ABSTRACT

Palms may be an important source of renewable raw material to replace wood, however, the uses of the stems of native species of the Brazil are known only at the local or regional level. We carried out a literature review on the traditional knowledge of the uses of the stems of palm species native to the Amazon biome in Brazil, and related the types of uses with morphological characteristics of the stems. The review resulted in information on 45 species with solitary or cespitose stems, and six stem-size types: tall (15 species), medium-short (3), medium (5), small (17), acaulescent (1) and climbing (4). We found 80 indications of stem use in seven categories and 14 subcategories. A similarity analysis showed that, in general, tall, medium-short, medium, small (≥ 10 cm in diameter) and climbing stem types, solitary or cespitous, are used for construction, furniture, handicrafts, utensils, tools and musical instruments. Only small stems (< 10 cm diameter) are used to manufacture weapons for hunting and fishing, and climbing stems are used in the manufacture of ropes. Stems of Socratea exorrhiza, Euterpe oleracea and Desmoncus polyacanthos are the most frequently used to meet subsistence needs in traditional communities in the Brazilian Amazon. Our findings indicate that there is a potential for use of several native palm stems as sources for alternative materials in the manufacture industry and as sustainable income sources for Amazonian communities.

KEYWORDS:

Arecaceae; alternative wood; new materials; riverine communities; sustainable development

RESUMO

As palmeiras têm sido consideradas uma importante fonte de matéria-prima lenhosa em substituição à madeira, contudo, os usos dos caules de espécies nativas do Brasil são conhecidos apenas em nível local ou regional. Realizamos uma revisão da literatura sobre o conhecimento tradicional dos usos dos caules de espécies de palmeiras nativas do bioma Amazônia no Brasil, e relacionamos os tipos de uso com as características morfológicas dos caules. A revisão resultou em informações sobre 45 espécies com caules solitários ou cespitosos, e seis tipos de tamanhos de caules: alto (15 espécies), médio a curto (3), médio (5), pequeno (17), acaulescente (1) e escandente (4). Encontramos 80 indicações de uso dos caules em sete categorias e 14 subcategorias. Uma análise de similaridade mostrou que, em geral, caules com portes altos, médios a curtos, médios, pequenos (≥ 10 cm de diâmetro) e escandentes, solitários ou cespitosos, são usados para construções, móveis, artesanatos, utensílios, ferramentas e instrumentos musicais. Apenas caules de pequeno porte (< 10 cm de diâmetro) são usados para fazer armas para caça e pesca, e os caules escandentes para confecção de cordas. Caules de Socratea exorrhiza, Euterpe oleracea e Desmoncus polyacanthos são os mais utilizados para atender às necessidades de subsistência em comunidades tradicionais da Amazônia brasileira. Nossos resultados indicam o uso potencial dos caules de diversas espécies nativas de palmeiras como fontes de materiais alternativos na indústria manufatureira e como fontes de renda sustentável para as comunidades amazônicas.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE:

Arecaceae; madeira alternativa; novos materiais; comunidades ribeirinhas; desenvolvimento sustentável

INTRODUCTION

There are about 378 species of 71 genera of palms (Arecaceae/Palmae) in Brazil, distributed in all Brazilian biomes. The greatest diversity is known from the Amazon region, where 148 native species have been listed (Soares et al. 2020Soares, K.P.; Lorenzi, H.; Vianna, S.A.; Leitman, P.M.; Heiden, G.; Moraes R.M.; Martins, R.C.; Campos-Rocha, A.; Ellert-Pereira, P.E.; Eslabão, M.P. 2020. Arecaceae in Flora do Brasil 2020. Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro. ( (http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/reflora/floradobrasil/FB53 ). Acessed on 11 Nov 2020.

http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/reflora...

). Several Amazonian species are endemic and under increasing pressure due to deforestation (Alvez-Valles et al. 2018Alvez-Valles, C.M.; Balslev, H.; Garcia-Villacorta, R.; Carvalho, F.A.; Menini Neto, L. 2018. Palm species richness, latitudinal gradients, sampling effort, and deforestation in the Amazon region. Acta Botanica Brasilica, 32: 527-539.).

Palms are the main source of natural resources for populations living in the Amazon region (Santos and Coelho-Ferreira 2012Santos, R.S.; Coelho-Ferreira, M. 2012. Estudo etnobotânico de Mauritia flexuosa L.f. (Arecaceae) em comunidades ribeirinhas do Município de Abaetetuba, Pará, Brasil. Acta Amazonica, 42: 1-10.), satisfying subsistence needs in various categories of use, such as food, construction, handicrafts, fibers, medicine, cosmetics, textiles and biodiesel, among others (Zambrana et al. 2007Zambrana, N.Y.P.; Byg, A.; Svenning, J.C.; Moraes, M.; Grandez, C.; Balslev, H. 2007. Diversity of palm uses in the western Amazon. Biodiversity Conservation, 16: 2771-2787.; Macía et al. 2011Macía, M.J.; Armesilla, P.J; Cámara-Leret, R.; Paniagua-Zambrana, N.; Villalba, S. Balslev, H.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. 2011. Palm uses in northwestern south America: A quantitative review. Botanical Review, 77: 462-570.; Bernal et al. 2011Bernal, R.; Torres, C.; García, N.; Isaza, C.; Navarro, J.; Vallejo, M.I.; Galeano, G.; Balslev, H. 2011. Palm Management in South America. The Botanical Review, 77: 607-646.; Pennas et al. 2019Pennas, L.G.A.; Cattani, I.M; Leonardi, B.; Seyam, A-F.M.; Midani, M.; Monteiro, A.S.; Baruque-Ramos, J. 2019. Textile palm fibers from Amazon biome. Materials Research Proceedings, 11: 262-274. ). Most species are only known regionally or locally and therefore their traditional use and contribution to human well-being and the regional economy are unknown to the general public (Clement et al. 2005Clement, C.R.; Lleras, E.; van Leeuwen, J. 2005. O potencial das palmeiras tropicais no Brasil: acertos e fracassos das últimas décadas. Agrociência, 9: 67-71.). This traditional knowledge is of fundamental importance for the conservation and sustainable exploitation of useful palms, supporting programs for the management of natural resources and implementation of economic development in local communities (Zambrana et al. 2007Zambrana, N.Y.P.; Byg, A.; Svenning, J.C.; Moraes, M.; Grandez, C.; Balslev, H. 2007. Diversity of palm uses in the western Amazon. Biodiversity Conservation, 16: 2771-2787.). Furthermore, woody monocots, prominently including palms, are increasingly being considered as a source of renewable raw material to replace eudicotyledonous and coniferous wood (Trindade and Máximo 2017Trindade, A.A.; Máximo, F.H.D. 2017. Desdobro de estipe de pupunha (Bactris gasipaes Kunth) para novos produtos. Mix Sustentável, 3: 123-132.; El-Mously et al. 2019El-Mously, H. 2019. Rediscovering Date Palm by-products: an opportunity for sustainable development. Materials Research Proceedings, 11: 3-61. doi.org/10.21741/9781644900178-1

https://doi.org/doi.org/10.21741/9781644...

), and as options for crop diversification to create investment opportunities with the generation of new products (Corandin et al. 2018Coradin, L.; Camillo, J.; Pareyn, F.G.C. 2018. Espécies Nativas da Flora Brasileira de Valor Econômico Atual ou Potencial: Plantas Para o Futuro: Região Nordeste. MMA, Distrito Federal, 1311p.).

Despite not forming actual heartwood, stems are among the most commonly used parts of palms, reportedly for construction, handicrafts and daily utensils, among other purposes (Vilhena-Potiguara et al. 1987Vilhena-Potiguara, R.C.; Almeida, S.S.; Oliveira, J.; Lobato, L.C.B.; Lins, A.L.F.A. 1987. Plantas Fibrosas - I. Levantamento botânico na microrregião do Salgado (Pará, Brasil). Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, 3: 279-301.; Miranda et al. 2001Miranda, I.P.A.; Rabelo, A.; Bueno, C.R.; Barbosa, E.M.; Ribeiro, M.N.S. 2001. Frutos de Palmeiras da Amazônia. Editora INPA, Manaus, 120p.; Rocha and Silva 2005Rocha, A.E.S.; Silva, M.F.F. 2005. Aspectos fitossociológicos, florísticos, etnobotânicos das palmeiras (Arecaceae) de floresta secundária no município de Bragança, PA, Brasil. Acta Botanica Brasilica, 19: 657-667.; Oliveira et al. 2006Oliveira, J.; Potiguara, R.C.V.; Lobato, L.C.B. 2006. Fibras vegetais utilizadas na pesca artesanal na microrregião do Salgado, Pará. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Ciências Naturais, 1: 113-127.; Araújo et al. 2016Araújo, F.R.; González-Pérez, S.E; Lopes, M.A.; Viégas, I.J.M. 2016. Ethnobotany of babassu palm (Attalea speciosa Mart.) in the Tucuruí lake protected areas mosaic - eastern Amazon. Acta Botanica Brasilica, 30: 193-204.). In this context, the objective of this review was to survey the recorded uses of stems of palm species native to the Brazilian Amazon and to relate uses to stem morphological types.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Survey of palm species with recorded stem use

Palm species native to the Amazon biome in Brazil with some recorded use of its stem were surveyed in print and digital media. All phytophysiognomies occuring in the Brazilian Amazon were considered: terra firme forest, floodplain forest, swamp forest, ombrophylous forest, riparian or gallery forest, savanna forest, campina (white-sand grass/shrublands), campinarana (white-sand forest), restinga (sandy coastal plain vegetation) and ironstone outcrops.

