Abstract

The similarity of Jair Bolsonaro’s and Donald Trump’s divisive views on a variety of controversial issues has led many critics to argue that Brazilians elected a ‘Tropical Trump’ in 2018. Research on Trump’s election shows that authoritarian, racist, and sexist voters were essential to his narrow victory; however, it is an open question whether Trump’s pathway to power is the norm or the exception among right-wing nationalists. Even though candidates espousing controversial ideas about democracy and prejudice are gaining much electoral support, we know little about the extent to which their voters hold similar views. This study confirms that many Brazilians share Bolsonaro’s ambivalence about democracy as well as his attitudes denigrating women and sexual minorities; however, the degree of congruence between his supporters’ and his own views on these topics played a minor role at most in shaping voter choice. As in previous elections, ideology and partisanship – specifically, attitudes about Brazil’s Workers’ Party – largely explain whether a voter supported him. This finding largely holds across gender and racial boundaries, although white Brazilians appear to have been modestly more inclined than Afro-Brazilians to vote for Bolsonaro if they shared his divisive views.

Brazilian elections; Brazilian voting behavior; right-wing nationalism; 2018 Brazilian presidential election; Jair Bolsonaro

In 2018, Jair Bolsonaro outpolled all competitors in Brazil’s first round of presidential voting. The long-term congressman also easily defeated his run-off opponent, the candidate of the Workers’ Party (hereinafter ‘the PT’), which had won Brazil’s four previous presidential contests. As Donald Trump had done two years earlier in the U.S., when he overcame the incumbent party’s decidedly less-controversial nominee, Bolsonaro packaged himself as a brash, nationalist political outsider. While there are many differences between Bolsonaro and Trump, the global press and many academics have stressed the men’s similarities, including the overlap in their populist rhetoric, executive leadership styles, and use of social media to micro-target voters. Nevertheless, it is primarily their shared notoriety for misogynistic, racist, homophobic, and militaristic statements and policy positions that has led many critics to argue that Brazilians have elected a ‘Tropical Trump’ ( BBC, 2018BBC (2018), Jair Bolsonaro: Brazil’s firebrand leader dubbed the Trump of the Tropics. Available at < https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-45746013 >. Accessed on February, 01, 2019.

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-ame...

; DOCTOR, 2019DOCTOR, Mahrukh (2019), Bolsonaro and the prospects for reform in Brazil. Political Insight . Vol. 10, N° 02, pp. 22–25. ; THE GUARDIAN, 2018THE GUARDIAN (2018), Who is Jair Bolsonaro? Brazil’s far-right president in his own words. Available at < https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/sep/06/jair-bolsonaro-brazil-tropical-trump-who-hankers-for-days-of-dictatorship >. Accessed on February, 01, 2019.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/s...

; WEIZENMANN, 2019WEIZENMANN, Pedro Paulo (2019), Tropical Trump’?: Bolsonaro’s threat to Brazilian democracy. Harvard International Review . Vol. 40, N° 01, pp. 12-14. ).

Bolsonaro’s viewpoints on democracy, women, and sexual and racial minorities are controversial and abhorrent to many Brazilians. During his time as a military officer, decades in Congress, and as a presidential candidate, he frequently and enthusiastically defended Brazil’s 1964 military coup and subsequent dictatorship, praising by name military officials who had tortured regime opponents. He continues to argue that democracies sometimes face crises that justify military intervention ( KER, 2019KER, João (2019), Outras vezes em que a família Bolsonaro criticou democracia. O Terra. Available at ˂ https://www.terra.com.br/noticias/outras-vezes-em-que-afamila-bolsonaro-criticou-democracia,3fea8fb3eb2d8e5598aced0efb8cc049wdxyilqh.html ˃. Accessed on February, 01, 2020.

https://www.terra.com.br/noticias/outras...

; ÉPOCA, 2011ÉPOCA (2011), Jair Bolsaro: Sou preconceituoso, com muito orgulho. Available at < http://revistaepoca.globo.com/Revista/Epoca/0,,EMI245890-15223,00.html >. Accessed on February, 01, 2019.

http://revistaepoca.globo.com/Revista/Ep...

). His history of sexism and homophobia, too, was well known to Brazilian voters when they headed to the polls in 2018. On one occasion, while he was a federal congressman, Bolsonaro stated that congresswoman Maria do Rosário deserved to be sexually assaulted for her viewpoints, but that she ‘didn’t merit it’. A critic of sexual minority rights, he has said he would prefer his son to be dead rather than gay and has urged parents to beat effeminate boys ( ÉPOCA, 2011ÉPOCA (2011), Jair Bolsaro: Sou preconceituoso, com muito orgulho. Available at < http://revistaepoca.globo.com/Revista/Epoca/0,,EMI245890-15223,00.html >. Accessed on February, 01, 2019.

http://revistaepoca.globo.com/Revista/Ep...

