Abstract

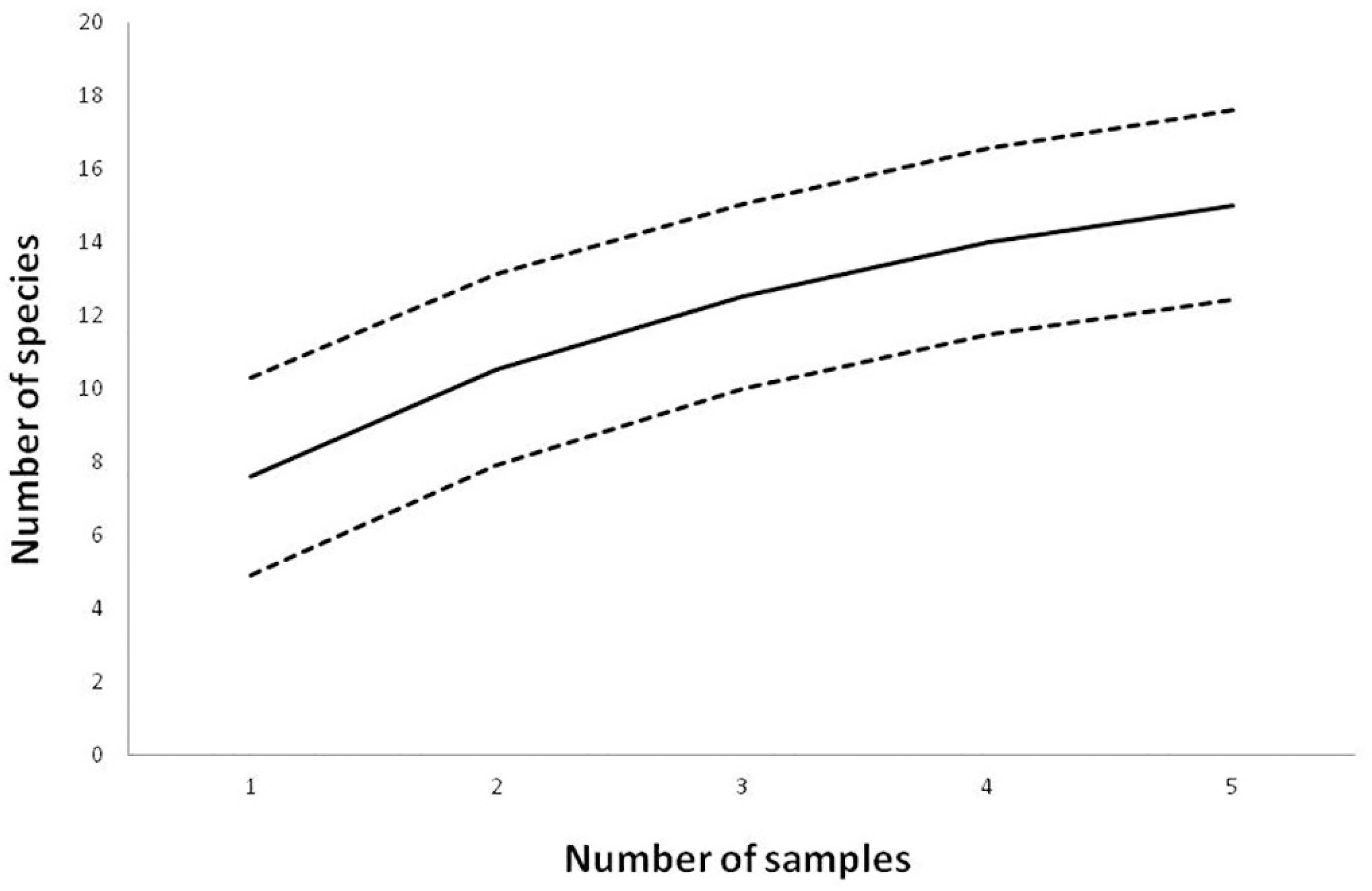

In the present study we analyzed the bat assemblage of the granitic cave Gruta do Riacho Subterrâneo and its surroundings (Itu, São Paulo state, Brazil) aiming to verify the influence of seasonality on its species composition and population abundances. Five samplings were carried out with three days of duration each, along the period from October 2013 to September 2014. Captures of bats were performed by setting mist nets in cave entrances, its interior and surroundings, making a total capture effort of 6,090 m2.h. Our results indicate that this cave is shelter for a rich bat assemblage with fifteen species captured. Carollia perspicillata, Desmodus rotundus and Myotis sp. were the most abundant species. A comparison of the assemblage composition with that of other caves of São Paulo state revealed that its composition is very similar and typical of the Atlantic Forest Atlantic cave chiropterofauna independently of cave lithology. A multiple regression analysis performed to check for the existence of correlation between the seasonal fluctuation of the climatic variables temperature, pluviosity and air humidity did not reveal significant relationships among these and the changes in the abundance of bats. However, the analysis of canonical correspondence including these variables and also moonlight luminosity indicated a significant relationship of the changes in bat abundance with the air relative humidity. Changes in bat abundances are probably related to the seasonality in food availability. The accumulation curve obtained from the relationship between the accumulated richness of species and the number of samples showed that more samplings are required to reach the asymptote of species richness. Considering that Gruta do Riacho Subterrâneo is the largest granitic cave in Brazil and that it shelters a high number of bat species, including common and rare species, we suggests the preservation of this cave for maintenance of bat diversity in São Paulo state.

Keywords

bats; granitic cave; seasonality; biodiversity

Resumo

No presente estudo analisamos a assembleia de morcegos da caverna granítica Gruta do Riacho Subterrâneo e sua área de entorno (Itu, estado de São Paulo, Brasil) com o objetivo de verificar a influência da sazonalidade na composição de espécies e na abundância das populações. Foram realizadas cinco amostragens com duração de três dias cada, ao longo do período de outubro de 2013 a setembro de 2014, utilizando redes-de-neblina instaladas nas entradas, no interior da caverna e em seu entorno, totalizando um esforço de captura de 6.090 m2.h. Nossos resultados indicam que esta caverna abriga uma assembleia rica, onde foram capturadas quinze espécies. Carollia perspicillata, Desmodus rotundus e Myotis sp. foram as espécies mais abundantes. A comparação da composição desta assembleia com a de outras cavernas do estado de São Paulo revelou que suas espécies são similares e típicas da quiropterofauna de cavernas da Mata Atlântica, independentemente da litologia das mesmas. A análise de regressão múltipla utilizada para a relação entre a variação sazonal das variáveis temperatura, pluviosidade e umidade relativa do ar não revelou correlação significativa entre estas e as variações na abundância das diferentes espécies de morcegos. Contudo a análise de correspondência canônica incluindo, além destas, a variável luminosidade da lua indicou uma correlação significativa com a umidade relativa do ar. As variações nas abundâncias dos morcegos provavelmente estão relacionadas à sazonalidade na disponibilidade de alimento. A curva de acumulação obtida pela relação entre a riqueza de espécies e o número de amostragens acumuladas mostrou que mais amostragens são necessárias para atingir a assíntota da riqueza de espécies. Considerando-se que a Gruta do Riacho Subterrâneo é a maior caverna granítica do Brasil e que abriga uma elevada riqueza de espécies de morcegos, incluido raras e comuns, nós sugerimos a preservação desta caverna para a manutenção da diversidade morcegos no estado de São Paulo.

