Abstracts

This is a qualitative study that aims to discuss the trajectories of people with chronic sores on the lower limbs, focusing on their affective and sexual experiences. Fifty-one adult outpatients participated and they received care at the infirmary of a public hospital in Salvador - Bahia, between 2008 and 2009. Data was collected through techniques that included themed-story drawings and in-depth interviews, during therapeutic listening sessions, followed by an analysis of the content and an analysis of the drawing contents. Three categories emerged: solitary sexual-affective trajectory, fragmented sexual-affective trajectory, and continuous or linear sexual-affective trajectory. It was concluded that the limitations imposed by sores influence the subjectivity of these people, leading them to processes of loss of self-confidence, self-deprecation and fear of sexual- affective demands. It becomes clear, therefore, for the need to promote, not only curative interventions for the body, but also to include therapeutic listening and psychological support in the assistance offered to these people.

Holistic nursing; Sexuality; Chronic disease; Body image

Estudo qualitativo com o objetivo de discutir as trajetórias de pessoas com feridas crônicas nos membros inferiores, focando as experiências afetivas e sexuais. Participaram 51 adultos atendidos num ambulatório de hospital público em Salvador, Bahia, entre 2008 e 2009. Os dados foram obtidos através do desenho estória-tema e de entrevistas em profundidade, durante a escuta terapêutica. Em seguida foram submetidos à análise de conteúdo temática e à análise de conteúdo para desenhos, respectivamente, surgindo três categorias: "trajetórias solitárias", "fragmentadas" e "lineares ou contínuas". Conclui-se que as limitações corporais impostas pelas feridas influenciam a subjetividade dessas pessoas, conduzindo-as a processos de perda da autoconfiança, autodepreciação e temor quanto a demandas afetivo-sexuais. Torna-se, pois, evidente a necessidade da promoção, não apenas de intervenções curativas para o corpo, mas também da escuta terapêutica e do apoio psicológico durante o cuidado proporcionado a essas pessoas.

Enfermagem holística; Sexualidade; Doença crônica; Imagem corporal

Estudio cualitativo objetivó analizar las trayectorias de personas heridas crónicas en las piernas, enfocándose las experiencias emocionales y sexuales. Participaron 51 adultos, atendidos en un hospital público de Salvador, en Bahia. Los datos fueron recolectados en la escucha terapéutica a través del diseño de la historia-tema y la entrevista en profundidad. A continuación se sometieron al análisis de contenido temático y análisis de contenido para dibujos. Los datos revelaron tres categorías: Las trayectorias solitarias, fragmentadas y lineales o continuas. Se concluye que las limitaciones impuestas por las heridas influyen en la subjetividad de esas personas llevándolas a la pérdida de confianza en sí mismas, autodesprecio y miedo de afrontar las demandas afectivo-sexuales, es necesario tener en cuenta no sólo para la prestación de las intervenciones la curación del cuerpo, sino también para la inclusión de escucha terapéutica y apoyo psicológico en la atención a este grupo.

Enfermería holística; Sexualidad; Enfermedad crónica; Imagen corporal

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Sexual-affective trajectories of people with chronic leg ulcers: aspects of therapeutic listening

Trayectorias afectivo-sexuales de personas con heridas crónicas en las piernas: aspectos en la escucha terapéutica

Evanilda Souza de Santana CarvalhoI; Mirian Santos PaivaII; Elena Casado AparícioIII; Gilmara Ribeiro Santos RodriguesIV

INurse, Doctorate in Nursing, Junior Lecturer at the Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana (UEFS) Feira de Santana - BA, Brasil

IINurse, Doctorate in Nursing, Lecturer at the Escola de Enfermagem da Universidade Federal da Bahia, (EEUFBA) Salvador- BA, Brasil

IIISociologist, Doctorate in Sociology, Lecturer at Universidad Complutense de Madrid (UCM), Madrid, Espanha

IVNurse, Doctorate in Nursing, Researcher at EEUFBA, Salvador- BA, Brasil

Author's address

ABSTRACT

This is a qualitative study that aims to discuss the trajectories of people with chronic sores on the lower limbs, focusing on their affective and sexual experiences. Fifty-one adult outpatients participated and they received care at the infirmary of a public hospital in Salvador - Bahia, between 2008 and 2009. Data was collected through techniques that included themed-story drawings and in-depth interviews, during therapeutic listening sessions, followed by an analysis of the content and an analysis of the drawing contents. Three categories emerged: solitary sexual-affective trajectory, fragmented sexual-affective trajectory, and continuous or linear sexual-affective trajectory. It was concluded that the limitations imposed by sores influence the subjectivity of these people, leading them to processes of loss of self-confidence, self-deprecation and fear of sexual- affective demands. It becomes clear, therefore, for the need to promote, not only curative interventions for the body, but also to include therapeutic listening and psychological support in the assistance offered to these people.