The survey of printed media involved scientific papers, dissertations, theses and books cataloged in the libraries of nine Brazilian institutions: Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi (MPEG), Embrapa Amazônia Oriental (CPATU), Universidade Federal Rural da Amazônia (UFRA), Universidade Federal do Pará (UFPA) and Universidade do Estado do Pará (UEPA) in the northern state of Pará; Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia (INPA) in the state of Amazonas; and Instituto de Pesquisas Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro (JBRRJ), Museu Nacional da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (MN/UFRJ) and Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (UERJ) in Rio de Janeiro state.

The digital survey was carried out using the following databases: Catálogo de Teses e Dissertações da Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (www.catalogodeteses.capes.gov.br); Google Scholar (www.scholar.google.com.br); JSTOR (www.jstor.org); Scielo (www.scielo.br); Scopus (www.scopus.com); Web of Science (www.webofknowledge.com) and Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária (www.embrapa.br/seb). The following search terms were used: ethnobotany of palms, fibrous plants, stems of palms, palms products, uses of palms. Only citations from the Amazon biome in the Brazilian federal states of Acre, Amapá, Amazonas, Pará, Rondônia, Roraima and Tocantins, as well as parts of the states of Maranhão and Mato Grosso, were considered.

The following information was extracted for each species of surveyed palm: species, local name, habit, stem type, use category, use subcategory, forms of use, distribution in the Brazilian Amazon, references and distribution in Brazil (Table 1). The uses of the stems surveyed in literature were classified in categories and subcategories according to Macía et al. (2011Macía, M.J.; Armesilla, P.J; Cámara-Leret, R.; Paniagua-Zambrana, N.; Villalba, S. Balslev, H.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. 2011. Palm uses in northwestern south America: A quantitative review. Botanical Review, 77: 462-570.). The latter authors carried out a review on the use of palms in northern South America, and classified the ethnobotanical uses of specific plant parts into ten categories, each divided into subcategories. When the ethnobotanical information was not classifiable within any subcategory, it was assigned the subcategory ‘other’. The compiled list of scientific names of species recovered from our survey was checked and updated, when necessary, using the lists of Flora do Brasil (2020Flora do Brasil 2020. Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro. ( (http://www.floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br ). Acessed on 10 Sep 2020.

http://www.floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br...

) and SpeciesLink (2021SpeciesLink. 2021. Centro de Referência em informação Ambiental-CRIA. ( (http://www.splink.org.br/index?lang=pt ). Acessed on 07 Apr 2021.

http://www.splink.org.br/index?lang=pt...

). Recorded stem-use categories were mapped by state included in the Amazon biome based on the study areas in the literature sources, when provided.

Stem type and use of palm species native to the Brazilian Amazon. Local name according to the citation source. Stem type: TS = tall stem; MS = medium stem; MSS = medium-short stem; SS = small stem; AS = acaulescent; CS = climbing stem. Habit: S = solitary; C = cespitose. Use categories (according to Macía et al. 2011Macía, M.J.; Armesilla, P.J; Cámara-Leret, R.; Paniagua-Zambrana, N.; Villalba, S. Balslev, H.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. 2011. Palm uses in northwestern south America: A quantitative review. Botanical Review, 77: 462-570.): Constr = construction; Cultur = cultural, Environ = Environmental, Fuel, HuFood = Human food, UtenTool = Utensils and tools, Other = Other uses. Forms of use cited as in the original source. State: Brazilian Amazon state in which the use was reported. State acronyms: AC = Acre, AL = Alagoas, AM = Amazonas, AP = Amapá, BA = Bahia, CE = Ceará, DF = Distrito Federal, ES = Espírito Santo, GO = Goiás, MG = Minas Gerais, MS = Mato grosso do Sul, MT = Mato Grosso, PA = Pará, PE = Pernambuco, PI = Piauí, RJ = Rio de Janeiro, RO = Rondônia, RR = Roraima, RN = Rio Grande do Norte, SP = São Paulo, TO = Tocantins). Ns = Not specified. Acronyms in bold font are unconfirmed occurrences.

Palm-stem types were defined according to Balslev et al. (2011Balslev, H.; Eiserhardt, W.L.; Kristiansen, T.; Pedersen, D.; Grandez, C. 2010. Palms and palm communities in the upper Ucayali river valley-a little-known region in the Amazon basin. Palms, 54: 57-72.), who classified tropical palm species of South America into eight forms of growth, based on maximum sizes of attributes such as leaf size, absence or presence of aerial stem and aerial stem length and diameter. Within each form of growth, the species are further classified as cespitose or solitary (Table 2).

Statistical analysis

In order to evaluate the association between stem characteristics and uses, data of the stem-type, use categories and use subcategories (Table 1) were organized in a binary matrix of presence (1) and absence (0). The matrix was subjected to cluster analysis performed with the Vegan 2.5-7 package, in the R software (R Core Team 2021R Core Team. 2021. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. ( (http://www.rproject.org ). Acessed on 23 Jul 2021.

http://www.rproject.org...

). Species with greater similarity in relation to the analyzed characteristics were grouped using the unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) (Sneath and Sokal 1973Sneath, P.H.; Sokal, R.R. 1973. Numerical Taxonomy: The Principles and Practice of Numerical Classification. W.H. Freeman, San Francisco. 573p.) with the Jaccard coefficient.

SPECIES WITH RECORDED STEM USE

We recovered 43 literature references with records of the use of stems of 45 species of native palms in the Brazilian Amazon (Table 1). The work of Miranda et al. (2001Miranda, I.P.A.; Rabelo, A.; Bueno, C.R.; Barbosa, E.M.; Ribeiro, M.N.S. 2001. Frutos de Palmeiras da Amazônia. Editora INPA, Manaus, 120p.) had the highest number of cited palm species (24), followed by Lorenzi et al. (2010Lorenzi, H.; Noblick, L.R.; Kahn, F.; Ferreira, E. 2010. Flora Brasileira: Arecaceae (Palmeiras). Instituto Plantarum, Nova Odessa, 384p.) (16), Miranda and Rabelo (2008)Miranda, I.P.A.; Rabelo, A. 2008. Guia de Identificação das Palmeiras de Porto Trombetas/Pará. Editora INPA, Manaus , 112p. (16) and Shanley and Medina (2005Shanley, P.; Medina, G.S. 2005. Frutiferas e Plantas Úteis na Vida Amazônica. CIFOR/Imazon, Belém, 300p.) (7). More than 50% of the studies mentioned only one or two palm species regarding stem use.

Knowledge on the uses of palm stems was retrived from riverine, quilombola (settlements originating from runaway slaves), rubber tapper, family farmer, artisan and extractivist communities, as well as indigenous communities of the Yanomami tribe in the state of Amazonas (Anderson 1977Anderson, A.B. 1977. Os nomes e usos de palmeiras de uma tribo de índios Yanomama. Acta Amazonica, 7: 5-13.), the Yawanawá and Kaninawá in the state of Acre (Campos and Ehringhaus 2003Campos, M.T.; Ehringhaus, C. 2003. Plant virtues are in the eyes of the beholders: a comparison of known palm uses among indigenous and folk communities of southwestern Amazon. Economic Botany, 57: 324-344.), the Ti Araçá in the state of Roraima (Ribeiro 2010Ribeiro, A.H. 2010. O buriti (Mauritia flexuosa L.f) na terra indígena Aracá, Roraima: usos tradicionais, manejo e potencial produtivo. Master’s dissertation, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, Brazil, 90p. (https://bdtd.inpa.gov.br/handle/tede/1103)) and the Karipuna in the state of Amapá (Fonte et al. 2015Fonte, A.P.N. 2015. Uasei, o Livro do Açaí: Saberes do Povo Karipuna. Iepé, São Paulo, 76p.). Most studies were carried out in riverine communities. At the state level, most citations were from Pará (25), followed by Amazonas (13), Acre (12), Roraima (6), Mato Grosso (5), Maranhão (3) and Rondônia and Amapá with one citation each (Table 1).

The 45 surveyed palm species belong to the subfamilies Arecoideae and Calamoideae (Table 1). Arecoideae had the greatest number of representatives, with 41 species distributed in two tribes, six subtribes and 15 genera, four of which with spiny stems (Table 1). Calamoideae was represented by only four species belonging to one tribe, two subtribes and three genera (Table 1).

