Abstract

Purpose

Many adverse effects have been associated with abuse of anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS), including disorders of the urogenital tract. The objective of this study is to analyze the morphological modifications in the prostate ventral lobe of pubertal and adult rats chronically treated with AAS, using morphometric methods.

Materials and Methods: We studied 39 male Wistar rats weighing between 400 g and 550 g. The rats were divided into four groups: (a) control rats, with 105 days of age (C105) (n = 7); (b) control rats with 65 days of age (C65) (n = 9), injected only with the vehicle (peanut oil); (c) treated rats, with 105 days of age (T105) (n = 10) and (d) treated rats with 65 days of age (T65) (n = 13). The treated rats were injected with nandrolone decanoate at a dose of 10 mg.Kg-1 body weight. The steroid hormone and the vehicle were administered by intramuscular injection once a week for eight weeks. The rats were killed at 161 days of age (C105 and T105) and 121 days of age (C65 and T65) and the ventral prostate lobe was dissected and processed for histology. The height of the acinar epithelium, the surface densities of the lumen, epithelium and stroma were observed with X400 magnification using an Olympus light microscope coupled to a Sony CCD video camera, and the images transferred to a Sony monitor KX14-CP1. The selected histological areas were then quantified using the M42 test-grid system on the digitized fields. The data were analyzed with the Graphpad software. To compare the quantitative data in both groups (controls and treated) and the outcomes, Student's t-test was used (p < 0.05 was considered significant).

Results: The weight (p < 0.001) and volume (p = 0.004) of the prostate ventral lobe showed differences between C65 and T65 groups and between C105 and T105 groups. The epithelium height showed no difference between groups C65 and T65 (p = 0.8509), but the T105 group showed an increase of 32% compared to C105 (p = 0.0089). Concerning the lumen, surface density presented no difference between C65 and T65 (p = 0.9031) and a decrease of 19% for T105 compared to C105 (p = 0.0061). There was no difference in epithelium surface density between C65 and T65 (p = 0.7375), but it was 51% higher (p = 0.0065) in T105 compared with C105. Regarding stroma surface density, there were no differences between C65 and T65 or between C105 and T105. Finally, there was no difference in collagen pattern between C105 and T105, but T65 showed a predominance of collagen fibers compared to C65.

Conclusion: The use of anabolic androgenic steroids in rats promotes structural changes in the prostate. We observed structural changes in the weight, volume and epithelium height of the prostate ventral lobe and a predominance of collagen fibers.

Prostate; Anabolic Agents; Nandrolone; Image Cytometry

INTRODUCTION

Anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS) are widely used by professional and amateur athletes to improve athletic performance, appearance and muscle mass. However, many adverse effects have been associated with AAS abuse, including disorders of the urogenital tract (11. Lucía A, Chicharro JL, Pérez M, Serratosa L, Bandrés F, Legido JC: Reproductive function in male endurance athletes: sperm analysisand hormonal profile. J Appl Physiol. 1996; 81: 2627-36.). Abuse of anabolic-androgenic steroids may be an etiological factor in male infertility among recreational power athletes. Anabolic-androgenic steroids and endurance exercise can also induce some subclinical alterations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (H-P-G) axis (11. Lucía A, Chicharro JL, Pérez M, Serratosa L, Bandrés F, Legido JC: Reproductive function in male endurance athletes: sperm analysisand hormonal profile. J Appl Physiol. 1996; 81: 2627-36.,22. Feinberg MJ, Lumia AR, McGinnis MY: The effect of anabolic-androgenic steroids on sexual behavior and reproductive tissues in male rats. Physiol Behav. 1997; 62: 23-30.).

Testicular changes resulting from AAS use are well documented in the literature (33. Noorafshan A, Karbalay-Doust S, Ardekani FM: High doses of nandrolone decanoate reduce volume of testis and length of seminiferous tubules in rats. APMIS. 2005; 113: 122-5.). High doses of nandrolone decanoate reduce the volume of the testis and length of seminiferous tubules in rats (44. Shokri S, Aitken RJ, Abdolvahhabi M, Abolhasani F, Ghasemi FM, Kashani I, et al.: Exercise and supraphysiological dose of nandrolone decanoate increase apoptosis in spermatogenic cells. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010; 106: 324-30.). But studies of the structural changes in the prostate after AAS are scarce in the literature (55. Karbalay-Doust S, Noorafshan A: Stereological study of the effects of nandrolone decanoate on the rat prostate. Micron. 2006; 37: 617-23.).

