Abstracts

Some early sixteenth-century works by artists from southern Germany (Albrecht Dürer, Hans Burgkmair, Albrecht Altdorfer, Jörg Breu) representing the 'people of Calicut' (which was then supposed to be accessible from Europe both in an eastward and westward direction) are explored in terms of their combination of images from South Asia and artifacts from Brazil. This is placed in the context of the methodologies developed during this period for collecting and processing data in the form of texts, images, and collections of material objects, which are considered to have been the antecedents of modern ethnography and anthropology.

Visual representation; History of Anthropology; Material culture

Algumas obras do início do século XVI, de artistas do sul da Alemanha (Albrecht Dürer, Hans Burgkmair, Albrecht Altdorfer, Jörg Breu), representando a 'gente de Calicute' (cidade que se supunha acessível a partir da Europa tanto na direção leste quanto oeste), são exploradas em termos de sua combinação de imagens do sul da Ásia e artefatos do Brasil. Isso é analisado no contexto das metodologias desenvolvidas nesse período para coletar e processar dados na forma de textos, imagens e coleções de objetos materiais, as quais são consideradas como sendo antecedentes da moderna etnografia e antropologia.

Representação visual; História da Antropologia; Cultura material

DOSSIER IMAGE, HISTORY AND SCIENCE

The people of Calicut: objects, texts, and images in the Age of Proto-Ethnography

A gente de Calicute: objetos, textos e imagens na Era da Proto-Etnografia

Christian Feest

Indianapolis Museum of Art. Indianapolis, Indiana, EUA

Autor para correspondênciaAutor para correspondência Christian Feest Fasanenweg 4a, D-63674, Altenstadt, Alemanha (christian.feest@t-online.de)

ABSTRACT

Some early sixteenth-century works by artists from southern Germany (Albrecht Dürer, Hans Burgkmair, Albrecht Altdorfer, Jörg Breu) representing the 'people of Calicut' (which was then supposed to be accessible from Europe both in an eastward and westward direction) are explored in terms of their combination of images from South Asia and artifacts from Brazil. This is placed in the context of the methodologies developed during this period for collecting and processing data in the form of texts, images, and collections of material objects, which are considered to have been the antecedents of modern ethnography and anthropology.

Keywords: Visual representation. History of Anthropology. Material culture

RESUMO

Algumas obras do início do século XVI, de artistas do sul da Alemanha (Albrecht Dürer, Hans Burgkmair, Albrecht Altdorfer, Jörg Breu), representando a 'gente de Calicute' (cidade que se supunha acessível a partir da Europa tanto na direção leste quanto oeste), são exploradas em termos de sua combinação de imagens do sul da Ásia e artefatos do Brasil. Isso é analisado no contexto das metodologias desenvolvidas nesse período para coletar e processar dados na forma de textos, imagens e coleções de objetos materiais, as quais são consideradas como sendo antecedentes da moderna etnografia e antropologia.

Palavras-chave: Representação visual. História da Antropologia. Cultura material

On Friday, 27 August 1520, the German artist Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) went to see the treasures sent a year before from Mexico by Hernán Cortés to the future emperor Charles V that were then exhibited at the royal palace in Brussels. His impressions of the "wondrous artificial things" from the "new golden land", recorded in his diary, have often and erroneously been quoted as an example for the spontaneous recognition of the aesthetics of foreign works of art (Feest, 1992, 1996), rather than as the futile attempt to express the amazement caused by their utter strangeness, technical incomprehensibility, and apparent monetary value. Like others who had seen these objects before him when they were displayed in Sevilla and Valladolid, Dürer found himself at a loss of words: "and the things that I have had there I do not know how to express" (Rupprich, 1956, p. 155).

This speechlessness not only illustrates the general difficulty of adequately representing material things in words, especially when compared to the possibilities of visual representation, it is also indicative of the problem of describing the hitherto unknown in the absence of appropriate categories and concepts. The need to do so was particularly felt during the early modern age, when due to a combination of economic, technological, and ideological circumstances Europeans suddenly found themselves engaged in an unprecedented encounter with the cultural diversity of humankind. The sixteenth century therefore saw the emergence of systematic approaches to record and to classify the range of observable phenomena both in terms of human universals (anthropology) and of cultural specifics (ethnography). While the neo-Latin term anthropologia was readily available, it took until around 1770 for the words 'ethnography' and 'ethnology' to be invented and thus to demarcate a domain of inquiry which by then had been taking shape for more than two centuries.

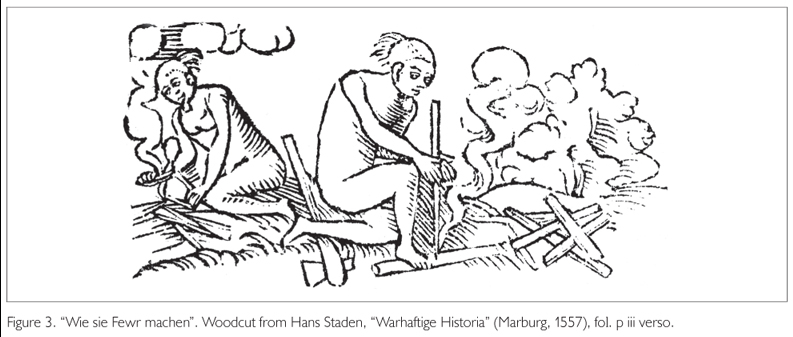

John Rowe (1965) has argued that it was the "perspective distance" resulting from the humanists' studies of classical antiquity that enabled the Renaissance to lay the (far from undisputed) foundations of modern anthropological thought. The methodology necessary for this endeavor, however, did not so much come from the rediscovery of the works of ancient writers, such as Herodotus or Tacitus, who had already dealt with cultural otherness, but from the Aristotelian distinction between (and combination of) historía and epistème (or historia and scientia in Latin terminology), the former concerned with recording empirical facts, the latter with the systematic delineation of knowledge. The apodemic treatises (related to the art of traveling) of the second half of the sixteenth century, which offered advice to travelers, suggested that at the end of each day the traveler should sit down to rearrange, in the manner of double-entry bookkeeping, the data found in his chronological record of observations under categorical headings, thus creating the distinction between the event-driven narrative and concept-driven generalization (or agency and structure). Traveling, which in the Middle Ages (as in the pilgrimage) had primarily served spiritual goals, was now transformed into a tool for a better understanding of the world and for the improvement of literary genres such as the travel narrative11 Hans Staden's "Warhaftige Historia und Beschreibung" (1557) is an early example for the dual approach, embracing his travel narrative in the first volume and the description of the Tupinamba and their country in the second. , the cosmography, or the "statistical" works describing the constitutive features of "polities" (Stagl, 1995, p. 35-39, 47-57).

