Abstract

In the larval stage, bruchines can cause several damages to the seeds of their host plants due to the consumption of the embryo. The aim of this study was to identify the species of seed-feeding insects in Senna corymbosa (Fabaceae) and quantify the damage caused to seeds. For this purpose, ripe fruits of S. corymbosa were collected monthly from May to August 2014. The fruits were stored in containers to obtain the adult insects and quantify the damage to the seeds. A total of 3,548 seed beetles emerged from the fruits, around 89% belonging to Sennius lateapicalis. Insects consume up to 43.2% of the internal seed content. Moreover, the seed beetles Hymenoptera parasitoids emerged. In this study, seed-feeding insects are recorded for the first time in S. corymbosa. In addition, it contributes to describing fruits and seeds, as well as associated bruchine species and the damage they cause to seeds.

Keywords:

forest entomology; parasitoids; seed predation; seed beetles; Sennius

1. INTRODUCTION AND OBJECTIVES

Several species of Senna have been the focus of studies on seed-feeding insects that cause damage to seeds (Ribeiro-Costa, 1998Ribeiro-Costa CS. Observations on the biology of Amblycerus submaculatus (Pic) and Sennius bondari (Pic) (Coleoptera: Bruchidae) in Senna alata (L.) Roxburgh (Caesalpinaceae). The Coleopterists Bulletin 1998; 52(1): 63-69.; Linzmeier et al., 2004Linzmeier AM, Ribeiro-Costa CS, Caron E. Comportamento e ciclo de vida de Sennius bondari (Pic) (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae, Bruchinae) em Senna macranthera (Collad.) Irwin & Barn. (Caesalpinaceae). Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 2004; 21(2): 351-356.; Sari & Ribeiro-Costa, 2005Sari LT, Ribeiro-Costa CS. Predação de sementes de Senna multijuga (Rich.) H. S. Irwin & Barneby (Caesalpinaceae) por bruquíneos (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Neotropical Entomology 2005; 34(3): 521-525.; Sari et al., 2005Sari LT, Ribeiro-Costa CS, Roper JJ. Dinâmica populacional de bruquíneos (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae) em Senna multijuga (Rich.) H. S. Irwin & Barneby (Caesalpinaceae). Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 2005; 22(1): 169-174.; Wolowski & Freitas, 2011Wolowski M, Freitas L. Reproduction, pollination and seed predation of Senna multijuga (Fabaceae) in two protected areas in the Brazilian Atlantic forest. Revista de Biología Tropical 2011; 59(4): 1939-1948.; Modena et al., 2012Modena ES, Pires ACV, Barônio GJ, Inforzato I, Demczuk SDB. Do fruit traits of the Senna occidentalis weed influence seed predation by Bruchinae? Revista Brasileira de Biociências 2012; 10(3): 293-297.; Viana & Ribeiro-Costa, 2013Viana JH, Ribeiro-Costa CS. Bruchines (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) associated with Senna neglecta (Vogel) H.S. Irwin and Barneby (Fabaceae: Caesalpinioideae): a new host plant for the subfamily. Journal Natural History 2013; 48(1-2): 57-85.; Viana & Ribeiro-Costa, 2014Viana JH, Ribeiro-Costa CS. Two new Brazilian Sennius species near the guttifer group (Coleoptera:Chrysomelidae:Bruchinae). The Florida Entomologist 2014; 97(3): 1108-1114.). Among the granivorous insects, Bruchinae (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) can act as agent of natural selection, influencing the population size and the spatial distribution of the plants, due to the partial or total consumption of the seeds, which may harm the reproductive potential of the species (Ribeiro-Costa & Almeida, 2012Ribeiro-Costa CS, Almeida LM. Seed-Chewing Beetles (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae, Bruchinae). In: Panizzi AR, Parra JRP, editores. Insect Bioecology and Nutrition for Integrated Pest Management. Brasília: Embrapa Informação Tecnológica; 2012.). As forest seeds have high nutrient content, they favor the development of larvae from several seed-feeding insect species in their interior (Costa et al., 2018Costa EC, Cantarelli EB, Boscardin J, Fleck MD. Insetos-praga de sementes e mudas em viveiros florestais. In: Araujo MM, Navroski MC, Schorn LA, editores. Produção de sementes e mudas: um enfoque à silvicultura. Santa Maria: Editora UFSM; 2018.), such as legume seeds belonging to Senna corymbosa (Lam.) H. S. Irwin & Barneby (Fabaceae) that are consumed by different species of Amblycerus (Ribeiro-Costa et al., 2018Ribeiro-Costa CS, Manfio D, Morse, GE. Catalog for the Brazilian Amblycerus Thunberg (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae: Bruchinae) with taxonomic notes, host plants associations and distributional records. Zootaxa 2018; 4388(4): 499-525.).

The species S. corymbosa is an easily cultivated ornamental plant and has long lasting flowering and abundant fruiting. It is used in urban greening due to its size, which can reach up to three meters in height (Miotto et al., 2008Miotto STS, Lüdke R, Oliveira MLAA. A família Leguminosae no Parque Estadual de Itapuã, Viamão, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Biociências 2008; 6(3): 269-290.). In Brazil, its flowering occurs in the months of March and April, with fruiting in May (Flora, 2020Flora. Digital do Rio Grande do Sul e Santa Catarina. 2020. [cited 2020 may. 04]. Available from: Available from: http://www.ufrgs.br/fitoecologia/florars/open_sp.php?img=8309

http://www.ufrgs.br/fitoecologia/florars...

