Abstract

Basic information on natural history is crucial for assessing the viability of populations, but is often lacking for many species of conservation concern. One such species is the White-tailed Tropicbird, Phaethon lepturus (Mathews, 1915). Here, we address this shortfall by providing detailed information on reproductive biology, distribution and threats on the Fernando de Noronha archipelago, Brazil – the largest colony of P. lepturus in the South Atlantic. We assessed reproduction from August 2011 to January 2012 by monitoring tropicbird nests and their contents. A population estimate was obtained through a combination of active searches for nests and by census at sea between 2010 and 2012. Breeding success was calculated by traditional methods. The growth curve of chicks and life table were also calculated. Additional information on nest and mate fidelity and on age of breeding birds was obtained from the banded birds. Our results indicate that the unusual nest form (limestone pinnacles) and predation by crabs may be responsible for the observed patterns of hatching and fledging success. Although the Fernando de Noronha population appears to be stable (at between 100-300 birds), a long term monitoring program would be desirable to assess fluctuations in this globally important population. Conservation strategies should focus on controlling predation by land crabs and tegu lizards.

Keywords:

Phaethon lepturus; seabird; breeding biology; Fernando de Noronha; Brazil

Resumo

Informações básicas sobre história natural são cruciais para acessar a viabilidade de populações, mas são ausentes para muitas espécies que necessitam de conservação. Uma destas espécies é o rabo-de-palha-de-bico-laranja, Phaethon lepturus Daudin, 1802. Aqui, vamos abordar o déficit de dados para esta espécie, fornecendo informações detalhadas sobre a biologia reprodutiva, tamanho da população, distribuição e ameaças em Fernando de Noronha, Brasil – a maior colônia de P. lepturus no Atlântico Sul. Acompanhamos a reprodução do rabo-de-palha-de-bico-laranja de Agosto de 2010 a Janeiro de 2011 monitorando ninhos e seus conteúdos. A estimativa da população foi obtida através de uma combinação de busca ativa de ninhos e censo no mar entre 2010 e 2012. O sucesso reprodutivo foi avaliado por métodos tradicionais. A curva de crescimento da coorte e a tabela de vida também foram obtidas. Além disso, informações sobre fidelidade ao ninho e parceiro e, a idade de reprodutores foi obtida a partir das aves anilhadas anteriormente. Nossos resultados indicam que a forma incomum de ninho (pináculos de calcário) e a predação por caranguejos podem ser responsáveis pelo sucesso observado de eclosão e recrutamento. A população de Fernando de Noronha parece estar estável entre 100-300 aves. No entanto, um programa de monitoramento a longo prazo seria desejável para avaliar as flutuações desta população globalmente importante. As estratégias de conservação devem se concentrar em controlar a predação por caranguejos e lagartos teiú.

Palavras-chave:

Phaethon lepturus; ave marinha; biologia reprodutiva; Fernando de Noronha; Brasil

1 Introduction

Tropicbirds (order Phaethontiformes) are mid-sized seabirds distributed in tropical and subtropical regions (Orta, 1992Orta, J., 1992, Family Phaethontidae. In: J. DEL HOYO, A. ELLIOTT and J. SARGATAL, eds. Handbook of the birds of the world. Vol. I. Ostrich to Ducks. Barcelona: Lynx Editions, pp. 280-289.). They have a complex life-cycle, using pelagic areas for feeding and oceanic islands for breeding (Orta, 1992Orta, J., 1992, Family Phaethontidae. In: J. DEL HOYO, A. ELLIOTT and J. SARGATAL, eds. Handbook of the birds of the world. Vol. I. Ostrich to Ducks. Barcelona: Lynx Editions, pp. 280-289.). Tropicbirds are represented by a single genus, Phaethon Linnaeus, 1758, currently composed of three species: red-billed tropicbird, Phaethon aethereus Linnaeus, 1758, red-tailed tropicbird, P. rubricauda Boddaert, 1783 and white-tailed tropicbird, P. lepturus Daudin, 1802 (Orta, 1992Orta, J., 1992, Family Phaethontidae. In: J. DEL HOYO, A. ELLIOTT and J. SARGATAL, eds. Handbook of the birds of the world. Vol. I. Ostrich to Ducks. Barcelona: Lynx Editions, pp. 280-289.). In South Atlantic, there are records of all three species, but only the red-billed tropicbird and the white-tailed tropicbird have been observed to breed on Brazilian islands (Couto et al., 2001Couto, G.S., INTERAMINENSE, L.J.L. and MORETTE, M.E., 2001. Primeiro registro de Boddaert, 1783 para o Brasil. Phaethon rubricaudaNattereria, vol. 2, pp. 24-25.; Piacentini et al., 2015PIACENTINI, V.D.Q., ALEIXO, A., AGNE, C.E., MAURÍCIO, G.N., PACHECO, J.F., BRAVO, G.A., BRITO, G.R.R., NAKA, L.N., OLMOS, F., POSSO, S., SILVEIRA, L.F., BETINI, G.S., CARRANO, E., FRANZ, I., LEES, A.C., LIMA, L.M., PIOLI, D., SCHUNCK, F., AMARAL, F.R., BENCKE, G.A., COHN-HAFT, M., FIGUEIREDO, L.F., STRAUBE, F.C. and CESARI, E., 2015. Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee/Lista comentada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos. Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia, vol. 23, pp. 90-298.). White-tailed Tropicbirds (hereafter WTTBs) breed on two Brazilian archipelagos, Fernando de Noronha and Abrolhos (Figure 1). The former is the largest colony of WTTBs in the South Atlantic outside of the Caribbean sea with the species less abundant on the Abrolhos archipelago (Schulz-Neto, 2004Schulz-Neto, A., 2004. Aves insulares do arquipélago de Fernando de Noronha. In: J.O. BRANCO, org. Aves marinhas e insulares brasileiras: bioecologia e conservação. Itajai: Univali, pp. 147-168.).

Among birds, colonial seabirds are particularly prone to predation due to their high breeding densities within small areas (Butchart et al., 2004Butchart, S.H., Stattersfield, A.J., Bennun, L.A., Shutes, S.M., Akçakaya, H.R., Baillie, J.E., STUART, S.N., HILTON-TAYLOR, C. and Mace, G.M., 2004. Measuring global trends in the status of biodiversity: Red List Indices for birds. PLoS Biology, vol. 2, no. 12, pp. e383. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0020383. PMid:15510230.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0...

) combined with their limited mobility on the ground (Ricklefs, 1996Ricklefs, R.E., 1996. A economia da natureza. 3rd ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan.; Joneset al.,2008Jones, H.P., TERSHY, B.R., ZAVALETA, E.S., CROLL, D.A., KEITT, B.S., FINKELSTEIN, M.E. and HOWALD, G.R., 2008. Severity of the effects of invasive rats on seabirds: a global review. Conservation Biology, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 16-26.). These vulnerabilities make pelagic seabirds one of the most threatened groups of birds (Croxall et al., 2012Croxall, J.P., BUTCHART, S.H.M., LASCELLES, B., STATTERSFIELD, A.J., SULLIVAN, B., SYMES, A. and TAYLOR, P., 2012. Seabird conservation status, threats and priority actions: a global assessment. Bird Conservation International, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 1-34.), and the reproductive period is the most vulnerable period of their life cycle. As in other seabirds, the breeding cycle, breeding site selection and nest location of WTTBs are influenced by climate, food availability, density and other biotic an abiotic factors (Phillips, 1987Phillips, N.J., 1987. The breeding of White-tailed Tropicbirds at Cousin Island, Seychelles. Phaethon lepturusThe Ibis, vol. 129, no. 1, pp. 10-24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-919X.1987.tb03156.x.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-919X.19...

; Ramos et al., 2005Ramos, J.A., Bowler, J., Betts, M., Pacheco, C., Agombar, J., Bullock, I. and Monticelli, D., 2005. Productivity of white-tailed tropicbird on Aride Island, Seychelles. Waterbirds, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 405-410. http://dx.doi.org/10.1675/1524-4695(2005)28[405:POWTOA]2.0.CO;2.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1675/1524-4695(2005...