Ethnographic and other categorical generalizations, useful and even necessary as they turned out to be for any comparative approach, have two inherent problems: in addition to the necessary decontextualization (and dehistorization) by removing the data from their observational context, they are only as good as the categories chosen for the purpose, which more often than not are inadequate for the description of cultural otherness and tend to assimilate the Other to or contrast it with the Self. This, however, is also true of narrative descriptions, which are equally based upon concepts existing prior to observation. The selectivity of what is recorded from a universe of possible observations is based upon a concept- or theory-driven notion of relevance that is also reflected in the articulation of the data (Feest, 2008, p. 19-24).

The same logic and the same historical circumstances apply to objects and images both as sources of ethnographic information and in their role in the representation of cultural otherness. The collection of objects and the production of images as well are based upon selective principles shaped by conceptual constraints and socially acceptable genres. In the case of images we find the same distinction as in texts between even-driven narrative representations and categorical generalizations by which singular observations are transformed into types. The most successful genre developed in the course of the sixteenth century for the visual representation of cultural diversity was the 'book of costumes', which exploited the ambiguity of the term 'habit' (meaning both 'costume' and 'custom') to use dress as the primary marker of difference (Defert, 1984; Doggett, 1992, p. 29-31, 48-51, 88-92). Conventions, such as the combination of front and back views of the same person, the joint depiction of men and women or of families provided the visual vocabulary for an easier reading of the images. Out of the universe of observable people, things, or activities, only a few were chosen as 'typical' and selected for representing otherness, some of them (such as men shooting with bows and arrows or fire-drilling) remaining in use for centuries (Feest and Luiza da Silva, 2011, p. 173-174, 190-191). The practice, widespread in early book publishing, of copying and adapting illustrations from previously published sources reinforced these types to the point of creating stereotypes, but the types existed independently of copying (Figures 1-4).

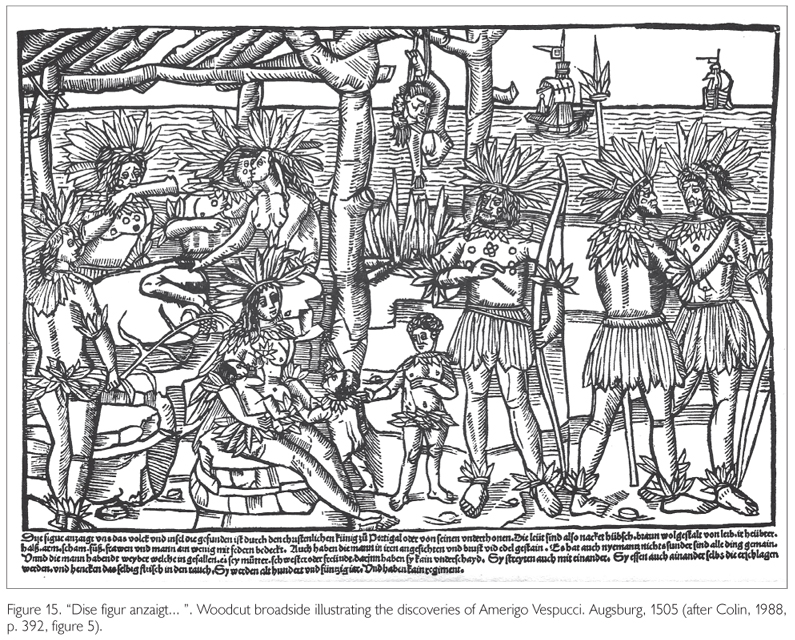

Despite their obvious shortcomings, the development and diversification of these 'visual concepts' was prerequisite for both descriptive and generalizing approaches to cultural diversity and for an incipient visual anthropology. At the same time it was a giant step forward from the assimilation of exotic otherness to medieval conventions, such as the 'Wild Men', which was as important for early depictions of the inhabitants of the 'New World' as the model of medieval travel narratives had been for the production of early modern texts (Colin, 1987; see also Barta, 1994).

While the production of texts and images had a long history prior to the technical and methodological innovations of the sixteenth century, the systematic collecting of artifacts presents a more radical break with the past. Other than the treasure houses of medieval times, where things were preserved for their economic or dynastic value, the Kunst- and Wunderkammern of the Renaissance, whose rise was contemporary with the rise of apodemic principles in writings and the 'books of costumes', were based on the attribution of value to the rarity of form of things, irrespective of whether rarity was based upon the ingenuity of their maker, their age, the remoteness of their origin, their virtues, or their monstrosity (MacGregor, 2007). As in the case of travel writing, where the first apodemic methodologies were published only in 1568-1569, the first published methodology of collecting, Samuel Quiccheberg's "Inscriptiones vel Tituli Theatri Amplissimi" (Roth, 2000), appeared in 1565, decades after the collecting of rarities had become a widespread and well established practice.

The often used designation of these collections as 'cabinets of curiosity' must be understood in the light of the definition of 'curiosity' as an activity that is associated with moving around and the use of the senses especially in new or unknown circumstances and that - while being superfluous to the functioning of the organism - is essential for innovative forms of knowledge production. As such, curiosity and its encouragement were central values of the Renaissance and a notable break with medieval moralist attitudes, which regarded curiositas as "a wandering, unstable state of mind" that should be discouraged (Stagl, 1995, p. 2-3, 48). The owners of such collections, which were generally accessible to the curious segment of the public, were either noblemen, for whom they also served as representation of a microcosm symbolic of their own claim to rule the world, or scholars, who used the same material to investigate and understand the world. The exotic objects in these collections (as in the case of the images), however, were not a representative sample of what existed in the real world, but a selection of 'types'.