). Trump’s victory prompted women’s marches across the U.S., but Bolsonaro’s record of denigrating women, non-white Brazilians, and sexual minorities provoked a national movement against him – #EleNão (#NotHim) – even before he was elected president.

Do voters supporting right-wing nationalists share their most controversial views?

It is not yet clear whether Bolsonaro’s most divisive views helped or hurt him vis-à-vis the Brazilian electorate as a whole. In the U.S., political scientists have examined closely the central role that Trump’s appeals to authoritarianism and prejudice played in his winning electoral coalition. Trump entered the general election with the support of the demographic and religious groups that typically back Republican nominees, but it was authoritarian, racist, and sexist voters who tipped a very close election in his favor (e.g., MAcWILLIAMS, 2016MAcWILLIAMS, Matthew C. (2016), Who decides when the party doesn’t? Authoritarian voters and the rise of Donald Trump. Political Science and Politics . Vol. 49, Nº 04, pp. 716–721. ; SCHAFFNER, MAcWILLIAMS, and NTETA, 2018; SETZLER and YANUS, 2018SETZLER, Mark and YANUS, Alixandra B. (2018), Why did women vote for Trump? American Political Science Association . Vol. 51, Nº 03, pp. 523–527. ; VALENTINO, WAYNE, and OCENO, 2018). In his Republican party primary contests, after controlling for other factors, highly authoritarian voters were five times as likely as non-authoritarian voters to back him, and experts have demonstrated that authoritarian voters were essential to Trump’s nomination ( MAcWILLIAMS, 2016MAcWILLIAMS, Matthew C. (2016), Who decides when the party doesn’t? Authoritarian voters and the rise of Donald Trump. Political Science and Politics . Vol. 49, Nº 04, pp. 716–721. ). Racist and sexist voters were even more important than authoritarians in the general election. Controlling for other factors, including partisanship, possessing the levels of sexism and racism typical of a Trump supporter increased the probability of voting for him by over 50 percentage points when compared to individuals with the sexism and racism scores typical of non-Trump voters (i.e., 69% versus 17%) ( SETZLER and YANUS, 2018SETZLER, Mark and YANUS, Alixandra B. (2018), Why did women vote for Trump? American Political Science Association . Vol. 51, Nº 03, pp. 523–527. ; see also: SCHAFFNER, MAcWILLIAMS, and NTETA, 2018)1 1 In SETZLER and YANUS (2018) , similar probabilities were calculated for a female-only sample when all other variables were fixed at their average marginal effects. Here, the whole sample is analyzed with all other variables set at their means. .

Since Trump took office, several unconventional, right-wing candidates for their nations’ highest offices, including Bolsonaro, have been compared to Trump due to their ambivalence toward democracy and appeals to voters’ outgroup prejudices and nationalism (ROODUIJN, BRUG, and LANGE, 2016). The most recent elections for the leaders of Brazil, India, Italy, and the U.S. — the largest democracies where trust in government and social institutions have fallen the most — have all featured right-wing nationalists running Trump-like, personality-centered campaigns disparaging social and political minorities while promising national economic and political renewal ( FRIEDMAN, 2018FRIEDMAN, Uri (2018), Trust is collapsing in America. Available at < https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/01/trust-trump-america-world/550964/ >. Accessed on February, 01, 2019.

https://www.theatlantic.com/internationa...

; NORRIS and INGLEHART, 2019NORRIS, Pippa and INGLEHART, Ronald (2019), Cultural backlash: Trump, Brexit, and authoritarian populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 564 pp.. ).

For all of the success right-wing nationalists are having at the polls, we still know very little about the extent to which their voters share their controversial views. There is some research showing that back when left-leaning governments were more numerous in Latin American in the 2010s, highly authoritarian voters tended to vote for right-wing authoritarian candidates ( COHEN and SMITH, 2016COHEN, Mollie J. and SMITH, Amy Erica (2016), Do authoritarians vote for authoritarians? Evidence from Latin America. Research & Politics . Vol. 03, Nº 04, pp. 01–08. ). On the other hand, while authoritarianism and prejudice have mobilized voter support for Trump in the U.S., perhaps citizens elsewhere support these politicians primarily because of ideological congruity, partisanship, or in the hope that their economic concerns will be better addressed by the candidates who seem most likely to up-end the status quo.

