Figure 3).

Flowering periods of phalenophilous (A), chiropterophilous (B) and ornitophilous (C) species at the Fazenda Almas Private Nature Reserve, Paraíba state, Brazil, during the years 2003 and 2004. (- - -) Flowering; (–––) Flowering peak; rainy season indicated in grey tone.

Chiropterophilous species did not show regular flower production, flowering during almost the entire study period, with a small peak at the start of the dry season (Figure 1). Flowering was asynchronous, with sequential peaks (Figure 3), although the flowering duration was generally long, only few flowers open every night.

Flowering among ornitophilous species also occurred continuously at the community level, with synchronous peaks at the end of the dry season (Figures 1 and 3). Flowering patterns among ornitophilous species varied at the population level, with some species blooming all year long, while some species flowered only during two months of the year.

The syndromes of psychophily and cantharophily were represented by only a single species each, and these were observed flowering only during the rainy season. Flower production in these two species occurred only in four to five months during the two study years (Figure 3).

Only two species Croton (Euphorbiaceae) presented floral traits compatible with wind and insect pollination, and were considered as ambophilous.

3.2. Floral resources

The examined species offered nectar, pollen, and oils as floral resources. Nectar was the most frequent primary resource, being produced by 80% of the species, followed by nectar/pollen (11%), pollen (6.5%), and oils (2%) (the latter being offered by only one species, Stigmaphyllum paralias, Malpighiaceae). Nectar production predominated within all of the plant growth habits, while species offering both nectar and pollen as primary resources were only observed among the trees and shrubs. The species that offered only pollen were all shrubs or herbaceous plants.

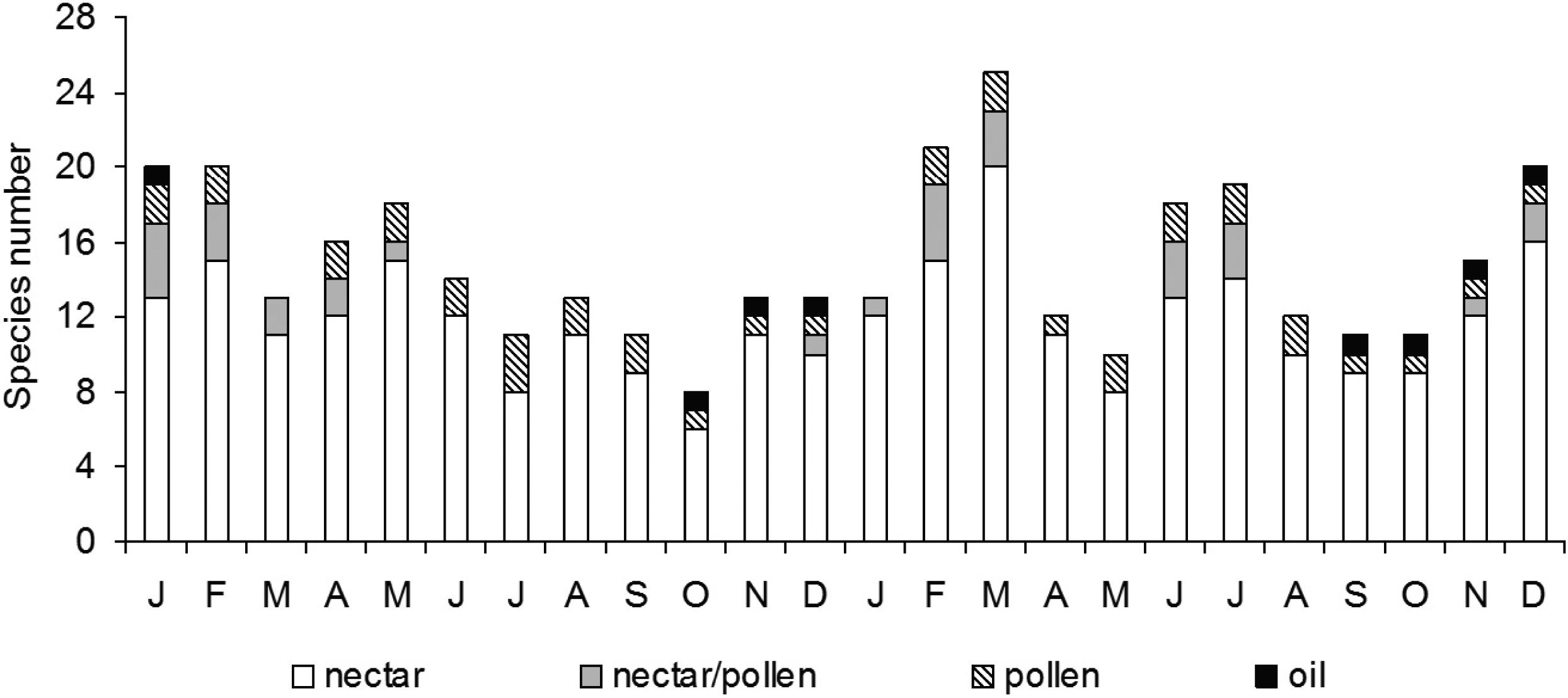

Two species that offers nectar presented flowering peaks during the rainy season and one at the end of the dry season, although these peaks occurred at different times in the two studied years. The lowest number of species offering nectar as the principal floral resource occurred in September and October (dry season) (Figure 4).

Distribution of floral resources by species at the Fazenda Almas Private Nature Reserve, Paraíba state, Brazil, during the years 2003 and 2004.

The species offering nectar/pollen showed flowering peaks during the rainy season (Figure 4). During the first year only one peak was registered during the rainy season. During the second year, three distinct peaks were observed, with the largest peak occurring during the rainy season, one of the two minor peaks occurred during the rain to dry season transition, and the other minor peak the dry season.

Flowers offering only pollen occurred almost continually and with a regular frequency (Figure 4). The single species producing floral-oil was observed flowering only at the end of the dry season.

