ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES:

Burning mouth syndrome is a dysfunctional state affecting physical, mental and social welfare, often contributing to chronic stress conditions. Despite the lack of objective data, patients experience pain-related discomfort with impact in their daily life. The objective of this study was to assess the impact of burning mouth syndrome on pain perception and quality of life.

METHODS:

A cross-sectional, observational, case-controlled study was performed on 76 individuals (38 in each group). The groups were sex- and age-matched. The Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-14) questionnaire was used to assess any changes in the quality of life. The visual analog scale was used to assess pain impact and intensity, as well as the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS). The effect of sex and other risk factors associated with burning mouth syndrome were also associated.

RESULTS:

The age of participants was 41 to 85 years. The patients had a negative impact on quality of life with respect to all dimensions of OHIP-14 and PCS domains. Burning mouth syndrome patients complained about moderate (58%) or intense (42%) pain, while the control group participants experienced only mild pain by visual analog scale. The prevalence was predominant in females (a ratio of 3:1), and the most site involved was the tongue. Menopause, hormonal changes, and gastritis were identified as major risk factors.

CONCLUSION:

Burning mouth syndrome patients had significantly higher PCS and OHIP-14 scores for all domains, indicating an interaction between a higher burden of pain perception and worse quality of life which should therefore be adequately assessed, characterized and managed.

Keywords:

Burning mouth syndrome; Pain; Pain perception; Quality of life

RESUMO

JUSTIFICATIVA E OBJETIVOS:

A síndrome de ardência bucal é um estado disfuncional que afeta o bem-estar físico, mental e social, contribuindo para condições de estresse crônico. Apesar da ausência de dados objetivos, os pacientes experimentam desconforto relacionado à dor com impacto na vida diária. O objetivo deste estudo foi avaliar o impacto da síndrome da boca ardente na percepção da dor e na qualidade de vida.

MÉTODOS:

Foi realizado um estudo transversal, observacional e caso-controle em 76 indivíduos, 38 em cada grupo, pareados por gênero e idade. Foram utilizados o questionário Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-14) para avaliar mudanças na qualidade de vida, a escala analógica visual para o impacto e intensidade da dor e a Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS). Foi avaliado também o efeito do sexo, idade e outros fatores de risco associados à síndrome de ardência bucal.

RESULTADOS:

A idade dos participantes foi de 41 a 85 anos. A síndrome de ardência bucal teve um impacto negativo na qualidade de vida em todas as dimensões dos domínios OHIP-14 e PCS. Cinquenta e oito por cento dos pacientes se queixaram de dor moderada e 42% de dor intensa, enquanto os controles experimentaram apenas dor leve pela escala analógica visual. A prevalência foi predominante no sexo feminino (3:1), e a língua foi o local envolvido mais comum. Menopausa, alterações hormonais e gastrite foram os maiores fatores de risco.

CONCLUSÃO:

Os pacientes com síndrome de ardência bucal apresentaram escores PCS e OHIP-14 mais altos para todos os domínios, indicando uma interação entre maior carga de percepção da dor e pior qualidade de vida, o que deve ser mais bem avaliado, caracterizado e gerenciado.

Descritores:

Dor; Percepção da dor; Qualidade de vida; Síndrome da boca ardente

INTRODUCTION

Burning mouth syndrome (BMS) is often present in individuals with orofacial pain that do not exhibit other symptoms of dental or systemic origin or oral lesions. It manifests as a burning sensation in the mouth and can affect the tongue, lips, or entire mouth. Other symptoms include xerostomia, oral paresthesia, and altered taste and smell. BMS occurs more frequently in women, and its frequency increases with age and after menopause11 Zakrzewska JM, Forssell H, Glenny AM. Interventions for the treatment of burning mouth syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;25(1):CD002779.. The overall prevalence is reported to be 0.5−5% and up to 12−18% in middle-aged, postmenopausal, or elderly women. Some studies have demonstrated a female-based prevalence with a gender ratio (female:male) of 5:1 or 3:122 Yilmaz Z, Renton T, Yiangou Y, Zakrzewska J, Chessell IP, Bountra C, Anand P. Burning mouth syndrome as a trigeminal small fibre neuropathy: increased heat and capsaicin receptor TRPV1 in nerve fibres correlates with pain score. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;14(9):864-71.

