ABSTRACT

Treatment with music has shown effectiveness in the treatment of general behavioural and cognitive symptoms of patients with various types of dementia.

Objective:

To assess the effectiveness of treatment with music on the memory of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Methods:

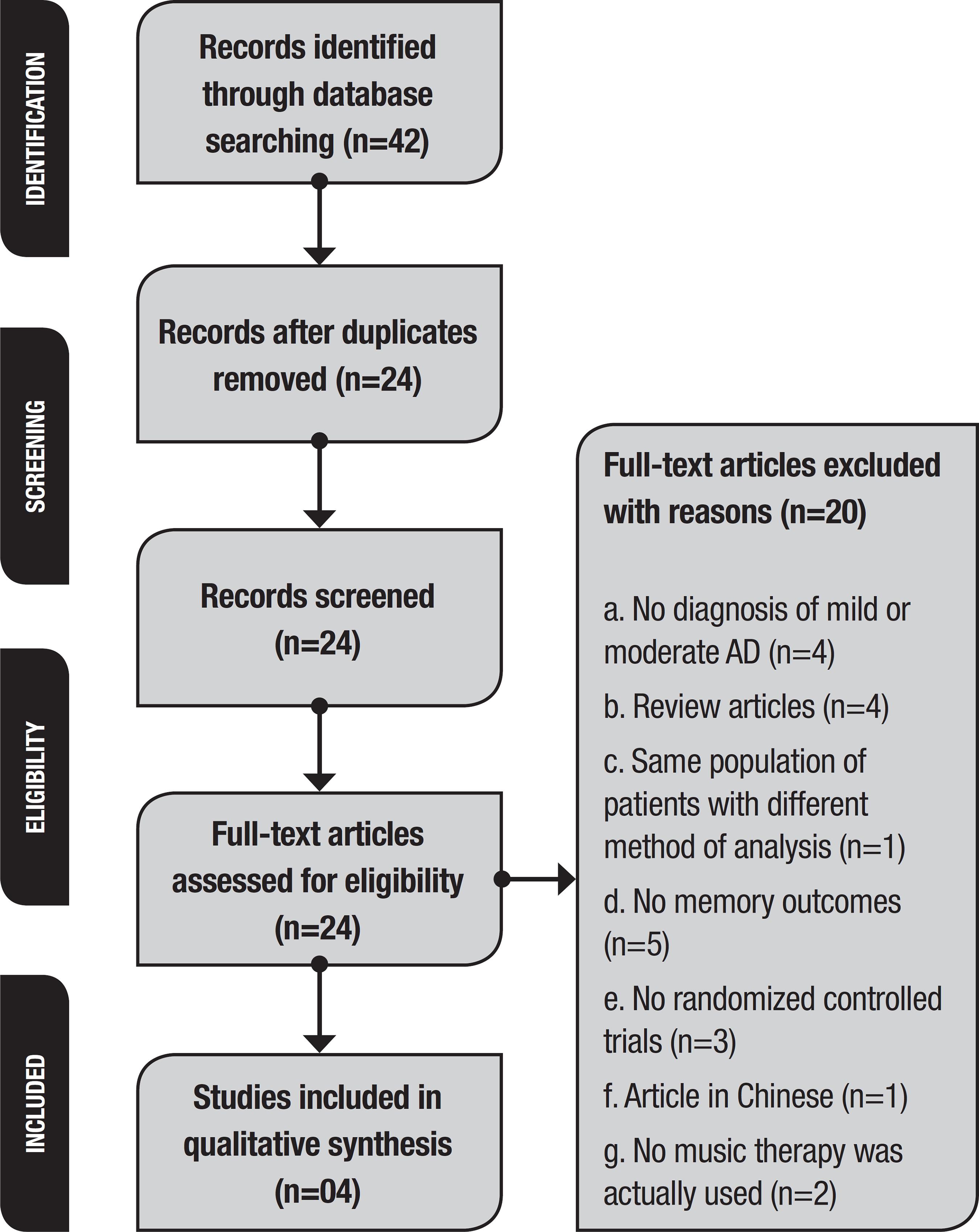

A systematic search was performed on PubMed (Medline), Cochrane Library, PsycINFO and Lilacs databases up to June 2017 and included all randomized controlled trials that assessed memory using musical interventions in patients with AD.

Results:

Forty-two studies were identified, and 24 studies were selected. After applying the exclusion criteria, four studies involving 179 patients were included. These studies showed the benefits of using music to treat memory deficit in patients with AD.

Conclusion:

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review focusing on randomized trials found in the literature that analysed the role of musical interventions specifically in the memory of patients with AD. Despite the positive outcome of this review, the available evidence remains inconsistent due to the small number of randomized controlled trials.

Key words:

music; music therapy; memory; Alzheimer’s disease; randomized clinical trials; systematic review

RESUMO

O tratamento com música vem demonstrando eficácia no tratamento de sintomas comportamentais e cognitivos gerais de pacientes com vários tipos de demência.

Objetivo:

Avaliar a eficácia do tratamento com música para a memória de pacientes com doença de Alzheimer (DA).

Métodos:

Foi realizada uma revisão sistemática nos bancos de dados PubMed (Medline), Cochrane Library, PsycINFO e Lilacs até junho de 2017 que incluiu todos os ensaios clínicos randomizados controlados usando intervenções musicais em pacientes com DA e que avaliaram a memória.

Resultados:

Foram encontrados 42 estudos sendo selecionados 24 estudos completos. Após a aplicação dos critérios de exclusão, foram incluídos quatro estudos envolvendo 179 pacientes. Esses estudos mostraram os benefícios do uso da música para tratar o déficit de memória em pacientes com DA.

Conclusão:

Até o momento, este é o primeiro estudo de revisão sistemática que utilizou ensaios clínicos randomizados da literatura que analisou o papel das intervenções musicais especificamente na memória de pacientes com DA. Apesar do resultado positivo desta revisão, a evidência disponível permanece frágil devido ao pequeno número de ensaios clínicos randomizados.

Palavras-chave:

música; musicoterapia; memória; doença de Alzheimer; ensaios clínicos randomizados; revisão sistemática

Dementia is a public health problem that affects approximately 50 million people worldwide. With the increase in life expectancy, it is estimated that the prevalence of dementia will increase significantly in the coming decades and may triple by 2050.11 Blackburn R, Bradshaw T. Music therapy for service users with dementia: A critical review of the literature. J Psychiatri Ment Health Nurs. 2014;21(10):879-88.

2 Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017; 310:2673-4.-33 McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CRJr, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011;7(3):263-9. There are several causes of dementia, and its diagnosis depends on the knowledge of the different clinical manifestations and on a sequence of specific complementary exams. The four most common forms of dementia are Alzheimer’s disease (AD), vascular dementia (VD), frontotemporal dementia (FTD), and dementia with Lewy bodies.44 Schlindwein-Zanini R. Dementia in the elderly:Neuropsychological aspects. Rev Neurosci 2010;18(2):220-6. For dementia diagnosis, cognitive or behavioural impairments should affect at least two of the following domains: memory, executive functions, visual-spatial skills, language and personality disorders, or behaviour with symptoms such as mood swings, agitation, apathy, disinterest, and social isolation.33 McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CRJr, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011;7(3):263-9.,55 Baird A, Samson S. Music and dementia. Prog Brain Res. 2015;217, 207-235.

