Abstract

Local knowledge of biodiversity has been applied in support of research focused on utilizing and management of natural resources and promotion of conservation. Among these resources, Pequi (Caryocar brasiliense Cambess.) is important as a source of income and food for communities living in the Cerrado biome. In Pontinha, a “quilombola” community, which is located in the central region of State of Minas Gerais, Brazil, an ethnoecological study about Pequi was conducted to support initiatives for generating income for this community. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews, participant observation, and crossing. The most relevant uses of Pequi were family food (97%), soap production (67%), oil production (37%), medical treatments (17%), and trade (3%). Bees were the floral visitors with the highest Salience Index (S=0.639). Among frugivores that feed on unfallen fruits, birds showed a higher Salience (S=0.359) and among frugivores who use fallen fruits insects were the most important (S=0.574). Borers (folivorous caterpillars) that attack trunks and roots were the most common pests cited. According to the respondents, young individuals of Pequi are the most affected by fire due to their smaller size and thinner bark. Recognition of the cultural and ecological importance of Pequi has mobilized the community, which has shown interest in incorporating this species as an alternative source of income.

Keywords:

Cerrado; traditional communities; ethnoecology; income

Resumo

O conhecimento local acerca da biodiversidade vem sendo utilizado em pesquisas voltadas ao uso e manejo de recursos naturais aliados à conservação. Entre estes recursos, destaca-se o Pequi (Caryocar brasiliense Cambess.) devido à sua importância econômica e alimentar para comunidades que vivem no Cerrado. No quilombo de Pontinha, localizado na região central do estado de Minas Gerais, um estudo etnoecológico sobre o Pequi foi desenvolvido, a fim de subsidiar iniciativas de geração de trabalho e renda para esta comunidade. Informações foram obtidas por meio de entrevistas semiestruturadas, observação participante e travessia. Alimentação familiar (97%), produção de sabão (67%), produção de óleo (37%), tratamento medicinal (17%) e comércio (3%) foram os principais usos do Pequi citados pelos comunitários. Abelhas foram os visitantes florais com maior Índice de Saliência (S=0,639). Dentre os frugívoros que se alimentam de frutos não caídos, as aves apresentaram maior Saliência (S=0,359) e os insetos foram os mais importantes frugívoros entre os que utilizam frutos caídos (S=0,574). Brocas, lagartas folívoras e que atacam troncos e raízes foram as pragas mais citadas. Os indivíduos jovens de Pequi são, segundo os entrevistados, os mais afetados pelo fogo devido ao menor porte e por ter a casca menos espessa. O reconhecimento da importância cultural e ecológica do Pequi tem mobilizado a comunidade, que demonstra interesse em fazer dessa espécie uma alternativa de renda.

Palavras-chave:

Cerrado; comunidades tradicionais; etnoecologia; renda

1 Introduction

The study area is located in the Cerrado biodiversity hotspot, a biome that covers approximately 22% of Brazil (Ratter, 1997RATTER, J., 1997. The Brazilian Cerrado vegetation and threats to its biodiversity. Annals of Botany, vol. 80, no. 3, pp. 223-230. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/anbo.1997.0469.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/anbo.1997.0469...

; Mittermeier et al., 2004Mittermeier, R.A., Gil, P.R., Hoffman, M., Pilgrim, J., Brooks, T., Mittermeier, C.G., Lamoreux, J. and Fonseca, G.A.B., 2004. Hotspots revisited. Mexico: Cemex. 392 p.). In addition to its biological importance, Cerrado is home to a diverse range of traditional communities that embody great knowledge about its resources. Indigenous peoples, “quilombolas”, “vazanteiros”, “retireiros”, “geraizeiros” and woman breakers (“quebradeiras de coco”) are the main ethnically differentiated groups in this biome (Barbosa et al., 1990Barbosa, A.S., Ribeiro, M.B. and Schmitz, P.I., 1990. Cultura e ambiente em áreas do sudoeste de Goiás. In: M.N. PINTO, ed. Cerrado caracterização, ocupação e perspectivas. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, pp. 67-100.; Brasil, 2004BRASIL. Ministério do Meio Ambiente – MMA. Núcleo dos Biomas Cerrado e Pantanal, 2004. Programa Nacional de Conservação e Uso Sustentável do Bioma Cerrado. Brasília. 67 p.). These and other rural communities obtain part of their income through networks of collection, processing, and trade of sociobiodiversity products (Pozo, 1997POZO, O.V.C., 1997. O pequi (Caryocar brasiliense): uma alternativa para o desenvolvimento sustentável do cerrado no Norte de Minas Gerais. Lavras: Universidade Federal de Lavras, 100 p. Masters Dissertation.; Silva and Tubaldini, 2013Silva, M.N.S. and TUBALDINI, M.A.S., 2013. O ouro do cerrado: a dinâmica do extrativismo do pequi no norte de Minas Gerais. Revista Geoaraguaia, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 293-317.).

The Pequi tree (Caryocar brasiliense Cambess., Caryocaraceae) (Medeiros and Amorim, 2015Medeiros, H. and Amorim, A.M.A., 2015 [viewed 20 January 2015]. . In: CaryocaraceaeJARDIM BOTÂNICO DO RIO DE JANEIRO – JBRJ. Lista de espécies da flora do Brasil [online]. Rio de Janeiro: JBRJ. Available from: http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/jabot/floradobrasil/FB6688

http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/jabot/f...

) has great economic and subsistence values for many communities living in the Cerrado (Araujo, 1995AraUjo, F.D., 1995. A review of (Caryocaraceae): an economically valuable species of the central brazilian cerrados. Caryocar brasilienseEconomic Botany, vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 40-48. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02862276.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02862276...

; Vieira et al., 2006Vieira, R.F., Costa, T.S.A., Silva, D.B., Ferreira, F.R. and Sano, S.M., 2006. Frutas nativas da região centro‐oeste. Brasília: Embrapa Recursos Genéticos e Biotecnologia. 320 p.; Sano et al., 2008Sano, S.M., Almeida, S.P. and Ribeiro, J.F., 2008. Cerrado: ecologia e flora. Brasília: EMBRAPA. 1279 p. Informação Tecnológica, vol. 1.; Afonso and Ângelo, 2009Afonso, S.R. and Ângelo, H., 2009. Mercado de produtos florestais não madeiros do cerrado brasileiro. Ciência Florestal, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 315-326. http://dx.doi.org/10.5902/19805098887.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5902/19805098887...

; Assunção, 2012Assunção, P.E.V., 2012. Extrativismo e comercialização de pequi (. Caryocar brasiliense Camb.) em duas cidades no estado de GoiásRevista Economica, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 17-26., Santos et al., 2013Santos, F.S., Santos, R.F., Dias, P.P., Zanão-Junior, L.A. and Tomassoni, F., 2013. A cultura do Pequi (Caryocar brasiliense Camb.). Acta Iguazu, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 46-57.). Pequi fruits can be consumed fresh or as jams, jellies, liqueurs, creams and oils (Germano et al., 2007Germano, J.N., SILVA, R.L.A. and SANTOS, E.M., 2007. Estudo etnobotânico das plantas medicinais do cerrado do estado de Mato Grosso. Revista Brasileira de Plantas Medicinais, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 23-31.; Carvalho, 2008Carvalho, P.E.R., 2008. Espécies arbóreas brasileiras. Brasília: Embrapa Informação Tecnológica. 593 p.) and their leaves are also used in folk medicine for treating respiratory diseases (Rodrigues and Carvalho, 2001Rodrigues, V E.G. and CARVALHO, D.A., 2001. Levantamento etnobotânico de plantas medicinais no domínio do cerrado na região do Alto Rio Grande, Minas Gerais. Ciência e Agrotecnologia, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 102-123.; Germano et al., 2007Germano, J.N., SILVA, R.L.A. and SANTOS, E.M., 2007. Estudo etnobotânico das plantas medicinais do cerrado do estado de Mato Grosso. Revista Brasileira de Plantas Medicinais, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 23-31.; Monteles and Pinheiro, 2007Monteles, R. and Pinheiro, C.U.B., 2007. Plantas medicinais em um quilombo maranhense: uma perspectiva etnobotânica. Revista de Biologia e Ciências da Terra, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 1-11.) or manufacturing cosmetics products (Oliveira et al., 2008Oliveira, M.E.B., Guerra, N.B., Barros, L.M. and Alves, R.E., 2008. Aspectos agronômicos e de qualidade do pequi. Fortaleza: Embrapa Agroindústria Tropical. 32 p. Documentos, no. 113.; Pianovski et al., 2008Pianovski, A.R., Vilela, A.F.G., Silva, A.A.S., Lima, C.G., Silva, K.K., Carvalho, V.F.M., Musis, C.R., MACHADO, S.R.P. and FERRARI, M., 2008. Uso do óleo de pequi ( ) em emulsões cosméticas: desenvolvimento e avaliação da estabilidade física. CaryocarbrasilienseRevista Brasileira de Ciências Farmacêuticas, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 249-259.). In addition to the ethnobotanic and ethnoecological investigations with C. brasiliense, other studies show anti-inflammatory and antioxidants properties of the oil extracted from the Pequi pulp (Roesler et al., 2008Roesler, R., Catharino, R.R., Malta, L.G., Eberlin, M.N. and Pastore, G., 2008. Antioxidant activity of Caryocar brasiliense (pequi) and characterization of components by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Food Chemistry, vol. 110, no. 3, pp. 711-717. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.02.048.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.200...

