Abstract

This study was the first investigation on the parasites of Triportheus rotundatus, a Characiformes fish from the Amazon, in Brazil. All the fish collected (100%) in a tributary from the Amazon River system were infected by one or more parasite species. The mean species richness of parasites was 4.9 ± 0.9, the Brillouin index was 0.39 ± 0.16, the evenness was 0.24 ± 0.09 and the Berger-Parker dominance was 0.81 ± 0.13. A total of 1316 metazoan parasites were collected, including Anacanthorus pithophallus, Anacanthorus furculus, Ancistrohaptor sp. (Dactylogyridae), Genarchella genarchella (Derogenidae), Posthodiplostomum sp. (Diplostomidae), Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) inopinatus (Camallanidae), Echinorhynchus paranensis (Echinorhynchidae) and Ergasilus sp. (Ergasilidae), but monogenoideans were the dominant parasites. These parasites presented an aggregate dispersion pattern, except for P. (S.) inopinatus, which showed a random dispersion pattern. The body conditions of the hosts were not affected by the parasitism levels. This first report of these parasites for T. rotundatus indicates that the presence of ectoparasites and endoparasites was due to hosts behavior and availability of infective stages in the environment, and this was discussed.

Keywords:

Amazon; diversity; endoparasites; freshwater fish; infracommunity

Resumo

Este estudo foi a primeira investigação sobre os parasitos de Triportheus rotundatus, um Characiformes da Amazônia, no Brasil. Todos os peixes coletados (100%) em um afluente do sistema Rio Amazonas estavam infectados por uma ou mais espécies de parasitos. A riqueza média de espécies de parasitos foi 4,9 ± 0,9, índice de Brillouin 0.39 ± 0,16, equitabilidade 0,24 ± 0,09 e a dominância de Berger-Parker foi 0,81 ± 0,13. Um total de 1.316 parasitos metazoários foram coletados, incluindo Anacanthorus pithophallus, Anacanthorus furculus, Ancistrohaptor sp. (Dactylogyridae), Genarchella genarchella (Derogenidae), Posthodiplostomum sp. (Diplostomidae), Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) inopinatus (Camallanidae), Echinorhynchus paranensis (Echinorhynchidae) e Ergasilus sp. (Ergasilidae), mas monogenoideas foram os parasitos dominantes. Estes parasitos apresentaram padrão de dispersão agregado, com exceção de P. (S.) inopinatus, que mostrou padrão de dispersão randômico. As condições corporais dos hospedeiros não foram afetadas pelos níveis de parasitismo. Este primeiro relato desses parasitos em T. rotundatus indica que a presença de ectoparasitos e endoparasitos foi devido ao comportamento dos hospedeiros e disponibilidade de estágios infectantes no ambiente, e isso foi discutido.

Palavras-chave:

Amazônia; diversidade; endoparasitos; peixes de água doce; infracomunidades

Introduction

The Amazon basin is a center of diversity for most groups of Neotropical fish, that is to say, it is an area of high species richness, due to its large extension of floodplains, which are important habitats for native fish, providing feeding and nursery zones. Conservative estimates suggest there are about 3,000 fish species in this basin (ALBERT & REIS, 2011Albert JS, Reis RE. Historical biogeography of Neotropical freshwater fishes. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2011.; JUNK, 2013Junk WJ. Current state of knowledge regarding South America wetlands and their future under global climate change. Aquat Sci 2013; 75(1): 113-131. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00027-012-0253-8.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00027-012-025...

; FROESE & PAULY, 2016Froese R, Pauly DeditorsFishBase. Version (06/2016)online2016cited 2016 Aug 30Available from: www.fishbase.org). In the Amazonian estuary, there are 243 fish species, of which 23 are endemic species. Many of these fish are important for trade and economy in the Amazon, and constitute the main source of food for human populations in the region. Moreover, this basin has diverse tributaries draining its water levels, which vary enormously during the year (ALBERT & REIS, 2011Albert JS, Reis RE. Historical biogeography of Neotropical freshwater fishes. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2011.), including the Igarapé Fortaleza hydrographic basin.

In the Amazon River system, in the region of the state of Amapá (Northern Brazil), there is the Igarapé Fortaleza hydrographic basin, an important tributary of this river. The Igarapé Fortaleza basin, located at the estuarine coastal sector, is characterized for having a river system with extensive floodplains, which is drained by fresh water and connected to a main watercourse, influenced by high rainfalls and tides (every 12 hours) from the Amazonas River (TAVARES-DIAS et al., 2013Tavares-Dias M, Neves LR, Pinheiro DA, Oliveira MSB, Marinho RGB. Parasites in (Characiformes: Curimatidae) from eastern Amazon, Brazil. Curimata cyprinoidesActa Sci Biol Sci 2013; 35(4): 595-601. http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/actascibiolsci.v35i4.19649.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/actascibiolsci...

). This tributary of the Amazon River system harbors more than 80 species of freshwater fish (GAMA & HALBOTH, 2004Gama CS, Halboth DA. Ictiofauna das ressacas das bacias do Igarapé da Fortaleza e do Rio Curiaú. In: Takiyama LR, Silva AQ. Diagnóstico das ressacas do Estado do Amapá: bacias do Igarapé da Fortaleza e Rio Curiaú, Macapá-AP. Macapá: CPAQ/IEPA, DGEO/SEMA; 2004. p. 23-52.), including Characiformes species of the genus Triportheus Cope, 1872, which are popularly known as freshwater sardines and represents an important resource for artisanal fishing and subsistence of human population in the region.

Triportheus spp. are Characidae with a geographic wide distribution in Bolivia, Colombia, Peru, Argentina, Ecuador, Venezuela and Brazil (SANTOS et al., 2006Santos GM, Ferreira EJG, Zuanon JAS. Peixes comerciais de Manaus. Manaus: Ibama/AM, PróVárzea; 2006.; FROESE & PAULY, 2016Froese R, Pauly DeditorsFishBase. Version (06/2016)online2016cited 2016 Aug 30Available from: www.fishbase.org). Currently, 18 species of Triportheus Cope, 1872 are known, including Triportheus rotundatus Jardine, 1841 (MALABARBA, 2004Malabarba MCSL. Revision of the Neotropical genus Cope, 1872 (Characiformes: Characidae). TriportheusNeotrop Ichthyol 2004; 2(4): 167-204. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1679-62252004000400001.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1679-62252004...

