Abstracts

Diet and feeding ecology of the mutton snapper Lutjanus analis were investigated in the Abrolhos Bank, Eastern Brazil, the largest and richest coral reefs in the South Atlantic, where about 270 species of reef and shore fishes occur. To evaluate seasonal and ontogenetic shifts in the diet, specimens of L. analis were obtained through a fish monitoring program in four cities in southern Bahia State, from June 2005 to March 2007. Stomachs from 85 mutton snappers that ranged in size from 18.1 to 74.0 cm TL were examined. Prey were identified to the lowest possible taxon and assessed by the frequency of occurrence and volumetric methods. Variations in volume prey consumption were evaluated using non-metric multi-dimensional scaling ordination, analysis of similarity, and similarity percentage methods. Significant differences in diet composition among size classes were registered, whereas non significant differences between seasons were observed. Considering size-classes, food items consumption showed important variations: juveniles (<34.0 cm TL) fed mostly on crustaceans, sub-adults (34.1-50.0 cm TL) showed a diversified diet and adults (>50.1 cm TL) consumed basically fish, mostly Anguiliformes. Lutjanus analis is an important generalist reef predator, with a broad array of food resources and ontogenetic changes in the diet. This snapper species plays an important role on the trophic ecology of the Abrolhos Bank coral reefs.

Diet; Mutton snapper; Ontogenic variations; Seasonal

Foram avaliadas a dieta e a ecologia alimentar da cioba Lutjanus analis no Banco dos Abrolhos, Leste do Brasil. O Banco dos Abrolhos abrange os maiores e mais diversos recifes de corais do Atlântico Sul, onde cerca de 270 espécies de peixes recifais e costeiros ocorrem. Para a avaliação das variações sazonais e ontogênicas na dieta, exemplares de L. analis foram obtidos através de um programa de monitoramento em quatro cidades do extremo sul da Bahia, entre junho de 2005 e março de 2007. Estômagos de 85 exemplares com comprimento total variando entre 18,1 e 74,0 cm foram examinados. Os itens alimentares foram identificados até o menor nível taxonômico possível e avaliados através dos métodos de frequência de ocorrência e volumétrico. Variações no consumo das presas foram avaliadas através do método de escalonamento multidimensional não-métrico e métodos de análise de similaridade e percentagem de similaridade. Diferenças significativas na dieta foram observadas entre as classes de tamanho, porém estas não foram detectadas entre as estações do ano. Considerando as classes de tamanho, os itens consumidos apresentaram importantes variações: os juvenis (<34,0 cm CT) alimentaram-se preferencialmente de crustáceos, os subadultos (34,1-50,0 cm CT) apresentaram uma dieta diversificada e os adultos (>50,1 cm CT) consumiram basicamente peixes, principalmente Anguiliformes. Lutjanus analis é um importante predador recifal generalista, que consome um amplo espectro de presas, apresentando mudanças ontogênicas na dieta. Esse lutjanídeo desempenha um importante papel na ecologia trófica dos recifes de corais do Banco dos Abrolhos.

Feeding ecology of Lutjanus analis (Teleostei: Lutjanidae) from Abrolhos Bank, Eastern Brazil

Matheus Oliveira FreitasI,II; Vinícius AbilhoaII; Gisleine Hoffmann da Costa e SilvaIII

IPrograma de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia e Conservação - UFPR. Setor de Ciências Biológicas. Cx. Postal 19031, 81531-980 Curitiba, PR, Brazil. serranidae@gmail.com

IIGrupo de Pesquisa em Ictiofauna - GPIC, Museu de História Natural Capão da Imbuia, Prefeitura de Curitiba. Rua Professor Benedito Conceição, 407, 82810-080 Curitiba, PR, Brazil

IIIUniversidade Tuiuti do Paraná. Rua Sydnei Antônio Rangel Santos, 238, 82010-330 Curitiba, PR, Brazil

ABSTRACT

Diet and feeding ecology of the mutton snapper Lutjanus analis were investigated in the Abrolhos Bank, Eastern Brazil, the largest and richest coral reefs in the South Atlantic, where about 270 species of reef and shore fishes occur. To evaluate seasonal and ontogenetic shifts in the diet, specimens of L. analis were obtained through a fish monitoring program in four cities in southern Bahia State, from June 2005 to March 2007. Stomachs from 85 mutton snappers that ranged in size from 18.1 to 74.0 cm TL were examined. Prey were identified to the lowest possible taxon and assessed by the frequency of occurrence and volumetric methods. Variations in volume prey consumption were evaluated using non-metric multi-dimensional scaling ordination, analysis of similarity, and similarity percentage methods. Significant differences in diet composition among size classes were registered, whereas non significant differences between seasons were observed. Considering size-classes, food items consumption showed important variations: juveniles (<34.0 cm TL) fed mostly on crustaceans, sub-adults (34.1-50.0 cm TL) showed a diversified diet and adults (>50.1 cm TL) consumed basically fish, mostly Anguiliformes. Lutjanus analis is an important generalist reef predator, with a broad array of food resources and ontogenetic changes in the diet. This snapper species plays an important role on the trophic ecology of the Abrolhos Bank coral reefs.