An experimental study with rats demonstrated that changes in the serum levels of testosterone can cause morphological alterations in prostate tissue (66. Justulin LA Jr, Ureshino RP, Zanoni M, Felisbino SL: Differential proliferative response of the ventral prostate and seminal vesicle to testosterone replacement. Cell Biol Int. 2006; 30: 354-64.). The administration of exogenous androgenic-anabolic steroids has been demonstrated to have profound effects on the human prostate gland, including an increase in prostatic volume, reduction of urine flow rate and alteration in voiding patterns (77. Wemyss-Holden SA, Hamdy FC, Hastie KJ: Steroid abuse in athletes, prostatic enlargement and bladder outflow obstruction–is there a relationship? Br J Urol. 1994; 74: 476-8.).

This study aimed to assess the morphological modifications in the prostate ventral lobe of pubertal and adult rats chronically treated with supra-physiological doses of AAS, using morphometric methods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We studied 39 male Wistar rats weighing between 400 g and 550 g. The rats were kept in a room with controlled temperature (25 ± 1 °C) and with an artificial dark-light cycle (lights on from 7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m.), with four animals per standard rodent box. They were fed standard rat food and water ad libitum. All experiments were performed in accordance with Brazilian laws for scientific use of animals, and the project was approved by the local ethical committee.

The rats were divided into four groups: (A) control rats, with 105 days of age (C105) (n = 7); (B) control rats with 65 days of age (C65) (n = 9) injected only with the vehicle (peanut oil); (C) treated rats, with 105 days of age (T105) (n = 10) and (D) treated rats with 65 days of age (T65) (n = 13).

The treated rats (T65 and T105) were injected with nandrolone decanoate at a dose of 10 mg.Kg–1 body weight while the control groups (C65 and C105) received injections of 90% peanut oil (diluted in benzoic alcohol) as a vehicle (88. Fortunato RS, Marassi MP, Chaves EA, Nascimento JH, Rosenthal D, Carvalho DP: Chronic administration of anabolic androgenic steroid alters murine thyroid function. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006; 38: 256-61.). Both the steroid hormone and vehicle were administered by intramuscular injection (at the posterior musculature of the pelvic limb) once a week for eight weeks. This treatment protocol was established to simulate a commonly used protocol in humans during puberty or at early adult age, as previously published elsewhere (88. Fortunato RS, Marassi MP, Chaves EA, Nascimento JH, Rosenthal D, Carvalho DP: Chronic administration of anabolic androgenic steroid alters murine thyroid function. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006; 38: 256-61.).

The rats were killed by anesthetic overdose (intraperitoneal thiopental injection) at 161 days of age (C105 and T105) and 121 days of age (C65 and T65), and the ventral lobe of the prostate was dissected and its weight (in grams) and volume (in cubic centimeters) were estimated (99. Scherle W: A simple method for volumetry of organs in quantitative stereology. Mikroskopie. 1970; 26: 57-60.).

After the measurements, each prostate was processed for histology. Briefly, the prostate was carefully removed and fixed in 10% buffered formalin. Then each organ was dehydrated in crescent concentrations of ethanol baths and routinely processed for paraffin embedding. Non-serial (5 µm thick) sections were obtained at 200 µm intervals. The sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE) to assess the integrity of the tissue and with Picrosirius Red to identify different collagen types.

All selected fields were photographed with an Olympus DP70 camera coupled to an Olympus BX51 microscope. For the analysis of sections stained with HE, version 1.43 of the Image J software was used (NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, USA). The height of the acinar epithelium was measured in micrometers with the “straight line” tool of the program in micrometers in photomicrographs with 400x magnification (Figure-1A). The surface densities of the lumen, epithelium and stroma were estimated by the point intercepts method. Briefly, a grid of 100 points was superimposed on magnified images with the “grid” tool and each intercepted structure was quantified with the “cell counter” tool. (Figure-1B) (1010. Gundersen HJ, Bendtsen TF, Korbo L, Marcussen N, Møller A, Nielsen K, et al.: Some new, simple and efficient stereological methods and their use in pathological research and diagnosis. APMIS. 1988; 96: 379-94.). For each morphometric parameter, the animal's mean was obtained after analyzing 250 measurements in at least 25 different fields.