Dementia usually occurs in people over 65 years of age. Age-related physical health problems such as diabetes and hypertension increase the risk of AD and VD. Cognitive reserve can be a protective factor for dementia while minimizing cognitive and functional decline. Factors that increase cognitive reserve such as physical exercise, intellectual stimulation, or lifelong leisure activities are associated with a reduced risk of dementia even in individuals with a genetic predisposition.22 Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017; 310:2673-4.,66 Johnson JK, Chow ML. Hearing and music in dementia. Handb Clin Neurol 2015;129:667-87.

National policies highlight the importance of early diagnosis, treatment, and social inclusion to maintaining a good quality of life for people with dementia.77 Brasil (2006). Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Atenção Básica. Envelhecimento e saúde da pessoa idosa- Brasília:Ministério da Saúde 2006;(19) 192 p. il. - (Série A. Normas e Manuais Técnicos). Population studies and international epidemiologic consortia have been investigating the clinical diagnosis of dementia and, dementia of the Alzheimer type has well-established diagnostic criteria for epidemiologic research.88 Sacuiu SF. Dementias. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;138:123-51. First-line treatment options often involve drugs to slow the progression of the disease and antipsychotic medications to treat behavioural disorders.11 Blackburn R, Bradshaw T. Music therapy for service users with dementia: A critical review of the literature. J Psychiatri Ment Health Nurs. 2014;21(10):879-88.,22 Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017; 310:2673-4. Individual strategies in choosing the appropriate dementia medication are highly recommended due to the individual course of the disease and different response to the drugs and their adverse effects.88 Sacuiu SF. Dementias. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;138:123-51. Music therapy is a non-pharmacological treatment that seeks to minimize symptoms.99 Vale FAC, Neto YC, Bertolucci PHF, Machado JCB, Silva DJ, Allam N, et al. Treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Dement Neuropsychol. 2011; 5(Suppl 1):34-48. Musical interventions are also used by numerous health professionals in patients with AD.1010 Moussard A, Bigand E, Belleville S, Peretz I. Music as a mnemonic to learn gesture sequences in normal aging and Alzheimer's disease. Front Hum Neurosci 2014;12;8:294.,1111 Simmons-Stern NR, Deason RG, Brandler BJ, Frustace BS, O'Connor MK, Ally BA, et al. Music-based memory enhancement in Alzheimer's disease:Promise and limitations. Neuropsychologia, 2012 50(14): 3295-303.

Media interest in this treatment approach has contributed to the public perception that musical abilities represent an “island of preservation” in cognitively impaired people with AD. This intervention can be considered less harmful than pharmacological treatments to improve cognitive functions, mood, and quality of life of these patients.1212 Arroyo-Anlló EM, Díaz JP, Gil R. Familiar music as an enhancer of self-consciousness in patients with Alzheimer's Disease. Biomed Research International 2013:1-10. When music is used acting as therapy, music performs the primary role in the intervention while the therapist is secondary; when music is used in therapy, the therapist takes the primary role and music is secondary.1313 Bruscia KE. Defining music therapy (3rd ed.) University Park, IL; Barcelona Publishers. 2014. A music therapist is a qualified professional with the capacity to develop musical interventions adapted to the patient’s experiences and illness. Neuromusical therapy, is a clinical intervention modality of music therapy that acts to promote cognitive rehabilitation of neurological patients.1414 Alcântara-Silva TRM, Miotto EC, Moreira SV. Musicoterapia, reabilitação cognitiva e doença de Alzheimer:revisão sistemática. Rev Bras Musicoter. 2014;17:56-68.,1515 Moreira SV, Alcântara-Silva TRM, Silva DJ, Moreira MA. Neuromusicoterapia no Brasil:aspectos terapêuticos na reabilitação neurológica. Rev Bras Musicoter. 2012;12:18-26.

Studies with musical intervention have demonstrated the efficacy of treatment for the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia, such as agitation, irritability, depression, and apathy.1616 Arroyo-Anlló EM, Díaz JP, Gil R. Familiar music as an enhancer of self-consciousness in patients with Alzheimer's Disease. Biomed Research International 2013:1-10.

17 Delphin-Combe F, Rouch I, Martin-Gaujard G, Relland S, Krolak-Salmon, P. Effect of a non-pharmacological intervention, Voix d'Or(®):on behavior disturbances in Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. Geriatr Psychol Neuropsychiatr Vieill. 2013;(3):323-30.

18 Eggert J, Dye CJ, Vincent E, Parker V, Daily SB, Pham, H, et al. Effects of viewing a preferred nature image and hearing preferred music on engagement, agitation, and mental status in persons with dementia. SAGE Open Medicine 2015;3: 205031211560257.

19 Fusar-Poli L, Bieleninik L, Brondino N, Chen, XJ, Gold C. The effect of music therapy on cognitive functions in patients with dementia:A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2017;10:1-10.

20 Guetin S, Portet F, Picot, MC, Pommie C, Messaoudi M, Djabelkir L, et al. Effect of music therapy on anxiety and depression in patients with Alzheimer's type dementia:Randomised, controlled study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;28(1):36-46.

21 Hailstone JC, Omar R, Warren JD. Relatively preserved knowledge of music in semantic dementia. J Neurol, Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(7):808-9.

22 Holmes C, Knights A, Dean C, Hodkinson S, Hopkins V. Keep music live:Music and the alleviation of apathy in dementia subjects. Int Psychogeriatr. 2006;18(4):623-30.

23 Hsu MH, Flowerdew R, Parker M, Fachner J, Odell-Miller H. Individual music therapy for managing neuropsychiatric symptoms for people with dementia and their carers:A cluster randomised controlled feasibility study. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:84.

24 Massimi M, Berry E, Browne G, Smyth G, Watson P, Baecker RM. An exploratory case study of the impact of ambient biographical displays on identity in a patient with Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2008;18(5-6):742-65.-2525 van der Steen JT, van Soest-Poortvliet, MC, van der Wouden, JC, Bruinsma, MS, Scholten, RJPM, Vink, AC. Music-based therapeutic interventions for people with dementia. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev.2017;5:CD003477. Other studies have investigated the role of music in cognition. In addition, music practice compensates for age-related declines in processing speed, memory, and cognition.1111 Simmons-Stern NR, Deason RG, Brandler BJ, Frustace BS, O'Connor MK, Ally BA, et al. Music-based memory enhancement in Alzheimer's disease:Promise and limitations. Neuropsychologia, 2012 50(14): 3295-303.,2626 Gallego MG, García JG. Music therapy and Alzheimer's disease: Cognitive, psychological, and behavioural effects. Neurología 2017;32(5): 300-8.,2727 Ragot R, Ferrandez AM, Pouthas V. Time, music, and aging. Psychomusicology 2002; 18(1-2):28-45. However, there is a lack of randomized clinical trials in the area, and in a recent Cochrane meta-analysis2525 van der Steen JT, van Soest-Poortvliet, MC, van der Wouden, JC, Bruinsma, MS, Scholten, RJPM, Vink, AC. Music-based therapeutic interventions for people with dementia. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev.2017;5:CD003477. on musical interventions in people with dementia, six articles were found with a total of 257 participants, and there was little effect of treatment on general cognition.