; FROESE & PAULY, 2016Froese R, Pauly DeditorsFishBase. Version (06/2016)online2016cited 2016 Aug 30Available from: www.fishbase.org), the fish species that is the focus of the present study. The species of Triportheus inhabit most of the major river drainages of South America, and constitutes an important element in both commercial and subsistence fisheries in the Amazon basin (MALABARBA, 2004Malabarba MCSL. Revision of the Neotropical genus Cope, 1872 (Characiformes: Characidae). TriportheusNeotrop Ichthyol 2004; 2(4): 167-204. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1679-62252004000400001.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1679-62252004...

), its reproduction occurs during the rainy season in the Amazon River system (FROESE & PAULY, 2016Froese R, Pauly DeditorsFishBase. Version (06/2016)online2016cited 2016 Aug 30Available from: www.fishbase.org). Triportheus rotundatus is a benthopelagic fish with an omnivorous diet, fed on fruits, seeds and insects that float on the water surface, besides microcrustaceans (PEREIRA et al., 2011Pereira JO, Silva MT, Vieira LJS, Fugi R. Effects of flood regime on the diet of (Garman, 1890) in an Amazonian floodplain lake. Triportheus curtusNeotrop Ichthyol 2011; 9(3): 623-628. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1679-62252011005000029.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1679-62252011...

; FROESE & PAULY, 2016Froese R, Pauly DeditorsFishBase. Version (06/2016)online2016cited 2016 Aug 30Available from: www.fishbase.org; SUÇUARANA et al., 2016Suçuarana MS, Virgílio LR, Vieira LJS. Trophic structure of fish assemblages associated with macrophytes in lakes of an abandoned meander on the middle river Purus, Brazilian Amazon. Acta Sci Biol Sci 2016; 38(1): 37-46. http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/actascibiolsci.v38i1.28973.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/actascibiolsci...

). However, studies on the biology of T. rotundatus are reduced, mostly those regarding its parasitic fauna.

Studies on parasitic fauna aspects should be directed to T. rotundatus, due to the importance of knowledge on several factors that could influence the diversity and structure of the parasite infracommunities in fish populations (MOREIRA et al., 2009Moreira LHA, Takemoto RM, Yamada FH, Ceschini TL, Pavanelli GC. Ecological aspects of metazoan endoparasites of (Cope, 1870) (Characidae) from upper Paraná River floodplain, Brazil. Metynnis lippincottianusHelminthologia 2009; 46(4): 214-219. http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/s11687-009-0040-9.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/s11687-009-004...

; LAGRUE et al., 2011Lagrue C, Kelly DW, Hicks A, Poulin R. Factors influencing infection patterns of trophically transmitted parasites among a fish community: host diet, host–parasite compatibility or both? J Fish Biol 2011; 79(2): 466-485. PMid:21781103.; TAVARES-DIAS et al., 2013Tavares-Dias M, Neves LR, Pinheiro DA, Oliveira MSB, Marinho RGB. Parasites in (Characiformes: Curimatidae) from eastern Amazon, Brazil. Curimata cyprinoidesActa Sci Biol Sci 2013; 35(4): 595-601. http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/actascibiolsci.v35i4.19649.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/actascibiolsci...

; COSTA-PEREIRA et al., 2014Costa-Pereira R, Paiva F, Tavares LER. Variation in the parasite community of the sardine fish (Actinopterygii: Characidae) from the Medalha lagoon in the Pantanal wetland, Brazil. Triportheus nematurusJ Helminthol 2014; 88(3): 272-277. PMid:23506711. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X1300014X.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X13000...

; OLIVEIRA et al., 2016Oliveira MSB, Gonçalves RA, Tavares-Dias M. Community of parasites in Triportheus curtus and Triportheus angulatus (Characidae) from a tributary of the Amazon River system (Brazil). Stud Neotrop Fauna Environ 2016; 51(1): 29-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01650521.2016.1150095.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01650521.2016....

). Moreover, the knowledge about parasites community infracommunities and their relationship with the host fish is of great importance, because the parasites also play a key role in ecosystems by regulating the abundance or density of natural fish populations, thus stabilizing food web and host community structures (MOREIRA et al., 2009Moreira LHA, Takemoto RM, Yamada FH, Ceschini TL, Pavanelli GC. Ecological aspects of metazoan endoparasites of (Cope, 1870) (Characidae) from upper Paraná River floodplain, Brazil. Metynnis lippincottianusHelminthologia 2009; 46(4): 214-219. http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/s11687-009-0040-9.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/s11687-009-004...

; MORLEY, 2012Morley NJ. Cercariae (Platyhelmintes: Trematoda) as neglected components of zooplankton communities in freshwater habitats. Hydrobiologia 2012; 691(1): 7-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10750-012-1029-9.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10750-012-102...

; TAVARES-DIAS et al., 2013Tavares-Dias M, Neves LR, Pinheiro DA, Oliveira MSB, Marinho RGB. Parasites in (Characiformes: Curimatidae) from eastern Amazon, Brazil. Curimata cyprinoidesActa Sci Biol Sci 2013; 35(4): 595-601. http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/actascibiolsci.v35i4.19649.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/actascibiolsci...

; OLIVEIRA et al., 2016Oliveira MSB, Gonçalves RA, Tavares-Dias M. Community of parasites in Triportheus curtus and Triportheus angulatus (Characidae) from a tributary of the Amazon River system (Brazil). Stud Neotrop Fauna Environ 2016; 51(1): 29-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01650521.2016.1150095.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01650521.2016....

). However, the ecological knowledge of parasites in Neotropical environments is yet very limited.