It must be pointed out, however, that contrary to the principle on which the 'books of costumes' were based, collectors of exotic objects were only slowly taking an interest in the specific provenance of these artifacts. Well into the seventeenth century term such as 'Indian' (referring to both the East and West Indies), 'Moorish', 'African', or 'Heathen' (with 'Catholic' sometimes placed into the same category in Protestant countries) were sufficient to denote a physically or socially distant origin. Even more so than any image or text, these objects were alienated from their original social and cultural context, which had endowed them with meaning, use, and function, and were placed into the classificatory scheme responsible for their selection and for their new meaning, use, and function in a European social and cultural context (Appadurai, 1986).

In spite of this problem, the exotic artifacts that were part of the Kunst- and Wunderkammern are today regarded as precious ethnographic documents22 As far as Brazil is concerned, the otherwise useful compilation by Dorta (1992) deals only with ethnographic collections after 1650 and there by excludes the important earliest materials. For surveys of Brazilian objects prior to 1750, see Feest (1985, 1995, p. 328-329, 341-345). , also because probably only between one and ten percent of them have survived. This is especially true of the Mexican things seen by Dürer in 1520, some of which came to be part of this sister Margarete's collection in Mechelen, where many were given in subsequent years to visitors, while the rest was dispersed without adequate records or simply lost (Feest, 1990, p. 33-48).

Some commentators have wondered why Dürer, speechless as he was in front of these "wondrous things", had not made any drawings of what had impressed him so greatly. While no such drawings exist today, however, it cannot be excluded that they have once existed. There are indeed two drawings attributed to Hans Burgkmair (1473-1531) and dated to ca. 152033 Jean Michel Massing (in Levenson, 1991, p. 571) dates them to 1519-1525, but 1519 would mean that the Aztec items could only have been drawn in Spain, which is unlikely. , one of which (Figure 5) appears to show an Aztec turquoise shield now preserved in Vienna (Figure 6), as well as an Aztec wooden sword edged with obsidian flakes (maquahuitl), both of which could possibly have been seen by Dürer in Brussels (Feest, 2012a, p. 104-110).

The two weapons are carried by a man with African features who is wearing a feather headdress corresponding to the Brazilian type called "coroa radial" by Berta Ribeiro (1957, p. 78, figure 27), a necklace perhaps made of shell44 In 1528-1529 Christoph Weiditz shows a similar necklace, but made of feathers, as worn by one of the Aztecs and Tlaxcaltecs he was depicting (Hampe, 1927, pl. XXIII; see also figure 13 below). , a strange feather shoulder ornament, and a feather skirt remotely resembling a type designated as "tanga" by Ribeiro (1957, p. 95, figure 50)55 The type specimen for the 'tanga' illustrated by Ribeiro is an undocumented Bororo object in the Museu Nacional in Rio de Janeiro, but the 'tangas' (bóro) discussed in the most comprehensive treatment of Bororo (material) culture (Albisetti and Venturelli, 1962, p. 312-314) bear little resemblance with it. Nothing strictly comparable is found in Dorta and Cury (2001). . It is obvious that a drawing combining Mexican and Brazilian artifacts in association with an African model could hardly have been done after nature, and since Burgkmair apparently never had access to original Mexican artifacts, that it was very likely based on sketches made by different artists at different places and times. This helps to explain why some of the artifacts are probably not shown in the manner in which they were supposed to be used. The shoulder ornament may well be, as Colin (1988, p. 366) and Massing (in Levenson, 1991, p. 571) have suggested, a misplaced Tupinamba bonnet resembling the "coifa com cobre-nuca"-type (Ribeiro, 1957, p. 77, figure 2; Métraux, 1928, p. 130-136); the skirt, whose asymmetric placement over the right hip would be unusual for such a garment, could even be a Mexian feather headdress shown upside down66 The only surviving Mexican feather headdress, now in Vienna, was in the past occasionally identified as either a skirt or mantle and has frequently been illustrated upside down (Feest, 2012b, p. 7, 14-15, figures 3, 4, 18). . The only evidence for Aztec feather skirts or kilts comes from the drawings made in Spain by Christoph Weiditz in 1528-1529 (Hampe, 1927, pls. XV-XVII, XIX-XX, XXII-XXIII); such garments are not found in pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican representations (Anawalt, 1981).

The second drawing attributed to Burgkmair (Figure 7) shows another African man wearing the same feather ornaments and necklace (with minor differences as far as the headdress and necklace are concerned), but holds an 'anchor ax', a weapon usually regarded as typical for Gê-speaking peoples of the interior of Brazil (Rydén, 1937).

But not only would 1520 be a very early date for Gê artifacts to have reached Europe, there is also suggestive evidence that 'anchor axes' with a long and straight shaft were also used by some Tupinamba groups in the sixteenth century (Feest, 1985, p. 242, figure 91). The carving surmounting the blade is unusual but finds a parallel in an undocumented straight-shafted 'anchor ax' in the British Museum (Figure 8; McEwan, 2009, p. 58), which on the basis of its carving style has been attributed to the lower Amazon River and to the seventeenth or eighteenth century (Zerries, 1978, p. 285-286, pl. 384a).

The use of African models in the two drawings is easily explained by the lack of opportunity to draw Indians from life in Europe at a time when Africans were easily available as sitters for portraits and had already been drawn by Dürer, Burgkmair, and others. Although inhabitants of the newly-discovered lands across the Atlantic Ocean had been taken to Europe since the days of Columbus, they hardly could be seen and drawn outside of Spain (where there was notoriously little interest in the visual representation of exotic people), France (whence the Tupinamba Essomericq was taken in 1505), and perhaps Portugal. It took until 1528-1529 for the German artist Christoph Weiditz (1498-1559) to produce the first depictions after nature of inhabitants of the New World, when a group of Aztecs and Tlaxcaltecs was brought to Spain by Cortés (Hampe, 1927; Cline, 1969)77 Although the Weiditz drawings have received praise by anthropologists and historians for their accuracy (e.g., Sturtevant, 1976, or Massing in Levenson, 1991), some of their ethnographic details, such as the feather kilts noted above, seem out of place and may be another early example of what Sturtevant (1988) has called the 'Tupinambisation' of the North (and Middle) American Indians, i.e., the use of Tupinamba feather ornaments to stereotype other indigenous peoples of the New World. .

