Abstract

The gastrointestinal microflora regulates the body’s functions and plays an important role in its health. Dysbiosis leads to a number of chronic diseases such as diabetes, obesity, inflammation, atherosclerosis, etc. However, these diseases can be prevented by using probiotics – living microorganisms that benefit the microflora and, therefore, improve the host organism's health. The most common probiotics include lactic acid bacteria of the Bifidobacterium and Propionibacterium genera. We studied the probiotic properties of the following strains: Bifidobacterium adolescentis АС-1909, Bifidobacterium longum infantis АС-1912, Propionibacterium jensenii В-6085, Propionibacterium freudenreichii В-11921, Propionibacterium thoenii В-6082, and Propionibacterium acidipropionici В-5723. Antimicrobial activity was determined by the ‘agar blocks’ method against the following test cultures: Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Salmonella enterica ATCC 14028, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923, Pseudomonas aeruginosa B6643, Proteus vulgaris ATCC 63, and Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 7644. Moderate antimicrobial activity against all the test cultures was registered in Bifidobacterium adolescentis АС-1909, Propionibacterium jensenii В-6085, and Propionibacterium thoenii В-6082. Antioxidant activity was determined by the DPPH inhibition method in all the lactic acid strains. Our study indicated that some Propionibacterium and Bifidobacterium strains or, theoretically, their consortia could be used as probiotic cultures in dietary supplements or functional foods to prevent a number of chronic diseases.

Keywords:

lactic acid bacteria; bifidobacteria; propionic acid bacteria; biocompatibility

Resumo

A microbiota gastrointestinal regula as funções do corpo e desempenha um papel importante na sua saúde. A disbiose leva a uma série de doenças crônicas, como diabetes, obesidade, inflamação, aterosclerose, etc. No entanto, essas doenças podem ser prevenidas pelo uso de probióticos − microrganismos vivos que beneficiam a microflora e, portanto, melhoram a saúde do organismo hospedeiro. Os probióticos mais comuns incluem bactérias do ácido láctico dos gêneros Bifidobacterium e Propionibacterium. Nós estudamos as propriedades probióticas das seguintes cepas: Bifidobacterium adolescentis АС-1909, Bifidobacterium longum infantis АС-1912, Propionibacterium jensenii В-6085, Propionibacterium freudenreichii В-11921, Propionibacterium thoenii В-6082 В-6082 acid e Propionibacterium thoenii В-6082 В-6082 acidibion. A atividade antimicrobiana foi determinada pelo método de 'blocos de ágar' contra as seguintes culturas de teste: Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Salmonella enterica ATCC 14028, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923, Pseudomonas aeruginosa B6643, Proteus vulgaris ATCC 63 e Listeria monocytogenes moderada atividade ATCC 7644. Uma atividade antimicrobiana moderada contra todas as culturas de teste foi registrado em Bifidobacterium adolescentis АС-1909, Propionibacterium jensenii В-6085 e Propionibacterium thoenii В-6082. A atividade antioxidante foi determinada pelo método de inibição do DPPH em todas as cepas de ácido lático. Nosso estudo indicou que algumas cepas de Propionibacterium e Bifidobacterium − ou, teoricamente, seus consórcios − poderiam ser usadas como culturas probióticas em suplementos dietéticos ou alimentos funcionais para prevenir uma série de doenças crônicas.

Palavras-chave:

bactérias do ácido láctico; bifidobactérias; bactérias do ácido propiônico; biocompatibilidade

1. Introduction

The gastrointestinal microbiota is a collection of non-pathogenic microorganisms that inhabit the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and regulate the host organism's metabolic, protective, coordinating, and epigenetic functions (Celi et al., 2017CELI, P., COWIESON, A.J., FRU-NJI, F., STEINERT, R.E., KLUENTER, A. and VERLHAC, V., 2017. Gastrointestinal functionality in animal nutrition and health: new opportunities for sustainable animal production. Animal Feed Science and Technology, vol. 234, pp. 88-100. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2017.09.012.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2...

, 2019CELI, P., VERLHAC, V., CALVO, E.P., SCHMEISSER, J. and KLUENTER, A., 2019. Biomarkers of gastrointestinal functionality in animal nutrition and health. Animal Feed Science and Technology, vol. 250, pp. 9-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2018.07.012.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2...

; Sherwin et al., 2018SHERWIN, E., DINAN, T.G. and CRYAN, J.F., 2018. Recent developments in understanding the role of the gut microbiota in brain health and disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 1420, no. 1, pp. 5-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13416. PMid:28768369.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13416...

; Valdes et al., 2018VALDES, A.M., WALTER, J., SEGAL, E. and SPECTOR, T.D., 2018. Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), vol. 361, pp. k2179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2179. PMid:29899036.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2179...

). Its disrupted functioning can become one of the main causes of chronic metabolism-related diseases (obesity, diabetes, cardio-vascular disease, etc.). Dysbiosis can be caused by certain medications, infectious diseases, lifestyle, surgery, unhealthy diet, and other factors (Morita et al., 2015MORITA, C., TSUJI, H., HATA, T., GONDO, M., TAKAKURA, S., KAWAI, K., YOSHIHARA, K., OGATA, K., NOMOTO, K., MIYAZAKI, K. and SUDO, N., 2015. Gut dysbiosis in patients with anorexia nervosa. PLoS One, vol. 10, no. 12, pp. e0145274. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145274. PMid:26682545.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0...

; Le Bastard et al., 2018LE BASTARD, Q., AL-GHALITH, G.A., GRÉGOIRE, M., CHAPELET, G., JAVAUDIN, F., DAILLY, E., BATARD, E., KNIGHTS, D. and MONTASSIER, E., 2018. Systematic review: human gut dysbiosis induced by non-antibiotic prescription medications. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 332-345. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/apt.14451. PMid:29205415.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/apt.14451...

). Probiotics are living microorganisms that positively affect the gastrointestinal microbiota, and therefore on health in general when taken systematically. Figure 1 shows the role of probiotics in preventing a number of chronic diseases.

Four main mechanisms achieve the positive effect of probiotics. Firstly, they are antagonistic to pathogenic and opportunistic strains due to the production of antimicrobial substances. Secondly, they are adhesive to epithelial cells, thereby creating competition for pathogenic strains. Thirdly, they act as immunomodulators for the host organism, and, finally, they reduce the number of metabolites produced by pathogenic microorganisms and/or cancer cells (Cremonini et al., 2002CREMONINI, F., DI CARO, S., NISTA, E.C., BARTOLOZZI, F., CAPELLI, G., GASBARRINI, G. and GASBARRINI, A., 2002. Meta-analysis: the effect of probiotic administration on antibiotic-associated diarrhoea. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, vol. 16, no. 8, pp. 1461-1467. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01318.x. PMid:12182746.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2036.20...

).

Among probiotic cultures, bacteria of the genus Bifidobacterium are especially important as normal representatives of the gastrointestinal microbiota (Cao et al., 2020CAO, L., CHEN, H., WANG, Q., LI, B., HU, Y., ZHAO, C., HU, Y. and YIN, Y., 2020. Literature-based phenotype survey and in silico genotype investigation of antibiotic resistance in the genus Bifidobacterium. Current Microbiology, vol. 77, no. 12, pp. 4104-4113. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00284-020-02230-w. PMid:33057753.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00284-020-022...

). Bifidobacteria are gram-positive anaerobes that benefit the microbiota by exhibiting anticarcinogenic effects, lowering cholesterol levels, improving lactose hydrolysis, producing vitamins, etc. (Abdelazez et al., 2017ABDELAZEZ, A., MUHAMMAD, Z., ZHANG, Q.-X., ZHU, Z., ABDELMOTAAL, H., SAMI, R. and MENG, X., 2017. Production of a functional frozen yogurt fortified with bifidobacterium spp. BioMed Research International, vol. 2017, pp. 6438528. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2017/6438528. PMid:28691028.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2017/6438528...

). Their growth in the large intestine can be activated by introducing large amounts of probiotics, which contain these bacteria, in the form of dietary supplements or functional fermented milk products. Alternatively, their activity can be stimulated by special food substances called prebiotics (Trindade et al., 2003TRINDADE, M.I., ABRATT, V.R. and REID, S.J., 2003. Induction of sucrose utilization genes from Bifidobacterium lactis by sucrose and raffinose. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, vol. 69, no. 1, pp. 24-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.69.1.24-32.2003. PMid:12513973.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.69.1.24-32...

). These substances include bifidogenic compounds, for example, 1,4-dihydroxy-2-naphthoic acid, a metabolic product of bacteria of the genus Propionibacterium.

Nowadays, scientists are increasingly considering dairy propionibacteria as probiotics. These are gram-positive anaerobic bacteria that do not form spores and are tolerant to low oxygen. These bacteria can convert carbohydrates into acetic and propionic acids and metabolize vitamins (B9, B12), bacteriocins (propionicin (Altieri, 2016ALTIERI, C., 2016. Dairy propionibacteria as probiotics: recent evidences. World Journal of Microbiology & Biotechnology, vol. 32, no. 10, pp. 172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11274-016-2118-0. PMid:27565782.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11274-016-211...

) and teniicin (Li et al., 2020LI, J., GE, Y., ZADEH, M., CURTISS III, R. and MOHAMADZADEH, M., 2020. Regulating vitamin B12 biosynthesis via the cbiMCbl riboswitch in Propionibacterium strain UF1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 117, no. 1, pp. 602-609. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1916576116. PMid:31836694.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.191657611...

)), bifidogenic compounds that stimulate bifidobacterial growth (1,4-dihydroxy-2-naphthoic acid), substances with immunomodulatory and anticarcinogenic properties (Huang et al., 2003HUANG, Y., KOTULA, L. and ADAMS, M.C., 2003. The in vivo assessment of safety and gastrointestinal survival of an orally administered novel probiotic, Propionibacterium jensenii 702, in a male Wistar rat model. Food and Chemical Toxicology, vol. 41, no. 12, pp. 1781-1787. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0278-6915(03)00215-1. PMid:14563403.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0278-6915(03)...

; Meile et al., 2008MEILE, L., LE BLAY, G. and THIERRY, A., 2008. Safety assessment of dairy microorganisms: propionibacterium and Bifidobacterium. International Journal of Food Microbiology, vol. 126, no. 3, pp. 316-320. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.08.019. PMid:17889391.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro....

; Zárate and Chaia, 2012ZÁRATE, G. and CHAIA, A.P., 2012. Influence of lactose and lactate on growth and β-galactosidase activity of potential probiotic Propionibacterium acidipropionici. Anaerobe, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 25-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.12.005. PMid:22202442.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.201...

; Gaucher et al., 2020GAUCHER, F., RABAH, H., KPONOUGLO, K., BONNASSIE, S., POTTIER, S., DOLIVET, A., MARCHAND, P., JEANTET, R., BLANC, P. and JAN, G., 2020. Intracellular osmoprotectant concentrations determine Propionibacterium freudenreichii survival during drying. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, vol. 104, no. 7, pp. 3145-3156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00253-020-10425-1. PMid:32076782.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00253-020-104...

