Abstract

When a corporation presents a reorganization plan, it expects its creditors to approve the plan. This paper provides empirical evidence regarding the likelihood of approval based on reorganization plans for creditors in Brazil that require approval by employees; and by secure and unsecure debtholders. This paper involves a descriptive analysis of the main characteristics of reorganization plans by type of vote. Using a sample of 120 reorganization plans proposed by corporations from 2005 to 2014, we find that the labor class of creditors is likely to approve the reorganization plan even when the plan is rejected; plans with more heterogeneous payment for classes are less likely to be accepted; plans are less likely to be accepted when there are more unsecure creditors; and plans with divestment proposals are more likely to be accepted. Finally, as expected given the seniority position of secured debt, plans are less likely to be accepted when the portion of secured debt is higher, and the reverse is true for unsecured debt.

Keywords:

Corporate restructuring; Reorganization plan; Bankruptcy

Resumo

Quando uma empresa apresenta um plano de recuperação judicial, espera-se que o plano seja aprovado por seus credores. Neste artigo, apresenta-se a evidência empírica sobre a votação dos credores trabalhistas, com garantia real e quirografário e a probabilidade de aprovação do plano de recuperação judicial no Brasil. O estudo aborda uma análise descritiva das principais características dos planos de recuperação judicial por classe de voto. Utilizando uma amostra de 120 planos de recuperação judicial apresentados por empresas entre 2005 e 2014, os resultados sugerem que: credores trabalhistas estão propensos a aprovar o plano de recuperação mesmo quando o plano é rejeitado pelas demais classes; planos com propostas de pagamento mais heterogêneas para as três classes de credores possuem menor chance de serem aceitos; a chance de aprovação do plano diminui nos casos em que mais credores quirografários participam da votação; e planos com proposta de venda de ativos possuem maior chance de serem aprovados. Finalmente, maior concentração da dívida na classe com garantia real diminui a chance de aprovação do plano, e o contrário ocorre na classe quirografária.

Palavras-chave:

Recuperação de empresas; Plano de recuperação; Falência

Introduction

When a company faces financial distress it may choose to devise a reorganization plan. Such a plan must be presented to its creditors, who ultimately vote to approve the reorganization plan or to subject the company to bankruptcy proceedings. This paper examines this decision making process. We present empirical evidence regarding the approval of reorganization plans, as we believe that a clear gap exists in how each class of creditors decides to approve or reject these plans during the creditors’ general meeting. Collectively, our results show that debtholders’ behavior depends on their claim rights. Moreover, asset disposal facilitates the approval of reorganization plans.

The literature on law and finance states that debt restructuring can be considered a complex decision process involving a firm and its lenders, and stresses that debt reorganization plans and claimholders’ relative recoveries in court depend on how disputes between creditors are resolved (Gilson, Hotchkiss, & Ruback, 2000Gilson, S. C., Hotchkiss, E. S., & Ruback, R. S. (2000). Valuation of bankrupt firms. Review of Financial Studies, 13, 43-74.). Empirical evidence demonstrates the importance of bankruptcy law to the credit market and enforcement by courts.

The interaction between debtors and representative creditors in situations of financial distress has received considerable attention. Kordana and Posner (1999)Kordana, K. A., & Posner, E. A. (1999). A positive theory of Chapter 11. NYU Law Review, 74, 161-234. study bargaining with multiple creditors, incorporating the operation of the voting rules for companies filing Chapter 11. Moreover, Winton (1995)Winton, A. (1995). Costly state verification and multiple investors: The role of seniority. Review of Financial Studies, 8, 91-123., Bolton and Scharfstein (1996)Bolton, P., & Scharfstein, D. (1996). Optimal debt structure with multiple creditors. Journal of Political Economy, 104, 1-25., Bris and Welch (2005)Bris, A., & Welch, I. (2005). The optimal concentration of creditors. Journal of Finance, 60, 2193-2212., Hege and Mella-Barral (2005)Hege, U., & Mella-Barral, P. (2005). Repeated dilution of diffusely held debt. Journal of Business, 78, 737-786., Bisin and Rampini (2006)Bisin, A., & Rampini, A. (2006). Exclusive contracts and the institution of bankruptcy. Economic Theory, 27, 277-304., Hackbart, Hennessy, and Leland (2007)Hackbart, D., Hennessy, C., & Leland, H. (2007). Can the tradeoff theory explain debt structure? Review of Financial Studies, 20, 1389-1428. and von Thadden, Berglöf, and Roland (2010)von Thadden, E., Berglöf, E., & Roland, G. (2010). The design of corporate debt structure and bankruptcy. Review of Financial Studies, 23, 2648-2679. all present multiple-creditor models considering ex ante contracting problems or ex post analysis of those problems stemming from the individual and collective liquidation rights of creditors.

We provide an analysis based on Kaplan and Stromberg (2003)Kaplan, S. N., & Stromberg, P. (2003). Financial contracting theory meets the real world: An empirical analysis of venture capital contracts. Review of Economic Studies, 2003, 281-315. and Kaplan and Strömberg (2004)Kaplan, S. N., & Strömberg, P. (2004). Characteristics, contracts, and actions: Evidence from venture capitalist analyses. Journal of Finance, 59, 2177-2210. using databases suffering from sample bias not present in data from quasi-experiments. Therefore, we do not address causality in our study; this paper provides a descriptive analysis. To our knowledge, there is a lack of empirical explanations of how creditors decide to vote on reorganization plans. Moreover, this is the first study to examine the likelihood of acceptance of reorganization plans by considering the decision process of each class of claimholders and the characteristics of the plans in Brazil. In 2005, Law 11,101 took effect in Brazil with the goal of providing creditors with better conditions for reorganizing or liquidating companies facing financial distress.

As Kordana and Posner (1999)Kordana, K. A., & Posner, E. A. (1999). A positive theory of Chapter 11. NYU Law Review, 74, 161-234. note, little attention has been devoted to the examination of the correspondence between voting rules during reorganizations. von Thadden et al. (2010)von Thadden, E., Berglöf, E., & Roland, G. (2010). The design of corporate debt structure and bankruptcy. Review of Financial Studies, 23, 2648-2679. suggest that many conflicts of interests are solved ex post during the bankruptcy or reorganization period. Hence, our descriptive results provide evidence on the characteristics surrounding creditor's decision making processes.

The literature on reorganization and bankruptcy provides extensive theoretical and empirical analysis of debt restructuring. From an ex ante perspective, studies try to explain the impacts of bankruptcy on firms’ capital structure decisions. Moreover, they try to understand why firms borrow from multiple creditors, although it could make the future resolution of distress more complex. The ex post approach aims to show the best alternatives for sorting out claims in situations where financial distress has already occurred.

Haugen and Senbet (1978)Haugen, R. A., & Senbet, L. W. (1978). The insignificance of bankruptcy costs to the theory of optimal capital structure. Journal of Finance, 33, 383-393. state that bankruptcy risk impacts firms’ capital structure decisions. Similarly, the choice of debt structure influences what occurs in bankruptcy according to Aghion, Hart, and Moore (1992)Aghion, P., Hart, O. D., & Moore, J. (1992). The economics of bankruptcy reform. Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, 8, 523-546.. From an ex ante perspective, several studies analyze the importance of bankruptcy with respect to debtors’ investments, leverage and incentives prior to the bankruptcy situation, such as Cornelli and Felli (1997)Cornelli, F., & Felli, L. (1997). Ex ante efficiency of bankruptcy procedures. European Economic Review, 41, 475-485., Schwartz (1998)Schwartz, A. (1998). A contract theory approach to business bankruptcy. Yale Law Journal, 107, 1806-1851., Berkovitch and Israel (1999)Berkovitch, E., & Israel, R. (1999). Optimal bankruptcy laws across different economic systems. Review of Financial Studies, 12, 347-377., and Bebchuck (2002)Bebchuck, L. (2002). Ex ante costs of violating absolute priority in bankruptcy. Journal of Finance, 57, 445-460. among others. These researchers elucidate the conflict between debtors and representative creditors. Unfortunately, in this paper we cannot control for ex ante variables because the majority of our data do not provide financial statements that allow this.

