Abstracts

INTRODUCTION:

Physical exercise has been associated with improvement of quality of live (QoL), but its effect among the elderly with depression and Alzheimer's disease (AD) is still unclear. This systematic review evaluated randomized and controlled studies about the effect of physical exercise on QoL of older individuals with a clinical diagnosis of depression and AD.

METHODS:

We searched PubMed, ISI, SciELO and Scopus from December 2011 to June 2013 using the following keywords: physical exercise, quality of life, elderly, depression, Alzheimer's disease. Only six studies met inclusion criteria: two examined patients with AD and four, patients with depression.

RESULTS:

The studies used different methods to prescribe exercise and evaluate QoL, but all had high quality methods. Findings of most studies with individuals with depression suggested that exercise training improved QoL, but studies with patients with AD had divergent results.

CONCLUSIONS:

Although different methods were used, results suggested that physical exercise is an effective non-pharmacological intervention to improve the QoL of elderly individuals with depression and AD. Future studies should investigate the effect of other factors, such as the use of specific scales for the elderly, controlled exercise prescriptions and type of control groups.

Quality of life; elderly; depression; Alzheimer's disease

INTRODUÇÃO:

O exercício físico parece estar relacionado à melhora na qualidade de vida (QdV), mas seus efeitos em populações de indivíduos idosos com depressão ou Doença de Alzheimer (DA) ainda não foram estabelecidos. Esta revisão sistemática avaliou estudos controlados randomizados sobre os efeitos do exercício físico sobre a QdV em idosos com diagnóstico clínico de depressão e DA.

MÉTODOS:

Foi feita uma busca nas bases de dados PubMed, ISI, SciELO e Scopus de dezembro de 2011 a junho de 2013 usando os seguintes descritores: exercício físico, qualidade de vida, idosos, depressão, doença de Alzheimer. Apenas seis estudos satisfizeram os critérios de inclusão: Dois com pacientes com DA e quatro com pacientes com depressão.

RESULTADOS:

Os estudos adotaram metodologias diferentes de prescrição de exercícios e avaliação de QdV, mas todos preencheram os requisitos de alta qualidade metodológica. Os resultados da maioria dos estudos com idosos com depressão sugerem que a QdV melhora com o treinamento físico, mas os estudos com pacientes com DA tiveram resultados divergentes.

CONCLUSÕES:

Apesar de os estudos usarem metodologias diferentes, seus resultados sugerem que os exercícios físicos são uma intervenção não-farmacológica efetiva para melhorar a QdV entre idosos com depressão e DA. Estudos futuros devem investigar os efeitos de outros fatores, tais como o uso de questionários específicos para idosos, a prescrição controlada de exercícios, e o tipo de grupo controle.

qualidade de vida; idosos; depressão; doença de Alzheimer

Introduction

Epidemiological data have shown a significant increase of the aging population around the world, especially in developing countries.11. Kinsella K, He W. An aging world: 2008. International Population Reports. Washington: US Census Bureau; 2009. http://www.census.gov/prod/2009pubs/p95-09-1.pdf .

http://www.census.gov/prod/2009pubs/p95-...

It is expected that within the next fifty years there will be 58 million older individuals, accounting for 23.6% of the total population.22. Scazufca M, Cerqueira AT, Menezes PR, Prince M, Vallada HP, Miyazaki MC, et al. [Epidemiological research on dementia in developing countries]. Rev Saude Publica. 2002;36:773-8. According to the Brazilian Public Health System, public spending with hospitalizations of older individuals was US$ 659 million in 1996.33. Chaimowicz F. A saúde dos idosos brasileiros às vésperas do século XXI: problemas, projeções e alternativas. Rev Saude Publica. 1997;31:184-200. Chronic diseases associated with aging, such as depression and Alzheimer's disease (AD), have already become a growing demand in public health services.44. Fleck M, Chachamovich E, Trentini C. Development and validation of the Portuguese version if the WHOQOL-OLD module. Rev Saude Publica. 2006;40:785-91. However, epidemiological studies about dementia and depression in elderly populations should take into consideration the limits between depression and depressive symptoms, as well as the cognitive decline of healthy aging.55. Coutinho ESF, Laks J. Saúde mental do idoso no Brasil: a relevância da pesquisa epidemiológica. Cad Saude Publica. 2012;28:412-3.

