Abstract

The central purpose of this paper is to map out the Brazilian web of accountability institutions and observe how institutions establish links with each other in order to control corruption cases that reach them. Focus is on institutions that are part of the Brazilian anti-corruption agenda, which include the Federal Public Prosecutor's Office, the Federal Police, the Office of the Comptroller General, the Federal Court of Accounts, the Federal Justice and the Ministries. In the literature, the most widespread argument is that, despite recent institutional improvements, the result produced by this web in terms of coordination is still weak. This article tests this claim by looking at the program called 'Inspections from Public Lotteries'. Through a longitudinal approach, I observed the flux of control activities among the institutions, especially the establishment of investigative and judicial proceedings. Not only I explored the extent to which corruption impacts the establishment of interactions, but I also investigated how the interactions affect the speed of judicial proceedings – using logistic regressions and survival analysis. The conclusion is that the Brazilian web is able to articulate itself in order to hold public officials accountable (something new in this recent democracy), but not in a homogeneous way across all institutions (something the literature has missed). Furthermore, I demonstrate that the entire web of accountability institutions is unable to arrive at a decision in a timely manner.

Accountability; corruption; web of accountability institutions; interactions; Brazil.

When we think about improving the democratic control of corruption, the focus often falls upon changes in the accountability institutions. The recent literature indicates that, at the current stage of reform and democratization around the globe, accountability institutions must undergo a strengthening process in order to improve economic performance, promote fiscal responsibility and fight corruption (SIAVELIS, 2000SIAVELIS, Peter M. (2000), The president and Congress in post-authoritarian Chile: institutional constraints to democratic consolidation. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. 245 pp..). This necessity is especially the case with horizontal accountability institutions, which are seen as effective mechanisms for controlling corruption (O'DONNELL, 1998O'DONNELL, Guilhermo (1998), Accountability horizontal e novas poliarquias. Lua Nova. Nº 44, pp. 27-54.; ROSE-ACKERMAN, 1999)ROSE-ACKERMAN, Susan (1999), Corruption and government: causes, consequences and reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 266 pp...

In this study, the discussion centers on the articulation of six Brazilian institutions of horizontal accountability – the Federal Court of Accounts (TCU), the Federal Public Prosecutor's Office (MPF), the Federal Police (PF), the internal control in the Ministries, the Federal Justice (JF), and the Office of the Comptroller General (CGU). Arraste e largue o ficheiro ou ligação para aqui, para traduzir o documento ou página Web.The creation of the CGU was an attempt to improve the Brazilian institutional arena in the development of efficient mechanisms to face corruption in the public sector.

I am interested in analyzing the CGU findings in its 'Program of Inspections from Public Lotteries', which audits the federal funds transferred to municipalities. In this program, any violations of public sector regulation are reported, and I refer to them as 'irregularities'. The reports also bring the mayors' justifications – and I analyze whether the local public officials are able to provide CGU with a publicly acceptable justification for the reported violation. If the justification is not accepted, I then classify the irregularity as 'corruption'.

The objective is to investigate the interactions among those six Brazilian accountability institutions after they receive CGU reports. The six institutions under analysis should be actively connected to control deviations involving federal resources. Since none of them can monitor, investigate and punish corruption individually, it becomes necessary for them to be connected to hold local governments accountable to the federal level. The point advocated here is that, if a federal institution such as the CGU decides to put into practice a program such as the Lottery, - which involves the monitoring of billions of Reais and the allocation of thousands of auditors to the municipalities every year, - the other institutions of the web should not dismiss this effort and ignore the resulting reports.

The first part of the paper addresses the idea of a web of accountability institutions, and how this web has matured in Brazil in recent times. The second part provides a description of the accountability institutions under analysis, with special attention to their accountability roles and the main criticisms that they have received. The idea is to give a clear picture of what, exactly, is an ideal trajectory for the cases found by the CGU. The following section focuses on the concept of corruption that is applied in this paper and on how it departs from the mainstream literature. The fourth part describes the methodology of the longitudinal research and what this perspective entailed. Finally, I analyze the flux of the irregularities in the Brazilian web of accountability institutions, especially concerned with the arrival at a timely decision.

The web of accountability institutions in Brazil

Contemporary democracies reaffirm, as a core principle, the idea that rulers should be held accountable by the people, and should be held responsible for their actions and omissions in the exercise of power. The definition of accountability used in this paper follows the ideas of Mark Philp (2009)PHILP, M. (2009), Delimiting democratic accountability. Political Studies. Vol. 57, Nº 02, pp. 28-53., for whom "A is accountable with respect to M when some individual, body or institution, Y, can require A to inform and explain/justify his or her conduct with respect to M" (PHILP, 2009PHILP, M. (2009), Delimiting democratic accountability. Political Studies. Vol. 57, Nº 02, pp. 28-53., p. 32). In this paper, the usage of this definition runs as follows: some federal institutions (Y) impose accountability on the municipal government (A), when considering the application of federal funds in some areas of public policy (M).

One of the most controversial points in the definition of accountability concerns the sanction theme (MAINWARING, 2003MAINWARING, Scott (2003), Introduction: democratic accountability in Latin America. In: Democratic accountability in Latin America. Edited by MAINWARING, Scott and WELNA, Christopher. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 03-33.). For some authors, accountability calls for mechanisms of direct and credible sanctions in order to be effective (KENNEY, 2003KENNEY, Charles D. (2003), Horizontal accountability: concepts and conflicts. In: Democratic accountability in Latin America. Edited by MAINWARING, Scott and WELNA, Christopher. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 55-75.; MORENO et al., 2003MORENO, Erika; CRISP, Brian F., and SHUGART, Matthew Soberg (2003), The accountability deficit in Latin American. In: Democratic accountability in Latin America. Edited by MAINWARING, Scott and WELNA, Christopher. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 79-131.; SCHEDLER et al., 1999SCHEDLER, Andreas; DIAMOND, Larry and PLATTNER, Marc F. (eds) (1999), The self-restraining state: power and accountability in new democracies. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers. 398 pp..). As a rebuttal to this point, it might be (convincingly) argued that accountability can be divided between direct and indirect power of sanction, for certain accountability institutions have only the ability to transfer their findings to other actors that may establish punishments (MAINWARING, 2003MAINWARING, Scott (2003), Introduction: democratic accountability in Latin America. In: Democratic accountability in Latin America. Edited by MAINWARING, Scott and WELNA, Christopher. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 03-33.; MANZETTI and MORGENSTERN, 2003MANZETTI, Luigi and MORGENSTERN, Scott (2003), Legislative oversight: interests and institutions in the United States and Argentina. In: Democratic accountability in Latin America. Edited by MAINWARING, Scott and WELNA, Christopher. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 132-169.). What this means is that institutions with indirect sanction power must rely heavily on a close relationship with the institutions that can pronounce judgments so that the cycle of accountability may come to a close.

The accountability institutions studied here are part of what O'Donnell (2001)O’DONNELL, Guilhermo (2001), Accountability horizontal: la institucionalización legal de la desconfianza política. POSTData. Nº 07, pp. 11-34. has called 'horizontal accountability'. While vertical accountability is associated with electoral or societal control, horizontal accountability requires state agencies with legal authority to take action (from routine checks to criminal sanctions) in relation to actions or omissions by other state agencies (O'DONNELL, 2001O’DONNELL, Guilhermo (2001), Accountability horizontal: la institucionalización legal de la desconfianza política. POSTData. Nº 07, pp. 11-34.).

It seems fair to suggest that Brazil has improved its horizontal accountability institutions since its redemocratization in the late 1980's. For example, the Federal Court of Accounts has now a reasonable margin of institutional autonomy to exercise its functions of external control (LOUREIRO et al., 2009LOUREIRO, Maria Rita; TEIXEIRA, Marco Antonio Carvalho, and MORAES, Tiago Cacique (2009), Democratização e reforma do Estado: o desenvolvimento institucional dos Tribunais de Contas no Brasil recente. Revista de Administração Pública. Vol. 43, Nº 04, pp. 739-772.); federal public prosecutors have large autonomy to pursue investigations; the Federal Police has gained more personnel and resources (ARANTES, 2011ARANTES, R. (2011), Polícia Federal e construção institucional. In: Corrupção e sistema político no Brasil. Edited by AVRITZER, Leonardo and FIGUEIRAS, Fernando. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira. pp. 99-132.); and the CGU was created with the core mission of auditing and preventing corruption (OLIVIERI, 2011)OLIVIERI, Cecília (2011), Combate à corrupção e controle interno. Cadernos Adenauer. Vol. XII, Nº 03, pp. 99-109..

