Abstracts

Canine ehrlichiosis and babesiosis are the most prevalent tick-borne diseases in Brazilian dogs. Few studies have focused attention in surveying tick-borne diseases in the Brazilian Amazon region. A total of 129 blood samples were collected from dogs living in the Brazilian eastern Amazon. Seventy-two samples from dogs from rural areas of 19 municipalities and 57 samples from urban stray dogs from Santarém municipality were collected. Serum samples were submitted to Indirect Immunofluorescence Assay (IFA) with antigens ofBabesia canis vogeli, Ehrlichia canis, and six Rickettsia species. The frequency of dogs containing anti-B. canis vogeli, anti-E. canis, and anti-Rickettsia spp. antibodies was 42.6%, 16.2%, and 31.7%, respectively. Anti-B. canis vogeli antibodies were detected in 59.6% of the urban dogs, and in 29.1% of the rural dogs (P < 0.05). For E. canis, seroprevalence was similar among urban (15.7%) and rural (16.6%) dogs. ForRickettsia spp., rural dogs presented significantly higher (P < 0.05) prevalence (40.3%) than urban animals (21.1%). This first study on tick-borne pathogens in dogs from the Brazilian eastern Amazon indicates that dogs are exposed to several agents, such asBabesia organisms, mostly in the urban area; Spotted Fever group Rickettsia organisms, mostly in the rural area; andEhrlichia organisms, in dogs from both areas studied.

Ehrlichia; Babesia; Rickettsia; dogs; Amazon; Pará state

Ehrliquiose canina e babesiose canina são as doenças parasitárias transmitidas por carrapatos de maior prevalência em cães do Brasil. Poucos estudos pesquisaram doenças transmitidas por carrapatos na região da Amazônia brasileira. Um total de 129 amostras de sangue foram colhidas de cães da Amazônia oriental brasileira. Setenta e dois cães eram de áreas rurais de 19 municípios do Estado do Pará, e 57 amostras foram colhidas de cães errantes vadios da área urbana do município de Santarém-PA. As amostras de soro foram submetidas ao ensaio de imunofluorescência indireta, com antígenos deBabesia canis vogeli, Ehrlichia canis, e seis espécies de Rickettsia. A frequência de cães com anticorpos anti-B. canis vogeli, anti-E. canis, e anti-Rickettsia spp. foi de 42,6%, 16,2% e 31,7%, respectivamente. Anticorpos anti-B. canis vogeli foram detectados em 59,6% dos cães urbanos, e em 29,1% dos cães rurais (P < 0.05). Para E. canis, a soroprevalência foi parecida entre os cães urbanos (15,7%) e rurais (16,6%). Para Rickettsia spp., cães rurais apresentaram prevalência (P < 0.05) significativamente maior (40,3%) do que os cães urbanos (21,1%). Esse primeiro estudo sobre agentes transmitidos por carrapatos entre cães da Amazônia oriental brasileira indica que estes animais estão expostos a vários agentes. Estes incluem Babesia principalmente na área urbana, Riquétsias do grupo da Febre Maculosa principalmente nas áreas rurais, e Erliquia em cães de ambas as áreas, rural e urbana.

Ehrlichia; Babesia; Rickettsia; cães; Amazônia; Pará

Introduction

Tick-borne diseases have been increasingly studied in Brazil, but there are still many unexplored places, especially in the Amazon region. Canine babesiosis is a tick-borne disease of domestic and wild canids characterized by fever, depression, and anaemia (KUTTLER, 1988Kuttler KL. Worldwide impact of babesiosis. In: Ristic M. Babesiosis of Domestic Animals and Man. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1988. 1-22.). Previous parasitological and serological studies carried out in Brazil have shown that canine babesiosis due to Babesia canis is distributed among different states with rates of seropositivity ranging from 1.9 to 66.9% in Minas Gerais (RIBEIRO et al., 1990Ribeiro MFB, Passos LMF, Lima JD, Guimarães AM. Frequency of anti-Babesia canis antibodies in dogs, in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec 1990; 42(6):511-517.; RODRIGUES et al., 2002Rodrigues AFSF, D'Agosto M, Daemon E. Babesia canis (Piana & Galli-Valerio, 1895) (Apicomplexa: Babesiidae) em cães de rua do Município de Juiz de Fora, MG. Rev Bras Med Vet 2002; 24(1): 17-21.; BASTOS et al., 2004Bastos CV, Moreira SM, Passos LM. Retrospective study (1998-2001) on canine babesiosis in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2004; 1026: 158-160. PMid:15604486. http://dx.doi.org/10.1196/annals.1307.023

http://dx.doi.org/10.1196/annals.1307.02...

; SOARES et al., 2006Soares AO, Souza AD, Feliciano EA, Rodrigues AF, D'Agosto M, Daemon E. Avaliação ectoparasitológica e hemoparasitológica em cães criados em apartamentos e casas com quintal na cidade de Juiz de Fora, MG. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2006; 15(1): 13-16. PMid:16646996.), 35.7% in Paraná (TRAPP et al., 2006Trapp SM, Dagnone AS, Vidotto O, Freire RL, Amude AM, Morais HS. Seroepidemiology of canine babesiosis and ehrlichiosis in a hospital population. Vet Parasitol 2006; 140(3-4): 223-230. PMid:16647817. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.03.030

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006....

), 5.2% in Rio de Janeiro (O'DWYER et al., 2001O'Dwyer LH, Massard CL, Pereira de Souza JCP. Hepatozoon canis infection associated with dog ticks of rural areas of Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil. Vet Parasitol 2001; 94(3): 143-150. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(00)00378-2

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(00)...