The earliest Portuguese images of Indians - the "Adoration of the Magi" of 1501-1506 attributed to Francisco Henriques (?-1518) and an anonymous scene of hell of 1510-1520 (Levenson, 2009, p. 190-191) - may serve as a reminder of the fact that not all the images (and texts) produced during the early modern age as a result of the European encounter with cultural diversity were intentionally 'ethnographic', even though we may be looking at them today as sources for a historical ethnography. Both pictures do not really show Indians, but an African and the devil, respectively, wearing and carrying Indian artifacts. American imagery is here used to signify the inclusion of the inhabitants of the islands in the west in their recognition of the Savior, or as the very embodiment of the Antichrist. An identification of the figure in the "Adoration" wearing a 'coroa radial' as the representation of an Itipi-Tupinamba (José Alberto Seabra Carvalho in Levenson, 2009, p. 191) is therefore misleading.

By contrast, the two drawings attributed to Burgkmair, while also not based on the observation of real-life persons, are by intention ethnographic in their attempt to create 'types' depicting cultural difference on the basis of weapons, clothing, and ornaments. The following argument intends to show that the people represented in these images were not American Indians but 'People of Calicut'.

Dürer's interest in the unusual is illustrated by the enthusiastic descriptions contained in the diary he kept on his trip to the Low Countries in 1520 not only of the Mexican treasures, but also of a big fish bone and the bones of the Antwerp giant, and by his acquisition of exotic animals and artifacts. In addition to parrots, Chinese porcelain, and an old Turkish whip, he acquired a "Calecutish wooden shield", "several feathers, Calecutish things", "2 Calecutish ivory salt cellars", "Calecutish cloths, one of them of silk", and a "small Calecutish target, made of a fishskin, and two gloves for their fighting" (Rupprich, 1956, p. 152, 156, 165, 166), some of them from his Portuguese friend Rodrigo Fernandez d'Almada.

While the shields and cloths were probably Asian and the salt cellars Afro-Portuguese, the feathers could have come from Brazil. The term 'Calecutish' applied to all of them is derived from the old designation 'Calicut' for the present Kozhikode in the Indian federal state of Kerala, the city in which Vasco da Gama had landed in 1498, thus opening the direct trade with India. Although Amerigo Vespucci had claimed that the lands found in the west were indeed a new world, rather than merely some islands in the vicinity of India, the matter was not finally settled until the circumnavigation of the globe undertaken by Fernão de Magalhães at the very moment when Dürer was in the Low Countries (Dos Santos Lopes, 1994).

European cosmographers were still divided on the relevance and meaning of Vespucci's claims. As recently as 1512 the humanist Johannes Cochlaeus (1479-1552), an acquaintance of Dürer, had stated that irrespective of whether the discovery of a New World was the truth or merely a lie, it had nothing to do with cosmography or historical knowledge: "For the people and places of these lands are as yet to us unknown and unnamed, thither there are also no navigations, except under many dangers: thus they are of no concern for the geographers" (Cochlaeus, 1512, fol. F verso-F ii recto). Others were better inclined than Cochlaeus to give more trust to the experiences of the modern travelers than to the authority of the classics, but the evidence was still inconclusive. Even after the map published in 1507 by Martin Waldseemüller, which shows an almost unbroken continental mass called 'America' stretching from Newfoundland to southern South America, other maps confined the 'Mundus Novus' to the southern hemisphere while connecting Newfoundland to Siberia and leaving a wide passage from the Spanish Indies to Japan and further to India, where some of the places named by Columbus on the Central American coast were placed (Levenson, 1991, p. 232-243).

Whether or not Dürer was Burgkmair's source for the Mexican objects depicted in one of his drawings, both men were part of a group of German artists who between 1513 and 1516 had included depictions of Brazilian objects in representations relating to 'Calicut'.

In 1512 Emperor Maximilian I dictated to his secretary the description of a triumphal procession in his own honor, which was to be executed as a series of woodcuts by prominent artists. At the very end of this train as Maximilian had imagined it, was to appear a group of 'Calicutish people':

Also after this there should be a man from Calicut on horseback carrying a signboard with a rhyme and wearing a laurel wreath... (One rank with shields and swords. One rank with spears. Two ranks with English bows and arrows. All are naked in the Indian manner or alla morescha). Behind this should be walking the Calicutish people. All of them should also be wearing the laurel wreath (Applebaum, 1964, p. 18-19).

Based on this text a series of now lost drawings was made by the Tyrolian artist Jörg Kölderer (ca. 1465-1540), which in turn served as a guideline for 109 miniature paintings executed between 1513 and 1515 in the workshop of Albrecht Altdorfer, with the 'Calicutish people' occupying folio 107 executed by Altdorfer himself: four rows of five men each, some of them bearded, dressed in non-specific feather garments (crowns, skirts, knee-bands) as well as sandals, and armed with round shields, swords (one of them ending in an oval disk), lances, bows (more resembling Turkish than English longbows), and a quiver that does not appear to be American. The leader's horse is likewise decorated with feather ornaments (Figure 9; Winzinger, 1972-1973, v. 1, p. 57, v. 2, p. 21, 57; Honour, 1975, p. 18-19; Sturtevant, 1976, p. 420-422; Colin, 1988, p. 333).