We present empirical evidence about the characteristics of voting on reorganization plans by separately conducting the analyses according to the outcome of the vote on the plan. Hence, this paper investigates a very important issue from not only a theoretical but also a managerial perspective. We aim to understand how different classes of creditors vote in approving or rejecting recovery plans by controlling for the conditions specified in the reorganization plans. We analyze data collected from 2005 to 2014. We use 2005 as the starting year because the new Brazilian bankruptcy law entered into force in this year.

Under the new Brazilian bankruptcy law, creditors play a more important role in company restructuring because of the new voting procedure for reorganization plans. After choosing to restructure its debt in court, a firm must create a reorganization plan that presents a solution for its financial distress. Unlike Chapter 11 in the US bankruptcy code, Brazilian bankruptcy law does not require a claim administrator to organize and provide information on all claims and claimholders. In the US, indenture trustees act on behalf of creditors: therefore, claimholders do not meet to vote on reorganization plans. Although creditors vote by following a different procedure, Ponticelli (2012)Ponticelli, J. (2012). Court enforcement and firm productivity: Evidence from a bankruptcy reform in Brazil. In Job market paper. Barcelona: University Pompeu Fabra. shows that similarities exist between Brazilian bankruptcy law and the US bankruptcy code and Anapolsky and Woods (2013)Anapolsky, J. M., & Woods, J. F. (2013). Pitfalls in Brazilian bankruptcy law for international bond investors. Journal of Business & Technology Law, 8, 397-450. present more details about the similarities and differences in reorganization rules between the two countries.

When a creditor does not approve the reorganization plan presented by a specific firm, the different classes of creditors decide whether to allow recover or to subject the firm to bankruptcy together in an Assembly, where the labor, secured and unsecured creditors vote on the plan. All three classes of creditors must vote to approve the plan. With regard to secured and unsecured creditors, the plan must be accepted by a majority of creditors at the meeting (number criteria) and at least half of the total debt value for each class must be represented during the vote (value criteria).

By contrast, for labor creditors, only a majority vote is required (number criteria). These two criteria allow firms to avoid opportunistic behavior from creditors, where some creditors might refuse to approve the plan if they do not receive special treatment. If the plan is rejected, the firm enters bankruptcy.

We use data from Vara de Falências e Recuperação Judicial in São Paulo and from firms’ website. Based on data on 120 restructuring plans from 2005 to 2014 we find that the labor class of creditors approves the reorganization plan even when the plan is ultimately rejected. Moreover, we find that approved plans have a smaller portion of debt discounted and higher grace period on average than rejected and modified plans. Further, rejected reorganization plans have higher disparities in payment proposals within the same class of creditors, and reorganization plans that were modified during the creditors’ meeting have higher disparities in payment proposals among the classes of creditors.

To evaluate the likelihood of acceptance of reorganization plans, we run probit regressions. We find that asset disposal increases the likelihood of restructuring plan approval. One possible interpretation of this finding is that collateral is an important determinant of recovery plan acceptance. Creditors seem to generally prefer that firms liquidate a portion of their assets since it facilitates their ability to receive cash. We also find that secured debt creditors have lower incentives than the other classes of creditors to accept reorganization plans; moreover, since they are the last class of creditors to receive payment after liquidation, unsecured creditors are more likely to accept reorganization plans. We also find that high debt values from banks in the junior class are negatively related to plan acceptance and that payment disparities among all classes of creditors seem to reduce the likelihood of acceptance.

This paper is structured as follows: The second section discusses the related literature. The third section describes our data. The fourth section describes the empirical strategy of analysis. The fifth section reports empirical results and a related discussion. The final section concludes the paper.

Related literature

The implementation of a bankruptcy process by law raises some concerns regarding its effects on security prices, default losses, priority rules and financial reorganization. According to Gilson (2012)Gilson, S. C. (2012). Creating value through corporate restructuring: Case studies in bankruptcies, buyouts, and breakups (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.278580

http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.278580...

, academic research on bankruptcy has been concentrated in four main areas: bankruptcy resolution, bankruptcy costs (Haugen & Senbet, 1978Haugen, R. A., & Senbet, L. W. (1978). The insignificance of bankruptcy costs to the theory of optimal capital structure. Journal of Finance, 33, 383-393., 1988Haugen, R. A., & Senbet, L. W. (1988). Bankruptcy and agency costs: Their significance to the theory of optimal capital structure. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 23, 27-38.), governance changes in bankruptcy and the effects of bankruptcy on stock prices (Eberhart, Moore, & Roenfeldt, 1990Eberhart, A. C., Moore, W. T., & Roenfeldt, R. L. (1990). Security pricing and deviations from the absolute priority rule in bankruptcy proceedings. Journal of Finance, 45, 1457-1469.). This research focuses on bankruptcy resolution.

We are interested in understanding creditors’ decision making about the restructuring process. According to Djankov, McLiesh, and Shleifer (2007)Djankov, S., McLiesh, C., & Shleifer, A. (2007). Private credit in 129 countries. Journal of Financial Economics, 84, 299-329. there is a group of papers that connect legal protection for creditors and judicial efficiency. For instance, Claessens and Klapper (2005)Claessens, S., & Klapper, L. (2005). Bankruptcy around the world: Explanations of its relative use. American Law and Economics Review, 7, 253-283. argue that greater judicial efficiency is strongly associated with greater use of bankruptcy, although the combination of stronger creditor rights and greater judicial efficiency leads to less use of bankruptcy.

We would like to highlight the studies that seem to explain why the resolution of financial distress varies across countries. Gennaioli and Rossi (2010)Gennaioli, N., & Rossi, S. (2010). Judicial discretion in corporate bankruptcy. Review of Financial Studies, 23, 4078-4114. show that strong creditor protection increases the efficiency of the resolution of financial distress because it provides judicial incentives.

Based on a sample of 49 countries, La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny (1997)La Porta, R., Lopez-De-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1997). Legal determinants of external finance. Journal of Finance, 52, 1131-1150. find that countries with poor investor protection (legal rules and quality of law enforcement) have smaller and narrower capital markets. To construct a measure of the efficiency of debt enforcement, Djankov, Hart, McLiesh, and Shleifer (2008)Djankov, S., Hart, O., McLiesh, C., & Shleifer, A. (2008). Debt enforcement around the world. Journal of Political Economy, 116, 1105-1149. compare debt enforcement for the same kind of business in 88 different countries. They find that institutions that regulate insolvency usually perform poorly owing to their inefficient bankruptcy procedures.

Penati and Zingales (1997)Penati, A., & Zingales, L. (1997). Efficiency and distribution in financial restructuring: The Case of Ferruzzi Group. In Working paper.. http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/finance/papers/ferfin.pdf (accessed 08.09.13)

http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/finance/...

reveal the importance of understanding the legal environment in which a restructuring process occurs because of its effects on parties’ outside options. For example, the Italian bankruptcy code includes two main procedures (liquidation and reorganization) for addressing an insolvent company. In the case of bankruptcy liquidation, the bankruptcy court appoints a trustee who shuts down the firm and sells its assets (or even sells the whole business). The absolute priority rule then determines how the proceeds of the sale are divided among the claimants (Franks & Torous, 1989Franks, J. R., & Torous, W. N. (1989). An empirical investigation of U.S. firms in reorganization. Journal of Finance, 44, 747-770., 1994Franks, J. R., & Torous, W. N. (1994). A comparison of financial recontracting in distressed exchanges and chapter 11 reorganizations. Journal of Financial Economics, 35, 349-370.).