But none of the recently strengthened institutions of Brazil has corruption control as its sole responsibility, and none of them concentrate all the steps involved in the accountability cycle, which includes monitoring, investigating and sanctioning (OLIVIERI, 2011OLIVIERI, Cecília (2011), Combate à corrupção e controle interno. Cadernos Adenauer. Vol. XII, Nº 03, pp. 99-109.; TAYLOR, 2011TAYLOR, Matthew M. (2011), The Federal Judiciary and Electoral Courts. In: Corruption and democracy in Brazil: the struggle for accountability. Edited by POWER, Timothy J. and TAYLOR, Matthew M.. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. pp. 162-83.). The prevention step is left mainly to the CGU, which produces strategic information to identify illicit actions regarding federal resources. The TCU is in charge of administrative penalties involving the misuse of public resources. The Federal Police investigates the felonies; while the MPF presents the complaints to the Judiciary, which in its turn is responsible for initiating civil and criminal proceedings. In the end of the cycle, the Federal Courts rule on those proceedings. Thus, these institutions compose together a web, each serving its own functions, but in a way that can - and should - be complementary.

In fact, there is a growing support for the claim that accountability institutions should constitute an integrated web of agencies, whose credibility depends on the quality of the links and synergies between the different components of the system (O'DONNELL, 2001O’DONNELL, Guilhermo (2001), Accountability horizontal: la institucionalización legal de la desconfianza política. POSTData. Nº 07, pp. 11-34.) – a concept which Mainwaring and Welna (2003)MAINWARING, Scott and WELNA, Christopher (eds) (2003), Democratic accountability in Latin America.. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 360 pp.. have named the "web of accountability institutions".

While the literature argues that studies on control mechanisms must map the institutions and actors that promote accountability (ARANTES, 2011ARANTES, R. (2011), Polícia Federal e construção institucional. In: Corrupção e sistema político no Brasil. Edited by AVRITZER, Leonardo and FIGUEIRAS, Fernando. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira. pp. 99-132.), it is nonetheless difficult to gain access to the performance of control institutions, especially in developing countries (SANTISO, 2007SANTISO, Carlos (2007), Auditing for accountability? Political economy of government auditing and budget oversight in emerging economies. Doctoral thesis. Postgraduate Program in Philosophy. The Johns Hopkins University.). As noted by Speck (1999)SPECK, Bruno Wilhelm (1999), The Federal Court of audit in Brazil. Paper presented in 9th International Anti-Corruption Conference, Durban, South Africa., in reference to the Brazilian case, the study of control institutions is even rarer when compared to research on the decision-making process or parties and voting behavior.

Hence, there is insufficient research on the Brazilian web of accountability institutions. The literature does not sufficiently investigate how well these institutions fulfill their accountability roles as part of a larger web. The Brazilian version of the Transparency International Source Book, for example, does not dedicate enough space to the consideration of interactions among different Brazilian accountability institutions (SPECK, 2002SPECK, Bruno Wilhelm (ed) (2002), Caminhos da transparência: análise dos componentes de um sistema nacional de integridade. Campinas: Editora Unicamp. 224 pp..). Mainwaring and Welna (2003)MAINWARING, Scott and WELNA, Christopher (eds) (2003), Democratic accountability in Latin America.. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 360 pp.. and Power and Taylor (2011)POWER, Timothy J. and TAYLOR, Matthew M. (eds) (2011), Corruption and democracy in Brazil: the struggle for accountability. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. 328 pp.. have identified the growing need in the Political Science field for comprehensive approaches when it comes to understanding accountability processes. Nevertheless, their analysis of the interactions among accountability institutions is in an incipient stage of exploration. The authors tend to focus on each accountability institution separately, and therefore lack more detailed and deeper analysis on the links that have been established between them. This paper intends to fill this gap, by focusing precisely on the interactions among Brazilian accountability institutions: the flow of irregularities and proceedings from one institution to another until timely decisions are reached (or not).

The few studies that have been carried out on this topic have repeatedly argued that Brazilian accountability institutions are unable to better control corruption cases because they are not fully coordinated (ARANTES, 2011ARANTES, R. (2011), Polícia Federal e construção institucional. In: Corrupção e sistema político no Brasil. Edited by AVRITZER, Leonardo and FIGUEIRAS, Fernando. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira. pp. 99-132.; AVRITZER and FILGUEIRAS; 2010AVRITZER, Leonardo and FILGUEIRAS, Fernando (2010), Corrupção e controles democráticos no Brasil. In: Estado, instituições e democracia: república. Livro 09. Edited by CUNHA, Alexandre dos Santos; MEDEIROS, Bernardo Abreu de, and AQUINO, Luseni Maria C . de. Brasília: IPEA. pp. 473-504.; LOUREIRO, 2011LOUREIRO, Maria Rita (coord) (2011), Projeto pensando o Direito: coordenação do sistema de controle da administração pública federal. Cadernos do Ministério da Justiça. Vol. 33.; MAINWARING and WELNA, 2003MAINWARING, Scott and WELNA, Christopher (eds) (2003), Democratic accountability in Latin America.. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 360 pp..; TAYLOR, 2011TAYLOR, Matthew M. (2011), The Federal Judiciary and Electoral Courts. In: Corruption and democracy in Brazil: the struggle for accountability. Edited by POWER, Timothy J. and TAYLOR, Matthew M.. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. pp. 162-83.; TAYLOR and BURANELLI, 2007TAYLOR, Matthew M. and BURANELLI, Vinícius C. (2007), Ending up in Pizza: accountability as a problem of institutional arrangement in Brazil. Latin American Politics and Society. Vol. 49, Nº 01, pp. 59-87.; SPECK, 2002SPECK, Bruno Wilhelm (ed) (2002), Caminhos da transparência: análise dos componentes de um sistema nacional de integridade. Campinas: Editora Unicamp. 224 pp..). These studies have shown that the Brazilian institutions of horizontal accountability are, internally, sufficiently well-structured to perform their statutory duties; but there is a pressing need to create mechanisms of coordination between them. Furthermore, the Brazilian accountability web concentrates an enormous emphasis on the investigative phase and in a competitive way, only to meet with the lack of attention devoted to the monitoring or sanction phases of the accountability process – the penalties from the Judiciary are carried out so slowly that they could be considered virtually non-existent (LOUREIRO, 2011LOUREIRO, Maria Rita (coord) (2011), Projeto pensando o Direito: coordenação do sistema de controle da administração pública federal. Cadernos do Ministério da Justiça. Vol. 33.; POWER and TAYLOR, 2011POWER, Timothy J. and TAYLOR, Matthew M. (eds) (2011), Corruption and democracy in Brazil: the struggle for accountability. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. 328 pp..; TAYLOR and BURANELLI, 2007TAYLOR, Matthew M. and BURANELLI, Vinícius C. (2007), Ending up in Pizza: accountability as a problem of institutional arrangement in Brazil. Latin American Politics and Society. Vol. 49, Nº 01, pp. 59-87.). With those diagnoses in mind, in the next section I examine the six Brazilian accountability institutions under analysis, in respect to their roles and responsibilities in the accountability web. The purpose is to provide a benchmark against which we can further compare the performance of Brazilian accountability institutions, in terms of coordination.

The accountability institutions under analysis

Brazil has a broad set of accountability institutions that aim to implement mechanisms for preventing, detecting, punishing, and eradicating corrupt acts (OEA, 2012OEA, Organização dos Estados Americanos (2012), Final report on implementation in the Federative Republic of Brazil of the convention provision. Washington, D.C. Available at: http://www.oas.org/juridico/pdfs/mesicic4_bra_en.pdf. Accessed on August 01, 2016.

http://www.oas.org/juridico/pdfs/mesicic...

). They differ from each other on four main dimensions: scope, autonomy, proximity and activation (POWER and TAYLOR, 2011POWER, Timothy J. and TAYLOR, Matthew M. (eds) (2011), Corruption and democracy in Brazil: the struggle for accountability. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. 328 pp..). The scope dimension aggregates the responsibilities attributed to an institution and the effect these responsibilities have on the institution's reach. The autonomy dimension focuses on the institution's ability to choose what cases to address and how to prioritize its efforts, as well as its ability to act without undue concern for the reactions of other institutions. Thirdly, it is important to distinguish which institutions are proximate – which ones must closely and frequently interact. Finally, the activation dimension deals with whether an institution can act proactively or whether it instead reacts directly to others.

Most of the Executive bureaucracies in Brazil – such as the CGU and the Federal Police – are not very autonomous and tend to have a narrow scope of action. They also rely heavily on proximate institutions to carry forward any investigation. In the case of the Federal Police, it is empowered to investigate criminal offenses, but with no authority to adopt any kind of sanction. In Brazil, criminal cases progress in a triangular way: they are opened by public prosecutors, which depend on police investigations, which, in their turn, require judicial authorizations (ARANTES, 2011ARANTES, R. (2011), Polícia Federal e construção institucional. In: Corrupção e sistema político no Brasil. Edited by AVRITZER, Leonardo and FIGUEIRAS, Fernando. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira. pp. 99-132.; SADEK and CAVALCANTI, 2003SADEK, Maria Tereza and CAVALCANTI, Rosângela (2003), The new Brazilian public prosecution: an agent of accountability. In: Democratic accountability in Latin America. Edited by MAINWARING, Scott and WELNA, Christopher. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 201-227.; TAYLOR and BURANELLI, 2007TAYLOR, Matthew M. and BURANELLI, Vinícius C. (2007), Ending up in Pizza: accountability as a problem of institutional arrangement in Brazil. Latin American Politics and Society. Vol. 49, Nº 01, pp. 59-87.). The literature has reported a huge tension on this triangle, especially between the PF and MPF when it comes to corruption scandals strongly monitored by the media (ARANTES, 2011ARANTES, R. (2011), Polícia Federal e construção institucional. In: Corrupção e sistema político no Brasil. Edited by AVRITZER, Leonardo and FIGUEIRAS, Fernando. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira. pp. 99-132.).