Photomicrographs of the rat prostate ventral lobe showing the morphometric features. A) The height of the acinar epithelium (yellow) was measured in micrometers in photomicrographs of 400X magnification using the Image J software. HE X400. B) The surface density of ventral lobe prostate lumen, epithelium and stroma were estimated by the point intercepts method, with a grid of 100 points superimposed on magnified images using the Image J software. HE X400.

The collagen pattern was qualitatively analyzed by Picro-Sirius Red staining by observing the color of collagen fibers' birefringence under polarized light.

Means were statistically compared using the unpaired T-test (p < 0.05) with the Graph Pad Prism software (1111. Sokol RR, Rohlf FJ: In: Biometry, 3rd (ed.), New York: Freeman WH. 1995.).

RESULTS

The weight (p < 0.0001) and volume (p = 0.0004) of the prostate ventral lobe showed differences between groups C65 and T65 and between C105 and T105 (Figure-2).

Comparative graphs between prostate ventral lobe weight (g) and volume (cm3) of treated and control rats. Data expressed as mean and SD. p < 0.05. The analysis showed difference between C65 and T65 groups, as well as between C105 and T105 groups. Weight: p < 0.001 and volume: p = 0.0004.

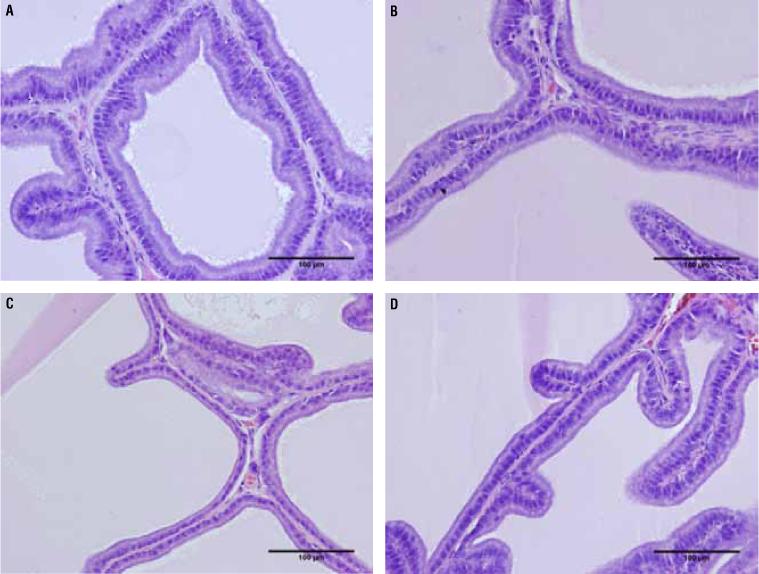

The epithelium height of the prostate ventral lobe showed no difference between groups C65 (20.85 ± 6.241) and T65 (22.16 ± 4.311) (p = 0.8509), but the T105 group (19.19 ± 2.765*) showed a 32% increase compared to C105 (14.11 ± 3.666) (p = 0.0089) (Figure-3 and Table 1).

Photomicrographs of the rat prostate ventral lobe group showing the epithelium height. The epithelium height showed no difference between groups C65 and T65, but the T105 group showed an increased of 32% compared to C105. A) Rat prostate ventral lobe of group C65. HE 400X. B) Rat prostate ventral lobe of group T65 HE 400X. C) Rat prostate ventral lobe of group C105 HE 400X. D) Rat prostate ventral lobe of group T105 HE 400X.

The table shows the numerical values with mean and standard deviation (SD) of the structures studied in the rat prostate ventral lobe treated with anabolic androgenic steroids. C105 - control rats, with 105 days of age; C65 - control rats with 65 days of age, injected only with the vehicle (peanut oil); T105 - treated rats, with 105 days of age and T65 - treated rats with 65 days of age.