Data and measurement

Does voter affinity to Bolsonaro’s controversial views on authoritarianism, militarism, sexism, and homophobia explain his victory, or was voter choice driven by the same issues that typically shape vote choice in Brazilian presidential elections, namely economic concerns, political ideology, and partisanship? The data to answer this question come from the 2018–2019 round of the AmericasBarometer survey for Brazil. The nationally-representative sample included 1,498 face-to-face interviews, most of which took place in February 2019. The survey asked only about vote choice in the first round of presidential elections, but this is the optimal context in which to examine the influence of Bolsonaro’s divisive appeals because supporting him in the first round demonstrates a vote for him specifically rather than against the alternative, as may have been the case with some of the support Bolsonaro received in the run-off election.

The analyses below are restricted to the subset of individuals who voted. While voting is legally mandatory in Brazil, 23% of respondents said that they had refrained from casting a vote, which is consistent with the officially reported abstention rate. Another 10% either did not know or did not want to say for whom they had voted. Of the 1,006 respondents who either cast a ballot for a candidate or chose to cast a null or blank vote, 54% recalled voting for Bolsonaro (56% if null and blank votes are excluded). This is about 8% higher than Bolsonaro’s actual vote share in the official results but consistent with research showing a small minority of voters misremembers their vote choice, usually erring by saying they selected the winner (DURAND, DESLAURIERS, and VALOIS, 2015)2 2 Because of its high-quality, face-to-face administration, AmericasBarometer surveys frequently are used to analyze voters' attitudes and vote choice, and the survey has been used previously to examine the extent to which right-wing populists in Latin America are disproportionately supported by authoritarian voters ( COHEN and SMITH, 2016 ). As noted by one of the anonymous reviewers, ideally the survey would have been administered as close to the election as possible, with vote-choice data being collected immediately afterward. Had this been the case, there would be less chance that some respondents who voted for/against Bolsonaro may have shifted their views after the election to better match/oppose his opinions. However, it is unlikely that this was a widespread issue. Bolsonaro had been in office only around a month when most of the AmericasBarometer survey interviews were conducted, and his most controversial views were so well known in advance of the election that they had sparked the national #EleNão movement. Moreover, my results suggest that the correlation between voting for/against Bolsonaro and sharing/rejecting his controversial views is weak at best. .

The 2018 AmericasBarometer survey fielded items that gauge individuals’ attitudes toward democracy, prejudice against women, and sexual minorities. The survey regularly asks respondents about their support for democracy, but, in this wave, only one of these items was administered to the entire Brazilian sample. It asked how much respondents disagreed/agreed that ‘democracy may have problems, but it is better than any other form of government’. The item was recoded into four levels that distinguish respondents who disagree that democracy is best (i.e., were in the top bottom of the scale before recoding) from those who agree to varying degrees that it is the best system. To explore individuals’ openness to military intervention in society, I combined two items that asked respondents whether a military coup would (or would not) be justified in a period of high crime (half the sample) or corruption (the other half). The survey also includes a standard measure of sexism, asking respondents how much they disagree/agree that ‘men, generally speaking, make better political leaders than women’. Respondents were coded into three levels of sexism, depending on whether they strongly disagreed, disagreed, or agreed with the statement. And finally, the measure of homophobia is a question asking respondents how much they approve/disapprove (self-placement on a 10-point scale) with the liberty of ‘homosexuals’ to run for public office. These variables were all rescaled to range from zero to one and reverse coded if necessary so that the highest values corresponded with the attitude most consistent with Bolsonaro’s views.

The AmericasBarometer also fields the items necessary to test the alternative hypothesis that his supporters were primarily motivated by economic concerns, ideological affinity, or partisanship. The chaotic and scandal-ridden economic and political environment Brazilians experienced under the left-leaning and then post-impeachment governments that preceded Bolsonaro’s candidacy presumably is part of the explanation for why so many voters chose an unconventional candidate with no links to the major political parties ( CHAGAS-BASTOS, 2019CHAGAS-BASTOS, Fabrício H. (2019), Political realignment in Brazil: Jair Bolsonaro and the right turn. Revista de Estudios Sociales . Vol. 69, pp. 92–100. ; HUNTER and POWER, 2019HUNTER, Wendy and POWER, Timothy J. (2019), Bolsonaro and Brazil’s illiberal backlash. Journal of Democracy . Vol. 30, Nº 01, pp. 68–82. ; SANTOS and TANSCHEIT, 2019SANTOS, Fabiano and TANSCHEIT, Talita (2019), Cuando viejos actores se marchan: la ascensión de la nueva derecha política en Brasil. Colombia Internacional . Vol. 99, pp. 151–86. ). Clearly, ideology and partisanship are relevant, too. Beyond the political crises and economic difficulties voters experienced in the months preceding the election, scholars have emphasized the extent to which the Brazilian electorate already had shifted to the right well before Bolsonaro’s emergence onto the national scene, a realignment in which "the far right [had] achieved ideological hegemony and a solid electoral majority, despite the lack of stable leadership, strong movements and solid parties" ( SAAD-FILHO and BOFFO, 2019SAAD-FILHO, Alfredo and BOFFO, Marco (2019), The corruption of democracy: corruption scandals, class alliances, and political authoritarianism in Brazil. Geoforum. Available at < https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.02.003 >. Accessed on May, 17, 2019.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020....