Although there is no information on the parasites of T. rotundatus, for other Triportheus spp. diverse Anacanthorus species, Ancistrohaptor sp., Ichthyophthirius multifiliis, Piscinoodinium pilullare, Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) sp., Procamallanus (Procamallanus) peraccuratus, Procamallanus hilarii, Contracaecum sp, Goezia sp., Echinorhynchus paranensis, Ergasilus sp. and Dolops sp. have been reported (MACHADO, 1959Machado DA Fo. Echinorhynchidae do Brasil. II. Nova espécie do gênero Zoega in Müller, 1776. EchinorhynchusMem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1959; 57(2): 195-197. PMid:14419411. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761959000200006.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761959...

; KRITSKY et al., 1992Kritsky DC, Boeger WA, Van Every LR. Neotropical Monogenoidea. 17. Anacanthorus Mizelle and Price, 1965 (Dactylogyridae, Anacanthorinae) from Characoid fishes of the central Amazon. J Helm Soc Wash 1992; 59(1): 25-51.; COHEN et al., 2013Cohen SC, Justo MCN, Kohn A. South American Monogenoidea parasites of fishes, amphibians and reptiles. Rio de Janeiro: Oficina de Livros; 2013.; COSTA-PEREIRA et al., 2014Costa-Pereira R, Paiva F, Tavares LER. Variation in the parasite community of the sardine fish (Actinopterygii: Characidae) from the Medalha lagoon in the Pantanal wetland, Brazil. Triportheus nematurusJ Helminthol 2014; 88(3): 272-277. PMid:23506711. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X1300014X.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X13000...

; OLIVEIRA et al., 2016Oliveira MSB, Gonçalves RA, Tavares-Dias M. Community of parasites in Triportheus curtus and Triportheus angulatus (Characidae) from a tributary of the Amazon River system (Brazil). Stud Neotrop Fauna Environ 2016; 51(1): 29-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01650521.2016.1150095.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01650521.2016....

). However, there are no studies on the parasites of T. rotundatus. In this way, the present study was the first investigation on several aspects of parasite communities in T. rotundatus from a tributary of the Amazon River, in the state of Amapá (Northern Brazil).

Materials and Methods

Fish and parasite sampling

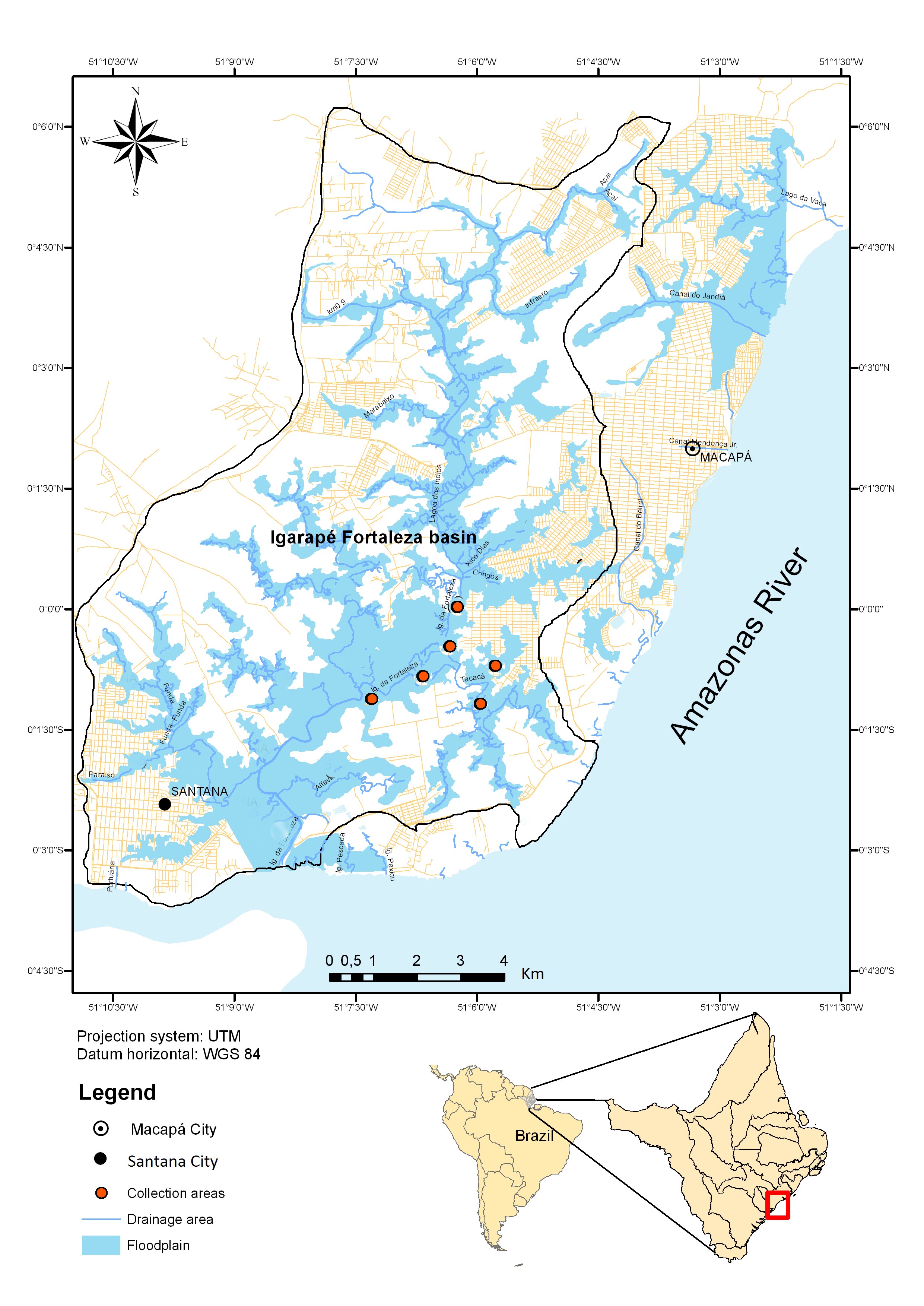

Thirty-two T. rotundatus (14.7 ±1.3 cm and 39.4 ± 10.8 g) were collected in the Igarapé Fortaleza basin, in the state of Amapá, eastern Amazon region, northern Brazil (Figure 1), in the period from December 2012 to August 2013 for parasitological analysis. The fish were caught with different nets and transported in box with ice to the Health Laboratory of Aquatic Organisms of Embrapa Amapá, Macapá, Amapá state (Brazil). The fish collected were weighed (g) and measured for total length (cm). The present work was developed according to the principles adopted by the Brazilian College of Animal Experiments (COBEA), with the authorization from Ethics Committee in the Use of Animal of the Embrapa Amapá (#004 - CEUA/CPAFAP) and ICMBio (# 23276-1).

