Abstract

Aim

Evaluate and compare the proportion of PI and associated factors by IPAQ questionnaire, triaxial accelerometry and the combination of both. Adults aged ( 18 years were enrolled (n = 250).

Methods

We considered PI as < 600 MET-min/wk in the IPAQ total score, < 150 min/wk of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in 7 days accelerometry, and the combination of both criteria. Clinical assessment, spirometry, cardiopulmonary exercise test, bioelectrical impedance, isokinetic dynamometry, postural balance, and six-minute walk test were also performed. For participants practicing aquatic, martial arts or cycling, only the IPAQ criterion was considered.

Results

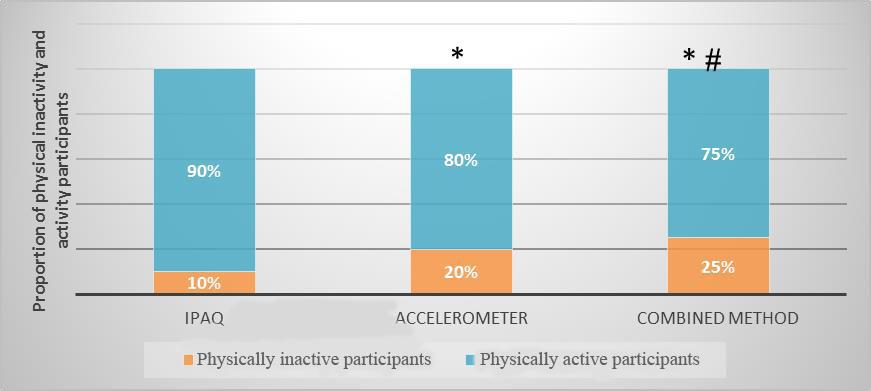

Proportions of PI were significantly different among methods (IPAQ, 10%; accelerometry, 20%; combination, 25%). After multivariate logistic regressions, PI was determined by age, sex, educational level, risk factors for cardiovascular disease, lean body mass, cardiorespiratory fitness, and postural balance.

Conclusion

Thus, the combined method for determining PI and associated factors in adults showed great validity, indicating that questionnaires and accelerometers are complementary and should be utilized in combination in epidemiological studies.

Keywords

sedentary lifestyle; energy metabolism; physical fitness

Introduction

Physical inactivity (PI) is a major risk factor for many diseases, particularly cardiovascular diseases11 Chodzko-Zajko WJ, Proctor DN, Fiatarone Singh MA, Minson CT, Nigg CR, Salem GJ, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(7):1510-30.,22 American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(3):687-708.. Currently, about 14% of the Brazilian adult population does not practice any physical activity, in the work environment, in transportation, in domestic work or in their leisure time33 Ministério da Saúde. Vigilância de fatores de risco e proteção para doenças crônicas por inquérito telefônico. In: Saúde SdVe, editor. Brasília2012.. Insufficiently active individuals are those who perform physical activities, but in quantity and intensity not enough to be classified as active as they do not meet the recommendations of at least 150 minutes/week of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in daily life (PADL)11 Chodzko-Zajko WJ, Proctor DN, Fiatarone Singh MA, Minson CT, Nigg CR, Salem GJ, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(7):1510-30.,22 American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(3):687-708..

The simplest way to assess the PADL is using questionnaires. This tool has been widely used in population-based samples due to its low cost and its ability to collect detailed information on the type of activity44 Ainsworth BE, Caspersen CJ, Matthews CE, Masse LC, Baranowski T, Zhu W. Recommendations to improve the accuracy of estimates of physical activity derived from self report. J Phys Act Health. 2012;9 Suppl 1:S76-84.. Among these questionnaires, the most widely used are the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)55 Barros MVG, Nahas MV. Reprodutibilidade (teste-reteste) do Questionário Internacional de Atividades Físicas (QIAF-Versão 6): um estudo-piloto com adultos no Brasil. Rev Bras Ciênc Mov. 2000;18(2):23-6.. However, the self-report may generate biases of interpretation and accuracy of the information provided, particularly in individuals with lower educational level66 Dyrstad SM, Hansen BH, Holme IM, Anderssen SA. Comparison of self-reported versus accelerometer-measured physical activity. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2014;46(1):99-106.,77 Garcia LMT, Barros MVG, Silva KS, Del Duca GF, Costa FFd, Oliveira ESA, et al. Socio-demographic factors associated with three sedentary behaviors in Brazilian workers. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2015;31(5):1015-24.. Accordingly, to address the main limitations of questionnaires, the PADL has been assessed in the last few years through motion sensors. Among then, triaxial accelerometers are the most accurate and reliable method compared to the doubly labeled water and has been recommended for routine strategy in epidemiological studies88 Lee I-M, Blair S, MaNSON J, Paffenbaerger Jr. RS. Epidemiologic methods in physical activity studies. Lee I-M, editor. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. 328 p..