Since we focus on the reorganization process for distressed firms, it is important to examine guidance provided regarding the power of law. In this regard, Platt and Platt (2008)Platt, H., & Platt, M. (2008). Financial distress comparison across three global regions. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 1, 129-162. examine factors that seem to predict financial distress in the US, Europe and Asia: they find that differences in accounting rules, legal practices, environmental laws and business practices between regions may limit the degree of convergence in the area of financial distress. Indeed, bankruptcy law varies considerably around the world.

Several studies have examined the main characteristics of restructuring processes around the world. According to Franks, Nyborg, and Torous (1996)Franks, J. R., Nyborg, K. G., & Torous, W. N. (1996). A comparison of US, UK, and German insolvency codes. Financial Management, 25, 86-101. and Hotchkiss et al. (2008)Hotchkiss, E. S., John, K., Mooradian, R., & Thorburn, K. S. (2008). Bankruptcy and the resolution of financial distress. In Working paper.. Available at http://mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu/Pages/Faculty/Karin.Thorburn/publications/Ch14-N53090.pdf

http://mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu/Pages/Facu...

, who specifically focus on the restructuring of distressed firms in the UK, Sweden, France, Germany and Japan, the degree to which companies’ business is protected from creditors also varies considerably.

In studying the primary effects of the new Brazilian bankruptcy law, Araujo and Funchal (2009)Araujo, A. P., & Funchal, B. (2009). Lei de Falências Brasileira, A.N. Primeiros Impactos. Journal of Political Economy, 29, 191-212. find that the new law has had a rapid and strong impact on the number of bankruptcies in Brazil. According to these authors, expansion of the credit market is observable. Moreover, Kadiyala (2011)Kadiyala, P. (2011). Impact of bankruptcy law reform on capital markets in Brazil. Investment Management & Financial Innovations, 8, 31-41. investigates the impact of bankruptcy law reform on capital markets in Brazil and, based on an empirical analysis of four different stock indexes (Bovespa, IBX, IGCX and ITAG), shows that aggregate stock market indexes reacted positively by the time that new rules were signed into law. These results are consistent with those of La Porta et al. (1997)La Porta, R., Lopez-De-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1997). Legal determinants of external finance. Journal of Finance, 52, 1131-1150., who find that better bankruptcy laws lead to increased equity values.

Following Quian and Straham's (2007)Qian, J., & Strahan, P. E. (2007). How laws and institutions shape financial contracts: The case of bank loans. Journal of Finance, 62, 2803-2834. argument that the quality of the legal environment shapes the characteristics and terms of bank loans around the world, Araujo, Ferreira, and Funchal (2012)Araujo, A. P., Ferreira, R. V. X., & Funchal, B. (2012). The Brazilian bankruptcy law experience. Journal of Corporate Finance, 18, 994-1004. evaluate the empirical consequences of the bankruptcy reform on credit markets by using a quasi-experimental approach to compare Brazilian firms with non-Brazilian firms (companies from Argentina, Chile and Mexico). The result shows that increased protection is responsible for both an increase in the amount of long-term debt and a reduction in the cost of capital.

Funchal and Clovis (2009)Funchal, B., & Clovis, M. (2009). Firms’ capital structure and bankruptcy law design. Journal of Financial Economic Policy, 3, 264-275. study firms’ capital structure and bankruptcy law design to examine the effect of changes in priorities among creditors and find a significant impact on firm's financial policy in line with lower costs of capital.

Exploiting the quality of court enforcement across Brazilian judicial districts, Ponticelli (2012)Ponticelli, J. (2012). Court enforcement and firm productivity: Evidence from a bankruptcy reform in Brazil. In Job market paper. Barcelona: University Pompeu Fabra. shows that efficient court enforcement helps sustain higher capital investment and productivity for companies. Thus, firms that face better court enforcement benefit in terms of access to external financing, investment and productivity.

Moreover, De Assis (2012)De Assis, D. V. X. D. (2012). Uma Análise Empírica sobre o Processo de Recuperação Econômica pela via judicial adotado pelas sociedades empresárias. Dissertação de Mestrado – Fundação Getulio Vargas, Direito/Rio, Rio de Janeiro. present an interesting study focused on analyzing judicial recovery proceedings immediately following the implementation of the new bankruptcy law. This paper provides some analysis of restructuring plans and shows that the average time to complete all stages of the proceedings exceeds a reasonable amount of time. Our paper must corroborate previous work since it intends to present and analyze information provided in reorganization plans.

Analysis of the approval of reorganization plans

Under the new Brazilian bankruptcy law, court-based restructuring permits different means of restructuring, such as a potential change in corporate control, the stipulation of special terms and conditions for payments of obligations, and the right of veto for creditors regarding restructuring plans. The results regarding the new Brazilian bankruptcy law show that many companies have chosen to adopt a restructuring plan in order to address their financial problems. Moreover, the total number of restructuring cases has increased in each year after the new law entered into force. Until 2005, bankruptcy in Brazil was ruled by Law 7661.

Law 7661 did not offer conditions for the recovery of economically viable companies that faced financial distress. The old reorganization procedure (known as concordata) only postponed corporate debt. Moreover, as the main shortcomings of the previous system, the liquidation process was characterized by extensive bureaucracy, optimal recovery could generally not be achieved in situations of distress, and firms faced difficulties in obtaining new debt to restructure their business. Moreover, the insolvency process did not effectively protect credit rights after liquidation.

According to Funchal (2006)Funchal, B. (2006). Essays on Credit and Bankruptcy Law. In Tese (Doutorado). Rio de Janeiro, FGV: EPGE – Fundação Getulio Vargas., creditors play a more significant role in the restructuring procedure under the new Brazilian bankruptcy law because they are involved in the negotiation and voting on the reorganization plan. Despite the improvements of the new law, it complicates the process of resolving firms’ debts by forcing heterogeneous creditors to vote together (Funchal, 2006Funchal, B. (2006). Essays on Credit and Bankruptcy Law. In Tese (Doutorado). Rio de Janeiro, FGV: EPGE – Fundação Getulio Vargas.). As noted earlier, all three classes of creditors must vote to approve the final plan. However, Brown (1989)Brown, D. T. (1989). Claimholder incentive conflicts in reorganization: The role of bankruptcy law. Review of Financial Studies, 2, 109-123. finds that heterogeneous groups of creditors are more concerned with receiving guarantees, whereas homogenous creditors are primarily concerned with participating in the restructuring process.

Reorganization plans must be approved at the creditors’ meeting, where creditors are divided into three classes for their vote. It is important to highlight that tax creditors and creditors holding loans supported by fiduciary alienation of assets are not subject to recovery: therefore, they do not vote on reorganization plans.

Secured creditors vote as a class and represent an amount up to the value of their collateral. Moreover, when creditors demand more than their collateral value, they can vote as both secured and unsecured creditors, and they then represent exactly the same amount they own for each category. Debtors can indicate the period that they believe to be reasonable by which to pay their secured and unsecured creditors. However, according to article 54 of Law 11.101/2005, debtors cannot stipulate a period greater than one year for labor debt in their restructuring plan.