Descriptors: Holistic nursing. Sexuality. Chronic disease. Body image.

RESUMEN

Estudio cualitativo objetivó analizar las trayectorias de personas heridas crónicas en las piernas, enfocándose las experiencias emocionales y sexuales. Participaron 51 adultos, atendidos en un hospital público de Salvador, en Bahia. Los datos fueron recolectados en la escucha terapéutica a través del diseño de la historia-tema y la entrevista en profundidad. A continuación se sometieron al análisis de contenido temático y análisis de contenido para dibujos. Los datos revelaron tres categorías: Las trayectorias solitarias, fragmentadas y lineales o continuas. Se concluye que las limitaciones impuestas por las heridas influyen en la subjetividad de esas personas llevándolas a la pérdida de confianza en sí mismas, autodesprecio y miedo de afrontar las demandas afectivo-sexuales, es necesario tener en cuenta no sólo para la prestación de las intervenciones la curación del cuerpo, sino también para la inclusión de escucha terapéutica y apoyo psicológico en la atención a este grupo.

Descriptores: Enfermería holística. Sexualidad. Enfermedad crónica. Imagen corporal.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic sores on the lower limbs are characterized by lesions on the cutaneous structure - epidermis and dermis but can also affect deeper layers. They tend to remain over a long period of time, not healing or become relapsing sores(1). They are associated with chronic diseases such as high blood pressure, diabetes, sickle-cell anemia and peripheral vascular disease(1).

These sores can change the everyday life of people because they are painful, causing secretions with unpleasant odors, demanding a routine of daily care, wound dressing and periodical visits to healthcare providers(2).

Living with an illness that visibly alters body appearance deepens the demands people have of self-image, influenced by ideas and practices they held about the body before the illness(2).

Among the social pressures and expectations of the body in adult life, representations of what it is to be strong, healthy, beautiful and desirable are found. Often these idealized images oppose the reality of the infirm body, distancing it from current aesthetic standards, and it is understandable how this divergence can lead to prejudice and rejection of one's own body(3,4).

Interpersonal relations and especially affective and sexual relations cannot exclude the body because it is through it that we look at each other, we get close, feel, kiss, caress and give and receive pleasure. The signs of illness stop encounters from taking place not only in an objective manner, through odor, temperature and body mass, but also in a subjective way, through beliefs, images and emotions(2).

Although various situations seek to deny or restrict it, sexuality is generally considered a necessity which cannot be ignored and, in the face of an infirmity, the changes in sexual patterns can express themselves in more or less intense ways (5).

However, during medical consultations, people feel awkward asking questions related to sex and therefore any relevant notes about problems or doubts are rare. They could feel embarrassed talking about it because they believe that it is not an appropriate subject for the health service environment(2).

Therefore sexual restriction has become so widely spread within the health care context that professionals, when dealing with illness, tend to consider patients asexually and/or as disinterested in sex. Even the patients themselves seem to believe that they should abstain from a sex life and in any case this subject is avoided during the visits. When it does come up, the professionals emphasize the restrictive measures(1,6).

In this context,therapeutic listening proves to be an essential tool for the care and approach to people's sexuality. On the other hand, nurses don't seem to have the necessary training to deal with the subjective aspects of the disease, which contributes to the denial of sexuality in the health care sphere(2,6).

Through therapeutic listening, it is possible for patients to express opinions and feelings about themselves, others and the world around them. They can discuss how they see themselves, and how they think and feel in relation to other people who are an important part of their social circle, about their relationships and even about other subjects raised by the professional/ interviewer(7).

As such, it is also possible to know what they think about sex in general, their own sexual experiences and what they hope for in their relationships, what expectations they have in their encounters with others and what mechanisms they use to deal with obstacles in these situations (2,7-8).

In order to contribute to the understanding of the sexual changes taking place in these patients, this study commences with the following question: How do people with chronic sores in the lower limbs cultivate and construct their sexual-affective partnerships?

The aim is to discuss the lives of people with chronic sores on their lower limbs with emphasis on their sexual-affective experiences.