Collection locality of Triportheus rotundatus in tributary from Amazon River system, Northern Brazil.

Parasite collection and analysis procedures

Each individual was macroscopically evaluated regarding body surface, mouth, eyes, opercula and gills. The gills were removed to collect ectoparasites. The gastrointestinal tract was removed and examined to collect endoparasites. All the parasites were collected, fixed, quantified and stained for identification (EIRAS et al., 2006Eiras JC, Takemoto RM, Pavanelli GC. Métodos de estudo e técnicas laboratoriais em parasitologia de peixes. Maringá: Eduem; 2006.). The parasitological terms adopted were those recommended by Bush et al. (1997)Bush AO, Lafferty KD, Lotz JM, Shostak AW. Parasitology meets ecology on its own terms: Margolis et al. revisited. J Parasitol 1997; 83(4): 575-583. PMid:9267395. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3284227.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3284227...

.

For the parasite community, the species richness, the Brillouin diversity index, evenness in association with the diversity index, and the Berger-Parker dominance index and the dominance frequency (percentage of the infracommunities in which a parasite species is numerically dominant) (ROHDE et al., 1995Rohde K, Hayward C, Heap M. Aspects of the ecology of metazoan ectoparasites of marine fishes. Int J Parasitol 1995; 25(8): 945-970. PMid:8550295. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0020-7519(95)00015-T.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0020-7519(95)0...

; MAGURRAN, 2004Magurran AE. Measuring biological diversity. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2004.) were calculated using the Diversity software (Pisces Conservation Ltd., UK). The index of dispersion (ID), and the index of discrepancy of Poulin (D) were calculated using the Quantitative Parasitology 3.0 software to detect the distribution pattern of the infracommunity parasites (RÓZSA et al., 2000Rózsa L, Reiczigel J, Majoros G. Quantifying parasites in samples of hosts. J Parasitol 2000; 86(2): 228-232. PMid:10780537. http://dx.doi.org/10.1645/0022-3395(2000)086[0228:QPISOH]2.0.CO;2.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1645/0022-3395(2000...

) for species with prevalence > 10%. The ID significance for each infracommunity was tested using the d-statistics (LUDWIG & REYNOLDS, 1988Ludwig JA, Reynolds JF. Statistical ecology: a primer on methods and computing. New York: Wiley-Interscience Pub; 1988.).

Fish data on weight (g) and total length (cm) were used to calculate the relative condition factor (Kn) of hosts, which was compared to the standard value (Kn = 1.00) using the t-test. Body weight (g) and total length (cm) were used to calculate the relative condition factor (Kn) of fish using the length-weight relationship (W = aLb) after a logarithmic transformation of length and weight and subsequent adjustment of two straight lines, obtaining lny = lnA + Blnx (LE CREN, 1951Le Cren ED. The length-weight relationship and seasonal cycle in gonad weight and condition in the perch (Perca fluviatilis). J Anim Ecol 1951; 20(2): 201-219. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1540.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1540...

). The Spearman correlation coefficient (rs) was used to determine possible correlations of parasite abundance with the length and weight, as well as with the species richness and the Brillouin diversity of the hosts (ZAR, 2010Zar JH. Biostatistical analysis. 5th ed. New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 2010.).

Results

All examined fish (100%) were parasitized by one or more metazoan species, and 1,316 parasites were collected. Anacanthorus pithophallus Kritsky, Boeger & Van Every, 1992; Anacanthorus furculus Kritsky, Boeger & Van Every, 1992; Ancistrohaptor sp. (Dactylogyridae); Genarchella genarchella Travassos, Artigas & Pereira, 1928 (Derogenidae); Posthodiplostomum sp. (Diplostomidae); Procamallanus (Spirocamallanus) inopinatus Travassos, Artigas & Pereira, 1928 (Camallanidae); Echinorhynchus paranensis Machado, 1959 (Echinorhynchidae) and Ergasilus sp. (Ergasilidae) were found (Table 1). Monogenoideans were the dominant parasite species, and although these parasites were not possible to count by species, the predominance was de A. furculus and A. pithophallus. None protozoan parasite was found. Parasites had an aggregate dispersion pattern, except for P. (S.) inopinatus, which presented random dispersion pattern (Table 2).

Index of dispersion (ID), d-statistic and discrepancy index (D) for the parasite infracommunities of Triportheus rotundatus from Amazon River system (Brazil).

The species richness of parasites, the Brillouin diversity (HB) and evenness (E) were low (Table 3). Species richness of parasites (rs = 0.243, p= 0.180) and HB (rs = 0.273, p= 0.130) did not show any significant correlation with total host length. Hosts parasitized by four to five parasite species were predominant (Figure 2).

The abundance of monogenoideans presented negative correlation with the length (rs = - 0.363, p= 0.041) and weight (rs = -0.511, p= 0.003) of the hosts. The abundance of G. genarchella showed no correlation with the length (rs = -0.013, p = 0.941) and weight (rs = -0.069, p = 0.705), as well as the abundance of Posthodiplostomum sp. with the length (rs = -0.132, p = 0.471) and weight (rs = -0.218, p = 0.228), and the abundance of P. (S.) inopinatus with the length (rs = 0.075, p = 0.680) and weight (rs = 0.038, p = 0.832) of the hosts.