), and 10.3% in São Paulo (DELL'PORTO et al., 1993Dell'Porto A, Oliveira MR, Miguel O. Babesia canis in stray dogs from the city of São Paulo Comparative studies between the clinical and hematological aspects and the indirect fluorescence antibody test. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 1993; 2(1): 37-40.). In addition, the disease was also reported in the state of Mato Grosso, where it was molecularly confirmed asB. canis vogeli (SPOLIDORIO et al., 2011Spolidorio MG, Torres MM, Campos WNS, Melo ALT, Igarashi M, Amude AM, et al. Molecular detection of Hepatozoon canis and Babesia canis vogeli in domestic dogs from Cuiabá, Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2011; 20(3): 253-255. PMid:21961759. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612011000300015

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612011...

).

Canine monocytic ehrlichiosis, caused by Ehrlichia canis, is the most important tick-borne disease of dogs in Brazil. Currently,Ehrlichia canis is the only Ehrlichia species that has been isolated in cell culture from vertebrates in South America. A preliminary investigation for Ehrlichia species in the northern and southeastern regions of Brazil failed to detect Ehrlichia DNA inAmblyomma ticks, humans, dogs, capybaras, and febrile human blood samples (LABRUNA et al., 2007aLabruna MB, McBride JW, Camargo LM, Aguiar DM, Yabsley MJ, Davidson WR, et al. A preliminary investigation of Ehrlichia species in ticks, humans, dogs, and capybaras from Brazil. Vet Parasitol 2007a; 143(2): 189-195. PMid:16962245. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.08.005

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006....

). In contrast, ehrlichial DNA compatible with Ehrlichia chaffeensis,Ehrlichia ewingii, or an agent closely related toEhrlichia ruminantium were recently reported in animal blood samples from southeastern Brazil (MACHADO et al., 2006Machado RZ, Duarte JM, Dagnone AS, Szabó MP. Detection of Ehrlichia chaffeensis in Brazilian marsh deer (Blastocerus dichotomus). Vet Parasitol 2006; 139(1-3): 262-266. PMid:16621285. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.02.038

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006....

; OLIVEIRA et al., 2009Oliveira LS, Oliveira KA, Mourão LC, Pescatore AM, Almeida MR, Conceição LG, et al. First report of Ehrlichia ewingii detected by molecular investigation in dogs from Brazil. Clin Microbiol Infect 2009; 15(S2): 55-56. PMid:19416280. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02635.x

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.20...

; WIDMER et al., 2011Widmer CE, Azevedo FC, Almeida AP, Ferreira F, Labruna MB. Tickborne bacteria in free living jaguars (Panthera onca) in Pantanal, Brazil. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2011; 11(8): 1001-1005. PMid:21612532. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2011.0619

http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2011.0619...

).

Most of the published studies on tick-borne diseases in the Brazilian Amazon region have focused on rickettsiosis, mainly in western Amazon, state of Rondônia (LABRUNA et al., 2004Labruna MB, Whitworth T, Bouyer DH, McBride J, Camargo LM, Camargo EP, et al. Rickettsia bellii and Rickettsia amblyommii in Amblyomma ticks from the State of Rondônia, Western Amazon, Brazil. J Med Entomol 2004; 41(6): 1073-1081. PMid:15605647. http://dx.doi.org/10.1603/0022-2585-41.6.1073

http://dx.doi.org/10.1603/0022-2585-41.6...

, 2007bLabruna MB, Horta MC, Aguiar DM, Cavalcante GT, Pinter A, Gennari SM, et al. Prevalence of Rickettsia infection in dogs from the urban and rural areas of Monte Negro municipality, western Amazon, Brazil. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2007b; 7(2): 249-255. PMid:17627445. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2006.0621

http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2006.0621...

). In the aforementioned region, someRickettsia species were described for the first time in Brazil. At the same time, there is no information on rickettsioses from the eastern part of the Amazon.

In this study, we evaluated seroprevalence to Babesia canis vogeli, Ehrlichia canis, andRickettsia spp. in dogs from rural and urban areas within the state of Pará, eastern Amazon, Brazil.

Materials and Methods

During 2008-2009, a total of 129 dogs of different breeds and ages were sampled from an urban area and from different farms in rural areas. Those samples were also used for a serological study to investigate the prevalence ofNeospora caninum, Toxoplasma gondii, andLeishmania infantum (formerly chagasi), as previously described (VALADAS et al., 2010Valadas S, Minervino AHH, Lima VMF, Soares RM, Ortolani EL, Gennari SM. Occurrence of antibodies anti-Neospora caninum, anti-Toxoplasma gondii, and anti-Leishmania chagasi in serum of dogs from Pará State, Amazon, Brazil. Parasitol Res 2010; 107(2): 453-457. PMid:20445991. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-010-1890-2

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-010-189...