In AD, the ability to recognize music remains relatively preserved,2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50. and patients’ musical memory can be spared, particularly at the onset of the disease.2929 Basaglia-Pappas S, Laterza M, Borg C, Richard-Mornas A, Favre E, Thomas-Antérion C. Exploration of verbal and non-verbal semantic knowledge and autobiographical memories starting from popular songs in Alzheimer's disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25(5):785-95. The human memory system involves a process of coding, storing, and retrieving information.3030 Baddeley A, Anderson MC, Eysenck MW. Memory. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2011. Musical memory can be defined as the neural coding of musical experiences,3131 Jacobsen JH, Stelzer J, Fritz TH, Chételat G, La Joie R, Turner R. Why musical memory can be preserved in advanced Alzheimer's disease. Brain 2015;138(8):2438-50. the storage of these experiences, and the subsequent recall of this information. A study by Jacobsen et al. (2015)3131 Jacobsen JH, Stelzer J, Fritz TH, Chételat G, La Joie R, Turner R. Why musical memory can be preserved in advanced Alzheimer's disease. Brain 2015;138(8):2438-50. involving AD and music indicated a greater preservation of brain areas involved in the processing of music. The authors found that musical memory seems to be partially independent of other memory systems, and in AD, musical memory may be partially preserved. Neural mechanisms and substrates of musical memory involve different anatomical brain networks. Different aspects of musical memory may remain intact while brain anatomy and cognitive functions are impaired.3131 Jacobsen JH, Stelzer J, Fritz TH, Chételat G, La Joie R, Turner R. Why musical memory can be preserved in advanced Alzheimer's disease. Brain 2015;138(8):2438-50. In addition, regions related to musical memory such as the caudal anterior cingulate cortex and the supplemental motor area showed a minimal level of cortical atrophy and disruption of glucose metabolism compared to the rest of the brain. Therefore, β-amyloid deposition in these regions is at an early stage in the expected course of the development of biomarkers for AD and is relatively well preserved. These results may explain the surprising preservation of musical memory in AD.

Recognizing that musical coding may serve as a mnemonic aid in AD, it is important to review the results of studies that used musical intervention in patients with AD to assess whether these therapeutic modalities were effective in assisting memory. To analyse this question, the authors performed a systematic review focusing on randomized trials.

METHODS

A search for articles was performed using Boolean operators (“and” and “or”), truncations (music *, Alzheimer * and random *), and the words “music therapy”, “memory”, “cognition”, “Alzheimer disease”, “Randomized Controlled Trial”, and “Controlled Clinical Trial.” We found 42 articles on PubMed (Medline), The Cochrane Library, PsycINFO and Virtual Library (VHL) indexes up to June 2017. We undertook a comprehensive review based on Cochrane protocols.3232 Green S, Higgins J, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from handbook.cochrane.org.

handbook.cochrane.org...

We excluded 18 articles duplicated in different indexes, giving 24 articles (Table 1).

The selected studies included patients diagnosed with mild or moderate AD who underwent musical intervention with music therapy or with music for memory improvement. The musical interventions were conducted by a trained and qualified professional. The study design was a randomized clinical trial. Studies written in English, Portuguese, or Spanish were selected.

Of the 24 articles found, 20 were excluded. We found four review articles3333 Di Santo SG, Prinelli F, Adorni F, Caltagirone C, Musicco M. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine, and memantine in relation to severity of Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;35(2):349-61.

34 Musicco M, Pettenati, C, Caltagirone C. Variability of efficacy measures in Alzheimer's disease. Ann Ist Super Sanita 2005;41(1):87-91.

35 Samson S, Clément S, Narme P, Schiaratura L, Ehrlé N. Efficacy of musical interventions in dementia:Methodological requirements of nonpharmacological trials. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1337(1):249-55.-3636 Särkämö T, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, Rantanen P. clinical and demographic factors associated with the cognitive and emotional efficacy of regular musical activities in dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;49(3):767-81. and an article that used the same population of patients with different methods of analysis.3636 Särkämö T, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, Rantanen P. clinical and demographic factors associated with the cognitive and emotional efficacy of regular musical activities in dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;49(3):767-81.

Of the 15 remaining articles that were excluded, one article represented a study protocol.3737 ACTRN. Individual cognitive stimulation therapy for people with mild to moderate dementia. 2017;ACTRN12616000827437. Retrieved from http://www.anzctr.org.au/actrn12616000827437.aspx

http://www.anzctr.org.au/actrn1261600082...

Four articles did not evaluate patients with mild or moderate dementia, including the article by Innes et al.3838 Innes KE, Selfe TK, Khalsa DS, Kandati S, Huysmans Z. Meditation and music listening improve memory and cognitive function in adults with subjective cognitive decline:Randomized controlled trial. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(7):616-7. that evaluated patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI); Sánchez et al.,3939 Sánchez A, Maseda A, Marante-Moar MP, de Labra C, Lorenzo-López L, Millán-Calenti JC. Comparing the effects of multisensory stimulation and individualized music sessions on elderly people with severe dementia:A randomized controlled trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;52(1):303-15. who studied patients with severe dementia; and Satoh et al.4040 Satoh M, Ogawa JI, Tokita T, Nakaguchi N, Nakao K, Kida H, et al. The effects of physical exercise with music on cognitive function of elderly people: Mihama-Kiho Project. PLoS One 2014;9(4):e95230. (2014) and Tesky et al.,4141 Tesky VA, Thiel C, Banzer W, Pantel J. Effects of a group program to increase cognitive performance through cognitively stimulating leisure activities in healthy older subjects. GeroPsych 2011;24(2):83-92. who evaluated healthy elderly patients. Five papers did not assess memory but used primary measures of mood assessment in music interventions and patients with AD.4242 Hutson C, Orrell M, Dugmore O, Spector A. Sonas:A pilot study investigating the effectiveness of an intervention for people with moderate to severe dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;29(8):696-703.

43 Narme P, Clement S, Ehrle N, Schiaratura L, Vachez S, Courtaigne B, et al. Efficacy of musical interventions in dementia:Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;38(2):359-69.

44 Delphin-Combe F, Rouch I, Martin-Gaujard G, Relland S, Krolak-Salmon P. Effect of a non-pharmacological intervention, Voix d'Or(®):on behavior disturbances in Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. Geriatr Psychol Neuropsychiatr Vieill. 2013;11(3):323-30.

45 Guetin S, Portet F, Picot MC, Pommie C, Messaoudi M, Djabelkir L, et al. Effect of music therapy on anxiety and depression in patients with Alzheimer's type dementia:Randomised, controlled study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord.2009 28(1):36-46.-4646 Ballard C, Brown R, Fossey J, Douglas S, Bradley P, Hancock J, et al. Brief psychosocial therapy for the treatment of agitation in Alzheimer disease (The CALM-AD Trial). Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2009;17(9): 726-33. Three studies were not controlled and randomized.4747 Chikamori F, Kuniyoshi N, Shibuya S, Takase Y. Perioperative music therapy with a key-lighting keyboard system in elderly patients undergoing digestive tract surgery. Hepatogastroenterology 2004;51(59): 1384-6.