METHODS

This qualitative study took place in the infirmary of a public hospital in Salvador Bahia that provides outpatient care for patients with chronic sores on the lower limbs. It started as a doctorate thesis funded by a scholarship from CAPES(2).

Authorization number 0045/208, was obtained through the Ethics Committee of the UFBA school of nursing. During interviews in the waiting room, the infirmary and during the changing of dressings, the participants were informed about the studies objectives and were asked to take part in it. Those who agreed to take part signed an Informed Consent Agreement.

The data was collected between November 2008 and July 2009, from 51 people with chronic sores on the lower limbs 26 men and 25 women. The criteria for inclusion were: to be an adult between the ages of 18 and 59; to have suffered from sores on the lower limbs for more than a month and to regularly visit the infirmary.

However, people in pain were excluded from the study since this can cause impatience and anxiety and recounting negative and disagreeable experiences could intensify their pain and suffering (9).

The interviewers used themed story drawing(10) and in-depth interview (1) techniques to obtain the data. The interviews took place in a private room of the infirmary to give the participants privacy and so allow them to be more spontaneous when talking about the intimate aspects approached in the study.

No limits were set for the maximum number of participants. It was sought to offer therapeutic listening to all infirmary users who met the criteria for inclusion. So, after observing that all the criteria had been fulfilled, all the patients who showed interest in taking part were interviewed.

In order to protect the identity of the participants, pseudonyms were used. The participants were encouraged to draw something that represented the sexual and affective life of someone with a wound and then after studying it a story was developed and finally they would give it a title. The title given to the interview was: "talk about the sexual and affective life of a person living with a wound."

The projective technique was used to compliment the discursive technique in order to learn about subjective issues of sexuality, which could be omitted during the interview because of the taboos surrounding this subject (2,10).

The data was submitted for content analysis (11) and analysis of the drawing contents(10). These methods for analysis offer a floating reading of the discourses, identification of the core meaning, categorization and inferences (10). The drawing analysis follows the same steps as the themed contents analysis, except that it selects the drawings according to the similarity of graphics, at the categorization stage. It's worth highlighting that the analysis was placed mainly on the contents of the stories and titles, however they gained meaning when read in conjunction with the drawings (10,12).

OUTCOMES AND DISCUSSION

From this analysis three categories have emerged: solitary sexual-affective trajectories, fragmented trajectories, and continuous or linear trajectories.

Solitary sexual-affective trajectories

Sex was referred to as a solitary practice for those whose sores appeared at infancy or during adolescence, resulting in non-existent sexual experience with a partner. Its agreed that when sores appear in young people it interferes with their ability to socialize with their first social group - friends and colleagues at gatherings in public places, such as parties, beaches, clubs and school. Since this is the discovery of the body and intimate relationships phase the appearance of sores complicates the building of partnerships and the initiation of sexual experience.

This kind of trajectory was identified in young adults who highlighted the difficulties in taking the initiative in dating, socializing, keeping up with school, social life, sports and leisure activities. The interruption of social activities at this early age due to chronic illness can damage self-esteem resulting in less confident behavior.

Another study involving 50 people suffering from venous ulcers in Natal (13), identified that 36% of the participants were unhappy with their physical appearance or were feeling discriminated against and 18% reported negative feelings, for not having adapted to the illness and for the presence of the ulcers(13).

To this end, one of the participants reported that when men showed interest in her, her sores made her think that the looks were reproving and not of desire. This way of thinking makes it difficult to approach people of the opposite sex, in anticipation and fear of rejection.

A man, who worked nearby, looked at me and expressed his wish to date me. He inquired about me to a neighbor ... He told my sister about his feelings for me but I didn't believe him, I thought he was reprimanding me for having this problem (ulcers). (Carla, 45 years old, afflicted since 13).

Another study regarding people with sores in Maringa,(14) revealed that because this illness involves questions related to people's appearance, it can affect people's psyche due to the changes which occur in self-image, in affective and emotional life, giving rise to important implications about people's mental health (14).

The confirmation of abandonment by partners is as frequent for men as it is for women and they both agreed that living with chronic sores interferes with relationships, resulting in a solitary affective life style.

