Abstract

The presence of airborne fungi in Intensive Care Unit (ICUs) is associated with increased nosocomial infections. The aim of this study was the isolation and identification of airborne fungi presented in an ICU from the University Hospital of Pelotas – RS, with the attempt to know the place’s environmental microbiota. 40 Petri plates with Sabouraud Dextrose Agar were exposed to an environment of an ICU, where samples were collected in strategic places during morning and afternoon periods for ten days. Seven fungi genera were identified: Penicillium spp. (15.18%), genus with the higher frequency, followed by Aspergillus spp., Cladosporium spp., Fusarium spp., Paecelomyces spp., Curvularia spp., Alternaria spp., Zygomycetes and sterile mycelium. The most predominant fungi genus were Aspergillus spp. (13.92%) in the morning and Cladosporium spp. (13.92%) in the afternoon. Due to their involvement in different diseases, the identified fungi genera can be classified as potential pathogens of inpatients. These results reinforce the need of monitoring the environmental microorganisms with high frequency and efficiently in health institutions.

Keywords:

hospital; ICU; air quality; infection

Resumo

A presença de fungos anemófilos nas UTIs está associada com o aumento de infecções nosocomiais. O objetivo deste estudo foi isolar e identificar quais os principais fungos anemófilos presentes em uma Unidade de Terapia Intensiva (UTI) de um Hospital Universitário de Pelotas – RS, na tentativa de conhecer a microbiota ambiental do local. Através de 40 placas de Petri com Agar Sabouraud dextrose expostas no ambiente de UTI foram coletadas amostras por exposição em locais estratégicos durante períodos da manhã e tarde por dez dias. Sete gêneros fúngicos foram identificados: Penicillium spp. (15,18%), o gênero de maior frequência, seguido de Aspergillus spp., Cladosporium spp., Fusarium spp., Paecelomyces spp., Curvularia spp., Alternaria spp., além de Zigomicetos e micélios estéreis. Houve predomínio de Aspergillus spp. (13,92%) pela manhã e Cladosporium spp. (13,92%) a tarde. Por estarem envolvidos em diferentes enfermidades, os gêneros identificados podem ser classificados como patógenos em potencial aos pacientes internados. Estes resultados reforçam a necessidade de um monitoramento dos micro-organismos ambientais com maior freqüência e eficiência nas instituições de saúde.

Palavras-chave:

hospital; UTI; qualidade do ar; infecção

1. Introduction

Fungi are ubiquitous organisms widely distributed in the environment, it can be found in the plants, animals, soil, water and air (Carmo et al., 2007CARMO, E.S., BELÉM, L.F., CATÃO, R.M., LIMA, E.O., SILVEIRA, I.L. and SOARES, L.H.M., 2007. Microbiota fúngica presente em diversos setores de um hospital público em Campina Grande – PB. Revista Brasileira de Análises Clínicas, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 213-216.). These microorganisms are carried through water, insects, humans and animals, having the ability to disperse through the atmospheric air, being called airborne (Mezzari et al., 2003MEZZARI, A., PERIN, C., SANTOS JÚNIOR, S.A., BERND, L.A.G. and GESU, G., 2003. Os fungos anemófilos e sensibilização em indivíduos atópicos em Porto Alegre, RS. Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira, vol. 49, no. 3, pp. 270-273. PMid:14666351. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-42302003000300030.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-42302003...

).

Invasive mould infections represent a threat for high-risk patients hospitalized in Intensive Care Unit (ICU). Hospital infections caused by fungi have been frequently reported in hospitalized patients, with a high morbidity and mortality, making it increasingly important to the awareness of air quality. It can be estimated that in Brazil, the mortalities’ rates referring to infections associated to the health care, reach 38.4% of the hospitalized patients (Souza et al., 2015SOUZA, E.S., BELEI, R.A., CARRILHO, C.M.D.M., MATSUO, T., YAMADA-OGATTA, S.F., ANDRADE, G., PERUGINI, M.R.E., PIERI, F.M., DESSUNTI, E.M. and KERBAUY, G., 2015. Mortality and risks related to healthcare-associated infection. Text Context Nursing, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 220-228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0104-07072015002940013.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0104-070720150...

), meanwhile, as reported worldwide, from each 100 hospitalized patients, seven acquired infection associated to health care in development countries and ten in under development countries (WHO, 2011WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION – WHO, 2011. Report on the burden of endemic health care-associated infection worldwide: clean careis safer care. Geneva: WHO.).

Many hospital acquired infections are exogenously due to the increased use of air conditioning systems, which together with the accumulation of moisture are a great source of fungal spread (Martins-Diniz et al., 2005MARTINS-DINIZ, J.N., SILVA, R.A.M., MIRANDA, E.T. and MENDES-GIANNINI, M.J.S., 2005. Monitoramento de fungos anemófilos e de leveduras em unidade hospitalar. Revista de Saude Publica, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 398-405. PMid:15997315. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-89102005000300010. ; Colombo, 2000COLOMBO, A.L., 2000. Epidemiology and treatment of hematogenous candidiasis: a Brazilian perspective. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 113-118. PMid:10934493.; Pfaller, 1996PFALLER, M.A., 1996. Nosocomial candidiasis: emerging, species, reservoir and modes of transmission. Clinical Infectious Diseases, vol. 22, no. 2, suppl. 2, pp. 89-94. PMid:8722834. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/clinids/22.Supplement_2.S89.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/clinids/22.Sup...

).

Although, fungal spores have the capacity to develop into different environments, they are considered inoffensive in immunocompetent subjects, but fatal in hospital inpatients receiving imunosuppressive medication (Afshari et al., 2013AFSHARI, M.A., RIAZIPOUR, M., KACHUEI, R., TEIMOORI, M. and EINOLLAHI, B., 2013. A qualitative and quantitative study monitoring airborne fungal flora in the kidney transplant unit. Nephro-Urology Monthly, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 736-740. PMid:23841036. http://dx.doi.org/10.5812/numonthly.5379.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5812/numonthly.5379...

). It should be considered factors such as the fungal concentration, genus and species diversity, as well as their distribution characteristics in the environment, as shocking when considering the immunocompromised patients’condition (Zhang et al., 2015ZHANG, H.L., FENG, H.H., FANG, Z.L., WANG, B.D. and LI, D., 2015. Airborne fungal aerosol concentration and distribution characteristics in air- conditioned wards. Huan Jing Ke Xue, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 1234-1240. PMid:26164895.).

There are several reports in hospitalized patients affected by mycoses caused by airborne filamentous fungi present in the environment (Peckham et al., 2016PECKHAM, D., WILLIAMS, K., WYNNE, S., DENTON, M., POLLARD, K. and BARTON, R., 2016. Fungal contamination of nebuliser devices used by people with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 74-77. PMid:26104996. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcf.2015.06.004.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcf.2015.06....

; Caggiano et al., 2014CAGGIANO, G., NAPOLI, C., CORETTI, C., LOVERO, G., SCARAFILE, G., GIGLIO, O. and MONTAGNA, M.T., 2014. Mold contamination in a controlled hospital environment: a 3-year surveillance in southern Italy. BMC Infectious Diseases, no. 14, p. 595. PMid:25398412. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12879-014-0595-z.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12879-014-059...