; Catry et al., 2009Catry, T., Ramos, J.A., Monticelli, D., Bowler, J., Jupiter, T. and Le Corre, M., 2009. Demography and conservation of the white-tailed tropicbird . Phaethon lepturus on Aride Island, western Indian OceanJournal für Ornithologie, vol. 150, no. 3, pp. 661-669. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10336-009-0389-z.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10336-009-038...

). Breeding success in colonial seabirds is particularly sensitive to fluctuations in food availability (Weimerskirch, 2001Weimerskirch, H., 2001. Seabird demography and its relationship with the marine environment. In: E.A. SCHREIBER and J. BURGER, eds. Biology of marine birds. Boca Raton: CRC Press, pp. 113-132.) and predation intensity (Whittam and Leonard, 2000Whittam, R.M. and Leonard, M.L., 2000. Characteristics of predators and offspring influence nest defense by Arctic and Common Terns. Condor, vol. 102, no. 2, pp. 301-306.; Nordström et al., 2004Nordström, M., Laine, J., Ahola, M. and Korpimäki, E., 2004. Reduced nest defence intensity and improved breeding success in terns as responses to removal of non-native American mink. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, vol. 55, no. 5, pp. 454-460.). In the case of Tropicbirds, predation by exotic species (mainly rats – Gaston and Jones, 1998Gaston, A.J. and Jones, I.L., 1998. The auks. New York: Oxford University Press.; Sarmento et al., 2014Sarmento, R., Brito, D., Ladle, R.J., Leal, G.R. and Efe, M.A., 2014. Invasive house (Rattus rattus) and brown rats (Rattus norvegicus) threaten the viability of red-billed tropicbird (Phaethon aethereus) in Abrolhos National Park, Brazil. Tropical Conservation Science, vol. 7, pp. 614-627.) and native species (mainly large crabs - Phillips, 1987Phillips, N.J., 1987. The breeding of White-tailed Tropicbirds at Cousin Island, Seychelles. Phaethon lepturusThe Ibis, vol. 129, no. 1, pp. 10-24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-919X.1987.tb03156.x.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-919X.19...

; Schaffner, 1991Schaffner, F.C., 1991. Nest-site selection and nesting success of white-tailed tropicbirds (Phaethon lepturus) at Cayo Luis Pena, Puerto Rico. The Auk, vol. 108, pp. 911-922.) is the main cause of mortality during breeding.

Althoughthe WTTB is not considered as globally threatened species (BirdLife International, 2012BIRDLIFE INTERNATIONAL, 2012 [viewed 16 September 2013]. Phaethon lepturus. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species [online]. Available from: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/22696645/0

http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/22696...

), in some localitiespopulations are declining (Bermuda, Cuba, the Cayman Islands, Puerto Rico, and Jamaica) and face a range of threats (Orta, 1992Orta, J., 1992, Family Phaethontidae. In: J. DEL HOYO, A. ELLIOTT and J. SARGATAL, eds. Handbook of the birds of the world. Vol. I. Ostrich to Ducks. Barcelona: Lynx Editions, pp. 280-289.; Lee and Walsh-McGehee, 2000Lee, D.S. and Walsh-Mcgehee, M., 2000. Population estimates, conservation concerns, and management of tropicbirds in the Western Atlantic. Caribbean Journal of Science, vol. 36, pp. 267-279.). In Brazil, the WTTB is listed as a nationally threatenedspecies due to its small population size (Efe, 2008Efe, M.A., 2008. . In: Phaethon lepturusA.B.M. MACHADO, G.M. DRUMMOND and A.P. PAGLIA, eds. Livro vermelho da fauna brasileira ameaçada de extinção. Brasília: Fundação Biodiversitas. pp. 414-417.; BRASIL, 2003BRASIL. Ministério do Meio Ambiente – MMA, 2003 [viewed 14 September 2013]. Instrução normativa MMA nº 3, de 27 de maio de 2003. Divulga a relação de Espécies da Fauna Brasileira Ameaçadas de Extinção. Diário Oficial [online], Brasília, 28 maio. Available from: http://www.mma.gov.br/estruturas/179/_arquivos/179_05122008034002.pdf

http://www.mma.gov.br/estruturas/179/_ar...

). Like other seabird species, effective conservation of the small, isolated Brazilian sub-populations is handicapped by a lack of basic information on their natural history (Bartholomew, 1986Bartholomew, G.A., 1986. The role of History in Contemporary Biology. BioScience, vol. 36-35, pp. 324-329.) and reproductive success (Dearborn et al., 2001Dearborn, D.C., Anders, A.D. and Flint, E.N., 2001. Trends in reproductive success of Hawaiian seabirds: is guild membership a good criterion for choosing indicator species? Biological Conservation, vol. 101, no. 1, pp. 97-103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(01)00030-1.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(01)...

). Such information is crucial for accurately assessing the viability of these isolated populations (Weimerskirch, 2001Weimerskirch, H., 2001. Seabird demography and its relationship with the marine environment. In: E.A. SCHREIBER and J. BURGER, eds. Biology of marine birds. Boca Raton: CRC Press, pp. 113-132.). Knowledge about the breeding biology of Brazilian WTTBs is especially scarce (Oren, 1982Oren, D.C., 1982. A avifauna do Arquipélago de Fernando de Noronha. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emilio Goeldi - Nova Série. Zoologia, vol. 118, pp. 1-22.; Schulz-Neto, 1995Schulz-Neto, A., 1995. Observação de aves no Parque Nacional Marinho de Fernando de Noronha: guia de campo. Brasília: Ministério do Meio Ambiente, dos Recursos Hídricos e da Amazônia legal.; Alves et al., 1997Alves, V.S., Soares, A.B.A., Couto, G.S., RIBEIRO, A.B.B. and EFE, M.A., 1997. Aves do Arquipélago dos Abrolhos, Bahia, Brasil. Ararajuba, vol. 5-2, pp. 209-218.; Alves et al., 2004Alves, V.S., Soares, A.B.A. and Couto, G.S., RIBEIRO, A.B.B. and EFE, M.A., 2004. Aves marinhas de Abrolhos. In: J.O. BRANCO, org. Aves marinhas e insulares brasileiras: bioecologia e conservação. Itajai: Univali, pp. 213-232.; Schulz-Neto, 2004Schulz-Neto, A., 2004. Aves insulares do arquipélago de Fernando de Noronha. In: J.O. BRANCO, org. Aves marinhas e insulares brasileiras: bioecologia e conservação. Itajai: Univali, pp. 147-168.). Here, we address this shortfall by providing detailed information on the reproductive biology, distribution and threats faced by WTTBs on Fernando de Noronha, the largest breeding colony in Brazil.

2 Methods

2.1 Study area

Fernando de Noronha is a volcanic archipelago located 400 km off the Brazilian coast (Figure 1; 3° 54'S and 32° 25' W). It is composed of 21 islands and islets and occupies a total area of 26 km2 (IBAMA, 1990INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DO MEIO AMBIENTE E DOS RECURSOS NATURAIS RENOVÁVEIS – IBAMA, 1990. Plano de Manejo do Parque Nacional Marinho de Fernando de Noronha. Brasília: FUNATURA.). The average annual temperature is 27ºC and annual rainfall is around 1400 mm. The mean water surface temperature ranges from 28ºC and 30º C and the surface salinity ranges between 35.0 and 37.0%0 (Macedo et al., 1988Macedo, S.J., Montes, M.J.F., Lins, I.C. and Costa, K.M.P., 1988. Revizee. Programa de Avaliação do Potencial Sustentável dos Recursos Vivos da Zona Econômica Exclusiva, SCORE/NE. Recife: UFPE. 37 p. Relatório da Oceanografia Química.). The climate is tropical and has two distinct seasons: a rainy season, from January to August and a dry season for the remainder of the year. The archipelago is influenced by the intense and constant alisios winds, blowing from east to southeast (Batistella, 1996Batistella, M., 1996. Espécies vegetais dominantes do Arquipélago de Fernando de Noronha: grupos ecológicos e repartição espacial. Acta Botanica Brasílica, vol. 10, pp. 223-235.). The archipelago contains cats, rats and the large lizard (Tupinambis merianae) that are known to predate seabirds (Efe, 2008Efe, M.A., 2008. . In: Phaethon lepturusA.B.M. MACHADO, G.M. DRUMMOND and A.P. PAGLIA, eds. Livro vermelho da fauna brasileira ameaçada de extinção. Brasília: Fundação Biodiversitas. pp. 414-417.).