The Federal Police is a permanent body, with clear rules for access, hierarchy and ascension. Its main functions include investigating crimes against the political and social orders; protecting services and interests of the Union; preventing drug trafficking; and investigating crimes that have federal or inter-state repercussion, with sub-national and international jurisdictions. The PF has been involved in many corruption investigative operations, targeting all levels and branches of government (ARANTES, 2011ARANTES, R. (2011), Polícia Federal e construção institucional. In: Corrupção e sistema político no Brasil. Edited by AVRITZER, Leonardo and FIGUEIRAS, Fernando. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira. pp. 99-132.). In the last years, at least eight of its large operations against fraudulent public tenders and public embezzlement involved cross-institutional cooperation, which began as a result of special audits from the CGU. This means that CGU reports can be thought of as the starting point for the activation of investigations carried out by other accountability institutions of the web.

Since 2003, CGU is the main institution of the internal control of the Executive. Its responsibilities include providing advice directly and immediately to the President on matters of preventing and combating corruption, as well as increasing transparency, the protection of public properties, and the Executive internal control. During the last decade, corruption became part of the CGU agenda and a number of authors consider this the main Brazilian anti-corruption agency (CORRÊA, 2011CORRÊA, Izabela (2011), Sistema de integridade: avanços e agenda de ação para a Administração Pública Federal. In: Corrupção e sistema político no Brasil. Edited by AVRITZER, Leonardo and FIGUEIRAS, Fernando. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira. pp. 163-190.; SANTOS, 2009SANTOS, Romualdo Anselmo dos (2009), Institucionalizing anti-corruption: a Brazilian case of institutional origin and change. Paper presented at World Congress of Political Science, Santiago, Chile.). Given the Comptroller's limited scope, when an irregularity is detected by an internal control agent, it must be forwarded to the competent bodies – such as the Federal Court of Accounts or federal prosecutors. The CGU key role in the web is not related to the enforcement of the rule of law, but it is rather a reliable source of information over the use of federal resources to the rest of the accountability web.

Currently, each Brazilian Ministry may have a specific advisor of internal control. These advisors have a dual role in the web: to assist the Ministry in the management of public policies and also to assist the institution in matters of legality, legitimacy, and economy. The most common complaint from the advisors regarding the web of accountability institutions in Brazil is related to the huge amount of demands put forward by the control institutions, to which they are not fully qualified to answer (LOUREIRO, 2011LOUREIRO, Maria Rita (coord) (2011), Projeto pensando o Direito: coordenação do sistema de controle da administração pública federal. Cadernos do Ministério da Justiça. Vol. 33.).

The government Ministries and the Federal Court of Accounts (TCU) are able to deal with irregularities in the management of public resources by opening an administrative proceeding called 'Special Account Process' (Tomada de Contas Especial, TCE). This is a duly formalized process, aimed to determine liability in cases of damages to the federal government and to obtain financial compensation. The TCE is initiated by the competent authority (usually the one responsible for the resource management, such as the government Ministries), but it can also be instated following recommendations of the internal control (CGU) or in response to the decision of the external control (TCU).

The Federal Court of Accounts is the main institution responsible for monitoring public spending in Brazil. It is dedicated to improving management of the public sector in a way that limits opportunities for corruption (MELO at al., 2009MELO, Marcus André; PEREIRA, Carlos, and FIGUEIREDO, Carlos Maurício(2009), Political and institutional checks on corruption: explaining the performance of Brazilian audit institutions. Comparative Political Studies. Vol. 42, Nº 09, pp. 1217-1244.; SANTISO, 2007SANTISO, Carlos (2007), Auditing for accountability? Political economy of government auditing and budget oversight in emerging economies. Doctoral thesis. Postgraduate Program in Philosophy. The Johns Hopkins University.). The TCU's central task is to provide an independent review of government expenditures and to confirm their legality, accuracy and reliability1 1 TCU decides on the accounts of persons responsible for public resources, goods and values; investigates and deliberates on the responsibility involved in cases of loss, embezzlement, or other irregularities that result in damage to the public treasury. It also decides on the legality, legitimacy and economy of management actions and the expenses incurred. It can impose fines and other sanctions. .

The TCU can be considered proactive, but its scope is restricted by strictly regimented audit procedures. Furthermore, historically, it has little practical autonomy from politicians – it is often criticized for being too porous to political pressures, since its Ministers take office by political appointment. This institution does not rely on proximate institutions to pursue its own administrative investigations (SPECK and NAGEL, 2002SPECK, Bruno Wilhelm and NAGEL, José (2002), A fiscalização dos recursos públicos pelos Tribunais de Contas. In: Caminhos da transparência: análise dos componentes de um sistema nacional de integridade. Edited by SPECK, Bruno Wilhelm. Campinas: Editora Unicamp Campinas: Editora da Unicamp. pp. 102-115.), being empowered to make independent decisions on administrative matters regarding public expenditures. Nevertheless, its decisions can be challenged by other institutions with overlapping powers, and the accused can, for instance, question TCU decision by appealing to the Judiciary (SPECK, 2011SPECK, Bruno (2011), Auditing institutions. In: Corruption and democracy in Brazil. Edited by POWER, Timothy and TAYLOR, Matthew. University of Notre Dame Press. p. 127-161.; TAYLOR and BURANELLI, 2007TAYLOR, Matthew M. and BURANELLI, Vinícius C. (2007), Ending up in Pizza: accountability as a problem of institutional arrangement in Brazil. Latin American Politics and Society. Vol. 49, Nº 01, pp. 59-87.). Given this possibility, the TCU has focused its attention on second-best, compensatory administrative sanction mechanisms in order to escape the weakness of the Judiciary in enforcing civil or criminal penalties (TAYLOR and BURANELLI, 2007TAYLOR, Matthew M. and BURANELLI, Vinícius C. (2007), Ending up in Pizza: accountability as a problem of institutional arrangement in Brazil. Latin American Politics and Society. Vol. 49, Nº 01, pp. 59-87.).

There are three types of legal punishment that can be imposed on someone engaged in corruption in Brazil: administrative, civil and criminal -- determined by separate judicial or administrative actions that run independently from one another2 2 Brazilian Law nº 8.112/90, art. 125. . While the TCU is the main body regarding the administrative arena, the MPF assumes the main role when it comes to investigating corruption in the judicial arena.

The Federal Public Prosecutor's Office is the most unusual accountability institution in Brazil. It is a prosecutorial body, formally independent of the other three branches of government, with a guaranteed budget and career incentives set with almost no outside interference. It has the same prerogatives of the Judiciary, such as lifelong tenure, irremovability from office and irreducibility of earnings. The noteworthy autonomy and scope of the MPF are almost unlimited. Because of this, the MPF has been informally referred to as the 'fourth governmental power' (SADEK and CAVALCANTI; 2003SADEK, Maria Tereza and CAVALCANTI, Rosângela (2003), The new Brazilian public prosecution: an agent of accountability. In: Democratic accountability in Latin America. Edited by MAINWARING, Scott and WELNA, Christopher. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 201-227.; SPECK, 2002)SPECK, Bruno Wilhelm (ed) (2002), Caminhos da transparência: análise dos componentes de um sistema nacional de integridade. Campinas: Editora Unicamp. 224 pp... By using (or abusing) this high level of autonomy, the federal prosecutors have turned the MPF into a real political force: actively participating in political disputes, questioning social policies as well as exposing corruption (ARANTES, 2011ARANTES, R. (2011), Polícia Federal e construção institucional. In: Corrupção e sistema político no Brasil. Edited by AVRITZER, Leonardo and FIGUEIRAS, Fernando. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira. pp. 99-132.).

Precisely due to this proactive role, the MPF is perceived with extreme suspicion by members of other accountability institutions. It is often criticized for using the media to impose reputational costs, for infringing upon investigative powers of the Federal Police in addition to exceeding the scope of investigations to pressure politicians, administrators and citizens (ARANTES, 2011ARANTES, R. (2011), Polícia Federal e construção institucional. In: Corrupção e sistema político no Brasil. Edited by AVRITZER, Leonardo and FIGUEIRAS, Fernando. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira. pp. 99-132.). The MPF depends on the Judiciary for the establishment of sanctions - the Judiciary ultimately decides about judicial punishment, and might even correct possible abuses of prosecutors (SADEK and CASTILLO, 1998SADEK, Maria Tereza and CASTILHO, Ela V. (1998), O Ministério Público Federal e a Administração da Justiça no Brasil. São Paulo: Editora Sumaré, Banespa. 40 pp..; TAYLOR and BURANELLI, 2007TAYLOR, Matthew M. and BURANELLI, Vinícius C. (2007), Ending up in Pizza: accountability as a problem of institutional arrangement in Brazil. Latin American Politics and Society. Vol. 49, Nº 01, pp. 59-87.).