). This plant species is native from South America, occurring in Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay and Brazil. However, it is also cultivated in the United States of America, in several countries of Europe, and in China (Irwin & Barneby, 1982Irwin HS, Barneby RC. The American Cassinae, a synoptical revision of Leguminosae, Tribe Cassieae, subtribe Cassinae in the New World. Memoires of the New York Botanical Garden 1982; 35: 1-918.; Fortunato, 1999Fortunato RH. Senna. In: Zuloaga F, Morrone O, editores. Catalogo de las Plantas Vasculares de la Republica Argentina, II (A-E) & (F-Z). Monographies Systematic of the Missouri Botanical Garden 1999; 74.; Lin & Li, 2011Lin CM, Li YY. Floral syndrome and breeding system of Senna (Cassia) corymbosa. African Journal of Biotechnology 2011; 10(25): 4988-4995.). In Brazil, S. corymbosa is found in the Central-west (Mato Grosso do Sul), Southeast (Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo) and South (Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina) regions (Reflora, 2020Reflora. Senna corymbosa. In: Herbário Virtual. [cited 2020 apr. 30]. Available from: Available from: http://reflora.jbrj.gov.br/reflora/herbarioVirtual

.

http://reflora.jbrj.gov.br/reflora/herba...

). In Rio Grande do Sul, this plant species is widely found growing in sandy or humid fields, in secondary vegetation, and in forest edges (Rodrigues et al., 2005Rodrigues RS, Flores AS, Miotto STS, Baptista LRM. O gênero Senna (Leguminosae, Caesalpinioideae) no Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Acta Botanica Brasilica 2005; 19(1): 1-16.).

The floral biology of the species is mainly associated with floral visitors belonging to Bombus atratus (Franklin, 1913) (Laporta, 2005Laporta C. Floral biology and reproductive system of enantiostylous Senna corymbosa (Caesalpiniaceae). Revista de Biología Tropical 2005; 53(1-2): 49-61.). In China, the occurrence of species of the orders Hymenoptera, Lepidoptera, Mantodea, Diptera, and Coleoptera was reported visiting the flowers. Among the Coleoptera, the Chrysomelidae family occasionally visits the flowers; however, they are not considered effective pollinators (Lin & Li, 2011Lin CM, Li YY. Floral syndrome and breeding system of Senna (Cassia) corymbosa. African Journal of Biotechnology 2011; 10(25): 4988-4995.). Their fruits are cylindrical, glabrous, indehiscent, pendulous legumes, 8-10 cm long with brownish seeds (Rodrigues et al., 2005Rodrigues RS, Flores AS, Miotto STS, Baptista LRM. O gênero Senna (Leguminosae, Caesalpinioideae) no Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Acta Botanica Brasilica 2005; 19(1): 1-16.).

Senna corymbosa is related to environmental and ecosystem services being used by farmers as green manure and to improve soil quality. In addition, it has apicultural importance in the production of honey by Apidae Meliponini (Gomes et al., 2019Gomes GC, Gomes JCC, Barbieri RL, Miura AK, Sousa LP. Environmental and Ecosystem Services, Tree Diversity and Knowledge of Family Farmers. Floresta e Ambiente 2019; 26: e20160314.), since the flowers are yellow-gold colored, which attract pollinating insects (Rodrigues et al., 2005Rodrigues RS, Flores AS, Miotto STS, Baptista LRM. O gênero Senna (Leguminosae, Caesalpinioideae) no Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Acta Botanica Brasilica 2005; 19(1): 1-16.). This species also presents medicinal properties among its characteristics (Simões et al., 1995Simões CMO, Mentz LA, Schenkel EP, Irgang BE, Stehmann JR. Plantas da Medicina Popular no Rio Grande do Sul. 4 ed. Porto Alegre: Editora da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul; 1995.).

Nonetheless, in addition to the apicultural and medicinal importance of this plant species, no studies were found in the literature regarding the interaction of this plant with seed-feeding insects that cause damage to seeds in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. This knowledge related to seed-feeding insects is extremely important, since these insects interfere in the dynamics, distribution, life cycle, and evolution of plants due to their consumption and consequent damage to seeds, thus limiting their supply to the environment (Ribeiro-Costa & Almeida, 2009Ribeiro-Costa CS, Almeida LM. Bruchinae (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). In: Panizzi AR, Parra JRP, editores. Bioecologia e nutrição de insetos: base para o manejo integrado de pragas. Brasília: Embrapa Informação Tecnológica; 2009.). However, the degree of seed predation attributed to bruchines is quite variable in space and time, and is strictly dependent on the host plant (Klips et al., 2005Klips RA, Sweeney PM, Bauman EKK, Snow AA. Temporal and geographic variation in predispersal seed predation on Hibiscus moscheutos L. (Malvaceae) in Ohio and Maryland, USA. American Midland Naturalist 2005; 154: 286-295.). Studies on damage caused by granivorous insects in host plants are crucial for the ecological management of economically important plants, such as S. corymbosa. Thus, the aim of this study is to report the occurrence of species of seed-feeding insects in S. corymbosa and quantify the damages caused in their seeds.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

An experiment was conducted in a rural property in the municipality of São Sepé, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil (30°12’24”S; 53°34’30”W). The climate in the region is characterized as humid subtropical (Cfa), according to Köppen classification (Alvares et al., 2013Alvares CA, Stape JL, Sentelhas PC, Gonçalves JLM, Sparovek G. Köppen’s climate classification map for Brazil. Zeitschrift Meteorologische 2013; 22(6): 711-728.), and the soil belongs to the Vacacaí Mapping Unit (Streck et al., 2008Streck EV, Kämpf N, Dalmolin RSD, Klamt E, Nascimento PC, Schneider P et al. Solos do Rio Grande do Sul. 2 ed. Porto Alegre: Emater-RS/ASCAR; 2008.). The municipality is located in the state’s Central Depression, in the phytoecological zone defined as Ecological Tension Area between Seasonal Deciduous Forest and Steppe. According to the Santa Maria/Rio Grande do Sul Automatic Weather Station, located approximately 60 kilometers from the collection site, the temperature and relative humidity averages were 15.1 °C and 86%, respectively, with an accumulated precipitation of 883 mm during the collection period.

