Abstract

This paper reports a case study that discusses issues related to the reconstruction of kinship terminology in Proto-Tupi, based on previous work by Araújo and Storto (2002) on the Arikém and Juruna subfamilies. It also presents the remaining kin terminology of the Karitiana language (Arikém branch or subfamily) which was not discussed in the case study. Comparing Karitiana (Landin, 1989) and Juruna (Lima, 1995) kin terminology, Araújo and Storto (2002) have shown that some cognates can be found in the two languages and proposed that they reconstruct in Proto-Tupi. These authors claim that these reconstructed items indicate the following hypotheses: (1) the speakers of Proto-Tupi (4500 BP) had a Dravidian kinship system; (2) the speakers of Proto-Tupi had a kinship and naming system in which ego was equated with the paternal grandparent of the same sex as ego. Besides the 11 cognates discussed by Araújo and Storto (2002), we discuss the remaining 19 kin terms that form the Karitiana kinship system according to Landin (1989).

Keywords

Karitiana; Arikém; Juruna; Tupi; Kinship; Reconstruction

Resumo

Neste artigo, temos como objetivo relatar um estudo de caso que discute questões relacionadas à reconstrução de terminologia de parentesco em Proto-Tupi baseados em um trabalho de Araújo e Storto (2002) nas subfamílias Ariké e Juruna, bem como apresentar o restante da terminologia de parentesco na língua Katitiana (ramo Arikém), não discutida no estudo de caso. Comparando a terminologia de parentesco em Karitiana (Landin, 1989) e Juruna (Lima, 1995), Araújo e Storto (2002) mostraram que alguns cognatos podem ser encontrados nas duas línguas, e propuseram que eles se reconstroem em Proto-Tupi. As autoras afirmam que estes itens reconstruídos corroboram as seguintes hipóteses: (1) que os falantes de Proto-Tupi (4500 AP) tinham um sistema dravidiano de parentesco, no qual ego era identificado com o avô ou a avó paternos (do mesmo sexo que ego). Além dos 11 termos discutidos por Araújo e Storto (2002), apresentamos uma discussão dos 19 termos restantes do sistema de parentesco Karitiana de acordo com Landin (1989).

Palavras-chave

Karitiana; Arikém; Juruna; Tupi; Parentesco; Reconstrução

INTRODUCTION TO THE TUPIAN FAMILY

The Tupian family is composed of 10 language branches, as depicted in Table 1. The most numerous and geographically widespread branch is Tupi-Guarani, which has 40 dialects belonging to 22 living languages (Moore et al., 2008MOORE, Denny; GALUCIO, Ana Vilacy; GABAS JR., Nilson. O desafio de documentar e preservar as línguas amazônicas. Scientific American Brasil, Pinheiros, n. 76, p. 36-43, set. 2008. (Amazônia, a floresta e o futuro).), many of which are mutually intelligible. The remaining 9 branches have 20 languages. Excluding Tupi-Guarani, only two branches have more than 2 languages: Mondé (6) and Tupari (5). The others today can be considered single-language branches because Kuruaya (in the Munduruku family) is now extinct, while Xipaya (Juruna family) has only 2 elderly speakers.

Tupian branches and languages (Rodrigues, 1986RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna. Línguas brasileiras: para o conhecimento das línguas indígenas. São Paulo: Edições Loyola, 1986., 1999; Moore et al., 2008MOORE, Denny; GALUCIO, Ana Vilacy; GABAS JR., Nilson. O desafio de documentar e preservar as línguas amazônicas. Scientific American Brasil, Pinheiros, n. 76, p. 36-43, set. 2008. (Amazônia, a floresta e o futuro).).

Tupian languages (excluding Tupi-Guarani). Map adapted from Rodrigues (1999)RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna. Tupi. In: Dixon, Robert; AIKHENVALD, Alexandra (ed.). The Amazonian Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. p. 107-123..

