Abstract

The aim of this study was to confirm the emergence of canine visceral leishmaniasis among dogs in Foz do Iguaçu. The disease was diagnosed through the isolation and molecular identification of Leishmania infantum. In the first sample collection stage (2012), three lymph node aspirates and 46 buffy coat samples were obtained mostly from the dogs that were seroreagents for leishmaniasis. In the second sample collection stage (2013), the buffy coat samples were collected from 376 dogs located close to Paraguay, Paraná river, center and peripheral parts of the city. The DNA from the six isolates, four from the first sampling stage (4/49) and two from the second sampling stage (2/376), was subjected to polymerase chain reaction using the K26F/R primers. The isolate was confirmed as L. infantum by sequencing. As none of the dogs had ever left the city, the isolates were confirmed as autochthonous. Further, the study confirmed the emergence of canine visceral leishmaniasis in Paraná through the identification of L. infantum among dogs in Foz do Iguaçu city. Hence, collaborative control measures should be designed and implemented by the public agencies and research institutions of Brazil, Argentina, and Paraguay to control the spread of visceral leishmaniasis.

Keywords:

Dog; zoonosis; molecular characterization; southern Brazil

Resumo

O objetivo deste estudo foi confirmar a emergência da leishmaniose visceral canina em Foz do Iguaçu próximo à fronteira com a Argentina e ao Paraguai, por meio do isolamento e identificação molecular de Leishmania infantum. Em um primeiro estágio de coleta de animais (2012), três amostras de aspirados de linfonodos e 46 camadas leucocitárias foram obtidas de cães soropositivos para leishmaniose. Em um segundo estágio de coleta (2013), foram coletadas amostras de camada leucocitária de 376 cães de 20 localidades próximas à fronteira com o Paraguai, rio Paraná, centro e periferia da cidade. Seis isolados foram obtidos, quatro da primeira etapa (4/49) e dois da segunda etapa (2/376); estes isolados foram submetidos à amplificação com iniciadores K26F/R, e a análise de sua sequência confirmou a espécie como L. infantum. A autoctonia dos casos foi confirmada, pois 100% dos cães nunca haviam saído da cidade. O estudo confirma a emergência de leishmaniose visceral canina no Paraná com identificação de L. infantum em cães da cidade de Foz do Iguaçu. Assim, medidas de controle devem ser elaboradas e implementadas por órgãos públicos e instituições de pesquisa do Brasil, Argentina e Paraguai em parceria com o objetivo de controlar a disseminação de zoonoses e os casos humanos de LV.

Palavras-chave:

Cão; zoonose; caracterização molecular; Sul do Brasil

Introduction

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is a zoonotic vector-borne disease, caused by an intracellular protozoan belonging to the genus Leishmania (ROSS, 1903Ross R. Note on the bodies recently described by Leishman and Donovan. BMJ 1903; 2(2237): 1261-1262. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.2.2237.1261. PMid:20761169.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.2.2237.126...

). In Latin America, Leishmania infantum is the etiological agent of VL (ROMERO & BOELAERT, 2010Romero GAS, Boelaert M. Control of visceral leishmaniasis in latin america: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2010; 4(1): e584. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0000584. PMid:20098726.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0...