4. Discussion

The large proportion of white flowers encountered in the present study contrasted with the observations of Machado and Lopes (2004)MACHADO, IC. and LOPES, AV., 2004. Floral traits and pollination systems in the Caatinga, a Brazilian Tropical Dry Forest. Annals of Botany, vol. 94, p. 365-376. PMid:15286010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152...

in another area of Caatinga, however, are similar to those reported other tropical plant communities such as the Cerrado (Martins and Batalha, 2006MARTINS, FQ. and BATALHA, MA., 2006. Pollination systems and floral traits in Cerrado woody species of the upper Taquari Region (Central Brazil). Brazilian Journal of Biology, vol. 66, p. 543-552. PMid:16862310. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1519-69842006000300021

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1519-69842006...

; Mantovani and Martins, 1988MANTOVANI, W. and MARTINS, FR., 1988. Variações fenológicas do cerrado da reserva Biológica de Mogi Guaçu, Estado de São Paulo. Revista Brasileira de Botânica, vol. 11, p. 101-112.; Oliveira and Gibbs, 2000OLIVEIRA, PE. and GIBBS, PE., 2000. Reproductive biology of woody plants in a cerrado community of central Brazil. Flora, vol. 195, p. 311-329.; Silberbauer-Gottsberger and Gottsberger, 1988SILBERBAUER-GOTTSBERGER, I. and GOTTSBERGER, G., 1988. A polinização de plantas do cerrado. Revista Brasileira de Biologia = Brazilian Journal of Biology, vol. 48, p. 651-663.), Restinga (coastal vegetation) (Ormond et al., 1993ORMOND, WT., PINHEIRO, MCB., LIMA, AH., CORREIA, MCR. and PIMENTA, ML., 1993. Estudo das recompensas florais das plantas de restinga da Maricá – Itaipaçu, RJ. I – Nectaríferas. Bradea, vol. 6, p. 179-195.) and Atlantic forest (Silva et al., 1997SILVA, AG., GUEDES-BRUNI, RR. and LIMA, HM., 1997. Sistemas sexuais e recursos florais do componente arbustivo-arbóreo em mata preservada na Reserva Ecológica de Macaé de Cima. In LIMA, HC. and GUEDES-BRUNI, RR. (Eds.). Serra de Macaé de Cima: diversidade florística e conservação em mata atlântica. Rio de Janeiro: Jardim Botânico. p. 182-211.). The similarities in the flower colours among different vegetation types suggests a weak relationship between this attribute and type of ecosystem, as previously noted by Johnson and Steiner (2000)JOHNSON, SD. and STEINER, KE., 2000. Generalization versus specialization in plant pollination systems. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, vol. 15, p. 140-143. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(99)01811-X

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(99)...

. The absence of relationship between plant habit and flower colour reported here is similar to the results undertaken in the tropical forests of Malaysia by Momose et al. (1998)MOMOSE, KT., YUMOTO, T., NAGAMITSU, T., NAGAMASU, H., SAKAI, RD., HARRINSIN, RD., ITIOKA, T., HAMID, AA. and INQUE, T., 1998. Pollination biology in a lowland dipterocarp forest in Sarawak, Malaysia. I. Characteristics of the plant-pollinator community in a lowland dipterocarp Forest. American Journal of Botany, vol. 85, p. 1477-1501. PMid:21684899. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2446404

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2446404...

and in Mexico by Parra-Tabla and Bullock (2002)PARRA-TABLA, V. and BULLOCK, SH. 2002. La polinización en la selva tropical de Chamela. In NOGUEIRA, FA., VEGA RIVERA, JHA., GARCIA ALDRETE, N. and QUESADA AVENDAÑO, M. (Eds.). Historia Natural de Chamela. Instituto de Biologia, UNAM. p. 499-515.. However, flower colour does seem to be associated with certain pollination syndromes, such as ornithophily, phalenophily, and chiropterophily (Grant, 1966GRANT, KA., 1966. A hypothesis concerning the prevalence of red colouration in California hummingbird flowers. American Naturalist, vol. 100, p. 85-97. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/282403

http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/282403...

; Leal et al., 2006LEAL, FC., LOPES, AV. and MACHADO, IC., 2006. Polinização por beija-flores em uma área de Caatinga no Município de Floresta, Pernambuco, Nordeste do Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Botânica, vol. 29, p. 379-389.; Muchhala and Jarrin-V, 2002MUCHHALA, N. and JARRIN-V, P., 2002. Flower visitation by bats in cloud forests of Western Ecuador. Biotropica, vol. 34, p. 387-395. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7429.2002.tb00552.x

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7429.20...

; Oliveira et al., 2004OLIVEIRA, PE., GIBBS, PE. and BARBOSA, AA., 2004. Moth pollination of woody species in the cerrados of central Brazil: a case of so much owed to so few? Plant Systematics and Evolution, vol. 245, p. 41-54.).

The proportions of tube, disk, and flag flower types observed in the present work were similar to those reported by Machado and Lopes (2004)MACHADO, IC. and LOPES, AV., 2004. Floral traits and pollination systems in the Caatinga, a Brazilian Tropical Dry Forest. Annals of Botany, vol. 94, p. 365-376. PMid:15286010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152...

for another Caatinga area. According to these authors, floral types such as tube and flag restrict access to the nectar and acting as a selective factor for floral visitors and reduce nectar losses to pillagers.

The majority of the species (82.6%) in Cariri Paraibano were hermaphroditic, a similar situation to that observed in other tropical ecosystems (see Machado and Lopes, 2004MACHADO, IC. and LOPES, AV., 2004. Floral traits and pollination systems in the Caatinga, a Brazilian Tropical Dry Forest. Annals of Botany, vol. 94, p. 365-376. PMid:15286010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152...

; Parra-Tabla and Bullock, 2002PARRA-TABLA, V. and BULLOCK, SH. 2002. La polinización en la selva tropical de Chamela. In NOGUEIRA, FA., VEGA RIVERA, JHA., GARCIA ALDRETE, N. and QUESADA AVENDAÑO, M. (Eds.). Historia Natural de Chamela. Instituto de Biologia, UNAM. p. 499-515.). The proportion of dioecious species (6.5%) was greater than that observed in another Caatinga area (2.1%) by Machado and Lopes (2004)MACHADO, IC. and LOPES, AV., 2004. Floral traits and pollination systems in the Caatinga, a Brazilian Tropical Dry Forest. Annals of Botany, vol. 94, p. 365-376. PMid:15286010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152...

