Abstract

There is great diversity in swine coccidia, which are responsible for causing intestinal disorders ranging from sporadic diarrhea to severe cases of hemorrhagic enteritis. Thus, determining the species of coccidia that affect the animals of a region and associating them with the characteristics of the farms become extremely important. The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of coccidia parasites in pigs reared in a family farming production system in the Semiarid Region of the State of Paraíba, Northeast Brazil. Fecal samples for analysis were collected from 187 pigs on 51 farms. For morphological analysis, 1,590 sporulated oocysts were used. The prevalence of oocysts in fecal samples was 56.6% (106/187). The most prevalent species were Eimeria suis (21.9%), followed by Eimeria neodebliecki (16.6%), Eimeria perminuta (14.9%), Eimeria polita (12.8%), Eimeria debliecki (10.6%), Eimeria porci (10.1%), Cystoisospora suis (3.7%), Eimeria scabra (1.6%) and Eimeria cerdonis (0.5%). It can be concluded that pigs from the Semiarid Region of the State of Paraíba were parasitized by a diversity of coccidia species, mainly of the genus Eimeria, and predominantly presented with mixed infections occurring in the subclinical form.

Keywords:

Cystoisospora; Eimeria; swine; family farming

Resumo

Há uma grande diversidade de coccídios que parasitam os suínos, sendo responsáveis por causarem desordens intestinais que variam de diarreias esporádicas a casos severos de enterites hemorrágicas. Assim, determinar as espécies de coccídios que afetam os animais de uma região e associá-los com as características das fazendas torna-se extremamente importante. Objetivou-se determinar a prevalência de coccídios em suínos criados em sistema de produção de agricultura familiar no Semiárido da Paraíba, Nordeste do Brasil. Foram analisados oocistos íntegros e esporulados no período de março a setembro de 2018, oriundos de 187 suínos, em 51 propriedades. Para a análise morfológica foram utilizados 1.590 oocistos esporulados. A prevalência de oocistos de coccídios foi detectada em 56,6% (106/187) das amostras analisadas. A espécie mais prevalente foi Eimeria suis (21,9%), seguida por Eimeria neodebliecki (16,6%), Eimeria perminuta (14,9%), Eimeria polita (12,8%), Eimeria debliecki (10,6%), Eimeria porci (10,1%), Cystoisospora suis (3,7%), Eimeria scabra (1,6%) e Eimeria cerdonis (0,5%). Concluiu-se que os suínos do Semiárido da Paraíba estavam parasitados por uma alta diversidade de espécies de coccídios, principalmente do gênero Eimeria, apresentando predominantemente infeções mistas, que ocorrem sob a forma subclínica.

Palavras-chave:

Cystoisospora; Eimeria; suínos; agricultura familiar

Introduction

Pig production in Brazil is increasing annually, reaching 3,600 tons in 2015 (ABPA, 2017Associação Brasileira de Proteção Animal – ABPA. [online]. 2017 [cited 2018 Jun 26]. Available from: http://abpa-br.com.br/storage/files/relatorio-anual-2018.pdf

http://abpa-br.com.br/storage/files/rela...

) and, because of this growth, the Brazilian pork industry is becoming a realistic alternative in job creation and income generation for farmers. This is a competitive industry, placing the country among the four largest pork producers and exporters in the world (Fontes et al., 2014Fontes OD, Abreu TLM, Neta SSC. Nutrição e alimentação da fêmea suína lactante e desmamada: exigências nutricionais da fêmea suína lactante. In: Associação Brasileira de Criadores de Suínos – ABCS. Produção de suínos – teoria e prática. Brasília: ABCS; 2014. p. 507-517.; SEBRAE, 2016Serviço Brasileiro de Apoio às Micro e Pequenas Empresas – SEBRAE & Associação Brasileira de Criadores de Suínos – ABCS. Mapeamento da suinocultura brasileira: Mapping of Brazilian Pork Chain [online]. Brasília: SEBRAE/ABCS; 2016 [cited 2018 Nov 30]. Available from: https://www.embrapa.br/documents/1355242/0/Mapeamento+da+Suinocultura+Brasileira.pdf

https://www.embrapa.br/documents/1355242...

).

In the Northeastern of Brazil, swine rearing, even in precarious and adverse situations, provides excellent quality animal protein and income to its breeders (Silva, 2008Silva OL Fa. Experiências brasileiras na criação de suínos locais, La Habana. Rev Comput Prod Porc 2008; 15: 41-53.), alleviates hunger, and is considered a tool to combat poverty in rural and peri-urban communities in developing countries (FAO, 2012Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations – FAO. Animal production and health livestock countries review: pig sector Kenya [online]. Rome: FAO; 2012 [cited 2016 Jul 17]. Available from: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i2566e.pdf

http://www.fao.org/3/a-i2566e.pdf...

; Nsadha, 2013Nsadha Z. Porcine diseases of economic and public health importance in Uganda: review of successes and failures in disease control and interventions [online]. Nairobi, Quênia: International Livestock Research Institute; 2013 [cited 2017 Aug 24]. Available from: http://livestockfish.cgiar.org

http://livestockfish.cgiar.org...

). However, the wide variation in production systems, the lack of environmental hygiene and the non-selective feeding behavior of the animals have been identified as important risk factors for endoparasitic swine infection, which can range from mild diarrhea to fatal hemorrhagic enteritis (Tomass et al., 2013Tomass Z, Imam E, Kifleyohannes T, Tekle Y, Weldu K. Prevalence of gastrointestinal parasites and Cryptosporidium species in extensively managed pigs in Mekelle and urban areas of southern zone of Tigray region, Northern Ethiopia. Vet World 2013; 6(7): 433-439. http://dx.doi.org/10.5455/vetworld.2013.433-439.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5455/vetworld.2013....

).

Enteric coccidia are considered to be important etiological agents of diarrhea in suckling piglets (Holm, 2001Holm A. Coccidiosis in piglets seen from the point of view of the practising veterinarian. Parasitol Res 2001; 87(4): 357-359. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/PL00008593. PMid:11355690.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/PL00008593...