Recent studies have shown conflicting results between the IPAQ and accelerometers66 Dyrstad SM, Hansen BH, Holme IM, Anderssen SA. Comparison of self-reported versus accelerometer-measured physical activity. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2014;46(1):99-106.,99 Fuentes Bravo M, Zuniga Paredes F, Rodriguez-Rodriguez FJ, Cristi-Montero C. [Occupational physical activity and body composition in adult women; pilot study]. Nutricion hospitalaria. 2013;28(4):1060-4.,1010 Umstattd Meyer MR, Baller SL, Mitchell SM, Trost SG. Comparison of 3 accelerometer data reduction approaches, step counts, and 2 self-report measures for estimating physical activity in free-living adults. J Phys Act Health. 2013;10(7):1068-74.. The questionnaire may overestimate77 Garcia LMT, Barros MVG, Silva KS, Del Duca GF, Costa FFd, Oliveira ESA, et al. Socio-demographic factors associated with three sedentary behaviors in Brazilian workers. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2015;31(5):1015-24. the PADL compared to accelerometers. However, motion sensors are not able to measure water activities, martial arts, strength training, upper body activities and cycling, underestimating the PADL of the practitioners of these modalities1111 Medina C, Barquera S, Janssen I. Validity and reliability of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire among adults in Mexico. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2013;34(1):21-8..

Although the assessment of the physical activity patterns and energy expenditure in epidemiological studies is essential, few studies have assessed the PADL combining the results of the instruments mentioned above1212 Duncan MJ, Arbour-Nicitopoulos K, Subramanieapillai M, Remington G, Faulkner G. Revisiting the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): Assessing physical activity among individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research. 2016.,1313 Wanner M, Probst-Hensch N, Kriemler S, Meier F, Autenrieth C, Martin BW. Validation of the long international physical activity questionnaire: Influence of age and language region. Preventive medicine reports. 2016;3:250-6.. Instead, one of these instruments is often chosen and, more recently, the accelerometer has been prioritized. It would be reasonable to state that the questionnaire could supplement the information obtained by accelerometry, maximizing the assessment of the PADL in adults. Using only the questionnaire, especially for individuals who routinely perform water activities like swimming, combat sports, and cycling, could also improve the assessment of PADL. There are limitations in these environments and are not adequately captured by accelerometers, and may underestimate measurement estimate1414 Strath SJ, Kaminsky LA, Ainsworth BE, Ekelund U, Freedson PS, Gary RA, et al. Guide to the assessment of physical activity: Clinical and research applications: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128(20):2259-79.,1515 Pedisic Z, Bauman A. Accelerometer-based measures in physical activity surveillance: current practices and issues. British journal of sports medicine. 2015;49(4):219-23..

We hypothesized that the combination of the IPAQ questionnaire and triaxial accelerometer is the best strategy to assess the proportion of physically inactive adults. This combined method could be more valid, associating with several recognized important predictors of PI in the general population. Accordingly, we aimed to evaluate and compare the proportion of PI in adults assessed by the IPAQ questionnaire, triaxial accelerometer and the combination of both. Also, we investigated associated factors of PI assessed by the combined method proposed here.

Methods

We evaluated 251 participants with a mean of 44±15 years, of which 150 were women and 101 men, with a weight of 74.7±17,4 kg and a height of 1.64±0.10 in a cross-sectional design. Participants were selected from the EPIMOV Study (Epidemiological Study of Human Movement and Hypokinetic Diseases). Briefly, the EPIMOV Study is a cohort study with the main objective of investigating the longitudinal association between sedentary behavior (which is the term for activities that are performed in the lying or sitting position and do not increase energy expenditure above resting levels, ≤ 1.5 metabolic equivalents (METs)1616 Owen N, Healy GN, Matthews CE, Dunstan DW. Too much sitting: the population health science of sedentary behavior. Exercise and sport sciences reviews. 2010;38(3):105-13., and PI with the occurrence of hypokinetic diseases, especially cardiorespiratory diseases. All participants underwent a general health screening supervised by a physician. First, they answered the physical activity readiness questionnaire (PAR-Q)1717 Standardization of Spirometry, 1994 Update. American Thoracic Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(3):1107-36.. Second, we assessed self-reported cardiovascular risk factors. Participants were inquired about the familiar history of cardiovascular disease and the presence of hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, smoking and PI1818 American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM's guidelines of exercise testing and prescription. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Wiliams & Wilkins; 2009. 265 p.. We investigated smoking by self-report and smoking load was calculated in pack-years. Third, Body weight and height were measured, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated. Participants with (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2 were considered obese. The following demographic variables were analyzed: age, sex, race, place of residence and schooling. We included only participants free of cardiac, respiratory and locomotor diseases.

After selection, all participants signed an informed consent. The local Ethics Committee on Human Research approved the present study.

Design

The assessments proposed by the present study were carried out in two days, seven days apart. In the first visit, participants underwent general health screening, anthropometrics, spirometry and cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET). At the end of the assessment, participants were informed how to use the triaxial accelerometer for the subsequent seven days. In the second visit, they returned the accelerometer, answered the IPAQ, then conducted an assessment of body composition by bioelectrical impedance, isometric and isokinetic muscle function and postural balance. At the end of the second visit, participants underwent the six-minute walk test (6MWT).