; Aquino et al., 2011Aquino, L.P., Borges, S.V., Queiroz, F., Antoniassi, R. and Cirillo, M.A., 2011. Extraction of oil from pequi fruit (Caryocar Brasiliense, Camb.) using several solvents and their mixtures. Grasas y Aceites, vol. 62, no. 3, pp. 245-252. http://dx.doi.org/10.3989/gya.091010.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3989/gya.091010...

).

In northern Brazil the species Caryocar villosum (Albu.) Pers., popularly known as Piquiá, has a wide range of culinary, commercial, and medicinal uses, being indicated for treating inflammatory and respiratory diseases (Rios et al., 2001Rios, M., Martins-Da-Silva, R.C.V., Sabogal, C., Martins, J., Silva, R.N., Brito, R.R., Brito, I.M., Brito, M.F.C., Silva, J.R. and Ribeiro, R.T., 2001. Benefícios das plantas da capoeira para a comunidade de Benjamin Constant, Pará, Amazônia Brasileira. Belém: CIFOR. 54 p.). In this sense, studies in Tapajós National Forest showed analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties of this species, both recognized by the forest dwellers and verified by pharmacological investigations undertaken in this protected area (Galuppo, 2004Galuppo, S.C., 2004. Documentação do uso e da valorização do óleo do Piquiá (Caryocar villosum) e do leite do Amapá-doce (Brosimum parinarioides) para a Comunidade de Piquiatuba, Floresta Nacional do Tapajós: estudos físicos, químicos, fitoquímicos e famacológicos. Belém: Universidade Federal Rural da Amazônia, 108 p. Masters Dissertation.). Caryocar coreaceum Wittm., another species of northeastern Brazil, is used for culinary, economic, and medicinal purposes (Gonçalves, 2008Gonçalves, C.U., 2008. Os pequizeiros da Chapada do Araripe. Revista de Geografia., vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 88-103.; Saraiva et al., 2011Saraiva, R.A., Araruna, M.K.A., Oliveira, R.C., Menezes, K.D.P., Leite, G.O., Kerntopf, M.R., Costa, J.G.M., Rocha, J.B.T., Tomé, A.R., Campos, A.R. and Menezes, I.R.A., 2011. Topical anti-inflammatory effect of Wittm.(Caryocaraceae) fruit pulp fixed oil on mice ear edema induced by different irritant agents. Caryocar coriaceumJournal of Ethnopharmacology, vol. 136, no. 3, pp. 504-510. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2010.07.002. PMid:20621180.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2010.07....

, Sousa-Júnior et al., 2013Sousa JÚNIOR, J.R., Albuquerque, U.P. and Peroni, N., 2013. Traditional Knowledge and Management of Wittm. (Pequi) in the Brazilian Savanna, Northeastern Brazil. Caryocar coriaceumEconomic Botany, vol. 67, no. 3, pp. 225-233. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12231-013-9241-8.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12231-013-924...

). In Chapada do Araripe, (Ceará State), in addition to the uses already mentioned, the fruit shell of C. coreaceum is used as animal fodder (Sousa-Júnior et al., 2013Sousa JÚNIOR, J.R., Albuquerque, U.P. and Peroni, N., 2013. Traditional Knowledge and Management of Wittm. (Pequi) in the Brazilian Savanna, Northeastern Brazil. Caryocar coriaceumEconomic Botany, vol. 67, no. 3, pp. 225-233. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12231-013-9241-8.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12231-013-924...

).

Many traditional communities have associated the use of natural resources with their conservation, since they have direct dependence on these resources for their economic and social development (Diegues and Viana, 2004Diegues, A.C. and Viana, V.M., 2004. Comunidades tradicionais e manejo dos recursos naturais da Mata Atlântica. São Paulo: Hucitec. 273 p.; Pedroso-Júnior and Sato, 2005Pedroso-Júnior, N.N. and Sato, M., 2005. Ethnoecology and conservation in protected natural areas: incorporating local knowledge in Superagui National Park management. Brazilian Journal of Biology = Revista Brasileira de Biologia, vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 117-127. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1519-69842005000100016. PMid:16025911.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1519-69842005...

, Lima, 2008Lima, I.L.P., 2008. Etnobotânica quantitativa de plantas do Cerrado e extrativismo de mangaba (Hancornia speciosa Gomes) no Norte de Minas Gerais: implicações para o manejo sustentável. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 106 p. Masters Dissertation.; Oliveira, 2009Oliveira, W.L., 2009. Ecologia populacional e extrativismo de frutos de Caryocar brasiliense no Cerrado no norte de Minas Gerais. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 82 p. Masters Dissertation.; Lima et al., 2012Lima, I.L.P., Scariot, A., Medeiros, M.B. and Sevilha, A.C., 2012. Diversidade e uso de plantas do Cerrado em comunidade de Geraizeiros no norte do Estado de Minas Gerais, Brasil. Acta Botanica Brasilica, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 675-684. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-33062012000300017.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-33062012...

, Sousa-Júnior et al., 201Sousa JÚNIOR, J.R., Albuquerque, U.P. and Peroni, N., 2013. Traditional Knowledge and Management of Wittm. (Pequi) in the Brazilian Savanna, Northeastern Brazil. Caryocar coriaceumEconomic Botany, vol. 67, no. 3, pp. 225-233. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12231-013-9241-8.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12231-013-924...

3). An increasing number of studies take into account the value of the vast knowledge of rural communities obtained by practice and observations since this knowledge contributes to the collective definition of the best conservation strategies and sustainable use of resources (Berkes et al., 2000Berkes, F., Colding, J. and Folke, C., 2000. Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecological Applications, vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 1251-1262. http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(2000)010[1251:ROTEKA]2.0.CO;2.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(2000...

; Hanazaki, 2003Hanazaki, N., 2003. Comunidades, conservação e manejo: o papel do conhecimento ecológico local. Biotemas., vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 23-47.; Donovan and Puri, 2004Donovan, D.G. and Puri, R.K., 2004. Learning from traditional knowledge of non-timber forest products: Penan Benalui and the autecology of Aquilaria in Indonesian Borneo. Ecology and Society, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 383-391.; Figueiredo et al., 2006Figueiredo, I.B., Schmidt, I.B. and SAMPAIO, M.B., 2006. Manejo sustentável de capim-dourado e buriti no Jalapão, TO: importância do envolvimento de múltiplos atores. In: R.R. KUBO, J.B. BASSI, C.G. SOUZA, N.L. ALENCAR, P.M. MEDEIROS and U.P. ALBUQUERQUE, eds. Atualidades em Etnobiologia e Etnoecologia. 1st ed. Recife: NUPEEA/Sociedade Brasileira de Etnobiologia e Etnoecologia, vol. 3, pp. 101-114.; Lima, 2008Lima, I.L.P., 2008. Etnobotânica quantitativa de plantas do Cerrado e extrativismo de mangaba (Hancornia speciosa Gomes) no Norte de Minas Gerais: implicações para o manejo sustentável. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 106 p. Masters Dissertation.; Oliveira, 2009Oliveira, W.L., 2009. Ecologia populacional e extrativismo de frutos de Caryocar brasiliense no Cerrado no norte de Minas Gerais. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 82 p. Masters Dissertation.; Schmidt et al., 2007Schmidt, I.B., Figueiredo, I.B. and Scariot, A., 2007. Ethnobotany and effects of harvesting on the population ecology of (Bong.) Ruhland (Eriocaulaceae), from Jalapão region, central Brazil. Syngonanthus nitensEconomic Botany, vol. 61, no. 1, pp. 73-85. http://dx.doi.org/10.1663/0013-0001(2007)61[73:EAEOHO]2.0.CO;2.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1663/0013-0001(2007...

; Sousa-Júnior et al., 2013Sousa JÚNIOR, J.R., Albuquerque, U.P. and Peroni, N., 2013. Traditional Knowledge and Management of Wittm. (Pequi) in the Brazilian Savanna, Northeastern Brazil. Caryocar coriaceumEconomic Botany, vol. 67, no. 3, pp. 225-233. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12231-013-9241-8.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12231-013-924...

; Drumond et al., 2013Drumond, M.A., Guimarães, A.Q., El Bizri, H.R., Giovanetti, L.C., Sepúlveda, D.G. and Martins, R.P., 2013. Life history, distribution and abundance of the giant earthworm . Rhinodrilus alatus RIGHI 1971: conservation and management implicationsBrazilian Journal of Biology = Revista Brasileira de Biologia, vol. 73, no. 4, pp. 699-708. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1519-69842013000400004. PMid:24789384.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1519-69842013...

).