Key words: Diet, Mutton snapper, Ontogenic variations, Seasonal.

RESUMO

Foram avaliadas a dieta e a ecologia alimentar da cioba Lutjanus analis no Banco dos Abrolhos, Leste do Brasil. O Banco dos Abrolhos abrange os maiores e mais diversos recifes de corais do Atlântico Sul, onde cerca de 270 espécies de peixes recifais e costeiros ocorrem. Para a avaliação das variações sazonais e ontogênicas na dieta, exemplares de L. analis foram obtidos através de um programa de monitoramento em quatro cidades do extremo sul da Bahia, entre junho de 2005 e março de 2007. Estômagos de 85 exemplares com comprimento total variando entre 18,1 e 74,0 cm foram examinados. Os itens alimentares foram identificados até o menor nível taxonômico possível e avaliados através dos métodos de frequência de ocorrência e volumétrico. Variações no consumo das presas foram avaliadas através do método de escalonamento multidimensional não-métrico e métodos de análise de similaridade e percentagem de similaridade. Diferenças significativas na dieta foram observadas entre as classes de tamanho, porém estas não foram detectadas entre as estações do ano. Considerando as classes de tamanho, os itens consumidos apresentaram importantes variações: os juvenis (<34,0 cm CT) alimentaram-se preferencialmente de crustáceos, os subadultos (34,1-50,0 cm CT) apresentaram uma dieta diversificada e os adultos (>50,1 cm CT) consumiram basicamente peixes, principalmente Anguiliformes. Lutjanus analis é um importante predador recifal generalista, que consome um amplo espectro de presas, apresentando mudanças ontogênicas na dieta. Esse lutjanídeo desempenha um importante papel na ecologia trófica dos recifes de corais do Banco dos Abrolhos.

Introduction

The diets and trophic relationships of top predators and mesopredators are important for understanding their ecological roles. Addressing this lack of data has become more important with the increasing recognition that fish mesopredators may be important in transmitting indirect effects of top predators (e.g. Myers et al., 2007; Heithaus et al., 2008; Baum & Worm, 2009; Ferretti et al., 2010). In coral reefs this role is represented by sharks, jacks (Carangidae), groupers (Serranidae), and snappers (Lutjanidae) (Polovina, 1984; Meyer et al., 2007).

Fishes from family Lutjanidae are among the most important fishery resources in tropical and subtropical regions (Grimes, 1987; Duarte & Garcia, 1999). They are heavily exploited by commercial fisheries in Northeastern and Central Brazil since the introduction of "pargueiras" (hook and line) by Portugueses during the 1950's and 1960's as a consequence of declining stocks of tuna fishery (Resende et al., 2003).

The mutton snapper Lutjanus analis (Cuvier, 1828) is found in the tropical Western Atlantic, from Massachusetts (USA) to Southeastern Brazil, with relatively high abundances recorded in Florida, Bahamas, and the Antilles (Figueiredo, 1980; Allen, 1985; Menezes & Anderson, 2003). Sub-adults and juveniles are found in a variety of habitats, such as sand bottoms, seaweed dominated reefs, bays, mangroves, and estuaries (Allen, 1985; Claro & Lindeman, 2004). Adults are found on hard substrates, generally on offshore deep reefs and less commonly on coastal environments (Cocheret de la Morinière et al., 2003; Frédou & Ferreira, 2005).

Despite its ecological and commercial importance (Claro & Lindeman, 2004; Moura & Lindeman, 2007) there is little information on its feeding ecology. Available evidences indicate that the diet of L. analis include fishes, shrimps, crabs, gastropods, and cephalopods (Allen, 1985; Heck & Weinstein, 1989; Claro & Lindeman, 2004; Pimentel & Joyeux, 2010), a general pattern for the family Lutjanidae (Duarte & Garcia, 1999; Santamaría-Miranda et al., 2003; Lee & Szedlmayer, 2004; Rojas et al., 2004; Rojas-Herrera et al., 2004; Molina et al., 2005). Although snappers are generally considered nocturnal predators (Claro & Lindeman, 2004), L. analis fed diurnally (Watanabe, 2001), showing a high variability in foraging styles, according to fish size and time of day (Mueller et al., 1994).