2.2 Fieldwork

Reproduction of WTTBs in the Fernando de Noronha archipelago was monitored between August 2011and January 2012. Monitoring took place on Chapéu Island, located on the south side of the main island because it had a high concentration of nests. All actives nests were located, labeled, geo-referenced and visited weekly. Nests were monitored carefully to avoid abandonment by adults. Adults, chicks with birth dates recorded and eggs were measured (X̅ ± SD) with calipers (± 0.01mm) and their weight was measured using a Pesola scale (± 5g). Blood samples of adults was collected and stored on an FTA card for the molecular determination of sex. DNA was extracted according to Boyce et al. (1989)Boyce, T.M., Zwick, M.E. and Aquadro, C.F., 1989. Mitochondrial DNA in the Bark Weevils: size, structure and heteroplasmy. Genetics, vol. 123, no. 4, pp. 825-836. PMid:2612897. protocol. Molecular sexing was performed using P2-P8 primers designed originally by Griffiths et al. (1998)Griffiths, R., Double, M.C., Orr, K. and Dawson, R.J., 1998. A DNA test to sex most birds. Molecular Ecology, vol. 7, no. 8, pp. 1071-1075. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00389.x. PMid:9711866.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-294x.19...

. Amplifications were performed following Nunes et al. (2013)Nunes, G.T., Leal, G.R., Campolina, C., Freitas, T.R.O., Efe, M.A. and Bugoni, L., 2013. Sex determination and sexual size dimorphism in two tropicbird species. Waterbirds, vol. 36, no. 3, p. 348-352.. Females were characterized by two bands on the gel, while maleswere characterized by the presence of only one band (see details in Nunes et al., 2013Nunes, G.T., Leal, G.R., Campolina, C., Freitas, T.R.O., Efe, M.A. and Bugoni, L., 2013. Sex determination and sexual size dimorphism in two tropicbird species. Waterbirds, vol. 36, no. 3, p. 348-352.). All adults were marked with numbered metal bands from the CEMAVE/ICMBio (Brazilian Banding Center).

The population was estimated by exhaustivecounts of active nests between August 2011 to January 2012and through census at sea with boats circulating around the islands of the archipelago.Three counts using binoculars were performed in 2010 (6 August – 3h15,9 August – 2h40 and 25 November – 1h). Data was also obtained during CEMAVE/ICMBio expeditions to colony-site of the Fernando de Noronha between 25 November and 05 December 2012 and to Abrolhos archipelago as part of a Monitoring Program coordinatedby AVIDEPA (Brazilian NGO) in August, September and November 2011 and in April, June and July 2012.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Breeding success was calculated by dividing the number of hatched eggs by the number of eggs laid (hatching success), and by dividing the number of chicks that departed nests by the number of chicks hatched (fledging success). Average incubation and fledging times were assumed to be 41 and 71 days (Schaffner, 1991Schaffner, F.C., 1991. Nest-site selection and nesting success of white-tailed tropicbirds (Phaethon lepturus) at Cayo Luis Pena, Puerto Rico. The Auk, vol. 108, pp. 911-922.), respectively. Nests where the egg was not incubated or which exceeded the maximum incubation time (43 days) were recorded as abandoned. Nests where the eggs or chicks disappeared before the minimum incubation and fledging times (40 and 65 days, respectively, Schaffner, 1991Schaffner, F.C., 1991. Nest-site selection and nesting success of white-tailed tropicbirds (Phaethon lepturus) at Cayo Luis Pena, Puerto Rico. The Auk, vol. 108, pp. 911-922.) were considered depredated.

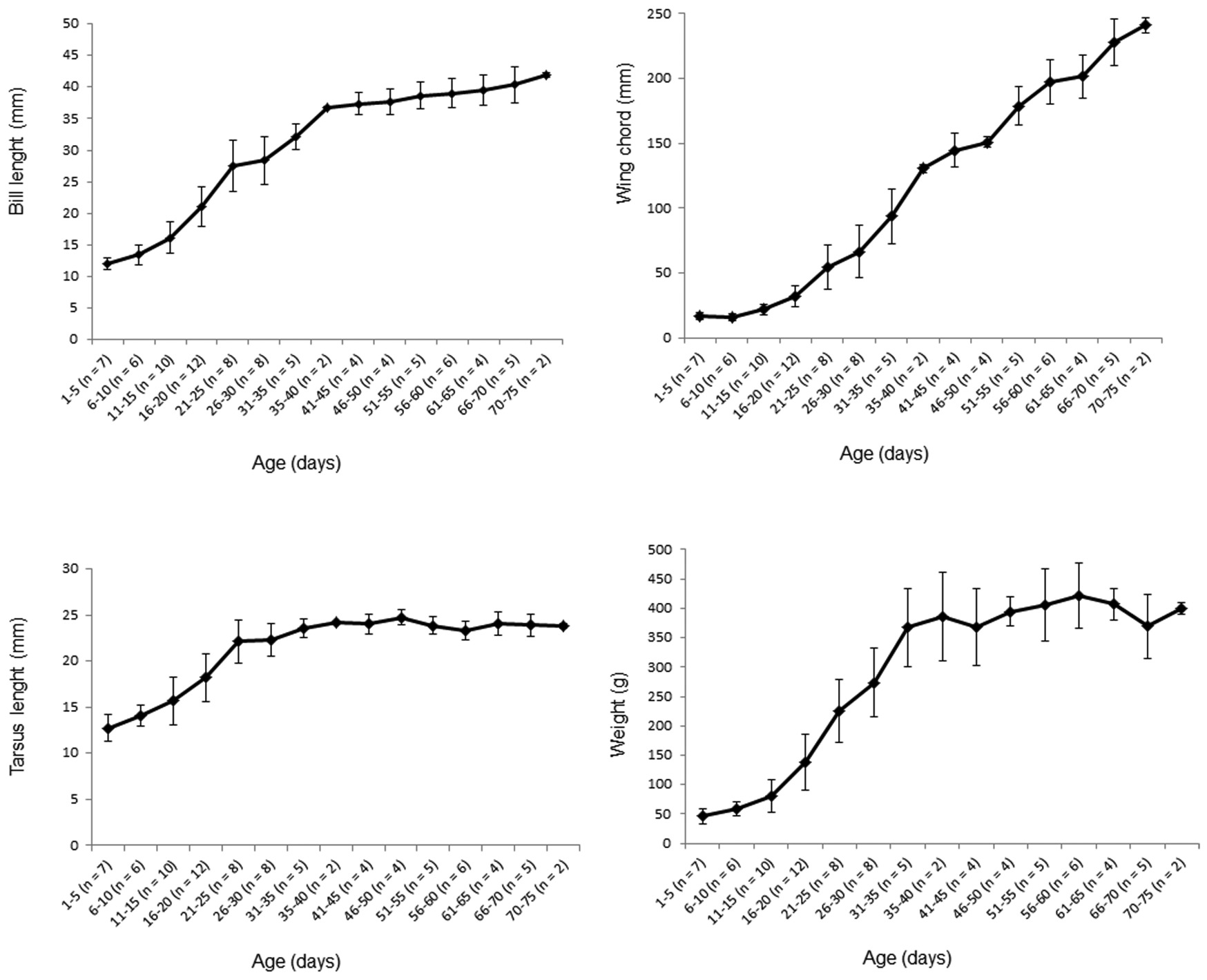

The growth curve of chicks was obtained using the mean values of bill length (measured in a straight line from the tip of the beak to where the feathering starts on the bird's forehead), tarsus length (measured from the inner bend of the tibio tarsal articulation to the base of the toes), wing chord (measured from the bend of the wing to the tip of the longest primary feathers with natural curvature) and weight of chicks with known hatching date. A life table based on 17 WTTB chicks (followed from birth to death) was created using the methods described by Brower and Zar (1998)Brower, J.E. and Zar, J.H., 1998. Field and laboratory methods for general ecology. Iowa: HMC Company. and Krebs (1999)Krebs, C.J., 1999. Ecological methodology. Menlo Pard: Addison Welsey Educational.. Such a table can be used to describe mortality rates (or survival) and reproduction by age, and to identifythe most vulnerable ages. Information on nest fidelity (the tendency to return to a previously occupied nest), mate fidelity (tendency topair with their previous mating partner) and age was obtained from birdsbanded in previous years by CEMAVE staff.