A common feature of depression and AD is low quality of life (QoL).44. Fleck M, Chachamovich E, Trentini C. Development and validation of the Portuguese version if the WHOQOL-OLD module. Rev Saude Publica. 2006;40:785-91. , 66. Blay SL, Andreoli SB, Fillenbaum GG, Gastal FL. Depression morbidity in later life: prevalence and correlates in a developing country. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:790-9. Epub 2007 Aug 13. According to the World Health Organization, QoL is defined as an individual's perception of their position in life, in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live, and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns.77. Bowling A. Measuring disease. A review of disease-specific quality of life measurement scales. 2nd ed. Buckingham: Open University; 2001 QoL evaluation is extremely important for public health, and some economic indexes have been developed for that purpose. Among them, the quality-adjusted life years (QALY) index estimates quality years earned, whereas the disability-adjusted life years (DALY) index calculates years lost due to disability.88. Campolina AG, Bortoluzzo AB, Ferraz MB, Ciconelli RM. O questionário sf-6D Brasil: modelos de construção e aplicações em economia da saúde. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2010;56:409-14. , 99. Apeldoorn AT, Ostelo RW, van Helvoirt H, Fritz JM, de Vet HC, van Tulder MW. The cost-effectiveness of a treatment-based classification system for low back pain: design of a randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:58. QoL, a ubiquitous concept, is associated with social, psychological, and functional factors. Therefore, an increased prevalence of depression and AD among the elderly may lead to lower QoL. Especially in AD, cognitive and motor changes may increase dependency on others for the performance of activities of daily living, which may limit QoL.1010. Santana-Sosa E, Barriopedro MI, López-Mojares LM, Pérez M, Lucia A. Exercise training is beneficial for Alzheimer's patients. Int J Sports Med. 2008;29:845-50. Epub 2008 Apr 9. , 1111. Zhu CW, Sano M. Economic considerations in the management of Alzheimer's disease. Clin Interv Aging. 2006;1:143-54. Moreover, impaired awareness of disease may affect the subjective evaluation of QoL.1212. Sousa MF, Santos RL, Arcoverde C, Dourado M, Laks J. Consciência da doença na doença de Alzheimer: resultados preliminares de um estudo longitudinal. Rev Psiquiatr Clin. 2011;38:57-60.However, the association of QoL with depression and AD remains unclear.1313. Lima AF, Fleck M. Qualidade de vida e depressão: uma revisão de literatura. Rev Psiquiatr Rio Gd Sul. 2009;31:1-12.

Some studies have pointed out that physical exercise is a low-cost intervention to improve QoL among older populations.1414. Gusi N, Reyes MC, Gonzalez-Guerrero JL, Herrera E, Garcia JM. Cost-utility of a walking programme for moderately depressed, obese, or overweight elderly women in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:231.

15. Eyigor S, Karapolat H, Durmaz B. Effects of a group-based exercise program on the physical performance, muscle strength and quality of life in older women. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2007;45:259-71. Epub 2007 Feb 15. - 1616. Deslandes AC, Moraes H, Alves H, Pompeu FA, Silveira H, Mouta R, et al. Effect of aerobic training on EEG alpha asymmetry and depressive symptoms in the elderly: a 1-year follow-up study. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2010;43:585-92. Epub 2010 May 14. In addition to cardiovascular and musculoskeletal benefits, exercise promotes an increase in cognitive performance, self-effectiveness and motor control, which leads to improved functional capacity and QoL.1414. Gusi N, Reyes MC, Gonzalez-Guerrero JL, Herrera E, Garcia JM. Cost-utility of a walking programme for moderately depressed, obese, or overweight elderly women in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:231. , 1616. Deslandes AC, Moraes H, Alves H, Pompeu FA, Silveira H, Mouta R, et al. Effect of aerobic training on EEG alpha asymmetry and depressive symptoms in the elderly: a 1-year follow-up study. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2010;43:585-92. Epub 2010 May 14. , 1717. Spirduso WW, Cronin DL. Exercise dose-response effects on quality of life and independent living in older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(6 Suppl):S598-608. However, current evidence applies to healthy individuals1818. Kerse N, Peri K, Robinson E, Wilkinson T, von Randow M, Kiata L, et al. Does a functional activity programme improve function, quality of life, and falls for residents in long term care? Cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a1445. , 1919. Vaapio S, Salminen M, Vahlberg T, Sjösten N, Isoaho R, Aarnio P, et al. Effects of risk-based multifactorial fall prevention on health-related quality of life among the community-dwelling aged: a randomized controlled trial. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:20. and individuals with depressive symptoms.1515. Eyigor S, Karapolat H, Durmaz B. Effects of a group-based exercise program on the physical performance, muscle strength and quality of life in older women. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2007;45:259-71. Epub 2007 Feb 15. , 2020. Antunes HK, Stella SG, Santos RF, Bueno OF, de Mello MT. Depression, anxiety and quality of life scores in seniors after an endurance exercise program. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2005;27:266-71. Epub 2005 Dec 12. Few studies have included older individuals with a clinical diagnosis of major depression and AD.2121. Lavretsky H, Alstein LL, Olmstead RE, Ercoli LM, Riparetti-Brown M, Cyr NS, et al. Complementary use of tai chi chih augments escitalopram treatment of geriatric depression: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19:839-50.