Spirometry

The forced vital capacity maneuver was carried out using a properly calibrated spirometer (Quark PFT, COSMED, Pavonadi Albano, Italy) according to the criteria established by the American Thoracic Society1919 Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(2):319-38.. Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC) and the FEV1/FVC ratio were measured in absolute and predicted values2020 Pereira CA, Sato T, Rodrigues SC. New reference values for forced spirometry in white adults in Brazil. J Bras Pneumol. 2007;33(4):397-406.. The restrictive spirometric2121 Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, Crapo R, Burgos F, Casaburi Rea, et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. European Respiratory Journal. 2005;26(5):948-68. pattern was identified as previous described (i.e., FEV1/FVC > 0.70 and FVC < 80% of predicted)1212 Duncan MJ, Arbour-Nicitopoulos K, Subramanieapillai M, Remington G, Faulkner G. Revisiting the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): Assessing physical activity among individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research. 2016..

Cardiopulmonary exercise test

The CPET was performed on a treadmill (ATL, Inbrasport, Curitiba, Brazil) under a ramp protocol established according to the estimated maximum oxygen uptake (V'O2) of each participant. Heart rate was monitored throughout the test by a 12-lead electrocardiogram (C12x, COSMED, Pavonadi Albano, Italy). Gas exchange and ventilatory variables were analyzed breath by breath, using periodically calibrated gas analyzer (Quark PFT, COSMED, Pavonadi Albano, Italy). The following criteria were used for determining the maximum effort: maximum heart rate (HR max) of at least 85% of predicted for age (220 - age) or rate of gas exchange (R) ≥ 1.0 or V'O2 plateau. Oxygen uptake, carbon dioxide production (V'CO2); and minute ventilation (V'E) were obtained. The data were filtered every 15 s by arithmetic average, and the average of the V'O2 values in the last 15 s at peak incremental exercise was used as representative of peak V'O2. The anaerobic threshold (AT) was obtained by the v-slope method as previous described2323 Wasserman K, Hansen J, Sue DY, Whipp BJ, Casaburi R. Principles of exercise testing and interpretation. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Wiliams & Wilkins; 2005. 576 p..

Body composition

We measured body composition by bioelectrical impedance (310E, BIODYNAMICS, Detroit, USA) carried out at ambient temperature. Resistance and reactance were determined with the participant in the supine position as previous described2424 Kyle UG, Genton L, Karsegard L, Slosman DO, Pichard C. Single prediction equation for bioelectrical impedance analysis in adults aged 20--94 years. Nutrition. 2001;17(3):248-53.24 Kyle UG, Genton L, Karsegard L, Slosman DO, Pichard C. Single prediction equation for bioelectrical impedance analysis in adults aged 20--94 years. Nutrition. 2001;17(3):248-53.. We calculated lean body mass (LBM) and body fat using groupspecific equations for healthy individuals2424 Kyle UG, Genton L, Karsegard L, Slosman DO, Pichard C. Single prediction equation for bioelectrical impedance analysis in adults aged 20--94 years. Nutrition. 2001;17(3):248-53..

International Physical Activity Questionnaire

The PADL was quantified using the long version of the IPAQ questionnaire validated for local culture and language2525 Matsudo S, Araújo T, Marsudo V, Andrade D, Andrade E, Braggion G. Questinário internacional de atividade f1sica (IPAQ): estudo de validade e reprodutibilidade no Brasil. Rev bras ativ fís saúde. 2001;6(2):05-18.. Total energy expenditure in high, moderate and low-intensity physical activities as well as in labor, transportation, recreation and leisure physical activities were quantified in MET/min.week-1. We considered physically inactive those who performed less than 600 MET/min.week-1 in the total score of the questionnaire2626 Hallal PC, Gomez LF, Parra DC, Lobelo F, Mosquera J, Florindo AA, et al. Lições aprendidas depois de 10 anos de uso do IPAQ no Brasil e Colômbia. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2010;7((suppl 2)):S259-S64..

Postural balance

We evaluated postural balance by the measure of the center of pressure bipedal (COP) on a force platform (BIOMEC 400, EMGSystem, Brazil). The frequency of the data acquisition was set at 100 Hz. Participants were instructed to remain as static as possible in the following situations: Bipedal support with open eyes; bipedal support with eyes closed; semi-tandem support with eyes open; and semi-tandem support with eyes closed. Each position was held for 30 seconds. In the case of situations with open eyes, participants were instructed to look at a target of 4.5 cm in diameter, positioned at the eye level.

Peripheral muscle function

We assessed muscle function on an isokinetic dynamometer (Biodex, Lumex, Inc., Ronkonkoma, NY). The gravity was properly corrected throughout all tests. Peak torque (PT) in Nm was assessed by two tests of five movements at 60o/s. After a rest period of at least five minutes, participants underwent tests at 300o/s to register the total work (TT), in kJ, after 30 repetitions. We considered the highest value for analysis in all the tests mentioned above. These tests were applied to the dominant lower and upper limbs. Participants were strongly encouraged during all the tasks.