A large number of ethnobotanic studies with brazilian Afrodescendant communities have been reviewed by Albuquerque (1999)ALBUQUERQUE, U.P., 1999. Referências para o estudo da etnobotânica dos descendentes culturais do africano no Brasil. Acta Farma Bonaerense, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 299-306.. Other studies specially developed with “quilombolas” communities were recognized as important sources of information about Brazilian biodiversity, as well for the conservation of biomes such as the Atlantic Rain Forest (Barroso et al., 2010Barroso, R.M., Reis, A. and Hanazaki, N., 2010. Etnoecologia e etnobotânica da palmeira juçara ( Martius) em comunidades quilombolas do Vale do Ribeira, São Paulo. Euterpe edulisActa Botanica Brasílica, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 518-528. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-33062010000200022.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-33062010...

; Crepaldi and Peixoto, 2010CREPALDI, M.O.S. and PEIXOTO, A.L., 2010. Use and knowledge of plants by Quilombolas as subsidies for conservation efforts in an area of Atlantic Forest in Espírito Santo State, Brazil. Biodiversity and Conservation, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 37-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10531-009-9700-9.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10531-009-970...

; Almada, 2012Almada, E.D., 2012. Entre as Serras: etnoecologia de duas comunidades quilombolas no sudeste brasileiro. Campinas: Universidade Estadual de Campinas, 257 p. PhD Thesis.; Adams et al., 2013Adams, C., Chamlian Munari, L., Van Vliet, N., Sereni Murrieta, R.S., Piperata, B.A., Futemma, C., Novaes Pedroso, N., Santos Taqueda, C., Abrahão Crevelaro, M. and Spressola-Prado, V.L., 2013. Diversifying incomes and losing landscape complexity in Quilombola shifting cultivation communities of the atlantic rainforest (Brazil). Human Ecology, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 119-137. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10745-012-9529-9.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10745-012-952...

), the Amazonian (Oliveira et al., 2011Oliveira, D.R., Costa, A.L.M.A., Leitão, G.G., Castro, N.G., Santos, J.P. and Leitão, S.G., 2011. Estudo etnofarmacognóstico da saracuramirá (. Ampelozizyphus amazonicus Ducke), uma planta medicinal usada por comunidades quilombolas do Município de Oriximiná-PA, BrasilActa Amazonica, vol. 41, no. 3, pp. 383-392. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0044-59672011000300008.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0044-59672011...

), and the Cerrado (Franco and Barros, 2006Franco, E.A.P. and BARROS, R.F.M., 2006. Use and diversity of medicinal plants at the “Quilombo Olho D’água dos Pires”, Esperantina, Piaui State, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Plantas Medicinais, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 78-88.; Massarotto, 2009Massarotto, N.P., 2009. Diversidade e uso de plantas medicinais por comunidades quilombolas Kalunga e urbanas no nordeste do estado de Goiás-GO, Brasil. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 140 p. Masters Dissertation.; Cezari, 2010Cezari, E.J., 2010. Plantas medicinais: atividade antitumoral do extrato bruto de sete plantas do cerrado e o uso por povos tradicionais. Tocantins: Universidade Federal do Tocantins, 49 p. Masters Dissertation.; Viana, 2013Viana, R.V.R., 2013. Diálogos possíveis entre saberes científicos e locais associados ao capim-dourado e ao buriti na região do Jalapão, TO. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo, 92 p. Masters Dissertation.). Besides being source of basic subsistence, biodiversity is crucial for the “quilombolas” health care, spiritual practice, and to providing material for infrastructure, technology, ornaments, fuel, and source of alternative income (Franco and Barros, 2006Franco, E.A.P. and BARROS, R.F.M., 2006. Use and diversity of medicinal plants at the “Quilombo Olho D’água dos Pires”, Esperantina, Piaui State, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Plantas Medicinais, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 78-88.; Massarotto, 2009Massarotto, N.P., 2009. Diversidade e uso de plantas medicinais por comunidades quilombolas Kalunga e urbanas no nordeste do estado de Goiás-GO, Brasil. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 140 p. Masters Dissertation.; Barroso et al., 2010Barroso, R.M., Reis, A. and Hanazaki, N., 2010. Etnoecologia e etnobotânica da palmeira juçara ( Martius) em comunidades quilombolas do Vale do Ribeira, São Paulo. Euterpe edulisActa Botanica Brasílica, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 518-528. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-33062010000200022.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-33062010...

; Crepaldi and Peixoto, 2010CREPALDI, M.O.S. and PEIXOTO, A.L., 2010. Use and knowledge of plants by Quilombolas as subsidies for conservation efforts in an area of Atlantic Forest in Espírito Santo State, Brazil. Biodiversity and Conservation, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 37-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10531-009-9700-9.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10531-009-970...

; Cezari, 2010Cezari, E.J., 2010. Plantas medicinais: atividade antitumoral do extrato bruto de sete plantas do cerrado e o uso por povos tradicionais. Tocantins: Universidade Federal do Tocantins, 49 p. Masters Dissertation.; Viana, 2013Viana, R.V.R., 2013. Diálogos possíveis entre saberes científicos e locais associados ao capim-dourado e ao buriti na região do Jalapão, TO. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo, 92 p. Masters Dissertation.).

The “quilombola” community of Pontinha, located in central region of the State of Minas Gerais, is closely related on Cerrado’s biological resources for income and the reproduction of its ways of living (Morais et al., 2013Morais, L.M.O., Pinto, L.C.L., Guimarães, A.Q. and Drumond, M.A., 2013. Conhecimento ecológico tradicional sobre o pequi e outros frutos do Cerrado de interesse comercial no quilombo de Pontinha - Paraopeba/MG. In: Anais do VI Seminário Brasileiro sobre Áreas Protegidas e Inclusão Social (VI SAPIS) e I Encontro Latinoamericano sobre Áreas Protegidas e Inclusão Social (I ELAPIS), 2013, Belo Horizonte. Belo Horizonte: UFMG, vol. 6, no. 1. 1049 p.). Among these resources, the extractivism of a giant earthworm (“minhocuçu”) Rhinodrilus alatus (RIGHI 1971) is one of the most important activities for the “quilombo” dwellers. Nevertheless, the management of this species requires restrictions, especially with respect to its extraction during the breeding period, which occurs in the rainy season from October to February (Drumond et al., 2013Drumond, M.A., Guimarães, A.Q., El Bizri, H.R., Giovanetti, L.C., Sepúlveda, D.G. and Martins, R.P., 2013. Life history, distribution and abundance of the giant earthworm . Rhinodrilus alatus RIGHI 1971: conservation and management implicationsBrazilian Journal of Biology = Revista Brasileira de Biologia, vol. 73, no. 4, pp. 699-708. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1519-69842013000400004. PMid:24789384.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1519-69842013...

). However, suspension of the extraction is more feasible if combined with promoting and developing an alternative source of income during this time of year.

The C. brasiliense species is abundant in Pontinha’s territory and the fruit production overlap with minhocuçu’s breeding period, in this context we seek to study local knowledge about Pequi to contribute to the assessment of the feasibility of its use as an alternative income source for the community.