Oenocarpus Mart. and Euterpe Mart. were the genera with the highest number of species with stem-use citations relative to the total number of species known for the genus in the Brazilian Amazon (five of six species, and three of four species, respectively), followed by Desmoncus Mart. (four of nine species), Astrocaryum G.Mey (six of 21), Bactris Jacq. ex Scop. (11 of 35), and Attalea Kunth (two of 14) and Syagrus Mart. (two of six species) (Table 2). Iriartea deltoidea was citeded in an area of the Brazilian Amazon where there is no confirmed occurrence record of this species (Table 1).

The 45 cited species represent about 28% of the 161 palm species recognized for the northern region of Brazil, and 30% of the 148 species recognized for the Brazilian Amazon (Soares et al. 2020Soares, K.P.; Lorenzi, H.; Vianna, S.A.; Leitman, P.M.; Heiden, G.; Moraes R.M.; Martins, R.C.; Campos-Rocha, A.; Ellert-Pereira, P.E.; Eslabão, M.P. 2020. Arecaceae in Flora do Brasil 2020. Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro. ( (http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/reflora/floradobrasil/FB53 ). Acessed on 11 Nov 2020.

http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/reflora...

). In northwestern South America, information on the use of palm stems was retrieved for 59% of the 134 species occurring in the Amazon region (Macía et al. 2011Macía, M.J.; Armesilla, P.J; Cámara-Leret, R.; Paniagua-Zambrana, N.; Villalba, S. Balslev, H.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. 2011. Palm uses in northwestern south America: A quantitative review. Botanical Review, 77: 462-570.). The record of use of Iriartea deltoidea is evidence of its presence in the state of Pará (Alves et al. 2014Alves, G.; Albernaz, A.L.K.M.; Lopes, M.A. 2014. Palmeiras do Distrito Florestal Sustentável da BR-163. Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Belém, 50p.), which expands its area of occurrence in Brazil. This finding is relevant, as palms remain a poorly sampled group with little representation in Amazonian herbaria (Rocha and Silva 2005Rocha, A.E.S.; Silva, M.F.F. 2005. Aspectos fitossociológicos, florísticos, etnobotânicos das palmeiras (Arecaceae) de floresta secundária no município de Bragança, PA, Brasil. Acta Botanica Brasilica, 19: 657-667.; Henderson 2011Henderson, A. 2011. A revision of Desmoncus (Arecaceae). Phytotaxa, 35: 1-88.). Palms are frequently difficult to collect due to the presence of spines, the large size of vegetative and reproductive structures, the high and unbranched stems and to that individuals are frequetly sterile (Anderson 1977Anderson, A.B. 1977. Os nomes e usos de palmeiras de uma tribo de índios Yanomama. Acta Amazonica, 7: 5-13.; Miranda et al. 2001Miranda, I.P.A.; Rabelo, A.; Bueno, C.R.; Barbosa, E.M.; Ribeiro, M.N.S. 2001. Frutos de Palmeiras da Amazônia. Editora INPA, Manaus, 120p.; Ammann 2014Ammann, S. 2014. Etnobotânica de árvores e palmeiras em três comunidades ribeirinhas do rio Jauaperi, na divisa entre Roraima e Amazonas. Master’s dissertation, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, Brazil, 83p. (https://bdtd.inpa.gov.br/handle/tede/1646).

https://bdtd.inpa.gov.br/handle/tede/164...

; Rocha 2017Rocha, A.E.S. 2017. Guia de Coleta e Identificação de Palmeiras Nativas do Estado do Pará. Editora do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Belém. 4p.), resulting in that most records are field observations (Henderson et al. 1995; Miranda and Rabelo 2008Miranda, I.P.A.; Rabelo, A. 2008. Guia de Identificação das Palmeiras de Porto Trombetas/Pará. Editora INPA, Manaus , 112p.).

Traditional knowledge on the uses of Brazilian Amazonian palm parts, especially their woody or fibrous stems, has been investigated in local communities in the states of Pará and Amazonas (Anderson 1977Anderson, A.B. 1977. Os nomes e usos de palmeiras de uma tribo de índios Yanomama. Acta Amazonica, 7: 5-13.; Vilhena-Potiguara 1987Vilhena-Potiguara, R.C.; Almeida, S.S.; Oliveira, J.; Lobato, L.C.B.; Lins, A.L.F.A. 1987. Plantas Fibrosas - I. Levantamento botânico na microrregião do Salgado (Pará, Brasil). Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, 3: 279-301.; Miranda et al. 2001Miranda, I.P.A.; Rabelo, A.; Bueno, C.R.; Barbosa, E.M.; Ribeiro, M.N.S. 2001. Frutos de Palmeiras da Amazônia. Editora INPA, Manaus, 120p.; Rocha and Silva 2005Rocha, A.E.S.; Silva, M.F.F. 2005. Aspectos fitossociológicos, florísticos, etnobotânicos das palmeiras (Arecaceae) de floresta secundária no município de Bragança, PA, Brasil. Acta Botanica Brasilica, 19: 657-667.; Oliveira et al. 2006Oliveira, J.; Potiguara, R.C.V.; Lobato, L.C.B. 2006. Fibras vegetais utilizadas na pesca artesanal na microrregião do Salgado, Pará. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Ciências Naturais, 1: 113-127.; Santos and Coelho-Ferreira 2012Santos, R.S.; Coelho-Ferreira, M. 2012. Estudo etnobotânico de Mauritia flexuosa L.f. (Arecaceae) em comunidades ribeirinhas do Município de Abaetetuba, Pará, Brasil. Acta Amazonica, 42: 1-10.; Germano et al. 2014Germano, C.M.; Lucas, F.C.A.; Martins, A.C.C.T.; Moura, P.H.B.; Lobato, G.J.M. 2014. Comunidades ribeirinhas e palmeiras no município de Abaetetuba, Pará, Brasil. Scientia Plena, 10: 111701.; Santos et al. 2016Santos, R.S.; Coelho-Ferreira, M.; Lima, P.G.C. 2016. Espécies fibrosas em mercados do Distrito Florestal Sustentável da BR-163. Biota Amazônia, 6: 101-109.). Publications for other parts of the biome are still rare (e.g., Flores and Lima 2013Flores, A.S.; Lima, D.L. 2013. Fibras vegetais utilizadas no artesanato comercializado em Boa Vista, Roraima. Boletim do Museu Integrado de Roraima, 7: 35-39.). Although indigenous peoples have broad and diverse ethnobotanical knowledge about the use of palms in the Amazon (Bernal et al. 2011Bernal, R.; Torres, C.; García, N.; Isaza, C.; Navarro, J.; Vallejo, M.I.; Galeano, G.; Balslev, H. 2011. Palm Management in South America. The Botanical Review, 77: 607-646.; Macía et al. 2011Macía, M.J.; Armesilla, P.J; Cámara-Leret, R.; Paniagua-Zambrana, N.; Villalba, S. Balslev, H.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. 2011. Palm uses in northwestern south America: A quantitative review. Botanical Review, 77: 462-570.; Wallace 2014Wallace, A.R. 2014. Palmeiras da Amazônia e Seus Usos. EDUA, Manaus, 165p.; Smith 2015Smith, N. 2015. Palms and People in the Amazon. Geobotany Studies (Basics, Methods and Case Studies). Springer, Switzerland. 513p.), few publications mentioned palm-stem uses by indigenous communities in the Brazilian Amazon (Anderson 1977Anderson, A.B. 1977. Os nomes e usos de palmeiras de uma tribo de índios Yanomama. Acta Amazonica, 7: 5-13.; Campos and Ehringhaus 2003Campos, M.T.; Ehringhaus, C. 2003. Plant virtues are in the eyes of the beholders: a comparison of known palm uses among indigenous and folk communities of southwestern Amazon. Economic Botany, 57: 324-344.; Ribeiro 2010Ribeiro, A.H. 2010. O buriti (Mauritia flexuosa L.f) na terra indígena Aracá, Roraima: usos tradicionais, manejo e potencial produtivo. Master’s dissertation, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, Brazil, 90p. (https://bdtd.inpa.gov.br/handle/tede/1103); Fonte et al. 2015Fonte, A.P.N. 2015. Uasei, o Livro do Açaí: Saberes do Povo Karipuna. Iepé, São Paulo, 76p.). Most studies have focused on the subsistence, economic and sociocultural importance of palm species in riverine communities, which are more easily accessible (e.g., Jardim and Cunha 1998Jardim, M.A.G.; Cunha, A.C.C. 1998. Usos de palmeiras em uma comunidade ribeirinha da do estuário Amazônico. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Ciências Naturais, 14: 69-77.; Rodrigues et al. 2006Rodrigues, L.M.B.; Lira, A.U.S.; Santos, F.A.; Jardim, M.A.G. 2006. Composição florística e usos das espécies vegetais de dois ambientes de floresta de várzea. Revista Brasileira de Farmácia, 87: 45-48.; Santos and Coelho Ferreira 2011; Almeida and Jardim 2012Almeida, A.F.; Jardim, M.A.G. 2012. A utilização das espécies arbóreas da floresta de várzea da Ilha de Sororoca, Ananindeua, Pará, Brasil por moradores locais. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Ambientais, 23: 48-54.; Lima et al. 2013Lima, L.P.; Guerra, G.A.D.; Ming, L.C.; Macedo, M.R.A. 2013. Ocorrência e usos do tucumã (Astrocaryum vulgare Mart.) em comunidades ribeirinhas, quilombolas e de agricultores tradicionais no município de Irituia, Pará. Amazônica, Revista de Antropologia, 5: 762-778.; Germano et al. 2014Germano, C.M.; Lucas, F.C.A.; Martins, A.C.C.T.; Moura, P.H.B.; Lobato, G.J.M. 2014. Comunidades ribeirinhas e palmeiras no município de Abaetetuba, Pará, Brasil. Scientia Plena, 10: 111701.; Araujo et al. 2016).