The equation of weight (W)-length (L) relationship for this host was Wt = 0.1493Lt2.0653, r2 = 0.710), with negative allometric, indicating greater increase in body weight than in size. The condition factor (Kn = 0.999, t = -0.0041, p = 0.997) of the parasitized fish did not differ from the standard value (Kn = 1.000), thus indicating that the parasitism did not impair host body condition.

Discussion

In T. rotundatus, the parasitic community was composed of 3 species of Monogenoidea, 2 Digenea, 1 Nematoda, 1 Acanthocephala and 1 Copepoda, with a dominance of monogenoideans (A. pithophallus, A. furculus and Ancistrohaptor sp.). Moreover, low species richness, low Brillouin diversity, low evenness, a high diversity of endoparasites species, and overdispersion of parasites characterized this parasitic community. Many parasite species commonly show overdispersion in different host fish (COSTA-PEREIRA et al., 2014Costa-Pereira R, Paiva F, Tavares LER. Variation in the parasite community of the sardine fish (Actinopterygii: Characidae) from the Medalha lagoon in the Pantanal wetland, Brazil. Triportheus nematurusJ Helminthol 2014; 88(3): 272-277. PMid:23506711. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X1300014X.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X13000...

; TAVARES-DIAS et al., 2015Tavares-Dias M, Dias-Júnior MBF, Florentino AC, Silva LM, Cunha AC. Distribution pattern of crustacean ectoparasites of freshwater fish from Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2015; 24(2): 136-147. PMid:26154954. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612015036.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612015...

; OLIVEIRA et al., 2016Oliveira MSB, Gonçalves RA, Tavares-Dias M. Community of parasites in Triportheus curtus and Triportheus angulatus (Characidae) from a tributary of the Amazon River system (Brazil). Stud Neotrop Fauna Environ 2016; 51(1): 29-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01650521.2016.1150095.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01650521.2016....

), due to processes that produce variability in host exposure, host acceptability by the parasite and host immune response. For Triportheus nematurus from Pantanal Matogrossense (Brazil) 1 species of Monogenoidea, 3 Nematoda and 1 Copepoda were reported, being Anacanthorus sp. the main component and predominant in helminth species with overdispersion (COSTA-PEREIRA et al., 2014Costa-Pereira R, Paiva F, Tavares LER. Variation in the parasite community of the sardine fish (Actinopterygii: Characidae) from the Medalha lagoon in the Pantanal wetland, Brazil. Triportheus nematurusJ Helminthol 2014; 88(3): 272-277. PMid:23506711. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X1300014X.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X13000...

). For Triportheus curtus Garman, 1890 and Triportheus elongatus Spix & Agassiz, 1829 from same region of this study 3 species of Protozoa, 1 Monogenoidea, 1 Argulidae, 2 Digenea and 2 Nematoda were reported, being I. multifiliis the predominant parasite species (OLIVEIRA et al., 2016Oliveira MSB, Gonçalves RA, Tavares-Dias M. Community of parasites in Triportheus curtus and Triportheus angulatus (Characidae) from a tributary of the Amazon River system (Brazil). Stud Neotrop Fauna Environ 2016; 51(1): 29-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01650521.2016.1150095.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01650521.2016....

). However, we found a higher parasitic prevalence and abundance in T. rotundatus when compared to those observed by Costa-Pereira et al. (2014)Costa-Pereira R, Paiva F, Tavares LER. Variation in the parasite community of the sardine fish (Actinopterygii: Characidae) from the Medalha lagoon in the Pantanal wetland, Brazil. Triportheus nematurusJ Helminthol 2014; 88(3): 272-277. PMid:23506711. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X1300014X.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X13000...

in T. nematurus. Such differences for this fish species with a similar mode of life may be attributed to the environment and the opportunities of these hosts found infective stages of parasites with complex life cycle.

Monogenoideans are parasites that are highly host specific when compared to other groups of parasites. Studies suggest that the distribution of monogenoideans on their fish hosts is strongly influenced by evolutionary history, both between and within fish orders (KRITSKY et al., 1992Kritsky DC, Boeger WA, Van Every LR. Neotropical Monogenoidea. 17. Anacanthorus Mizelle and Price, 1965 (Dactylogyridae, Anacanthorinae) from Characoid fishes of the central Amazon. J Helm Soc Wash 1992; 59(1): 25-51.; BRAGA et al., 2014Braga MP, Araújo SBL, Boeger WA. Patterns of interaction between Neotropical freshwater fishes and their gill Monogenoidea (Platyhelminthes). Parasitol Res 2014; 113(2): 481-490. PMid:24221891. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-013-3677-8.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-013-367...

). The gills of T. rotundatus were infected by A. pithophallus, A. furculus and Ancistrohaptor sp., parasites whose abundance presented a negative correlation with the size of the hosts. Such monogenoidean species has been also recorded in other Triportheus species from Brazil (KRITSKY et al., 1992Kritsky DC, Boeger WA, Van Every LR. Neotropical Monogenoidea. 17. Anacanthorus Mizelle and Price, 1965 (Dactylogyridae, Anacanthorinae) from Characoid fishes of the central Amazon. J Helm Soc Wash 1992; 59(1): 25-51.; COHEN et al., 2013Cohen SC, Justo MCN, Kohn A. South American Monogenoidea parasites of fishes, amphibians and reptiles. Rio de Janeiro: Oficina de Livros; 2013.; OLIVEIRA et al., 2016Oliveira MSB, Gonçalves RA, Tavares-Dias M. Community of parasites in Triportheus curtus and Triportheus angulatus (Characidae) from a tributary of the Amazon River system (Brazil). Stud Neotrop Fauna Environ 2016; 51(1): 29-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01650521.2016.1150095.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01650521.2016....

