Abstracts

The fossil record of birds in Gondwana is almost restricted to the Late Cretaceous. Herein we describe a new fossil from the Araripe Basin, Cratoavis cearensis nov. gen et sp., composed of an articulated skeleton with feathers attached to the wings and surrounding the body. The present discovery considerably extends the temporal record of the Enantiornithes birds at South America to the Early Cretaceous. For the first time, an almost complete and articulated skeleton of an Early Cretaceous bird from South America is documented.

Cratoavis cearensis nov. gen et sp.; Araripe Basin; Fossil bird

No Gondwana, o registro fóssil de aves está praticamente restrito ao Cretáceo Superior. Neste estudo é descrito um novo fóssil da Bacia do Araripe, Cratoavis cearensis nov. gen. et sp., composto por um esqueleto articulado com penas conectadas às asas e circundando o corpo. A presente descoberta amplia consideravelmente o intervalo temporal de registro das aves Enantiornithes na América do Sul ao Cretáceo Inferior. Pela primeira vez, um esqueleto articulado e quase completo de uma ave do Cretáceo Inferior da América do Sul é documentado.

Cratoavis cearensis nov. gen. et sp.; Bacia do Araripe; Ave fóssil

INTRODUCTION

In South America, the Cretaceous avian record is composed of several taxa, including basal ornithothoracine birds, enantiornithes, and derived ornithurines, including Neornithes-like taxa (Walker 1981Walker C. 1981. New subclass of birds from the Cretaceous of South America. Nature, 292:51-53., Alvarenga & Bonaparte 1992Alvarenga H. & Bonaparte J.F. 1992. A new flightless land bird from the Cretaceous of Patagonia. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Science Series, 36:51-64., Chiappe 1993Chiappe L.M. 1993. Enantiornithean (Aves) tarsometatarsi fro the Cretaceous Lecho Formation of Northwestern Argentina. American Museum Novitates 3083:1-27., 1996Chiappe L.M. 1996. Early avian evolution in the Southern Hemisphere: the fossil record of birds in the Mesozoic of Gondwana. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, 39:533-554., Chiappe & Calvo 1994Chiappe L.M. & Calvo J.O. 1994. Neuquenornis volans, a new Late Cretaceous bird (Enantiornithes: Avisauridae) from Patagonia, Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 14:230-246., Clarke & Chiappe 2001Clarke J.A. & Chiappe L.M. 2001. A new Carinate bird from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia (Argentina). American Museum Novitates, 3323:1-23., Agnolin & Martinelli 2009Agnolin F.L. & Martinelli A.G. 2009. Fossil birds from the Late Cretaceous Los Alamitos Formation, Río Negro province, Patagonia. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 27:42-49., Agnolín 2010Agnolin F.L. 2010. An avian coracoid from the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina. Studia Geologica Salmanticensia, 46:99-119.). Regarding the regional record, in Brazil, only sparse mentions have been made up to the date. Only three reports of Cretaceous birds are known for the entire country, including unpublished indeterminate enantiornithine birds from Presidente Prudente locality (Alvarenga & Nava 2005Alvarenga H. & Nava W.R. 2005. Aves Enantiornithes do Cretáceo Superior da Formação Adamantina do Estado de Sao Paulo, Brasil. In: Congreso Latinoamericano de Paleontología de Vertebrados, 2, Rio de Janeiro, Agosto de 2005, p. 20.), and indeterminate birds from Jales locality (Azevedo et al. 2007Azevedo R.P., Vasconcellos P.L., Candeiro C.R.A., Bergqvist L.P. 2007. Restos microscopicos de vertebrados fosseis do Grupo Bauru (Neocretaceo), no oeste do Estado de Sao Paulo, Brasil. In: Carvalho I.S., Cassab R.C., Schwanke C., Cavalho M.A., Fernandes A.C., Rodrigues M.A.C., Carvalho M.S., Arai M., Oliveira M.E.Q. (eds.) Paleontologia: Cenários da Vida. Vol. 2. Interciência, p. 541-549.), both coming from the Adamantina Formation (Turonian-Santonian, Bauru Group). More recently, Candeiro et al. (2012)Candeiro C.R., Agnolin F.L., Martinelli A.G., Buckup P.A. 2012. First bird remains from the Upper Cretaceous of the Peirópolis site, Minas Gerais state, Brazil. Geodiversitas, 34(3):617-624. reported from the Late Maastrichtian, fragmentary specimens referable to indeterminated birds and enantiornithes from the Marília Formation, at the Minas Gerais State.

There are also few reports concerning fossil birds from the Araripe Basin. All the available data comes from the Santana Formation, Crato Member. Kellner (2002)Kellner A.W.A. 2002. A review of avian Mesozoic fossil feathers In: Chiappe L.M.& Witmer L.M. (eds.) Mesozoic Birds: above the heads of dinosaurs. Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 389-404., Kellner et al. (1991Kellner A.W.A., Martins-Neto R.G., Maisey J.G. 1991. Undetermined feather. In: Maisey J.G. (ed.) Santana Fossils, an Illustrated Atlas. Neptune City, NJ: T.F.H. Publications, p. 376-377., 1994Kellner A.W.A., Maisey J.G., Campos D.A. 1994. Fossil down feather from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil. Palaeontology, 37:489-492.), Martins-Neto and Kellner (1988)Martins-Neto R.G. & Kellner A.W.A. 1988. Primeiro registro de pena na Formação Santana (Cretáceo Inferior), Bacia do Araripe, nordeste do Brasil. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 60:61-68. and Martill and Filgueira (1994)Martill D.M. & Filgueira J.B.M. 1994. A new feather from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil. Palaeontology, 37:483-487. described feathers and plumes with fine details such as colour patterns preserved as dark and light transverse bands. Although they are generally assigned as belonging to Aves, probably are derived from several different taxa, including some non-avian theropod clades, such as Oviraptorosauria, Troodontidae or Dromaeosauridae (Naish et al. 2007Naish D., Martill D.M., Merrick I. 2007. Birds of the Crato Formation. In:, Martill, D.M., Bechly, G. Loveridge, R.F. (eds.) Crato Fossil Beds of Brazil: Window into an Ancient World. Cambridge University Press, p. 525-533.). On the other hand, osteological remains are restricted to two specimens. The first one, an unlabelled specimen from Senckenberg Museum (Frankfurt, Germany) presents presumed carpal bones associated with three asymmetrical feathers. The second, held in a private collection in Japan, consists of a poorly preserved articulated specimen, with an incomplete skull, vertebrae, ilium, a possible ischium and a probable left hindlimb. Naish et al. (2007)Naish D., Martill D.M., Merrick I. 2007. Birds of the Crato Formation. In:, Martill, D.M., Bechly, G. Loveridge, R.F. (eds.) Crato Fossil Beds of Brazil: Window into an Ancient World. Cambridge University Press, p. 525-533. considered that this second specimen presents neural spines of the dorsal vertebrae and the morphology of the centre of the dorsal vertebrae that suggest a relationship with the euenantiornithines. More recently, Carvalho et al. (2015)Carvalho I.S., Novas F.E., Agnolin F.L., Isasi M.P., Freitas F.I., Andrade J. 2015. A Mesozoic bird from Gondwana preserving feathers. Nature Communications DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8141.

https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8141...

described a nearly complete skeleton and associated feathers of a still unnamed enantiornithine bird from the Crato Member (Santana Formation - Aptian, Araripe Basin). The association of feathers and the almost complete skeleton points it as an exceptional fossil bird from the Early Cretaceous deposits. The aim of the present paper is to coin a new name for this specimen, as well as to make some comparisons with other enantiornithine birds.