; Shams-Ghahfarokhi et al., 2014SHAMS-GHAHFAROKHI, M., AGHAEI-GHAREHBOLAGH, S., ASLANI, N. and RAZZAGHI-ABYANEH, M., 2014. Investigation on distribution of airborne fungi in outdoor environment in Tehran, Iran. Journal of Environmental Health Science and Engineering, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 54-61. PMid:24588901. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/2052-336X-12-54.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/2052-336X-12-5...

), meanwhile in Brazil, few studies (Flores and Onofre, 2010FLORES, L.H. and ONOFRE, S.B., 2010. Determinação da presença de fungos anemófilos e leveduras em unidade de saúde da cidade de Francisco Beltrão – PR. Revista de Saúde e Biologia, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 22-26.; Lobato et al., 2009LOBATO, R.C., VARGAS, V.S. and SILVEIRA, E.S., 2009. Sazonalidade e prevalência de fungos anemófilos em ambiente hospitalar no sul do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Revista da Faculdade de Ciências Médicas de Sorocaba, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 21-28.; Carmo et al., 2007CARMO, E.S., BELÉM, L.F., CATÃO, R.M., LIMA, E.O., SILVEIRA, I.L. and SOARES, L.H.M., 2007. Microbiota fúngica presente em diversos setores de um hospital público em Campina Grande – PB. Revista Brasileira de Análises Clínicas, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 213-216.; Martins-Diniz et al., 2005MARTINS-DINIZ, J.N., SILVA, R.A.M., MIRANDA, E.T. and MENDES-GIANNINI, M.J.S., 2005. Monitoramento de fungos anemófilos e de leveduras em unidade hospitalar. Revista de Saude Publica, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 398-405. PMid:15997315. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-89102005000300010. ) characterizing the airborne fungi microbiota in the ICUsʼ environment, being an important knowledge for control strategies. The aim of this study was the isolation and identification of airborne fungi in an ICU from the University Hospital of Pelotas (RS – Brazil).

2. Material and Methods

The survey of the airborne fungi in the ICU was performed at the University Hospital of Pelotas, RS, during the months from September to November. For the analysis, ten samples were collected through the Sedimentation Plate Method using Sabouraud Dextrose Agar Medium. For collection, eight dishes were exposed each day, for a 20 minutes period. Dishes were located under three room air-conditioners, having one air-conditioner in each room and also located where hospital materials are disposed, at approximately one meter height above ground (Flores and Onofre, 2010FLORES, L.H. and ONOFRE, S.B., 2010. Determinação da presença de fungos anemófilos e leveduras em unidade de saúde da cidade de Francisco Beltrão – PR. Revista de Saúde e Biologia, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 22-26.; Carmo et al., 2007CARMO, E.S., BELÉM, L.F., CATÃO, R.M., LIMA, E.O., SILVEIRA, I.L. and SOARES, L.H.M., 2007. Microbiota fúngica presente em diversos setores de um hospital público em Campina Grande – PB. Revista Brasileira de Análises Clínicas, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 213-216.).

For each day of the week, four samples from the morning period and four samples from the afternoon period were collected, totalizing 40 plates during the ten days of study (20 plates in the morning and 20 plates in the afternoon). Two samples were collected in one day from a period of five days, in other words, there were collection of samples in the morning and afternoon shifts, in the same day of the week, and each day corresponded with a different day of the week. Two sampling collection periods were performed, because general cleaning and sanitation of the place was performed in one hour before taking the samples in the same two studied periods.

After the plates were collected, they were incubated at 25 °C for seven days. The identification was performed through visualization of the macro and micromorphology characteristics of the growing colonies and the production of blades with visualization Lactophenol cotton blue and slide culture between blades when needed (Sidrim and Rocha, 2004SIDRIM, J.J.C. and ROCHA, M.F.G., 2004. Micologia médica à luz de autores contemporâneos. Rio de Janeiro: Guanaba Koogan. 396 p.).

3. Results

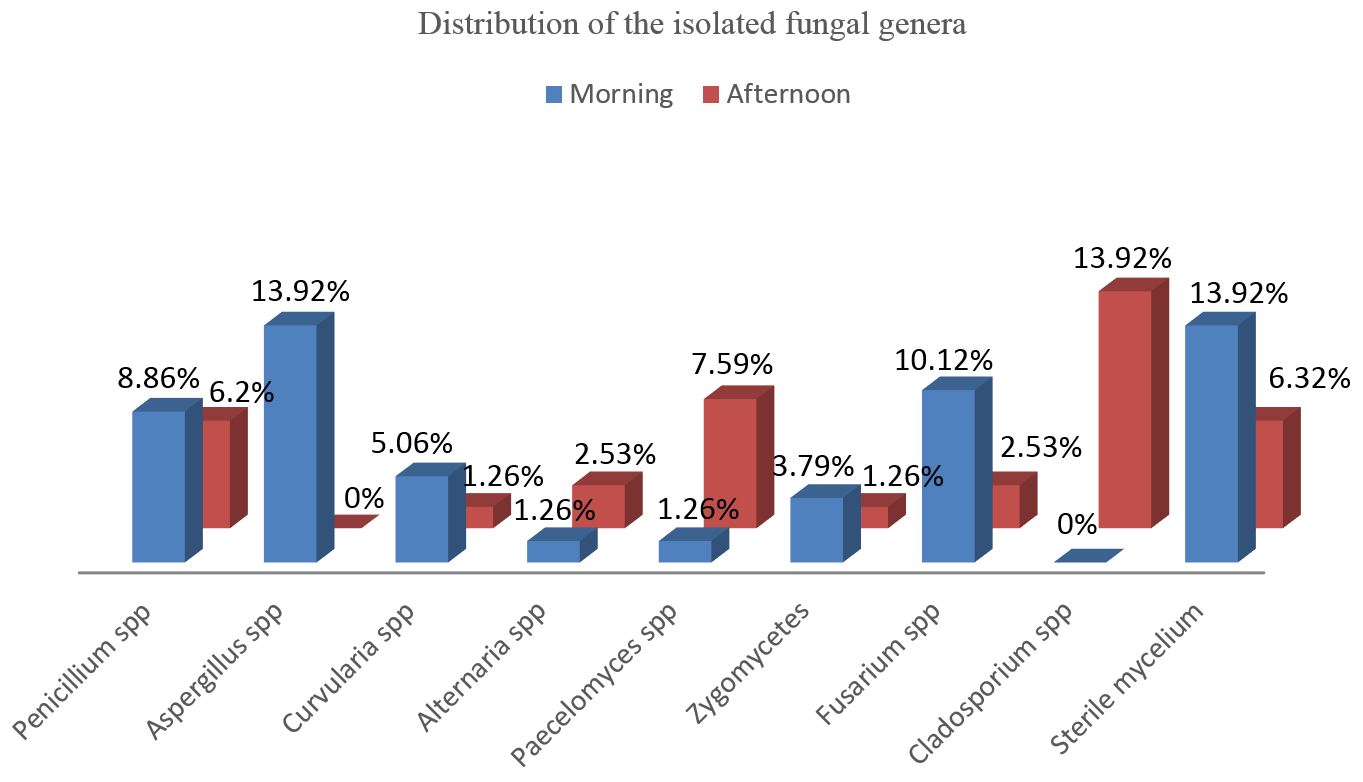

From the 40 collected plates exposed into the ICU’s environment, 33 plates (82.5%) showed growth of 79 filamentous fungi colonies. The filamentous genera were established in the Figure 1.