In order to understand the role that L. analis plays in the trophic food web of the Abrolhos Bank, the present study examined the diet and feeding ecology of specimens obtained through a fish monitoring program. Emphasis was placed on the assessment of seasonal and ontogenetic shifts on feeding habits. This dietary information is critical for modeling trophic pathways and assessing the implications of predator removal from a system (Farmer & Wilson, 2010), and combined with fisheries data, information on predator/prey abundance and consumption rates of predators can be used to assess the magnitude of trophic fluxes.

Material and Methods

This study was carried out in the Abrolhos Bank, Bahia State, which includes a wide portion (42,000 km2) of the continental shelf, with depth rarely exceeding 30 m and a shelf edge at about 70 m depth (16º40'-19º40'S; 39º10'-37º 20'W) (Fig. 1). The region comprises the largest and richest coral reefs in the South Atlantic, as well as an extensive mosaic of algal bottoms, mangrove forests, beaches, and vegetated sandbanks (Leão, 1999; Leão & Kikuchi, 2005). About 270 species of reef and shore fishes occur at the Abrolhos Bank (Moura & Francini-Filho, 2006). Despite its importance, with nearly 10.000 artisanal fishermen operating in the area, the region's reef fisheries are still poorly known and were not included in Frédou et al. (2006) revision of Northeastern Brazil reef fisheries.

Specimens of L. analis were obtained through a fish landing monitoring program that target fleets on hand line, longline and spear fishing in the Cities of Nova Viçosa, Caravelas, Alcobaça, and Prado (Fig. 1) between June 2005 and March 2007, together with the communities where they landed the craft caught. Morphometric data and weight were recorded to the nearest centimeter and decigrams respectively. Stomach were removed and immediately fixed in 10% formalin solution for 24 h and subsequently transferred and stored in 70% alcohol.

Stomach contents were examined in the laboratory using a stereomicroscope. The identification of food items was performed as refined as possible according to literature data (Melo, 1996; Amaral et al., 2005) and consultation with experts. The frequency of occurrence (i.e., percentage of stomachs in which a food item occurs considering all stomachs examined) and the proportion by volume (i.e., percentage participation of each item in the total food) of a given food item were determined (Hyslop, 1980; Bowen, 1996).

For temporal analysis, the seasons were defined as follow: winter (June - August), spring (September - November), summer (December - February), and autumn (March - May).

For ontogenic diet shift, individuals were divided into seven size classes according to the total length (TL cm) in: Class 1 =18.1-26.0; Class 2 = 26.1-34.0; Class 3 = 34.1-42.0; Class 4 = 42.1-50.0; Class 5 = 50.1-58.0; Class 6 = 58.1-66.0, and Class 7 = 66.1-74.0 cm, defined following the sturges formulation (Silva & Souza, 1987). Juvenile (<34.0 cm TL), sub-adult (34.1-50.0 cm TL), and adult (>50.1cm TL) stages were also used to assess ontogenetic diet changes. Stages classification was performed using the study carried out by Freitas et al. (2011), which indicate that the L50 of L. analis in the Abrolhos Bank occurs at around 38.0 to 40.0 cm TL, close to the results registered for the Cuban shelf (García-Cagide et al., 2001; Sierra et al., 2001; Claro & Lindeman, 2004).

Differences in prey consumption using quantitative data (volume prey) among seasons and sizes classes were tested with cluster based on Bray-Curtis similarities and hierarchical agglomerative group-average clustering was constructed with the PRIMER program (ver. 6.0, Plymouth Marine Laboratory, Plymouth, England). Data was investigated using analysis of similarity (ANOSIM) and similarity percentage (SIMPER) methods.

A Non-metric Multi-Dimensional Scaling (NMDS) ordination was performed in order to better visualize the similarities between seasons and size classes. Samples in the NMDS plot were grouped according to the results of the cluster analysis using the single linkage method (Clarke & Warnick, 2001). An analysis of similarity percentages (SIMPER) considering the different food items was conducted to examine potential differences in the diet. This latter method helps in determining which food item is responsible for differences recorded.

Results

A total of 85 stomachs of Lutjanus analis were analyzed. The food items were grouped into four main categories: Gastropoda, Stomatopoda, Decapoda, and Fish. The category that showed the greatest diversity (i.e. Crustacea) was further refined to Stomatopoda, Decapoda Dendrobranchiata (shrimps), and Decapoda Brachyura (crabs and soft crab) (Table 1).

