ABSTRACT

Objective

To determine and discuss cancer mortality rates in southern Brazil between 1988 and 2012.

Methods

This was a critical review of literature based on analysis of data concerning incidence and mortality of prostate cancer, breast cancer, bronchial and lung cancer, and uterine and ovarian cancer. Data were collected from the online database of the Brazil Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva.

Results

The southern Brazil is the leading region of cancer incidence and mortality. Data on the cancer profile of this population are scarce especially in the States of Santa Catarina and Paraná. We observed inconsistency between data from hospital registers and death recorded.

Conclusion

Both cancer incidence and the mortality are high in Brazil. In addition, Brazil has great numbers of registers and deaths for cancer compared to worldwide rates. Regional risk factors might explain the high cancer rates.

Keywords

Neoplasms/mortality; Hospital records; Potential years of life lost; Brazil

RESUMO

Objetivo

Investigar e discutir os indicadores de mortalidade por câncer na Região Sul do Brasil entre 1988 e 2012.

Métodos

Revisão crítica da literatura baseada na análise de dados referentes às estimativas de incidência e mortalidade dos cânceres de próstata, mama feminina, brônquios e pulmões, colo de útero e ovário, realizada por meio de consulta na base de dados online do Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva.

Resultados

A Região Sul lidera no país a incidência e a mortalidade das neoplasias estudadas. Há escassez de dados sobre o perfil do câncer nesta população, especialmente nos Estados de Santa Catarina e Paraná. Notou-se, ainda, incoerência entre os dados de registros hospitalares e registros de óbito no período estudado.

Conclusão

Tanto a incidência quanto a mortalidade decorrentes dos cânceres estudados ainda são muito elevadas no Brasil, com significante número de registros da doença e de óbitos, quando comparado às taxas mundiais. Fatores de risco regionais podem explicar as elevadas taxas.

Descritores

Neoplasias/mortalidade; Registros hospitalares; Anos potenciais de vida perdidos; Brasil

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is one of the leading causes of death worldwide.(11. World Health Organization (WHO). Cancer [Internet]. [cited 2017 Sep 21]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheet...

) From 2014 to 2015 Brazil had estimated more than 500,000 new cases of cancer,(22. Instituto Nacional de Câncer José de Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA). Estimativa 2014 – Incidência de Câncer no Brasil. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2014;60(1):63-4.) which placed the country among those with the highest cancer incidence in current days.(33. Stewart BW, Wild CP. World Cancer Report 2014. France: WHO Press; 2014.)

Although the growing efforts for early screening and diagnosis, the associated risk factors for development of this disease are strongly present in Brazilian population, particularly smoking, occidental diet, obesity and sedentarism.(44. McLean RC, Logue J. The individual and combined effects of obesity and type 2 diabetes on cancer predisposition and survival. Curr Nutr Rep. 2015;4(1):22-32.)

A high cancer incidence in seen in most-populous and industrialized regions of the country; the south region. This region concentrates the highest incidence of neoplasias, according to figure 1, and this fact might be associated with southern population longer life expectancy and healthy habits.(55. Barros SG, Ghisolfi ES, Luz LP, Barlem GG, Vidal RM, Wolff FH, et al. Mate (chimarrão) é consumido em alta temperatura por população sob risco para o carcinoma epidermóide de esôfago. Arq Gastroenterol. 2000;37(1):25-30.) This high number of cancer cases among southern population still a reflex of great number of diagnoses and, consequently, increase records in official databases.(66. Girianelli VR, Gamarra CJ, Azevedo e Silva G. Disparities in cervical and breast cancer mortality in Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2014;48(3):459-67.)

Estimated number of cancer cases selected by study in population of south Brazil in 2014. Data extracted from database of Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva.(22. Instituto Nacional de Câncer José de Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA). Estimativa 2014 – Incidência de Câncer no Brasil. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2014;60(1):63-4.) Data collected for lung cancer, cancer of the trachea, and bronchial cancer, estimated by sum of new cases among men and women

Although the high cancer incidence and mortality rates in south Brazil, few studies have discussed possible associated factors with this disease. Some neoplasias such as ovarian and breast cancer have a strong genetic predisposition among population in this region prevalent.(77. Ewald IP. Caracterização de um grupo de pacientes em risco para câncer de mama e ovário hereditários quanto a presença e frequência de rearranjos gênicos em BRCA [tese]. Porto Alegre: Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul; 2012.) In addition, southern population high fat diet and consumption of smoked products favor the development of obesity, one of the main factors that lead to development of cancer in the modern society.(88. Kolling FL, Santos JS. [The influence of nutritional risk factors in the development of breast cancer in outpatients from the countryside of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil]. Sci Med. 2009;19(3):115-21. Portuguese.) Such factors contribute significantly to development of clinicopathological cancers with worse prognosis that may impact cancer morbidity and mortality.