). However, while Ancistrohaptor spp. seems restricted to Triportheus spp. (COHEN et al., 2013Cohen SC, Justo MCN, Kohn A. South American Monogenoidea parasites of fishes, amphibians and reptiles. Rio de Janeiro: Oficina de Livros; 2013.; BRAGA et al., 2014Braga MP, Araújo SBL, Boeger WA. Patterns of interaction between Neotropical freshwater fishes and their gill Monogenoidea (Platyhelminthes). Parasitol Res 2014; 113(2): 481-490. PMid:24221891. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-013-3677-8.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-013-367...

), Anacanthorus spp. presents a widespread distribution among freshwater fish species, once that they are also found in diverse Characiformes species of fish from several families (BRAGA et al., 2014Braga MP, Araújo SBL, Boeger WA. Patterns of interaction between Neotropical freshwater fishes and their gill Monogenoidea (Platyhelminthes). Parasitol Res 2014; 113(2): 481-490. PMid:24221891. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-013-3677-8.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-013-367...

).

Characteristics of the habitat may facilitate the transmission and establishment of fish parasites (MOREIRA et al., 2009Moreira LHA, Takemoto RM, Yamada FH, Ceschini TL, Pavanelli GC. Ecological aspects of metazoan endoparasites of (Cope, 1870) (Characidae) from upper Paraná River floodplain, Brazil. Metynnis lippincottianusHelminthologia 2009; 46(4): 214-219. http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/s11687-009-0040-9.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/s11687-009-004...

; COSTA-PEREIRA et al., 2014Costa-Pereira R, Paiva F, Tavares LER. Variation in the parasite community of the sardine fish (Actinopterygii: Characidae) from the Medalha lagoon in the Pantanal wetland, Brazil. Triportheus nematurusJ Helminthol 2014; 88(3): 272-277. PMid:23506711. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X1300014X.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X13000...

; BITTENCOURT et al., 2014Bittencourt LS, Pinheiro DA, Cárdenas MQ, Fernandes BMM, Tavares-Dias M. Parasites of native Cichlidae populations and invasive Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758) in tributary of Amazonas River (Brazil). Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2014; 23(1): 44-54. PMid:24728360. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612014006.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612014...

; OLIVEIRA et al., 2016Oliveira MSB, Gonçalves RA, Tavares-Dias M. Community of parasites in Triportheus curtus and Triportheus angulatus (Characidae) from a tributary of the Amazon River system (Brazil). Stud Neotrop Fauna Environ 2016; 51(1): 29-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01650521.2016.1150095.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01650521.2016....

). The abundance and diversity of the invertebrate fauna are also key components in the formation of a parasite community in fish populations (MOREIRA et al., 2009Moreira LHA, Takemoto RM, Yamada FH, Ceschini TL, Pavanelli GC. Ecological aspects of metazoan endoparasites of (Cope, 1870) (Characidae) from upper Paraná River floodplain, Brazil. Metynnis lippincottianusHelminthologia 2009; 46(4): 214-219. http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/s11687-009-0040-9.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/s11687-009-004...

; MORLEY, 2012Morley NJ. Cercariae (Platyhelmintes: Trematoda) as neglected components of zooplankton communities in freshwater habitats. Hydrobiologia 2012; 691(1): 7-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10750-012-1029-9.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10750-012-102...

; TAVARES-DIAS et al., 2015Tavares-Dias M, Dias-Júnior MBF, Florentino AC, Silva LM, Cunha AC. Distribution pattern of crustacean ectoparasites of freshwater fish from Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2015; 24(2): 136-147. PMid:26154954. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612015036.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612015...

). Moreover, environments with abundance of aquatic vegetation (e.g. macrophytes), as the ecosystem of this study (THOMAZ et al., 2004Thomaz DO, Costa Neto SV, Tostes LCL. Inventario florístico das ressacas das bacias do Igarapé da Fortaleza e do Rio Curiaú. In: Takiyama LR, Silva AQ. Diagnóstico das ressacas do Estado do Amapá: bacias do Igarapé da Fortaleza e Rio Curiau, Macapá-AP. Macapá: CPAQ/IEPA; DGEO/SEMA; 2004. p. 11-32.), may influence the abundance of parasites (MOREIRA et al., 2009Moreira LHA, Takemoto RM, Yamada FH, Ceschini TL, Pavanelli GC. Ecological aspects of metazoan endoparasites of (Cope, 1870) (Characidae) from upper Paraná River floodplain, Brazil. Metynnis lippincottianusHelminthologia 2009; 46(4): 214-219. http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/s11687-009-0040-9.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/s11687-009-004...

; MORLEY, 2012Morley NJ. Cercariae (Platyhelmintes: Trematoda) as neglected components of zooplankton communities in freshwater habitats. Hydrobiologia 2012; 691(1): 7-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10750-012-1029-9.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10750-012-102...

), because its floodplains areas are widely used for shelter and feeding by many fish species. Consequently, this increases the possibility of the fish finding different infective stages of the parasite species in the environment. Therefore, these factors favored the transmission of G. genarchella, Posthodiplostomum sp., P. (S.) inopinatus and E. paranensis in T. rotundatus. Most of these endoparasites present a wide distribution in freshwater fish from Brazil and have different macroinvertebrates as intermediate hosts. Procamallanus (S.) inopinatus has chironomid species as intermediate hosts (MOREIRA et al., 2009Moreira LHA, Takemoto RM, Yamada FH, Ceschini TL, Pavanelli GC. Ecological aspects of metazoan endoparasites of (Cope, 1870) (Characidae) from upper Paraná River floodplain, Brazil. Metynnis lippincottianusHelminthologia 2009; 46(4): 214-219. http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/s11687-009-0040-9.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/s11687-009-004...

), while digeneans G. genarchella and Posthodiplostomum sp. have mollusk species as intermediate hosts and aquatic fish-eating birds as definitive host. Concerning E. paranensis, it was described by the first time on Triportheus paranensis Günther, 1874 from Mato-Grosso, Brazil (MACHADO, 1959Machado DA Fo. Echinorhynchidae do Brasil. II. Nova espécie do gênero Zoega in Müller, 1776. EchinorhynchusMem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1959; 57(2): 195-197. PMid:14419411. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761959000200006.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761959...