48 Suzuki M, Kanamori M, Watanabe M, Nagasawa S, Kojima E, Ooshiro H, et al. Behavioral and endocrinological evaluation of music therapy for elderly patients with dementia. Nurs Health Sci 2004;6(1):11-8.-4949 Requena C, López MI, Maestú F, Campo P, López IJ, Ortiz T. Effects of cholinergic drugs and cognitive training on dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2004;18(1):50-4. The study by Lyu et al.5050 Lyu J, Gao T, Li M, Xie L, Li W, Jin W, et al. The effect of music therapy on memory, language and psychological symptoms of patients with mild Alzheimer's disease. Chinese Journal of Neurology 2014;47(12):831-83. aimed to evaluate the effect of music therapy on language, memory, and psychological symptoms in patients with mild AD, but was excluded because it was originally written in Chinese. The article by Goudour et al.5151 Goudour A, Samson S, Bakchine S, Ehrle N. Semantic memory training in Alzheimer's disease. Geriatr Psychol Neuropsychiatr Vieill.2011;9(2): 237-47. used categories of musical instruments versus categories of human actions to evaluate semantic memory but did not use musical activities.

A flow diagram for the selection procedure is presented in Figure 1. The research design, intervention applied, intervention time, sample size, and evaluations of the studies eligible for analysis are shown in Table 2.

RESULTS

In a crossover, multicentre, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study, Han et al.5252 Han JW, Lee H, Hong JW, Kim K, Kim T, Byun HJ, et al. Multimodal cognitive enhancement therapy for patients with mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia:A multi- center, randomized, controlled, double-blind, crossover trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;55(2):787-96. evaluated 64 elderly participants with MCI or mild dementia (patients with AD, VD, or FTD), with a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) between 0.5 and 1, and who underwent Multimodal Cognitive Enhancement Therapy (MCET), which included a music therapy programme. The study compared this modality of therapy with a simulation therapy called Mock therapy that consisted of the same intervention time but with daily leisure activities. Primary assessment measures included the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale (Cognitive Subscale - ADAS-Cog) to examine the effects of treatment on cognitive function. As a secondary assessment measure, the Revised Memory and Behavioural Problems Checklist (RMBPC) was used to evaluate psychological and behavioural symptoms. The RMBPC provides two types of indexes, i.e., frequencies of problem behaviours in patients with dementia (Revised Memory and Behaviour Problems Checklist (RMBPC-F)) and caregiver reactions to these behaviours (Revised Memory and Behaviour Problems Checklist Reaction (RMBPC-R)). Each index consists of three subcategories, including memory related to problems, depression, and disruption. The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) was used to measure the severity of depressed mood, and the Disability Dementia Rating (DDR) was used to measure functional abilities including Daily Living and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (ADL/IADL). Finally, Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease (QoL-AD) was evaluated. MCET treatment was effective in improving the measures of global cognition (MMSE and ADAS-Cog) and promoted improvements in the RMBPC-F scores. However, no significant differences in the RMBPC-R were identified. The authors concluded that the MCET programme improved global cognition, psychological and behavioural symptoms, and quality of life in people with MCI or mild dementia, suggesting improvements of the activities employed in the care of patients with dementia in South Korea. Notably, the intervention did not affect any specific measure of memory present in the RMBPC-F or RMBPC-R; therefore, it is unlikely that the improvement in MMSE score was due to an effect of MCET on memory. Finally, another important aspect to consider is that musical stimulation was not the main component of the MCET, which was limited to only one hour of musical stimulation per week.

In Särkämö et al.,2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50. the authors trained caregivers to perform daily musical interventions in patients with dementia. Eighty-nine pairs for a total of 178 people, including 89 patients with dementia and 89 caregivers (59 family members and 30 nurses) divided into six blocks, were randomized into three groups of 10 weeks of training and followed up for nine months. The groups participated in singing activities involving familiar songs and occasional vocal exercises and rhythmic movements (n = 30), listening to familiar songs and discussions (n = 29), usual treatment (n = 30), and regular musical exercises at home. The hypothesis was that regular singing would be effective for reinforcing cognitive domains such as attention and working memory and would be beneficial to mood and quality of life. Eighty-four dyads (patient and caregiver) completed the study. All participants underwent a 1.5-hour neuropsychological evaluation that included eight cognitive domains: general cognition (MMSE); orientation (MMSE/Orientation); working memory (MMSE/memory, Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS)-III/Digit span and logical memory); executive function (MMSE/calculation, FAS); long-term memory (WMS-III/logical memory and Consortium to a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease Battery (CERAD)/word list); executive function (MMSE/calculus and FAS); verbal skills (MMSE/verbal items, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III (WAIS-III)/Similarities, CERAD/Verbal Fluency, Boston Naming Test, Aphasia Battery (Western Aphasia Battery WAB/sequential commands)); and visuospatial skills (MMSE/copy, WAIS-III/drawing, trails (Trail Making Test TMT/part A). Behaviours such as depression (Cornell-Brown Scale), quality of life (QoL-AD), and caregiver evaluation (Zarit Burden Interview-ZBI and the caregiver’s General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)) were assessed.

The evaluations in the study by Särkämö et al.2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50. occurred before and after the 10-week intervention period and again six months after the intervention. Compared to usual care, singing and listening to music daily improved overall cognition, orientation, attention, executive function, and mood. Concerning memory, the group that engaged in musical activities with singing had better working memory immediately after the intervention than the other groups, but this effect did not persist in the long term (six months later). Because there was a correlation between the frequency of musical activities run by the caregivers in the home and the working memory score six months after the training, it is possible that continuous musical stimulation is necessary to maintain the gains in working memory. With regard to long-term memory, it is important to note that six months after the training, the groups that engaged in some musical activity had a better autobiographical memory for people known in their childhood than the group that was not involved in musical activities.

In 2012, Ceccato et al.5353 Ceccato E, Vigato G, Bonetto C, Bevilacqua A, Pizziolo P, Crociani S, et al. STAM protocol in dementia:A multicenter, single-blind, randomized, and controlled trial. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012;27(5): 301-10. used a music therapy protocol designed for cognitive rehabilitation: the Sound Training for Attention and Memory (STAM-Dem). This multicenter, randomized, controlled, univariate study evaluated the effectiveness of music training in cognitive abilities (attention, memory, and executive function) and behavioural symptoms such as depressive and aggressive states in 51 patients diagnosed with dementia who underwent treatment in different centres in Italy. Their cognitive functions were evaluated using a psychometric battery that included the MMSE, the Attention Matrix, the WMS-III/Digits span, the Immediate Prose Memory Test (MPI), and the Deferred Prose Memory Test (MPD). To assess mood, the GDS was applied, and aggressiveness was measured using the Cohen Mansfield Agitation Inventory. The nurses evaluated the instrumental activities of daily living using the Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living. The music therapists used two evaluation protocols, namely, the Geriatric Music Therapy Profile (GMP), which evaluated patient competences in the music field, and the Music Therapy Activity Scale (SVAM), which comprises a set of 50 items that explore various aspects of the musical relationship. In this study, a positive effect of the intervention on visual selective attention and verbal episodic memory in the experimental group was observed, indicating that the STAM-Dem protocol can be useful and effective for reactivating functions with cognitive impairment in dementia patients.