Despite its broad mandate to intervene in a number of potential arenas, the Judiciary is a reactive institution and its effectiveness in the accountability process relies heavily on proximate institutions, especially in respect to the quality of the cases forwarded by the MPF (POWER and TAYLOR, 2011POWER, Timothy J. and TAYLOR, Matthew M. (eds) (2011), Corruption and democracy in Brazil: the struggle for accountability. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. 328 pp..). For some scholars, the Judiciary has the most important role in the accountability web, since it represents the last link of a series of accountability relationships (TAYLOR and BURANELLI, 2007TAYLOR, Matthew M. and BURANELLI, Vinícius C. (2007), Ending up in Pizza: accountability as a problem of institutional arrangement in Brazil. Latin American Politics and Society. Vol. 49, Nº 01, pp. 59-87.). If it happens not to properly rule on cases in a timely manner, it basically throws away the monitoring and investigating work carried out by other institutions of the web.

The main responsibility of the Federal Justice in Brazil is to decide on cases involving the Union or foreign entities, international treaties, and crimes against the financial system and the economic order. Its role is to rule on the responsibility of the indicted defendants and to impose legal sanctions on politicians involved in corrupt practices. There are several criticisms being directed at the performance of the Brazilian Judiciary, such as the extensive possibility of appeals and the 'special' public employees, who are afforded the right to be judged by a privileged 'forum by prerogative of office'. This privileged forum protection many times result in immunity to politicians involved in corruption scandals (TAYLOR, 2011TAYLOR, Matthew M. (2011), The Federal Judiciary and Electoral Courts. In: Corruption and democracy in Brazil: the struggle for accountability. Edited by POWER, Timothy J. and TAYLOR, Matthew M.. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. pp. 162-83.). The literature tends to agree that the Judiciary remains a core weakness in the Brazilian accountability system, especially due to the lack of timely punishment in corruption cases (AVRITZER and FILGUEIRAS, 2010AVRITZER, Leonardo and FILGUEIRAS, Fernando (2010), Corrupção e controles democráticos no Brasil. In: Estado, instituições e democracia: república. Livro 09. Edited by CUNHA, Alexandre dos Santos; MEDEIROS, Bernardo Abreu de, and AQUINO, Luseni Maria C . de. Brasília: IPEA. pp. 473-504.; OEA, 2012OEA, Organização dos Estados Americanos (2012), Final report on implementation in the Federative Republic of Brazil of the convention provision. Washington, D.C. Available at: http://www.oas.org/juridico/pdfs/mesicic4_bra_en.pdf. Accessed on August 01, 2016.

http://www.oas.org/juridico/pdfs/mesicic...

; TAYLOR, 2011)TAYLOR, Matthew M. (2011), The Federal Judiciary and Electoral Courts. In: Corruption and democracy in Brazil: the struggle for accountability. Edited by POWER, Timothy J. and TAYLOR, Matthew M.. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. pp. 162-83..

This is the framework behind the interactions in the Brazilian accountability web. At this point, it is truly necessary to clarify that controlling corruption is not the only function of the Brazilian web of accountability institutions. But whenever one of the accountability institutions finds corruption, the case must be addressed properly. The following section clarifies the definition of corruption employed in this paper.

Corruption versus mismanagement

In recent decades, the research agenda on corruption in terms of empirical approaches has followed two very different paths. On the one hand, there are scholars who study it through aggregate perception measures – such as the Corruption Perception Index from Transparency International. This measure, which is widely used, assigns corruption scores to each country, in attempt to identify broader trends and contrasts. The problem with this approach is that corruption perceptions in general are not highly correlated with the concrete experiences of citizens, which casts the suspicion that the perceptions are biased (BOHN, 2012BOHN, Simone R. (2012), Corruption in Latin America: understanding the perception–exposure gap. Journal of Politics in Latin America. Vol. 04, Nº 03, pp. 67-95.). The indicators constructed from these perceptions are, in fact, subjective measures of the corruption level3 3 For further critique on corruption perception measures, see also Abramo (2005). . On the other hand, there are scholars dedicated to in-depth analysis of the phenomenon, carrying out detailed case studies that highlight how corruption is a process immersed in complex human interactions, which do not allow comparisons that transcend time and space. It is common to see the study of major corruption scandals which receive special media attention in this second group (CHAIA and TEIXEIRA, 2001CHAIA, Vera and TEIXEIRA, Marco Antonio (2001), Democracia e escândalos políticos. São Paulo em Perspectiva. Vol. 15, Nº 04, pp. 62-75.; TAYLOR and BURANELLI, 2007TAYLOR, Matthew M. and BURANELLI, Vinícius C. (2007), Ending up in Pizza: accountability as a problem of institutional arrangement in Brazil. Latin American Politics and Society. Vol. 49, Nº 01, pp. 59-87.). However, by analyzing solely the scandals that received media attention, this approach fails to report on cases that are not investigated. Selections based on the media tend to pick up very particular cases, which usually receive greater priority than usual.

This paper has chosen an alternative path, by selecting more objective measures of the corruption phenomenon – namely, the irregularities encountered by an accountability institution. But it is necessary to point out that in CGU reports there is an ample spectrum of irregularities, which do not only refer to corruption. Among scholars who use CGU reports as an approximate measure of corruption, there is at least a significant distinction between corruption and mismanagement (FERRAZ and FINAN, 2008FERRAZ, Claudio and FINAN, Frederico (2008), Exposing corrupt politicians: the effects of Brazil's publicly released audits on electoral outcomes. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. Vol. 123, Nº 02, pp. 703-745., 2011FERRAZ, Claudio and FINAN, Frederico (2011), Electoral accountability and corruption: evidence from the audits of local governments. American Economic Review. Vol. 101, Nº 04, pp. 1274-1311.). In order to accomplish this basic distinction, I use the non-trivial definition of corruption proposed by Warren (2004WARREN, Mark E. (2004), What does corruption mean in a democracy? American Journal of Political Science. Vol. 48, Nº 02, pp. 328-343., 2006WARREN, Mark E. (2006), Democracy and the state. In: The Oxford handbook of political theory. Edited by DRYZEK, John S.; HONIG, Bonnie, and PHILLIPS, Anne. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 382-399.), and its four basic features:

-

Collective decisions are entrusted to a group or individual;

-

There are rules that regulate how the group/individual can use their power to make these decisions (in a democracy this is the inclusive rule);

-

The group/individual breaks this rule;

-

Breaking the rule benefits the individual/group and harms the community.

Brazilian municipal governments are entrusted the power to implement collective decisions (regarding federal policies), and this implementation must be guided by the norm of inclusion. This inclusion is broken when municipal officials deviate from the norms, laws and expectations of their positions. This is consistent with the most usual way of understanding corruption: "the behavior which deviates from the formal duties of a public role because of private regarding, pecuniary or status gains, or violates rules against the exercise of certain types of private-regarding influence" (NYE, 1967NYE, Joseph (1967), Corruption and political development: a cost-benefit analysis. American Political Science Review. Vol. 61, Nº 02, pp. 417-427., p. 417). But this paper also highlights the political exclusions involved in corrupt acts – something missing in Nye's definition.

Failures related to poor management – which point to managerial incapacity and waste of resources – and those related to corruption involve a dimension of social exclusion, since both failures prevent citizens from accessing public goods and services to which they are entitled. But the boundary that separates corruption from mismanagement is the political aspect of the exclusion. Corruption generates a private benefit which is, from a democratic point of view, illegitimate for benefiting some at the expense of decisions made by the political community.

Corruption is understood here as intrinsically connected to the ability to provide public justification for the political conduct: "we hide our corrupt acts from others because we are trying to keep them from realizing that they are excluded from transactions" (USLANER, 2008USLANER, Eric M. (2008), Corruption, inequality, and the rule of law: the bulging pocket makes the easy life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 360 pp.., p. 09). For corruption, there is no plausible justification; poor management, in contrast, can be publicly justified and even accepted by overseeing agencies – and this is a crucial point for this paper.

CGU reports from the Lottery program provide the justifications given by the mayors for the irregularities found, including the acceptance (or not) of these justifications by the auditors. The analysis of the reports makes it possible to divide the irregularities into those that can be publicly justified and those that cannot (classified as corruption). For example, it is common for the municipal administrations to conduct bidding processes without following all the formalities predicted by the specific Law. In general, the CGU advises the mayor to manage the federal resources in a better way, but this is not a good enough reason for CGU to suggest the opening of an administrative proceeding, for example. On the other hand, the reports reveal cases of mayors who, in the last day of their mandate, withdrew all the money from the municipality bank account and disappeared - in such cases the CGU does not accept the justifications provided. I compare irregularities related to corruption with those related to mismanagement, always pointing out that, among those encompassed in the corruption side, are irregularities linked to some kind of private (inappropriate) benefit, which is publicly unjustifiable.

Based on CGU reports, I have used a longitudinal research approach, keeping track of the irregularities found over time, until they reached (or not) the Judiciary.