To assess the damage caused to seeds by seed-feeding insects, five plants of S. corymbosa of similar size were randomly chosen, all located at the border of a forest remnant of secondary vegetation, 30 meters apart from each other. One sample per month was performed in May, June, July and August 2014. In each sample, around 50 ripe fruits (per tree) were removed from the middle third of the tree crown, individually packaged in clear bags and taken to laboratory for analysis. In all collections performed, the different stages of fruit maturation in green, yellow, and brown colorations were mixed together, forming the lot / tree.

In the laboratory, fruits were sorted according to two methodologies. The first consisted of packaging the fruits in glass containers sealed with voil to obtain adult insect for subsequent identification of fungi growth in the fruits. For this purpose, 10 ripe fruits from each tree in each collection date were stored in the same container, being monitored for three months. Therefore, 200 fruits of S. corymbosa (5 plants x 10 fruits x 4 months) were stored. After adult emergence, 10 out of the 40 stored fruits from each tree were dissected, totalling 50 dissected fruits throughout the study period. They were selected at random, regardless of whether or not insects had emerged. Prior to the dissection procedure, fruits and seeds were measured for length, thickness, and width with an analog caliper. With the dissection, the total number of seeds per S. corymbosa tree (N) was obtained and the percentage (%) of healthy seeds (hs), seeds damaged by insects (sd), and empty and/or without embryo (se) (aborted seeds) were calculated. This classification of the fruit dissection was analyzed without distinguishing the emerged species of granivorous insect, being considered only with or without damage.

Consumed seed content from the fruits stored in glass containers was obtained by the difference in average weight (grams) between healthy and damaged seeds. For this purpose, 10 repetitions of 100 healthy and damaged seeds were weighed (Barreto et al., 2017Barreto MR, Mojena PA, Pezzini LA, Spies RC. Predação de sementes de Parkia pendula (Willd.) Benth. ex Walp. (Fabaceae) por Acanthoscelides imitator Kingsolver, 1985 (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae: Bruchinae). Boletín de la Sociedad Entomológica Aragonesa 2017;61: 169-174.) in an electronic precision balance (MarK, model 3500). The analysis of variance was performed, followed by the Bonferroni test for averages with the Sisvar software version 5.3 (Ferreira, 2014Ferreira DF. Sisvar: a Guide for its Bootstrap procedures in multiple comparisons. Ciência & Agrotecnologia 2014; 38(2): 109-112.).

The second methodology adopted aimed to quantify the number of insects emerged from 136 fruits. The fruits were accommodated in isolation in clear plastic hoses, 15 cm long and 1.5 cm wide, sealed with cotton at the ends to allow air flow and prevent insects from escaping. Based on the number of insects emerged per fruit, the confidence interval of the mean (IC (µ, 0.95)) was determined, considering three classes: Upper: number of individuals greater than the upper limit of the IC at 5%; Middle: number of individuals located within the IC at 5%; and Lower: number of individuals lower than the inferior limit of the IC at 5%. It was determined with the Student’s t distribution.

Thus, 336 mature fruits were stored throughout the assessment period; 200 fruits stored in glass containers and 136 in plastic hoses. The containers and the hoses were maintained in acclimatized culture room during three months with controlled temperature at 25±1ºC and relative humidity 70±10%. After emerging, adults were accommodated in Eppendorf microtubes with alcohol 70% for subsequent assembly, labelling, and identification.

Insects of the order Coleoptera, family Chrysomelidae, subfamily Bruchinae, were deposited in the Departamento de Zoologia, Universidade Federal do Paraná (Identification n. 79). The Coleoptera of the families Mycetophagidae and Latridiidae were deposited in the Departamento de Zoologia, Universidade Federal do Paraná (Registration number: 0113/2014-RN). Hymenopteran parasitoids were deposited in the Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia (INPA).

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Altogether, 3,548 seed-feeding insects emerged from the 336 ripe fruits of S. corymbosa, being distributed among Sennius lateapicalis (Pic, 1927) (Chrysomelidae) , Acanthoscelides multimaculatusViana & Ribeiro-Costa, 2013Viana JH, Ribeiro-Costa CS. Bruchines (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) associated with Senna neglecta (Vogel) H.S. Irwin and Barneby (Fabaceae: Caesalpinioideae): a new host plant for the subfamily. Journal Natural History 2013; 48(1-2): 57-85. (Chrysomelidae) and Sennius bondari (Pic, 1929) (Chrysomelidae) . In addition, 102 mycophagous beetles belonging to two different species emerged: Lytargus tetraspilotus Le Conte, 1856 (Mycetophagidae) with 84 individuals (82.4%) and Corticaria sp. (Latridiidae) with 18 individuals (17.6%).

In Brazil, 68 species and one subspecies of the genus Acanthoscelides, and 30 species and 2 subspecies of Sennius (Sekerka et al., 2020Sekerka L, Linzmeier AM, Moura LA, Ribeiro-Costa CS, Agrain F, Chamorro ML et al. Chrysomelidae. In: Catálogo Taxonômico da Fauna do Brasil. PNUD. [cited 2020 jan. 30]. Available from: Available from: http://fauna.jbrj.gov.br/fauna/faunadobrasil/115796

.

http://fauna.jbrj.gov.br/fauna/faunadobr...