Six-minute walk test

The 6MWT was performed according to the standards of the American Thoracic Society2727 Laboratories ACoPSfCPF. ATS statement: guidelines for the sixminute walk test. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2002;166(1):111.. The distance traveled on the test (6MWD) was recorded in meters and in the percentage of predicted values2828 Dourado VZ, Vidotto MC, Guerra RLF. Reference equations for the performance of healthy adults on field walking tests. Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia. 2011;37(5):607-14..

Accelerometry

We used triaxial accelerometers to assess PADL (ActiGraph, GTX 3, MTI, Pensacola, FL). The software used for analysis was actilife 6.11.9. The accelerometry was performed during seven consecutive days. We instructed all the participants on how the accelerometer should be positioned at the waist above the dominant hip. Participants completed a checklist to assess whether your day was representative. We considered only valid days with at least 12 hours of monitoring, starting at the moment of awakening. The time spent in each physical activity intensity and the energy expenditure were obtained and therefore the average of at least four valid days was calculated. The time of use was identified by asking the volunteer to remove the accelerometer from the hip region at the time of going to sleep, since we did not evaluate the sleep period in this study. We considered physically inactive those who did not perform at least 150 min/week of moderate-tovigorous physical activity. The valid data were the use of accelerometers at least four days, one being a weekend. The day was considered valid when they were recorded for at least 10 hours of recording. Data were collected at a frequency of 30 Hz and analyzed in epochs of 60 s. For the calculation of the minutes spent in moderate and vigorous activities per week, the sum of all valid days was adjusted by the number of valid

days and multiplied by seven, thus obtaining the individual weekly average. For the classification of physical activity in the different intensities, the cut-off point was the one proposed by Freedson et al.2929 Freedson PS, Melanson E, Sirard J. Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30(5):777-81., being considered as moderate activity counts between 1,952 and 5,724, and above 5,725 counts as vigorous activities.

Combined method for assessing PADL

We inquired participants about the realization of aquatic physical activities (e.g., swimming) and martial arts/body contact activities, upper body physical activities, and cycling. For those who met these criteria, we considered only the results of the IPAQ for identifying PI (i.e., < 600 MET/min.week-1). For these individuals were not using the accelerometer at the moments of the practices of the swimming pool (because it is not water resistant) and fights, and also by the limitations in the use of cycling3030 Jakicic JM, Winters C, Lagally K, Ho J, Robertson RJ, Wing RR. The accuracy of the TriTrac-R3D accelerometer to estimate energy expenditure. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31(5):747-54.. Also, in the combined method proposed here, we considered physically inactive all participants who showed total score of the IPAQ < 600 MET/min.week-1 and/or quantity and intensity of PADL < 150 min/week of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity obtained by triaxial accelerometry.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyzes were performed with SPSS version 22.0. We performed a descriptive analysis including frequencies and histograms initially. Physical inactivity was investigated as a categorical variable. The associations between PI and the studied variables were evaluated by calculating the odds ratio and its 95% confidence interval. Proportions were compared using the x2 test and continuous variables were compared by the Student t between physically active and inactive participants in each of the methods utilized (IPAQ, accelerometry, and combined method).

The proportion of physically inactive participants was calculated and compared between the methods of evaluation. Also, the agreement between IPAQ and accelerometry was evaluated by Kappa test. The kappa values, equal to or greater than 0.80, were considered adequate.

The numbers of variables and as co-variables in the logistic regression statistical models to 1/10 were evaluated from the number of participants or at least ten observations for each variable included in the model. The variables of interest were included in the model the following groups: demographic, anthropometric, body composition, clinics, cardiorespiratory fitness, and postural balance.

Energy expenditure, the number of steps performed and the intensity of daily physical activity were evaluated descriptively and the average daily time spent standing, lying and sitting were evaluated as well.

We performed multivariate logistic regressions using PI as the outcome. The objective was to obtain the best model, discarding non-significant variables with almost no contribution to the setting. The processing was performing through simple logistic regression for each independent variable. In the case of categorical variables, the transformation was performed using dummy variables in the categories as a reference. The variables that presented p values ≤ 0.20 were selected. The likelihood ratio test verified the overall fit of the model. Age and BMI were initially analyzed as continuous variables and in the case of lack of significance they were transformed into categorical variables. Age was stratified into 20-39, 40-59 and ≥ 60 years and BMI in 18 to 24.9, 30 to 34.9 and 25-29.9, and ≥ 35 kg/ m2, respectively representative of young adults, middle-aged and older adults and normal weighted, overweighed and obese participants. Three regression models were constructed using PI as the outcome obtained by the combined method. Values of odds ratio and its 95% confidence limits were calculated. One of the goals was to quantify the number of significant predictors in each of the PI identification methods. The probability of an alpha error was set at 5%.

Results

There was evenly distributed mean values of BMI were representative of overweight (Table 1). Spirometric indices showed that participants were free of lung obstruction. Twenty-five participants (10%) presented restrictive spirometric pattern. Participants were predominantly white. Considering the cardiovascular risk assessment, almost half of our participants had a moderate cardiovascular risk with two or more cardiovascular risk factors.