; Martineau & del Castillo, 2000Martineau GP, del Castillo J. Epidemiological, clinical and control investigations on field porcine coccidiosis: clinical, epidemiological and parasitological paradigms? Parasitol Res 2000; 86(10): 834-837. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/PL00008509. PMid:11068816.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/PL00008509...

; Meyer et al., 1999Meyer C, Joachim A, Daugschies A. Occurrence of Isospora suis in larger piglet production units and on specialized piglet rearing farms. Vet Parasitol 1999; 82(4): 277-284. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(99)00027-8. PMid:10384903.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(99)...

; Mundt et al., 2006Mundt HC, Joachim A, Becka M, Daugschies A. Isospora suis: an experimental model for mammalian intestinal coccidiosis. Parasitol Res 2006; 98(2): 167-175. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-005-0030-x. PMid:16323027.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-005-003...

; Niestrath et al., 2002Niestrath M, Takla M, Joachim A, Daugschies A. The role of Isospora suis as a Pathogen in Conventional Piglet Production in Germany. J Vet Med Ser B 2002; 49(4): 176-180. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1439-0450.2002.00459.x. PMid:12069269.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1439-0450.20...

; Weng et al., 2005Weng YB, Hu YJ, Li Y, Li BS, Lin RQ, Xie DH, et al. Survey of intestinal parasites in pigs from intensive farms in Guangdong Province, People’s Republic of China. Vet Parasitol 2005; 127(3-4): 333-336. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.09.030. PMid:15710534.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004....

; Zhang et al., 2012Zhang WJ, Xu LH, Liu YY, Xiong BQ, Zhang QL, Li FC, et al. Prevalence of coccidian infection in suckling piglets in China. Vet Parasitol 2012; 190(1-2): 51-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.05.015. PMid:22694832.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2012....

).

Cystoisospora suis causes severe disease in suckling piglets, resulting in diarrhea and dehydration, especially in animals aged 2 to 4 weeks (Mundt et al., 2005Mundt HC, Cohnen A, Daugschies A, Joachim A, Prosl H, Schmaschke R, et al. Occurrence of Isospora suis in Germany, Switzerland and Austria. J Vet Med B Infect Dis Vet Public Health 2005; 52(2): 93-97. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0450.2005.00824.x. PMid:15752269.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0450.20...

). It is suspected that species of the genus Eimeria have low pathogenicity (Rommel, 1992Rommel M. Parasitosen des Schweines, protozoen. In: Eckert J, Kutzer E, Rommel M, Bürger HJ, Körting W, editors. Veterinärmedizinische parasitologie. 4th ed. Berlin: Paul Parey; 1992. p. 444–458.), although some species as Eimeria suis, Eimeria polita and Eimeria spinosa, may cause clinical signs such as fever, diarrhea and weight loss in young weaned piglets (Jones et al., 1985Jones GW, Parker RJ, Parke CR. Coccidia associated with enteritis in grower pigs. Aust Vet J 1985; 62(9): 319. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-0813.1985.tb14917.x. PMid:4074221.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-0813.19...

; Lindsay et al., 2002Lindsay DS, Neiger R, Hildreth M. Porcine enteritis associated with Eimeria spinosa Henry, 1931 infection. J Parasitol 2002; 88(6): 1262-1263. http://dx.doi.org/10.1645/0022-3395(2002)088[1262:PEAWES]2.0.CO;2. PMid:12539745.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1645/0022-3395(2002...

; Matsubayashi et al., 2016Matsubayashi M, Takayama H, Kusumoto M, Murata M, Uchiyama Y, Kaji M, et al. First report of molecular identification of Cystoisospora suis in piglets with lethal diarrhea in Japan. Acta Parasitol 2016; 61(2): 406-411. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/ap-2016-0054. PMid:27078667.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/ap-2016-0054...

). For this reason, Sharma et al. (2018)Sharma D, Singh NK, Singh H, Joachim A, Rath SS, Blake DP. Discrimination, molecular characterisation and phylogenetic comparison of porcine Eimeria spp. in India. Vet Parasitol 2018; 255: 43-48. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2018.03.020. PMid:29773135.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2018....

stated that species identification is important in determining which organisms cause an outbreak or circulate on a farm. The morphology of sporulated oocysts reveals characteristics that can be described qualitatively and quantitatively, with wide variations and combinations of specific characteristics (Long & Joyner, 1984Long PL, Joyner LP. Problems in the identification of species of Eimeria. J Protozool 1984; 31(4): 535-541. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.1984.tb05498.x. PMid:6392531.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.19...

; Carvalho et al., 2004Carvalho PR Fo, Massad FV, Lopes CWG, Teixeira WL, Oliveira FCR. Identificação e comparação de espécies do gênero Eimeria Schneider, 1875 (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) oriundas de suínos através de um algoritmo morfológico. Rev Bras Cienc Vet 2004; 11(3): 156-159. http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbcv.2014.362.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbcv.2014.362...

).

With swine production increasing in small and medium farms in the Brazilian Semiarid Region, guaranteeing an extra income to family farmers in the region, it was necessary to increase knowledge about the main enteric coccidia that affect swine. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of swine coccidian infections by analyzing the association between the presence of infection and the characteristics of the farms and to identify the swine coccidia species in the Semiarid Region of Northeastern Brazil.

Material and Methods

Study location

This study was performed in the Sousa Microregion, Paraíba, Northeast Brazil. The area belongs to the Caatinga biome. The climate is characterized as warm and semiarid, with average temperatures of 27°C throughout the year and annual average rainfall of typically 500 mm. There are usually two seasons: a rainy season from February to May and a long dry season from June to January, occasionally lasting more than one year (INMET, 2010Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia – INMET. Normais climatológicas do Brasil 1981-2010 [online]. 2010 [cited 2018 Nov 27]. Available from: <http://www.inmet.gov.br/portal/index.php?r=clima/normaisClimatologicas

http://www.inmet.gov.br/portal/index.php...

).

