Abstract

This work describes the foraging techniques, body positions and behavior of free-ranging Ingram's squirrel Guerlinguetus ingrami Thomas, 1901 in a region of the Araucaria moist forest, in the Atlantic Forest of southern Brazil. The animals were observed using the "all occurrence sampling" method with the aid of binoculars and a digital camcorder. All behaviors were described in diagrams and an ethogram. We recorded five basic body positions, 24 behaviors, two food choices, and three feeding strategies utilized to open fruits of Syagrus romanzoffiana (Cham.), the main food source of Ingram's squirrels. We also observed a variance in the animals' stance, which is possibly influenced by predation risk, and discuss the causes of some behaviors.

Atlantic forest; body position; ethogram; Syagrus romanzoffiana

BEHAVIOR

Behavior and foraging technique of the Ingram's squirrel Guerlinguetus ingrami (Sciuridae: Rodentia) in an Araucaria moist forest fragment

Calebe Pereira MendesI,* * Corresponding author. E-mail: calebepm3@hotmail.com ; José Flávio Cândido-JrII

ILaboratório de Biologia da Conservação, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade Estadual Paulista "Júlio de Mesquita Filho". Avenida 24 A 1515, 13506-900 Rio Claro, São Paulo, Brazil

IILaboratório de Zoologia dos Vertebrados e Biologia da Conservação, Centro de Ciências Biológicas e Saúde, Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná. Rua Universitária 1619, 85819-110 Cascavel, PR, Brazil

ABSTRACT

This work describes the foraging techniques, body positions and behavior of free-ranging Ingram's squirrel Guerlinguetus ingrami Thomas, 1901 in a region of the Araucaria moist forest, in the Atlantic Forest of southern Brazil. The animals were observed using the "all occurrence sampling" method with the aid of binoculars and a digital camcorder. All behaviors were described in diagrams and an ethogram. We recorded five basic body positions, 24 behaviors, two food choices, and three feeding strategies utilized to open fruits of Syagrus romanzoffiana (Cham.), the main food source of Ingram's squirrels. We also observed a variance in the animals' stance, which is possibly influenced by predation risk, and discuss the causes of some behaviors.

Key words: Atlantic forest; body position; ethogram; Syagrus romanzoffiana

Ingram's squirrel, Guerlinguetus ingrami Thomas, 1901, sometimes considered a subspecies of G. aestuans or placed in Sciurus (ALLEN 1915, MOOJEN 1942) and commonly known as Atlantic Forest squirrel or "serelepe", is one of 11 species of Sciuridae documented in Brazil (REIS et al. 2011). The species occurs from southeastern Bahia to northern Rio Grande do Sul and is arboreal and diurnal, inhabiting primary or secondary growth areas of the Atlantic Forest and "Cerrado" (BONVICINO et al. 2008). Despite its wide distribution throughout Brazil, 'the elusive habits of this squirrel make it difficult to unravel various aspects of its biology. The little available information about the diet of G. ingrami indicates that it is composed mainly of fruits and seeds, but it may also include flowers, tree bark, mushrooms, lichens, moss, bird eggs, leaves and insects (BORDIGNON et al. 1996, MIRANDA 2005, RIBEIRO et al. 2009, 2010).

The Atlantic Forest squirrel is often associated with the queen palm, Syagrus romanzoffiana (Cham.) Glassman. The abundance of this palm influences the location of squirrel nests (ALVARENGA & TALAMONI 2005). The S. romanzoffiana is also an important resource for G. ingrami even in areas where the palm is not abundant, because the palm's fruits may comprise a large portion of the squirrel's diet, in particular seasons and regions (GALETTI et al. 1992, PASCHOAL & GALETTI 1995). In all tropical areas where they occur, sciurids are both seed predators and seed dispersers (STONER et al. 2007). However, since the ecological interactions of a particular species is dependent on its behavioral patterns (MCCONKEY & DRAKE 2006, ORROCK & DANIELSON 2005), and the behavior and ecology of G. ingrami in the wild are still largely unknown (ALVARENGA & TALAMONI 2005, MIRANDA 2005), this study aimed to record the behavioral and foraging patterns of G. ingrami in an Araucaria moist forest fragment in southern Brazil.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The study was conducted between April 2010 and September 2011 in a forest fragment on the São Domingos farm (25º01'37"S, 53º20'57"W) and its surroundings in Cascavel, Paraná, Brazil. The fragment is approximately 1,300 ha in size and is connected to other smaller fragments though riparian forests. The region is primarily composed of Araucaria moist forest at various levels of degradation, but with plots of Pinus spp. and Eucaliptus spp. The average annual precipitation in the region is 1,800 mm and the average annual temperature is 19ºC. The climate is classified as Cfa according to the Köpper climate classification (IAPAR 2000).