, but less than that encountered in other tropical studies (between 15 and 23%) (Bawa et al., 1985aBAWA, KS., PERRY, DR. and BEACH, JH., 1985a. Reproductive biology of tropical lowland rain forest trees. I. Sexual systems and incompatibility mechanisms. American Journal of Botany, vol. 72, p. 331-343. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2443526

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2443526...

; Kress and Beach, 1994KRESS, WJ. and BEACH, JH., 1994. Flowering plant reproductive systems. In McDADE, LA., BAWA, KS., HESPENHEIDE, H. and HARTSHORN, G. (Eds.). La Selva: ecology and natural history of a neotropical rain forest. University of Chicago: Press in Chicago. p. 161-182.; Oliveira and Gibbs, 2000OLIVEIRA, PE. and GIBBS, PE., 2000. Reproductive biology of woody plants in a cerrado community of central Brazil. Flora, vol. 195, p. 311-329.), or in a Restinga zone (35%) when only dominant woody species where surveyed (Matallana et al., 2005MATALLANA, G., WENDT, T., ARAÚJO, DSD. and SCARANO, FR., 2005. High abundance of dioecious plants in tropical coastal vegetation. American Journal of Botany, vol. 92, p. 1513-1519. PMid:21646169. http://dx.doi.org/10.3732/ajb.92.9.1513

http://dx.doi.org/10.3732/ajb.92.9.1513...

). These differences among tropical environments reinforce the views of Richards (1986)RICHARDS, AJ., 1986. Plant breeding systems. London: Allen & Uwnwin. and Freeman et al. (1997)FREEMAN, DC., COUST, JL., EL-KEBLAWI, A., MIGLIA, KJ. and McARTHUR, ED., 1997. Sexual specialization and inbreeding avoidance in the evolution of dioecy. Botanical Review, vol. 63, p. 65-92. suggesting a polyphyletic origin of dioecy during the evolution of the angiosperms. Dioecy is only found among woody species in Caatinga vegetation (Machado et al., 2006MACHADO, IC., LOPES, AV. and SAZIMA, M., 2006. Plant sexual systems and review of the breeding system studies in the Caatinga, a Brazilian Tropical Dry Forest. Annals of Botany, vol. 97, p. 277-287.; Leite and Machado, 2010LEITE, AV. and MACHADO, IC., 2010. Reproductive biology of woody species in Caatinga, a dry forest of northeastern Brazil. Journal of Arid Environments, vol. 74, p. 1374-1380. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2010.05.029

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.201...

), supporting previous studies associating this sexual system to shrub and tree habit (Flores and Schemske, 1984FLORES, S. and SCHEMSKE, DW., 1984. Dioecy and monoecy in the flora of Puerto Rico and Virgin Islands: ecological correlates. Biotropica, vol. 16, p. 132-139. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2387845

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2387845...

; Matallana et al., 2005MATALLANA, G., WENDT, T., ARAÚJO, DSD. and SCARANO, FR., 2005. High abundance of dioecious plants in tropical coastal vegetation. American Journal of Botany, vol. 92, p. 1513-1519. PMid:21646169. http://dx.doi.org/10.3732/ajb.92.9.1513

http://dx.doi.org/10.3732/ajb.92.9.1513...

; Parra-Tabla and Bullock, 2002PARRA-TABLA, V. and BULLOCK, SH. 2002. La polinización en la selva tropical de Chamela. In NOGUEIRA, FA., VEGA RIVERA, JHA., GARCIA ALDRETE, N. and QUESADA AVENDAÑO, M. (Eds.). Historia Natural de Chamela. Instituto de Biologia, UNAM. p. 499-515.).

Small and medium-sized flowers predominated in the present study, a situation quite different from that reported by Machado and Lopes (2004)MACHADO, IC. and LOPES, AV., 2004. Floral traits and pollination systems in the Caatinga, a Brazilian Tropical Dry Forest. Annals of Botany, vol. 94, p. 365-376. PMid:15286010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152...

, who observed a greater frequency of large flowers in another Caatinga area. Numerous studies have noted a size correlation between flower and pollinator (Dafni and Kevan, 1997DAFNI, A., and KEVAN, PG., 1997. Flower size and shape: implications in pollination. Israel Journal of Plant Sciences, vol. 45, p. 201-211. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07929978.1997.10676684

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07929978.1997....

), and as a general rule species with small flowers are visited by small animals, such as small insects (Bawa et al., 1985bBAWA, KS., BULLOCK, SH., PERRY, DR., COVILLE, RE. and GRAYUM, MH., 1985b. Reproductive biology of tropical lowland rain forest trees. II. Pollination systems. American Journal of Botany, vol. 72, p. 345-356.). In some cases, however, smaller flower dimensions may be associated with body parts of the pollinators, such as the length and width of the beak of a hummingbird in relation to the floral tube or to the diameter of the corolla tube (Arizmendi and Ornelas, 1990ARIZMENDI, MC. and ORNELAS, JF., 1990. Hummingbirds and their floral resources in a tropical dry Forest in México. Biotropica, vol. 22, p. 172-180. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2388410

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2388410...

).

The large proportion of tree species with small flowers recorded in the present study diverges from the view of Gentry (1995)GENTRY, A., 1995. Diversity and floristic composition of neotropical dry forest. In BULLOCK, SH., MOONEY, HA. and MEDINA, E. (Eds.). Seasonally dry tropical forest. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 146-194. that dry environments tend to have larger proportions of woody species with large flowers. However, the study area has the lowest rainfall rates of Brazil, and as such it may demonstrate differences from others dry ecosystems in the region (Rodal and Sampaio, 2002RODAL, MJN. and SAMPAIO, EVSB., 2002. A vegetação do bioma caatinga. In SAMPAIO, EVSB., GIULIETTI, AM., VIRGÍNIO, J. and ROJAS, CFLG. (Eds.). Vegetação e flora da caatinga. Recife: APNE/CNIP. p. 11-24.).