Distribution of the isolated fungal genera from the Intensive Care Unit at the Pelotas University Hospital according to the time from collection.

From the 20 collected plates on the morning period, 15 (75%) presented fungal growth and from the 20 plates of the afternoon period, 18 (90%) showed fungal growth. Higher fungal isolation was shown on the afternoon period.

Seven fungal genera were identified (Figure 1) being: Penicillium spp., Aspergillus spp., Cladosporium spp., Fusarium spp., Paecelomyces spp., Curvularia spp., Alternaria spp. and by Zygomycetes and sterile mycelium.

Aspergillus spp. (13.92%) was the most predominant fungi genus in the morning period and the Cladosporium spp. genus (13.92%) in the afternoon period, both were identified in one of the two evaluated shifts.

4. Discussion

For many years hospital fungal isolation has been reported such is the case of Aspergillus spp., Penicillium spp., Cladophialophora spp. and Fusarium spp. yet related with the Unit construction and renovation, providing conditions for the appearance of this kind of microorganisms in such places (El-Sharkawy and Noweir, 2014EL-SHARKAWY, M.F. and NOWEIR, M.E., 2014. Indoor air quality levels in a University Hospital in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. Journal of Family & Community Medicine, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 39-47. PMid:24696632. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/2230-8229.128778.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/2230-8229.1287...

; Sautour et al., 2007SAUTOUR, M., SIXT, N., DALLE, F., L’OLLIVIER, C., CALINON, C., FOURQUENET, V., THIBAUT, C., JURY, H., LAFON, I., AHO, S., COUILLAULT, G., VAGNER, O., CUISENIER, B., BESANCENOT, J.P., CAILLOT, D. and BONNIN, A., 2007. Prospective survey of indoor fungal contamination in hospital during a period of building construction. The Journal of Hospital Infection, vol. 67, no. 4, pp. 367-373. PMid:18037534. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2007.09.013.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2007.09...

; Martins-Diniz et al., 2005MARTINS-DINIZ, J.N., SILVA, R.A.M., MIRANDA, E.T. and MENDES-GIANNINI, M.J.S., 2005. Monitoramento de fungos anemófilos e de leveduras em unidade hospitalar. Revista de Saude Publica, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 398-405. PMid:15997315. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-89102005000300010. ; Iwen et al., 1994IWEN, P.C., DAVIS, J.C., REED, E.C., WINFIELD, B.A. and HINRICHS, S.H., 1994. Airborne fungal spore monitoring in a protective environment during hospital construction, and correlation with an outbreak of invasive aspergillosis. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, vol. 15, no. 5, pp. 303-306. PMid:8077640. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/30146558.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/30146558...

).

Considered potentially pathogenic, the occurrence of the genera Penicillium, Aspergillus and Cladosporium, which stood out in this study, are reported as predominant in the hospital environment by others authors (Melo et al., 2009MELO, L.L.S., LIMA, A.M.C., DAMASCENO, C.A.V. and VIEIRA, A.L.P., 2009. Flora fúngica no ambiente da Unidade de Terapia Intensiva Pediátrica e Neonatal em hospital terciário. Revista Paulista de Pediatria, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 303-308. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-05822009000300011.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-05822009...

; Martins-Diniz et al., 2005MARTINS-DINIZ, J.N., SILVA, R.A.M., MIRANDA, E.T. and MENDES-GIANNINI, M.J.S., 2005. Monitoramento de fungos anemófilos e de leveduras em unidade hospitalar. Revista de Saude Publica, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 398-405. PMid:15997315. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-89102005000300010. ). The fact that Aspergillus ssp. and Cladosporium ssp., were isolated only in one of the shifts is probably due, by the different hospital’s staff and routines in each period and by the abiotic conditions in which this experiment was done (Melo et al., 2009MELO, L.L.S., LIMA, A.M.C., DAMASCENO, C.A.V. and VIEIRA, A.L.P., 2009. Flora fúngica no ambiente da Unidade de Terapia Intensiva Pediátrica e Neonatal em hospital terciário. Revista Paulista de Pediatria, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 303-308. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-05822009000300011.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-05822009...

; Bernardi and Nascimento, 2005BERNARDI, E. and NASCIMENTO, J.S., 2005. Fungos anemófilos na praia do Laranjal, Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Arquivos do Instituto Biologico, vol. 72, no. 1, pp. 93-97.; Mezzari et al., 2003MEZZARI, A., PERIN, C., SANTOS JÚNIOR, S.A., BERND, L.A.G. and GESU, G., 2003. Os fungos anemófilos e sensibilização em indivíduos atópicos em Porto Alegre, RS. Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira, vol. 49, no. 3, pp. 270-273. PMid:14666351. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-42302003000300030.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-42302003...

).

Despite the cleaning and sanitizing procedures realized according to the normative instructions, 82.5% of the isolates using Petri plates is a high rate to be observed in a hospital unit, mainly in an ICU. During the isolates’ perform, the genus Penicilium was the most isolated fungi, meanwhile, a moderate frequency in the morning (8.86%) and in the afternoon (6.32%) periods was observed. Even so its presence becomes relevant by being involved in reported cases of disseminated infections (Ye et al., 2015YE, F., LUO, Q., ZHOU, Y., XIE, J., ZENG, Q., CHEN, G., SU, D. and CHEN, R., 2015. Disseminated penicilliosis marneffei in immunocompetent patients: a report of two cases. Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 161-165. PMid:25560026. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0255-0857.148433.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0255-0857.1484...

), multiple brain abscesses (Noritomi et al., 2005NORITOMI, D.T., BUB, G.L., BEER, I., SILVA, A.S.F., CLEVA, R. and GAMA-RODRIGUES, J.J., 2005. Multiple brain abscesses due to Penicillium spp. infection. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de Sao Paulo, vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 167-170. PMid:16021292. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0036-46652005000300010.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0036-46652005...

), peritonitis (Böhlke et al., 2007BÖHLKE, M., SOUZA, P.A., MENEZES, A.M.D., ROTH, J.M. and KRAMER, L.R., 2007. Peritonitis due to Penicillium and Enterobacter in a patient receiving continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 166-168. PMid:17625749. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-86702007000100035.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-86702007...

