Abstract

Neospora caninum is considered to be one of the main causes of abortion among cattle. The present survey was conducted in the municipality of Rolim de Moura, Rondônia State, Brazil. A questionnaire that investigates the epidemiological aspects of neosporosis was used in the analysis of risk factors associated with the animal-level and herd-level prevalence in dairy cattle. A total of 416 bovine blood samples were collected from 30 farms, and N. caninum antibody levels were measured by Indirect Fluorescent Antibody Test (IFAT). Analysis of dairy cattle serum samples revealed the presence of anti-N. caninum antibodies to be 47.36% (n = 197). Risk factors associated with N. caninum infection were the management system and access locations of dogs. The results of the present survey indicated that infection of dairy cattle with N. caninum is widespread in the studied region of Western Amazon, which has implications for prevention and control of neosporosis in this region. Therefore, integrated control strategies and measures are recommended to prevent and control N. caninum infection in dairy cattle. In addition, direct contact between dairy cattle, dogs and wild animals, which can influence the epidemiology of neosporosis, should be investigated further.

Keywords:

Risk factors; prevalence; neosporosis; Western Amazon; Brazil

Resumo

A infecção por Neospora caninum é considerada uma das principais causas de aborto entre bovinos. Esta pesquisa foi realizada no município de Rolim de Moura, estado de Rondônia, Brasil. Um questionário que investiga os aspectos epidemiológicos da neosporose foi utilizado na análise dos fatores de risco associados à prevalência em animais e em rebanhos. Um total de 416 amostras de sangue bovino foi colhido em 30 fazendas, e os níveis de anticorpos de N. caninum foram mensurados pela reação de Imunofluorescência Indireta (RIFI). A análise das amostras mostrou prevalência de anticorpos contra N. caninum de 47,36% (n = 197). Os fatores de risco associados à infecção por N. caninum foram o sistema de manejo e os locais de acesso dos cães. Os resultados da presente pesquisa indicam que a infecção de bovinos leiteiros com N. caninum está disseminada na região estudada da Amazônia Ocidental, o que tem implicações para a prevenção e controle da neosporose nessa região. Portanto, estratégias e medidas de controle integrado são recomendadas para prevenir e controlar a infecção por N. caninum em gado leiteiro. Além disso, o contato íntimo entre gado leiteiro, cães e animais selvagens, pode influenciar a epidemiologia da neosporose e deve ser investigada mais detalhadamente.

Palavras-chave:

Fatores de risco; prevalência; neosporose; Amazônia Ocidental; Brasil

Introduction

Neosporosis is a parasitic disease caused by Neospora caninum, a protozoan misdiagnosed because of their morphological similarities (Dubey et al., 1988Dubey JP, Hattel AL, Lindsay DS, Topper MJ. Neonatal Neospora caninum infection in dogs: isolation of the causative agent and experimental transmission. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1988; 193(10): 1259-1263. PMid:3144521.). Neospora caninum is considered to be one of the main causes of abortion among cattle (Almería et al., 2017Almería S, Serrano-Pérez B, López-Gatius F. Immune response in bovine neosporosis: protection or contribution to the pathogenesis of abortion. Microb Pathog 2017; 109: 177-182. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2017.05.042. PMid:28578088.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2017...

; Dubey & Schares, 2011Dubey JP, Schares G. Neosporosis in animals--the last five years. Vet Parasitol 2011; 180(1-2): 90-108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.05.031. PMid:21704458.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2011....

; Maldonado Rivera et al., 2020Maldonado Rivera JE, Vallecillo AJ, Pérez CL, Cirone KM, Dorsch MA, Morrell EL, et al. Bovine neosporosis in dairy cattle from the southern highlands of Ecuador. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Reports 2020; 20: 100377. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vprsr.2020.100377. PMid:32448544.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vprsr.2020.1...

; Reichel et al., 2013Reichel MP, Alejandra Ayanegui-Alcérreca M, Gondim LFP, Ellis JT. What is the global economic impact of Neospora caninum in cattle - the billion dollar question. Int J Parasitol 2013; 43(2): 133-142. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.10.022. PMid:23246675.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2012....

). Although this parasite has not been demonstrated as a zoonosis, antibodies to N. caninum have been reported in humans (Duarte et al., 2020Duarte PO, Oshiro LM, Zimmermann NP, Csordas BG, Dourado DM, Barros JC, et al. Serological and molecular detection of Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii in human umbilical cord blood and placental tissue samples. Sci Rep 2020; 10(1): 9043. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65991-1. PMid:32493968.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-659...

; Lobato et al., 2006Lobato J, Silva DA, Mineo TW, Amaral JD, Segundo GR, Costa-Cruz JM, et al. Detection of immunoglobulin G antibodies to Neospora caninum in humans: high seropositivity rates in patients who are infected by human immunodeficiency virus or have neurological disorders. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2006; 13(1): 84-89. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CVI.13.1.84-89.2006. PMid:16426004.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CVI.13.1.84-89...

).

In pregnant cows, infection with N. caninum can lead to several outcomes, including early foetal death and re-absorption; abortion, stillbirth or parturition of a deformed calf; and birth of clinically normal but infected offspring (Dubey et al., 2006Dubey JP, Buxton D, Wouda W. Pathogenesis of bovine neosporosis. J Comp Pathol 2006; 134(4): 267-289. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcpa.2005.11.004. PMid:16712863.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcpa.2005.11...

; Favero et al., 2017Fávero JF, Silva AS, Campigotto G, Machado G, Daniel de Barros L, Garcia JL, et al. Risk factors for Neospora caninum infection in dairy cattle and their possible cause-effect relation for disease. Microb Pathog 2017; 110: 202-207. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2017.06.042. PMid:28666842.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2017...

). Neosporosis is of great economic importance, resulting in huge economic losses for farmers.

The State of Rondônia is located in the Western Amazon and has the second largest cattle herd stock in the North Region, which accounts for the third largest herd in Brazil, with 32 million animals (IBGE, 2016Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE. Produção da Pecuária Brasileira [online]. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2016 [cited 2016 Jan 11]. Available from: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/economicas/agricultura-e-pecuaria/9107-producao-da-pecuaria-municipal.html?=&t=resultados

https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/eco...

). In Brazil, the presence of N. caninum antibodies in cattle has been studied in several areas (Cerqueira-Cézar et al., 2017Cerqueira-Cézar CK, Calero-Bernal R, Dubey JP, Gennari SM. All about neosporosis in Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2017; 26(3): 253-279. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1984-29612017045. PMid:28876360.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1984-29612017...

; Gennari, 2004Gennari SM. Neospora caninum no Brasil: situação atual da pesquisa. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2004; 13(Suppl 1): 23-28.), but only five of these reports was related to the Amazon region (Aguiar et al., 2006Aguiar DM, Cavalcante GT, Rodrigues AA, Labruna MB, Camargo LM, Camargo EP, et al. Prevalence of anti-Neospora caninum antibodies in cattle and dogs from Western Amazon, Brazil, in association with some possible risk factors. Vet Parasitol 2006; 142(1-2): 71-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.06.014. PMid:16857319.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006....

; Benetti et al., 2009Benetti AH, Schein FB, Santos TR, Toniollo GH, Costa AJ, Mineo JR, et al. Pesquisa de anticorpos anti-Neospora caninum em bovinos leiteiros, cães e trabalhadores rurais da região Sudoeste do Estado de Mato Grosso. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2009; 18(e1): 29-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbpv.018e1005. PMid:20040187.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbpv.018e1005...