Crustaceans, particularly Decapods, were by far the most common and representative food item recorded, followed by Fish. Decapoda Brachyura (crabs and soft-crabs), had a great abundance in the analysis and was represented by five families. Gastropods were represented only by Fissurellacea. Stomatopods could not be identified to more refined taxonomic categories due to the high degree of digestion. Only one family (Sergestoidea) of Dendrobranchiata Decapoda (shrimps) was recorded. Fishes most commonly recorded were, in decreasing order: Anguilliformes, Perciformes, and Gobiesociformes.

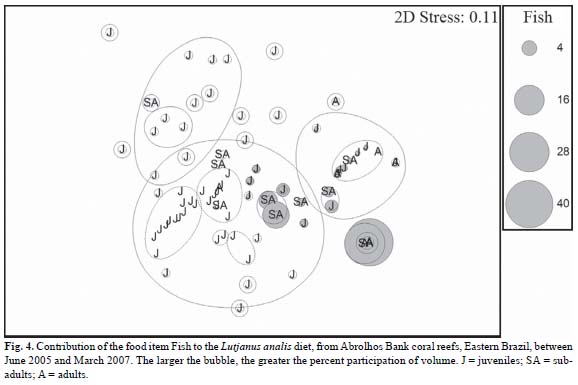

The NMDS ordination and similarity analysis (ANOSIM) showed no significant differences between the seasons of the year in the diet of the species (Global R = 0.056, P =10.6%). On the other hand, the composition of the diet between the classes of length (ontogenic) showed significant differences (Global R = 0.308, P = 2.7%) (Fig. 2). Considering the main life stages (juvenile, sub-adult, and adult), some food items were determinant for the resulting ordination, such as Decapoda (Fig. 3) and Fish (Fig. 4).

The SIMPER analysis showed that the most of dissimilarities among size classes was produced by the food items: Decapoda remains, Dendobranchiata, Portunidae, Fish, and Xanthidae (Table 2). In class 1, Decapoda remains contributed with 64.73%, followed by Dendobranchiata and Portunidae (18.93% and 7.85%, respectively). In Class 2, Decapods remains was also the most representative food item (70.78%) followed by Fish (19.60%). In Class 3, besides Decapoda remains (66.34%) were also important Fish (19.43%) and Xanthidae (6.03%). In classes 4, 5, 6, and 7 Fish was the predominant food, corresponding to 100% of the diet.

Discussion

Decapod crustaceans and Fish were the most important food items in the carnivorous diet of L. analis in the Abrolhos Bank. Several studies have already reported the importance of these food items for L. analis (Randall, 1967; Claro, 1981; Guevara et al., 1994; Sierra & Popova, 1997; Duarte & Garcia, 1999; Sierra et al., 2001; Claro & Lindeman, 2004; Pimentel & Joyeux, 2010), and also for other congeners as L. synagris (Linnaeus, 1758) (Duarte & Garcia, 1999; Pimentel & Joyeux, 2010), L. campechanus (Poey, 1860) (Lee & Szedlmayer, 2004), L. guttatus (Steindachner, 1869) (Rojas et al., 2004; Rojas-Herrera et al., 2004), L. peru (Nichols & Murphy, 1922) (Santamaría-Miranda et al., 2003), L. argentiventris (Peters, 1869), and L. colorado Jordan & Gilbert, 1882 (Molina et al., 2005).

The diet based mostly on pelagic crustaceans (specially Decapod) and Fish may reflect the prey availability and abundance in the environment (Wootton, 1990; Moyle & Cech, 1996; Claro & Lindeman, 2004), or are related with the Lutjanidae ability to exploit it (Claro, 1981; Heck & Weinstein, 1989; Duarte & Garcia, 1999; Claro & Lindeman, 2004; Rojas et al., 2004; Molina et al., 2005). For L. analis we believe that this ability can be related to morphological changes during the ontogenetic development (e.g. mouth gap), affecting prey size selectivity, a result already recorded for L. apodus (Roocker, 1995). In the other hand, it is important to consider that juveniles and adults of L. analis display different foraging styles, where small individuals displayed proportionally higher picking and midwater strikes during morning and evening, whereas individuals large winnowed proportionally more often than small or medium fish during evening (Mueller et al., 1994).