Palavras-chave

morcegos; caverna granítica; sazonalidade; biodiversidade

Introduction

Bats are one of the most successful groups of mammals on Earth. This, in part, is due to several evolutionary traits acquired, such as flight capacity, echolocation ability and nocturnal habits. In Brazil, bats represent 25% of the mammals described, totaling 179 species distributed in 68 genera and nine families, a significatively high diversity that represents 16% of the species described in the world and still increasing with the new findings in this decade (Gardner 2007GARDNER, A. L. 2007. Mammals of South America, volume 1: marsupials, xenarthrans, shrews, and bats. University of Chicago Press., Paglia et al. 2012PAGLIA, A. P., FONSECA, G. D., RYLANDS, A. B., HERRMANN, G., AGUIAR, L. M. S., CHIARELLO, A. G. & PATTON, J. L. 2012. Lista anotada dos mamíferos do Brasil. Occasional Papers in Conservation Biology. 6:1-76., Nogueira et al. 2014NOGUEIRA, M. R., LIMA, I. P. MORATELLI, R. CUNHA TAVARES, V. GREGORIN, R. & PERACCHI, A. L. 2014. Checklist of Brazilian bats, with comments on original records. Check List. p. 808-821.).

Bats are the only mammals that successfully explore the caves (Kunz 1982KUNZ, T.H. 1982. Roosting Ecology of bats. In Ecology of bats (T.H. KUNZ, Ed). New York, Plenum Press, p. 1-55.), permanently establishing trogloxenes populations (organisms with epigean source populations) that use resources from subterranean habitats, as shelter, for instance, but also bringing organic material from the epigean environment (Trajano 2012TRAJANO E, 2012. Ecological classification of subterranean organisms. In Encyclopedia of Caves (White W.B. & Culver D. C, Eds). Amsterdam: Elsevier. p. 275-277.). Ecologically, bats have an important role on caves, because their faeces, known as guano, represent an energy source to the subterranean biota (Gnaspini & Trajano 2000GNASPINI, P. & TRAJANO, E. 2000. Guano Communities in tropical caves. In Ecosystems of the World: Subterranean Ecosystems (D. C. CULVER, W. F. W HUMPHREYS & H WILKENS, Eds.). Elsevier. Amsterdam, The Netherlands, p.251 - 268.).

Many species of bats use caves as shelters (Kunz & Lumsden 2003KUNZ, T. H. & LUMSDEN, L. F. 2003. Ecology of cavity and foliage roosting bats. In Bat Ecology (KUNZ, T. H & FENTON, M. B., Eds). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, p. 3-89.) seeking protection against climate variation, predation and potential competitors (Kunz 1982). Their preferences regarding shelters are also influenced by structure, distribution and diversity of caves and abundance of resources (Trajano 1985TRAJANO, E. 1985. Ecologia de populações de morcegos cavernícolas em uma região cárstica do sudeste do Brasil, Curitiba, Brasil, Rev. Brasil. Zool. 2:55-320., Kunz & Lumsden 2003KUNZ, T. H. & LUMSDEN, L. F. 2003. Ecology of cavity and foliage roosting bats. In Bat Ecology (KUNZ, T. H & FENTON, M. B., Eds). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, p. 3-89.).

There are a number of studies in the Southeast Brazil regarding cave chiropteran assemblages. Among them are the studies on cave-dwelling bats at the Atlantic Forest in Vale do Ribeira, São Paulo carried out by Trajano (1985)TRAJANO, E. 1985. Ecologia de populações de morcegos cavernícolas em uma região cárstica do sudeste do Brasil, Curitiba, Brasil, Rev. Brasil. Zool. 2:55-320. and by Campanhã & Fowler (1993)CAMPANHÃ, R. A. & FOWLER, H. G. 1993. Roosting assemblages of bats in arenitic caves in remnant fragments of Atlantic Forest in Southeastern Brazil. Biotropica. 25:362-365. also in remnant fragments of Atlantic Forest in Corumbataí municipality, São Paulo. For other regions of Brazil, in the North it can be cited the study of Cajaiba (2014)CAJAIBA, R. L. 2014. Morcegos (Mammalia, Chiroptera) em cavernas no município de Uruará, Pará, norte do Brasil. Bio. Amaz. 4: 81-86. in sandstone caves in Uruará, Pará; in the west central region Bredt et al. (1999)BREDT, A., MAGALHÃES, E.D. & UIEDA, W. 1999. Morcegos cavernícolas da região do Distrito Federal, Centro-oeste do Brasil (Mammalia, Chiroptera). Rev. Bras. de Zool. 16:731-770. studied the bat assemblages of 20 caves in Federal District, which have the Cerrado as the predominant vegetation and Esbérard et al. (2005)ESBÉRARD, C. E. 2007. Influência do ciclo lunar na captura de morcegos Phyllostomidae. Iheringia, sér. Zool. 97: 81-85., who studied the caves of an Environmental Protection Area caves also predominantly in the Cerrado, in the state of Goiás. In the South region Arnone & Passos (2007)ARNONE, I. S. & PASSOS, F. C. 2007. Estrutura de comunidade da quiropterofauna (Mammalia, Chiroptera) do Parque Estadual de Campinhos, Paraná, Brasil. Rev. Bras. de Zool. 24: 573-581. studied the bat assemblages caves located in mixed Atlantic Rainforest in the state of Paraná. Bat assemblages of Northeast have were analized by Sbragia & Cardoso (2008)SBRAGIA, I. A. & CARDOSO, A. 2008. Quiropterofauna (Mammalia: Chiroptera) cavernícola da Chapada Diamantina, Bahia, Brasil. Chirop. Neotrop. 14:360-365. for caves in Cerrado Atlantic Forest and Caatinga in Bahia. These authors evidenced the relevance of studies on cave environments, due to their capacity to provide shelters for species that are relevant to the functioning of these habitats and associated communities. A review of data on bat assemblages of several Brazilian caves is provided by Guimarães & Ferreira (2014)GUIMARÃES, M. M. & FERREIRA, R. L. 2014. Morcegos cavernícolas do Brasil: novos registros e desafios para conservação. Revista Brasileira de Espeleologia. 2:1-33..

Bats occupy caves of different lithologies, as observed by Trajano (1985)TRAJANO, E. 1985. Ecologia de populações de morcegos cavernícolas em uma região cárstica do sudeste do Brasil, Curitiba, Brasil, Rev. Brasil. Zool. 2:55-320. and by Bredt et al. (1999)BREDT, A., MAGALHÃES, E.D. & UIEDA, W. 1999. Morcegos cavernícolas da região do Distrito Federal, Centro-oeste do Brasil (Mammalia, Chiroptera). Rev. Bras. de Zool. 16:731-770., who concluded that the selection of cave shelters can be more influenced by the amount of other caves in the area than by the cave characteristics. Àvilla-Flores & Medellín (2001)AVILA-FLORES, R. & MEDELLÍN, R. A. 2004. Ecological, taxonomic, and physiological correlates of cave use by Mexican bats. J. Mammal, 85: 675-687. found that for bat assemblages of 18 caves in Mexico, the lithology (limestone and silisiclastic caves) had no significant effect on bat selection of caves. Nevertheless, cave attributes as size and complexity can be important for bat assemblage species composition. For example, Brunet & Meddellin (2001)BRUNET, A. K. & MEDELLÍN, R. A. 2001. The species-area relationship in bat assemblages of tropical caves. J. Mammal, 82: 1114-1122. also for bat cave assemblages in Mexico found a positive relationship between species richness and cave surface area and complexity.

