Abstracts

Little is known about the role of protists and bacteria interactions during hydrocarbon biodegradation. This work focused on the effect of oil on protists from three different locations in Guanabara Bay and bacteria from Caulerpa racemosa (BCr), Dictyota menstrualis (BDm) and Laurencia obtusa (BLo) during a 96 h bioassay. Cryptomonadida (site 1, 2 and 3), Scuticociliatida (site 2) and Euplotes sp.1 and Euplotes sp.2 (site 3) appeared after incubation. The highest biomass observed in the controls was as follows: protist site 3 (6.0 µgC.cm–3, 96 h) compared to site 3 with oil (0.7 µgC.cm–3, 96 h); for bacteria, 8.6 µgC.cm–3(BDm, 72 h) and 17.0 µgC.cm–3(BCr with oil, 24 h). After treatment, the highest biomasses were as follows: protists at site 1 and BLo, 6.0 µgC.cm–3 (96 h), compared to site 1 and BLo with oil, 3.31 µgC.cm–3 (96 h); the bacterial biomass was 43.1 µgC.cm–3 at site 2 and BDm (96 h). At site 3 and BLo with oil, the biomass was 18.21 µgC.cm–3 (48 h). The highest biofilm proportions were observed from BCr 1.7 µm (96 h) and BLo with oil 1.8 µm (24 h). BCr, BLo and BDm enhanced biofilm size and reduced the capacity of protists to prey.

bacterial consortia; biomass; free living protist; Guanabara Bay; microbial loop; petroleum

Pouco se sabe sobre o papel dos protistas e as interações bacterianas durante a biodegradação de hidrocarbonetos. Este trabalho se concentrou no efeito do óleo sobre protistas de três localidades diferentes na Baía de Guanabara e bactérias de Caulerpa racemosa(BCr), Dictyota menstrualis(BDm) e Laurencia obtusa(BLo) durante 96 h de bioensaio. Cryptomonadida (locais 1 , 2 e 3), Scuticociliatida (local 2) e Euplotes sp.1 e Euplotes sp.2 (local 3) apareceram após incubação. As biomassas mais elevadas observadas nos controles foram como se segue: protista local 3 (6,0 µgC.cm–3, 96 h) comparado com o local 3 com óleo (0,7 µgC.cm–3, 96 h); para as bactérias, 8,6 µgC.cm–3 (BDm, 72 h) e 17,0 µgC.cm–3 (BCr com óleo, 24 h). Após o tratamento, as maiores biomassas foram como se seguem: protistas no local 1 e BLo, 6,0 µgC.cm–3 (96 h), em comparação com o local 1 e BLo com óleo, 3,31 µgC.cm–3 (96 h), a biomassa bacteriana foi de 43,1 µgC.cm–3 no local 2 e BDm (96 h). No local 3 e BLo com óleo, a biomassa foi 18,21 µgC.cm–3 (48 h). As maiores proporções de biofilme foram observadas de 1,7 µm BCr(96 h) a 1,8 µm BLo com óleo (24 h). BCr, BLo e BDm aumentaram o tamanho do biofilme e reduziram a capacidade dos protistas predarem.

consórcio bacteriano; biomassa; protista de vida livre; Baía de Guanabara; alça microbiana; petróleo

