ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES:

The relationship between spirituality and cancer coping is still a challenge for comprehensive health care. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze whether the level of spirituality directly interferes with clinical markers, such as pain intensity in people with cancer. The present study aims to investigate the relationship between spirituality and pain coping and the strategies used in adult cancer patients.

CONTENTS:

This is a systematic review, registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews: CRD42018108835. The search was performed in Pubmed, Medline, LILACS, Scielo, and ScienceDirect databases until May 2019, available in all languages. The search strategy was defined for the PubMed database as a parameter: (neoplasms or cancer) AND (spirituality) AND (pain). Adults patients with cancer of both genders who faced pain were studied. Studies that did not address the pain associated with spirituality were excluded. Of the 588 studies found, 13 were eligible. Among these, nine studies showed that spirituality contributes to positive pain coping. Regarding the level of spirituality, higher spiritual well-being was associated with lower pain intensity in three studies. The spiritual strategies used were mindfulness, meditation, relaxation, prayer, support from religious leaders and members.

CONCLUSION:

Despite the few studies found, the findings broaden the knowledge about the positive relationship between spirituality and pain coping and underline the spiritual strategies for the management of this health condition in cancer patients.

Keywords:

Cancer Pain; Neoplasms; Spirituality

RESUMO

JUSTIFICATIVA E OBJETIVOS:

A relação entre espiritualidade e enfrentamento do câncer ainda é um desafio para o cuidado integral em saúde. Portanto, é necessário analisar se o nível de espiritualidade interfere diretamente nos marcadores clínicos, como na intensidade da dor em pessoas com câncer. O presente estudo teve como objetivo analisar a relação da espiritualidade com o enfrentamento da dor e as estratégias utilizadas em pacientes adultos oncológicos.

CONTEÚDO:

Trata-se de uma revisão sistemática, com registro na base International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews: CRD42018108835. A busca foi realizada nas bases: Pubmed, Medline, LILACS, Scielo e ScienceDirect até maio de 2019, disponíveis em todos os idiomas. A estratégia de pesquisa foi definida para o banco de dados Pubmed como um parâmetro: (neoplasms or cancer) AND (spirituality) AND (pain). Foram estudados adultos com neoplasias, de ambos os sexos, que enfrentam a dor. Os estudos que não abordaram a dor associada à espiritualidade foram excluídos. Foram encontrados 588 estudos, sendo 13 elegíveis. Entre esses, nove estudos mostraram que a espiritualidade contribuiu no enfrentamento positivo da dor. Com relação ao nível de espiritualidade, o maior bem-estar espiritual esteve associado com menor intensidade da dor em três estudos. As estratégias espirituais utilizadas foram, mindfulness, meditação, relaxamento, oração, suporte de líderes e membros religiosos.

CONCLUSÃO:

Apesar dos poucos estudos encontrados, os achados ampliam o conhecimento sobre a relação positiva da espiritualidade com o enfrentamento da dor e evidencia as estratégias espirituais para o manejo dessa condição de saúde em pacientes oncológicos.

Descritores:

Dor do câncer; Espiritualidade; Neoplasias

INTRODUCTION

Neoplasia is the second leading cause of mortality in Brazil, standing behind only to cardiovascular diseases11 Malta DC, Moura L, Prado RR, Escalante JC, Schmidt MI, Duncan BB. Chronic non-communicable disease mortality in Brazil and its regions, 2000-2011. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2014;23(4):599-608.. For people with cancer, the challenge begins with the diagnosis, when negative feelings such as fear, anxiety, depression, hopelessness, and aggressiveness emerge, requiring the reduction of emotional overload, with coping strategies, to achieve psychic rebalancing22 DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Siegel RL, Stein KD, Kramer JL, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(4):252-71.,33 Feldman RS. Introdução à Psicologia. 10ª ed. Porto Alegre; Artmed: 2015. 656p..

Coping is a process by which the individual manages the demands of the person-environment relationship assessed as stressful and the emotions they create, being classified into coping focused on the problem and emotion, although they often occur simultaneously, and can be mutually facilitators44 Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer; 1984.. Among the coping strategies, it is common for cancer patients to adopt religious and spiritual ones to deal with stress, to relieve suffering and increase hope55 Mesquita AC, Chaves Ede C, Avelino CC, Nogueira DA, Panzini RG, de Carvalho EC. The use of religious/spiritual coping among patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy treatment. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2013;21(2):539-45.,66 Bittar CM, Cassiano RL, Silva LN. Espiritualidade e religiosidade como estratégia de enfrentamento do câncer de mama: relato de um grupo de paciente. Mudanças - Psicol Saúde. 2018;26(2):25-31..

Although distinct, spirituality and religiosity are interconnected, since spirituality consists of the human being’s search for the meaning of life, contemplating aspects related to nature, culture, society, among others. Yet, religiosity is characterized by the segment of norms and doctrinal principles defined by an entity, with attitudes of devotion, belief, and effort to live a religious life77 Matos TDS, Meneguin S, Ferreira MLDS, Miot HA. Quality of life and religious-spiritual coping in plliative cancer care patients. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2017;25:e2910..

Spirituality helps people in vulnerable conditions to survive with pain and hold everyday situations by reframing the experiences they live88 Benites AC, Neme CMB, Santos MA. Significados da espiritualidade para pacientes com câncer em cuidados paliativos. Estud Psicol. 2017;34(2):269-79.. Thus, spiritual care allows alleviating cancer pain, which, despite being a physical symptom, encompasses other dimensions, and its effective treatment is not limited to pharmacological therapy. Several contemporary studies have confirmed that spirituality is a determining factor in the health of this population99 Jim HS, Pustejovsky JE, Park CL, Danhauer SC, Sherman AC, Fitchett G, et al. Religion, spirituality, and physical health in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Cancer. 2015;121(21):3760-8.

10 Garssen B, Uwland-Sikkema NF, Visser A. How spirituality helps cancer patients with the adjustment to their disease. J Relig Health. 2015;54(4):1249-65.-1111 Puchalski CM. Spirituality in the cancer trajectory. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 3):49-55..

Cancer patients often experience severe, multifactorial pain associated with the tumor, drugs, and the existence of previous painful conditions. Spirituality influences the resilience capacity to face the illness/death and treatment process1212 Vale CCS, Líbero ACA. A espiritualidade que habita o CTI. Mental. 2017;11(21):321-38.. However, the relationship between spirituality and coping with cancer is still a challenge for comprehensive health care, which is why it is necessary to analyze whether the level of spirituality directly interferes with clinical markers, such as pain intensity.