According to the IPAQ results, 89% of participants had a median-to-high level of physical activity (Table 2), that is, the volunteers performed between more than 600 METs/min/week to less than 3000 METs/min/week. Participants reported 240-285 minutes spent sitting. About 10% of the participants reported practicing aquatic physical activities and martial arts/body contact, upper body and cycling activities (Table 2).

The proportion of PI was significantly different among the methods utilized (Figure 1). There was poor agreement between IPAQ and accelerometry (Kappa = 0.152; p = 0.01).

The proportion of physically inactivity and activity participants according to the evaluation method: International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), seven days triaxial accelerometry and the combination of both. *p < 0,05 vs. IPAQ; ǂp< 0,05 vs. Accelerometry

Tables 3 and 4 show the main variables associated with PI according to the combined method. Demographic factors such as age and education level were significantly different between physically active and inactive participants (Table 3).

Considering cardiovascular risk factors, we found that familiar history of cardiovascular disease, dyslipidemia, and current smoking, were significantly different between physically active and inactive participants. PI showed significant association with some of the risk factors for cardiovascular disease (Table 3). The low level of physical fitness was significantly associated with PI (Table 4). Among the physical fitness variables, peak V'O2, AT, maximum HR, maximum V'O2/HR, maximum V'E and isokinetic muscle strength of the knee were significantly lower in the physically inactive participants. Postural balance, lean body mass, and 6MWD were significantly lower in physically inactive participants in only one or two proposed methods of evaluation (Table 4).

After multivariate logistic regression analyses, the main predictors of PI determined by combined method were age, female sex, lean body mass, familiar history of cardiovascular disease, dyslipidemia, obesity, smoking, peak V'O2 and COP (Table 5).

Discussion

We assessed the proportion of PI among asymptomatic adults using the IPAQ and triaxial accelerometers. The IPAQ significantly underestimated the proportion of physically inactive individuals. However, in spite of the scarce studies showing the efficacy agreement between IPAQ and accelerometry, we suggest the combination of the two methods may be more valid and provided significantly higher prevalence of physical inactivity.

The main finding of the present study was that the combination of questionnaire and triaxial accelerometry resulted in the significantly higher proportion of PI compared to IPAQ and accelerometry separately. We also observed after multivariate logistic regressions that PI assessed by the combined method proposed in the present study was significantly associated with a larger number of relevant attributes.

Previous findings in the literature are very conflicting. This fact can primarily be attributed to the complexity of evaluation of PADL. Select the most suitable tool is challenging, especially in the general population. Moreover, the various dimensions of physical activity require different assessment tools3131 Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985;100(2):126-31..

Several studies have compared accelerometers with questionnaires for assessing PADL3232 Torquato E, Gerage A, Meurer S, Borges R, Silva M, Benedetti T. Comparação do nível de atividade física medido por acelerômetro e questionário IPAQ em idosos. Rev. bras. ativ. fís. saúde. 2016;21(2):144-53.

33 Oguma Y, Osawa Y, Takayama M, Abe Y, Tanaka S, Lee IM, et al. Validation of Questionnaire-Assessed Physical Activity in Comparison with Objective Measures Using Accelerometers and Physical Performance Measures Among Community-Dwelling Adults Aged >/=85 Years in Tokyo, Japan. J Phys Act Health. 2016:1-28.-3434 Chandonnet N, Saey D, Almeras N, Marc I. French Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire compared with an accelerometer cut point to classify physical activity among pregnant obese women. PloS one. 2012;7(6):e38818.. However, few have proposed to assess the combination of the two methods32. Since the gold standard for evaluating PADL is not determined yet in large-scale epidemiological studies, questionnaires and accelerometers have been the instruments most commonly used88 Lee I-M, Blair S, MaNSON J, Paffenbaerger Jr. RS. Epidemiologic methods in physical activity studies. Lee I-M, editor. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. 328 p.. Accelerometers provide information about the frequency, duration, intensity and pattern of physical activity and are capable of storing information for a long period. Unfortunately, they underestimate the energy expenditure of some activities of daily life and are unable to accurately assess physical activities with arms, water activities, cycling and walking in a steep climb, among others. Questionnaires, in turn, represent the most frequently used method in epidemiological studies focusing mainly on its advantage of low cost. It also presents as one of its main strengths the ability to discern some dimensions of daily physical activity, such as occupational activities, transport and leisure time. Although the questionnaires are accurate to assess physical activity of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, they present difficulties in quantifying low-intensity physical activities, especially in some specific groups (e.g., older adults and women). Therefore, it is reasonable to assert that the combination of questionnaire and accelerometers may be the best strategy for more accurate assessment of PADL88 Lee I-M, Blair S, MaNSON J, Paffenbaerger Jr. RS. Epidemiologic methods in physical activity studies. Lee I-M, editor. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. 328 p..