3 Schiavone V, Adamo D, Ventrella G, Morlino M, De Notaris EB, Ravel MG et al. Anxiety, depression, and pain in burning mouth syndrome: first chicken or egg? Headache. 2012;52(6):1019-25.

4 Zakrzewska JM. Differential diagnosis of facial pain and guidelines for management. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111(1):95-104.-55 Tait RC, Ferguson M, Herndon CM. Chronic orofacial pain: burning mouth syndrome and other neuropathic disorders. J Pain Manag Med. 2017;3(1). pii:120.. The psychological profile of these patients is often similar, with high levels of stress, anxiety, and depression possibly being the result of chronic pain rather than an etiological factor55 Tait RC, Ferguson M, Herndon CM. Chronic orofacial pain: burning mouth syndrome and other neuropathic disorders. J Pain Manag Med. 2017;3(1). pii:120.

6 Carlson CR, Miller CS, Reid KI. Psychosocial profiles of patients with burning mouth syndrome. J Orofac Pain. 2000;14(1):59-64.

7 Danhauer SC, Miller CS, Rhodus NL, Carlson CR. Impact of criteria-based diagnosis of burning mouth syndrome on treatment outcome. J Orofac Pain. 2002;16(4):305-11.-88 Galli F, Lodi G, Sardella A, Vegni E. Role of psychological factors in burning mouth syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cephalalgia. 2017;37(3):265-77.. Neuropathic mechanisms were proposed to cause BMS; this is supported by findings of histology, neurophysiology, brain imaging, and quantitative sensory tests, whereas BMS pathophysiology suggests a combined role of hormonal, neuropathic, and genetic factors. Pain in BMS is often triggered by spicy and acidic food, stress, and fatigue. However, symptomatic relief can be provided by eating dessert jelly, chewing gum, or sucking on dried fruit99 Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3(rd) ed. (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33(9) 629-808.

10 Jääskeläinen SK, Woda A. Burning mouth syndrome. Cephalalgia. 2017;37(7):627-47.-1111 Jääskeläinen SK. Pathophysiology of primary burning mouth syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol. 2012;123(1):71-7..

BMS is divided into three types based on the frequency of symptom fluctuation and intensity; type I (35%): symptoms present every day, with a delay after waking up or present throughout the day with the intensity increasing in the evening; type II (55%): symptoms present every day, starting immediately after waking up, and usually associated with psychological disorders; type III (10%): symptoms are rare and confined to unusual regions, such as the neck, and are commonly due to allergic reactions or local factors1212 Lamey PJ. Burning mouth syndrome. Dermatol Clin. 1996;21(4):339-54.,1313 Cocolescu EC, Tovaru S, Cocolescu BI. Epidemiological and etiological aspects of burning mouth syndrome. J Med Life. 2014;7(3):305-9..

Differential diagnosis often requires assessment for lichen planus, candidiasis, hormonal disorders, gastroesophageal reflux, psychosocial stress, nutritional or vitamin deficiencies, diabetes, dry mouth, contact allergies, galvanism, parafunctional habits, cranial nerve injuries, and side-effects of drugs11 Zakrzewska JM, Forssell H, Glenny AM. Interventions for the treatment of burning mouth syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;25(1):CD002779.,1414 Patton LL, Siegel MA, Benoliel R, De Laat A. Management of burning mouth syndrome: systematic review and management recommendations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103(Suppl):S39e1-13.. Further complementary exams include blood tests to evaluate thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), free thyroxin (T4), iron, ferritin, transferrin, 25 hydroxyvitamin D, vitamins B2, B6, B1, and B12, zinc, folic acid, fasting glycemia, lingual nerve block with lidocaine, salivary flow measurements, evaluation of taste function, microbiological swabs (bacteria, viruses, or fungi),( )and glycosylated hemoglobin for diabetics as well as rheumatological and autoimmune tests in cases of suspected autoimmune disease88 Galli F, Lodi G, Sardella A, Vegni E. Role of psychological factors in burning mouth syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cephalalgia. 2017;37(3):265-77.,1010 Jääskeläinen SK, Woda A. Burning mouth syndrome. Cephalalgia. 2017;37(7):627-47.. Additionally, quantitative sensorial tests, functional magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomography, and tests for validated salivary biomarkers such as alpha-enolase, interleukin-18, and kallikrein-13 are also performed1515 Ji EH, Diep C, Liu T, Li H, Merrill R, Messadi D, et al. Potential protein biomarkers for burning mouth syndrome discovered by quantitative proteomics. Mol Pain. 2017;13:1744806916686796..