Concerning lumen surface density of the prostate ventral lobe, there was no difference between C65 and T65 (p = 0.9031) and T105 presented a decrease of 19% compared to C105 (p = 0.0061). The epithelium surface density presented no difference between C65 and T65 (p = 0.7375), but was 51% higher (p = 0.0065) in T105 in comparison to C105. Regarding the stroma surface density, there were no differences between C65 and T65 and between C105 and T105 (Figure-4).

Comparative graphs between surface densities of the lumen, epithelium and stroma of control and treated rats. Data expressed as mean and SD. *p < 0.05. The lumen surface density presented no difference between C65 and T65 (p = 0.9031) and for T105 presented a decreased of 19% compared to C105 (p = 0.0061). The epithelium surface density presented no difference between C65 and T65 (p = 0.7375), but increased by 51% (p = 0.0065) in T105 in relation to C105. There were no differences in stroma surface density between C65 and T65 as well as between C105 and T105.

Table-1 reports the numerical values with mean and standard deviations of the structures studied.

The collagen pattern was qualitatively analyzed by Picro-Sirius Red staining. There was no difference between C105 and T105, but T65 showed a predominance of collagen fibers compared to C65 (Figure-5).

Photomicrographs showing prostate collagen of rat groups. A) Ventral prostate lobe of group T65. The photomicrograph shows predominance of collagen (red). Picrosirius Red 400X. B) Ventral lobe of group C65. Decreased presence can be observed of collagen (red). Picrosirius Red 400X.

DISCUSSION

Anabolic-androgenic steroids are synthetic derivatives of testosterone and are important pharmacologically for treatment of various medical conditions such as growth deficiency, some blood disorders and osteoporosis. Androgens play a crucial role in the development of male reproductive organs such as the epididymis, vas deferens, seminal vesicle, prostate and penis (66. Justulin LA Jr, Ureshino RP, Zanoni M, Felisbino SL: Differential proliferative response of the ventral prostate and seminal vesicle to testosterone replacement. Cell Biol Int. 2006; 30: 354-64.). The use of anabolic-androgenic steroids can lead to various body changes, including to the male genital system (1212. Montes GS: Structural biology of the fibres of the collagenous and elastic systems. Cell Biol Int. 1996; 20: 15-27.

13. Payne JR, Kotwinski PJ, Montgomery HE: Cardiac effects of anabolic steroids. Heart. 2004; 90: 473-5.-1414. Pereira-Junior PP, Chaves EA, Costa-E-Sousa RH, Masuda MO, de Carvalho AC, Nascimento JH: Cardiac autonomic dysfunction in rats chronically treated with anabolic steroid. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2006; 96: 487-94.).

Many studies have been published reporting structural changes of testes after AAS use (33. Noorafshan A, Karbalay-Doust S, Ardekani FM: High doses of nandrolone decanoate reduce volume of testis and length of seminiferous tubules in rats. APMIS. 2005; 113: 122-5.

4. Shokri S, Aitken RJ, Abdolvahhabi M, Abolhasani F, Ghasemi FM, Kashani I, et al.: Exercise and supraphysiological dose of nandrolone decanoate increase apoptosis in spermatogenic cells. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010; 106: 324-30.-55. Karbalay-Doust S, Noorafshan A: Stereological study of the effects of nandrolone decanoate on the rat prostate. Micron. 2006; 37: 617-23.). High doses of nandrolone decanoate reduce the testis volume and length of seminiferous tubules in rats (44. Shokri S, Aitken RJ, Abdolvahhabi M, Abolhasani F, Ghasemi FM, Kashani I, et al.: Exercise and supraphysiological dose of nandrolone decanoate increase apoptosis in spermatogenic cells. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010; 106: 324-30.). It is also clearly established that follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone from the pituitary gland have growth-promoting effects on testis development and that administration of exogenous androgens suppresses the serum luteinizing hormone and FSH level in humans and rats (33. Noorafshan A, Karbalay-Doust S, Ardekani FM: High doses of nandrolone decanoate reduce volume of testis and length of seminiferous tubules in rats. APMIS. 2005; 113: 122-5.).