Despite the fact that Monteiro et al. (2009) and Pimentel & Joyeux (2010) suggested temporal changes in the diet composition of snappers in the Brazilian coast, we did not observe seasonal variation for L. analis. We believe that this variation is related with the local changes in prey availability (Randal, 1967). In fact, Monteiro et al. (2009) and Pimentel & Joyeux (2010) worked in mangrove environments, which are often subjected to more acute environmental changes than are reef faunas (Sierra et al., 2001).

Considering size-classes analyses, food items consumption showed important variations: juveniles consumed preferentially crustaceans, sub-adults showed a diversified diet, and adults feed basically on fish. Even though few stomachs of larger individuals were analyzed, similar feeding pattern was also observed for L. analis in the West Indies (Randall, 1967), in the Caribbean coast of Panama (Heck & Weinstein, 1989) in the Cuban platform (Claro, 1981; Sierra et al., 2001) and Southeastern Brazil (Pimentel & Joyeux, 2010). This adaptation probably aims to reduce the competition for food or meet physiological needs that the fish may have during its ontogenetic development in terms of migration, sexual maturation and/or reproduction (Braga & Braga, 1987; Gerking, 1994; Sierra et al., 2001).

On the other hand, ontogenetic shifts in the diet can also occur when juveniles and adults occupy different regions (Zavala-Camin, 1996; Bertoncini et al., 2003; Machado et al., 2008). Allen (1985), Lindeman et al. (1998), and Claro & Lindeman (2004) have noted two basic types of habitat selection for snappers: the juveniles of some species are usually found on shallow estuaries, while adults inhabit bays, estuaries, and reef environments of shelf waters. Starck (1970), for example, observed changes in diet of juveniles and adults of Lutjanus griseus (Linnaeus, 1758) related with the migration from estuarine areas to deeper waters. Our data generally agree with this statement, because juveniles and sub-adults of L. analis occur in estuarine and marine coastal environments (Randall, 1967; Allen, 1985; Claro & Lindeman, 2004; Pimentel & Joyeux, 2010), while adults inhabit hard substrates in offshore waters and reef environments (Cocheret de la Morinière et al., 2003; Frédou & Ferreira, 2005).

According to our data, this mesopredator plays an important role on the trophic ecology of the Abrolhos Bank coral reefs, because it is an important reef predator with a wide range of food resources. Despite classified as vulnerable in the IUCN red list of endangered species (Huntsman, 1996), L. analis is a commercially important species in the Brazilian Northeastern coast, and previous stock assessments in the study region (Klippel et al., 2005) indicated that it is moderately overfished. Impacts of chronic overfishing are evident in population depletions worldwide, and the removal of predatory fishes is also likely to have significant indirect effects on marine ecosystems (Farmer & Wilson, 2010), influencing a range of ecological processes (Babcock et al., 1999; Pinnegar et al., 2000; Willis & Anderson, 2003).

Acknowledgements

This study is contribution of the Abrolhos Node of the Marine Managed Areas Science Program (MMAS) of Conservation International (CI), funded by the Betty and Gordon Moore Foundation. It also benefited from Conservation Leardship Program (CLP), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado da Bahia (FAPESB), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), and Conservation International Brazil - Marine Program grants to MOF. We acknowledge Juliane Cebola, Ronaldo Francini-Filho (Universidade Federal da Paraíba), Rodrigo Leão de Moura, and M.Sc. Guilherme Dutra (Marine Program - Conservation International Brazil) for the support and contributions in the text. We thank Universidade Tuiuti do Paraná and Museu de História Natural Capão da Imbuia for laboratory facilities. Hugo Bornatowski and Jean Vitule (Grupo de Pesquisa em Ictiofauna) comments improved the manuscript. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for their useful suggestions.

Literature Cited

Accepted March 22, 2011

- Allen, G. R. 1985. FAO fishes catalogue vol. 6. Snappers of the world. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of lutjanid species known to date. FAO Fish Synopsis, 125, vol. 6, 208p.

- Amaral, A. C. Z., A. E. Rizzo & E. P. Arruda. 2005. Manual de identificação dos invertebrados marinhos da região Sudeste-Sul do Brasil. São Paulo, EDUSP, 288p.

- Anderson, W. D. Jr. 2003. Lutjanidae. In: Carpenter, K. E. (Ed.). The living marine resources of the Western Central Atlantic. Volume 3: Bony fishes part 2 (Opistognathidae to Molidae). FAO Species Identification Guide for Fishery Purposes and American Society of Ichthyologist and Herpetologists Special Publication, 5: 1479-1504.

