ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES:

Priapism is one of the complications of sickle cell disease characterized by a persistent and painful erection, which can lead to erectile dysfunction and sexual impotence. The objective of this study was to understand how men with sickle cell disease and priapism access emergency care.

METHODS:

A qualitative study conducted in a reference healthcare unit to people with sickle cell disease in the second largest city in Bahia. Seven adult men with sickle cell disease who had experienced priapism participated in the study. The data were collected by semi-structured interview and thematic story designs and submitted to content analysis.

RESULTS:

Priapism is seen as a lack of genital health. Participants use strategies to manage it at home to avoid embarrassment, which ends up in cocooning. Access to emergency services is motivated by persistent and relentless pain; and limited by the fear of priapism being mistaken for sexual deviance, lack of knowledge about the complication as a urologic emergency and financial shortfall, which confers a worse prognosis about erectile function. Men are embarrassed and discriminated by healthcare and support professionals, which discourages them from accessing these services in the future.

CONCLUSION:

This study emphasizes the importance of early diagnosis of sickle cell disease, the orientation of family members and the need for healthcare professionals to educate young boys and men with sickle cell disease and their caregivers about priapism in advance to allow adequate self-care and prevent complications.

Keywords:

Erectile dysfunction; Priapism; Sickle cell disease

RESUMO

JUSTIFICATIVA E OBJETIVOS:

O priapismo é uma das complicações da doença falciforme caracterizada por ereção persistente e dolorosa, podendo levar à disfunção erétil e impotência sexual. O objetivo deste estudo foi compreender como os homens com doença falciforme e priapismo acessam os cuidados nos serviços de emergência.

MÉTODOS:

Estudo qualitativo realizado em unidade de saúde referência para pessoas com doença falciforme no segundo maior município baiano. Participaram do estudo 7 homens adultos com doença falciforme que já vivenciaram priapismo. Utilizou-se entrevista semiestruturada e desenhos-história com o tema, analisados por análise de conteúdo.

RESULTADOS:

O priapismo é visto como uma falta de saúde genital. Os participantes usam estratégias para seu manuseio em domicílio para evitar constrangimentos, o que acaba isolando-os socialmente. O acesso aos serviços de emergência é motivado pela dor persistente e irredutível; e limitado pelo temor do priapismo ser confundido como resultado de desvio sexual, desconhecimento da complicação como emergência urológica e carência financeira, o que confere pior prognóstico sobre a função erétil. Os homens sofrem constrangimento e discriminação pelos profissionais de saúde e de apoio das unidades, o que os desmotiva a acessar esses serviços no futuro.

CONCLUSÃO:

Este estudo ressalta a importância do diagnóstico precoce da doença falciforme, da orientação de familiares e da necessidade de os profissionais de saúde educarem os meninos/homens jovens com doença falciforme e seus cuidadores sobre o priapismo de forma prévia, para permitir o adequado autocuidado futuro e prevenção de complicações.

Descritores:

Disfunção erétil; Doença falciforme; Priapismo

INTRODUCTION

Priapism is the total or partial continuous erection of the penis for more than four hours accompanied or not by sexual stimulation and orgasm11 Broderick GA. Priapism and sickle-cell anemia: diagnosis and nonsurgical therapy. J Sex Med. 2012;9(1):88-103.. It is considered a urologic emergency requiring urgent care or even surgical procedure to avoid complications such as irreversible erectile dysfunction22 Roghmann F, Becker A, Sammon JD, Ouerghi M, Sun M, Sukumar S, Djahangirian O, et al. Incidence of priapism in emergency departments in the United States. J Urol. 2013;190(4):1275-80..

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is one of the causes of priapism. SCD is more common among Afrodescendants, affecting about 3,500 births per year in Brazil. The incidence is related to the percentage of Afrodescendants in each region. The state of Bahia has the highest incidence of the disease: it affects 1: 655 live births and 1:17 live births carries the trace33 Cordeiro RC, Ferreira SL, Santos AC. Experiências do adoecimento de pessoas com anemia falciforme e estratégias de autocuidado. Acta Paul Enferm. 2014;27(6):499-504..

SCD interferes in man's life, delays sexual maturation, compromises physical development and causes limitations in several levels due to the clinical variability of this disease44 Rios TAO, Xavier ASG, Carvalho ESS, Passos SSS, Araújo EM, Ferreira SL. Significados do priapismo para pessoas com doença falciforme. In: Carvalho ESS, Xavier ASG, organizadores. Olhares sobre o adoecimento crônico: representações e práticas de cuidado às pessoas com doença falciforme. Feira de Santana: UEFS Editora; 2017. 253-62p.. Priapism is among the SCD complications and retrospective data points out that it affects approximately 30% of men with SCD55 Serjeant G, Hambleton I. Priapism in homozygous sickle cell disease: a 40-year study of the natural history. West Indian Med J. 2015;64(3):175-80..