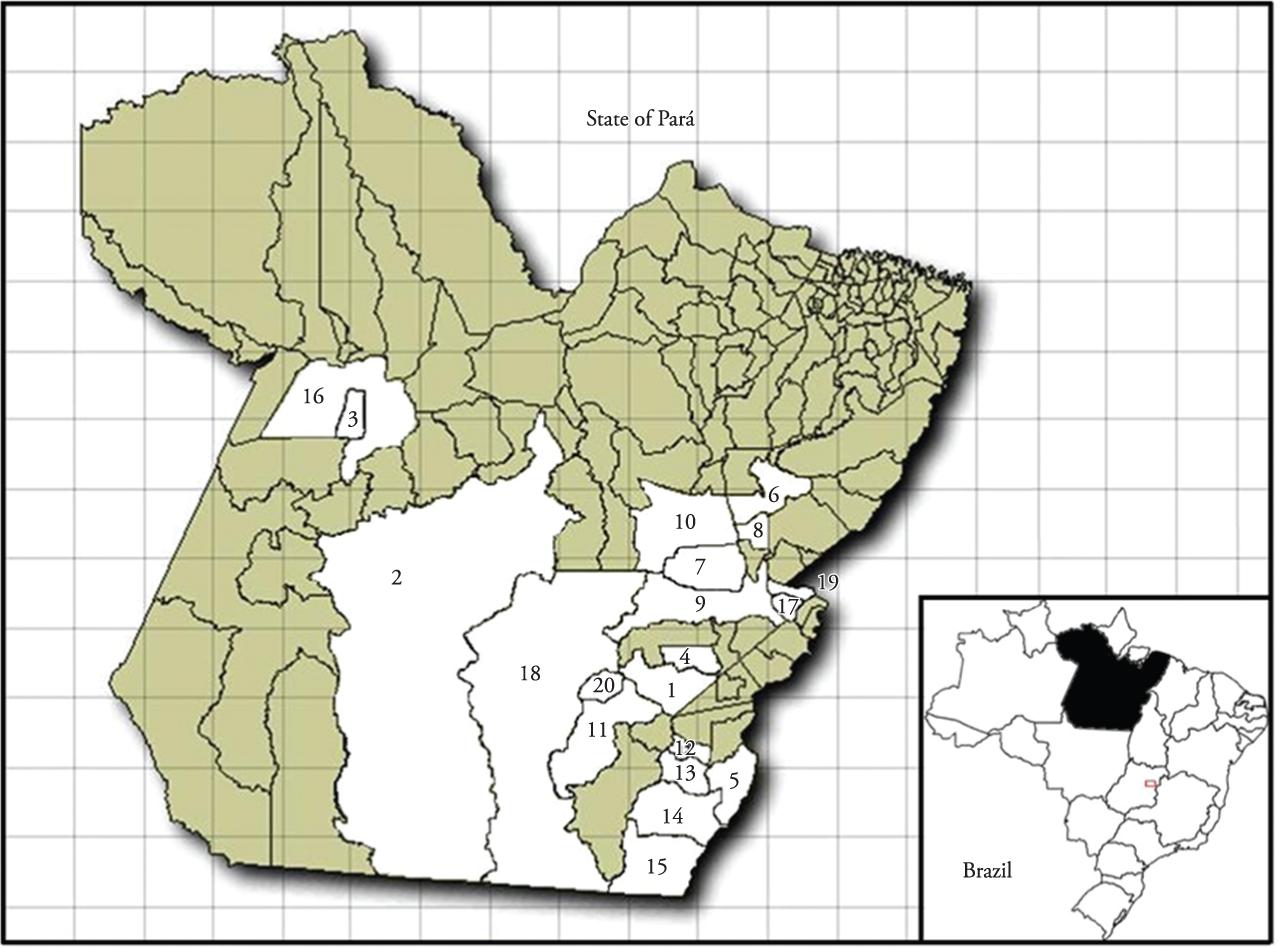

). Of all the dogs, 77 (59.7%) were males and 52 (40.3%) were females; 57 samples (44.2%) were collected from urban stray dogs from the municipality of Santarém, and 72 (55.8%) were from dogs from 39 rural properties in 20 different municipalities.Figure 1 shows the municipalities where the respective numbers of dogs were sampled. The rural properties were selected from a prevalence study of other parasitic and infection agents in cattle (MINERVINO et al., 2008Minervino AH, Ragozo AM, Monteiro RM, Ortolani EL, Gennari SM. Prevalence of Neospora caninum antibodies in cattle from Santarém, Pará, Brazil. Res Vet Sci 2008; 84(2): 254-256. PMid:17619028. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2007.05.003

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2007.05...

; CHIEBAO, 2010Chiebao DP. Frequência de anticorpos anti-Neospora caninum, anti-Brucella abortus e anti-Lesptospira spp. em bovinos do Estado do Pará: estudo de possíveis variáveis para ocorrência de infecção [Dissertação]. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo; 2010.). Blood samples were collected from the jugular or brachial vein of the dogs, and sera was obtained by centrifugation. Samples were stored at −20 °C until tested.

Map of Pará state with the municipalities where canine serum samples were collected (number of dogs). 1 Água Azul do Norte (one); 2 Altamira (six); 3 Belterra (one); 4 Canaã dos Carajás (one); 5Conceição do Araguaia (11); 6 Goianésia do Pará (two);7 Itupiranga (six); 8 Jacundá (eight); 9 Marabá (four); 10 Novo Repartimento (two); 11 Ourilândia do Norte (two);12 Pau D'Arco (two); 13 Redenção (four); 14 Santa Maria das Barreiras (two);15 Santana do Araguaia (six); 16Santarém (three rural, 57 urban); 17 São Domingos do Araguaia (two); 18 São Felix do Xingu (two);19 São João do Araguaia (1); 20Tucumã (six).

Serum samples were submitted to indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) with antigens of B. canis vogeli (blood smears from splenectomized dogs that were experimentally infected in our lab) according to Bicalho et al. (2004)Bicalho KA, Ribeiro MF, Martins-Filho OA. Molecular fluorescent approach to assessing intraerythrocytic hemaprotozoan Babesia canis infection in dogs. Vet Parasitol 2004; 125(3-4): 221-235. PMid:15482880. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.08.009

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004....

, using a screening dilution of 1:64. To detect antibodies against E. canis, the bacteria were cultivated in DH82 cells, as described by Aguiar et al. (2007a)Aguiar DM, Saito TB, Hagiwara MK, Machado RZ, Labruna MB. Diagnóstico sorológico de erliquiose canina com antígeno brasileiro de Ehrlichia canis. Cienc Rural 2007a; 37(3): 796-802. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-84782007000300030

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-84782007...

, and serum samples were analyzed following the protocol by Silva et al. (2010)Silva JN, Almeida ABPF, Boa Sorte EC, Freitas AG, Santos LGF, Aguiar DM, et al. Seroprevalence anti-Ehrlichia canis antibodies in dogs of Cuiabá, Mato Grosso. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2010; 19(2): 108-111. PMid:20624348.http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbpv.01902008

http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbpv.01902008...