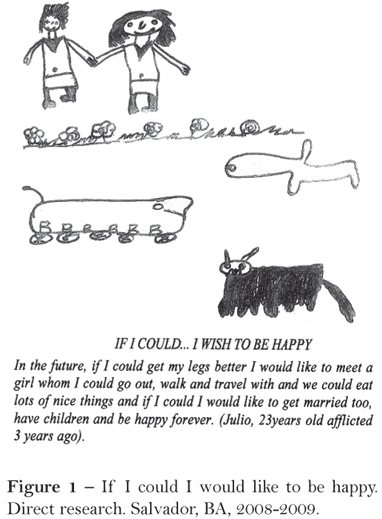

This study reveals that lack of intimacy or separation stemmed from other issues, unrelated to the sores, but people affected will have low self-esteem and so tend to believe that their chronic sores are the reason for the break up or lack of relationships, as shown in Figure 1.

These feelings are the result of self-prejudice as already observed in another study, (15) which revealed that with the belief that their bodies are unable to fulfill social demands, men feel weak and women feel unattractive which leads to reduced confidence in social and affective relationships(15).

Fragmented sexual-affective trajectories

The fragmented sexual-affective trajectory was revealed in the narrations of the participants who developed sores during adult life, when social activities are usually intense: Society demands productivity, social attachments and responsibilities such as leaving home, being independent, getting engaged, getting married and having children. This trajectory fluctuates between frequent breakups and starting new relationships, which are short lived.

This sexual trajectory reveals constant attempts at a relationship followed by break ups and disappointments without loss of hope. The relationships start as any other, with conversation, flirting and persistency but have a break up which is felt by the participants to be unfair, unexpected and traumatic. The reason given by them for the break up is always the revelation of the sores to the partner, which can be seen in figure 2.

This was the most common trajectory for both men and women. It appears to be more regular in younger women's discourse than men's, who see the constant partner change as normal. For women, who are culturally identified with the belief in fidelity and long lasting relationships, to seek new partners gives a negative connotation about a woman's sexual behavior (2).

It was observed that women, who suffer abandonment and rejection, fear and resist new relationships in order to protect themselves from prejudice, discrimination and violence. These fears are reinforced by stories told by other women with sores who were badly treated and abandoned by their partners.

As stories about abandonment and rejection are spread throughout the infirmary, the patterns and images are commonly added into the old drawings, seeking to give them significance. It's clear that the details of the lives of people with sores is spread, how they're treated by their partners and other people, creating an image which does not often portray their personal experience but rather a group experience. It eventually influences the way each one of them behaves in the face of external stimuli, as shown in the following.

I have met a woman here, in the infirmary, she used to come and cry about her husband leaving her because of her "problem"...She was this and that... And all this created confusion in my mind. I was worried and I didn't like people staring at me, so I would move away" ( so she paused thoughtfully) "I don't know if I will get hurt by anyone because of this problem. I could never accept that, never! (Carina, 42 years old, afflicted 5 years ago)

Based on other people's negative experiences, the patients create images that influence their affective and sexual behavior, limiting their opportunities with new partners.

Patients commonly say that they don't feel attracted to their partners due to the physical changes caused by the chronic illness(16).

Similarly, as seen in this study, interviewers listened to people with venous ulcers claiming that they had broken their marital vows due to their wish to reduce their sexual relations because they felt ashamed showing an ulcer(13).

A study in São Paulo of thirty people with chronic sores identified that 68.2% of them considered sexual intercourse important, however 63.6% claimed to have reduced their sexual activity after they developed the sores(17).

Women especially seem to develop a great fear of rejection due to body changes, as with women with mastectomies, who reflect how the suffering goes beyond the illness itself. And as it is with cancer, chronic sores are associated with negative attributes historically constructed with images and meanings, which interfere with interpersonal relationships(18).

I didn't see myself as normal like all the other girls at my age, I'm young. So, I believe that if he finds out that I have this sore, he will leave me. He will not want to be with me because I am like this, (she pauses and cries). I been living with this sore since I was sixteen. It is too much to bear, ( she cries even more). (Vitoria, 22 year old, afflicted 5 years ago).

Women claim that men usually leave them when they become afflicted similar to results found in a study about the sexuality of women suffering with urinary incontinence (19). This is a result of the negative assessment the women make of themselves. They see themselves as not very attractive, feel less motivated to engage in sex, refusing to have sexual relations with their partners. This can generate conflict, violence and the breakup of the relationship.

In the face of chronic illness, a woman expects to have a relationship based on friendship, affection, understanding and companionship with their partner rather than a sexual one. Lack of support from a companion during the period of illness, exactly when she needs more acceptance, understanding and kindness, is conceived as strongly aggressive to the woman, affecting her self-esteem(2,19).