The State of Paraíba is divided into four mesoregions: Sertão, Borborema, Agreste, and Mata Paraibana. These define an area known as the Sertão (Hinterland) which is formed by the union of 83 municipalities grouped in seven microregions as followed: Cajazeiras, Catolé do Rocha, Itaporanga, Patos, Piancó, Serra do Teixeira and Sousa, totaling an area of 22,720,482 km2 (IBGE, 2009Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE. [online]. 2009 [cited 2018 Apr 15]. Available from: http://www.ibge.gov.br

http://www.ibge.gov.br...

).

The study was conducted from February to December 2018. Farms were studied distributed over 11 Municipalities of the Microregion of Sousa: Aparecida, Marizopolis, Nazarezinho, Paulista, Pombal, Santa Cruz, Sousa, São Francisco, São Jose da Lagoa Tapada, Vieirópolis and Vista Serrana (Figure 1).

Georeferencing of family farming studied in the Sousa Microregion in the Paraíba Semiarid Region of Northeastern Brazil.

Calculation for sampling

The study had a cross-sectional design, and sampling was designed to determine the prevalence of positive farms (foci), being performed in two steps: (1) A random selection from a pre-established number of farms was made (primary units); (2) Within the primary units, a predetermined number of pigs (secondary units) were randomly sampled.

To calculate the number of primary units to be sampled, the following parameters were considered: (a) expected prevalence; (b) absolute error; and (c) confidence level according to the formula for simple random samples (Thrusfield, 2007Thrusfield M. Veterinary epidemiology. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2007.):

In which:

n = number of farms sampled

Z = normal distribution value for 95% confidence level

P = expected prevalence of 82.76% (Santos et al., 2006Santos WB, Ahid SMM, Suassuna ACD. Aspectos epidemiológicos da caprinocultura e ovinocultura no munícipio de Mossoró (RN). Hora Vet 2006; 26(152): 25-28.).

d = absolute error of 5%

For the adjustment for finite populations, the following formula was used (Thrusfield, 2007Thrusfield M. Veterinary epidemiology. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2007.):

In which:

najus = adjusted sample size

N = total population size

n = initial sample size

According to the Paraíba State Department of Agricultural and Fisheries Development (SEDAP-PB), the Sousa microregion has 4,804 pig farms. Based on these data, the number of primary units to be visited was 51. Then the number of pigs to be selected was determined individually by herd for the presence of infection, using the following formula (Thrusfield, 2007Thrusfield M. Veterinary epidemiology. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2007.).

In which:

n - sample size

p - probability of detection of at least one infected animal

N - herd size

d - number of infected animals in the herd

The probability of detecting at least one positive animal in the herd was determined at the 95% confidence level (p = 0.95), and the number of positive animals per herd (d) was calculated assuming intra-herd prevalence of 41.3% (Ahid et al., 2008Ahid SMM, Suassuna ACD, Maia BM, Costa MMV, Soares SH. Parasitos gastrintestinais em caprinos e ovinos da Região Oeste do Rio Grande do Norte, Brasil. Cienc Anim Bras 2008; 9(1): 212-218. http://dx.doi.org/10.5216/cab.v9i1.3681.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5216/cab.v9i1.3681...

). In total, 187 pigs from 51 farms were selected by simple random sampling. A table was used to select the animals according to the number of pigs on each farm; according to the table, a minimum of two and a maximum of five animals per property were selected. After identifying and enumerating the total swine population of each property and defining the quantity to be selected, a draw was carried out and the selected numbers were included in the study. The farms visited had their geographic coordinates georeferenced, as shown in Figure 1. An age cut was not established because some selected farms had not pigs in different age groups.

Samples collected

Fecal samples were collected directly from the rectal ampoule of each animal. After collection, the material was sent to the Laboratório de Parasitologia Veterinária (LPV), of the Instituto Federal da Paraíba (IFPB), campus Sousa. To determine the level of oocyst shedding, oocyst counts per gram (OoPG) of feces were performed individually, according to Gordon & Withlock (1939)Gordon HM, Withlock HV. A new tecnique for counting nematode eggs in sheep faeces. J Counc Sci Ind Res 1939; 12(1): 50-52..

Fecal samples were individually diluted in a 2.5% aqueous potassium dichromate solution (K2Cr2O7) and placed in Petri dishes containing 1/6 stool to 5/6 solution and left at room temperature for 15 days for the oocysts sporulation (Santos & Lopes, 1994Santos NM, Lopes CWG. Diagnóstico da coccidiose suína relacionado ao manejo e idade dos animais. Rev Bras Ciên Vet 1994; 1(1): 17-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbcv.2015.005.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbcv.2015.005...

).

In order to determine the presence of coccidian oocysts, after sporulation of the oocysts, the samples were placed in 50 mL centrifuge tubes and centrifuged at least four times for 10 minutes with a gravitational force of 1050xg until completely clear. The resulting pellet was suspended by centrifugal floatation in saturated sucrose solution (500g sucrose, 350 ml tap water, 5 mL phenol), according to Sheather (1923)Sheather AL. The detection of intestinal protozoa and mange parasites by a flotation technique. J Comp Pathol Ther 1923; 36: 266-275. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0368-1742(23)80052-2.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0368-1742(23)...

and modified by Duszynski & Wilber (1997)Duszynski DW, Wilber PG. A guideline for the preparation of species descriptions in the Eimeriidae. J Parasitol 1997; 83(2): 333-336. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3284470. PMid:9105325.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3284470...

. After centrifugation, the centrifuge tube was filled with saturated sucrose solution until a converging meniscus was formed, on which a 24 x 32 mm cover slip was placed and left for a period of 10 minutes. After this period, the coverslip was removed and placed on a previously degreased and dried slide for coccidia visualization.

For morphometric analysis, the LAB-DM300-optical biological microscope with digital technology and a 3.0 million-pixel camera with 3.2 million pixels with integrated software were used. The technology with an intuitive USB interface allowed photographing, capturing, making edits and measurements with very high precision, with a 10X, 40X and 100X Objs, planachromatic lens.

Fifteen sporulated oocysts of each positive animal were photographed for morphometric analysis that allowed the identification of the species and the determination of prevalence.