Observations were made during eighteen months, with a mean of 2.5 (sd = 1.09) surveys per month except for July 2011 when there was no sampling. The surveys were made between 08:00 a.m. and 01:30 p.m. and occasionally (five surveys) between 01:00 p.m. and 07:00 p.m., the periods of higher levels of activity for this species (BORDIGNON & MONTEIRO-FILHO 2000), totaling 160 hours of field effort. The surveys were conducted by walking along two trails (1.5 and 2 km in length) and two rural roads (1.5 and 0.5 km), searching for animals with the help of binoculars (8 x 40 mm). The sightings were filmed with a Sony DCR-SR47 camcorder on a tripod, in order to later analyze, describe, and score the behaviors. The list of behaviors for the species was elaborated using the "all occurrence sampling" method (DEL-CLARO 2004), and the data were organized in an ethogram. Seasonal analyses were not carried out because this was not the objective of the study. No animals were captured or marked in the study, but considering the small home range of the specie (BORDIGNON & MONTEIROFILHO 2000), it is possible that we observed at least six different animals.

To better understand the foraging techniques of G. ingrami feeding on fruits of S. romanzoffiana, fruits with predation marks were collected, washed and measured, and the predation marks were compared with one another.

RESULTS

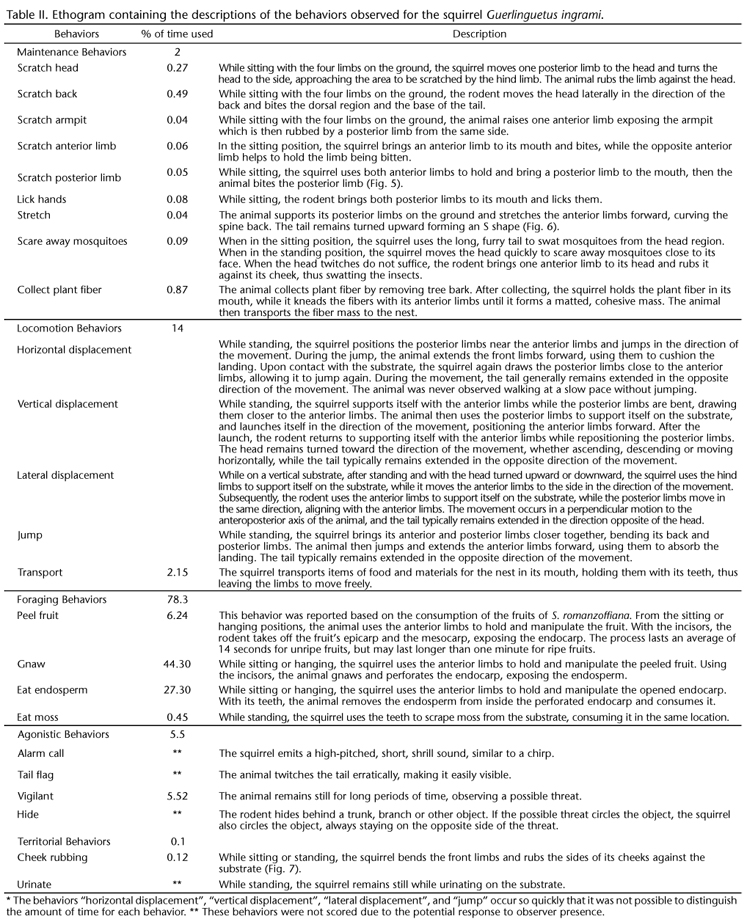

The field effort resulted in 16 sightings, five hours and a half of observations and three hours and forty minutes of footage. Five basic body positions were recorded (Table I, Figs 1-4) and 24 behaviors were observed (Table II, Figs 5-7), which were divided into the following categories: maintenance, locomotion, foraging, agonistic, and territorial.