; see also GOLDSTEIN, 2019)GOLDSTEIN, Ariel Alejandro (2019), The new far-right in Brazil and the construction of a right-wing order. Latin American Perspectives . Vol. 46, Nº 04, pp. 245–262. . However, as Samuels and Zucco (2018)SAMUELS, David J. and ZUCCO, Cesar Jr. (2018), Partisans, antipartisans, and nonpartisans: voting behavior in Brazil. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 196 pp.. stress, for many Brazilians, self-placement on the left-right divide does not represent firm attachment to an ideologically consistent set of core issue beliefs on the part of voters and instead reflects an inherently partisan schism between partisans who overwhelmingly socially identify with the PT and anti-partisans whose political identity is centered on opposing the PT ( SAMUELS and ZUCCO, 2018)SAMUELS, David J. and ZUCCO, Cesar Jr. (2018), Partisans, antipartisans, and nonpartisans: voting behavior in Brazil. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 196 pp.. .

Were economic concerns, voter ideology, and political identities more relevant to Brazilians’ preferences than Bolsonaro’s controversial views? His campaign certainly acted like they were. Like Trump, Bolsonaro campaigned on economic and political reform, evangelical religious principles, anti-partisan attacks on the incumbent party and its base (known in Portuguese as petistas), as well as a variety of conservative policies and values. To test the idea that standard issues — rather than appeals to authoritarianism or prejudice — drove vote choice, the analyses include measurements of each respondent’s assessment of the national economy (‘better’, ‘the same’, or ‘worse’), a 10-point indicator of self-placement on a left-to-right ideological scale, and a 10-point indicator measuring ‘antipetismo’, where respondents placed themselves on a scale ranging from ‘very much like’ the PT to ‘do not like it at all’. Each of these indicators also was rescaled to range from zero-to-one, with the higher values expected to increase the probability of voting for Bolsonaro.

Finally, the analyses include several dichotomous controls. Polling from the week before the election indicated that men, whites, residents of Brazil’s most developed regions, individuals living in households with incomes of at least two monthly minimum wages (i.e., at least USD 500.00 a month), and perhaps older Brazilians would be more likely to vote for Bolsonaro ( G1 GLOBO, 2018G1 GLOBO (2018), Pesquisa Ibope de 03 de outubro para presidente por sexo, idade, escolaridade, renda, região, religião e raça. Available at < https://g1.globo.com/politica/eleicoes/2018/eleicao-em-numeros/noticia/ 2018/10/04/pesquisa-ibope-de-3-de-outubro-para-presidente-por-sexo-idade-escolaridade-renda-regiao-religiao-e-raca.ghtml >. Accessed on February, 01, 2019.

https://g1.globo.com/politica/eleicoes/2...

). For race, the reference category in the regression models and figures is Afro-Brazilians; a multi-group ‘other race’ indicator was included in those models to isolate the differences between Afro-Brazilians and whites. The campaign specifically targeted Brazilian evangelicals, so the analyses also include a dummy variable distinguishing these respondents.

Figure 01 compares the characteristics of Bolsonaro’s supporters and other voters. For each of the dichotomous independent variables, the bars plot the share of each group’s voters possessing the identified characteristic. For example, 58 percent of Bolsonaro voters were male, while only 44 percent of his non-supporters were. For the five continuous variables, the figure compares the means for Bolsonaro and non-Bolsonaro voters. In the absence of any controls, the data show that his voters were disproportionately homophobic and open to coups in difficult times; however, the most striking difference is how strongly ‘antipestista’ his voting block was3 3 These descriptive statistics and all of the other analyses were calculated with Stata 15, using SVY settings that take into account the survey’s complex design, stratification, and sampling weights ( LAPOP, 2019) . .

The characteristics of Bolsonaro supporters and non-supporters

Notes: For each dichotomous variable, the bars plot the share of Bolsonaro supporters and non-supporters who possess the specified characteristic. For the five continuous variables, which all range from zero to one, the bars compare the mean score for Bolsonaro supporters and non-supporters. The lines on the bars denote 95% confidence intervals. The calculations take into account the survey’s complex survey design and weights.