), and enzymes (β-galactosidase) (Zárate and Chaia, 2012ZÁRATE, G. and CHAIA, A.P., 2012. Influence of lactose and lactate on growth and β-galactosidase activity of potential probiotic Propionibacterium acidipropionici. Anaerobe, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 25-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.12.005. PMid:22202442.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.201...

; Altieri, 2016ALTIERI, C., 2016. Dairy propionibacteria as probiotics: recent evidences. World Journal of Microbiology & Biotechnology, vol. 32, no. 10, pp. 172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11274-016-2118-0. PMid:27565782.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11274-016-211...

). Propionibacteria are of two species, the first inhabiting the skin and the second (a ‘dairy’ species) found in raw milk and fermented milk products (Argañaraz-Martínez et al., 2013ARGAÑARAZ-MARTÍNEZ, E., BABOT, J.D., APELLA, M.C. and CHAIA, A.P., 2013. Physiological and functional characteristics of Propionibacterium strains of the poultry microbiota and relevance for the development of probiotic products. Anaerobe, vol. 23, pp. 27-37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2013.08.001. PMid:23973927.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.201...

). For this study, the ‘dairy’ propionic bacteria are of utmost interest.

Today's highly relevant is the creation of probiotic consortia consisting of propionibacteria and bifidobacteria to be used in dietary supplements or functional products to prevent chronic disease. In order for strains to be classified as probiotics, they must meet the criteria of:

-

1

safety (non-pathogenic and genetically stable strains come from a healthy source of human or animal origin and do not produce toxic metabolites);

-

2

functionality (strains are highly adhesive, antagonistic against pathogenic and opportunistic microorganisms, resistant to antibiotics and gastrointestinal conditions); and

-

3

technological usefulness (strains maintain their viability and properties during storage, are easy to cultivate and grow) (Markowiak and Śliżewska, 2017MARKOWIAK, P. and ŚLIŻEWSKA, K., 2017. Effects of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics on human health. Nutrients, vol. 9, no. 9, pp. 1021. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/nu9091021. PMid:28914794.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/nu9091021... ; Kumari et al., 2020KUMARI, R., SINGH, A., YADAV, A.N., MISHRA, S., SACHAN, A. and SACHAN, S.G., 2020. Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics: current status and future uses for human health. In: A. Rodrigues, ed. New and future developments in microbial biotechnology and bioengineering. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 173-190.; Markowiak-Kopeć and Śliżewska, 2020MARKOWIAK-KOPEĆ, P. and ŚLIŻEWSKA, K., 2020. The effect of probiotics on the production of short-chain fatty acids by human intestinal microbiome. Nutrients, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 1107. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/nu12041107. PMid:32316181.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/nu12041107... ).

Our study aimed to determine the compliance of bifidobacteria (Bifidobacterium adolescentis АС-1909, Bifidobacterium longum infantis АС-1912) and propionibacteria (Propionibacterium jensenii В-6085, Propionibacterium freudenreichii В-11921, Propionibacterium thoenii В-6082, Propionibacterium acidipropionici В-5723) with the criteria of probiotic cultures so that they could be used to normalize the gastrointestinal microflora and prevent a number of chronic diseases. For this, we analyzed the bacteria for the presence of antibacterial and antioxidant properties, as well as resistance to various antibiotics and negative conditions of the gastrointestinal tract.

2. Material and Methods

Our study was conducted in the Laboratory for Bio testing Natural Nutraceuticals at Kemerovo State University (Russia).

We used the following collection strains of lactic acid bacteria (Pieniz et al., 2015PIENIZ, S., ANDREAZZA, R., OKEKE, B.C., CAMARGO, F.A. and BRANDELLI, A., 2015. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Enterococcus species isolated from meat and dairy products. Brazilian Journal of Biology = Revista Brasileira de Biologia, vol. 75, no. 4, pp. 923-931. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.02814. PMid:26675908.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.0281...

; Can-Herrera et al., 2021CAN-HERRERA, L.A., GUTIERREZ-CANUL, C.D., DZUL-CERVANTES, M.A.A., PACHECO-SALAZAR, O.F., CHI-CORTEZ, J.D. and CARBONELL, L.S., 2021. Identification by molecular techniques of halophilic bacteria producing important enzymes from pristine area in Campeche, Mexico. Brazilian Journal of Biology = Revista Brasileira de Biologia, vol. 83, pp. e246038. PMid:34495150.): Bifidobacterium adolescentis АС-1909, Bifidobacterium longum infantis АС-1912, Propionibacterium jensenii В-6085, Propionibacterium freudenreichii В-11921, Propionibacterium thoenii В-6082, and Propionibacterium acidipropionici В-5723 (Research Institute of Genetics and Selection of Industrial Microorganisms, Kurchatov Institute, Russia). Their cultivation conditions are shown in Table 1.

-

1

The antimicrobial properties of lactic acid cultures were studied in relation to the following test cultures: Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Salmonella enterica ATCC 14028, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923, Pseudomonas aeruginosa B6643, Proteus vulgaris ATCC 63, and Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 7644 (Research Institute of Genetics and Selection of Industrial Microorganisms, Kurchatov Institute, Russia). The antagonistic properties were determined by the ‘agar blocks’ method. First, we grew a bacterial lawn on the nutrient media (Table 1). Then, an 8 mm agar block was cut out and transferred onto a Petri dish with a meat infusion agar (State Research Centre for Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, Russia) previously seeded with a test culture. The dishes were placed in a thermostat for a day at 37 °C (optimum temperature for test cultures). Zones of growth inhibition indicated the presence of antagonistic activity: high (zones of over 23 mm in diameter), medium (17–22 mm), weak (11–16 mm), or zero activity (less than 11 mm) (Kumar et al., 2012KUMAR, P., DUBEY, R.C. and MAHESHWARI, D.K., 2012. Bacillus strains isolated from rhizosphere showed plant growth promoting and antagonistic activity against phytopathogens. Microbiological Research, vol. 167, no. 8, pp. 493-499. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2012.05.002. PMid:22677517.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2012.... ; Jomehzadeh et al., 2020JOMEHZADEH, N., JAVAHERIZADEH, H., AMIN, M., SAKI, M., AL-OUQAILI, M.T., HAMIDI, H., SEYEDMAHMOUDI, M. and GORJIAN, Z., 2020. Isolation and identification of potential probiotic Lactobacillus species from feces of infants in southwest Iran. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 96, pp. 524-530. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.034. PMid:32439543.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05... ). -

2

The antioxidant activity of lactic acid cultures was spectrophotometrically determined by the DPPH method (Pyrzynska and Pękal, 2013PYRZYNSKA, K. and PĘKAL, A., 2013. Application of free radical diphenylpicrylhydrazyl (DPPH) to estimate the antioxidant capacity of food samples. Analytical Methods, vol. 5, no. 17, pp. 4288-4295. http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/c3ay40367j.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/c3ay40367j... ). The technique used in this study was developed by Knysh and Nikitchenko (2020)KNYSH, O.V. and NIKITCHENKO, Y.V., 2020. In vitro anti-radical activity of bifidobacterium bifidum and lactobacillus reuteri cell-free extracts. Актуальні проблеми сучасної медицини: Вісник Української медичної стоматологічної академії, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 140-144.. First, a working solution was prepared by mixing a standard DPPH solution (5 × 10-4 M) with ethanol acidified with acetic acid in a ratio of 1:10. Then, 1 ml of the test sample (supernatant obtained at different phases of strain growth, 8–28 h) was added to 1 ml of the working solution and thoroughly mixed. The resulting mixture was left in the dark for 30 min. The kinetics of decreasing optical density was recorded at 517 nm using a Glomax Multi reader (Promega, USA). The DPPH working solution was used as a control sample. -

3

The disk diffusion method determined the antibiotic resistance of lactic acid cultures, as described by Yang et al. (2020)Yang, Y., Babich, O.O., Stanislav, S., SUKIHIKH, S.A. and MILENTYEVA, I.S., 2020. Antibiotic activity and resistance of lactic acid bacteria and other antagonistic bacteriocin-producing microorganisms. Foods and Raw materials, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 377-384. and Zimina et al. (2020)ZIMINA, M., BABICH, O., PROSEKOV, A., SUKHIKH, S., IVANOVA, S., SHEVCHENKO, M. and NOSKOVA, S., 2020. Overview of global trends in classification, methods of preparation and application of bacteriocins. Antibiotics, vol. 9, no. 9, pp. 553. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics9090553. PMid:32872235.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics909... . For this, microorganisms (0.5 McFarland measured by a DEN-1 densimeter (BioSan, Latvia)) were grown on MRS agar (State Research Centre for Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, Russia) by the surface method for 24 h at an optimal growth temperature. After inoculation, indicator discs were laid out on the medium's surface to determine antibiotics sensitivity (Bio-Rad, USA). The incubation period was 24 h at 37ºC. We used discs with ampicillin (10 μg), benzylpenicillin (5 units), carbenicillin (100 μg), polymyxin (100 units), streptomycin (10 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), clotrimazole (10 μg), chloramphenicol (30 μg), tetracycline (30 μg), neomycin (30 μg), and kanamycin (30 μg) (HiMedia Laboratories, India; Agat-Med, Russia). The degree of antibiotic resistance was determined by measuring the zone of inhibition around the indicator disc (mm). The strains were considered resistant, moderately resistant, and sensitive to antibiotics with inhibition zones of under 15 mm, 16–20 mm, and over 21 mm in diameter, respectively (Hashemi et al., 2014HASHEMI, S.M.B., SHAHIDI, F., MORTAZAVI, S.A., MILANI, E. and ESHAGHI, Z., 2014. Potentially probiotic Lactobacillus strains from traditional Kurdish cheese. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 22-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12602-014-9155-5. PMid:24676764.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12602-014-915... ). -

4

The resistance of lactic acid bacteria to unfavorable gastrointestinal conditions was measured by the method described by Kitaevskaya (2012)KITAEVSKAYA, S.V., 2012. Current trends in the selection and identification of probiotic strains of lactic acid bacteria. Bulletin of Kazan Technological University, vol. 15, no. 17, pp. 184-188.. The resistance to bile, phenol, NaCl, and acidity was determined by incubating strains in MRS broth containing 0.3% ox bile (HiMedia Laboratories, India), 0.4% phenol, 6.5% salt, and in MRS broth acidified to pH=2.5 with hydrochloric acid, respectively, at 37ºC for 24 h. The resistance was determined by changes in the concentration of colony-forming units (CFU/ml), i.e., by plating serial tenfold dilutions on Petri dishes with MRS agar (Afonyushkin et al., 2017AFONYUSHKIN, V.N., KECHIN, A.A., TROMENSHLEGER, I.N., FILIPENKO, M.L. and SMETANINA, M.A., 2017. Determination of cell concentrations in stationary growing Lactobacillus salivarius cultures in relation to formation of biofilms and cell aggregates. Microbiology, vol. 86, no. 6, pp. 793-798. http://dx.doi.org/10.1134/S0026261717060030.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1134/S0026261717060... ). Samples were taken every 4 hours during 12 hours of cultivation. -