GEOLOGICAL CONTEXT

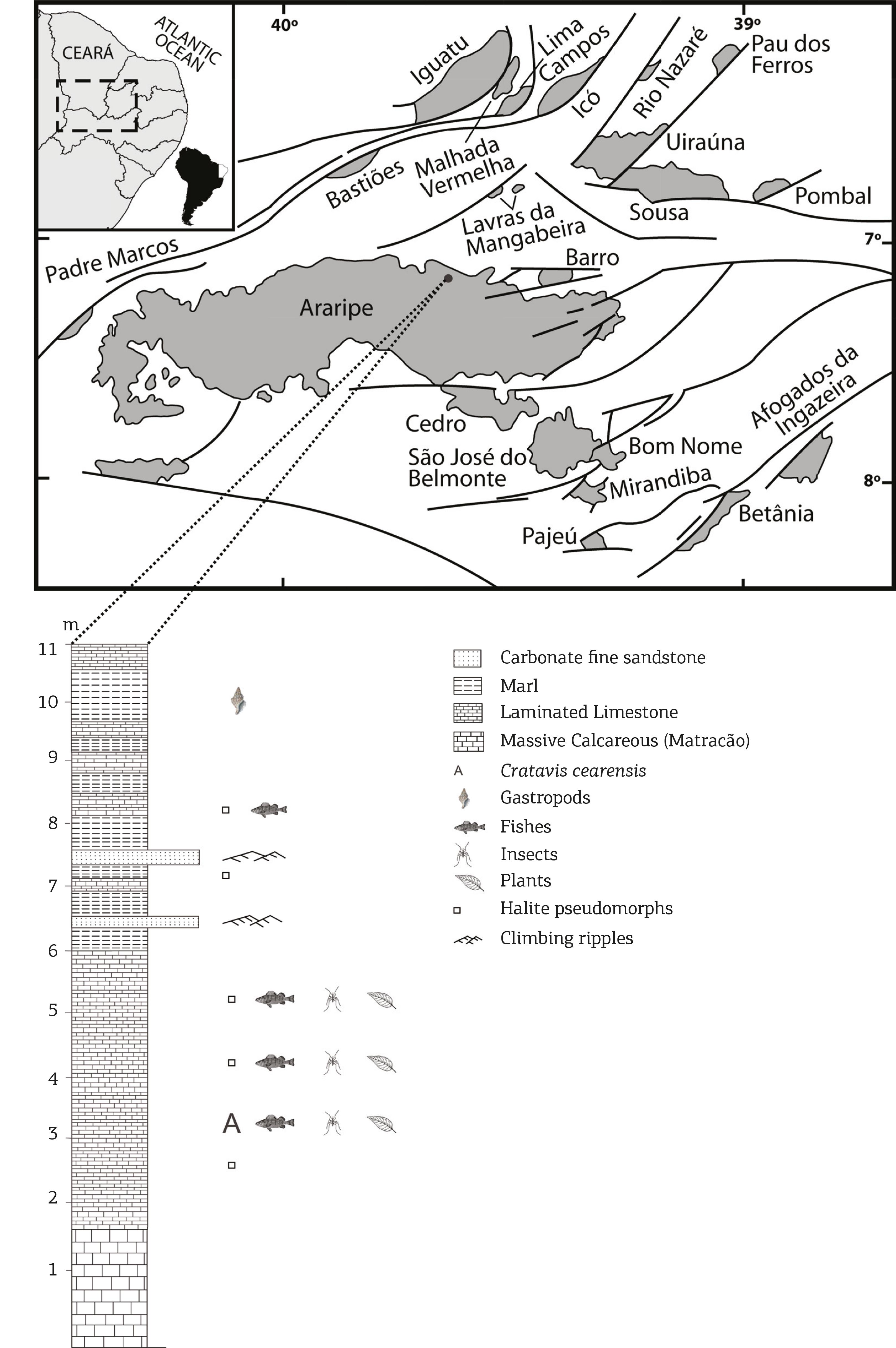

The southern hemisphere was deeply changed during the Early Cretaceous times. The intense tectonic activity, related to the initial stages of the Gondwanic crust rupturing, led to the disappear, but also to the flourish of new ecological niches. These events are registered in the interior of Northeastern region of Brazil, in intracratonic basins developed along pre-existing Precambrian structural trends. One of these sedimentary areas is the Araripe Basin, which has 12,200 km2 and its Early Cretaceous history spans from Berriasian to Albian times (Fig. 1). This basin was mainly filled, during Early Cretaceous, with clastic and chemical rocks (Carvalho 2000Carvalho I.S. 2000. Geological environments of dinosaur footprints in the intracratonic basins from Northeast Brazil during South Atlantic opening (Early Cretaceous). Cretaceous Research, 21:255-267.). The lithostratigraphy of the basin has been discussed by many authors (Beurlen 1963Beurlen K. 1963. Geologia e estratigrafia da Chapada do Araripe. In: Congresso Nacional de Geologia, 17 Recife, Recife, Sociedade Brasileira de Geologia, Núcleo Pernambuco, Boletim, 47 p., 1971Beurlen K. 1971. As condições ecológicas e faciológicas da Formação Santana na Chapada do Araripe (Nordeste do Brasil). Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 43(suplemento):411-415.; Cavalcanti & Viana 1992Cavalcanti V.M.M. & Viana M.S.S. 1992. Revisão estratigráfica da Formação Missão Velha, Bacia do Araripe, Nordeste do Brasil. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 64(2):155-168., Assine 1992Assine M.L. 1992. Paleocorrentes na bacia do Araripe, Nordeste do Brasil. In: Simpósio sobre as bacias Cretácicas Brasileiras, 2, Rio Claro, São Paulo, Resumos Expandidos, p. 59-60., Ponte 1992Ponte F.C. 1992. Origem e evolução das pequenas bacias cretácicas do interior do Nordeste do Brasil. In: Simpósio sobre as Bacias Cretácicas Brasileiras, 2, Rio Claro, São Paulo, Resumos Expandidos, p. 55-58., Martill 1993Martill D.M. (ed.). 1993. Fossils of the Santana and Crato Formations, Brazil. Field Guides to Fossils, no. 5. London: The Palaeontological Association. Wiley-Blackwell, 160 p., Martill & Wilby 1993Martill D.M.& Wilby P.R. 1993. Stratigraphy. In: Martill, D.M. (ed.) Fossils of the Santana and Crato Formations, Brazil. Field Guides to Fossils, 5. London: The Palaeontological Association , p. 20-50., Viana & Neuman 1999Viana M.S.S. & Neumann, V.H.L. 1999. The Crato Member of the Santana Formation, Ceará State. In: Schobbenhaus C., Campos D.A., Queiroz E.T., Winge M., Berbert B. (eds.) Sitios Geológicos e Paleontológicos do Brasil, p. 1-10., Assine 2007Assine M.L. 2007. Bacia do Araripe. Boletim de Geociências da Petrobras, 15(2):371-389.).

Location map of the Araripe Basin in the context of the Cretaceous Brazilian Northeastern intracratonic basins and stratigraphical profi le from the location where the fossil was collected. Pedra Branca Mine, Nova Olinda County, Brazil (7º 6' 51.9" S and 39º 41' 46.9" W).

The new fossil was collected in the Crato Member (Aptian) of Santana Formation (Fig. 2). The outcrops are distributed around Chapada do Araripe plateau, in the southern Ceará, western Pernambuco and south-eastern Piauí States (Martill 1993Martill D.M. (ed.). 1993. Fossils of the Santana and Crato Formations, Brazil. Field Guides to Fossils, no. 5. London: The Palaeontological Association. Wiley-Blackwell, 160 p., Viana & Neuman 1999Viana M.S.S. & Neumann, V.H.L. 1999. The Crato Member of the Santana Formation, Ceará State. In: Schobbenhaus C., Campos D.A., Queiroz E.T., Winge M., Berbert B. (eds.) Sitios Geológicos e Paleontológicos do Brasil, p. 1-10.). This lithostratigraphic unit is considered a fossil Lagerstätte, due the large amount and quality of its fossil preservation. The Crato Member fossils probably represent one of the most well-known terrestrial flora and fauna from the Aptian time. In fact, a large amount of faunistic remains has been described, including worms, insects, spiders, fishes, basal lizards, turtles, crocodiles, non-avian dinosaurs and possible birds (see Martill et al. 2007Martill D.M., Bechly G., Loveridge R.F. (eds.) 2007. Crato Fossil Beds of Brazil: Window into an Ancient World. Cambridge University Press. 625 p.).

Outcrop where the fossil was collected. Pedra Branca Mine, Nova Olinda County, Brazil (7º 6' 51.9" S and 39º 41' 46.9" W).

The Crato Member comprises essentially laminated carbonate strata with some inter-bedded levels of fine sandstones, marls and clays. This succession is interpreted as a lacustrine environment, in a rift basin context, that constituted an important area for an abundant endemic biota. The climate was at that time hot and arid. The connection between South America and Africa as a single, large continental block did not allow a higher humidity, in what was the continental interior. During the time interval of the carbonate succession, where the new bird species was found, occurred many important environmental changes. The climate gradually became more humid, as the tectonic events that drove the separation of South America and Africa led to the origin of the equatorial Atlantic Ocean (Carvalho 2004Carvalho I.S. 2004. Dinosaur footprints from Northeastern Brazil: taphonomy and environmental setting. Ichnos, 11:311-324., Carvalho & Pedrão 1998Carvalho I.S. & Pedrão E. 1998. Brazilian theropods from the Equatorial Atlantic margin: behavior and environmental setting. Gaia, Lisboa, 15:369-378., Medeiros et al. 2014Medeiros M.A., Lindoso R.M., Mendes I.D., Carvalho I.S. 2014. The Cretaceous (Cenomanian) continental Record of the Laje do Coringa flagstone (Alcântara Formation), northeastern South America. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 53:50-58.).

The distribution of the laminated limestones of Crato Member throughout the Araripe Basin, allowed Martill et al. (2007)Martill D.M., Bechly G., Loveridge R.F. (eds.) 2007. Crato Fossil Beds of Brazil: Window into an Ancient World. Cambridge University Press. 625 p. to estimate the depositional area as a water body with a minimum extent of some 18,000 km2. The brackish water was an alkaline environment, in which occurred some hypersaline stages represented by carbonates with pseudomorphs of halite crystals. Menon and Martill (2007)Menon F. & Martill D.M.2007. Taphonomy and preservation of Crato Formation arthropods. In:, Martill, D.M. Bechly, G., Loveridge, R.F. (eds.) Crato Fossil Beds of Brazil: Window into an Ancient World. Cambridge University Press, p. 79-96. observed that the lack of reworked horizons within as much as 13 meters of laminite suggests considerable water depth and deposition probably under anoxic botton water. The integration of lithological and petrographic evidences by Heimhofer et al. (2010)Heimhofer U., Ariztegui D., Lenniger M, Hesselbo S.P., Martill D.M., Rios-Netto A.M. 2010. Deciphering the depositional environment of the laminated Crato fossil beds (Early Cretaceous, Araripe Basin, North-eastern Brazil). Sedimentology, 57(2):677-694. indicates that the bulk of Crato Member limestone was formed via authigenic precipitation of calcite from within the upper water column, most probably induced and/or mediated by phytoplankton and picoplankton activity. The isotopic evidence indicates a shift from closed to semi-closed conditions towards a more open lake system during the onset of laminate deposition of the Crato Member.

The dating of this interval was presented by Rios-Netto et al. (2012)Rios-Netto A.M., Regali M.S.P., Carvalho I.S., Freitas F.I. 2012. Palinoestratigrafia do Intervalo Alagoas da Bacia do Araripe, Nordeste do Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Geociências, 42(2):331-342.. The biostratigraphical framework to the Alagoas Stage, based on palynological analyses proceeded on 167 samples from 14 wells drilled at the Eastern portion of the Araripe Basin, showed only the P-270.2 and P-280.1 subzones of Regali and Santos (1999)Regali M.S.P. & Santos P.R.S. 1999. Palinoestratigrafia e geocronologia dos sedimentos albo-aptianos das Bacias de Sergipe e Alagoas - Brasil. In: Simpósio sobre o Cretáceo do Brasil, 5, Simpósio sobre el Cretácico de America del Sur, 1, Boletim, p. 411-419.. These subzones are assigned to the late Aptian (119 - 113 Ma).