Geographically, 5 branches of the Tupian language family are spoken in the state of Rondônia (RO) and another 5 outside this state, which Rodrigues (1964)RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna. A classificação do tronco lingüístico Tupí. Revista de Antropologia, São Paulo, v. 12, n. 1/2, p. 99-104, jun./dez. 1964. considers to be the homeland of this family. Rodrigues (2007)RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna. As consoantes do Proto-Tupi. In: RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna; CABRAL, Ana Suely Arruda (org.). Línguas e culturas Tupí. Brasília: LALI; Campinas: Editora Curt Nimuendajú, 2007. v. 1, p. 167-203. suggests a genetic division within the Tupian family between Eastern languages (not spoken in RO) and Western languages (RO languages).

In the more conservative diagram (Galucio et al., 2015GALUCIO, Ana Vilacy; MEIRA, Sérgio; BIRCHALL, Joshua; MOORE, Danny; GABAS JR., Nilson; DRUDE, Sebastian; STORTO, Luciana; PICANÇO, Gessiane; REIS RODRIGUES, Carmen. Genealogical relations and lexical distances within the Tupian linguistic family. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi. Ciências Humanas, Belém, v. 10, n. 2, p. 229-274, maio/ago. 2015. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1981-81222015000200004.

https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-81222015000...

) depicted in Figure 2, the 10 branches are grouped into 7 main groups: (1) Mawé-Aweti-Tupi Guarani on the right side (3 branches in 1); (2) Ramarama-Puruborá in the middle (2 branches grouped in 1); (3) One branch corresponding to each remaining group (5 branches). These are the well- known and accepted genetic relationships already established inside the Tupian family.

Tupian Family. Taken from Galucio et al. (2015)GALUCIO, Ana Vilacy; MEIRA, Sérgio; BIRCHALL, Joshua; MOORE, Danny; GABAS JR., Nilson; DRUDE, Sebastian; STORTO, Luciana; PICANÇO, Gessiane; REIS RODRIGUES, Carmen. Genealogical relations and lexical distances within the Tupian linguistic family. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi. Ciências Humanas, Belém, v. 10, n. 2, p. 229-274, maio/ago. 2015. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1981-81222015000200004.

https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-81222015000... .

SUMMARY OF Araújo AND Storto (2002)

In comparisons of Juruna (Lima, 1995LIMA, Tânia Stolze. A parte do Cauim: etnografia juruna. 1995. Tese (Doutorado em Antropologia Social) - Museu Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 1995.) and Karitiana (Landin, 1989LANDIN, Rachel Mary. Kinship and naming among the Karitiana of Northwestern Brazil. 1989. Thesis (Master in Anthropology) - University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, 1989.; Lucio, 1996Lucio, Carlos Frederico. Sobre algumas formas de classificação social: etnografia sobre os Karitiana de Rondônia (Tupi-Arikém). 1996. Dissertação (Mestrado em Antropologia Social) – Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 1996.) kinship terminology, some terms common to both languages have been identified and proposed to reconstruct in Proto-Tupi. These authors claim that these reconstructed items raise the following hypotheses:

-

The speakers of Proto-Tupi (4500 BP) had a Dravidian kinship system.

-

The speakers of Proto-Tupi had a kinship and naming system in which ego was equated with a paternal grandparent of the same sex as ego.