As a differential diagnosis is necessary, few dentists are qualified to assess this syndrome, and thus the greatest difficulty experienced by BMS patients is the lack of an accurate diagnosis. This leads many patients to report oncophobia, loss of taste, difficulty in eating, and emotional problems, as there is a need for more good quality data for both professionals and patients.

This study aimed to assess whether the intensity of BMS changes the quality of life using instruments such as the visual analog scale (VAS), pain catastrophizing scale (PCS), and oral health impact profile (OHIP-14) questionnaire, as well as to assess the risk factors involved, such as gender and age.

METHODS

An observational, cross-sectional, case-controlled study to evaluate the impact of BMS on oral health-related quality of life and pain perception using the OHIP-14 questionnaire, PCS, and VAS. The sample size was composed of 76 individuals with 38 age- and gender-matched individuals per group and was based on the study(16 )with 60 patients. Most studies are unlikely to have a larger sample size except for multicenter studies1616 Mendak-Ziólko M, Konopka T, Bogucki ZA. Evaluation of select neurophysiological, clinical and psychological tests for burning mouth syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;114(3):325-32.,1717 Brailo V, Firic M, Vucicevic BV, Andabak RA, Krstevski I, Alajbeg I. Impact of reassurance on pain perception in patients with primary burning mouth syndrome. Oral Dis. 2016;22(6):512-6..

The study was carried out in the Clinic of Stomathology of Faculdade de Odontologia de São Leopoldo Mandic, Clinic of Stomathology of Associação de Cirurgiões Dentistas de Campinas and on the Screening Clinic of São Leopoldo Mandic for the control group.

Male and female individuals aged over 18 years old, who had daily untreated burning mouth symptoms for at least 3 months were included. The exclusion criteria were symptoms of dental or systemic origin, lesions in the mouth, and unwillingness to sign the Free and Informed Consent Term (FICT). The control group consisted of individuals who arrived at the screening clinic with or without injury in the mouth, without a BMS history, who signed the FICT, and could be matched by age group.

Patient data was collected, including age, gender, menopause status, OHIP-14, PCS, VAS, drugs used, site, pain duration, and previous illnesses.

The study was approved by the Faculdade de Odontologia de São Leopoldo Mandic ethics committee under No. 1,795,967.

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 25.0) was used for data analysis. A value of p<0.05 indicated statistical significance. Comparisons between groups were performed using Chi-square tests for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney U tests for numerical variables.

RESULTS

Comparisons between individuals of both groups were performed for categorical variables (using a Chi-Square test) according to gender, menopause status, diabetes, hypertension, gastritis, cholesterol, and antidepressant and benzodiazepine usage (Table 1).

The most common site in BMS patients was the tongue (73.7%), followed by the palate and whole mouth (23.7%), lips (13.2%), oral mucosa (10.5%), alveolar ridge (5.3%), and throat (5.2%) (Figure 1).