5

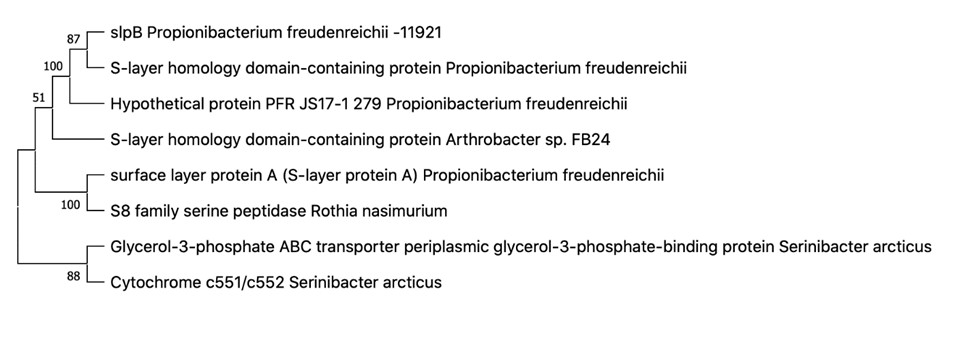

The DNA of selected lactic acid strains was analyzed for the presence of gene groups responsible for a number of probiotic properties. Using the NCBI database, genes that were potentially associated with probiotic activity were selected based on literature and bioinformatic analysis of the genomes of the strains closest to those under study. In particular, we selected the following genes:

-

For propionibacteria: PcfD, which affects the strain’s resistance to antibiotics (Moodley et al., 2015MOODLEY, C., REID, S.J. and ABRATT, V.R., 2015. Molecular characterisation of ABC-type multidrug efflux systems in Bifidobacterium longum. Anaerobe, vol. 32, pp. 63-69. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.12.004. PMid:25529295.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.201... ), and slpB, which is involved in adhesion to epithelial cells (Le Maréchal et al., 2015LE MARÉCHAL, C., PETON, V., PLÉ, C., VROLAND, C., JARDIN, J., BRIARD-BION, V., DURANT, G., CHUAT, V., LOUX, V., FOLIGNÉ, B., DEUTSCH, S.M., FALENTIN, H. and JAN, G., 2015. Surface proteins of Propionibacterium freudenreichii are involved in its anti-inflammatory properties. Journal of Proteomics, vol. 113, pp. 447-461. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2014.07.018. PMid:25150945.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2014.0... ; Carmo et al., 2018CARMO, F.L., SILVA, W.M., TAVARES, G.C., IBRAIM, I.C., CORDEIRO, B.F., OLIVEIRA, E.R., RABAH, H., CAUTY, C., SILVA, S.H., CANÁRIO VIANA, M.V., CAETANO, A.C.B., SANTOS, R.G., CARVALHO, R.D.O., JARDIN, J., PEREIRA, F.L., FOLADOR, E.L., LE LOIR, Y., FIGUEIREDO, H.C.P., JAN, G. and AZEVEDO, V., 2018. Mutation of the surface layer protein SlpB has pleiotropic effects in the probiotic Propionibacterium freudenreichii CIRM-BIA 129. Frontiers in Microbiology, vol. 9, pp. 1807. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.01807. PMid:30174657.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.018... ); -

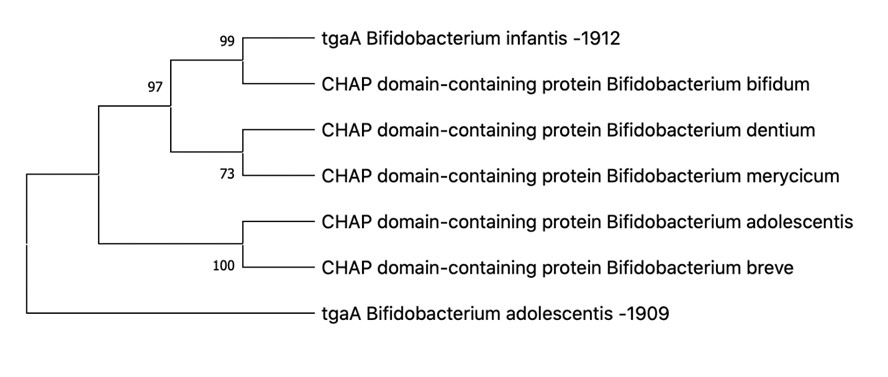

For bifidobacteria: DnaK, which is involved in the adaptive response to negative environmental conditions, e.g., to osmotic and thermal shock (Ventura et al., 2005VENTURA, M., ZINK, R., FITZGERALD, G.F. and VAN SINDEREN, D., 2005. Gene structure and transcriptional organization of the dnaK operon of Bifidobacterium breve UCC 2003 and application of the operon in bifidobacterial tracing. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, vol. 71, no. 1, pp. 487-500. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.71.1.487-500.2005. PMid:15640225.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.71.1.487-5... ), and TgaA, which encodes a protein located on the outer surface of the bacterial cell and interacts with Toll-like receptors, preventing the immune system of epithelial cells from activating (Guglielmetti et al., 2014GUGLIELMETTI, S., ZANONI, I., BALZARETTI, S., MIRIANI, M., TAVERNITI, V., DE NONI, I., PRESTI, I., STUKNYTE, M., SCARAFONI, A., ARIOLI, S., IAMETTI, S., BONOMI, F., MORA, D., KARP, M. and GRANUCCI, F., 2014. Murein lytic enzyme TgaA of Bifidobacterium bifidum MIMBb75 modulates dendritic cell maturation through its cysteine-and histidine-dependent amidohydrolase/peptidase (CHAP) amidase domain. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, vol. 80, no. 17, pp. 5170-5177. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00761-14. PMid:24814791.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00761-14... ).

The candidate genes were screened by their amplification, subsequent capillary sequencing, and bioinformatic analysis of target sequences. The CLC Genomics Workbench program selected specific primers using the MUSCLE algorithms, based on multiple alignments of the selected gene sequences (Table 2).

Total DNA was isolated from pure cultures by phenol-chloroform extraction. Its concentration was measured by a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Gene amplification was performed using 50 μL Tersus polymerase (Evrogen, Russia) according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Table 3).

The amplified genes were purified by horizontal 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The amplicons were purified using a QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, USA). The amplicon concentration was measured with a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

The selection reaction was set up with primers using a BigDye Terminator v3.1 (Applied Biosystems, USA). The sequential reaction was carried out in duplicate for forward and reverse primers for each sample. The 10 μl reaction mixture contained a 3 μl buffer, 1 μl terminator, 29 ng plasmid DNA, and H2O mQ. Libraries were amplified on a C1000 Touch Thermal Cycler. The cycling parameters are presented in Table 4.

The reaction mixture was purified with the BigDye XTerminator Purification Kit. Capillary sequencing was performed on a 3730 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, USA).

The sequencing results were processed using Chromas and CLC Genomics Workbench. Chromas were used to compare repetitions in order to correct errors and detect unread nucleotides in the samples.

The sequences were assembled using the CLC Genomics Workbench software (QIAGEN, USA) and analyzed using the local BLAST algorithms and the GenBank database. Multiple alignment and construction of phylogenetic trees were carried out in the MegaX program.

-

6

Lactic acid bacteria were analyzed for biocompatibility by the drop method, as described by Liu et al. (2019)LIU, J., CHAN, S.H.J., CHEN, J., SOLEM, C. and JENSEN, P.R., 2019. Systems biology: a guide for understanding and developing improved strains of lactic acid bacteria. Frontiers in Microbiology, vol. 10, pp. 876. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00876. PMid:31114552.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.008... . For this, we only used the strains that were cultivated one day. A drop of the first strain was applied onto the surface of the MRS agar. When the drop completely dried, a drop of the second strain was applied, 1–2 mm away from the first drop. The second drop needed to overlap the first one by half. The cultivation lasted 24–48 hours at 37 ºC. The drops of the same strain cultivated as described above were used as a control. The results were determined visually: if the drops fused together, the strains were considered biocompatible; if one of the drops overlapped the other, the strains were considered antagonistic.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Antimicrobial activity of lactic acid strains

The ' agar blocks ' method determined the antimicrobial activity of lactic acid strains against bacterial test cultures (see Table 5).

As we can see in Table 5:

-

Bifidobacterium adolescentis AC-1909, Propionibacterium jensenii B-6085, and Propionibacterium thoenii B-6082 revealed moderate activity against all the test cultures;

-

Bifidobacterium infantis AC-1912 had moderate activity against Salmonella enterica ATCC 14028 and Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 7644, and weak activity against the other test cultures;

-

Propionibacterium freudenreichii B-11921 showed weak activity against Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 7644 and moderate activity against the other test cultures;

-

Propionibacterium acidipropionici B-5723 revealed moderate activity against Salmonella enterica ATCC 14028, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa B6643, and weak activity against Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Proteus vulgaris ATCC 63, and Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 7664.

3.2. Antioxidant activity of lactic acid bacteria

Antioxidant activity (or antiradical effect) of lactic acid bacteria is determined by the DPPH inhibition method (see Figure 2).

As shown in Figure 2, the results showed that all the strains had antioxidant activity, depending on the growth phase. The maximum antioxidant activity for both Bifidobacterium and Propionibacterium were registered at the exponential growth phase (12–24 hours of cultivation). The antiradical effect decreased during the transition to the stationary growth phase.

3.3. Antibiotic resistance of lactic acid cultures

The results of antibiotic resistance of lactic acid cultures are shown in Table 6. The results indicated that:

-

Bifidobacterium adolescentis AC-1909 was moderately resistant to benzylpenicillin and clotrimazole; sensitive to ampicillin and kanamycin; and resistant to all the other antibiotics;

-

Bifidobacterium longum infantis AC-1912 was moderately resistant to polymyxin; sensitive to kanamycin, and resistant to all the other antibiotics;

-

Propionibacterium jensenii was moderately resistant to carbenicillin, polymyxin, and tetracycline; and resistant to all the other antibiotics;

-

Propionibacterium freudenreichii was moderately resistant to gentamicin and neomycin; sensitive to polymyxin, and resistant to all the other antibiotics;

-

Propionibacterium thoenii was moderately resistant to streptomycin, clotrimazole, and chloramphenicol; and resistant to all the other antibiotics;

-

Propionibacterium acidipropionici was moderately resistant to benzylpenicillin, gentamicin, and clotrimazole; sensitive to polymyxin and tetracycline; and resistant to all the other antibiotics.

3.4. The resistance of lactic acid bacteria to adverse gastrointestinal conditions

The results of the resistance of lactic acid bacteria to adverse gastrointestinal conditions – bile, sodium chloride, phenol, and acidity are indicated in Table 7. According to the results, all the strains showed sensitivity to the adverse conditions of the gastrointestinal tract. The lowest resistance was registered to acidity (pH=2.5) when the maximum concentration of bacteria decreased six times. The strains were more resistant to the action of phenol (0.4%) and bile (0.3%), with a four-fold decrease in the maximum concentration. However, the resistance to sodium chloride varied from the highest in Propionibacterium freudenreichii (two-fold decrease in bacterial concentration) to the lowest in Bifidobacterium infantis (five-fold decrease). Thus, we concluded that these bacteria should be encapsulated (immobilized) in order to preserve their useful properties.