2 Material and Methods

2.1 Study area

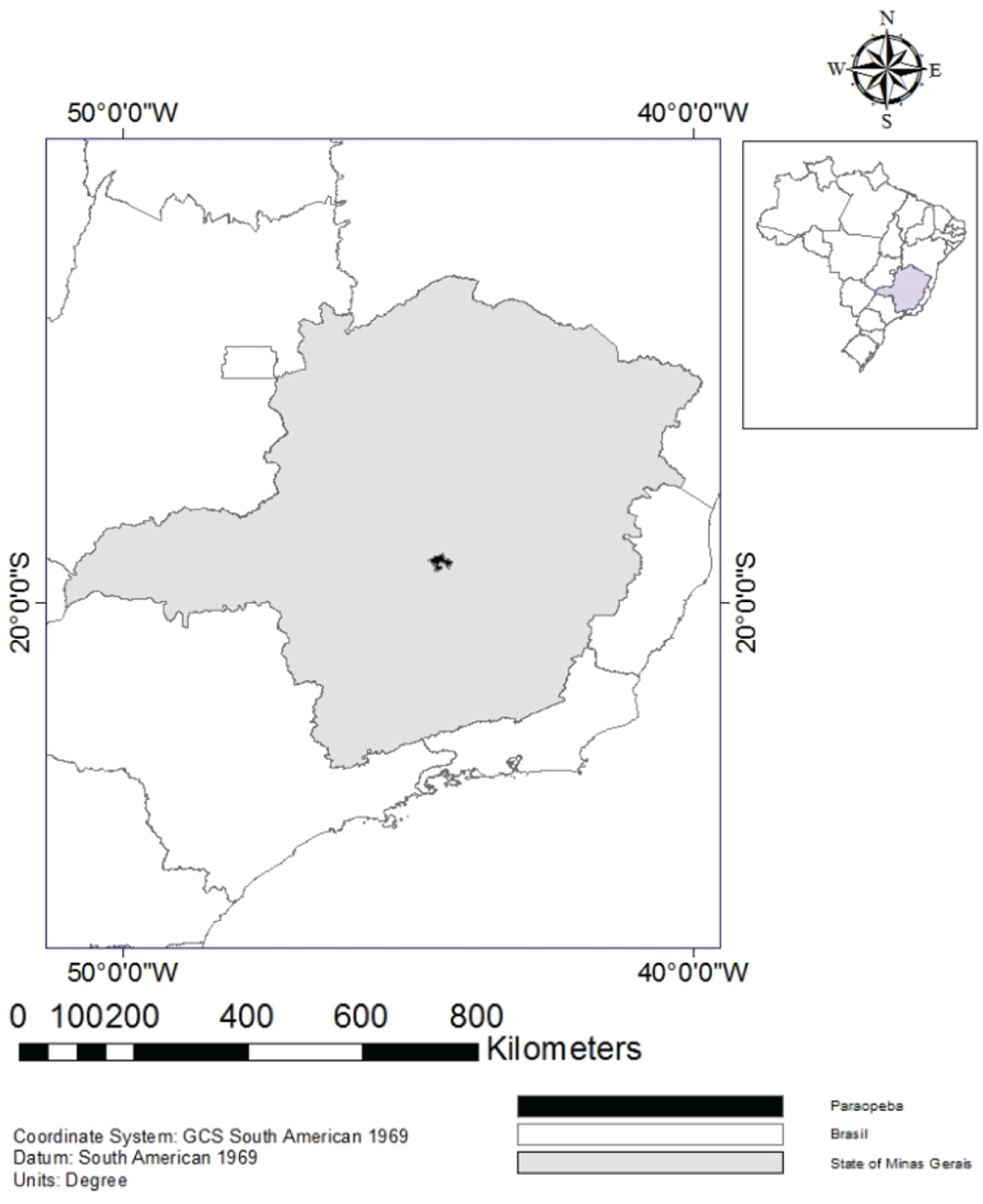

The “quilombo” of Pontinha has 774 hectares and approximately 200 households (Sabará, 2001Sabará, R., 2001. Comunidade Negra Rural de Pontinha: agonia de um modo de produção. Belo Horizonte. mimeo.). This territory is situated in the central region of the State of Minas Gerais, in Brazil, and is 18 km from the municipality of Paraopeba (Figure 1). This area has an important remnant of Cerrado that, although modified, contrasts with the surroundings, where pastures and monocultures of Eucalyptus and Pinus predominate.

Municipality of Paraopeba in the central region of state of Minas Gerais, Brazil, where the “quilombola” community of Pontinha is located.

2.2 Data collection and analyses

Ethnoecological information was gathered through semi-structured interviews of 30 residents and open interviews of 20 residents during the months of November 2012 to July 2014. The use of these tools allowed the research team more flexibility to deepen into topics that emerged spontaneously during the dialogue with the community (Albuquerque et al., 2010Albuquerque, U.P., LUCENA, R.F.P. and ALENCAR, N., 2010. Métodos e técnicas para coleta de dados etnobiológicos. In: U.P. ALBUQUERQUE, R.F.P. LUCENA and N. ALENCAR, eds. Métodos e técnicas na pesquisa etnobotânica e etnoecológica. Recife: NUPEEA, pp. 41-64.). Opened and semi-structured interviews support the establishment of confidence relationships between the researchers and community (Drumond et al., 2009Drumond, M.A., Guimarães, A. and Giovanetti, L., 2009. Técnicas e ferramentas participativas para a Gestão de Unidades de Conservação. Brasília: Ministério do Meio Ambiente, Programa Áreas Protegidas da Amazônia. 120 p.). The choice of first respondent was non-probabilistic and intentional (Bernard, 2006Bernard, H.R., 2006. Research methods in anthropology. 4th ed. Oxford: Altamira Press. 803 p.; Albuquerque et al., 2010Albuquerque, U.P., LUCENA, R.F.P. and ALENCAR, N., 2010. Métodos e técnicas para coleta de dados etnobiológicos. In: U.P. ALBUQUERQUE, R.F.P. LUCENA and N. ALENCAR, eds. Métodos e técnicas na pesquisa etnobotânica e etnoecológica. Recife: NUPEEA, pp. 41-64.) because the researchers had been in contact with the community for over 10 years and established relationships of trust that enabled this selection. After the first contact, the remaining respondents were indicated using the snowball tool (Bailey, 2008Bailey, K., 2008. Methods of social research. 4th ed. New York: The Free Pass. 588 p.).

The interview addressed the seasonal dynamics of Pequi, floral visitors, frugivores and parasites, impacts of fire on the species, and uses of this species. The information on frugivory and floral visitors was obtained from a free list (Bernard, 1988Bernard, H.R., 1988. Research methods in cultural anthropology. Newbury Park: Sage Publications. 520 p.; Albuquerque et al., 2010Albuquerque, U.P., LUCENA, R.F.P. and ALENCAR, N., 2010. Métodos e técnicas para coleta de dados etnobiológicos. In: U.P. ALBUQUERQUE, R.F.P. LUCENA and N. ALENCAR, eds. Métodos e técnicas na pesquisa etnobotânica e etnoecológica. Recife: NUPEEA, pp. 41-64.). Participant observation was also used as residents worked during routine activities involving the Pequi, such as the gathering of fruit in the Cerrado and backyards and uses of the fruit to prepare meals and recipes. In crossing (Drumond et al., 2009Drumond, M.A., Guimarães, A. and Giovanetti, L., 2009. Técnicas e ferramentas participativas para a Gestão de Unidades de Conservação. Brasília: Ministério do Meio Ambiente, Programa Áreas Protegidas da Amazônia. 120 p.) additional information was obtained from reports given by four residents. Triangulation (Drumond et al., 2009Drumond, M.A., Guimarães, A. and Giovanetti, L., 2009. Técnicas e ferramentas participativas para a Gestão de Unidades de Conservação. Brasília: Ministério do Meio Ambiente, Programa Áreas Protegidas da Amazônia. 120 p.) allowed better evaluation of the data obtained.

The resultant information regarding traditional knowledge about the Pequi tree was shared with the local community in a workshop with 11 residents. These results were documented in a video that was discussed with 21 participants in another meeting, where it was possible to legitimize the information obtained.

Smith’s Salience Index (Puri and Vogl, 2005Puri, R.K. and Vogl, C.R., 2005. A methods manual for ethnobiological research and cultural domain analysis: with analysis using ANTHROPAC. Canterbury: Department of Anthropology, University of Kent. 72 p.; Morais and Silva, 2010Morais, F.F. and Silva, C.J., 2010. Conhecimento ecológico tradicional sobre frutiferas para pesca na Comunidade de Estirão Comprido, Barão de Melgaço - Pantanal Matogrossense. Biota Neotropica, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 198-203.) was calculated using Anthropac 4.0 program. A higher Index value (from 0 to 1) indicate a greater consensus among the respondents on the topic studied (Puri and Vogl, 2005Puri, R.K. and Vogl, C.R., 2005. A methods manual for ethnobiological research and cultural domain analysis: with analysis using ANTHROPAC. Canterbury: Department of Anthropology, University of Kent. 72 p.). Semi-structured and open interviews, participation observation, and crossing data were analyzed qualitatively.

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (nº 0388812.2.000.5149). The interviews were always preceded by an explanation about the purpose of work and a permission were given by a Term of Informed Consent (“Termo de Consentimento Livre e Esclarecido”). Recordings, field notes, and photographs were archived at the Laboratory of Socio-Ecological Systems of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais).

3 Results and Discussion

Among the respondents, all were born in the Pontinha community, 19 (63%) were women, 11 (37%) were men, and their ages ranged between 17 and 83 years. The primary uses of Pequi detailed by the respondents were as follows: family food (97%), soap production (67%), oil production (37%), medical treatment (17%), and trade (3%).

In the category “family food”, the following uses of Pequi were included: prepared with rice and chicken, cooked with salt, sweet, shaken with milk and sugar (“Chocolate”), liquor, nut (consumed fresh and the sweet form), with sweet rice, with cheese, cake, and popsicle (“chup chup”).

According to the respondents, the choice of the fruit depends on the purpose of its use, and it is evaluated by the color, flavor, and quantity of the pulp, as well as by the number of seeds and the appearance of the shell. The Pequi trees that are known for the quality of their fruits are identified by reference to the house where the resident lives. The bitter fruits are locally called “marujentos” or rancid and are only used to make soap. By contrast, the sweet fruits with more pulp are called “fleshy” and are used in cooking.