) and pneumonia in immunocompromised patients (Oshikata et al., 2013OSHIKATA, C., TSURIKISAWA, N., SAITO, A., WATANABE, M., KAMATA, Y., TANAKA, M., TSUBURAI, T., MITOMI, H., TAKATORI, K., YASUEDA, H. and AKIYAMA, K., 2013. Fatal pneumonia caused by Penicillium digitatum: a case report. BMC Pulmonary Medicine, vol. 13, no. 2013, pp. 13-16. PMid:23522080. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2466-13-16.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2466-13-1...

).

In Brazil, similar studies have been conducted at various locations, including Campina Grande (PB), Francisco Beltrão (PR), Rio Grande (RS) and Pouso Alegre (MG). In these cities, the most frequently isolated genus was Penicillium spp. varying in frequency from 40% to 93.3% (Flores and Onofre, 2010FLORES, L.H. and ONOFRE, S.B., 2010. Determinação da presença de fungos anemófilos e leveduras em unidade de saúde da cidade de Francisco Beltrão – PR. Revista de Saúde e Biologia, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 22-26.; Souza Júnior and Vieira, 2010SOUZA JÚNIOR, U.P. and VIEIRA, K.V.M., 2010. Microbiota fúngica anemófila de hospitais da rede pública da cidade de Campina Grande, PB. Revista de Biologia e Farmácia, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 102-116.; Melo et al., 2009MELO, L.L.S., LIMA, A.M.C., DAMASCENO, C.A.V. and VIEIRA, A.L.P., 2009. Flora fúngica no ambiente da Unidade de Terapia Intensiva Pediátrica e Neonatal em hospital terciário. Revista Paulista de Pediatria, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 303-308. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-05822009000300011.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-05822009...

; Lobato et al., 2009LOBATO, R.C., VARGAS, V.S. and SILVEIRA, E.S., 2009. Sazonalidade e prevalência de fungos anemófilos em ambiente hospitalar no sul do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Revista da Faculdade de Ciências Médicas de Sorocaba, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 21-28.; Carmo et al., 2007CARMO, E.S., BELÉM, L.F., CATÃO, R.M., LIMA, E.O., SILVEIRA, I.L. and SOARES, L.H.M., 2007. Microbiota fúngica presente em diversos setores de um hospital público em Campina Grande – PB. Revista Brasileira de Análises Clínicas, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 213-216.). These frequency results were higher than those observed in this study, however according that Penicillium spp. was also the most frequently isolated genera, can be associated with the different atmospheric conditions and immunologic status of the patients in the execution period of the different researches.

Regarding that Aspergillus, is a fungus genus with a worldwide distribution, the most common species include A. flavus and A. fumigatus (Lacaz et al., 2002LACAZ, C.S., PORTO, E., MARTINS, J.E.C., VACCARI, E.M.H. and MELO, N.T., 2002. Tratado de micologia médica. 9th ed. São Paulo: Sarvier. 1104 p.). Aspergilosis is related with different syndromes that can be manifest as allergic reactions or as invasive forms, otomycosis, endocarditis, osteomyelitis and skin infections, among others (Wanke et al., 2000WANKE, B., LAZÉRA, M.S. and NUCCI, M., 2000. Fungal infections in the immunocompromised host. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, vol. 95, no. 1, suppl. 1, pp. 153-158. PMid:11142705. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02762000000700025.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02762000...

). The genus Aspergillus spp., was reported by Panagopoulou et al. (2002)PANAGOPOULOU, P., FILIOTI, J., PETRIKKOS, G., GIAKOUPPI, P., ANATOLIOTAKI, M., FARMAKI, E., KANTA, A., APOSTOLAKOU, H., AVLAMI, A., SAMONIS, G. and ROILIDES, E., 2002. Environmental surveillance of filamentous fungi in three tertiary care hospitals in Greece. The Journal of Hospital Infection, vol. 52, no. 3, pp. 185-191. PMid:12419271. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/jhin.2002.1298.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/jhin.2002.1298...

with a higher frequency than the observed in this study. When evaluating three hospitals in Greece for the presence of airborne fungi, the authors recorded the presence of this genus in 70.55% of their samples.

Lugauskas and Krikštaponis (2004)LUGAUSKAS, A. and KRIKŠTAPONIS, A., 2004. Filamentous fungi isolated in hospitals and some medical institutions in Lithuania. Indoor and Built Environment, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 101-108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1420326X04040936.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1420326X040409...

investigated the diversity of airborne fungi at hospitals in Lithuania and made the isolation of 41 genera, including Penicillium spp., as the most predominated species, followed by Aspergillus spp., Acremonium spp., Paecilomyces spp., Mucor spp. and Cladosporium spp. Their results were similar to those found in our study with the exception of the genera Acremonium spp. and Mucor spp.

Cladosporium spp. is a dematiaceous fungus, that contains melanin in their cellular walls, which brings them a dark color in their spores and hyphae, associated most of the time to the microorganism’s virulence (Revankar, 2007REVANKAR, S.G., 2007. Dematiaceous fungi. Mycoses, vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 91-101. PMid:17305771. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0507.2006.01331.x.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0507.20...

), causes mainly infections of the central nervous system such as brain abscess between others (Freitas et al., 1997FREITAS, A., PEDRAL-SAMPAIO, D.B., ESPINHEIRA NOGUEIRA, L., DALTRO, E., SAMPAIO, J., ATHANÁSIO, P., LACAZ, C. and BADARÓ, R., 1997. Cladophialophora bantiana (Previously Cladosporium trichoides): first report of a case in Brazil. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 1, no. 6, pp. 313-316. PMid:11105153.; Goel et al., 1992GOEL, A., SATOSKAR, A., DESAI, A.P. and PANDYA, S.K., 1992. Brain abscess caused by Cladosporium trichoides. British Journal of Neurosurgery, vol. 6, no. 6, pp. 591-593. PMid:1472326. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02688699209002378.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02688699209002...

). Mainly in relation to the genus Cladosporium, its frequency it’s also elevated in relation to the hospital environment as observed by Diongue et al. (2015)DIONGUE, K., BADIANE, A.S., SECK, M.C., NDIAYE, M., DIALLO, M.A., DIALLO, S., SY, O., NDIAYE, J.L., FAYE, B., NDIR, O. and NDIAYE, D., 2015. Qualitative fungal composition of services at risk of nosocomial infections at Aristide Le Dantec Hospital (Dakar). Journal de Mycologie Médicale, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 39-43. PMid:25499807. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mycmed.2014.10.020. who obtained a percentage of 91.1% of all isolates related to this genus in a hospital ward. Apparently, Cladosporium spp. is associated with damages in the respiratory function, as demonstrated by Chen et al. (2014)CHEN, B.Y., CHAO, H., WU, C.F., KIM, H., HONDA, Y. and GUO, Y.L., 2014. High ambient Cladosporium spores were associated with reduced lung function in schoolchildren in a longitudinal study. The Science of the Total Environment, vol. 485, pp. 370-376. PMid:24607630. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.01.078.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.20...

associating the children exposition to the fungi having a reduction in the pulmonary function. These findings are higher in children with asthma (Vicendese et al., 2015VICENDESE, D., DHARMAGE, S.C., TANG, M.L., OLENKO, A., ALLEN, K.J., ABRAMSON, M.J. and ERBAS, B., 2015. Bedroom air quality and vacuuming frequency are associated with repeat child asthma hospital admissions. The Journal of Asthma, vol. 52, no. 7, pp. 727-731. PMid:25539399. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02770903.2014.1001904.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02770903.2014....