Findings

Why did Brazilians vote for the ‘Tropical Trump’? The plotted proportions in Figure 02 compare the share of Bolsonaro voters at each independent variable’s lowest and highest value. The control variables, ‘standard’ issues like perceptions of the economy, voter ideology, and partisanship, and alignment with Bolsonaro’s controversial views all appear related to his support. Notably, in the absence of controls that separately measure the influence of each variable, the most sexist of Brazilians were statistically no more likely to vote for Bolsonaro than the least sexist. This also is the case among voters who fully diverged over the question of whether democracy is the best form of government.

The proportion of respondents who voted for Bolsonaro, by demographic and attitudinal diferences

Notes: The bars show the proportions of different types of voters who cast their ballot for Bolsonaro. The lines on the bars denote 95% confidence intervals. The calculations take into account the survey’s complex survey design and weights.

Isolating the effect of each factor to better understand its influence on vote choice requires multivariate analysis. The first logistic regression model summarized in Table 01 predicts the likelihood of voting for Bolsonaro as each independent variable is increased across its full range (i.e., going from zero to one), holding the influence of all other variables constant at their means. The other models are restricted to sub-samples varying by gender and race. Polling directly ahead of Brazil’s elections and the breadth of the ‘#EleNão’ movement raise the question of whether men and white Brazilians might have been disproportionately susceptible to Bolsonaro’s most divisive appeals, and the subsample models allow us to see if this was the case.

In the full model, neither sexism nor homophobia is a significant predictor of vote choice, but attitudes toward democracy and openness to coups are. Nevertheless, the most powerful predictor of voting for Bolsonaro was hostility toward the PT, closely followed by being more conservative or evangelical. Consider the hypothetical case of two individuals who are alike in every way, except that one of them has the sexism, homophobia, militarism, and support for democracy scores typical of a Bolsonaro voter while the other individual has the average score for non-supporters on each measure. The full model estimates that the probability that each of these voters voted for Bolsonaro differs by just three percentage points (56% versus 53%). In contrast, consider the effect of diverging partisanship on two hypothetical individuals who differ only in their level of ‘antipetismo’ , with the first voter having the level typical of a Bolsonaro supporter and the other the average ‘antipetismo’ score of his non-supporters. The full model estimates that the first voter would be 21 percentage points more likely to have voted for Bolsonaro (64% versus 43%). In short, partisanship and ideology were much more powerful determinants of vote choice than sharing Bolsonaro’s controversial views.

Do these findings hold up if we look at groups that were especially supportive or not of Bolsonaro? Since unstandardized logistic regression coefficients are difficult to interpret without mathematical transformation and additional context, I computed marginal effects for the last four models in Table 01 . In Figure 03 , each set of bars plots the change in the probability of a woman, and then a man, voting for Bolsonaro if you compare a typical respondent with the lowest value of the identified independent variable to an otherwise identical peer with the highest value. While there are some differences in the results for men and women, they are very modest for the most part. Being a female white voter, however, increased the probability of voting for Bolsonaro by about 15 percentage points while not affecting men. Women perhaps were disproportionately motivated by political ideology and men by hostility toward the PT, but the gender differences are not statistically different. The findings here replicate a key finding from the research on Trump’s election, showing that male and female voters do not vary from one another in how controversial attitudes shape their level of support for sexist, right-wing candidates ( SETZLER and YANUS, 2018SETZLER, Mark and YANUS, Alixandra B. (2018), Why did women vote for Trump? American Political Science Association . Vol. 51, Nº 03, pp. 523–527. ).

Change in the probability of having voted for Bolsonaro with predictors at their maximum and minimum values, by voter gender

Notes: The bars are plotted marginal effects estimates calculated with the logistic regression models summarized in Table 01; they show how much going from the lowest to the highest value of each independent variable changes the probability that a person voted for Bolsonaro. The lines on the bars denote 90% confidence intervals. The estimates take into account the survey’s complex survey design and weights.