Lord and Garner5454 Lord TR, Garner JE. Effects of music on Alzheimer patients. Percept Mot Skills 1993;76(2):451-5. randomly selected 60 patients diagnosed with AD from a population of 200 patients in a nursing home. The patients were separated non-systematically into three groups, first dividing the women and then the men. The groups consisted of 14 women and six men who participated in different interventions: one group listened to and played American songs of the 1920s and 1930s; another group participated in jigsaw exercises; and the third group participated in usual recreational activities such as drawing, painting, and watching TV. Initially, a questionnaire was developed by the nursing home and researcher in which the questions were based on a list of American Medical Association questions suggested for patients suspected of AD. The questionnaire was administered orally to each participant by the institution’s Director of Nursing, with general information questions that included date, age, sex, and educational level. In addition, questions were asked to evaluate the memory of past personal facts such as, “Where were you born?” and “What was your mother’s name?”. A second portion of the questionnaire assessed patient disposition and social cohesion. A focused observation of 30 seconds was made of the participants for three periods during each activity in the first two weeks of the study, resulting in 36 observations for each patient. During this time, an evaluator (one of the authors) observed the patient’s mood along with their interactive and collaborative propensity on a four-point scale from bad to excellent (zero to four points, respectively). The analysis of the pre-intervention questionnaire showed that there was no significant difference among the groups. Patients received six 30-minute intervention sessions per week for six months. The group that listened to music daily had a greater memory for facts related to their personal history compared to the other groups.

DISCUSSION

In total, 258 people participated in the studies and were randomly allocated to the control group or experimental group. A positive aspect of the studies was the use of the randomization procedure, but the studies did not explain the type of relationship that the patients had with the evaluators and conductors of the therapy and intervention groups, or the relationship of the conductors of the intervention with the researcher. This is an important data point for the full understanding of the design of each study.

The mean age of the participants was 79.99 years. Only the study by Han et al.5252 Han JW, Lee H, Hong JW, Kim K, Kim T, Byun HJ, et al. Multimodal cognitive enhancement therapy for patients with mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia:A multi- center, randomized, controlled, double-blind, crossover trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;55(2):787-96. reported the educational level, with a mean of 8.06 years. In the study of Särkämö et al.,2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50. a Likert scale was used to index education in which a score of one corresponded to primary education and seven corresponded to doctoral level, with an average of three points for the singing and control groups and of 2.8 points for the group listening to music. Thus, it was not possible to estimate the educational level of the sample in years. Reporting the level of education in studies is critical because it has been shown in the study by Livingston et al.22 Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017; 310:2673-4. that cognitive resilience in adulthood is likely to be increased through education and other intellectual stimuli. In addition, this author stated that lower rates of late dementia are associated with higher education.

The majority of the study participants were women (70.54%). All studies used music therapy or music as a form of intervention. However, one study used music therapy within a broader intervention programme.5252 Han JW, Lee H, Hong JW, Kim K, Kim T, Byun HJ, et al. Multimodal cognitive enhancement therapy for patients with mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia:A multi- center, randomized, controlled, double-blind, crossover trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;55(2):787-96. The time of intervention varied between the studies2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50.,4848 Suzuki M, Kanamori M, Watanabe M, Nagasawa S, Kojima E, Ooshiro H, et al. Behavioral and endocrinological evaluation of music therapy for elderly patients with dementia. Nurs Health Sci 2004;6(1):11-8.

49 Requena C, López MI, Maestú F, Campo P, López IJ, Ortiz T. Effects of cholinergic drugs and cognitive training on dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2004;18(1):50-4.-5050 Lyu J, Gao T, Li M, Xie L, Li W, Jin W, et al. The effect of music therapy on memory, language and psychological symptoms of patients with mild Alzheimer's disease. Chinese Journal of Neurology 2014;47(12):831-83. from eight weeks to six months, with one to six sessions per week; the service time ranged from thirty minutes to one and a half hours per session. According to the Cochrane meta-analysis,2929 Basaglia-Pappas S, Laterza M, Borg C, Richard-Mornas A, Favre E, Thomas-Antérion C. Exploration of verbal and non-verbal semantic knowledge and autobiographical memories starting from popular songs in Alzheimer's disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25(5):785-95. the therapeutic effects based on music are evident after five sessions. Because all studies included in the present review had more than five therapy sessions, a possible lack of effect of musical intervention in these studies cannot be attributed to a limited intervention time.

Most of the studies used general cognitive screening assessments or tests for assessing specific cognitive abilities such as memory, attention and executive functions, language, and visuomotor skills. Multifunctional batteries were also used, such as measures for evaluations of functional abilities, behaviour, mood, and specific evaluation protocols in music therapy. A summary of the tests used in the studies is presented in Table 3.

The studies presented a heterogeneity of cognitive evaluations and different measures. Only the MMSE assessing general cognition was used in most studies. Different approaches to evaluation may make it difficult to detect the efficacy of the treatment outcome. To evaluate the patients, Sarkamö et al.2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50. used 13 different tests on the same day. This type of evaluation can cause stress or fatigue in patients with dementia and may influence the results. The cognitive evaluation performed in the study by Ceccato et al.5353 Ceccato E, Vigato G, Bonetto C, Bevilacqua A, Pizziolo P, Crociani S, et al. STAM protocol in dementia:A multicenter, single-blind, randomized, and controlled trial. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012;27(5): 301-10. evaluated all patients without differentiating the duration and type of dementia. The psychologists responsible for the evaluation encountered difficulties performing the neuropsychological evaluation due to deterioration caused by the dementia or to low levels of education. This evaluation lasted an hour and 15 minutes, in addition to other evaluations performed by nurses and music therapists. Lord and Garner5454 Lord TR, Garner JE. Effects of music on Alzheimer patients. Percept Mot Skills 1993;76(2):451-5. cited that patients had progressive AD by inferring that they had mild or moderate forms of AD. The authors did not perform conventional cognitive or behavioural assessments; instead, they used a questionnaire developed by the team involving questions from a list of the American Medical Association

The ageing process may be associated with cognitive disorders, and dementia may vary according to the clinical history and type of pathology. Dementia due to AD has the most frequent and well-established diagnostic criteria.33 McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CRJr, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011;7(3):263-9.,88 Sacuiu SF. Dementias. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;138:123-51. Therapies aimed at relieving symptoms should preferably begin early in the disease stage, when cognitive function is not severely impaired. A two-year delay in the onset of dementia, using predictions based on US incidence studies, could reduce the prevalence of dementia by 23%.88 Sacuiu SF. Dementias. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;138:123-51. However, most of the studies reviewed did not describe disease duration, stage of AD (mild, moderate, or severe) or even differentiate between types of dementias, which may have different prognoses. For example, Han et al.5252 Han JW, Lee H, Hong JW, Kim K, Kim T, Byun HJ, et al. Multimodal cognitive enhancement therapy for patients with mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia:A multi- center, randomized, controlled, double-blind, crossover trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;55(2):787-96. analysed MCI patients, who may be clinically identifiable with the initial neuropathological stages of dementia,88 Sacuiu SF. Dementias. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;138:123-51. patients with mild dementia, 28 patients with AD, three patients with VD, and one patient with FTD. Han et al.5252 Han JW, Lee H, Hong JW, Kim K, Kim T, Byun HJ, et al. Multimodal cognitive enhancement therapy for patients with mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia:A multi- center, randomized, controlled, double-blind, crossover trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;55(2):787-96. did not differentiate the analyses by pathology, that is, whether the MCI was amnesic or non-amnesic and whether the analysis differed for the different types of dementia. Conversely, Särkämö et al.2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50. reanalysed his data to study clinical and sociodemographic factors that can influence the effectiveness of musical interventions. The author noted in his study that the effectiveness of musical interventions and the outcome of rehabilitation are different for groups of patients with AD, VD, and FTD. The results indicated that the aetiology of dementia, severity, age, and care situations may mediate the cognitive and emotional efficacy of regular singing and/or listening to music. Thus, the heterogeneity of the measures used in the studies hampers comparison and the lack of data on the participants in some studies5353 Ceccato E, Vigato G, Bonetto C, Bevilacqua A, Pizziolo P, Crociani S, et al. STAM protocol in dementia:A multicenter, single-blind, randomized, and controlled trial. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012;27(5): 301-10.,5454 Lord TR, Garner JE. Effects of music on Alzheimer patients. Percept Mot Skills 1993;76(2):451-5. does not favour characterization of the sample. It is critical to the advancement of research in the area that basic data on participants such as dementia type, duration, severity of symptoms, and level of education are reported in all studies.