OBJECTIVE

To discuss the cancer issue in southern Brazil within the last 20 years based on information from the database of Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva particularly issues related with notification of this disease and mortality related to prostate cancer, breast cancer, bronchial and lung cancer, and uterine and ovarian cancer.

METHODS

This is a critical review on estimation analysis of incidence and indicators of mortality of prostate cancers, breast cancer, bronchial and lung cancer, uterine and ovarian cancer based on consultations of online database of National Cancer Institute José Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA – Instituto Nacional de Câncer). Number of hospital records and deaths for each topography and by States of Southern Region were obtained from online data of hospital-based cancer registry of INCA (1998-2012), and from INCA's mortality atlas (2001-2012). Such registers were selected to compose this study because they included information that enabled to evaluate quality of service provide the hospital network in Brazil.

In addition, we evaluated data related with crude and adjusted rates and number of years of potential life lost for cancer from INCA's mortality atlas using based on total of Brazil population available in census from 2010 (https://mortalidade.inca.gov.br/MortalidadeWeb/pages/Modelo01/consultar.xhtml;jsessionid=CA2C390AB43798B3880F4078A4345436). Adjusted mortality rate by age evaluates the number of deaths in each age range regarding total of deaths in south population and this rate was directly standardized by primary source consulted in order to reduce bias that age factor can add to studies on cancer. Proportional mortality data were used to illustrate amount of deaths in population affected by cancer in studied period and number of years of potential life lost as indicator of total sum of years lost for each death because of cancer. Such associated indicators enabled to measure impact of each cancer in the studied population within each year.

All database mentioned were searched within the INCA website.(22. Instituto Nacional de Câncer José de Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA). Estimativa 2014 – Incidência de Câncer no Brasil. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2014;60(1):63-4.) The values presented were obtained from those calculated by databases, using as reference the estimated southern Brazilian population for each year. Coefficients were also adjusted by age by database searched. To discuss results, we used published studies in PubMed and Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO).

RESULTS

Results obtained highlighted Southern Region as national leading region of cancer incidence and mortality from 1988 to 2012. This comparative analysis of number of hospital-register cancer between 2001 and 2012 for prostate cancer, breast cancer, bronchial and lung cancer, uterine and ovarian cancer showed expression values for Southern Region with special emphasizes to Rio Grande do Sul State, followed by Paraná and Santa Catarina (Table 1).

Hospital-registers and deaths for cancer according to primary site incidence and categorization by States

Prostate and breast cancer had higher incidence than number of deaths in Paraná and Rio Grande do Sul States. The same result was seen in Santa Catarina after 2004. In Southern Region, we also observed increase in registers of prostate cancer diagnosis, although this type of cancer did not show increase in mortality (Table 1).

Regarding bronchial and lung cancer, we observed an increase of number of hospital register and deaths, particularly in the State of Rio Grande do Sul. This was the leading State in number of deaths because of gynecologic cancers. The same result was seen in this State to the five cancer types analyzed.

Still, south region had the highest mortality rates for cancer. Table 2 shows that standardized world mortality rate was achieved and overpassed within the age 40 to 49 years, excepted to prostate cancer. Mortality rate increased gradually from 60 years of age, and higher indexes occurred among individuals aged 70 to 79 years (196.37/100,000) reaching 538.54/100,000 of those older than 80 years.

Mortality, crude, adjusted rates by cancer per age, world and Brazilian population from 2010 per 100,000 men and women, according to primary site of men and women incidence

For breast cancer, 91.3% of cases of mortality occurred after 50 years, achieving rate of 116 cases/100,000 in age range ≥80 years. In relation to bronchial and lung cancer, highest rates of mortality were observed after 60 years, reaching 264.24/100,00 in men aged 70 to 79 years and 281.79/100,000 in men aged over 80 years.