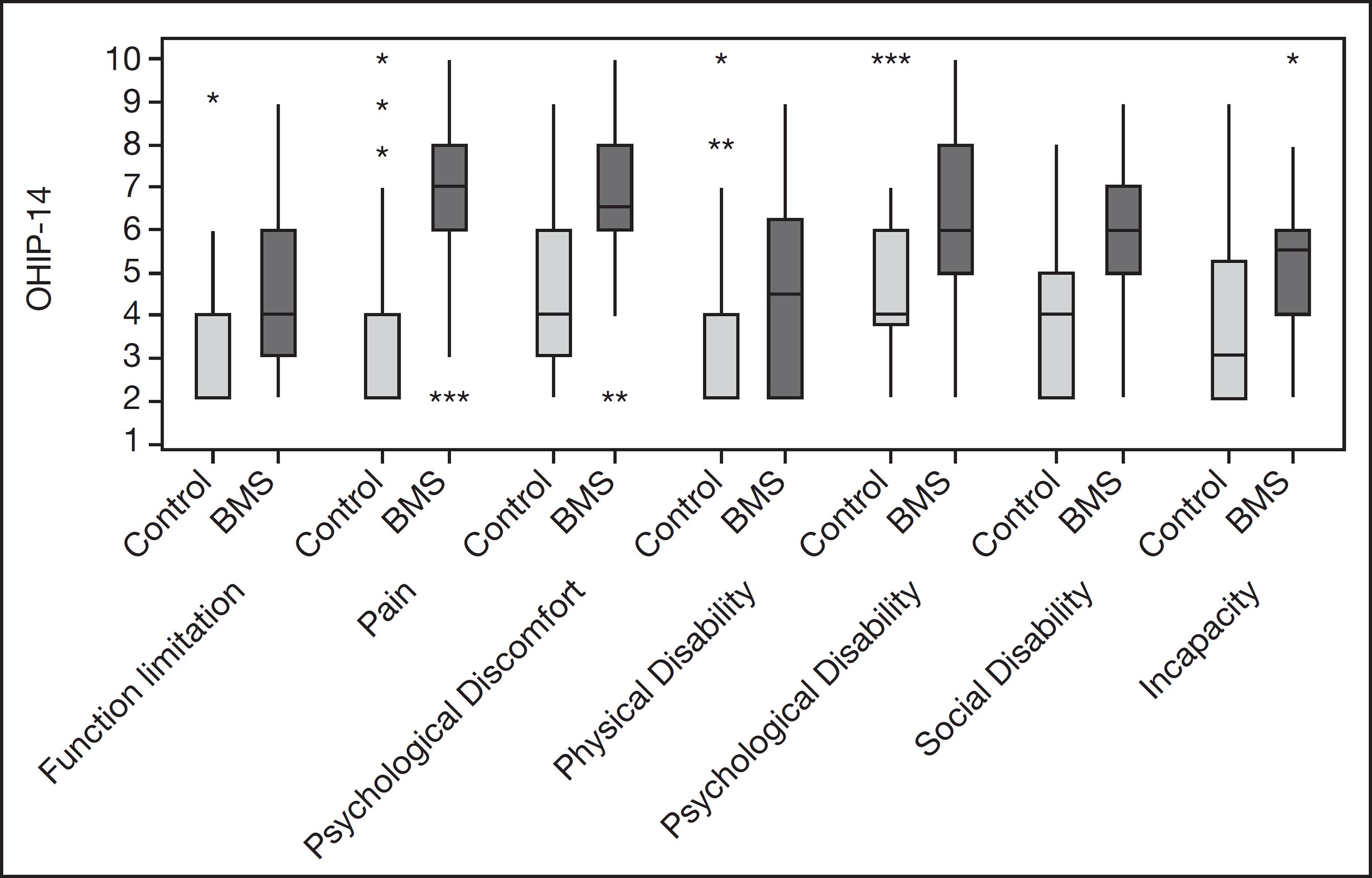

The OHIP-14 questionnaire evaluated the impact of oral health on quality of life focusing on social, psychological, and physical dimensions. The questionnaire consisted of 14 questions assessing the following seven dimensions: functional limitation (speech and taste), pain (feeling of pain), psychological discomfort (worry and stress), physical disability (feeding impairment), psychological disability (difficulty in relaxing and shame), social disability (irritation and daily activities), and incapacity (inability to perform daily activities) (Figure 2)1818 Slade GD. Assessing change in quality of life using the Oral Health Impact Profile. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998;26(1):52-61.,1919 Zucoloto ML, Maroco J, Campos JA. Psychometric properties of the oral health impact profile and new methodological approach. J Dent Res. 2014;93(7):645-50..