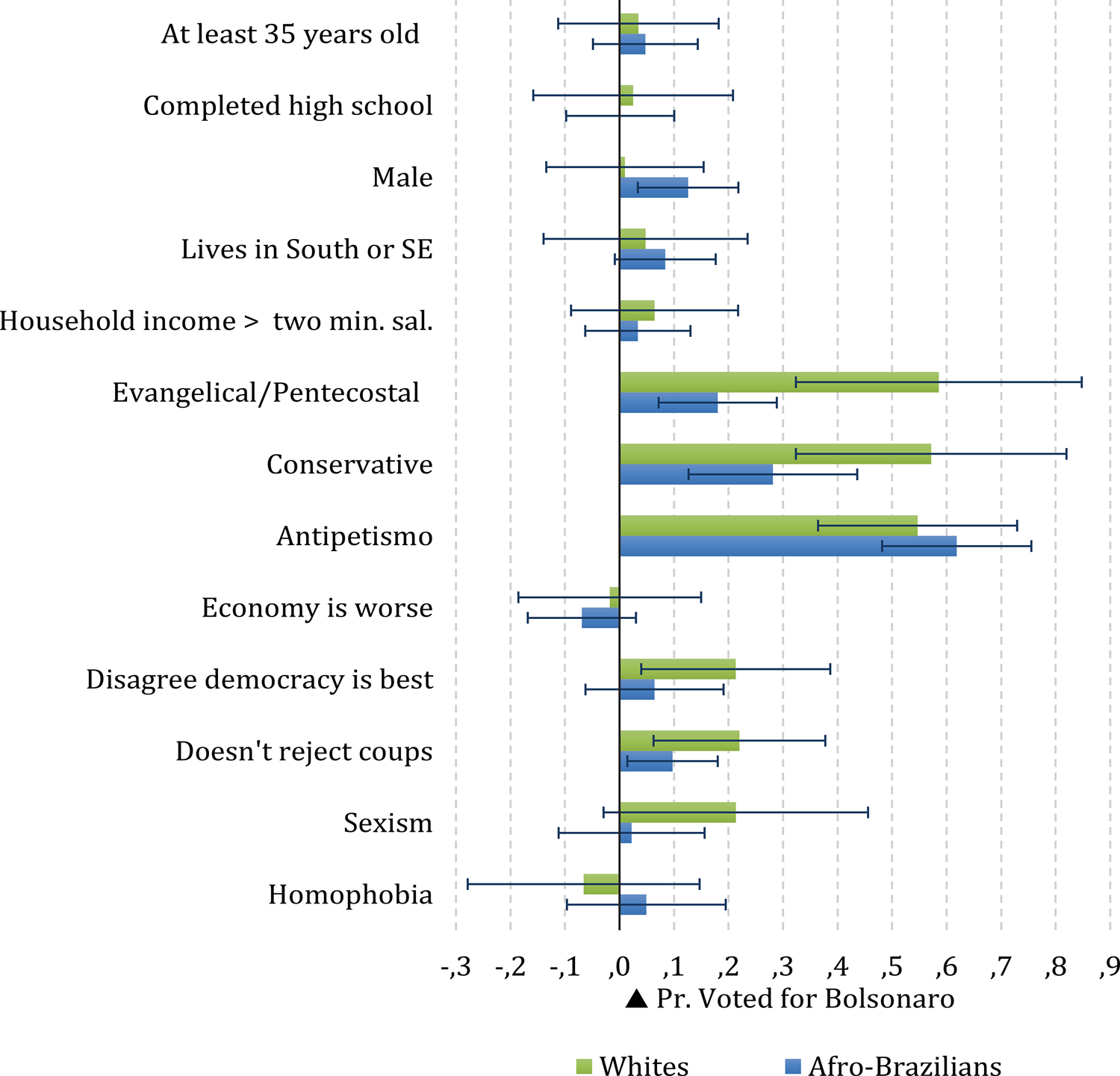

Figure 04 plots marginal effects by respondent race. Its axes are the same as Figure 03 , permitting straightforward comparisons of the four subgroups. The relationship between voters’ controversial attitudes and support for Bolsonaro varies more by race than gender. In particular, rejecting democracy as the best form of government and saying that a military coup can be justified when society is experiencing duress made whites more likely to vote for Bolsonaro, while these attitudes had a modest effect at best on Afro-Brazilians. The relatively small sample size for Whites (n=278) presumably led to the statistically insignificant result for the sexism indicator, but the overall pattern suggests that whites were modestly more likely to vote for Bolsonaro if they shared his controversial views. Similarly, while the popular press stressed the role that evangelical Pentecostals played in Bolsonaro’s victory, that source of support, too, was largely restricted to white adherents.

Change in the probability of having voted for Bolsonaro with predictors at their maximum and minimum values, by voter race

Notes: The bars are plotted marginal effects estimates calculated with the logistic regression models summarized in Table 01; they show how much going from the lowest to the highest value of each independent variable changes the probability that a person voted for Bolsonaro. The lines on the bars denote 90% confidence intervals. The estimates take into account the survey’s complex survey design and weights.

Conclusion

Given the social turmoil Brazilians endured ahead of the 2018 elections, it is not surprising that many opted for the most atypical candidate capable of winning. Nevertheless, the main factors that led voters to support Bolsonaro appear to be the same ideological and partisan affinities — especially, antiparty hostility toward the PT — that have driven voter choice in other recent Brazilian elections. While many Brazilian voters shared Bolsonaro’s ambivalence about democracy and attitudes denigrating women and sexual minorities, these views played a relatively minor role in predicting vote choice when compared to the influence of ideology and especially partisanship. Collectively, the findings indicate that critics need to be more reticent and precise when writing about the ‘Trump effect’ or ‘Trump-like’ political candidates and movements operating outside of the United States. Even in settings where a substantial portion of the electorate shares a right-wing nationalist candidate’s controversial views, we should not automatically assume that such views dictate vote choice or explain why these politicians sometimes win.