Methodology

The longitudinal approach

The traditional method for reconstituting the flow of control systems is the longitudinal method. This type of analysis monitors a set of cases, from the record of their occurrence to a specific point, over a certain period of time. Such monitoring aims to determine the percentage of cases progressing to subsequent stages. In this paper, the individual and progressive monitoring of irregularities as they advance in the stages of accountability allows the direct count of how many and which kind of cases are investigated and/or prosecuted. I have tracked the irregularities found by CGU, from the beginning of the Lottery Program, in 2003 until 2015. I tracked the proceedings opened by the accountability institutions under analysis (TCU, government Ministries, MPF, PF and JF) and searched for specific information that could allow me to perfectly trace them back to the Lottery Program4 4 For the matching, I used the mayor's name, the year of the proceeding, the governmental program and the description of the irregularity. Only the proceedings that could be clearly traced back to the Lottery Program were included in the dataset. .

The longitudinal approach has been considered the most suitable to map the flow of control systems. However, studies on the web of accountability institutions in Brazil have not used longitudinal methods to draw their conclusions about the interactions and, in this sense, this paper represents a breakthrough - the dataset used here is one of the few sources of information that brings together official data within a longitudinal perspective in Brazil. In the next section, I explain how the data was collected and how the interactions under analysis were submitted to a test.

The Lottery Program as a test

In order to test how Brazilian accountability institutions interact when they encounter corruption cases, I examined the audits conducted by the CGU in the Brazilian local governments. I was especially interested in the program called 'Inspections from Public Lotteries', which randomly targets the federal funds transferred to municipalities with less than 500,000 inhabitants. At present, there are more than 5,500 municipalities in Brazil, over 80% of which survive thanks to the compulsory or voluntary transfers made by the Union. Under Brazilian law, the transferring agency must ensure that there has been proper and regular use of the transferred funds. Therefore, the federal institutions, including the CGU, have to demand accountability from the local governments for the use of the transferred federal resources.

The Lottery program has brought a significant increase in the disclosure of government data regarding irregularities in municipal management of federal funds5 5 The reports are publicly available at www.cgu.gov.br. . The reports represent an unprecedented gathering of information about municipal management from a single source, and have certainly advanced the production of academic research on public policy, municipal management and corruption incidence6 6 For papers based on CGU reports, see Ferraz and Finan (2008, 2011). .

In its Lottery Program, every month the Comptroller sends approximately 10 auditors to 60 randomly-selected municipalities across all 26 Brazilian states in order to examine the allocation of federally-transferred funds, to inspect the quality and completion of public construction work, and to conduct interviews with key members of civil society. The auditors search for irregularities involving federal resources that have been transferred up to two years prior to the visit. Each visit results in a detailed audit report documenting any irregularity associated with either federal transfers or federally-funded social programs, the justifications presented by the mayors and the acceptance (or not) of the justification by CGU auditors. The reports are then forwarded to the competent bodies that may establish administrative or legal sanctions.

This paper is concerned whether the other accountability institutions of the web make use of the reports and decide to act upon them (to open proceedings), and whether (and how long it takes for) these proceedings (to) arrive at the Judiciary. In order to answer these questions, I map all three stages of accountability, from monitoring (the CGU identifies irregularities), investigating (other institutions decide to open proceedings), until the final stage, in which appropriate sanctions are determined. It is important to stress that, since the Lottery Program is a CGU initiative, the other accountability institutions are under no obligation whatsoever to incorporate such findings and conduct investigations because of them. Accountability institutions have discretion to assess what they believe to be relevant and what deserves their attention. However, each institution has a wide spectrum of situations that instigate the interactions, and if an institution starts a program like the Lottery Program, (at the cost of many human and economic resources in auditing around the country), it is expected that its reports are not going to be dismissed, and that some action, or some systematic relationship, is going to be adopted across the institutions that receive the reports. I consider that an interaction between institutions has occurred when I find that a proceeding concerning irregularities contained in CGU reports has been opened by other institutions of the web. The existence of a proceeding means that the other institution has, at least, read the reports, deemed them worthy of attention and sufficiently well-structured to initiate investigations.

From the literature, it is possible to arrive at some observable implications about what we should expect when it comes to interactions among accountability institutions in Brazil. In the first place, it is reasonable to expect an absence of interactions between the Brazilian accountability institutions or, at least, to expect interactions in a non-coordinated way. This would translate into a low percentage of irregularities turned into administrative or judicial processes. It is true that not every kind of irregularity can be processed both by the administrative and judicial institutions at the same time. The Ministries can only act on administrative matters, and forward the cases to the TCU, which can decide alone on administrative issues. If a case that is being investigated by the Court of Accounts arrives at the Federal Justice, it is only because something has gone wrong with the case (the administrative decision is challenged at the judicial arena). In contrast, the MPF needs to take its cases to the Justice. So the interactions are different for each of the institutions in question. But the important point is that CGU information is able to trigger both arenas – administrative and judicial. The question is: once CGU monitors and finds irregularities, do the other institutions use this information and investigate it or is this information dismissed? How long do they take to start the proceedings? And once started, how long do they take until a final decision is reached?

The next Figure shows the flux reconstructed here, which has the Lottery program as the starting point:

The flow of control steps by federal accountability institutions overseeing local governments, Brazil, 2015

Results

From the very beginning of the Lottery program in 2003 to 2010, the Comptroller had inspected 1,581 municipalities (28.4% of Brazilian municipalities)7 7 The criteria selection for this time period was the year in which the program began (2003) to the year before the program makes a long interruption (2010). Currently the program is under revision and may be abolished. . From this total, a random sample was calculated, stratified by state and year of inspection, which resulted, with a confidence level of 95%, in the study of 322 Brazilian municipalities. This paper takes into consideration each irregularity found in these municipalities (a total of 19,177 irregularities), and analyzes the extent to which they generate proceedings from the administrative and judicial arenas, until the year of 20158 8 The sample contains municipalities monitored from 2003 to 2010, but I followed the irregularities in the accountability web until 2015 – allowing at least 05 years for the establishment of proceedings. This time frame is particularly interesting because during the entire period Brazil was governed by the same political party (PT), who had a strong agenda of reinforcing accountability institutions. In 2016, for example, the CGU has suffered major structural changes which will need to be considered by future researches on the topic. . As CGU inspection reports are sent to the entire Federal Public Administration, it can be assumed that the other institutions are aware of the irregularities encountered. In order to investigate reactions across the web of accountability, I first looked specifically at irregularities that had generated reactions at the Federal Court of Accounts and at the Public Prosecutor's Office.

Do the institutions interact? The flux of accountability interactions

In the dataset, only 2.8% of the irregularities had generated TCEs, of which only 7.4% were installed by the TCU. This shows that the irregularities brought by the Comptroller are hardly the subject of proceedings initiated by the external control. On the other hand, 91.6% of the TCEs were initiated by the government Ministries, which then forwarded the proceedings to the Court of Accounts for administrative judgment. On the other hand, the scenario on the judicial arena is quite different. The Public Prosecutor's Office has a more active role than the administrative arena – there are 9,666 irregularities under investigation by the MPF. In total, 9,957 irregularities (52%) were targeted by some investigation, and 1,494 reached the Federal Justice (7.8%). This means two things: the investigative stage had a huge effect and the Federal Justice was somewhat active – when compared, for example, with the 10% of homicides that are prosecuted by the Brazilian Judicial system (RIBEIRO, 2010RIBEIRO, Ludmila (2010), A produção decisória do sistema de Justiça Criminal para o crime de homicídio: análise dos dados do Estado de São Paulo entre 1991 e 1998. DADOS. Vol. 53, Nº 01, pp. 159-194.).

The novelty of these results is that they clearly indicate which institutions are more active than others – which is something new in the literature. But it is possible to suppose that there may be something particular that drives the focused action of the administrative arena, such as the kind of irregularity in question.

What drives the interactions? The influence of corruption

In total, 4,870 irregularities were considered corruption (25.4%). Statistically testing the effect of the type of irregularity in the decision to open a proceeding – through four binary logistic regressions shown in Table 02 – it is possible to conclude that an irregularity classified as corruption has the chance of becoming a TCE increased by 02, and of becoming a TCU investigation by 2.25. Meanwhile, the chances are increased by only 1.25 for MPF investigations. Overall, the presence of corruption increases the chances of investigation, but this effect is stronger for the administrative arena.

This finding recalls the literature about the lack of coordination in the Brazilian web of accountability institutions: the fight against corruption seems to be approached differently by each institution, and there seems to be no coordination between them about the priority that should be given to this phenomenon. Given public prosecutors high degree of autonomy, they can individually choose to prioritize different types of irregularities, especially during the investigative phase. On the other hand, corruption cases have higher chances of being sent to the Federal Justice – the fact that an irregularity is considered corruption increases its chances to arrive at the Federal Justice by 80%. But even if corruption cases have more chances to trigger the accountability investigative phase, are they related to faster sentencing? Do they receive a timely sentence once they arrive at a judging institution?