). Recently, this acanthocephalan has also been reported infecting Pygocentrus nattereri Kner, 1860 (Serrasalmidae) from Negro River, at Pantanal of the Mato Grosso do Sul (Brazil), as well as Chaetobranchus flavescens Heckel, 1840 and Chaetobranchopsis orbicularis Steindachner, 1875 (Cichlidae) from the region of this study (BITTENCOURT et al., 2014Bittencourt LS, Pinheiro DA, Cárdenas MQ, Fernandes BMM, Tavares-Dias M. Parasites of native Cichlidae populations and invasive Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758) in tributary of Amazonas River (Brazil). Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2014; 23(1): 44-54. PMid:24728360. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612014006.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612014...

). However, as there are few reports on the occurrence of E. paranensis in fish, little is known about its biology and life cycle.

Concerning Ergasilus sp., these copepods occurred only on the gills of two specimens of T. rotundatus, because the water dynamic of the Igarapé Fortaleza basin seems to hinder the encounter of the parasitic crustacean species with host fish, once these ectoparasites need swimming to infect its host fish. Similarly, Costa-Pereira et al. (2014)Costa-Pereira R, Paiva F, Tavares LER. Variation in the parasite community of the sardine fish (Actinopterygii: Characidae) from the Medalha lagoon in the Pantanal wetland, Brazil. Triportheus nematurusJ Helminthol 2014; 88(3): 272-277. PMid:23506711. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X1300014X.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X13000...

also reported low prevalence and abundance of Ergasilus sp. in T. nematurus. Moreover, some parasitic crustacean species are host and site-specific, especially in relation to fish in particular habitats and life styles, while other parasites frequently have no preference. There is a dominance of Ergasilidae, mainly Ergasilus Nordmann, 1832, among the parasitic crustaceans in freshwater fish from Brazil. However, Ergasilus spp. have infested species of Characidae, Pimelodidae, Anostomidae and Cichlidae from the Amazon (TAVARES-DIAS et al., 2015Tavares-Dias M, Dias-Júnior MBF, Florentino AC, Silva LM, Cunha AC. Distribution pattern of crustacean ectoparasites of freshwater fish from Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2015; 24(2): 136-147. PMid:26154954. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612015036.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612015...

; TABORDA et al., 2016Taborda NL, Paschoal P, Luque JL. A new species of Ergasilus (Copepoda: Ergasilidae) from Geophagus altifrons and G. argyrostictus (Perciformes: Cichlidae) in the Brazilian Amazon. Acta Parasitol 2016; 61(3): 549-555. PMid:27447219. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/ap-2016-0073.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/ap-2016-0073...

). Twenty-two freshwater species of Ergasilus are known from the gills of Neotropical fish (TABORDA et al., 2016Taborda NL, Paschoal P, Luque JL. A new species of Ergasilus (Copepoda: Ergasilidae) from Geophagus altifrons and G. argyrostictus (Perciformes: Cichlidae) in the Brazilian Amazon. Acta Parasitol 2016; 61(3): 549-555. PMid:27447219. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/ap-2016-0073.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/ap-2016-0073...

).

In summary, for T. rotundatus the ectoparasites community consisted of species with high prevalence and abundance, while the endoparasites community presented low prevalence and abundance, which did not affected the body condition of the hosts. The presence of endoparasites with a complex life cycle indicates that in this environment, the diet of T. rotundatus consists mostly of chironomids, mollusks and microcrustaceans. Thus, T. rotundatus is an intermediate or paratenic host for G. genarchella, Posthodiplostomum and E. paranensis, and a definitive host for P. (S.) inopinatus. The size of the host had little influence on parasite communities, once they had influence only on monogenoideans. Finally, the behavior and availability of infective stages, which intermediate hosts for endoparasites, were factors structuring the communities of parasites in this Amazonian host.

Acknowledgements

Dr. M. Tavares-Dias was granted (#303013/2015-0) a Research fellowship from the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, Brazil).

References

- Albert JS, Reis RE. Historical biogeography of Neotropical freshwater fishes. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2011.

- Bittencourt LS, Pinheiro DA, Cárdenas MQ, Fernandes BMM, Tavares-Dias M. Parasites of native Cichlidae populations and invasive Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758) in tributary of Amazonas River (Brazil). Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2014; 23(1): 44-54. PMid:24728360. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612014006

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612014006 - Braga MP, Araújo SBL, Boeger WA. Patterns of interaction between Neotropical freshwater fishes and their gill Monogenoidea (Platyhelminthes). Parasitol Res 2014; 113(2): 481-490. PMid:24221891. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-013-3677-8

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-013-3677-8 - Bush AO, Lafferty KD, Lotz JM, Shostak AW. Parasitology meets ecology on its own terms: Margolis et al. revisited. J Parasitol 1997; 83(4): 575-583. PMid:9267395. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3284227

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3284227 - Cohen SC, Justo MCN, Kohn A. South American Monogenoidea parasites of fishes, amphibians and reptiles. Rio de Janeiro: Oficina de Livros; 2013.

- Costa-Pereira R, Paiva F, Tavares LER. Variation in the parasite community of the sardine fish (Actinopterygii: Characidae) from the Medalha lagoon in the Pantanal wetland, Brazil. Triportheus nematurusJ Helminthol 2014; 88(3): 272-277. PMid:23506711. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X1300014X

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022149X1300014X - Eiras JC, Takemoto RM, Pavanelli GC. Métodos de estudo e técnicas laboratoriais em parasitologia de peixes. Maringá: Eduem; 2006.

- Froese R, Pauly DeditorsFishBase. Version (06/2016)online2016cited 2016 Aug 30Available from: www.fishbase.org

- Gama CS, Halboth DA. Ictiofauna das ressacas das bacias do Igarapé da Fortaleza e do Rio Curiaú. In: Takiyama LR, Silva AQ. Diagnóstico das ressacas do Estado do Amapá: bacias do Igarapé da Fortaleza e Rio Curiaú, Macapá-AP. Macapá: CPAQ/IEPA, DGEO/SEMA; 2004. p. 23-52.