) were recorded feeding on several species of plants. There are records in the literature that Amblycerus nigromarginatus (Motschulsky, 1874), Amblycerus hoffmanseggi (Gyllenhal, 1833), and Amblycerus submaculatus (Pic, 1927) cause damage to the seeds in S. corymbosa (Ribeiro-Costa et al., 2018Costa EC, Cantarelli EB, Boscardin J, Fleck MD. Insetos-praga de sementes e mudas em viveiros florestais. In: Araujo MM, Navroski MC, Schorn LA, editores. Produção de sementes e mudas: um enfoque à silvicultura. Santa Maria: Editora UFSM; 2018.).

The species Sennius bondari is registered for the following host plants: Senna splendida (Vog.) Irwin and Barneby, S. multijuga (Rich.) Irwin and Barneby, S. occidentalis (L.) Link, Cassia speciosa Schrad., S. surattensis (L. L. Burman) Irwin and Barneby, S. bicapsularis (L.) Roxb., S. pendula (Willd.) var. advena (Vog.) Irwin and Barneby, S. pistaciifolia (H.B.K.) Irwin and Barneby, S. alata (L.) Roxburgh, S. neglecta var. oligophylla, S. neglecta var. neglecta, S. appendiculata (Vogel) Wiersema and S. macranthera (DC. ex Collad.) H.S.Irwin & Barneby (Bondar, 1937Bondar G. Notas biológicas sobre bruquídeos observados no Brasil. Archivos do Instituto de Biologia Vegetal 1937; 3(1): 7-44.; Silva et al., 1968Silva AGDA, Gonçalves CR, Galvão DM, Gonçalves AJL, Gomes J, Silva NM et al. Quarto catálogo dos insetos que vivem nas plantas do Brasil, seus parasitos e predadores. 1° tomo. Insetos, hospedeiros e inimigos naturais. Parte II. Rio de Janeiro: Ministério da Agricultura, Laboratório Central de Patologia Vegetal; 1968.; Johnson, 1984Johnson CD. Sennius yucatan, new species, a redescription of S. infractus, and new host records for other Sennius (Coleoptera: Bruchidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 1984; 77(1): 56-64.; Macêdo et al., 1992Macêdo MV, Lewinsohn T, Kingsolver JM. New host records of some bruchid species in Brazil with the description of a new species of Caryedes (Coleoptera: Bruchidae). The Coleopterists Bulletin 1992; 46(4): 330-336., Ribeiro-Costa, 1998Ribeiro-Costa CS. Observations on the biology of Amblycerus submaculatus (Pic) and Sennius bondari (Pic) (Coleoptera: Bruchidae) in Senna alata (L.) Roxburgh (Caesalpinaceae). The Coleopterists Bulletin 1998; 52(1): 63-69., Ribeiro-Costa & Reynaud, 1998Ribeiro-Costa CS, Reynaud DT. Bruchids from Senna multijuga (Rich) I. & B. (Caesalpinaceae) in Brazil with descriptions of two new species. The Coleopterists Bulletin 1998; 52(3): 245-252., Linzmeier et al., 2004Linzmeier AM, Ribeiro-Costa CS, Caron E. Comportamento e ciclo de vida de Sennius bondari (Pic) (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae, Bruchinae) em Senna macranthera (Collad.) Irwin & Barn. (Caesalpinaceae). Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 2004; 21(2): 351-356., Viana & Ribeiro-Costa, 2013Viana JH, Ribeiro-Costa CS. Bruchines (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) associated with Senna neglecta (Vogel) H.S. Irwin and Barneby (Fabaceae: Caesalpinioideae): a new host plant for the subfamily. Journal Natural History 2013; 48(1-2): 57-85.). This species is distributed in Colombia (Valle del Cauca), Venezuela (Carabobo), Bolivia (Santa Cruz), and Brazil (Bahia, Rio de Janeiro, Minas Gerais, São Paulo, Mato Grosso, Mato Grosso do Sul, Paraná, Rio Grande do Norte, Piauí, Distrito Federal and Espírito Santo) (Viana & Ribeiro-Costa, 2013Viana JH, Ribeiro-Costa CS. Bruchines (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) associated with Senna neglecta (Vogel) H.S. Irwin and Barneby (Fabaceae: Caesalpinioideae): a new host plant for the subfamily. Journal Natural History 2013; 48(1-2): 57-85.). For the species S. lateapicalis, there are records in the host plants S. splendida and S. bicapsularis (Bondar, 1937Bondar G. Notas biológicas sobre bruquídeos observados no Brasil. Archivos do Instituto de Biologia Vegetal 1937; 3(1): 7-44.; Bosq, 1943Bosq JM. Segunda lista de Coleópteros de la República Argentina, dañinos a la Agricultura. Ingeniería Agronómica 1943; 4(18-22): 44-47.; Silva et al., 1968Silva AGDA, Gonçalves CR, Galvão DM, Gonçalves AJL, Gomes J, Silva NM et al. Quarto catálogo dos insetos que vivem nas plantas do Brasil, seus parasitos e predadores. 1° tomo. Insetos, hospedeiros e inimigos naturais. Parte II. Rio de Janeiro: Ministério da Agricultura, Laboratório Central de Patologia Vegetal; 1968.) distributed in Brazil (Rio de Janeiro and Santa Catarina) (Macêdo et al., 1992Macêdo MV, Lewinsohn T, Kingsolver JM. New host records of some bruchid species in Brazil with the description of a new species of Caryedes (Coleoptera: Bruchidae). The Coleopterists Bulletin 1992; 46(4): 330-336.). Acanthoscelides multimaculatus with distribution published for Brazil (Rio de Janeiro, Mato Grosso do Sul and Paraná) has already been registered, causing damage to S. neglecta var. oligophylla, S. neglecta var. neglecta and S. occidentalis (Viana & Ribeiro-Costa, 2013Viana JH, Ribeiro-Costa CS. Bruchines (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) associated with Senna neglecta (Vogel) H.S. Irwin and Barneby (Fabaceae: Caesalpinioideae): a new host plant for the subfamily. Journal Natural History 2013; 48(1-2): 57-85.). This data suggests our study was the first to record these insects associated to S. corymbosa in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