, but with a screening dilution of 1:80. ForRickettsia spp., IFA was run using the screening dilution of 1:64 against six Rickettsia species that occur in Brazil, namelyR. rickettsii, R. parkeri, R. amblyommii, R. rhipicephali, R. bellii, and R. felis, which were cultivated in Vero or C6/36 cells (LABRUNA et al., 2007bLabruna MB, Horta MC, Aguiar DM, Cavalcante GT, Pinter A, Gennari SM, et al. Prevalence of Rickettsia infection in dogs from the urban and rural areas of Monte Negro municipality, western Amazon, Brazil. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2007b; 7(2): 249-255. PMid:17627445. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2006.0621

http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2006.0621...

; HORTA et al., 2004Horta MC, Labruna MB, Sangioni LA, Vianna MCB, Gennari SM, Galvão MAM, et al. Prevalence of antibodies to Spotted Fever Group Rickettsiae in humans and domestic animals in a Brazilian Spotted Fever-Endemic area in the State of São Paulo, Brazil: Serologic evidence for infection by Rickettsia rickettsii and another spotted fever group Rickettsia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2004; 71(1): 93-97. PMid:15238696.). Samples with IFA reaction at the cut-off point for each agent were considered positive and further tested in two-fold serial dilution to determine endpoint titers. Serum of aRickettsia species showing titer at least 4-fold higher than those observed for the other Rickettsia species was considered homologous to the first Rickettsia species or to a very closely related species (HORTA et al., 2004Horta MC, Labruna MB, Sangioni LA, Vianna MCB, Gennari SM, Galvão MAM, et al. Prevalence of antibodies to Spotted Fever Group Rickettsiae in humans and domestic animals in a Brazilian Spotted Fever-Endemic area in the State of São Paulo, Brazil: Serologic evidence for infection by Rickettsia rickettsii and another spotted fever group Rickettsia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2004; 71(1): 93-97. PMid:15238696., 2010Horta MC, Sabatini GS, Moraes-Filho J, Ogrzewalska M, Canal RB, Pacheco RC, et al. Experimental Infection of the Opossum Didelphis aurita by Rickettsia felis, Rickettsia bellii and Rickettsia parkeri and Evaluation of the Transmission of the Infection to Ticks Amblyomma cajennense and Amblyomma dubitatum. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2010; 10(10): 959-967. PMid:20455783.http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2009.0149

http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2009.0149...

; LABRUNA et al., 2007bLabruna MB, Horta MC, Aguiar DM, Cavalcante GT, Pinter A, Gennari SM, et al. Prevalence of Rickettsia infection in dogs from the urban and rural areas of Monte Negro municipality, western Amazon, Brazil. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2007b; 7(2): 249-255. PMid:17627445. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2006.0621

http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2006.0621...

; PIRANDA et al., 2008Piranda EM, Faccini JL, Pinter A, Saito TB, Pacheco RC, Hagiwara MK, et al. Experimental infection of dogs with a Brazilian strain of Rickettsia rickettsii: clinical and laboratory findings. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2008; 103(7): 696-701. PMid:19057821. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02762008000700012

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02762008...

; SAITO et al., 2008Saito TB, Cunha-Filho NA, Pacheco RC, Ferreira F, Pappen FG, Farias NA, et al. Canine infection by rickettsiae and ehrlichiae in southern Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2008; 79(1): 102-108. PMid:18606772.).

Possible statistical associations between gender or location (rural or urban) of dogs and the occurrence of anti- B. canis vogeli,E. canis, or any of the six Rickettsia species antibodies were analyzed by Pearson's chi-square test using Minitab statistical software (Minitab 2000). The significance adopted was 5%.

Results

The distance between the visited farms varied from 10 to 1,000 km. From the 20 municipalities visited, only three (Canaã dos Carajás, Ourilândia do Norte, and São João do Araguaia) presented negative results to all tested samples. From the 129 samples tested for B. canis vogeli, 55 (42.6%) were positive, being 34 (59.6%) from urban dogs and 21 (29.1%) from rural dogs. Antibodies againstB. canis vogeli were detected in dogs from 10 different municipalities (Conceição do Araguaia, Itupiranga, Jacundá, Marabá, Redenção, Santa Maria das Barreiras, Santana do Araguaia, Santarém, São Felix do Xingu, and Tucumã).

From the tested samples (129), 21 (16.2%) were positive to E. canis, being 9 (15.7%) from urban dogs and 12 (16.6%) from rural dogs from eight different municipalities (Água Azul do Norte, Altamira, Belterra, Conceição do Araguaia, Jacundá, Pau D'Arco, Redenção, and Santana do Araguaia). The highest anti-E. canis endpoint titer found in dogs from either rural or urban areas was 81,720.

Sera from 41 (31.7%) out of 129 canine samples were positive to at least one Rickettsia species, being 29 (24.8%) rural dogs from 13 different municipalities (Conceição do Araguaia, Itupiranga, Jacundá, Marabá, Novo Repartimento, Pau D'Arco, Redenção, Santa Maria das Barreiras, Santana do Araguaia, Santarém, São Felix do Xingu, São Domingos do Araguaia, and Tucumã) and 12 (21%) urban stray dogs from Santarém municipality. From the sixRickettsia species tested, only four were considered to be possibly present at the studied regions (R. bellii in at least eight dogs, R. rhipicephali in two dogs, R. rickettsii in one dog, and R. amblyommii in eight dogs). Canine endpoint titers to Rickettsia spp. antigens are presented in Table 1. A total of 30, 20, 15, 12, 11, and nine dogs were reactive to R. amblyommii, R. rhipicephali, R. parkeri, R. bellii,R. rickettsii, and R. felis, respectively. Endpoint titers varied from 64 to 8,192 for R. amblyommii. At least half of the 30 R. amblyommii-seroreactive dogs had endpoint titers ≥1024 for R. amblyommii. Endpoint titers for the otherRickettsia species ranged as follows: R. rhipicephali, 64-8,192; R. bellii, 128-8,192;R. parkeri, 128-2,148; R. rickettsii, 64-2,148; and R. felis, 64-512. While the median of the individual titers against both R. amblyommii and R. rhipicephali was 1,024, the median for the titers against R. bellii, R. parkeri, R. rickettsii, and R. felis were 512, 256, 128, and 256, respectively.