Still this rate was lower among women, and relationship between sexes was 3.1 men for each women.

To each uterine cancer, we observed higher number of deaths among those aged 40 to 49 years. From this age range, this rate (10.18/100,000) was double of standardized Brazilian rate (5.66/100,000) and world rate (5.27/100,000), reaching 22.32/100,000 in age of 80 years. Similar results can be seen in death rates due to ovarian cancer in which age range from 60 to 69 years had 26.06% of deaths (14.37/100,000). From the 40 years, death rate increased significantly compared with age 30 to 39 years (0.95/100,000).

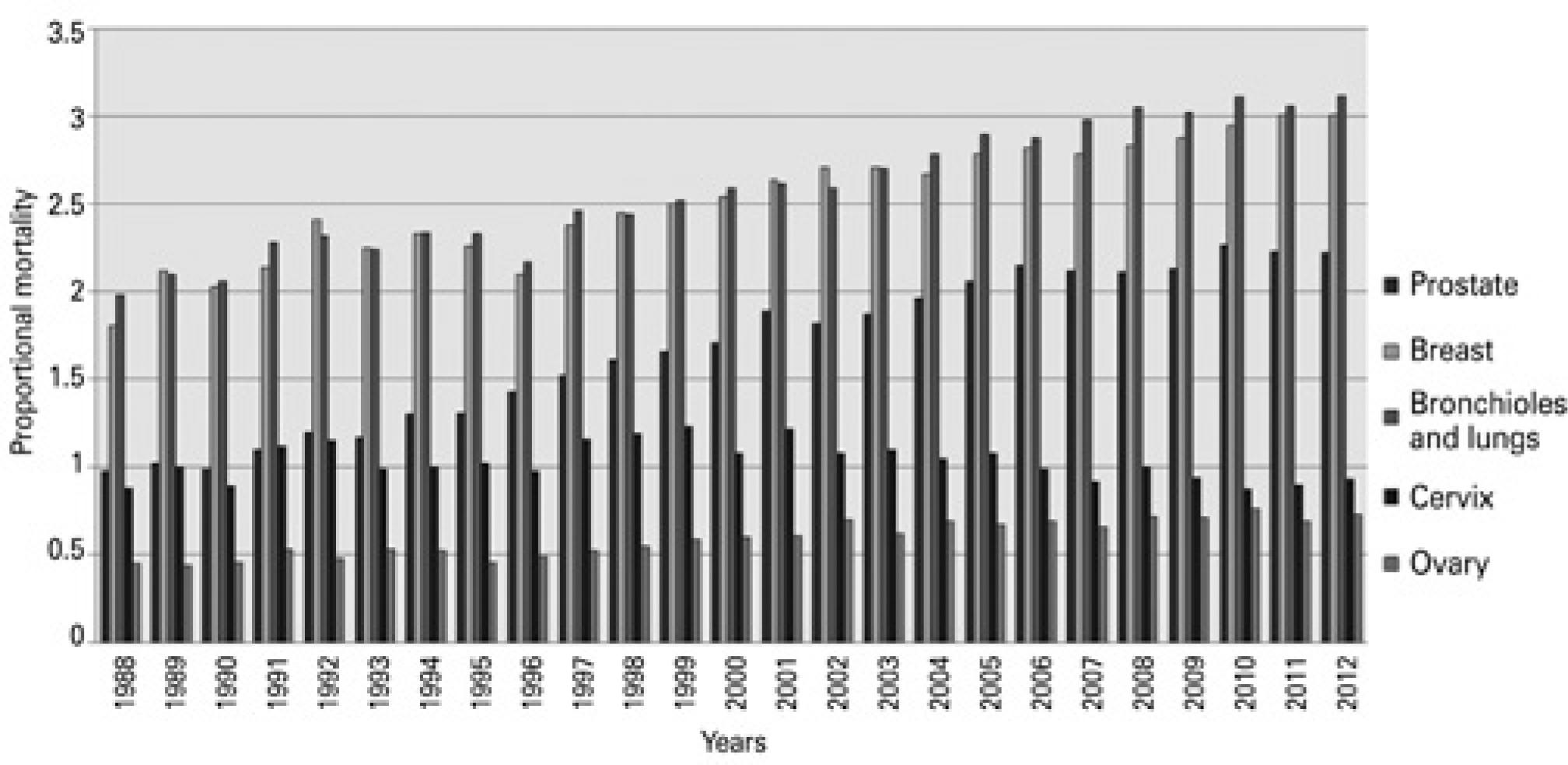

Non-adjusted proportional death rate (Figure 2) enabled to observe and analyze deaths of main cancers types (lung, breast, uterine, ovarian, and prostate) that occurred in south Brazil between 1988 and 2012. The association of data from Southern Region with hospital records showed that in 2003 a estimation of 4,980 prostate cancer cases occurred per 100,000 inhabitants in southern Brazil, however, the number found was 1,028. Although hospital register did not correspondent to incidence, the value obtained in hospital-based cancer register was lower than estimated. In 2012, however, the estimation by INCA was 9,490 new cases per each 100,000 inhabitants and, again, hospital registers showed a number about three times lower than expected, i.e 3,022 registers.

We observed a gradual increase of proportional mortality per breast cancer between 1988 to 2012. In case of bronchial and lung cancer death, there was an increase, with raising in rate from 1.98/100,000 in 1998 to 3.12/100,000 in 2012. Non-adjusted proportional mortality for uterine cancer had a decrease from 1.22% in 2001 to 0.93% in 2012. The non-adjusted proportional mortality rate for ovarian cancer showed an increase since 1996 compared with cancer death rate in Brazil.

Figure 3 shows mean number of years of potential life lost because for cancer from 1998 to 2012 per each 1,000 inhabitants in Southern Region population aged no older than 80 years old.

Mean potential years of life lost for cancer

Estimation for breast cancer, uterine and ovarian cancer that was calculated for each 1,000 women and, for lung and prostate cancer, for each 1,000 inhabitants of south region between 1998 and 2012 from premise that high limit would be 80 years. Data calculated based on Brazilian population of 2010.