References

- BBC (2018), Jair Bolsonaro: Brazil’s firebrand leader dubbed the Trump of the Tropics. Available at < https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-45746013 >. Accessed on February, 01, 2019.

» https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-45746013 - CHAGAS-BASTOS, Fabrício H. (2019), Political realignment in Brazil: Jair Bolsonaro and the right turn. Revista de Estudios Sociales . Vol. 69, pp. 92–100.

- COHEN, Mollie J. and SMITH, Amy Erica (2016), Do authoritarians vote for authoritarians? Evidence from Latin America. Research & Politics . Vol. 03, Nº 04, pp. 01–08.

- DOCTOR, Mahrukh (2019), Bolsonaro and the prospects for reform in Brazil. Political Insight . Vol. 10, N° 02, pp. 22–25.

- DURAND, Claire; DESLAURIERS, Mélanie, and VALOIS, Isabelle (2015), Should recall of previous votes be used to adjust estimates of voting intention? Survey Insights. Available at < https://surveyinsights.org/?p=3543 >. Accessed on February, 01, 2019.

» https://surveyinsights.org/?p=3543 - ÉPOCA (2011), Jair Bolsaro: Sou preconceituoso, com muito orgulho. Available at < http://revistaepoca.globo.com/Revista/Epoca/0,,EMI245890-15223,00.html >. Accessed on February, 01, 2019.

» http://revistaepoca.globo.com/Revista/Epoca/0,,EMI245890-15223,00.html - FRIEDMAN, Uri (2018), Trust is collapsing in America. Available at < https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/01/trust-trump-america-world/550964/ >. Accessed on February, 01, 2019.

» https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/01/trust-trump-america-world/550964/ - G1 GLOBO (2018), Pesquisa Ibope de 03 de outubro para presidente por sexo, idade, escolaridade, renda, região, religião e raça. Available at < https://g1.globo.com/politica/eleicoes/2018/eleicao-em-numeros/noticia/ 2018/10/04/pesquisa-ibope-de-3-de-outubro-para-presidente-por-sexo-idade-escolaridade-renda-regiao-religiao-e-raca.ghtml >. Accessed on February, 01, 2019.

» https://g1.globo.com/politica/eleicoes/2018/eleicao-em-numeros/noticia/ - GOLDSTEIN, Ariel Alejandro (2019), The new far-right in Brazil and the construction of a right-wing order. Latin American Perspectives . Vol. 46, Nº 04, pp. 245–262.

- HUNTER, Wendy and POWER, Timothy J. (2019), Bolsonaro and Brazil’s illiberal backlash. Journal of Democracy . Vol. 30, Nº 01, pp. 68–82.

- KER, João (2019), Outras vezes em que a família Bolsonaro criticou democracia. O Terra. Available at ˂ https://www.terra.com.br/noticias/outras-vezes-em-que-afamila-bolsonaro-criticou-democracia,3fea8fb3eb2d8e5598aced0efb8cc049wdxyilqh.html ˃. Accessed on February, 01, 2020.

» https://www.terra.com.br/noticias/outras-vezes-em-que-afamila-bolsonaro-criticou-democracia,3fea8fb3eb2d8e5598aced0efb8cc049wdxyilqh.html - LATIN AMERICAN PUBLIC OPINION PROJECT (LAPOP) (2019), AmericasBarometer 2018/19: Brazil, technical information. Available at < http://datasets.americasbarometer.org/database/files/Brazil_AmericasBarometer_2018-19_Technical_Report_W_101019.pdf >>. Accessed on January, 09, 2019.

» http://datasets.americasbarometer.org/database/files/Brazil_AmericasBarometer_2018-19_Technical_Report_W_101019.pdf - MAcWILLIAMS, Matthew C. (2016), Who decides when the party doesn’t? Authoritarian voters and the rise of Donald Trump. Political Science and Politics . Vol. 49, Nº 04, pp. 716–721.

- NORRIS, Pippa and INGLEHART, Ronald (2019), Cultural backlash: Trump, Brexit, and authoritarian populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 564 pp..

- ROODUIJN, Matthijs; BRUG, Wouter van der, and LANGE, Sarah L. de (2016), It’s not just Trump: voting for populists makes voters angrier and more discontented. Washington Post: The Monkey Cage . Available at < https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/05/12/its-not-just-trump-voting-for-populists-makes-voters-angrier-and-more-discontented/ >. Accessed on February, 01, 2019.