The prostate is influenced by the serum levels of testosterone, and the use of AAS can also cause morphological changes in prostate tissue (66. Justulin LA Jr, Ureshino RP, Zanoni M, Felisbino SL: Differential proliferative response of the ventral prostate and seminal vesicle to testosterone replacement. Cell Biol Int. 2006; 30: 354-64.). These findings suggest that AAS can provoke functional changes and diseases of the prostate as well as lowered fertility.

Androgens are needed for puberty, male fertility and male sexual function. High levels of intra-testicular testosterone, secreted by Leydig cells, are necessary for spermatogenesis (1515. Shahidi NT: A review of the chemistry, biological action, and clinical applications of anabolic-androgenic steroids. Clin Ther. 2001; 23: 1355-90.). Testosterone is a critical hormone for prostate development, growth and maintenance. The enzyme 5-alpha-reductase seems to play an important role by converting androgens into dihydrotestosterone, which acts in the cell nucleus of target organs, such as male accessory glands, skin and prostate. Prostatic morphogenesis is determined not genetically, but by exposure to androgens produced by the testes in the fetus (1616. Bruchovsky N, Lesser B, Van Doorn E, Craven S: Hormonal effects on cell proliferation in rat prostate. Vitam Horm. 1975; 33: 61-102.).

At the age of sexual maturity, the secretory activity of the epithelium and the differentiation of smooth muscles are also maintained by androgens. In the prostate, luminal and basal epithelium as well as stroma and smooth muscle cells express ARs at sexual development and hence are capable of mediating androgen's actions (1515. Shahidi NT: A review of the chemistry, biological action, and clinical applications of anabolic-androgenic steroids. Clin Ther. 2001; 23: 1355-90.

16. Bruchovsky N, Lesser B, Van Doorn E, Craven S: Hormonal effects on cell proliferation in rat prostate. Vitam Horm. 1975; 33: 61-102.

17. Bronson FH, Matherne CM: Exposure to anabolic-androgenic steroids shortens life span of male mice. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997; 29: 615-9.-1818. Clark AS, Harrold EV, Fast AS: Anabolic-androgenic steroid effects on the sexual behavior of intact male rats. Horm Behav. 1997; 31: 35-46.). Thus, in response to androgens, prostate cells interact in an autocrine-paracrine way, influencing various aspects of the growth of this gland in normal and diseased states (1616. Bruchovsky N, Lesser B, Van Doorn E, Craven S: Hormonal effects on cell proliferation in rat prostate. Vitam Horm. 1975; 33: 61-102.

17. Bronson FH, Matherne CM: Exposure to anabolic-androgenic steroids shortens life span of male mice. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997; 29: 615-9.-1818. Clark AS, Harrold EV, Fast AS: Anabolic-androgenic steroid effects on the sexual behavior of intact male rats. Horm Behav. 1997; 31: 35-46.).

Several studies have shown that the prostate undergoes more marked alterations in epithelial and stromal compartments after hormonal and surgical ablation. These procedures lead to a decrease in glandular function, with consequent declines in epithelium thickness and stromal volume (22. Feinberg MJ, Lumia AR, McGinnis MY: The effect of anabolic-androgenic steroids on sexual behavior and reproductive tissues in male rats. Physiol Behav. 1997; 62: 23-30.,1616. Bruchovsky N, Lesser B, Van Doorn E, Craven S: Hormonal effects on cell proliferation in rat prostate. Vitam Horm. 1975; 33: 61-102.).

The rodent prostate has a complex structure, consisting of a ventral prostate (VP), lateral prostate (LP) and anterior prostate or coagulating gland (1919. Hayashi N, Sugimura Y, Kawamura J, Donjacour AA, Cunha GR: Morphological and functional heterogeneity in the rat prostatic gland. Biol Reprod. 1991; 45: 308-21.). The ventral lobe is one of the main targets of the action of androgens in the prostate, the reason it is widely used in experiments regarding hormones (1616. Bruchovsky N, Lesser B, Van Doorn E, Craven S: Hormonal effects on cell proliferation in rat prostate. Vitam Horm. 1975; 33: 61-102.). Besides this, the ventral prostate has only a small quantity of epithelial folds, unlike the other prostate lobes in rats (2020. Roy-Burman P, Wu H, Powell WC, Hagenkord J, Cohen MB: Genetically defined mouse models that mimic natural aspects of human prostate cancer development. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2004; 11: 225-54.). For this reason, we decided to evaluate the morphology of the ventral lobe instead of the others.