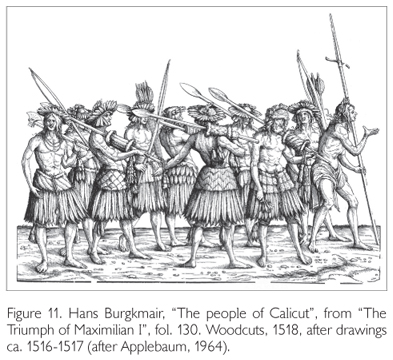

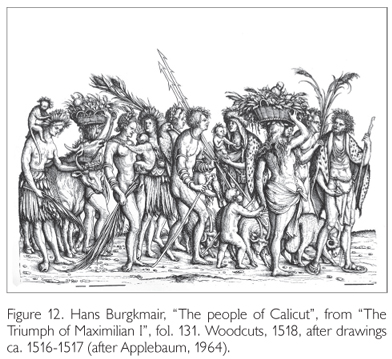

These miniatures provided the model for 139 woodcuts, about half of them based on now lost drawings made by Hans Burgkmair between 1516 and 1518, including the folios 129 to 131 showing the 'people of Calicut'. Folio 129, depicting the vanguard of the Calicutish division, follows the miniature painting in broad outline, but has the leader wearing a turban and sitting astride an elephant accompanied by a drummer, whereas the rank and file are wearing loincloths and laurel wreaths instead of feather garments and are partly armed with bows and arrows instead of the shields and swords. Two of the unusual (and unlikely) swords with oval ends are also shown; they as well as the loincloths and spear featured on folio 130 are clearly derived from a woodcut showing the 'King of Gutzin' (Cuchin, today: Kochi) living "[40] miles beyond Calicut", which Burgkmair had produced in 1508 as an illustration for a preprint of the report describing the voyage to India undertaken in 1505-1506 at the request of the Welsers, a prominent merchant-banker family from Augsburg, by the Tyrolian merchant Balthasar Springer (after 1450 to ca. 1509-1511) (Figure 10; Leitch, 2009).

It may be significant that in 1507 Maximilian I had made a payment to his Tyrolian court artist Jörg Kölderer for various services, including paintings on paper of "12 Calicutish manikins" (Winzinger, 1972-1973, v. 2, p. 19). It is likely that these were drawings done after sketches or verbal descriptions supplied by Springer, who had recently returned home from India. It may be assumed that Kölderer included at least elements of these images in the sketches on which Altdorfer's miniature 107 was based. Burgkmair, when working on the "King of Gutzin", may also have had access to these drawings or to the visual and verbal sources that had already been used by Kölderer. In the full publication of Springer's report in 1509, which included inferior illustrations by Wolf Traut based on Burgkmair's work, the dubious round-ended swords, for which no material evidence seems to exist, are described as being "partly pointed and partly having a round end" (Springer, 1509, fol. D ii verso). It thus may be assumed that in this case the drawings were based on the verbal description rather than on actual artifacts or drawings after nature.

Folios 130 and 131 of the "Triumph" (Figures 11 and 12) are additions to the sequence as designed by Altdorfer (or Kölderer) and are exclusively Burgkmair's work. The majority of the figures (except for two Brazilian women among them and the ears of corn they are carrying) populating folio 131 as well as the ethnographic details can be traced to the representations of Africans made by Burgkmair for Springer. But folio 130 prominently includes images of indubitably American artifacts, among them Brazilian radial feather crowns (some of them combined with feather bonnets), feather skirts and knee bands, and several Tupinamba wooden clubs. The feather skirts are quite different than the ones shown in the two later drawings attributed to Burgkmair (Figures 5 and 7), but are much more detailed than those used in previously printed illustrations (Figure 15) and show a range of variant decorations. No such skirts have survived as actual objects, but Burgkmair's representations of them are so convincing that we may assume they were based on specimens now lost. The same is true of the radial crowns, feather bonnets, and knee bands except that there is no independent evidence that radial crown and bonnet were worn together. Additional proof for Burgkmair's reliability is supplied by his depiction of the clubs, which have feather ornaments below the center of the shaft and terminate in oval blades. Although the majority of the eleven Tupinamba clubs today in existence have round, platter-shaped ends and many of them have lost their feather decoration, a club donated in 1652 by a man named Carl Mildner to the collection of the Elector of Saxony (Figure 13) provides proof that the shape drawn by Burgkmair actually existed (Meyer and Uhle, 1885, pl. 10, figure 6).

For the feather skirts and crowns there is, however, yet another visual document dating from 1515: a rather coarse woodcut illustration by Jörg Breu (ca. 1475-1537) for the German edition of the itinerary by Lodovico di Varthema (1515, fol. p recto) of his voyage to India and the adjacent islands (Figure 14; Colin, 1988, p. 191). This image, which is embedded into a passage of text dealing with Sumatra without being clearly related to it, displays a mixture of Oriental features (such as a turban) and Brazilian featherwork. While the skirts and crowns are very similar to the ones shown by Burgkmair (and only less detailed), the neck, arm, and leg ornaments were derived from the often reproduced Augsburg broadside of 1505 reporting on Vespucci's discoveries (Figure 15). Colin (1988, p. 186-187, figure 5) has called this image "one of the earliest representations of South American Indians with some ethnographic precision" (also Sturtevant, 1976, p. 420, figure 2; Levenson, 1991, p. 516), but it is clearly neither based upon direct observation by the artist, nor upon the study of actual artifacts and appears to rely exclusively on second-hand information.

Another derivative from the 1505 print is an anonymous and undated woodcut (Figure 16) discovered in Berlin (Osterwold and Pollig, 1987, p. 304), which is more detailed but not necessarily more precise in its representation of the featherwork. The bearded man appears to be wearing a feather cape (also shown in Breu's woodcut), and both the skirt and the headdress do not match what we think we know about Brazilian featherwork. The bow is much too small to be useful; the quiver resembles the one shown in Altdorfer's miniature painting and may even have provided Altdorfer with a model or have been based on the same source. Although the print bears no title, a Dutch watercolor copy made between 1577 and 1579 identifies the man shown as a "Nobleman of Calicut" (Egmond and Mason, 2000, p. 324, 344, figure 5). When the question is raised whether this figure "should be regarded as a representative of the East or West Indies" (Egmond and Mason, 2000, p. 325), the obvious answer is that Calicut was then thought to be a place which could be reached by sailing either to the east or to the west.

An especially striking and unusual feature of this anonymous woodcut is the long staff, completely covered with feathers, held by the man. There is no presently known iconographic model from which it could have been copied. But it bears a remote resemblance to the staff with a cylindrical ornament surmounted by three feathers at its upper end shown on the woodcut by Breu.