Granitic caves are relatively rare when compared to carbonatic ones (Juberthie 2000JUBERTHIE, C. 2000. The diversity of the karstic and pseudokarstic hypogean habitats in the world. In Ecosystems of the World: Subterranean Ecosystems (H. Wilkens, D.C. Culver & W.F. Humphreys, Eds). Elsevier. Amsterdam, The Netherlands, p.17-40.). Usually granitic caves are small, may vary in shape (Twidale & Bourne 2008TWIDALE, C. R. & BOURNE, J. A. 2008. Caves in granitic rocks: types, terminology and origins. Cadernos do Laboratorio Xeolóxico de Laxe: Revista de xeoloxía galega e do hercínico peninsular. 33:35-57.) and their final structure is shaped mainly by the power of water (Romaní et al. 2010ROMANÍ, R. V., SANJURJO SANCHEZ, J. J., RODRÍGUEZ, M. & MOSQUERA, F. D. 2010. Speleothem development and biological activity in granite cavities. Geomorphologie: relief, processes, environment. 4: 337-346.). They are often formed by large agglomerates of blocks with many openings, becoming natural entrances to the subterranean environment. The high number of openings observed in granitic caves leads to a direct influence of the surface environment on their communities (Romaní et al. 2010ROMANÍ, R. V., SANJURJO SANCHEZ, J. J., RODRÍGUEZ, M. & MOSQUERA, F. D. 2010. Speleothem development and biological activity in granite cavities. Geomorphologie: relief, processes, environment. 4: 337-346.). Studies comparing granitic and other lithology caves regarding bats species composition have not yet been published in Brazil.

Several studies on bat populations from different regions analyze the influence of seasonality (dry and wet seasons) on the assemblage composition, diet and population densities showing that the main factor for changes is the food availability throughout the year, which is in turn influenced by seasonality (Stevens & Amarilla-Stevens 2012STEVENS, R. D. & AMARILLA-STEVENS, H. N. 2012. Seasonal environments, episodic density compensation and dynamics of structure of chiropteran frugivore guilds in Paraguayan Atlantic forest. Biodivers. Conserv. 21 (1): 267-279.). This fact was evidenced for bat assemblages from the Amazonian forest (Bobrowiec et al. 2014BOBROWIEC, P. E. D., ROSA, L. d. S., GAZARINI, J. & HAUGAASEN, T. 2014. Phyllostomid Bat Assemblage Structure in Amazonian Flooded and Unflooded Forests. Biotropica. 46:312-321.) and from Atlantic Rainforest (Ribeiro-Mello 2009RIBEIRO MELLO, M. A. 2009. Temporal variation in the organization of a Neotropical assemblage of leaf-nosed bats (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae). Acta Oecol. p.280-286., Ortêncio-Filho et al. 2010ORTÊNCIO FILHO, H., REIS, N. R. & MINTE-VERA, C. V. 2010. Time and seasonal patterns of activity of phyllostomid in fragments of a stational semidecidual forest from the Upper Paraná River, Southern Brazil. Braz. J. Biol. p. 937-945., Stevens & Amarilla-Stevens 2012STEVENS, R. D. & AMARILLA-STEVENS, H. N. 2012. Seasonal environments, episodic density compensation and dynamics of structure of chiropteran frugivore guilds in Paraguayan Atlantic forest. Biodivers. Conserv. 21 (1): 267-279., Stevens 2013STEVENS, R. D. 2013. Gradients of Bat Diversity in Atlantic Forest of South America: Environmental Seasonality, Sampling Effort and Spatial Autocorrelation. Biotropica. 45:764-770., Lourenço et al. 2014LOURENÇO, E. C., GOMES, L. A. PINHEIRO, M. C. PATRÍCIO, P. M. P. & FAMADAS, K. M. 2014. Composition of bat assemblages (Mammalia: Chiroptera) in tropical riparian forests. Int. J.Zool. 31:361-369.). For cave bats from Atlantic Rainforest in the Alto Ribeira region, São Paulo state, Trajano (1985)TRAJANO, E. 1985. Ecologia de populações de morcegos cavernícolas em uma região cárstica do sudeste do Brasil, Curitiba, Brasil, Rev. Brasil. Zool. 2:55-320. and Arnone (2008)ARNONE, I. S. 2008. Estudo da comunidade de morcegos na área cárstica do Alto Ribeira - SP. Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade São Paulo, São Paulo. suggested the existence of seasonality, at least for some species.

We analyzed herein the bat assemblage of the granitic cave Gruta do Riacho Subterrâneo and its surroundings. The analysis is based on the changes in the species composition and population relative abundances during twelve months, involving periods of contrasting pluviosity to test the hypothesis that seasonality affect bat assemblages.

Methodology

1. Studied Area.

The cave studied is the "Gruta do Riacho Subterrâneo" (23°16'10.40"S, 47°13'49.79"W, 726 m above sea level), located in the city of Itu - state of São Paulo, Brazil, and belongs to Itu's post-orogenic granite suite (Grupo Pierre Martin de Espeleologia 2014) (Figure 1 A, B). This cave is amongst the six largest granite caves in the world, and it is so far the largest of the Southern Hemisphere, with approximately 1,415 meters of linear development, formed by the superposition of several blocks. The cave has many entrances offering various routes for bats.

(A) Maps showing the location of Gruta do Riacho Subterrâneo in South America and in Itu municipality, SP. (B) Geological formation

The region where the cave is located is characterized by humid subtropical climate with dry winters and warm summers (Cfa) according to Köeppen (1948). The regional vegetation is a transition of Cerrado, ombrophilous dense forest, stational semidecidual forest, and the ecotone zone among these vegetations (Rizzini 1997RIZZINI, C. T. 1997. Tratado de Fitogeografia do Brasil. Âmbito Cultural Edições Ltda, Rio de Janeiro. Brasil.). Vegetation around the cave is nevertheless under strong anthropogenic pressure since the beginning of economic development in the São Paulo state highlands (Grupo Pierre Martin de Espeleologia 2014). In the surrounding area there is a small stream close to the cave and another in its interior, providing water resources to the bat assemblage and other communities present. Also, there is a small cave at a few meters distance and a large one at approximately 6 Km. It must be pointed out that several fires happened in 2010 in the surroundings of Gruta do Riacho Subterrâneo cave (Bichuette, M. E. personal observation) evidencing another type of disturbance the cave and its surrounding area undergo, making them even more altered.

Due to the granitic origin of the cave it is difficult to precisely establish the amount of existing saloons, since this is a non-regular cave along its whole extension being formed by superimposed granitic blocks, thus offering many entrances and possible routes to bats.

2. Bat Samplings and Environmental Variables Measurements

Samplings were carried out every two or three months in the period from October 2013 to September 2014. The first sampling (pilot) took place in August 2013, in order to define where the mist-nets could be placed. Table 1 shows the sampling dates, with October, December and March representing the rainy season and June and September representing the dry one (INMET 2014INMET. http://www.inmet.gov.br (last access 22/08/2014).

http://www.inmet.gov.br...

).