; Boas et al., 2015Boas RV, Pacheco TA, Melo AL, de Oliveira AC, de Aguiar DM, Pacheco RC. Infection by Neospora caninum in dairy cattle belonging to family farmers in the northern region of Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2015; 24(2): 204-208. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612015035. PMid:26154960.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612015...

; Silva et al., 2017Silva JB, Nicolino RR, Fagundes GM, dos Anjos Bomjardim H, dos Santos Belo Reis A, da Silva Lima DH, et al. Serological survey of Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii in cattle (Bos indicus) and water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) in ten provinces of Brazil. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 2017; 52: 30-35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cimid.2017.05.005. PMid:28673459.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cimid.2017.0...

; Minervino et al., 2008Minervino AHH, Ragozo AMA, Monteiro RM, Ortolani EL, Gennari SM. Prevalence of Neospora caninum antibodies in cattle from Santarem, Pará, Brazil. Res Vet Sci 2008; 84(2): 254-256. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2007.05.003. PMid:17619028.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2007.05...

). Of the studies conducted in cattle in the Amazon region, only two were conducted in Rondônia (Aguiar et al., 2006Aguiar DM, Cavalcante GT, Rodrigues AA, Labruna MB, Camargo LM, Camargo EP, et al. Prevalence of anti-Neospora caninum antibodies in cattle and dogs from Western Amazon, Brazil, in association with some possible risk factors. Vet Parasitol 2006; 142(1-2): 71-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.06.014. PMid:16857319.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006....

; Boas et al., 2015Boas RV, Pacheco TA, Melo AL, de Oliveira AC, de Aguiar DM, Pacheco RC. Infection by Neospora caninum in dairy cattle belonging to family farmers in the northern region of Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2015; 24(2): 204-208. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612015035. PMid:26154960.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612015...

).

The study of Aguiar et al. (2006)Aguiar DM, Cavalcante GT, Rodrigues AA, Labruna MB, Camargo LM, Camargo EP, et al. Prevalence of anti-Neospora caninum antibodies in cattle and dogs from Western Amazon, Brazil, in association with some possible risk factors. Vet Parasitol 2006; 142(1-2): 71-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.06.014. PMid:16857319.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006....

took place in the rural area of Monte Negro, Rondônia, and a N. caninum prevalence of 10.4% and 12.6% was detected in cattle and farm dogs, respectively.

Boas et al. (2015)Boas RV, Pacheco TA, Melo AL, de Oliveira AC, de Aguiar DM, Pacheco RC. Infection by Neospora caninum in dairy cattle belonging to family farmers in the northern region of Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2015; 24(2): 204-208. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612015035. PMid:26154960.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612015...

confirmed the presence of anti-N. caninum antibodies (10.6%) in cattle from Rondônia State, suggesting the necessity to further investigate the epidemiology of N. caninum in the Amazon region.

Cañón-Franco et al. (2003)Cañón-Franco WA, Bergamaschi DP, Labruna MB, Camargo LMA, Souza SLP, Silva JCR, et al. Prevalence of antibodies to Neospora caninum in dogs from Amazon, Brazil. Vet Parasitol 2003; 115(1): 71-74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(03)00131-6. PMid:12860070.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(03)...

reported a seroprevalence of 8.3% for N. caninum in the urban dog population of Monte Negro municipality, state of Rondônia, suggesting the presence of the agent infecting cattle and other species in the region.

The possibility of transmission of N. caninum among wild and domestic animals has been widely discussed. The existence of a so-called wild cycle of neosporosis that may occur between canids and wild herbivores could influence the epidemiology of the disease in domestic livestock (Gondim et al., 2004Gondim LFP, McAllister MM, Mateus-Pinilla NE, Pitt WC, Mech LD, Nelson ME. Transmission of Neospora caninum between wild and domestic animals. J Parasitol 2004; 90(6): 1361-1365. http://dx.doi.org/10.1645/GE-341R. PMid:15715229.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1645/GE-341R...

; Rosypal & Lindsay, 2005Rosypal AC, Lindsay DS. The sylvatic cycle of Neospora caninum: where do we go from here? Trends Parasitol 2005; 21(10): 439-440. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2005.08.003. PMid:16098812.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2005.08.0...

).

In the Legal Amazon, the raising of livestock is the activity most strongly correlated with deforestation. Currently, livestock is present both at the consolidated border and in the expansion zones of forest occupation, popularly known as capoeira areas (Rivero et al., 2009Rivero S, Almeida O, Ávila S, Oliveira W. Pecuária e desmatamento: uma análise das principais causas diretas do desmatamento na Amazônia. Nova Econ 2009; 19(1): 41-66. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-63512009000100003.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-63512009...

). In Rondônia, this intimate contact between dairy cattle, dogs and wild animals could influence the epidemiology of neosporosis.

In this context, the present study aimed to evaluate the current status of the prevalence of N. caninum in dairy cattle from the state of Rondônia, Brazil and correlate possible variables associated with seropositivity for these protozoan.

Methods

Ethics statement

All procedures using animals complied with the Ethical Principles in Animal Research adopted by the College of Animal Experimentation and were approved (protocol number PP010/2014) by the Ethical Committee for Animal Welfare, UNIR, Rolim de Moura, Rondônia, Brazil.

Study region

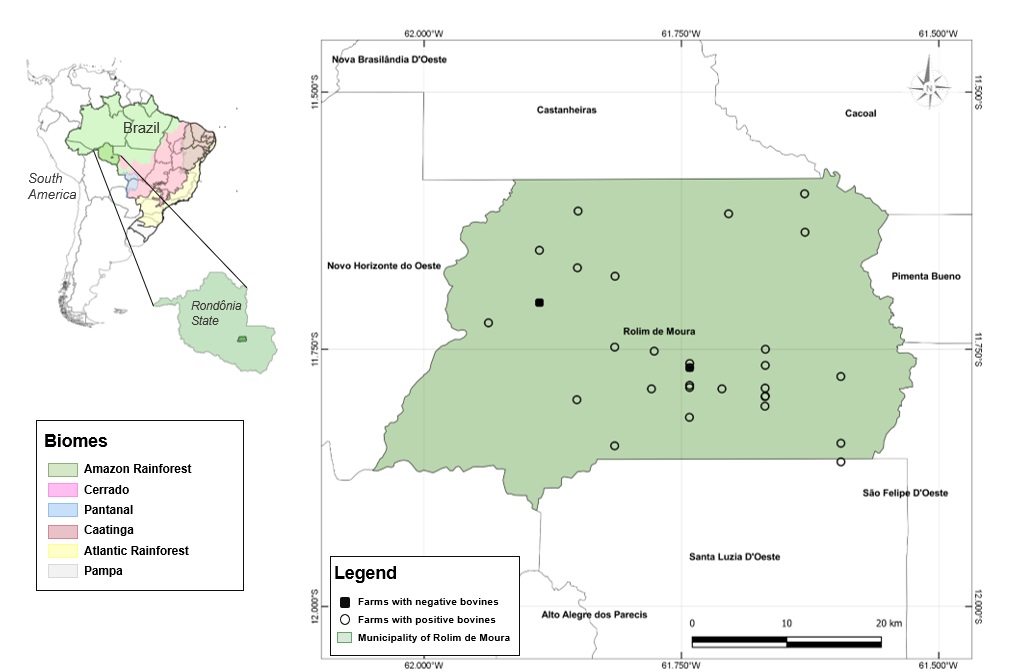

The survey was conducted in Rolim de Moura (11º48'13”S, 61º48'12”W), which extends over 402 km2 in Rondônia State, North Brazil (IBGE, 2016Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE. Produção da Pecuária Brasileira [online]. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2016 [cited 2016 Jan 11]. Available from: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/economicas/agricultura-e-pecuaria/9107-producao-da-pecuaria-municipal.html?=&t=resultados

https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/eco...