3.5. The genetic analysis of lactic acid strains for the presence of gene groups responsible for probiotic properties

The genetic study produced the following gene sequences and phylogenetic trees (see Figures 3-6):

According to the results of Figures 3-6, it can be said that:

-

Propionibacterium freudenreichii B-11921 contains the pcfD and slpB genes and is therefore resistant to antibiotics, which was confirmed by previous studies, and adhesive to intestinal epithelial cells; (See Appendices A Appendix A The pcfD gene sequence for Propionibacterium freudenreichii В-11921 TATGTAGATCTTTGATCTTCAATATGGATCGTCTTGGATGCCCATTTCGATATGGTTTTAGAATGGGATACGATGAGCACAGCTCGGTTCGAAGCAAATTCGTCCAATAGTCTACAAAAGACCAATTCACCTTCTTGGTCTATGTTTGAAGTCGGCTCGTCAAATATAAGCAAATGTTTCATGCTCAAGATAGTTCTTACCCAGGACACGCGCTGCCTCTCGCCCGCCGATAGCCCAGCGCCATTCTGGTATATCTTGCTGTCAAGTCCGTTTGTTGAACTGAGCCTGTTCAAACCTACAAAGTCGAGTAATTCTGCAGCTTCAGAGAGGGTTACTTGACGATTACCAATCCTAATATCATCGATAACTGTTCTGGGGGTAACGGGAAAGTCTTGATCGACGACGGCGATCTCATCCCAGAAGCTTCCAATAGTCCTCATATTTACGAGTGATCCTTTGTAGGAATATGTACCTGATTCGAGTGGGAGCAAACCTTCGATCGCCCGCAGTAGTGTAGTTTTCCCAGTTCCTGATGGGCCAAATATACATACCGATTCGCCTGAGTCAATGGTCAATGAGACCGGTCCGATGACGTGCGTCGCGGTGACCCTGATGACAGCATTCTGAAGATCTATCATATGAGGCCGATTAGGATCCGATAGTTTAGATGGATACCGGTGCGAATTAGATGCTTTATCTGCTTCATGTTGAATTTGCGGCCAGTCATCCGTGTCGAGATCTTGAAGTCTCTTCTTTGACACCGCACATGCCTGTATCGAAAACCAGTAGTTCGAGATCGCTGTAATTTCGGGTGTTAGCAGAGAGTAATACATCATAAAGGCAAGTACAGTCGCTACTGGGGAAGTTGTTTTCGATGCCTGCCACGCTGCGGTAGCGAGCACAACGACTAGACCCAATTGAGCGATTGAGCTGATTGCTGGCCCAAGCGTTGCTCTGAGCTTAGAGTACTGTCTAGCTACTTGATAGTATGAGCGAAGCCTCTTAGATATTTGGACTCGTGCGGAAGAAACGCGTCGGGCGAGAATGAATACACGTCTTGCGAGGAGGAGGCTCTCTATATGTGAGATTACATCGACCTGGGCTACGCGGAGTCGTTCTGATGAGGTGCGTAAGGCT TTAGTGTTTTTAAAAAGGGTGAGACCGACGATACACAGAAAAGCTAACACCACTGCTGTCGACAACGGGTCAATATATATCATTGCTAATATGCAGAACGCAAAGAGCAGTACGGATTTATATATACCTATGAAAGTTGCAAATGTTGTCTCGCTTACGGTCGATGAATCGTATACGATGCGATTCGACACATCGTTATCGTCAGGGAAGCGTGAATTGAACACTGGCCTACTCATGCCGATCGAGAAGGCACTTGTTTGGAGCTCTATCGAAGCGCTCTGCGTCTTAAGGGATAGATAGTACGAGCTGGCTGTAGAGAGGATCGTTTGGAATATTCCAAGAAATAGCACTAGAAAGAGAAGCTTCATAAAAAGCGATGAATTATTCAAAGCCATTAGAGTATTTTGTATAATAATTGGTTGGATCGAAGAAATTCCAACTAC and B Appendix B The slpB gene sequence for Propionibacterium freudenreichii В-11921: ATGTCCGTCAGGAAGAGCCTGACCGGGATGGCGCTGGGGCTTGCCCTCACCATCACCCCGCTCGCTGGCGCGGTTCCGGCGTCAGCCGACACCGCACCGGCCCCCAAGGATGCCATCACCAAGGCAGCCGATTGGCTGGTGAATGATTACAACACCAATTGTCTTGGCGACAAGCAGACAAGTTATAGCTGCTCGAACGGCGGCCTGGCCGATGTCATCCTGGCCCTGTCATCCACCGGTGACGCGAAATATGCCGACGAGATCTCCAGCATGATGGCGAATTTGGCGCCGCAGGTGGCCGGCTACACGAAGGACAATGCGGGCGCCACTGCCAAGATCATCATCACGGCCATTGCCGCCCATCAGAAGCCGAGTGCCTTTGGCGGAAATGACCTGGTGGGCCAGTTGCAGGCACTGAACGCGGAGAACCCCGCCGGTGGCCCGCATGGGGACCACAGTTGTCGGTGGTGGCGCTCACCCGTGCCGGGGAGACCGTCCCTGAAGCGGTGGTCGACGCAACGATCGCCAAGCAGAACAGCAAGGGCGGCTTCGGCTGGGGTGGTGACACGGGCGATGGCGACAACACCGCGATCGGCATGATGGCCACCGCGGCCGTCGCCAAAGGCAACCCCAAGGCAGCCGACTCGCTTGCCAAGGCGGTCGGCTGGGCTCAGGACCCGGCCAACCTCACGACCGATGACACCGGCAGCTACTGGACCAACTACTCGCCCACCAACACTGCGGGCATGATGCTCATGGCCATCGGCGACGTGAACGACCCCAAGATCGACGTCAGCAAGCAGATGGACTTCCTGATCGGTCGCCAGCTGCCCAGTGGTGCCTTCTCGAACACGCTCAAGGGCACCAACGACAATGCGATGGCCACCACCCAGCCCCTCCAGGGCCTCACGATGCACGGCTACCTGACCGCTTCGGCCGGCCAGAAGACTGACCCGGGCACCGGCGGTGGCACGACGGATCCGGGCACCGGCGGCGGCACGGGTGGCGGATCGACCGGCGGCGGCTCAACTGGCGGTGGCGGTAGCACCGGCGGCGGAGGATCGACTGGCGGTGGCGGTAGCACCGGTGGCGGCGGCGTTGTCACGCCCCCGGTCACCCAGGCCTTCACCGATGTTGCCCCGAGCAACATGTACTTCACCGAGATCCAGTGGGCGGCCGCCAACAATGTGACCACCGGCTGGAAGAACGCCGATGGCACGGCGTCGTTCCGTCCGCTCGACACCACGCACCGCGACGCAATGGCGGCGTTCCTCTACCGCCTGAGTGGATCGCCGAGCTACACCGCCCCGGCCACCTCGCCGTTCACCGACGTCAACCCGTCGAACCAGTTCTACAAGGAGATCTGCTGGCTCGCCTCGCAGAACATCACCACCGGCTGGCCCGACGGCAGCTTCCGGCCACTGGACAATGTGAACCGCGACGCGATGGCGGCCTTCCTGTACCGCTACTCGCAGGTCTCGGGCTTCCAGGCCCCGGCTGCTTCGCCGTTCGCTGACGTGACGCCCG ).