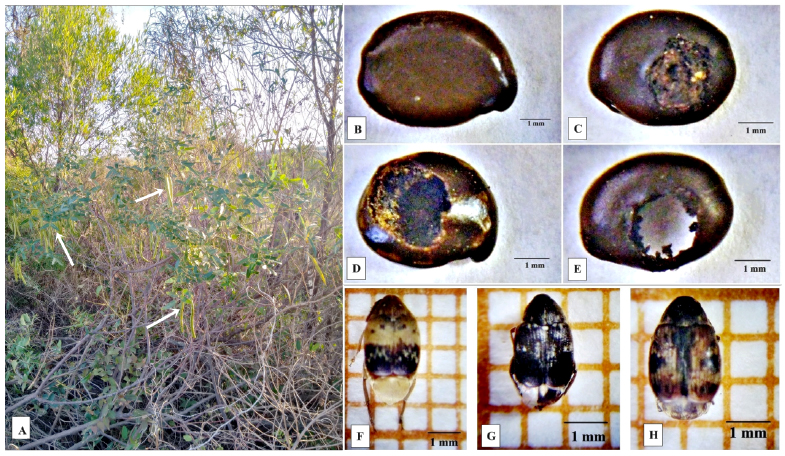

Larvae of seed beetles feed on the cotyledon during their development, and in their last instar before pupating, they compact excrement and food remains to form a pupal chamber (Ribeiro-Costa, 1998Ribeiro-Costa CS. Observations on the biology of Amblycerus submaculatus (Pic) and Sennius bondari (Pic) (Coleoptera: Bruchidae) in Senna alata (L.) Roxburgh (Caesalpinaceae). The Coleopterists Bulletin 1998; 52(1): 63-69.) (Figure 1). This result is similar to the one found by Linzmeier et al. (2004Linzmeier AM, Ribeiro-Costa CS, Caron E. Comportamento e ciclo de vida de Sennius bondari (Pic) (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae, Bruchinae) em Senna macranthera (Collad.) Irwin & Barn. (Caesalpinaceae). Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 2004; 21(2): 351-356.) for S. bondari in seeds of S. macranthera.

(A) Host plant Senna corymbosa. The arrows indicates some fruits. (B) Detail of healthy seed of Senna corymbosa, (C) pupal chamber, (D) seed consumed with adult insect exit hole, (E) and totally consumed seed, (F) dorsal view of Sennius lateapicalis (Pic, 1927), (G) dorsal view of Sennius bondari (Pic, 1929), (H) dorsal view of Acanthoscelides multimaculatusViana & Ribeiro-Costa, 2013Viana JH, Ribeiro-Costa CS. Bruchines (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) associated with Senna neglecta (Vogel) H.S. Irwin and Barneby (Fabaceae: Caesalpinioideae): a new host plant for the subfamily. Journal Natural History 2013; 48(1-2): 57-85..

The flowering phenophase of the host plants provides food for adults, and the fruiting phenophase provides substrate for oviposition and larval development. Thus, adult bruchines consume pollen, while the larvae obtain nutrients for their complete development, consuming the internal seed content (Rossi et al., 2011Rossi MN, Rodrigues LMS, Ishino MN, Kestring D. Oviposition pattern and within-season spatial and temporal variation of pre-dispersal seed predation in a population of Mimosa bimucronata trees. Arthropod-Plant Interactions 2011; 5:209-217.). For the species found in this study, S. bondari consumes the internal content of a single seed (Ribeiro-Costa, 1998Ribeiro-Costa CS. Observations on the biology of Amblycerus submaculatus (Pic) and Sennius bondari (Pic) (Coleoptera: Bruchidae) in Senna alata (L.) Roxburgh (Caesalpinaceae). The Coleopterists Bulletin 1998; 52(1): 63-69.) in seeds of Senna alata (L.) Roxb. and S. macranthera (Linzmeier et al., 2004Linzmeier AM, Ribeiro-Costa CS, Caron E. Comportamento e ciclo de vida de Sennius bondari (Pic) (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae, Bruchinae) em Senna macranthera (Collad.) Irwin & Barn. (Caesalpinaceae). Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 2004; 21(2): 351-356.). However, there are species that need more than one seed to complete their development (Ribeiro-Costa & Almeida, 2012Ribeiro-Costa CS, Almeida LM. Seed-Chewing Beetles (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae, Bruchinae). In: Panizzi AR, Parra JRP, editores. Insect Bioecology and Nutrition for Integrated Pest Management. Brasília: Embrapa Informação Tecnológica; 2012.).

Bruchines emerged from the fruits collected during the four months of evaluation. It is worth mentioning that it was not verified whether the three species of bruchines occur in the same fruit. Moreover, the separation of the damaged fruits by each species of coleoptera suggests that future studies may fill this gap.