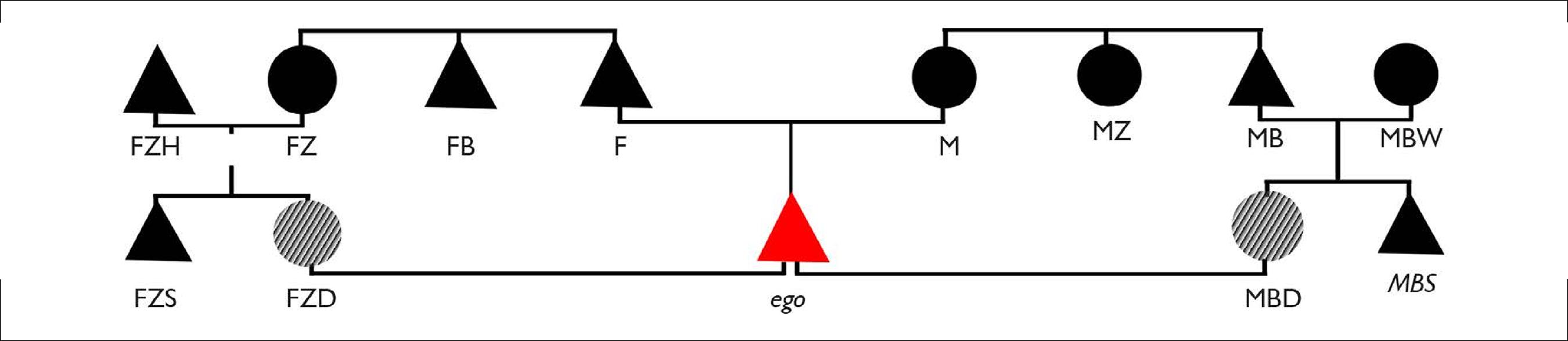

Preferential marriage in Dravidian kinship systems is with cross-cousins, who are not the children of parent figures (parallel uncles and aunts), but rather the offspring of ‘father’s sister’ (FZ) and ‘mother’s brother’ (MB), as shown in Figure 3 for a male ego (triangle in red). The evidence offered in favor of the first hypothesis is that kin terms for parallel uncles and aunts (‘father’s brothers’ [FB] and ‘mother’s sisters’ [MZ]) are linguistically derived from the terms for ‘father’ (F) and ‘mother’ (M), respectively. Because they are children of parent figures, parallel cousins (the children of ‘mother’s sister’ [MZ] or ‘father’s brother’ [FB]) are considered siblings by ego (MZ is considered an extension of ‘mother’ and FB is considered as an extension of ‘father’).

As seen in Table 2, syp, the word for ‘father’ (female speaking) in Karitiana, comprises the words for ‘father’s brother’ (FBs), sypyty (eFB: ‘elder father’s brother’), and sypysin (yFB: ‘younger father’s brother’), while ti, the word for ‘mother,’ is the source of the words for ‘mother’s sisters’ (MZs), tiity (eMZ) and ti’et (eMZ):

Parallel uncles and aunts in Karitiana: terms derived from ‘father’ and ‘mother.’1 1 The orthographic conventions used for Karitiana are a result of a literacy project coordinated by Luciana Storto and funded by the Norwegian Rainforest Foundation together with 6 other projects by linguists who at that time (1994-1997) were affiliated withMuseu Paraense Emílio Goeldi. Kinship terms mentioned by Landin (1989) in her MA were adapted to the new orthography adopted as of 1994. Lucio (1996) also used Rachel Landin’s terminology in his MA. The orthographic symbols y and ’ stand for a high central vowel[ɨ] and a glottal stop [Ɂ], respectively. The symbol j is a palatal approximant (or a palatal nasal when j? ).

The other morphemes involved in the formation of these terms are -ty (‘big’), -’et (‘child,’ used exclusively by a woman in reference to her sons or daughters), and -sin, probably derived from the root ’in (‘small’). This is understandable since the elder brother and sister of a parent are their own big brothers and sisters, while the younger brother of a man is his little brother. Women probably address aunts who are their mother’s younger sisters as ti’et, which consists of the lexical items for ‘mother’ and ‘child’ (woman speaking) and can be translated as ‘mother’s child’ because these women’s mothers may have raised their younger sisters as if they were their own children. Proof of this hypothesis is that the word ‘dog’ in Karitiana, ombaky by-’et-na [jaguar causative-child-adjectivizer] involves the term ’et in its formation and is derived from ‘jaguar,’ meaning ‘domesticated/raised jaguar,’ suggesting that ’et literally means ‘raised.’