THE FOSSIL PRESERVATION

The Crato Member fossils are known by their exceptionally preservation. Specimens may be preserved three-dimensionally or at least with only minor compaction. Soft tissues, colour patterns and fine details, are exquisite, with preserved delicate structures of the anatomy of plants, invertebrates and vertebrates (Grimaldi 1990Grimaldi D. 1990. Insects from the Santana Formation, Lower Cretaceous, of Brazil. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 195:5-191., Brito & Martill 1999Brito P.M. & Martill D.M. 1999. Discovery of a juvenile coelacanth in the Lower Cretaceous, Crato Formation, Northeastern Brazil. Cybium, 23:209-211., Martill et al. 2007Martill D.M., Bechly G., Loveridge R.F. (eds.) 2007. Crato Fossil Beds of Brazil: Window into an Ancient World. Cambridge University Press. 625 p.). In plants, many fossils are preserved more or less entire, often with roots, stems, leaves, sporangia and flowering structures attached. The original organic material is generally covered or replaced by goethite (Mohr et al. 2007Mohr B.A.R., Bernardes-de-Oliveira M.E.C., Loveridge R.F.2007. The macrophyte flora of the Crato Formation. In:, Martill D.M., Bechly G. Loveridge R.F. (eds.) Crato Fossil Beds of Brazil: Window into an Ancient World. Cambridge University Press, p. 537-565.). The preservation of invertebrates, such as arthropods, can be highly variable. Therefore, there are essentially, two types: replacement by goethite, or as black, carbonaceous replicas with finely disseminated pyrite (Menon & Martill 2007Menon F. & Martill D.M.2007. Taphonomy and preservation of Crato Formation arthropods. In:, Martill, D.M. Bechly, G., Loveridge, R.F. (eds.) Crato Fossil Beds of Brazil: Window into an Ancient World. Cambridge University Press, p. 79-96.). In vertebrates, like fishes, it is common fully articulated skeletons, and occasionally with in situ stomach contents. An important feature of the high-quality soft-tissue preservation are found in pterosaurs, including cranial crest, wing membranes and wing fibers, claw sheaths, foot webs and a heel pad (Maisey 1991Maisey J. 1991. Santana Fossils: an Illustrated Atlas. Neptune City, NJ: T.F.H. Publications, 459 p., Campos & Kellner 1997Campos D.A. & Kellner A.W.A. 1997. Short note on the first occurrence of Tapejaridae in the Crato Member (Aptian), Santana Formation, Araripe Basin, Northeast Brazil. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 69:83-87., Frey et al. 2003Frey E., Tischlinger, H., Buchy, M.-C., Martill, D.M. 2003. New specimens of Pterosauria (Reptilia) with soft parts with implications for pterosaurian anatomy and locomotion. In: Buffetaut E. & Mazin J.-M. (eds.) Evolution and Palaeobiology of Pterosaurs. Geological Society of London, Special Publication, 217:233-266., Pinheiro et al. 2012Pinheiro F.L., Horn B.L.D., Schultz C.L., Andrade J.A.F.G., Sucerquia P.A. 2012. Fossilized bacteria in a Cretaceous pterosaur headcrest. Lethaia, 45:495-499.).

The studied bird specimen show articulated skeleton with feathers and plumes. There are probably soft tissues around the skull, sometimes presented as a dotted surface, resembling skin fragments. Also around the skull there is a distinct brownish pigmentation, due the presence of small plumes. The skull shows an orbit round and large, with a partially preserved sclerotic ring. There is a short beak. There are the bones and impression of both forelimbs and wings. The wings and body present small brownish contour feathers with pennaceous and plumaceous vanes. The forelimbs are only partially present, with the humerus, radius, ulna and some finger bones. It is possible to recognize one short claw. In the hindlimbs it is observed white-yellowish elongated muscular fibers bordering the femur. The foots present four long digits with curved claws. In the abdominal area there are some long and thin bones that were probably part of a gastralia. After a short pygostyle there are two long parallel rectrices feathers preserved as fine impressions with calamus, rachis and pennaceous vanes. It is possible to observe on them colour patterns as dark lunar transversal bands on the first third of the feather. The bones are preserved three-dimensionally, although sometimes show partial crushing. They are of a dark brown colour and generally occur as articulated bones.

This exquisite preservation occurred in a context of alkaline, hypersaline water. Menon and Martill (2007)Menon F. & Martill D.M.2007. Taphonomy and preservation of Crato Formation arthropods. In:, Martill, D.M. Bechly, G., Loveridge, R.F. (eds.) Crato Fossil Beds of Brazil: Window into an Ancient World. Cambridge University Press, p. 79-96. considered that high salinities, and also anoxic bottom waters, may inhibit macro-scavengers and bioturbation, allowing in this way that the carcasses could remain intact for a considerable time. There are also an important role of the microbial communities, in which microbial mats are partly responsible for limiting attacks from scavengers and preventing disarticulation. Other aspect concerns to the environment of the depositional area. As demonstrated by Brocklehurst et al. (2012)Brocklehurst N., Upchurch P., Mannion P.D., O'Connor J. 2012. The Completeness of the Fossil Record of Mesozoic Birds: Implications for Early Avian Evolution. PLoS ONE, 7(6):e39056., Mesozoic birds living nearby fluviolacustrine environments, due the taphonomic processes, tend to be more complete than those living in marine or other terrestrial environments.

SYSTEMATIC PALEONTOLOGY

Aves Linnaeus 1758

Ornithothoraces Chiappe 1996

Enantiornithes Walker 1981

Euenantiornithes Chiappe & Walker 2001

Holotype specimen of Cratoavis cearensis nov. gen. et sp. (UFRJ-DG 031Av), with selected skeletal elements showing diagnostic features. (A) main slab; (B) interpretative drawing of the skeleton and feathers; (C) dorsal vertebrae in right lateral view; (D) caudal vertebra in dorsal view; (E) left humerus in caudal view; (F) left coracoid in sternal view; (G) right foot.

Holotype

UFRJ-DG 031 Av (Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Departmento de Geologia collection), nearly complete skeleton, preserved in two slabs, including skull, nearly complete fore and hindlimbs, vertebral column and pectoral and pelvic girdles. However, as is usual in fossils preserved in two slabs, the bones are cracked. Some crushing and displacement of bones has occurred. Several bones, however, remain in articulation. The skull and neck are rotated ventrally with respect to the rest of the skeleton, and are exposed on the left side, whereas most of remaining skeleton is exposed on the right side. The skull and mandible suffered strong crushing and deformation, and most bones cannot be individualized. The pelvic girdle and hindlimb remain in anatomical position, whereas the pectoral girdle has been displaced ventrally with respect of the dorsal column. The minor slab shows better preserved bones than the main slab. It contains the impression of the skull, and both forelimbs and fragments of pectoral girdle. The ischia and sternum are not preserved.

The small size of the individual, the lack of fusion of tarsometatarsus, tibiotarsus, and carpometacarpus, supports the interpretation that the individual corresponds to an early ontogenetic stage (Chiappe et al. 2007Chiappe L.M., Shuan J., Qiang J. 2007. Juvenile birds from the Early Cretaceous of China: Implications for Enantiornithine ontogeny. American Museum Novitates, 3594:1-46.; Carvalho et al. 2015Carvalho I.S., Novas F.E., Agnolin F.L., Isasi M.P., Freitas F.I., Andrade J. 2015. A Mesozoic bird from Gondwana preserving feathers. Nature Communications DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8141.

https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8141...

). However, fused vertebral centra, as well as well-defined epiphyses of long bones, extensive pubic apron, and absence of surface pitting, indicate that the individual was probably adult specimen (Sanz et al. 1997Sanz J.L., Chiappe L.M., Pérez-Moreno B.P., Moratalla J.J., Hernandez-Carrasquilla, F., Buscalioni A.D., Ortega F., Poyato-Ariza F.J., Rasskin-Gutman D., Martınez-Delclos, X. 1997. A Nestling Bird from the Lower Cretaceous of Spain: Implications for Avian Skull and Neck Evolution. Science, 276:1543-1546.). In this way, we are not certain about the ontogenetic stage of the specimen.

Diagnosis

Minute Enantiornithes, diagnosed on the basis of the following combination of characters (autapomorphies marked by an asterisk): dentate maxilla, strongly concave medial margin of coracoid, dorsal vertebrae with fan-shaped and very well-developed neural spines, caudal neural spines transversely thick, proximally rounded humeral head, tibiotarsus shorter than femur and subequal in length to metatarsals, very elongate pedal phalanges of digit III*, and very long rectrices, much longer than total body size*.

Etymology

Cratoavis nov. gen., the generic name derives from the combination of the Crato Member lithostratigraphic unit, where the specimen was found, and the zoological group Aves. The specific epithet cearensis refers to the Ceará State, where the fossil was collected.

Locality and horizon

Pedra Branca Mine, Nova Olinda County, Ceará State, Brazil (7° 6´51.9´´ S and 39° 41´46.9´´ W). Araripe Basin, Santana Formation, Crato Member (Early Cretaceous, Aptian).

COMPARISONS

The holotype of Cratoavais cearensis was described in detail by Carvalho et al. (2015)Carvalho I.S., Novas F.E., Agnolin F.L., Isasi M.P., Freitas F.I., Andrade J. 2015. A Mesozoic bird from Gondwana preserving feathers. Nature Communications DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8141.

https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8141...

, and thus, description is not repeated here. Thus, only main comparisons with other Enantiornithes, with the aim to sustain its recognition as a new taxon are here afforded.

Enantiornithes are the most diverse lineage of Mesozoic birds with over 60 species named (Chiappe & Walker 2002Chiappe L.M.& Walker C.A. 2002. Skeletal morphology and systematics of Cretaceous Euenantiornithes (Ornithothoraces: Enantiornithes). In: Chiappe L.M.& Witmer L.M (eds.) Mesozoic birds: above the heads of dinosaurs. Berkeley University Press, p. 168-218., O´Connor 2009O`Connor J.K. 2009. A systematic review of Enantiornithes (Aves: Ornithothoraces). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Southern California, 600 p.). However, in spite of its good fossil record and high diversity, at least a third of named species are based upon extremely fragmentary specimens (O´Connor 2009O'Connor J.K., Wang X-R, Chiappe L.M., Gao C-H, Meng Q-J, Cheng X-D., Liu J-Y. 2009. Phylogenetic support for a specialized clade of Cretaceous enantiornithine birds with information from a new species. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 29:188-204.). Diagnosing a new species of Enantiornithes or justifying higher-level relationships may represent a difficult taxonomic task, mainly due to their small size and homogeneous morphology, and because of it, their taxonomy remains largely unreviewed (O´Connor & Dyke 2010O'Connor J.K. & Dyke G.J. 2010. A reassessment of Sinornis santensis and Cathayornis yandica (Aves: Ornithothoraces). In: International Meeting of the Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution, 7, Records of the Australian Museum, 62(1):7-20.). After, we made comparisons between Cratoavis nov. gen. and different enantiornithine genera and clades.