SCD causes ischemic priapism, with time-dependent hypoxia, hypercapnia, and acidosis. It is a condition analogous to the compartment syndrome, which occurs due to the stagnation of blood in the sinusoids of the corpus cavernosum during physiological erections, obstructing venous drainage. In 12h histological changes occur - interstitial edema, progressive endothelium destruction, basement membrane exposure - and thrombocyte adhesion in 24h. Within 48 hours, there are thrombi in the sinusoidal space, muscle necrosis and fibroblast transformation, culminating in erectile dysfunction11 Broderick GA. Priapism and sickle-cell anemia: diagnosis and nonsurgical therapy. J Sex Med. 2012;9(1):88-103..

Priapism compromises the quality of life of a man with SCD, causing financial, affective, social and sexual impacts. Men with SCD say that priapism brings feelings like shame, humiliation, and fear. The fear of becoming sexually impotent hurts the principle of virility and deconstructs man's masculinity with priapism. Such a scenario develops a refusal of intimacy and difficulties in affective relationships44 Rios TAO, Xavier ASG, Carvalho ESS, Passos SSS, Araújo EM, Ferreira SL. Significados do priapismo para pessoas com doença falciforme. In: Carvalho ESS, Xavier ASG, organizadores. Olhares sobre o adoecimento crônico: representações e práticas de cuidado às pessoas com doença falciforme. Feira de Santana: UEFS Editora; 2017. 253-62p..

The access to healthcare is impaired in men with priapism and SCD due to the barriers in the access to primary care. People with SCD are encouraged to seek secondary care directly66 Gomes LM, Pereira IA, Torres HC, Caldeira AP, Viana MB. Acesso e assistência à pessoa com anemia falciforme na Atenção Primária. Acta Paul Enferm. 2014;27(4):348-55., especially the emergency services. However, in these services, the body may be in a homeostatic imbalance, imposing obstacles that limit life goals, triggering feelings of fear, insecurity, anxiety, and the expectation of quick and effective assistance by the healthcare team77 Carvalho EMMS. A pessoa com doença falciforme em uma unidade de emergência: limites e possibilidades para o cuidar da equipe de enfermagem [Dissertação]. Niterói (RJ): Universidade Federal Fluminense; 2014..

People with SCD seek services more frequently than the general population, and about 29% of these visits result in hospitalization88 Yusuf HR, Atrash HK, Grosse SD, Parker CS, Grant AM. Emergency department visits made by patients with sickle cell disease: a descriptive study, 1999-2007. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4 Suppl):S536-41.. In the U.S., people with SCD reported dissatisfaction with the quality of care provided in urgent care units in addition to the excessive waiting time in comparison with other groups of patients, even when they presented higher levels of pain and were screened as higher priority99 Haywood C, Tanabe P, Naik R, Beach MC, Lanzkron S. The impact of race and disease on sickle cell patient wait times in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(4):651-6.. In Brazil, the access to emergency services is hampered due to overcrowding, inadequate physical structure, the distance between the patient's residence and the unit, and lack of financial resources for commuting1010 Dubeux LS, Freese E, Felisberto E. Acesso a hospitais regionais de urgência e emergência: abordagem aos usuários para avaliação do itinerário e dos obstáculos aos serviços de saúde. Physis. 2013;23(2):345-69..

This study is justified by the importance of SCD as a public health issue in Brazil, with neglected history and high impact in the affected populations and the territories they live due to the lack of knowledge about the implications of the disease. In addition to exploring the health events in patients with SCD, giving more visibility to the subject. Likewise, it favors health professionals' reflection about the structure of the emergency services that assist men with SCD complications, such as priapism, allowing for evaluation and redirection of healthcare actions to better care practices reducing the damages to the sexual health of these men.

This study was guided by the following question: how do men with SCD and priapism access care in emergency services? The overall objective is to understand how men with SCD and priapism access care in emergency services.

METHODS

A qualitative, descriptive, exploratory study conducted in a Hemoglobinopathies Specialized Center (HSC) in the city of Feira de Santana, Bahia, Brazil. This study is linked to the master project "Representations about the body and SCD: repercussions on daily life, care, and sexuality".

The present study and its master project met the ethical principles for research with human beings. The recommendations of the National Research Council, according to Resolution 466/2012 of the National Health Council, were adopted.

Seven men participated in this study with a confirmed diagnosis of SCD, asymptomatic, in an outpatient setting, aged over 18 years, having already experienced priapism at some point in their lives and are frequent visitors of the HSC. The participants were informed about the study's objectives, the voluntary and anonymous character of their participation, and that their acceptance to participate had no relation to their visits to the HSC. Then, they signed the Free and Informed Consent Form (FICT).

The number of participants was established by the data saturation criterion. As "priapism" refers to the Greek god of fertility, Priapus1111 Pal D, Biswal D, Ghosh B. Outcome and erectile function following treatment of priapism: An institutional experience. Urol Ann. 2016;8(1):46-50., to ensure anonymity and secrecy, names of Greek deities were drawn and attributed to portray the participants.