The manufacture of soap from the flesh and kernel of Pequi (inner mesocarp) was mentioned by 63% (n=19) of respondents and also was recorded during the crossing. The soap has a granular appearance and dark color and is only for domestic use, which is in accordance to what was reported and demonstrated by one of the interviewees. Although the use of Pequi for the production of oil was reported in 37% of the interviews (n=11), the majority of respondents were unaware of the methods of extraction and preparation, and only one person indicated that he knew how to extract the oil from the Pequi pulp. Oliveira (2009)Oliveira, W.L., 2009. Ecologia populacional e extrativismo de frutos de Caryocar brasiliense no Cerrado no norte de Minas Gerais. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 82 p. Masters Dissertation. and Lima (2008)Lima, I.L.P., 2008. Etnobotânica quantitativa de plantas do Cerrado e extrativismo de mangaba (Hancornia speciosa Gomes) no Norte de Minas Gerais: implicações para o manejo sustentável. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 106 p. Masters Dissertation. reported the extraction of oil from both Pequi pulp and nuts for use in cooking and traditional medicine in communities in northern Minas Gerais. These products, according to Afonso and Ângelo (2009)Afonso, S.R. and Ângelo, H., 2009. Mercado de produtos florestais não madeiros do cerrado brasileiro. Ciência Florestal, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 315-326. http://dx.doi.org/10.5902/19805098887.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5902/19805098887...

, have a high market value compared with the “in natura” fruit, creams, and sweets. In Ceará State, Caryocar coriaceum fruits are classified by extractivists according to their size (big or small). The big fruits are more valued by buyers, and the small fruits are destined for oil production (Sousa-Júnior et al., 2013Sousa JÚNIOR, J.R., Albuquerque, U.P. and Peroni, N., 2013. Traditional Knowledge and Management of Wittm. (Pequi) in the Brazilian Savanna, Northeastern Brazil. Caryocar coriaceumEconomic Botany, vol. 67, no. 3, pp. 225-233. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12231-013-9241-8.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12231-013-924...

).

Pequi leaves are used for medicinal purposes, and the infusion of young leaves (shoots or “sprouts”) is used to combat flu and abdominal pain and “help the kidneys.” Rural communities in Lavras and Rio Pardo de Minas municipalities, both located in State of Minas Gerais, use Pequi nut and pulp oil to treat respiratory diseases such as bronchitis and asthma (Rodrigues and Carvalho, 2001Rodrigues, V E.G. and CARVALHO, D.A., 2001. Levantamento etnobotânico de plantas medicinais no domínio do cerrado na região do Alto Rio Grande, Minas Gerais. Ciência e Agrotecnologia, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 102-123.; Oliveira, 2009Oliveira, W.L., 2009. Ecologia populacional e extrativismo de frutos de Caryocar brasiliense no Cerrado no norte de Minas Gerais. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 82 p. Masters Dissertation.).

Processed products such as Pequi liqueur, sweets, and soap have been sold locally in the past, and in most cases, sold to order. However, this practice was not observed during the present study. Other uses not mentioned by the participants, including the use of the Pequi shell as an alternative feed for cattle and fish and for manufacturing dark-brown dyes, have been reported in the literature (Bonfá et al., 2009Bonfá, H.C., Rufino, L.M.A., Ribeiro-Junior, C.S., Morais, G., Gerassev, L.C. and Ribeiro, F.L.A., 2009. Efeitos dos níveis de inclusão do farelo da casca de pequi sobre a digestibilidade aparente em caprinos. In: Anais do Congresso Brasileiro de Zootecnia, 2009, Águas de Lindóia. Águas de Lindóia: Associação Brasileira de Zootecnista.; Oliveira and Scariot, 2010Oliveira, W.L. and Scariot, A., 2010. Boas práticas de manejo para o extrativismo sustentável do pequi. Brasília: Embrapa Recursos Genéticos e Biotecnologia. 84 p.), and there may be additional alternative uses in the Pontinha community.

Among the flower visitors, bees had the highest Salience (S=0.639) and were categorized by different local names (Table 1). Hummingbirds were also identified as important floral visitors both at Pontinha (S=0.261) and by Melo (2001)Melo, C., 2001. Diurnal bird visiting of , Camb in central Brazil. Caryocar brasilienseBrazilian Journal of Biology = Revista Brasileira de Biologia, vol. 61, no. 2, pp. 311-316. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-71082001000200014. PMid:11514899.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-71082001...

, in a study conducted in Distrito Federal, in the central Brazilian region. The presence of floral visitors was related to the pursuit of pollen or honey, sweet liquid, sugar, and nectar, and their categorization indicates a similar perception for the type of use, although with distinct terminology.

Values of cultural consensus (S) for the floral visitors of the Pequi tree (Caryocar brasiliense) as cited by respondents from the Pontinha community, Minas Gerais.

The light-colored flowers of the Pequi tree are associated with a strong odor and nectar production at dusk, which suggests that the primary pollinator is bats (Oliveira et al., 2008Oliveira, M.E.B., Guerra, N.B., Barros, L.M. and Alves, R.E., 2008. Aspectos agronômicos e de qualidade do pequi. Fortaleza: Embrapa Agroindústria Tropical. 32 p. Documentos, no. 113.). The importance of bats as pollinators of Pequi trees is recognized in the literature (Melo, 2001Melo, C., 2001. Diurnal bird visiting of , Camb in central Brazil. Caryocar brasilienseBrazilian Journal of Biology = Revista Brasileira de Biologia, vol. 61, no. 2, pp. 311-316. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-71082001000200014. PMid:11514899.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-71082001...

; Oliveira et al., 2008Oliveira, M.E.B., Guerra, N.B., Barros, L.M. and Alves, R.E., 2008. Aspectos agronômicos e de qualidade do pequi. Fortaleza: Embrapa Agroindústria Tropical. 32 p. Documentos, no. 113.; Carvalho, 2008Carvalho, P.E.R., 2008. Espécies arbóreas brasileiras. Brasília: Embrapa Informação Tecnológica. 593 p.) and by the Pontinha respondents, although the Salience Index was low for bats (S=0.017).

Answers related to frugivory were discriminate into two categories: a) animals that feed on fallen fruits and b) animals that feed on unfallen fruits. Frugivores were also grouped according to their respective Salience Indices (Table 2).

Values of cultural consensus (S) for the frugivores of the Pequi tree (Caryocar brasiliense) that eat unfallen fruit and fallen fruit on the ground as cited by respondents from the Pontinha community, Minas Gerais.

The number of animals mentioned that feed on fallen fruits (n=23) was higher than those that feed on unfallen fruits (n=13). According to Oliveira and Scariot (2010)Oliveira, W.L. and Scariot, A., 2010. Boas práticas de manejo para o extrativismo sustentável do pequi. Brasília: Embrapa Recursos Genéticos e Biotecnologia. 84 p., the Pequi fruits complete ripening and have a greater concentration of vitamins and proteins three days after the natural fall, and these characteristics can attract more frugivorous species; in addition, there is greater exposure of the yellow pulp that covers the seed after the fruits fall.

The values of the Salience Indices for animals (Table 2) that feed on unfallen fruits indicate a greater importance of magpies, parrots (“maritaca” and “papagaio,” respectively), bats, and passerine birds. As for the fallen fruit on the ground, ants showed a higher Salience Index (S=0.527). Rheas, seriemas, parrots, crows, carcara hawks, agoutis, deer, opossum, and caterpillars are recognized in the literature as frugivores of C. brasiliense and possible primary dispersers (Gribel, 1986Gribel, R., 1986. Ecologia da polinização e da dispersão de Caryocar brasiliense Camb. (Caryocaraceae) na região do Distrito Federal. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 109 p. Masters Dissertation.; Carvalho, 2008Carvalho, P.E.R., 2008. Espécies arbóreas brasileiras. Brasília: Embrapa Informação Tecnológica. 593 p.; Oliveira and Scariot, 2010Oliveira, W.L. and Scariot, A., 2010. Boas práticas de manejo para o extrativismo sustentável do pequi. Brasília: Embrapa Recursos Genéticos e Biotecnologia. 84 p.). Ants, termites, and beetles can also be effective in removing the pulp and burying the seeds, which may favor germination (Oliveira, 2009Oliveira, W.L., 2009. Ecologia populacional e extrativismo de frutos de Caryocar brasiliense no Cerrado no norte de Minas Gerais. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 82 p. Masters Dissertation.; Zardo and Henriques, 2011Zardo, R.N. and Henriques, R.P.B., 2011. Growth and fruit production of the tree . Caryocar brasiliense in the Cerrado of central BrazilAgroforestry Systems, vol. 82, no. 1, pp. 15-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10457-011-9380-9.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10457-011-938...

).

The most cited flowering period was from August to October, and the most cited fruiting period was from October to January. The Pequi fruits begin to emerge after the flowering period, and the peak season is between December and January for certain regions of Minas Gerais (Leite et al., 2006Leite, G.L.D., Veloso, R.V.D.S., Zanuncio, J.C., Fernandes, L.A. and Almeida, C.I.M., 2006. Phenology of Caryocar brasiliense in Brazilian Cerrado region. Forest Ecology and Management, vol. 236, no. 2-3, pp. 286-294. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2006.09.013.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2006....

). The time of Pequi flowering and fruiting varies according to abiotic factors and is mainly associated with temperature, humidity, and the rainy season (Oliveira and Scariot, 2010Oliveira, W.L. and Scariot, A., 2010. Boas práticas de manejo para o extrativismo sustentável do pequi. Brasília: Embrapa Recursos Genéticos e Biotecnologia. 84 p.). Flowering occurs early in the dry season along with the fall of most of the leaves from June to October (Oliveira, 2009Oliveira, W.L., 2009. Ecologia populacional e extrativismo de frutos de Caryocar brasiliense no Cerrado no norte de Minas Gerais. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 82 p. Masters Dissertation.; Oliveira and Scariot, 2010Oliveira, W.L. and Scariot, A., 2010. Boas práticas de manejo para o extrativismo sustentável do pequi. Brasília: Embrapa Recursos Genéticos e Biotecnologia. 84 p.).