4.1. Pollination syndromes and seasonality

The predominance of melittophily in all habits, indicating that the bees are important vectors of pollination throughout the vertical space occupied by the shrub and tree components. The melittophilous rate observed in the study area has also been reported for other Caatinga areas (Machado and Lopes, 2004MACHADO, IC. and LOPES, AV., 2004. Floral traits and pollination systems in the Caatinga, a Brazilian Tropical Dry Forest. Annals of Botany, vol. 94, p. 365-376. PMid:15286010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152...

) and in other studies in tropical regions (Bawa et al., 1985bBAWA, KS., BULLOCK, SH., PERRY, DR., COVILLE, RE. and GRAYUM, MH., 1985b. Reproductive biology of tropical lowland rain forest trees. II. Pollination systems. American Journal of Botany, vol. 72, p. 345-356.; Oliveira and Gibbs, 2000OLIVEIRA, PE. and GIBBS, PE., 2000. Reproductive biology of woody plants in a cerrado community of central Brazil. Flora, vol. 195, p. 311-329.; Parra-Tabla and Bullock, 2002PARRA-TABLA, V. and BULLOCK, SH. 2002. La polinización en la selva tropical de Chamela. In NOGUEIRA, FA., VEGA RIVERA, JHA., GARCIA ALDRETE, N. and QUESADA AVENDAÑO, M. (Eds.). Historia Natural de Chamela. Instituto de Biologia, UNAM. p. 499-515.; Ramírez et al., 1990RAMÍREZ, N., GIL, C., HOKCHE, O., SERES, A. and BRITTO, Y. 1990. Biologia floral de uma comunidade arbustiva tropical em la Guayannna Venezolana. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, vol. 77, p. 1260-271. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2399554

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2399554...

; Silberbauer-Gottsberger and Gottsberger, 1988SILBERBAUER-GOTTSBERGER, I. and GOTTSBERGER, G., 1988. A polinização de plantas do cerrado. Revista Brasileira de Biologia = Brazilian Journal of Biology, vol. 48, p. 651-663.).

The predominantly seasonal flowering pattern of melittophilous species in the present study, with large numbers of open flowers every day, was similar to patterns observed in other tropical ecosystems by Parra-Tabla and Bullock (2002)PARRA-TABLA, V. and BULLOCK, SH. 2002. La polinización en la selva tropical de Chamela. In NOGUEIRA, FA., VEGA RIVERA, JHA., GARCIA ALDRETE, N. and QUESADA AVENDAÑO, M. (Eds.). Historia Natural de Chamela. Instituto de Biologia, UNAM. p. 499-515.and Frankie et al. (1974)FRANKIE, GW., BAKER, HG. and OPLER, PA., 1974. Comparative phonological studies of trees in tropical lowland wet and dry forest sites of Costa Rica. Journal of Ecology, vol. 62, p. 881-913. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2258961

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2258961...

, and indicates a relationship between flowering of these species and pollination.

Differences between pollination systems and plant growth habits have been reported for tropical environments (Frankie et al., 1983FRANKIE, GW., HABER, WA., OPLER, PA. and BAWA, KS., 1983. Characteristics and organization of the large bee pollination system in the Costa Rican dry forest. In JONES, CE. and LITTLE, RJ. (Eds.). Handboock of experimental pollination biology. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. p. 411-447.; Bawa et al., 1985bBAWA, KS., BULLOCK, SH., PERRY, DR., COVILLE, RE. and GRAYUM, MH., 1985b. Reproductive biology of tropical lowland rain forest trees. II. Pollination systems. American Journal of Botany, vol. 72, p. 345-356.; Morellato, 1991MORELLATO, LPC., 1991. Estudo da fenologia de árvores, arbustos e lianas de uma floresta semidecídua no sudeste do Brasil. São Paulo: Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Ph.D. Thesis.; Ramírez, 1989RAMÍREZ, N., 1989. Biologia de polinización en una comunidad arbustiva tropical de la Alta Guayana Venezolana. Biotropica, vol. 21, p. 319-330. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2388282

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2388282...

, 2004). The largest numbers of melittophilous species among trees and vines was reported in semi-deciduous forests in southeastern Brazil (Morellato, 1991MORELLATO, LPC., 1991. Estudo da fenologia de árvores, arbustos e lianas de uma floresta semidecídua no sudeste do Brasil. São Paulo: Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Ph.D. Thesis.), and melittophily seems to be very prevalent among trees and vines in Neotropical environments (Johnson and Steiner, 2000JOHNSON, SD. and STEINER, KE., 2000. Generalization versus specialization in plant pollination systems. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, vol. 15, p. 140-143. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(99)01811-X

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(99)...

). According to Frankie et al. (1983)FRANKIE, GW., HABER, WA., OPLER, PA. and BAWA, KS., 1983. Characteristics and organization of the large bee pollination system in the Costa Rican dry forest. In JONES, CE. and LITTLE, RJ. (Eds.). Handboock of experimental pollination biology. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. p. 411-447., melittophily is most common among arboreal species (when considering only large bees as pollinators) and is generally less frequently observed in shrubs and herbs.

Flowering of phalenophilous species during the rainy season seems to be related to the reproductive cycle of the moths. A similar relationship was observed by Haber and Frankie (1989)HABER, WA. and FRANKIE, GW., 1989. A tropical hawk-moth community: Costa Rican dry forest Sphingidae. Biotropica, vol. 21, p. 155-172. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2388706

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2388706...

between sphingids and the sphingophilous plants in dry forests in Costa Rica. Seasonal flowering patterns were also observed in phalenophilous species by Parra-Tabla and Bullock (2002)PARRA-TABLA, V. and BULLOCK, SH. 2002. La polinización en la selva tropical de Chamela. In NOGUEIRA, FA., VEGA RIVERA, JHA., GARCIA ALDRETE, N. and QUESADA AVENDAÑO, M. (Eds.). Historia Natural de Chamela. Instituto de Biologia, UNAM. p. 499-515. (with a flowering peak during the transitional period between the dry and the rainy season), and by Amorim and Oliveira (2006)AMORIM, FW. and OLIVEIRA, PE., 2006. Estrutura sexual e ecologia reprodutiva de Amaioua guianensis Aubl. (Rubiaceae), uma espécie dióica de formações florestais de cerrado. Revista Brasileira de Botânica, vol. 29, p. 353-362. with some species of Rubiaceae. Parra-Tabla and Bullock (2002)PARRA-TABLA, V. and BULLOCK, SH. 2002. La polinización en la selva tropical de Chamela. In NOGUEIRA, FA., VEGA RIVERA, JHA., GARCIA ALDRETE, N. and QUESADA AVENDAÑO, M. (Eds.). Historia Natural de Chamela. Instituto de Biologia, UNAM. p. 499-515. reported a relationship between the presence of sphingids and the flowering period of plant species pollinated by these moths in a tropical forest in Mexico. According to Faegri and Pijl (1979)FAEGRI, K. and PIJL, L., 1979. The principles of pollination ecology. London: Pergamin Press., there is evidence of convergence between the life cycle of these insects and the flowering period of the plants that they pollinate. The seasonal flowering demonstrated by phalenophilous species in the Caatinga community examined here represents an important source of food for these insects, and certainly strongly influences their life cycles.