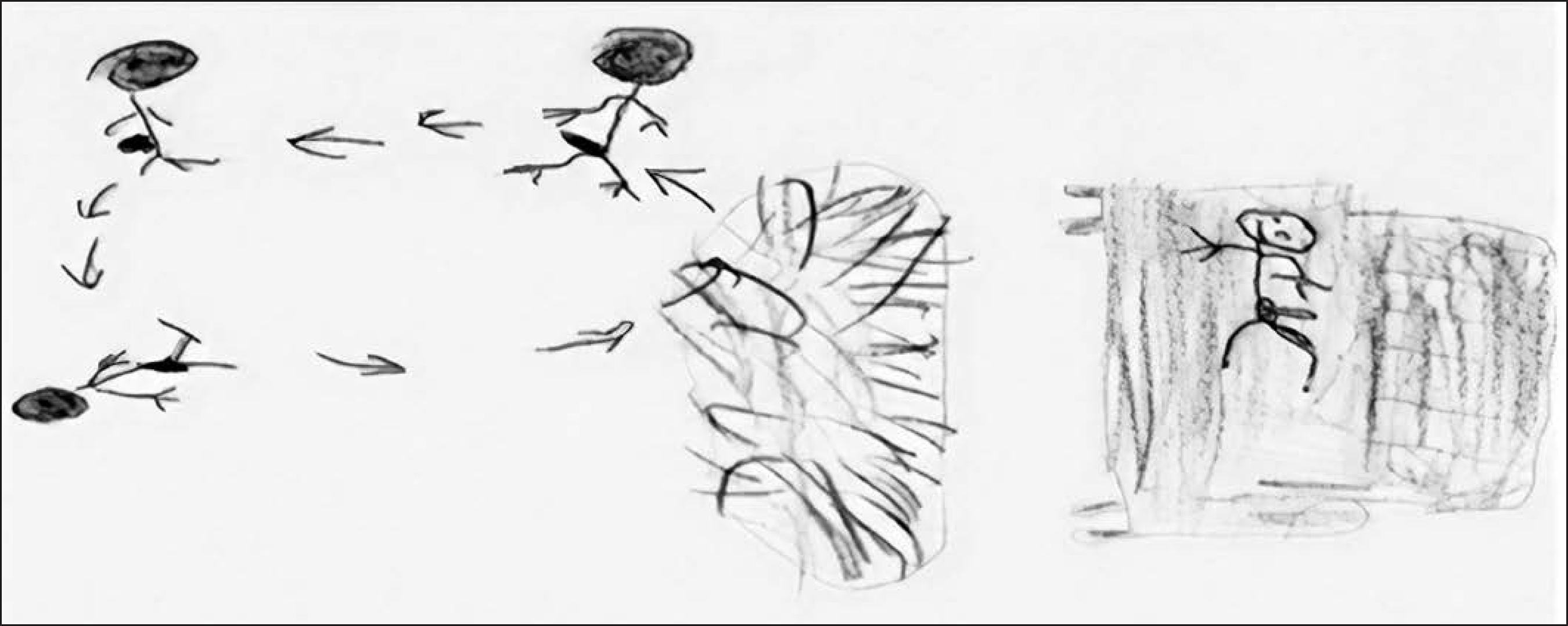

The projective technique of story-theme drawing was used to produce the data. First, the intention and purpose of this technique were explained. Then, the participants received a sheet of paper in blank and pencil, and they were asked to create a drawing on the topic "man with SCD and priapism in the urgent care unit". They were also asked to tell a story about the drawing and give it a title. Subsequently, a semistructured interview was conducted with closed sociodemographic questions and open questions about the priapism experience in the context of emergency services.

The data was collected between November 2016 and February 2017 by a qualified male interviewer, in a closed and private environment (consulting rooms) of the HSC where the participants felt comfortable to share their experiences. The interviews were recorded and transcribed in full immediately after their completion. The average duration of the interviews was 40 minutes, and they were closed when reached the content saturation.

The story-theme drawing has two stages: the creation of the drawing and the production of a story from the drawing created, which allows a subjective and discursive interpretation of the material produced, in which the two stages complete one another. The model proposed by Coutinho1212 Coutinho MC. Sentidos do trabalho contemporâneo: as trajetórias identitárias como estratégia de investigação. Cad Psicol Soc Trab. 2009;12(2):189-202. was used to analyze this material. It consists of systematic observation and superficial reading of the drawings and stories to know the data; select the material by graphic similarity or proximity of themes. Then, followed the other steps, a more in-depth and targeted reading; the analysis and interpretation of the thematic contents grouped by categories and subcategories, and finally, the graphic interpretation of the drawings1212 Coutinho MC. Sentidos do trabalho contemporâneo: as trajetórias identitárias como estratégia de investigação. Cad Psicol Soc Trab. 2009;12(2):189-202..