3 Results

3.1 Breeding biology

In most islands on Fernando de Noronha archipelago, birds lay only one egg in caves and burrows in cliffs. However, on Chapéu Island, the nests are on exposed ground among limestones pinnacles. On Abrolhos archipelago, WTTB nests were located in burrows on cliffs or burrows directly on rocks. Eggs (n = 43)measured 54.4 ± 2.1 mm in length, 38.1 ± 1.9 mm in width and 41.2 ± 4.5 g. Breeding was continuous, and nests with eggs and chicks were present throughout the study period (Figure 2).

Variation in the number of eggs and chicks of white tailed tropicbird (Phaethon lepturus) while breeding in the Chapéu’s island, Fernando de Noronha archipelago, Brazil between August 2011 to January 2012.

A total of 35 nests were monitored between August 2011and January 2012. Of these, seven were utilized more than oncein the same season. Hatching success was 40.5% and fledging success was 35.3%. Overall breeding success (hatching x fledging) was 14.3%, while 50.0% of the nests were depredated in the egg stage, 9.5% were abandoned in the egg stage and 26.2% were depredated in the chick stage. Incubation time, based on three eggs (with laying date and hatching date known) was 42 days. A single chick (with hatching date and departure date known) remained in the nest for 71 days. During nest monitoring on Chapéu Island, only one predation event was observed – that of a 34 days old chick by a land crab (Johngarthia lagostoma (H. Milne Edwards, 1837)). Feces of the exotic tegu lizard (Tupinambismerinae (Durimél & Bibron, 1839)) were also found on the Island.

The life table indicates that chicks had very high survival at 0-5 days old (93.8%) and 6-10 days old (100%), and that the critical period (qx= 0.273) is between 31 and 35 days old (Table 1). The growth curve of chicks indicates stabilization of tarsus and bill growth and a practically continuous growth of wing and weight until 60 days old (Figure 3).

Life table for White-tailed tropicbird (Phaethon lepturus) chicks, born in 2011 in the Fernando de Noronha archipelago, Brazil. nx = Number surviving to age x; lx = Proportion of surviving to age x; dx = Number dying between ages x and x+1; qx= Probability of dying between ages x and x+1; sx = Probability of surviving between age x and x+1.

Growth curves with mean values and error bar (SD) of bill, tarsus, wing and weight of White-tailed tropicbird (Phaethon lepturus) chicks in breeding season 2011, Chapéu’s Island, Fernando de Noronha archipelago, Brazil.

During November and December 2012, 14 nests were active (with egg or chick) out of the 35 nests that had been monitored the previous year. In addition to these, 11 new nests were recorded. On Abrolhos, three adult birds and two chicks were captured in three nests, in 2011. In 2012, two adult birds and two chicks were captured and one adult bird was recaptured, totaling two active nests (with chick).

In 2011, 10 banded birds were recaptured on Fernando de Noronha archipelago: five males and five females. Of these, one male and one female had been banded as chicks in 2009 and weretherefore breeding at two years old. The remaining eight recaptured birds had been banded as adults in 2009 (n = 4), in 2010 (n = 2) and in 2011 (n = 2). All recaptures occurred at the same locality where the birds had originally been banded, demonstrating some breeding site fidelity.

Between November and December 2012, six birds were recaptured on Fernando de Noronha. Five had been banded in 2011 when they were breeding, and one had been banded in 2009 as a chick. Of these, four were located in the same nests they had previously used. On Abrolhos, one adult bird banded in 2011 was recaptured in the same nest in 2012.

3.2 Population estimates

Based on active nests, the population of WTTB in Fernando de Noronha was estimated at 174 adult birds in 2010 and 128 adult birds in 2011. By census at sea, the largest count was 108 individuals recorded in Fernando de Noronha on the 06 August 2010 (other counts were 52 individuals on 09 August 2010 and 18 on 25 November 2010). In Abrolhos, six adult birds were recorded between 2011 and 2012, four of them in three different nests and two flying over the archipelago.

4 Discussion

Previous studies indicate that breeding success of colonial seabirds is mainly influenced by climatic variations (Ancona et al., 2011ANCONA, S., SÁNCHEZ-COLÓN, S., RODRÍGUEZ, C. and DRUMMOND, H., 2011. El Niño in the warm tropics: local sea temperature predicts breeding parameters and growth of blue-footed boobies. Journal of Animal Ecology, vol. 80, pp. 799-808.), food availability (Hamer et al., 1993HAMER, K.C., MONAGHAN, P., UTTLEY, J.D., WALTON, P. and BURNS, M.D., 1993. The influence of food supply on the breeding ecology of kittiwakes Rissa tridactyla in Shetland. Ibis, vol. 13, pp. 255-263.; Dearborn et al., 2001Dearborn, D.C., Anders, A.D. and Flint, E.N., 2001. Trends in reproductive success of Hawaiian seabirds: is guild membership a good criterion for choosing indicator species? Biological Conservation, vol. 101, no. 1, pp. 97-103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(01)00030-1.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(01)...

), introduction of exotic species (Russel and Le Corre, 2009RUSSELL, J.C. and LE CORRE, M., 2009. Introduced mammal impacts on seabirds in the Îles Éparses, Western Indian Ocean. Marine Ornithology, vol. 37, pp. 121-129.) and intra/interspecific competition (Coulson, 2001Coulson, J.C., 2001. Colonial breeding in seabirds. In: E.A. SCHREIBER and J. BURGER, eds. Biology of marine birds. Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 87-113.; Dobson and Madeiros, 2010DOBSON, A.F. and MADEIROS, J., 2010. Threats facing Bermuda’s breeding seabirds: measures to assist future breeding success. Proceedings of the Fourth International Partners in Flight Conference: Tundra to Tropics, pp. 223-226.). In cavity-nesting seabirds, cavity orientation can ameliorate micro-climate effects (e.g. Conner, 1975Conner, R.N., 1975. Orientation of entrances to wood-pecker nest cavities. The Auk, vol. 92, no. 2, pp. 371-374. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/4084566.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/4084566...

; Stauffer and Best, 1982Stauffer, D.F. and Best, L.B., 1982. Nest site selection by cavity-nesting birds of riparian habitats in Iowa. The Wilson Bulletin, vol. 94, pp. 329-337.). For WTTBs, breeding success has been observed to be affected by nest abandonment, intraspecific combats and predation by rats (Rattus rattus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Garnett and Crowley, 2000GARNETT, S.T. and CROWLEY, G.M., 2000. The action plan for Australian birds. Canberra: Environment Australia.; Sarmento et al., 2014Sarmento, R., Brito, D., Ladle, R.J., Leal, G.R. and Efe, M.A., 2014. Invasive house (Rattus rattus) and brown rats (Rattus norvegicus) threaten the viability of red-billed tropicbird (Phaethon aethereus) in Abrolhos National Park, Brazil. Tropical Conservation Science, vol. 7, pp. 614-627.) and crabs (Gecarcinus spp. and Ocypode spp.) (Schaffner, 1991Schaffner, F.C., 1991. Nest-site selection and nesting success of white-tailed tropicbirds (Phaethon lepturus) at Cayo Luis Pena, Puerto Rico. The Auk, vol. 108, pp. 911-922.; Phillips, 1987Phillips, N.J., 1987. The breeding of White-tailed Tropicbirds at Cousin Island, Seychelles. Phaethon lepturusThe Ibis, vol. 129, no. 1, pp. 10-24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-919X.1987.tb03156.x.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-919X.19...