Treatment with music and/or music therapy was investigated in three studies2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50.,5353 Ceccato E, Vigato G, Bonetto C, Bevilacqua A, Pizziolo P, Crociani S, et al. STAM protocol in dementia:A multicenter, single-blind, randomized, and controlled trial. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012;27(5): 301-10.,5454 Lord TR, Garner JE. Effects of music on Alzheimer patients. Percept Mot Skills 1993;76(2):451-5. and music therapy integrated into rehabilitation programmes was addressed in one study.5252 Han JW, Lee H, Hong JW, Kim K, Kim T, Byun HJ, et al. Multimodal cognitive enhancement therapy for patients with mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia:A multi- center, randomized, controlled, double-blind, crossover trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;55(2):787-96. In the study by Han et al.,5252 Han JW, Lee H, Hong JW, Kim K, Kim T, Byun HJ, et al. Multimodal cognitive enhancement therapy for patients with mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia:A multi- center, randomized, controlled, double-blind, crossover trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;55(2):787-96. we cannot conclude that there was improvement solely due to musical interventions since the MCET programme includes other forms of therapy such as cognitive training, cognitive stimuli, reality orientation, and physiotherapy and reminiscence therapy; music therapy was used only once per week for 60 minutes. In addition, in the study by Han et al.,5252 Han JW, Lee H, Hong JW, Kim K, Kim T, Byun HJ, et al. Multimodal cognitive enhancement therapy for patients with mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia:A multi- center, randomized, controlled, double-blind, crossover trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;55(2):787-96. the type of musical activity used was not specified; therefore, it is difficult to attribute any specific effect to use of the musical activities. The study by Ceccato et al.5353 Ceccato E, Vigato G, Bonetto C, Bevilacqua A, Pizziolo P, Crociani S, et al. STAM protocol in dementia:A multicenter, single-blind, randomized, and controlled trial. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012;27(5): 301-10. used a music training programme, STAM-Dem, which consists of a progressive series of song sessions used in a sequence of step-by-step exercises to stimulate attention and memory. The other studies used singing and listening in a freer way,2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50.,5454 Lord TR, Garner JE. Effects of music on Alzheimer patients. Percept Mot Skills 1993;76(2):451-5. and Särkämö et al.2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50. used popular songs from 1920 to 1960, whereas Lord and Garner5454 Lord TR, Garner JE. Effects of music on Alzheimer patients. Percept Mot Skills 1993;76(2):451-5. used songs from the 1920s and 1930s when ‘Big Bands’ played on a daily basis. Music therapy is a systematic intervention process that uses different techniques ranging from passive to active musical activities. In this respect, it is important to consider that there is also substantial heterogeneity in the musical intervention, ranging from musical listening techniques to a more systematic use of musical activities with stimulation objectives. Therefore, the effectiveness of the intervention may vary according to the quality of the musical intervention offered.

At this juncture, it is time to consider the main question that guided this systematic review: do musical interventions have an effect on memory in people with dementia? A first point to consider is that the study by Han et al.5252 Han JW, Lee H, Hong JW, Kim K, Kim T, Byun HJ, et al. Multimodal cognitive enhancement therapy for patients with mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia:A multi- center, randomized, controlled, double-blind, crossover trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;55(2):787-96. does not elucidate this issue because the musical intervention comprised only a part of a broad investigation protocol, thereby precluding inference on any specific effect of the musical intervention in the study. In addition, in the Han et al. study, no effect of the intervention on memory was observed. In other studies, the use of music was the core part of the intervention and involved the use of musical listening, which ranged from listening and singing known songs2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50.,5454 Lord TR, Garner JE. Effects of music on Alzheimer patients. Percept Mot Skills 1993;76(2):451-5. to a systematic use of music with the purpose of cognitive stimulation.5353 Ceccato E, Vigato G, Bonetto C, Bevilacqua A, Pizziolo P, Crociani S, et al. STAM protocol in dementia:A multicenter, single-blind, randomized, and controlled trial. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012;27(5): 301-10. In all these studies, the musical intervention had some effect on memory. The questions that arise are as follows: was this effect consistent? What type of memory is most benefited by the intervention?

With regard to working memory or short-term memory, both Ceccato et al.5353 Ceccato E, Vigato G, Bonetto C, Bevilacqua A, Pizziolo P, Crociani S, et al. STAM protocol in dementia:A multicenter, single-blind, randomized, and controlled trial. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012;27(5): 301-10. and Särkämö et al.2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50. used comparable measures of this construct, such as the digit span tasks in direct and inverse order. In this case, the results of the two studies can be considered conflicting in that Särkämö et al.2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50. reported a positive effect of musical intervention on working memory, whereas Ceccato et al. (2012) reported no statistically significant difference between the experimental group and the control group. However, it is important to note that even in the study by Särkämö et al.,2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50. the effect on working memory was limited and did not persist in a further evaluation six months after the intervention. Another aspect to consider is that, in its reanalysis of data, Särkämö et al.2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50. reported that the effect on working memory was moderated by the degree of dementia and was higher in people with mild dementia. Because Ceccato et al.5353 Ceccato E, Vigato G, Bonetto C, Bevilacqua A, Pizziolo P, Crociani S, et al. STAM protocol in dementia:A multicenter, single-blind, randomized, and controlled trial. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012;27(5): 301-10. did not report the degree of dementia of their participants, it is not possible to ascertain whether the difference in the outcome of the studies can be attributed to this factor.

Another measure of memory that can be regarded as comparable between the studies by Ceccato et al.5353 Ceccato E, Vigato G, Bonetto C, Bevilacqua A, Pizziolo P, Crociani S, et al. STAM protocol in dementia:A multicenter, single-blind, randomized, and controlled trial. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012;27(5): 301-10. and Särkämö et al.2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50. is the measure of long-term verbal memory. Both studies included measures that asked participants to repeat a verbally presented passage of text after a time interval ranging from 10 to 20 minutes (the MPD test was used in the study by Ceccato et al.,5353 Ceccato E, Vigato G, Bonetto C, Bevilacqua A, Pizziolo P, Crociani S, et al. STAM protocol in dementia:A multicenter, single-blind, randomized, and controlled trial. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012;27(5): 301-10. and the Logic Memory II test of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale was used in the study by Särkämö et al.).2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50. Again, the results obtained are conflicting between the two studies: this time, the study of Ceccato et al.5353 Ceccato E, Vigato G, Bonetto C, Bevilacqua A, Pizziolo P, Crociani S, et al. STAM protocol in dementia:A multicenter, single-blind, randomized, and controlled trial. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012;27(5): 301-10. reported a positive effect of musical intervention; however, this effect was not statistically significant in the study by Särkämö et al.2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50. A possible explanation for this disparity in results may be due to the task employed by Särkämö et al.2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50. (20 minutes versus 10 minutes in the task of Ceccato et al.)5353 Ceccato E, Vigato G, Bonetto C, Bevilacqua A, Pizziolo P, Crociani S, et al. STAM protocol in dementia:A multicenter, single-blind, randomized, and controlled trial. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012;27(5): 301-10. between the study phase and the test phase. This interval may have contributed to a floor effect on the task. After all, if we examine the long-term memory measure (Delayed Memory) in Särkämö et al.,2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50. it can be observed that the task-weighted average amongst the three study groups was only three points out of a total of 35.