Throughout the study, the squirrels were observed eating two food items: fruits from the palm S. romanzoffiana and an unidentified moss. The consumption of bryophytes was observed only for one juvenile squirrel in December, while the fruits of S. romanzoffiana were consumed throughout the year. Although the squirrels mainly eat the endosperm of ripe and unripe fruits, they were also seen eating the epicarp and mesocarp of ripe fruits in December.

Three strategies for opening S. romanzoffiana fruits were identified in the visual records. The principal method, observed 50% (n = 28) of the time, consisted of cutting a triangular opening from the germination pore on the endocarp (Fig. 8). The second most utilized strategy, recorded 16.7% of the time, consisted of cutting along the circumference of the fruit, dividing it into two pieces (Fig. 9). In 33.3% of the visual records, it was not possible to identify the strategy utilized by the animal. However from the eaten fruits, it was possible to distinguish a strategy that consisted of making various incisions side by side, which resulted in a single opening.

We observed that the process of opening the endocarp with the triangular opening strategy in 95.5% (n = 534) of the cases was performed on the opposite side of the inner gibbosity of the endocarp, where the endocarp is thinner and allows access to the fruit's endosperm (Fig. 10). This process lasts an average of 70 seconds (n = 18, sd ± 20), followed by the animal taking an average of 83 seconds (n = 19, sd ± 31) to eat the fruit's endosperm. The area of the triangular opening is not correlated with fruit size (Pearson correlation test, r = 0.02, df = 512, p = 0.61). We also observed that all of the individuals who used the triangular opening strategy were adults, and only one adult individual did not use this technique.

DISCUSSION

Basic body positions

In the current study, we observed that the "sitting" body position (Fig. 2) differed from the reports in the literature. BORDIGNON & MONTEIRO-FILHO (1997) found that when in the "sitting" position the anteroposterior axis of the animal stayed close to 45º relative to the substrate, but in our study an angle of approximately 20º was observed, and it rarely reached 30º. Given that the authors studied captive animals (BORDIGNON & MONTEIROFILHO 1997), the difference in angle may occur because of the predation risk that wild animals face. In this case, maintaining the body closer to the substrate may reduce the chance of being detected by potential predators. The "sitting" body position is also known in the literature as "Position of lying" often used when the animal feels threatened (RIBEIRO et al. 2009).

In addition to assuming a position closer to the substrate, the behavior of maintaining the tail pointing forward above the dorsal region and head instead of the S shape while sitting, may also be a strategy to prevent the predator from delimiting the animal's body position, thus minimizing its detection. The behavior of maintaining the tail pointing forward instead of in the S shape while in the sitting position appears to have no connection with the thermoregulatory behavior exhibited by other sciurids. For example, the Cape ground squirrel Xerus inauris (Zimmermann, 1780) (FICK et al. 2009) appears to use the tail to make shade, whereas in the current study the animals also exhibit this behavior in the shade. This supports the hypothesis that the tail may be used as camouflage. The use of the elongated, bristly tail in a disruptive way, the cryptic coloration, the small size, and the "hide" and "vigilant" behaviors turns the squirrel into a very discrete species in its natural environment, and this significantly reduces the risk of predation.

The "alert position" reported in our study differs from the "Attack position" reported by RIBEIRO et al. (2009) in that only the tail that remains aligned with the animal's anteroposterior axis, but both positions are used in agonistic situations. The "standing" (Fig. 1), "lying down" (Fig. 3) and "suspended" (Fig. 4) positions were also documented by other authors (BORDIGNON et al. 1996, BORDIGNON & MONTEIRO-FILHO 1997, RIBEIRO et al. 2009).