Continuous or linear sexual-affective trajectory

People who had sexual experience before developing the sore have shown a greater degree of hope. Since they were afflicted more recently, they believe that they will find a cure, therefore they move on with their lives, getting out more, seeking new relationships and finding arguments to make other people understand that the sore wouldn't be in their lives for long.

The continuous or linear sexual-affective trajectory was identified when the participants described stories with links prior to the development of the sore; their stories tell us that the sexual relationships were well established before the appearance of the lesions.

These trajectories highlight changes in the affective and sexual behavior with alterations in the dynamic of sexual encounters, in the frequency and intensity of them, while, however, maintaining the relationship.

In this trajectory, the partners act as care givers and sexual relations are reduced. This is understood as a loss of interest by the partner, motivated by repulsion, by pity or by worry, zeal and caring. This type of discourse was especially centered on men's stories with a fixed partner, as is shown in figure 3:

The finds show that the trajectories narrated by men are less bound to other people. They refer more to old relationships to express the beginning of their trajectories, such as childhood friends and parents and relatives are less frequently mentioned. The family does come up when intentionally questioned about them in scenes of conflict and misunderstanding, which were seen to worsen with the onset of the ailment.

However, in the women's discourse, the family, especially the children come up spontaneously and seem to represent the main source of pleasure, hope and emotional support, providing them with a meaning and helping them to carry on living despite the adversities.

During the discourse regarding future relationships, the men place themselves as main players deciding when to meet up with other people. On the other hand the women show themselves as passive spectators to the male's initiative.

In this sense, focusing on the question of gender, the males' decisions are autonomous, while the females seem to share things with members of their close circle of friends and family, who are consulted about decisions to accept or not accept a date with the opposite sex. To sum it up, females make decisions in a group and through dialogue, while a male's decision-making is normally independent and solitary. Below a participant describes how she would start a new relationship:

I didn't want to accept it, not at all. But he was very pushy trying to persuade me, I talked to some people and they said that I should check him out, it might be worth my while and if I didn't try I would never know! My daughters and friends gave me support. I didn't want to get involved and I wouldn't have if it wasn't for them, (pause), I was ashamed! (Carina, 42 years old, afflicted 5 years ago).

Among the men who preserve their autonomy and believed that pain doesn't make you incapable, it was observed that if their steady partner denied sexual relations, they would begin to have sexual relations outside their marriage with other partners, interspersing sexual contact according to the crises of the first marriage.

I sought her again, but she didn't want to have sexual relations with me, she yelled: let me sleep! So, we ... I moved away. We sleep together but I never sought her again because the last two times I did she treated me badly. So I have other ladies on the side and life carries on... (Roberto 60 years old, afflicted 3 years ago).

Men also refer to the services of sex workers to help them with their difficulties establishing new intimate contacts. These results are strengthened by the findings of another study,(20) which shows that to seek a solution to their sexual problems from "other women" is a solution for men with chronic illness, enabling them to maintain their image as sexually active men a key image in the model of virility for Brazilian men(20).

This a model which is expressed by strength, aggression and determination and it requires performance from active men, both at work and as a family provider, in a sexual context, in and outside the home, requiring men to establish how they position themselves with regards to women and other men(2).

To this end, questions on gender must be considered carefully, because to contemplate the complexity of the individuals, it's necessary to have flexibility and creativity in dealing with the subjectivity that permeates the process of illness(20).

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

This study highlights how chronic sores can limit the body by affecting the subjectivity of people, taking them through processes of loss of self-confidence, self-hatred and strong fear of experiencing rejection and the impossibility of having sexual-affective experiences.

People build up different sexual affective trajectories. It depends on their age and the time of the affliction because these can interfere with the support given, which is based on their own social expectations found in every stage of development of the human race.

To be involved with someone sexually means to position oneself as an object of desire to the other. To hold this position of being appreciated and beloved helps to increase self-esteem and improves the way people affected by this illness see themselves.

Having chronic sores and still seeking the ideal body to match expectations, emphasizes feelings of inadequacy. It is found markedly more in women and young people who lack experience with sexual relationships. The sore is an obstacle to creating sexual- affective ties as well as preserving the ones that already exist.

While there are curative measures for an ill body, which increase expectations of a cure, often many are not cured and this increases feelings of inadequacy and frustration for the patients in care. Therefore this study suggests the need to include therapeutic listening and psychological emotional support for this specific group.