).

In the same way, cases of infections caused by these environmental fungi had been described in immunocompetent individuals in locals with presence of high quantity of fungal inoculums. For example, related mycoses such as: disseminated pediculosis (Ye et al., 2015YE, F., LUO, Q., ZHOU, Y., XIE, J., ZENG, Q., CHEN, G., SU, D. and CHEN, R., 2015. Disseminated penicilliosis marneffei in immunocompetent patients: a report of two cases. Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 161-165. PMid:25560026. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0255-0857.148433.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0255-0857.1484...

), mycotic endophthalmitis (Wu et al., 2011WU, J.S., CHEN, S.N., HWANG, J.F. and LIN, C.J., 2011. Endogenous mycotic endophthalmitis in an immunocompetent postpartum patient. Retinal Cases & Brief Reports, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 10-13. PMid:25389672. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ICB.0b013e3181bcf389.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ICB.0b013e3181...

), intracranial aspergilloma (Mohammadi et al., 2015MOHAMMADI, H., SADEGHI, S. and ZANDI, S., 2015. Central Nervous System Aspergilloma in an immunocompetent patient: a case Report. Iranian Journal of Public Health, vol. 44, no. 6, pp. 869-872. PMid:26258101.), cerebral aspergillosis (Bokhari et al., 2014BOKHARI, R., BAEESA, S., AL-MAGHRABI, J. and MADANI, T., 2014. Isolated cerebral aspergillosis in immunocompetent patients. World Neurosurgery, vol. 82, no. 1-2, pp. e325-e333. PMid:24076053. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2013.09.037.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2013.09...

), pulmonary scedosporium (Rahman et al., 2016RAHMAN, F.U., IRFAN, M., FASIH, N., JABEEN, K. and SHARIF, H., 2016. Pulmonary scedosporiosis mimicking aspergilloma in an immunocompetent host: a case report and review of the literature. Infection, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 127-132. PMid:26353885. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s15010-015-0840-4.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s15010-015-084...

), gastrointestinal aspergillosis (Koutsounas and Pyleris, 2015KOUTSOUNAS, I. and PYLERIS, E., 2015. Isolated enteric aspergillosis in a non severely immunocompromised patient. Case report and literature review. Arab Journal of Gastroenterology, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 72-75. PMid:26206431. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajg.2015.06.008.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajg.2015.06....

) between others diagnosis found in literature (Zahid and Farooqi, 2015ZAHID, M.F. and FAROOQI, J., 2015. Aspergillus fumigatus spinal abscess in an immunocompetent child. Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons--Pakistan, vol. 25, no. 7, pp. 555-556. PMid:26208570.; Borkar et al., 2008BORKAR, S.A., SHARMA, M.S., RAJPAL, G., JAIN, M., XESS, I. and SHARMA, B.S., 2008. Brain abscess caused by Cladophialophora bantiana in an immunocompetent host: need for a novel cost-effective antifungal agent. Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 271-274. PMid:18695333. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0255-0857.42050.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0255-0857.4205...

). This problem aggravates in immunocompromised patients, such is the case of hospitalized children with hypersensitivity related to the presence of the fungi inside the hospital (Beck et al., 2015BECK, A.F., HUANG, B., KERCSMAR, C.M., GUILBERT, T.W., MCLINDEN, D.J., LIERL, M.B. and KAHN, R.S., 2015. Allergen sensitization profiles in a population-based cohort of children hospitalized for asthma. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 376-384. PMid:25594255. http://dx.doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201408-376OC.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.2014...

; Libbrecht et al., 2015LIBBRECHT, C., GOUTAGNY, M.P., BACCHETTA, J., PLOTON, C., BIENVENU, A.L., BLEYZAC, N., MIALOU, V., BERTRAND, Y. and DOMENECH, C., 2015. Impact of a change in protected environment on the occurrence of severe bacterial and fungal infections in children undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. European Journal of Haematology, vol. 18, no. 10, pp. 70-77. PMid:26380877.; Guppy et al., 1998GUPPY, K.H., THOMAS, C., THOMAS, K. and ANDERSON, D., 1998. Cerebral fungal infections in the immunocompromised host: a literature review and a new pathogen – Chaetomium atrobrunneum: case report. Neurosurgery, vol. 43, no. 6, pp. 1463-1469. PMid:9848862.).

It is worth mentioning that, also fungi with low prevalence must be considered relevant. This is the case of the Zygomycetes fungi which occurred in this study in a low frequency (5.05%), responsible of the zygomycosis which is a rare infection, however invasive and with fast evolution, affecting immunosuppressed and eventually immunocompetent subjects (Souza et al., 2014SOUZA, J.M., SPROESSER JUNIOR, A.J., FELIPPU NETO, A., FUKS, F.B. and OLIVEIRA, C.A.C., 2014. Zigomicose rino facial: relato de caso. Einstein, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 347-350. PMid:25167339. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1679-45082014RC2579.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1679-45082014...

; Severo et al., 2010SEVERO, C.B., GUAZZELLI, L.S. and SEVERO, L.C., 2010. Chapter 7: zygomycosis. Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 134-141. PMid:20209316. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37132010000100018.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37132010...

; Prabhu and Patel, 2004PRABHU, R.M. and PATEL, R., 2004. Mucormycosis and entomophthoramycosis: a review of the clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, vol. 10, no. 7, suppl. 1, pp. 31-47. PMid:14748801. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-9465.2004.00843.x.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-9465.20...

).

Allergic reactions in humans may be by the inhalation of airborne fungi, this determines the intensity of clinical significance, being able to develop respiratory diseases, among other diseases (Mezzari et al., 2003MEZZARI, A., PERIN, C., SANTOS JÚNIOR, S.A., BERND, L.A.G. and GESU, G., 2003. Os fungos anemófilos e sensibilização em indivíduos atópicos em Porto Alegre, RS. Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira, vol. 49, no. 3, pp. 270-273. PMid:14666351. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-42302003000300030.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-42302003...

). Due to their invasive and opportunistic agents the presence of the genera Penicillium ssp. and Aspergillus ssp. in hospitals can cause high morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients, such as cancer patients in chemotherapy treatments, AIDS patients, patients with multiple trauma and among others are the most affected by opportunistic mycoses (Vesper et al., 2007VESPER, S.J., HAUGLAND, R.A., ROGERS, M.E. and NEELY, A.N., 2007. Opportunistic Aspergillus pathogens measured in home and hospital tap water by quantitative PCR (QPCR). Journal of Water and Health, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 427-431. PMid:17878557. http://dx.doi.org/10.2166/wh.2007.038.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2166/wh.2007.038...