The high proportion of the chiropterophilous species (11%) observed reinforces the importance of this pollination system for Caatinga vegetation. Likewise, Machado and Lopes (2004)MACHADO, IC. and LOPES, AV., 2004. Floral traits and pollination systems in the Caatinga, a Brazilian Tropical Dry Forest. Annals of Botany, vol. 94, p. 365-376. PMid:15286010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152...

reported that 13.1% of the plant species in three areas of Caatinga vegetation in Pernambuco were pollinated by bats. The proportions of chiropterophilous species in other tropical environments are, however, usually much lower, ranging from 1.8 to 3.0% in the Cerrado (Oliveira and Gibbs, 2000OLIVEIRA, PE. and GIBBS, PE., 2000. Reproductive biology of woody plants in a cerrado community of central Brazil. Flora, vol. 195, p. 311-329.; Silberbauer-Gottsberger and Gottsberger, 1988SILBERBAUER-GOTTSBERGER, I. and GOTTSBERGER, G., 1988. A polinização de plantas do cerrado. Revista Brasileira de Biologia = Brazilian Journal of Biology, vol. 48, p. 651-663.) and 3.0% in humid forests (Bawa et al., 1985bBAWA, KS., BULLOCK, SH., PERRY, DR., COVILLE, RE. and GRAYUM, MH., 1985b. Reproductive biology of tropical lowland rain forest trees. II. Pollination systems. American Journal of Botany, vol. 72, p. 345-356.).

The discontinuous flowering peaks observed with chiropterophilous species, with few flowers per night, favours intra-specific pollen transfer and at the same time reduces competition for pollinators and thus the inter-specific transfer of pollen (see Feinsinger et al., 1987FEINSINGER, P., BEACH, JH., LINHART, YB., BUSBY, WH. and MURRAY, G., 1987. Disturbance, pollinator predictably, and pollination success among Costa Rica cloud forest plants. Colgy, vol. 68, p. 1294-1305.; Morellato, 1991MORELLATO, LPC., 1991. Estudo da fenologia de árvores, arbustos e lianas de uma floresta semidecídua no sudeste do Brasil. São Paulo: Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Ph.D. Thesis.; Ramírez, 2004; Stiles, 1977STILES, FG., 1977. Coadapted competitors: the flowering seasons of hummingbird-pollinated plants in a tropical forest. Science, vol. 198, p. 1177-1178. PMid:17818936. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.198.4322.1177

http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.198.43...

). The offering of sequential floral resources also helps to maintain biotic pollen vectors like(bee, birds and bats in the Caatinga.

The availability of resources to sustain bat populations throughout the year was also observed in semi-deciduous tropical forests by Morellato (1991)MORELLATO, LPC., 1991. Estudo da fenologia de árvores, arbustos e lianas de uma floresta semidecídua no sudeste do Brasil. São Paulo: Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Ph.D. Thesis., although this author did not observe sequential flowering. The apparent absence of continuous flowering among chiropterophilous species in this ecosystem may be compensated by the local availability of fruits, as a majority of the bats that visit flowers are also frugivorous.

The dry-season flowering peak of the three ornitophilous species provides resources at a time when the overall numbers of nectar-producing flowers are ebbing. According to Machado and Lopes (2004)MACHADO, IC. and LOPES, AV., 2004. Floral traits and pollination systems in the Caatinga, a Brazilian Tropical Dry Forest. Annals of Botany, vol. 94, p. 365-376. PMid:15286010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152...

, some hummingbirds appear to have generalist behaviour in Caatinga environments that allows them to exploit other plants with other pollination syndromes when few ornitophilous species are available. These authors also reported a great species richness of hummingbirds in Caatinga regions during the dry season. The difference found in the habits can be explained by absence of more specialised syndromes, ornitophilous in the tree and shrub.

Anemophily, which was observed only in two species of Croton, has already been noted in other species of this same genus (Dominguez and Bullock, 1989DOMINGUEZ, CA. and BULLOCK, SH., 1989. La reproducción de Croton suberosus (Euphorbiaceae) en luz y sombra. Revista de Biología Tropical, vol. 37, p. 1-10. PMid:2690200.; Parra-Tabla and Bullock, 2002PARRA-TABLA, V. and BULLOCK, SH. 2002. La polinización en la selva tropical de Chamela. In NOGUEIRA, FA., VEGA RIVERA, JHA., GARCIA ALDRETE, N. and QUESADA AVENDAÑO, M. (Eds.). Historia Natural de Chamela. Instituto de Biologia, UNAM. p. 499-515.; Passos, 1995PASSOS, L. 1995. A polinização pelo vento. In LEITÃO-FILHO, HF. and MORELLATO, LP. (Orgs.). Ecologia e preservação de uma floresta tropical urbana: reserva de Santa Genebra. Campinas: Editora da Unicamp. p. 54-56.). In addition to wind-mediated pollination, Reddi and Reddi (1985)REDDI, EUB. and REDDI, CS., 1985. Wind and insect pollination in monoecious and dioecious species of Euphorbiaceae. Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences: Plant Sciences, vol. 51, p. 468-482. and Passos (1995)PASSOS, L. 1995. A polinização pelo vento. In LEITÃO-FILHO, HF. and MORELLATO, LP. (Orgs.). Ecologia e preservação de uma floresta tropical urbana: reserva de Santa Genebra. Campinas: Editora da Unicamp. p. 54-56. also observed ambophily in other species of Croton. Anemophily seems to be a secondary pollination method for the Croton species in the Caatinga region examined, as numerous bees were observed visiting flowers on these plants.