). The properties evaluated were classified according to the size: into small (<10 hectares), medium (11-100 hectares) and large (> 100 hectares). The climate is Aw of the Köppen classification (Peel et al., 2007Peel MC, Finlayson BL, McMahon TA. Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 2007; 11(5): 1633-1644. http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/hess-11-1633-2...

), which is characterized as equatorial with changes to the hot and humid tropical with a well-defined dry season from March to September, minimum temperature of 24 ºC and a maximum of 32 ºC, with precipitation between high and moderately high (2000 to 2250 mm) and 85% relative air humidity.

The georeferencing (Figure 1) of the visited properties was carried out with a GPS device. The data were then transported to the QGIS Desktop (3.12.3) program (QGIS Development Team, 2020QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System [online]. Chicago: Open Source Geospatial Foundation; 2020 [cited 2020 Jun 8]. Available from: https://www.qgis.org/pt_BR/site/#

https://www.qgis.org/pt_BR/site/#...

), where they were placed on the Rolim de Moura/RO map. The database modelling and chart plotting stages were carried out at the Institute of Agrarian Sciences, Federal University of the Jequitinhonha and Mucuri Valleys.

Epidemiological survey

A comprehensive questionnaire investigating the epidemiological aspects of neosporosis was used in the analysis of risk factors associated with the animal-level and herd-level prevalence. The analysed variables and respective categories were as follows: sex, age, animal category, management system (intensive, semi-intensive and extensive), herd size (small: < 100 animals, medium: 100-150 animals and large: > 150 animals), technical monitoring (yes or no), stock up facility for food (yes or no), surface type of milking shed (wooden clapboard or cemented), farm hygienic status (not clean or clean), water source (dam or drinking fountain), feeder (wooden or cemented), presence of wild animals (yes or no), presence of dogs (yes or no), access locations of dogs (pasture or barn), abortion in the last 12 months and stage of gestation that abortions occurred (first, second or third trimester). The main classification criteria for the management system was animal stocking rate (SR: animal unit ha–1, in which an animal unit = 450 kg of body weight): extensive: with pasture support capacity of up to 1.9 AU/ha; semi-intensive: with support capacity between 2 and 3.5 AU/ha and intensive: with support capacity between 3.6 and 7 AU/ha. Furthermore, in the extensive system the animals to lived predominantly pasture feeding management and in the semi-intensive, food management based on grazing, salt mineral and feed supplementation. Intensive system was characterized by a significant investment in buildings, machinery (such as milking parlour with automatic milking facilities) and private pastures (which are cultured and fenced).

Serum samples

The number of samples was calculated assuming that the prevalence of N. caninum is approximately 50% to maximize the sample size, obtain a minimal confidence interval (CI) of 95%, and maintain the statistical error under 1%. Calculations were executed using an EpiInfo program (CDC, version 7.2.0.1), resulting in a sample size of 416 bovines collected from the 30 farms (Thrusfield, 2005Thrusfield M. Veterinary epidemiology. 3rd ed. Cambridge: Blackwell Science; 2005.). Cattle from each farm were selected randomly using a table of random digits. In the case of cattle, approximately ten percent of animals from each farm were sampled. The sampled animals were crossbred cows, usually derived from the crossing of animals of a purebred European origin (Holstein) with animals of one of the zebu breeds (Gyr) in various degrees of blood. All the animals sampled were clinically healthy. A total of 416 crossbred Holstein cattle blood samples (10 mL) were collected by venocentesis, using identified vacuum tubes, and centrifuged at 1000g for 10 min. The serum was separated and stored at −20 °C until analysis.

Serological tests

Neospora caninum antibody levels were measured by Indirect Fluorescent Antibody Test (IFAT). using rabbit anti-bovine IgG conjugate labelled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) according to Dubey et al. (1988)Dubey JP, Hattel AL, Lindsay DS, Topper MJ. Neonatal Neospora caninum infection in dogs: isolation of the causative agent and experimental transmission. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1988; 193(10): 1259-1263. PMid:3144521., with a cut-off value of 1:200 (Benetti et al., 2009Benetti AH, Schein FB, Santos TR, Toniollo GH, Costa AJ, Mineo JR, et al. Pesquisa de anticorpos anti-Neospora caninum em bovinos leiteiros, cães e trabalhadores rurais da região Sudoeste do Estado de Mato Grosso. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2009; 18(e1): 29-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbpv.018e1005. PMid:20040187.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbpv.018e1005...

; Gennari, 2004Gennari SM. Neospora caninum no Brasil: situação atual da pesquisa. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2004; 13(Suppl 1): 23-28.). Neospora caninum tachyzoites (NC-1) maintained in Vero cell cultures were used as antigens. Positive and negative control sera were added to each slide, and all the positive samples were retested using a two-fold serial dilution.

Determination of prevalence and statistical analyses

Statistical tests were performed using STATA, version 14.1, software (Stata Corp LP, College Station, Texas, USA). The research variables were presented as percentages and 95% CIs for proportion. For inferential statistics, the seroprevalences of N. caninum infection were considered as the dependent variables and other factors were considered as the explanatory variables.

Pearson’s Chi square (χ2) or Fisher exact tests was executed to evaluate the differences between groups. To investigate the independent risk factors of each explanatory variable, all variables that showed a p value ≤ 0.25 in the univariate analysis were offered to the multivariate logistic regression model as suggested by (Bendel & Afifi, 1977Bendel RB, Afifi AA. Comparison of stopping rules in forward “stepwise” regression. J Am Stat Assoc 1977; 72(357): 46-53. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2286904.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2286904...

; Bursac et al., 2008Bursac Z, Gauss CH, Williams DK, Hosmer DW. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol Med 2008; 3(1): 17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1751-0473-3-17. PMid:19087314.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1751-0473-3-17...

). It is advised to use an initial screening p value cut-off point of 0.25, as more traditional levels such as 0.05 can fail to recognize variables known to be important. The occurrence probability ratio [odds ratio (OR)] and the corresponding 95% CI were calculated by using univariate and multiple logistic regression. A p value < 0.05 was considered as the level of statistical significance for all tests.

Results

Analysis of crossbred Holstein cattle serum samples revealed the prevalence percentages of anti-N. caninum antibodies to be 47.36%. Herd-level seroprevalence was of the order of 93.33%. Seroprevalence results of N. caninum are summarized by herds in Table 1.

Detection of anti-N. caninum antibodies (IFAT-IgG) in dairy cattle herds from Western Amazon, Brazil.

Table 2 shows data according to the animal category. Seroprevalences for N. caninum were 77.78% (95% CI: 39.99–97.19) in bulls, 53.06% (95% CI: 38.27–67.47) in heifers, 47.28% (95% CI: 41.46–53.16) in cows and 39.06% (95% CI: 27.10-52.07) in calves. There was no statistically significant association between groups and subgroups of the animal categories (p > 0.05)

Seroprevalence of N. caninum in crossbred Holstein cattle from Western Amazon by animal category.

All the evaluated herds showed the presence of wild animals, domestic dogs and abortion in the last 12 months; therefore, these explanatory variables were not analysed statistically.