; Moretti, 2007MORETTI, M.L., 2007. A importância crescente das infecções fúngicas. Revista Panamericana de Infectologia, vol. 9, pp. 8-9.; Pfaller, 1996PFALLER, M.A., 1996. Nosocomial candidiasis: emerging, species, reservoir and modes of transmission. Clinical Infectious Diseases, vol. 22, no. 2, suppl. 2, pp. 89-94. PMid:8722834. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/clinids/22.Supplement_2.S89.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/clinids/22.Sup...

).

Economic loss is another aspect to be considered in the nosocomial infections. According to the disclosed data by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2011WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION – WHO, 2011. Report on the burden of endemic health care-associated infection worldwide: clean careis safer care. Geneva: WHO.), only in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil, the expenses in the year 1992 with infections related to health care were of US$ 18 million. Public institutions are attributed to have the highest rates of nosocomial infections, providing an increase in the costs of treatment three times higher than the subjects with not acquire infection, with episodes that are concentrated in the ICUs due to the presence of subjects with a higher severity clinical case and by their time of permanence in the ICU area (Moura et al., 2007MOURA, M.E.B., CAMPELO, S.M.A., BRITO, F.C.P., BATISTA, O.M.A., ARAÚJO, T.M.E. and OLIVEIRA, A.D.S., 2007. Infecção hospitalar: estudo de prevalência em um hospital público de ensino. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, vol. 60, no. 4, pp. 416-421. PMid:18041525. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-71672007000400011.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-71672007...

; Prade, 1995PRADE, S.S., 1995. Estudo brasileiro da magnitude das infecões hospitalares em hospitais terciários. Revista de Controle de Infecção Hospitalar, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 11-24.).

Studies conducted by Shams-Ghahfarokhi et al. (2014)SHAMS-GHAHFAROKHI, M., AGHAEI-GHAREHBOLAGH, S., ASLANI, N. and RAZZAGHI-ABYANEH, M., 2014. Investigation on distribution of airborne fungi in outdoor environment in Tehran, Iran. Journal of Environmental Health Science and Engineering, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 54-61. PMid:24588901. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/2052-336X-12-54.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/2052-336X-12-5...

, Caggiano et al. (2014)CAGGIANO, G., NAPOLI, C., CORETTI, C., LOVERO, G., SCARAFILE, G., GIGLIO, O. and MONTAGNA, M.T., 2014. Mold contamination in a controlled hospital environment: a 3-year surveillance in southern Italy. BMC Infectious Diseases, no. 14, p. 595. PMid:25398412. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12879-014-0595-z.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12879-014-059...

and Chang et al. (2014)CHANG, C.C., ANANDA-RAJAH, M., BELCASTRO, A., MCMULLAN, B., REID, A., DEMPSEY, K., ATHAN, E., CHENG, A.C. and SLAVIN, M.A., 2014. Consensus guidelines for implementation of quality processes to prevent invasive fungal disease and enhanced surveillance measures during hospital building works, 2014. Internal Medicine Journal, vol. 44, no. 12, pp. 1389-1397. PMid:25482747. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/imj.12601.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/imj.12601...

confirmed that the environmental monitoring of airborne filamentous fungi is necessary to reduce fungal concentrations in operating theaters and in controlled environments, to prevent infections. According to Chang et al. (2014)CHANG, C.C., ANANDA-RAJAH, M., BELCASTRO, A., MCMULLAN, B., REID, A., DEMPSEY, K., ATHAN, E., CHENG, A.C. and SLAVIN, M.A., 2014. Consensus guidelines for implementation of quality processes to prevent invasive fungal disease and enhanced surveillance measures during hospital building works, 2014. Internal Medicine Journal, vol. 44, no. 12, pp. 1389-1397. PMid:25482747. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/imj.12601.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/imj.12601...

, in the tentative to reduce the environmental contamination by fungi, recommended that a standardized protocol for the sampling collection and culture is necessary in hospital institutions to verify the air quality.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the isolates in the ICU at the University Hospital from Pelotas were Penicillium spp., Aspergillus spp., Cladosporium spp., Fusarium spp., Paecelomyces spp., Curvularia spp., Alternaria spp., Zygomycetes and sterile mycelium. The presence of these pathogens emphasizes the importance of microbial control measures in the ICU.

Acknowledgements

Hospital Universitário of Pelotas, CNPq and the Universidade Federal de Pelotas.

-

(With 1 figure)

References

- AFSHARI, M.A., RIAZIPOUR, M., KACHUEI, R., TEIMOORI, M. and EINOLLAHI, B., 2013. A qualitative and quantitative study monitoring airborne fungal flora in the kidney transplant unit. Nephro-Urology Monthly, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 736-740. PMid:23841036. http://dx.doi.org/10.5812/numonthly.5379

» http://dx.doi.org/10.5812/numonthly.5379 - BECK, A.F., HUANG, B., KERCSMAR, C.M., GUILBERT, T.W., MCLINDEN, D.J., LIERL, M.B. and KAHN, R.S., 2015. Allergen sensitization profiles in a population-based cohort of children hospitalized for asthma. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 376-384. PMid:25594255. http://dx.doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201408-376OC

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201408-376OC - BERNARDI, E. and NASCIMENTO, J.S., 2005. Fungos anemófilos na praia do Laranjal, Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Arquivos do Instituto Biologico, vol. 72, no. 1, pp. 93-97.

- BÖHLKE, M., SOUZA, P.A., MENEZES, A.M.D., ROTH, J.M. and KRAMER, L.R., 2007. Peritonitis due to Penicillium and Enterobacter in a patient receiving continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 166-168. PMid:17625749. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-86702007000100035

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-86702007000100035 - BOKHARI, R., BAEESA, S., AL-MAGHRABI, J. and MADANI, T., 2014. Isolated cerebral aspergillosis in immunocompetent patients. World Neurosurgery, vol. 82, no. 1-2, pp. e325-e333. PMid:24076053. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2013.09.037

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2013.09.037 - BORKAR, S.A., SHARMA, M.S., RAJPAL, G., JAIN, M., XESS, I. and SHARMA, B.S., 2008. Brain abscess caused by Cladophialophora bantiana in an immunocompetent host: need for a novel cost-effective antifungal agent. Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 271-274. PMid:18695333. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0255-0857.42050

» http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0255-0857.42050 - CAGGIANO, G., NAPOLI, C., CORETTI, C., LOVERO, G., SCARAFILE, G., GIGLIO, O. and MONTAGNA, M.T., 2014. Mold contamination in a controlled hospital environment: a 3-year surveillance in southern Italy. BMC Infectious Diseases, no. 14, p. 595. PMid:25398412. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12879-014-0595-z

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12879-014-0595-z - CARMO, E.S., BELÉM, L.F., CATÃO, R.M., LIMA, E.O., SILVEIRA, I.L. and SOARES, L.H.M., 2007. Microbiota fúngica presente em diversos setores de um hospital público em Campina Grande – PB. Revista Brasileira de Análises Clínicas, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 213-216.