The average length of the fruits was of 8.34 cm (minimum 5 - maximum 14,5 cm), with 0.75 cm thickness (minimum 0.5, maximum 1 cm) and 0.72 cm width (minimum 0.5, maximum 0.9 cm). The seeds presented average length, thickness, and width of 0.57, 0.23 and 0.42 cm, respectively. The number of seeds ranged from 21 to 32 per fruit. 10 to 19 seeds per fruit were healthy without the presence of insects, while 1 to 13 were damaged, and 1 to 8 seeds per fruit were empty and/or without its embryo. This variation in the number of damaged seeds per fruit can compromise the reproduction of the host plant, as emphasized by Sousa-Lopes et al. (2019)Sousa-Lopes B, Alves-da-Silva N, Ribeiro-Costa, CS, Del-Claro K. Temporal distribution, seed damage and notes on the natural history of Acanthoscelides quadridentatus and Acanthoscelides winderi (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae: Bruchinae) on their host plant, Mimosa setosa var. paludosa (Fabaceae: Mimosoideae), in the Brazilian Cerrado. Journal of Natural History 2019; 53(9-10): 611-623., who found, for example, that seeds of infested fruits have less resource allocation and, consequently, worse germination rate than healthy seeds of non-infested fruits. After the dissection of 50 fruits, it was found that each fruit had an average of 24.04 seeds (minimum 8, maximum 38), and the average of damaged seeds was 6.6 (minimum 0, maximum 26). Hence, seed beetles can consume around 27% of S. corymbosa seeds.

From the total number of seeds analyzed , 57% were healthy, 27% were damaged by seed beetles, and 16% were empty and/or without embryo (Table 1). The percentage of damaged seeds found in this study was high compared to the result obtained by Sari and Ribeiro-Costa (2005Sari LT, Ribeiro-Costa CS. Predação de sementes de Senna multijuga (Rich.) H. S. Irwin & Barneby (Caesalpinaceae) por bruquíneos (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Neotropical Entomology 2005; 34(3): 521-525.), who found 12.5% of S. multijuga seeds damaged by Sennius crudelis Ribeiro Costa & Reynaud, 1998, Sennius puncticollis (Fåhraeus, 1839) and Sennius nappiRibeiro-Costa & Reynaud, 1998Ribeiro-Costa CS, Reynaud DT. Bruchids from Senna multijuga (Rich) I. & B. (Caesalpinaceae) in Brazil with descriptions of two new species. The Coleopterists Bulletin 1998; 52(3): 245-252.. Nevertheless, the percentage of seeds damaged by bruchines may vary considerably between species, as demonstrated in the study by Rodrigues et al. (2012Rodrigues LMS, Viana JH, Ribeiro-Costa CS, Rossi MN. The extent of seed predation by bruchine beetles (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae: Bruchinae) in a heterogeneous landscape in southeastern Brazil. The Coleopterists Bulletin 2012; 66(3):271-279.), who found a predation rate which varied from 0.62% in Senna hirsuta (L.) H.S.Irwin & Barneby (Fabaceae) by Acanthoscelides sp. to 42.08% in Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) of Wit (Fabaceae) predated by Acanthoscelides macrophthalmus (Schaeffer, 1907). By studying the species L. leucocephala, Raghu et al. (2005Raghu S, Wiltshire C, Dhileepan K. Intensity of pre-dispersal seed predation in the invasive legume Leucaena leucocephala is limited by the duration of pod retention. Austral Ecology 2005; 30: 310-318.) found that the percentage in seeds pre-dispersed by A. macrophthalmus varied from 10.75% to 53.54% of seeds damaged in pods that remained on the tree for one and four months, respectively.

Total number of seeds (ts), healthy seeds (hs), seeds damaged (sd), seeds empty and/or without embryo (se) and the respective percentages per tree of Senna corymbosa in the municipality of São Sepé, RS. ( per tree).

When calculating the percentage of seeds that were empty and/or without embryo, and damaged seeds, the latter with a high probability of not germinating, the value is around 43% of seed loss. When considering that several other factors can occasionally decrease the germinative potential such as pathogens and unfavourable environmental conditions, this percentage may become significant (Sari & Ribeiro-Costa, 2005Sari LT, Ribeiro-Costa CS. Predação de sementes de Senna multijuga (Rich.) H. S. Irwin & Barneby (Caesalpinaceae) por bruquíneos (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Neotropical Entomology 2005; 34(3): 521-525.).

While analyzing the confidence interval for the number of emerged seed beetles, from 136 fruits, up to eight bruchines emerged in 118 fruits, up to sixteen adults emerged in 15 fruits, and more than seventeen bruchines emerged in three fruits (Table 2).

Confidence interval for the number of insects emerged per fruit of Senna corymbosa, in the municipality of São Sepé, RS.

The average weight of 100 seeds differed statistically between healthy and damaged seeds . The average weight of healthy and damaged seeds was 2.59g and 1.47g, respectively. Thus, an average of 1.12g (43.2%) of the internal seed content is consumed by the insects.

Oliveira & Costa (2009Oliveira LS, Costa EC. Predação de sementes de Acacia mearnsii De Wild. (Fabaceae, Mimosoideae). Biotemas 2009; 22(2): 39-44.) found similar results, also with Fabaceae, for seeds of Acacia mearnsii De Wild. damaged by Stator limbatus (Horn, 1873) in which cotyledon consumption was 39.6%. Boscardin et al. (2012Boscardin J, Redin CG, Costa EC, Longhi SJ, Garlet J, Watzlawick LF. Predação de Pseudopachymerina spinipes (Erichon, 1833) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae: Bruchinae) em sementes de Vachellia caven (Molina) Seigles & Ebinger (Fabaceae) no Parque Estadual do Espinilho em Barra do Quaraí, RS. Bioikos 2012; 26(2): 95-100.) found 41.3% of seed mass of Vachellia caven (Molina) Seigler & Ebinger consumed by Pseudopachymerina spinipes (Erichson, 1833).