The guiding questions of this research were: does spirituality appear as a way of coping with pain in adults undergoing cancer treatment? Do different levels of spirituality influence the intensity of the pain? What spiritual strategies are chosen?

Therefore, this study aimed to analyze the relationship between spirituality and coping with pain and to identify the strategies used in adult cancer patients.

CONTENTS

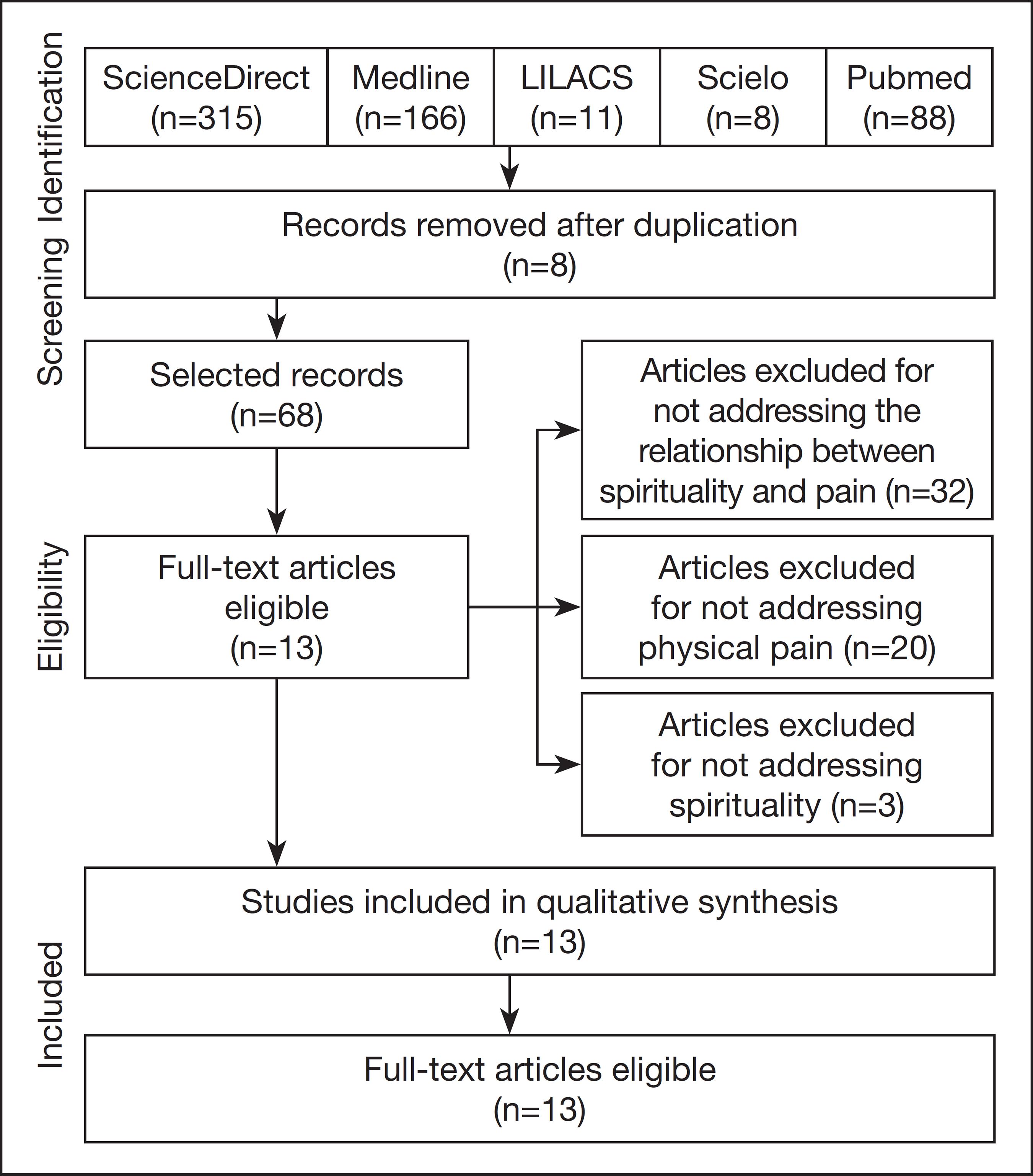

The study was carried out according to the guidelines outlined by PRISMA. Its protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO): CRD42018108835. The Problem-Exposure-Control-Outcome (PECO) strategy was adopted for data collection and analysis.

Searches for articles were carried out in the Pubmed, Medline, LILACS, Scielo, and ScienceDirect databases until May 2019, available in all languages. The search strategy was defined for the Pubmed database as a parameter for the other searched databases. Therefore, the search strategy for Pubmed: (neoplasms or cancer) AND (spirituality) AND (pain).

At first, due to the low number of articles located in this design, clinical trials were chosen as the criterion, it was decided to include observational studies, and the eligibility criteria were: case reports; clinical study; clinical trial; clinical trial, phase I; clinical trial, phase II; clinical trial, phase III; clinical trial, phase IV; comparative study; controlled clinical trial; multicenter study; observational study and pragmatic clinical trial. It was studied adults over 18 years of age, of both genders, with neoplasia and experiencing pain. Studies that did not address the pain associated with spirituality were excluded.

Selection of articles

Two researchers independently searched the databases and, following the proposed criteria, selected the articles. Initially, the selection was based on reading the titles and abstracts, using a standardized spreadsheet method. In a second step, the full text was read, with the subsequent methodological quality assessment. At the end of each stage, the reviewers met and submitted their results for comparison. The discrepancies were discussed, and, in cases where they were not resolved, a third reviewer was consulted to clarify doubts.

Evaluation of the methodological quality

For the assessment of the methodological quality, two reviewers independently used the instrument developed by Loney for cross-sectional studies; the quality criteria defined by authors1313 Warmling D, Lindner SR, Coelho EBS. Intimate partner violence in the elderly and associated factors: systematic review. Cien Saude Colet. 2017;22(9):3111-25. for case report; the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort studies; the check-list proposed by Downs and Black for randomized and non-randomized clinical trials1414 Fernandes PTS, Santana TC, Nogueira AL, Carvalho SF, Bertoncello D. Desenvolvimento neuropsicomotor de recém-nascidos prematuros: uma revisão sistemática. ConScientiae Saúde. 2017;16(4):463-70.,1515 Tomaz-Morais J, Lima JAS de, Luckwu-Lucena BT, Limeira RRT, Silva SM, Alves GA, et al. Clinical intervention studies of orofacial motricity: an analysis of the methodological quality of brazilian studies. Rev CEFAC. 2018;20(3):388-99..