- CHANG, C.C., ANANDA-RAJAH, M., BELCASTRO, A., MCMULLAN, B., REID, A., DEMPSEY, K., ATHAN, E., CHENG, A.C. and SLAVIN, M.A., 2014. Consensus guidelines for implementation of quality processes to prevent invasive fungal disease and enhanced surveillance measures during hospital building works, 2014. Internal Medicine Journal, vol. 44, no. 12, pp. 1389-1397. PMid:25482747. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/imj.12601

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/imj.12601 - CHEN, B.Y., CHAO, H., WU, C.F., KIM, H., HONDA, Y. and GUO, Y.L., 2014. High ambient Cladosporium spores were associated with reduced lung function in schoolchildren in a longitudinal study. The Science of the Total Environment, vol. 485, pp. 370-376. PMid:24607630. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.01.078

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.01.078 - COLOMBO, A.L., 2000. Epidemiology and treatment of hematogenous candidiasis: a Brazilian perspective. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 113-118. PMid:10934493.

- DIONGUE, K., BADIANE, A.S., SECK, M.C., NDIAYE, M., DIALLO, M.A., DIALLO, S., SY, O., NDIAYE, J.L., FAYE, B., NDIR, O. and NDIAYE, D., 2015. Qualitative fungal composition of services at risk of nosocomial infections at Aristide Le Dantec Hospital (Dakar). Journal de Mycologie Médicale, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 39-43. PMid:25499807. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mycmed.2014.10.020.

- EL-SHARKAWY, M.F. and NOWEIR, M.E., 2014. Indoor air quality levels in a University Hospital in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. Journal of Family & Community Medicine, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 39-47. PMid:24696632. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/2230-8229.128778

» http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/2230-8229.128778 - FLORES, L.H. and ONOFRE, S.B., 2010. Determinação da presença de fungos anemófilos e leveduras em unidade de saúde da cidade de Francisco Beltrão – PR. Revista de Saúde e Biologia, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 22-26.

- FREITAS, A., PEDRAL-SAMPAIO, D.B., ESPINHEIRA NOGUEIRA, L., DALTRO, E., SAMPAIO, J., ATHANÁSIO, P., LACAZ, C. and BADARÓ, R., 1997. Cladophialophora bantiana (Previously Cladosporium trichoides): first report of a case in Brazil. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 1, no. 6, pp. 313-316. PMid:11105153.

- GOEL, A., SATOSKAR, A., DESAI, A.P. and PANDYA, S.K., 1992. Brain abscess caused by Cladosporium trichoides. British Journal of Neurosurgery, vol. 6, no. 6, pp. 591-593. PMid:1472326. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02688699209002378

» http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02688699209002378 - GUPPY, K.H., THOMAS, C., THOMAS, K. and ANDERSON, D., 1998. Cerebral fungal infections in the immunocompromised host: a literature review and a new pathogen – Chaetomium atrobrunneum: case report. Neurosurgery, vol. 43, no. 6, pp. 1463-1469. PMid:9848862.

- IWEN, P.C., DAVIS, J.C., REED, E.C., WINFIELD, B.A. and HINRICHS, S.H., 1994. Airborne fungal spore monitoring in a protective environment during hospital construction, and correlation with an outbreak of invasive aspergillosis. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, vol. 15, no. 5, pp. 303-306. PMid:8077640. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/30146558

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/30146558 - KOUTSOUNAS, I. and PYLERIS, E., 2015. Isolated enteric aspergillosis in a non severely immunocompromised patient. Case report and literature review. Arab Journal of Gastroenterology, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 72-75. PMid:26206431. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajg.2015.06.008

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajg.2015.06.008 - LACAZ, C.S., PORTO, E., MARTINS, J.E.C., VACCARI, E.M.H. and MELO, N.T., 2002. Tratado de micologia médica 9th ed. São Paulo: Sarvier. 1104 p.

- LIBBRECHT, C., GOUTAGNY, M.P., BACCHETTA, J., PLOTON, C., BIENVENU, A.L., BLEYZAC, N., MIALOU, V., BERTRAND, Y. and DOMENECH, C., 2015. Impact of a change in protected environment on the occurrence of severe bacterial and fungal infections in children undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. European Journal of Haematology, vol. 18, no. 10, pp. 70-77. PMid:26380877.

- LOBATO, R.C., VARGAS, V.S. and SILVEIRA, E.S., 2009. Sazonalidade e prevalência de fungos anemófilos em ambiente hospitalar no sul do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Revista da Faculdade de Ciências Médicas de Sorocaba, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 21-28.

- LUGAUSKAS, A. and KRIKŠTAPONIS, A., 2004. Filamentous fungi isolated in hospitals and some medical institutions in Lithuania. Indoor and Built Environment, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 101-108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1420326X04040936

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1420326X04040936 - MARTINS-DINIZ, J.N., SILVA, R.A.M., MIRANDA, E.T. and MENDES-GIANNINI, M.J.S., 2005. Monitoramento de fungos anemófilos e de leveduras em unidade hospitalar. Revista de Saude Publica, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 398-405. PMid:15997315. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-89102005000300010.

- MELO, L.L.S., LIMA, A.M.C., DAMASCENO, C.A.V. and VIEIRA, A.L.P., 2009. Flora fúngica no ambiente da Unidade de Terapia Intensiva Pediátrica e Neonatal em hospital terciário. Revista Paulista de Pediatria, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 303-308. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-05822009000300011

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-05822009000300011 - MEZZARI, A., PERIN, C., SANTOS JÚNIOR, S.A., BERND, L.A.G. and GESU, G., 2003. Os fungos anemófilos e sensibilização em indivíduos atópicos em Porto Alegre, RS. Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira, vol. 49, no. 3, pp. 270-273. PMid:14666351. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-42302003000300030

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-42302003000300030 - MOHAMMADI, H., SADEGHI, S. and ZANDI, S., 2015. Central Nervous System Aspergilloma in an immunocompetent patient: a case Report. Iranian Journal of Public Health, vol. 44, no. 6, pp. 869-872. PMid:26258101.

- MORETTI, M.L., 2007. A importância crescente das infecções fúngicas. Revista Panamericana de Infectologia, vol. 9, pp. 8-9.