The surveyed literature generally did not present detailed information about the study areas or the charcteristics of the palms, such as development stage or height and diameter of the used stems. In this sense, the use of the classification by Balslev et al. (2011Balslev, H.; Kahn, F.; Millan, B.; Svenning, J.C.; Kristiansen, T.; Borchsenius, F.; Pedersen, D.; Eiserhardt, W.L. 2011. Species diversity and growth forms in tropical American palm communities. Botanical Review, 77: 381-425.), though preliminary, was useful, as it is based on very basic characteristics, allowing categorization in the absence of detailed information. More standardized and informative surveys will be necessary to account for the wider amplitude in forms of growth and stem architectures, and the plasticity resulting from the development in different types of soil, hydrology, temperature, topography, incidence of sunlight and disturbance levels (Kahn and de Graville 1992Kanh, F.; de Granville, J.J. 1992. Palms in Florest Ecosystems of Amazonia. Ecological Studies, Springer Verlag, New York. 226p.; Balslev et al. 2011Balslev, H.; Kahn, F.; Millan, B.; Svenning, J.C.; Kristiansen, T.; Borchsenius, F.; Pedersen, D.; Eiserhardt, W.L. 2011. Species diversity and growth forms in tropical American palm communities. Botanical Review, 77: 381-425.; Salm et al. 2011Salm, R.; Albernaz, A.L.K.M.; Jardim, M. 2011. Abundance and diversity of palms in the sustainable forest district of BR 163, Pará Brazil. Biota Neotropica, 11: 99-105.; Muscarella et al. 2020Muscarella, R.; Emilio, T.; Phillips, L.O.; Lewis, S.L.; Slik, F.; Baker, W.L.; et al. 2020. The global abundance of tree palms. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 29: 1495-1514.).

STEM TYPES AND USES

The cited palm species have solitary or cespitose habit, with six types of stem-growth form (Figure 1; Table 1). The species with the greatest number of uses have cespitose stems (29 species, 64%) and are especially small palms (Bactris) or climber palms (Desmoncus) (Figure 2a; Table 1). Among species that do not branch, i.e., with solitary stems (16 species, 36%), the tall stem type was the most representative (Figure 2a; Table 1).

Types of stem of native palm species in the Brazilian Amazon. Stem-growth types according to Balslev et al. (2011Balslev, H.; Kahn, F.; Millan, B.; Svenning, J.C.; Kristiansen, T.; Borchsenius, F.; Pedersen, D.; Eiserhardt, W.L. 2011. Species diversity and growth forms in tropical American palm communities. Botanical Review, 77: 381-425.). The images show: tall stem (A-E), medium-short stem (F), medium stem (G), small stem (H), small stem ≥ 10 cm in diameter (I), acaulescent (J), climbing stem (K-L); solitary (A-D, I-J); cespitose (E-G, K-L), with spines (F-H, K-L). Species: Mauritia flexuosa (A); Oenocarpus distichus (B); Socratea exorrhiza (C-D); Euterpe oleracea (E); Astrocaryum vulgare (F); Bactris gasipaes (G); Bactris hirta (H); Syagrus cocoides (I); Attalea spectabilis (J); Desmoncus orthacanthos (K); D. polyacanthos (L). Habitats: floodplain forest (A, E, C-D); terra firme forest (B, F, H, J, G, K-L) in the Pará state (Brazil); rocky area (ferricrete) in Conceição do Araguaia, Pará state (Brazil) (I). Credits: André Cardoso (A, E, H-J); the authors (B-D, K-L); Jorge Oliveira (F) and Julcéia Camillo (G). This figure is in color in the electronic version.

Distribution frequency of stem types of the 45 species of native palm trees in the Brazilian Amazon recorded in this study, according to stem-growth form (A); and to the recorded categories of use (B). Stem-growth form (according to Balslev et al. 2011Balslev, H.; Kahn, F.; Millan, B.; Svenning, J.C.; Kristiansen, T.; Borchsenius, F.; Pedersen, D.; Eiserhardt, W.L. 2011. Species diversity and growth forms in tropical American palm communities. Botanical Review, 77: 381-425.): TS = tall stem, MSS = medium-short stem, MS = medium stem, SS = small stem, AS = acaulescent, CS = climbing stem. This figure is in color in the electronic version.

The stems were used mainly for utensils and tools (41 citations), construction (22), cultural (8), environmental uses (5), human food (2), fuel (1) and other uses (1), for a total of 80 indications of use. Utensils and tools are manufactured with all six stem types of all size categories (Figure 2b; Table 1). Tall-stem types were the most used in all categories of use, except for utensils and tools (Figure 2b). Only the stems of tall, medium and small palms were reportedly used for making musical instruments, such as flutes, drums, reco-recos (scraper percussion instrument), spears with rattle, trumpets and violas. The most cited species include Socratea exorrhiza (Figures 1c-d; 3a) (18 citations), with a tall stem, Euterpe oleracea (Figures 1e; 3b-f) (13 citations), with a tall stem and Desmoncus polyacanthos (nine citations), with a climbing stem (Table 1). The only record of commercial use of stem products was for the climbing palms Desmoncus orthacanthos (Figures 1k; 3g-h) and D. polyacanthos (Figures 1l; 3i-l), in the form of handicrafts marketed in municipal markets, fairs, warehouses and specialised shops in the states of Pará and Roraima (Flores and Lima 2013Flores, A.S.; Lima, D.L. 2013. Fibras vegetais utilizadas no artesanato comercializado em Boa Vista, Roraima. Boletim do Museu Integrado de Roraima, 7: 35-39.; Santos et al. 2016Santos, R.S.; Coelho-Ferreira, M.; Lima, P.G.C. 2016. Espécies fibrosas em mercados do Distrito Florestal Sustentável da BR-163. Biota Amazônia, 6: 101-109.).

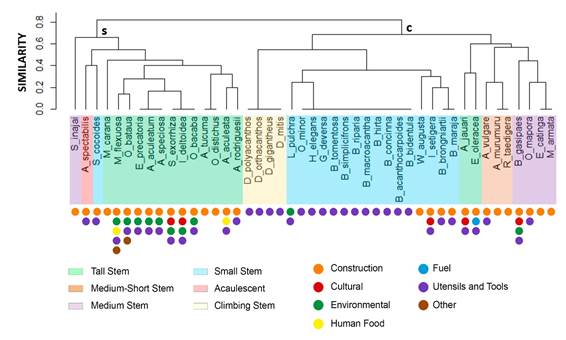

The cluster analysis formed four distinct groups (Figure 4). The first group contained only one solitary tall species that is used for construction. The second group comprised tall, medium and acaulescent palms with solitary stems also used for construction, environmental uses, utensils and tools, except for one species that is only recorded as used for utensils and tools (Mauritia carana). The third group was formed by cespitose, small palms (10 species of Bactris) and climbing palms (four species of Desmoncus), which were used, respectively, for handicrafts (arrowheads) and handicrafts, utensils and fishing traps, except for four species that were also used in construction: Bactris brongniatii (roofs and walls), Bactris maraja (fishing corrals), Iriartella setigera (floors and walls) and Wettinia augusta (floors and walls). The fourth group was composed of tall, medium-short and medium cespitose palms used for construction, utensils and tools, except for four species that were exclusively cited for construction (Astrocaryum murumuru, Euterpe catinga, Raphia taedigera and Mauritia armata). One species was used for firewood (Euterpe oleracea) and another as organic fertilizer (Bactris gasipaes). In the first group, two species of tall-stem palms were used for starch (Astrocaryum aculeata and Mauritia flexuosa) and two for larvae food (turus) (Mauritia flexuosa and Oenocarpus bacaba). Five species distributed in the three largest groups were used for manufacturing musical instruments (Astrocaryum jauari, Bactris gasipaes, Iriartea deltoidea, Iriatella setigera and Socratea exorrhiza) (Figure 4; Table 1).