Feeding behavior and diet

The variety of food sources reported in this study was quite different from those registered in the literature. While in our study only two types of food were consumed, MIRANDA (2005) reported 10, PASCHOAL & GALETTI (1995) 14, and BORDIGNON & MONTEIRO-FILHO (1999) 13 different types of food sources. It is possible that detecting this difference could be an artifact caused by the relatively small sample size of the present study. Both PASCHOAL & GALETTI (1995) and BORDIGNON & MONTEIRO-FILHO (1999) did more than 1,000 hours of field effort, however, MIRANDA (2005) registered only 25 sightings with less than four hours of naturalistic observations and also registered more food types than the present work.

Another possibility is that the weighted consumption of S. romanzoffiana may result from the abundance of this fruit, and its presence in every month of the year at the study site. In addition, it has been well-documented in the literature that the queen palm is an important part of the diet of G. ingrami. PASCHOAL & GALETTI (1995) found that during August, the queen palm accounted for 90% of the reported food sources of G. ingrami. Intense consumption of S. romanzoffiana was also reported by various other authors (ALVARENGA & TALAMONI 2006, BORDIGNON et al. 1996, BORDIGNON & MONTEIRO-FILHO 1999, MIRANDA 2005). Other possible food sources are present at the study site, but were apparently not consumed by the squirrels. For instance, the pine Araucaria angustifolia, a species that is consumed by G. ingrami according to other studies (BORDIGNON & MONTEIRO-FILHO 1999, MIRANDA 2005), was not found to be eaten by the animals.

The fact that only adult individuals used the triangular opening strategy for fruits indicates that this behavior is learned (ADES & BUSCH 2000). How the animal identifies the side opposite of the fruit's inner gibbosity before opening it is still not well understood, since externally the endocarps have tri-radial symmetry with three very similar holes.

Given that only one of the three holes is the functional germination pore, located opposite to the inner gibbosity, and the other two are merely cavities that do not extend to the center, BORDIGNON et al. (1996) proposed that the animal tries to penetrate these holes with the incisors to identify which of them is the germination pore. MAIA et al. (1987) suggested that the animals may identify the germination pore by the small asymmetries in the hole. However, in the present study, we observed that the animals rarely clean out the fruit completely and do not expose all of the pores to allow for a comparison of their locations.

Territorial and agonistic behavior

All of the vocalizations of G. ingrami reported in this study were made in agonistic situations, often coupled with "vigilant", "tail flag", and "alert position" behaviors. The vocalizations may serve to warn the predator that it has been detected, thus discouraging an attack; to alert other individuals of the presence of a potential threat; and/or to distract the predator's attention while other animals escape or remain still among branches (SOLÓRZANO-FILHO 2006). However, with one exception, the present study detected this behavior only in animals that appeared to be alone.

The "cheek-rubbing" behavior is also called "face-wiping" or "territorial marking" in the literature (BORDIGNON et al. 1996, HALLORAN & BEKOFF 1995). According to RIBEIRO et al. (2009), during this behavior, the squirrel deposits secretions from the gland in the oral-labial region on a given substrate. Despite this, the function of this behavior is controversial, as various authors classify it as a form of marking territory, while others believe it is part of grooming behavior. In a study with Abert's squirrels Sciurus aberti Woodhouse, 1853, HALLORAN & BEKOFF (1995) showed that the facial marking behavior is more related to grooming than to territorial marking, but they did not reject a territorial function for the behavior. The authors claim that the facial marking behavior of S. aberti may have a secondary territorial function, and that the functions of this behavior may vary among species. The function of the facial marking behavior of

G. ingrami has not been evaluated, and during our study we observed this behavior both during foraging and agonistic situations, which supports the idea that the behavior has more than one function, as was also observed for S. aberti.