Once a company has decided to undergo court restructuring, the process by which creditors’ acceptance or rejection of the reorganization plan proceeds through the following steps:

-

The firm must present the reorganization plan in court within sixty days after deciding to undergo a restructuring process;

-

The judge communicates that the recovery plan has been received and sets a deadline for creditors to present any objection;

-

Labor, secured and unsecured creditors (or, potentially, only one or two classes) vote on the reorganization plan to accept, reject or postpone it in order to demand of additional changes. All the three classes of creditors must vote to approve the plan for it to be approved; otherwise, the firm undergoes bankruptcy.

Further, the bankruptcy law establishes the following order of debt priority when a firm opts for bankruptcy or when its restructuring plan is rejected in the creditors’ meeting:

-

Labor debt up to the limit of 150 minimum wages per worker;

-

Secured debt up to the limit of the collateral;

-

Tax debt;

-

Payment for debtholders with specific and general privileges;

-

Unsecured debt.

Data description

We use data from different sources to create our sample. First, we collected some court restructuring plans from “Vara de Falências e Recuperação Judicial” in São Paulo, we then obtained a wide variety of restructuring plans from Google® since the data are public and usually available on the websites of firms and judicial trustees. We consider information from both private and public companies’ restructuring plans.

Our sample includes 120 firms for which we have information about labor, secured and unsecured funding from banks and nonbank creditors. Since 2005, there have been only a few restructuring process for public companies: therefore, the main part of our sample comprises private firms. We collected data from 3 different documents on firms’ reorganization processes, and we analyzed the reorganization plan itself, the minutes from the creditors’ meeting and the relation of each creditor that presents a description of the amount of money to be recovered. As Table 1 shows, our sample is more concentrated in the industrial and noncyclical sectors and less concentrated in the basic materials sector.

Table 2 summarizes the basic statistics for each variable collected from the documents mentioned above. The definitions of the variables are also provided in the notes to the table. As shown, firms’ average age (from birth to the restructuring date) is approximately 31 years.

Regarding the number of banks, the statistics show that approximately seven banks are involved in the restructuring process per firm.

Sample selection issues

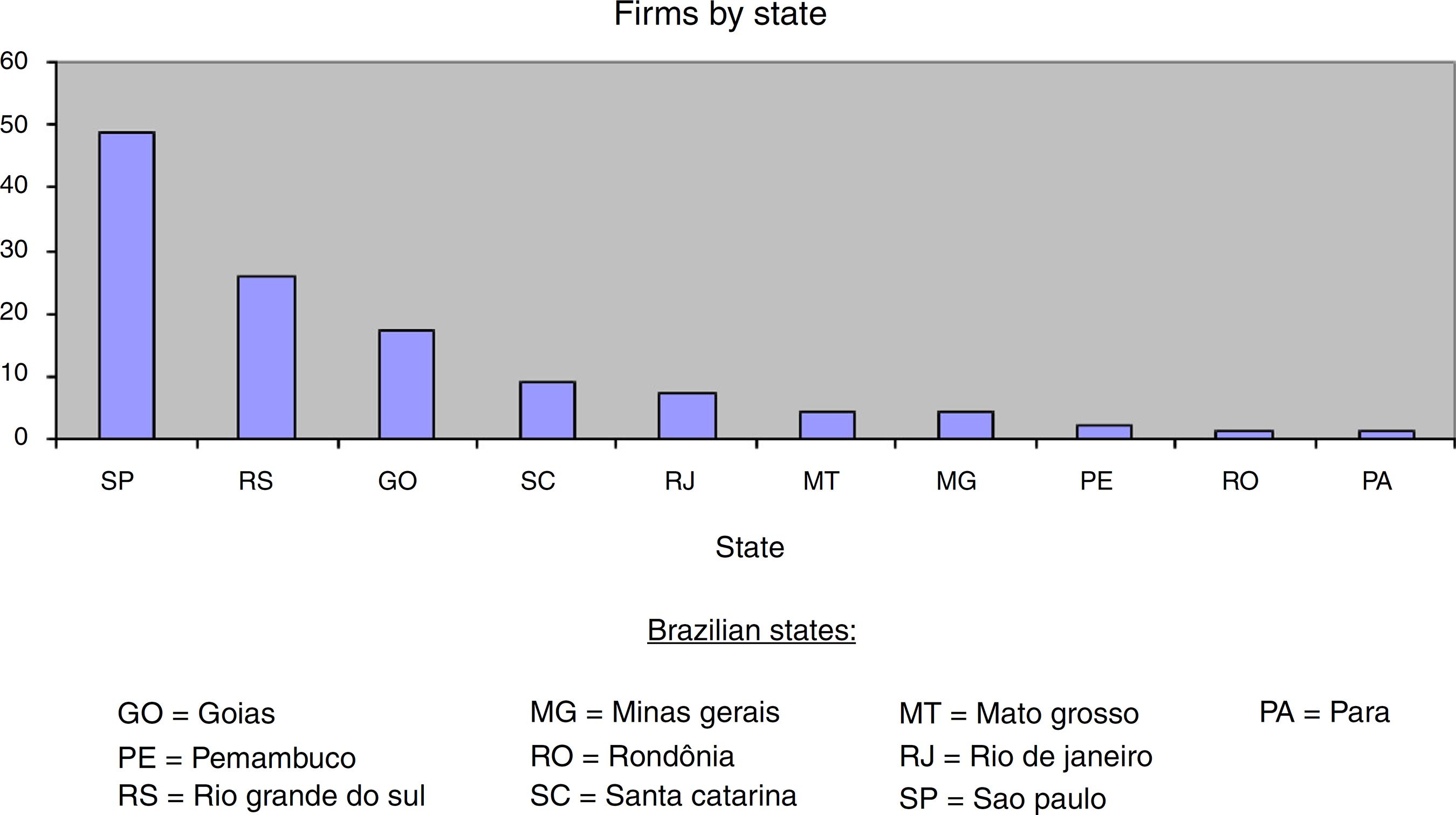

The data in our sample were not provided by a quasi-experiment. Since we collected our data by searching for information provided on the websites of firms, lawyers and judge trustees, our sample may present some kind of bias. Because we have a nonrandom sample, we can only analyze the possible direction of the bias rather than completely eliminate it. One possible type of bias may be related to the region as we have a higher concentration of firms in the south and southeast and only a few firms in the north and northeast.

However, this distribution of firms is in line with the populations of the judicial districts in Brazil. The State of São Paulo has the higher number of civil courts. Further, in his analysis of judicial districts in Brazil, Ponticelli (2012)Ponticelli, J. (2012). Court enforcement and firm productivity: Evidence from a bankruptcy reform in Brazil. In Job market paper. Barcelona: University Pompeu Fabra. finds that the country is divided into 2738 judicial districts, with a higher concentration of judicial districts and courts dealing with bankruptcy in southeast and a higher concentration of companies in the south and southeast of Brazil. The characteristics of our sample are in line with these characteristics. Fig. 1 shows the portion of firms in our sample by state.

Ponticelli (2012)Ponticelli, J. (2012). Court enforcement and firm productivity: Evidence from a bankruptcy reform in Brazil. In Job market paper. Barcelona: University Pompeu Fabra. noted that the State of São Paulo has a concentration of civil courts, which is consistent with our sample because a greater number of observations were obtained from the southeast, which had more than 10 different courts in São Paulo alone. Ponticelli also showed that court concentration in the southeast is worse than in other regions and indicated that companies in Brazil are extremely concentrated in the south and southeast. We do not believe that such characteristics can completely eliminate a bias toward this region; however, we are confident that our data follow the characteristics of recovery in Brazil as a whole.