Cratoavis nov. gen. is referred as Enantiornithes on the basis of the following synapomorphies (Carvalho et al. 2015Carvalho I.S., Novas F.E., Agnolin F.L., Isasi M.P., Freitas F.I., Andrade J. 2015. A Mesozoic bird from Gondwana preserving feathers. Nature Communications DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8141.

https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8141...

): proximally forked and distally constricted pygostyle with a ventrolateral process, convex lateral margin of coracoid, scapulocoracoid articulation with scapular pit and coracoid tuber, distal end of metacarpal III more distally extended than the metacarpal II, distal tarsals fused to proximal metatarsus, but remaining portion of metatarsals free. Sereno (2000)Sereno P. 2000. Iberomesornis romerali (Aves, Ornithothoraces) reevaluated as an Early Createcous enantiornithean. Neues Jahrbuch fur Geologie und Paleontologie, 215:365-395. also added a suite of purported synapomorphies that may allow to reinforce the inclusion of Cratoavis nov. gen. to Enantiornithes: metatarsal I with posteriorly reflected distal condyles ("J" shaped) and the distal condyles joined along its dorsal margin.

Referral of Cratoavis nov. gen. to Euenantiornithes is based on the following derived features (Chiappe & Walker 2002Chiappe L.M.& Walker C.A. 2002. Skeletal morphology and systematics of Cretaceous Euenantiornithes (Ornithothoraces: Enantiornithes). In: Chiappe L.M.& Witmer L.M (eds.) Mesozoic birds: above the heads of dinosaurs. Berkeley University Press, p. 168-218.; see Carvalho et al. 2015Carvalho I.S., Novas F.E., Agnolin F.L., Isasi M.P., Freitas F.I., Andrade J. 2015. A Mesozoic bird from Gondwana preserving feathers. Nature Communications DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8141.

https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8141...

): parapophyses placed on the central part of the thoracic vertebra, prominent bicipital crest of humerus, shaft of radius with a longitudinal groove on its posterior surface, very large posterior femoral trochanter, and metatarsal IV significantly thinner than metatarsals II and III.

Chiappe and Walker (2002)Chiappe L.M.& Walker C.A. 2002. Skeletal morphology and systematics of Cretaceous Euenantiornithes (Ornithothoraces: Enantiornithes). In: Chiappe L.M.& Witmer L.M (eds.) Mesozoic birds: above the heads of dinosaurs. Berkeley University Press, p. 168-218. indicate that Euenantiornithes may exclude some basal enantiornithes. Among them, they cited Iberomesornis and Noguerornis. As member of Euenantiornithes, Cratoavis nov. gen. may be clearly distinguished from both genera. At first sight, Cratoavis nov. gen. resemblesIberomesornis in having plesiomorphically anteroposteriorly short cervical and dorsal vertebral centra, and a simple proximal humeral morphology (Sanz & Bonaparte 1992Sanz J.L. & Bonaparte J.F 1992. A New Order of Birds (Class Aves) from the Lower Cretaceous of Spain. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Contributions in Science, 36:38-49.; Sereno 2000Sereno P. 2000. Iberomesornis romerali (Aves, Ornithothoraces) reevaluated as an Early Createcous enantiornithean. Neues Jahrbuch fur Geologie und Paleontologie, 215:365-395.). However, Cratoavis nov. gen. differs in having fan-shaped distal margin of dorsal neural spines, in contrast to Iberomesornis in which they are low and with a subcuadrangular contour (Sereno 2000Sereno P. 2000. Iberomesornis romerali (Aves, Ornithothoraces) reevaluated as an Early Createcous enantiornithean. Neues Jahrbuch fur Geologie und Paleontologie, 215:365-395.), well-developed neural spines on caudal vertebrae, ulna as long as humerus (longer than humerus in Iberomesornis; Sereno, 2000Sereno P. 2000. Iberomesornis romerali (Aves, Ornithothoraces) reevaluated as an Early Createcous enantiornithean. Neues Jahrbuch fur Geologie und Paleontologie, 215:365-395.), and gracile pedal phalanges. Furthermore, Cratoavis nov. gen. is distinguished by the poorly known Noguerornis by having a wider intermetacarpal space, and by a nearly straight humeral shaft (Chiappe & Lacasa-Ruiz 2002Chiappe L.M. & Lacasa-Ruiz A. 2002. Noguerornis gonzalezi (Aves: Ornithothoraces) from the Early Cretaceous of Spain. In: Chiappe L.M.& Witmer L.M. (eds.) Mesozoic Birds: above the heads of dinosaurs. University of California Press, p. 230-239.).

The inclusion of Cratoavis nov. gen. within Euenantiornithes seems well sustained. However, as pointed out by Walker & Dyke (2009)Walker C.A. & Dyke G.J. 2009. Euenantiornithine birds from the Late Cretaceous of El Brete (Argentina). Irish Journal of Earth Sciences, 27:15-62., in spite of the anatomical distinctiveness and ecological variability, the phylogenetic relationships among euenantiornithine genera still remains in state of flux, and little phylogenetic resolution has been achieved, lacking consensus about their interrelationships (Chiappe & Walker 2002Chiappe L.M.& Walker C.A. 2002. Skeletal morphology and systematics of Cretaceous Euenantiornithes (Ornithothoraces: Enantiornithes). In: Chiappe L.M.& Witmer L.M (eds.) Mesozoic birds: above the heads of dinosaurs. Berkeley University Press, p. 168-218.; Chiappe et al. 2007Chiappe L.M., Shuan J., Qiang J. 2007. Juvenile birds from the Early Cretaceous of China: Implications for Enantiornithine ontogeny. American Museum Novitates, 3594:1-46.; O´Connor et al. 2011aO'Connor J.K., Zhou Z-H, Zhang F-C. 2011a. A reappraisal of Boluochia zhengi (Aves: Enantiornithes) and a discussion of intraclade diversity in the Jehol Avifauna, China. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology,9(1):51-63., 2011bO'Connor J.K., Chiappe L.M., Gao C-L, Zhao B. 2011b. Anatomy of the Early Cretaceous bird Rapaxavis pani (Aves: Enantiornithes). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 56(3):463-475., 2013O'Connor J.K., Zhang Y., Chiappe L.M., Meng Q., Quanguo L., Di L. 2013. A new enantiornithine from the Yixian Formation with the first recognized avian enamel specialization. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 33(1):1-12.). In this way, the position of Cratoavis nov. gen. within Euenantiornithes is unresolved, as indicated by Carvalho et al. (2015)Carvalho I.S., Novas F.E., Agnolin F.L., Isasi M.P., Freitas F.I., Andrade J. 2015. A Mesozoic bird from Gondwana preserving feathers. Nature Communications DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8141.

https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8141...

. However, the combination of anatomical traits present in specimen UFRJ-DG 031 Av serves as basis to coin the new genus and species Cratoavis cearensis within enantiornithines.

Cratoavis nov. gen. clearly differs from basal clade Longipterygidae (composed by Boluochia, Longirostravis, Longipteryx, Shanweiniao, Rapaxavis, Shnegjingornis; O´Connor et al. 2009O`Connor J.K. 2009. A systematic review of Enantiornithes (Aves: Ornithothoraces). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Southern California, 600 p., 2010Novas F.E., Agnolín F.L., Scanferla C.A. 2010. New enantiornithine bird (Aves, Ornithothoraces) from the Late Cretaceous of NW Argentina. Comptes Rendus Palevol., 9(8):499-503.; Li et al. 2012Li L., Wang J., Zhang X., Hou S. 2012. A New Enantiornithine Bird from the Lower Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation in Jinzhou Area, Western Liaoning Province, China. Acta Geologica Sinica, 86(5):1039-1044.) by lacking an elongate and acute rostrum, coracoid transverselly narrower, poorly curved pedal unguals, and relatively longer tarsometatarsus and manus, among other anatomical details. On the other side it may be distinguished from the avisaurids Soroavisaurus, Lectavis, Yungavolucris, Intiornis and Neuquenornis in having nearly flat cranial surface of metatarsal III (Chiappe 1993Chiappe L.M. 1993. Enantiornithean (Aves) tarsometatarsi fro the Cretaceous Lecho Formation of Northwestern Argentina. American Museum Novitates 3083:1-27.; Chiappe & Calvo 1994Chiappe L.M. & Calvo J.O. 1994. Neuquenornis volans, a new Late Cretaceous bird (Enantiornithes: Avisauridae) from Patagonia, Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 14:230-246.; Novas et al. 2011Novas F.E., Agnolín F.L., Scanferla C.A. 2010. New enantiornithine bird (Aves, Ornithothoraces) from the Late Cretaceous of NW Argentina. Comptes Rendus Palevol., 9(8):499-503.). Furthermore, Cratoavis nov. gen. differs from Neuquenornis in having a more stouter metatarsus and transverselly wider coracoid (Chiappe & Calvo 1994Chiappe L.M. & Calvo J.O. 1994. Neuquenornis volans, a new Late Cretaceous bird (Enantiornithes: Avisauridae) from Patagonia, Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 14:230-246.). Dorsal vertebrae are shorter than those of Neuquenornis (Chiappe & Calvo 1994Chiappe L.M. & Calvo J.O. 1994. Neuquenornis volans, a new Late Cretaceous bird (Enantiornithes: Avisauridae) from Patagonia, Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 14:230-246.). Moreover, Cratoavis nov. gen. differs from Intiornis, Soroavisaurus, and Avisaurus in lacking a medially oriented II trochlea of metatarsus (Varricchio & Chiappe 1995Varricchio D.J. & Chiappe L.M. 1995. A new enantiornithine bird from the Upper Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation of Montana. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 15(1):201-204.; Novas et al. 2011Novas F.E., Agnolín F.L., Scanferla C.A. 2010. New enantiornithine bird (Aves, Ornithothoraces) from the Late Cretaceous of NW Argentina. Comptes Rendus Palevol., 9(8):499-503.). In addition, Intiornis and Soroavisaurus exhibit a proximal fenestra between metatarsals III and IV (Novas et al. 2011Novas F.E., Agnolín F.L., Scanferla C.A. 2010. New enantiornithine bird (Aves, Ornithothoraces) from the Late Cretaceous of NW Argentina. Comptes Rendus Palevol., 9(8):499-503.). Lectavis and Yungavolucris clearly differ from Cratoavis nov. gen. in having highly specilized metatarsals, the former exhibits a very stout and wide metatarsus, whereas the second shows extremely elongate and gracile metatarsals (Chiappe 1993Chiappe L.M. 1993. Enantiornithean (Aves) tarsometatarsi fro the Cretaceous Lecho Formation of Northwestern Argentina. American Museum Novitates 3083:1-27.).