Four or five mist-nets were set at the entrances of the caves in each of the three sampling days. Two other nets were set outside the cave (in a pasture and near a stream), in the first and in the third sampling days. These places were defined considering their dimensions and accessibility (Figure 2). It is important to emphasize that the cave has many entrances, so it is difficult to cover all possible routes for bats. The mist nets had three different sizes (4 x 3 m; 6 x 3 m and 7 x 3 m), installed in according to the entrance sizes. In the pasture we used a 7 x 3 m net and close the stream a 4 x 3 m net. The nets were set before sunset and were exposed for five hours, with regular checks every 20-30 minutes.

After captured, the specimens were identified on-site at species or genus level, and some were kept to allow a more accurate identification in the laboratory by utilizing specific identification keys (Vizzoto & Taddei 1973VIZZOTO, L.D. & TADDEI, V. A. 1973. Chave para determinação de quirópteros brasileiros. São José do Rio Preto, gráfica Francal., Gardner 2007GARDNER, A. L. 2007. Mammals of South America, volume 1: marsupials, xenarthrans, shrews, and bats. University of Chicago Press. and Reis et al. 2013REIS, N. R., PERACCHI, A. L., PERACCHI, A. L. & SHIBATTA, O. A. 2013. Morcegos do Brasil. Guia de Campo. Ed. Technical Books. Brasil.). The specimens were deposited in the reference collection at Subterranean Studies Laboratory of the Federal University of São Carlos (LES - UFSCar).

Measurements of temperature (°C) and relative humidity (%) were obtained with a thermo-hygrometer (Instrutherm THAL-300; 0.1 resolution ± 5.0% accuracy) and monthly precipitation values were obtained from the National Institute of Meteorology (INMET, 2014), from the nearest station of Itu municipality. The moon phase was recorded in each collection day and posteriorly checked in a moon phase Table for each sampling day and month. To attribute a value for the moonlight luminosity of each lunar phase we used the following scale: new moon = one, horning = two, waning = tree, and full moon = four, as usually suggested for quantitative analysis based on qualitative evaluations.

3. Data Analysis

Capture effort was calculated according to Straube & Bianconi (2002)STRAUBE, F.C. & BIANCONI, G. V. 2002. Sobre a grandeza e a unidade utilizada para estimar esforço de captura com utilização de redes-de-neblina. Chirop. Neotrop. 8:150-152.. A sample-based species accumulation curve was plotted to analyze the Sufficiency Sampling Size, using "EstimateS" software (Colwell 2005COLWELL, R. K. 2005. EstimateS: Statistical estimation of species richness and shared species from samples. Version 7.5.). The relative abundance of each species was calculated and expressed as a percentage of the total assemblage abundance, in order to show their representativeness in the assemblage.

A multiple regression analysis was performed to verify the influence of the abiotic variables (temperature, relative humidity and pluviosity) over the abundance of the assemblage. Later on, the Akaike information criterion (AIC) was applied, in order to select the best representative model (Akaike 1970). A canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) was performed to verify the influence of the abiotic data matrix (temperature, relative humidity, moonligth and pluviosity) over the species abundance and assemblage richness. These analyses were carried out using the statistical software "R Development Core Team 2011".

Results

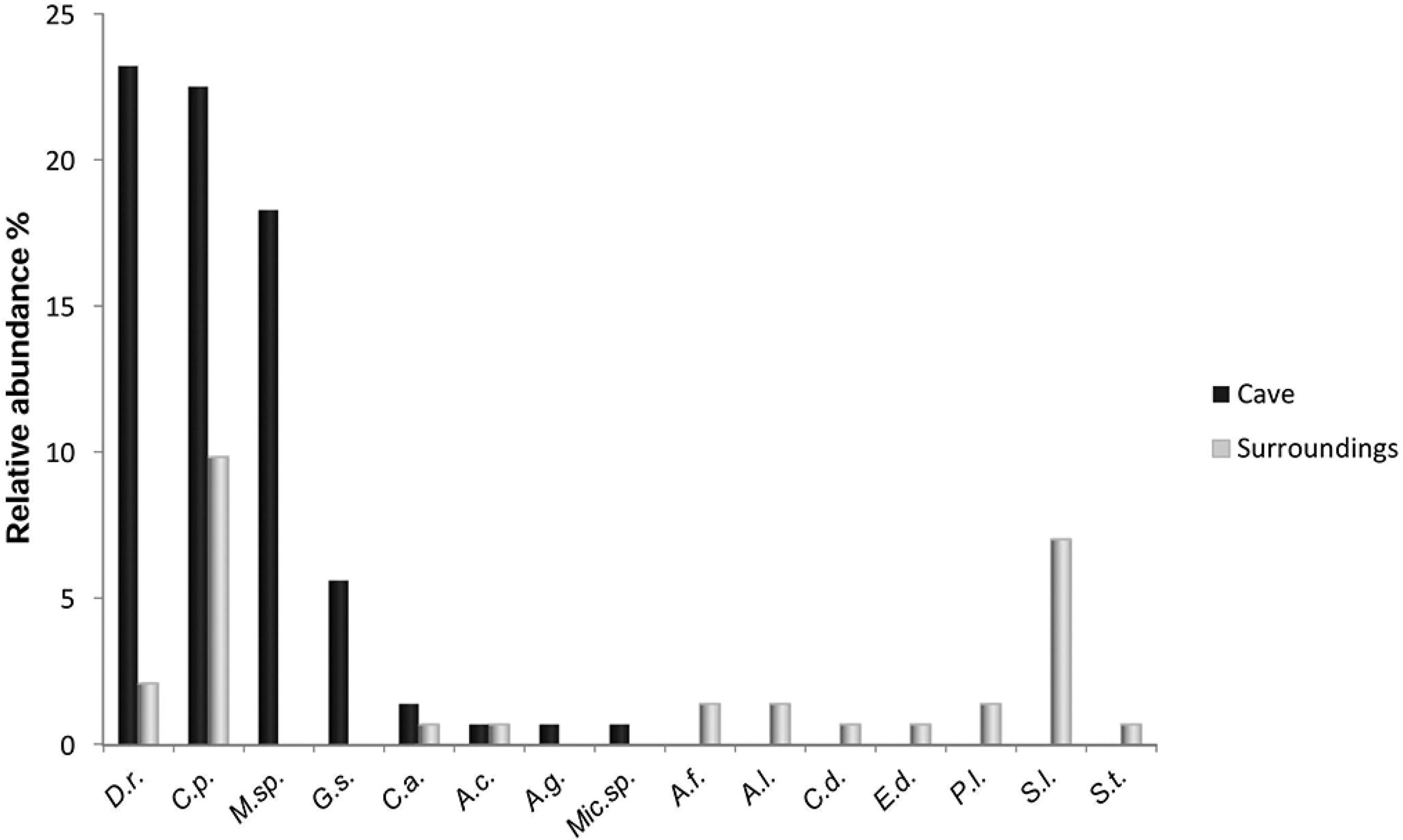

The capture effort was 6,090 m2. h resulting on 113 captured individuals belonging to 15 species and two families. Eight species were recorded in the mist-nets settled in the cave (entrance and interior) and 11 were recorded in the cave surroundings, approximately 20 meters from the rocky outcrop that contains the cave (near the external stream and near the pasture) (Table 2). Amongst the captured bats, around 80% belonged to the Phyllostomidae family, while the others were represented by species belonging to the Vespertilionidae family. In Figure 3 the species accumulation curve is presented showing that the curve asymptote was not reached.

Species recorded and feeding habits for bat assemblage of Gruta do Riacho Subterrâneo and surroundings, Itu municipality, SP.