Moreover, Brazilian judicial trustees are appointed by the court, but a specific lawyer may receive more complicated cases based on his reputation or knowledge about bankruptcy situations. Fortunately, we can check the minutes of the Assembly to determine whether a lawyer represented the recovering firm or a judicial trustee was in charge of the case. With such information, we can determine whether there is a pattern related to lawyers in our sample data. Our cases are spread out among different lawyers, which reduces the possibility that a specific lawyer is driving our result. Although we have shown the characteristics of our data to analyze the potential for bias in our data we cannot make definitive conclusions since we do not have a random sample. We are quite confident that any bias in our sample is related the concentration of cases handled by lawyers and belonging to particular regions.

Empirical strategy of analysis

This paper involves both a descriptive and an econometric analysis of the main characteristics of reorganization plans by type of vote. It is important to highlight that we do not intend to identify a causal relation between the variables since we are not conducting a controlled experiment provided by an exogenous shock. We provide an initial analysis of reorganization plans by type of vote, and we then conduct an econometric analysis to calculate controlled correlations between the independent variables and the likelihood that creditors initially accept the plan (i.e., without modification).

Descriptive analysis

This part of the paper aims to provide empirical evidence of the characteristics of the reorganization plans by separating the reorganization plans according to the Assembly results. Specifically, since plans can be approved, modified or rejected, we decided to capture the characteristics of each plan and compare them according to the possible results of the Assembly. We further conduct a descriptive analysis on the proposal that debtors presented to claimholders regarding payment. This part of the analysis examines the portion of debt discounted from the original debt value, the grace period suggested by debtors to postpone the first payment and the correction form of the debt payment provided during the reorganization period.

We also perform a descriptive analysis of disparities in payment proposals among creditors.

Econometric regressions

To identify which kind of outcome one can expect for a restructuring plan, we decided to adopt a probit regression. Since the readers of this paper likely come from different areas of knowledge, we provide a brief description related to our empirical model.

Our variable of interest is a dichotomous dependent variable (creditors must approve or reject the reorganization plan). Therefore, our dependent variable is a nominal scale variable, taking values of 1 for approved plans and 0 otherwise. A researcher can choose among several techniques to run a regression when the dependent variable is binary, such as the Linear Probability Model (LPM), the Logit Model or the Probit Model.

The LPM assumes that the probability of the dependent variable (to approve the plan, in this case) moves linearly with the value of the explanatory variables. Moreover, there is no guarantee that the estimated value in the LPM model will lie between 0 and 1. Hence, logit and probit models are the preferred choice for modeling our decision making process since they fit a nonlinear function to the data and guarantee that the estimated probabilities will lie between 0 and 1. These two models generally present similar results. The logit model considers the cumulative distribution function of the logistic distribution, while the probit model considers the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution. Logit models are usually applied when researchers want to interpret coefficients of the regression in terms of odds ratios (which is not our case). Logit models present slightly fatter tails and their conditional probability of rejecting or approving the reorganization plan approaches 0 or 1 at a slower rate compared to probit models. Therefore, we choose the probit model in our study.

Our model aims to determine the likelihood that a firms’ restructuring plan is accepted when creditors do not demand additional changes. Therefore, we do not separate plans that were approved, modified or rejected in our econometric analysis in order to run a multinomial probit regression. Modified plans have many of modifications from a specific group of creditors that define conditions for approving the plan. Hence, modified plans were first rejected by creditors before being modified. We decided to capture the likelihood that a firms’ restructuring plan is accepted without additional changes. Therefore, our research question is as follows: What are the main determinants of reorganization plan acceptance for each class of creditors? At a first glance, we would like to evaluate the factors that affect creditors’ decision about the reorganization plan. How do heterogeneous creditors behave in the decision process for reorganization plans? Does the decision to accept reorganization plans lie with banks? Does it concern specifying collateral?

Giambona et al. (2013)Giambona, E., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Matta, R. (2013). Improved creditor protection and verifiability in the U.S. In Working paper.. https://editorialexpress.com/cgi-bin/conference/download.cgi?db_name=sbe35&paper id=22 (Accessed 23.08.14)

https://editorialexpress.com/cgi-bin/con...

argue that because there are different classes of debt, reorganization plans are often rejected in Chapter 11 proceedings. Previous works have also stressed that the allocation of resources to different claimholders that is specified in a recovery plan is as important as the potential value that the restructuring will engender. Further, Brown (1989)Brown, D. T. (1989). Claimholder incentive conflicts in reorganization: The role of bankruptcy law. Review of Financial Studies, 2, 109-123. argues that problems can rise in the presence of heterogeneous creditors.

Following these studies, we evaluate the likelihood of approval according to the categories of creditors. Accordingly, as explanatory variables in our regressions we adopt the ratio of each debt category to the total debt and the number of creditors.

Concerning the restructuring process, Senbet and Wang (2010)Senbet, L. W., & Wang, T. Y. (2010). Corporate financial distress and bankruptcy: A survey. Finance, 5, 243-335. state that creditors generally prefer asset liquidation, since such a procedure facilitates their ability to receive cash. In our empirical model, we examine the effect of asset disposal when a collateral asset for debt payment is specified in the reorganization plan.

For this purpose, we run regressions with labor, secured and unsecured debt as the explanatory variables and we model each regression while controlling for a group of variables that each category of creditors should consider in voting on the reorganization plan.

In addition to the amount of debt from heterogeneous creditors mentioned above, we also consider the amount of secured and unsecured bank loans with claims at the creditors’ meeting as a control measure. There is no consensus based on empirical evidence about the role of banks in the approval of reorganization plans. According to Gilson (1990)Gilson, S. (1990). Bankruptcy, boards, banks, and blockholders: evidence on changes in corporate ownership and control when firms default. Journal of Financial Economics, 27, 315-353., Brown (1989)Brown, D. T. (1989). Claimholder incentive conflicts in reorganization: The role of bankruptcy law. Review of Financial Studies, 2, 109-123. and James (1996)James, C. (1996). Bank debt restructurings and the composition of exchange offers in financial distress. Journal of Finance, 51, 711-727., banks help reduce holdout and information problems in private restructuring. However, Helwege (1999)Helwege, J. (1999). How long do junk bonds spend in default? Journal of Finance, 54, 341-357. argues that bank debt is related to a slower debt restructuring process. Although we cannot specify the expected sign for bank debt in our empirical investigation, bank debt nevertheless seems to be necessary to include as a control variable in our regressions.

Finally, we also control for the period of time stated by the firms by which to settle their debt, the type of firm, disparities in payment proposals among creditors and modifications in corporate ownership. Since the reorganization plan is made before creditors vote, all explanatory variables are specified for the period before the acceptance, requested modification or rejection of the plan.

Our first empirical model is designed for labor creditors. As specified earlier, such creditors are the first category of creditors to receive any amount of money if a plan is rejected. According to law, this category of creditors must receive payment from debtors within a one-year period. Hence, we do not need to run a regression that controls for the period of time stated by the firm to pay its debtholders for this group of creditors. Since we include many of the same variables in subsequent equations below, we avoid repeating the definition of each variable for all the equations. Therefore, for each equation, we repeat the definition for the dependent variable and provide the definitions for the control variables that were not mentioned for previous equations.

We run a regression with both the portion of debt and number of creditors as explanatory variables for the classes of creditors. Our first equation is specified as follows:

Yt = Pr(Y = 1/X) = dummy variable that equals 1 if the reorganization plan is accepted without changes and 0 if it is either accepted with modifications suggested by the creditors or rejected.