Regarding B. canis vogeli, female dogs presented significantly higher prevalence (53.8%) than male dogs (35.1%) (P = 0.046). In addition, B. canis vogeli seropositivity was significantly higher (P < 0.01) among urban (59.7%) than rural (29.2%) dogs. For E. canis, there was no association between the frequency of positive animals and the independent variables evaluated (P > 0.05). For Rickettsia spp., no association (P >0.05) was found relating to gender, but rural dogs presented significantly higher prevalence (40.3%) than urban animals (21.1%) (P = 0.02).

Antibodies for the three genera of tick-borne pathogens were not found simultaneously in any of the dogs. Antibodies for at least two genera were found in 16 (22.2%) dogs from the rural area, with highest association between E. canis and Rickettsia spp. (56.2%). In the urban area, there were 17 (29.8%) animals with positive results to at least two genera, whereE. canis and Rickettsia spp. (58.8%) were again the most prevalent. However, no statistically significant correlation was found in positivity for the different pathogens.

Discussion and Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, Babesia species in dogs from the Amazon region has never been reported. Due to this lack of information about canine babesiosis in the Brazilian Amazon region, the occurrence of positive dogs to B. canis vogeli (42.6%) can only be compared to other Brazilian studies, in which the prevalence of antibodies against this parasite in sera from dogs varied from 35.7% in Paraná state (TRAPP et al., 2006Trapp SM, Dagnone AS, Vidotto O, Freire RL, Amude AM, Morais HS. Seroepidemiology of canine babesiosis and ehrlichiosis in a hospital population. Vet Parasitol 2006; 140(3-4): 223-230. PMid:16647817. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.03.030

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006....

) to 66.9% in Minas Gerais state (RIBEIRO et al., 1990Ribeiro MFB, Passos LMF, Lima JD, Guimarães AM. Frequency of anti-Babesia canis antibodies in dogs, in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec 1990; 42(6):511-517.). We can infer from our results that the higher seroprevalence to B. canis vogeli observed among urban dogs is probably due to the predominating tick species recently found in the urban area of the municipality of Santarém, namely, R. sanguineus (SERRA-FREIRE, 2010Serra-Freire NM. Occurrence of ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) on human hosts, in three municipalities in the State of Pará, Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2010; 19(3): 141-147. PMid:20943016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612010000300003

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612010...

), which is the only known vector of B. canis vogeli (DANTAS-TORRES, 2008Dantas-Torres F. Causative agents of canine babesiosis in Brazil. Prev Vet Med 2008; 83(2): 210-211. PMid:17980446. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2007.03.008

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.20...

).

Ehrlichia was first reported in Brazil in 1973, in dogs from Minas Gerais state, southeastern Brazil (COSTA et al., 1973Costa JO, Batista Júnior JA, Silva M, Guimarães PM. Ehrlichia canis infection in dog in Belo Horizonte - Brazil. Arq Esc Vet UFMG 1973; 25(2): 199-206.). From the 26 Brazilian states, only one remains with no report onEhrlichia species, as recently reviewed or reported (SPOLIDORIO et al., 2010Spolidorio MG, Labruna MB, Machado RZ, Moraes-Filho J, Zago AM, Donatele DM, et al. Survey for tick-borne zoonoses in the state of Espírito Santo, southeastern Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2010; 83(1): 201-206. PMid:20595502 PMCid:2912600. http://dx.doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0595

http://dx.doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-...

; AZEVEDO et al., 2011Azevedo SS, Aguiar DM, Aquino SF, Orlandelli RC; Fernandes ARF, Uchôa ICP. Soroprevalência e fatores de risco associados á soropositividade para Ehrlichia canis em cães do semiárido da Paraíba. Braz J Vet Res Anim Sci 2011; 48(1): 14-18.; VIEIRA et al., 2011Vieira RF, Biondo AW, Guimarães AM, Dos Santos AP, Dos Santos RP, Dutra LH, et al. Ehrlichiosis in Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2011; 20(1): 1-12. PMid:21439224. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612011000100002

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612011...

). Considering the Legal Amazon region, the only reports onEhrlichia species are from Rondônia state (western Amazon), where 36% of dogs were seroreactive to E. canis by IFA (AGUIAR et al., 2007bAguiar DM, Cavalcante GT, Pinter A, Gennari SM, Camargo LM, Labruna MB. Prevalence of Ehrlichia canis (Rickettsiales: Anaplasmataceae) in dogs and Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Acari: Ixodidae) ticks from Brazil. J Med Entomol 2007b; 44(1): 126-132. http://dx.doi.org/10.1603/0022-2585(2007)44[126:POECRA]2.0.CO;2

http://dx.doi.org/10.1603/0022-2585(2007...

; VIEIRA et al., 2011Vieira RF, Biondo AW, Guimarães AM, Dos Santos AP, Dos Santos RP, Dutra LH, et al. Ehrlichiosis in Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2011; 20(1): 1-12. PMid:21439224. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612011000100002

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612011...