Regarding the sex, age, stock up facility for food, water source and stage of gestation that abortions occurred, there were no significant differences (p > 0.05) in the seropositivity for neosporosis and no were included in the logistic regression model (Table 3).

Univariable analysis and multivariable logistic regression model of the predictors of N. caninum seroprevalence among dairy cattle in the Western Amazon, Brazil.

We evaluated six (20.0%) small-sized properties, 16 (53.3%) medium-sized properties and eight (26.7%) large-sized properties, with a prevalence rate of 44.4%, 49.6% and 51.1%, respectively, and there was no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05).

The data from the univariate analysis is summarized in Table 3, and we can see that the statistically significant (p < 0.05) explanatory variables were the management system (OR: 1.68, p = 0.01), farm hygienic status (OR: 1.84, p = 0.01) and access locations of dogs (OR: 1.92, p < 0.01).

The multivariable logistic regression model (Table 3) of the predictors of N. caninum seroprevalence was performed in all variables (management system, herd size, technical monitoring, surface type of milking shed, farm hygienic status, feeder and access locations of dogs) with p value ≤ 0.25 in the univariate analysis.

Applying the multivariate logistic regression model, tests of the association between the seroprevalence of N. caninum infection and potential predictors showed that the management system (OR: 2.05, 95% CI: 1.19-3.53), access locations of dogs (OR: 2.24, 95% CI: 1.43-3.49), surface type of milking shed (OR: 0.54, 95% CI: 0.31-0.94) and farm hygienic status (OR: 0.54, 95% CI: 0.33-0.89) were significant (p < 0.05) independent predictors for N. caninum infection (Table 3).

Discussion

In the present study, the animal-level and herd-level seroprevalence of N. caninum in dairy cattle was 47.36% and 93.33%, respectively. In Brazil, the seroprevalence of anti-N. caninum antibodies in cattle varies from 6.7% to 97.2% (Cerqueira-Cézar et al., 2017Cerqueira-Cézar CK, Calero-Bernal R, Dubey JP, Gennari SM. All about neosporosis in Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2017; 26(3): 253-279. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1984-29612017045. PMid:28876360.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1984-29612017...

). Regarding seroepidemiological studies in dairy cattle carried out in the Amazon region, the prevalence found in this research was higher than the results found by Minervino et al. (2008)Minervino AHH, Ragozo AMA, Monteiro RM, Ortolani EL, Gennari SM. Prevalence of Neospora caninum antibodies in cattle from Santarem, Pará, Brazil. Res Vet Sci 2008; 84(2): 254-256. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2007.05.003. PMid:17619028.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2007.05...

in Pará (17.5%; cut-off 1:50); Aguiar et al. (2006)Aguiar DM, Cavalcante GT, Rodrigues AA, Labruna MB, Camargo LM, Camargo EP, et al. Prevalence of anti-Neospora caninum antibodies in cattle and dogs from Western Amazon, Brazil, in association with some possible risk factors. Vet Parasitol 2006; 142(1-2): 71-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.06.014. PMid:16857319.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006....

in Rondônia (11.2%; cut-off 1:25); Boas et al. (2015)Boas RV, Pacheco TA, Melo AL, de Oliveira AC, de Aguiar DM, Pacheco RC. Infection by Neospora caninum in dairy cattle belonging to family farmers in the northern region of Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2015; 24(2): 204-208. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612015035. PMid:26154960.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612015...

in Rondônia (10.2%; cut-off 1:100); and similar to those described by Benetti et al. (2009)Benetti AH, Schein FB, Santos TR, Toniollo GH, Costa AJ, Mineo JR, et al. Pesquisa de anticorpos anti-Neospora caninum em bovinos leiteiros, cães e trabalhadores rurais da região Sudoeste do Estado de Mato Grosso. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2009; 18(e1): 29-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbpv.018e1005. PMid:20040187.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbpv.018e1005...

in Mato Grosso (53.5%; cut-off 1:200). However, these values are not entirely comparable since different cut-offs were applied and IFAT reading is partially subjective (Álvarez-García et al., 2003Alvarez-García G, Collantes-Fernández E, Costas E, Rebordosa X, Ortega-Mora LM. Influence of age and purpose for testing on the cut-off selection of serological methods in bovine neosporosis. Vet Res 2003; 34(3): 341-352. http://dx.doi.org/10.1051/vetres:2003009. PMid:12791243.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1051/vetres:2003009...

; Campero et al., 2018Campero LM, Moreno-Gonzalo J, Venturini MC, Moré G, Dellarupe A, Rambeaud M, et al. An Ibero-American inter-laboratory trial to evaluate serological tests for the detection of anti-Neospora caninum antibodies in cattle. Trop Anim Health Prod 2018; 50(1): 75-84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11250-017-1401-x. PMid:28918478.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11250-017-140...

; Von Blumröder et al., 2004von Blumröder D, Schares G, Norton R, Williams DJL, Esteban-Redondo I, Wright S, et al. Comparison and standardisation of serological methods for the diagnosis of Neospora caninum infection in bovines. Vet Parasitol 2004; 120(1-2): 11-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.12.010. PMid:15019139.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2003....

; Wapenaar et al., 2007Wapenaar W, Barkema HW, Vanleeuwen JA, McClure JT, O’Handley RM, Kwok OC, et al. Comparison of serological methods for the diagnosis of Neospora caninum infection in cattle. Vet Parasitol 2007; 143(2): 166-173. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.08.007. PMid:16989951.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006....

)

We observed that N. caninum is widely spread in the studied region, with only two farms obtaining negative results; however, we could not exclude the presence of this protozoan in these properties due to the number of samples collected.

The high infection at the herd-level and the similarity with the seroprevalence reported by Cerqueira-Cézar et al. (2017)Cerqueira-Cézar CK, Calero-Bernal R, Dubey JP, Gennari SM. All about neosporosis in Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2017; 26(3): 253-279. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1984-29612017045. PMid:28876360.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1984-29612017...

could indicate that N. caninum is endemic in the country. This prevalence may be explained by the hot and humid climate of the Amazon region and high levels of precipitation that average 2000 mm annually, which may contribute to higher viability among oocysts in the environment (Dubey et al., 2007Dubey JP, Schares G, Ortega-Mora LM. Epidemiology and control of neosporosis and Neospora caninum. Clin Microbiol Rev 2007; 20(2): 323-367. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00031-06. PMid:17428888.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00031-06...

; Moloney et al., 2017Moloney BJ, Heuer C, Kirkland PD. Neospora caninum in beef herds in New South Wales, Australia. 2: analysis of risk factors. Aust Vet J 2017; 95(4): 101-109. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/avj.12563. PMid:28346670.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/avj.12563...

).

Milk production in Rondônia (8th place in the ranking of the largest national producers) is an economic activity composed of approximately 32,000 families, the majority of which are small producers (IBGE, 2019Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE. Produção da Pecuária Brasileira [online]. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2019 [cited 2019 Jan 10]. Available from: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/economicas/agricultura-e-pecuaria/21814-2017-censo-agropecuario.html?=&t=resultados

https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/eco...

). Dairy farming has great social relevance, being one of the rural activities that employs most of the labour among the productive chains in family farming.