It is not clear why a male ego would call his father’s brothers by terms derived from syp, since this is the term used by a female to call her father, but we believe that this is the old term for ‘father’ which at one time was used by both male and female egos (indeed it reconstructs in Proto-Tupi, as we will see below). Another possibility is that the other term for ‘father,’ used exclusively by male egos, cannot be directed to non-progenitors, that is, to classificatory ‘fathers.’ This same question can be raised for the term ’et, which is surprisingly used by a male ego to describe his father’s younger brother in sypy’et, considering that ’et is the term used by a female ego for her children. One possibility is that ’et does not literally mean ‘child,’ but instead may be used to denote any children raised by ego. In this interpretation, an older brother could raise his own younger brother, as proposed above with regard to ti’et (younger mother’s sister). These possible explanations are suppositions and should not be taken as correct analysis; what is clear, nonetheless, is that the terms for ‘mother’s sister’ and ‘father’s brother’ are derived from ‘mother’ and ‘father,’ respectively, while other types of uncles and aunts are not (as seen in Table 8).

Table 3 shows a similar situation in Juruna, although in this language there is no difference between male and female terms. Younger siblings of the same sex are always derived with the root iza, and elder siblings of the same sex are derived using the root i’uraha.

At first inspection it seems that the roots for ‘father’ from which the words for ‘father’s brother’ are derived are unrelated in Karitiana and Juruna, since all they have in common is the consonant p. However, we know for a fact that the Karitiana word syp [sɨp] and the Juruna word –pa for ‘father’ are cognates that reconstruct in Proto-Tupi (Table 4):

According to Rodrigues (2005)RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna. As vogais orais do Proto-Tupi. In: RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna; CABRAL, Ana Suelly Arruda Câmara (org.). Novos estudos sobre línguas indígenas. Brasília: Editora UnB, 2005. p. 35-43., the word for ‘father’ in PT is reconstructed as *-up. Other reconstructions proposed involve *D (possibly a lateral fricative) for the first consonant in Proto-Tupari by Moore and Galucio (1994)MOORE, Denny; GALUCIO, Ana Vilacy. Reconstructions of Proto-Tupari consonants and vowels. Survey of California and Other Indian Languages, Berkeley, n. 8, p. 119-137, 1994. and *T (possibly [c] or [tj]) for Pre-Maweti-Guarani by Meira and Drude (2013)MEIRA, Sérgio; DRUDE, Sebastian. Sobre a origem histórica dos “prefixos relacionais” das Línguas Tupi-Guarani. Cadernos de Etnolingüística, v. 5, n. 1, p. 1-30, maio 2013..

Furthermore, Araújo and Storto (2002)ARAÚJO, Carolina; STORTO, Luciana. Terminologia de parentesco em Karitiana e Juruna: uma comparação de algumas equações entre categorias paralelas e gerações alternas. In: ENCONTRO INTERNACIONAL DO GRUPO DE TRABALHO SOBRE LÍNGUAS INDÍGENAS DA ANPOLL, 1., 2002, Brasília. Atas [...]. Brasília: Editora UnB, 2002. p. 430-442. show that the words for ‘mother’ in Karitiana and Juruna originate from two different roots (Table 5), one of which (in Juruna) may have been a vocative in Proto-Tupi, because the lexical item Rodrigues (2005)RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna. As vogais orais do Proto-Tupi. In: RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna; CABRAL, Ana Suelly Arruda Câmara (org.). Novos estudos sobre línguas indígenas. Brasília: Editora UnB, 2005. p. 35-43. reconstructs for ‘mother’ in Proto-Tupi (PT) is *tʃɨ.

In Karitiana there are two words for ‘father:’ one is the cognate mentioned above, while the other is ’it, the same word as ‘child’ (father speaking). This is because the male ego’s son is identified with ego’s father, as we shall see below. The term ’it can be literally translated as ‘larvae’ or ‘semen.’ In other words, a man will call his children of either sex y’it, literally ‘my semen,’ but for obvious reasons, only a son will call his father by the same term. The daughter, devoid of semen, will call him ysyp ‘my father,’ using the cognate already discussed in Table 4.