The occurrence of occasional Pequi fruits was mentioned by 93% of respondents (n=28), and it refers to the irregular and unpredictable behavior of several trees that blossom and bear fruit outside of the expected time, generally occurring from June to August. The interviewees indicated that variations in rainfall and temperature are the environmental factors that influence the appearance of occasional fruits. Such occasional harvests also occur in the municipality of Itumirim, southern Minas Gerais, although there is a much lower abundance of fruit in the months of July and August compared with that of the normal harvest season (Oliveira, 2009Oliveira, W.L., 2009. Ecologia populacional e extrativismo de frutos de Caryocar brasiliense no Cerrado no norte de Minas Gerais. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 82 p. Masters Dissertation.).

Biannual fruit yield cycles with major and minor crops were also mentioned by respondents, and the intensity and frequency of rainfall were indicated as the major factors responsible for higher productivity. Alternating productivity of C. brasiliense between years has been reported in the State of Goiás by Santana and Naves (2003)Santana, J.C. and Naves, R.V., 2003. Caracterização de ambientes de cerrado com alta densidade de pequizeiros. Pesquisa Agropecuária Tropical, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 1-10., in Minas Gerais by Oliveira (2009)Oliveira, W.L., 2009. Ecologia populacional e extrativismo de frutos de Caryocar brasiliense no Cerrado no norte de Minas Gerais. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 82 p. Masters Dissertation., and in the Federal District by Zardo and Henriques (2011)Zardo, R.N. and Henriques, R.P.B., 2011. Growth and fruit production of the tree . Caryocar brasiliense in the Cerrado of central BrazilAgroforestry Systems, vol. 82, no. 1, pp. 15-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10457-011-9380-9.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10457-011-938...

, and such productivity is generally associated with flutuations in rainfall. According to Pontinha respondents, the time required for a Pequi tree to begin fruiting is 3 to 20 years, which is the time required to reach a height between 2.5 and 5.0 m. The Pequi tree can require up to 28 years before it begins producing fruits; however, with proper care, this time can be reduced to 8 years (Oliveira, 2009Oliveira, W.L., 2009. Ecologia populacional e extrativismo de frutos de Caryocar brasiliense no Cerrado no norte de Minas Gerais. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 82 p. Masters Dissertation.).

The occurrence of disease or parasites in Pequi trees was mentioned in 37% of the interviews (n=11) and included pests that bore into older trees, caterpillars that eat the leaves or stem and root, leaves that turn purple, and the bird herb and “vigueira” that fatally invade the roots inside the Pequi tree. The caterpillar belonging to the family Cossidae (Lepidoptera) is recognized as a borer into the C. brasiliense trunk (Leite et al., 2011LEITE, G.L.D., ALVES, S.M., NASCIMENTO, A.F., LOPES, P.S.N., FERREIRA, P.S.F.F. and ZANUNCIO, J.C., 2011. Identification of the wood-borer and the factors affecting its attack on . Caryocar brasiliense trees in the Brazilian SavannaActa Scientiarum: Agronomy, vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 589-596. http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/actasciagron.v33i4.8629.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/actasciagron.v...

), and the fungal species Colletotrichum acutatum causes the disease anthracnose on Pequi leaves (Anjos et al., 2002Anjos, J.R.N., Charchar, M.J.A. and Akimoto, A.K., 2002. Ocorrência de antracnose causada por em pequizeiro no Distrito Federal. Colletotrichum acutatumFitopatologia Brasileira, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 96-98. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-41582002000100016.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-41582002...

). One respondent claimed that it was rare for Pequi to become sick because “Pequi is a healthy tree.”

Regarding the Pequi fruit, “caterpillar holes” or “caterpillars that rot the fruit” and “fungi” were the most frequently reported damage; “beetles” and “black spots” in the shell were also mentioned. Caterpillars of the genus Carmenta cause the fruit to drop prematurely, which renders the fruits unsuitable for consumption (Lopes et al., 2003Lopes, P.S.N., Souza, J.C., Reis, P.R., Oliveira, J.M. and Rocha, I.D.F., 2003. Caracterização do ataque da broca dos frutos do pequizeiro. Revista Brasileira de Fruticultura, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 540-543. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-29452003000300046.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-29452003...

). The predation rate of seeds (inner mesocarp) by lepidopteran recorded by Oliveira (2009)Oliveira, W.L., 2009. Ecologia populacional e extrativismo de frutos de Caryocar brasiliense no Cerrado no norte de Minas Gerais. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 82 p. Masters Dissertation. is approximately 5%. The author observed that, during flowering, butterfly larvae cause losses of more than 50% of the crop production. However, Oliveira (2009)Oliveira, W.L., 2009. Ecologia populacional e extrativismo de frutos de Caryocar brasiliense no Cerrado no norte de Minas Gerais. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 82 p. Masters Dissertation. also added that ants live in Pequi trees and work as guardians, protecting the tree against butterflies and other insects.

Most of the respondents perceived a negative influence of fire on the adults or young individuals of C. brasiliense. According to them, young and mature individuals were the most adversely affected by fire, which was also observed by Oliveira (2009)Oliveira, W.L., 2009. Ecologia populacional e extrativismo de frutos de Caryocar brasiliense no Cerrado no norte de Minas Gerais. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 82 p. Masters Dissertation., because fire compromises the trees' growth and reproduction and may lead to death. Although Pequi can resist fire events that are not intense (Medeiros and Miranda, 2005Medeiros, M.B. and Miranda, H.S., 2005. Mortalidade pós-fogo em espécies lenhosas de campo sujo submetido a três queimadas prescritas anuais. Acta Botanica Brasílica, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 493-500. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-33062005000300009.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-33062005...

), the mortality rate, according to Whelan (1995)Whelan, R.J., 1995. The ecology of fire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 346 p., is higher in smaller individuals, which can be attributed to certain traits of younger individuals, such as a thinner bark, as noted in the interviews. Medeiros and Miranda (2005)Medeiros, M.B. and Miranda, H.S., 2005. Mortalidade pós-fogo em espécies lenhosas de campo sujo submetido a três queimadas prescritas anuais. Acta Botanica Brasílica, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 493-500. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-33062005000300009.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-33062005...

point out that the diameter of the individual is the determining factor for the species survival in Cerrado fire events and smaller and shorter plants can survive if the stem diameter is greater.

4 Conclusion

The “quilombola” community of Pontinha has broad ecological knowledge regarding C. brasiliense as well as the importance of this species for local use besides its potential as a source of alternative income. Local knowledge about Pequi supplements the information available in the literature. This fact reinforces the importance of ethnoecological research associated with population ecology and socioeconomics studies. Such complementarity will support the viability analysis of the wider use of Pequi by Pontinha's community, especially when the “minhocuçus” extractive activity is reduced.

Given the process of socio-cultural and economic changes ongoing in the region of this study, understanding the traditional knowledge is fundamentally important for constructing a management proposal for the Pequi and for maintaining the Cerrado’s environmental services.

Furthermore, in future management plans of C. brasiliense, the effects of climate change on the fruit productivity and other direct threats (such as land use changes and burning) to the Cerrado vegetation should be considered, in addition to the impacts of increased extraction.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Pró-Reitorias de Extensão (ProEx) and Pesquisa (PRPq) from Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais and Programa de Pós Graduação em Ecologia, Conservação e Manejo da Vida Silvestre. We are also grateful to the Programa de Extensão Universitária do Ministério da Educação (PROEXT MEC-2013) and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG) for the financial support and Floresta Nacional de Paraopeba for the logistical support. Special appreciation is extended to the Pontinha community for participating in this study.

-

(With 1 figure)

References

- Adams, C., Chamlian Munari, L., Van Vliet, N., Sereni Murrieta, R.S., Piperata, B.A., Futemma, C., Novaes Pedroso, N., Santos Taqueda, C., Abrahão Crevelaro, M. and Spressola-Prado, V.L., 2013. Diversifying incomes and losing landscape complexity in Quilombola shifting cultivation communities of the atlantic rainforest (Brazil). Human Ecology, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 119-137. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10745-012-9529-9

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10745-012-9529-9 - Afonso, S.R. and Ângelo, H., 2009. Mercado de produtos florestais não madeiros do cerrado brasileiro. Ciência Florestal, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 315-326. http://dx.doi.org/10.5902/19805098887

» http://dx.doi.org/10.5902/19805098887 - ALBUQUERQUE, U.P., 1999. Referências para o estudo da etnobotânica dos descendentes culturais do africano no Brasil. Acta Farma Bonaerense, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 299-306.