Accumulation curve for the species sampled at Gruta do Riacho Subterrâneo cave, Itu municipality, SP. Solid line represents the rarefaction curve and the dotted lines represent the 95% confidence limits.

Figure 4 shows the relative abundances of the species, organized according to the environment in which they were found (outside or inside the cave). Some species were more abundant, such as Carollia perspicillata (30.8%), Desmodus rotundus (29.6%) and a species of genus Myotis sp. (23.4%), while others were much less abundant and even had single capture events, such as Anoura geoffroyi, Micronycteris sp., Chiroderma doriae, Sturnira tildae and Eptesicus diminutus.

Bat relative abundances recorded for Gruta do Riacho Subterrâneo cave and surroundings, Itu municipality, SP. D. r. = Desmodus rotundus; C. p. = Carollia perspicillata; M. sp = Myotis sp.; G. s. = Glossophaga soricina; C. a. = Chrotopterus auritus; A. c. = Anoura caudifer; A. g. = Anoura geoffroyi; Mic.sp = Micronycteris sp.; A. f. = Artibeus fimbriatus; A.l. = Artibeus lituratus; C.d. = Chiroderma doriae; E.d.= Eptesicus diminutus; P.l. = Platirhynus lineatus; S. l. = Sturnira lilium; S.t. = Sturnira tildae.

Bat abundances were not related to environmental variables as indicated by the multiple regression analysis (F = 0.344, df = 3, p = 0.833; temperature, p = 0.495; relative humidity, p = 0.587 and pluviosity, p = 0.525). The application of the Akaike information criterion showed that using the three abiotic variables together would be the model resulting less information loss in data analysis. In the canonical correspondence analysis the relative humidity was the most important factor in the first axis, positively related to the bat assemblage richness and population abundances of the species A. caudifer, P. lineatus, A. fimbriatus and S. lilium in the months of March and September and negatively related with the abundances of Micronycteris sp. and A. geoffroyi in the months of December and October (Table 3). Pluviosity representing the main factor in axis two was not significantly related with bat abundances (Figure 5 A). The variables temperature and moonlight were not significantly related to the abundance of the species (Fig. 5 B).

Canonical correspondence analysis valoes of the correlation between abiotic variables and bat species abundances.

Canonical correspondence analysis relating relative humidity and pluviosity and bat richness and abundances at Gruta do Riacho Subterrâneo and surroundings, Itu municipality, SP. A. cau = Anoura caudifer; P. lin. = Platirhynus lineatus; A. fim = Artibeus fimbriatus; A. lit = Artibeus lituratus; G. sor. = Glossophaga soricina; Mic = Micronycteris sp.; A. geo = Anoura geoffroyi; Myo = Myotis sp.; D. rot. = Desmodus rotundus; C. aur = Chrotopterus auritus; S. lil = Sturnira lilium; C. per = Carollia perspicillata.; Oct = October 2013; Dec. = December 2013; Mar = March, 2014; Jun = June 2014 and Sep = September, 2014.

Figure 5B

Canonical correspondence analysis relating temperature and moonlight on bat richness and abundances at Gruta do Riacho Subterrâneo and surroundings, Itu municipality, SP. A. cau = Anoura caudifer; P. lin. = Platirhynus lineatus; A. fim = Artibeus fimbriatus; A.lit = Artibeus lituratus; G.sor. = Glossophaga soricina; Mic = Micronycteris sp.; A. geo = Anoura geoffroyi; Myo = Myotis sp.; D. rot. = Desmodus rotundus; C. aur = Chrotopterus auritus; S. lil = Sturnira lilium; C. per = Carollia perspicillata.; Oct = October 2013; Dec. = December 2013; Mar = March, 2014; Jun = June 2014 and Sep = September, 2014.

Discussion

1. Bat Assemblage Composition

Among the 15 species recorded in this study only eight were found in the interior of Gruta do Riacho Subterrâneo, whereas the other seven were captured in the surroundings. From the eight species found in the interior of this granitic cave, six were already recorded by Trajano (1985)TRAJANO, E. 1985. Ecologia de populações de morcegos cavernícolas em uma região cárstica do sudeste do Brasil, Curitiba, Brasil, Rev. Brasil. Zool. 2:55-320. and by Arnone (2008)ARNONE, I. S. 2008. Estudo da comunidade de morcegos na área cárstica do Alto Ribeira - SP. Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade São Paulo, São Paulo. in Vale do Ribeira Atlantic Rainforest caves. Individuals from two genera, Myotis sp. and Micronycteris sp. could not be included in the comparison because they were not yet identified to the species level.

Among the seven species collected only in the surroundings of the Gruta do Riacho Subterrâneo (pasture or native vegetation) six have also been previously recorded by Trajano (1985)TRAJANO, E. 1985. Ecologia de populações de morcegos cavernícolas em uma região cárstica do sudeste do Brasil, Curitiba, Brasil, Rev. Brasil. Zool. 2:55-320. and by Arnone (2008)ARNONE, I. S. 2008. Estudo da comunidade de morcegos na área cárstica do Alto Ribeira - SP. Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade São Paulo, São Paulo. in Vale do Ribeira caves. Only one species, Epitesicus diminutus, captured in the pasture nearby the cave, was not previously recorded by these two authors in Vale do Ribeira caves. According to Reis et al. (2013)REIS, N. R., PERACCHI, A. L., PERACCHI, A. L. & SHIBATTA, O. A. 2013. Morcegos do Brasil. Guia de Campo. Ed. Technical Books. Brasil. this species is found in primary and secondary forests and forest fragments, but also in open areas and urban environments. In São Paulo State it was previously recorded in the Atlantic Forest at Morro do Diabo State Park, where it is also a rare species (Reis et al. 1995REIS, N. R., PERACCHI, A. L., MULLER, M. F., BASTOS, E. A. & SOARES, E. S. 1995. Quirópteros do Parque Estadual Morro do Diabo, Sao Paulo Brasil (Mammalia: Chiroptera). Rev. Bras. Biol. 56:87-92.).

Only three species abundant in the assemblage studied, the species C. perspicillata and D. rotundus and Myotis sp.. Two of them were also abundant in bat assemblages of other caves in São Paulo state (Trajano 1985TRAJANO, E. 1985. Ecologia de populações de morcegos cavernícolas em uma região cárstica do sudeste do Brasil, Curitiba, Brasil, Rev. Brasil. Zool. 2:55-320., Campanhã & Fowler 1993CAMPANHÃ, R. A. & FOWLER, H. G. 1993. Roosting assemblages of bats in arenitic caves in remnant fragments of Atlantic Forest in Southeastern Brazil. Biotropica. 25:362-365., Arnone 2008ARNONE, I. S. 2008. Estudo da comunidade de morcegos na área cárstica do Alto Ribeira - SP. Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade São Paulo, São Paulo.).