In addition to seed beetles, Hymenoptera parasitoids emerged, being identified as Bracon sp. (Braconidae) with 40 individuals; Inostemma striaticornu Buhl, 2002 (Platygastridae) with six individuals; and Omeganastatus sp. (Eupelmidae) with 15 individuals.

4. CONCLUSIONS

This was the first occurrence of seed-feeding insects in S. corymbosa recorded in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

The species of seed-feeding insects Sennius lateapicalis, Sennius bondari, and Acanthoscelides multimaculatus (Bruchinae: Chrysomelidae) occur in S. corymbosa consuming up to 43.2% of internal seed content.

Important Hymenoptera parasitoids Bracon sp. (Braconidae), Inostemma striaticornu (Platygastridae), and Omeganastatus sp. (Eupelmidae) were reported.

Further studies on the impact of insect species on germination and seedling quality of S. corymbosa are needed.

REFERENCES

- Alvares CA, Stape JL, Sentelhas PC, Gonçalves JLM, Sparovek G. Köppen’s climate classification map for Brazil. Zeitschrift Meteorologische 2013; 22(6): 711-728.

- Barreto MR, Mojena PA, Pezzini LA, Spies RC. Predação de sementes de Parkia pendula (Willd.) Benth. ex Walp. (Fabaceae) por Acanthoscelides imitator Kingsolver, 1985 (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae: Bruchinae). Boletín de la Sociedad Entomológica Aragonesa 2017;61: 169-174.

- Bondar G. Notas biológicas sobre bruquídeos observados no Brasil. Archivos do Instituto de Biologia Vegetal 1937; 3(1): 7-44.

- Boscardin J, Redin CG, Costa EC, Longhi SJ, Garlet J, Watzlawick LF. Predação de Pseudopachymerina spinipes (Erichon, 1833) (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae: Bruchinae) em sementes de Vachellia caven (Molina) Seigles & Ebinger (Fabaceae) no Parque Estadual do Espinilho em Barra do Quaraí, RS. Bioikos 2012; 26(2): 95-100.

- Bosq JM. Segunda lista de Coleópteros de la República Argentina, dañinos a la Agricultura. Ingeniería Agronómica 1943; 4(18-22): 44-47.

- Costa EC, Cantarelli EB, Boscardin J, Fleck MD. Insetos-praga de sementes e mudas em viveiros florestais. In: Araujo MM, Navroski MC, Schorn LA, editores. Produção de sementes e mudas: um enfoque à silvicultura. Santa Maria: Editora UFSM; 2018.

- Ferreira DF. Sisvar: a Guide for its Bootstrap procedures in multiple comparisons. Ciência & Agrotecnologia 2014; 38(2): 109-112.

- Flora. Digital do Rio Grande do Sul e Santa Catarina. 2020. [cited 2020 may. 04]. Available from: Available from: http://www.ufrgs.br/fitoecologia/florars/open_sp.php?img=8309

» http://www.ufrgs.br/fitoecologia/florars/open_sp.php?img=8309 - Fortunato RH. Senna In: Zuloaga F, Morrone O, editores. Catalogo de las Plantas Vasculares de la Republica Argentina, II (A-E) & (F-Z). Monographies Systematic of the Missouri Botanical Garden 1999; 74.

- Gomes GC, Gomes JCC, Barbieri RL, Miura AK, Sousa LP. Environmental and Ecosystem Services, Tree Diversity and Knowledge of Family Farmers. Floresta e Ambiente 2019; 26: e20160314.

- Irwin HS, Barneby RC. The American Cassinae, a synoptical revision of Leguminosae, Tribe Cassieae, subtribe Cassinae in the New World. Memoires of the New York Botanical Garden 1982; 35: 1-918.

- Johnson CD. Sennius yucatan, new species, a redescription of S. infractus, and new host records for other Sennius (Coleoptera: Bruchidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 1984; 77(1): 56-64.

- Klips RA, Sweeney PM, Bauman EKK, Snow AA. Temporal and geographic variation in predispersal seed predation on Hibiscus moscheutos L. (Malvaceae) in Ohio and Maryland, USA. American Midland Naturalist 2005; 154: 286-295.

- Laporta C. Floral biology and reproductive system of enantiostylous Senna corymbosa (Caesalpiniaceae). Revista de Biología Tropical 2005; 53(1-2): 49-61.

- Lin CM, Li YY. Floral syndrome and breeding system of Senna (Cassia) corymbosa African Journal of Biotechnology 2011; 10(25): 4988-4995.

- Linzmeier AM, Ribeiro-Costa CS, Caron E. Comportamento e ciclo de vida de Sennius bondari (Pic) (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae, Bruchinae) em Senna macranthera (Collad.) Irwin & Barn. (Caesalpinaceae). Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 2004; 21(2): 351-356.

- Macêdo MV, Lewinsohn T, Kingsolver JM. New host records of some bruchid species in Brazil with the description of a new species of Caryedes (Coleoptera: Bruchidae). The Coleopterists Bulletin 1992; 46(4): 330-336.

- Miotto STS, Lüdke R, Oliveira MLAA. A família Leguminosae no Parque Estadual de Itapuã, Viamão, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Biociências 2008; 6(3): 269-290.

- Modena ES, Pires ACV, Barônio GJ, Inforzato I, Demczuk SDB. Do fruit traits of the Senna occidentalis weed influence seed predation by Bruchinae? Revista Brasileira de Biociências 2012; 10(3): 293-297.

- Oliveira LS, Costa EC. Predação de sementes de Acacia mearnsii De Wild. (Fabaceae, Mimosoideae). Biotemas 2009; 22(2): 39-44.