The evaluation of cross-sectional studies consisted of the items sample, source of the sample, sample size, measurement of the outcome, impartial interviewer, response rate, the prevalence with CI95%, and similar participants, in which each appropriate item received a point1313 Warmling D, Lindner SR, Coelho EBS. Intimate partner violence in the elderly and associated factors: systematic review. Cien Saude Colet. 2017;22(9):3111-25.. Studies with seven to eight points were considered of high methodological quality, those with four to six points were of moderate quality, and studies with zero to three points were of low quality. The NOS, consisting of eight items and three dimensions - selection, comparability, and outcome, was developed by Wells to evaluate cohort and case-control studies. The total score can vary from zero to nine stars, where a star corresponds to one point, and two stars can be assigned to the comparability dimension. Studies between six and nine points were considered of high methodological quality, four and five points with moderate quality, and less than four points with low quality1616 Fontela PC, Abdala FANB, Forgiarini SGI, Forgiarini LA Jr. Quality of life in survivors after a period of hospitalization in the intensive care unit: a systematic review. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2018;30(4):496-507.

17 Ribeiro AM, Mateus-Vasconcelos ECL, Silva TD, Brito LGO, Oliveira HF. Functional assessment of the pelvic floor muscles by electromyography: is there a normalization in data analysis? A systematic review. Fisioter Pesqui. 2018;25(1):88-99.-1818 Rocha IS, Lolli LF, Fujimaki M, Gasparetto A, Rocha NBD. Influence of maternal confidence on exclusive breastfeeding until six monts of age: a systematic review. Cien Saude Colet. 2018;23(11):3609-19..

The checklist for randomized and non-randomized clinical trials consists of 27 items with the domains reporting, external validity, bias, selection and power bias, with each item scoring zero or one, except for item five that can score zero, one or two. The studies with a score equal to or greater than 20, were considered of high quality, 15 to 19 of moderate quality and less than or equal to 14 points low quality1414 Fernandes PTS, Santana TC, Nogueira AL, Carvalho SF, Bertoncello D. Desenvolvimento neuropsicomotor de recém-nascidos prematuros: uma revisão sistemática. ConScientiae Saúde. 2017;16(4):463-70.,1515 Tomaz-Morais J, Lima JAS de, Luckwu-Lucena BT, Limeira RRT, Silva SM, Alves GA, et al. Clinical intervention studies of orofacial motricity: an analysis of the methodological quality of brazilian studies. Rev CEFAC. 2018;20(3):388-99..

The evaluation of the case reports was based on the eight proposed items1919 Parente RCM, Oliveira MAP, Celeste RK. Relatos e série de casos na era da medicina baseada em evidência. Bras J Video-Sur. 2010;3(2):67-70.. The items involve diagnosis, consent, approval by the ethics committee, details of the intervention, relevant clinical outcomes, patient perception, associated risks, eligibility criteria. Each item received one point when met, which are stratified at cut points equal to those of cross-sectional studies in high, medium, and low methodological quality. The scores obtained in the instruments were not used as an exclusion criterion for the articles but as indicators of the methodological quality of the studies.

Characteristics of the studies

Figure 1 summarizes the search process and the identification of relevant studies. The electronic search strategy retrieved 588 studies; of these, 512 were excluded after reading the title and abstract for not meeting the eligibility criteria, and eight for being duplicated. Thus, the full analysis of 68 studies was carried out, and of that process, 13 studies2020 Edman JS, Roberts RS, Dusek JA, Dolor R, Wolever RQ, Abrams DI. Characteristics of cancer patients presenting to an integrative medicine practice-based research networn. Integr Cancer Ther. 2014;13(5):405-10.

21 Silva JO, Araújo VM, Cardoso BG, Cardoso MG. Spiritual dimension of pain and suffering control of advanced cancer patient. Case report. Rev Dor. 2015;16(1):71-4.

22 Jafari N, Farajzadegan Z, Zamani A, Bahrami F, Emami H, Loghmani A, et al. Spiritual therapy to improve the spiritual well-being of iranian women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:353262.

23 Rabow MW, Knish SJ. Spiritual well-being among outpatients with cancer receiving concurrent oncologic and palliative care. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(4):919-23.

24 Buck HG, Meghani SH. Spiritual expressions of African Americans and whites in cancer pain. J Holist Nurs. 2012;30(2):107-16.

25 Bai J, Brubaker A, Meghani SH, Bruner DW, Yeager KA. Spirituality and quality of life in black patients with cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(3):390-8.

26 Zavala MW, Maliski SL, Kwan L, Fink A, Litwin MS. Spirituality and quality of life in low-income men with metastatic prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18(7):753-61.

27 Ando M, Morita T, Akechi T, Ito S, Tanaka M, Ifuku Y, et al. The efficacy of mindfulness-based meditation therapy on anxiety, depression, and spirituality in Japanese patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(12):1091-4.

28 Visser A, de Jager Meezenbroek EC, Garssen B. Does spirituality reduce the impact of somatic symptoms on distress in cancer patients? cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. Soc Sci Med. 2018;214:57-66.

29 Mystakidou K, Tsilika E, Parpa E, Pathiaki M, Patiraki E, Galanos A, et al. Exploring the relationships between depression, hopelessness, cognitive status, pain, and spirituality in patients with advanced cancer. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2007;21(3):150-61.

30 Jagannathan A, Juvva S. Life after cancer in India: coping with side effects and cancer pain. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2009;27(3):344-60.

31 Furlan M, Bernardi J, Vieira AM, Santos MCC, Marcon SS. Percepção de mulheres submetidas à mastectomia sobre o apoio social. Ciência Cuid e Saúde. 2012;11(1):66-73.-3232 Gielen J, Bhatnagar S, Chaturvedi SK. Prevalence and nature of spiritual distress among palliative care patients in India. J Relig Health. 2017;56(2):530-44. met the eligibility criteria and were included in the review.

The 13 articles included were published from 2007 to 2018, mostly between 2012 and 2018. There was a higher concentration of studies in the United States2020 Edman JS, Roberts RS, Dusek JA, Dolor R, Wolever RQ, Abrams DI. Characteristics of cancer patients presenting to an integrative medicine practice-based research networn. Integr Cancer Ther. 2014;13(5):405-10.,2323 Rabow MW, Knish SJ. Spiritual well-being among outpatients with cancer receiving concurrent oncologic and palliative care. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(4):919-23.

24 Buck HG, Meghani SH. Spiritual expressions of African Americans and whites in cancer pain. J Holist Nurs. 2012;30(2):107-16.