-

Bifidobacterium adolescentis AC-1909 and Bifidobacterium longum infantis AC-1912 contain the dnaK and tgaA genes and are therefore resistant to negative environmental factors, regulating the immune system of the host organism. (See Appendices C Appendix C The dnaK gene sequence for Bifidobacterium adolescentis АС-1909: ATGGGACGCGCAGTTGGCATCGATCTGGGTACTACCAATTCCTGCATCGCAACTCTTGAAGGTGGCCAGCCCACCGTTATCGTGAACGCCGAAGGCGCTCGCACCACGCCGTCGGTCGTGGCTTTCAGCAAGTCCGGCGAGATTCTGGTCGGCGAAGTCGCCAAGCGCCAGGCCGTCACCAACGTCGACCGCACCATCAGCTCCGTCAAGCGCCACATGGGCACCGACTGGACCGTTGAGATCGACGGCAAGAAGTGGACGCCGCAGGAGATTTCCGCGCAGGTTCTGATGAAGCTGAAGCGCGATGCCGAGGCCTACCTCGGCGAACCGGTCACCGACGCCGTCATCAC CTGCCCGGCATACTTCAACGACGCCCAGCGTCAGGCCACCAAGGACGCCGGCACCATCGCGGGCCTGAACGTCCTGCGTATCATCAACGAGCCGACCGCAGCCGCACTGGCCTACGGCCTTGAAAAGGGCAAGGAAGACGAGCGCATCCTGGTCTTCGATCTCGGTGGCGGCACCTTCGATGTGTCCCTGCTGGAAATCGGCAAGGACGACGACGGCTTCTCCACCATCCAGGTGCAGGCCACCAACGGCGACAACCACCTGGGCGGCGACGATTGGGACCAGAAGATCATCGACTGGCTCGTCGGCGAAGTCAAGAACAAGTACGGCGTTGACCTGAGCAAGGACAAGATCGCCCTGCAGCGTCTGAAGGAAGCCGCCGAGCAGGCCAAGAAGGAACTGTCCAGCTCCACCAGCACCTCCATCTCCATGCAGTACCTGGCCATGACCCCTGACGGTACCCCGGTGCACCTGGACGAGACCCTGACCCGTGCCCACTTCGAGGAAATGACCTCCGACCTGCTGGGCCGCTGCCGCACCCCGTTCAACAACGTGCTGCGCGACGCTGGCATCAGCGTCTCCGACATCGACCACGTGGTCCTCGTCGGTGGCTCCACCCGTATGCCGGCCGTCAAGGAGCTCGTCAAGGAGCTCACCGGCGGTAAGGAAGCCAACCAGTCCGTGAACCCGGATGAAGTCGTG GCCGTCGGCGCAGCCGTGCAGTCCGGCGTCATCAAGGGCGACCGTAAGGACGTCCTGCTTATCGACGTGACCCCGCTGTCCCTCGGCATCGAAACCAAGGGTGGCATCATGACCAAGCTGATCGAGCGCAACACCGCCATCCCGACGAAGCGTTCCGAAGTCTTCTCCACCGCTGAAGACAACCAGCCGTCCGTGCTCATCCAGGTCTACCAGGGCGAGCGTGAGTTCGCTCGCGACAACTAGCCGCTGGGCACCTTCGAACTGACCGGCATCGCTCCGGCTCCGCGTGGCGTCCCGCAGATCGAAGTCACCTTCGTCGACGCCAACGGCATCGTGCACGTGTCCGCCAAGGACAAGGGCACCGGCAAGGAACAGTCCATGACCATCACCGGTGGTTCCGGCCTGCCGAAGGACGAGATCGACCGCATGGTCAAGGAAGCCGAAGCCCACGAGGCCGAGGACAAGAAGCGCAAGGAAGACGCTGAGACCCGCAACCAGGCCGAGTCCTTCGCCTACCAGACCGAGAAGCTCGTCAACGACAACAAGGACAAGCTCTCCGACGACGTGGCCAAGGAAGTCACCGACAAGGTCAACGAGCTCAAGGAAGCCCTGAAGGGTGAGGACATTGAGAAGATCAAGTCCGCCCAGACCGAGCTGATGACCTCCGCCCAGAAGATCGGCCAGGCCCTCTACGCAC AGCAGGGCGCCGCCGACGCCGCCGGTGCGGCCGGCGCTGCTGGCGCAGGCGCTGCCGGCTCCGCTTCCAACGGCTCCGACGACGACGTGGTTGACGCCGAAGTCGTGGA , D Appendix D The dnaK gene sequence for Bifidobacterium longum infantis АС-1912: CGCAGTTGGTATCGATCTGGGAACCACGAATTCCTGCATCGCAACTCTTGAAGGTGGCGAGCCCACCGTTATCGTCAACGCCGAAGGCGCCCGTACCACGCCGTCCGTGGTGGCCTTCTCCAAGTCCGGCGAGATCCTCGTCGGCGAAGTGGCCAAGCGTCAGGCCGTGACCAACGTTGACCGCACTATTTCTTCCGTCAAGCGCCACATGGGCACCGACTGGACCGTCGACATCGACGGCAAGAAGTGGACCCCGCAGGAGATTTCCGCGCAGATCCTGATGAAGCTGAAGAGGGACGCCGAGGCCTACCTTGGCGAGCCCGTCACCGACGCCGTCATCACCTGCCCGGCATACTTCAACGATGCCCAGCGTCAGGCCACCAAGGACGCCGGCAAGATCGCCGGCCTGAACGTCCTGCGTATCATCAACGAGCCGACCGCAGCCGCTCTGGCCTACGGCCTTGAGAAGGGCAAGGAAGACGAGCGCATCCTGGTCTTCGACCTCGGCGGCGGCACCTTCGATGTCTCCCTGCTGGAGATCGGCAAGGATGACGATGGTTTCTCCACCATCCAGGTCCAGGCCACCAACGGCGACAACCACCTCGGTGGCGACGATTGGGATCAGAAGATCATCGATTGGCTGGTTTCCGAAGTCAAGAACAAGTACGGCGTCGACCTGTCCAAGGACAAGATCGCGCTGCAGCGCCTGAAGGAAGCCGCCGAGCAAGCGAAGAAGTAACTCTCCTCCTCTACCTCCACCAGCATTTCCATGCAGTACCTGGCCATGACCCCCGACGGCACCCCGGTGCACCTGGACGAGACCCTGACCCGCGCGCACTTCGAGGAGATGACCTCCGACCTGCTGGGCCGCTGCCGCACGCCGTTCAACAACGTGCTGCACGATGCCGGCATCTCGGTGAGCGACATCGACCACGTGGTGCTCGTCGGTGGTTCCACCCGTATGCCCGCCGTCAAGGACCTGGTCAAGGAACTCACCGGTGGTATGGAAGCGAACCAGTCCGTGAACCCGGATGAGGTTGTGGCTGTCGGTGCCGCCGTGCAGTCCGGCGTCATCAAGGGCGACCGCAAGGACGTCCTGCTTATCGATGTGACCCCTCTGTCCCTCGGTATCGAGACCAAGGGTGGCATCATGACCAAGCTCATCGATCGCAACACCGCCATCCCGACCAAGCGCTCCGAGGTCTTCTCCACCGCTGAAGACAACCAGCCGTCCGTGCTGATTCAGGTCTACCAGGGTGAACGTGAGGTCGCTCGCGACAACAAGCCGCTGGGCACCTTCGAGCTGACCGGCATCGCTCCGGCGCCGCGTGGCGTCCCGCAGATCGAGGTCACCTTCGACATCGACGCCAACGGCATCGTGCACGTGTCCGCTAAGGACAAGGGCACCGGCAAGGAGCAGTCCATGACCATCACCGGTGGTTCCGGCCTGCCGAAGGACGAGATCGACCGCATGGTCAAGGAAGCCGAGGCTCACGAGGCTGAGGACAAGCAGCGCAAGGAGGACGCCGAGACCCGCAACCAGGCCGAGGCCTTCGCCTACTCCACCGAGAAGCTCGTCAAGGACAACAAGGACAAGCTCTCCGACGACATCGTCAAGGAAGTCACCGACAAGGTCAACGCCCTGAAGGAGGCCCTGAAGGGTGACGACACCGAGAAGGTCAAGACCGCTCAGACCGAGCTGATGACCGCCGCCCAGAAGATCGGCCAGGTCCTCTAC , E Appendix E The tgaA gene sequence for Bifidobacterium adolescentis АС-1909: CGCATAAAGCTGCCAAGGTTTCGCACGCGCAATTCAGCCTATCCAAGGCGTTGTTCACGGCGAACCGGGGCTCCCATACCGCTAAGGCCGTGCGAATGGCACAGCTGGCGGAAGGCGGCGCCGTAGTCGGACTCGCTCCGGAAGTCGTGGATAAACTGAATGAAGTGGCTCCAATGAGCCGCCGTGCCATGCGTGAGGCCGCCAAAGCCGCTTCCCGCAAATCCGCGTTGGTGACCTCCGCTTCGTTGGCGGCGCTTGTCGGCACCGCGGCGACCGCGTTGGCGTTCAGCCAGCAGAACGCATCCCGACTGGTGCTTGCGGACGACGGTACCGAAACGTCCCAGATCAAACGTGTGTCCGATGGAGCGGCATCCCGTTCCGAAGGACGTACCGCCCTTAAGGAACTGGCTTCCACCAGCAACAACGGCGGTTGGCAGCTGGGAGACACTAGCGCCTCCATGGACGCCAGCCTGATGTCCAAGTCCATCGCCGACAATCCGAACGTCGCCGTCCTGATGGACCAAGACAGCAGCGCCTTACCGGCTAACTTCAATCCGAACCATGCCACCGGAGACGTCGGCAACGCCTACGAGTTCAGCCAGTGCACGTGGTGGGTGTATGTGCGCCGCCATCAGCTCGGTCTGCCTGCAGGCTCCCACATGGGCAACGGCTGCCAGTGGGCCGATTCGGCCCGCGCCTTGGGCTATTGGGTTGATAACACGCCGCGCCATGTCGGCGACATCATCGTGTTCGCCGCAGGCCAGGAAGGTTCCGACTCGTATTACGGCCACGTCGCCATCGTTGAGAAAATCAACGACGACGGCTCGATCGTGACCTCTGAATCCGGCGCCTCCCTCAATGGCGGCACGTATTCCCGCACGCTCACGAACGTGGGCGATTTCCAGTATATTC , and F Appendix F The tgaA gene sequence for Bifidobacterium longum infantis АС-1912: GCCGCGCAGTTCGGCTTGGACCGGACCGACATCGCCGATTCCATCGGTCACACCGCCGCCGAGATGGCGGGACGCGCCGGCATGTACGGCATGTCCTCCACCATGCACGGCGTGGGCTGGACGGCCGGCAAGGCGCGGCGCATCATGAACCGCGGCAAACGCGCCCTGCGGTCGGGCAAGGGAATGCGCAAGACGGCCGGCAAACCCAAGGCGCTGTCCGAGGCGAAGCCCAGCGATAAGATCGGCAGGTTCGCCGCGAAAGGCAAGGCGAGCAAGCGGATCGGCAAGCACATAGGCGCGGGCCTTGCAAAAGCCGGCCGGAGCGTCAAACGGATGGGATCCACCGGCATGGGCTGGATGGACGAAGCCGGCGCAAGGCTCACCACTGCCGACGACGACTTCGCGTCGAAGCTGGGAAGCACCACACGCGACCTGTCCTTCAAAGCGGCACGCGCGGGCGTGAAAGGCGTCAACTCGTCGGCCAAATTCATCTGGCGGCACCGCCGCGCGCCGGCCAAGGCGGTACGCGGAGCGAAAGCCACCGGACAGGCCGCCGTGCGCGCCGCCCGCGCCGCCGCGAACTTCGTGCGCATGGCCGCGTCCCGCGTCATCGCAGGAGCCGCCTCCATCAGCCTTCCCATCATGCCCGTCATCGCGGCCATGCTCGCGGTGCTCGGCGTGTCCTGGCCGTCATGGGCGCGTTCCTGGGATCCAGCGCCAGCGAATCCACGGTCGCGGGCATGCCCGCGGAATACGAGGCCGACGTGATCCGCGCCGGATCCATCTGCCAGGTCGTCACGCCGAGCATCATCGCCGCCCAGATCGACCAGGAGTCCAATTGGAATCCGAATGCCGGCAGCTCCGCCGGAGCACGGGGCATCGCACAGTTCATACCGTCCACATGGGCGTCCGCGGGCAAGGTCGGCGACGGCGACGGCCAGGCCGACATCTGGAACCCGCACGACGCGATCTGGAGCCAGGGCAACTACATGTGCGGCCTCGCCTCGCAGGTCGAGACGGCCAAGAAGTCCGGGAAACTGACCGGCGACACGCTCCAGCTGACCCTCGCCGCCTACAACGCCGGCCTTGGCAGCGTCCTGAAATACGGCGGCATACCGCCCTTCACGGAGACCACCAACTACGTGAAACGGATCGTCGACCTGGCCCGGACCAAGTACACCTCCTCGGGCGGTACCGGCGATTCGGGTCCGACCGTCGGCGCGCTGAGCCCGAAACTCGTCATGAGCGACAGCTGGCACGTGAACATTGAGGCCATGGGCCTGCACTACACGCGCTTCCCCGACTACGACACCTACCAGTGCACCTGGTGGGCCGCGATGCGACGCAACCAGATCGGCAAACCCGTCGACGCGCACATGGGCAACGGAGGCCAATGGAACGACACCGCAGCCCGCCTCGGATACAAGGTTGGCCGGAGCCCGAA Figure 4 Phylogenetic tree for Propionibacterium freudenreichii В-11921. Figure 5 Phylogenetic tree for Bifidobacterium longum infantis и Bifidobacterium adolescentis. ).

3.6. Biocompatibility of Bifidobacterium and Propionibacterium

According to Table 8, the results indicated that all the strains under study were biocompatible with each other. Therefore, they can be used to create various consortia for dietary supplements or functional products. Our further study will focus on the probiotic properties of such consortia in order to develop new functional foods.

4. Conclusions

The growing demand for health-benefiting foods is driving the development of functional foods that contain probiotics, especially the Bifidobacterium strains. Recently, however, the ‘dairy’ strains of Propionibacterium have also gained relevance. In addition to having probiotic properties, they produce a bifidogenic compound (1,4-dihydroxy-2-naphthoic acid) that stimulates the growth of bifidobacteria. As a result, probiotic consortia can be formed of these genera to normalize the functioning of the gastrointestinal microbiota. We studied the probiotic properties of lactic acid bacteria of the Bifidobacterium and Propionibacterium genera, namely their antimicrobial and antioxidant activity, as well as resistance to antibiotics and adverse gastrointestinal conditions. According to our results, all the strains under study showed probiotic potential, namely Bifidobacterium adolescentis АС-1909, Bifidobacterium longum infantis АС-1912, Propionibacterium jensenii В-6085, Propionibacterium freudenreichii В-11921, Propionibacterium thoenii В-6082, and Propionibacterium acidipropionici В-5723. We also found them biocompatible, so various consortia can be created from them to normalize the gastrointestinal microflora and prevent a number of chronic diseases.