Only sporulated and intact oocysts of species of the genera Eimeria and Cystoisospora were measured. The length and width were measured, and the shape index (SI) of the oocysts and sporocysts was calculated, as well as the thickness of the oocyst outer layer and the presence or absence of internal morphological structures as exemplified in Berto et al. (2014)Berto BP, McIntosh D, Lopes CW. Studies on coccidian oocysts (Apicomplexa: eucoccidiorida). Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2014; 23(1): 1-15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612014001. PMid:24728354.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612014...

. The evaluation of the mean, lower limit, upper limit, standard deviation and coefficient of variation (CV) of coccidia oocysts and their sporocysts was performed using the Excel software, Office 2010.

The classification of recovered oocyst species was based on morphometric characteristics, highlighted by Vetterling (1965)Vetterling JM. Coccidia (Protozoa: Eimeriidae) of swine. J Parasitol 1965; 51(6): 897-912. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3275867. PMid:5848816.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3275867...

, and the morphological characteristics of sporulated oocysts was indicated by Daugschies et al. (2004)Daugschies A, Imarom S, Ganter M, Bollwahn W. Prevalence of Eimeria spp. in sows at piglet-producting farms in Germany. J Vet Med Ser B 2004; 51(3): 135-139. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0450.2004.00734.x. PMid:15107040.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0450.20...

.

The Research Ethics Committee of IFPB authorized all the procedures performed in this study (protocol # 23000.001538.2017-93).

Results

The prevalence of pig coccidia in the Sousa Microregion was 56.6% (106/187). After sporulation, it was found that 93.4% (99/106) of swine were parasitized by species of the genus Eimeria and 6.6% (7/106) presented with mixed infection with Eimeria spp. and C. suis. It was also noted that at least one animal was positive for coccidia in 64.7% (33/51) of the inspected farms.

During evaluation of the levels of oocyst shedding, the predominance of low excretion (OoPG<300) was noted, occurring in 85.8% of swine (91/106).

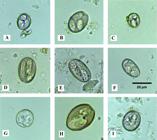

Based on the morphological and morphometric characteristics of 1.590 sporulated intact oocysts, eight species of the genus Eimeria and one of the genus Cystoisospora were identified as: E. suis Nöller 1921, (Figure 2A); Eimeria neodebliecki Vetterling 1965, (Figure 2B); Eimeria perminuta Henry 1931, (Figure 2C); E. polita Pellérdy 1949, (Figure 2D); Eimeria debliecki Douwes 1921, (Figure 2E); Eimeria porci Vetterling 1965, (Figure 2F); C. suis Biester 1934 (syn. Isospora suis), (Figure 2G); Eimeria scabra Henry 1931, (Figure 2H) and Eimeria cerdonis Vetterling 1965, (Figure 2I).

Fotomicrography of sporulated oocysts of coccidia in swine of family farming from the Paraíba Semiarid Region of Northeastern Brazil. A, Eimeria porci, B, Eimeria polita, C, Eimeria debliecki, D, Eimeria scabra, E, Eimeria neodebliecki, F, Eimeria suis, G, Eimeria perminuta, H, Eimeria cerdonis, I, Cystoisospora suis. Sheather’s Saturated sugar solution. Obj. 40X.

The most prevalent species were E. suis, followed by E. neodebliecki, E. perminuta, E. polita, E. debliecki, E. porci, C. suis, E. scabra and E. cerdonis respectively (Table 1).

Oocyst morphometry and prevalence of coccidia species in swine from the Paraiba Semiarid Region of Northeastern Brazil.

The species identified in this study were described below:

-

Eimeria suis (Figure 2A). Ellipsoidal oocysts; smooth outer layer, 0.5 µm thick; missing micropyle, polar granule present; sporulated oocysts measured 15 (12 - 19) by 13 (11 - 15) µm, with a shape index of 1.25. Four sporocysts present in the oocysts, residuum missing; Slightly elongated ovoid sporocysts with two sporozoites, Stieda body present; sporocysts measured 10 (8 - 13) by 5 (5 - 6) µm.

-

Eimeria neodebliecki (Figure 2B). Ellipsoidal oocysts, rarely ovoid; smooth outer layer, 0.8 µm thick; missing micropyle, polar granule present (seen in all observed oocysts); sporulated oocysts measured 22 (20 - 25) by 16 (14 - 19) µm, with a shape index of 1.22. Four sporocyst present in the oocysts, missing residuum; elongated sporocysts or ovoids with two sporozoites, roughly granular residue and Stieda body present; sporocysts measured 12 (11 - 14) by 5 (4 - 7).

-

Eimeria perminuta (Figure 2C). Spherical oocysts; rough outer layer, 1.1 µm in thickness; missing micropyle, polar granule present; sporulated oocysts measured 14 (11 - 18) by 12 (10 - 15) µm, with a shape index of 1.22. Four sporocyst present in the oocysts, residuum missing; ellipsoidal sporocysts with two sporozoites, and Stieda body present; sporocysts measured 7 (6 - 9) by 5 (5 - 7) µm.

-

Eimeria polita (Figure 2D). Elliptical but sometimes ovoid oocysts with rough outer layer; polar granule present (observed in all oocysts); sporulated oocysts measured 24 (18 - 26) by 17 (14 - 19) µm, with a shape index of 1.39. Oocysts containing four, missing residuum; sporocysts ovoid that measured 13 (8 - 18.5) µm and a width of 6 (4.9 - 9.5) µm.

-

Eimeira debliecki (Figure 2E). Ellipsoidal and rarely ovoid oocysts; smooth outer layer, 1.1 µm thick; missing micropyle, polar granule present (observed in all oocysts); sporulated oocysts measured 25 (20 - 29) by 13 (12 - 16) µm, with a shape index of 1.57. Oocysts containing four sporocysts, missing residuum; elongated ovoid sporocysts, with two sporozoites, Stieda body present; sporocysts measured from 17 (14 - 21) by 4 (3 - 5) µm.

-

Eimeria porci (Figure 2F). Plain, colorless ovoid oocysts, two layers, 0.89 µm thick; missing micropyle, polar granule present (observed in all oocysts); sporulated oocysts measured 23 (18 - 27) by 14 (13 - 15) µm, with a shape index of 1.76. Oocysts containing four sporocysts, missing residuum; ovoid sporocysts, Stieda body visualized; 138 sporocysts measured 10 (9 - 12) by 8 (6 - 9) µm.