Cratoavis nov. gen. differs from the basal euenantiornithine Protopteryx in lacking a procoracoid process and lateral process on coracoid, in having reduced manual phalanx 1-I, and proximally fused carpometacarpus (Zhang & Zhou 2000Zhang F & Zhou Z. 2000. A Primitive Enantiornithine Bird and the Origin of Feathers. Science, 290:1955-1959.). From the flightless enantiornithine Elsornis, Cratoavis nov. gen. differs in several anatomical details, including a much more expanded and well-developed proximal end of the humerus, and a more gracile and straighter ulnar shaft (Chiappe et al. 2007Chiappe L.M., Shuan J., Qiang J. 2007. Juvenile birds from the Early Cretaceous of China: Implications for Enantiornithine ontogeny. American Museum Novitates, 3594:1-46.).

The humerus of Cratoavis nov. gen. is relativelly elongate and gracile, whereas in the Boahiornithidae Boahiornis, Sulcavis, Alethoalaornis, Xiangornis is much more robust and stouter (Li et al. 2009Li L., Hu D., Duan D., Gong E., Hou L. 2009. Alethoalaornithidae fam. nov.: a new family of enantiornithine bird from the Lower Cretaceous of western Liaoning. Acta Palaeontologica Sinica, 46(3):365-372.; Hu et al. 2011Hu D.-Y, Xu X., Hou L., Sullivan, C. 2011. A new enantiornithine bird from the Lower Cretaceous of Western Liaoning, China, and its implications for early avian evolution. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 32(3):639-645.; O´Connor et al. 2013O'Connor J.K., Chiappe L.M., Gao K-Q. 2010. A new species of ornithuromorph (Aves: Ornithothoraces) bird from the Jehol Group indicative of higher-level diversity. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology,30(2):311-321.). Rounded humeral head differs from the saddle-shaped condition present in most Enantiornithes (e.g., Elsornis, Cathayornis, Concornis, Gobipteryx, Halimornis, Eoalulavis, Gurilynia, Otogornis, Hebeiornis, Gracilornis, Sulcavis, Sinornis, Martinavis, Elbretornis and Enantiornis; Sanz et al. 1995Sanz J.L., Chiappe, L.M., Buscalioni, A.D. 1995. The osteology of Concornis lacustris (Aves: Enantiornithes) from the Lower Cretaceous of Spain and a reexamination of its phylogenetic relationships. American Museum Novitates, 3133:1-23., 2002Sanz J., Pérez-Moreno B., Chiappe L., Buscalioni A. 2002. The birds from the lower Cretaceous of las hoyas (Province of Cuenca, Spain). In: Chiappe, L.M. & Witmer, L.M. (eds.) Mesozoic birds: above the heads of dinosaurs. Berkeley University Press, p. 209-229.; Sereno et al. 2002Sereno P., Rao C., Li J. 2002. Sinornis santensis (Aves: Enantiornithes) from the Early Cretaceous of Northeastern China. In: Chiappe L.M.& Witmer L.M. (eds.) Mesozoic birds: above the heads of dinosaurs. Berkeley University Press, p. 184-208., Zhou & Hou 2002Zhou Z. & Hou L. 2002. The Discovery and Study of Mesozoic Birds in China. In: Chiappe L.M.& Witmer L.M. (eds.) Mesozoic birds: above the heads of dinosaurs. Berkeley University Press, p. 160-183.; Chiappe et al. 2002Chiappe L.M., Lamb J.P., Ericson P.G.P. 2002. New enantiornithine bird from the marine Upper Cretaceous of Alabama. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 22:170-174., 2007Chiappe L.M., Shuan J., Qiang J. 2007. Juvenile birds from the Early Cretaceous of China: Implications for Enantiornithine ontogeny. American Museum Novitates, 3594:1-46.; Zhang et al. 2004Zhang F., Ericson G.P., Zhou Z. 2004. Description of a new enantiornithine bird from the Early Cretaceous of Hebei, northern China. Canadian Journal of Earth Science, 41:1097-1107., Walker & Dyke 2009Walker C.A. & Dyke G.J. 2009. Euenantiornithine birds from the Late Cretaceous of El Brete (Argentina). Irish Journal of Earth Sciences, 27:15-62.; Li & Hou 2011Li L. & Hou S. 2011. Discovery of a new bird (Enantiornithines) from Lower Cretaceous in western Liaoning, China. Journal of Jilin University (Earth Science Edition), 41(3):759-763.; O´Connor et al. 2013O'Connor J.K., Zhang Y., Chiappe L.M., Meng Q., Quanguo L., Di L. 2013. A new enantiornithine from the Yixian Formation with the first recognized avian enamel specialization. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 33(1):1-12.), a character that was considered as synapomorphy of enantiornithes by previous authors (O´Connor et al. 2013O'Connor J.K., Zhang Y., Chiappe L.M., Meng Q., Quanguo L., Di L. 2013. A new enantiornithine from the Yixian Formation with the first recognized avian enamel specialization. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 33(1):1-12.). In Cratoavis nov. gen. the transverse ligamental groove and the capital groove of the humerus are poorly defined, which differs from the deep and well-defined groove present in Eoenantiornis (Zhou et al. 2005Zhou Z., Chiappe L.M., Zhang F. 2005. Anatomy of the Early Cretaceous bird Eoenantiornis buhleri (Aves: Enantiornithes) from China. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 42:1331-1338.) and Otogornis (Zhou & Hou 2002Zhou Z. & Hou L. 2002. The Discovery and Study of Mesozoic Birds in China. In: Chiappe L.M.& Witmer L.M. (eds.) Mesozoic birds: above the heads of dinosaurs. Berkeley University Press, p. 160-183.), and other derived forms (e.g., Concornis, Halimornis, Martinavis, Elbretornis and Enantiornis; Sanz et al. 1995Sanz J.L., Chiappe, L.M., Buscalioni, A.D. 1995. The osteology of Concornis lacustris (Aves: Enantiornithes) from the Lower Cretaceous of Spain and a reexamination of its phylogenetic relationships. American Museum Novitates, 3133:1-23., Chiappe et al. 2002Chiappe L.M., Lamb J.P., Ericson P.G.P. 2002. New enantiornithine bird from the marine Upper Cretaceous of Alabama. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 22:170-174.; Walker & Dyke 2009Walker C.A. & Dyke G.J. 2009. Euenantiornithine birds from the Late Cretaceous of El Brete (Argentina). Irish Journal of Earth Sciences, 27:15-62.). In this aspect, Cratoavis nov. gen. is reminiscent to that of more basal taxa, such as Iberomesornis and Eocathayornis (Sanz & Bonaparte 1992Sanz J.L. & Bonaparte J.F 1992. A New Order of Birds (Class Aves) from the Lower Cretaceous of Spain. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Contributions in Science, 36:38-49.; Zhou 2002Zhou Z. 2002. A new and primitive enantiornithine bird from the Early Cretaceous of China. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 22:49-57.) in lacking deep capital groove and the transverse ligamental groove.

The ulna is nearly as long as the humerus, a condition that contrast with that of some highly derived Euenantiornithes, such as Elbretornis and Enantiornis, in which the ulna is much shorter than humerus (Walker & Dyke 2009Walker C.A. & Dyke G.J. 2009. Euenantiornithine birds from the Late Cretaceous of El Brete (Argentina). Irish Journal of Earth Sciences, 27:15-62.). The radius shaft appears to the wider proximally than at its distal end, a condition shared with Iberomesornis and Enantiornis (Sereno 2000Sereno P. 2000. Iberomesornis romerali (Aves, Ornithothoraces) reevaluated as an Early Createcous enantiornithean. Neues Jahrbuch fur Geologie und Paleontologie, 215:365-395.; Walker & Dyke 2009Walker C.A. & Dyke G.J. 2009. Euenantiornithine birds from the Late Cretaceous of El Brete (Argentina). Irish Journal of Earth Sciences, 27:15-62.).

Cratoavis nov. gen. manus is subequal to total ulnar length, whereas in Hebeiornis and Eoalulavis the manus is much shorter (see Sanz et al. 2002Sanz J., Pérez-Moreno B., Chiappe L., Buscalioni A. 2002. The birds from the lower Cretaceous of las hoyas (Province of Cuenca, Spain). In: Chiappe, L.M. & Witmer, L.M. (eds.) Mesozoic birds: above the heads of dinosaurs. Berkeley University Press, p. 209-229.; Zhang et al. 2004Zhang F., Ericson G.P., Zhou Z. 2004. Description of a new enantiornithine bird from the Early Cretaceous of Hebei, northern China. Canadian Journal of Earth Science, 41:1097-1107.).

Cratoavis nov. gen. shows a gracile and elongate carpometacarpus, whereas Sinornis, Cathayornis, Houshanornis, Pengornis,Xiangornis, and Bohaiornis show a very robust and wide metacarpal II (Sanz et al. 1995Sanz J.L., Chiappe, L.M., Buscalioni, A.D. 1995. The osteology of Concornis lacustris (Aves: Enantiornithes) from the Lower Cretaceous of Spain and a reexamination of its phylogenetic relationships. American Museum Novitates, 3133:1-23.; Sereno et al. 2002Sereno P., Rao C., Li J. 2002. Sinornis santensis (Aves: Enantiornithes) from the Early Cretaceous of Northeastern China. In: Chiappe L.M.& Witmer L.M. (eds.) Mesozoic birds: above the heads of dinosaurs. Berkeley University Press, p. 184-208.; Zhou et al. 2008Zhou Z., Clarke J., Zhang F. 2008. Insight into diversity, body size and morphological evolution from the largest Early Cretaceous enantiornithine bird. Journal of Anatomy, 212:565-577.; Wang et al. 2010Wang X-R, O'Connor JK, Zhao B, Chiappe LM, Gao C-H, Cheng X-D. 2010. A new species of Enantiornithes (Aves: Ornithothoraces) based on a well-preserved specimen from the Qiaotou Formation of northern Hebei, China. Acta Geologica Sinica, 84(2):247-256.). Furthermore, Gracilornis differs in having strongly bowed metacarpal III (Li & Hou 2011Li L. & Hou S. 2011. Discovery of a new bird (Enantiornithines) from Lower Cretaceous in western Liaoning, China. Journal of Jilin University (Earth Science Edition), 41(3):759-763.).