- Albuquerque, U.P., LUCENA, R.F.P. and ALENCAR, N., 2010. Métodos e técnicas para coleta de dados etnobiológicos. In: U.P. ALBUQUERQUE, R.F.P. LUCENA and N. ALENCAR, eds. Métodos e técnicas na pesquisa etnobotânica e etnoecológica. Recife: NUPEEA, pp. 41-64.

- Almada, E.D., 2012. Entre as Serras: etnoecologia de duas comunidades quilombolas no sudeste brasileiro. Campinas: Universidade Estadual de Campinas, 257 p. PhD Thesis.

- Anjos, J.R.N., Charchar, M.J.A. and Akimoto, A.K., 2002. Ocorrência de antracnose causada por em pequizeiro no Distrito Federal. Colletotrichum acutatumFitopatologia Brasileira, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 96-98. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-41582002000100016

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-41582002000100016 - Aquino, L.P., Borges, S.V., Queiroz, F., Antoniassi, R. and Cirillo, M.A., 2011. Extraction of oil from pequi fruit (Caryocar Brasiliense, Camb.) using several solvents and their mixtures. Grasas y Aceites, vol. 62, no. 3, pp. 245-252. http://dx.doi.org/10.3989/gya.091010

» http://dx.doi.org/10.3989/gya.091010 - AraUjo, F.D., 1995. A review of (Caryocaraceae): an economically valuable species of the central brazilian cerrados. Caryocar brasilienseEconomic Botany, vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 40-48. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02862276

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02862276 - Assunção, P.E.V., 2012. Extrativismo e comercialização de pequi (. Caryocar brasiliense Camb.) em duas cidades no estado de GoiásRevista Economica, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 17-26.

- Bailey, K., 2008. Methods of social research. 4th ed. New York: The Free Pass. 588 p.

- Barbosa, A.S., Ribeiro, M.B. and Schmitz, P.I., 1990. Cultura e ambiente em áreas do sudoeste de Goiás. In: M.N. PINTO, ed. Cerrado caracterização, ocupação e perspectivas. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, pp. 67-100.

- Barroso, R.M., Reis, A. and Hanazaki, N., 2010. Etnoecologia e etnobotânica da palmeira juçara ( Martius) em comunidades quilombolas do Vale do Ribeira, São Paulo. Euterpe edulisActa Botanica Brasílica, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 518-528. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-33062010000200022

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-33062010000200022 - Berkes, F., Colding, J. and Folke, C., 2000. Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecological Applications, vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 1251-1262. http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(2000)010[1251:ROTEKA]2.0.CO;2

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(2000)010[1251:ROTEKA]2.0.CO;2 - Bernard, H.R., 1988. Research methods in cultural anthropology. Newbury Park: Sage Publications. 520 p.

- Bernard, H.R., 2006. Research methods in anthropology. 4th ed. Oxford: Altamira Press. 803 p.

- Bonfá, H.C., Rufino, L.M.A., Ribeiro-Junior, C.S., Morais, G., Gerassev, L.C. and Ribeiro, F.L.A., 2009. Efeitos dos níveis de inclusão do farelo da casca de pequi sobre a digestibilidade aparente em caprinos. In: Anais do Congresso Brasileiro de Zootecnia, 2009, Águas de Lindóia. Águas de Lindóia: Associação Brasileira de Zootecnista.

- BRASIL. Ministério do Meio Ambiente – MMA. Núcleo dos Biomas Cerrado e Pantanal, 2004. Programa Nacional de Conservação e Uso Sustentável do Bioma Cerrado. Brasília. 67 p.

- Carvalho, P.E.R., 2008. Espécies arbóreas brasileiras. Brasília: Embrapa Informação Tecnológica. 593 p.

- Cezari, E.J., 2010. Plantas medicinais: atividade antitumoral do extrato bruto de sete plantas do cerrado e o uso por povos tradicionais. Tocantins: Universidade Federal do Tocantins, 49 p. Masters Dissertation.

- CREPALDI, M.O.S. and PEIXOTO, A.L., 2010. Use and knowledge of plants by Quilombolas as subsidies for conservation efforts in an area of Atlantic Forest in Espírito Santo State, Brazil. Biodiversity and Conservation, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 37-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10531-009-9700-9

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10531-009-9700-9 - Diegues, A.C. and Viana, V.M., 2004. Comunidades tradicionais e manejo dos recursos naturais da Mata Atlântica. São Paulo: Hucitec. 273 p.

- Donovan, D.G. and Puri, R.K., 2004. Learning from traditional knowledge of non-timber forest products: Penan Benalui and the autecology of Aquilaria in Indonesian Borneo. Ecology and Society, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 383-391.

- Drumond, M.A., Guimarães, A. and Giovanetti, L., 2009. Técnicas e ferramentas participativas para a Gestão de Unidades de Conservação. Brasília: Ministério do Meio Ambiente, Programa Áreas Protegidas da Amazônia. 120 p.

- Drumond, M.A., Guimarães, A.Q., El Bizri, H.R., Giovanetti, L.C., Sepúlveda, D.G. and Martins, R.P., 2013. Life history, distribution and abundance of the giant earthworm . Rhinodrilus alatus RIGHI 1971: conservation and management implicationsBrazilian Journal of Biology = Revista Brasileira de Biologia, vol. 73, no. 4, pp. 699-708. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1519-69842013000400004 PMid:24789384.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1519-69842013000400004 - Figueiredo, I.B., Schmidt, I.B. and SAMPAIO, M.B., 2006. Manejo sustentável de capim-dourado e buriti no Jalapão, TO: importância do envolvimento de múltiplos atores. In: R.R. KUBO, J.B. BASSI, C.G. SOUZA, N.L. ALENCAR, P.M. MEDEIROS and U.P. ALBUQUERQUE, eds. Atualidades em Etnobiologia e Etnoecologia. 1st ed. Recife: NUPEEA/Sociedade Brasileira de Etnobiologia e Etnoecologia, vol. 3, pp. 101-114.

- Franco, E.A.P. and BARROS, R.F.M., 2006. Use and diversity of medicinal plants at the “Quilombo Olho D’água dos Pires”, Esperantina, Piaui State, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Plantas Medicinais, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 78-88.

- Galuppo, S.C., 2004. Documentação do uso e da valorização do óleo do Piquiá (Caryocar villosum) e do leite do Amapá-doce (Brosimum parinarioides) para a Comunidade de Piquiatuba, Floresta Nacional do Tapajós: estudos físicos, químicos, fitoquímicos e famacológicos. Belém: Universidade Federal Rural da Amazônia, 108 p. Masters Dissertation.

- Germano, J.N., SILVA, R.L.A. and SANTOS, E.M., 2007. Estudo etnobotânico das plantas medicinais do cerrado do estado de Mato Grosso. Revista Brasileira de Plantas Medicinais, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 23-31.

- Gonçalves, C.U., 2008. Os pequizeiros da Chapada do Araripe. Revista de Geografia., vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 88-103.

- Gribel, R., 1986. Ecologia da polinização e da dispersão de Caryocar brasiliense Camb. (Caryocaraceae) na região do Distrito Federal. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 109 p. Masters Dissertation.

- Hanazaki, N., 2003. Comunidades, conservação e manejo: o papel do conhecimento ecológico local. Biotemas., vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 23-47.

- LEITE, G.L.D., ALVES, S.M., NASCIMENTO, A.F., LOPES, P.S.N., FERREIRA, P.S.F.F. and ZANUNCIO, J.C., 2011. Identification of the wood-borer and the factors affecting its attack on . Caryocar brasiliense trees in the Brazilian SavannaActa Scientiarum: Agronomy, vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 589-596. http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/actasciagron.v33i4.8629

» http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/actasciagron.v33i4.8629 - Leite, G.L.D., Veloso, R.V.D.S., Zanuncio, J.C., Fernandes, L.A. and Almeida, C.I.M., 2006. Phenology of Caryocar brasiliense in Brazilian Cerrado region. Forest Ecology and Management, vol. 236, no. 2-3, pp. 286-294. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2006.09.013

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2006.09.013 - Lima, I.L.P., 2008. Etnobotânica quantitativa de plantas do Cerrado e extrativismo de mangaba (Hancornia speciosa Gomes) no Norte de Minas Gerais: implicações para o manejo sustentável. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 106 p. Masters Dissertation.

- Lima, I.L.P., Scariot, A., Medeiros, M.B. and Sevilha, A.C., 2012. Diversidade e uso de plantas do Cerrado em comunidade de Geraizeiros no norte do Estado de Minas Gerais, Brasil. Acta Botanica Brasilica, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 675-684. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-33062012000300017

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-33062012000300017 - Lopes, P.S.N., Souza, J.C., Reis, P.R., Oliveira, J.M. and Rocha, I.D.F., 2003. Caracterização do ataque da broca dos frutos do pequizeiro. Revista Brasileira de Fruticultura, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 540-543. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-29452003000300046

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0100-29452003000300046 - Massarotto, N.P., 2009. Diversidade e uso de plantas medicinais por comunidades quilombolas Kalunga e urbanas no nordeste do estado de Goiás-GO, Brasil. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 140 p. Masters Dissertation.