Time as a crucial variable in the Brazilian web of accountability institutions

It is reasonable to assume that it takes some time for the other institutions of the web to get comfortable with a new program such as the Lottery, and that it takes a while until they can process the reports produced by another institution. Once they decide to act on CGU reports, the proceedings must undergo a certain series of investigation and trials, and the time required for these actions may vary from one institution to another. This posits the question of how long it takes for the proceedings to be started - from the Lottery report to the start of proceedings by other accountability institutions.

I created a new variable that subtracts the year of the beginning of the proceeding from the year in which the irregularity was discovered. In the case of the administrative arena, the average was 5.4 years (Table 03). This poses serious problems for the accountability web, especially considering that mayors political terms last four years in Brazil. The lack of agility in the starting of TCE proceedings gives enough time for representatives holding office to commit irregularities and leave their political positions without fearing any administrative sanction. The literature on these institutions should be discussing not only the slowness of the Judiciary, but also the slowness of the accountability system as a whole, including its administrative institutions. In the case of the MPF, its performance has been faster, with an average of 2.55 years' difference between the report and the beginning of the proceeding.

Furthermore, I calculated the time taken to reach a final decision – how many days it took for each institution to internally come to a decision about the irregularities. The days in which the investigation processes remained within the institutions were calculated by subtracting the date of the last movement from the date of the opening9 9 'Last movement' means that the institutions reached a decision about the irregularity: it was archived, acquitted or convicted. . The average for the internal processing time was 995 days for the TCU – a little over two and a half years. On the other hand, inside the MPF the processes run with an average of 712 days between the starting day and the last internal decision. Despite having a greater standard deviation, it seems that, within the Public Prosecutor's Office, the processes run faster than within the Court of Accounts. It is noteworthy that this may be the case because TCU work would require a longer internal procedure when compared to the institution that only prepares the case for trial10 10 Unlike the MPF, the TCU investigates and gives a final judgment about the irregularities. . But even so, the internal work of an institution must have a temporal a limit, so that it is able to reach final decisions in a timely manner.

The literature never ceases to name the Judiciary as the great villain of the accountability web in Brazil, mainly because of its slowness. Surprisingly enough, however, the results are a bit more optimistic for the Federal Justice when compared to the time taken by the TCU, for example. On average, the irregularities arrive at the Federal Justice faster than in the administrative field (one year difference), and the merit may be given to the institutions that initiate the actions: it can be that public prosecutors are faster than the Ministries to identify irregularities and gather evidence about them. This slowness of the TCU when compared to the Federal Justice is also felt in the internal processing – it takes on average 100 days more to reach an opinion about the irregularity. We may need to start reviewing our paradigms in the literature, such as attributing major accountability problems exclusively to the Justice system. In the next section, the survival analysis aims to understand which factors could influence the speed of the web in processing irregularities.

Survival analysis

Survival analysis is a branch of statistics that deals with analysis of time duration until one or more events take place. In this context, death or failure is considered an 'event' – and, usually, only a single event occurs for each subject, after which the organism or mechanism is dead or broken (CARVALHO et al., 2005CARVALHO, Marília Sá; ANDREOZZI, Valeska Lima; CODEÇO, Claudia Torres; CAMPOS, Dayse Pereira; BARBOSA, Maria Tereza Serrano and SHIMAKURA, Silvia Emiko (eds) (2005), Análise de sobrevida: teoria e aplicações em saúde. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Fiocruz. 432 pp..). In this study, the events are the arrival and the judgment of the irregularities at the Federal Justice. I am interested in studying the survival time – the time spent by the irregularities in the Justice system, from an initial time until the occurrence of these two events. The idea is that faster processes generate faster responses to the irregularities, whether exempting or convicting those involved, which would certainly help to reduce the prevailing perception of impunity in Brazil. On the other hand, proceedings that take a long time to be started, or that are not completed, will only reinforce the already widespread idea that corruption is not sanctioned in Brazil.

In the survival analysis, I used the Kaplan-Meier estimator to understand whether corruption irregularities are judged faster11 11 The Kaplan-Meier estimator is one of the non-parametric methods to estimate the survival function. This function is defined as the probability that an individual has of surviving beyond a certain point in time 't'. . The point is that, if the accountability web claim corruption is a major issue – as shown by the logistic regressions –, this web would be expected to make an effort to streamline the processes that deal with this kind of irregularity. The survival curves are presented in a comparative mode: if one survival probability is higher or lower depending on a particular kind of irregularity. The influence of the interactions in the final stage of accountability is also explored – especially in regard to how the interactions established during the investigation stage affect the arrival of the irregularities at the Federal Justice and the speed of the judgments delivered by this institution.

Survival curves of irregularities until the arrival at the Justice, for different levels of irregularity considered corruption, Brazil, 2003-2015