). Also in Rondônia state, Labruna et al. (2007a)Labruna MB, McBride JW, Camargo LM, Aguiar DM, Yabsley MJ, Davidson WR, et al. A preliminary investigation of Ehrlichia species in ticks, humans, dogs, and capybaras from Brazil. Vet Parasitol 2007a; 143(2): 189-195. PMid:16962245. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.08.005

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006....

found four out of five dogs infected with E. canis by molecular methods, which was the first molecular report of E. canis in the Amazon region. We have sampled a total of 129 domestic dogs from 20 different municipalities in the state of Pará and found 21 (16.2%) positive results to E. canis by IFA. Our results showed lower occurrence when compared to previous studies in dogs from western Amazon.

Overall, serum endpoint titers to Rickettsia spp. indicate that seropositive rural dogs had been predominately infected by R. amblyommii or by a closely related genotype, whereas seropositive urban dogs had been predominately infected by R. bellii or closely related genotypes (Table 1). Even though we have not recorded ectoparasitism of dogs, it has been reported that R. amblyommii infects exclusively ticks of the genusAmblyomma. In fact, in the Brazilian Amazonian region,R. amblyommii was detected in Amblyomma cajennense, Amblyomma coelebs, Amblyomma longirostre, and Amblyomma geayi (LABRUNA et al. 2004Labruna MB, Whitworth T, Bouyer DH, McBride J, Camargo LM, Camargo EP, et al. Rickettsia bellii and Rickettsia amblyommii in Amblyomma ticks from the State of Rondônia, Western Amazon, Brazil. J Med Entomol 2004; 41(6): 1073-1081. PMid:15605647. http://dx.doi.org/10.1603/0022-2585-41.6.1073

http://dx.doi.org/10.1603/0022-2585-41.6...

, 2011Labruna MB, Mattar S, Nava S, Bermudez S, Venzal JM, Dolz G, et al. Rickettsioses in Latin America, Caribbean, Spain and Portugal. Rev MVZ Córdoba 2011; 16(2): 2435-2457.). The former two ticks are known to parasitize dogs within the rural areas of the Amazon region (LABRUNA et al., 2005Labruna MB, Camargo LM, Camargo EP, Walker DH. Detection of a spotted fever group Rickettsia in the tick Haemaphysalis juxtakochi in Rondonia, Brazil. Vet Parasitol 2005; 127(2): 169-174. PMid:15631911. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.09.024

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004....

). Therefore, they might be related to the serological status of the dogs of the present study. Urban dogs reacted predominately to the non-Spotted Fever group agent R. bellii, an observation that should be further evaluated. It is worth mentioning that this rickettsia and closely related genotypes have been reported infecting species of nearly all tick genera of the New World (PHILIP et al., 1983Philip RN, Casper EA, Anacker RL, Cory J, Hayes SF, Burgdorfer W, et al. Rickettsia belli sp. nov.: a tick-borne rickettsia, widely distributed in the USA, that is distinct from the spotted fever and typhus biogroups. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1983; 33(1): 94-106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1099/00207713-33-1-94

http://dx.doi.org/10.1099/00207713-33-1-...

, LABRUNA et al., 2011Labruna MB, Mattar S, Nava S, Bermudez S, Venzal JM, Dolz G, et al. Rickettsioses in Latin America, Caribbean, Spain and Portugal. Rev MVZ Córdoba 2011; 16(2): 2435-2457.), as well as a broad range of insects and diverse organisms, including amoeba (WEINERT et al., 2009Weinert LA, Werren JH, Aebi A, Stone GN, Jiggins FM. Evolution and diversity of Rickettsia bacteria. BMC Biol 2009; 7: 6. PMid:19187530 PMCid:2662801. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1741-7007-7-6

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1741-7007-7-6...

).

In contrast to southern and southeastern Brazil, rickettsioses have never been reported in humans from northern Brazil (the Amazon region) (Labruna et al., 2011Labruna MB, Mattar S, Nava S, Bermudez S, Venzal JM, Dolz G, et al. Rickettsioses in Latin America, Caribbean, Spain and Portugal. Rev MVZ Córdoba 2011; 16(2): 2435-2457.). Indeed, our results indicate that there is circulation of a Spotted Fever group agent closely related toR. amblyommii in the rural area of the study region. To date,R. amblyommii is still considered of unknown pathogenicity. However, it has been proposed that some of the rickettsiosis cases reported as Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) (presumably caused by R. rickettsii) in the USA may have been caused by R. amblyommii (APPERSON et al., 2008Apperson CS, Engber B, Nicholson WL, Mead DG, Engel J, Yabsley MJ, et al. Tick-borne diseases in North Carolina: Is “Rickettsia amblyommii” a possible cause of rickettsiosis reported as Rocky Mountain spotted fever? Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2008; 8(5): 597-606. PMid:18447622. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2007.0271

http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2007.0271...

). This assumption relied on serological results, which demonstrated a four-fold increase in endpoint titers to R. amblyommii, but not to R. rickettsii, in acute and convalescent sera samples taken from clinical cases compatible with RMSF (APPERSON et al., 2008Apperson CS, Engber B, Nicholson WL, Mead DG, Engel J, Yabsley MJ, et al. Tick-borne diseases in North Carolina: Is “Rickettsia amblyommii” a possible cause of rickettsiosis reported as Rocky Mountain spotted fever? Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2008; 8(5): 597-606. PMid:18447622. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2007.0271

http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2007.0271...

).

In summary, this first study on tick-borne agents in dogs from the Brazilian eastern Amazon indicates that these dogs are exposed to several vector-borne infectious agents. These include Babesia organisms, mostly in the urban area, where B. canis vogeli is possibly being transmitted by R. sanguineus ticks; and Spotted Fever groupRickettsia organisms, mostly in the rural area, whereR. amblyommii is possibly being transmitted byAmblyomma ticks. In addition, dogs from both rural and urban areas are similarly exposed to Ehrlichia organisms. While it is well known that E. canis is transmitted by R. sanguineus ticks in the urban areas of the Amazon region, it is possible that other Ehrlichia species are transmitted by native tick species in the rural areas, resulting in similar seroprevalence values between urban and rural dogs. Further studies on tick species and isolation of tick-borne agents from ticks and vertebrate hosts in the Amazon region are needed to better elucidate the epidemiology of tick-borne diseases in the region.