22. Kerse N, Hayman KJ, Moyes SA, Peri K, Robinson E, Dowell A, et al. Home-based activity program for older people with depressive symptoms: DeLLITE--a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:214-23.

23. Singh NA, Clements KM, Fiatarone MA. A randomized controlled trial of progressive resistance training in depressed elders. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1997;52:M27-35.

24. Singh NA, Stavrinos TM, Scarbek Y, Galambos G, Liber C, Fiatarone Singh MA. A randomized controlled trial of high versus low intensity weight training versus general practitioner care for clinical depression in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:768-76.

25. Steinberg M, Leoutsakos JM, Podewils LJ, Lyketsos CG. Evaluation of a home-based exercise program in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease: the Maximizing Independence in Dementia (MIND) study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:680-5. - 2626. Teri L, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Buchner DM, Barlow WE, et al. Exercise plus behavioral management in patients with Alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:2015-22. Although data about this association are scarce, previous reviews concluded that the differences in exercise type and QoL evaluations might have affected comparisons between studies.2727. Schuch FB, Vasconcelos-Moreno MP, Fleck MP. The impact of exercise on quality of life within exercise and depression trials: a systematic review. Mental Health Phys Act. 2011;4:43-8. , 2828. Potter R, Ellard D, Rees K, Thorogood M. A systematic review of the effects of physical activity on physical functioning, quality of life and depression in older people with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:1000-11. Epub 2011 Jan 6. Moreover, some of those reviews included adults in general and analyzed other variables, in addition to QoL.

The effect of physical exercise on QoL should be assessed in groups of older patients with depression and AD. This study reviewed randomized controlled trials that included patients with a clinical diagnosis of depression or AD and analyzed type of exercise and QoL measurement.

Methods

This systematic review, conducted from December 2011 to June 2013, followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.

Criteria for eligibility

We reviewed randomized controlled trials that investigated the effect of exercise on QoL using different exercise types and intensities, written in English or Portuguese. Studies were included only if they used specific scales to assess QoL and included individuals older than 60 years who had a clinical diagnosis of depression or AD.

Information sources

We searched PubMed, ISI, SciELO and Scopus using the following keywords: (physical exercise) AND (elderly) AND (quality of life) AND (depression) AND (Alzheimer disease). Additionally, the references of published studies were reviewed. Full-text versions of all potentially relevant articles were downloaded from the electronic databases or requested directly from the authors.

Search

The following criteria and limits were used to search PubMed for studies about the effect of exercise on QOL in elderly patients with depression: (("exercise"[MeSH Terms] OR "exercise"[All Fields]) OR ("physical"[All Fields] AND "exercise"[All Fields] OR "physical exercise"[All Fields]) AND ("quality of life"[MeSH Terms]) OR ("quality"[All Fields] AND "life"[All Fields]) OR ("quality of life"[All Fields]) AND ("aged"[MeSH Terms] OR "aged"[All Fields] OR "elderly"[All Fields]) AND ("depressive disorder"[MeSH Terms]) OR ("depressive"[All Fields] AND "disorder"[All Fields]) OR "depressive disorder"[All Fields] OR "depression"[All Fields] OR "depression"[MeSH Terms])) AND ("humans"[MeSH Terms] AND Randomized Controlled Trial[ptyp] AND English[lang] AND "aged"[MeSH Terms]). The same criteria and limits were used for studies that included patients with AD, but the terms used were: ("alzheimer" [All Fields] AND "disease" [All Fields]) OR "alzheimer disease" [All Fields])). In ISI, SciELO and Scopus, depression and Alzheimer's disease were included in specific searches with the following keywords: physical exercise AND quality of life AND elderly.

Data collection

After a first double screening of titles and abstracts, the studies were selected for full-text reading by two reviewers. In case of disagreement between them, the results were discussed with a third reviewer.

Selection of studies

We excluded studies that used physical exercise together with other interventions, as well as studies that did not include any clinical diagnosis. We also used the PEDro scale,2929. Shiwa SR, Costa LO, Moser AD, Aguiar IC, Oliveira LV. PEDro: a base de dados de evidências em fisioterapia. Fisioter Mov. 2011;24:523-33. an 11-criterion scale that assess methods and statistical quality of randomized controlled trial according to scores that range from zero to 10.

Risk of bias

Bias measurement was based on the type of exercise (supervised and non-supervised) and control group (with or without social contact), because these two factors may affect depressive symptoms, mood, and QoL. Moreover, randomization and blinding were evaluated in all studies.