Mean number of years of life lost by men and women diagnosed with bronchial and lung cancer appeared in all age ranges, and it was higher between 60 and 69 years, achieving 13.74 of potential years of life lost. In general, based on potential years of life lost indexes and potential years of life lost rate in relation to studied cancers, the prostate cancer revealed rate of 6.69, and for breast 9.08, bronchial and lung 13.74, uterine 3.49 and for ovarian cancer 1.9. Age range regarding number of deaths for prostate, bronchial and lung cancers was higher among those aged 60 to 69 years. Number of deaths for breast, uterine and ovarian cancer was higher among those aged 50 to 59 years. Women diagnosed with breast cancer in the analyzed period lost, on average, 9 years of life.

DISCUSSION

Data presented in this study enabled to affirm that south region concentrated the highest national incidence of hospital register for cancer with high mortality rate in the studied period. Among analyzed markers, hospital cancer registers used as basis for our study are important to measure relevance of this disease in public health because they represent assistances yearly for each type of cancer in one or more institutions and it can enable calculation of incidence of any cancer.(99. Brasil. Secretaria Nacional de Assistência à Saúde. Instituto Nacional de Câncer. Coordenação Nacional de Controle do Tabagismo, Prevenção e Vigilância do Câncer. Registros hospitalares de câncer: rotinas e procedimentos. Rio de Janeiro (RJ): Instituto Nacional do Câncer/MS; 2000.) Mortality rate by age that evaluate the number of deaths in each age range regarding total of deaths in a specific period and among population living in specific geographic area,(1010. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. DATASUS. Indicadores demográficos: mortalidade proporcional por idade [Internet]. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde [citado 2017 Set 21]. Disponível em: http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/idb2000/fqa07.htm

http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/idb2000...

) was higher compared with world rates. For this reason, it is important to highlight that prostate cancer, breast cancer, bronchial cancer, and lung cancer have higher mortality rates in Brazil, and high rate can be observed in south of the country. Aspects related to weakness of Brazilian system in cancer prevention, it diagnosis in advanced phase cases, population's habits and precarious life conditions, difficult to access health system and get screening(1111. Paiva CJ, Cesse EA. [Aspects related to delay in diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer in a hospital in Pernambuco]. Rev Bras cancerol. 2015;61(1):23-30. Portuguese.) can affect the observed numbers.