To this end, the sexual aspects of people with sores must be considered during their visits with nursing professionals so they can be helped to break down the negative ideas about their own body and sex, and build up alternative approaches to sexual relations.

There are very few studies about the sexuality of people with chronic illness to compare the finds of this study with, so I recommend that new studies should take place to gain a deeper understanding of the aspects observed here, regarding the sexuality of this group.

REFERENCES

- 1 Lucas LS, Martins JT, Robazzi MLCC. Qualidade de vida dos portadores de ferida em membros inferiores: úlcera de perna. Ciênc Enferm. 2008;14(1):43-52.

- 2 Carvalho ESS. Viver a sexualidade com o corpo ferido: representações de mulheres e homens [tese]. Salvador (BA): Escola de Enfermagem, Universidade Federal da Bahia; 2010.

- 3 Le Breton D. A sociologia do corpo. 4Şed. Rio de Janeiro: Vozes; 2010.

- 4 Goffman E. A representação do eu na vida cotidiana. Petrópolis: Vozes; 1983.

- 5 Vasconcellos D, Novo RF, Castro OP, Vion-Dury K, Ruschel A, Couto MCPP, et al. A sexualidade no processo de envelhecimento: novas perspectivas - comparação transcultural. Estud.psicol. 2004:9(3):413-19.

- 6 Ressel LB, Gualda DMR. A sexualidade invisível ou oculta na enfermagem? Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2002;36(1):75-9.

- 7 Benjamin A. A entrevista de ajuda. São Paulo: Martins Fontes; 2011.

- 8 Souza RC, Pereira MA, Kantorski LP. Escuta terapêutica: instrumento essencial do cuidado de enfermagem. Rev Enferm UERJ. 2003;11(1):92-7.

- 9 Price PE, Fagervik-Morton H, Mudge EJ, Beele H, Ruiz JC, Nystrom TH, et al. Dressing-related pain in patients with chronic wounds: an international patient perspective. Int Wound J. 2008;5(2):159-71.

- 10 Coutinho MPL. Saraiva ERA, organizadoras. Métodos de pesquisa em psicologia social: perspectivas qualitativas e quantitativas. João Pessoa: UFPB/Editora Universitária; 2011.

- 11 Bardin L. Analise de conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70; 2011.

- 12 Rivemales MCC, Rodrigues GRS, Paiva MS. Graphic projective techniques: applicability on social representation research-systematic review. Online Braz J Nurs [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2013 Apr 04];9(2). Available from: http://www.objnursing.uff.br/index.php/nursing/article/view/3153

- 13 Costa IKF, Nóbrega WG, Costa IKF, Torres GV, Lira ALBC, Tourinho FSV, et al. Pessoas com úlceras venosas: estudo do modo psicossocial do Modelo Adaptativo de Roy. Rev Gaúcha Enferm. 2011;32(3):561-8.

- 14 Waidman MAP, Rocha SC, Correa JL, Brischiliari A, Marcos SS.O cotidiano do indivíduo com ferida crônica e sua saúde mental. Texto & Contexto Enferm.2011;20(4):85-91.

- 15 Carvalho ESS, Paiva MS, Aparício EC. Cuerpos heridos, vida alterada: representaciones sociales de mujeres y hombres. Index Enferm. 2011;20(1-2):31-5.

- 16 Melo AS, Carvalho EC, Pelá NTR. A sexualidade do paciente portador de doenças onco-hematológicas. Rev Latinoam Enferm. 2006;14(2):227-32.

- 17 Salomé GM. Processo de viver do portador com ferida crônica: atividades recreativas, sexuais, vida social e familiar. Saúde Coletiva.2010;7(46):300-04.

- 18 Silva LC. Câncer de mama e sofrimento psicológico: aspectos relacionados ao feminino. Psicol Estud. 2008;13(2):231-37.

- 19 Paranhos RFB. Vivenciando a sexualidade e a incontinencia urinária: histórias de mulheres HTLV positivas [dissertação]. Salvador (BA): Escola de Enfermagem, Universidade Federal da Bahia; 2011.

- 20 Oliveira MHP, Romanelli G. Os efeitos da hanseníase em homens e mulheres: um estudo de gênero. Cad Saúde Pública. 1998;14(1):51-60.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

02 Dec 2013 -

Date of issue

Sept 2013

History

-

Received

30 Apr 2013 -

Accepted

12 Sept 2013