This is reflected in the naming system of Karitiana and Juruna: a child will receive the same name as his father’s parent of the same sex. It also helps to explain another kinship category that reconstructs in Proto-Tupi, *amõj (Rodrigues, 2007RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna. As consoantes do Proto-Tupi. In: RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna; CABRAL, Ana Suely Arruda (org.). Línguas e culturas Tupí. Brasília: LALI; Campinas: Editora Curt Nimuendajú, 2007. v. 1, p. 167-203.) which refers to the grandparent who is a namegiver but not to other types of grandparents (Table 6):

The term ombyj [õmbɨj] in Table 6 is derived from [õn] ‘1st person’ (present in Proto-Arikém, the immediate mother language of the Arikém branch, as an alternative to the cognate prefix currently used in Karitiana for the same meaning, which is [ɨ-]) plus the root byj [bɨj] ‘chief, boss.’ The reciprocal term, which grandparents use to address the grandchildren who bear their names, is ongot, and may have derived historically from an archaic Proto-Arikém form of 1st person õn and the adjective got (‘young’), literally ‘me young’ or ‘I as a youth.’ This hypothetical etymology may not work in other Tupian families, but this cognate clearly exists in both Juruna and Arikém (subfamilies that are very different from each other inside the Tupian family) as it exists in Mondé and Aweti, suggesting that the special status of a grandparent who is a namegiver also exists elsewhere.

Araújo and Storto (2002)ARAÚJO, Carolina; STORTO, Luciana. Terminologia de parentesco em Karitiana e Juruna: uma comparação de algumas equações entre categorias paralelas e gerações alternas. In: ENCONTRO INTERNACIONAL DO GRUPO DE TRABALHO SOBRE LÍNGUAS INDÍGENAS DA ANPOLL, 1., 2002, Brasília. Atas [...]. Brasília: Editora UnB, 2002. p. 430-442. have suggested that the words used for ‘father’ and ‘mother’ in Karitiana and Juruna reconstruct in Proto-Tupi (both the term reconstructed by Rodrigues [2007]RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna. As consoantes do Proto-Tupi. In: RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna; CABRAL, Ana Suely Arruda (org.). Línguas e culturas Tupí. Brasília: LALI; Campinas: Editora Curt Nimuendajú, 2007. v. 1, p. 167-203. and Rodrigues and Cabral [2012]RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’ Igna; CABRAL, Ana Suelly Arruda Câmara. Tupían. In: CAMPBELL, Lyle; GRONDONA, Verónica (ed.). The indigenous languages of South America: a comprehensive guide. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, 2012. p. 495-574. (The World of Linguistics, 2). as *tʃɨ and the one used as a vocative in Mekéns, which appears in three subfamilies, Puruborá, Tupari and Juruna). Since they derive the kinship terms for MZ and FB in these two languages, respectively, it is possible that Proto-Tupi had a Dravidian kinship system. The naming system in Karitiana and Juruna reflects an equation in which ego’s paternal grandparent of the same sex as ego provides a name for their grandchildren of the same sex. Since the term for this kinship category reconstructs in Proto-Tupi, the language may have featured the same equation in its kinship and naming system.

To sum up this section, 11 Karitiana kinship terms have been discussed: ‘father’ (male speaking), ‘father’ (female speaking), ‘child’ (male speaking), ‘child’ (female speaking), ‘mother,’ ‘elder father’s brother,’ ‘younger father’s brother,’ ‘elder mother’s sister,’ ‘younger mother’s sister,’ ‘grandchild’ (grandparent’s namesake), and ‘grandparent’ (namegiver speaking). These terms have been compared with what has been described by Lima (1995)LIMA, Tânia Stolze. A parte do Cauim: etnografia juruna. 1995. Tese (Doutorado em Antropologia Social) - Museu Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 1995. about Juruna kinship. The reconstruction of a few kinship terms can lead us to formulate hypotheses about the social organization of the Proto-Tupi people (4500 BP) as well as the internal branching of Tupian:

-

They had a Dravidian kinship system, or at least the language which was the mother language to both the Juruna and the Arikém family had a Dravidian system.