Results

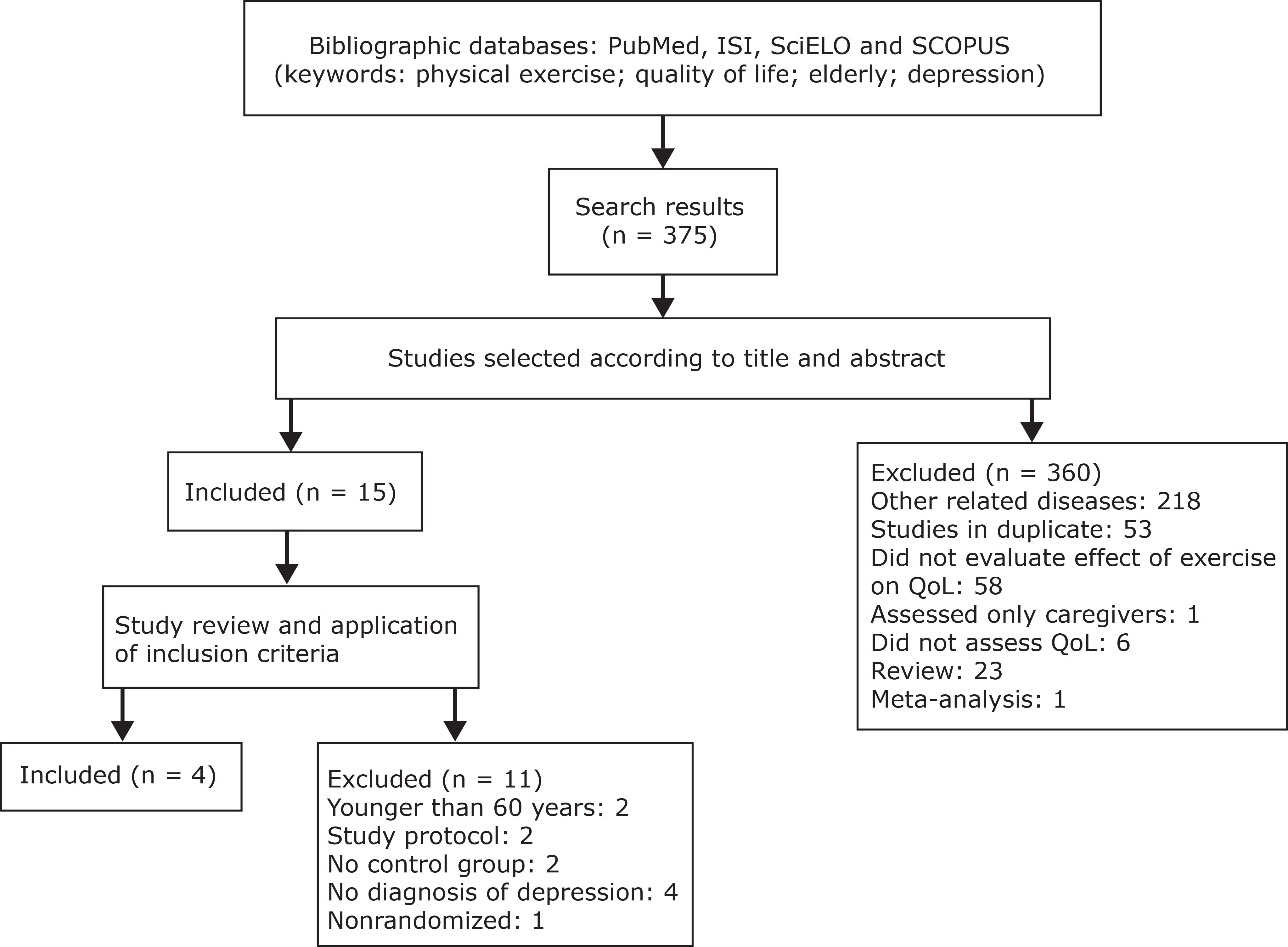

Our literature search yielded 375 studies about elderly patients with depression and 47 about patients with AD. One more study was found in the references and added to this review. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the steps taken to select the studies.

Flowchart of search and selection of studies that included older individuals with depression.

Flowchart illustrating search and selection of studies that included older individuals with Alzheimer's disease.