). The vector for the transmission of parasite is the phlebotomine sandflies. Lutzomyia longipalpis is the predominant vector species involved in the transmission of parasite in Brazil (MARZOCHI et al., 1980Marzochi MCA, Coutinho SG, Sabroza PC, Souza WJS. Reação de imunofluorescência indireta e intradermorreação para leishmaniose tegumentar americana em moradores na área de Jacarepaguá (Rio de Janeiro). Estudo comparativo dos resultados observados em 1974 e 1978. Rev do Inst Med Trop 1980; 22(3): 149-155.). Cases of VL in humans are usually preceded by cases of the disease in dogs. The dogs have a higher number of parasites in the skin than that in humans (SCHIMMING & SILVA, 2012Schimming BC, Silva JRCP. Leishmaniose visceral canina: revisão de literatura. Rev Cient Elet Med Vet 2012; 10(19): 1-17.), hence, domestic dogs are the most important reservoir for the transmission of VL in urban areas. In 2008, the first autochthonous case of canine visceral leishmaniasis (CVL) was recorded in the Southern region of Brazil. This case was recorded in São Borja, Rio Grande do Sul (RS), a city that borders Corrientes, Argentina, which had an intense infection transmission (TARTAROTTI et al., 2011Tartarotti AL, Donini MA, Anjos C, Ramos RR. Leishmaniose Visceral no Rio Grande do Sul - Vigilância de reservatórios caninos. Bol Epidemiol 2011; 13(1): 3-6.). Paraná state was considered a disease-free area for CVL and had only allochthonous cases (THOMAZ-SOCCOL et al., 2009Thomaz-Soccol V, Castro EA, Navarro IT, Farias MR, Souza LM, Carvalho Y, et al. Casos alóctones de leishmaniose visceral canina no Paraná, Brasil: implicações epidemiológicas. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2009; 18(3): 46-51. http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbpv.01803008. PMid:19772775.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbpv.01803008...

) until 2012. The city of Foz do Iguaçu, which is located to the west of Paraná state in a tri-border area, is a tourist and economic center with a high flow of people and animals, and has abundant vegetation between the Paraná and Iguaçu rivers. As Puerto Iguazú, Argentina, was the first city of the tri-border area to register both L. longipalpis vector (SALOMÓN et al., 2011Salomón OD, Fernández MS, Santini MS, Saavedra S, Montiel N, Ramos MA, et al. Distribución de Lutzomyia longipalpis en la Mesopotamia Argentina, 2010. Medicina (B Aires) 2011; 71(1): 22-26. PMid:21296716.) and autochthonous CVL cases in 2011 (ACOSTA et al., 2015Acosta L, Díaz R, Torres P, Silva G, Ramos M, Fattore G, et al. Identification of Leishmania infantum in Puerto Iguazú, Misiones, Argentina. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo 2015; 57(2): 175-176. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0036-46652015000200013. PMid:25923899.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0036-46652015...

), a study on the vector and CVL was initiated in Foz do Iguaçu. In 2012, an entomological study verified the presence of the L. longipalpis vector and the city was classified as a receptive vulnerable silent area for VL (SANTOS et al., 2012Santos DR, Ferreira AC, Bisetto A Jr. The first record of Lutzomyia longipalpis (Lutz & Neiva, 1912) (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) in the State of Paraná, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2012; 45(5): 643-645. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0037-86822012000500019. PMid:23152351.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0037-86822012...

). The first autochthonous case of human visceral leishmaniasis (HVL) was confirmed in the city of Foz do Iguaçu in 2015 (PINA TRENCH et al., 2016Pina Trench FJ, Ritt AG, Gewehr TA, Leandro AS, Chiyo L, RittGewehr M, et al. First report of autochthonous visceral leishmaniosis in humans in Foz do Iguaçu, Paraná State, Southern Brazil. Ann Clin Cytol Pathol 2016; 2(6): 1041.). The aim of this study was to confirm the emergence of CVL in localities of the Foz do Iguaçu city, which shares a border with Argentina and Paraguay, through the isolation and molecular identification of the L. infantum parasite.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee on Animal Use of Londrina State University (CEUA Nº. 22530.2013). The samples from dogs were collected after the dog owners filled out a term of authorization and awareness. The study was conducted in the Brazilian city of Foz do Iguaçu (latitude 25º 32' 45” S and longitude 54º 35' 07” W), which is located to the west of Paraná State and shares a border with Paraguay and Argentina (IBGE, 2012Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE. Cidades - Paraná - Foz do Iguaçu [online]. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2012 [cited 2018 Aug 22]. Available from: http://cidades.ibge.gov.br/xtras/perfil.php?lang=&codmun= 410830&search=%7C%7Cinfogr%E1ficos:-informa%E7%F5es-completas

http://cidades.ibge.gov.br/xtras/perfil....