-

Ego was identified with the paternal grandparent of the same sex as ego, with reflections in the onomastic (naming) system, if not in Proto-Tupi, at least in a putative intermediate language which was a mother language to the Arikém and Juruna families. If Rodrigues (2007)RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna. As consoantes do Proto-Tupi. In: RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna; CABRAL, Ana Suely Arruda (org.). Línguas e culturas Tupí. Brasília: LALI; Campinas: Editora Curt Nimuendajú, 2007. v. 1, p. 167-203. is correct about the family having an Eastern and a Western branch, Karitiana and Juruna could not have descended from any other mother language than Proto-Tupi because they are as different as two Tupian languages can be (see Figure 4).

Tupian Family. Adapted from Rodrigues (2007)RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna. As consoantes do Proto-Tupi. In: RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna; CABRAL, Ana Suely Arruda (org.). Línguas e culturas Tupí. Brasília: LALI; Campinas: Editora Curt Nimuendajú, 2007. v. 1, p. 167-203..

REMAINING KIN TERMS IN KARITIANA

Besides the 11 terms already discussed, there are 19 additional kinship terms in Karitiana which are relevant for historical linguistic studies and should be compared with Tupian languages from other subfamilies in search of cognates (Table 7):

Table 7 displays the terminology for ‘siblings.’ Same-sex siblings are divided by age and sex of alter, resulting in a system in which the term haj is used for 2 categories, namely ‘elder brother’ and ‘elder sister’ (eB=eZ), which could also be denoted ‘same-sex elder sibling.’ Opposite-sex siblings are divided by the sex of ego (pan’in for male ego and syky for female ego), as are same-sex younger siblings (ket for male ego and kypeet for female ego).

Ego’s ‘paternal uncles’ (FB) and ‘paternal aunts’ (FZ) are divided by the sex of alter: sokit is the term for ‘paternal aunts’ (FZ). ‘Paternal uncles’ (father figures) are divided by sex according to the age of alter, as seen in Table 2. ‘Maternal uncles’ (MB) are divided by the sex of ego: ta’it for male ego (perhaps formed by ta- a 3rd person anaphoric possessive pronoun and ’it father/son, possibly meaning ‘his son/father’) and syky’et for female ego (Table 8).

One possible explanation for these two terms may be related to the fact that maternal uncles (MB) are not father figures in the system. Instead they are the fathers of potential marriage partners (cross-cousins), in other words, ego’s potential father-in-law. Ta’it could then mean ‘his father (not mine).’ A woman may marry the uncle she calls syky’et (avunculate). This term could be a compound of syky (‘mother’s brother’) and ’et (‘child’), meaning ‘mother’s brother who was raised as a child’ because a woman’s potential husband in an avunculate system is called syky (younger brother) by her mother, who probably cared for and raised him when he was a child like a mother. Although these etymologies are unlikely to be correct, we prefer to propose them here as a contribution to the debate on kinship terms in Proto-Tupi rather than not suggest them at all.

The ‘nephew’ category (Table 9) is divided by ego (maternal or paternal line) as well as the sex of ego: a paternal nephew of a male ego is called ’it ogot (‘father’s namesake’ or ongot) and his paternal niece is called ti ogot (‘mother’s namesake’ or ongot). This is understandable because these nephews and nieces are the namesakes of the male ego’s parents.

All other nephews and nieces of a male ego will be called saka’et (literally ‘child of saka’). Saka itself is not a kin term in the system, but if it were it would mean ‘man’s sister’ (which in the kinship system is pan’in). The maternal niece of a female ego is ti ogot (‘mother’s namesake’), while other nephews and nieces are divided by the age of ego’s sister (their mother). The children of ego’s older sister are called haja’et (‘elder sibling’s child’) and the children of ego’s younger sister are koroj͂ ’et (‘child of koroj͂;’ the root koroj͂ does not appear in the kin terminology by itself, but if it did it would mean ‘woman’s younger sister,’ which is kypeet in the Karitiana kin terminology). It would be interesting to look for cognates for saka and koroj͂ in other Tupian languages to see if our hypotheses about what they might mean are well-founded historically.