4.2. Floral resources

Nectar is the dominant floral resource in Caatinga regions (Machado and Lopes, 2004MACHADO, IC. and LOPES, AV., 2004. Floral traits and pollination systems in the Caatinga, a Brazilian Tropical Dry Forest. Annals of Botany, vol. 94, p. 365-376. PMid:15286010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152...

) as well as in numerous other ecosystems (e.g. Oliveira and Gibbs, 2000OLIVEIRA, PE. and GIBBS, PE., 2000. Reproductive biology of woody plants in a cerrado community of central Brazil. Flora, vol. 195, p. 311-329.; Percival, 1974PERCIVAL, M., 1974. Floral ecology of costal scrub in southeast Jamaica. Biotropica, vol. 6, p. 104-129. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2989824

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2989824...

; Ramírez et al., 1990RAMÍREZ, N., GIL, C., HOKCHE, O., SERES, A. and BRITTO, Y. 1990. Biologia floral de uma comunidade arbustiva tropical em la Guayannna Venezolana. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, vol. 77, p. 1260-271. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2399554

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2399554...

; Silberbauer-Gottsberger and Gottsberger, 1988SILBERBAUER-GOTTSBERGER, I. and GOTTSBERGER, G., 1988. A polinização de plantas do cerrado. Revista Brasileira de Biologia = Brazilian Journal of Biology, vol. 48, p. 651-663.).

The proportion of flowers observed offering nectar and pollen in the present study was greater than that reported by Machado and Lopes (2004)MACHADO, IC. and LOPES, AV., 2004. Floral traits and pollination systems in the Caatinga, a Brazilian Tropical Dry Forest. Annals of Botany, vol. 94, p. 365-376. PMid:15286010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152...

in another Caatinga area, but is similar to that observed in other regions (Ramírez et al., 1990RAMÍREZ, N., GIL, C., HOKCHE, O., SERES, A. and BRITTO, Y. 1990. Biologia floral de uma comunidade arbustiva tropical em la Guayannna Venezolana. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, vol. 77, p. 1260-271. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2399554

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2399554...

; Silberbauer-Gottsberger and Gottsberger, 1988SILBERBAUER-GOTTSBERGER, I. and GOTTSBERGER, G., 1988. A polinização de plantas do cerrado. Revista Brasileira de Biologia = Brazilian Journal of Biology, vol. 48, p. 651-663.).

The large proportion of tree and shrub species producing only nectar is congruent with the melittophilous pollination system of these species. The differences found in nectar production during the years of the study are probably related to rainfall rates (greater in the second year), which resulted in a larger number of species flowering (t = 1.827; p = 0.05).

The observation that only a single species of vine offered oil as a floral resource may be related to the fact that the production of this floral reward is restricted to only two Caatinga families (Scrophulariaceae and Malpighiaceae) (Aguiar et al., 2003AGUIAR, CML., ZANELLA, FCV., MARTINS, CF. and CARVALHO, CAL., 2003. Plantas visitadas por Centris ssp. (Hymenoptera- Apoidae) na caatinga para obtenção de recursos florais. Neotropical Entomology, vol. 32, p. 247-259. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1519-566X2003000200009

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1519-566X2003...

; Machado et al., 2002MACHADO, ICS., VOGEL, S. and LOPES, AV., 2002. Pollination of Angelonia cornigera Hook. (Scrophulariaceae) by long-legged oil-collecting bees in NE Brazil. Plant Biology, vol. 4, p. 352-359. http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-2002-32325

http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-2002-32325...

).

In summary, the Caatinga vegetation community examined showed a temporal ( dry and rainy season) distribution of distinct pollination syndromes and of their floral resources among the different plant habits (trees, shrubs, herbs, and vines). These patterns influence the dynamics of this ecosystem and could guarantee the distribution of the various floral resources within the community with a certain uniformity throughout the year.

Acknowledgements

We thank Eunice Braz (in memoriam) for permission to carry out this study on her property; Roberto Lima (UFPB) for his help with the fieldwork; Itamar Barbosa de Lima (UFPB) for his help with species identifications; Patrícia Morellato (UNESP), Paulo Eugênio Oliveira (UFU), and Francisca Soares Araújo (UFC) for their suggestions for the manuscript. We are also grateful to CNPq for financial support through the “Programa Ecológico de Longa Duração-PELD” and for the doctoral and research grants to the first and second author, respectively.

References

- AGUIAR, CML., ZANELLA, FCV., MARTINS, CF. and CARVALHO, CAL., 2003. Plantas visitadas por Centris ssp. (Hymenoptera- Apoidae) na caatinga para obtenção de recursos florais. Neotropical Entomology, vol. 32, p. 247-259. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1519-566X2003000200009

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1519-566X2003000200009 - AMORIM, FW. and OLIVEIRA, PE., 2006. Estrutura sexual e ecologia reprodutiva de Amaioua guianensis Aubl. (Rubiaceae), uma espécie dióica de formações florestais de cerrado. Revista Brasileira de Botânica, vol. 29, p. 353-362.

- ANDRADE-LIMA, D., 1981. The caatinga's dominium. Revista Brasileira de Botânica, vol. 4, p. 149-53.

- ARIZMENDI, MC. and ORNELAS, JF., 1990. Hummingbirds and their floral resources in a tropical dry Forest in México. Biotropica, vol. 22, p. 172-180. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2388410

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2388410 - BAKER, HG., 1959. Reproductive methods as factors in the speciation in flowering plants. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology, vol. 24, p. 177-191. PMid:13796002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/SQB.1959.024.01.019

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/SQB.1959.024.01.019 - -, 1990. Plant-pollinator interactions in tropical rain forests. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, vol. 21, p. 399-422. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.21.110190.002151

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.21.110190.002151 - BAWA, KS., PERRY, DR. and BEACH, JH., 1985a. Reproductive biology of tropical lowland rain forest trees. I. Sexual systems and incompatibility mechanisms. American Journal of Botany, vol. 72, p. 331-343. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2443526

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2443526 - BAWA, KS., BULLOCK, SH., PERRY, DR., COVILLE, RE. and GRAYUM, MH., 1985b. Reproductive biology of tropical lowland rain forest trees. II. Pollination systems. American Journal of Botany, vol. 72, p. 345-356.