Labor (%) = ratio of labor debt to total debt. The variable Labor is the first class of the firm's debt.

Labor (#) = this is the number (quantity) of labor debtholders.

Type = dummy variable that equals 1 for corporations (S.A firms).

Asset_Disposal = dummy variable that equals 1 if the firm chooses a collateral asset for debt payment in the restructuring plan.

Total_Debt(ln) = the variable is measured as the logarithm of the firm's total debt.

Diff_Classes = dummy variable that equals 1 for disparities in the payment proposals among the three classes of claimholders.

Ownership_Reorg = dummy variable that equals 1 for changes in corporate control.

In the first equation, we are interested in the sign of the variables labor and asset disposal. It is difficult to determine how labor creditors should behave with respect to reorganization plans, since there are no observable conditions for which to control in the plan analysis, such as employment.

Labor creditors are the first category of creditors to receive payment in the case of bankruptcy: therefore, they have incentives to reject the plan when creditors are perceived to have an advantage. Nevertheless, if workers believe in their firm and if they fear that they may face problems when returning to the labor market, they have incentives to approve the plan. In this equation, we expect only asset disposal to have a positive sign owing to the guarantee of cash, as noted in Senbet and Wang (2010)Senbet, L. W., & Wang, T. Y. (2010). Corporate financial distress and bankruptcy: A survey. Finance, 5, 243-335. and Giambona et al. (2013)Giambona, E., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Matta, R. (2013). Improved creditor protection and verifiability in the U.S. In Working paper.. https://editorialexpress.com/cgi-bin/conference/download.cgi?db_name=sbe35&paper id=22 (Accessed 23.08.14)

https://editorialexpress.com/cgi-bin/con...

.

According to Brown, James, and Mooradian (1994)Brown, D. T., James, C. M., & Mooradian, R. M. (1994). Asset sales by financially distressed firms. Journal of Corporate Finance, 1, 233-257., evidence indicates that asset sales benefit creditors more than equityholders in cases of distress. Moreover, Asquith, Gertner, and Scharfstein (1994)Asquith, P., Gertner, R., & Scharfstein, D. (1994). Anatomy of financial distress: An examination of junk-bond issuers. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109, 625-658. show that asset sales represent an important means for firms to avoid bankruptcy. The null hypothesis of our equations is that none of the variables mentioned below influences the acceptance of the restructuring plan. Based on previous works, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis H1. Asset disposal may influence creditors to accept the reorganization plan. Therefore, we expect to find a positive sign for asset disposal in our regressions (β > 0).

Hypothesis H1 must hold for all regressions in this paper. With regard to secured creditors, we believe that our task is easier. Eq. (2) is specified as follows:

yt = Pr(Y = 1/X) = dummy variable that equals 1 if the reorganization plan is accepted without changes and 0 if it is either accepted with modifications suggested by creditors or rejected.

Secured (%) = ratio of secured debt to total debt.

Secured (#) = this is the number (quantity) of secure debtholders.

SBL = variable that specifies the portion of bank loans that constitute secured debt.

Dif_Same_Class = dummy variable that equals 1 for disparities in payment proposals within the same class of claimholders.

P = the variable Payment_years is the period of time stated by the firm to settle its debt.

Secured creditors own assets as collateral and receive payment after labor debtors in the case of bankruptcy. Therefore, we believe that this category of creditors also has incentives to reject the reorganization plan. According to Brouwer (2006)Brouwer, M. (2006). Reorganization in US and European bankruptcy law. European Journal of Law and Economics, 22, 5-20., some countries attempt to attenuate the conflict that arises from secured creditors’ right to claim their collateral by applying an automatic stay. However, such a measure may not be sufficient to convince creditors to accept the reorganization plan. In addition to the control variables included in the first equation, we added two more variables related to secured creditors’ decision to accept the plan. For this kind of creditor, we believe that the period of time stated by a firm to settle its debt and the amount of secured bank loans can influence the likelihood that the restructuring plan is accepted.

Therefore, we specify our second hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis H2. Secured creditors have incentives to reject the reorganization plan. Therefore, we expect to find a negative sign for the coefficient of this variable (β < 0).

Finally, we analyze the same decision with respect to unsecured creditors. As these creditors are the last group of creditors to receive any value from liquidation, they have incentives to accept the reorganization plan. The incentives of this class of creditors are clearly more aligned with shareholders than those of the other classes. Junior creditors are out of the money in most cases, and the decision to continue the business (even if it is inefficient) can provide an upside for this class according to Gertner and Scharfstein (1991)Gertner, R., & Scharfstein, D. (1991). A theory of workouts and the effects of reorganization law. Journal of Finance, 46, 1189-1222.. Focusing on unsecured creditors, Eq. (3) is specified as follows:

yt = Pr(Y = 1/X) = dummy variable that equals 1 if the reorganization plan is accepted without changes and 0 if it is either accepted with modifications suggested by creditors or rejected.

Unsecured(%) = ratio of unsecured debt to total debt.

Unsecured (#) = this is the number (quantity) of unsecure debtholders.

UBL = unsecured bank loan indicates the portion of bank loans that constitute unsecured debt.

We impose the same modification in Eq. (3) regarding the separation of the value and number criteria specified for the previous equations. We present our third hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis H3. Unsecured creditors have incentives to approve the reorganization plan. Therefore, we expect to find a positive sign for the coefficient of this variable (β > 0).

Empirical results and discussion

This section reports the empirical results from our descriptive and econometric analyses. Fig. 2 shows the portion of firms in the sample per year.

We have more reorganization cases in 2012, 2009, 2013 and 201, respectively. The sample shows only a few cases in 2014 because we stopped collecting data in the middle of the year.

Table 3 presents results regarding the quorum of creditors who voted on the plan during the creditors’ general meeting. For approved plans without modifications, the results reveal that more secured creditors were present to vote on the plan than labor and unsecured creditors. However, the rate of acceptance is higher among labor creditors than among the other classes. The results for the modified plans are similar.

Furthermore, the number of no shows at the vote is higher among unsecured creditors for approved plans, yet for modified and rejected plans, the number of no shows among labor creditors is similar to that among unsecured creditors.

The analysis of rejected plans is interesting. Secured creditors show the highest portion of rejections, while labor creditors rejected the plan in only 10.42% (mean) of the cases in the sample. In fact, when the plan was initially accepted the lowest portion of labor creditors to accept the plan is 96%. Thus, labor creditors approved the plan in most of the cases, even when the other classes decided to reject it.

Table 4 shows the proposal of payment to claimholders according to the outcome of the vote in the Assembly. The average portion of debt discounted is higher for rejected plans, while the average grace period (13.11 months) is higher for modified plans.

Table 4, part B, also reveals that inflation indexes were used as the main strategy for correcting debt payments for rejected plans, while floating interest rates were the main strategy used in the other cases.

Regarding the disparities in payment proposals, Table 5 shows that plans approved with no modifications are more homogenous among claimholders. Moreover, modified plans show the greatest disparities in payment proposals among classes, whereas rejected plans show the greatest disparities in payment proposals within the same class of creditors.

As shown for our first probit, regression in Table 6, the coefficient for the variable Asset_Disposal is positive and significant. The interpretation of this result is quite simple, since having a greater amount of collateral for debt increases the likelihood that the restructuring plan will be accepted. Claimholders vote on the plan within an environment of uncertainty: therefore, it benefits all creditors to associate an asset with collateral. This result thus seems to confirm that creditors generally prefer to liquidate a portion of the firm's assets, since such a procedure facilitates their ability to receive cash. This finding supports the first hypothesis of our study.