Our study recorded a broad spectrum of behaviors performed by G. ingrami in the wild. Some are similar to behaviors already documented in the literature, and others present differences with important implications. For instance, the basic body positions potentially vary in response to predation risk; therefore studying the proximate causes of these variations would be quite useful to better understand the evolution of the species' behavior. It is quite probable that the facial marking behavior of this species has two functions, territorial and maintenance, but more specific research is necessary to evaluate these hypotheses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Parque Tecnológico Itaipu for the financial support, the Laboratório de Zoologia dos Vertebrados e Biologia da Conservação of the Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná Campus Cascavel, and to Cássio Stringari, owner of the study area.

LITERATURE CITED

Submitted: 16.X.2013;

Accepted: 04.V.2013

Editorial responsibility: Diego Astúa de Moraes

All content of the journal, except where identified, is licensed under a Creative Commons attribution-type BY-NC.

- ADES, C. & S.E. BUSCH. 2000. A aprendizagem do descascamento de sementes pelo camundongo Calomys callosus (Rodentia, Cricetidae). Revista Brasileira de Zoociências 2 (1): 31-44.

- ALLEN, J.A. 1915. Review of the South American Sciuridae. Bulletin American Museum of Natural History 34: 147-309.

- ALVARENGA, C.A. & S.A. TALAMONI. 2005. Nests of the Brazilian squirrel Sciurus ingrami Thomas (Rodentia, Sciuridae). Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 22 (3): 816-818. doi: 10.1590/S0101-81752005000300048.

- ALVARENGA, C.A. & S.A. TALAMONI. 2006. Foraging behaviour of the Brazilian squirrel Sciurus aestuans (Rodentia, Sciuridae). Acta Theriologica 51 (1): 69-74. doi: 10.1007/BF03192657.

- BONVICINO, C.R.; J.A. OLIVEIRA & P.S D'ANDREA. 2008. Guia dos Roedores do Brasil, com chaves para gêneros baseadas em caracteres externos Rio de Janeiro, Centro Pan-Americano de Febre Aftosa OPAS/OMS. ISSN: 0101-6970.

- BORDIGNON, M.; T.C.C. MARGARIDO & R.R. LANGE. 1996. Formas de abertura dos frutos de Syagrus romanzoffiana (Chamisso) Glassman efetuadas por Sciurus ingrami Thomas (Rodentia, Sciuridae). Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 13 (4): 821-828. doi: S0101-81751996000400002.

- BORDIGNON, M. & E.L.A. MONTEIRO-FILHO. 1997. Comportamentos e atividade diária de Sciurus ingrami (Thomas) em cativeiro (Rodentia, Sciuridae). Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 14 (3): 707-722. doi: 10.1590/S0101-81751997000300019.

- BORDIGNON, M. & E.L.A. MONTEIRO-FILHO. 1999. Seasonal food resources of the squirrel Sciurus ingrami in a secondary araucaria forest in southern Brazil. Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment 34: 137-140. doi: 10.1076/snfe.34.3.137.8910.

- BORDIGNON, M. & E.L.A. MONTEIRO-FILHO. 2000. Behaviour and daily activity of the squirrel Sciurus ingrami in a secondary araucaria forest in southern Brazil. Canadian Journal of Zoology 78: 1732-1739. doi: 10.1139/z00-104.

- DEL-CLARO, K. 2004. Comportamento animal Uma introdução à ecologia comportamental Jundiaí, Conceito. ISBN: 85-89874-02-8.

- FICK, L.G.; T.A. KUCIO; A. FULLER; A. MATTHEE & D. MITCHELL. 2009. The relative roles of the parasol-like tail and burrow shuttling in thermoregulation of free-ranging Cape ground squirrels, Xerus inauris Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, Part A 152 (3): 334-340. doi: 10.1016/ j.cbpa.2008.11.004.

- GALETTI, M.; M. PASCHOAL & F. PEDRONI. 1992. Predation on palm nuts (Syagrus romanzoffiana) by squirrels (Sciurus ingrami) in south-east Brazil. Journal of Tropical Ecology 8 (1): 121-123. doi: 10.1017/S0266467400006210.