The authors are grateful to the ‘Fundação de Amparo á Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo' (FAPESP) for the grants to MGS and HSS and to ‘Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico' (CNPq) for the grants to SYOBV, MBL, MFBR, AHHM and SMG.

References

- Aguiar DM, Saito TB, Hagiwara MK, Machado RZ, Labruna MB. Diagnóstico sorológico de erliquiose canina com antígeno brasileiro de Ehrlichia canis. Cienc Rural 2007a; 37(3): 796-802. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-84782007000300030

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-84782007000300030 - Aguiar DM, Cavalcante GT, Pinter A, Gennari SM, Camargo LM, Labruna MB. Prevalence of Ehrlichia canis (Rickettsiales: Anaplasmataceae) in dogs and Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Acari: Ixodidae) ticks from Brazil. J Med Entomol 2007b; 44(1): 126-132. http://dx.doi.org/10.1603/0022-2585(2007)44[126:POECRA]2.0.CO;2

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1603/0022-2585(2007)44[126:POECRA]2.0.CO;2 - Apperson CS, Engber B, Nicholson WL, Mead DG, Engel J, Yabsley MJ, et al. Tick-borne diseases in North Carolina: Is “Rickettsia amblyommii” a possible cause of rickettsiosis reported as Rocky Mountain spotted fever? Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2008; 8(5): 597-606. PMid:18447622. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2007.0271

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2007.0271 - Azevedo SS, Aguiar DM, Aquino SF, Orlandelli RC; Fernandes ARF, Uchôa ICP. Soroprevalência e fatores de risco associados á soropositividade para Ehrlichia canis em cães do semiárido da Paraíba. Braz J Vet Res Anim Sci 2011; 48(1): 14-18.

- Bastos CV, Moreira SM, Passos LM. Retrospective study (1998-2001) on canine babesiosis in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2004; 1026: 158-160. PMid:15604486. http://dx.doi.org/10.1196/annals.1307.023

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1196/annals.1307.023 - Bicalho KA, Ribeiro MF, Martins-Filho OA. Molecular fluorescent approach to assessing intraerythrocytic hemaprotozoan Babesia canis infection in dogs. Vet Parasitol 2004; 125(3-4): 221-235. PMid:15482880. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.08.009

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.08.009 - Chiebao DP. Frequência de anticorpos anti-Neospora caninum, anti-Brucella abortus e anti-Lesptospira spp. em bovinos do Estado do Pará: estudo de possíveis variáveis para ocorrência de infecção [Dissertação]. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo; 2010.

- Costa JO, Batista Júnior JA, Silva M, Guimarães PM. Ehrlichia canis infection in dog in Belo Horizonte - Brazil. Arq Esc Vet UFMG 1973; 25(2): 199-206.

- Dantas-Torres F. Causative agents of canine babesiosis in Brazil. Prev Vet Med 2008; 83(2): 210-211. PMid:17980446. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2007.03.008

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2007.03.008 - Dell'Porto A, Oliveira MR, Miguel O. Babesia canis in stray dogs from the city of São Paulo Comparative studies between the clinical and hematological aspects and the indirect fluorescence antibody test. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 1993; 2(1): 37-40.

- Horta MC, Labruna MB, Sangioni LA, Vianna MCB, Gennari SM, Galvão MAM, et al. Prevalence of antibodies to Spotted Fever Group Rickettsiae in humans and domestic animals in a Brazilian Spotted Fever-Endemic area in the State of São Paulo, Brazil: Serologic evidence for infection by Rickettsia rickettsii and another spotted fever group Rickettsia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2004; 71(1): 93-97. PMid:15238696.

- Horta MC, Sabatini GS, Moraes-Filho J, Ogrzewalska M, Canal RB, Pacheco RC, et al. Experimental Infection of the Opossum Didelphis aurita by Rickettsia felis, Rickettsia bellii and Rickettsia parkeri and Evaluation of the Transmission of the Infection to Ticks Amblyomma cajennense and Amblyomma dubitatum. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2010; 10(10): 959-967. PMid:20455783.http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2009.0149

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2009.0149 - Kuttler KL. Worldwide impact of babesiosis. In: Ristic M. Babesiosis of Domestic Animals and Man. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1988. 1-22.

- Labruna MB, Whitworth T, Bouyer DH, McBride J, Camargo LM, Camargo EP, et al. Rickettsia bellii and Rickettsia amblyommii in Amblyomma ticks from the State of Rondônia, Western Amazon, Brazil. J Med Entomol 2004; 41(6): 1073-1081. PMid:15605647. http://dx.doi.org/10.1603/0022-2585-41.6.1073

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1603/0022-2585-41.6.1073 - Labruna MB, Camargo LM, Camargo EP, Walker DH. Detection of a spotted fever group Rickettsia in the tick Haemaphysalis juxtakochi in Rondonia, Brazil. Vet Parasitol 2005; 127(2): 169-174. PMid:15631911. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.09.024

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.09.024 - Labruna MB, McBride JW, Camargo LM, Aguiar DM, Yabsley MJ, Davidson WR, et al. A preliminary investigation of Ehrlichia species in ticks, humans, dogs, and capybaras from Brazil. Vet Parasitol 2007a; 143(2): 189-195. PMid:16962245. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.08.005

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.08.005 - Labruna MB, Horta MC, Aguiar DM, Cavalcante GT, Pinter A, Gennari SM, et al. Prevalence of Rickettsia infection in dogs from the urban and rural areas of Monte Negro municipality, western Amazon, Brazil. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2007b; 7(2): 249-255. PMid:17627445. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2006.0621

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2006.0621 - Labruna MB, Mattar S, Nava S, Bermudez S, Venzal JM, Dolz G, et al. Rickettsioses in Latin America, Caribbean, Spain and Portugal. Rev MVZ Córdoba 2011; 16(2): 2435-2457.