Uses of stems of native palm species in the Brazilian Amazon. Fishing traps: cacuri (A) in the Tocantins River, Pará state (Brazil); matapi (G). Construction: house (B); walls (C-D); floor (E); roof (arrow) (F) on Cotijuba Island, Pará state. Domestic utensils: bag (H); basket (I); fan (J); sieve (K) on Marajó Island, Pará state; cylindrical tube press (tipiti) (L) in Santo Antonio de Itapucú, Manaus state (Brazil); bowl (M) in Belém, Pará state. Furniture: tables (N-O). Organic fertilizer for orchids (P) in Terra Santa, Pará state. Stem-growth form (according to Balslev et al. 2011Balslev, H.; Kahn, F.; Millan, B.; Svenning, J.C.; Kristiansen, T.; Borchsenius, F.; Pedersen, D.; Eiserhardt, W.L. 2011. Species diversity and growth forms in tropical American palm communities. Botanical Review, 77: 381-425.): TS = tall stem cespitose (A) or solitary (B-F, M, P); MS = medium stem (N-O); CS = climbing stem (G-L). Species: Socratea exorrhiza (A); Euterpe oleracea (B-F); Desmoncus orthacanthos (G, H); D. polyacanthos (I-L); Oenocarpus bataua (M); Bactris gasipaes (N-O); Astrocaryum aculeatum (P). Credits: Nigel Smith (www.animalsanimals.com) (A) and Springer International Publishing (L); the authors (B-H, M); Sueyla Bezerra (I-K); Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia (N); Henrique Borçato (O); João Batista (P). This figure is in color in the electronic version.

Dendrogram resulting from a cluster analysis of stem characteristics and uses of 45 palm species native to the Brazilian Amazon with recorded traditional uses of the stem. C = cespitose; S = solitary. This figure is in color in the electronic version.

Despite being broad-scaled, our analysis indicated that species with both solitary or cespitose stems are employed in all use categories, although specific stem types are associated with specific forms of use. In particular, small cespitose stems of Geonoma deversa, Hyospathe elegans, Iriartea setigera, Oenocarpus minor and ten species of Bactris were used by indigenous peoples to make hunting tools such as blowgun, bows, arrows, harpoons and spears for being hard but flexible (Miranda et al. 2001Miranda, I.P.A.; Rabelo, A.; Bueno, C.R.; Barbosa, E.M.; Ribeiro, M.N.S. 2001. Frutos de Palmeiras da Amazônia. Editora INPA, Manaus, 120p.; Campos and Ehringhaus 2003Campos, M.T.; Ehringhaus, C. 2003. Plant virtues are in the eyes of the beholders: a comparison of known palm uses among indigenous and folk communities of southwestern Amazon. Economic Botany, 57: 324-344.; Miranda and Rabelo 2008Miranda, I.P.A.; Rabelo, A. 2008. Guia de Identificação das Palmeiras de Porto Trombetas/Pará. Editora INPA, Manaus , 112p.; Lorenzi et al. 2010Lorenzi, H.; Noblick, L.R.; Kahn, F.; Ferreira, E. 2010. Flora Brasileira: Arecaceae (Palmeiras). Instituto Plantarum, Nova Odessa, 384p.). Cespitose climbing stems of Desmoncus are used to make baskets, ropes and various utensils, such as tipitis, an indigenous technology found only in the Brazilian Amazon, developed to remove the toxic liquid from bitter cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) (Carney and Hiraoka 1997Carney, J.; Hiraoka, M. 1997. Raphia taedigera in the Amazon Estuary. Principes, 41: 125-130.; Smith 2015Smith, N. 2015. Palms and People in the Amazon. Geobotany Studies (Basics, Methods and Case Studies). Springer, Switzerland. 513p.). Desmoncus polyacanthos fibers are considered more flexible and resistant than those of other species used to make tipitis, such as the petiole of Ischnosiphon obliquus (Rudge) Körn (Marantaceae) and the leaves of Mauritia flexuosa and Oenocarpus bacaba (Miranda et al. 2001Miranda, I.P.A.; Rabelo, A.; Bueno, C.R.; Barbosa, E.M.; Ribeiro, M.N.S. 2001. Frutos de Palmeiras da Amazônia. Editora INPA, Manaus, 120p.; Wallace 2014Wallace, A.R. 2014. Palmeiras da Amazônia e Seus Usos. EDUA, Manaus, 165p.; Smith 2015Smith, N. 2015. Palms and People in the Amazon. Geobotany Studies (Basics, Methods and Case Studies). Springer, Switzerland. 513p.). The fibrous climbing stems of Desmoncus are used in a similar way as Asian rattan (Uhl and Dransfild 1987Dransfield, J. 1978. Growth form of rain forest palms. In: Tomlinson, P.B.; Zimmermann, M.H. (Ed.). Tropical Trees as Living Systems, Cambridge University Press, New York. p.247-268.), and are the only type of stems commercialized in northern Brazil, as household utensils and decoration (Flores et al. 2013Flores, A.S.; Lima, D.L. 2013. Fibras vegetais utilizadas no artesanato comercializado em Boa Vista, Roraima. Boletim do Museu Integrado de Roraima, 7: 35-39.; Santos et al. 2016Santos, R.S.; Coelho-Ferreira, M.; Lima, P.G.C. 2016. Espécies fibrosas em mercados do Distrito Florestal Sustentável da BR-163. Biota Amazônia, 6: 101-109.). Yet, its potential for industrial use remains little explored (Miranda et al. 2001Miranda, I.P.A.; Rabelo, A.; Bueno, C.R.; Barbosa, E.M.; Ribeiro, M.N.S. 2001. Frutos de Palmeiras da Amazônia. Editora INPA, Manaus, 120p.). In fact, the uses of many species of palm trees are not recorded in the literature (T. Kikuchi, pers. obs.), such as the tall stems of the Patauá palm (Oenocarpus sp.), which are used to manufacture utensils that can be found in craft stores and fairs (Figure 3m), highlighting the need for further studies that focus on ethnobotanical knowledge of useful palm species in the Amazon region (Macía et al. 2011Macía, M.J.; Armesilla, P.J; Cámara-Leret, R.; Paniagua-Zambrana, N.; Villalba, S. Balslev, H.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. 2011. Palm uses in northwestern south America: A quantitative review. Botanical Review, 77: 462-570.).