- Medeiros, H. and Amorim, A.M.A., 2015 [viewed 20 January 2015]. . In: CaryocaraceaeJARDIM BOTÂNICO DO RIO DE JANEIRO – JBRJ. Lista de espécies da flora do Brasil [online]. Rio de Janeiro: JBRJ. Available from: http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/jabot/floradobrasil/FB6688

» http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/jabot/floradobrasil/FB6688 - Medeiros, M.B. and Miranda, H.S., 2005. Mortalidade pós-fogo em espécies lenhosas de campo sujo submetido a três queimadas prescritas anuais. Acta Botanica Brasílica, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 493-500. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-33062005000300009

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0102-33062005000300009 - Melo, C., 2001. Diurnal bird visiting of , Camb in central Brazil. Caryocar brasilienseBrazilian Journal of Biology = Revista Brasileira de Biologia, vol. 61, no. 2, pp. 311-316. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-71082001000200014 PMid:11514899.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-71082001000200014 - Mittermeier, R.A., Gil, P.R., Hoffman, M., Pilgrim, J., Brooks, T., Mittermeier, C.G., Lamoreux, J. and Fonseca, G.A.B., 2004. Hotspots revisited. Mexico: Cemex. 392 p.

- Monteles, R. and Pinheiro, C.U.B., 2007. Plantas medicinais em um quilombo maranhense: uma perspectiva etnobotânica. Revista de Biologia e Ciências da Terra, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 1-11.

- Morais, F.F. and Silva, C.J., 2010. Conhecimento ecológico tradicional sobre frutiferas para pesca na Comunidade de Estirão Comprido, Barão de Melgaço - Pantanal Matogrossense. Biota Neotropica, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 198-203.

- Morais, L.M.O., Pinto, L.C.L., Guimarães, A.Q. and Drumond, M.A., 2013. Conhecimento ecológico tradicional sobre o pequi e outros frutos do Cerrado de interesse comercial no quilombo de Pontinha - Paraopeba/MG. In: Anais do VI Seminário Brasileiro sobre Áreas Protegidas e Inclusão Social (VI SAPIS) e I Encontro Latinoamericano sobre Áreas Protegidas e Inclusão Social (I ELAPIS), 2013, Belo Horizonte. Belo Horizonte: UFMG, vol. 6, no. 1. 1049 p.

- Oliveira, D.R., Costa, A.L.M.A., Leitão, G.G., Castro, N.G., Santos, J.P. and Leitão, S.G., 2011. Estudo etnofarmacognóstico da saracuramirá (. Ampelozizyphus amazonicus Ducke), uma planta medicinal usada por comunidades quilombolas do Município de Oriximiná-PA, BrasilActa Amazonica, vol. 41, no. 3, pp. 383-392. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0044-59672011000300008

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0044-59672011000300008 - Oliveira, M.E.B., Guerra, N.B., Barros, L.M. and Alves, R.E., 2008. Aspectos agronômicos e de qualidade do pequi. Fortaleza: Embrapa Agroindústria Tropical. 32 p. Documentos, no. 113.

- Oliveira, W.L. and Scariot, A., 2010. Boas práticas de manejo para o extrativismo sustentável do pequi. Brasília: Embrapa Recursos Genéticos e Biotecnologia. 84 p.

- Oliveira, W.L., 2009. Ecologia populacional e extrativismo de frutos de Caryocar brasiliense no Cerrado no norte de Minas Gerais. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 82 p. Masters Dissertation.

- Pedroso-Júnior, N.N. and Sato, M., 2005. Ethnoecology and conservation in protected natural areas: incorporating local knowledge in Superagui National Park management. Brazilian Journal of Biology = Revista Brasileira de Biologia, vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 117-127. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1519-69842005000100016 PMid:16025911.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1519-69842005000100016 - Pianovski, A.R., Vilela, A.F.G., Silva, A.A.S., Lima, C.G., Silva, K.K., Carvalho, V.F.M., Musis, C.R., MACHADO, S.R.P. and FERRARI, M., 2008. Uso do óleo de pequi ( ) em emulsões cosméticas: desenvolvimento e avaliação da estabilidade física. CaryocarbrasilienseRevista Brasileira de Ciências Farmacêuticas, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 249-259.

- POZO, O.V.C., 1997. O pequi (Caryocar brasiliense): uma alternativa para o desenvolvimento sustentável do cerrado no Norte de Minas Gerais. Lavras: Universidade Federal de Lavras, 100 p. Masters Dissertation.

- Puri, R.K. and Vogl, C.R., 2005. A methods manual for ethnobiological research and cultural domain analysis: with analysis using ANTHROPAC. Canterbury: Department of Anthropology, University of Kent. 72 p.

- RATTER, J., 1997. The Brazilian Cerrado vegetation and threats to its biodiversity. Annals of Botany, vol. 80, no. 3, pp. 223-230. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/anbo.1997.0469

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/anbo.1997.0469 - Rios, M., Martins-Da-Silva, R.C.V., Sabogal, C., Martins, J., Silva, R.N., Brito, R.R., Brito, I.M., Brito, M.F.C., Silva, J.R. and Ribeiro, R.T., 2001. Benefícios das plantas da capoeira para a comunidade de Benjamin Constant, Pará, Amazônia Brasileira. Belém: CIFOR. 54 p.

- Rodrigues, V E.G. and CARVALHO, D.A., 2001. Levantamento etnobotânico de plantas medicinais no domínio do cerrado na região do Alto Rio Grande, Minas Gerais. Ciência e Agrotecnologia, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 102-123.

- Roesler, R., Catharino, R.R., Malta, L.G., Eberlin, M.N. and Pastore, G., 2008. Antioxidant activity of Caryocar brasiliense (pequi) and characterization of components by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Food Chemistry, vol. 110, no. 3, pp. 711-717. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.02.048

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.02.048 - Sabará, R., 2001. Comunidade Negra Rural de Pontinha: agonia de um modo de produção. Belo Horizonte. mimeo.

- Sano, S.M., Almeida, S.P. and Ribeiro, J.F., 2008. Cerrado: ecologia e flora. Brasília: EMBRAPA. 1279 p. Informação Tecnológica, vol. 1.

- Santana, J.C. and Naves, R.V., 2003. Caracterização de ambientes de cerrado com alta densidade de pequizeiros. Pesquisa Agropecuária Tropical, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 1-10.

- Santos, F.S., Santos, R.F., Dias, P.P., Zanão-Junior, L.A. and Tomassoni, F., 2013. A cultura do Pequi (Caryocar brasiliense Camb.). Acta Iguazu, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 46-57.

- Saraiva, R.A., Araruna, M.K.A., Oliveira, R.C., Menezes, K.D.P., Leite, G.O., Kerntopf, M.R., Costa, J.G.M., Rocha, J.B.T., Tomé, A.R., Campos, A.R. and Menezes, I.R.A., 2011. Topical anti-inflammatory effect of Wittm.(Caryocaraceae) fruit pulp fixed oil on mice ear edema induced by different irritant agents. Caryocar coriaceumJournal of Ethnopharmacology, vol. 136, no. 3, pp. 504-510. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2010.07.002 PMid:20621180.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2010.07.002 - Schmidt, I.B., Figueiredo, I.B. and Scariot, A., 2007. Ethnobotany and effects of harvesting on the population ecology of (Bong.) Ruhland (Eriocaulaceae), from Jalapão region, central Brazil. Syngonanthus nitensEconomic Botany, vol. 61, no. 1, pp. 73-85. http://dx.doi.org/10.1663/0013-0001(2007)61[73:EAEOHO]2.0.CO;2

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1663/0013-0001(2007)61[73:EAEOHO]2.0.CO;2 - Silva, M.N.S. and TUBALDINI, M.A.S., 2013. O ouro do cerrado: a dinâmica do extrativismo do pequi no norte de Minas Gerais. Revista Geoaraguaia, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 293-317.

- Sousa JÚNIOR, J.R., Albuquerque, U.P. and Peroni, N., 2013. Traditional Knowledge and Management of Wittm. (Pequi) in the Brazilian Savanna, Northeastern Brazil. Caryocar coriaceumEconomic Botany, vol. 67, no. 3, pp. 225-233. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12231-013-9241-8

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12231-013-9241-8 - Viana, R.V.R., 2013. Diálogos possíveis entre saberes científicos e locais associados ao capim-dourado e ao buriti na região do Jalapão, TO. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo, 92 p. Masters Dissertation.

- Vieira, R.F., Costa, T.S.A., Silva, D.B., Ferreira, F.R. and Sano, S.M., 2006. Frutas nativas da região centro‐oeste. Brasília: Embrapa Recursos Genéticos e Biotecnologia. 320 p.

- Whelan, R.J., 1995. The ecology of fire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 346 p.

- Zardo, R.N. and Henriques, R.P.B., 2011. Growth and fruit production of the tree . Caryocar brasiliense in the Cerrado of central BrazilAgroforestry Systems, vol. 82, no. 1, pp. 15-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10457-011-9380-9

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10457-011-9380-9

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

05 Apr 2016 -

Date of issue

Apr-Jun 2016

History

-

Received

04 Nov 2014 -

Accepted

09 Feb 2015