). In this context, the unusual nest form (recorded previously only in Christmas Island – Stokes 1988Stokes, T., 1988. A review of the birds of Christmas Island, Indian Ocean. Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service Occasional Paper, no. 16.) which exposes birds to both predators and adverse weather conditions may be responsible for the low hatching and fledging success observed in this study.

Estimated hatching and fledging success in Fernando de Noronha was lower than Puerto Rico, Ascension Island and Cousin Island (Table 2). In all these areas nests have traditional characteristics, being formed in burrows and crevices and therefore providing some protection from predators and adverse weather conditions (Stonehouse, 1962Stonehouse, E., 1962. The tropic birds (Genus ) of Ascension Island. PhaethonThe Ibis, vol. 103, pp. 124-161.; Phillips, 1987Phillips, N.J., 1987. The breeding of White-tailed Tropicbirds at Cousin Island, Seychelles. Phaethon lepturusThe Ibis, vol. 129, no. 1, pp. 10-24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-919X.1987.tb03156.x.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-919X.19...

; Orta, 1992Orta, J., 1992, Family Phaethontidae. In: J. DEL HOYO, A. ELLIOTT and J. SARGATAL, eds. Handbook of the birds of the world. Vol. I. Ostrich to Ducks. Barcelona: Lynx Editions, pp. 280-289.). It is well known that in some colonies reproductive success varies as a function of habitat and nest-site choice, and that climatic events can affect the breeding success (Hamer et al., 2001Hamer, K.C., Schereiber, E.A. and Burger, J., 2001. Breeding biology, life histories, and life history-environment interactions in seabirds. In: E.A. SCHREIBER and J. BURGER, eds. Biology of marine birds. Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 217-161.). An open nest exposes the egg to predation and inclement weather, and may therefore decrease the probability of hatching (Mallory et al., 2009Mallory, M.L., Gaston, A.J., Forbes, M.R. and Gilchrist, H.G., 2009. Influence of weather on reproductive success of northern fulmars in the Canadian high Arctic. Polar Biology, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 529-538. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00300-008-0547-4.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00300-008-054...

; Hoegh-Guldberg and Bruno, 2010Hoegh-Guldberg, O. and Bruno, J.F., 2010. The impact of climate change on the world’s marine ecosystems. Science, vol. 328, no. 5985, pp. 1523-1528. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1189930. PMid:20558709.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.118993...

).

Egg dimensions (X̅ ± SD), hatching and fledging success obtained in this and other studies of White tailed tropicbirds (Phaethon lepturus).

Nest predation is an important and common cause of reproductive failures (Ricklefs, 1969Ricklefs, R.E., 1969. An analysis of nestling mortality in birds. Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology, vol. 9, no. 9, pp. 1-48. http://dx.doi.org/10.5479/si.00810282.9.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5479/si.00810282.9...

; Yang et al., 2014Yang, C., Møller, A.P., Ma, Z., Li, F. and Liang, W., 2014. Intensive nest predation by crabs produces source–sink dynamics in hosts and parasites. Journal für Ornithologie, vol. 155, no. 1, pp. 219-223. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10336-013-1003-y.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10336-013-100...

). We observed several chicks to unexpectedly ‘disappear’ from their nests on Fernando de Noronha, possibly as a consequence of predation by crabs (Shealer and Burger, 1992Shealer, D.A. and Burger, J., 1992. Differential responses of tropical Roseate Terns to aerial intruders throughout the nesting cycle. The Condor, vol. 94, no. 3, pp. 712-719. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1369256.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1369256...

). In the study area, chicks were more likely to die after the first month of life – a period in which we observed one chick being predated by a crab (J. lagostoma). Nest defense is often related to stage of breeding cycle (Lack, 1968Lack, D., 1968. Ecological adaptations for breedingin birds. London: Methuen.; Burger,1984Burger, J., 1984. Pattern, mechanism and adaptivesignificance of territoriality in the Herring Gull (Larus argentatusOmithol.). Monogr, vol. 34, pp. 1-92.; Kilpi, 1987KILPI, M., 1987. Do herring gulls (Larus argentatus) invest more in offspring defence as the breeding season advances? Ornis Fennica, vol. 64, pp. 16-20.), and the observed increase in vulnerability after the first month of life can be explained by adults spending shorter periods at the nest and longer periods engaged in prey capture (Sommerfeld and Hennicke, 2010Sommerfeld, J. and Hennicke, J.C., 2010. Comparison of trip duration, activity pattern and diving behaviour by Red-tailed Tropicbirds (. Phaethon rubricauda) during incubation and chick-rearingThe Emu, vol. 110, no. 1, pp. 78-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/MU09053.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/MU09053...

), leaving the chicks alone and potentially exposed to crab predators. However, starvation – a known cause of chick mortality (Boersma and Stokes, 1995Boersma, P.D. and Stokes, D.L., 1995. Mortality patterns, hatching asynchrony, and size asymmetry in Magellanic Penguin Spheniscus magellanicus chicks. In: P. DANN, I. NORMAN and P. REILLY, eds. The penguins: ecology and management. New South Wales: Surrey Beatty & Sons, pp. 3-25.) – cannot be ruled out, since this period also coincides with asudden increasein growth parameters (see Table 2).

The egg dimensions observed in this study were similar to those described in other isolated populations such as Cocos-Keeling Islands and the Aldabra Atoll (Table 2).

Seabirds usually reach sexual maturity after several years (Hamer et al., 2001Hamer, K.C., Schereiber, E.A. and Burger, J., 2001. Breeding biology, life histories, and life history-environment interactions in seabirds. In: E.A. SCHREIBER and J. BURGER, eds. Biology of marine birds. Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 217-161.). This extended ‘pre-reproductive’ period may be needed to develop efficient methods of feeding and locating prey (Irons, 1998Irons, D.B., 1998. Foraging area fidelity of individual seabirds in relation to tidal cycles and flock feeding. Ecology, vol. 79, no. 2, pp. 647-655.), for development of mating behavior and claiming a territory (Harrington, 1974Harrington, B.A., 1974. Colony visitation behavior and breeding ages of Sooty Terns (Sterna fuscata). Bird-Banding, vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 115-144. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/4512021.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/4512021...

; Nelson, 1978Nelson, J.B., 1978. The sulidae: gannets and boobies. Cambridge: Oxford University Press.; Hudson, 1985Hudson, P.J., 1985. Population parameters for the Atlantic Alcidae. In: D. NETTLESHIP and T. BIRKHEAD, eds. The Atlantic Alcidae. London: Academic Press. pp. 233-261.), or for attaining full physiological maturity (Ainley, 1978Ainley, D.G., 1978. Activity and social behavior patterns in non-breeding Adelie Penguins. The Condor, vol. 80, no. 2, pp. 138-146. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1367913.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1367913...

). Previous studies have estimated a very low probability of first breeding of P. rubricauda within the first one to two years of life, increasing in three and four year old birds (Doherty Junior et al., 2004Doherty JUNIOR, P.F., Schreiber, E.A., Nichols, J.D., Hines, J.E., Link, W.A., Schenk, G.A. and Schreiber, R.W., 2004. Testing life history predictions in a long-lived seabird : a population matrix approach with improved parameter estimation. Oikos, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 606-618. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0030-1299.2004.13119.x.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0030-1299.20...