Finally, both the study by Lord and Garner and the study by Särkämö et al.2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50. used measures of memory that can be considered to evaluate the autobiographical memory. Both studies used musical listening and observed an effect of this intervention on autobiographical memory. More specifically, in the study by Särkämö et al.,2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50. both the people in the group who only listened to music and the singing group remembered more about the names of people they had known in childhood than the people in the control group. In Lord and Garner’s5454 Lord TR, Garner JE. Effects of music on Alzheimer patients. Percept Mot Skills 1993;76(2):451-5. study, the participants in the group who listened to and sang songs exhibited better recall of facts related to their personal history than the participants in the two control groups. Thus, the two studies that used more specific measures of autobiographical memory had compatible results. An important fact to consider is that in the reanalysis of Särkämö et al.,2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50. the effect of musical intervention on autobiographical memory was not moderated by any sociodemographic variable, and this is an indication that the effect of musical intervention on this type of memory may be more robust and generalized than other types of memory.

In short, it remains unclear whether musical intervention has an effect on memory, particularly short-term memory and long-term verbal memory, for which conflicting results have been observed.2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50.,5353 Ceccato E, Vigato G, Bonetto C, Bevilacqua A, Pizziolo P, Crociani S, et al. STAM protocol in dementia:A multicenter, single-blind, randomized, and controlled trial. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012;27(5): 301-10. The most promising results appear to involve autobiographical memory, in which the two studies that more directly investigated this construct reported positive effects of musical intervention on autobiographical memory.2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50.,5454 Lord TR, Garner JE. Effects of music on Alzheimer patients. Percept Mot Skills 1993;76(2):451-5. Another positive aspect is that it seems to have made no difference, as far as the effects on memory are concerned, whether the musical intervention was more systematically applied from an intervention programme5353 Ceccato E, Vigato G, Bonetto C, Bevilacqua A, Pizziolo P, Crociani S, et al. STAM protocol in dementia:A multicenter, single-blind, randomized, and controlled trial. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012;27(5): 301-10. or performed from listening.2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50.,5454 Lord TR, Garner JE. Effects of music on Alzheimer patients. Percept Mot Skills 1993;76(2):451-5. This is an important point because listening activities or even singing activities are more accessible and can be stimulated in the home by the relatives and caregivers of people with dementia, resulting in a great possibility of preventive activity.

In conclusion, this systematic review aimed to analyse how musical intervention can affect the memory of patients with AD. This is the first review study found in the literature that has this objective. This review demonstrates that there are few randomized studies as of the date of publication. Most of the articles have been published recently, that is, in the last 3 years, which indicates the concern with this type of treatment in the last decade, possibly due to the increase in patients diagnosed with AD in the world population. The articles were published in different countries, including Korea, Finland, Italy, and the USA, but no research was found in Brazil.

The results found in the articles demonstrated that musical intervention may be effective in the treatment of patients with AD. However, the available evidence is still insufficient due to the small number of randomized scientific studies that evaluated memory in patients undergoing music treatment. Despite the limited evidence, it is important to conduct studies with musical interventions supporting the use of music in the complementary treatment for elderly people with dementia due to AD evaluating the impact on cognitive functions and different types of memory. Providing care and rehabilitation for people with AD has become a major challenge for the public health system and for society.2828 Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50. Future studies are necessary with better characterized samples, particularly in terms of the etiology of dementia, duration and severity of symptoms, and the educational level of participants. In addition, the type of musical intervention used should be better described, and sensitive measures of the different types of memory must be included since this is not a unitary construct.

-

1

This study was conducted at Department of Psychology, Institute of Human Sciences, Federal University of Juiz de Fora, MG, Brazil.

Acknowledgments.

The author(s) disclose receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: this study was supported by a CAPES scholarship during SVM´s doctorate degree in Psychology at the UFJF.

REFERENCES

-

1Blackburn R, Bradshaw T. Music therapy for service users with dementia: A critical review of the literature. J Psychiatri Ment Health Nurs. 2014;21(10):879-88.

-

2Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017; 310:2673-4.

-

3McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CRJr, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011;7(3):263-9.

-

4Schlindwein-Zanini R. Dementia in the elderly:Neuropsychological aspects. Rev Neurosci 2010;18(2):220-6.

-

5Baird A, Samson S. Music and dementia. Prog Brain Res. 2015;217, 207-235.

-

6Johnson JK, Chow ML. Hearing and music in dementia. Handb Clin Neurol 2015;129:667-87.

-

7Brasil (2006). Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Atenção Básica. Envelhecimento e saúde da pessoa idosa- Brasília:Ministério da Saúde 2006;(19) 192 p. il. - (Série A. Normas e Manuais Técnicos).

-

8Sacuiu SF. Dementias. Handb Clin Neurol. 2016;138:123-51.

-

9Vale FAC, Neto YC, Bertolucci PHF, Machado JCB, Silva DJ, Allam N, et al. Treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Dement Neuropsychol. 2011; 5(Suppl 1):34-48.

-

10Moussard A, Bigand E, Belleville S, Peretz I. Music as a mnemonic to learn gesture sequences in normal aging and Alzheimer's disease. Front Hum Neurosci 2014;12;8:294.

-

11Simmons-Stern NR, Deason RG, Brandler BJ, Frustace BS, O'Connor MK, Ally BA, et al. Music-based memory enhancement in Alzheimer's disease:Promise and limitations. Neuropsychologia, 2012 50(14): 3295-303.

-

12Arroyo-Anlló EM, Díaz JP, Gil R. Familiar music as an enhancer of self-consciousness in patients with Alzheimer's Disease. Biomed Research International 2013:1-10.

-

13Bruscia KE. Defining music therapy (3rd ed.) University Park, IL; Barcelona Publishers. 2014.

-

14Alcântara-Silva TRM, Miotto EC, Moreira SV. Musicoterapia, reabilitação cognitiva e doença de Alzheimer:revisão sistemática. Rev Bras Musicoter. 2014;17:56-68.

-

15Moreira SV, Alcântara-Silva TRM, Silva DJ, Moreira MA. Neuromusicoterapia no Brasil:aspectos terapêuticos na reabilitação neurológica. Rev Bras Musicoter. 2012;12:18-26.

-

16Arroyo-Anlló EM, Díaz JP, Gil R. Familiar music as an enhancer of self-consciousness in patients with Alzheimer's Disease. Biomed Research International 2013:1-10.

-

17Delphin-Combe F, Rouch I, Martin-Gaujard G, Relland S, Krolak-Salmon, P. Effect of a non-pharmacological intervention, Voix d'Or(®):on behavior disturbances in Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. Geriatr Psychol Neuropsychiatr Vieill. 2013;(3):323-30.

-

18Eggert J, Dye CJ, Vincent E, Parker V, Daily SB, Pham, H, et al. Effects of viewing a preferred nature image and hearing preferred music on engagement, agitation, and mental status in persons with dementia. SAGE Open Medicine 2015;3: 205031211560257.