25 Bai J, Brubaker A, Meghani SH, Bruner DW, Yeager KA. Spirituality and quality of life in black patients with cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(3):390-8.-2626 Zavala MW, Maliski SL, Kwan L, Fink A, Litwin MS. Spirituality and quality of life in low-income men with metastatic prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18(7):753-61.. The sample size varied between 1 and 883 participants. The average ages were from 43 to 65 years; in nine studies(20,23-25,27-30,32 )where the participants were men and women, and in the others only women. Regarding the design, nine studies are cross-sectional2323 Rabow MW, Knish SJ. Spiritual well-being among outpatients with cancer receiving concurrent oncologic and palliative care. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(4):919-23.

24 Buck HG, Meghani SH. Spiritual expressions of African Americans and whites in cancer pain. J Holist Nurs. 2012;30(2):107-16.

25 Bai J, Brubaker A, Meghani SH, Bruner DW, Yeager KA. Spirituality and quality of life in black patients with cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(3):390-8.-2626 Zavala MW, Maliski SL, Kwan L, Fink A, Litwin MS. Spirituality and quality of life in low-income men with metastatic prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18(7):753-61.,2828 Visser A, de Jager Meezenbroek EC, Garssen B. Does spirituality reduce the impact of somatic symptoms on distress in cancer patients? cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. Soc Sci Med. 2018;214:57-66.

29 Mystakidou K, Tsilika E, Parpa E, Pathiaki M, Patiraki E, Galanos A, et al. Exploring the relationships between depression, hopelessness, cognitive status, pain, and spirituality in patients with advanced cancer. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2007;21(3):150-61.

30 Jagannathan A, Juvva S. Life after cancer in India: coping with side effects and cancer pain. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2009;27(3):344-60.

31 Furlan M, Bernardi J, Vieira AM, Santos MCC, Marcon SS. Percepção de mulheres submetidas à mastectomia sobre o apoio social. Ciência Cuid e Saúde. 2012;11(1):66-73.-3232 Gielen J, Bhatnagar S, Chaturvedi SK. Prevalence and nature of spiritual distress among palliative care patients in India. J Relig Health. 2017;56(2):530-44.; two are clinical trials2222 Jafari N, Farajzadegan Z, Zamani A, Bahrami F, Emami H, Loghmani A, et al. Spiritual therapy to improve the spiritual well-being of iranian women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:353262.,2727 Ando M, Morita T, Akechi T, Ito S, Tanaka M, Ifuku Y, et al. The efficacy of mindfulness-based meditation therapy on anxiety, depression, and spirituality in Japanese patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(12):1091-4.; one is a case study2121 Silva JO, Araújo VM, Cardoso BG, Cardoso MG. Spiritual dimension of pain and suffering control of advanced cancer patient. Case report. Rev Dor. 2015;16(1):71-4. and two are cohort studies2020 Edman JS, Roberts RS, Dusek JA, Dolor R, Wolever RQ, Abrams DI. Characteristics of cancer patients presenting to an integrative medicine practice-based research networn. Integr Cancer Ther. 2014;13(5):405-10.,2828 Visser A, de Jager Meezenbroek EC, Garssen B. Does spirituality reduce the impact of somatic symptoms on distress in cancer patients? cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. Soc Sci Med. 2018;214:57-66.. As for the place of selection of the participants, most were selected in a hospital2222 Jafari N, Farajzadegan Z, Zamani A, Bahrami F, Emami H, Loghmani A, et al. Spiritual therapy to improve the spiritual well-being of iranian women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:353262.,2525 Bai J, Brubaker A, Meghani SH, Bruner DW, Yeager KA. Spirituality and quality of life in black patients with cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(3):390-8.,2727 Ando M, Morita T, Akechi T, Ito S, Tanaka M, Ifuku Y, et al. The efficacy of mindfulness-based meditation therapy on anxiety, depression, and spirituality in Japanese patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(12):1091-4.

28 Visser A, de Jager Meezenbroek EC, Garssen B. Does spirituality reduce the impact of somatic symptoms on distress in cancer patients? cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. Soc Sci Med. 2018;214:57-66.

29 Mystakidou K, Tsilika E, Parpa E, Pathiaki M, Patiraki E, Galanos A, et al. Exploring the relationships between depression, hopelessness, cognitive status, pain, and spirituality in patients with advanced cancer. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2007;21(3):150-61.-3030 Jagannathan A, Juvva S. Life after cancer in India: coping with side effects and cancer pain. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2009;27(3):344-60.,3232 Gielen J, Bhatnagar S, Chaturvedi SK. Prevalence and nature of spiritual distress among palliative care patients in India. J Relig Health. 2017;56(2):530-44.. Table 1 shows the characteristics of these studies.

Among the studies evaluated by the instrument proposed by Loney, four2626 Zavala MW, Maliski SL, Kwan L, Fink A, Litwin MS. Spirituality and quality of life in low-income men with metastatic prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18(7):753-61.,2828 Visser A, de Jager Meezenbroek EC, Garssen B. Does spirituality reduce the impact of somatic symptoms on distress in cancer patients? cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. Soc Sci Med. 2018;214:57-66.,2929 Mystakidou K, Tsilika E, Parpa E, Pathiaki M, Patiraki E, Galanos A, et al. Exploring the relationships between depression, hopelessness, cognitive status, pain, and spirituality in patients with advanced cancer. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2007;21(3):150-61.,3232 Gielen J, Bhatnagar S, Chaturvedi SK. Prevalence and nature of spiritual distress among palliative care patients in India. J Relig Health. 2017;56(2):530-44. achieved moderate methodological quality; five2323 Rabow MW, Knish SJ. Spiritual well-being among outpatients with cancer receiving concurrent oncologic and palliative care. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(4):919-23.

24 Buck HG, Meghani SH. Spiritual expressions of African Americans and whites in cancer pain. J Holist Nurs. 2012;30(2):107-16.-2525 Bai J, Brubaker A, Meghani SH, Bruner DW, Yeager KA. Spirituality and quality of life in black patients with cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(3):390-8.,3030 Jagannathan A, Juvva S. Life after cancer in India: coping with side effects and cancer pain. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2009;27(3):344-60.,3131 Furlan M, Bernardi J, Vieira AM, Santos MCC, Marcon SS. Percepção de mulheres submetidas à mastectomia sobre o apoio social. Ciência Cuid e Saúde. 2012;11(1):66-73. obtained low quality. As for the studies analyzed by the NOS, both2525 Bai J, Brubaker A, Meghani SH, Bruner DW, Yeager KA. Spirituality and quality of life in black patients with cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(3):390-8.,2828 Visser A, de Jager Meezenbroek EC, Garssen B. Does spirituality reduce the impact of somatic symptoms on distress in cancer patients? cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. Soc Sci Med. 2018;214:57-66. presented moderate quality. The clinical trials2222 Jafari N, Farajzadegan Z, Zamani A, Bahrami F, Emami H, Loghmani A, et al. Spiritual therapy to improve the spiritual well-being of iranian women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:353262.,2727 Ando M, Morita T, Akechi T, Ito S, Tanaka M, Ifuku Y, et al. The efficacy of mindfulness-based meditation therapy on anxiety, depression, and spirituality in Japanese patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(12):1091-4. evaluated by the Downs and Black checklist showed low and moderate methodological quality (Table 2). The most used instrument to measure spirituality was the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy - Spiritual Well-Being - FACIT-Sp2222 Jafari N, Farajzadegan Z, Zamani A, Bahrami F, Emami H, Loghmani A, et al. Spiritual therapy to improve the spiritual well-being of iranian women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:353262.,2525 Bai J, Brubaker A, Meghani SH, Bruner DW, Yeager KA. Spirituality and quality of life in black patients with cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(3):390-8.