The stems of tall, medium-short and medium, solitary or cespitose palms are the most valuable for construction and production of utensils, accessories, tools and handicrafts, due to the resistance and workability of their wood (Anderson 1977Anderson, A.B. 1977. Os nomes e usos de palmeiras de uma tribo de índios Yanomama. Acta Amazonica, 7: 5-13.; Miranda et al. 2001Miranda, I.P.A.; Rabelo, A.; Bueno, C.R.; Barbosa, E.M.; Ribeiro, M.N.S. 2001. Frutos de Palmeiras da Amazônia. Editora INPA, Manaus, 120p.; Miranda and Rabelo 2001Miranda, I.P.A.; Rabelo, A. 2008. Guia de Identificação das Palmeiras de Porto Trombetas/Pará. Editora INPA, Manaus , 112p.). Stems of acaulescent, medium-short and small types are less valuable and used only as an alternative when there is a shortage of more suitable species (e.g., Attalea spectabilis) (Anderson 1977Anderson, A.B. 1977. Os nomes e usos de palmeiras de uma tribo de índios Yanomama. Acta Amazonica, 7: 5-13.), or when certain species are locally abundant (e.g., Astrocaryum vulgare, Bactris brongniatii, B. maraja, Iriartella setigera and Oenocarpus minor) (Souza et al. 2010; Jardim and Cunha 1998Jardim, M.A.G.; Cunha, A.C.C. 1998. Usos de palmeiras em uma comunidade ribeirinha da do estuário Amazônico. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Ciências Naturais, 14: 69-77.). Locally abundant, resistant species are also associated with a higher number of use citations (Germano et al. 2014Germano, C.M.; Lucas, F.C.A.; Martins, A.C.C.T.; Moura, P.H.B.; Lobato, G.J.M. 2014. Comunidades ribeirinhas e palmeiras no município de Abaetetuba, Pará, Brasil. Scientia Plena, 10: 111701.), both in floodplain and terra firme environments, such as Astrocaryum aculeata, A. aculeatum, A. jauari, A. rodriguesii, A. tucuma, A. vulgare; Attalea speciosa, Bactris gasipaes, Desmoncus polyacanthos, D. gigantheus, D. orthacanthos, D. mitis, Euterpe catinga, E. oleracea, E. precatoria, Iriartea deltoidea, Leopoldinia pulchra, Mauritia flexuosa, Mauritiella armata, Oenocarpus bacaba, O. bataua, O. mapora, Raphea taedigera, Syagrus cocoides, S. inajai, Socratea exorrhiza and Wettinia augusta (e.g., Anderson 1977; Jardim and Cunha 1998Jardim, M.A.G.; Cunha, A.C.C. 1998. Usos de palmeiras em uma comunidade ribeirinha da do estuário Amazônico. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Ciências Naturais, 14: 69-77.; Carney and Hiraoka 2003; Ferreira 2005; Lorenzi et al. 2010Lorenzi, H.; Noblick, L.R.; Kahn, F.; Ferreira, E. 2010. Flora Brasileira: Arecaceae (Palmeiras). Instituto Plantarum, Nova Odessa, 384p.; Miranda and RabeloMiranda, I.P.A.; Rabelo, A. 2008. Guia de Identificação das Palmeiras de Porto Trombetas/Pará. Editora INPA, Manaus , 112p.; Almeida and Jardim 2012Almeida, A.F.; Jardim, M.A.G. 2012. A utilização das espécies arbóreas da floresta de várzea da Ilha de Sororoca, Ananindeua, Pará, Brasil por moradores locais. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Ambientais, 23: 48-54.; Araújo et al. 2016Araújo, F.R.; González-Pérez, S.E; Lopes, M.A.; Viégas, I.J.M. 2016. Ethnobotany of babassu palm (Attalea speciosa Mart.) in the Tucuruí lake protected areas mosaic - eastern Amazon. Acta Botanica Brasilica, 30: 193-204.; Wallace and Ferreira 2016Wallace, R.H.; Ferreira, E.J.L. 2016. Usos, extração e potencial de produção de frutos de três espécies de palmeiras nativas na Reserva Extrativista Chico Mendes, Acre: implicações para a extração comercial. In: Siviero, A.; Ming, L.C.; Silveira, M.; Daly, D.C.; Wallace, R.H. (Org.). Etnobotânica e Botânica Econômica do Acre [ebook]. Edufac, Rio Branco , p.288-298.). The lack of records on some species, such as Mauritia carana, is attributed to the difficulty in harvesting these palms, which have been replaced as raw material over the years in construction and manufacture of utensils by industrialized materials (Rocha and Silva 2005Rocha, A.E.S.; Silva, M.F.F. 2005. Aspectos fitossociológicos, florísticos, etnobotânicos das palmeiras (Arecaceae) de floresta secundária no município de Bragança, PA, Brasil. Acta Botanica Brasilica, 19: 657-667.; Germano et al. 2014Germano, C.M.; Lucas, F.C.A.; Martins, A.C.C.T.; Moura, P.H.B.; Lobato, G.J.M. 2014. Comunidades ribeirinhas e palmeiras no município de Abaetetuba, Pará, Brasil. Scientia Plena, 10: 111701.; Smith 2015Smith, N. 2015. Palms and People in the Amazon. Geobotany Studies (Basics, Methods and Case Studies). Springer, Switzerland. 513p.).

Only the stems of Astrocaryum jauari, Bactris gasipaes, Iriatella setigera, Iriartea deltoidea and Socratea exorrhiza were mentioned for the manufacture of musical instruments, especially by indigenous Kaxinawá in Acre state (Campos and Ehringhaus 2003Campos, M.T.; Ehringhaus, C. 2003. Plant virtues are in the eyes of the beholders: a comparison of known palm uses among indigenous and folk communities of southwestern Amazon. Economic Botany, 57: 324-344.). The wood of these species probably has the anatomical, physical and mechanical properties to provide ideal resonance features. These species were also reported in most other use categories, showing their importance to meet the basic subsistence needs of traditional communities in the Brazilian Amazon (Santos and Coelho-Ferreira 2012Santos, R.S.; Coelho-Ferreira, M. 2012. Estudo etnobotânico de Mauritia flexuosa L.f. (Arecaceae) em comunidades ribeirinhas do Município de Abaetetuba, Pará, Brasil. Acta Amazonica, 42: 1-10.; Gernano et al. 2014Germano, C.M.; Lucas, F.C.A.; Martins, A.C.C.T.; Moura, P.H.B.; Lobato, G.J.M. 2014. Comunidades ribeirinhas e palmeiras no município de Abaetetuba, Pará, Brasil. Scientia Plena, 10: 111701.). In the environmental use category, stems were used to make organic fertilizer (Figure 3p), fences and enclosures for vegetable gardens and gardens (Lorenzi et al. 2010Lorenzi, H.; Noblick, L.R.; Kahn, F.; Ferreira, E. 2010. Flora Brasileira: Arecaceae (Palmeiras). Instituto Plantarum, Nova Odessa, 384p.; Germano et al. 2014Germano, C.M.; Lucas, F.C.A.; Martins, A.C.C.T.; Moura, P.H.B.; Lobato, G.J.M. 2014. Comunidades ribeirinhas e palmeiras no município de Abaetetuba, Pará, Brasil. Scientia Plena, 10: 111701.). In the fuel category, wood from Euterpe oleracea is used for heat bricks (Miranda et al. 2001). In the human food category, sap, and starch similar to the sago used for porridge are obtained, respectively, from the stems of Acrocomia aculeata and Mauritia flexuosa (Miranda et al. 2001; Miranda and Rabelo 2008Miranda, I.P.A.; Rabelo, A. 2008. Guia de Identificação das Palmeiras de Porto Trombetas/Pará. Editora INPA, Manaus , 112p.). In the category of other uses, it was mentioned that the wood from rotten stems of Mauritia flexuosa and Oenocarpus bataua that were in contact with water from floodplains or rivers, are consumed by molluscs called turu, which, in turn, are used as a food source by many riverine communities (Miranda et al. 2001; Gomes-Silva 2005Gomes-Silva, D.A.P. 2005. Patauá. In: Shanley, P.; Medina, G. (Org.). Frutíferas e Plantas Úteis na Vida Amazônica. CIFOR, Imazon, Belém, p.197-202.). The use of palm stems as a source of larvae of Rhyncophorus palmarum (Coleoptera), which are used for human consumption, is the most cited in the other use category in the Amazon of Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia (Macía et al. 2011Macía, M.J.; Armesilla, P.J; Cámara-Leret, R.; Paniagua-Zambrana, N.; Villalba, S. Balslev, H.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. 2011. Palm uses in northwestern south America: A quantitative review. Botanical Review, 77: 462-570.). More forms of use for the stems of many palm species could probably have been registered in the utensils and tools category if they had been described in detail by the citing authors beyond generic terms such as “handicrafts” and “artifacts”.

In the western Amazon, the stems of Bactris gasipaes, Iriartea deltoidea, Oenocarpus bataua, O. mapora and Socratea exorrhiza were the most used by traditional peoples, especially indigenous peoples, in various categories of use, such as construction, cultural, environmental uses, fuel, human food, medicines and veterinary medicine, utensils and tools and other uses (Macía et al. 2011Macía, M.J.; Armesilla, P.J; Cámara-Leret, R.; Paniagua-Zambrana, N.; Villalba, S. Balslev, H.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. 2011. Palm uses in northwestern south America: A quantitative review. Botanical Review, 77: 462-570.). Among these species, Bernal et al. (2011Bernal, R.; Torres, C.; García, N.; Isaza, C.; Navarro, J.; Vallejo, M.I.; Galeano, G.; Balslev, H. 2011. Palm Management in South America. The Botanical Review, 77: 607-646.) described the stems of Euterpe oleracea, Iriartea deltoidea, Socratea exorrhiza and Desmoncus polyacanthos as the most important for construction and crafts in South America, but their uses are still restricted to local or regional domestic consumption. The stem uses of these same species were also the most cited for the Brazilian Amazon.

The traditional knowledge on the uses of palm species contributes to the conservation of palm-trees and to devise sustainable alternative sources of income for local communities (Thoma et al. 2016Thoma, A.C.; Aguiar, N.C.; Prat, B.V.; Cambraia, R.P. 2016. Palmeiras nativas indicadas para uso em construções. Revista Científica Vozes dos Vales, 10: 1-13.), and provides an invaluable information source for prospection of new materials and biotechnological applications. Among current studies on industrial applications of palm-stem products, coconut palm (Cocos nucifera L.) stems have been used in the production of biocomposites for parcial or total replacement of conventional building materials such as steel, concrete and bricks (González et al. 2019González, O.M.; Barrigas, H.L.; Andino, N.; García, A.; Guachambala, M. 2019. Innovative bio-composite sandwich wall panels made of coconut bidirectional external veneers and balsa lightweight core as alternative for eco-friendly and structural building applications in high-risk seismic regions. Materials Science and Engineering C, 11: 88-98. doi.org/10.21741/9781644900178-5

https://doi.org/doi.org/10.21741/9781644...