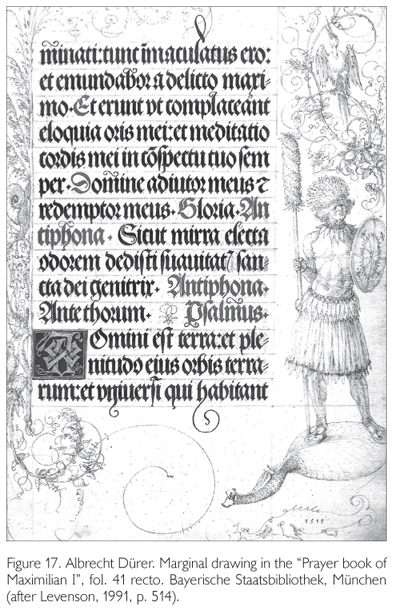

This staff takes us back to Dürer and the only known work in which he himself made use of American material. One of his marginal drawings in the "Prayer book of Maximilian I" (Figure 17), executed in 1515, shows a young man with European features dressed in feather clothing, standing on an upturned ladle, and holding in his left hand a round shield and his right hand a long staff whose cylindrical top is likewise made of feathers. Together with an Oriental man leading a camel on the following page, this figure illustrates the first verse of Psalm 34 ("The Earth is the Lord's, and its plenty, and all who inhabit it"), thus explicitly including the dwellers at the newly found (Calicuttan) margins of the Earth.

While the ladle is probably European and may symbolize the Earth and its plenty, the shield appears to be Asian (perhaps Turkish), although Sturtevant (1976, p. 423) and Massing (in Levenson, 1991, p. 516) believed its design could have reflected an Indian model. The shield's small size indicates that it must have been made for use by an equestrian soldier, which excludes its use by an indigenous American warrior. The sandals are also not of American origin and rather unspecific, although Sturtevant (1976, p. 423) points out their possible relationship to those shown in Altdorfer's miniatures of the "Triumph" (which in turn may be based upon Burgkmair's image of a Hottentot [Khoikhoi] couple for Springer) (Leitch, 2009, p. 150, figure 17).

The featherwork, however, is obviously based on the study of the same or similar originals also represented in the works of Burgkmair, Breu, and perhaps also Altdorfer. The feather skirt shows technical details not represented in other images, such as the use of a thread to connect the feathers near their distal end (Ribeiro, 1957, p. 64-65, figures 1 and 4). The feather bonnet is shown much more clearly than in Burgkmair's woodcuts and resembles the type illustrated in Joachim du Viert's engraving "Sauvages amenez en France pour estre instruits dans la Religion Catholique, qui furent baptisez a Paris en l'eglise de St. Paul le XVII juillet 1613" (Hamy, 1908, pl. 1) and fits Soares de Sousa's description: "usam também entre si umas carapuças de pennas amarellas e vermelhas, que põem na cabeça, que lh'a cobre até as orelhas" (quoted by Métraux, 1928, p. 130). The upper arm ornaments are barely visible, but follow the tradition of the 1505 broadside and Altdorfer's miniatures; the necklace is likewise reminiscent of the 1505 woodcut, but is shown in greater detail and is more convincing, despite the fact that no similar type of collar is shown by Ribeiro (1957, p. 90-91; but see Dorta and Cury, 2001, p. 49, 87, 137).

For the staff, which is often referred to as a scepter (although much too long for such as purpose), no comparative evidence is available88 The Munduruku feather scepters adduced for comparative purposes by Sturtevant (1976, p. 423, 447) measure only a third of the length and were made in a completely different technique.. But Dürer's representation is so meticulous that it permits the identification of the technique as the one also found on Tupinamba clubs and axes (Figures 11-13). Quite obviously it is the same artifact as seen on Breu's woodcut (Figure 14) and which, with a little goodwill, may also be recognized in the background of the "Christ with Crown of Thorns" on Altdorfer's "Sebastianaltar", which he painted between 1509 and 1515 (Winzinger, 1975, p. 78-80). Although not otherwise documented in the ethnographic record, it is something that actually existed, and not a misrepresentation of a Tupinamba club as suggested by Massing (in Levenson, 1991, p. 516).

The works of Dürer, Burgkmair, Altdorfer, and Breu from the period of ca. 1512 to 1515 reflect in an appropriate manner the notion then current of the 'People of Calicut' who could be reached from Europe both in an eastward and westward direction, and of their marginal position in the European worldview. The iconography of the 'People of Calicut' was fertilized by the access to objects from the east coast of Brazil, which at this point of time had obviously been brought from Portugal to southern Germany and to which the artist had direct and/or indirect access. The claim that these objects were connected to the Tupinambas taken to France in 1505 (Honour, 1975, p. 13) cannot be substantiated, whereas the trade relationships at that time between Augsburg and Nuremberg, respectively, and Portugal are well documented.

Konrad Peutinger (1465-1547), for example, the humanist cosmographer based in Augsburg and probably Burgkmair's major mentor as far geography and ethnography was concerned (Leitch, 2009), owned a collection, which according to an inventory included "18 pieces of Indian featherwork". Together with the majority of sixteenth-century featherwork these items did not survive and according to a later note in the inventory were already "all ruined" by the end of the century (Künast, 2001, p. 12; and H.-J. Künast, personal communication, 2013). Like Peutinger, Raymund Fugger (1489-1535) of Fugger trading house in Augsburg was in constant touch with Portuguese correspondents, and his collection may also have to have included Brazilian artifacts among his "other curiosities" which seemed less important that the more valuable antiquities, coins, and European works of art, and were therefore not described in detail (Busch, 1973, p. 85). Dürer's friend, the Nuremberg humanist Willibald Pirckheimer, also owned a substantial and varied collection, but it is not known whether it also featured Brazilian material (Busch, 1973, p. 278-279). For artists in southern Germany like Dürer, Burgkmair, Altdorfer, or Breu it was therefore rather unproblematic to get access to objects collected in Brazil and to include their images in their works.

It is more questionable to what an extent these works may be regarded as 'ethnographic'. Stephanie Leitch (2009) has recently argued that Burgkmair's work was "the beginning of ethnography in print", and the argument may well be appropriate for his 1508 illustrations of Balthasar Springer's travel account. This work consisted of a seven and half feet long frieze made up of at least eight and possibly as many as thirteen woodcuts (Leitch, 2009, p. 136, 155, note 16), which mapped the peoples encountered by Springer on the coasts of Africa and Asia in a manner that invites comparison and the recognition of difference. Despite the fact that probably only a few copies were printed (no complete set has survived), Burgkmair's prints became an influential model for later illustrators, largely thanks to the inferior copies subsequently published with Springer's complete travel book. The two drawings (Figures 5 and 7) attributed to Burgkmair are, however, the only indication that he may have further pursued the visual approach to cultural diversity pioneered in 1508 by integrating material that had become available more recently.