Grandparents who are not namegivers or ombyj (‘my chief’) are called owoj (male) and timoj͂ (female), as shown in Table 10.

We have seen that ongot (‘me as a youth’) is the term for a grandchild who is the grandparent’s namesake. Other types of grandchildren are sokite’et (‘paternal aunt’s child’) for a male ego and ete’et (‘child’s child’) for a female ego. The morpheme ’et means ‘child, young’ (in other words, son and daughter, used by a woman), so ete’et is ‘child’s child,’ which is understandable as a compound for ‘grandchild’ (used by a woman). However, we do not understand why a man would call his grandchildren ‘paternal aunt’s child’ unless his son married his father’s paternal aunt.

Landin (1989)LANDIN, Rachel Mary. Kinship and naming among the Karitiana of Northwestern Brazil. 1989. Thesis (Master in Anthropology) - University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, 1989. mentions that there are no kin terms for cross-cousins in Karitiana. She explains that this may be because these categories are preferential for marriage to ego, and hypothesizes that the traditional terms used for these categories could have been man (‘husband’) and sooj (‘wife’), totaling 2 terms. The total kinship system has 30 terms, according to Landin (1989)LANDIN, Rachel Mary. Kinship and naming among the Karitiana of Northwestern Brazil. 1989. Thesis (Master in Anthropology) - University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, 1989.. The same author also points out that the Karitiana combine the Dravidian system with avunculate (preferential marriage of a man to his sister’s daughter), which we found to be correct in our own fieldwork.

FINAL CONCLUSIONS

The Dravidian Rule, which is present in the Karitiana kinship system, guarantees the expansion of the kinship category father (F) to include the category father’s brother (FB) and mother (M) to include mother’s sister (MZ), who become parent figures to ego. This is corroborated by the terminology used for FB and MZ, all of which derive from the words for father and mother, respectively, while terms for other types of uncles and aunts do not. The Dravidian Rule implies that cousins who are children of the expanded categories are like brothers (B) and sisters (Z) to ego. These are parallel cousins and marriage with them is not possible. The consequence is that cross-cousins (in other words, cousins who are not parallel cousins) become the preferable marriage partners in ego’s generation. There are no kin terms in Karitiana for such cousins, possibly because the terms husband and wife may have been used for them.

There is a second type of preferential marriage among the Karitiana above ego’s generation. It is possible for a woman to marry her mother’s brother (avunculate). The word for this kin term may be tentatively translated as ‘mother’s brother who was raised by her.’ In the category ‘nephews’ there are two kin terms which are compounds of some terms that are not part of the system; ‘grandchildren’ of a male ego who are not his namesakes are called a term that is puzzling in our analysis unless boys marry their father’s sister. If this is the case, it is an extension of the avunculate relationship.

Additionally, paternal grandparents are namegivers and the term for father is different for boys and girls because one of these terms derives from the word ‘larvae’ or ’semen.’ A father calls his children ‘my semen,’ and this is also what a boy calls his father, since boys are identified with their paternal grandfather (a namegiver) in the kinship and naming system.

Considering that Juruna and Karitiana share the Dravidian Rule and onomastic practices according to which the paternal grandfather or grandmother are special kin categories because they name their grandchildren, we hypothesize that Proto-Tupi had a Dravidian kinship system and a kinship term for a namegiving grandparent.

-

1

The orthographic conventions used for Karitiana are a result of a literacy project coordinated by Luciana Storto and funded by the Norwegian Rainforest Foundation together with 6 other projects by linguists who at that time (1994-1997) were affiliated withMuseu Paraense Emílio Goeldi. Kinship terms mentioned by Landin (1989)LANDIN, Rachel Mary. Kinship and naming among the Karitiana of Northwestern Brazil. 1989. Thesis (Master in Anthropology) - University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, 1989. in her MA were adapted to the new orthography adopted as of 1994. Lucio (1996)Lucio, Carlos Frederico. Sobre algumas formas de classificação social: etnografia sobre os Karitiana de Rondônia (Tupi-Arikém). 1996. Dissertação (Mestrado em Antropologia Social) – Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 1996. also used Rachel Landin’s terminology in his MA. The orthographic symbols y and ’ stand for a high central vowel[ɨ] and a glottal stop [Ɂ], respectively. The symbol j is a palatal approximant (or a palatal nasal when j? ).