). There are records of WTTBs breeding atfive and six years old (Harris, 1979Harris, M.P., 1979. Survival and ages of first breeding of Galápagos seabirds. Bird Banding, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 56-61. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/4512409.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/4512409...

). In contrast, our results indicate that WTTBs in Brazil can start breeding by the second year of life. Such early breeding may also be a contributing factor to the observed low reproductive success, since young breeding adults may lack breeding and/or foraging experience.

The recaptured individuals in our study indicated some philopatry and nest fidelity. In Fernando de Noronha and Abrolhos all recaptures occurred at the same site as the initial banding, and five individuals were found in the same nest on two consecutive years. Philopatry has been described in many seabirds, especially in monogamous birds with high longevity (Stenhouse and Robertson, 2005Stenhouse, I.J. and Robertson, G.J., 2005. Philopatry, site tenacity, mate fidelity, and adult survival in sabine’s gulls. Condor, vol. 107, no. 2, pp. 416-423.; Weimerskirch et al., 2005Weimerskirch, H., Lallemand, J. and Martin, J., 2005. Population sex ratio variation in a monogamous long-lived bird, the wandering albatross. Journal of Animal Ecology, vol. 74, no. 2, pp. 285-291. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2005.00922.x.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.20...

) such as the WTTB. The absence of islands with adequate sites to breed near these archipelagos (Coulson, 2001Coulson, J.C., 2001. Colonial breeding in seabirds. In: E.A. SCHREIBER and J. BURGER, eds. Biology of marine birds. Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 87-113.) may reinforce this behavior by limiting opportunities to establish new nesting sites.

Population size estimates of WTTBs are problematic due to the difficulty of accessing colonies, finding nests and counting birds, and because it is difficult to determine the optimal timing of visits; seasonally and in relation to the time of day (Lee and Walsh-McGehee, 2000Lee, D.S. and Walsh-Mcgehee, M., 2000. Population estimates, conservation concerns, and management of tropicbirds in the Western Atlantic. Caribbean Journal of Science, vol. 36, pp. 267-279.). The WTTB population of Fernando de Noronhahas been estimated at between 100 to 300 birds (Oren, 1984Oren, D.C., 1984. Resultados de uma nova expedição zoológica a Fernando de Noronha. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emilio Goeldi - Nova Série: Zoologia, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 19-44.; Schulz-Neto, 1995Schulz-Neto, A., 1995. Observação de aves no Parque Nacional Marinho de Fernando de Noronha: guia de campo. Brasília: Ministério do Meio Ambiente, dos Recursos Hídricos e da Amazônia legal.). Despite the population being listed as stable (Schulz-Neto 2004Schulz-Neto, A., 2004. Aves insulares do arquipélago de Fernando de Noronha. In: J.O. BRANCO, org. Aves marinhas e insulares brasileiras: bioecologia e conservação. Itajai: Univali, pp. 147-168.) and the number of birds counted in our study being within the range of previous population size estimates, there may be considerable temporal (yearly or longer) fluctuations in the number of adults in this population. A long term monitoring program that develops periodic and standardized censuses would therefore be desirable to assess any such fluctuations and identify their potential causes.

4.1 Conservation status

The WTTB is listed as threatened by the Brazilian Red List (BRASIL, 2003BRASIL. Ministério do Meio Ambiente – MMA, 2003 [viewed 14 September 2013]. Instrução normativa MMA nº 3, de 27 de maio de 2003. Divulga a relação de Espécies da Fauna Brasileira Ameaçadas de Extinção. Diário Oficial [online], Brasília, 28 maio. Available from: http://www.mma.gov.br/estruturas/179/_arquivos/179_05122008034002.pdf

http://www.mma.gov.br/estruturas/179/_ar...

) due to its low breeding success, to the limited number of breeding islands and the small population size. Interestingly, Johngarthia lagostoma – the crab observed preying on WTTB chicks - is also listed as threatened (BRASIL, 2003BRASIL. Ministério do Meio Ambiente – MMA, 2003 [viewed 14 September 2013]. Instrução normativa MMA nº 3, de 27 de maio de 2003. Divulga a relação de Espécies da Fauna Brasileira Ameaçadas de Extinção. Diário Oficial [online], Brasília, 28 maio. Available from: http://www.mma.gov.br/estruturas/179/_arquivos/179_05122008034002.pdf

http://www.mma.gov.br/estruturas/179/_ar...

; Coelho and Melo, 2008Coelho, P.A. and Melo, G.A.S., 2008. . In: Gecarcinus lagostomaA.B.M. MACHADO, G.M. DRUMMOND and A.P. PAGLIA, eds. Livro vermelho da fauna brasileira ameaçada de extinção. Brasília: Fundação Biodiversitas, pp. 274-275.), so any proposed conservation strategies should ideally avoid negative impacts on either species. The tegu lizard, by contrast, is an exotic species that is known to prey on eggs and young birds (Chiarello et al., 2010Chiarello, A.G., Srbek-Araujo, A.C., Del-Duque JUNIOR, H.J., COELHO, E.R. and ROCHA, C.F.D., 2010. Abundance of tegu lizards (Tupinambis merianae) in a remnant of the Brazilian Atlantic forest. Amphibia-Reptilia, vol. 31-4, no. 4, pp. 563-570. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/017353710X518441.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/017353710X5184...

), and may therefore represent a high threat (mainly on Chapéu Island where WTTBs lay their eggs on the ground). Thus, we suggest immediate actions to confirm tegu predation and, if verified, to eradicate this species from Chapeu Island.

Other exotic species (Rattus ratus, R. norvegicus (Berkenhout, 1769), Felis catus Linnaeus, 1758) are known to prey on WTTB eggs and chicks and are a threat to nests on the main island of the Fernando de Noronha archipelago. WTTBs were once considered common on this island (Oren, 1984Oren, D.C., 1984. Resultados de uma nova expedição zoológica a Fernando de Noronha. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emilio Goeldi - Nova Série: Zoologia, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 19-44.), but are now restricted to a few nests. This illustrates the need for better control and eradication of exotic species throughout the archipelago. Moreover, a continuous monitoring program of WTTBs in Fernando de Noronha should be immediately implemented to detect long term trends and to provide early warning of population decline.

Acknowledgements

This paper forms part of the MSc thesis of GRL and is supported by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Capes) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) grants (to GRL). MAE projects was supported by the CNPq (#474072/2010-0). We would like to thank Centro Nacional de Pesquisa e Conservação de Aves Silvestres (CEMAVE/ICMBio), Parque Nacional Marinho dos Abrolhos and Marinha do Brasil for authorizations for work. Fieldwork in Abrolhos archipelago was supported for C.M. Musso and Associação Vila-Velhense de Proteção Ambiental (AVIDEPA) staff to which we are extremely grateful. For discussion and suggestions we thank L. Bugoni and T. Mott.

-

(With 3 figures)

References

- Ainley, D.G., 1978. Activity and social behavior patterns in non-breeding Adelie Penguins. The Condor, vol. 80, no. 2, pp. 138-146. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1367913

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1367913 - Alves, V.S., Soares, A.B.A., Couto, G.S., RIBEIRO, A.B.B. and EFE, M.A., 1997. Aves do Arquipélago dos Abrolhos, Bahia, Brasil. Ararajuba, vol. 5-2, pp. 209-218.

- Alves, V.S., Soares, A.B.A. and Couto, G.S., RIBEIRO, A.B.B. and EFE, M.A., 2004. Aves marinhas de Abrolhos. In: J.O. BRANCO, org. Aves marinhas e insulares brasileiras: bioecologia e conservação. Itajai: Univali, pp. 213-232.

- ANCONA, S., SÁNCHEZ-COLÓN, S., RODRÍGUEZ, C. and DRUMMOND, H., 2011. El Niño in the warm tropics: local sea temperature predicts breeding parameters and growth of blue-footed boobies. Journal of Animal Ecology, vol. 80, pp. 799-808.

- Bartholomew, G.A., 1986. The role of History in Contemporary Biology. BioScience, vol. 36-35, pp. 324-329.