Comparing the species composition of the bat assemblage in the granitic cave Gruta do Riacho Subterrâneo with those from caves with different lithologies in São Paulo State, as the calcareous caves of Alto do Ribeira (Trajano 1985TRAJANO, E. 1985. Ecologia de populações de morcegos cavernícolas em uma região cárstica do sudeste do Brasil, Curitiba, Brasil, Rev. Brasil. Zool. 2:55-320., Arnone 2008ARNONE, I. S. 2008. Estudo da comunidade de morcegos na área cárstica do Alto Ribeira - SP. Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade São Paulo, São Paulo.) and the sandstone caves in the Preservation Area of Corumbataí (Campanhã & Fowler, 1999CAMPANHÃ, R. A. & FOWLER, H. G. 1993. Roosting assemblages of bats in arenitic caves in remnant fragments of Atlantic Forest in Southeastern Brazil. Biotropica. 25:362-365.) it was found that they have very similar composition, although differing in the number of species. The assemblages of 36 caves so far inventoried probably belong to the same regional chiropterofauna, thus suggesting that cave lithology is not a determinant factor for bat assemblages taxonomic structure. One possible explanation for this similarity and also for the relatively high number of bat individuals captured in Gruta do Riacho Suberrâneo could be the fact that all these caves are located in remnants of the Atlantic Rainforest.

Bats from Gruta do Riacho Subterrâneo and its surroundings were classified into five trophic guilds with predominance of the frugivore guild, a fact that is corroborated in other studies that indicate that there is a predominance of this guild in the Neotropical Region (Sipinski & Reis 1995SIPINSKI, E. A. B. & REIS, N. R. 1995. Dados ecológicos dos quirópteros da Reserva Volta Velha, Itapoá, Santa Catarina, Brasil. Rev. Bras. Zool. 12:519-528., Ribeiro-Mello 2009RIBEIRO MELLO, M. A. 2009. Temporal variation in the organization of a Neotropical assemblage of leaf-nosed bats (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae). Acta Oecol. p.280-286., Stevens & Amarilha-Stevens 2012STEVENS, R. D. & AMARILLA-STEVENS, H. N. 2012. Seasonal environments, episodic density compensation and dynamics of structure of chiropteran frugivore guilds in Paraguayan Atlantic forest. Biodivers. Conserv. 21 (1): 267-279., Bobrowiec et al. 2014BOBROWIEC, P. E. D., ROSA, L. d. S., GAZARINI, J. & HAUGAASEN, T. 2014. Phyllostomid Bat Assemblage Structure in Amazonian Flooded and Unflooded Forests. Biotropica. 46:312-321., Lourenço et al. 2014LOURENÇO, E. C., GOMES, L. A. PINHEIRO, M. C. PATRÍCIO, P. M. P. & FAMADAS, K. M. 2014. Composition of bat assemblages (Mammalia: Chiroptera) in tropical riparian forests. Int. J.Zool. 31:361-369.). The predominance of frugivorous could, at least in part, be influenced by the sampling method used (mist nets) which is more effective for this guild, but less effective for insectivores due to their more refined echolocation system (Handley 1967HANDLEY JR, C. O. 1967. Bats of the canopy of an Amazonian forest. In Atas do Simpósio sobre a biota Amazonica, Rio de Janeiro: Conselho Nacional de Pesquisas. 5: 211-215., Trajano 1985TRAJANO, E. 1985. Ecologia de populações de morcegos cavernícolas em uma região cárstica do sudeste do Brasil, Curitiba, Brasil, Rev. Brasil. Zool. 2:55-320., Arita 1993ARITA, H.T. 1993. Rarity in neotropical bats: correlations with phylogeny, diet, and body mass. Ecological Applications. Ann Arbor. 3:506-517., Sipinski & Reis 1995SIPINSKI, E. A. B. & REIS, N. R. 1995. Dados ecológicos dos quirópteros da Reserva Volta Velha, Itapoá, Santa Catarina, Brasil. Rev. Bras. Zool. 12:519-528.).

Some species were rare being captured only once (Anoura geoffroyi, Micronycteris sp., Chiroderma doriae, Sturnira tildae and Eptesicus diminutus), which could be due to the rarity of the species themselves, which usually tend to form small colonies and also to travel long distances to obtain food (Stevens & Amarilla-Stevens 2011STEVENS, R. D. & AMARILLA-STEVENS, H. N. 2012. Seasonal environments, episodic density compensation and dynamics of structure of chiropteran frugivore guilds in Paraguayan Atlantic forest. Biodivers. Conserv. 21 (1): 267-279.). For instance, Micronycteris sp. live in small groups of six or less individuals (Emmons, 1990EMMONS, L.H. 1990. Neotropical Rainforest Mammals: A Field Guide. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, Ltd London.). Chiroderma doriae has not been found in the caves in the studies of Trajano (1985)TRAJANO, E. 1985. Ecologia de populações de morcegos cavernícolas em uma região cárstica do sudeste do Brasil, Curitiba, Brasil, Rev. Brasil. Zool. 2:55-320. and of Campanhã and Fowler (1999)CAMPANHÃ, R. A. & FOWLER, H. G. 1993. Roosting assemblages of bats in arenitic caves in remnant fragments of Atlantic Forest in Southeastern Brazil. Biotropica. 25:362-365., but it was recorded by Arnone (2008)ARNONE, I. S. 2008. Estudo da comunidade de morcegos na área cárstica do Alto Ribeira - SP. Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade São Paulo, São Paulo. in Vale do Ribeira caves, who captured only one individual in this study site. It also occurred in small numbers in a semi-deciduous forest in the Ecological Station of Caetetus, São Paulo state (Pedro et al. 2001PEDRO, W. A., PASSOS, F. C. & LIM, B. K. 2001. Morcegos (Chiroptera: Mammalia) da Estação Ecológica dos Caetetus, estado de São Paulo. Chirop. Neotrop. 7:136-140.).

2. Seasonality

The results of multiple linear regression analysis did not show significance for the correlations among abiotic variables and the abundance of bats captured along the year. On contrary, the multivariate canonical analysis showed a significant positive relationship between the relative humidity and bat abundances. In the case of multiple regression, the tested variables are redundant (relative humidty is influenced by pluviosity and air temperature), which probably caused a noise in the analysis. Certainly the pluviosity and air temperature (affecting the relative humidity) influence the bat abundances and the canonical analysis supported this.

Corroborating this idea, we observed that the lowest captures of bats occurred in October 2013 and September 2014, which correspond to the transition period between dry and rainy seasons at the studied site. Bat populations were affected by seasonality, since the greatest bat abundances occurred in the warm and rainy summer months: December 2013 and March 2014, although a high number of bats was also captured in June 2014. The population of Carollia perspicillata, the most abundant species in Gruta do Riacho Subterrâneo cave followed this pattern, also displayed by less abundant species, such as Sturnira lilium and Glossophaga soricina. These species belongs to the frugivorous and nectarivorous trophic guilds, that are directly dependent on flowers and fruit production, which in Atlantic Rainforest and Cerrado have pronounced seasonality (Morellato et al. 2000MORELLATO, L. P. C., TALORA, D. C., TAKAHASI, A., BENCKE, C. C., ROMERA, E. J. C. & ZIPARRO, U. B. 2000. Phenology of Atlantic Rain Forest Trees: A Comparative Study. Biotropica 32 (4b): 811-823.; Batalha et al. 2004BATALHA, M. C. M. & MARTINS, F. R. 2004. Reproductive Phenology of the Cerrado Plant Community in Emas National Park, Central Brazil. Aust. J. Bot. 52: 149-161.; Marques et al. 2007MARQUES, M C. M. & OLIVEIRA, P. E. A. M. 2008. Seasonal rhythms of seed rain and seedling emergence in two tropical rainforests in Southern Brazil. Plant Biology. 10:596-623.).