-

Cystoisospora suis (Figure 2G). Spherical oocysts; smooth outer layer, 0.5 to 0.8 µm thick; missing micropyle, missing polar granules; sporulated oocysts measured 20 (17 - 22) by 13 (12 - 15) µm, with a shape index of 1.46. Oocysts with two sporocysts, missing residuum; ellipsoidal sporocysts with four sporozoites, Stieda body absent; sporocysts measured 13 (12 - 15) by 10 (9 - 12) µm; observable nucleus; sporozoites measured from 10.5 (9 - 12) by 3.9 (3.7 - 4.1) µm.

-

Eimeria scabra (Figure 2H). Ovoid oocysts, rarely ellipsoidal; yellow to brown rough outer layer, thickness 1.9 - 3.0 µm; present micropyle (observed in all sporulated oocysts),presence of polar granules (observed in all oocysts)sporulated oocysts measured from 30 (29 - 31) by 22 (21 - 23) µm, with a shape index of 1.34; oocysts with four sporocysts, missing residuum; elongated ovoid sporocysts with two sporozoites and Stieda body present; sporocysts measured from 15 (13 - 18) by 7 (7 - 10) µm.

-

Eimeria cerdonis (Figure 2I). Ellipsoidal oocysts, rarely ovoid; rough outer layer, 1.4 µm thick; missing micropyle, polar granules present; sporulated oocysts measured from 23 (21 - 25) by 19 (18 - 20), with a shape index of 1.26. Oocysts with four sporocysts, missing residuum; elongated ovoid sporocysts with two sporozoites and Stieda body present; sporocysts measured from 14 (13 - 16) by 7 (6 - 8) µm.

The descriptive analyzes of the central tendency (mean), variability (standard deviation) and relative dispersion (CV) of the oocysts and sporocysts are described in the Table 2. The oocysts lenght CVs varied between 2.9 to 17.6%, and the width between 35 to 15.1%, both for E. scabra and E. perminuta, respectively. The sporocysts length CVs ranged between 8.5% (E. cerdonis) to 26.9% (E. polita), and the width CVs ranged between 9.2% (E.suis) to 25.4% (E. neodebliecki).

Oocysts and sporocysts values in swine from the Paraiba Semiarid Region of Northeastern Brazil.

Discussion

The high prevalence of pig coccidia observed in this study (56.6%; 106/187), corroborates the results found by Sevá et al. (2018)Sevá AP, Pena HFJ, Nava A, Sousa AO, Holsback L, Soares RM. Endoparasites in domestic animals surrounding an Atlantic Forest remnant, in São Paulo State, Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2018; 27(1): 13-18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1984-29612017078. PMid:29641793.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1984-29612017...

, in subsistence breeding pigs in the Municipality of Teodoro Sampaio in the State of São Paulo, Brazil, which reported prevalence of coccidial oocysts in 60% of the studied pigs. Similar studies should be included here (Santos & Lopes, 1994Santos NM, Lopes CWG. Diagnóstico da coccidiose suína relacionado ao manejo e idade dos animais. Rev Bras Ciên Vet 1994; 1(1): 17-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbcv.2015.005.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbcv.2015.005...

) On the other hand, lower prevalence was obtained by Kouam et al. (2018)Kouam MK, Ngueguim FD, Kantzoura V. Internal parasites of pigs and worm control practices in Bamboutos, Western Highlands of Cameroon. J Parasitol Res 2018; 2018: 8242486. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2018/8242486. PMid:30584473.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2018/8242486...

, in Bamboutos in the Republic of Cameroon, a region that has a typical climate similar to that in the Semiarid Region of Northeastern Brazil, with two main seasons, dry and rainy, in which 26.9% of pigs had coccidia infections. This lower prevalence was due to a prophylaxis program adopted in 49 of the 50 farms sampled in that study, which consisted of general hygiene, use of pharmaceuticals, and having a veterinarian as swine health officer on most farms; actions that significantly reduced the overall burden of oocysts.

In the morphological evaluation of the sporulated oocysts, the genera Eimeria and Cystoisospora were identified in 64.7% (33/51) of the visited family farming. This result was similar to that found in Bangladesh by Dey et al. (2014)Dey TR, Dey AR, Begum N, Akther S, Barmon BC. Prevalence of end parasitesof pig at Mymensingh, Bangladesh. J Agric Veter Sci 2014; 7(4): 31-38. http://dx.doi.org/10.9790/2380-07433138.

http://dx.doi.org/10.9790/2380-07433138...

, who reported a prevalence of 65.5% of Eimeria spp. and C. suis. Ózsvári (2018)Ózsvári L. Production impact of parasitisms and coccidiosis in swine. J Dairy Vet Anim Res 2018; 7(5): 217-222. http://dx.doi.org/10.15406/jdvar.2018.07.00214.

http://dx.doi.org/10.15406/jdvar.2018.07...

, in a bibliographic study of research conducted mainly in Western Europe, revealed that coccidiosis was present in 76% of piggeries, stating that between 40 and 100% of piglets on a farm may be infected and only good hygienic practices will not serve to reduce the high loads of oocysts.

In our study, the majority of pigs positive for coccidia had mainly low oocyst shedding (85.8%; 91/106). Despite of the low excretion, adult pigs eliminated oocysts with an infectious capacity, functioning as important reservoirs and maintainers of coccidiosis in herds. Bangoura & Daugschies (2017)Bangoura B, Daugschies A. Eimeria. In: Florin-Christensen M, Schnittger L. Parasitic protozoa of farm animals and pets. Heidelberg: Springer Nature; 2017. p. 55-101. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70132-5_3.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70132-...

reported that clinical coccidiosis accounts for a relatively small proportion of economic losses and those subclinical infections are considered to cause the greatest economic damage. This author, further stated that due to the rapid spread of these pathogens in a herd and the high durability of oocysts, which leads to long-term survival of infectious oocysts in the environment, coccidiosis becomes a continuing threat to animal health and an economic burden on the farmer. However, he emphasized that it is possible to reduce this impact by performing tests to identify coccid species, using specific drugs for effective treatment, and adopting hygiene and management measures correctly.