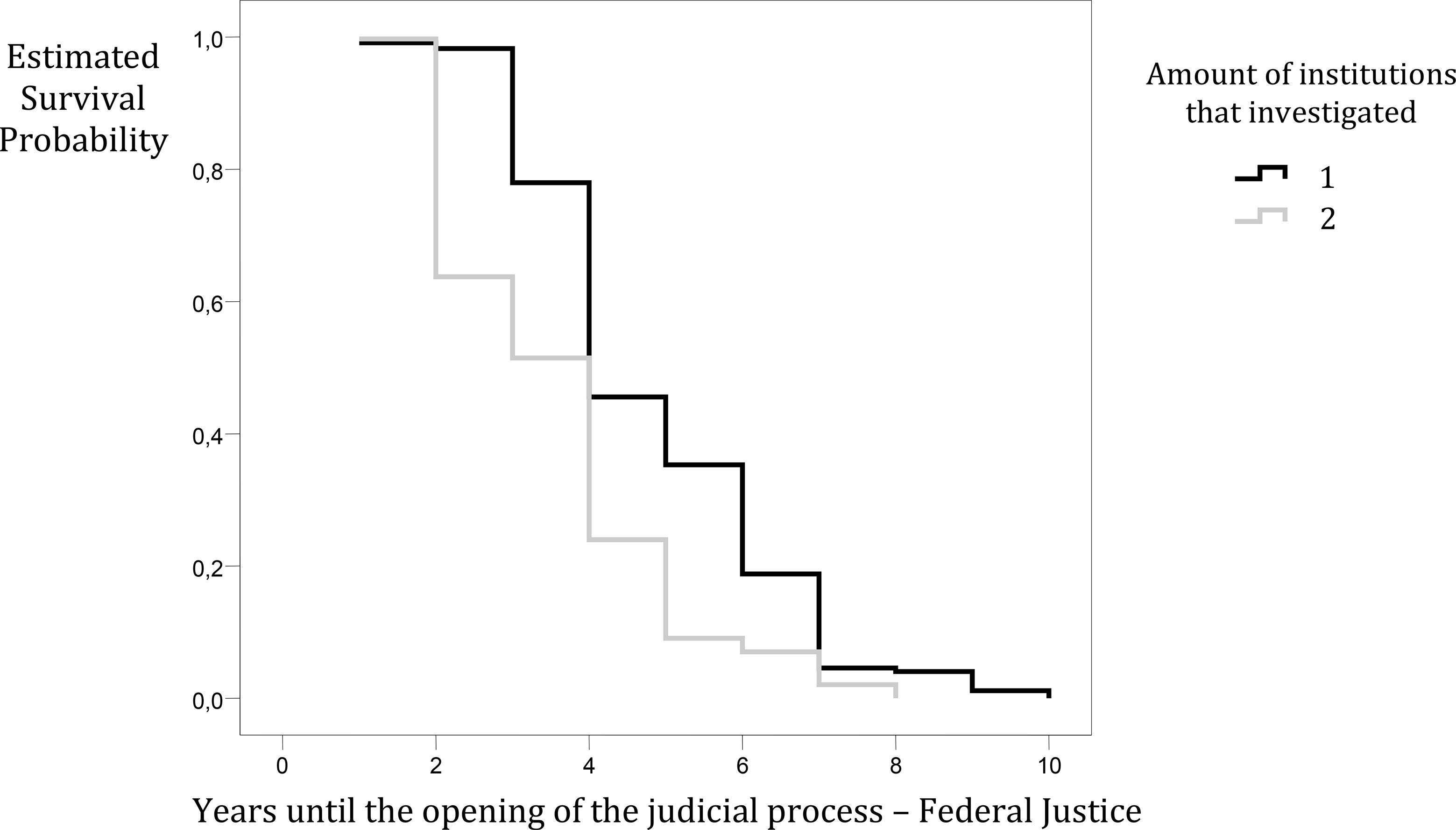

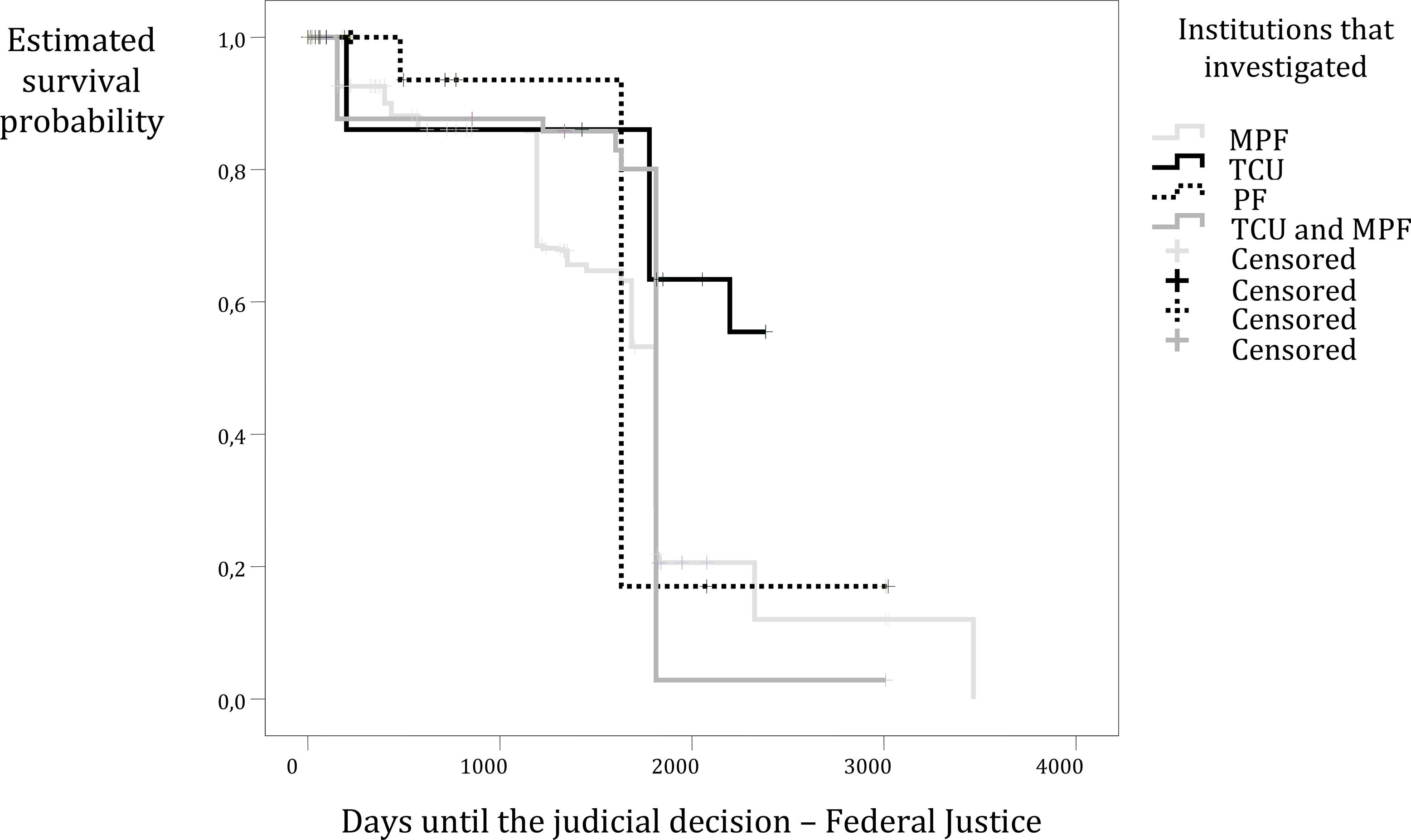

The main event of the three following analyses is the arrival of the irregularity at the Federal Justice; the time variable is the difference in years from the Lottery report to the mentioned arrival; and the comparisons are between the kind of irregularity (considered corruption or not), the amount of institutions that investigated the irregularity (one or two), and the institutions involved in the investigation phase (MPF, TCU, MPF and TCU or PF and another institution).

In the first graph and in the first log-rank test, there is a clear distinction in the two survival curves – 'surviving' in this case means that the irregularity did not reach the Justice system, and the 'death' means that it did12 12 The log-rank test is a hypothesis test to compare the survival distributions of two samples. . In general, cases involving corruption are significantly slower at every point in time – they take a longer amount of time to reach the Federal Justice.

Secondly, the survival of the irregularities is especially affected depending on the institutions that participated in the investigation phase (significant log-rank test). Of all the cases that arrived at the Federal Justice, the investigation processes that heavily relied on the help of the Federal Police tended to arrive much faster than the cases investigated only by the TCU, for instance13 13 The data of the participation of the Federal Police was extracted from the judicial and administrative processes. This means that the category 'PF' indicates the participation of at least two institutions in the investigation (MPF-PF or TCU-PF). . This can be explained largely by the fact that the Federal Police only takes part in criminal cases that already intend to be judicially prosecuted. The TCU, on the other hand, is a strictly administrative body, with no design for or intention of helping the cases to arrive to judicial sanctions. But surprisingly, the processes that relied on the help of the Federal Police were much faster than those investigated only by public prosecutors. It is interesting that the processes in which there was an interaction with the Federal Police spent significantly less time to arrive at the Justice system. It is also interesting that when the Court of Accounts and the Public Prosecutor's Office concomitantly investigated an irregularity, it tended to take a longer time to arrive at the Federal Justice than those investigated only by the prosecutors.

Survival curves of irregularities until arrival at the Justice, for different levels of investigation institutions, Brazil, 2003-2015

Survival curves of irregularities until judicial decision, for different levels of irregularity considered corruption, Brazil, 2003-2015

Survival curves of irregularities until judicial decision, for different levels of amount of investigation institutions, Brazil, 2003-2015

One can also imagine that an irregularity investigated by more than one institution would gather more evidence, thus accelerating its arrival at the stage of judicial sanctions. This hypothesis was confirmed: investigative partnerships indeed reduced the time it took for the irregularity to reach the Judiciary (Table 05 and Graph 03). On average, irregularities investigated without the establishment of partnerships took 4.8 years to reach the Federal Justice, while those investigated by two institutions took an average of 3.5 years.

Survival curves of irregularities until arrival at the Justice, for different levels of amount of investigation institutions, Brazil, 2003-2015

But the major criticism against the web is that the Judiciary takes too long to judge the proceedings that arrive at it. From now on, the event in analysis is the reach of a sentence by the Federal Justice. The time variable is the difference in days between the opening of the proceeding until its judgment. My aim is to check whether the type of irregularity and the number of interactions between institutions affect the time spent by the proceedings inside the Federal Justice.

On average, the irregularities remained 1,741 days inside the Federal Justice before they obtained a sentence. The graph below shows that 90% of the irregularities survived, having reached 1,000 days inside the Justice system without a sentence. From this point onward, there was a sharp drop in survival (many judgments were reached at once). The survival rate stabilized afterward, reaching a new decline at the 2,000 days' mark. Comparing the two types of irregularities, those considered corruption took a longer time to reach a judicial decision (on average 215 days longer).

The average of survival events per institution shows that if the irregularity was monitored by the administrative arena, it took longer to obtain a judgment in the Judiciary than those investigated by the public prosecutors (Table 06 and Graph 05). This was expected: prosecution processes are totally focused on the juridical aspects, which would in turn make them better prepared for a quick trial at the Federal Justice. The log-rank test was significant, indicating that there are relevant differences between the curves. Again, the 2000-day mark appears to be a threshold, as it is when the Judiciary judges the clear majority of cases. The fastest sentences are achieved when the TCU and the MPF perform joint investigations, followed by the MPF performance on its own, the Federal Police and its partner and, finally, the TCU.

Survival curves of irregularities until judicial decision, for different levels of investigation institutions, Brazil, 2003-2015

The following analysis of the survival rates for sentencing in Brazil is revealing. Particularly in the early days of the investigation, the occurrence of partnerships actually delays Justice judgments, and this is a statistically significant difference. Interestingly, this trend is reversed when the curve reaches the 2,000-day mark: after this point, irregularities that relied on partnerships during the investigation stage are sentenced sooner. The fact that the curve of irregularities that were investigated without partnerships tends to be faster (at least in the beginning), calls into question the hypothesis that interactions could reduce the vulnerabilities of the Judiciary. In short, the interactions help the irregularity to arrive faster at the Judiciary, but once they arrive there, they do not contribute to a faster sentencing.

Conclusion

The Brazilian web of accountability institutions has been strengthened and has tried to properly address corruption cases. First of all, it is not true that these institutions do not interact. At least when it comes to the irregularities brought by the internal control, the accountability institutions open proceedings to investigate them. However, it is necessary to consider that the conclusions about the Brazilian web of accountability institutions cannot suppress the different internal relationships found among the institutions. I have found that the Brazilian accountability institutions interact as a result of the Lottery Program (at least in the formal aspect of opening proceedings). The MPF, specifically, interacts more, followed by the Ministries and then the TCU. But the MPF's activism is not necessarily intended for the investigation of corruption, while the TCU presents a focus on this kind of irregularity. In general, the investigative phase concentrates most of the web's attention, and the Federal Justice takes less time to judge in comparison to the Court of Accounts.

Secondly, while corruption may be important in the decision to interact, it is not important enough to expedite the progress of the judicial cases, in fact, it leads to slower processes. Furthermore, the interactions during the investigative stage are fundamental to expedite the arrival of the proceedings at the Judiciary, but do not contribute to faster sentencing. It is possible to presume that corruption cases are difficult to investigate and demand more time to be processed, or even that this kind of irregularity is strategically set aside - if it is true that some of these institutions are porous to external pressures. In any case, this systematic delay in corruption trials only support the claim that the last stage of accountability is a great barrier for a web concerned with corruption control.