26 Zavala MW, Maliski SL, Kwan L, Fink A, Litwin MS. Spirituality and quality of life in low-income men with metastatic prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18(7):753-61.-2727 Ando M, Morita T, Akechi T, Ito S, Tanaka M, Ifuku Y, et al. The efficacy of mindfulness-based meditation therapy on anxiety, depression, and spirituality in Japanese patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(12):1091-4., and the numerical scale was used to assess pain2020 Edman JS, Roberts RS, Dusek JA, Dolor R, Wolever RQ, Abrams DI. Characteristics of cancer patients presenting to an integrative medicine practice-based research networn. Integr Cancer Ther. 2014;13(5):405-10.,2727 Ando M, Morita T, Akechi T, Ito S, Tanaka M, Ifuku Y, et al. The efficacy of mindfulness-based meditation therapy on anxiety, depression, and spirituality in Japanese patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(12):1091-4.,3232 Gielen J, Bhatnagar S, Chaturvedi SK. Prevalence and nature of spiritual distress among palliative care patients in India. J Relig Health. 2017;56(2):530-44.. A semi-structured interview was used to assess both spirituality and pain in three studies2424 Buck HG, Meghani SH. Spiritual expressions of African Americans and whites in cancer pain. J Holist Nurs. 2012;30(2):107-16.,3030 Jagannathan A, Juvva S. Life after cancer in India: coping with side effects and cancer pain. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2009;27(3):344-60.,3131 Furlan M, Bernardi J, Vieira AM, Santos MCC, Marcon SS. Percepção de mulheres submetidas à mastectomia sobre o apoio social. Ciência Cuid e Saúde. 2012;11(1):66-73.(Table 2).

The relationship between spirituality and pain was significant in six studies. Nine studies2121 Silva JO, Araújo VM, Cardoso BG, Cardoso MG. Spiritual dimension of pain and suffering control of advanced cancer patient. Case report. Rev Dor. 2015;16(1):71-4.

22 Jafari N, Farajzadegan Z, Zamani A, Bahrami F, Emami H, Loghmani A, et al. Spiritual therapy to improve the spiritual well-being of iranian women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:353262.-2323 Rabow MW, Knish SJ. Spiritual well-being among outpatients with cancer receiving concurrent oncologic and palliative care. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(4):919-23.,2525 Bai J, Brubaker A, Meghani SH, Bruner DW, Yeager KA. Spirituality and quality of life in black patients with cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(3):390-8.

26 Zavala MW, Maliski SL, Kwan L, Fink A, Litwin MS. Spirituality and quality of life in low-income men with metastatic prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18(7):753-61.

27 Ando M, Morita T, Akechi T, Ito S, Tanaka M, Ifuku Y, et al. The efficacy of mindfulness-based meditation therapy on anxiety, depression, and spirituality in Japanese patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(12):1091-4.-2828 Visser A, de Jager Meezenbroek EC, Garssen B. Does spirituality reduce the impact of somatic symptoms on distress in cancer patients? cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. Soc Sci Med. 2018;214:57-66.,3131 Furlan M, Bernardi J, Vieira AM, Santos MCC, Marcon SS. Percepção de mulheres submetidas à mastectomia sobre o apoio social. Ciência Cuid e Saúde. 2012;11(1):66-73.,3232 Gielen J, Bhatnagar S, Chaturvedi SK. Prevalence and nature of spiritual distress among palliative care patients in India. J Relig Health. 2017;56(2):530-44. showed that spirituality contributes to the positive coping of pain. Only one2929 Mystakidou K, Tsilika E, Parpa E, Pathiaki M, Patiraki E, Galanos A, et al. Exploring the relationships between depression, hopelessness, cognitive status, pain, and spirituality in patients with advanced cancer. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2007;21(3):150-61. sought correlations between spirituality and pain, but without significant results. Three studies2020 Edman JS, Roberts RS, Dusek JA, Dolor R, Wolever RQ, Abrams DI. Characteristics of cancer patients presenting to an integrative medicine practice-based research networn. Integr Cancer Ther. 2014;13(5):405-10.,2424 Buck HG, Meghani SH. Spiritual expressions of African Americans and whites in cancer pain. J Holist Nurs. 2012;30(2):107-16.,3030 Jagannathan A, Juvva S. Life after cancer in India: coping with side effects and cancer pain. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2009;27(3):344-60. suggested that the profile of cancer patients with pain who seek spirituality is more related to social class and ethnicity (Table 3).

Due to the heterogeneity of the data, it was not possible to perform quantitative analyzes of the studies. Regarding the level of spirituality, greater spiritual well-being was associated with less pain intensity in three studies. The reduction in pain intensity measured quantitatively by the visual analog scale (VAS) was evidenced only in one study. The two experimental studies2222 Jafari N, Farajzadegan Z, Zamani A, Bahrami F, Emami H, Loghmani A, et al. Spiritual therapy to improve the spiritual well-being of iranian women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:353262.,2727 Ando M, Morita T, Akechi T, Ito S, Tanaka M, Ifuku Y, et al. The efficacy of mindfulness-based meditation therapy on anxiety, depression, and spirituality in Japanese patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(12):1091-4. aimed at showing whether the type of spiritual strategy used would be effective in reducing pain intensity, pointing out that mindfulness and Spiritual Therapy programs, composed of meditation and relaxation, were strategies that promoted pain relief.

In this summary of the literature data on the relationship between spirituality and coping with pain in cancer patients, we sought to analyze spiritual strategies with evidence for pain management in this health condition. Few studies fill this gap, most of them with cross-sectional design and low to moderate methodological quality. However, most authors admit that positive spiritual strategies have a beneficial effect on pain control in cancer patients.