- Babcock, R. C., S. Kelly, N. T. Shears, J. W. Walker & T. J. Willis. 1999. Changes in community structure in temperate marine reserves. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 189: 125-134.

- Baum, J. K. & B. Worm. 2009. Cascading top-down effects of changing oceanic predator abundances. Journal of Animal Ecology, 78: 699-714.

- Bertoncini, A. A., L. F. Machado, M. Hostim-Silva & J. P. Barreiros. 2003. Reproductive biology of the dusky grouper (Epinephelus marginatus, Lowe, 1834) (Perciformes, Serranidae, Epinephelinae), in Santa Catarina, Brazil. Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology, 46: 373-381.

- Braga, F. M. S. & M. A. S. Braga. 1987. Estudo do hábito alimentar de Prionotus punctatus (Bloch, 1797) (Teleostei, Triglidae), na região da Ilha Anchieta, Estado de São Paulo, Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Biologia, 47: 31-36.

- Bowen, S. H. 1996. Quantitative description of the diet. Pp. 513-532. In: Murphy, B. R. & D. W. Willis (Eds.). Fisheries techniques, Bethesda. American Fisheries Society, 532p.

- Clarke, K. R. & R. W. Warnick. 2001. Change in marine communities: an aproach to statistical analysis and interpretation. Plymouth Marine Laboratory, UK, Plymouth, 859p.

- Claro, R. 1981. Ecologia y ciclo de vida de la biajaiba Lutjanus synagris (Linnaeus) em la platafoma cubana. II: Biologia pesqueira. Informe Científico-Técnico. Academia de Ciências de Cuba, 177: 1-53.

- Claro, R. & K. C. Lindeman. 2004. Biología y manejo de los pargos (Lutjanidae) en el Atlántico occidental. Instituto de Oceanología, CITMA, La Habana, 472p.

- Cocheret de la Morinière, E., B. J. A. Pollux, I. Nagelkerken, M. A. Hemminga, A. H. L. Huiskes & G. van der Velde. 2003. Ontogenetic dietary changes of coral reef fishes in the mangrove-seagrass-reef continuum: stable isotopes and gut-content analysis. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 246: 279-289.

- Duarte, L. O. & C. B. García. 1999. Diet of the mutton snapper Lutjanus analis (Cuvier) from the gulf of Salamanca, Colombia, Caribbean Sea. Bulletin of Marine Science, 65: 453-465.

- Farmer, B. M. & S. K. Wilson. 2010. Diet of finfish targeted by fishers in North West Australia and the implications for trophic cascades. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 91: 71-85.

- Ferretti, F., B. Worm, G. L. Britten, M. R. Heithaus & H. K. Lotze. 2010. Patterns and ecosystem consequences of shark declines in the ocean. Ecology Letters, 13: 1055-1071.

- Frédou, T. & B. P. Ferreira. 2005. Bathymetric trends of Northeastern Brazilian snappers (Pisces, Lutjanidae): implications for the reef fishery dynamic. Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology, 48(5): 787-800.

- Frédou, T., B. P. Ferreira & Y. Letourneur. 2006. A univariate and multivariate study of reef fisheries off northeastern Brazil. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 63: 883-896.

- Freitas, M. O., R. L. Moura, R. B. Francini-Filho & C. V. Minte-Vera. 2011. Spawning patterns of commercially important reef fishes (Lutjanidae and Serranidae) in the tropical Western South Atlantic. Scientia Marina, 75(1): 135-146.

- García-Cagide, A., R. Claro & B. V. Koshelev. 2001. Reproductive patterns of fishes of the Cuban shelf. Pp. 71-102. In: Claro, R., K. C. Lindeman & L. R. Parenti (Eds.). Ecology of the marine fishes of Cuba. Washington, D. C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 253p.

- Gerking, S. D. 1994. Feeding Ecology of fish. San Diego, Academic Press, 416p.

- Grimes, C. B. 1987. Reproductive biology of the Lutjanidae: a review. Pp. 239-294. In: Polovina, J. J. & S. Ralston (Eds.). Tropical snappers and groupers: biology and fisheries management. Colorado, Westview Press.

- Guevara, E., A. Bosch, R. Suárez & R. Lalana. 1994. Alimentación natural de tres especies de pargos (Pisces: Lutjanidae) en el Archipiélago de los Canarreos, Cuba. Revista de Investigaciones Marina, 15: 63-72.

- Heck, K. L. Jr. & M. P. Weinstein. 1989. Feeding habits of juvenile fishes associated with Panamanian seagrass meadows. Bulletin of Marine Science, 45: 629-636.