The proportion of PI observed in the combined method proposed here was 25%. Our results are in agreement with literature. In a large study involving 212,021 participants from 51 countries, the average prevalence of PI were 18%, 15% for men and 20% for women, with wide variation between 2 and 72%3535 Guthold R, Ono T, Strong KL, Chatterji S, Morabia A. Worldwide variability in physical inactivity a 51-country survey. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(6):486-94.. In every country involved, women and older adults were more likely to be physically inactive3535 Guthold R, Ono T, Strong KL, Chatterji S, Morabia A. Worldwide variability in physical inactivity a 51-country survey. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(6):486-94.. Brazil was involved in this study3535 Guthold R, Ono T, Strong KL, Chatterji S, Morabia A. Worldwide variability in physical inactivity a 51-country survey. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(6):486-94. including 4,458 individuals. The results showed 26% of PI, very similar to the 25% found in the present study combining the two instruments. Several Brazilian studies have investigated the prevalence of PI, mostly using questionnaires. However, as the present study, the vast majority was held involving only one city. Unfortunately, multicenter studies are scarce and surely involve few cities. These national data using the short version of the IPAQ indicate a prevalence of PI between 29 and 31%3636 Florindo AA, Hallal PC. Epidemiologia da atividade física. Florindo AA, editor. São Paulo: Atheneu; 2011. 210 p.. We found in the present study lower prevalence through the long version of the IPAQ (10%). This fact can be attributed primarily to the different questionnaires used and the feature conducive to physical activity in the city in which the present study was conducted (Santos, São Paulo, Brazil). This city is mostly flat, coastal and located in the southeast region. In fact, Brazilian multicenter studies showed that the prevalence of PI is lower in the South and Southeast regions (about 24%)3737 Monteiro CA, Conde WL, Matsudo SM, Matsudo VR, Bonsenor IM, Lotufo PA. A descriptive epidemiology of leisure-time physical activity in Brazil, 1996-1997. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2003;14(4):246-54.,3838 Siqueira FV, Facchini LA, Piccini RX, Tomasi E, Thume E, Silveira DS, et al. [Physical activity in young adults and the elderly in areas covered by primary health care units in municipalities in the South and Northeast of Brazil]. Cad Saude Publica. 2008;24(1):39-54.. We were unable to find Brazilian studies that assessed the prevalence of PI among adults through triaxial accelerometry.

Our study showed inconsistent agreement between accelerometry and IPAQ (Kappa = 0.152; p = 0.01). This finding is in agreement with previous studies. Chastin et al.3939 Chastin SF, Culhane B, Dall PM. Comparison of self-reported measure of sitting time (IPAQ) with objective measurement (activPAL). Physiol Meas. 2014;35(11):2319-28. observed a weak correlation between accelerometry and IPAQ. The agreement between then was also weak considering the wide confidence interval3939 Chastin SF, Culhane B, Dall PM. Comparison of self-reported measure of sitting time (IPAQ) with objective measurement (activPAL). Physiol Meas. 2014;35(11):2319-28.. Oyeyemi et al.4040 Oyeyemi AL, Umar M, Oguche F, Aliyu SU, Oyeyemi AY. Accelerometer-determined physical activity and its comparison with the International Physical Activity Questionnaire in a sample of Nigerian adults. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e87233. evaluated 144 participants underwent triaxial accelerometry and IPAQ. The correlation between the times in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity obtained by the two instruments was moderate, and the limit of agreement was wide. Again, the questionnaire underestimated the amount of sedentary physical activity4040 Oyeyemi AL, Umar M, Oguche F, Aliyu SU, Oyeyemi AY. Accelerometer-determined physical activity and its comparison with the International Physical Activity Questionnaire in a sample of Nigerian adults. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e87233.. Men and women reported time spent in sedentary physical activity, on average, 131 min/day less than the amount obtained by accelerometry and the correlation between the two methods was weak4141 Ottevaere C, Huybrechts I, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Sjostrom M, Ruiz JR, Ortega FB, et al. Comparison of the IPAQ-A and actigraph in relation to VO2max among European adolescents: the HELENA study. J Sci Med Sport. 2011;14(4):317-24.. The IPAQ presented limitations to classify adults in low ranges and high intensity of physical activity, with the difference increasing progressively with the increasing amount and intensity of physical activity4242 Hagstromer M, Ainsworth BE, Oja P, Sjostrom M. Comparison of a subjective and an objective measure of physical activity in a population sample. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7(4):541-50.,4343 Boyle T, Lynch BM, Courneya KS, Vallance JK. Agreement between accelerometer-assessed and self-reported physical activity and sedentary time in colon cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(4):1121-6..

Our results showed greater validity when we combine the two methods of assessing PADL. Harris et al.4444 Harris TJ, Owen CG, Victor CR, Adams R, Ekelund U, Cook DG. A comparison of questionnaire, accelerometer, and pedometer: measures in older people. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(7):1392-402. observed differences in concurrent validity when compared a specific physical activity questionnaire and triaxial accelerometry. The results of accelerometry were correlated consistently with general health, anthropometric and psychological variables while the questionnaire was associated only with the psychological variables. Sabia et al.4545 Sabia S, Cogranne P, van Hees VT, Bell JA, Elbaz A, Kivimaki M, et al. Physical Activity and Adiposity Markers at Older Ages: Accelerometer Vs Questionnaire Data. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015. observed stronger correlations between the results of accelerometry and anthropometric and body composition variables compared to the physical activity questionnaire. The results mentioned above suggest that the validity of the accelerometer is more consistent compared to questionnaires. Our results suggest that the combination of these two methods might be even better. For reliability when using the two instruments is greater for subjects practicing aquatic activities, cycling, fights (accelerometry is not reliable), and individuals with little schooling and the elderly (overestimate the PADL).