Only three studies showed statistical differences between groups that use spiritual strategies and those that only adopt biomedical behaviors. The lack of homogeneity in the studies prevented the use of metanalysis for their assessment. However, most studies on the topic are still in the observation phase. It is necessary to move towards clinical trials that can test hypotheses in a controlled manner. The few findings, so far, point to promising results for the recommendation of its indication in health services in addition to religious institutions. Meditation practices and body relaxation techniques have been adopted with positive results99 Jim HS, Pustejovsky JE, Park CL, Danhauer SC, Sherman AC, Fitchett G, et al. Religion, spirituality, and physical health in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Cancer. 2015;121(21):3760-8.,2727 Ando M, Morita T, Akechi T, Ito S, Tanaka M, Ifuku Y, et al. The efficacy of mindfulness-based meditation therapy on anxiety, depression, and spirituality in Japanese patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(12):1091-4.,3333 Puchalski CM. Caregiver stress: the role of spirituality in the lives of family/friends and professional caregivers of cancer patients. 2012. 201-28p., even though they lack methodological standardization.

Social class and ethnicity seem to influence the choice of using spiritual strategies to cope with pain in this health condition. Afro-descendant groups have a rich culture of spiritual rites and practices2424 Buck HG, Meghani SH. Spiritual expressions of African Americans and whites in cancer pain. J Holist Nurs. 2012;30(2):107-16.,3434 Chibnall JT, Bennett ML, Videen SD, Duckro PN, Miller DK. Identifying barriers to psychosocial spiritual care at the end of life: A physician group study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2004;21(6):419-26.. However, the lack of education, socioeconomic factors, and the lack of other resources, such as the absence of more potent painkillers due to the high cost, lead these people to seek spiritual strategies as the only alternative. In any case, it is worth mentioning that the lack of alternatives can lead people with cancer pain to find an effective resource to deal with the problem.

Spiritual strategies, such as meditation and relaxation practices, are increasingly common in contemporary health systems. However, people with less education and unfavorable socioeconomic conditions are unaware of these types of services3030 Jagannathan A, Juvva S. Life after cancer in India: coping with side effects and cancer pain. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2009;27(3):344-60.,3535 Lucchetti G, Bassi RM, Lucchetti AL. Taking spiritual history in clinical practice: a systematic review of instruments. Explore. 2013;9(3):159-70.. It is known that spiritual practice is related to physiological responses in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, by reducing the adrenocorticotrophic hormone and cortisol, and consequently reducing stress, which may be related to pain3636 Lago-Rizzardi C, Teixeira M, Siqueira SR. Espiritualidade e religiosidade no enfrentamento da dor. O Mundo da Saúde. 2010;34(4):483-7..

The choice to use a spiritual activity is very personal and is related to the system of beliefs, values, customs, behaviors, and sociocultural attitudes3737 Monteiro LVB, Rocha Junior JR. A dimensão espiritual na compreensão do processo saúde-doença em psicologia da saúde. Ciências Biológicas e de Saúde Unit. 2017;4(2):15-30.. When comparing cancer patients who sought integrative medicine and the inclusion of spiritual practices as part of the treatment with those who did not want this aspect of care, it was found that patients who sought the service for spiritual reasons had more pain, depression, and stress than the other group2020 Edman JS, Roberts RS, Dusek JA, Dolor R, Wolever RQ, Abrams DI. Characteristics of cancer patients presenting to an integrative medicine practice-based research networn. Integr Cancer Ther. 2014;13(5):405-10.. It is possible that, while pain is at the limit of control with other approaches, spirituality is disregarded, only entering the list of choices when the situation is already out of control.

The advanced clinical stage in cancer causes spiritual conflicts3838 Reticena Kde O, Beuter M, Sales CA. Life experiences of elderly with cancer pain: the existential comprehensive approach. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2015;49(3):419-25., which naturally leads to the search for spirituality to alleviate this feeling and improve the quality of life3939 Lee YP, Wu CH, Chiu TY, Chen CY, Morita T, Hung SH, et al. The relationship between pain management and psychospiritual distress in patients with advanced cancer following admission to a palliative care unit. BMC Palliat Care. 2015;14:69.. Spiritual coping strategies have been identified as beneficial for people in pain, being associated with greater tolerance, better mood, and well-being4040 Siddall PJ, Lovell M, MacLeod R. Spirituality: what is its role in pain medicine? Pain Med. 2015;16(1):51-60.. The findings of the present study confirm the hypothesis that spiritual practices are linked to the search for solutions when ill, in an attempt to relieve the suffering created by the disease, which may be based on their beliefs, regardless of religion; they consider that these strategies are of daily use, such as going to church, relying on family and friends, praying, reading the Bible, among others4141 Barbosa RM, Ferreira JLP, Melo MCB, Costa JM. A espiritualidade como estratégia de enfrentamento para familiares de pacientes adultos em cuidados paliativos. Rev SBPH. 2017;20(1):165-82..

Unfortunately, many studies that address the topic have a typical conflict of interest of being carried out by practitioners and leaders of a specific religion or philosophy. Reading religious texts on the “word of God” or specific hymns and cults can create resistance on the part of unbelieving patients or those belonging to a different faith system. Many dogmas can clash with one another. Therefore, spirituality should not be a synonym for religion4242 Lifshitz M, van Elk M, Luhrmann TM. Absorption and spiritual experience: a review of evidence and potential mechanisms. Conscious Cogn. 2019;73:102760.. Religion is dogmatic; however, aspects such as optimism, hope, resilience, acceptance, among others, are more related to high levels of spirituality. Higher levels of spirituality can be obtained both in religious paths and in spiritual practices4343 Balboni TA, Balboni MJ. The spiritual event of serious illness. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(5):816-22.,4444 Egan R, MacLeod R, Jaye C, McGee R, Baxter J, Herbison P. What is spirituality? Evidence from a New Zealand hospice study. Mortality. 201116(4):307-24..

Important spiritual strategies were revealed when exploring the relationship of coping with pain through spirituality, the main ones being meditation and relaxation techniques. Spiritual strategies are those activities that seek to strengthen the meaning of life, faith or existential components, peace with oneself, and with others4545 Phenwan T, Peerawong T, Tulathamkij K. The meaning of spirituality and spiritual well-being among thai breast cancer patients: a qualitative study. Indian J Palliat Care. 2019;25(1):119-23.. Patients resort to different practices as needed. However, it is clear that mindfulness, meditation, and prayer are the most used to bring a feeling of comfort and strength4646 Worthington D, Deuster PA. Spiritual titness: an essential component of human performance optimization. J Spec Oper Med. 2018;18(1):100-5..