Southern Brazilian population has a good socioeconomic development profile that positively reflect prevention and early treatment of diseases.(1212. Wunsch Filho V, Moncau JE. Mortalidade por cancer no Brasil 1980-1995: padrões regionais e tendências temporais. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2002;48(3):250-7.) This aspects help to understand low crude mortality rate observed in data collected. Age seems to be the main risk factor for cancer because of increase in life expectation followed by increase of chronic-degenerative diseases such as cancer.(1313. Oliveira Júnior FJ, Cesse EA. [Morbi-mortality by cancer in Recife in the 90s]. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2005;51(3):201-8. Portuguese.)

Southern Region is highlighted because it presents better life expectations than the rest of the country throughout the years, and this represents an important fact to explain increased incidence of cancers registered in the study. This fact explain, e.g., the high incidence of diagnosed prostate cancer, once longevity constitutes an important risk factor for development of this cancer.(1414. Paiva EP, Motta MC, Griep RH. [Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the detection of prostate cancer]. Acta Paul Enferm. 2010;23(1):88-93. Portuguese.)

Cancers that were most common among men, we observed high number of prostate cancer records within this population in the studied period, although the predominance of European descent individuals. Southern Region has predominance of Caucasian population and prostate cancer has a higher incidence among African-descent individuals. This suggests that other regional factors, besides age, may influence high prevalence of this neoplasia in studied population with active investigation of prostate cancer by screening exams.(1515. Almeida JR, Pedrosa NL, Leite JB, Fleming TR, Carvalho VH, Cardoso AA. Marcadores tumorais: revisão de literatura. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2007;53(3):305-16.)

Despite high incidence and high mortality rates by prostate cancer are relatively low compared with other types of cancers,(1414. Paiva EP, Motta MC, Griep RH. [Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the detection of prostate cancer]. Acta Paul Enferm. 2010;23(1):88-93. Portuguese.) mainly because this entails a relatively aggressive cancer.(1616. Quinn M, Babb P. Patterns and trends in prostate cancer incidence, survival, prevalence and mortality. Part I: international comparisons. BJU Int. 2002;90(2):162-73. Review.)

In bronchial and lung cancer the high number of registers and deaths can be closed correlated with smoking, mainly because this region has the highest prevalence of smokers in the country.(1717. Instituto Nacional de Câncer José de Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA). Observatório da Política Nacional de Controle do Tabaco. Prevalência do Tabagismo [Internet]. Rio de Janeiro (RJ): Instituto Nacional de Câncer [citado 2015 out 30]. Disponível em: http://www2.inca.gov.br/wps/wcm/connect/observatorio_controle_tabaco/site/home/dados_numeros/prevalencia-de-tabagismo

http://www2.inca.gov.br/wps/wcm/connect/...

,1818. Fonseca LA, Eluf-Neto J, Wunsch Filho V. Tendências da mortalidade por câncer nas capitais dos estados do Brasil, 1980-2004. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2010;56(3):309-12.) This increase of mortality rate by bronchial and lung cancer is because of the growing number of women who smoke, and because of higher risk of development of different cancers.(1919. Malta DC, Moura L, Souza MF, Curado MP, Alencar AP, Alencar GP. Lung cancer, cancer of the trachea, and bronchial cancer: mortality trends in Brazil, 1980-2003. J Bras Pneumol. 2007;33(5):536-43.) Mortality profile observed in bronchial and lung cancer in older population can still be associated with smoking history,(1919. Malta DC, Moura L, Souza MF, Curado MP, Alencar AP, Alencar GP. Lung cancer, cancer of the trachea, and bronchial cancer: mortality trends in Brazil, 1980-2003. J Bras Pneumol. 2007;33(5):536-43.) once the incubation period of this pathology can last for 30 years.(2020. Wünsch Filho V, Mirra AP, López RV, Antunes LF. [Tobacco smoking and cancer in Brazil: evidence and prospects]. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2010;13(2):175-87. Portuguese.) The reduced tendency of death among younger men probably reflect national actions to reduce smoking rates in Brazil.

Regarding cancer among women, the prevalence of smoking in the region is still an important risk factor to increase incidence of gynecology cancers, such as uterine cancer.(22. Instituto Nacional de Câncer José de Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA). Estimativa 2014 – Incidência de Câncer no Brasil. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2014;60(1):63-4.) Reduction of non-adjusted mortality observed in this study between 1999 and 2001 could be for gradual broad of screening services as well as strengthening and qualification of basic care network within last 20 years.