The content analysis method proposed by Bardin's1313 Bardin L. Análise de Conteúdo. São Paulo: Editora 70; 2011. was used to treat the data, which aims to obtain indicators that allowed the inference of knowledge regarding the conditions of production/reception of these messages. There are three analysis phases: pre-analysis, with the purpose to organize the material, select the documents to be analyzed, formulate hypotheses or guiding questions, elaborate indicators that support the final interpretation. Then the exploitation of the material, where the decisions made in the pre-analysis phase are systematically applied. And then the treatment of the results, where inferences are made and the gross results are transformed into meaningful and valid results, proposing interpretations about the expected objectives or other unexpected discoveries.

RESULTS

Seven men with ages between 27 and 48 years participated in this study. Three were black, three were brown, and one yellow. Four were married; 4 retired; 4 catholic; 5 with limited formal schooling (did not reach high school) and 5 with low income (≤1 minimum wage).

Among their clinical characteristics, 5 had type HbSS, and 2 had type HbSC. The SCD diagnosis was late in 4 men. The first episode of priapism varied from 15 to 27 years old. The average duration of the episodes for 5 men was ≤4h, usually occurring at night. Three men had no episodes of priapism in the last 6 months, while one man reported daily occurrence.

All participants reported pain crises as the reason to seek the emergency (ER). Two men have never sought the ER for priapism. They go from home to the ER by bus, bicycle, taxi or the neighbors give them a ride, and sometimes they walk.

The experiences of men with priapism were organized into three categories which will be presented below:

Interpretation of priapism and strategies to handle it at home

Men with SCD interpret priapism as an injury to health, a disability, or a lack of genital/sexual health. They see it as an involuntary painful erection experience, unpredictable, more frequent at night, that makes urination difficult.

It's complicated to have a long-lasting erection, and moreover, it hurts. What is more difficult in priapism is not the erection, but the pain - Zeus.

It is usually at night, at dawn. I'm sleeping and then I wake up with the erection and already feeling pain - Hades.

In its first occurrences, due to the lack of knowledge of this complication and its connection with SCD, prolonged involuntary erection is attributed to sexual desire and/or greater virility. The worry, fear, and lack of knowledge about how to handle the situation bring thoughts of insecurity and fear of future sexual performance.

I felt like a lucky guy because having an erection for two, three hours ... who can get it? Almost nobody. I did not know that priapism was generated by SCD. I thought it was just me. Only after I had the first crises, I started to read about what SCD was; I could see that priapism came from SCD [...]. In a man's head, what does it mean when you're erect? What do you want? - Zeus.

When it is the first time, he thinks he has a problem, that his health is precarious, and the concern is: what to do? It is bad because he keeps on thinking he will not be able to get laid normally with his wife or girlfriend, he is afraid of failing ...- Hercules.

The experience is also permeated by shame and embarrassment. These situations occur unexpectedly, whether at work, in places with friends and with the family. In general, people around the man with SCD do not know about the priapism complication and its relation to the disease, acting in a prejudiced way and exposing the man with SCD to embarrassing situations.

For those who go through this problem every day, (priapism), it is complicated; it is shame, shyness, prejudice, shameful, you are embarrassed, you cannot explain to someone if you do not have someone close to you to talk, explain your problem - Theseus.

Thus, men with SCD are secluded at home and use strategies to revert the prolonged erection and pain with the use of teas, cold water bath with medicinal plants on the penis, distraction, walking (Figure 1), try to urinate, to masturbate, or seek discreet partners for intercourse in an attempt not to be mistaken or judged as sexual abusers.

Johnny and his cock

Story:"Once upon a time there was this guy, Johnny, who woke up at night after a wonderful dream that he was having sex. When he woke up, his penis was erect; nothing could get his penis down. What did he do? He walked, and walked, and walked in his house... The penis went down slowly, after half an hour, then he laid down again and went to sleep" - Ares.

When I was not oriented, I took showers, got wet, put ice; I was told to bathe my penis with aroeira (a plant), they said that it was good ... I drank sugarcane tea; I stayed under the shower for long periods until that feeling of numbness passed, it seemed that he was numb. It did not pass, it relieved. It passed with time; we also kept it out of mind - Hercules.

It is not telling anyone, to prevent from inventing a story, a gossip, chitchat, so that the people do not create a trap, an invention of something worse, like rape or something, prejudice, you have to talk to someone close to you, who will support you - Theseus.

You wake up at dawn, like that (with priapism), you get up, go to the bathroom, urinate, it continues, what comes to your mind? Oh, I have to get a woman [...] those who don't understand, will throw water, stay under the shower, watch porn, try to masturbate [...] in the man's head, what comes up is to watch a porn movie, masturbate until it diminishes - Zeus.

The strategies for handling priapism are modified based on the guidelines given by health professionals when the man with SCD is able to share his experience with them.

Factors that motivate and limit the access to emergency services

Among the motivating factors to access emergency services, is the failure of home treatment strategies combined with pain becoming unbearable. This fact demonstrates that emergencies, in general, are seen as the last resource to solve priapism. Another factor that helps a man to access these services is that he has a reliable person who offers him support and transportation to the service.

I usually did not go to anyone. Because I was afraid. The last time I had (priapism), I was with my wife, she took me to the ER, but before that, I've never asked for help to anyone - Hermes.