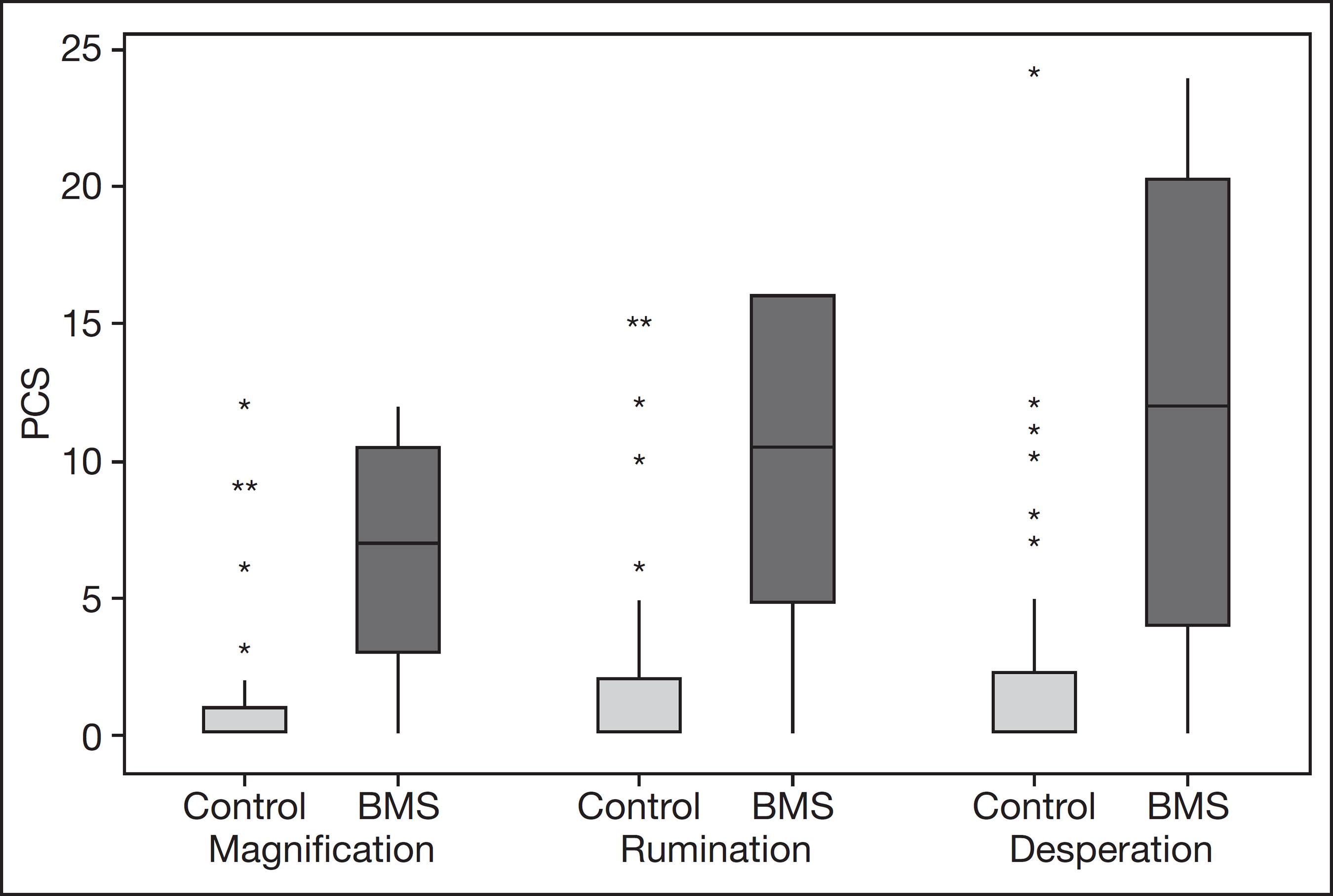

The PCS contained 13 subscales that assessed the degree of thinking or feeling regarding pain and was used to demonstrate daily impact in three domains: magnification (enlargement), rumination (persistent reflection), and desperation (hopelessness). The VAS and PCS were used to assess pain intensity and interference with mood in all patients, with scores from 0 (indicating no pain/burning) to 10 (the worst possible pain/burning) (Figures 3 and 4, Table 2)2020 Sullivan MJL, Bishop S, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7:432-524.,2121 Sehn F, Chachamovich E, Vidor LP, Dall-Agnol L, Souza IC, Torres IL, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the pain catastrophizing scale. Pain Med. 2012;13(11):1425-35..

DISCUSSION

The mean age of the population was similar to those in other studies1616 Mendak-Ziólko M, Konopka T, Bogucki ZA. Evaluation of select neurophysiological, clinical and psychological tests for burning mouth syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;114(3):325-32.,1717 Brailo V, Firic M, Vucicevic BV, Andabak RA, Krstevski I, Alajbeg I. Impact of reassurance on pain perception in patients with primary burning mouth syndrome. Oral Dis. 2016;22(6):512-6.,2222 Steele JC. The practical evaluation and management of patients with symptoms of a sore burning mouth. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34(4):449-57.

23 Netto FO, Diniz IM, Grossmann SM, de Abreu MH, do Carmo MA, Aguiar MC. Risk factors in burning mouth syndrome: a case-control study based on patient records. Clin Oral Investig. 2011;15(4):571-5.-2424 Kohorst JJ, Bruce AJ, Torgerson RR. A population-based study of the incidence of burning mouth syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(11):1545-52.. Comorbidities such as hypertension, gastritis, high cholesterol, and benzodiazepine use were significantly more frequent in the BMS group (Table 1), consistent with previous findings33 Schiavone V, Adamo D, Ventrella G, Morlino M, De Notaris EB, Ravel MG et al. Anxiety, depression, and pain in burning mouth syndrome: first chicken or egg? Headache. 