The most prevalence species were E. suis and E. neodebliecki. Seven pigs had simultaneous infections by Eimeria spp. and C. suis. According to Vetterling (1965)Vetterling JM. Coccidia (Protozoa: Eimeriidae) of swine. J Parasitol 1965; 51(6): 897-912. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3275867. PMid:5848816.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3275867...

, the most prevalent species in swine in the USA was E. neodebliecki. According to Das et al. (2019)Das M, Laha R, Khargharia G, Sen A. Coccidiosis in pigs of subtropical hilly region of Meghalaya, India. J Entomol Zool Stud 2019; 7(2): 1185-1189., variations in the percentage prevalence of different Eimeria spp. vary according to the age of the animals and the geographical location. The prevalence of C. suis found in our study was 3.7% (7/ 187). This result may be related to the practices adopted by the majority of the farm owners visited, where there was negligence in hygiene and disinfection of the facilities. Sartor et al. (2007)Sartor AA, Bellato V, Souza AP, Cantelli CR. Prevalência das espécies de Eimeria Schneider, 1875 e Isospora Schneider, 1881 (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) parasitas de suínos do município de Videira, SC, Brasil. Rev Ciênc Agrovet 2007; 6(1): 38-43. state that older pigs act as carriers and disseminators of oocysts in the environment, mainly contaminating the floor and walls of the facilities where oocysts remain viable due to a deficient cleaning and disinfection regimen. Langkjær & Roepstorff (2008)Langkjær M, Roepstorff A. Survival of Isospora suis oocysts under controlled environmental conditions. Vet Parasitol 2008; 152(3-4): 186-193. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.01.006. PMid:18289796.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2008....

confirmed that it is possible to reduce the infection pressure of C. suis in modern breeding herds, by environmental changes and management within the maternity wards, thus increasing animal welfare without relying on routine medication use.

An important morphological characteristic in helping to differentiate Eimeria species is index shape (SI), which consists of dividing the length (L) by the width (W). The size of the oocyst may be variable, but its SI demonstrates a rectilinear tendency that reflects the volumetric shape of the sporulated oocysts in association with mean size, lower and upper limits, and morphological aspects of internal structures being more accurate for species comparison than the mean size, as well as for intraspecific variation (Long & Joyner, 1984Long PL, Joyner LP. Problems in the identification of species of Eimeria. J Protozool 1984; 31(4): 535-541. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.1984.tb05498.x. PMid:6392531.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.19...

; Berto et al., 2014Berto BP, McIntosh D, Lopes CW. Studies on coccidian oocysts (Apicomplexa: eucoccidiorida). Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2014; 23(1): 1-15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612014001. PMid:24728354.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612014...

; Flausino et al., 2014Flausino G, Berto BP, McIntosh D, Furtado TT, Teixeira-Filho WL, Lopes CWG. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of Eimeria caviae from Guinea Pigs (Cavia porcellus). Acta Protozool 2014; 53(3): 269-276. http://dx.doi.org/10.4467/16890027AP.14.024.1999.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4467/16890027AP.14....

).

Studies using molecular tools are already available to identify coccidia oocysts in swine, but according to Ruttkowski et al. (2001)Ruttkowski B, Joachim A, Daugschies A. PCR-based differentiation of three porcine Eimeria species and Isospora suis. Vet Parasitol 2001; 95(1): 17-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(00)00408-8. PMid:11163694.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(00)...

and Daugschies et al. (2004)Daugschies A, Imarom S, Ganter M, Bollwahn W. Prevalence of Eimeria spp. in sows at piglet-producting farms in Germany. J Vet Med Ser B 2004; 51(3): 135-139. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0450.2004.00734.x. PMid:15107040.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0450.20...

, oocyst morphology is still the most appropriate and reliable method for differentiation in epidemiological surveys. The morphometric data observed in the present study are generally consistent with previous reports (Vetterling, 1965Vetterling JM. Coccidia (Protozoa: Eimeriidae) of swine. J Parasitol 1965; 51(6): 897-912. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3275867. PMid:5848816.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3275867...

; Daugschies et al., 1999Daugschies A, Imarom S, Bollwahn W. Differentiation of porcine Eimeria spp. by morphologic algorithms. Vet Parasitol 1999; 81(3): 201-210. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(98)00246-5. PMid:10190864.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(98)...

, 2004Daugschies A, Imarom S, Ganter M, Bollwahn W. Prevalence of Eimeria spp. in sows at piglet-producting farms in Germany. J Vet Med Ser B 2004; 51(3): 135-139. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0450.2004.00734.x. PMid:15107040.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0450.20...

). However, this study was able to combine for the first time not only morphometric but also epidemiological data about swine infection by eight species from the Eimeria genus and C. suis.

The measures realized for length and width of the oocysts and sporocysts showed CVs below 30%. According to Siqueira & Tibúrcio (2011)Siqueira AL, Tibúrcio JD. Estatística na área da saúde: conceitos, metodologia, aplicações e prática computacional. Belo Horizonte: Coopmed; 2011., CVs below 10% are considered low, while above 30% are considered very high. In the present study, the CVs of the length and width of the oocysts are lower than the sporocysts, therefore more homogeneous, revealing low and medium dispersion.

Conclusion

Pigs from the semiarid region of Northeastern Brazil were highly infected with enteric coccidia, exhibiting high parasitic diversity, including eight species of the genus Eimeria and one of Cystoisospora. Low oocyst shedding occurs in most animals, favoring the maintenance and spread of infections.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior), the CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico) and the IFPB (Instituto Federal da Paraíba) for the scholarship grants.