The difference among classes is significant when year fixed effects are taken into account. However, we did not find significant coefficients for the remaining variables.

The empirical results for the second equation are presented in Table 7. As shown, the relationship between the portion of secured credit debt and the likelihood of acceptance is significant and negative. This result is in agreement with Senbet and Wang (2010)Senbet, L. W., & Wang, T. Y. (2010). Corporate financial distress and bankruptcy: A survey. Finance, 5, 243-335. and Giambona et al. (2013)Giambona, E., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Matta, R. (2013). Improved creditor protection and verifiability in the U.S. In Working paper.. https://editorialexpress.com/cgi-bin/conference/download.cgi?db_name=sbe35&paper id=22 (Accessed 23.08.14)

https://editorialexpress.com/cgi-bin/con...

.

As mentioned earlier, secured creditors seem to have incentives to liquidate a company and to get their money back. In addition to secured debt, asset disposal and disparities in payment proposals among the classes are significant in the regression. The sign for asset disposal remains positive sign and disparities in payment proposals among classes shows a negative sign. Regarding payment_years, one could expect a negative sign in the regression because it represents the period of time stated by the firms to settle their debt: therefore, a shorter period is better for claimholders. However, the coefficient is not statistically significant.

The coefficient of the variable secured bank loan is not statistically significant. As explained earlier, this variable could show either a positive or a negative sign.

Table 8 presents the same analysis for Eq. (3), where we focus on the role of unsecured creditors.

As shown, the variable unsecured, measured as a portion of unsecured debt to total debt, is positively related to the likelihood that the reorganization plan is accepted without modifications. This result supports the third hypothesis of this paper. One can also see that the coefficient for the number of unsecured creditors has a negative sign.

Increasing the number of creditors involved in the vote on a reorganization plan can engender more coordination problems, and our results support such a statement. As explained earlier, unsecured creditors have incentives to approve the restructuring plan, since they receive payment after other creditors. The coefficient for the variable asset disposal remains positive and significant. Further, the coefficient for the difference among classes remains significant in the same direction. Since higher levels of debt distance creditors from at-the-money positions in the case of liquidation, we believe that the direction of the sign is accurate.

In Tables 6–8, we investigate the likelihood that reorganization plans are accepted when firms present them to claimholders during the creditors’ general meeting. We find evidence that more heterogeneous proposals among classes of claimholders reduces the likelihood of plan acceptance. Several complications may appear in situations where multiple creditors have different interests and receive different contracts from the firm. These issues have received considerable attention from theoretical studies, such as Kordana and Posner (1999)Kordana, K. A., & Posner, E. A. (1999). A positive theory of Chapter 11. NYU Law Review, 74, 161-234., Bris and Welch (2005)Bris, A., & Welch, I. (2005). The optimal concentration of creditors. Journal of Finance, 60, 2193-2212. and von Thadden et al. (2010)von Thadden, E., Berglöf, E., & Roland, G. (2010). The design of corporate debt structure and bankruptcy. Review of Financial Studies, 23, 2648-2679.. Different interests and heterogeneous proposals can lead to a rejection of the reorganization plan even when it appears to be good for the company as a whole. Thus, our results are in line with the previous literature.

A higher portion of unsecured claims increases the likelihood of plan acceptance. However, reorganization plans are less likely to be approved in cases of a greater number of unsecured creditors. A higher concentration of debt in the hands of secured creditors reduces the chances of plan acceptance. Gertner and Scharfstein (1991)Gertner, R., & Scharfstein, D. (1991). A theory of workouts and the effects of reorganization law. Journal of Finance, 46, 1189-1222. explain that the incentives of unsecured creditors are more clearly aligned with shareholders than those of the other classes. Junior creditors are out of the money in most cases, and the decision to continue the business (even if it is inefficient) can provide an upside for this class. Therefore, they have incentives to approve the reorganization plan. Nevertheless, secured creditors have incentives to receive cash in accordance to their collateral level as quickly as possible. They might search for better investment opportunities instead of waiting for the distress resolution.

In Brazil, secured creditors are banks in most cases, which has an important implication. Resolution 2.682/1999 from CVM (The Securities and Exchange Commission of Brazil) specifies that banks must classify credits from approved reorganization plans as category H. Therefore, it requires banks to provision 100% of the borrowed amount as a guarantee of operation; this requirement reduces bank interest because they earn less in this situation compared to another market alternatives. This implication is line with our results regarding secured creditors (banks, in most of our cases) and unsecured bank loans in Tables 7 and 8.

In addition, divestment proposals increase the likelihood of plan acceptance. This result is in line with Senbet and Wang (2010)Senbet, L. W., & Wang, T. Y. (2010). Corporate financial distress and bankruptcy: A survey. Finance, 5, 243-335. and Giambona et al. (2013)Giambona, E., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Matta, R. (2013). Improved creditor protection and verifiability in the U.S. In Working paper.. https://editorialexpress.com/cgi-bin/conference/download.cgi?db_name=sbe35&paper id=22 (Accessed 23.08.14)

https://editorialexpress.com/cgi-bin/con...

, who argue that higher levels of asset liquidation facilitate the reorganization process. Brown et al. (1994)Brown, D. T., James, C. M., & Mooradian, R. M. (1994). Asset sales by financially distressed firms. Journal of Corporate Finance, 1, 233-257. also show that asset sales benefit creditors more than equityholders in cases of distress.

Concluding remarks

In this paper, we study the likelihood of acceptance of reorganization plans based on a sample of 120 Brazilian firms for the period from 2005 to 2014. To our knowledge, this is the first paper to evaluate the main drivers of the approval of reorganization plans during the creditors’ meeting. Some important results are notable in this paper. First, we show that asset disposal facilitates the approval of reorganization plans as collateral is an important determinant of recovery plan acceptance. Indeed, collateral helps reduce a creditor's loss expectations during the set of challenges that a firm undergoing restructuring is facing.

Second, we confirm that secured debt creditors have lower incentives to accept reorganization plans. Since these creditors have a specific amount in collateral, they may prefer to liquidate the company rather than wait for its recovery. Third, a higher portion of unsecured creditors seems to be related to higher likelihood of acceptance. Since these creditors are more similar to equityholders and are usually out of the money, they may have incentives to approve the plan even if doing so is not best decision for creditors as a whole.

This study also has some limitations. Unfortunately, we do not examine causality in this paper. However, since our purpose in this study was to show the characteristics of reorganization plans by the type of vote, our econometric results merely corroborate our descriptive analysis by controlling for certain variables show only the relation.

Future research can be conducted to analyze whether firms whose reorganization plan was approved achieved success through recovery. We could not analyze this issue in this paper because most of the firms are still in recovery.

-

Peer Review under the responsibility of Departamento de Administração, Faculdade de Economia, Administração e Contabilidade da Universidade de São Paulo – FEA/USP.

References

- Aghion, P., Hart, O. D., & Moore, J. (1992). The economics of bankruptcy reform. Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, 8, 523-546.

- Anapolsky, J. M., & Woods, J. F. (2013). Pitfalls in Brazilian bankruptcy law for international bond investors. Journal of Business & Technology Law, 8, 397-450.

- Araujo, A. P., Ferreira, R. V. X., & Funchal, B. (2012). The Brazilian bankruptcy law experience. Journal of Corporate Finance, 18, 994-1004.

- Araujo, A. P., & Funchal, B. (2009). Lei de Falências Brasileira, A.N. Primeiros Impactos. Journal of Political Economy, 29, 191-212.

- Asquith, P., Gertner, R., & Scharfstein, D. (1994). Anatomy of financial distress: An examination of junk-bond issuers. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109, 625-658.