- BULLOCK, SH., 1985. Breeding systems in the flora of a tropical deciduos forest in Mexico. Biotropica, vol. 17, p. 287-301. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2388591

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2388591 - DAFNI, A., and KEVAN, PG., 1997. Flower size and shape: implications in pollination. Israel Journal of Plant Sciences, vol. 45, p. 201-211. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07929978.1997.10676684

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07929978.1997.10676684 - DOMINGUEZ, CA. and BULLOCK, SH., 1989. La reproducción de Croton suberosus (Euphorbiaceae) en luz y sombra. Revista de Biología Tropical, vol. 37, p. 1-10. PMid:2690200.

- FAEGRI, K. and PIJL, L., 1979. The principles of pollination ecology. London: Pergamin Press.

- FRANKIE, GW., BAKER, HG. and OPLER, PA., 1974. Comparative phonological studies of trees in tropical lowland wet and dry forest sites of Costa Rica. Journal of Ecology, vol. 62, p. 881-913. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2258961

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2258961 - FRANKIE, GW., HABER, WA., OPLER, PA. and BAWA, KS., 1983. Characteristics and organization of the large bee pollination system in the Costa Rican dry forest. In JONES, CE. and LITTLE, RJ. (Eds.). Handboock of experimental pollination biology. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. p. 411-447.

- FREEMAN, DC., COUST, JL., EL-KEBLAWI, A., MIGLIA, KJ. and McARTHUR, ED., 1997. Sexual specialization and inbreeding avoidance in the evolution of dioecy. Botanical Review, vol. 63, p. 65-92.

- FEINSINGER, P., BEACH, JH., LINHART, YB., BUSBY, WH. and MURRAY, G., 1987. Disturbance, pollinator predictably, and pollination success among Costa Rica cloud forest plants. Colgy, vol. 68, p. 1294-1305.

- FLORES, S. and SCHEMSKE, DW., 1984. Dioecy and monoecy in the flora of Puerto Rico and Virgin Islands: ecological correlates. Biotropica, vol. 16, p. 132-139. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2387845

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2387845 - GENTRY, A., 1995. Diversity and floristic composition of neotropical dry forest. In BULLOCK, SH., MOONEY, HA. and MEDINA, E. (Eds.). Seasonally dry tropical forest. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 146-194.

- GRANT, KA., 1966. A hypothesis concerning the prevalence of red colouration in California hummingbird flowers. American Naturalist, vol. 100, p. 85-97. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/282403

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/282403 - HABER, WA. and FRANKIE, GW., 1989. A tropical hawk-moth community: Costa Rican dry forest Sphingidae. Biotropica, vol. 21, p. 155-172. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2388706

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2388706 - HEITHAUS, ER., 1974. The role of plant-pollinator interactions in determining community structure. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, vol. 61, p. 675-691. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2395023

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2395023 - JANZEN, DH., 1967. Synchronization of sexual reproduction of trees within the dry season in Central America. Evolution, vol. 21, p. 620-637. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2406621

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2406621 - JOHNSON, SD. and STEINER, KE., 2000. Generalization versus specialization in plant pollination systems. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, vol. 15, p. 140-143. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(99)01811-X

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(99)01811-X - KRESS, WJ. and BEACH, JH., 1994. Flowering plant reproductive systems. In McDADE, LA., BAWA, KS., HESPENHEIDE, H. and HARTSHORN, G. (Eds.). La Selva: ecology and natural history of a neotropical rain forest. University of Chicago: Press in Chicago. p. 161-182.

- LEAL, FC., LOPES, AV. and MACHADO, IC., 2006. Polinização por beija-flores em uma área de Caatinga no Município de Floresta, Pernambuco, Nordeste do Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Botânica, vol. 29, p. 379-389.

- LEITE, AV. and MACHADO, IC., 2010. Reproductive biology of woody species in Caatinga, a dry forest of northeastern Brazil. Journal of Arid Environments, vol. 74, p. 1374-1380. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2010.05.029

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2010.05.029 - LIMA, IB., 2004. Levantamento florístico da reserva particular do patrimônio natural Fazenda Almas, São José dos Cordeiros -PB. Universidade Federal da Paraíba. Monografia de Graduação.

- MACHADO, IC., 1990. Biologia floral de espécies de caatinga no Município de Alagoinha- PE. São Paulo: Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Ph.D. Thesis.

- MACHADO, IC. and LOPES, AV., 2004. Floral traits and pollination systems in the Caatinga, a Brazilian Tropical Dry Forest. Annals of Botany, vol. 94, p. 365-376. PMid:15286010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aob/mch152 - MACHADO, IC., LOPES, AV. and SAZIMA, M., 2006. Plant sexual systems and review of the breeding system studies in the Caatinga, a Brazilian Tropical Dry Forest. Annals of Botany, vol. 97, p. 277-287.

- MACHADO, ICS., VOGEL, S. and LOPES, AV., 2002. Pollination of Angelonia cornigera Hook. (Scrophulariaceae) by long-legged oil-collecting bees in NE Brazil. Plant Biology, vol. 4, p. 352-359. http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-2002-32325

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-2002-32325 - MANTOVANI, W. and MARTINS, FR., 1988. Variações fenológicas do cerrado da reserva Biológica de Mogi Guaçu, Estado de São Paulo. Revista Brasileira de Botânica, vol. 11, p. 101-112.