- Raghu S, Wiltshire C, Dhileepan K. Intensity of pre-dispersal seed predation in the invasive legume Leucaena leucocephala is limited by the duration of pod retention. Austral Ecology 2005; 30: 310-318.

- Reflora. Senna corymbosa In: Herbário Virtual. [cited 2020 apr. 30]. Available from: Available from: http://reflora.jbrj.gov.br/reflora/herbarioVirtual

» http://reflora.jbrj.gov.br/reflora/herbarioVirtual - Ribeiro-Costa CS, Almeida LM. Bruchinae (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). In: Panizzi AR, Parra JRP, editores. Bioecologia e nutrição de insetos: base para o manejo integrado de pragas. Brasília: Embrapa Informação Tecnológica; 2009.

- Ribeiro-Costa CS, Almeida LM. Seed-Chewing Beetles (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae, Bruchinae). In: Panizzi AR, Parra JRP, editores. Insect Bioecology and Nutrition for Integrated Pest Management. Brasília: Embrapa Informação Tecnológica; 2012.

- Ribeiro-Costa CS, Manfio D, Morse, GE. Catalog for the Brazilian Amblycerus Thunberg (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae: Bruchinae) with taxonomic notes, host plants associations and distributional records. Zootaxa 2018; 4388(4): 499-525.

- Ribeiro-Costa CS, Reynaud DT. Bruchids from Senna multijuga (Rich) I. & B. (Caesalpinaceae) in Brazil with descriptions of two new species. The Coleopterists Bulletin 1998; 52(3): 245-252.

- Ribeiro-Costa CS. Observations on the biology of Amblycerus submaculatus (Pic) and Sennius bondari (Pic) (Coleoptera: Bruchidae) in Senna alata (L.) Roxburgh (Caesalpinaceae). The Coleopterists Bulletin 1998; 52(1): 63-69.

- Rodrigues LMS, Viana JH, Ribeiro-Costa CS, Rossi MN. The extent of seed predation by bruchine beetles (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae: Bruchinae) in a heterogeneous landscape in southeastern Brazil. The Coleopterists Bulletin 2012; 66(3):271-279.

- Rodrigues RS, Flores AS, Miotto STS, Baptista LRM. O gênero Senna (Leguminosae, Caesalpinioideae) no Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Acta Botanica Brasilica 2005; 19(1): 1-16.

- Rossi MN, Rodrigues LMS, Ishino MN, Kestring D. Oviposition pattern and within-season spatial and temporal variation of pre-dispersal seed predation in a population of Mimosa bimucronata trees. Arthropod-Plant Interactions 2011; 5:209-217.

- Sari LT, Ribeiro-Costa CS, Roper JJ. Dinâmica populacional de bruquíneos (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae) em Senna multijuga (Rich.) H. S. Irwin & Barneby (Caesalpinaceae). Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 2005; 22(1): 169-174.

- Sari LT, Ribeiro-Costa CS. Predação de sementes de Senna multijuga (Rich.) H. S. Irwin & Barneby (Caesalpinaceae) por bruquíneos (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Neotropical Entomology 2005; 34(3): 521-525.

- Sekerka L, Linzmeier AM, Moura LA, Ribeiro-Costa CS, Agrain F, Chamorro ML et al. Chrysomelidae. In: Catálogo Taxonômico da Fauna do Brasil. PNUD. [cited 2020 jan. 30]. Available from: Available from: http://fauna.jbrj.gov.br/fauna/faunadobrasil/115796

» http://fauna.jbrj.gov.br/fauna/faunadobrasil/115796 - Silva AGDA, Gonçalves CR, Galvão DM, Gonçalves AJL, Gomes J, Silva NM et al. Quarto catálogo dos insetos que vivem nas plantas do Brasil, seus parasitos e predadores. 1° tomo. Insetos, hospedeiros e inimigos naturais. Parte II. Rio de Janeiro: Ministério da Agricultura, Laboratório Central de Patologia Vegetal; 1968.

- Simões CMO, Mentz LA, Schenkel EP, Irgang BE, Stehmann JR. Plantas da Medicina Popular no Rio Grande do Sul. 4 ed. Porto Alegre: Editora da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul; 1995.

- Sousa-Lopes B, Alves-da-Silva N, Ribeiro-Costa, CS, Del-Claro K. Temporal distribution, seed damage and notes on the natural history of Acanthoscelides quadridentatus and Acanthoscelides winderi (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae: Bruchinae) on their host plant, Mimosa setosa var. paludosa (Fabaceae: Mimosoideae), in the Brazilian Cerrado. Journal of Natural History 2019; 53(9-10): 611-623.

- Streck EV, Kämpf N, Dalmolin RSD, Klamt E, Nascimento PC, Schneider P et al. Solos do Rio Grande do Sul. 2 ed. Porto Alegre: Emater-RS/ASCAR; 2008.

- Viana JH, Ribeiro-Costa CS. Bruchines (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) associated with Senna neglecta (Vogel) H.S. Irwin and Barneby (Fabaceae: Caesalpinioideae): a new host plant for the subfamily. Journal Natural History 2013; 48(1-2): 57-85.

- Viana JH, Ribeiro-Costa CS. Two new Brazilian Sennius species near the guttifer group (Coleoptera:Chrysomelidae:Bruchinae). The Florida Entomologist 2014; 97(3): 1108-1114.

- Wolowski M, Freitas L. Reproduction, pollination and seed predation of Senna multijuga (Fabaceae) in two protected areas in the Brazilian Atlantic forest. Revista de Biología Tropical 2011; 59(4): 1939-1948.

Edited by

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

07 Aug 2020 -

Date of issue

2021

History

-

Received

03 Feb 2020 -

Accepted

10 July 2020