The gracile coracoid of Cratoavis nov. gen. differs from the more robust and distally expanded coracoid present in Bohaiornis, Shenqiornis, Sulcavis, Xiangornis, Eoalulavis, Enantiophoenyx (Dalla Vecchia & Chiappe 2002Dalla Vecchia F.M. & Chiappe L. 2002. First avian skeleton from the Mesozoic of northern Gondwana. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 22(4):856-860.; Wang et al. 2010Wang X-R, O'Connor JK, Zhao B, Chiappe LM, Gao C-H, Cheng X-D. 2010. A new species of Enantiornithes (Aves: Ornithothoraces) based on a well-preserved specimen from the Qiaotou Formation of northern Hebei, China. Acta Geologica Sinica, 84(2):247-256.; Hu et al. 2011Hu D.-Y, Xu X., Hou L., Sullivan, C. 2011. A new enantiornithine bird from the Lower Cretaceous of Western Liaoning, China, and its implications for early avian evolution. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 32(3):639-645.; O´Connor et al. 2013O'Connor J.K., Zhang Y., Chiappe L.M., Meng Q., Quanguo L., Di L. 2013. A new enantiornithine from the Yixian Formation with the first recognized avian enamel specialization. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 33(1):1-12.), and from the splint-like coracoids of Neuquenornis (Chiappe & Calvo 1994Chiappe L.M. & Calvo J.O. 1994. Neuquenornis volans, a new Late Cretaceous bird (Enantiornithes: Avisauridae) from Patagonia, Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 14:230-246.) and Gobipteryx (Kurochkin 1996Kurochkin E.N. 1996 A new enantiornithid of the Mongolian Late Cretaceous, and a general appraisal of the Infraclass Enantiornithes (Aves). Russian Academy of Science, Special Issue, p. 1-50.).

The femoral head is anterodorsally oriented, and a fovea capitis appears to be absent, in contrast to other enantiornithines (e.g., Martinavis; Walker & Dyke 2009Walker C.A. & Dyke G.J. 2009. Euenantiornithine birds from the Late Cretaceous of El Brete (Argentina). Irish Journal of Earth Sciences, 27:15-62.).

The tarsometatarsus of Cratoavis nov. gen. is very gracile and metatarsals are strongly adpressed to each other. This morphology differs from the stouter tarsometatarsus of Bahiornis, Liaoningornis, Alethoalaornis, Sulcavis, Houshanornis, and Gobipteryx (Li et al. 2009Li L., Hu D., Duan D., Gong E., Hou L. 2009. Alethoalaornithidae fam. nov.: a new family of enantiornithine bird from the Lower Cretaceous of western Liaoning. Acta Palaeontologica Sinica, 46(3):365-372.; Wang et al. 2010Wang X-R, O'Connor JK, Zhao B, Chiappe LM, Gao C-H, Cheng X-D. 2010. A new species of Enantiornithes (Aves: Ornithothoraces) based on a well-preserved specimen from the Qiaotou Formation of northern Hebei, China. Acta Geologica Sinica, 84(2):247-256.; Hu et al. 2011Hu D.-Y, Xu X., Hou L., Sullivan, C. 2011. A new enantiornithine bird from the Lower Cretaceous of Western Liaoning, China, and its implications for early avian evolution. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 32(3):639-645.; O´Connor 2012O'Connor J.K. 2012. A revised look at Liaoningornis longidigitrus (Aves). Vertebrata Palasiatica, 50:25-37.; O´Connor et al. 2013O'Connor J.K., Zhang Y., Chiappe L.M., Meng Q., Quanguo L., Di L. 2013. A new enantiornithine from the Yixian Formation with the first recognized avian enamel specialization. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 33(1):1-12.). Qilania exhibits an extremelly elongate tibiotarsus and tarsometatarsus, which differs from the morphology seen in Cratoavis nov. gen. (Ji et al. 2011Ji S-A., Atterholt J., O'Connor J.K., Lamanna M.C., Harris J.D., Li D-Q, You H-L, Dodson P. 2011. A new, three-dimensionally preserved enantiornithine (Aves: Ornithothoraces) from Gansu Province, China. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 162:201-219.).

Non-ungual phalanges 1-IV and 2-IV are relatively elongate and its combined length clearly surpasses the distal end of phalanx 1-III, whereas in Iberomesornis they do not surpasses such level (Sereno 2000Sereno P. 2000. Iberomesornis romerali (Aves, Ornithothoraces) reevaluated as an Early Createcous enantiornithean. Neues Jahrbuch fur Geologie und Paleontologie, 215:365-395.). Non-ungual phalanges of pedal digit III are very narrow and extremelly elongate, being much longer than metatarsal III. In other Enantiornithes (e.g., Iberomesornis; Sereno 2000Sereno P. 2000. Iberomesornis romerali (Aves, Ornithothoraces) reevaluated as an Early Createcous enantiornithean. Neues Jahrbuch fur Geologie und Paleontologie, 215:365-395.), with the exception of some Bohaiornithidae (Wang et al. 2014Wang M., Zhou Z.-H., O'Connor, J.K., Zelenkov N.V. 2014. A new diverse enantiornithine family (Bohaiornithidae fam. nov.) from the Lower Cretaceous of China with information from two new species. Vertebrata PalAsiatica, 52(1):31-76.) the combined length of these phalanges is subequal or shorter than metatarsal III length.

Cratoavis nov. gen. shows short and robust cervical and dorsal vertebral centra, a condition similar to that of Eoalulavis (Sanz et al. 2002Sanz J., Pérez-Moreno B., Chiappe L., Buscalioni A. 2002. The birds from the lower Cretaceous of las hoyas (Province of Cuenca, Spain). In: Chiappe, L.M. & Witmer, L.M. (eds.) Mesozoic birds: above the heads of dinosaurs. Berkeley University Press, p. 209-229.), which differs from the elongate centra present in Sulcavis, Huoshanornis, Hebeiornis, Cathayornis, and Concornis (Sanz et al. 1995Sanz J.L., Chiappe, L.M., Buscalioni, A.D. 1995. The osteology of Concornis lacustris (Aves: Enantiornithes) from the Lower Cretaceous of Spain and a reexamination of its phylogenetic relationships. American Museum Novitates, 3133:1-23.; Zhang et al. 2004Zhang F., Ericson G.P., Zhou Z. 2004. Description of a new enantiornithine bird from the Early Cretaceous of Hebei, northern China. Canadian Journal of Earth Science, 41:1097-1107.; O´Connor & Dyke 2010O'Connor J.K. & Dyke G.J. 2010. A reassessment of Sinornis santensis and Cathayornis yandica (Aves: Ornithothoraces). In: International Meeting of the Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution, 7, Records of the Australian Museum, 62(1):7-20.; Wang et al. 2010Wang X-R, O'Connor JK, Zhao B, Chiappe LM, Gao C-H, Cheng X-D. 2010. A new species of Enantiornithes (Aves: Ornithothoraces) based on a well-preserved specimen from the Qiaotou Formation of northern Hebei, China. Acta Geologica Sinica, 84(2):247-256.; O´Connor et al. 2013O'Connor J.K., Zhang Y., Chiappe L.M., Meng Q., Quanguo L., Di L. 2013. A new enantiornithine from the Yixian Formation with the first recognized avian enamel specialization. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 33(1):1-12.). Cratoavis nov. gen. shares with Cathayornis, Eoalulavis andSinornis (Zhou & Hou 2002Zhou Z. & Hou L. 2002. The Discovery and Study of Mesozoic Birds in China. In: Chiappe L.M.& Witmer L.M. (eds.) Mesozoic birds: above the heads of dinosaurs. Berkeley University Press, p. 160-183.; Sanz et al. 2002Sanz J., Pérez-Moreno B., Chiappe L., Buscalioni A. 2002. The birds from the lower Cretaceous of las hoyas (Province of Cuenca, Spain). In: Chiappe, L.M. & Witmer, L.M. (eds.) Mesozoic birds: above the heads of dinosaurs. Berkeley University Press, p. 209-229.; Sereno et al. 2002Sereno P., Rao C., Li J. 2002. Sinornis santensis (Aves: Enantiornithes) from the Early Cretaceous of Northeastern China. In: Chiappe L.M.& Witmer L.M. (eds.) Mesozoic birds: above the heads of dinosaurs. Berkeley University Press, p. 184-208.) presence of fan-shaped neural spines of dorsal vertebrae, being different from the rectangular contour seen in remianing enantiornithes.

Distal tail feathers are rather elongate, being 30% longer than total body length. Presence of a pair of elongate distal feathers have been reported for several birds, such as Confusiusornis (Chiappe et al. 1999Chiappe L.M., Ji S., Ji Q., Norell M.A. 1999. Anatomy and systematics of Confusiusornithidae from the late Mesozoic of northeastern China. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 242:1-89.) and in some Enantiornithes (e.g., Protopteryx, Dapingfangornis, Bohaiornis; Zhang & Zhou 2000Zhang F & Zhou Z. 2000. A Primitive Enantiornithine Bird and the Origin of Feathers. Science, 290:1955-1959.; Li et al. 2006Li L., Ye D., Hu D., Wang L., Cheng S., Hou L. 2006. New Eoenantiornithid Bird from the Early Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation of Western Liaoning, China. Acta Geologica Sinica, 80(1):38-41.; Hu et al. 2011Hu D.-Y, Xu X., Hou L., Sullivan, C. 2011. A new enantiornithine bird from the Lower Cretaceous of Western Liaoning, China, and its implications for early avian evolution. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 32(3):639-645.), but in known genera, the rectrices are proportionally much shorter than in Cratoavis nov. gen. No remains of hindlimb feathers are recognized in Cratoavis nov. gen., in contrast with other Enantiornithes, such as Cathayornis and other basal birds, in which they conform a wing-like structure (Zheng et al. 2012Zheng X., Wang X., O'Connor J., Zhou Z. 2012. Insight into the early evolution of the avian sternum from juvenile enantiornithines. Nature Communications, 3:1116-1120.).