Two studies with individuals with AD, selected according to the inclusion criteria, had contradictory results of QoL scales. In one of them, there was a significant improvement of QoL measured using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36(r)),2626. Teri L, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Buchner DM, Barlow WE, et al. Exercise plus behavioral management in patients with Alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:2015-22. a multidimensional questionnaire that covers eight domains: physical functioning, role physical, mental health, role-emotional, social functioning, vitality, pain and general health.3030. Ciconelli RM, Ferraz MB, Santos WS, Meinão I, Quaresma MR. Tradução para a língua portuguesa e validação do questionário genérico de avaliação de qualidade de vida SF-36 (Brasil SF-36). Rev Bras Reumatol. 1999;39:143-50. However, only results in the physical functioning item were significant. In contrast, Steinberg et al.2525. Steinberg M, Leoutsakos JM, Podewils LJ, Lyketsos CG. Evaluation of a home-based exercise program in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease: the Maximizing Independence in Dementia (MIND) study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:680-5. found a non-significant improvement of QoL measured using the Alzheimer's Disease-Related Quality of Life (ADQRL) scale. The control group in one study was a home-safety assessment group2525. Steinberg M, Leoutsakos JM, Podewils LJ, Lyketsos CG. Evaluation of a home-based exercise program in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease: the Maximizing Independence in Dementia (MIND) study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:680-5. and in the other, a group of patients that received routine medical care and no intervention.2626. Teri L, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Buchner DM, Barlow WE, et al. Exercise plus behavioral management in patients with Alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:2015-22.

The evaluation of depression, also using the SF-36(r), revealed that all studies had significant results. There was significant improvement in all domains, except in general health.2121. Lavretsky H, Alstein LL, Olmstead RE, Ercoli LM, Riparetti-Brown M, Cyr NS, et al. Complementary use of tai chi chih augments escitalopram treatment of geriatric depression: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19:839-50.

22. Kerse N, Hayman KJ, Moyes SA, Peri K, Robinson E, Dowell A, et al. Home-based activity program for older people with depressive symptoms: DeLLITE--a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:214-23.

23. Singh NA, Clements KM, Fiatarone MA. A randomized controlled trial of progressive resistance training in depressed elders. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1997;52:M27-35. - 2424. Singh NA, Stavrinos TM, Scarbek Y, Galambos G, Liber C, Fiatarone Singh MA. A randomized controlled trial of high versus low intensity weight training versus general practitioner care for clinical depression in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:768-76. Exercises were different, especially in type, intensity, and duration of the intervention. Control groups were also different: three studies used social contact and health education2121. Lavretsky H, Alstein LL, Olmstead RE, Ercoli LM, Riparetti-Brown M, Cyr NS, et al. Complementary use of tai chi chih augments escitalopram treatment of geriatric depression: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19:839-50.

22. Kerse N, Hayman KJ, Moyes SA, Peri K, Robinson E, Dowell A, et al. Home-based activity program for older people with depressive symptoms: DeLLITE--a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:214-23. - 2323. Singh NA, Clements KM, Fiatarone MA. A randomized controlled trial of progressive resistance training in depressed elders. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1997;52:M27-35. and one, no intervention.2424. Singh NA, Stavrinos TM, Scarbek Y, Galambos G, Liber C, Fiatarone Singh MA. A randomized controlled trial of high versus low intensity weight training versus general practitioner care for clinical depression in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:768-76.

Only two studies were blinded to group allocations and follow-up evaluations.1818. Kerse N, Peri K, Robinson E, Wilkinson T, von Randow M, Kiata L, et al. Does a functional activity programme improve function, quality of life, and falls for residents in long term care? Cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a1445. , 2424. Singh NA, Stavrinos TM, Scarbek Y, Galambos G, Liber C, Fiatarone Singh MA. A randomized controlled trial of high versus low intensity weight training versus general practitioner care for clinical depression in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:768-76. The assessment of study quality using the PEDro scale showed that all six selected studies had scores greater than or equal to six and were classified as high-quality studies. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics and results of these studies.

Discussion

This study reviewed studies that investigated the effect of physical exercise on QoL in older individuals with depression or AD. Although some studies found significant improvement of QoL, findings were different for specific aspects of QoL and type of exercise.

Studies have used different exercise types, such as strength training,2323. Singh NA, Clements KM, Fiatarone MA. A randomized controlled trial of progressive resistance training in depressed elders. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1997;52:M27-35. , 2424. Singh NA, Stavrinos TM, Scarbek Y, Galambos G, Liber C, Fiatarone Singh MA. A randomized controlled trial of high versus low intensity weight training versus general practitioner care for clinical depression in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:768-76. tai chi chih,2121. Lavretsky H, Alstein LL, Olmstead RE, Ercoli LM, Riparetti-Brown M, Cyr NS, et al. Complementary use of tai chi chih augments escitalopram treatment of geriatric depression: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19:839-50. and combined exercise (strength, aerobic, balance, and flexibility).2222. Kerse N, Hayman KJ, Moyes SA, Peri K, Robinson E, Dowell A, et al. Home-based activity program for older people with depressive symptoms: DeLLITE--a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:214-23. , 2525. Steinberg M, Leoutsakos JM, Podewils LJ, Lyketsos CG. Evaluation of a home-based exercise program in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease: the Maximizing Independence in Dementia (MIND) study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:680-5. , 2626. Teri L, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Buchner DM, Barlow WE, et al. Exercise plus behavioral management in patients with Alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:2015-22. Results on QoL were positive, especially in studies that included elderly individuals with depression. However, these studies used different exercise types and intensities, and it is, therefore, unclear what effect these variables have on QoL. The practice of tai chi chih resulted in physical improvement only, whereas strength training alone and together with other exercises promoted significant improvement in some physical and mental aspects assessed using the SF-36(r).2222. Kerse N, Hayman KJ, Moyes SA, Peri K, Robinson E, Dowell A, et al. Home-based activity program for older people with depressive symptoms: DeLLITE--a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:214-23.