Meditation is an effective strategy in stressful situations, such as cancer diagnosis and treatment. Among the various techniques, mindfulness stands out, which seeks to concentrate on a reference point through breathing, movements, body sensations, or mantras4747 Pokorski M, Suchorzynska A. Psychobehavioral effects of Meditation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1023(1):85-91.. A non-randomized clinical trial showed that the use of this meditation was a beneficial strategy to improve spiritual well-being and reducing the intensity of pain2222 Jafari N, Farajzadegan Z, Zamani A, Bahrami F, Emami H, Loghmani A, et al. Spiritual therapy to improve the spiritual well-being of iranian women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:353262.. In addition to meditation itself, relaxation techniques have also been effective in controlling pain in mastectomized women2222 Jafari N, Farajzadegan Z, Zamani A, Bahrami F, Emami H, Loghmani A, et al. Spiritual therapy to improve the spiritual well-being of iranian women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:353262.. The lack of quantification of pain in that study creates an absence of evidence. For this reason, further studies should be conducted to provide the necessary support for the incorporation of this practice by health teams.

In one of the selected studies, cancer patients undergoing mastectomy sought support from religious leaders and members3131 Furlan M, Bernardi J, Vieira AM, Santos MCC, Marcon SS. Percepção de mulheres submetidas à mastectomia sobre o apoio social. Ciência Cuid e Saúde. 2012;11(1):66-73.. In India, the lowest income population used firm faith in the doctor, praying, and meditation as a strategy to cope with pain while those with the highest income kept with conventional treatment with the use of drugs3030 Jagannathan A, Juvva S. Life after cancer in India: coping with side effects and cancer pain. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2009;27(3):344-60.. It is likely that personal belief in an external entity, be it the doctor or God, may favor self-regulatory processes4848 Visser A, Garssen B, Vingerhoets A. Spirituality and well-being in cancer patients: a review. Psychooncology. 201019(6):565-72..

Pain is a common physical symptom in cancer patients, which can go beyond the psychosocial dimension. Traditional treatment consists of using analgesic and opioid drugs to relieve physical symptoms, although psychological conflicts are capable of interfering with pain control3838 Reticena Kde O, Beuter M, Sales CA. Life experiences of elderly with cancer pain: the existential comprehensive approach. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2015;49(3):419-25.. Pain intensity is greater in anguished cancer patients when compared to those who trust in the future and God, corroborating that spirituality is a good mechanism for coping with pain3232 Gielen J, Bhatnagar S, Chaturvedi SK. Prevalence and nature of spiritual distress among palliative care patients in India. J Relig Health. 2017;56(2):530-44..

In the case report analyzed2121 Silva JO, Araújo VM, Cardoso BG, Cardoso MG. Spiritual dimension of pain and suffering control of advanced cancer patient. Case report. Rev Dor. 2015;16(1):71-4., whose goal was to present the integration of spiritual aspects to the health and disease process of a female patient with pancreatic cancer, evangelical and former “mãe de santo” (a religious leader of some African-Brazilian religions) for 27 years. She realized that the use of painkillers, together with reading the Bible, prayer, and meditation, influenced the reduction of pain. The intensity was reduced from level seven to nine to level zero after follow-up. However, the pain returned influenced by the chronic nature of the disease and by the existence of spiritual and family conflicts, after spiritual assistance by a multidisciplinary team. Even so, the pain remained controlled and, later, the patient died calmly and peacefully. Although one case study does not contribute with evidence, they are important as initial exploratory studies that can point the way to prospective studies. Nonetheless, this case represents another confirmation of the impact of spirituality on cancer patients’ pain.

The important limitation pointed out in the present review is directed to the low amount of scientific studies on the theme involving spirituality and pain in cancer patients. Moreover, the methodological quality of most studies was considered low. However, it is worth mentioning that the review strictly followed the current recommendations for the preparation of systematic reviews, which supports the robustness of the results. It is important to carry out new studies with experimental design and representative samples to investigate the effect of spirituality on cancer patients’ pain.

CONCLUSION

The present study expanded the knowledge about the relationship between spirituality and pain treatment in cancer patients, encouraging patients, health professionals, caregivers, and family members to adopt spiritual strategies.

REFERENCES

-

1Malta DC, Moura L, Prado RR, Escalante JC, Schmidt MI, Duncan BB. Chronic non-communicable disease mortality in Brazil and its regions, 2000-2011. Epidemiol Serv Saúde. 2014;23(4):599-608.

-

2DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Siegel RL, Stein KD, Kramer JL, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(4):252-71.

-

3Feldman RS. Introdução à Psicologia. 10ª ed. Porto Alegre; Artmed: 2015. 656p.

-

4Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer; 1984.

-

5Mesquita AC, Chaves Ede C, Avelino CC, Nogueira DA, Panzini RG, de Carvalho EC. The use of religious/spiritual coping among patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy treatment. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2013;21(2):539-45.

-

6Bittar CM, Cassiano RL, Silva LN. Espiritualidade e religiosidade como estratégia de enfrentamento do câncer de mama: relato de um grupo de paciente. Mudanças - Psicol Saúde. 2018;26(2):25-31.

-

7Matos TDS, Meneguin S, Ferreira MLDS, Miot HA. Quality of life and religious-spiritual coping in plliative cancer care patients. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2017;25:e2910.

-

8Benites AC, Neme CMB, Santos MA. Significados da espiritualidade para pacientes com câncer em cuidados paliativos. Estud Psicol. 2017;34(2):269-79.

-

9Jim HS, Pustejovsky JE, Park CL, Danhauer SC, Sherman AC, Fitchett G, et al. Religion, spirituality, and physical health in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Cancer. 2015;121(21):3760-8.

-

10Garssen B, Uwland-Sikkema NF, Visser A. How spirituality helps cancer patients with the adjustment to their disease. J Relig Health. 2015;54(4):1249-65.

-

11Puchalski CM. Spirituality in the cancer trajectory. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 3):49-55.

-

12Vale CCS, Líbero ACA. A espiritualidade que habita o CTI. Mental. 2017;11(21):321-38.

-

13Warmling D, Lindner SR, Coelho EBS. Intimate partner violence in the elderly and associated factors: systematic review. Cien Saude Colet. 2017;22(9):3111-25.

-

14Fernandes PTS, Santana TC, Nogueira AL, Carvalho SF, Bertoncello D. Desenvolvimento neuropsicomotor de recém-nascidos prematuros: uma revisão sistemática. ConScientiae Saúde. 2017;16(4):463-70.