- Machado RZ, Duarte JM, Dagnone AS, Szabó MP. Detection of Ehrlichia chaffeensis in Brazilian marsh deer (Blastocerus dichotomus). Vet Parasitol 2006; 139(1-3): 262-266. PMid:16621285. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.02.038

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.02.038 - Minervino AH, Ragozo AM, Monteiro RM, Ortolani EL, Gennari SM. Prevalence of Neospora caninum antibodies in cattle from Santarém, Pará, Brazil. Res Vet Sci 2008; 84(2): 254-256. PMid:17619028. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2007.05.003

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2007.05.003 - O'Dwyer LH, Massard CL, Pereira de Souza JCP. Hepatozoon canis infection associated with dog ticks of rural areas of Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil. Vet Parasitol 2001; 94(3): 143-150. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(00)00378-2

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(00)00378-2 - Oliveira LS, Oliveira KA, Mourão LC, Pescatore AM, Almeida MR, Conceição LG, et al. First report of Ehrlichia ewingii detected by molecular investigation in dogs from Brazil. Clin Microbiol Infect 2009; 15(S2): 55-56. PMid:19416280. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02635.x

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02635.x - Philip RN, Casper EA, Anacker RL, Cory J, Hayes SF, Burgdorfer W, et al. Rickettsia belli sp. nov.: a tick-borne rickettsia, widely distributed in the USA, that is distinct from the spotted fever and typhus biogroups. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1983; 33(1): 94-106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1099/00207713-33-1-94

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1099/00207713-33-1-94 - Piranda EM, Faccini JL, Pinter A, Saito TB, Pacheco RC, Hagiwara MK, et al. Experimental infection of dogs with a Brazilian strain of Rickettsia rickettsii: clinical and laboratory findings. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2008; 103(7): 696-701. PMid:19057821. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02762008000700012

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02762008000700012 - Ribeiro MFB, Passos LMF, Lima JD, Guimarães AM. Frequency of anti-Babesia canis antibodies in dogs, in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec 1990; 42(6):511-517.

- Rodrigues AFSF, D'Agosto M, Daemon E. Babesia canis (Piana & Galli-Valerio, 1895) (Apicomplexa: Babesiidae) em cães de rua do Município de Juiz de Fora, MG. Rev Bras Med Vet 2002; 24(1): 17-21.

- Saito TB, Cunha-Filho NA, Pacheco RC, Ferreira F, Pappen FG, Farias NA, et al. Canine infection by rickettsiae and ehrlichiae in southern Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2008; 79(1): 102-108. PMid:18606772.

- Serra-Freire NM. Occurrence of ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) on human hosts, in three municipalities in the State of Pará, Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2010; 19(3): 141-147. PMid:20943016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612010000300003

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612010000300003 - Silva JN, Almeida ABPF, Boa Sorte EC, Freitas AG, Santos LGF, Aguiar DM, et al. Seroprevalence anti-Ehrlichia canis antibodies in dogs of Cuiabá, Mato Grosso. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2010; 19(2): 108-111. PMid:20624348.http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbpv.01902008

» http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbpv.01902008 - Soares AO, Souza AD, Feliciano EA, Rodrigues AF, D'Agosto M, Daemon E. Avaliação ectoparasitológica e hemoparasitológica em cães criados em apartamentos e casas com quintal na cidade de Juiz de Fora, MG. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2006; 15(1): 13-16. PMid:16646996.

- Spolidorio MG, Labruna MB, Machado RZ, Moraes-Filho J, Zago AM, Donatele DM, et al. Survey for tick-borne zoonoses in the state of Espírito Santo, southeastern Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2010; 83(1): 201-206. PMid:20595502 PMCid:2912600. http://dx.doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0595

» http://dx.doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0595 - Spolidorio MG, Torres MM, Campos WNS, Melo ALT, Igarashi M, Amude AM, et al. Molecular detection of Hepatozoon canis and Babesia canis vogeli in domestic dogs from Cuiabá, Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2011; 20(3): 253-255. PMid:21961759. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612011000300015

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612011000300015 - Trapp SM, Dagnone AS, Vidotto O, Freire RL, Amude AM, Morais HS. Seroepidemiology of canine babesiosis and ehrlichiosis in a hospital population. Vet Parasitol 2006; 140(3-4): 223-230. PMid:16647817. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.03.030

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.03.030 - Valadas S, Minervino AHH, Lima VMF, Soares RM, Ortolani EL, Gennari SM. Occurrence of antibodies anti-Neospora caninum, anti-Toxoplasma gondii, and anti-Leishmania chagasi in serum of dogs from Pará State, Amazon, Brazil. Parasitol Res 2010; 107(2): 453-457. PMid:20445991. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-010-1890-2

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-010-1890-2 - Vieira RF, Biondo AW, Guimarães AM, Dos Santos AP, Dos Santos RP, Dutra LH, et al. Ehrlichiosis in Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2011; 20(1): 1-12. PMid:21439224. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612011000100002

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612011000100002 - Weinert LA, Werren JH, Aebi A, Stone GN, Jiggins FM. Evolution and diversity of Rickettsia bacteria. BMC Biol 2009; 7: 6. PMid:19187530 PMCid:2662801. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1741-7007-7-6

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1741-7007-7-6 - Widmer CE, Azevedo FC, Almeida AP, Ferreira F, Labruna MB. Tickborne bacteria in free living jaguars (Panthera onca) in Pantanal, Brazil. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2011; 11(8): 1001-1005. PMid:21612532. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2011.0619

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2011.0619

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

25 June 2013 -

Date of issue

abr-jun 2013

History

-

Received

18 June 2012 -

Accepted

1 Feb 2013