-

How to cite: Araújo HG, Silva JT, Sarmento WF, Silva SS, Bezerra RA, Azevedo SS, et al. Diversity of enteric coccidia in pigs from the Paraíba Semiarid Region of Northeastern Brazil. Braz J Vet Parasitol 2020; 29(4): e009120. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612020079

References

- Ahid SMM, Suassuna ACD, Maia BM, Costa MMV, Soares SH. Parasitos gastrintestinais em caprinos e ovinos da Região Oeste do Rio Grande do Norte, Brasil. Cienc Anim Bras 2008; 9(1): 212-218. http://dx.doi.org/10.5216/cab.v9i1.3681

» http://dx.doi.org/10.5216/cab.v9i1.3681 - Associação Brasileira de Proteção Animal – ABPA. [online]. 2017 [cited 2018 Jun 26]. Available from: http://abpa-br.com.br/storage/files/relatorio-anual-2018.pdf

» http://abpa-br.com.br/storage/files/relatorio-anual-2018.pdf - Bangoura B, Daugschies A. Eimeria. In: Florin-Christensen M, Schnittger L. Parasitic protozoa of farm animals and pets Heidelberg: Springer Nature; 2017. p. 55-101. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70132-5_3

» https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70132-5_3 - Berto BP, McIntosh D, Lopes CW. Studies on coccidian oocysts (Apicomplexa: eucoccidiorida). Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2014; 23(1): 1-15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612014001 PMid:24728354.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612014001 - Carvalho PR Fo, Massad FV, Lopes CWG, Teixeira WL, Oliveira FCR. Identificação e comparação de espécies do gênero Eimeria Schneider, 1875 (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) oriundas de suínos através de um algoritmo morfológico. Rev Bras Cienc Vet 2004; 11(3): 156-159. http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbcv.2014.362

» http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbcv.2014.362 - Das M, Laha R, Khargharia G, Sen A. Coccidiosis in pigs of subtropical hilly region of Meghalaya, India. J Entomol Zool Stud 2019; 7(2): 1185-1189.

- Daugschies A, Imarom S, Bollwahn W. Differentiation of porcine Eimeria spp. by morphologic algorithms. Vet Parasitol 1999; 81(3): 201-210. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(98)00246-5 PMid:10190864.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(98)00246-5 - Daugschies A, Imarom S, Ganter M, Bollwahn W. Prevalence of Eimeria spp. in sows at piglet-producting farms in Germany. J Vet Med Ser B 2004; 51(3): 135-139. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0450.2004.00734.x PMid:15107040.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0450.2004.00734.x - Dey TR, Dey AR, Begum N, Akther S, Barmon BC. Prevalence of end parasitesof pig at Mymensingh, Bangladesh. J Agric Veter Sci 2014; 7(4): 31-38. http://dx.doi.org/10.9790/2380-07433138

» http://dx.doi.org/10.9790/2380-07433138 - Duszynski DW, Wilber PG. A guideline for the preparation of species descriptions in the Eimeriidae. J Parasitol 1997; 83(2): 333-336. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3284470 PMid:9105325.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3284470 - Flausino G, Berto BP, McIntosh D, Furtado TT, Teixeira-Filho WL, Lopes CWG. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of Eimeria caviae from Guinea Pigs (Cavia porcellus). Acta Protozool 2014; 53(3): 269-276. http://dx.doi.org/10.4467/16890027AP.14.024.1999

» http://dx.doi.org/10.4467/16890027AP.14.024.1999 - Fontes OD, Abreu TLM, Neta SSC. Nutrição e alimentação da fêmea suína lactante e desmamada: exigências nutricionais da fêmea suína lactante. In: Associação Brasileira de Criadores de Suínos – ABCS. Produção de suínos – teoria e prática Brasília: ABCS; 2014. p. 507-517.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations – FAO. Animal production and health livestock countries review: pig sector Kenya [online]. Rome: FAO; 2012 [cited 2016 Jul 17]. Available from: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i2566e.pdf

» http://www.fao.org/3/a-i2566e.pdf - Gordon HM, Withlock HV. A new tecnique for counting nematode eggs in sheep faeces. J Counc Sci Ind Res 1939; 12(1): 50-52.

- Holm A. Coccidiosis in piglets seen from the point of view of the practising veterinarian. Parasitol Res 2001; 87(4): 357-359. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/PL00008593 PMid:11355690.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/PL00008593 - Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE. [online]. 2009 [cited 2018 Apr 15]. Available from: http://www.ibge.gov.br

» http://www.ibge.gov.br - Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia – INMET. Normais climatológicas do Brasil 1981-2010 [online]. 2010 [cited 2018 Nov 27]. Available from: <http://www.inmet.gov.br/portal/index.php?r=clima/normaisClimatologicas

» http://www.inmet.gov.br/portal/index.php?r=clima/normaisClimatologicas - Jones GW, Parker RJ, Parke CR. Coccidia associated with enteritis in grower pigs. Aust Vet J 1985; 62(9): 319. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-0813.1985.tb14917.x PMid:4074221.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-0813.1985.tb14917.x - Kouam MK, Ngueguim FD, Kantzoura V. Internal parasites of pigs and worm control practices in Bamboutos, Western Highlands of Cameroon. J Parasitol Res 2018; 2018: 8242486. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2018/8242486 PMid:30584473.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2018/8242486 - Langkjær M, Roepstorff A. Survival of Isospora suis oocysts under controlled environmental conditions. Vet Parasitol 2008; 152(3-4): 186-193. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.01.006 PMid:18289796.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.01.006 - Lindsay DS, Neiger R, Hildreth M. Porcine enteritis associated with Eimeria spinosa Henry, 1931 infection. J Parasitol 2002; 88(6): 1262-1263. http://dx.doi.org/10.1645/0022-3395(2002)088[1262:PEAWES]2.0.CO;2 PMid:12539745.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1645/0022-3395(2002)088[1262:PEAWES]2.0.CO;2 - Long PL, Joyner LP. Problems in the identification of species of Eimeria. J Protozool 1984; 31(4): 535-541. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.1984.tb05498.x PMid:6392531.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.1984.tb05498.x - Martineau GP, del Castillo J. Epidemiological, clinical and control investigations on field porcine coccidiosis: clinical, epidemiological and parasitological paradigms? Parasitol Res 2000; 86(10): 834-837. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/PL00008509 PMid:11068816.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/PL00008509 - Matsubayashi M, Takayama H, Kusumoto M, Murata M, Uchiyama Y, Kaji M, et al. First report of molecular identification of Cystoisospora suis in piglets with lethal diarrhea in Japan. Acta Parasitol 2016; 61(2): 406-411. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/ap-2016-0054 PMid:27078667.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/ap-2016-0054 - Meyer C, Joachim A, Daugschies A. Occurrence of Isospora suis in larger piglet production units and on specialized piglet rearing farms. Vet Parasitol 1999; 82(4): 277-284. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(99)00027-8 PMid:10384903.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(99)00027-8 - Mundt HC, Cohnen A, Daugschies A, Joachim A, Prosl H, Schmaschke R, et al. Occurrence of Isospora suis in Germany, Switzerland and Austria. J Vet Med B Infect Dis Vet Public Health 2005; 52(2): 93-97. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0450.2005.00824.x PMid:15752269.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0450.2005.00824.x - Mundt HC, Joachim A, Becka M, Daugschies A. Isospora suis: an experimental model for mammalian intestinal coccidiosis. Parasitol Res 2006; 98(2): 167-175. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-005-0030-x PMid:16323027.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-005-0030-x - Niestrath M, Takla M, Joachim A, Daugschies A. The role of Isospora suis as a Pathogen in Conventional Piglet Production in Germany. J Vet Med Ser B 2002; 49(4): 176-180. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1439-0450.2002.00459.x PMid:12069269.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1439-0450.2002.00459.x - Nsadha Z. Porcine diseases of economic and public health importance in Uganda: review of successes and failures in disease control and interventions [online]. Nairobi, Quênia: International Livestock Research Institute; 2013 [cited 2017 Aug 24]. Available from: http://livestockfish.cgiar.org