Breu's woodcut (Figure 14) may equally be regarded as ethnographic, although the comparative approach is less obvious, because the other illustrations scattered throughout Varthema's book are mostly narrative and visualize events rather than generalize about people. But at least implicitly it draws an image of the 'People of Calicut', dressed in what only from a present-day point of view may be regarded as a strange mixture of Brazilian and Asian items or as "one of the rare cases of misplaced American Indians in the sixteenth century" (Colin, 1988, p. 191).

Dürer's drawing (Figure 17) obviously also depicts a man from Calicut and not a Tupinamba, and its intention was more religious than ethnographic. Even five years later, in the diary of his travels in the Low Countries, he expresses his hope that "all non-believers, Turks, heathen, Calacuttans" would be converted to Christianity (Rupprich, 1956, p. 171).

In the "Triumph of Maximilian" (Figures 11 and 12) the 'People of Calicut' made their appearance at the special request of the emperor who wanted to glory himself in the spurious claim that these strangers at the end of the known world had been subjected by his family. Burgkmair's expansion of the original design from one to three pages clearly shows his ethnographic interest and (as in the case of Dürer) his penchant for accuracy in representing details of material culture.

Contrary to widely published assumptions, none of the images here discussed are representations of Tupinambas, but of the 'People of Calicut'. As such they testify to early sixteenth-century beliefs in the identity of populations of the East and West Indies. Beyond that, however, they are unique documents preserving a valuable visual record of Tupinamba artifacts, which could never have been described in such precious detail by contemporary observers and which have not been preserved until today in museum collections.

Recebido em 21/05/2013

Aprovado em 05/08/2014

FEEST, Christian. The people of Calicut: objects, texts, and images in the Age of Proto-Ethnography. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi. Ciências Humanas, v. 9, n. 2, p. 287-303, maio-ago. 2014

- ALBISETTI, César; VENTURELLI, Angelo J. Enciclopédia Bororo Campo Grande: Museu Regional Dom Bosco, 1962. v. 1.

- ANAWALT, Patricia Rieff. Indian Clothing Before Cortés: Mesoamerican costumes from the Codices. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1981.

- APPADURAI, Arjun. Introduction: Commodities and the Politics of Value. In: APPADURAI, Arjun (Ed.). The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986. p. 3-63.

- APPLEBAUM, Stanley (Ed.). The Triumph of Maximilian I: 137 Woodcuts by Hans Burgkmair and Others. New York: Dover, 1964.

- BARTA, Roger. Wild Men in the Looking Glass: the Mythic Origins of European Otherness. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994.

- BUSCH, Renate von. Studien zu deutschen Antikensammlungen des 16. Jahrhunderts 1973. Thesis (Ph.D. in Altertums- und Kulturwissenschaften) - University of Tübingen, Tübingen, 1973.

- CLINE, Howard F. Hernando Cortés and the Aztec Indians in Spain. Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress, Washington,v. 26, n. 2, p. 70-90, 1969.

- COCHLAEUS, Johannes. De quinque zonis terre compendium. In: POMPONIUS MELA. Cosmographia Pomponij Mele: authoris nitidissimi tribus libris digesta. Nürnberg: J. Weissenburger, 1512. fol. F recto-G [iv] verso.

- COLIN, Susi. Das Bild des Indianers im 16. Jahrhundert Idstein: Schulz-Kirchner Verlag, 1988. (Beiträge zur Kunstgeschichte, n. 102).

- COLIN, Susi. The Wild Man and the Indian in Early 16th Century Book Illustration. In: FEEST, Christian (Ed.). Indians and Europe: an Interdisciplinary Collection of Essays. Aachen: Rader/Alano, 1987. p. 5-36.

- DEFERT, Daniel. Un Genre ethnographique profane au XVIe: les livres d'habits (Essai d'ethnographie). In: RUPP-EISENREICH, Britta (Ed.). Histoires d'anthropologie: XVI-XIX siècles. Paris: Klincksieck, 1984. p. 25-41.

- DOGGETT, Rachel (Ed.). New World of Wonders: European Images of the Americas, 1492-1700. Washington: Folger Shakespeare Library, 1992.

- DORTA, Sonia Ferraro. Coleções etnográficas: 1650-1955. In: CUNHA, Manuela Carneiro da (Ed.). História dos índios no Brasil São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, Secretaria Municipal de Cultura, FAPESP, 1992. p. 501-528.

- DORTA, Sonia Ferraro; CURY, Marília Xavier. A plumária indígena brasileira no Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia da USP São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo, 2001.

- DOS SANTOS LOPES, Marilia. "Kalikutisch Leut" im Kontext alt-neuer Weltbeschreibungen des 16. Jahrhunderts. In: LOMBARD, Denys; PTAK, Roderich (Eds.). Asia Maritima: images et réalité 1200-1800/Bilder und Wirklichkeit. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1994. p. 13-26.

- EGMOND, Florike; MASON, Peter. "These are the People who Eat Raw Fish": Contours of the Ethnographic Imagination in the Sixteenth Century. Viator. Medieval and Renaissance Studies, Los Angeles, v. 31, p. 311-360, 2000.

- FEEST, Christian. Mexican Turquoise Mosaics in Vienna. In: KING, J. C. H.; CARTWRIGHT, Caroline; MCEWAN, Colin (Eds.). Turquoise in Mexico and North America: science, conservation, culture and collections. London: Archetype Publications/British Museum, 2012a. p. 103-116.

- FEEST, Christian. El penacho del México antiguo en Europa In: HAAG, Sabine; MARIA Y CAMPOS, Alfonso de; RIVERO WEBER, Lilia; FEEST, Christian (Eds.). El penacho del México antiguo. Altenstadt: ZKF Publishers, 2012b. p. 5-28.

- FEEST, Christian. Moravians and the Development of the Genre of Ethnography. In: ROEBER, A. Gregg (Ed.). Ethnographies and Exchanges: Native Americans, Moravians, and Catholics in Early North America. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2008. p. 19-30.

- FEEST, Christian. Una evaluación europea del arte mexicano. In: ROSTKOWSKI, Joëlle; DEVERS, Sylvie (Eds.). Destinos cruzados: cinco siglos de encuentros con los amerindios. México, DF: Siglo Veintiuno, 1996. p. 93-104.