It is important to note that any measure of corruption involves unclear boundaries between what should be or should not be enclosed. My form of operationalizing the concept is only one of many interpretations. What allows me to distinguish the actions to be included in the category 'corruption' is precisely the judgments made by the accountability institutions, in terms of what can be publicly justified. In this paper, I have attempted to challenge the common place notion of equating corruption to bribe-taking (the most widespread way of measuring it), connecting it to the exclusions that it entails. Reflections such as these are, however, missing in the corruption literature: corruption is an illegal and illegitimate action from the point of view of democratic inclusion, since it puts equal citizens in a disadvantaged situation that prevents the implementation of public interests, values and perspectives, discussed in democratic forums and put into practice through public policies.

The findings shed light to the intricate accountability interactions in Brazil. They are hardly directly applicable to other Latin American countries. Notwithstanding, it can be said that the agenda of the web of accountability institutions in Latin America has to be attentive to the fact that conclusions about the web have to take into consideration the heterogeneous relationships among institutions within the web (something the literature has persistently missed). The conclusions of this paper are also restricted to the accountability established from the federal institutions to small Brazilian municipalities. CGU monitoring of larger cities and states did come to exist, but suffered much more political pressure, and the reports could not even be found online. In addition, the Lottery Program itself has been suffering in the last two years with lack of resources and is in danger to be eliminated from CGU control activities. This paper highlights the importance of this Program, not only because it has provided a unique opportunity to track the flow of control activities, but especially because it assists other accountability institutions in the discovery of corruption schemes spread around the country. It keeps the local representatives accountable and aware that the federal resources that arrive from far away are not free of oversight.

References

- ABRAMO, Claudio Weber (2005), Percepções pantanosas: a dificuldade de medir a corrupção. Novos Estudos CEBRAP Nº 73, p. 33-37.

- ARANTES, R. (2011), Polícia Federal e construção institucional. In: Corrupção e sistema político no Brasil Edited by AVRITZER, Leonardo and FIGUEIRAS, Fernando. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira. pp. 99-132.

- AVRITZER, Leonardo and FILGUEIRAS, Fernando (2010), Corrupção e controles democráticos no Brasil. In: Estado, instituições e democracia: república Livro 09. Edited by CUNHA, Alexandre dos Santos; MEDEIROS, Bernardo Abreu de, and AQUINO, Luseni Maria C . de. Brasília: IPEA. pp. 473-504.

- BOHN, Simone R. (2012), Corruption in Latin America: understanding the perception–exposure gap. Journal of Politics in Latin America Vol. 04, Nº 03, pp. 67-95.

- CARVALHO, Marília Sá; ANDREOZZI, Valeska Lima; CODEÇO, Claudia Torres; CAMPOS, Dayse Pereira; BARBOSA, Maria Tereza Serrano and SHIMAKURA, Silvia Emiko (eds) (2005), Análise de sobrevida: teoria e aplicações em saúde. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Fiocruz. 432 pp..

- CHAIA, Vera and TEIXEIRA, Marco Antonio (2001), Democracia e escândalos políticos. São Paulo em Perspectiva Vol. 15, Nº 04, pp. 62-75.

- CORRÊA, Izabela (2011), Sistema de integridade: avanços e agenda de ação para a Administração Pública Federal. In: Corrupção e sistema político no Brasil Edited by AVRITZER, Leonardo and FIGUEIRAS, Fernando. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira. pp. 163-190.

- FERRAZ, Claudio and FINAN, Frederico (2011), Electoral accountability and corruption: evidence from the audits of local governments. American Economic Review Vol. 101, Nº 04, pp. 1274-1311.

- FERRAZ, Claudio and FINAN, Frederico (2008), Exposing corrupt politicians: the effects of Brazil's publicly released audits on electoral outcomes. The Quarterly Journal of Economics Vol. 123, Nº 02, pp. 703-745.

- KENNEY, Charles D. (2003), Horizontal accountability: concepts and conflicts. In: Democratic accountability in Latin America. Edited by MAINWARING, Scott and WELNA, Christopher. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 55-75.

- LOUREIRO, Maria Rita; TEIXEIRA, Marco Antonio Carvalho, and MORAES, Tiago Cacique (2009), Democratização e reforma do Estado: o desenvolvimento institucional dos Tribunais de Contas no Brasil recente. Revista de Administração Pública Vol. 43, Nº 04, pp. 739-772.

- LOUREIRO, Maria Rita (coord) (2011), Projeto pensando o Direito: coordenação do sistema de controle da administração pública federal. Cadernos do Ministério da Justiça Vol. 33.

- MAINWARING, Scott (2003), Introduction: democratic accountability in Latin America. In: Democratic accountability in Latin America Edited by MAINWARING, Scott and WELNA, Christopher. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 03-33.

- MAINWARING, Scott and WELNA, Christopher (eds) (2003), Democratic accountability in Latin America. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 360 pp..

- MANZETTI, Luigi and MORGENSTERN, Scott (2003), Legislative oversight: interests and institutions in the United States and Argentina. In: Democratic accountability in Latin America Edited by MAINWARING, Scott and WELNA, Christopher. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 132-169.

- MELO, Marcus André; PEREIRA, Carlos, and FIGUEIREDO, Carlos Maurício(2009), Political and institutional checks on corruption: explaining the performance of Brazilian audit institutions. Comparative Political Studies Vol. 42, Nº 09, pp. 1217-1244.

- MORENO, Erika; CRISP, Brian F., and SHUGART, Matthew Soberg (2003), The accountability deficit in Latin American. In: Democratic accountability in Latin America Edited by MAINWARING, Scott and WELNA, Christopher. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 79-131.

- NYE, Joseph (1967), Corruption and political development: a cost-benefit analysis. American Political Science Review Vol. 61, Nº 02, pp. 417-427.

- OEA, Organização dos Estados Americanos (2012), Final report on implementation in the Federative Republic of Brazil of the convention provision Washington, D.C. Available at: http://www.oas.org/juridico/pdfs/mesicic4_bra_en.pdf Accessed on August 01, 2016.

» http://www.oas.org/juridico/pdfs/mesicic4_bra_en.pdf - O’DONNELL, Guilhermo (2001), Accountability horizontal: la institucionalización legal de la desconfianza política. POSTData Nº 07, pp. 11-34.

- O'DONNELL, Guilhermo (1998), Accountability horizontal e novas poliarquias. Lua Nova Nº 44, pp. 27-54.

- OLIVIERI, Cecília (2011), Combate à corrupção e controle interno. Cadernos Adenauer Vol. XII, Nº 03, pp. 99-109.

- PHILP, M. (2009), Delimiting democratic accountability. Political Studies Vol. 57, Nº 02, pp. 28-53.

- POWER, Timothy J. and TAYLOR, Matthew M. (eds) (2011), Corruption and democracy in Brazil: the struggle for accountability. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. 328 pp..

- RIBEIRO, Ludmila (2010), A produção decisória do sistema de Justiça Criminal para o crime de homicídio: análise dos dados do Estado de São Paulo entre 1991 e 1998. DADOS Vol. 53, Nº 01, pp. 159-194.

- ROSE-ACKERMAN, Susan (1999), Corruption and government: causes, consequences and reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 266 pp..

- SADEK, Maria Tereza and CASTILHO, Ela V. (1998), O Ministério Público Federal e a Administração da Justiça no Brasil São Paulo: Editora Sumaré, Banespa. 40 pp..

- SADEK, Maria Tereza and CAVALCANTI, Rosângela (2003), The new Brazilian public prosecution: an agent of accountability. In: Democratic accountability in Latin America Edited by MAINWARING, Scott and WELNA, Christopher. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 201-227.

- SANTISO, Carlos (2007), Auditing for accountability? Political economy of government auditing and budget oversight in emerging economies. Doctoral thesis Postgraduate Program in Philosophy. The Johns Hopkins University.

- SANTOS, Romualdo Anselmo dos (2009), Institucionalizing anti-corruption: a Brazilian case of institutional origin and change. Paper presented at World Congress of Political Science, Santiago, Chile.

- SCHEDLER, Andreas; DIAMOND, Larry and PLATTNER, Marc F. (eds) (1999), The self-restraining state: power and accountability in new democracies. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers. 398 pp..

- SIAVELIS, Peter M. (2000), The president and Congress in post-authoritarian Chile: institutional constraints to democratic consolidation University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. 245 pp..

- SPECK, Bruno (2011), Auditing institutions. In: Corruption and democracy in Brazil. Edited by POWER, Timothy and TAYLOR, Matthew. University of Notre Dame Press. p. 127-161.

- SPECK, Bruno Wilhelm (ed) (2002), Caminhos da transparência: análise dos componentes de um sistema nacional de integridade. Campinas: Editora Unicamp. 224 pp..

- SPECK, Bruno Wilhelm (1999), The Federal Court of audit in Brazil. Paper presented in 9th International Anti-Corruption Conference, Durban, South Africa.