REFERENCES

- ARAÚJO, Carolina; STORTO, Luciana. Terminologia de parentesco em Karitiana e Juruna: uma comparação de algumas equações entre categorias paralelas e gerações alternas. In: ENCONTRO INTERNACIONAL DO GRUPO DE TRABALHO SOBRE LÍNGUAS INDÍGENAS DA ANPOLL, 1., 2002, Brasília. Atas [...]. Brasília: Editora UnB, 2002. p. 430-442.

- GALUCIO, Ana Vilacy; MEIRA, Sérgio; BIRCHALL, Joshua; MOORE, Danny; GABAS JR., Nilson; DRUDE, Sebastian; STORTO, Luciana; PICANÇO, Gessiane; REIS RODRIGUES, Carmen. Genealogical relations and lexical distances within the Tupian linguistic family. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi. Ciências Humanas, Belém, v. 10, n. 2, p. 229-274, maio/ago. 2015. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1981-81222015000200004.

» https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-81222015000200004 - LANDIN, Rachel Mary. Kinship and naming among the Karitiana of Northwestern Brazil 1989. Thesis (Master in Anthropology) - University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, 1989.

- LIMA, Tânia Stolze. A parte do Cauim: etnografia juruna. 1995. Tese (Doutorado em Antropologia Social) - Museu Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 1995.

- Lucio, Carlos Frederico. Sobre algumas formas de classificação social: etnografia sobre os Karitiana de Rondônia (Tupi-Arikém). 1996. Dissertação (Mestrado em Antropologia Social) – Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 1996.

- MEIRA, Sérgio; DRUDE, Sebastian. Sobre a origem histórica dos “prefixos relacionais” das Línguas Tupi-Guarani. Cadernos de Etnolingüística, v. 5, n. 1, p. 1-30, maio 2013.

- MOORE, Denny; GALUCIO, Ana Vilacy; GABAS JR., Nilson. O desafio de documentar e preservar as línguas amazônicas. Scientific American Brasil, Pinheiros, n. 76, p. 36-43, set. 2008. (Amazônia, a floresta e o futuro).

- MOORE, Denny; GALUCIO, Ana Vilacy. Reconstructions of Proto-Tupari consonants and vowels. Survey of California and Other Indian Languages, Berkeley, n. 8, p. 119-137, 1994.

- RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’ Igna; CABRAL, Ana Suelly Arruda Câmara. Tupían. In: CAMPBELL, Lyle; GRONDONA, Verónica (ed.). The indigenous languages of South America: a comprehensive guide. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, 2012. p. 495-574. (The World of Linguistics, 2).

- RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna. As consoantes do Proto-Tupi. In: RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna; CABRAL, Ana Suely Arruda (org.). Línguas e culturas Tupí Brasília: LALI; Campinas: Editora Curt Nimuendajú, 2007. v. 1, p. 167-203.

- RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna. As vogais orais do Proto-Tupi. In: RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna; CABRAL, Ana Suelly Arruda Câmara (org.). Novos estudos sobre línguas indígenas Brasília: Editora UnB, 2005. p. 35-43.

- RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna. Tupi. In: Dixon, Robert; AIKHENVALD, Alexandra (ed.). The Amazonian Languages Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. p. 107-123.

- RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna. Línguas brasileiras: para o conhecimento das línguas indígenas. São Paulo: Edições Loyola, 1986.

- RODRIGUES, Aryon Dall’Igna. A classificação do tronco lingüístico Tupí. Revista de Antropologia, São Paulo, v. 12, n. 1/2, p. 99-104, jun./dez. 1964.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

29 Apr 2019 -

Date of issue

Jan-Apr 2019

History

-

Received

18 Apr 2018 -

Accepted

23 Jan 2019