-

15Tomaz-Morais J, Lima JAS de, Luckwu-Lucena BT, Limeira RRT, Silva SM, Alves GA, et al. Clinical intervention studies of orofacial motricity: an analysis of the methodological quality of brazilian studies. Rev CEFAC. 2018;20(3):388-99.

-

16Fontela PC, Abdala FANB, Forgiarini SGI, Forgiarini LA Jr. Quality of life in survivors after a period of hospitalization in the intensive care unit: a systematic review. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2018;30(4):496-507.

-

17Ribeiro AM, Mateus-Vasconcelos ECL, Silva TD, Brito LGO, Oliveira HF. Functional assessment of the pelvic floor muscles by electromyography: is there a normalization in data analysis? A systematic review. Fisioter Pesqui. 2018;25(1):88-99.

-

18Rocha IS, Lolli LF, Fujimaki M, Gasparetto A, Rocha NBD. Influence of maternal confidence on exclusive breastfeeding until six monts of age: a systematic review. Cien Saude Colet. 2018;23(11):3609-19.

-

19Parente RCM, Oliveira MAP, Celeste RK. Relatos e série de casos na era da medicina baseada em evidência. Bras J Video-Sur. 2010;3(2):67-70.

-

20Edman JS, Roberts RS, Dusek JA, Dolor R, Wolever RQ, Abrams DI. Characteristics of cancer patients presenting to an integrative medicine practice-based research networn. Integr Cancer Ther. 2014;13(5):405-10.

-

21Silva JO, Araújo VM, Cardoso BG, Cardoso MG. Spiritual dimension of pain and suffering control of advanced cancer patient. Case report. Rev Dor. 2015;16(1):71-4.

-

22Jafari N, Farajzadegan Z, Zamani A, Bahrami F, Emami H, Loghmani A, et al. Spiritual therapy to improve the spiritual well-being of iranian women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:353262.

-

23Rabow MW, Knish SJ. Spiritual well-being among outpatients with cancer receiving concurrent oncologic and palliative care. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(4):919-23.

-

24Buck HG, Meghani SH. Spiritual expressions of African Americans and whites in cancer pain. J Holist Nurs. 2012;30(2):107-16.

-

25Bai J, Brubaker A, Meghani SH, Bruner DW, Yeager KA. Spirituality and quality of life in black patients with cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(3):390-8.

-

26Zavala MW, Maliski SL, Kwan L, Fink A, Litwin MS. Spirituality and quality of life in low-income men with metastatic prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18(7):753-61.

-

27Ando M, Morita T, Akechi T, Ito S, Tanaka M, Ifuku Y, et al. The efficacy of mindfulness-based meditation therapy on anxiety, depression, and spirituality in Japanese patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(12):1091-4.

-

28Visser A, de Jager Meezenbroek EC, Garssen B. Does spirituality reduce the impact of somatic symptoms on distress in cancer patients? cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. Soc Sci Med. 2018;214:57-66.

-

29Mystakidou K, Tsilika E, Parpa E, Pathiaki M, Patiraki E, Galanos A, et al. Exploring the relationships between depression, hopelessness, cognitive status, pain, and spirituality in patients with advanced cancer. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2007;21(3):150-61.

-

30Jagannathan A, Juvva S. Life after cancer in India: coping with side effects and cancer pain. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2009;27(3):344-60.

-

31Furlan M, Bernardi J, Vieira AM, Santos MCC, Marcon SS. Percepção de mulheres submetidas à mastectomia sobre o apoio social. Ciência Cuid e Saúde. 2012;11(1):66-73.

-

32Gielen J, Bhatnagar S, Chaturvedi SK. Prevalence and nature of spiritual distress among palliative care patients in India. J Relig Health. 2017;56(2):530-44.

-

33Puchalski CM. Caregiver stress: the role of spirituality in the lives of family/friends and professional caregivers of cancer patients. 2012. 201-28p.

-

34Chibnall JT, Bennett ML, Videen SD, Duckro PN, Miller DK. Identifying barriers to psychosocial spiritual care at the end of life: A physician group study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2004;21(6):419-26.

-

35Lucchetti G, Bassi RM, Lucchetti AL. Taking spiritual history in clinical practice: a systematic review of instruments. Explore. 2013;9(3):159-70.

-

36Lago-Rizzardi C, Teixeira M, Siqueira SR. Espiritualidade e religiosidade no enfrentamento da dor. O Mundo da Saúde. 2010;34(4):483-7.

-

37Monteiro LVB, Rocha Junior JR. A dimensão espiritual na compreensão do processo saúde-doença em psicologia da saúde. Ciências Biológicas e de Saúde Unit. 2017;4(2):15-30.

-

38Reticena Kde O, Beuter M, Sales CA. Life experiences of elderly with cancer pain: the existential comprehensive approach. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2015;49(3):419-25.

-

39Lee YP, Wu CH, Chiu TY, Chen CY, Morita T, Hung SH, et al. The relationship between pain management and psychospiritual distress in patients with advanced cancer following admission to a palliative care unit. BMC Palliat Care. 2015;14:69.

-

40Siddall PJ, Lovell M, MacLeod R. Spirituality: what is its role in pain medicine? Pain Med. 2015;16(1):51-60.

-

41Barbosa RM, Ferreira JLP, Melo MCB, Costa JM. A espiritualidade como estratégia de enfrentamento para familiares de pacientes adultos em cuidados paliativos. Rev SBPH. 2017;20(1):165-82.

-

42Lifshitz M, van Elk M, Luhrmann TM. Absorption and spiritual experience: a review of evidence and potential mechanisms. Conscious Cogn. 2019;73:102760.

-

43Balboni TA, Balboni MJ. The spiritual event of serious illness. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56(5):816-22.

-

44Egan R, MacLeod R, Jaye C, McGee R, Baxter J, Herbison P. What is spirituality? Evidence from a New Zealand hospice study. Mortality. 201116(4):307-24.

-

45Phenwan T, Peerawong T, Tulathamkij K. The meaning of spirituality and spiritual well-being among thai breast cancer patients: a qualitative study. Indian J Palliat Care. 2019;25(1):119-23.

-

46Worthington D, Deuster PA. Spiritual titness: an essential component of human performance optimization. J Spec Oper Med. 2018;18(1):100-5.

-

47Pokorski M, Suchorzynska A. Psychobehavioral effects of Meditation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1023(1):85-91.

-

48Visser A, Garssen B, Vingerhoets A. Spirituality and well-being in cancer patients: a review. Psychooncology. 201019(6):565-72.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

08 June 2020 -

Date of issue

Jan-Mar 2020

History

-

Received

01 Oct 2019 -

Accepted

15 Mar 2020