- FEEST, Christian. The Collecting of American Indian Artifacts in Europe, 1493-1750. In: KUPPERMAN, Karen O. (Ed.). America in European Consciousness, 1493-1750 Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press/Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1995. p. 324-360.

- FEEST, Christian. "Selzam ding von gold da von vill ze schreiben were": Bewertungen amerikanischer Handwerkskunst im Europa des frühen 16. Jahrhunderts. Jahrbuch der Willibald Pirckheimer Gesellschaft, Nürnberg, p. 105-120, 1992.

- FEEST, Christian. Vienna's Mexican Treasures: Aztec, Mixtec, and Tarascan Works from 16th century Austrian Collections. Archiv für Völkerkunde, Wien, v. 45, p. 1-64, 1990.

- FEEST, Christian. Mexico and South America in the European Wunderkammer. In: MACGREGOR, Arthur; IMPEY, Oliver (Eds.). The Origins of Museums Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985. p. 237-244.

- FEEST, Christian; LUIZA DA SILVA, Viviane. Between Tradition and Modernity: the Bororo in Photographs of the 1930s. Archiv für Völkerkunde, Wien, v. 59-60, p. 167-202, 2011.

- HAMPE, Theodor(Ed.).Das Trachtenbuch des Christoph Weiditz von seinen Reisen nach Spanien (1529) und den Niederlanden (1531/32) Berlin: W. de Gruyter, 1927.

- HAMY, Étienne-Théodore. Les Indiens de Rasilly: étude iconographique et ethnographique. Journal de la Société des Américanistes, Paris, v. 5, p. 20-52, 1908.

- HONOUR, Hugh. The New Golden Land: European Images of America from the Discoveries to the Present Time. New York: Pantheon Books, 1975.

- KÜNAST, Hans-Jörg. Die Graphiksammlung des Augsburger Stadtschreibers Konrad Peutinger. In: PAAS, John Roger (Ed.). Augsburg, die Bilderfabrik Europas Augsburg: Wissner, 2001. p. 11-19.

- LEITCH, Stephanie. Burgkmair's "Peoples of Africa and India" (1508) and the Origins of Ethnography in Print. The Art Bulletin, New York, v. 91, n. 2, p. 134-159, 2009.

- LEVENSON, Jay A. (Ed.). Encompassing the Globe: Portugal e o mundo nos séculos XVI e XVII. Lisboa: Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, 2009.

- LEVENSON, Jay A. (Ed.). Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991.

- MACGREGOR, Arthur. Curiosity and Enlightenment New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

- MCEWAN, Colin. Ancient American Art in Detail London: British Museum Press, 2009.

- MÉTRAUX, Alfred. La Civilisation matérielle des tribus Tupi-Guarani Paris: P. Geuthner, 1928.

- MEYER, A. B.; UHLE, Max. Seltene Waffen aus Afrika, Asien und Amerika Dresden: Königliches Ethnographisches Museum zu Dresden, 1885.

- Osterwold, Tilman; Pollig, Hermann (Eds.). Exotische Welten, Europäische Phantasien Stuttgart: Edition Canz, 1987.

- RAMUSIO, Giovanni Battista. Delle navigationi et viaggi raccolte da M. Gio. Battista Ramusio Venezia: Appresso i Giunti, 1556. 3 v.

- RIBEIRO, Berta M. Bases para uma classificação dos adornos plumários dos índios do Brasil. Arquivos do Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, v. 43, p. 59-116, 1957.

- ROTH, Harriet (Ed.). Der Anfang der Museumslehre in Deutschland: das Traktat "Inscriptiones vel Tituli Theatri Amplissimi" von Samuel Quiccheberg. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 2000.

- ROWE, John Howland. The Renaissance Foundations of Anthropology. American Anthropologist, v.67, n. 1, p. 1-20, 1965.

- RUPPRICH, Hans (Ed.).Dürer: Schriftlicher Nachlass. Berlin: Deutscher Verein für Kunstwissenschaft, 1956. v. 1.

- RYDÉN, Stig. Brazilian Anchor Axes. Ethnological Studies, Stockholm, v. 4, p. 50-83, 1937.

- SPRINGER, Balthasar. Die Merfart und Erfarung nüwer Schiffung Oppenheim: Jakob Köbel, 1509.

- STADEN, Hans. Warhaftige Historia und Beschreibung eyner Landtschafft der wilden, nacketen, grimmigen Menschfresser Leuthen in der Newenwelt America gelegen Marburg: Andres Kolben, 1557.

- STAGL, Justin. A History of Curiosity: the Theory of Travel, 1550-1800. Chur: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1995.

- STURTEVANT, William C. La Tupinambisation des Indiens de l'Amérique du Nord. In: THERRIEN, Gilles (Ed.). Les Figures de l'Indien Montréal: Université du Québec, 1988. (Les Cahiers du Département d'Études Littéraires, v. 9).

- STURTEVANT, William C. First Visual Images of Native America. In: CHIAPELLI, Fredi (Ed.). First Images of America Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976. v. 1, p. 417-454.

- THEVET, André. Les Singularitez de la France antarctique, autrement nommé Amérique Paris: Les heritiers de Maurice de la Porte, 1558.

- VARTHEMA, Lodovico de. Die ritterlich und lobwirdig Rayß des gestrengen und über all ander weit erfarnen Ritters und Lantfarers Herrn Ludowico Vartomans von Bolonia Augsburg, 1515.

- WINZINGER, Franz. Albrecht Altdorfer: die Gemälde, Tafelbilder, Miniaturen, Bildhauerarbeiten, Werkstatt und Umkreis. München: Hirmer, 1975.

- WINZINGER, Franz. Die Miniaturen zum Triumphzug Kaiser Maximilians I Graz: ADEVA, 1972-1973. 2 v.

- ZERRIES, Otto. Das ausserandine Südamerika. In: LEUZINGER, Elsy (Ed.). Kunst der Naturvölker Frankfurt am Main: Propyläen-Verlag, 1978. (Propyläen-Kunstgeschichte, v. 22).

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

23 Sept 2014 -

Date of issue

Aug 2014

History

-

Received

21 May 2013 -

Accepted

05 Aug 2014