- Junk WJ. Current state of knowledge regarding South America wetlands and their future under global climate change. Aquat Sci 2013; 75(1): 113-131. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00027-012-0253-8

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00027-012-0253-8 - Kritsky DC, Boeger WA, Van Every LR. Neotropical Monogenoidea. 17. Anacanthorus Mizelle and Price, 1965 (Dactylogyridae, Anacanthorinae) from Characoid fishes of the central Amazon. J Helm Soc Wash 1992; 59(1): 25-51.

- Lagrue C, Kelly DW, Hicks A, Poulin R. Factors influencing infection patterns of trophically transmitted parasites among a fish community: host diet, host–parasite compatibility or both? J Fish Biol 2011; 79(2): 466-485. PMid:21781103.

- Le Cren ED. The length-weight relationship and seasonal cycle in gonad weight and condition in the perch (Perca fluviatilis). J Anim Ecol 1951; 20(2): 201-219. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1540

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1540 - Ludwig JA, Reynolds JF. Statistical ecology: a primer on methods and computing. New York: Wiley-Interscience Pub; 1988.

- Machado DA Fo. Echinorhynchidae do Brasil. II. Nova espécie do gênero Zoega in Müller, 1776. EchinorhynchusMem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1959; 57(2): 195-197. PMid:14419411. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761959000200006

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761959000200006 - Magurran AE. Measuring biological diversity. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2004.

- Malabarba MCSL. Revision of the Neotropical genus Cope, 1872 (Characiformes: Characidae). TriportheusNeotrop Ichthyol 2004; 2(4): 167-204. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1679-62252004000400001

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1679-62252004000400001 - Moreira LHA, Takemoto RM, Yamada FH, Ceschini TL, Pavanelli GC. Ecological aspects of metazoan endoparasites of (Cope, 1870) (Characidae) from upper Paraná River floodplain, Brazil. Metynnis lippincottianusHelminthologia 2009; 46(4): 214-219. http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/s11687-009-0040-9

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2478/s11687-009-0040-9 - Morley NJ. Cercariae (Platyhelmintes: Trematoda) as neglected components of zooplankton communities in freshwater habitats. Hydrobiologia 2012; 691(1): 7-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10750-012-1029-9

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10750-012-1029-9 - Oliveira MSB, Gonçalves RA, Tavares-Dias M. Community of parasites in Triportheus curtus and Triportheus angulatus (Characidae) from a tributary of the Amazon River system (Brazil). Stud Neotrop Fauna Environ 2016; 51(1): 29-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01650521.2016.1150095

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01650521.2016.1150095 - Pereira JO, Silva MT, Vieira LJS, Fugi R. Effects of flood regime on the diet of (Garman, 1890) in an Amazonian floodplain lake. Triportheus curtusNeotrop Ichthyol 2011; 9(3): 623-628. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1679-62252011005000029

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1679-62252011005000029 - Rohde K, Hayward C, Heap M. Aspects of the ecology of metazoan ectoparasites of marine fishes. Int J Parasitol 1995; 25(8): 945-970. PMid:8550295. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0020-7519(95)00015-T

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0020-7519(95)00015-T - Rózsa L, Reiczigel J, Majoros G. Quantifying parasites in samples of hosts. J Parasitol 2000; 86(2): 228-232. PMid:10780537. http://dx.doi.org/10.1645/0022-3395(2000)086[0228:QPISOH]2.0.CO;2

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1645/0022-3395(2000)086[0228:QPISOH]2.0.CO;2 - Santos GM, Ferreira EJG, Zuanon JAS. Peixes comerciais de Manaus. Manaus: Ibama/AM, PróVárzea; 2006.

- Suçuarana MS, Virgílio LR, Vieira LJS. Trophic structure of fish assemblages associated with macrophytes in lakes of an abandoned meander on the middle river Purus, Brazilian Amazon. Acta Sci Biol Sci 2016; 38(1): 37-46. http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/actascibiolsci.v38i1.28973

» http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/actascibiolsci.v38i1.28973 - Taborda NL, Paschoal P, Luque JL. A new species of Ergasilus (Copepoda: Ergasilidae) from Geophagus altifrons and G. argyrostictus (Perciformes: Cichlidae) in the Brazilian Amazon. Acta Parasitol 2016; 61(3): 549-555. PMid:27447219. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/ap-2016-0073

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/ap-2016-0073 - Tavares-Dias M, Dias-Júnior MBF, Florentino AC, Silva LM, Cunha AC. Distribution pattern of crustacean ectoparasites of freshwater fish from Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2015; 24(2): 136-147. PMid:26154954. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612015036

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612015036 - Tavares-Dias M, Neves LR, Pinheiro DA, Oliveira MSB, Marinho RGB. Parasites in (Characiformes: Curimatidae) from eastern Amazon, Brazil. Curimata cyprinoidesActa Sci Biol Sci 2013; 35(4): 595-601. http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/actascibiolsci.v35i4.19649

» http://dx.doi.org/10.4025/actascibiolsci.v35i4.19649 - Thomaz DO, Costa Neto SV, Tostes LCL. Inventario florístico das ressacas das bacias do Igarapé da Fortaleza e do Rio Curiaú. In: Takiyama LR, Silva AQ. Diagnóstico das ressacas do Estado do Amapá: bacias do Igarapé da Fortaleza e Rio Curiau, Macapá-AP. Macapá: CPAQ/IEPA; DGEO/SEMA; 2004. p. 11-32.

- Zar JH. Biostatistical analysis. 5th ed. New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 2010.

Data availability

Data citations

Froese R, Pauly DeditorsFishBase. Version (06/2016)online2016cited 2016 Aug 30Available from: www.fishbase.org

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

01 Dec 2016 -

Date of issue

Jan-Mar 2017

History

-

Received

30 Aug 2016 -

Accepted

25 Oct 2016