23. Singh NA, Clements KM, Fiatarone MA. A randomized controlled trial of progressive resistance training in depressed elders. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1997;52:M27-35. - 2424. Singh NA, Stavrinos TM, Scarbek Y, Galambos G, Liber C, Fiatarone Singh MA. A randomized controlled trial of high versus low intensity weight training versus general practitioner care for clinical depression in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:768-76. According to Singh et al.,2323. Singh NA, Clements KM, Fiatarone MA. A randomized controlled trial of progressive resistance training in depressed elders. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1997;52:M27-35. , 2424. Singh NA, Stavrinos TM, Scarbek Y, Galambos G, Liber C, Fiatarone Singh MA. A randomized controlled trial of high versus low intensity weight training versus general practitioner care for clinical depression in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:768-76. high intensity exercises may improve QoL. Different exercise types and intensity, together with psychological and physical symptoms of depression, may also affect the perception of QoL, because these evaluations are subjective.3131. Stella F, Gobbi S, Corazza DI, Costa JL. Depressão no idoso: diagnóstico, tratamento e benefícios da atividade física. Motriz. 2002;8:91-8.

Only two studies about AD met the inclusion criteria for this review. In one of them, there was significant improvement of the physical aspect measured using the SF-36(r).2626. Teri L, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Buchner DM, Barlow WE, et al. Exercise plus behavioral management in patients with Alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:2015-22. However, the type of exercise was not described, and the scale used was not specifically designed for individuals with AD. In contrast, the results of another study using a QoL scale specific for individuals with AD, the Alzheimer's Disease-Related Quality of Life (ADQRL) scale, were not significant.2525. Steinberg M, Leoutsakos JM, Podewils LJ, Lyketsos CG. Evaluation of a home-based exercise program in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease: the Maximizing Independence in Dementia (MIND) study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:680-5. Some factors were identified as biases, such as the difference in QoL scores between groups at baseline and higher scores in the depression scale after the intervention. Despite the association between depression and AD, mean depression score was not above the cut-off point. Moreover, although these studies investigated the same type of exercise, they used different QoL scales, which may affect their comparison.

The most frequent scale in the studies included in this review was the SF-36(r), a frequently used instrument validated for the general population.3030. Ciconelli RM, Ferraz MB, Santos WS, Meinão I, Quaresma MR. Tradução para a língua portuguesa e validação do questionário genérico de avaliação de qualidade de vida SF-36 (Brasil SF-36). Rev Bras Reumatol. 1999;39:143-50. However, QoL concepts may be different for young people, adults, and the elderly. The elderly usually rate their QoL according to material and social factors and their independence in activities of daily living,3232. Netuveli G, Blane D. Quality of life in older ages. Br Med Bull. 2008;85:113-26. Epub 2008 Feb 15. whereas younger individuals assign greater importance to work than to health.3333. Fleck MP, Chachamovich E, Trentini CM. [WHOQOL-OLD Project: method and focus group results in Brazil]. Rev Saude Publica. 2003;37:793-9. Epub 2003 Nov 27.Therefore, to improve result reliability, future studies should use scales specifically designed for older populations.

Some experimental procedures of the studies included in this review should also be discussed. Lavretsky et al.2121. Lavretsky H, Alstein LL, Olmstead RE, Ercoli LM, Riparetti-Brown M, Cyr NS, et al. Complementary use of tai chi chih augments escitalopram treatment of geriatric depression: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19:839-50. investigated the role of physical exercises associated with meditation practices and compared results with those of a control group of individuals who participated in a health education program. Both the lack of a control group that received no interventions and the small size of the sample may have been limitations of this study. In another intervention study, Kerse et al.2222. Kerse N, Hayman KJ, Moyes SA, Peri K, Robinson E, Dowell A, et al. Home-based activity program for older people with depressive symptoms: DeLLITE--a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:214-23. used a variety of non-supervised exercises and did not describe the method used to prescribe exercises. Therefore, it is not clear whether the type of control condition and the intensity of exercises might have played a role in the effect of exercise on QoL among elderly individuals with depression.