Higher N. caninum prevalence was detected in bulls in relation to cows. This difference could be related with the constant renewal of the cow herds, while the bulls remained in the herd for a longer period of time than the females. These results are in agreement with those reported by Guimarães et al. (2004)Guimarães JS Jr, Souza SLP, Bergamaschi DP, Gennari SM. Prevalence of Neospora caninum antibodies and factors associated with their presence in dairy cattle of the north of Parana state, Brazil. Vet Parasitol 2004; 124(1-2): 1-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.07.002. PMid:15350656.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004....

.

In this study, we found a prevalence of 39.06% for calves, which can be explained by vertical and horizontal transmissions. For heifers, the prevalence was 53.06%, which could have occurred due to the maintenance of horizontal infection.

Vertical transmission is considered effective in bovines, since it is responsible for maintaining the infection in the herd (Dubey et al., 2006Dubey JP, Buxton D, Wouda W. Pathogenesis of bovine neosporosis. J Comp Pathol 2006; 134(4): 267-289. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcpa.2005.11.004. PMid:16712863.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcpa.2005.11...

). However, the infection could not be sustained in the herd only with vertical transmission, since its efficiency is not 100%. Therefore, horizontal transmission also plays a key role in perpetuating the disease in the herds. Without it, the infection levels would tend to reduce over time (French et al., 1999French NP, Clancy D, Davison HC, Trees AJ. Mathematical models of Neospora caninum infection in dairy cattle: transmission and options for control. Int J Parasitol 1999; 29(10): 1691-1704. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7519(99)00131-9. PMid:10608456.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7519(99)...

).

All the herds evaluated showed the presence of wild animals and domestic dogs, and these explanatory variables were not analysed statistically. In agreement with several researchers (Cerqueira-Cézar et al., 2017Cerqueira-Cézar CK, Calero-Bernal R, Dubey JP, Gennari SM. All about neosporosis in Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2017; 26(3): 253-279. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1984-29612017045. PMid:28876360.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1984-29612017...

; Corbellini et al., 2006Corbellini LG, Smith DR, Pescador CA, Schmitz M, Correa A, Steffen DJ, et al. Herd-level risk factors for Neospora caninum seroprevalence in dairy farms in southern Brazil. Prev Vet Med 2006; 74(2-3): 130-141. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2005.11.004. PMid:16343669.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.20...

; Hobson et al., 2005Hobson JC, Duffield TF, Kelton D, Lissemore K, Hietala SK, Leslie KE, et al. Risk factors associated with Neospora caninum abortion in Ontario Holstein dairy herds. Vet Parasitol 2005; 127(3-4): 177-188. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.09.025. PMid:15710518.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004....

; Macchi et al., 2020Macchi MV, Suanes A, Salaberry X, Fernandez F, Piaggio J, Gil AD. Epidemiological study of neosporosis in Uruguayan dairy herds. Prev Vet Med 2020; 179: 105022. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2020.105022. PMid:32407996.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.20...

; Otranto et al., 2003Otranto D, Llazari A, Testini G, Traversa D, di Regalbono AF, Badan M, et al. Seroprevalence and associated risk factors of neosporosis in beef and dairy cattle in Italy. Vet Parasitol 2003; 118(1-2): 7-18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.10.008. PMid:14651870.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2003....

; Ribeiro et al., 2019Ribeiro CM, Soares IR, Mendes RG, de Santis Bastos PA, Katagiri S, Zavilenski RB, et al. Meta-analysis of the prevalence and risk factors associated with bovine neosporosis. Trop Anim Health Prod 2019; 51(7): 1783-1800. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11250-019-01929-8. PMid:31228088.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11250-019-019...

; Schares et al., 2003Schares G, Barwald A, Staubach C, Ziller M, Kloss D, Wurm R, et al. Regional distribution of bovine Neospora caninum infection in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate modelled by Logistic regression. Int J Parasitol 2003; 33(14): 1631-1640. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7519(03)00266-2. PMid:14636679.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7519(03)...

, 2004aSchares G, Barwald A, Staubach C, Wurm R, Rauser M, Conraths FJ, et al. Adaptation of a commercial ELISA for the detection of antibodies against Neospora caninum in bovine milk. Vet Parasitol 2004a; 120(1-2): 55-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.11.016. PMid:15019143.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2003....

), an association with the number of dogs, there was no report of differences between the presence and absence of this species.

The prevalence increment association with rise in herd size could be linked to compromised hygienic measures in maintaining adequate waste disposal practices, increased likelihood of more dogs in the vicinity of the farm and/or a tendency towards raising replacement heifers from their own infected stock (Dubey et al., 2007Dubey JP, Schares G, Ortega-Mora LM. Epidemiology and control of neosporosis and Neospora caninum. Clin Microbiol Rev 2007; 20(2): 323-367. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00031-06. PMid:17428888.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00031-06...

).

The differences in prevalence could be influenced by many factors, such as the method and cut-off used; the number of cows examined; and their health status, age, gender and breed (Bártová et al., 2015Bártová E, Sedlak K, Budiková M. A study of Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii antibody seroprevalence in healthy cattle in the Czech Republic. Ann Agric Environ Med 2015; 22(1): 32-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.5604/12321966.1141365. PMid:25780824.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5604/12321966.11413...

). However, it can be influenced by the type of trough, barn floor, cleaning of facilities, and the presence of dogs on agricultural property (Cerqueira-Cézar et al., 2017Cerqueira-Cézar CK, Calero-Bernal R, Dubey JP, Gennari SM. All about neosporosis in Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2017; 26(3): 253-279. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1984-29612017045. PMid:28876360.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1984-29612017...

).

The Western Amazon of Brazil has prevalence values within the range found in other important regions of cattle production in Brazil. In the present study, the management system (OR 1.68, 95% CI: 1.11-2.54), farm hygienic status (OR: 1.84, 95% CI: 1.13-3.00) and access locations of dogs (OR 1.92, 95% CI: 1.25-2.94) were identified as risk factors associated (p < 0.05) with the prevalence of N. caninum infection in the univariable analysis.

In our study, the hygienic status of the farms was assessed according to floor condition, ventilation, drainage, and waste disposal routines. All these hygienic factors may contribute to maintaining the N. caninum cycle by providing canids access to tissue cysts through feeding with infected meat or organs and providing cattle access to oocysts through contamination of feed and water with dog faeces (Dubey et al., 2007Dubey JP, Schares G, Ortega-Mora LM. Epidemiology and control of neosporosis and Neospora caninum. Clin Microbiol Rev 2007; 20(2): 323-367. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00031-06. PMid:17428888.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00031-06...

; Schares et al., 2004bSchares G, Barwald A, Staubach C, Ziller M, Kloss D, Schroder R, et al. Potential risk factors for bovine Neospora caninum infection in Germany are not under the control of the farmers. Parasitology 2004b; 129(Pt 3): 301-309. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0031182004005700. PMid:15471005.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0031182004005...

).

Applying multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 3), tests of the association between the seroprevalence of N. caninum infection and potential predictors revealed a strong association with the management system (OR 2.05, 95% CI: 1.19-3.53) and access locations of dogs (OR 2.24, 95% CI: 1.43-3.49).

Farms with an extensive management system (Table 3) were more than 2.05 (95% CI: 1.19-3.53) at risk of acquiring the infection compared to the farms with a semi-intensive management system. This can be explained by the greater chances of contact with oocysts in the environment when the extensive management system is used. Animals with access to pasture have greater opportunity to infect themselves horizontally, when compared to those raised in the semi- intensive system, that the animals remain part of the day free in pastures and part of the day confined. Thus, an effective management mode is of extreme importance to control the spread of disease. These results are similar to those cited by Macchi et al. (2020)Macchi MV, Suanes A, Salaberry X, Fernandez F, Piaggio J, Gil AD. Epidemiological study of neosporosis in Uruguayan dairy herds. Prev Vet Med 2020; 179: 105022. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2020.105022. PMid:32407996.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.20...