Appendix A The pcfD gene sequence for Propionibacterium freudenreichii В-11921

TATGTAGATCTTTGATCTTCAATATGGATCGTCTTGGATGCCCATTTCGATATGGTTTTAGAATGGGATACGATGAGCACAGCTCGGTTCGAAGCAAATTCGTCCAATAGTCTACAAAAGACCAATTCACCTTCTTGGTCTATGTTTGAAGTCGGCTCGTCAAATATAAGCAAATGTTTCATGCTCAAGATAGTTCTTACCCAGGACACGCGCTGCCTCTCGCCCGCCGATAGCCCAGCGCCATTCTGGTATATCTTGCTGTCAAGTCCGTTTGTTGAACTGAGCCTGTTCAAACCTACAAAGTCGAGTAATTCTGCAGCTTCAGAGAGGGTTACTTGACGATTACCAATCCTAATATCATCGATAACTGTTCTGGGGGTAACGGGAAAGTCTTGATCGACGACGGCGATCTCATCCCAGAAGCTTCCAATAGTCCTCATATTTACGAGTGATCCTTTGTAGGAATATGTACCTGATTCGAGTGGGAGCAAACCTTCGATCGCCCGCAGTAGTGTAGTTTTCCCAGTTCCTGATGGGCCAAATATACATACCGATTCGCCTGAGTCAATGGTCAATGAGACCGGTCCGATGACGTGCGTCGCGGTGACCCTGATGACAGCATTCTGAAGATCTATCATATGAGGCCGATTAGGATCCGATAGTTTAGATGGATACCGGTGCGAATTAGATGCTTTATCTGCTTCATGTTGAATTTGCGGCCAGTCATCCGTGTCGAGATCTTGAAGTCTCTTCTTTGACACCGCACATGCCTGTATCGAAAACCAGTAGTTCGAGATCGCTGTAATTTCGGGTGTTAGCAGAGAGTAATACATCATAAAGGCAAGTACAGTCGCTACTGGGGAAGTTGTTTTCGATGCCTGCCACGCTGCGGTAGCGAGCACAACGACTAGACCCAATTGAGCGATTGAGCTGATTGCTGGCCCAAGCGTTGCTCTGAGCTTAGAGTACTGTCTAGCTACTTGATAGTATGAGCGAAGCCTCTTAGATATTTGGACTCGTGCGGAAGAAACGCGTCGGGCGAGAATGAATACACGTCTTGCGAGGAGGAGGCTCTCTATATGTGAGATTACATCGACCTGGGCTACGCGGAGTCGTTCTGATGAGGTGCGTAAGGCT

TTAGTGTTTTTAAAAAGGGTGAGACCGACGATACACAGAAAAGCTAACACCACTGCTGTCGACAACGGGTCAATATATATCATTGCTAATATGCAGAACGCAAAGAGCAGTACGGATTTATATATACCTATGAAAGTTGCAAATGTTGTCTCGCTTACGGTCGATGAATCGTATACGATGCGATTCGACACATCGTTATCGTCAGGGAAGCGTGAATTGAACACTGGCCTACTCATGCCGATCGAGAAGGCACTTGTTTGGAGCTCTATCGAAGCGCTCTGCGTCTTAAGGGATAGATAGTACGAGCTGGCTGTAGAGAGGATCGTTTGGAATATTCCAAGAAATAGCACTAGAAAGAGAAGCTTCATAAAAAGCGATGAATTATTCAAAGCCATTAGAGTATTTTGTATAATAATTGGTTGGATCGAAGAAATTCCAACTAC

Appendix B The slpB gene sequence for Propionibacterium freudenreichii В-11921:

ATGTCCGTCAGGAAGAGCCTGACCGGGATGGCGCTGGGGCTTGCCCTCACCATCACCCCGCTCGCTGGCGCGGTTCCGGCGTCAGCCGACACCGCACCGGCCCCCAAGGATGCCATCACCAAGGCAGCCGATTGGCTGGTGAATGATTACAACACCAATTGTCTTGGCGACAAGCAGACAAGTTATAGCTGCTCGAACGGCGGCCTGGCCGATGTCATCCTGGCCCTGTCATCCACCGGTGACGCGAAATATGCCGACGAGATCTCCAGCATGATGGCGAATTTGGCGCCGCAGGTGGCCGGCTACACGAAGGACAATGCGGGCGCCACTGCCAAGATCATCATCACGGCCATTGCCGCCCATCAGAAGCCGAGTGCCTTTGGCGGAAATGACCTGGTGGGCCAGTTGCAGGCACTGAACGCGGAGAACCCCGCCGGTGGCCCGCATGGGGACCACAGTTGTCGGTGGTGGCGCTCACCCGTGCCGGGGAGACCGTCCCTGAAGCGGTGGTCGACGCAACGATCGCCAAGCAGAACAGCAAGGGCGGCTTCGGCTGGGGTGGTGACACGGGCGATGGCGACAACACCGCGATCGGCATGATGGCCACCGCGGCCGTCGCCAAAGGCAACCCCAAGGCAGCCGACTCGCTTGCCAAGGCGGTCGGCTGGGCTCAGGACCCGGCCAACCTCACGACCGATGACACCGGCAGCTACTGGACCAACTACTCGCCCACCAACACTGCGGGCATGATGCTCATGGCCATCGGCGACGTGAACGACCCCAAGATCGACGTCAGCAAGCAGATGGACTTCCTGATCGGTCGCCAGCTGCCCAGTGGTGCCTTCTCGAACACGCTCAAGGGCACCAACGACAATGCGATGGCCACCACCCAGCCCCTCCAGGGCCTCACGATGCACGGCTACCTGACCGCTTCGGCCGGCCAGAAGACTGACCCGGGCACCGGCGGTGGCACGACGGATCCGGGCACCGGCGGCGGCACGGGTGGCGGATCGACCGGCGGCGGCTCAACTGGCGGTGGCGGTAGCACCGGCGGCGGAGGATCGACTGGCGGTGGCGGTAGCACCGGTGGCGGCGGCGTTGTCACGCCCCCGGTCACCCAGGCCTTCACCGATGTTGCCCCGAGCAACATGTACTTCACCGAGATCCAGTGGGCGGCCGCCAACAATGTGACCACCGGCTGGAAGAACGCCGATGGCACGGCGTCGTTCCGTCCGCTCGACACCACGCACCGCGACGCAATGGCGGCGTTCCTCTACCGCCTGAGTGGATCGCCGAGCTACACCGCCCCGGCCACCTCGCCGTTCACCGACGTCAACCCGTCGAACCAGTTCTACAAGGAGATCTGCTGGCTCGCCTCGCAGAACATCACCACCGGCTGGCCCGACGGCAGCTTCCGGCCACTGGACAATGTGAACCGCGACGCGATGGCGGCCTTCCTGTACCGCTACTCGCAGGTCTCGGGCTTCCAGGCCCCGGCTGCTTCGCCGTTCGCTGACGTGACGCCCG

Appendix C The dnaK gene sequence for Bifidobacterium adolescentis АС-1909:

ATGGGACGCGCAGTTGGCATCGATCTGGGTACTACCAATTCCTGCATCGCAACTCTTGAAGGTGGCCAGCCCACCGTTATCGTGAACGCCGAAGGCGCTCGCACCACGCCGTCGGTCGTGGCTTTCAGCAAGTCCGGCGAGATTCTGGTCGGCGAAGTCGCCAAGCGCCAGGCCGTCACCAACGTCGACCGCACCATCAGCTCCGTCAAGCGCCACATGGGCACCGACTGGACCGTTGAGATCGACGGCAAGAAGTGGACGCCGCAGGAGATTTCCGCGCAGGTTCTGATGAAGCTGAAGCGCGATGCCGAGGCCTACCTCGGCGAACCGGTCACCGACGCCGTCATCAC

CTGCCCGGCATACTTCAACGACGCCCAGCGTCAGGCCACCAAGGACGCCGGCACCATCGCGGGCCTGAACGTCCTGCGTATCATCAACGAGCCGACCGCAGCCGCACTGGCCTACGGCCTTGAAAAGGGCAAGGAAGACGAGCGCATCCTGGTCTTCGATCTCGGTGGCGGCACCTTCGATGTGTCCCTGCTGGAAATCGGCAAGGACGACGACGGCTTCTCCACCATCCAGGTGCAGGCCACCAACGGCGACAACCACCTGGGCGGCGACGATTGGGACCAGAAGATCATCGACTGGCTCGTCGGCGAAGTCAAGAACAAGTACGGCGTTGACCTGAGCAAGGACAAGATCGCCCTGCAGCGTCTGAAGGAAGCCGCCGAGCAGGCCAAGAAGGAACTGTCCAGCTCCACCAGCACCTCCATCTCCATGCAGTACCTGGCCATGACCCCTGACGGTACCCCGGTGCACCTGGACGAGACCCTGACCCGTGCCCACTTCGAGGAAATGACCTCCGACCTGCTGGGCCGCTGCCGCACCCCGTTCAACAACGTGCTGCGCGACGCTGGCATCAGCGTCTCCGACATCGACCACGTGGTCCTCGTCGGTGGCTCCACCCGTATGCCGGCCGTCAAGGAGCTCGTCAAGGAGCTCACCGGCGGTAAGGAAGCCAACCAGTCCGTGAACCCGGATGAAGTCGTG

GCCGTCGGCGCAGCCGTGCAGTCCGGCGTCATCAAGGGCGACCGTAAGGACGTCCTGCTTATCGACGTGACCCCGCTGTCCCTCGGCATCGAAACCAAGGGTGGCATCATGACCAAGCTGATCGAGCGCAACACCGCCATCCCGACGAAGCGTTCCGAAGTCTTCTCCACCGCTGAAGACAACCAGCCGTCCGTGCTCATCCAGGTCTACCAGGGCGAGCGTGAGTTCGCTCGCGACAACTAGCCGCTGGGCACCTTCGAACTGACCGGCATCGCTCCGGCTCCGCGTGGCGTCCCGCAGATCGAAGTCACCTTCGTCGACGCCAACGGCATCGTGCACGTGTCCGCCAAGGACAAGGGCACCGGCAAGGAACAGTCCATGACCATCACCGGTGGTTCCGGCCTGCCGAAGGACGAGATCGACCGCATGGTCAAGGAAGCCGAAGCCCACGAGGCCGAGGACAAGAAGCGCAAGGAAGACGCTGAGACCCGCAACCAGGCCGAGTCCTTCGCCTACCAGACCGAGAAGCTCGTCAACGACAACAAGGACAAGCTCTCCGACGACGTGGCCAAGGAAGTCACCGACAAGGTCAACGAGCTCAAGGAAGCCCTGAAGGGTGAGGACATTGAGAAGATCAAGTCCGCCCAGACCGAGCTGATGACCTCCGCCCAGAAGATCGGCCAGGCCCTCTACGCAC

AGCAGGGCGCCGCCGACGCCGCCGGTGCGGCCGGCGCTGCTGGCGCAGGCGCTGCCGGCTCCGCTTCCAACGGCTCCGACGACGACGTGGTTGACGCCGAAGTCGTGGA

Appendix D The dnaK gene sequence for Bifidobacterium longum infantis АС-1912:

CGCAGTTGGTATCGATCTGGGAACCACGAATTCCTGCATCGCAACTCTTGAAGGTGGCGAGCCCACCGTTATCGTCAACGCCGAAGGCGCCCGTACCACGCCGTCCGTGGTGGCCTTCTCCAAGTCCGGCGAGATCCTCGTCGGCGAAGTGGCCAAGCGTCAGGCCGTGACCAACGTTGACCGCACTATTTCTTCCGTCAAGCGCCACATGGGCACCGACTGGACCGTCGACATCGACGGCAAGAAGTGGACCCCGCAGGAGATTTCCGCGCAGATCCTGATGAAGCTGAAGAGGGACGCCGAGGCCTACCTTGGCGAGCCCGTCACCGACGCCGTCATCACCTGCCCGGCATACTTCAACGATGCCCAGCGTCAGGCCACCAAGGACGCCGGCAAGATCGCCGGCCTGAACGTCCTGCGTATCATCAACGAGCCGACCGCAGCCGCTCTGGCCTACGGCCTTGAGAAGGGCAAGGAAGACGAGCGCATCCTGGTCTTCGACCTCGGCGGCGGCACCTTCGATGTCTCCCTGCTGGAGATCGGCAAGGATGACGATGGTTTCTCCACCATCCAGGTCCAGGCCACCAACGGCGACAACCACCTCGGTGGCGACGATTGGGATCAGAAGATCATCGATTGGCTGGTTTCCGAAGTCAAGAACAAGTACGGCGTCGACCTGTCCAAGGACAAGATCGCGCTGCAGCGCCTGAAGGAAGCCGCCGAGCAAGCGAAGAAGTAACTCTCCTCCTCTACCTCCACCAGCATTTCCATGCAGTACCTGGCCATGACCCCCGACGGCACCCCGGTGCACCTGGACGAGACCCTGACCCGCGCGCACTTCGAGGAGATGACCTCCGACCTGCTGGGCCGCTGCCGCACGCCGTTCAACAACGTGCTGCACGATGCCGGCATCTCGGTGAGCGACATCGACCACGTGGTGCTCGTCGGTGGTTCCACCCGTATGCCCGCCGTCAAGGACCTGGTCAAGGAACTCACCGGTGGTATGGAAGCGAACCAGTCCGTGAACCCGGATGAGGTTGTGGCTGTCGGTGCCGCCGTGCAGTCCGGCGTCATCAAGGGCGACCGCAAGGACGTCCTGCTTATCGATGTGACCCCTCTGTCCCTCGGTATCGAGACCAAGGGTGGCATCATGACCAAGCTCATCGATCGCAACACCGCCATCCCGACCAAGCGCTCCGAGGTCTTCTCCACCGCTGAAGACAACCAGCCGTCCGTGCTGATTCAGGTCTACCAGGGTGAACGTGAGGTCGCTCGCGACAACAAGCCGCTGGGCACCTTCGAGCTGACCGGCATCGCTCCGGCGCCGCGTGGCGTCCCGCAGATCGAGGTCACCTTCGACATCGACGCCAACGGCATCGTGCACGTGTCCGCTAAGGACAAGGGCACCGGCAAGGAGCAGTCCATGACCATCACCGGTGGTTCCGGCCTGCCGAAGGACGAGATCGACCGCATGGTCAAGGAAGCCGAGGCTCACGAGGCTGAGGACAAGCAGCGCAAGGAGGACGCCGAGACCCGCAACCAGGCCGAGGCCTTCGCCTACTCCACCGAGAAGCTCGTCAAGGACAACAAGGACAAGCTCTCCGACGACATCGTCAAGGAAGTCACCGACAAGGTCAACGCCCTGAAGGAGGCCCTGAAGGGTGACGACACCGAGAAGGTCAAGACCGCTCAGACCGAGCTGATGACCGCCGCCCAGAAGATCGGCCAGGTCCTCTAC

Appendix E The tgaA gene sequence for Bifidobacterium adolescentis АС-1909:

CGCATAAAGCTGCCAAGGTTTCGCACGCGCAATTCAGCCTATCCAAGGCGTTGTTCACGGCGAACCGGGGCTCCCATACCGCTAAGGCCGTGCGAATGGCACAGCTGGCGGAAGGCGGCGCCGTAGTCGGACTCGCTCCGGAAGTCGTGGATAAACTGAATGAAGTGGCTCCAATGAGCCGCCGTGCCATGCGTGAGGCCGCCAAAGCCGCTTCCCGCAAATCCGCGTTGGTGACCTCCGCTTCGTTGGCGGCGCTTGTCGGCACCGCGGCGACCGCGTTGGCGTTCAGCCAGCAGAACGCATCCCGACTGGTGCTTGCGGACGACGGTACCGAAACGTCCCAGATCAAACGTGTGTCCGATGGAGCGGCATCCCGTTCCGAAGGACGTACCGCCCTTAAGGAACTGGCTTCCACCAGCAACAACGGCGGTTGGCAGCTGGGAGACACTAGCGCCTCCATGGACGCCAGCCTGATGTCCAAGTCCATCGCCGACAATCCGAACGTCGCCGTCCTGATGGACCAAGACAGCAGCGCCTTACCGGCTAACTTCAATCCGAACCATGCCACCGGAGACGTCGGCAACGCCTACGAGTTCAGCCAGTGCACGTGGTGGGTGTATGTGCGCCGCCATCAGCTCGGTCTGCCTGCAGGCTCCCACATGGGCAACGGCTGCCAGTGGGCCGATTCGGCCCGCGCCTTGGGCTATTGGGTTGATAACACGCCGCGCCATGTCGGCGACATCATCGTGTTCGCCGCAGGCCAGGAAGGTTCCGACTCGTATTACGGCCACGTCGCCATCGTTGAGAAAATCAACGACGACGGCTCGATCGTGACCTCTGAATCCGGCGCCTCCCTCAATGGCGGCACGTATTCCCGCACGCTCACGAACGTGGGCGATTTCCAGTATATTC

Appendix F The tgaA gene sequence for Bifidobacterium longum infantis АС-1912:

GCCGCGCAGTTCGGCTTGGACCGGACCGACATCGCCGATTCCATCGGTCACACCGCCGCCGAGATGGCGGGACGCGCCGGCATGTACGGCATGTCCTCCACCATGCACGGCGTGGGCTGGACGGCCGGCAAGGCGCGGCGCATCATGAACCGCGGCAAACGCGCCCTGCGGTCGGGCAAGGGAATGCGCAAGACGGCCGGCAAACCCAAGGCGCTGTCCGAGGCGAAGCCCAGCGATAAGATCGGCAGGTTCGCCGCGAAAGGCAAGGCGAGCAAGCGGATCGGCAAGCACATAGGCGCGGGCCTTGCAAAAGCCGGCCGGAGCGTCAAACGGATGGGATCCACCGGCATGGGCTGGATGGACGAAGCCGGCGCAAGGCTCACCACTGCCGACGACGACTTCGCGTCGAAGCTGGGAAGCACCACACGCGACCTGTCCTTCAAAGCGGCACGCGCGGGCGTGAAAGGCGTCAACTCGTCGGCCAAATTCATCTGGCGGCACCGCCGCGCGCCGGCCAAGGCGGTACGCGGAGCGAAAGCCACCGGACAGGCCGCCGTGCGCGCCGCCCGCGCCGCCGCGAACTTCGTGCGCATGGCCGCGTCCCGCGTCATCGCAGGAGCCGCCTCCATCAGCCTTCCCATCATGCCCGTCATCGCGGCCATGCTCGCGGTGCTCGGCGTGTCCTGGCCGTCATGGGCGCGTTCCTGGGATCCAGCGCCAGCGAATCCACGGTCGCGGGCATGCCCGCGGAATACGAGGCCGACGTGATCCGCGCCGGATCCATCTGCCAGGTCGTCACGCCGAGCATCATCGCCGCCCAGATCGACCAGGAGTCCAATTGGAATCCGAATGCCGGCAGCTCCGCCGGAGCACGGGGCATCGCACAGTTCATACCGTCCACATGGGCGTCCGCGGGCAAGGTCGGCGACGGCGACGGCCAGGCCGACATCTGGAACCCGCACGACGCGATCTGGAGCCAGGGCAACTACATGTGCGGCCTCGCCTCGCAGGTCGAGACGGCCAAGAAGTCCGGGAAACTGACCGGCGACACGCTCCAGCTGACCCTCGCCGCCTACAACGCCGGCCTTGGCAGCGTCCTGAAATACGGCGGCATACCGCCCTTCACGGAGACCACCAACTACGTGAAACGGATCGTCGACCTGGCCCGGACCAAGTACACCTCCTCGGGCGGTACCGGCGATTCGGGTCCGACCGTCGGCGCGCTGAGCCCGAAACTCGTCATGAGCGACAGCTGGCACGTGAACATTGAGGCCATGGGCCTGCACTACACGCGCTTCCCCGACTACGACACCTACCAGTGCACCTGGTGGGCCGCGATGCGACGCAACCAGATCGGCAAACCCGTCGACGCGCACATGGGCAACGGAGGCCAATGGAACGACACCGCAGCCCGCCTCGGATACAAGGTTGGCCGGAGCCCGAA

Acknowledgements

This study was financed by a grant from the President of the Russian Federation and supported by the leading scientific schools (NSh-2694.2020.4).

References

- ABDELAZEZ, A., MUHAMMAD, Z., ZHANG, Q.-X., ZHU, Z., ABDELMOTAAL, H., SAMI, R. and MENG, X., 2017. Production of a functional frozen yogurt fortified with bifidobacterium spp. BioMed Research International, vol. 2017, pp. 6438528. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2017/6438528 PMid:28691028.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2017/6438528 - AFONYUSHKIN, V.N., KECHIN, A.A., TROMENSHLEGER, I.N., FILIPENKO, M.L. and SMETANINA, M.A., 2017. Determination of cell concentrations in stationary growing Lactobacillus salivarius cultures in relation to formation of biofilms and cell aggregates. Microbiology, vol. 86, no. 6, pp. 793-798. http://dx.doi.org/10.1134/S0026261717060030

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1134/S0026261717060030 - ALTIERI, C., 2016. Dairy propionibacteria as probiotics: recent evidences. World Journal of Microbiology & Biotechnology, vol. 32, no. 10, pp. 172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11274-016-2118-0 PMid:27565782.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11274-016-2118-0 - ARGAÑARAZ-MARTÍNEZ, E., BABOT, J.D., APELLA, M.C. and CHAIA, A.P., 2013. Physiological and functional characteristics of Propionibacterium strains of the poultry microbiota and relevance for the development of probiotic products. Anaerobe, vol. 23, pp. 27-37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2013.08.001 PMid:23973927.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2013.08.001 - CAN-HERRERA, L.A., GUTIERREZ-CANUL, C.D., DZUL-CERVANTES, M.A.A., PACHECO-SALAZAR, O.F., CHI-CORTEZ, J.D. and CARBONELL, L.S., 2021. Identification by molecular techniques of halophilic bacteria producing important enzymes from pristine area in Campeche, Mexico. Brazilian Journal of Biology = Revista Brasileira de Biologia, vol. 83, pp. e246038. PMid:34495150.