). The estimated average population of the city was 259,313 in the years 2012 and 2013 (IBGE, 2013Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE. Estimativas da população residente nos municípios brasileiros com data de referência em 1o de julho de 2013 [online]. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2013 [cited 2017 Aug 22]. Available from: ftp://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Estimativas_de_Populacao/Estimativas_2013/nota_metodologica_2013.pdf

ftp://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Estimativas_de_Pop...

). The sampling was performed in two stages. The first sampling was performed in December 2012, which included 46 urban domiciled dogs. Among these 46 dogs, 14 were previously identified as seroreagents in more than one serodiagnostic techniques (immunochromatographic rapid test (DPP®); enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA); indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA), 14 dogs tested positive only in ELISA, and 18 dogs were not subjected to serological diagnosis previously. The second sampling was performed between June 2013 and July 2013, where 376 urban domiciled dogs were selected from 20 localities located near the Paraguay border, Paraná River, and the central and peripheral regions of the city. The households were selected based on the data from the entomological survey performed by the Ninth Health Region, Paraná State (SANTOS et al., 2012Santos DR, Ferreira AC, Bisetto A Jr. The first record of Lutzomyia longipalpis (Lutz & Neiva, 1912) (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) in the State of Paraná, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2012; 45(5): 643-645. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0037-86822012000500019. PMid:23152351.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0037-86822012...

). The EDTA blood samples were collected from all dogs and popliteal lymph node puncture was performed on dogs exhibiting clinical symptoms of VL. The isolates were confirmed as autochthonous because none of the tested dogs had ever left the city, according to their owner’s information. The leukocyte layer and lymph-node aspirate samples were added to the Novy, McNeal and Nicolle (NNN) medium containing 0.5 mL of 0.9% physiological solution, penicillin (25,000 IU), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL). The cultures were sampled every seven days until the parasite was isolated or were discarded when the sample tested negative after the fifth week. The isolates were inoculated in RPMI (Roswell Park Memorial Institute) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The conical tubes (15 mL) were observed every week and when a high amount of Leishmania spp. were obtained, they were transferred to a cell culture bottle containing 10 mL of RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS. After seven days, the parasites were harvested by centrifugation at 3,500 g and 4°C for 10 min. The pellet was transferred to a 2 mL tube and centrifuged at 9,000 g and 4°C for 5 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the biomass was stored in the freezer at -20°C until the time of DNA extraction. Two methods were used for DNA extraction in this study. The DNA from samples obtained at stage 1 was extracted using the phenol-chloroform method, following the protocols of Sambrook et al. (1989)Sambrook J, Fritschi EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989., while that from samples obtained at stage 2 was extracted using the Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega®, Madison, WI, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Negative controls were used at all extraction stages and the DNA was quantified using the Gene Quant™ spectrophotometer (Marlborough, MA, USA). The parasite species was confirmed using the following primers: K26R (5'-ACGAAGGACTCCGCAAAG-3') and K26F (5'-TTCCCATCGTTTTGCTG-3') (HARALAMBOUS et al., 2008Haralambous C, Antoniou M, Pratlong F, Dedet JP, Soteriadou K. Development of a molecular assay specific for the Leishmania donovani complex that discriminates L. donovani/L. infantum zymodemes: a useful tool for typing MON-1. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2008; 60(1): 33-42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.07.019. PMid:17889482.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio...