, Ragozo et al. (2003)Ragozo AMA, Paula VSO, Souza SLP, Bergamaschi DP, Gennari SM. Ocorrência de anticorpos anti-Neospora caninum em soros de bovinos procedentes de seis estados brasileiros. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2003; 12(1): 33-37., Ribeiro et al. (2019)Ribeiro CM, Soares IR, Mendes RG, de Santis Bastos PA, Katagiri S, Zavilenski RB, et al. Meta-analysis of the prevalence and risk factors associated with bovine neosporosis. Trop Anim Health Prod 2019; 51(7): 1783-1800. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11250-019-01929-8. PMid:31228088.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11250-019-019...

, Silva et al. (2008)Silva MIS, Almeida MÂO, Mota RA, Pinheiro JW Jr, Rabelo SSDA. Fatores de riscos associados à infecção por Neospora caninum em matrizes bovinas leiteiras em Pernambuco. Cienc Anim Bras 2008; 9(2): 455-461..

The access of dogs to the pasture presented a significant risk factor (OR: 2.24, 95% CI: 1.43-3.49), influencing the high seroprevalence. This result agree with Nematollahi et al. (2011)Nematollahi A, Jaafari R, Moghaddam G. Seroprevalence of Neospora caninum Infection in Dairy Cattle in Tabriz, Northwest Iran. Iran J Parasitol 2011; 6(4): 95-98. PMid:22347319. who found that the presence of domestic dogs or dingoes can directly reflect the high rates of neosporosis in these locations. Aguiar et al. (2006)Aguiar DM, Cavalcante GT, Rodrigues AA, Labruna MB, Camargo LM, Camargo EP, et al. Prevalence of anti-Neospora caninum antibodies in cattle and dogs from Western Amazon, Brazil, in association with some possible risk factors. Vet Parasitol 2006; 142(1-2): 71-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.06.014. PMid:16857319.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006....

showed contact with forest areas and the presence of dogs were not associated with the coccidian infection.

The presence of dogs on cattle farms has been considered an important risk for cattle infection and abortion by N. caninum in different countries (Bartels et al., 1999Bartels CJM, Wouda W, Schukken YH. Risk factors for Neospora caninum-associated abortion storms in dairy herds in The Netherlands (1995 to 1997). Theriogenology 1999; 52(2): 247-257. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0093-691X(99)00126-0. PMid:10734392.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0093-691X(99)...

; Corbellini et al., 2006Corbellini LG, Smith DR, Pescador CA, Schmitz M, Correa A, Steffen DJ, et al. Herd-level risk factors for Neospora caninum seroprevalence in dairy farms in southern Brazil. Prev Vet Med 2006; 74(2-3): 130-141. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2005.11.004. PMid:16343669.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.20...

; Mainar-Jaime et al., 1999Mainar-Jaime RC, Thurmond MC, Berzal-Herranz B, Hietala SK. Seroprevalence of Neospora caninum and abortion in dairy cows in northern Spain. Vet Rec 1999; 145(3): 72-75. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/vr.145.3.72. PMid:10460027.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/vr.145.3.72...

; Martins et al., 2012Martins AA, Zamprogna TO, Lucas TM, Cunha IL, Garcia JL, Silva AV. Frequency and risk factors for infection by Neospora caninum in dairy farms of Umuarama, PR, Brazil. Arq Ciênc Vet Zool 2012; 15(2): 137-142.; Paré et al., 1998Paré J, Fecteau G, Fortin M, Marsolais G. Seroepidemiologic study of Neospora caninum in dairy herds. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1998; 213(11): 1595-1598. PMid:9838960.; Wouda et al., 1999Wouda W, Bartels CJM, Moen AR. Characteristics of Neospora caninum-associated abortion storms in dairy herds in The Netherlands (1995 to 1997). Theriogenology 1999; 52(2): 233-245. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0093-691X(99)00125-9. PMid:10734391.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0093-691X(99)...

). In addition, Barling et al. (2000)Barling KS, Sherman M, Peterson MJ, Thompson JA, McNeill JW, Craig TM, et al. Spatial associations among density of cattle, abundance of wild canids, and seroprevalence to Neospora caninum in a population of beef calves. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2000; 217(9): 1361-1365. http://dx.doi.org/10.2460/javma.2000.217.1361. PMid:11061391.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2460/javma.2000.217...

found a significant association between N. caninum infection in cattle and the presence of coyotes and grey foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) in farms in the Unites States.

Thus, observation of a higher seroprevalence associated with the access of wild carnivores to cattle ranches in Rondônia suggests that they may be involved in maintaining a wild cycle in this scenario. The apparently higher risk of exposure in the herds with wild carnivore access corroborates reports from Brazil (Martins et al., 2012Martins AA, Zamprogna TO, Lucas TM, Cunha IL, Garcia JL, Silva AV. Frequency and risk factors for infection by Neospora caninum in dairy farms of Umuarama, PR, Brazil. Arq Ciênc Vet Zool 2012; 15(2): 137-142.).

A possible way of infection could be the consumption of water contaminated with N. caninum oocysts from the faeces of infected wild or domestic canids, because they may come to the water source region to drink and at the same time defecate in or near it (Sun et al., 2015Sun WW, Meng QF, Cong W, Shan XF, Wang CF, Qian AD. Herd-level prevalence and associated risk factors for Toxoplasma gondii, Neospora caninum, Chlamydia abortus and bovine viral diarrhoea virus in commercial dairy and beef cattle in eastern, northern and northeastern China. Parasitol Res 2015; 114(11): 4211-4218. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-015-4655-0. PMid:26231838.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-015-465...

). Thus, a strict detection system for the drinking water of cattle should be implemented in the study regions.

It is concluded that neosporosis can be one of the possible causes of abortion in dairy cattle in Rolim de Moura, Rondônia. Regarding the distribution in dogs as definitive hosts for the parasite, further studies in dog and cattle are recommended. Neosporosis is of great economic importance, resulting in huge economic losses for farmers.

Conclusion

The results of the present survey indicate that infection of dairy cattle with N. caninum is widespread in Rolim de Moura, Western Amazon, which has implications for the prevention and control of neosporosis in this region. Therefore, integrated control strategies and measures are recommended to prevent and control N. caninum infections in dairy cattle. In Rondônia, this intimate contact between dairy cattle, dogs and wild animals could influence the epidemiology of neosporosis.