It was not working (the strategies), the pain was constant and what I was doing was not working [...] depends on the pain, the situation at the moment, if it's light, we wait, if it's not possible to go immediately (the ER) not to have complications - Hades.

Shame presents itself in multiple ways among the factors that limit/impair the access: omit to tell the parents about the episodes of priapism in adolescence, predict that he will be attended by a female health professional or predict embarrassing/negative situations because they have already heard negative reports of other men with SCD and priapism. Such aspects affect the image of man as an invulnerable person.

The man has to take care of himself, but it's a shame. He feels ashamed to get there in this embarrassing situation. Getting there running the risk of being attended by a woman, it is more difficult to talk about the subject, priapism, I've heard from a patient who went and felt abashed - Poseidon.

Since the penis is in an advanced erection, there is an embarrassment because people notice it, it is visible, and usually, the person takes the hand to the place because of the pain - Hermes.

She (the mother) scolded me, asking why I did not say anything, why did I hide, I shouldn't, I should have told her, and she would have taken me straight to the hospital - Zeus.

The lack of early diagnosis of SCD, the lack of knowledge of priapism as a complication of SCD and its urologic emergency character (when over 2 hours of duration), and its intermittent occurrence - recurrent episodes of short duration also contribute the delay in seeking care.

The lack of knowledge about the relationship with SCD is mediated by health professionals who, even when assisting the man with SCD since childhood, do not inform the child and its caregivers (usually women) about the possibility of future occurrence and how to handle the event. Young and adult men also feel ashamed in telling the health professional that they have experienced priapism, which highlights the difficulty of discussing sexuality issues during medical visits.

We need to learn. We do not learn this in our daily routine. I have SCD since I was seven, and I learned about it (priapism) only when I was almost 20 [...]. Since it (priapism) is part of SCD, we should know about recurrence, symptoms [...] we had to have this conversation with the doctor in charge of the case, the specialist, but in our entire lives we have not had this conversation, nobody ever told me that it could happen - Hermes.

Another factor that makes it difficult to access emergency services is the transportation to arrive at these services. This depends on the financial resources of the individuals, usually scarce, and with the need to hide the erection (Figure 2) in the priapism crisis during commuting.

The painful walking

Story:"... he called his mother, and his mother called him to go to the bus stop to go to the hospital ... to ask the doctor what was that: the penis was hard, and nothing could soften it. The mother was a little angry because she wanted him to take the bus, but he didn't want to get on the bus because he was ashamed and soon it started to rain. She insisted so much that he got on the bus and went to the hospital under the rain" - Theseus.

I went walking (to the ER), which is not so far, and as I walked from home until there ... about 15 minutes, as I was walking the blood was circulating better, and when I arrived, there was no more (in priapism) - Hades.

Experiences of men with sickle cell disease and priapism in emergency services

In the emergency services, there are embarrassing experiences caused by health professionals and other members of the support staff, such as receptionists and stretcher-bearer. Such experiences are based on prejudice due to the lack of knowledge about SCD and priapism, professional ignorance of genital cases and to keep the privacy of the person. The association of priapism with sexual psychological disorders, masturbation practice, and also the connection of the image of a man with erection in public situations to the stereotype of sexual abuser are extremelly embarassing.

[...] When I was leaving the operating room, the boy carrying the stretcher joked; he said: "you had a lot of hand job, haven't you?" (Masturbation), I was quiet: "No, that was not it" - Zeus.

He was a health professional, he was joking, relaxing, but we were tense ... For other people, it was an offense, and because of this, the person did not want to go to the doctor anymore, because he was ashamed, unable to talk, "Your penis is numb? What have you done, boy?" - Hercules.

The lack of knowledge of the diagnosis of SCD by the man who experiences the first priapism events, added to the ignorance of health professionals, contribute to a possible unwillingness to be attended by these professionals, which causes even more embarrassment in men and delayed care.

Previously, when we did not know it was SCD, "we were ping-ponged from one to another (professionals)", but today when you say that you have SCD, it's better, it's not perfect, but it improved a lot. They did this to me, they transferred me back and forth, "it is not with this one, refer to another, Dr. John Doe, ah, but he is not here, he is coming, "they played this ping-pong game- Hercules.

After establishing the relationship between priapism and SCD, there is a greater level of clarification due to the information of the health professionals about SCD, priapism, how to handle it, and its complications. Some professionals calm the person and provide a humanized care, encourage the man with priapism to seek discretion and when possible, isolate him as a way to keep his privacy. Care is also given through analgesia, hydration and in severe cases, with the aspiration of the content of the penis (Figure 3).

Priapism of the desert

Story:"When I got to the emergency, I realized that what I thought was good for me was actually bad - I ended up going to surgery, with my penis full of needles, painful sensation - not to mention shame. That's why I drew the cactus, that was how I felt stuck by needles, like thorns, that marked me. Priapism, after the pain crisis, is the worst thing one can have" - Zeus.