). The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed in a 25 μL reaction volume containing 2.5 μL of buffer, 1.0 μL of each primer (K26r/K26f), 2.0 μL of dNTP, 1.25 μL of MgCl2, 0.25 μL of 0.1% Triton-X 100, 0.1 μL of Taq polymerase (Invitrogen®, Brazil), and 5 μL of DNA. The PCR conditions were as follows: 94°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 48°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. The DNA sample extracted from the reference strain, L. infantum (MHOM/FR/71/LEM75) was used as a positive control. The amplified samples were subjected to agarose gel horizontal electrophoresis using 1.5% gel. The gel was stained with ethidium bromide for 20 min and visualized under ultraviolet light. The amplified DNA fragments were subjected to sequencing. The reactions were processed in 2.0 mL microtubes in a 10 μL reaction volume containing 1.6 pmol/μL of the primers, 1.0 μL of BigDye® Terminator, 1.0 μL of the reaction buffer, 50 ng of DNA, and ultra-pure water. The consensus sequences were generated using the EMBOSS GUI program (EMBOSS, 2017European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite – EMBOSS [online]. 2017 [cited 2017 Aug 22]. Available from: http://bips.u-strasbg.fr/EMBOSS

http://bips.u-strasbg.fr/EMBOSS...

) and submitted to the basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) program (NBCI, 2017National Center for Biotechnology Information – NBCI [online]. Bethesda: U.S. National Library of Medicine; 2017 [cited 2017 Aug 22]. Available from: http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi

http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi...

) to confirm the results. The sequence of L. infantum deposited at Genbank was used to analyze the genetic distance between the samples. The sequences were aligned in the BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor (CARLSBAD, CA, USA) and analyzed in the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) program (version 5.05) (TAMURA et al., 2011Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 2011; 28(10): 2731-2739. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msr121. PMid:21546353.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msr121...

) for the phylogenetic tree construction.

Results

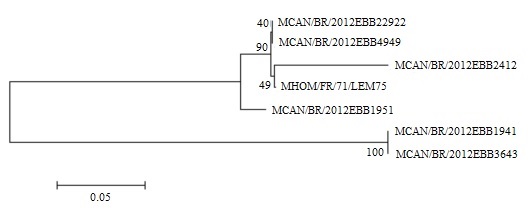

From stage 1 sampling, three isolates from lymph node aspirates were obtained (MCAN/BR/2012EBB1941, MCAN/BR/2012EBB1951, and MCAN/BR/2012EBB4949) and one after culturing a leukocyte layer sample (MCAN/BR/2012EBB22922). From stage 2 sampling, two isolates (MCAN/BR/2012EBB2412 and MCAN/BR/2012EBB3643) were obtained by culturing the leukocyte layer samples. Figure 1 shows the geographical location of L. infantum isolates that were sequenced in the city of Foz do Iguaçu. The points on the map are identified with the final international code number of each isolate. The MCAN/BR/2012EBB1941 and MCAN/BR/2012EBB1951 isolates were isolated from the neighboring residences in Jardim Flores. The Leishmania strain MCAN/BR/2012EBB22922 was isolated from Jardim Novo Horizonte, while MCAN/BR/2012EBB4949 was isolated from Jardim Tropical. The location from which the isolates were obtained was close to the Argentina border and the Iguaçu River. The MCAN/BR/2012EBB2412 isolate was obtained from the Loteamento Paraguaçu and the MCAN/BR/2012EBB3643 isolate was obtained from the central region near the Brazil-Paraguay customs, both close to the Paraná River. The parasites were identified by sequencing the six isolates and by comparing the K26 gene sequence with that of the amplified L. infantum strains. The K26 gene sequence of the isolates exhibited 86-100% sequence similarity with that of the L. infantum strains in the BLAST program (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The nucleotide sequence data reported in this study are available in the GenBank database. The phylogenetic tree exhibited two distinct clusters (Figure 2).

Geographical distribution of sequenced Leishmania infantum isolates in the city of Foz do Iguaçu, Paraná, Brazil, 2012-2013.

Phylogenetic tree relating the sequences of the reference sample Leishmania infantum MHOM/FR/71/LEM75 with six isolates, generated by MEGA version 5 program using the Tamura-Nei model to measure the evolutionary distance.