- Heithaus, M. R., A. Frid, A. J. Wirsing & B. Worm. 2008. Predicting ecological consequences of marine top predator declines. Trends Ecology and Evolution, 23(4): 202-210.

- Huntsman, G. 1996. Lutjanus analis In: IUCN 2010. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.1. Available at www.iucnredlist.org Accessed April 7, 2010.

- Hyslop, E. J. 1980. Stomach contents analysis - a review of methods and their application. Journal of Fish Biology, 17: 411-429.

- Klippel, S., G. O. Paulo, A. S. Costa, A. S. Martins & M. B. Peres. 2005. Avaliação dos estoques de lutjanídeos da costa central do Brasil: análise de coortes e modelo preditivo de Thompson e Bell para comprimentos. Pp. 83-98. In: Costa, P. A. S., A. S. Martins & G. Olavo (Eds.). Pesca e potenciais de exploração de recursos vivos na região central da zona econômica exclusiva brasileira. Série Livros - Documentos REVIZEE - Score Central. Rio de Janeiro, Museu Nacional do Rio de Janeiro, 248p.

- Leão, Z. M. A. N. 1999. Abrolhos, BA, o complexo recifal mais extenso do Atlântico Sul. Pp. 345-359. In: Schobbenhaus, C. D. A., E. T. Campos, M. Queiroz & M. Berbert-Born (Eds.). Sítios geológicos e paleontológicos do Brasil. DNPM/CPRM, Brasília. DNPM/CPRM - Comissão Brasileira de Sítios Geológicos e Paleobiológicos (SIGEP). Available at: http://www.anp.gov.br/brnd/round6/guias/SISMICA/SISMICA_R6/biblio/Biblio2004/Le%E3o%20ZMA%20Abrolhos.pdf Accessed May 30, 2011.

- Leão, Z. M. A. N. & R. Kikuchi. 2005. A relic coral fauna threatened by global changes and human activities, Eastern Brazil. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 51: 599-611.

- Lee, J. D. & S. T. Szedlmayer. 2004. Diet shifts of juvenile red snapper (Lutjanus campechanus) with changes in habitat and fish size. Fishery Bulletin, 102: 366-375.

- Lindeman, K. C., G. A. Diaz, J. E. Serafy & J. S. Ault. 1998. A spatial framework for assessing cross-shelf habitat use among newly settled grunts and snappers. Procedings the Gulf and Caribbean Fisheries Institute, 50: 385-416.

- Machado, L. F., F. A. M. L. Daros, A. A. Bertoncini, M. Hostim-Silva & J. P. Barreiros. 2008. Feeding strategy and trophic ontogeny in Epinephelus marginatus (Serranidae) from Southern Brazil. Cybium, 32(1): 33-41.

- Melo, G. A. S. 1996. Manual de identificação dos Brachyura (Caranguejos e Siris) do litoral brasileiro. São Paulo, Plêiade/FAPESP, 604p.

- Menezes, N. A. & J. L. Figueiredo. 1980. Manual de Peixes Marinhos do Sudeste do Brasil. IV. Teleósteo (3). São Paulo, Museu de Zoologia, Universidade de São Paulo, 96p.

- Molina, J. P. A., A. S. Miranda, M. S. Lozano & M. N. H. Moreno. 2005. Hábitos alimenticios del pargo amarillo "Lutjanus argentiventris" y del pargo rojo "Lutjanus colorado" (Pisces: Lutjanidae) en el norte de Sinaloa, México. Revista de Biologia Marina y Oceanografia, 40(1): 33-44.

- Monteiro, D. P., T. Giarrizzo & V. Isaac. 2009. Feeding ecology of juvenile dog snapper Lutjanus jocu (Bloch and Shneider, 1801) (Lutjanidae) in intertidal mangrove creeks in Curuçá Estuary (Northern Brazil). Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology, 52(6): 1421-1430.

- Moura, R. L. & R. B. Francini-Filho. 2006. Reef and shore fishes of the Abrolhos Region, Brazil. Pp. 40-55. In: Dutra, G. F., G. R. Allen, T. Werner & S. A. Mckenna (Eds.). A rapid marine biodiversity assessment of the Abrolhos Bank, Bahia, Brazil. RAP Bulletin of Biological Assessment 38. Washington D. C., Conservation International.

- Moura, R. L. & K. C. Lindeman. 2007. A new species of snapper (Perciformes: Lutjanidae) from Brazil, with comments on distribuition of Lutjanus griseus and L apodus Zootaxa, 1422: 31-43.