The professionals tried to calm me down, the doctor saying it was normal, the urologist, he knew what was happening, so he tried to calm me down, that it was not a voluntary but an involuntary issue. He told me to relax and wait for the procedure. After the procedure (aspiration of the penis), I began to understand a little more what was happening - Hermes.

The expectation of the aspiration of the penis content procedure together with the knowledge of the possibility of complications from priapism, such as erectile dysfunction, evoke feelings of fear and concern. In our country, there is still a shortage of professionals able to perform the procedure of aspiration of the penis, which exposes men with SCD and priapism to a higher risk of complications due to delay in treatment.

The risk of erectile dysfunction increases as seeking help and treatment is delayed. This complication scares the man with SCD, reflecting his vulnerability to depression and the possibility of committing suicide. Although most of them fear sexual impotence, one of the participants reported that it is possible to live with erectile dysfunction provided there is a re-significance of sexual relation, so that pleasure for a man is not only linked to penetration.

It was a very difficult and painful procedure. I ended up with a sequel (erectile dysfunction), sex is not just penetration. So I learned to deal with it, make do with what you have, at first it was complicated, I will not lie, because the erection is an asset to man that you can't take away, you take whatever you want from a man, but do his erection, he gets mad, even suicidal - Zeus.

DISCUSSION

The sociodemographic and clinical profile of the participants in this study is consistent with the literature, that is low schooling, unemployment, low family income1414 Felix AA, Souza HM, Ribeiro SB. Aspectos epidemiológicos e sociais da doença falciforme. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2010;32(3):203-8. and age range of the first episodes of priapism1515 Furtado PS, Costa MP, Ribeiro do Prado Valladares F, Oliveira da Silva L, Lordêlo M, Lyra I, et al. The prevalence of priapism in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease in Brazil. Int J Hematol. 2012;95(6):648-51.. The higher frequency of late diagnosis of SCD in this study can be explained by the fact that mandatory early diagnosis is still recent in Brazil (National Neonatal Screening Program - 2001)1616 Braga JA. Medidas gerais no tratamento das doenças falciformes. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2007;29(3):233-8..

The duration of priapism episodes of less than 4h characterizes intermittent priapism, usually nocturnal and handled successfully with home-based strategies and allows normal erectile function between episodes1717 Dupervil B, Grosse S, Burnett A, Parker C. Emergency department visits and inpatient admissions associated with Priapism among males with sickle cell disease in the United States, 2006-2010. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):2006-10.. However, there is an association between the increase in frequency and duration of the episodes of intermittent priapism preceding major acute attacks (>4h) of greater severity11 Broderick GA. Priapism and sickle-cell anemia: diagnosis and nonsurgical therapy. J Sex Med. 2012;9(1):88-103..

The use of strategies to handle priapism at home is an attempt to avoid long waits and attendance by female health professionals in emergencies - services seen as a last option. However, in more severe cases of priapism, the ineffectiveness of home strategies leads to the idea that priapism is an insoluble problem1818 Addis G, Spector R, Shaw E, Musumadi L, Dhanda C. The physical, social and psychological impact of priapism on adult males with sickle cell disorder. Chronic Illn. 2007;3(2):145-54..

Themes that involve the patients' sexuality, such as priapism, face silence from health professionals. Education for parents/caregivers on priapism is necessary since the childhood of boys with SCD, just as it is routine to approach the warning signs, teaching spleen palpation to recognize splenic sequestration, use of special drugs and vaccines, and other recommendations by health professionals66 Gomes LM, Pereira IA, Torres HC, Caldeira AP, Viana MB. Acesso e assistência à pessoa com anemia falciforme na Atenção Primária. Acta Paul Enferm. 2014;27(4):348-55..

Care is not seen as a male, but female practice, which leads men to subdue their health needs. Health services are often perceived as feminine and fragile spaces, attended and composed by women, generating in men a sense of not belonging to that space1919 Gomes R, Nascimento EF, Araújo FC. [Why do men use health services less than women? Explanations by men with low versus higher education]. Cad Saude Publica. 2007;23(3):565-74. Portuguese.. In addition, the exposure to nudity in emergency services creates discomfort in men and a sense of expropriation of their body, which makes them relinquish their innermost, physical and psychological sphere2020 Pupulim JS, Sawada NO. Physical privacy regarding body exposure and manipulation: perception of hospitalized patients. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2010;19(1):36-44..

Resistance to public transportation and financial restrictions leads to the use of their own car, or friends/family car, or even walking as a means of protection and privacy. In a study carried out in the United States88 Yusuf HR, Atrash HK, Grosse SD, Parker CS, Grant AM. Emergency department visits made by patients with sickle cell disease: a descriptive study, 1999-2007. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4 Suppl):S536-41., 79% of the patients with SCD and pain crisis admitted to the emergency arrived went there walking.