- MARTINS, FQ. and BATALHA, MA., 2006. Pollination systems and floral traits in Cerrado woody species of the upper Taquari Region (Central Brazil). Brazilian Journal of Biology, vol. 66, p. 543-552. PMid:16862310. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1519-69842006000300021

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1519-69842006000300021 - MATALLANA, G., WENDT, T., ARAÚJO, DSD. and SCARANO, FR., 2005. High abundance of dioecious plants in tropical coastal vegetation. American Journal of Botany, vol. 92, p. 1513-1519. PMid:21646169. http://dx.doi.org/10.3732/ajb.92.9.1513

» http://dx.doi.org/10.3732/ajb.92.9.1513 - MOMOSE, KT., YUMOTO, T., NAGAMITSU, T., NAGAMASU, H., SAKAI, RD., HARRINSIN, RD., ITIOKA, T., HAMID, AA. and INQUE, T., 1998. Pollination biology in a lowland dipterocarp forest in Sarawak, Malaysia. I. Characteristics of the plant-pollinator community in a lowland dipterocarp Forest. American Journal of Botany, vol. 85, p. 1477-1501. PMid:21684899. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2446404

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2446404 - MORELLATO, LPC., 1991. Estudo da fenologia de árvores, arbustos e lianas de uma floresta semidecídua no sudeste do Brasil. São Paulo: Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Ph.D. Thesis.

- -, 2003. South America. In SCHWARTZ, MD. (Ed.). Phenology: An Integrative Environmental Science (Tasks for Vegetation Science) (Hardcover). Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 75-92.

- MORELLATO, LPC., RODRIGUES, RR., LEITÃO-FILHO, HF. and JOLY, CA., 1989. Estudo comparativo da fenologia de espécies arbóreas de floresta de altitude e floresta mesófila semidecídua na Serra do Japi, Jundiaí, SP. Revista Brasileira de Botânica, vol. 12, p. 85-98.

- MUCHHALA, N. and JARRIN-V, P., 2002. Flower visitation by bats in cloud forests of Western Ecuador. Biotropica, vol. 34, p. 387-395. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7429.2002.tb00552.x

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7429.2002.tb00552.x - OLIVEIRA, PE. and GIBBS, PE., 2000. Reproductive biology of woody plants in a cerrado community of central Brazil. Flora, vol. 195, p. 311-329.

- OLIVEIRA, PE., GIBBS, PE. and BARBOSA, AA., 2004. Moth pollination of woody species in the cerrados of central Brazil: a case of so much owed to so few? Plant Systematics and Evolution, vol. 245, p. 41-54.

- ORMOND, WT., PINHEIRO, MCB., LIMA, AH., CORREIA, MCR. and PIMENTA, ML., 1993. Estudo das recompensas florais das plantas de restinga da Maricá – Itaipaçu, RJ. I – Nectaríferas. Bradea, vol. 6, p. 179-195.

- PARAÍBA. Governo do Estado da Paraíba and Universidade Federal da Paraíba - UFPB, 1989. Atlas Geográfico do Estado da Paraíba. João Pessoa: Grafset.

- PARRA-TABLA, V. and BULLOCK, SH. 2002. La polinización en la selva tropical de Chamela. In NOGUEIRA, FA., VEGA RIVERA, JHA., GARCIA ALDRETE, N. and QUESADA AVENDAÑO, M. (Eds.). Historia Natural de Chamela. Instituto de Biologia, UNAM. p. 499-515.

- PASSOS, L. 1995. A polinização pelo vento. In LEITÃO-FILHO, HF. and MORELLATO, LP. (Orgs.). Ecologia e preservação de uma floresta tropical urbana: reserva de Santa Genebra. Campinas: Editora da Unicamp. p. 54-56.

- PRADO, DE., 2003. As caatingas da América do Sul. In LEAL, IR., TABARELLI, M. and SILVA, JMC. (Orgs.). Ecologia e Conservação da Caatinga. Recife: Editora UFPE. p. 3-74.

- PERCIVAL, M., 1974. Floral ecology of costal scrub in southeast Jamaica. Biotropica, vol. 6, p. 104-129. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2989824

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2989824 - QUIRINO, ZGM., 2006. Fenologia, síndromes de polinização e dispersão e recursos florais de especies vegetais do Cariri Paraibano. Recife: Universidade Federal de Pernambuco. Ph.D. Thesis.

- RAMÍREZ, N., 1989. Biologia de polinización en una comunidad arbustiva tropical de la Alta Guayana Venezolana. Biotropica, vol. 21, p. 319-330. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2388282

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2388282 - -, 2004. Pollination specialization and time of pollination on a tropical Venezuelan plain: variations in time and space. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, vol. 145, p. 1-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8339.2004.00181.x

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8339.2004.00181.x - RAMÍREZ, N., GIL, C., HOKCHE, O., SERES, A. and BRITTO, Y. 1990. Biologia floral de uma comunidade arbustiva tropical em la Guayannna Venezolana. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, vol. 77, p. 1260-271. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2399554

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2399554 - REDDI, EUB. and REDDI, CS., 1985. Wind and insect pollination in monoecious and dioecious species of Euphorbiaceae. Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences: Plant Sciences, vol. 51, p. 468-482.

- RICHARDS, AJ., 1986. Plant breeding systems. London: Allen & Uwnwin.

- RODAL, MJN. and SAMPAIO, EVSB., 2002. A vegetação do bioma caatinga. In SAMPAIO, EVSB., GIULIETTI, AM., VIRGÍNIO, J. and ROJAS, CFLG. (Eds.). Vegetação e flora da caatinga. Recife: APNE/CNIP. p. 11-24.

- SILBERBAUER-GOTTSBERGER, I. and GOTTSBERGER, G., 1988. A polinização de plantas do cerrado. Revista Brasileira de Biologia = Brazilian Journal of Biology, vol. 48, p. 651-663.

- SILVA, AG., GUEDES-BRUNI, RR. and LIMA, HM., 1997. Sistemas sexuais e recursos florais do componente arbustivo-arbóreo em mata preservada na Reserva Ecológica de Macaé de Cima. In LIMA, HC. and GUEDES-BRUNI, RR. (Eds.). Serra de Macaé de Cima: diversidade florística e conservação em mata atlântica. Rio de Janeiro: Jardim Botânico. p. 182-211.

- STILES, FG., 1977. Coadapted competitors: the flowering seasons of hummingbird-pollinated plants in a tropical forest. Science, vol. 198, p. 1177-1178. PMid:17818936. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.198.4322.1177

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.198.4322.1177

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

Feb 2014

History

-

Received

21 Aug 2012 -

Accepted

27 Dec 2012