After multivariate logistic regressions, we found a great number of significant predictors using the combined method, especially considering physical fitness variables (e.g., peak V'O2 and COP). This fact may be attributed first to the overestimation of the quantity of PADL and lower precision for low-intensity related to questionnaires. On the other hand, the triaxial accelerometry may result in spurious interpretations of PADL regarding water, upper body, and cycling activities, etc.

The present study has limitations that should be considered. We recruited a convenience sample, which may introduce bias, for example, a higher proportion of women and higher education level. However, our results showed a proportion of PI as well as other demographic and anthropometric characteristics very compatible with the previously described in the literature for our metropolitan area. Moreover, the sample was statistically sufficient, especially for the construction of multivariate logistic regression models. To be used as a criterion of comparison and such as the cut-point utilized for moderate-vigorous physical activity.

We may conclude that the combined method proposed here resulted in the more reliable proportion of PI and was valid, being predicted by several demographic, clinical and physiological variables. Our findings have practical implications. They suggest that the main PADL assessment methods commonly used in epidemiological studies are complementary and should always be used in combination as a routine strategy.

References

-

1Chodzko-Zajko WJ, Proctor DN, Fiatarone Singh MA, Minson CT, Nigg CR, Salem GJ, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(7):1510-30.

-

2American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(3):687-708.

-

3Ministério da Saúde. Vigilância de fatores de risco e proteção para doenças crônicas por inquérito telefônico. In: Saúde SdVe, editor. Brasília2012.

-

4Ainsworth BE, Caspersen CJ, Matthews CE, Masse LC, Baranowski T, Zhu W. Recommendations to improve the accuracy of estimates of physical activity derived from self report. J Phys Act Health. 2012;9 Suppl 1:S76-84.

-

5Barros MVG, Nahas MV. Reprodutibilidade (teste-reteste) do Questionário Internacional de Atividades Físicas (QIAF-Versão 6): um estudo-piloto com adultos no Brasil. Rev Bras Ciênc Mov. 2000;18(2):23-6.

-

6Dyrstad SM, Hansen BH, Holme IM, Anderssen SA. Comparison of self-reported versus accelerometer-measured physical activity. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2014;46(1):99-106.

-

7Garcia LMT, Barros MVG, Silva KS, Del Duca GF, Costa FFd, Oliveira ESA, et al. Socio-demographic factors associated with three sedentary behaviors in Brazilian workers. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2015;31(5):1015-24.

-

8Lee I-M, Blair S, MaNSON J, Paffenbaerger Jr. RS. Epidemiologic methods in physical activity studies. Lee I-M, editor. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. 328 p.

-

9Fuentes Bravo M, Zuniga Paredes F, Rodriguez-Rodriguez FJ, Cristi-Montero C. [Occupational physical activity and body composition in adult women; pilot study]. Nutricion hospitalaria. 2013;28(4):1060-4.

-

10Umstattd Meyer MR, Baller SL, Mitchell SM, Trost SG. Comparison of 3 accelerometer data reduction approaches, step counts, and 2 self-report measures for estimating physical activity in free-living adults. J Phys Act Health. 2013;10(7):1068-74.

-

11Medina C, Barquera S, Janssen I. Validity and reliability of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire among adults in Mexico. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2013;34(1):21-8.

-

12Duncan MJ, Arbour-Nicitopoulos K, Subramanieapillai M, Remington G, Faulkner G. Revisiting the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): Assessing physical activity among individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia research. 2016.

-

13Wanner M, Probst-Hensch N, Kriemler S, Meier F, Autenrieth C, Martin BW. Validation of the long international physical activity questionnaire: Influence of age and language region. Preventive medicine reports. 2016;3:250-6.

-

14Strath SJ, Kaminsky LA, Ainsworth BE, Ekelund U, Freedson PS, Gary RA, et al. Guide to the assessment of physical activity: Clinical and research applications: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128(20):2259-79.

-

15Pedisic Z, Bauman A. Accelerometer-based measures in physical activity surveillance: current practices and issues. British journal of sports medicine. 2015;49(4):219-23.

-

16 Owen N, Healy GN, Matthews CE, Dunstan DW. Too much sitting: the population health science of sedentary behavior. Exercise and sport sciences reviews. 2010;38(3):105-13.

-

17Standardization of Spirometry, 1994 Update. American Thoracic Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(3):1107-36.

-

18American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM's guidelines of exercise testing and prescription. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Wiliams & Wilkins; 2009. 265 p.

-

19Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(2):319-38.

-

20Pereira CA, Sato T, Rodrigues SC. New reference values for forced spirometry in white adults in Brazil. J Bras Pneumol. 2007;33(4):397-406.