Age of ovarian cancer diagnosis ranged from 42.7 to 48 years, whereas mean described for sporadic cases is closed to 61 years old. These findings suggest possible existence of family heritage about one in each 10 cases of women with ovarian cancer that present standard that gives susceptibility for early occurrence of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome.(2121. Alvarenga M, Cotta AC, Dufloth RM, Schmitt FC. [Hereditary cancer syndrome: pathologists contribution for diagnosis and evaluation o prophylactic surgical procedures]. J Bras Patol Med Lab. 2003;39(2):167-77. Portuguese.)

In this sense, we observed in Rio Grande do Sul a high prevalence of breast cancer among young women. In this situation, this neoplasia is presented as aggressive disease of difficult treatment,(2222. Anders CK, Johnson R, Litton J, Phillips M, Bleyer A. Breast cancer before age 40 years. Semin Oncol. 2009;36(3):237-49. Review.) which explain the high mortality rate observed after 50 years. Indeed, we observed that around 6% of southern population of metropolitan region have hereditary predisposition for breast cancer that commonly occurs in individuals younger 50 years and who present quite aggressive characteristics with high mortality rate.(2323. Garicochea B, Morelle A, Andrighetti AE, Cancella A, Bós A, Werutsky G. [Age as a prognostic fator in early breast cancer]. Rev Saude Publica. 2009;43(2):311-7. Portuguese.)

In addition, a study done by Cadaval Gonçalves et al., revealed that, between 1980 and 2005, Rio Grande do Sul had highest concentration in the country of death rates for breast cancer.(2424. Cadaval Gonçalves AT, Costa Jobim PF, Vanacor R, Nunes LN, Martins de Albuquerque I, Bozzetti MC. [Increase in breast cancer mortality in Southern Brazil from 1980 to 2002]. Cad Saude Publica. 2007;23(8):1785-90. Portuguese.) Therefore, the study suggested that morbidity and mortality of the disease is a true fact in this population and it has been associated with socioenvironmental facts such as low formal education level, chronic exposition to agriculture products and overweight.(2525. Melo WA, Souza LA, Zurita RC, Carvalho MD. [Factors associated in breast cancer mortality in northwest paranaense]. Rev Gestao Saude. 2003;2087-94. Portuguese.–2727. Matos JC, Pelloso SM, Carvalho MD. Prevalence of Risk Factors for Breast Neoplasm in the City of Maringá, Paraná State, Brazil. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2010;18(3):352-9.) The unclear data observed between incidence registers and number of deaths for cancer included in our study pointed out the need to standardize data register about cancer in Brazil.

Other indicators analyzed regarding mortality, the number of productive years of life lost, is an indicator that reflect total sum of years of potential life lost.(2828. Pereira MS, Ferreira LO, Silva GA, Lucio PS. [Breast cancer mortality trends among women and years of potential life Lost in the State of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil, from 1988 to 2007]. Epidemiol Serv Saude. 2011;20(2):161-72. Portuguese.) However, the index called years of productive life lost enabled to compare different causes of death in a specific population.(2929. Tauil PL, Lima DD. Aspectos éticos da mortalidade no Brasil. Rev Bioét. 1996;4(2):1-4.) Both indexes allowed to measure the amount of years of life lost by population because of cancer. In this study, we observed that high-incidence cancers were also those that potentially debilitate population, and they reduced individuals’ years of life up to 14 years, which is case of individuals affected by lung cancer. Of note is that use of tobacco products, a risk factor to all studied cancers, often start during individuals’ adolescence. For this reason, a residue of this tobacco use is expected in more advanced age ranges, especially among men.

Great number of years of life lost for ovarian cancer is because of this disease aggressiveness and also because it is discovered in more advanced phases, which results in extremely low survival rate. On the other hand, in uterine cancer, we observed low rate of years of potential life lost compared with prostate cancer, breast cancer, and bronchial and lung cancer. This finding emphasizes the importance of oncological care programs in Brazil to promote women health that massive investments occurred since 2005 to implement a national oncological care plan.