» https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/05/12/its-not-just-trump-voting-for-populists-makes-voters-angrier-and-more-discontented/ - SAAD-FILHO, Alfredo and BOFFO, Marco (2019), The corruption of democracy: corruption scandals, class alliances, and political authoritarianism in Brazil. Geoforum. Available at < https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.02.003 >. Accessed on May, 17, 2019.

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.02.003 - SAMUELS, David J. and ZUCCO, Cesar Jr. (2018), Partisans, antipartisans, and nonpartisans: voting behavior in Brazil. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 196 pp..

- SANTOS, Fabiano and TANSCHEIT, Talita (2019), Cuando viejos actores se marchan: la ascensión de la nueva derecha política en Brasil. Colombia Internacional . Vol. 99, pp. 151–86.

- SCHAFFNER, Brian F.; MAcWILLIAMS, Matthew C., and NTETA, Tatishe (2018), Understanding white polarization in the 2016 vote for president: the sobering role of racism and sexism. Political Science Quarterly . Vol. 133, Nº 01, pp. 09–34.

- SETZLER, Mark and YANUS, Alixandra B. (2018), Why did women vote for Trump? American Political Science Association . Vol. 51, Nº 03, pp. 523–527.

- THE GUARDIAN (2018), Who is Jair Bolsonaro? Brazil’s far-right president in his own words. Available at < https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/sep/06/jair-bolsonaro-brazil-tropical-trump-who-hankers-for-days-of-dictatorship >. Accessed on February, 01, 2019.

» https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/sep/06/jair-bolsonaro-brazil-tropical-trump-who-hankers-for-days-of-dictatorship - VALENTINO, Nicholas A.; WAYNE, Carly, and OCENO, Marzia (2018), Mobilizing sexism: the interaction of emotion and gender attitudes in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Public Opinion Quarterly . Vol. 82, Nº 01, pp. 799–821.

- WEIZENMANN, Pedro Paulo (2019), Tropical Trump’?: Bolsonaro’s threat to Brazilian democracy. Harvard International Review . Vol. 40, N° 01, pp. 12-14.

-

1

In SETZLER and YANUS (2018)SETZLER, Mark and YANUS, Alixandra B. (2018), Why did women vote for Trump? American Political Science Association . Vol. 51, Nº 03, pp. 523–527. , similar probabilities were calculated for a female-only sample when all other variables were fixed at their average marginal effects. Here, the whole sample is analyzed with all other variables set at their means.

-

2

Because of its high-quality, face-to-face administration, AmericasBarometer surveys frequently are used to analyze voters' attitudes and vote choice, and the survey has been used previously to examine the extent to which right-wing populists in Latin America are disproportionately supported by authoritarian voters ( COHEN and SMITH, 2016COHEN, Mollie J. and SMITH, Amy Erica (2016), Do authoritarians vote for authoritarians? Evidence from Latin America. Research & Politics . Vol. 03, Nº 04, pp. 01–08. ). As noted by one of the anonymous reviewers, ideally the survey would have been administered as close to the election as possible, with vote-choice data being collected immediately afterward. Had this been the case, there would be less chance that some respondents who voted for/against Bolsonaro may have shifted their views after the election to better match/oppose his opinions. However, it is unlikely that this was a widespread issue. Bolsonaro had been in office only around a month when most of the AmericasBarometer survey interviews were conducted, and his most controversial views were so well known in advance of the election that they had sparked the national #EleNão movement. Moreover, my results suggest that the correlation between voting for/against Bolsonaro and sharing/rejecting his controversial views is weak at best.

-

3

These descriptive statistics and all of the other analyses were calculated with Stata 15, using SVY settings that take into account the survey’s complex design, stratification, and sampling weights ( LAPOP, 2019)LATIN AMERICAN PUBLIC OPINION PROJECT (LAPOP) (2019), AmericasBarometer 2018/19: Brazil, technical information. Available at < http://datasets.americasbarometer.org/database/files/Brazil_AmericasBarometer_2018-19_Technical_Report_W_101019.pdf >>. Accessed on January, 09, 2019.

http://datasets.americasbarometer.org/da... . -

Revised by Fraser Robinson

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

19 Oct 2020 -

Date of issue

2021

History

-

Received

12 Feb 2020 -

Accepted

01 July 2020

Source: AmericasBarometer, Brazil 2018/19 wave (

Source: AmericasBarometer, Brazil 2018/19 wave (  Source: AmericasBarometer, Brazil 2018/19 wave (

Source: AmericasBarometer, Brazil 2018/19 wave (  Source: AmericasBarometer, Brazil 2018/19 wave (

Source: AmericasBarometer, Brazil 2018/19 wave (  Source: AmericasBarometer, Brazil 2018/19 wave (

Source: AmericasBarometer, Brazil 2018/19 wave (