-

19Fusar-Poli L, Bieleninik L, Brondino N, Chen, XJ, Gold C. The effect of music therapy on cognitive functions in patients with dementia:A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2017;10:1-10.

-

20Guetin S, Portet F, Picot, MC, Pommie C, Messaoudi M, Djabelkir L, et al. Effect of music therapy on anxiety and depression in patients with Alzheimer's type dementia:Randomised, controlled study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;28(1):36-46.

-

21Hailstone JC, Omar R, Warren JD. Relatively preserved knowledge of music in semantic dementia. J Neurol, Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(7):808-9.

-

22Holmes C, Knights A, Dean C, Hodkinson S, Hopkins V. Keep music live:Music and the alleviation of apathy in dementia subjects. Int Psychogeriatr. 2006;18(4):623-30.

-

23Hsu MH, Flowerdew R, Parker M, Fachner J, Odell-Miller H. Individual music therapy for managing neuropsychiatric symptoms for people with dementia and their carers:A cluster randomised controlled feasibility study. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:84.

-

24Massimi M, Berry E, Browne G, Smyth G, Watson P, Baecker RM. An exploratory case study of the impact of ambient biographical displays on identity in a patient with Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2008;18(5-6):742-65.

-

25van der Steen JT, van Soest-Poortvliet, MC, van der Wouden, JC, Bruinsma, MS, Scholten, RJPM, Vink, AC. Music-based therapeutic interventions for people with dementia. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev.2017;5:CD003477.

-

26Gallego MG, García JG. Music therapy and Alzheimer's disease: Cognitive, psychological, and behavioural effects. Neurología 2017;32(5): 300-8.

-

27Ragot R, Ferrandez AM, Pouthas V. Time, music, and aging. Psychomusicology 2002; 18(1-2):28-45.

-

28Särkämö T, Tervaniemi M, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia:Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014;54(4):634-50.

-

29Basaglia-Pappas S, Laterza M, Borg C, Richard-Mornas A, Favre E, Thomas-Antérion C. Exploration of verbal and non-verbal semantic knowledge and autobiographical memories starting from popular songs in Alzheimer's disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25(5):785-95.

-

30Baddeley A, Anderson MC, Eysenck MW. Memory. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2011.

-

31Jacobsen JH, Stelzer J, Fritz TH, Chételat G, La Joie R, Turner R. Why musical memory can be preserved in advanced Alzheimer's disease. Brain 2015;138(8):2438-50.

-

32Green S, Higgins J, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from handbook.cochrane.org

» handbook.cochrane.org -

33Di Santo SG, Prinelli F, Adorni F, Caltagirone C, Musicco M. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine, and memantine in relation to severity of Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;35(2):349-61.

-

34Musicco M, Pettenati, C, Caltagirone C. Variability of efficacy measures in Alzheimer's disease. Ann Ist Super Sanita 2005;41(1):87-91.

-

35Samson S, Clément S, Narme P, Schiaratura L, Ehrlé N. Efficacy of musical interventions in dementia:Methodological requirements of nonpharmacological trials. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1337(1):249-55.

-

36Särkämö T, Laitinen S, Numminen A, Kurki M, Johnson JK, Rantanen P. clinical and demographic factors associated with the cognitive and emotional efficacy of regular musical activities in dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;49(3):767-81.

-

37ACTRN. Individual cognitive stimulation therapy for people with mild to moderate dementia. 2017;ACTRN12616000827437. Retrieved from http://www.anzctr.org.au/actrn12616000827437.aspx

» http://www.anzctr.org.au/actrn12616000827437.aspx -

38Innes KE, Selfe TK, Khalsa DS, Kandati S, Huysmans Z. Meditation and music listening improve memory and cognitive function in adults with subjective cognitive decline:Randomized controlled trial. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(7):616-7.

-

39Sánchez A, Maseda A, Marante-Moar MP, de Labra C, Lorenzo-López L, Millán-Calenti JC. Comparing the effects of multisensory stimulation and individualized music sessions on elderly people with severe dementia:A randomized controlled trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;52(1):303-15.

-

40Satoh M, Ogawa JI, Tokita T, Nakaguchi N, Nakao K, Kida H, et al. The effects of physical exercise with music on cognitive function of elderly people: Mihama-Kiho Project. PLoS One 2014;9(4):e95230.

-

41Tesky VA, Thiel C, Banzer W, Pantel J. Effects of a group program to increase cognitive performance through cognitively stimulating leisure activities in healthy older subjects. GeroPsych 2011;24(2):83-92.

-

42Hutson C, Orrell M, Dugmore O, Spector A. Sonas:A pilot study investigating the effectiveness of an intervention for people with moderate to severe dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;29(8):696-703.

-

43Narme P, Clement S, Ehrle N, Schiaratura L, Vachez S, Courtaigne B, et al. Efficacy of musical interventions in dementia:Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;38(2):359-69.

-

44Delphin-Combe F, Rouch I, Martin-Gaujard G, Relland S, Krolak-Salmon P. Effect of a non-pharmacological intervention, Voix d'Or(®):on behavior disturbances in Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. Geriatr Psychol Neuropsychiatr Vieill. 2013;11(3):323-30.

-

45Guetin S, Portet F, Picot MC, Pommie C, Messaoudi M, Djabelkir L, et al. Effect of music therapy on anxiety and depression in patients with Alzheimer's type dementia:Randomised, controlled study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord.2009 28(1):36-46.

-

46Ballard C, Brown R, Fossey J, Douglas S, Bradley P, Hancock J, et al. Brief psychosocial therapy for the treatment of agitation in Alzheimer disease (The CALM-AD Trial). Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2009;17(9): 726-33.

-

47Chikamori F, Kuniyoshi N, Shibuya S, Takase Y. Perioperative music therapy with a key-lighting keyboard system in elderly patients undergoing digestive tract surgery. Hepatogastroenterology 2004;51(59): 1384-6.

-

48Suzuki M, Kanamori M, Watanabe M, Nagasawa S, Kojima E, Ooshiro H, et al. Behavioral and endocrinological evaluation of music therapy for elderly patients with dementia. Nurs Health Sci 2004;6(1):11-8.

-

49Requena C, López MI, Maestú F, Campo P, López IJ, Ortiz T. Effects of cholinergic drugs and cognitive training on dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2004;18(1):50-4.

-

50Lyu J, Gao T, Li M, Xie L, Li W, Jin W, et al. The effect of music therapy on memory, language and psychological symptoms of patients with mild Alzheimer's disease. Chinese Journal of Neurology 2014;47(12):831-83.

-

51Goudour A, Samson S, Bakchine S, Ehrle N. Semantic memory training in Alzheimer's disease. Geriatr Psychol Neuropsychiatr Vieill.2011;9(2): 237-47.

-

52Han JW, Lee H, Hong JW, Kim K, Kim T, Byun HJ, et al. Multimodal cognitive enhancement therapy for patients with mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia:A multi- center, randomized, controlled, double-blind, crossover trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;55(2):787-96.

-

53Ceccato E, Vigato G, Bonetto C, Bevilacqua A, Pizziolo P, Crociani S, et al. STAM protocol in dementia:A multicenter, single-blind, randomized, and controlled trial. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012;27(5): 301-10.

-

54Lord TR, Garner JE. Effects of music on Alzheimer patients. Percept Mot Skills 1993;76(2):451-5.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

Apr-Jun 2018

History

-

Received

22 Dec 2017 -

Accepted

24 Mar 2018