Health professionals and support staff in emergency services generate situations of discrimination and embarrassment to men with SCD in priapism. The body language and the eyes communicate feelings that denounce the act of caring. It is important to be careful with the posture and facial expression to avoid embarrassment to the patient2121 dos Santos RM, Viana IR, da Silva JR, Trezza MC, Leite JL. [The nurse and patient's nudity]. Rev Bras Enferm. 2010;63(6):877-86. Portuguese..

The emergency environment in this study was configured as a space to obtain the first information of priapism as a complication. Health education in the hospital setting may include the spouse or the parents of the hospitalized person, discuss the impact of the disease on the family life, and encourage the adoption of healthy behaviors2222 Silva MA, Pinheiro AK, Souza AM, Moreira AC. Promoção da saúde em ambientes hospitalares. Rev Bras Enferm. 2011;64(3):596-9..

Men with SCD and priapism expressed feelings of fear regarding the surgery to emptying the penis, which converges with the results of a study2323 Fighera J, Viero EV. Vivências do paciente com relação ao procedimento cirúrgico: fantasias e sentimentos mais presentes. Rev SBPH. 2005;8(2):51-63. in which the surgical procedure was related to a kind of abandonment, yet temporary. This interferes with the feeling of life continuity, it appears as something unexpected and unwanted and can be related as the last chance to keep the erectile and sexual function.

Erectile dysfunction is predictable in 90% of the ischemic priapism cases lasting more than 24 hours11 Broderick GA. Priapism and sickle-cell anemia: diagnosis and nonsurgical therapy. J Sex Med. 2012;9(1):88-103., and the duration interferes with the preservation of the function1111 Pal D, Biswal D, Ghosh B. Outcome and erectile function following treatment of priapism: An institutional experience. Urol Ann. 2016;8(1):46-50.. Waiting for a spontaneous resolution of priapism and the delay in seeking professional help in emergency units were common in the reports, indicating the need for investment in education to understand the disease, its complications and the self-care of these men since their childhood, when the first episodes of priapism occur, in addition to informing their families to provide support.

In the present study, reports of men with SCD and erectile dysfunction after priapism stated that they try to keep their sexual life active with their partners, varying positions during intercourse, without any specific strategy. Some of the participants do not have partners, and they did not report any practice of seeking individual pleasure, probably for fear of stimulating new crises. A study1818 Addis G, Spector R, Shaw E, Musumadi L, Dhanda C. The physical, social and psychological impact of priapism on adult males with sickle cell disorder. Chronic Illn. 2007;3(2):145-54.emphasized that participants mentioned the impact on sexual life as the most distressing aspect of priapism; saying that they had nothing to offer their partners in the affective-sexual perspective and felt unable to attract or keep partners, generating loneliness, loss of self-esteem and hope.

CONCLUSION

The experiences of men with SCD and priapism are permeated by feelings of shame and embarrassment, whether at home, in social situations or healthcare service units, undermining access to care. Priapism is a complication that occurs in the adolescence and early adulthood of man, a period in which many still live with their parents and hide the occurrence of the episodes, making it difficult to seek help.

The attribution of different meanings to priapism by men with SCD is influenced by the access to the early diagnosis of SCD, so that not knowing the etiological relation of priapism to the disease, men can understand it as a demonstration of virility and sexual potency. Even attributing positive meanings, the man with priapism adopts measures at home to induce the relief of pain and the detumescence of the organ. The persistence of pain, associated with the failure of these measures, motivates the man with SCD and priapism to seek emergency services late and in general, supported by people whom he trusts.

Access to care in emergency services is hampered by the embarrassment imposed by priapism and by the financial situation of men with SCD. The embarrassment is present in every moment of the journey to access specialized care. It is present at the moment of asking for help, when using a means of transportation to go to the emergency unit (reason why some prefer to walk) and is also anticipated when the man with SCD assumes that he will be attended by female health professionals, which hurts his masculinity. And, finally, it is materialized when attended by unskilled professionals.

The lack of knowledge of priapism as a urological emergency, its consequences and the recurrent character of shorter duration of intermittent priapism also discourage the search for emergency care help by men with SCD.

In the emergency care units, the man with SCD and priapism still faces embarrassing situations when interacting with health professionals and support staff (reception, stretcher bearers, janitors, among others). This is based on the lack of knowledge about the disease and its complications, not to mention the association of the man in a situation of erection in public with the stereotype of sexual abuser and of people with sexual deviations. In spite of these limitations, in these emergency care units, the man with priapism obtains professional information about the SCD and the care measures required in new occurrences of priapism, and its consequences.

Because of the delay in seeking help and being treated at the emergency care units, it is often necessary to have more invasive and complex procedures such as penis emptying surgeries, which generates feelings of fear and uncertainty for the man with priapism over his future sexual performance due to the possibility of erectile dysfunction. In this sense, this study indicates that it is necessary to review the existing protocols to define the waiting time to treatment, taking into account the particularities of each country; such as the mobility conditions of the means of transportation and the quality and efficiency in being promptly cared at the emergency care units in each location.

This study emphasizes the importance of early diagnosis of the sickle cell disease, the education of family members and the need of health professionals to early educate boys and young men with SCD and their caregivers about priapism to allow adequate self-care in the future and avoid complications.