Although all studies included in this review were classified as high quality according to the evaluation of their methods, they had differences in their definition of clinical diagnoses of depression and type of exercises. One study included only individuals with major depression,2121. Lavretsky H, Alstein LL, Olmstead RE, Ercoli LM, Riparetti-Brown M, Cyr NS, et al. Complementary use of tai chi chih augments escitalopram treatment of geriatric depression: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19:839-50. but most investigated other types of depression, such as dysthymia and minor depression.2222. Kerse N, Hayman KJ, Moyes SA, Peri K, Robinson E, Dowell A, et al. Home-based activity program for older people with depressive symptoms: DeLLITE--a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:214-23.

23. Singh NA, Clements KM, Fiatarone MA. A randomized controlled trial of progressive resistance training in depressed elders. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1997;52:M27-35. - 2424. Singh NA, Stavrinos TM, Scarbek Y, Galambos G, Liber C, Fiatarone Singh MA. A randomized controlled trial of high versus low intensity weight training versus general practitioner care for clinical depression in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:768-76. Moreover, the use of drugs and the small size of the samples complicated the comparison of findings. Cognitive and functional aspects of AD associated with the subjective evaluations of patients and caregivers may also affect QoL measures.3434. Rabins PV, Kasper JD, Kleinman L, Black B, Patrick DL. Concepts and methods in the development of the ADRQL: an instrument for assessing health-related quality of life in persons with Alzheimer's disease. J Ment Health Aging. 1999;5:33-48. The assessment of risk of bias revealed that different types of control groups, as well as the lack of blinding for allocations and follow-up evaluations, were important limitations of most studies. Future studies should include specific exercise prescriptions and QoL scales that assess cost-effectiveness, such as QALY and DALY.

Conclusions

Few studies met the inclusion criteria of this review, and no conclusion could be drawn about intensity and type of exercises to improve QoL of older individuals with depression. However, different types of exercise resulted in significant improvement of QoL among older individuals with depression, which suggests that physical exercise may be used as an additional non-pharmacological intervention in those cases. In addition, QoL assessments may be viewed as an outcome for physical exercise interventions in elderly individuals with depression or AD.

Acknowledgements

Helena Moraes (E-26/100.274/2013), Andrea Deslandes (E-26/102.174/2013), and Jerson Laks (E-26/112.631/2012) have received grants from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

References

-

1Kinsella K, He W. An aging world: 2008. International Population Reports. Washington: US Census Bureau; 2009. http://www.census.gov/prod/2009pubs/p95-09-1.pdf .

» http://www.census.gov/prod/2009pubs/p95-09-1.pdf -

2Scazufca M, Cerqueira AT, Menezes PR, Prince M, Vallada HP, Miyazaki MC, et al. [Epidemiological research on dementia in developing countries]. Rev Saude Publica. 2002;36:773-8.

-

3Chaimowicz F. A saúde dos idosos brasileiros às vésperas do século XXI: problemas, projeções e alternativas. Rev Saude Publica. 1997;31:184-200.

-

4Fleck M, Chachamovich E, Trentini C. Development and validation of the Portuguese version if the WHOQOL-OLD module. Rev Saude Publica. 2006;40:785-91.

-

5Coutinho ESF, Laks J. Saúde mental do idoso no Brasil: a relevância da pesquisa epidemiológica. Cad Saude Publica. 2012;28:412-3.

-

6Blay SL, Andreoli SB, Fillenbaum GG, Gastal FL. Depression morbidity in later life: prevalence and correlates in a developing country. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:790-9. Epub 2007 Aug 13.

-

7Bowling A. Measuring disease. A review of disease-specific quality of life measurement scales. 2nd ed. Buckingham: Open University; 2001

-

8Campolina AG, Bortoluzzo AB, Ferraz MB, Ciconelli RM. O questionário sf-6D Brasil: modelos de construção e aplicações em economia da saúde. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2010;56:409-14.

-

9Apeldoorn AT, Ostelo RW, van Helvoirt H, Fritz JM, de Vet HC, van Tulder MW. The cost-effectiveness of a treatment-based classification system for low back pain: design of a randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:58.

-

10Santana-Sosa E, Barriopedro MI, López-Mojares LM, Pérez M, Lucia A. Exercise training is beneficial for Alzheimer's patients. Int J Sports Med. 2008;29:845-50. Epub 2008 Apr 9.

-

11Zhu CW, Sano M. Economic considerations in the management of Alzheimer's disease. Clin Interv Aging. 2006;1:143-54.

-

12Sousa MF, Santos RL, Arcoverde C, Dourado M, Laks J. Consciência da doença na doença de Alzheimer: resultados preliminares de um estudo longitudinal. Rev Psiquiatr Clin. 2011;38:57-60.