The different pattern observed for Desmodus rotundus, which showed high abundance along all the year (except for the last capture event in September 2014) is probably related to its hematophagous trophic guild, dependent only on the availability of mammals blood (as cattle and horses), its main food source, which is constant throughout the year in the region.

Stevens & Amarilla-Stevens (2011)STEVENS, R. D. & AMARILLA-STEVENS, H. N. 2012. Seasonal environments, episodic density compensation and dynamics of structure of chiropteran frugivore guilds in Paraguayan Atlantic forest. Biodivers. Conserv. 21 (1): 267-279. in a study on bats in the Atlantic Forest in Paraguay found that some species displayed greater population changes in abundance, which were more related with seasonality than others. For example, the species Artibeus lituratus had a decline of more than 30% of its population during the colder season, but other species such as Carollia perspicillata and Artibeus fimbriatus did not show significant population density changes. The pattern observed for the latter species is similar to that of Carollia perspicilata, in which there was no direct relationship between this species abundance and temperature changes. The species A. lituratus was also captured, but its extremely low abundance in Gruta do Riacho Subterrâneo, with only two captures during all study, does not allow inferences regarding seasonality. Also, Ribeiro-Mello (2009)RIBEIRO MELLO, M. A. 2009. Temporal variation in the organization of a Neotropical assemblage of leaf-nosed bats (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae). Acta Oecol. p.280-286. and Ortencio-Filho et al. (2010)ORTÊNCIO FILHO, H., REIS, N. R. & MINTE-VERA, C. V. 2010. Time and seasonal patterns of activity of phyllostomid in fragments of a stational semidecidual forest from the Upper Paraná River, Southern Brazil. Braz. J. Biol. p. 937-945. showed that changes in temperature throughout the year influences the structure of bat community, and that this can be associated with a change in the feeding sites due to the decrease in food availability in the local area. Similarly, in Gruta do Riacho Subterrâneo cave, the lowest abundances of bats in September 2014 were probably due to the lower food availability, since this was the driest period in this one year sampling.

Another environmental factor that can influence cave bat capture is the moonlight intensity. It was shown by Crespo et al. (1972)CRESPO, R. F., LINHART, S. B., BURNS, R. J. & MITCHELL, G. C. 1972. Foraging Behavior of the Common Vampire Bat Related to Moonlight. J. Mammal. 53:366-368. in Mexico that Desmodus rotundus, a haematophagous species, and by Morrison (1978MORRISON, D. W. 1978. Lunar Phobia in Neotropical Fruit Bat Artibeus jamaicensis (Chiroptera, Phyllostomidae). Anim. Behav. 26: 853-855., 1980)MORRISON, D. W. 1980. Foraging and day-roosting dynamics of canopy fruit bats in Panama. J. Mammal. 61: 20-29. that some frugivorous species in Panamá, Canal Zone, presented lunar phobia. In the present study there was no relationship between the number of bat captures and the moon light phases.

Conclusion

This study showed that Gruta do Riacho Subterrâneo cave is an important shelter for a rich assemblage of bats, including common and rare species. Althought the climatic variables tested had not shown a significance according to the multiple regression analysis, the changes in population abundances could be due the seasonality in food availability (corroborated by canonical analysis, considering the air relative humidity). The preservation of this cave is important and urgent to the maintenance of bat diversity in general, also contributing to the conservation of the chiropterofauna of São Paulo state.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) for the scholarship to the first author; to Programa de Pós-graduação em Ecologia e Recursos Naturais (PPGERN) for support to develop this work; to Mr. Marcus Lerger, the owner of the privaty property where the cave is located and to the great contribution of anonymous reviewers to this manuscript. We are also grateful to Ericson Igual for guiding us, providing images and information about the cave; to Grupo Pierre Martin de Espeleologia (GPME) for all informations about the cave and collaboration in our studies; to Marco A. P. L. Batalha for helping with the statistical analysis; to Ives Arnone, Leonardo Resende and Tamires Zepon for all the help in field samplings; to Ives Arnone for taxomomic helping about the bats; to Alexandre Kannebley, Bruno G. O. do Monte, Camile S. Fernandes, Jonas E. Gallão and Márcio Bolfarini for helping in laboratory and critics about the work; to Camile S. Fernandes for the help in constructing the maps; to Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio) for collection permit; to Eleonora Trajano for donation of part of bat collection from Brazilian caves to LES (Laboratório de Estudos Subterrâneos); to Odete Rocha for the detailed review and contribution to the work, including the English revision.

References

- AKAIKE, H. 1970. Statistical predictor identification. Ann. Inst. Stat. Math. v. 22 (1), p. 203-217.

- ARITA, H.T. 1993. Rarity in neotropical bats: correlations with phylogeny, diet, and body mass. Ecological Applications. Ann Arbor. 3:506-517.

- ARNONE, I. S. 2008. Estudo da comunidade de morcegos na área cárstica do Alto Ribeira - SP. Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade São Paulo, São Paulo.

- ARNONE, I. S. & PASSOS, F. C. 2007. Estrutura de comunidade da quiropterofauna (Mammalia, Chiroptera) do Parque Estadual de Campinhos, Paraná, Brasil. Rev. Bras. de Zool. 24: 573-581.

- AVILA-FLORES, R. & MEDELLÍN, R. A. 2004. Ecological, taxonomic, and physiological correlates of cave use by Mexican bats. J. Mammal, 85: 675-687.

- BATALHA, M. C. M. & MARTINS, F. R. 2004. Reproductive Phenology of the Cerrado Plant Community in Emas National Park, Central Brazil. Aust. J. Bot. 52: 149-161.

- BOBROWIEC, P. E. D., ROSA, L. d. S., GAZARINI, J. & HAUGAASEN, T. 2014. Phyllostomid Bat Assemblage Structure in Amazonian Flooded and Unflooded Forests. Biotropica. 46:312-321.

- BREDT, A., MAGALHÃES, E.D. & UIEDA, W. 1999. Morcegos cavernícolas da região do Distrito Federal, Centro-oeste do Brasil (Mammalia, Chiroptera). Rev. Bras. de Zool. 16:731-770.

- BRUNET, A. K. & MEDELLÍN, R. A. 2001. The species-area relationship in bat assemblages of tropical caves. J. Mammal, 82: 1114-1122.

- CAJAIBA, R. L. 2014. Morcegos (Mammalia, Chiroptera) em cavernas no município de Uruará, Pará, norte do Brasil. Bio. Amaz. 4: 81-86.

- CAMPANHÃ, R. A. & FOWLER, H. G. 1993. Roosting assemblages of bats in arenitic caves in remnant fragments of Atlantic Forest in Southeastern Brazil. Biotropica. 25:362-365.

- COLWELL, R. K. 2005. EstimateS: Statistical estimation of species richness and shared species from samples. Version 7.5.

- CRESPO, R. F., LINHART, S. B., BURNS, R. J. & MITCHELL, G. C. 1972. Foraging Behavior of the Common Vampire Bat Related to Moonlight. J. Mammal. 53:366-368.

- EMMONS, L.H. 1990. Neotropical Rainforest Mammals: A Field Guide. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, Ltd London.

- ESBÉRARD, C. E. 2007. Influência do ciclo lunar na captura de morcegos Phyllostomidae. Iheringia, sér. Zool. 97: 81-85.

- GARDNER, A. L. 2007. Mammals of South America, volume 1: marsupials, xenarthrans, shrews, and bats. University of Chicago Press.