-

How to cite: Venturoso PJS, Venturoso OJ, Silva GG, Maia MO, Witter R, Aguiar DM, et al. Risk factor analysis associated with Neospora caninum in dairy cattle in Western Brazilian Amazon. Braz J Vet Parasitol 2021; 30(1): e023020. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-296120201088

References

- Aguiar DM, Cavalcante GT, Rodrigues AA, Labruna MB, Camargo LM, Camargo EP, et al. Prevalence of anti-Neospora caninum antibodies in cattle and dogs from Western Amazon, Brazil, in association with some possible risk factors. Vet Parasitol 2006; 142(1-2): 71-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.06.014 PMid:16857319.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.06.014 - Almería S, Serrano-Pérez B, López-Gatius F. Immune response in bovine neosporosis: protection or contribution to the pathogenesis of abortion. Microb Pathog 2017; 109: 177-182. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2017.05.042 PMid:28578088.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2017.05.042 - Alvarez-García G, Collantes-Fernández E, Costas E, Rebordosa X, Ortega-Mora LM. Influence of age and purpose for testing on the cut-off selection of serological methods in bovine neosporosis. Vet Res 2003; 34(3): 341-352. http://dx.doi.org/10.1051/vetres:2003009 PMid:12791243.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1051/vetres:2003009 - Barling KS, Sherman M, Peterson MJ, Thompson JA, McNeill JW, Craig TM, et al. Spatial associations among density of cattle, abundance of wild canids, and seroprevalence to Neospora caninum in a population of beef calves. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2000; 217(9): 1361-1365. http://dx.doi.org/10.2460/javma.2000.217.1361 PMid:11061391.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2460/javma.2000.217.1361 - Bartels CJM, Wouda W, Schukken YH. Risk factors for Neospora caninum-associated abortion storms in dairy herds in The Netherlands (1995 to 1997). Theriogenology 1999; 52(2): 247-257. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0093-691X(99)00126-0 PMid:10734392.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0093-691X(99)00126-0 - Bártová E, Sedlak K, Budiková M. A study of Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii antibody seroprevalence in healthy cattle in the Czech Republic. Ann Agric Environ Med 2015; 22(1): 32-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.5604/12321966.1141365 PMid:25780824.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.5604/12321966.1141365 - Bendel RB, Afifi AA. Comparison of stopping rules in forward “stepwise” regression. J Am Stat Assoc 1977; 72(357): 46-53. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2286904

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2286904 - Benetti AH, Schein FB, Santos TR, Toniollo GH, Costa AJ, Mineo JR, et al. Pesquisa de anticorpos anti-Neospora caninum em bovinos leiteiros, cães e trabalhadores rurais da região Sudoeste do Estado de Mato Grosso. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2009; 18(e1): 29-33. http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbpv.018e1005 PMid:20040187.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.4322/rbpv.018e1005 - Boas RV, Pacheco TA, Melo AL, de Oliveira AC, de Aguiar DM, Pacheco RC. Infection by Neospora caninum in dairy cattle belonging to family farmers in the northern region of Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2015; 24(2): 204-208. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612015035 PMid:26154960.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612015035 - Bursac Z, Gauss CH, Williams DK, Hosmer DW. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol Med 2008; 3(1): 17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1751-0473-3-17 PMid:19087314.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1751-0473-3-17 - Campero LM, Moreno-Gonzalo J, Venturini MC, Moré G, Dellarupe A, Rambeaud M, et al. An Ibero-American inter-laboratory trial to evaluate serological tests for the detection of anti-Neospora caninum antibodies in cattle. Trop Anim Health Prod 2018; 50(1): 75-84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11250-017-1401-x PMid:28918478.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11250-017-1401-x - Cañón-Franco WA, Bergamaschi DP, Labruna MB, Camargo LMA, Souza SLP, Silva JCR, et al. Prevalence of antibodies to Neospora caninum in dogs from Amazon, Brazil. Vet Parasitol 2003; 115(1): 71-74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(03)00131-6 PMid:12860070.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(03)00131-6 - Cerqueira-Cézar CK, Calero-Bernal R, Dubey JP, Gennari SM. All about neosporosis in Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2017; 26(3): 253-279. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1984-29612017045 PMid:28876360.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1984-29612017045 - Corbellini LG, Smith DR, Pescador CA, Schmitz M, Correa A, Steffen DJ, et al. Herd-level risk factors for Neospora caninum seroprevalence in dairy farms in southern Brazil. Prev Vet Med 2006; 74(2-3): 130-141. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2005.11.004 PMid:16343669.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2005.11.004 - Duarte PO, Oshiro LM, Zimmermann NP, Csordas BG, Dourado DM, Barros JC, et al. Serological and molecular detection of Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii in human umbilical cord blood and placental tissue samples. Sci Rep 2020; 10(1): 9043. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65991-1 PMid:32493968.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65991-1 - Dubey JP, Buxton D, Wouda W. Pathogenesis of bovine neosporosis. J Comp Pathol 2006; 134(4): 267-289. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcpa.2005.11.004 PMid:16712863.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcpa.2005.11.004 - Dubey JP, Hattel AL, Lindsay DS, Topper MJ. Neonatal Neospora caninum infection in dogs: isolation of the causative agent and experimental transmission. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1988; 193(10): 1259-1263. PMid:3144521.

- Dubey JP, Schares G, Ortega-Mora LM. Epidemiology and control of neosporosis and Neospora caninum. Clin Microbiol Rev 2007; 20(2): 323-367. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00031-06 PMid:17428888.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00031-06 - Dubey JP, Schares G. Neosporosis in animals--the last five years. Vet Parasitol 2011; 180(1-2): 90-108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.05.031 PMid:21704458.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.05.031 - Fávero JF, Silva AS, Campigotto G, Machado G, Daniel de Barros L, Garcia JL, et al. Risk factors for Neospora caninum infection in dairy cattle and their possible cause-effect relation for disease. Microb Pathog 2017; 110: 202-207. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2017.06.042 PMid:28666842.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2017.06.042 - French NP, Clancy D, Davison HC, Trees AJ. Mathematical models of Neospora caninum infection in dairy cattle: transmission and options for control. Int J Parasitol 1999; 29(10): 1691-1704. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7519(99)00131-9 PMid:10608456.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7519(99)00131-9 - Gennari SM. Neospora caninum no Brasil: situação atual da pesquisa. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2004; 13(Suppl 1): 23-28.

- Gondim LFP, McAllister MM, Mateus-Pinilla NE, Pitt WC, Mech LD, Nelson ME. Transmission of Neospora caninum between wild and domestic animals. J Parasitol 2004; 90(6): 1361-1365. http://dx.doi.org/10.1645/GE-341R PMid:15715229.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1645/GE-341R - Guimarães JS Jr, Souza SLP, Bergamaschi DP, Gennari SM. Prevalence of Neospora caninum antibodies and factors associated with their presence in dairy cattle of the north of Parana state, Brazil. Vet Parasitol 2004; 124(1-2): 1-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.07.002 PMid:15350656.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.07.002 - Hobson JC, Duffield TF, Kelton D, Lissemore K, Hietala SK, Leslie KE, et al. Risk factors associated with Neospora caninum abortion in Ontario Holstein dairy herds. Vet Parasitol 2005; 127(3-4): 177-188. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.09.025 PMid:15710518.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.09.025 - Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE. Produção da Pecuária Brasileira [online]. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2016 [cited 2016 Jan 11]. Available from: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/economicas/agricultura-e-pecuaria/9107-producao-da-pecuaria-municipal.html?=&t=resultados

» https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/economicas/agricultura-e-pecuaria/9107-producao-da-pecuaria-municipal.html?=&t=resultados - Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE. Produção da Pecuária Brasileira [online]. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2019 [cited 2019 Jan 10]. Available from: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/economicas/agricultura-e-pecuaria/21814-2017-censo-agropecuario.html?=&t=resultados