- Batistella, M., 1996. Espécies vegetais dominantes do Arquipélago de Fernando de Noronha: grupos ecológicos e repartição espacial. Acta Botanica Brasílica, vol. 10, pp. 223-235.

- BIRDLIFE INTERNATIONAL, 2012 [viewed 16 September 2013]. Phaethon lepturus. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species [online]. Available from: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/22696645/0

» http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/22696645/0 - Boersma, P.D. and Stokes, D.L., 1995. Mortality patterns, hatching asynchrony, and size asymmetry in Magellanic Penguin Spheniscus magellanicus chicks. In: P. DANN, I. NORMAN and P. REILLY, eds. The penguins: ecology and management. New South Wales: Surrey Beatty & Sons, pp. 3-25.

- Boyce, T.M., Zwick, M.E. and Aquadro, C.F., 1989. Mitochondrial DNA in the Bark Weevils: size, structure and heteroplasmy. Genetics, vol. 123, no. 4, pp. 825-836. PMid:2612897.

- BRASIL. Ministério do Meio Ambiente – MMA, 2003 [viewed 14 September 2013]. Instrução normativa MMA nº 3, de 27 de maio de 2003. Divulga a relação de Espécies da Fauna Brasileira Ameaçadas de Extinção. Diário Oficial [online], Brasília, 28 maio. Available from: http://www.mma.gov.br/estruturas/179/_arquivos/179_05122008034002.pdf

» http://www.mma.gov.br/estruturas/179/_arquivos/179_05122008034002.pdf - Brower, J.E. and Zar, J.H., 1998. Field and laboratory methods for general ecology. Iowa: HMC Company.

- Burger, J., 1984. Pattern, mechanism and adaptivesignificance of territoriality in the Herring Gull (Larus argentatusOmithol.). Monogr, vol. 34, pp. 1-92.

- Butchart, S.H., Stattersfield, A.J., Bennun, L.A., Shutes, S.M., Akçakaya, H.R., Baillie, J.E., STUART, S.N., HILTON-TAYLOR, C. and Mace, G.M., 2004. Measuring global trends in the status of biodiversity: Red List Indices for birds. PLoS Biology, vol. 2, no. 12, pp. e383. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0020383 PMid:15510230.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0020383 - Catry, T., Ramos, J.A., Monticelli, D., Bowler, J., Jupiter, T. and Le Corre, M., 2009. Demography and conservation of the white-tailed tropicbird . Phaethon lepturus on Aride Island, western Indian OceanJournal für Ornithologie, vol. 150, no. 3, pp. 661-669. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10336-009-0389-z

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10336-009-0389-z - Chiarello, A.G., Srbek-Araujo, A.C., Del-Duque JUNIOR, H.J., COELHO, E.R. and ROCHA, C.F.D., 2010. Abundance of tegu lizards (Tupinambis merianae) in a remnant of the Brazilian Atlantic forest. Amphibia-Reptilia, vol. 31-4, no. 4, pp. 563-570. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/017353710X518441

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/017353710X518441 - Coelho, P.A. and Melo, G.A.S., 2008. . In: Gecarcinus lagostomaA.B.M. MACHADO, G.M. DRUMMOND and A.P. PAGLIA, eds. Livro vermelho da fauna brasileira ameaçada de extinção. Brasília: Fundação Biodiversitas, pp. 274-275.

- Conner, R.N., 1975. Orientation of entrances to wood-pecker nest cavities. The Auk, vol. 92, no. 2, pp. 371-374. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/4084566

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/4084566 - Coulson, J.C., 2001. Colonial breeding in seabirds. In: E.A. SCHREIBER and J. BURGER, eds. Biology of marine birds. Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 87-113.

- Couto, G.S., INTERAMINENSE, L.J.L. and MORETTE, M.E., 2001. Primeiro registro de Boddaert, 1783 para o Brasil. Phaethon rubricaudaNattereria, vol. 2, pp. 24-25.

- Croxall, J.P., BUTCHART, S.H.M., LASCELLES, B., STATTERSFIELD, A.J., SULLIVAN, B., SYMES, A. and TAYLOR, P., 2012. Seabird conservation status, threats and priority actions: a global assessment. Bird Conservation International, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 1-34.

- Dearborn, D.C., Anders, A.D. and Flint, E.N., 2001. Trends in reproductive success of Hawaiian seabirds: is guild membership a good criterion for choosing indicator species? Biological Conservation, vol. 101, no. 1, pp. 97-103. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(01)00030-1

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(01)00030-1 - Diamond, A.W., 1975. The biology of tropicbirds at Aldabra Atoll, Indian Ocean. The Auk, vol. 92, no. 1, pp. 16-39. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/4084415

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/4084415 - DOBSON, A.F. and MADEIROS, J., 2010. Threats facing Bermuda’s breeding seabirds: measures to assist future breeding success. Proceedings of the Fourth International Partners in Flight Conference: Tundra to Tropics, pp. 223-226.

- Doherty JUNIOR, P.F., Schreiber, E.A., Nichols, J.D., Hines, J.E., Link, W.A., Schenk, G.A. and Schreiber, R.W., 2004. Testing life history predictions in a long-lived seabird : a population matrix approach with improved parameter estimation. Oikos, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 606-618. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0030-1299.2004.13119.x

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0030-1299.2004.13119.x - Efe, M.A., 2008. . In: Phaethon lepturusA.B.M. MACHADO, G.M. DRUMMOND and A.P. PAGLIA, eds. Livro vermelho da fauna brasileira ameaçada de extinção. Brasília: Fundação Biodiversitas. pp. 414-417.

- GARNETT, S.T. and CROWLEY, G.M., 2000. The action plan for Australian birds. Canberra: Environment Australia.

- Gaston, A.J. and Jones, I.L., 1998. The auks. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gibson-Hill, C.A., 1950. Notes on the birds of the Cocos-Keeling Islands. Bulletin of the Raffles Museum, vol. 22, pp. 212-270.

- Griffiths, R., Double, M.C., Orr, K. and Dawson, R.J., 1998. A DNA test to sex most birds. Molecular Ecology, vol. 7, no. 8, pp. 1071-1075. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00389.x PMid:9711866.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00389.x - HAMER, K.C., MONAGHAN, P., UTTLEY, J.D., WALTON, P. and BURNS, M.D., 1993. The influence of food supply on the breeding ecology of kittiwakes Rissa tridactyla in Shetland. Ibis, vol. 13, pp. 255-263.

- Hamer, K.C., Schereiber, E.A. and Burger, J., 2001. Breeding biology, life histories, and life history-environment interactions in seabirds. In: E.A. SCHREIBER and J. BURGER, eds. Biology of marine birds. Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 217-161.

- Harrington, B.A., 1974. Colony visitation behavior and breeding ages of Sooty Terns (Sterna fuscata). Bird-Banding, vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 115-144. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/4512021

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/4512021 - Harris, M.P., 1979. Survival and ages of first breeding of Galápagos seabirds. Bird Banding, vol. 50, no. 1, pp. 56-61. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/4512409

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/4512409 - Hoegh-Guldberg, O. and Bruno, J.F., 2010. The impact of climate change on the world’s marine ecosystems. Science, vol. 328, no. 5985, pp. 1523-1528. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1189930 PMid:20558709.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1189930 - Hudson, P.J., 1985. Population parameters for the Atlantic Alcidae. In: D. NETTLESHIP and T. BIRKHEAD, eds. The Atlantic Alcidae. London: Academic Press. pp. 233-261.

- INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DO MEIO AMBIENTE E DOS RECURSOS NATURAIS RENOVÁVEIS – IBAMA, 1990. Plano de Manejo do Parque Nacional Marinho de Fernando de Noronha. Brasília: FUNATURA.

- Irons, D.B., 1998. Foraging area fidelity of individual seabirds in relation to tidal cycles and flock feeding. Ecology, vol. 79, no. 2, pp. 647-655.