-

21Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, Crapo R, Burgos F, Casaburi Rea, et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. European Respiratory Journal. 2005;26(5):948-68.

-

22Pereira C, Neder J. Diretrizes para testes de função pulmonar. J Bras Pneumol. 2002;28(Supl 3):s1-s238.

-

23Wasserman K, Hansen J, Sue DY, Whipp BJ, Casaburi R. Principles of exercise testing and interpretation. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Wiliams & Wilkins; 2005. 576 p.

-

24Kyle UG, Genton L, Karsegard L, Slosman DO, Pichard C. Single prediction equation for bioelectrical impedance analysis in adults aged 20--94 years. Nutrition. 2001;17(3):248-53.

-

25Matsudo S, Araújo T, Marsudo V, Andrade D, Andrade E, Braggion G. Questinário internacional de atividade f1sica (IPAQ): estudo de validade e reprodutibilidade no Brasil. Rev bras ativ fís saúde. 2001;6(2):05-18.

-

26Hallal PC, Gomez LF, Parra DC, Lobelo F, Mosquera J, Florindo AA, et al. Lições aprendidas depois de 10 anos de uso do IPAQ no Brasil e Colômbia. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2010;7((suppl 2)):S259-S64.

-

27Laboratories ACoPSfCPF. ATS statement: guidelines for the sixminute walk test. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2002;166(1):111.

-

28Dourado VZ, Vidotto MC, Guerra RLF. Reference equations for the performance of healthy adults on field walking tests. Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia. 2011;37(5):607-14.

-

29Freedson PS, Melanson E, Sirard J. Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30(5):777-81.

-

30Jakicic JM, Winters C, Lagally K, Ho J, Robertson RJ, Wing RR. The accuracy of the TriTrac-R3D accelerometer to estimate energy expenditure. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31(5):747-54.

-

31Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985;100(2):126-31.

-

32Torquato E, Gerage A, Meurer S, Borges R, Silva M, Benedetti T. Comparação do nível de atividade física medido por acelerômetro e questionário IPAQ em idosos. Rev. bras. ativ. fís. saúde. 2016;21(2):144-53.

-

33Oguma Y, Osawa Y, Takayama M, Abe Y, Tanaka S, Lee IM, et al. Validation of Questionnaire-Assessed Physical Activity in Comparison with Objective Measures Using Accelerometers and Physical Performance Measures Among Community-Dwelling Adults Aged >/=85 Years in Tokyo, Japan. J Phys Act Health. 2016:1-28.

-

34Chandonnet N, Saey D, Almeras N, Marc I. French Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire compared with an accelerometer cut point to classify physical activity among pregnant obese women. PloS one. 2012;7(6):e38818.

-

35Guthold R, Ono T, Strong KL, Chatterji S, Morabia A. Worldwide variability in physical inactivity a 51-country survey. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(6):486-94.

-

36Florindo AA, Hallal PC. Epidemiologia da atividade física. Florindo AA, editor. São Paulo: Atheneu; 2011. 210 p.

-

37Monteiro CA, Conde WL, Matsudo SM, Matsudo VR, Bonsenor IM, Lotufo PA. A descriptive epidemiology of leisure-time physical activity in Brazil, 1996-1997. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2003;14(4):246-54.

-

38Siqueira FV, Facchini LA, Piccini RX, Tomasi E, Thume E, Silveira DS, et al. [Physical activity in young adults and the elderly in areas covered by primary health care units in municipalities in the South and Northeast of Brazil]. Cad Saude Publica. 2008;24(1):39-54.

-

39Chastin SF, Culhane B, Dall PM. Comparison of self-reported measure of sitting time (IPAQ) with objective measurement (activPAL). Physiol Meas. 2014;35(11):2319-28.

-

40Oyeyemi AL, Umar M, Oguche F, Aliyu SU, Oyeyemi AY. Accelerometer-determined physical activity and its comparison with the International Physical Activity Questionnaire in a sample of Nigerian adults. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e87233.

-

41Ottevaere C, Huybrechts I, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Sjostrom M, Ruiz JR, Ortega FB, et al. Comparison of the IPAQ-A and actigraph in relation to VO2max among European adolescents: the HELENA study. J Sci Med Sport. 2011;14(4):317-24.

-

42Hagstromer M, Ainsworth BE, Oja P, Sjostrom M. Comparison of a subjective and an objective measure of physical activity in a population sample. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7(4):541-50.

-

43Boyle T, Lynch BM, Courneya KS, Vallance JK. Agreement between accelerometer-assessed and self-reported physical activity and sedentary time in colon cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(4):1121-6.

-

44Harris TJ, Owen CG, Victor CR, Adams R, Ekelund U, Cook DG. A comparison of questionnaire, accelerometer, and pedometer: measures in older people. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(7):1392-402.

-

45Sabia S, Cogranne P, van Hees VT, Bell JA, Elbaz A, Kivimaki M, et al. Physical Activity and Adiposity Markers at Older Ages: Accelerometer Vs Questionnaire Data. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

2017

History

-

Received

26 Sept 2016 -

Accepted

12 Mar 2017