Discussion

In this study, the K26 gene, which encodes hydrophilic acylated surface protein B (HASPB), of the parasite isolates was sequenced. This protein is part of a heterogeneous family of surface molecules of the species from the genus Leishmania (MCKEAN et al., 1997McKean PG, Trenholme KR, Rangarajan D, Keen JK, Smith DF. Diversity in repeat-containing surface proteins of Leishmania major. Mol Biochem Parasitol 1997; 86(2): 225-235. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0166-6851(97)00035-2. PMid:9200128.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0166-6851(97)...

). The protein is polymorphic and consists of a series of repetitive amino acid domains and is present in the promastigote and amastigote forms of the parasite (SÁDLOVÁ et al., 2010Sádlová J, Price HP, Smith BA, Votỳpka J, Volf P, Smith DF. The stage-regulated HASPB and SHERP proteins are essential for differentiation of the protozoan parasite Leishmania major in its sand fly vector, Phlebotomus papatasi. Cell Microbiol 2010; 12(12): 1765-1779. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01507.x. PMid:20636473.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-5822.20...

). Haralambous et al. (2008)Haralambous C, Antoniou M, Pratlong F, Dedet JP, Soteriadou K. Development of a molecular assay specific for the Leishmania donovani complex that discriminates L. donovani/L. infantum zymodemes: a useful tool for typing MON-1. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2008; 60(1): 33-42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.07.019. PMid:17889482.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio...

designed specific primers (K26R/K26F) to distinguish the parasites of the L. donovani complex and to evaluate the genetic diversity and the correlation of gene polymorphisms with the geographic origin of the strains. The K26 gene of the six isolates exhibited 86-100% similarity with the K26 gene of the L. infantum strains. This indicated a genetic relationship with the L. donovani complex. Compared to the total score among the species of the L. donovani complex, L. chagasi exhibited a higher score or a lower number of gaps, which indicates fewer differences in the nucleotide sequence upon sequence alignment in the BLAST program of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database. Several studies suggest L. infantum synonymous with L. chagasi as there is no significant degree of genetic diversity between them (DANTAS-TORRES, 2006Dantas-Torres F. Leishmania infantum versus Leishmania chagasi: do not forget the law of priority. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2006; 101(1): 117-118, discussion 118. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02762006000100024. PMid:16699722.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02762006...

; MAURÍCIO et al., 2000Maurício IL, Stothard JR, Miles MA. The strange case of Leishmania chagasi. Parasitol Today 2000; 16(5): 188-189. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0169-4758(00)01637-9. PMid:10782075.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0169-4758(00)...

; RIOUX et al., 1990Rioux JA, Lanotte G, Serres E, Pratlong F, Bastien P, Perieres J. Taxonomy of Leishmania. Use of isoenzymes. Suggestions for a new classification. Ann Parasitol Hum Comp 1990; 65(3): 111-125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1051/parasite/1990653111. PMid:2080829.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1051/parasite/19906...

; THOMAZ-SOCCOL et al., 1993Thomaz-Soccol V, Lanotte G, Rioux JA, Pratlong F, Martini-Dumas A, Serres E. Phylogenetic taxonomy of new world Leishmania. Ann Parasitol Hum Comp 1993; 68(2): 104-106. PMid:7692803.). Hence, the isolates can be considered similar to the L. infantum species. The phylogenetic tree exhibited two distinct clusters. The L. infantum MHOM/FR/71/LEM75 (LEM75) reference strain clustered with the MCAN/BR/2012EBB22922, MCAN/BR/2012EBB4949, and MCAN/BR/2012EBB2412 isolates with a bootstrap value of 90%. The K26 gene sequence of MCAN/BR/2012EBB2412 isolate exhibited the highest similarity with that of LEM75. The MCAN/BR/2012EBB1941 and MCAN/BR/2012EBB3643 isolates were in a separate cluster of the LEM, which indicated that these isolates may be variant strains. Hence, the circulating strains in the city of Foz do Iguaçu and those in Argentina and Paraguay must be identified to understand the dynamics of VL in the tri-border area.