- Jones, H.P., TERSHY, B.R., ZAVALETA, E.S., CROLL, D.A., KEITT, B.S., FINKELSTEIN, M.E. and HOWALD, G.R., 2008. Severity of the effects of invasive rats on seabirds: a global review. Conservation Biology, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 16-26.

- KILPI, M., 1987. Do herring gulls (Larus argentatus) invest more in offspring defence as the breeding season advances? Ornis Fennica, vol. 64, pp. 16-20.

- Krebs, C.J., 1999. Ecological methodology. Menlo Pard: Addison Welsey Educational.

- Lack, D., 1968. Ecological adaptations for breedingin birds. London: Methuen.

- Lee, D.S. and Walsh-Mcgehee, M., 2000. Population estimates, conservation concerns, and management of tropicbirds in the Western Atlantic. Caribbean Journal of Science, vol. 36, pp. 267-279.

- Macedo, S.J., Montes, M.J.F., Lins, I.C. and Costa, K.M.P., 1988. Revizee. Programa de Avaliação do Potencial Sustentável dos Recursos Vivos da Zona Econômica Exclusiva, SCORE/NE. Recife: UFPE. 37 p. Relatório da Oceanografia Química.

- Mallory, M.L., Gaston, A.J., Forbes, M.R. and Gilchrist, H.G., 2009. Influence of weather on reproductive success of northern fulmars in the Canadian high Arctic. Polar Biology, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 529-538. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00300-008-0547-4

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00300-008-0547-4 - Nelson, J.B., 1978. The sulidae: gannets and boobies. Cambridge: Oxford University Press.

- Nordström, M., Laine, J., Ahola, M. and Korpimäki, E., 2004. Reduced nest defence intensity and improved breeding success in terns as responses to removal of non-native American mink. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, vol. 55, no. 5, pp. 454-460.

- Nunes, G.T., Leal, G.R., Campolina, C., Freitas, T.R.O., Efe, M.A. and Bugoni, L., 2013. Sex determination and sexual size dimorphism in two tropicbird species. Waterbirds, vol. 36, no. 3, p. 348-352.

- Oren, D.C., 1982. A avifauna do Arquipélago de Fernando de Noronha. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emilio Goeldi - Nova Série. Zoologia, vol. 118, pp. 1-22.

- Oren, D.C., 1984. Resultados de uma nova expedição zoológica a Fernando de Noronha. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emilio Goeldi - Nova Série: Zoologia, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 19-44.

- Orta, J., 1992, Family Phaethontidae. In: J. DEL HOYO, A. ELLIOTT and J. SARGATAL, eds. Handbook of the birds of the world. Vol. I. Ostrich to Ducks. Barcelona: Lynx Editions, pp. 280-289.

- Phillips, N.J., 1987. The breeding of White-tailed Tropicbirds at Cousin Island, Seychelles. Phaethon lepturusThe Ibis, vol. 129, no. 1, pp. 10-24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-919X.1987.tb03156.x

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-919X.1987.tb03156.x - PIACENTINI, V.D.Q., ALEIXO, A., AGNE, C.E., MAURÍCIO, G.N., PACHECO, J.F., BRAVO, G.A., BRITO, G.R.R., NAKA, L.N., OLMOS, F., POSSO, S., SILVEIRA, L.F., BETINI, G.S., CARRANO, E., FRANZ, I., LEES, A.C., LIMA, L.M., PIOLI, D., SCHUNCK, F., AMARAL, F.R., BENCKE, G.A., COHN-HAFT, M., FIGUEIREDO, L.F., STRAUBE, F.C. and CESARI, E., 2015. Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee/Lista comentada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos. Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia, vol. 23, pp. 90-298.

- Ramos, J.A., Bowler, J., Betts, M., Pacheco, C., Agombar, J., Bullock, I. and Monticelli, D., 2005. Productivity of white-tailed tropicbird on Aride Island, Seychelles. Waterbirds, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 405-410. http://dx.doi.org/10.1675/1524-4695(2005)28[405:POWTOA]2.0.CO;2

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1675/1524-4695(2005)28[405:POWTOA]2.0.CO;2 - Ricklefs, R.E., 1969. An analysis of nestling mortality in birds. Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology, vol. 9, no. 9, pp. 1-48. http://dx.doi.org/10.5479/si.00810282.9

» http://dx.doi.org/10.5479/si.00810282.9 - Ricklefs, R.E., 1996. A economia da natureza. 3rd ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan.

- RUSSELL, J.C. and LE CORRE, M., 2009. Introduced mammal impacts on seabirds in the Îles Éparses, Western Indian Ocean. Marine Ornithology, vol. 37, pp. 121-129.

- Sarmento, R., Brito, D., Ladle, R.J., Leal, G.R. and Efe, M.A., 2014. Invasive house (Rattus rattus) and brown rats (Rattus norvegicus) threaten the viability of red-billed tropicbird (Phaethon aethereus) in Abrolhos National Park, Brazil. Tropical Conservation Science, vol. 7, pp. 614-627.

- Schaffner, F.C., 1991. Nest-site selection and nesting success of white-tailed tropicbirds (Phaethon lepturus) at Cayo Luis Pena, Puerto Rico. The Auk, vol. 108, pp. 911-922.

- Schulz-Neto, A., 1995. Observação de aves no Parque Nacional Marinho de Fernando de Noronha: guia de campo. Brasília: Ministério do Meio Ambiente, dos Recursos Hídricos e da Amazônia legal.

- Schulz-Neto, A., 2004. Aves insulares do arquipélago de Fernando de Noronha. In: J.O. BRANCO, org. Aves marinhas e insulares brasileiras: bioecologia e conservação. Itajai: Univali, pp. 147-168.

- Shealer, D.A. and Burger, J., 1992. Differential responses of tropical Roseate Terns to aerial intruders throughout the nesting cycle. The Condor, vol. 94, no. 3, pp. 712-719. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1369256

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1369256 - Sommerfeld, J. and Hennicke, J.C., 2010. Comparison of trip duration, activity pattern and diving behaviour by Red-tailed Tropicbirds (. Phaethon rubricauda) during incubation and chick-rearingThe Emu, vol. 110, no. 1, pp. 78-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/MU09053

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/MU09053 - Stauffer, D.F. and Best, L.B., 1982. Nest site selection by cavity-nesting birds of riparian habitats in Iowa. The Wilson Bulletin, vol. 94, pp. 329-337.

- Stenhouse, I.J. and Robertson, G.J., 2005. Philopatry, site tenacity, mate fidelity, and adult survival in sabine’s gulls. Condor, vol. 107, no. 2, pp. 416-423.

- Stokes, T., 1988. A review of the birds of Christmas Island, Indian Ocean. Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service Occasional Paper, no. 16.

- Stonehouse, E., 1962. The tropic birds (Genus ) of Ascension Island. PhaethonThe Ibis, vol. 103, pp. 124-161.

- Weimerskirch, H., 2001. Seabird demography and its relationship with the marine environment. In: E.A. SCHREIBER and J. BURGER, eds. Biology of marine birds. Boca Raton: CRC Press, pp. 113-132.

- Weimerskirch, H., Lallemand, J. and Martin, J., 2005. Population sex ratio variation in a monogamous long-lived bird, the wandering albatross. Journal of Animal Ecology, vol. 74, no. 2, pp. 285-291. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2005.00922.x

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2005.00922.x - Whittam, R.M. and Leonard, M.L., 2000. Characteristics of predators and offspring influence nest defense by Arctic and Common Terns. Condor, vol. 102, no. 2, pp. 301-306.

- Yang, C., Møller, A.P., Ma, Z., Li, F. and Liang, W., 2014. Intensive nest predation by crabs produces source–sink dynamics in hosts and parasites. Journal für Ornithologie, vol. 155, no. 1, pp. 219-223. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10336-013-1003-y

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10336-013-1003-y

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

19 Apr 2016 -

Date of issue

Jul-Sep 2016

History

-

Received

16 Aug 2014 -

Accepted

29 Apr 2015