A recent study investigated the structural alterations of the rat prostate after treatment with AAS for 14 weeks in animals weighing between 250 and 300 g (55. Karbalay-Doust S, Noorafshan A: Stereological study of the effects of nandrolone decanoate on the rat prostate. Micron. 2006; 37: 617-23.). The authors concluded that nandrolone decanoate causes atrophic changes in the components of the rat prostate. In our study, we observed that the use of AAS causes changes in the prostate morphology after briefer treatment (8 weeks), and that the changes are less severe in pubertal animals and more severe in adults.

Although we used a similar method, our results were quite different from those of Karbalay-Dust (55. Karbalay-Doust S, Noorafshan A: Stereological study of the effects of nandrolone decanoate on the rat prostate. Micron. 2006; 37: 617-23.). The height of the epithelium increased 32% in the groups of 105-day-old animals, a parameter not altered in the previous study. That study also found that the use of AAS diminished the density of the lumen, epithelium and stroma. In contrast, we analyzed the surface density and found that the lumen diminishes, the epithelium enlarges and the stroma does not change after treatment with AAS.

A recent in vitro study investigated the prostate after administration of themethyl-1-testosterone (M1T) (2121. Parr MK, Blatt C, Zierau O, Hess C, Gütschow M, Fusshöller G, et al.: Endocrine characterization of the designer steroid methyl-1-testosterone: investigations on tissue-specific anabolic-androgenicpotency, side effects, and metabolism. Endocrinology. 2011; 152: 4718-28.). The authors showed that M1T had high potency to stimulate the tissue weight of the prostate as well as the seminal vesicle (2121. Parr MK, Blatt C, Zierau O, Hess C, Gütschow M, Fusshöller G, et al.: Endocrine characterization of the designer steroid methyl-1-testosterone: investigations on tissue-specific anabolic-androgenicpotency, side effects, and metabolism. Endocrinology. 2011; 152: 4718-28.). That paper shows stimulation of proliferation of the prostate epithelium, which is the most androgen-sensitive part of this organ. The prostate epithelium is an extremely sensitive marker for anabolic activity. In our sample, we confirmed this anabolic activity in the prostate after administration of AAS. The epithelium height of the prostate ventral lobe in the T105 group showed a 32% increase compared to the C105 group. In another study in rats, the authors showed that accessory sex gland weights were increased by androgen treatment in all groups compared with castrates (2222. Attardi BJ, Marck BT, Matsumoto AM, Koduri S, Hild SA: Long-term effects of dimethandrolone 17β-undecanoate and 11β-methyl-19-nortestosterone 17β-dodecylcarbonate on bodycomposition, bone mineral density, serum gonadotropins, and androgenic/anabolic activity in castrated male rats. J Androl. 2011; 32: 183-92.).

One of the limitations of this study is the testosterone analysis. We performed serum testosterone analysis by chemiluminescence but since the kit was not specific for rats, the results were not accurate. For instance, in the control groups some rats had undetectable (lower) levels while others had abnormally higher levels (> 14.0 ng/mL, when normal levels are around 1.4 ng/mL). The results from treated animals were equally aberrant. Therefore, we disregarded this analysis.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the use of anabolic-androgenic steroids in rats promotes structural changes in the prostate. We observed changes in weight, volume and epithelium height of the ventral lobe and a predominance of collagen fibers. These alterations seem to be more severe in adult animals.

Supported by grants from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPQ) and the Rio de Janeiro State Research Foundation (FAPERJ)

REFERENCES

-

1Lucía A, Chicharro JL, Pérez M, Serratosa L, Bandrés F, Legido JC: Reproductive function in male endurance athletes: sperm analysisand hormonal profile. J Appl Physiol. 1996; 81: 2627-36.

-

2Feinberg MJ, Lumia AR, McGinnis MY: The effect of anabolic-androgenic steroids on sexual behavior and reproductive tissues in male rats. Physiol Behav. 1997; 62: 23-30.