Carvalho et al. (2015)Carvalho I.S., Novas F.E., Agnolin F.L., Isasi M.P., Freitas F.I., Andrade J. 2015. A Mesozoic bird from Gondwana preserving feathers. Nature Communications DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8141.

https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8141...

phylogenetic analysis resulted in an unresolved phylogenetic position for Cratoavis nov. gen., and thus, those authors were unable to find a close relative to Cratoavis nov. gen. However, it exhibits some similarities with a handfull of Enantiornithes that are worthy to mention. Cratoavis nov. gen. shares with Pengornis and Eoenantiornis the combination of a globose humeral head that projects further proximally than the deltopectoral crest, a poorly defined capital groove on proximal humerus, and short dorsal vertebral centra (Zhou et al. 2008Zhou Z., Clarke J., Zhang F. 2008. Insight into diversity, body size and morphological evolution from the largest Early Cretaceous enantiornithine bird. Journal of Anatomy, 212:565-577.; Wang et al. 2010Wang X-R, O'Connor JK, Zhao B, Chiappe LM, Gao C-H, Cheng X-D. 2010. A new species of Enantiornithes (Aves: Ornithothoraces) based on a well-preserved specimen from the Qiaotou Formation of northern Hebei, China. Acta Geologica Sinica, 84(2):247-256.). Presence of globose humeral head was also probably present in the poorly known genus Xiangornis. On the basis of the comparisons made above, we conclude that Cratoavis nov. gen. represents a valid genus of Enantiornithes, and can be diagnosed on the basis of a unique combination of characters.

CONCLUSIONS

Cratoaviscearensis nov. gen. et sp. constitutes the first named bird from the Mesozoic of Brazil and the Early Cretaceous of South America. It constitutes an important addition to the meager record of South American Cretaceous birds, and constitutes one of the more complete Mesozoic bird specimen from Gondwana. It also expands the list in which skeletal elements have been found in association with feathers, including long tail rectrices.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The financial support was provided by Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Fundação Coordenação de Projetos Pesquisas e Estudos Tecnológicos (COPPETEC), and Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Técnica, CONICET. We thank Cleuduardo Laurentino Dias, Devânio Ferreira Lima and Antonio Josieudo Pereira Lima that found the specimen and kindly provided it for study. Thanks are also due to Bruno Rafael Santos that produced the illustrations of this study. The photographs were kindly obtained by Daniel Coré Guedes, Claudia Gutterres Vilela and Leonardo Borghi (Geology Department, Rio de Janeiro Federal University).

REFERENCES

- Agnolin F.L. 2010. An avian coracoid from the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina. Studia Geologica Salmanticensia, 46:99-119.

- Agnolin F.L. & Martinelli A.G. 2009. Fossil birds from the Late Cretaceous Los Alamitos Formation, Río Negro province, Patagonia. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 27:42-49.

- Alvarenga H. & Bonaparte J.F. 1992. A new flightless land bird from the Cretaceous of Patagonia. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Science Series, 36:51-64.

- Alvarenga H. & Nava W.R. 2005. Aves Enantiornithes do Cretáceo Superior da Formação Adamantina do Estado de Sao Paulo, Brasil. In: Congreso Latinoamericano de Paleontología de Vertebrados, 2, Rio de Janeiro, Agosto de 2005, p. 20.

- Assine M.L. 1992. Paleocorrentes na bacia do Araripe, Nordeste do Brasil. In: Simpósio sobre as bacias Cretácicas Brasileiras, 2, Rio Claro, São Paulo, Resumos Expandidos, p. 59-60.

- Assine M.L. 2007. Bacia do Araripe. Boletim de Geociências da Petrobras, 15(2):371-389.

- Azevedo R.P., Vasconcellos P.L., Candeiro C.R.A., Bergqvist L.P. 2007. Restos microscopicos de vertebrados fosseis do Grupo Bauru (Neocretaceo), no oeste do Estado de Sao Paulo, Brasil. In: Carvalho I.S., Cassab R.C., Schwanke C., Cavalho M.A., Fernandes A.C., Rodrigues M.A.C., Carvalho M.S., Arai M., Oliveira M.E.Q. (eds.) Paleontologia: Cenários da Vida. Vol. 2. Interciência, p. 541-549.

- Beurlen K. 1963. Geologia e estratigrafia da Chapada do Araripe. In: Congresso Nacional de Geologia, 17 Recife, Recife, Sociedade Brasileira de Geologia, Núcleo Pernambuco, Boletim, 47 p.

- Beurlen K. 1971. As condições ecológicas e faciológicas da Formação Santana na Chapada do Araripe (Nordeste do Brasil). Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 43(suplemento):411-415.

- Brito P.M. & Martill D.M. 1999. Discovery of a juvenile coelacanth in the Lower Cretaceous, Crato Formation, Northeastern Brazil. Cybium, 23:209-211.

- Brocklehurst N., Upchurch P., Mannion P.D., O'Connor J. 2012. The Completeness of the Fossil Record of Mesozoic Birds: Implications for Early Avian Evolution. PLoS ONE, 7(6):e39056.

- Campos D.A. & Kellner A.W.A. 1997. Short note on the first occurrence of Tapejaridae in the Crato Member (Aptian), Santana Formation, Araripe Basin, Northeast Brazil. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 69:83-87.

- Candeiro C.R., Agnolin F.L., Martinelli A.G., Buckup P.A. 2012. First bird remains from the Upper Cretaceous of the Peirópolis site, Minas Gerais state, Brazil. Geodiversitas, 34(3):617-624.

- Carvalho I.S. 2000. Geological environments of dinosaur footprints in the intracratonic basins from Northeast Brazil during South Atlantic opening (Early Cretaceous). Cretaceous Research, 21:255-267.

- Carvalho I.S. 2004. Dinosaur footprints from Northeastern Brazil: taphonomy and environmental setting. Ichnos, 11:311-324.

- Carvalho I.S. & Pedrão E. 1998. Brazilian theropods from the Equatorial Atlantic margin: behavior and environmental setting. Gaia, Lisboa, 15:369-378.

- Carvalho I.S., Novas F.E., Agnolin F.L., Isasi M.P., Freitas F.I., Andrade J. 2015. A Mesozoic bird from Gondwana preserving feathers. Nature Communications DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8141.

» https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8141 - Cavalcanti V.M.M. & Viana M.S.S. 1992. Revisão estratigráfica da Formação Missão Velha, Bacia do Araripe, Nordeste do Brasil. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 64(2):155-168.

- Chiappe L.M. 1993. Enantiornithean (Aves) tarsometatarsi fro the Cretaceous Lecho Formation of Northwestern Argentina. American Museum Novitates 3083:1-27.

- Chiappe L.M. 1996. Early avian evolution in the Southern Hemisphere: the fossil record of birds in the Mesozoic of Gondwana. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, 39:533-554.

- Chiappe L.M. & Calvo J.O. 1994. Neuquenornis volans, a new Late Cretaceous bird (Enantiornithes: Avisauridae) from Patagonia, Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 14:230-246.

- Chiappe L.M. & Lacasa-Ruiz A. 2002. Noguerornis gonzalezi (Aves: Ornithothoraces) from the Early Cretaceous of Spain. In: Chiappe L.M.& Witmer L.M. (eds.) Mesozoic Birds: above the heads of dinosaurs. University of California Press, p. 230-239.

- Chiappe L.M.& Walker C.A. 2002. Skeletal morphology and systematics of Cretaceous Euenantiornithes (Ornithothoraces: Enantiornithes). In: Chiappe L.M.& Witmer L.M (eds.) Mesozoic birds: above the heads of dinosaurs. Berkeley University Press, p. 168-218.

- Chiappe L.M., Ji S., Ji Q., Norell M.A. 1999. Anatomy and systematics of Confusiusornithidae from the late Mesozoic of northeastern China. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 242:1-89.

- Chiappe L.M., Lamb J.P., Ericson P.G.P. 2002. New enantiornithine bird from the marine Upper Cretaceous of Alabama. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 22:170-174.

- Chiappe L.M., Shuan J., Qiang J. 2007. Juvenile birds from the Early Cretaceous of China: Implications for Enantiornithine ontogeny. American Museum Novitates, 3594:1-46.

- Clarke J.A. & Chiappe L.M. 2001. A new Carinate bird from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia (Argentina). American Museum Novitates, 3323:1-23.

- Dalla Vecchia F.M. & Chiappe L. 2002. First avian skeleton from the Mesozoic of northern Gondwana. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 22(4):856-860.

- Frey E., Tischlinger, H., Buchy, M.-C., Martill, D.M. 2003. New specimens of Pterosauria (Reptilia) with soft parts with implications for pterosaurian anatomy and locomotion. In: Buffetaut E. & Mazin J.-M. (eds.) Evolution and Palaeobiology of Pterosaurs. Geological Society of London, Special Publication, 217:233-266.

- Grimaldi D. 1990. Insects from the Santana Formation, Lower Cretaceous, of Brazil. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 195:5-191.

- Heimhofer U., Ariztegui D., Lenniger M, Hesselbo S.P., Martill D.M., Rios-Netto A.M. 2010. Deciphering the depositional environment of the laminated Crato fossil beds (Early Cretaceous, Araripe Basin, North-eastern Brazil). Sedimentology, 57(2):677-694.

- Hu D.-Y, Xu X., Hou L., Sullivan, C. 2011. A new enantiornithine bird from the Lower Cretaceous of Western Liaoning, China, and its implications for early avian evolution. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 32(3):639-645.

- Ji S-A., Atterholt J., O'Connor J.K., Lamanna M.C., Harris J.D., Li D-Q, You H-L, Dodson P. 2011. A new, three-dimensionally preserved enantiornithine (Aves: Ornithothoraces) from Gansu Province, China. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 162:201-219.

- Kellner A.W.A. 2002. A review of avian Mesozoic fossil feathers In: Chiappe L.M.& Witmer L.M. (eds.) Mesozoic Birds: above the heads of dinosaurs. Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 389-404.

- Kellner A.W.A., Maisey J.G., Campos D.A. 1994. Fossil down feather from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil. Palaeontology, 37:489-492.

- Kellner A.W.A., Martins-Neto R.G., Maisey J.G. 1991. Undetermined feather. In: Maisey J.G. (ed.) Santana Fossils, an Illustrated Atlas. Neptune City, NJ: T.F.H. Publications, p. 376-377.

- Kurochkin E.N. 1996 A new enantiornithid of the Mongolian Late Cretaceous, and a general appraisal of the Infraclass Enantiornithes (Aves). Russian Academy of Science, Special Issue, p. 1-50.

- Li L. & Hou S. 2011. Discovery of a new bird (Enantiornithines) from Lower Cretaceous in western Liaoning, China. Journal of Jilin University (Earth Science Edition), 41(3):759-763.