HVL is a public health concern, which is demonstrated by the increasing number of autochthonous cases in the city of Foz do Iguaçu since 2015 (PINA TRENCH et al, 2016Pina Trench FJ, Ritt AG, Gewehr TA, Leandro AS, Chiyo L, RittGewehr M, et al. First report of autochthonous visceral leishmaniosis in humans in Foz do Iguaçu, Paraná State, Southern Brazil. Ann Clin Cytol Pathol 2016; 2(6): 1041.). Hence, it is important that the public agencies and research institutions of Brazil, Argentina, and Paraguay conduct a detailed collaborative study of VL in the region and, to elaborate viable control measures to contain the spread of VL to neighboring cities. Additionally, collaborative efforts must be undertaken to identify the circulating strains and to constantly monitor the vector and the prevalence of VL.

Conclusion

The circulation of L. infantum in the city of Foz do Iguaçu was demonstrated by analyzing the sequence similarity of isolates with other strains from Genbank. This study demonstrates that autochthonous canine visceral leishmaniasis occur in the state of Paraná since 2012.

Acknowledgements

We especially thank Stephanny Friedrich from Universidade Federal do Paraná; Aldair Calistro de Mattos and Felippe Danyel Cardoso Martins from Universidade Estadual de Londrina for their support during the lab analyses and discussions.

-

How to cite: Dias RCF, Pasquali AKS, Thomaz-Soccol V, Pozzolo EM, Chiyo L, Alban SM, Fendrich RC, Almeida RAA, Ferreira FP, Caldart ET, Freire RL, Mitsuka-Breganó R, Bisetto Júnior A, Navarro IT. Autochthonous canine visceral leishmaniasis cases occur in Paraná state since 2012: isolation and identification of Leishmania infantum. Braz J Vet Parasitol 2020; 29(1): e009819. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612019083

References

- Acosta L, Díaz R, Torres P, Silva G, Ramos M, Fattore G, et al. Identification of Leishmania infantum in Puerto Iguazú, Misiones, Argentina. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo 2015; 57(2): 175-176. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0036-46652015000200013 PMid:25923899.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0036-46652015000200013 - Dantas-Torres F. Leishmania infantum versus Leishmania chagasi: do not forget the law of priority. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2006; 101(1): 117-118, discussion 118. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02762006000100024 PMid:16699722.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02762006000100024 - European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite – EMBOSS [online]. 2017 [cited 2017 Aug 22]. Available from: http://bips.u-strasbg.fr/EMBOSS

» http://bips.u-strasbg.fr/EMBOSS - Haralambous C, Antoniou M, Pratlong F, Dedet JP, Soteriadou K. Development of a molecular assay specific for the Leishmania donovani complex that discriminates L. donovani/L. infantum zymodemes: a useful tool for typing MON-1. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2008; 60(1): 33-42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.07.019 PMid:17889482.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.07.019 - Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE. Cidades - Paraná - Foz do Iguaçu [online]. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2012 [cited 2018 Aug 22]. Available from: http://cidades.ibge.gov.br/xtras/perfil.php?lang=&codmun= 410830&search=%7C%7Cinfogr%E1ficos:-informa%E7%F5es-completas

» http://cidades.ibge.gov.br/xtras/perfil.php?lang=&codmun= - Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE. Estimativas da população residente nos municípios brasileiros com data de referência em 1o de julho de 2013 [online]. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2013 [cited 2017 Aug 22]. Available from: ftp://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Estimativas_de_Populacao/Estimativas_2013/nota_metodologica_2013.pdf

» ftp://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Estimativas_de_Populacao/Estimativas_2013/nota_metodologica_2013.pdf - Marzochi MCA, Coutinho SG, Sabroza PC, Souza WJS. Reação de imunofluorescência indireta e intradermorreação para leishmaniose tegumentar americana em moradores na área de Jacarepaguá (Rio de Janeiro). Estudo comparativo dos resultados observados em 1974 e 1978. Rev do Inst Med Trop 1980; 22(3): 149-155.