» https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/economicas/agricultura-e-pecuaria/21814-2017-censo-agropecuario.html?=&t=resultados - Lobato J, Silva DA, Mineo TW, Amaral JD, Segundo GR, Costa-Cruz JM, et al. Detection of immunoglobulin G antibodies to Neospora caninum in humans: high seropositivity rates in patients who are infected by human immunodeficiency virus or have neurological disorders. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2006; 13(1): 84-89. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CVI.13.1.84-89.2006 PMid:16426004.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CVI.13.1.84-89.2006 - Macchi MV, Suanes A, Salaberry X, Fernandez F, Piaggio J, Gil AD. Epidemiological study of neosporosis in Uruguayan dairy herds. Prev Vet Med 2020; 179: 105022. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2020.105022 PMid:32407996.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2020.105022 - Mainar-Jaime RC, Thurmond MC, Berzal-Herranz B, Hietala SK. Seroprevalence of Neospora caninum and abortion in dairy cows in northern Spain. Vet Rec 1999; 145(3): 72-75. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/vr.145.3.72 PMid:10460027.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/vr.145.3.72 - Maldonado Rivera JE, Vallecillo AJ, Pérez CL, Cirone KM, Dorsch MA, Morrell EL, et al. Bovine neosporosis in dairy cattle from the southern highlands of Ecuador. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Reports 2020; 20: 100377. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vprsr.2020.100377 PMid:32448544.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vprsr.2020.100377 - Martins AA, Zamprogna TO, Lucas TM, Cunha IL, Garcia JL, Silva AV. Frequency and risk factors for infection by Neospora caninum in dairy farms of Umuarama, PR, Brazil. Arq Ciênc Vet Zool 2012; 15(2): 137-142.

- Minervino AHH, Ragozo AMA, Monteiro RM, Ortolani EL, Gennari SM. Prevalence of Neospora caninum antibodies in cattle from Santarem, Pará, Brazil. Res Vet Sci 2008; 84(2): 254-256. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2007.05.003 PMid:17619028.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2007.05.003 - Moloney BJ, Heuer C, Kirkland PD. Neospora caninum in beef herds in New South Wales, Australia. 2: analysis of risk factors. Aust Vet J 2017; 95(4): 101-109. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/avj.12563 PMid:28346670.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/avj.12563 - Nematollahi A, Jaafari R, Moghaddam G. Seroprevalence of Neospora caninum Infection in Dairy Cattle in Tabriz, Northwest Iran. Iran J Parasitol 2011; 6(4): 95-98. PMid:22347319.

- Otranto D, Llazari A, Testini G, Traversa D, di Regalbono AF, Badan M, et al. Seroprevalence and associated risk factors of neosporosis in beef and dairy cattle in Italy. Vet Parasitol 2003; 118(1-2): 7-18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.10.008 PMid:14651870.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.10.008 - Paré J, Fecteau G, Fortin M, Marsolais G. Seroepidemiologic study of Neospora caninum in dairy herds. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1998; 213(11): 1595-1598. PMid:9838960.

- Peel MC, Finlayson BL, McMahon TA. Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 2007; 11(5): 1633-1644. http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007

» http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007 - QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System [online]. Chicago: Open Source Geospatial Foundation; 2020 [cited 2020 Jun 8]. Available from: https://www.qgis.org/pt_BR/site/#

» https://www.qgis.org/pt_BR/site/# - Ragozo AMA, Paula VSO, Souza SLP, Bergamaschi DP, Gennari SM. Ocorrência de anticorpos anti-Neospora caninum em soros de bovinos procedentes de seis estados brasileiros. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2003; 12(1): 33-37.

- Reichel MP, Alejandra Ayanegui-Alcérreca M, Gondim LFP, Ellis JT. What is the global economic impact of Neospora caninum in cattle - the billion dollar question. Int J Parasitol 2013; 43(2): 133-142. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.10.022 PMid:23246675.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.10.022 - Ribeiro CM, Soares IR, Mendes RG, de Santis Bastos PA, Katagiri S, Zavilenski RB, et al. Meta-analysis of the prevalence and risk factors associated with bovine neosporosis. Trop Anim Health Prod 2019; 51(7): 1783-1800. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11250-019-01929-8 PMid:31228088.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11250-019-01929-8 - Rivero S, Almeida O, Ávila S, Oliveira W. Pecuária e desmatamento: uma análise das principais causas diretas do desmatamento na Amazônia. Nova Econ 2009; 19(1): 41-66. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-63512009000100003

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-63512009000100003 - Rosypal AC, Lindsay DS. The sylvatic cycle of Neospora caninum: where do we go from here? Trends Parasitol 2005; 21(10): 439-440. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2005.08.003 PMid:16098812.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2005.08.003 - Schares G, Barwald A, Staubach C, Wurm R, Rauser M, Conraths FJ, et al. Adaptation of a commercial ELISA for the detection of antibodies against Neospora caninum in bovine milk. Vet Parasitol 2004a; 120(1-2): 55-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.11.016 PMid:15019143.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.11.016 - Schares G, Barwald A, Staubach C, Ziller M, Kloss D, Schroder R, et al. Potential risk factors for bovine Neospora caninum infection in Germany are not under the control of the farmers. Parasitology 2004b; 129(Pt 3): 301-309. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0031182004005700 PMid:15471005.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0031182004005700 - Schares G, Barwald A, Staubach C, Ziller M, Kloss D, Wurm R, et al. Regional distribution of bovine Neospora caninum infection in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate modelled by Logistic regression. Int J Parasitol 2003; 33(14): 1631-1640. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7519(03)00266-2 PMid:14636679.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7519(03)00266-2 - Silva JB, Nicolino RR, Fagundes GM, dos Anjos Bomjardim H, dos Santos Belo Reis A, da Silva Lima DH, et al. Serological survey of Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii in cattle (Bos indicus) and water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) in ten provinces of Brazil. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 2017; 52: 30-35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cimid.2017.05.005 PMid:28673459.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cimid.2017.05.005 - Silva MIS, Almeida MÂO, Mota RA, Pinheiro JW Jr, Rabelo SSDA. Fatores de riscos associados à infecção por Neospora caninum em matrizes bovinas leiteiras em Pernambuco. Cienc Anim Bras 2008; 9(2): 455-461.

- Sun WW, Meng QF, Cong W, Shan XF, Wang CF, Qian AD. Herd-level prevalence and associated risk factors for Toxoplasma gondii, Neospora caninum, Chlamydia abortus and bovine viral diarrhoea virus in commercial dairy and beef cattle in eastern, northern and northeastern China. Parasitol Res 2015; 114(11): 4211-4218. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-015-4655-0 PMid:26231838.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00436-015-4655-0 - Thrusfield M. Veterinary epidemiology. 3rd ed. Cambridge: Blackwell Science; 2005.

- von Blumröder D, Schares G, Norton R, Williams DJL, Esteban-Redondo I, Wright S, et al. Comparison and standardisation of serological methods for the diagnosis of Neospora caninum infection in bovines. Vet Parasitol 2004; 120(1-2): 11-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.12.010 PMid:15019139.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.12.010 - Wapenaar W, Barkema HW, Vanleeuwen JA, McClure JT, O’Handley RM, Kwok OC, et al. Comparison of serological methods for the diagnosis of Neospora caninum infection in cattle. Vet Parasitol 2007; 143(2): 166-173. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.08.007 PMid:16989951.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.08.007 - Wouda W, Bartels CJM, Moen AR. Characteristics of Neospora caninum-associated abortion storms in dairy herds in The Netherlands (1995 to 1997). Theriogenology 1999; 52(2): 233-245. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0093-691X(99)00125-9 PMid:10734391.

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0093-691X(99)00125-9

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

12 Feb 2021 -

Date of issue

2021

History

-

Received

28 Sept 2020 -

Accepted

03 Dec 2020