), in addition to stems of Astrocaryum aculeatum and Bactris gasipaes (Figure 3n-o), that have potential for the development of new products for the furniture industry (Miranda and Rabelo 2008Miranda, I.P.A.; Rabelo, A. 2008. Guia de Identificação das Palmeiras de Porto Trombetas/Pará. Editora INPA, Manaus , 112p.; Trindade and Máximo 2017Trindade, A.A.; Máximo, F.H.D. 2017. Desdobro de estipe de pupunha (Bactris gasipaes Kunth) para novos produtos. Mix Sustentável, 3: 123-132.). The formulation of public policies is necessary to systematize the knowledge on the use of Brazilian Amazonian palm species and to promote the rational use and appreciation for products generated from the woody or fibrous palm stems, in all cases ensuring the conservation and sustainability of the extraction.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - CAPES (Brazil) - Finance Code 001, and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico - CNPq (Brazil) for fellowships and research grants; to Dr Warlen Silva da Costa for support in the statistical analysis. We would also like to thank the reviewers and editors for all of their careful, constructive and insightful comments on our manuscript. This study was financed in part by CNPq and by Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ). The study was part of the doctoral thesis of the first author at Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Vegetal of Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro.

REFERENCES

- Almeida, A.F.; Jardim, M.A.G. 2012. A utilização das espécies arbóreas da floresta de várzea da Ilha de Sororoca, Ananindeua, Pará, Brasil por moradores locais. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Ambientais, 23: 48-54.

- Alves, G.; Albernaz, A.L.K.M.; Lopes, M.A. 2014. Palmeiras do Distrito Florestal Sustentável da BR-163 Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Belém, 50p.

- Alvez-Valles, C.M.; Balslev, H.; Garcia-Villacorta, R.; Carvalho, F.A.; Menini Neto, L. 2018. Palm species richness, latitudinal gradients, sampling effort, and deforestation in the Amazon region. Acta Botanica Brasilica, 32: 527-539.

- Ammann, S. 2014. Etnobotânica de árvores e palmeiras em três comunidades ribeirinhas do rio Jauaperi, na divisa entre Roraima e Amazonas Master’s dissertation, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, Brazil, 83p. (https://bdtd.inpa.gov.br/handle/tede/1646).

» https://bdtd.inpa.gov.br/handle/tede/1646 - Anderson, A.B. 1977. Os nomes e usos de palmeiras de uma tribo de índios Yanomama. Acta Amazonica, 7: 5-13.

- Araújo, F.R.; González-Pérez, S.E; Lopes, M.A.; Viégas, I.J.M. 2016. Ethnobotany of babassu palm (Attalea speciosa Mart.) in the Tucuruí lake protected areas mosaic - eastern Amazon. Acta Botanica Brasilica, 30: 193-204.

- Araújo, F.R.; Lopes, M.A. 2012. Diversity of use and local knowledge of palms (Arecaceae) in eastern Amazonia. Biodiversity and Conservation, 21: 487-501.

- Arruda, J.C. 2013. Conhecimento ecológico, usos e manejo de palmeiras pelos Quilombolas de Vila Bela da Santíssima Trindade, Mato Grosso Brasil Master’s dissertation, Universidade do Estado de Mato Grosso, Brazil, 112p. (http://portal.unemat.br/media/oldfiles/ppgca/docs/Joari_Costa_de_Arruda.pdf)

- Balslev, H.; Eiserhardt, W.L.; Kristiansen, T.; Pedersen, D.; Grandez, C. 2010. Palms and palm communities in the upper Ucayali river valley-a little-known region in the Amazon basin. Palms, 54: 57-72.

- Balslev, H.; Kahn, F.; Millan, B.; Svenning, J.C.; Kristiansen, T.; Borchsenius, F.; Pedersen, D.; Eiserhardt, W.L. 2011. Species diversity and growth forms in tropical American palm communities. Botanical Review, 77: 381-425.

- Bernal, R.; Torres, C.; García, N.; Isaza, C.; Navarro, J.; Vallejo, M.I.; Galeano, G.; Balslev, H. 2011. Palm Management in South America. The Botanical Review, 77: 607-646.

- Carney, J.; Hiraoka, M. 1997. Raphia taedigera in the Amazon Estuary. Principes, 41: 125-130.

- Campos, M.T.; Ehringhaus, C. 2003. Plant virtues are in the eyes of the beholders: a comparison of known palm uses among indigenous and folk communities of southwestern Amazon. Economic Botany, 57: 324-344.

- Clement, C.R.; Lleras, E.; van Leeuwen, J. 2005. O potencial das palmeiras tropicais no Brasil: acertos e fracassos das últimas décadas. Agrociência, 9: 67-71.

- Costa, J.R.; van Leewen, J.; Costa, J.N. 2005. Tucumã do Amazônas. In: Shanley, P.; Medina, G. (Org.). Frutíferas e Plantas Úteis na Vida Amazônica CIFOR, Imazon, Belém, p.215-214.

- Cymerys, M. 2005. Bacaba. In: Shanley, P.; Medina, G. (Org.). Frutíferas e Plantas Úteis na Vida Amazônica CIFOR, Imazon, Belém, p.177-180.

- Cymerys, M.; Clement, C.R. 2005. Pupunha. In: Shanley, P.; Medina, G. (Org.). Frutíferas e Plantas Úteis na Vida Amazônica CIFOR, Imazon, Belém, p.203-208.

- Cymerys, M.; Fernandes, N.M.P.; Rigamonte-Azevedo, O.C. 2005. Buriti. In: Shanley, P.; Medina, G. (Org.). Frutíferas e Plantas Úteis na Vida Amazônica CIFOR, Imazon, Belém, p.181-187.

- Cymerys, M.; Shanley, P. 2005. Açaí. In: Shanley, P.; Medina, G. (Org.). Frutíferas e Plantas Úteis na Vida Amazônica CIFOR, Imazon, Belém, p.163-170.

- Coradin, L.; Camillo, J.; Pareyn, F.G.C. 2018. Espécies Nativas da Flora Brasileira de Valor Econômico Atual ou Potencial: Plantas Para o Futuro: Região Nordeste. MMA, Distrito Federal, 1311p.

- Dransfield, J. 1978. Growth form of rain forest palms. In: Tomlinson, P.B.; Zimmermann, M.H. (Ed.). Tropical Trees as Living Systems, Cambridge University Press, New York. p.247-268.

- El-Mously, H. 2019. Rediscovering Date Palm by-products: an opportunity for sustainable development. Materials Research Proceedings, 11: 3-61. doi.org/10.21741/9781644900178-1

» https://doi.org/doi.org/10.21741/9781644900178-1 - Farias, M.S.; Oliveira, L.C.; Figueiredo, S.M.M.; Pereira, L.R.; Rodrigues, E. 2016. Diversidade e uso de palmeiras da mata ciliar do rio Acre. In: Siviero, A.; Ming, L.C.; Silveira, M.; Daly, D.C.; Wallace, R.H. (Org.). Etnobotânica e Botânica Econômica do Acre Edufac, Rio Branco, p.111-119.

- Ferreira, E. 2005. Açaí solteiro. In: Shanley, P.; Medina, G. (Org.). Frutíferas e Plantas Úteis na Vida Amazônica CIFOR, Imazon, Belém, p.171-175.

- Flora do Brasil 2020. Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro. ( (http://www.floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br ). Acessed on 10 Sep 2020.

» http://www.floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br - Flores, A.S.; Lima, D.L. 2013. Fibras vegetais utilizadas no artesanato comercializado em Boa Vista, Roraima. Boletim do Museu Integrado de Roraima, 7: 35-39.

- Fonte, A.P.N. 2015. Uasei, o Livro do Açaí: Saberes do Povo Karipuna Iepé, São Paulo, 76p.

- Germano, C.M.; Lucas, F.C.A.; Martins, A.C.C.T.; Moura, P.H.B.; Lobato, G.J.M. 2014. Comunidades ribeirinhas e palmeiras no município de Abaetetuba, Pará, Brasil. Scientia Plena, 10: 111701.

- Gomes-Silva, D.A.P. 2005. Patauá. In: Shanley, P.; Medina, G. (Org.). Frutíferas e Plantas Úteis na Vida Amazônica CIFOR, Imazon, Belém, p.197-202.

- González, O.M.; Barrigas, H.L.; Andino, N.; García, A.; Guachambala, M. 2019. Innovative bio-composite sandwich wall panels made of coconut bidirectional external veneers and balsa lightweight core as alternative for eco-friendly and structural building applications in high-risk seismic regions. Materials Science and Engineering C, 11: 88-98. doi.org/10.21741/9781644900178-5

» https://doi.org/doi.org/10.21741/9781644900178-5 - Jardim, M.A.G.; Cunha, A.C.C. 1998. Usos de palmeiras em uma comunidade ribeirinha da do estuário Amazônico. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Ciências Naturais, 14: 69-77.

- Jardim, M.A.G.; Stewar, P.J. 1994. Aspectos etnobotânicos e ecológicos de palmeiras no município de Novo Airão, estado do Amazonas, Brasil. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Ciências Naturais, 10: 69-76.

- Kanh, F.; de Granville, J.J. 1992. Palms in Florest Ecosystems of Amazonia. Ecological Studies, Springer Verlag, New York. 226p.