-

13Lima AF, Fleck M. Qualidade de vida e depressão: uma revisão de literatura. Rev Psiquiatr Rio Gd Sul. 2009;31:1-12.

-

14Gusi N, Reyes MC, Gonzalez-Guerrero JL, Herrera E, Garcia JM. Cost-utility of a walking programme for moderately depressed, obese, or overweight elderly women in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:231.

-

15Eyigor S, Karapolat H, Durmaz B. Effects of a group-based exercise program on the physical performance, muscle strength and quality of life in older women. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2007;45:259-71. Epub 2007 Feb 15.

-

16Deslandes AC, Moraes H, Alves H, Pompeu FA, Silveira H, Mouta R, et al. Effect of aerobic training on EEG alpha asymmetry and depressive symptoms in the elderly: a 1-year follow-up study. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2010;43:585-92. Epub 2010 May 14.

-

17Spirduso WW, Cronin DL. Exercise dose-response effects on quality of life and independent living in older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(6 Suppl):S598-608.

-

18Kerse N, Peri K, Robinson E, Wilkinson T, von Randow M, Kiata L, et al. Does a functional activity programme improve function, quality of life, and falls for residents in long term care? Cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a1445.

-

19Vaapio S, Salminen M, Vahlberg T, Sjösten N, Isoaho R, Aarnio P, et al. Effects of risk-based multifactorial fall prevention on health-related quality of life among the community-dwelling aged: a randomized controlled trial. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:20.

-

20Antunes HK, Stella SG, Santos RF, Bueno OF, de Mello MT. Depression, anxiety and quality of life scores in seniors after an endurance exercise program. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2005;27:266-71. Epub 2005 Dec 12.

-

21Lavretsky H, Alstein LL, Olmstead RE, Ercoli LM, Riparetti-Brown M, Cyr NS, et al. Complementary use of tai chi chih augments escitalopram treatment of geriatric depression: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19:839-50.

-

22Kerse N, Hayman KJ, Moyes SA, Peri K, Robinson E, Dowell A, et al. Home-based activity program for older people with depressive symptoms: DeLLITE--a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:214-23.

-

23Singh NA, Clements KM, Fiatarone MA. A randomized controlled trial of progressive resistance training in depressed elders. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1997;52:M27-35.

-

24Singh NA, Stavrinos TM, Scarbek Y, Galambos G, Liber C, Fiatarone Singh MA. A randomized controlled trial of high versus low intensity weight training versus general practitioner care for clinical depression in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:768-76.

-

25Steinberg M, Leoutsakos JM, Podewils LJ, Lyketsos CG. Evaluation of a home-based exercise program in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease: the Maximizing Independence in Dementia (MIND) study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:680-5.

-

26Teri L, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Buchner DM, Barlow WE, et al. Exercise plus behavioral management in patients with Alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:2015-22.

-

27Schuch FB, Vasconcelos-Moreno MP, Fleck MP. The impact of exercise on quality of life within exercise and depression trials: a systematic review. Mental Health Phys Act. 2011;4:43-8.

-

28Potter R, Ellard D, Rees K, Thorogood M. A systematic review of the effects of physical activity on physical functioning, quality of life and depression in older people with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:1000-11. Epub 2011 Jan 6.

-

29Shiwa SR, Costa LO, Moser AD, Aguiar IC, Oliveira LV. PEDro: a base de dados de evidências em fisioterapia. Fisioter Mov. 2011;24:523-33.

-

30Ciconelli RM, Ferraz MB, Santos WS, Meinão I, Quaresma MR. Tradução para a língua portuguesa e validação do questionário genérico de avaliação de qualidade de vida SF-36 (Brasil SF-36). Rev Bras Reumatol. 1999;39:143-50.

-

31Stella F, Gobbi S, Corazza DI, Costa JL. Depressão no idoso: diagnóstico, tratamento e benefícios da atividade física. Motriz. 2002;8:91-8.

-

32Netuveli G, Blane D. Quality of life in older ages. Br Med Bull. 2008;85:113-26. Epub 2008 Feb 15.

-

33Fleck MP, Chachamovich E, Trentini CM. [WHOQOL-OLD Project: method and focus group results in Brazil]. Rev Saude Publica. 2003;37:793-9. Epub 2003 Nov 27.

-

34Rabins PV, Kasper JD, Kleinman L, Black B, Patrick DL. Concepts and methods in the development of the ADRQL: an instrument for assessing health-related quality of life in persons with Alzheimer's disease. J Ment Health Aging. 1999;5:33-48.

-

Financial support: none.

-

Suggested citation: Tavares BB, Moraes H, Deslandes AC, Laks J. Impact of physical exercise on quality of life of older adults with depression or Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2014;36(3):134-139.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

Jul-Sep 2014

History

-

Received

16 Dec 2013 -

Accepted

12 June 2014