Prostate cancer had a reduced impact on years of potential life lost compared with cancer of high incidence in south region. The number of years of life lost by men can have an important relationship with extended survival of patients with prostate cancer that can achieve up to 5 years after diagnosis and treatment.(3030. Derossi SA, Paim JS, Aquino E, Silva LM. [Trends and years of potential life lost on cervical cancer mortality in Salvador (BA), Brazil 1979-1997]. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2001;47(2):163-70. Portuguese.)

Based on mean life expectancy of Brazilian population that in 2010 was considered around 75 years old, we can affirm that almost one fifth of total years of individual's life is lost when people had suffered neoplasias such as bronchial and lung cancer. There is also the socioeconomic impact because of productive years of life lost, especially in cases of uterine cancer, because this latter is a potentially avoidable cancer. Our data suggest that these significant losses of productive years in Southern Region is a negative socioeconomic impact to Brazil.

CONCLUSION

Both incidence and mortality of cancer are still high in Brazil with significant number of registers and deaths compare with worldwide rates. There is no agreement between number of hospital-based cancer registers and number of deaths because of cancer considering that, in some years, the register is lower than number of deaths. In addition, we observed a great number of death because of uterine cancer in south Brazil. Few studies were carried out to collected data on cancer profile in south Brazilian population, especially in States of Santa Catarina and Paraná.

REFERENCES

-

1World Health Organization (WHO). Cancer [Internet]. [cited 2017 Sep 21]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/

» http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/ -

2Instituto Nacional de Câncer José de Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA). Estimativa 2014 – Incidência de Câncer no Brasil. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2014;60(1):63-4.

-

3Stewart BW, Wild CP. World Cancer Report 2014. France: WHO Press; 2014.

-

4McLean RC, Logue J. The individual and combined effects of obesity and type 2 diabetes on cancer predisposition and survival. Curr Nutr Rep. 2015;4(1):22-32.

-

5Barros SG, Ghisolfi ES, Luz LP, Barlem GG, Vidal RM, Wolff FH, et al. Mate (chimarrão) é consumido em alta temperatura por população sob risco para o carcinoma epidermóide de esôfago. Arq Gastroenterol. 2000;37(1):25-30.

-

6Girianelli VR, Gamarra CJ, Azevedo e Silva G. Disparities in cervical and breast cancer mortality in Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2014;48(3):459-67.

-

7Ewald IP. Caracterização de um grupo de pacientes em risco para câncer de mama e ovário hereditários quanto a presença e frequência de rearranjos gênicos em BRCA [tese]. Porto Alegre: Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul; 2012.

-

8Kolling FL, Santos JS. [The influence of nutritional risk factors in the development of breast cancer in outpatients from the countryside of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil]. Sci Med. 2009;19(3):115-21. Portuguese.

-

9Brasil. Secretaria Nacional de Assistência à Saúde. Instituto Nacional de Câncer. Coordenação Nacional de Controle do Tabagismo, Prevenção e Vigilância do Câncer. Registros hospitalares de câncer: rotinas e procedimentos. Rio de Janeiro (RJ): Instituto Nacional do Câncer/MS; 2000.

-

10Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. DATASUS. Indicadores demográficos: mortalidade proporcional por idade [Internet]. Brasília (DF): Ministério da Saúde [citado 2017 Set 21]. Disponível em: http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/idb2000/fqa07.htm

» http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/idb2000/fqa07.htm -

11Paiva CJ, Cesse EA. [Aspects related to delay in diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer in a hospital in Pernambuco]. Rev Bras cancerol. 2015;61(1):23-30. Portuguese.

-

12Wunsch Filho V, Moncau JE. Mortalidade por cancer no Brasil 1980-1995: padrões regionais e tendências temporais. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2002;48(3):250-7.

-

13Oliveira Júnior FJ, Cesse EA. [Morbi-mortality by cancer in Recife in the 90s]. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2005;51(3):201-8. Portuguese.

-

14Paiva EP, Motta MC, Griep RH. [Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the detection of prostate cancer]. Acta Paul Enferm. 2010;23(1):88-93. Portuguese.

-

15Almeida JR, Pedrosa NL, Leite JB, Fleming TR, Carvalho VH, Cardoso AA. Marcadores tumorais: revisão de literatura. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2007;53(3):305-16.

-

16Quinn M, Babb P. Patterns and trends in prostate cancer incidence, survival, prevalence and mortality. Part I: international comparisons. BJU Int. 2002;90(2):162-73. Review.