- Henderson, A. 2011. A revision of Desmoncus (Arecaceae). Phytotaxa, 35: 1-88.

- Lima, L.P.; Guerra, G.A.D.; Ming, L.C.; Macedo, M.R.A. 2013. Ocorrência e usos do tucumã (Astrocaryum vulgare Mart.) em comunidades ribeirinhas, quilombolas e de agricultores tradicionais no município de Irituia, Pará. Amazônica, Revista de Antropologia, 5: 762-778.

- Lorenzi, H.; Noblick, L.R.; Kahn, F.; Ferreira, E. 2010. Flora Brasileira: Arecaceae (Palmeiras) Instituto Plantarum, Nova Odessa, 384p.

- Macía, M.J.; Armesilla, P.J; Cámara-Leret, R.; Paniagua-Zambrana, N.; Villalba, S. Balslev, H.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. 2011. Palm uses in northwestern south America: A quantitative review. Botanical Review, 77: 462-570.

- Muscarella, R.; Emilio, T.; Phillips, L.O.; Lewis, S.L.; Slik, F.; Baker, W.L.; et al 2020. The global abundance of tree palms. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 29: 1495-1514.

- Miranda, I.P.A.; Rabelo, A.; Bueno, C.R.; Barbosa, E.M.; Ribeiro, M.N.S. 2001. Frutos de Palmeiras da Amazônia Editora INPA, Manaus, 120p.

- Miranda, I.P.A.; Rabelo, A. 2008. Guia de Identificação das Palmeiras de Porto Trombetas/Pará Editora INPA, Manaus , 112p.

- Oliveira, J.; Almeida, S.S.; Vilhena-Potyguara, R.; Lobato, L.C.B. 1991. Espécies vegetais produtoras de fibras utilizadas por comunidades amazônicas. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Ciências Naturais, 7: 393-428.

- Oliveira, J.; Potiguara, R.C.V.; Lobato, L.C.B. 2006. Fibras vegetais utilizadas na pesca artesanal na microrregião do Salgado, Pará. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Ciências Naturais, 1: 113-127.

- Pennas, L.G.A.; Cattani, I.M; Leonardi, B.; Seyam, A-F.M.; Midani, M.; Monteiro, A.S.; Baruque-Ramos, J. 2019. Textile palm fibers from Amazon biome. Materials Research Proceedings, 11: 262-274.

- Pinheiro, C.U.B.; Santos, V.M.; Ferreira, F.R.R. 2005. Usos de subsistência de espécies vegetais na região da baixada maranhense. Amazônia: Ciência & Desenvolvimento, 1: 235-250.

- R Core Team. 2021. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. ( (http://www.rproject.org ). Acessed on 23 Jul 2021.

» http://www.rproject.org - Ribeiro, A.H. 2010. O buriti (Mauritia flexuosa L.f) na terra indígena Aracá, Roraima: usos tradicionais, manejo e potencial produtivo. Master’s dissertation, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia, Brazil, 90p. (https://bdtd.inpa.gov.br/handle/tede/1103)

- Rocha, A.E.S. 2017. Guia de Coleta e Identificação de Palmeiras Nativas do Estado do Pará Editora do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Belém. 4p.

- Rocha, A.E.S.; Silva, M.F.F. 2005. Aspectos fitossociológicos, florísticos, etnobotânicos das palmeiras (Arecaceae) de floresta secundária no município de Bragança, PA, Brasil. Acta Botanica Brasilica, 19: 657-667.

- Rodrigues, L.M.B.; Lira, A.U.S.; Santos, F.A.; Jardim, M.A.G. 2006. Composição florística e usos das espécies vegetais de dois ambientes de floresta de várzea. Revista Brasileira de Farmácia, 87: 45-48.

- Salm, R.; Albernaz, A.L.K.M.; Jardim, M. 2011. Abundance and diversity of palms in the sustainable forest district of BR 163, Pará Brazil. Biota Neotropica, 11: 99-105.

- Sander, N.L.; Silva, C.J.; Arruda, J.C.; Morais, M.; Lázaro, W.L.; Barros, F.B.; Silva, M.T.P. 2018. Non-timber forest products of Mauritia flexuosa L.f.: Loss or permanence in quilombola communities of southern Amazon? Revista Ibero-Americana de Ciências Ambientais, 9: 43-55.

- Santos, R.S.; Coelho-Ferreira, M. 2012. Estudo etnobotânico de Mauritia flexuosa L.f. (Arecaceae) em comunidades ribeirinhas do Município de Abaetetuba, Pará, Brasil. Acta Amazonica, 42: 1-10.

- Santos, R.S.; Coelho-Ferreira, M.; Lima, P.G.C. 2016. Espécies fibrosas em mercados do Distrito Florestal Sustentável da BR-163. Biota Amazônia, 6: 101-109.

- Shanley, P.; Medina, G.S. 2005. Frutiferas e Plantas Úteis na Vida Amazônica CIFOR/Imazon, Belém, 300p.

- Smith, N. 2015. Palms and People in the Amazon Geobotany Studies (Basics, Methods and Case Studies) Springer, Switzerland. 513p.

- Smith, N.; Plagnol, D.V. 2016. Conhecimento e uso de espécies vegetais arbóreas pelos seringueiros da Reserva Extrativista do Alto Juruá, Acre. In: Siviero, A.; Ming, L.C.; Silveira, M.; Daly, D.C.; Wallace, R.H. (Org.). Etnobotânica e Botânica Econômica do Acre Edufac, Rio Branco , p.53-66.

- Sneath, P.H.; Sokal, R.R. 1973. Numerical Taxonomy: The Principles and Practice of Numerical Classification W.H. Freeman, San Francisco. 573p.

- SpeciesLink. 2021. Centro de Referência em informação Ambiental-CRIA ( (http://www.splink.org.br/index?lang=pt ). Acessed on 07 Apr 2021.

» http://www.splink.org.br/index?lang=pt - Soares, K.P.; Lorenzi, H.; Vianna, S.A.; Leitman, P.M.; Heiden, G.; Moraes R.M.; Martins, R.C.; Campos-Rocha, A.; Ellert-Pereira, P.E.; Eslabão, M.P. 2020. Arecaceae in Flora do Brasil 2020. Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro. ( (http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/reflora/floradobrasil/FB53 ). Acessed on 11 Nov 2020.

» http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/reflora/floradobrasil/FB53 - Souza, M.O. 2010. Sustentabilidade das formas de uso e manejo de matas ciliares na área lacustre de Penalva, Baixada Maranhense. Master’s dissertation, Universidade Federal do Maranhão, Brazil, 87p. (http://livros01.livrosgratis.com.br/cp142514.pdf)

» http://livros01.livrosgratis.com.br/cp142514.pdf - Trindade, A.A.; Máximo, F.H.D. 2017. Desdobro de estipe de pupunha (Bactris gasipaes Kunth) para novos produtos. Mix Sustentável, 3: 123-132.

- Thoma, A.C.; Aguiar, N.C.; Prat, B.V.; Cambraia, R.P. 2016. Palmeiras nativas indicadas para uso em construções. Revista Científica Vozes dos Vales, 10: 1-13.

- Valente, R.M.; Almeida, S.S. 2001. As Palmeiras de Caxianã: Informações Botânicas e Utilização por Comunidades Ribeirinhas Museu Paraense Emilio Goeldi, Belém, 54p.

- Vilhena-Potiguara, R.C.; Almeida, S.S.; Oliveira, J.; Lobato, L.C.B.; Lins, A.L.F.A. 1987. Plantas Fibrosas - I. Levantamento botânico na microrregião do Salgado (Pará, Brasil). Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, 3: 279-301.

- Wallace, A.R. 2014. Palmeiras da Amazônia e Seus Usos EDUA, Manaus, 165p.

- Wallace, R.H.; Ferreira, E.J.L. 2016. Usos, extração e potencial de produção de frutos de três espécies de palmeiras nativas na Reserva Extrativista Chico Mendes, Acre: implicações para a extração comercial. In: Siviero, A.; Ming, L.C.; Silveira, M.; Daly, D.C.; Wallace, R.H. (Org.). Etnobotânica e Botânica Econômica do Acre [ebook]. Edufac, Rio Branco , p.288-298.

- Zambrana, N.Y.P.; Byg, A.; Svenning, J.C.; Moraes, M.; Grandez, C.; Balslev, H. 2007. Diversity of palm uses in the western Amazon. Biodiversity Conservation, 16: 2771-2787.

-

CITE AS:

Kikuchi, T.Y.P.; Callado, C.H. 2021. Brazilian Amazonian palm-stem types and uses: a review. Acta Amazonica 51: 334-346.

Edited by

ASSOCIATE EDITOR:

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

10 Dec 2021 -

Date of issue

Oct-Dec 2021

History

-

Received

14 Dec 2020 -

Accepted

21 Sept 2021