- Moyle, P. B. & J. J. Cech. 1996. Fishes: an introduction to ichthyology. 3 Ed. New Jersey. Prentice-Hall Inc, 590p.

- Mueller, K. W., G. D. Dennis, D. B. Eggleston & R. I. Wicklund. 1994. Size species social interactions and foraging styles in a shallow water population of mutton snapper, Lutjanus analis (Pisces: Lutjanidae), in the central Bahamas. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 40: 175-188.

- Myers, R. A., J. K. Baum, T. D. Shepherd, S. P. Powers & C. H. Peterson. 2007. Cascading Effects of the Loss of Apex Predatory Sharks from a Coastal Ocean. Science, 315: 1846-1850.

- Pimentel, C. R. & J. C. Joyeux. 2010. Diet and food partitioning between juveniles of mutton Lutjanus analis, dog Lutjanus jocu and lane Lutjanus synagris snappers (Perciformes: Lutjanidae) in a mangrove-fringed estuarine environment. Journal of Fish Biology, 76(10): 2299-2317.

- Pinnegar, J. K., N. V. C. Polunin, P. Francour, F. Badalamenti, R. Chemello, M. L. Harmelin-Vivien, B. Hereu, M. Milazzo, M. Zabala, G. D'Anna & C. Pipitone. 2000. Trophic cascades in benthic marine ecosystems: lessons for fisheries and protected-area management. Environmental Conservation, 27: 179-200.

- Polovina, J. J. 1984. Model of a coral reef ecosystem I. The ecopath model and its application to French Frigate Shoals. Coral Reefs, 3: 1-11.

- Randall, J. E. 1967. Food habits of reef fishes of the West Indies. Studies in Tropical Oceanography, 5: 665-847.

- Resende, S. M., B. P. Ferreira & T. Frédou. 2003. A pesca de lutjanídeos no nordeste do Brasil: Histórico das pescarias, características das espécies e relevância para o manejo. Boletim Técnico Científico do Cepene, 11: 257 - 270.

- Rojas, M., E. F. Maravilla & B. Chicas. 2004. Hábitos alimentarios del pargo mancha Lutjanus guttatus (Pisces: Lutjanidae) en Los Cóbanos y Puerto La Libertad, El Salvador. Revista de Biologia Tropical, 52: 163-170.

- Rojas-Herrera, A. A., M. Mascaró & X. Chiappa-Carrara. 2004. Hábitos alimentarios de los peces Lutjanus peru y Lutjanus guttatus (Pisces: Lutjanidae) en Guerrero, México. Revista de Biologia Tropical, 52: 959-972.

- Roocker, J. R. 1995. Feeding ecology of the schoolmaster snapper, Lutjanus apodus (Walbaum), from southwestern Puerto Rico. Bulletin of Marine Science, 56(3): 881-894.

- Santamaría-Miranda, A., J. F. Elorduy-Garay & A. A. Rojas-Herrera. 2003. Hábitos alimentarios de Lutjanus peru (Pisces: Lutjanidae) en las costas de Guerrero, México. Revista de Biologia Tropical, 51: 503-518.

- Sierra, L. M., R. Claro & O. A. Popova. 2001. Trophic biology of the marine fishes of Cuba. Pp. 115-148. In: Claro, R., K. C. Lindeman & L. R. Parenti (Eds.). Ecology of the Marine Fishes of Cuba. Washington and London, Smithsonian Institution Press, 253p.

- Sierra, L. M. & O. A. Popova. 1997. Relaciones tróficas de los juveniles de cinco espécies de pargo (Pisces: Lutjanidae) en Cuba. Revista de Biologia Tropical, 44-45: 499-506.

- Silva, J. X. & M. J. L. Souza. 1987. Análise ambiental. Rio de Janeiro, UFRJ, 196p.

- Starck, W. A. 1970. Biology of the Gray snapper Lutjanus griseus (Linnaeus), in Florida Keys. Studies Tropical Oceanography, 10: 1-150.

- Watanabe, W. O. 2001. Species Profile: Mutton Snapper. SRAC Publications. United States Department of Agriculture, Cooperative State Research, Education and Extension Service, 725.

- Willis, T. J. & M. J. Anderson. 2003. Structure of cryptic reef fish assemblages: relationships with habitat characteristics and predator density. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 257: 209-221.

- Wootton, R. J. 1990. Ecology of teleost fishes. London, Chapman and Hall, 404p.

- Zavala-Camin, L. A. 1996. Introdução aos estudos sobre alimentação natural em peixes. Maringá, Eduem, 125p.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

17 June 2011 -

Date of issue

June 2011