- Maurício IL, Stothard JR, Miles MA. The strange case of Leishmania chagasi. Parasitol Today 2000; 16(5): 188-189. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0169-4758(00)01637-9 PMid:10782075.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0169-4758(00)01637-9 - McKean PG, Trenholme KR, Rangarajan D, Keen JK, Smith DF. Diversity in repeat-containing surface proteins of Leishmania major. Mol Biochem Parasitol 1997; 86(2): 225-235. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0166-6851(97)00035-2 PMid:9200128.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0166-6851(97)00035-2 - National Center for Biotechnology Information – NBCI [online]. Bethesda: U.S. National Library of Medicine; 2017 [cited 2017 Aug 22]. Available from: http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi

» http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi - Pina Trench FJ, Ritt AG, Gewehr TA, Leandro AS, Chiyo L, RittGewehr M, et al. First report of autochthonous visceral leishmaniosis in humans in Foz do Iguaçu, Paraná State, Southern Brazil. Ann Clin Cytol Pathol 2016; 2(6): 1041.

- Rioux JA, Lanotte G, Serres E, Pratlong F, Bastien P, Perieres J. Taxonomy of Leishmania Use of isoenzymes. Suggestions for a new classification. Ann Parasitol Hum Comp 1990; 65(3): 111-125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1051/parasite/1990653111 PMid:2080829.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1051/parasite/1990653111 - Romero GAS, Boelaert M. Control of visceral leishmaniasis in latin america: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2010; 4(1): e584. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0000584 PMid:20098726.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0000584 - Ross R. Note on the bodies recently described by Leishman and Donovan. BMJ 1903; 2(2237): 1261-1262. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.2.2237.1261 PMid:20761169.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.2.2237.1261 - Sádlová J, Price HP, Smith BA, Votỳpka J, Volf P, Smith DF. The stage-regulated HASPB and SHERP proteins are essential for differentiation of the protozoan parasite Leishmania major in its sand fly vector, Phlebotomus papatasi. Cell Microbiol 2010; 12(12): 1765-1779. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01507.x PMid:20636473.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01507.x - Salomón OD, Fernández MS, Santini MS, Saavedra S, Montiel N, Ramos MA, et al. Distribución de Lutzomyia longipalpis en la Mesopotamia Argentina, 2010. Medicina (B Aires) 2011; 71(1): 22-26. PMid:21296716.

- Sambrook J, Fritschi EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual 2nd ed. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989.

- Santos DR, Ferreira AC, Bisetto A Jr. The first record of Lutzomyia longipalpis (Lutz & Neiva, 1912) (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) in the State of Paraná, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2012; 45(5): 643-645. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0037-86822012000500019 PMid:23152351.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0037-86822012000500019 - Schimming BC, Silva JRCP. Leishmaniose visceral canina: revisão de literatura. Rev Cient Elet Med Vet 2012; 10(19): 1-17.

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 2011; 28(10): 2731-2739. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msr121 PMid:21546353.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msr121 - Tartarotti AL, Donini MA, Anjos C, Ramos RR. Leishmaniose Visceral no Rio Grande do Sul - Vigilância de reservatórios caninos. Bol Epidemiol 2011; 13(1): 3-6.

- Thomaz-Soccol V, Castro EA, Navarro IT, Farias MR, Souza LM, Carvalho Y, et al. Casos alóctones de leishmaniose visceral canina no Paraná, Brasil: implicações epidemiológicas. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2009; 18(3): 46-51. http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbpv.01803008 PMid:19772775.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbpv.01803008 - Thomaz-Soccol V, Lanotte G, Rioux JA, Pratlong F, Martini-Dumas A, Serres E. Phylogenetic taxonomy of new world Leishmania. Ann Parasitol Hum Comp 1993; 68(2): 104-106. PMid:7692803.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

04 Nov 2019 -

Date of issue

2020

History

-

Received

10 July 2019 -

Accepted

12 Sept 2019