» http://livestockfish.cgiar.org - Ózsvári L. Production impact of parasitisms and coccidiosis in swine. J Dairy Vet Anim Res 2018; 7(5): 217-222. http://dx.doi.org/10.15406/jdvar.2018.07.00214

» http://dx.doi.org/10.15406/jdvar.2018.07.00214 - Rommel M. Parasitosen des Schweines, protozoen. In: Eckert J, Kutzer E, Rommel M, Bürger HJ, Körting W, editors. Veterinärmedizinische parasitologie 4th ed. Berlin: Paul Parey; 1992. p. 444–458.

- Ruttkowski B, Joachim A, Daugschies A. PCR-based differentiation of three porcine Eimeria species and Isospora suis. Vet Parasitol 2001; 95(1): 17-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(00)00408-8 PMid:11163694.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(00)00408-8 - Santos NM, Lopes CWG. Diagnóstico da coccidiose suína relacionado ao manejo e idade dos animais. Rev Bras Ciên Vet 1994; 1(1): 17-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbcv.2015.005

» http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbcv.2015.005 - Santos WB, Ahid SMM, Suassuna ACD. Aspectos epidemiológicos da caprinocultura e ovinocultura no munícipio de Mossoró (RN). Hora Vet 2006; 26(152): 25-28.

- Sartor AA, Bellato V, Souza AP, Cantelli CR. Prevalência das espécies de Eimeria Schneider, 1875 e Isospora Schneider, 1881 (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) parasitas de suínos do município de Videira, SC, Brasil. Rev Ciênc Agrovet 2007; 6(1): 38-43.

- Serviço Brasileiro de Apoio às Micro e Pequenas Empresas – SEBRAE & Associação Brasileira de Criadores de Suínos – ABCS. Mapeamento da suinocultura brasileira: Mapping of Brazilian Pork Chain [online]. Brasília: SEBRAE/ABCS; 2016 [cited 2018 Nov 30]. Available from: https://www.embrapa.br/documents/1355242/0/Mapeamento+da+Suinocultura+Brasileira.pdf

» https://www.embrapa.br/documents/1355242/0/Mapeamento+da+Suinocultura+Brasileira.pdf - Sevá AP, Pena HFJ, Nava A, Sousa AO, Holsback L, Soares RM. Endoparasites in domestic animals surrounding an Atlantic Forest remnant, in São Paulo State, Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2018; 27(1): 13-18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1984-29612017078 PMid:29641793.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1984-29612017078 - Sharma D, Singh NK, Singh H, Joachim A, Rath SS, Blake DP. Discrimination, molecular characterisation and phylogenetic comparison of porcine Eimeria spp. in India. Vet Parasitol 2018; 255: 43-48. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2018.03.020 PMid:29773135.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2018.03.020 - Sheather AL. The detection of intestinal protozoa and mange parasites by a flotation technique. J Comp Pathol Ther 1923; 36: 266-275. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0368-1742(23)80052-2

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0368-1742(23)80052-2 - Silva OL Fa. Experiências brasileiras na criação de suínos locais, La Habana. Rev Comput Prod Porc 2008; 15: 41-53.

- Siqueira AL, Tibúrcio JD. Estatística na área da saúde: conceitos, metodologia, aplicações e prática computacional Belo Horizonte: Coopmed; 2011.

- Thrusfield M. Veterinary epidemiology 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2007.

- Tomass Z, Imam E, Kifleyohannes T, Tekle Y, Weldu K. Prevalence of gastrointestinal parasites and Cryptosporidium species in extensively managed pigs in Mekelle and urban areas of southern zone of Tigray region, Northern Ethiopia. Vet World 2013; 6(7): 433-439. http://dx.doi.org/10.5455/vetworld.2013.433-439

» http://dx.doi.org/10.5455/vetworld.2013.433-439 - Vetterling JM. Coccidia (Protozoa: Eimeriidae) of swine. J Parasitol 1965; 51(6): 897-912. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3275867 PMid:5848816.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3275867 - Weng YB, Hu YJ, Li Y, Li BS, Lin RQ, Xie DH, et al. Survey of intestinal parasites in pigs from intensive farms in Guangdong Province, People’s Republic of China. Vet Parasitol 2005; 127(3-4): 333-336. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.09.030 PMid:15710534.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.09.030 - Zhang WJ, Xu LH, Liu YY, Xiong BQ, Zhang QL, Li FC, et al. Prevalence of coccidian infection in suckling piglets in China. Vet Parasitol 2012; 190(1-2): 51-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.05.015 PMid:22694832.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.05.015

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

09 Oct 2020 -

Date of issue

2020

History

-

Received

21 Apr 2020 -

Accepted

03 Aug 2020