- GNASPINI, P. & TRAJANO, E. 2000. Guano Communities in tropical caves. In Ecosystems of the World: Subterranean Ecosystems (D. C. CULVER, W. F. W HUMPHREYS & H WILKENS, Eds.). Elsevier. Amsterdam, The Netherlands, p.251 - 268.

- GRUPO PIERRE MARTIN DE ESPELEOLOGIA, 2014. http://www.gpme.org.br (last access 19/09/2014).

» http://www.gpme.org.br - GUIMARÃES, M. M. & FERREIRA, R. L. 2014. Morcegos cavernícolas do Brasil: novos registros e desafios para conservação. Revista Brasileira de Espeleologia. 2:1-33.

- HANDLEY JR, C. O. 1967. Bats of the canopy of an Amazonian forest. In Atas do Simpósio sobre a biota Amazonica, Rio de Janeiro: Conselho Nacional de Pesquisas. 5: 211-215.

- INMET. http://www.inmet.gov.br (last access 22/08/2014).

» http://www.inmet.gov.br - JUBERTHIE, C. 2000. The diversity of the karstic and pseudokarstic hypogean habitats in the world. In Ecosystems of the World: Subterranean Ecosystems (H. Wilkens, D.C. Culver & W.F. Humphreys, Eds). Elsevier. Amsterdam, The Netherlands, p.17-40.

- KOPPEN W. P. 1948. Climatologia, com um estudio de los climas de la tierra. México: Fundo de Cultura Econômica.

- KUNZ, T.H. 1982. Roosting Ecology of bats. In Ecology of bats (T.H. KUNZ, Ed). New York, Plenum Press, p. 1-55.

- KUNZ, T. H. & LUMSDEN, L. F. 2003. Ecology of cavity and foliage roosting bats. In Bat Ecology (KUNZ, T. H & FENTON, M. B., Eds). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, p. 3-89.

- LOURENÇO, E. C., GOMES, L. A. PINHEIRO, M. C. PATRÍCIO, P. M. P. & FAMADAS, K. M. 2014. Composition of bat assemblages (Mammalia: Chiroptera) in tropical riparian forests. Int. J.Zool. 31:361-369.

- MARQUES, M C. M. & OLIVEIRA, P. E. A. M. 2008. Seasonal rhythms of seed rain and seedling emergence in two tropical rainforests in Southern Brazil. Plant Biology. 10:596-623.

- MORELLATO, L. P. C., TALORA, D. C., TAKAHASI, A., BENCKE, C. C., ROMERA, E. J. C. & ZIPARRO, U. B. 2000. Phenology of Atlantic Rain Forest Trees: A Comparative Study. Biotropica 32 (4b): 811-823.

- MORRISON, D. W. 1978. Lunar Phobia in Neotropical Fruit Bat Artibeus jamaicensis (Chiroptera, Phyllostomidae). Anim. Behav. 26: 853-855.

- MORRISON, D. W. 1980. Foraging and day-roosting dynamics of canopy fruit bats in Panama. J. Mammal. 61: 20-29.

- NOGUEIRA, M. R., LIMA, I. P. MORATELLI, R. CUNHA TAVARES, V. GREGORIN, R. & PERACCHI, A. L. 2014. Checklist of Brazilian bats, with comments on original records. Check List. p. 808-821.

- ORTÊNCIO FILHO, H., REIS, N. R. & MINTE-VERA, C. V. 2010. Time and seasonal patterns of activity of phyllostomid in fragments of a stational semidecidual forest from the Upper Paraná River, Southern Brazil. Braz. J. Biol. p. 937-945.

- PAGLIA, A. P., FONSECA, G. D., RYLANDS, A. B., HERRMANN, G., AGUIAR, L. M. S., CHIARELLO, A. G. & PATTON, J. L. 2012. Lista anotada dos mamíferos do Brasil. Occasional Papers in Conservation Biology. 6:1-76.

- PEDRO, W. A., PASSOS, F. C. & LIM, B. K. 2001. Morcegos (Chiroptera: Mammalia) da Estação Ecológica dos Caetetus, estado de São Paulo. Chirop. Neotrop. 7:136-140.

- R DEVELOPMENT CORE TEAM R. 2011. a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna.

- REIS, N. R., PERACCHI, A. L., PERACCHI, A. L. & SHIBATTA, O. A. 2013. Morcegos do Brasil. Guia de Campo. Ed. Technical Books. Brasil.

- REIS, N. R., PERACCHI, A. L., MULLER, M. F., BASTOS, E. A. & SOARES, E. S. 1995. Quirópteros do Parque Estadual Morro do Diabo, Sao Paulo Brasil (Mammalia: Chiroptera). Rev. Bras. Biol. 56:87-92.

- RIBEIRO MELLO, M. A. 2009. Temporal variation in the organization of a Neotropical assemblage of leaf-nosed bats (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae). Acta Oecol. p.280-286.

- RIZZINI, C. T. 1997. Tratado de Fitogeografia do Brasil. Âmbito Cultural Edições Ltda, Rio de Janeiro. Brasil.

- ROMANÍ, R. V., SANJURJO SANCHEZ, J. J., RODRÍGUEZ, M. & MOSQUERA, F. D. 2010. Speleothem development and biological activity in granite cavities. Geomorphologie: relief, processes, environment. 4: 337-346.

- SBRAGIA, I. A. & CARDOSO, A. 2008. Quiropterofauna (Mammalia: Chiroptera) cavernícola da Chapada Diamantina, Bahia, Brasil. Chirop. Neotrop. 14:360-365.

- SIPINSKI, E. A. B. & REIS, N. R. 1995. Dados ecológicos dos quirópteros da Reserva Volta Velha, Itapoá, Santa Catarina, Brasil. Rev. Bras. Zool. 12:519-528.

- STEVENS, R. D. 2013. Gradients of Bat Diversity in Atlantic Forest of South America: Environmental Seasonality, Sampling Effort and Spatial Autocorrelation. Biotropica. 45:764-770.

- STEVENS, R. D. & AMARILLA-STEVENS, H. N. 2012. Seasonal environments, episodic density compensation and dynamics of structure of chiropteran frugivore guilds in Paraguayan Atlantic forest. Biodivers. Conserv. 21 (1): 267-279.

- STRAUBE, F.C. & BIANCONI, G. V. 2002. Sobre a grandeza e a unidade utilizada para estimar esforço de captura com utilização de redes-de-neblina. Chirop. Neotrop. 8:150-152.

- TRAJANO, E. 1985. Ecologia de populações de morcegos cavernícolas em uma região cárstica do sudeste do Brasil, Curitiba, Brasil, Rev. Brasil. Zool. 2:55-320.

- TRAJANO E, 2012. Ecological classification of subterranean organisms. In Encyclopedia of Caves (White W.B. & Culver D. C, Eds). Amsterdam: Elsevier. p. 275-277.

- TWIDALE, C. R. & BOURNE, J. A. 2008. Caves in granitic rocks: types, terminology and origins. Cadernos do Laboratorio Xeolóxico de Laxe: Revista de xeoloxía galega e do hercínico peninsular. 33:35-57.

- VIZZOTO, L.D. & TADDEI, V. A. 1973. Chave para determinação de quirópteros brasileiros. São José do Rio Preto, gráfica Francal.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

2016

History

-

Received

14 Apr 2015 -

Reviewed

25 July 2016 -

Accepted

17 Aug 2016

Source:

Source:  Author: Ives Arnone

Author: Ives Arnone