- MOURA, M.E.B., CAMPELO, S.M.A., BRITO, F.C.P., BATISTA, O.M.A., ARAÚJO, T.M.E. and OLIVEIRA, A.D.S., 2007. Infecção hospitalar: estudo de prevalência em um hospital público de ensino. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, vol. 60, no. 4, pp. 416-421. PMid:18041525. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-71672007000400011

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-71672007000400011 - NORITOMI, D.T., BUB, G.L., BEER, I., SILVA, A.S.F., CLEVA, R. and GAMA-RODRIGUES, J.J., 2005. Multiple brain abscesses due to Penicillium spp. infection. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de Sao Paulo, vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 167-170. PMid:16021292. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0036-46652005000300010

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0036-46652005000300010 - OSHIKATA, C., TSURIKISAWA, N., SAITO, A., WATANABE, M., KAMATA, Y., TANAKA, M., TSUBURAI, T., MITOMI, H., TAKATORI, K., YASUEDA, H. and AKIYAMA, K., 2013. Fatal pneumonia caused by Penicillium digitatum: a case report. BMC Pulmonary Medicine, vol. 13, no. 2013, pp. 13-16. PMid:23522080. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2466-13-16

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2466-13-16 - PANAGOPOULOU, P., FILIOTI, J., PETRIKKOS, G., GIAKOUPPI, P., ANATOLIOTAKI, M., FARMAKI, E., KANTA, A., APOSTOLAKOU, H., AVLAMI, A., SAMONIS, G. and ROILIDES, E., 2002. Environmental surveillance of filamentous fungi in three tertiary care hospitals in Greece. The Journal of Hospital Infection, vol. 52, no. 3, pp. 185-191. PMid:12419271. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/jhin.2002.1298

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/jhin.2002.1298 - PECKHAM, D., WILLIAMS, K., WYNNE, S., DENTON, M., POLLARD, K. and BARTON, R., 2016. Fungal contamination of nebuliser devices used by people with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 74-77. PMid:26104996. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcf.2015.06.004

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcf.2015.06.004 - PFALLER, M.A., 1996. Nosocomial candidiasis: emerging, species, reservoir and modes of transmission. Clinical Infectious Diseases, vol. 22, no. 2, suppl. 2, pp. 89-94. PMid:8722834. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/clinids/22.Supplement_2.S89

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/clinids/22.Supplement_2.S89 - PRABHU, R.M. and PATEL, R., 2004. Mucormycosis and entomophthoramycosis: a review of the clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, vol. 10, no. 7, suppl. 1, pp. 31-47. PMid:14748801. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-9465.2004.00843.x

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-9465.2004.00843.x - PRADE, S.S., 1995. Estudo brasileiro da magnitude das infecões hospitalares em hospitais terciários. Revista de Controle de Infecção Hospitalar, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 11-24.

- RAHMAN, F.U., IRFAN, M., FASIH, N., JABEEN, K. and SHARIF, H., 2016. Pulmonary scedosporiosis mimicking aspergilloma in an immunocompetent host: a case report and review of the literature. Infection, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 127-132. PMid:26353885. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s15010-015-0840-4

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s15010-015-0840-4 - REVANKAR, S.G., 2007. Dematiaceous fungi. Mycoses, vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 91-101. PMid:17305771. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0507.2006.01331.x

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0507.2006.01331.x - SAUTOUR, M., SIXT, N., DALLE, F., L’OLLIVIER, C., CALINON, C., FOURQUENET, V., THIBAUT, C., JURY, H., LAFON, I., AHO, S., COUILLAULT, G., VAGNER, O., CUISENIER, B., BESANCENOT, J.P., CAILLOT, D. and BONNIN, A., 2007. Prospective survey of indoor fungal contamination in hospital during a period of building construction. The Journal of Hospital Infection, vol. 67, no. 4, pp. 367-373. PMid:18037534. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2007.09.013

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2007.09.013 - SEVERO, C.B., GUAZZELLI, L.S. and SEVERO, L.C., 2010. Chapter 7: zygomycosis. Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 134-141. PMid:20209316. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37132010000100018

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37132010000100018 - SHAMS-GHAHFAROKHI, M., AGHAEI-GHAREHBOLAGH, S., ASLANI, N. and RAZZAGHI-ABYANEH, M., 2014. Investigation on distribution of airborne fungi in outdoor environment in Tehran, Iran. Journal of Environmental Health Science and Engineering, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 54-61. PMid:24588901. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/2052-336X-12-54

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/2052-336X-12-54 - SIDRIM, J.J.C. and ROCHA, M.F.G., 2004. Micologia médica à luz de autores contemporâneos Rio de Janeiro: Guanaba Koogan. 396 p.

- SOUZA JÚNIOR, U.P. and VIEIRA, K.V.M., 2010. Microbiota fúngica anemófila de hospitais da rede pública da cidade de Campina Grande, PB. Revista de Biologia e Farmácia, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 102-116.

- SOUZA, E.S., BELEI, R.A., CARRILHO, C.M.D.M., MATSUO, T., YAMADA-OGATTA, S.F., ANDRADE, G., PERUGINI, M.R.E., PIERI, F.M., DESSUNTI, E.M. and KERBAUY, G., 2015. Mortality and risks related to healthcare-associated infection. Text Context Nursing, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 220-228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0104-07072015002940013

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0104-07072015002940013 - SOUZA, J.M., SPROESSER JUNIOR, A.J., FELIPPU NETO, A., FUKS, F.B. and OLIVEIRA, C.A.C., 2014. Zigomicose rino facial: relato de caso. Einstein, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 347-350. PMid:25167339. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1679-45082014RC2579

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1679-45082014RC2579 - VESPER, S.J., HAUGLAND, R.A., ROGERS, M.E. and NEELY, A.N., 2007. Opportunistic Aspergillus pathogens measured in home and hospital tap water by quantitative PCR (QPCR). Journal of Water and Health, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 427-431. PMid:17878557. http://dx.doi.org/10.2166/wh.2007.038

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2166/wh.2007.038 - VICENDESE, D., DHARMAGE, S.C., TANG, M.L., OLENKO, A., ALLEN, K.J., ABRAMSON, M.J. and ERBAS, B., 2015. Bedroom air quality and vacuuming frequency are associated with repeat child asthma hospital admissions. The Journal of Asthma, vol. 52, no. 7, pp. 727-731. PMid:25539399. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02770903.2014.1001904

» http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02770903.2014.1001904 - WANKE, B., LAZÉRA, M.S. and NUCCI, M., 2000. Fungal infections in the immunocompromised host. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, vol. 95, no. 1, suppl. 1, pp. 153-158. PMid:11142705. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02762000000700025

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02762000000700025 - WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION – WHO, 2011. Report on the burden of endemic health care-associated infection worldwide: clean careis safer care Geneva: WHO.

- WU, J.S., CHEN, S.N., HWANG, J.F. and LIN, C.J., 2011. Endogenous mycotic endophthalmitis in an immunocompetent postpartum patient. Retinal Cases & Brief Reports, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 10-13. PMid:25389672. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ICB.0b013e3181bcf389

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ICB.0b013e3181bcf389 - YE, F., LUO, Q., ZHOU, Y., XIE, J., ZENG, Q., CHEN, G., SU, D. and CHEN, R., 2015. Disseminated penicilliosis marneffei in immunocompetent patients: a report of two cases. Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 161-165. PMid:25560026. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0255-0857.148433

» http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0255-0857.148433 - ZAHID, M.F. and FAROOQI, J., 2015. Aspergillus fumigatus spinal abscess in an immunocompetent child. Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons--Pakistan, vol. 25, no. 7, pp. 555-556. PMid:26208570.

- ZHANG, H.L., FENG, H.H., FANG, Z.L., WANG, B.D. and LI, D., 2015. Airborne fungal aerosol concentration and distribution characteristics in air- conditioned wards. Huan Jing Ke Xue, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 1234-1240. PMid:26164895.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

27 July 2017 -

Date of issue

May-Aug 2018

History

-

Received

26 Apr 2016 -

Accepted

08 Nov 2016