2012;52(6):1019-25.,2323 Netto FO, Diniz IM, Grossmann SM, de Abreu MH, do Carmo MA, Aguiar MC. Risk factors in burning mouth syndrome: a case-control study based on patient records. Clin Oral Investig. 2011;15(4):571-5.,2525 Nosratzehi T, Salimi S, Parvaee A. Comparison of salivary cortisol and a-amylase levels and psychological profiles in patients with burning mouth syndrome. Spec Care Dentist. 2017;37(3):120-5.

26 López-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Andujar-Mateos P, Sánchez-Siles M, Gómez-Garcia F. Burning mouth syndrome: an update. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2010;15(4):e562-8.-2727 Brailo V, Vuéiaeeviae-Boras V, Alajbeg IZ, Alajbeg I, Lukenda J, Aeurkoviae M. Oral burning symptoms and burning mouth syndrome-significance of different variables in 150 patients. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2006;11(3):E252-5.. No significant differences were found between groups regarding diabetes, depression, and psychiatric disorders, which is in contrast with the findings of study2222 Steele JC. The practical evaluation and management of patients with symptoms of a sore burning mouth. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34(4):449-57., which found comorbidities such as diabetes, hypothyroidism, depression, and anxiety present with BMS2727 Brailo V, Vuéiaeeviae-Boras V, Alajbeg IZ, Alajbeg I, Lukenda J, Aeurkoviae M. Oral burning symptoms and burning mouth syndrome-significance of different variables in 150 patients. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2006;11(3):E252-5.. Studies have shown that patients with BMS may have psychiatric and anxiety disorders33 Schiavone V, Adamo D, Ventrella G, Morlino M, De Notaris EB, Ravel MG et al. Anxiety, depression, and pain in burning mouth syndrome: first chicken or egg? Headache. 2012;52(6):1019-25.,2525 Nosratzehi T, Salimi S, Parvaee A. Comparison of salivary cortisol and a-amylase levels and psychological profiles in patients with burning mouth syndrome. Spec Care Dentist. 2017;37(3):120-5..