- HALLORAN, M.E. & M. BEKOFF. 1995. Cheek rubbing as grooming by Abert squirrels. Animal Behaviour 50: 987-993. doi: 10.1016/0003-3472(95)80099-9.

- IAPAR. 2000. Cartas climáticas do estado do Paraná Londrina, Instituto Agronômico do Paraná

- MAIA, A.A.; F.P. SERRAN; H.Q.B. FERNANDES; R.R. OLIVEIRA; R.F. OLIVEIRA & T.M.P.A. PENNA. 1987. Inferências faunísticas por vestígios vegetais. III: Inter-relações do caxinguelê (Sciurus aestuans ingrami, Thomas 1901) com a palmeira baba-deboi (Syagrus romanzoffiana (Chamisso) Glassman). Atas da Sociedade Botânica do Brasil, Secção Rio de janeiro 3 (11): 89-96.

- MCCONKEY, K.R. & D.R. DRAKE. 2006. Flying foxes cease to function as seed dispersers long before they become rare. Ecology 87 (2): 271-276. doi: 10.1890/05-0386.

- MIRANDA, J.M.D. 2005. Dieta de Sciurus ingrami Thomas (Rodentia, Sciuridae) em um remanescente de floresta com Araucária, Paraná, Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 22 (4): 1141-1145. doi: 10.1590/S0101-81752005000400047.

- MOOJEN, J. 1942. Sobre os "ciurídeos" das coleções do Museu Nacional, do Departamento de Zoologia de S. Paulo e do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi. Boletim do Museu Nacional, Zoologia 1: 55.

- ORROCK, J.L.; DANIELSON B.J. 2005. Patch shape, connectivity, and foraging by oldfield mice (Peromyscus polionotus). Journal of Mammalogy 86: 569-575. doi: 10.1644/1545-1542(2005) 86[569:PSCAFB]2.0.CO;2.

- PASCHOAL, M. & M. GALETTI. 1995. Seasonal food use by the neotropical squirrel Sciurus ingrami in southeastern Brazil. Biotropica 27 (2): 268-273. doi: 10.2307/2389006.

- REIS, N.R.; A.L. PERACCHI; W.A. PEDRO & I.P. LIMA. 2011. Mamíferos do Brasil Londrina, Universidade Estadual de Londrina, 2nd ed.

- RIBEIRO, L.F.; L.O.M. CONDE; L.C. GUZZO & P.R PAPALAMBROPOULOS. 2009. Behavioral patterns of Guerlinguetus ingrami (Thomas, 1901) from three natural populations in Atlantic forest fragments in Espirito Santo state, Southeastern Brazil. Natureza on line 7 (2): 92-96. Available online at: http://www.naturezaonline.com.br/natureza/conteudo/pdf/06_RibeiroLFetal_9296.pdf [Accessed: 01/IX/ 2013]

- RIBEIRO, L.F.; L.O.M. CONDE & M. TABARELLI. 2010. Predação e remoção de sementes de cinco espécies de palmeiras por Guerlinguetus ingrami (Thomas, 1901) em um fragmento urbano de floresta Atlântica montana. Árvore 34 (4): 637-649. doi: 10.1590/S0100-67622010000400008.

- SOLÓRZANO-FILHO, J.A. 2006. Mobbing of Leopardus wiedii while hunting by a group of Sciurus ingrami in an Araucaria forest of Southeast Brazil. Mammalia 70: 156-157. doi: 10.1515/ MAMM.2006.031.

- STONER K.E.; P. RIBA-HERNÁNDEZ; K. VULINEC; J.E. LAMBERT. 2007. The Role of Mammals in Creating and Modifying Seedshadows in Tropical Forests and Some Possible Consequences of Their Elimination. Biotropica 39: 316-327. doi: 10.1111/j.17447429.2007.00292.x.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

04 July 2014 -

Date of issue

June 2014

History

-

Accepted

04 May 2013 -

Received

16 Oct 2013