-

17Instituto Nacional de Câncer José de Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA). Observatório da Política Nacional de Controle do Tabaco. Prevalência do Tabagismo [Internet]. Rio de Janeiro (RJ): Instituto Nacional de Câncer [citado 2015 out 30]. Disponível em: http://www2.inca.gov.br/wps/wcm/connect/observatorio_controle_tabaco/site/home/dados_numeros/prevalencia-de-tabagismo

» http://www2.inca.gov.br/wps/wcm/connect/observatorio_controle_tabaco/site/home/dados_numeros/prevalencia-de-tabagismo -

18Fonseca LA, Eluf-Neto J, Wunsch Filho V. Tendências da mortalidade por câncer nas capitais dos estados do Brasil, 1980-2004. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2010;56(3):309-12.

-

19Malta DC, Moura L, Souza MF, Curado MP, Alencar AP, Alencar GP. Lung cancer, cancer of the trachea, and bronchial cancer: mortality trends in Brazil, 1980-2003. J Bras Pneumol. 2007;33(5):536-43.

-

20Wünsch Filho V, Mirra AP, López RV, Antunes LF. [Tobacco smoking and cancer in Brazil: evidence and prospects]. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2010;13(2):175-87. Portuguese.

-

21Alvarenga M, Cotta AC, Dufloth RM, Schmitt FC. [Hereditary cancer syndrome: pathologists contribution for diagnosis and evaluation o prophylactic surgical procedures]. J Bras Patol Med Lab. 2003;39(2):167-77. Portuguese.

-

22Anders CK, Johnson R, Litton J, Phillips M, Bleyer A. Breast cancer before age 40 years. Semin Oncol. 2009;36(3):237-49. Review.

-

23Garicochea B, Morelle A, Andrighetti AE, Cancella A, Bós A, Werutsky G. [Age as a prognostic fator in early breast cancer]. Rev Saude Publica. 2009;43(2):311-7. Portuguese.

-

24Cadaval Gonçalves AT, Costa Jobim PF, Vanacor R, Nunes LN, Martins de Albuquerque I, Bozzetti MC. [Increase in breast cancer mortality in Southern Brazil from 1980 to 2002]. Cad Saude Publica. 2007;23(8):1785-90. Portuguese.

-

25Melo WA, Souza LA, Zurita RC, Carvalho MD. [Factors associated in breast cancer mortality in northwest paranaense]. Rev Gestao Saude. 2003;2087-94. Portuguese.

-

26Koifman S, Hatagima A. Exposição aos agrotóxicos e câncer ambiental. In: Peres F, Moreira JC, organizadores. É veneno ou é remédio: agrotóxicos, saúde e ambiente. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz; 2003. p. 75-99.

-

27Matos JC, Pelloso SM, Carvalho MD. Prevalence of Risk Factors for Breast Neoplasm in the City of Maringá, Paraná State, Brazil. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2010;18(3):352-9.

-

28Pereira MS, Ferreira LO, Silva GA, Lucio PS. [Breast cancer mortality trends among women and years of potential life Lost in the State of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil, from 1988 to 2007]. Epidemiol Serv Saude. 2011;20(2):161-72. Portuguese.

-

29Tauil PL, Lima DD. Aspectos éticos da mortalidade no Brasil. Rev Bioét. 1996;4(2):1-4.

-

30Derossi SA, Paim JS, Aquino E, Silva LM. [Trends and years of potential life lost on cervical cancer mortality in Salvador (BA), Brazil 1979-1997]. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2001;47(2):163-70. Portuguese.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

2018

History

-

Received

13 Feb 2017 -

Accepted

04 Aug 2017

Source: Instituto Nacional de Câncer José de Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA). Estimativa 2014 – Incidência de Câncer no Brasil. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2014;60(1):63-4.(

Source: Instituto Nacional de Câncer José de Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA). Estimativa 2014 – Incidência de Câncer no Brasil. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2014;60(1):63-4.( Source: Instituto Nacional de Câncer José de Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA). Estimativa 2014 – Incidência de Câncer no Brasil. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2014;60(1):63-4.(

Source: Instituto Nacional de Câncer José de Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA). Estimativa 2014 – Incidência de Câncer no Brasil. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2014;60(1):63-4.(