- CAO, L., CHEN, H., WANG, Q., LI, B., HU, Y., ZHAO, C., HU, Y. and YIN, Y., 2020. Literature-based phenotype survey and in silico genotype investigation of antibiotic resistance in the genus Bifidobacterium. Current Microbiology, vol. 77, no. 12, pp. 4104-4113. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00284-020-02230-w PMid:33057753.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00284-020-02230-w - CARMO, F.L., SILVA, W.M., TAVARES, G.C., IBRAIM, I.C., CORDEIRO, B.F., OLIVEIRA, E.R., RABAH, H., CAUTY, C., SILVA, S.H., CANÁRIO VIANA, M.V., CAETANO, A.C.B., SANTOS, R.G., CARVALHO, R.D.O., JARDIN, J., PEREIRA, F.L., FOLADOR, E.L., LE LOIR, Y., FIGUEIREDO, H.C.P., JAN, G. and AZEVEDO, V., 2018. Mutation of the surface layer protein SlpB has pleiotropic effects in the probiotic Propionibacterium freudenreichii CIRM-BIA 129. Frontiers in Microbiology, vol. 9, pp. 1807. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.01807 PMid:30174657.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.01807 - CELI, P., COWIESON, A.J., FRU-NJI, F., STEINERT, R.E., KLUENTER, A. and VERLHAC, V., 2017. Gastrointestinal functionality in animal nutrition and health: new opportunities for sustainable animal production. Animal Feed Science and Technology, vol. 234, pp. 88-100. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2017.09.012

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2017.09.012 - CELI, P., VERLHAC, V., CALVO, E.P., SCHMEISSER, J. and KLUENTER, A., 2019. Biomarkers of gastrointestinal functionality in animal nutrition and health. Animal Feed Science and Technology, vol. 250, pp. 9-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2018.07.012

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2018.07.012 - CREMONINI, F., DI CARO, S., NISTA, E.C., BARTOLOZZI, F., CAPELLI, G., GASBARRINI, G. and GASBARRINI, A., 2002. Meta-analysis: the effect of probiotic administration on antibiotic-associated diarrhoea. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, vol. 16, no. 8, pp. 1461-1467. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01318.x PMid:12182746.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01318.x - GAUCHER, F., RABAH, H., KPONOUGLO, K., BONNASSIE, S., POTTIER, S., DOLIVET, A., MARCHAND, P., JEANTET, R., BLANC, P. and JAN, G., 2020. Intracellular osmoprotectant concentrations determine Propionibacterium freudenreichii survival during drying. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, vol. 104, no. 7, pp. 3145-3156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00253-020-10425-1 PMid:32076782.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00253-020-10425-1 - GUGLIELMETTI, S., ZANONI, I., BALZARETTI, S., MIRIANI, M., TAVERNITI, V., DE NONI, I., PRESTI, I., STUKNYTE, M., SCARAFONI, A., ARIOLI, S., IAMETTI, S., BONOMI, F., MORA, D., KARP, M. and GRANUCCI, F., 2014. Murein lytic enzyme TgaA of Bifidobacterium bifidum MIMBb75 modulates dendritic cell maturation through its cysteine-and histidine-dependent amidohydrolase/peptidase (CHAP) amidase domain. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, vol. 80, no. 17, pp. 5170-5177. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00761-14 PMid:24814791.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00761-14 - HASHEMI, S.M.B., SHAHIDI, F., MORTAZAVI, S.A., MILANI, E. and ESHAGHI, Z., 2014. Potentially probiotic Lactobacillus strains from traditional Kurdish cheese. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 22-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12602-014-9155-5 PMid:24676764.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12602-014-9155-5 - HUANG, Y., KOTULA, L. and ADAMS, M.C., 2003. The in vivo assessment of safety and gastrointestinal survival of an orally administered novel probiotic, Propionibacterium jensenii 702, in a male Wistar rat model. Food and Chemical Toxicology, vol. 41, no. 12, pp. 1781-1787. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0278-6915(03)00215-1 PMid:14563403.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0278-6915(03)00215-1 - JOMEHZADEH, N., JAVAHERIZADEH, H., AMIN, M., SAKI, M., AL-OUQAILI, M.T., HAMIDI, H., SEYEDMAHMOUDI, M. and GORJIAN, Z., 2020. Isolation and identification of potential probiotic Lactobacillus species from feces of infants in southwest Iran. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 96, pp. 524-530. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.034 PMid:32439543.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.034 - KITAEVSKAYA, S.V., 2012. Current trends in the selection and identification of probiotic strains of lactic acid bacteria. Bulletin of Kazan Technological University, vol. 15, no. 17, pp. 184-188.

- KNYSH, O.V. and NIKITCHENKO, Y.V., 2020. In vitro anti-radical activity of bifidobacterium bifidum and lactobacillus reuteri cell-free extracts. Актуальні проблеми сучасної медицини: Вісник Української медичної стоматологічної академії, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 140-144.

- KUMAR, P., DUBEY, R.C. and MAHESHWARI, D.K., 2012. Bacillus strains isolated from rhizosphere showed plant growth promoting and antagonistic activity against phytopathogens. Microbiological Research, vol. 167, no. 8, pp. 493-499. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2012.05.002 PMid:22677517.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2012.05.002 - KUMARI, R., SINGH, A., YADAV, A.N., MISHRA, S., SACHAN, A. and SACHAN, S.G., 2020. Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics: current status and future uses for human health. In: A. Rodrigues, ed. New and future developments in microbial biotechnology and bioengineering Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 173-190.

- LE BASTARD, Q., AL-GHALITH, G.A., GRÉGOIRE, M., CHAPELET, G., JAVAUDIN, F., DAILLY, E., BATARD, E., KNIGHTS, D. and MONTASSIER, E., 2018. Systematic review: human gut dysbiosis induced by non-antibiotic prescription medications. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 332-345. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/apt.14451 PMid:29205415.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/apt.14451 - LE MARÉCHAL, C., PETON, V., PLÉ, C., VROLAND, C., JARDIN, J., BRIARD-BION, V., DURANT, G., CHUAT, V., LOUX, V., FOLIGNÉ, B., DEUTSCH, S.M., FALENTIN, H. and JAN, G., 2015. Surface proteins of Propionibacterium freudenreichii are involved in its anti-inflammatory properties. Journal of Proteomics, vol. 113, pp. 447-461. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2014.07.018 PMid:25150945.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2014.07.018 - LI, J., GE, Y., ZADEH, M., CURTISS III, R. and MOHAMADZADEH, M., 2020. Regulating vitamin B12 biosynthesis via the cbiMCbl riboswitch in Propionibacterium strain UF1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 117, no. 1, pp. 602-609. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1916576116 PMid:31836694.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1916576116 - LIU, J., CHAN, S.H.J., CHEN, J., SOLEM, C. and JENSEN, P.R., 2019. Systems biology: a guide for understanding and developing improved strains of lactic acid bacteria. Frontiers in Microbiology, vol. 10, pp. 876. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00876 PMid:31114552.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00876 - MARKOWIAK, P. and ŚLIŻEWSKA, K., 2017. Effects of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics on human health. Nutrients, vol. 9, no. 9, pp. 1021. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/nu9091021 PMid:28914794.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/nu9091021 - MARKOWIAK-KOPEĆ, P. and ŚLIŻEWSKA, K., 2020. The effect of probiotics on the production of short-chain fatty acids by human intestinal microbiome. Nutrients, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 1107. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/nu12041107 PMid:32316181.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/nu12041107 - MEILE, L., LE BLAY, G. and THIERRY, A., 2008. Safety assessment of dairy microorganisms: propionibacterium and Bifidobacterium. International Journal of Food Microbiology, vol. 126, no. 3, pp. 316-320. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.08.019 PMid:17889391.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.08.019 - MOODLEY, C., REID, S.J. and ABRATT, V.R., 2015. Molecular characterisation of ABC-type multidrug efflux systems in Bifidobacterium longum. Anaerobe, vol. 32, pp. 63-69. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.12.004 PMid:25529295.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.12.004 - MORITA, C., TSUJI, H., HATA, T., GONDO, M., TAKAKURA, S., KAWAI, K., YOSHIHARA, K., OGATA, K., NOMOTO, K., MIYAZAKI, K. and SUDO, N., 2015. Gut dysbiosis in patients with anorexia nervosa. PLoS One, vol. 10, no. 12, pp. e0145274. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145274 PMid:26682545.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145274 - PIENIZ, S., ANDREAZZA, R., OKEKE, B.C., CAMARGO, F.A. and BRANDELLI, A., 2015. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Enterococcus species isolated from meat and dairy products. Brazilian Journal of Biology = Revista Brasileira de Biologia, vol. 75, no. 4, pp. 923-931. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.02814 PMid:26675908.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.02814 - PYRZYNSKA, K. and PĘKAL, A., 2013. Application of free radical diphenylpicrylhydrazyl (DPPH) to estimate the antioxidant capacity of food samples. Analytical Methods, vol. 5, no. 17, pp. 4288-4295. http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/c3ay40367j

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/c3ay40367j - SHERWIN, E., DINAN, T.G. and CRYAN, J.F., 2018. Recent developments in understanding the role of the gut microbiota in brain health and disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 1420, no. 1, pp. 5-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13416 PMid:28768369.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13416 - TRINDADE, M.I., ABRATT, V.R. and REID, S.J., 2003. Induction of sucrose utilization genes from Bifidobacterium lactis by sucrose and raffinose. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, vol. 69, no. 1, pp. 24-32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.69.1.24-32.2003 PMid:12513973.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.69.1.24-32.2003 - VALDES, A.M., WALTER, J., SEGAL, E. and SPECTOR, T.D., 2018. Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), vol. 361, pp. k2179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2179 PMid:29899036.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2179 - VENTURA, M., ZINK, R., FITZGERALD, G.F. and VAN SINDEREN, D., 2005. Gene structure and transcriptional organization of the dnaK operon of Bifidobacterium breve UCC 2003 and application of the operon in bifidobacterial tracing. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, vol. 71, no. 1, pp. 487-500. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.71.1.487-500.2005 PMid:15640225.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.71.1.487-500.2005 - Yang, Y., Babich, O.O., Stanislav, S., SUKIHIKH, S.A. and MILENTYEVA, I.S., 2020. Antibiotic activity and resistance of lactic acid bacteria and other antagonistic bacteriocin-producing microorganisms. Foods and Raw materials, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 377-384.

- ZÁRATE, G. and CHAIA, A.P., 2012. Influence of lactose and lactate on growth and β-galactosidase activity of potential probiotic Propionibacterium acidipropionici. Anaerobe, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 25-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.12.005 PMid:22202442.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.12.005 - ZIMINA, M., BABICH, O., PROSEKOV, A., SUKHIKH, S., IVANOVA, S., SHEVCHENKO, M. and NOSKOVA, S., 2020. Overview of global trends in classification, methods of preparation and application of bacteriocins. Antibiotics, vol. 9, no. 9, pp. 553. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics9090553 PMid:32872235.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics9090553

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

04 May 2022 -

Date of issue

2024

History

-

Received

04 Oct 2021 -

Accepted

08 Nov 2021