-

3Noorafshan A, Karbalay-Doust S, Ardekani FM: High doses of nandrolone decanoate reduce volume of testis and length of seminiferous tubules in rats. APMIS. 2005; 113: 122-5.

-

4Shokri S, Aitken RJ, Abdolvahhabi M, Abolhasani F, Ghasemi FM, Kashani I, et al.: Exercise and supraphysiological dose of nandrolone decanoate increase apoptosis in spermatogenic cells. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010; 106: 324-30.

-

5Karbalay-Doust S, Noorafshan A: Stereological study of the effects of nandrolone decanoate on the rat prostate. Micron. 2006; 37: 617-23.

-

6Justulin LA Jr, Ureshino RP, Zanoni M, Felisbino SL: Differential proliferative response of the ventral prostate and seminal vesicle to testosterone replacement. Cell Biol Int. 2006; 30: 354-64.

-

7Wemyss-Holden SA, Hamdy FC, Hastie KJ: Steroid abuse in athletes, prostatic enlargement and bladder outflow obstruction–is there a relationship? Br J Urol. 1994; 74: 476-8.

-

8Fortunato RS, Marassi MP, Chaves EA, Nascimento JH, Rosenthal D, Carvalho DP: Chronic administration of anabolic androgenic steroid alters murine thyroid function. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006; 38: 256-61.

-

9Scherle W: A simple method for volumetry of organs in quantitative stereology. Mikroskopie. 1970; 26: 57-60.

-

10Gundersen HJ, Bendtsen TF, Korbo L, Marcussen N, Møller A, Nielsen K, et al.: Some new, simple and efficient stereological methods and their use in pathological research and diagnosis. APMIS. 1988; 96: 379-94.

-

11Sokol RR, Rohlf FJ: In: Biometry, 3rd (ed.), New York: Freeman WH. 1995.

-

12Montes GS: Structural biology of the fibres of the collagenous and elastic systems. Cell Biol Int. 1996; 20: 15-27.

-

13Payne JR, Kotwinski PJ, Montgomery HE: Cardiac effects of anabolic steroids. Heart. 2004; 90: 473-5.

-

14Pereira-Junior PP, Chaves EA, Costa-E-Sousa RH, Masuda MO, de Carvalho AC, Nascimento JH: Cardiac autonomic dysfunction in rats chronically treated with anabolic steroid. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2006; 96: 487-94.

-

15Shahidi NT: A review of the chemistry, biological action, and clinical applications of anabolic-androgenic steroids. Clin Ther. 2001; 23: 1355-90.

-

16Bruchovsky N, Lesser B, Van Doorn E, Craven S: Hormonal effects on cell proliferation in rat prostate. Vitam Horm. 1975; 33: 61-102.

-

17Bronson FH, Matherne CM: Exposure to anabolic-androgenic steroids shortens life span of male mice. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997; 29: 615-9.

-

18Clark AS, Harrold EV, Fast AS: Anabolic-androgenic steroid effects on the sexual behavior of intact male rats. Horm Behav. 1997; 31: 35-46.

-

19Hayashi N, Sugimura Y, Kawamura J, Donjacour AA, Cunha GR: Morphological and functional heterogeneity in the rat prostatic gland. Biol Reprod. 1991; 45: 308-21.

-

20Roy-Burman P, Wu H, Powell WC, Hagenkord J, Cohen MB: Genetically defined mouse models that mimic natural aspects of human prostate cancer development. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2004; 11: 225-54.

-

21Parr MK, Blatt C, Zierau O, Hess C, Gütschow M, Fusshöller G, et al.: Endocrine characterization of the designer steroid methyl-1-testosterone: investigations on tissue-specific anabolic-androgenicpotency, side effects, and metabolism. Endocrinology. 2011; 152: 4718-28.

-

22Attardi BJ, Marck BT, Matsumoto AM, Koduri S, Hild SA: Long-term effects of dimethandrolone 17β-undecanoate and 11β-methyl-19-nortestosterone 17β-dodecylcarbonate on bodycomposition, bone mineral density, serum gonadotropins, and androgenic/anabolic activity in castrated male rats. J Androl. 2011; 32: 183-92.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

Sep-Oct 2013

History

-

Received

15 Apr 2013 -

Accepted

25 July 2013