- Berkovitch, E., & Israel, R. (1999). Optimal bankruptcy laws across different economic systems. Review of Financial Studies, 12, 347-377.

- Bebchuck, L. (2002). Ex ante costs of violating absolute priority in bankruptcy. Journal of Finance, 57, 445-460.

- Bisin, A., & Rampini, A. (2006). Exclusive contracts and the institution of bankruptcy. Economic Theory, 27, 277-304.

- Bolton, P., & Scharfstein, D. (1996). Optimal debt structure with multiple creditors. Journal of Political Economy, 104, 1-25.

- Bris, A., & Welch, I. (2005). The optimal concentration of creditors. Journal of Finance, 60, 2193-2212.

- Brouwer, M. (2006). Reorganization in US and European bankruptcy law. European Journal of Law and Economics, 22, 5-20.

- Brown, D. T. (1989). Claimholder incentive conflicts in reorganization: The role of bankruptcy law. Review of Financial Studies, 2, 109-123.

- Brown, D. T., James, C. M., & Mooradian, R. M. (1994). Asset sales by financially distressed firms. Journal of Corporate Finance, 1, 233-257.

- Claessens, S., & Klapper, L. (2005). Bankruptcy around the world: Explanations of its relative use. American Law and Economics Review, 7, 253-283.

- Cornelli, F., & Felli, L. (1997). Ex ante efficiency of bankruptcy procedures. European Economic Review, 41, 475-485.

- De Assis, D. V. X. D. (2012). Uma Análise Empírica sobre o Processo de Recuperação Econômica pela via judicial adotado pelas sociedades empresárias. Dissertação de Mestrado – Fundação Getulio Vargas, Direito/Rio, Rio de Janeiro.

- Djankov, S., Hart, O., McLiesh, C., & Shleifer, A. (2008). Debt enforcement around the world. Journal of Political Economy, 116, 1105-1149.

- Djankov, S., McLiesh, C., & Shleifer, A. (2007). Private credit in 129 countries. Journal of Financial Economics, 84, 299-329.

- Eberhart, A. C., Moore, W. T., & Roenfeldt, R. L. (1990). Security pricing and deviations from the absolute priority rule in bankruptcy proceedings. Journal of Finance, 45, 1457-1469.

- Franks, J. R., Nyborg, K. G., & Torous, W. N. (1996). A comparison of US, UK, and German insolvency codes. Financial Management, 25, 86-101.

- Franks, J. R., & Torous, W. N. (1989). An empirical investigation of U.S. firms in reorganization. Journal of Finance, 44, 747-770.

- Franks, J. R., & Torous, W. N. (1994). A comparison of financial recontracting in distressed exchanges and chapter 11 reorganizations. Journal of Financial Economics, 35, 349-370.

- Funchal, B. (2006). Essays on Credit and Bankruptcy Law. In Tese (Doutorado) Rio de Janeiro, FGV: EPGE – Fundação Getulio Vargas.

- Funchal, B., & Clovis, M. (2009). Firms’ capital structure and bankruptcy law design. Journal of Financial Economic Policy, 3, 264-275.

- Gennaioli, N., & Rossi, S. (2010). Judicial discretion in corporate bankruptcy. Review of Financial Studies, 23, 4078-4114.

- Gertner, R., & Scharfstein, D. (1991). A theory of workouts and the effects of reorganization law. Journal of Finance, 46, 1189-1222.

- Giambona, E., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., & Matta, R. (2013). Improved creditor protection and verifiability in the U.S. In Working paper.. https://editorialexpress.com/cgi-bin/conference/download.cgi?db_name=sbe35&paper id=22 (Accessed 23.08.14)

» https://editorialexpress.com/cgi-bin/conference/download.cgi?db_name=sbe35&paper_id=22 - Gilson, S. (1990). Bankruptcy, boards, banks, and blockholders: evidence on changes in corporate ownership and control when firms default. Journal of Financial Economics, 27, 315-353.

- Gilson, S. C. (2012). Creating value through corporate restructuring: Case studies in bankruptcies, buyouts, and breakups (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.278580

» http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.278580 - Gilson, S. C., Hotchkiss, E. S., & Ruback, R. S. (2000). Valuation of bankrupt firms. Review of Financial Studies, 13, 43-74.

- Hackbart, D., Hennessy, C., & Leland, H. (2007). Can the tradeoff theory explain debt structure? Review of Financial Studies, 20, 1389-1428.

- Haugen, R. A., & Senbet, L. W. (1978). The insignificance of bankruptcy costs to the theory of optimal capital structure. Journal of Finance, 33, 383-393.

- Haugen, R. A., & Senbet, L. W. (1988). Bankruptcy and agency costs: Their significance to the theory of optimal capital structure. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 23, 27-38.

- Hege, U., & Mella-Barral, P. (2005). Repeated dilution of diffusely held debt. Journal of Business, 78, 737-786.

- Helwege, J. (1999). How long do junk bonds spend in default? Journal of Finance, 54, 341-357.

- Hotchkiss, E. S., John, K., Mooradian, R., & Thorburn, K. S. (2008). Bankruptcy and the resolution of financial distress. In Working paper. Available at http://mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu/Pages/Faculty/Karin.Thorburn/publications/Ch14-N53090.pdf

» http://mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu/Pages/Faculty/Karin.Thorburn/publications/Ch14-N53090.pdf - James, C. (1996). Bank debt restructurings and the composition of exchange offers in financial distress. Journal of Finance, 51, 711-727.

- Kadiyala, P. (2011). Impact of bankruptcy law reform on capital markets in Brazil. Investment Management & Financial Innovations, 8, 31-41.

- Kaplan, S. N., & Stromberg, P. (2003). Financial contracting theory meets the real world: An empirical analysis of venture capital contracts. Review of Economic Studies, 2003, 281-315.

- Kaplan, S. N., & Strömberg, P. (2004). Characteristics, contracts, and actions: Evidence from venture capitalist analyses. Journal of Finance, 59, 2177-2210.

- Kordana, K. A., & Posner, E. A. (1999). A positive theory of Chapter 11. NYU Law Review, 74, 161-234.

- La Porta, R., Lopez-De-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1997). Legal determinants of external finance. Journal of Finance, 52, 1131-1150.

- Penati, A., & Zingales, L. (1997). Efficiency and distribution in financial restructuring: The Case of Ferruzzi Group. In Working paper. http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/finance/papers/ferfin.pdf (accessed 08.09.13)

» http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/finance/papers/ferfin.pdf - Platt, H., & Platt, M. (2008). Financial distress comparison across three global regions. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 1, 129-162.

- Ponticelli, J. (2012). Court enforcement and firm productivity: Evidence from a bankruptcy reform in Brazil. In Job market paper Barcelona: University Pompeu Fabra.

- Qian, J., & Strahan, P. E. (2007). How laws and institutions shape financial contracts: The case of bank loans. Journal of Finance, 62, 2803-2834.

- Schwartz, A. (1998). A contract theory approach to business bankruptcy. Yale Law Journal, 107, 1806-1851.

- Senbet, L. W., & Wang, T. Y. (2010). Corporate financial distress and bankruptcy: A survey. Finance, 5, 243-335.

- von Thadden, E., Berglöf, E., & Roland, G. (2010). The design of corporate debt structure and bankruptcy. Review of Financial Studies, 23, 2648-2679.

- Winton, A. (1995). Costly state verification and multiple investors: The role of seniority. Review of Financial Studies, 8, 91-123.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

Jan-Mar 2018

History

-

Received

8 July 2016 -

Accepted

5 Nov 2017