The prevalence of BMS was higher in females (78.9%) and after menopause (93.3%); however, no significant differences were observed between the age-matched groups. Additionally, hormonal changes and gastritis were important risk factors (Table 1). This is consistent with most studies, such as The International Classification of Headache Disorders (2013), which mentions the tip of the tongue as the most frequent site99 Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3(rd) ed. (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33(9) 629-808..

All the domains of both OHIP-14 and PCS were significantly different in the BMS group compared with the control group, indicating a negative impact on the patients’ quality of life (Figures 2 and 3). Authors1717 Brailo V, Firic M, Vucicevic BV, Andabak RA, Krstevski I, Alajbeg I. Impact of reassurance on pain perception in patients with primary burning mouth syndrome. Oral Dis. 2016;22(6):512-6. also demonstrated a significant difference in OHIP-14 and PCS1717 Brailo V, Firic M, Vucicevic BV, Andabak RA, Krstevski I, Alajbeg I. Impact of reassurance on pain perception in patients with primary burning mouth syndrome. Oral Dis. 2016;22(6):512-6.. The mean value of pain perception in BMS patients, as evaluated by the VAS, was 6.64; patients exhibited moderate (58%) and intense (42%) pain perception, with no patient showing mild pain. In the control group, the highest value recorded was 4. Furthermore, the VAS scores increased in the BMS group (Figure 4 and Table 2).

Frequency of intensity of pain perception in the burning mouth syndrome group (Moderate: 3 to 7; Intense: 8 to 10) VAS = visual analog scale.

New longitudinal studies on BMS are required, since in this study it was observed that individuals who complained of burning mouth had already sought out several dentists who were unable to diagnose the syndrome. As a result, these patients undergo anxiety due to the absence of a correct diagnosis. Therefore, studies addressing BMS are crucial, as it seems that BMS is not rare, but underdiagnosed, and can be confused with an allergy due to methylparaben (found in toothpaste), resins, certain types of food, or even by injuries such as candidiasis, lichen planus, gastroesophageal reflux, gastritis, diabetes, thyroid disorder, and vitamin deficiencies. In addition, these individuals reported that the triggers to these burning symptoms included loss of taste, emotional triggers, and seeking psychological/psychiatric treatment due to anxiety and depression. It is important to emphasize that very detailed anamnesis and specific tests are needed for differential diagnoses of BMS. It should also be noted that BMS originates from a peripherally or centrally acting neuropathy, therefore requiring neurological evaluation. This syndrome as well as temporal mandibular joint and orofacial pain are highly complex, and a transdisciplinary approach is necessary for their management.

CONCLUSION

The present study has demonstrated that BMS patients had significantly higher PCS and OHIP-14 scores for all domains. This indicates an interaction between a higher burden of pain perception and decreased quality of life, which should be adequately assessed, characterized, and managed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Campinas Municipal Secretary helped in the enrollment of patients for the study. Campinas Dental Surgeons Association authorized the use of their facilities for research in the Clinic of Stomatology.

REFERENCES

-

1Zakrzewska JM, Forssell H, Glenny AM. Interventions for the treatment of burning mouth syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;25(1):CD002779.

-

2Yilmaz Z, Renton T, Yiangou Y, Zakrzewska J, Chessell IP, Bountra C, Anand P. Burning mouth syndrome as a trigeminal small fibre neuropathy: increased heat and capsaicin receptor TRPV1 in nerve fibres correlates with pain score. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;14(9):864-71.

-

3Schiavone V, Adamo D, Ventrella G, Morlino M, De Notaris EB, Ravel MG et al. Anxiety, depression, and pain in burning mouth syndrome: first chicken or egg? Headache. 2012;52(6):1019-25.

-

4Zakrzewska JM. Differential diagnosis of facial pain and guidelines for management. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111(1):95-104.