-

Sponsoring sources: Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado da Bahia (FAPESB). Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

To all collaborating authors and those who had direct or indirect participation in this study. To the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development\CNPq. To the Foundation for Research Support of the State of Bahia (FAPESB). To the State University of Feira de Santana

REFERENCES

-

1Broderick GA. Priapism and sickle-cell anemia: diagnosis and nonsurgical therapy. J Sex Med. 2012;9(1):88-103.

-

2Roghmann F, Becker A, Sammon JD, Ouerghi M, Sun M, Sukumar S, Djahangirian O, et al. Incidence of priapism in emergency departments in the United States. J Urol. 2013;190(4):1275-80.

-

3Cordeiro RC, Ferreira SL, Santos AC. Experiências do adoecimento de pessoas com anemia falciforme e estratégias de autocuidado. Acta Paul Enferm. 2014;27(6):499-504.

-

4Rios TAO, Xavier ASG, Carvalho ESS, Passos SSS, Araújo EM, Ferreira SL. Significados do priapismo para pessoas com doença falciforme. In: Carvalho ESS, Xavier ASG, organizadores. Olhares sobre o adoecimento crônico: representações e práticas de cuidado às pessoas com doença falciforme. Feira de Santana: UEFS Editora; 2017. 253-62p.

-

5Serjeant G, Hambleton I. Priapism in homozygous sickle cell disease: a 40-year study of the natural history. West Indian Med J. 2015;64(3):175-80.

-

6Gomes LM, Pereira IA, Torres HC, Caldeira AP, Viana MB. Acesso e assistência à pessoa com anemia falciforme na Atenção Primária. Acta Paul Enferm. 2014;27(4):348-55.

-

7Carvalho EMMS. A pessoa com doença falciforme em uma unidade de emergência: limites e possibilidades para o cuidar da equipe de enfermagem [Dissertação]. Niterói (RJ): Universidade Federal Fluminense; 2014.

-

8Yusuf HR, Atrash HK, Grosse SD, Parker CS, Grant AM. Emergency department visits made by patients with sickle cell disease: a descriptive study, 1999-2007. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4 Suppl):S536-41.

-

9Haywood C, Tanabe P, Naik R, Beach MC, Lanzkron S. The impact of race and disease on sickle cell patient wait times in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(4):651-6.

-

10Dubeux LS, Freese E, Felisberto E. Acesso a hospitais regionais de urgência e emergência: abordagem aos usuários para avaliação do itinerário e dos obstáculos aos serviços de saúde. Physis. 2013;23(2):345-69.

-

11Pal D, Biswal D, Ghosh B. Outcome and erectile function following treatment of priapism: An institutional experience. Urol Ann. 2016;8(1):46-50.

-

12Coutinho MC. Sentidos do trabalho contemporâneo: as trajetórias identitárias como estratégia de investigação. Cad Psicol Soc Trab. 2009;12(2):189-202.

-

13Bardin L. Análise de Conteúdo. São Paulo: Editora 70; 2011.

-

14Felix AA, Souza HM, Ribeiro SB. Aspectos epidemiológicos e sociais da doença falciforme. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2010;32(3):203-8.

-

15Furtado PS, Costa MP, Ribeiro do Prado Valladares F, Oliveira da Silva L, Lordêlo M, Lyra I, et al. The prevalence of priapism in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease in Brazil. Int J Hematol. 2012;95(6):648-51.

-

16Braga JA. Medidas gerais no tratamento das doenças falciformes. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2007;29(3):233-8.

-

17Dupervil B, Grosse S, Burnett A, Parker C. Emergency department visits and inpatient admissions associated with Priapism among males with sickle cell disease in the United States, 2006-2010. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):2006-10.

-

18Addis G, Spector R, Shaw E, Musumadi L, Dhanda C. The physical, social and psychological impact of priapism on adult males with sickle cell disorder. Chronic Illn. 2007;3(2):145-54.

-

19Gomes R, Nascimento EF, Araújo FC. [Why do men use health services less than women? Explanations by men with low versus higher education]. Cad Saude Publica. 2007;23(3):565-74. Portuguese.

-

20Pupulim JS, Sawada NO. Physical privacy regarding body exposure and manipulation: perception of hospitalized patients. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2010;19(1):36-44.

-

21dos Santos RM, Viana IR, da Silva JR, Trezza MC, Leite JL. [The nurse and patient's nudity]. Rev Bras Enferm. 2010;63(6):877-86. Portuguese.

-

22Silva MA, Pinheiro AK, Souza AM, Moreira AC. Promoção da saúde em ambientes hospitalares. Rev Bras Enferm. 2011;64(3):596-9.

-

23Fighera J, Viero EV. Vivências do paciente com relação ao procedimento cirúrgico: fantasias e sentimentos mais presentes. Rev SBPH. 2005;8(2):51-63.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

Jan-Mar 2019

History

-

Received

20 July 2018 -

Accepted

17 Sept 2018