- Li L., Hu D., Duan D., Gong E., Hou L. 2009. Alethoalaornithidae fam. nov.: a new family of enantiornithine bird from the Lower Cretaceous of western Liaoning. Acta Palaeontologica Sinica, 46(3):365-372.

- Li L., Wang J., Zhang X., Hou S. 2012. A New Enantiornithine Bird from the Lower Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation in Jinzhou Area, Western Liaoning Province, China. Acta Geologica Sinica, 86(5):1039-1044.

- Li L., Ye D., Hu D., Wang L., Cheng S., Hou L. 2006. New Eoenantiornithid Bird from the Early Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation of Western Liaoning, China. Acta Geologica Sinica, 80(1):38-41.

- Maisey J. 1991. Santana Fossils: an Illustrated Atlas. Neptune City, NJ: T.F.H. Publications, 459 p.

- Martill D.M. (ed.). 1993. Fossils of the Santana and Crato Formations, Brazil. Field Guides to Fossils, no. 5. London: The Palaeontological Association. Wiley-Blackwell, 160 p.

- Martill D.M. & Filgueira J.B.M. 1994. A new feather from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil. Palaeontology, 37:483-487.

- Martill D.M.& Wilby P.R. 1993. Stratigraphy. In: Martill, D.M. (ed.) Fossils of the Santana and Crato Formations, Brazil. Field Guides to Fossils, 5. London: The Palaeontological Association , p. 20-50.

- Martill D.M., Bechly G., Loveridge R.F. (eds.) 2007. Crato Fossil Beds of Brazil: Window into an Ancient World. Cambridge University Press. 625 p.

- Martins-Neto R.G. & Kellner A.W.A. 1988. Primeiro registro de pena na Formação Santana (Cretáceo Inferior), Bacia do Araripe, nordeste do Brasil. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 60:61-68.

- Medeiros M.A., Lindoso R.M., Mendes I.D., Carvalho I.S. 2014. The Cretaceous (Cenomanian) continental Record of the Laje do Coringa flagstone (Alcântara Formation), northeastern South America. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 53:50-58.

- Menon F. & Martill D.M.2007. Taphonomy and preservation of Crato Formation arthropods. In:, Martill, D.M. Bechly, G., Loveridge, R.F. (eds.) Crato Fossil Beds of Brazil: Window into an Ancient World. Cambridge University Press, p. 79-96.

- Mohr B.A.R., Bernardes-de-Oliveira M.E.C., Loveridge R.F.2007. The macrophyte flora of the Crato Formation. In:, Martill D.M., Bechly G. Loveridge R.F. (eds.) Crato Fossil Beds of Brazil: Window into an Ancient World. Cambridge University Press, p. 537-565.

- Naish D., Martill D.M., Merrick I. 2007. Birds of the Crato Formation. In:, Martill, D.M., Bechly, G. Loveridge, R.F. (eds.) Crato Fossil Beds of Brazil: Window into an Ancient World. Cambridge University Press, p. 525-533.

- Novas F.E., Agnolín F.L., Scanferla C.A. 2010. New enantiornithine bird (Aves, Ornithothoraces) from the Late Cretaceous of NW Argentina. Comptes Rendus Palevol., 9(8):499-503.

- O`Connor J.K. 2009. A systematic review of Enantiornithes (Aves: Ornithothoraces). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Southern California, 600 p.

- O'Connor J.K. 2012. A revised look at Liaoningornis longidigitrus (Aves). Vertebrata Palasiatica, 50:25-37.

- O'Connor J.K. & Dyke G.J. 2010. A reassessment of Sinornis santensis and Cathayornis yandica (Aves: Ornithothoraces). In: International Meeting of the Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution, 7, Records of the Australian Museum, 62(1):7-20.

- O'Connor J.K., Chiappe L.M., Gao K-Q. 2010. A new species of ornithuromorph (Aves: Ornithothoraces) bird from the Jehol Group indicative of higher-level diversity. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology,30(2):311-321.

- O'Connor J.K., Zhou Z-H, Zhang F-C. 2011a. A reappraisal of Boluochia zhengi (Aves: Enantiornithes) and a discussion of intraclade diversity in the Jehol Avifauna, China. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology,9(1):51-63.

- O'Connor J.K., Chiappe L.M., Gao C-L, Zhao B. 2011b. Anatomy of the Early Cretaceous bird Rapaxavis pani (Aves: Enantiornithes). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 56(3):463-475.

- O'Connor J.K., Zhang Y., Chiappe L.M., Meng Q., Quanguo L., Di L. 2013. A new enantiornithine from the Yixian Formation with the first recognized avian enamel specialization. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 33(1):1-12.

- O'Connor J.K., Wang X-R, Chiappe L.M., Gao C-H, Meng Q-J, Cheng X-D., Liu J-Y. 2009. Phylogenetic support for a specialized clade of Cretaceous enantiornithine birds with information from a new species. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 29:188-204.

- Pinheiro F.L., Horn B.L.D., Schultz C.L., Andrade J.A.F.G., Sucerquia P.A. 2012. Fossilized bacteria in a Cretaceous pterosaur headcrest. Lethaia, 45:495-499.

- Ponte F.C. 1992. Origem e evolução das pequenas bacias cretácicas do interior do Nordeste do Brasil. In: Simpósio sobre as Bacias Cretácicas Brasileiras, 2, Rio Claro, São Paulo, Resumos Expandidos, p. 55-58.

- Regali M.S.P. & Santos P.R.S. 1999. Palinoestratigrafia e geocronologia dos sedimentos albo-aptianos das Bacias de Sergipe e Alagoas - Brasil. In: Simpósio sobre o Cretáceo do Brasil, 5, Simpósio sobre el Cretácico de America del Sur, 1, Boletim, p. 411-419.

- Rios-Netto A.M., Regali M.S.P., Carvalho I.S., Freitas F.I. 2012. Palinoestratigrafia do Intervalo Alagoas da Bacia do Araripe, Nordeste do Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Geociências, 42(2):331-342.

- Sanz J.L. & Bonaparte J.F 1992. A New Order of Birds (Class Aves) from the Lower Cretaceous of Spain. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Contributions in Science, 36:38-49.

- Sanz J.L., Chiappe, L.M., Buscalioni, A.D. 1995. The osteology of Concornis lacustris (Aves: Enantiornithes) from the Lower Cretaceous of Spain and a reexamination of its phylogenetic relationships. American Museum Novitates, 3133:1-23.

- Sanz J., Pérez-Moreno B., Chiappe L., Buscalioni A. 2002. The birds from the lower Cretaceous of las hoyas (Province of Cuenca, Spain). In: Chiappe, L.M. & Witmer, L.M. (eds.) Mesozoic birds: above the heads of dinosaurs. Berkeley University Press, p. 209-229.

- Sanz J.L., Chiappe L.M., Pérez-Moreno B.P., Moratalla J.J., Hernandez-Carrasquilla, F., Buscalioni A.D., Ortega F., Poyato-Ariza F.J., Rasskin-Gutman D., Martınez-Delclos, X. 1997. A Nestling Bird from the Lower Cretaceous of Spain: Implications for Avian Skull and Neck Evolution. Science, 276:1543-1546.

- Sereno P. 2000. Iberomesornis romerali (Aves, Ornithothoraces) reevaluated as an Early Createcous enantiornithean. Neues Jahrbuch fur Geologie und Paleontologie, 215:365-395.

- Sereno P., Rao C., Li J. 2002. Sinornis santensis (Aves: Enantiornithes) from the Early Cretaceous of Northeastern China. In: Chiappe L.M.& Witmer L.M. (eds.) Mesozoic birds: above the heads of dinosaurs. Berkeley University Press, p. 184-208.

- Varricchio D.J. & Chiappe L.M. 1995. A new enantiornithine bird from the Upper Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation of Montana. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 15(1):201-204.

- Viana M.S.S. & Neumann, V.H.L. 1999. The Crato Member of the Santana Formation, Ceará State. In: Schobbenhaus C., Campos D.A., Queiroz E.T., Winge M., Berbert B. (eds.) Sitios Geológicos e Paleontológicos do Brasil, p. 1-10.

- Walker C. 1981. New subclass of birds from the Cretaceous of South America. Nature, 292:51-53.

- Walker C.A. & Dyke G.J. 2009. Euenantiornithine birds from the Late Cretaceous of El Brete (Argentina). Irish Journal of Earth Sciences, 27:15-62.

- Wang M., Zhou Z.-H., O'Connor, J.K., Zelenkov N.V. 2014. A new diverse enantiornithine family (Bohaiornithidae fam. nov.) from the Lower Cretaceous of China with information from two new species. Vertebrata PalAsiatica, 52(1):31-76.

- Wang X-R, O'Connor JK, Zhao B, Chiappe LM, Gao C-H, Cheng X-D. 2010. A new species of Enantiornithes (Aves: Ornithothoraces) based on a well-preserved specimen from the Qiaotou Formation of northern Hebei, China. Acta Geologica Sinica, 84(2):247-256.

- Zhang F & Zhou Z. 2000. A Primitive Enantiornithine Bird and the Origin of Feathers. Science, 290:1955-1959.

- Zhang F., Ericson G.P., Zhou Z. 2004. Description of a new enantiornithine bird from the Early Cretaceous of Hebei, northern China. Canadian Journal of Earth Science, 41:1097-1107.

- Zheng X., Wang X., O'Connor J., Zhou Z. 2012. Insight into the early evolution of the avian sternum from juvenile enantiornithines. Nature Communications, 3:1116-1120.

- Zhou Z. 2002. A new and primitive enantiornithine bird from the Early Cretaceous of China. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 22:49-57.

- Zhou Z. & Hou L. 2002. The Discovery and Study of Mesozoic Birds in China. In: Chiappe L.M.& Witmer L.M. (eds.) Mesozoic birds: above the heads of dinosaurs. Berkeley University Press, p. 160-183.

- Zhou Z., Chiappe L.M., Zhang F. 2005. Anatomy of the Early Cretaceous bird Eoenantiornis buhleri (Aves: Enantiornithes) from China. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 42:1331-1338.

- Zhou Z., Clarke J., Zhang F. 2008. Insight into diversity, body size and morphological evolution from the largest Early Cretaceous enantiornithine bird. Journal of Anatomy, 212:565-577.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

Apr-Jun 2015

History

-

Received

18 May 2015 -

Accepted

19 May 2015