-

5Tait RC, Ferguson M, Herndon CM. Chronic orofacial pain: burning mouth syndrome and other neuropathic disorders. J Pain Manag Med. 2017;3(1). pii:120.

-

6Carlson CR, Miller CS, Reid KI. Psychosocial profiles of patients with burning mouth syndrome. J Orofac Pain. 2000;14(1):59-64.

-

7Danhauer SC, Miller CS, Rhodus NL, Carlson CR. Impact of criteria-based diagnosis of burning mouth syndrome on treatment outcome. J Orofac Pain. 2002;16(4):305-11.

-

8Galli F, Lodi G, Sardella A, Vegni E. Role of psychological factors in burning mouth syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cephalalgia. 2017;37(3):265-77.

-

9Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3(rd) ed. (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33(9) 629-808.

-

10Jääskeläinen SK, Woda A. Burning mouth syndrome. Cephalalgia. 2017;37(7):627-47.

-

11Jääskeläinen SK. Pathophysiology of primary burning mouth syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol. 2012;123(1):71-7.

-

12Lamey PJ. Burning mouth syndrome. Dermatol Clin. 1996;21(4):339-54.

-

13Cocolescu EC, Tovaru S, Cocolescu BI. Epidemiological and etiological aspects of burning mouth syndrome. J Med Life. 2014;7(3):305-9.

-

14Patton LL, Siegel MA, Benoliel R, De Laat A. Management of burning mouth syndrome: systematic review and management recommendations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103(Suppl):S39e1-13.

-

15Ji EH, Diep C, Liu T, Li H, Merrill R, Messadi D, et al. Potential protein biomarkers for burning mouth syndrome discovered by quantitative proteomics. Mol Pain. 2017;13:1744806916686796.

-

16Mendak-Ziólko M, Konopka T, Bogucki ZA. Evaluation of select neurophysiological, clinical and psychological tests for burning mouth syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;114(3):325-32.

-

17Brailo V, Firic M, Vucicevic BV, Andabak RA, Krstevski I, Alajbeg I. Impact of reassurance on pain perception in patients with primary burning mouth syndrome. Oral Dis. 2016;22(6):512-6.

-

18Slade GD. Assessing change in quality of life using the Oral Health Impact Profile. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998;26(1):52-61.

-

19Zucoloto ML, Maroco J, Campos JA. Psychometric properties of the oral health impact profile and new methodological approach. J Dent Res. 2014;93(7):645-50.

-

20Sullivan MJL, Bishop S, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7:432-524.

-

21Sehn F, Chachamovich E, Vidor LP, Dall-Agnol L, Souza IC, Torres IL, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the pain catastrophizing scale. Pain Med. 2012;13(11):1425-35.

-

22Steele JC. The practical evaluation and management of patients with symptoms of a sore burning mouth. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34(4):449-57.

-

23Netto FO, Diniz IM, Grossmann SM, de Abreu MH, do Carmo MA, Aguiar MC. Risk factors in burning mouth syndrome: a case-control study based on patient records. Clin Oral Investig. 2011;15(4):571-5.

-

24Kohorst JJ, Bruce AJ, Torgerson RR. A population-based study of the incidence of burning mouth syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89(11):1545-52.

-

25Nosratzehi T, Salimi S, Parvaee A. Comparison of salivary cortisol and a-amylase levels and psychological profiles in patients with burning mouth syndrome. Spec Care Dentist. 2017;37(3):120-5.

-

26López-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Andujar-Mateos P, Sánchez-Siles M, Gómez-Garcia F. Burning mouth syndrome: an update. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2010;15(4):e562-8.

-

27Brailo V, Vuéiaeeviae-Boras V, Alajbeg IZ, Alajbeg I, Lukenda J, Aeurkoviae M. Oral burning symptoms and burning mouth syndrome-significance of different variables in 150 patients. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2006;11(3):E252-5.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

03 June 2020 -

Date of issue

Jan-Mar 2020

History

-

Received

01 Jan 2020 -

Accepted

22 Apr 2020