INTRODUCTION

Protists are unicellular eukaryotes that are widespread in all types of habitats (Buck et al. 2000Buck KR, Barry JP and Simpson AGB. 2000. Monterey Bay cold seep biota: Euglenozoa with chemoautotrophic bacterial epibionts. Eur J Protistol 36: 117-126., Laybourn-Parry et al. 2000Laybourn-Parry J, Mell EM and Roberts EC. 2000. Protozoan growth rates in Antarctic lakes. Polar Biol 23: 445-451., Pedros-Alio et al. 2000Pedros-Alio C, Calderon-Paz I, Maclean MH, Medina G, Marrase C, Gasol JM and Guixa-Boixereu N. 2000. The microbial food web along salinity gradients. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 32: 143-155., Scott et al. 2001Scott FJ, Davidson AT and Marchant HJ. 2001. Grazing by the Antarctic sea ice ciliate Pseudocohnilembus. Polar Biol 24:127-131.). They are an essential component of microbial food webs, and their phagotrophic activities release waste products into the environment, both as dissolved and particulate organic matter from the undigested components of prey bacteria (Nagata and Kirchman 1992aNagata T and Kirchman DL. 1992a. Release of dissolved organic matter by heterotrophic protozoa: implications for microbial food webs. Archiv fuer Hydrobiologie, Beiheft Ergebnisse Limnologie 35: 99-109., bNagata T and Kirchman DL. 1992b. Release of macromolecular organic complexes by heterotrophic marine flagellates. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 83: 233-240.) and as dissolved inorganic nutrients, particularly ammonium and phosphate (Caron and Goldman 1990Caron DA and Goldman JC. 1990. Protozoan nutrient regeneration. In: Capriulo GM (Ed), Ecology of Marine Protozoa, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 283-306., Dolan 1997Dolan JR. 1997. Phosphorus and ammonia excretion by planktonic protists. Mar Geol 139: 109-122.). Thus, protist grazing provides substrates for the further growth of prey, which include both heterotrophic bacteria (Jumars et al. 1989Jumars PA, Penry DL, Baross JA, Perry MJ and Frost BW. 1989. Closing the microbial loop: dissolved carbon pathway to heterotrophic bacteria from incomplete ingestion, digestion and absorption in animals. Deep-Sea Res 36: 483-495., Christaki et al. 1999Christaki U, Van Wambeke F and Dolan JR. 1999. Nanoflagellates (mixotrophs, heterotrophs, and autotrophs) in the oligotrophic eastern Mediterranean: standing stocks, bacterivory and relationships with bacterial production. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 181: 297-307.) and autotrophic cells (Dolan 1997Dolan JR. 1997. Phosphorus and ammonia excretion by planktonic protists. Mar Geol 139: 109-122.).

Protists are similar in size to their microbial prey, including bacteria, algae, and other heterotrophic protists. Their growth potential is the same as their microbial prey, and the high rate of protist metabolism facilitates carbon and energy flux through ecosystems (Fenchel 1987Fenchel T. 1987. Ecology of Protozoa: The Biology of Free-living Phagotrophic Protists. Berlin: Springer, 197 p., Sherr and Sherr 1994Sherr EB and Sherr BF. 1994. Bacterivory and herbivory: key roles of phagotrophic protists in pelagic food webs. Microb Ecol 28: 223-235.).

Bacteria are present in sediment in large numbers (approximately 1010 cells.g–1). Their biomass is greater than the biomass of all other benthic organisms due to the structure and function of microbial biofilms. They possess a high surface to volume ratio, which is indicative of high metabolic rates. Dissolved inorganic and organic substrates can be metabolized with high substrate affinity and specificity. Particulate organic matter can be decomposed in close contact with the substrate by using hydrolytic enzymes (Silva et al. 2010Silva FS, Santos ES, Laut LLM, Sanchez-Nuñes ML, Fonseca EM, Baptista-Neto JA, Mendonça-Filho JG and Crapez MAC. 2010. Geomicrobiology and Biochemical Composition of Two Sediment Cores from Jurujuba Sound - Guanabara Bay – SE Brazil. Anu Inst Geocienc 33:73-84., Guerra et al. 2011Guerra LV, Savergnini F, Silva FS, Bernardes MC and Crapez MAC. 2011. Biochemical and microbiological tools for the evaluation of environmental quality of a coastal lagoon system in Southern Brazil. Braz J Biol 71: 461-468.). Other than oxygen, microorganisms use alternative electron acceptors (nitrate, manganese, iron, sulfate, and carbon dioxide) for the assimilation of organic material (Edwards et al. 2005Edwards KJ, Bach W and McCollom TM. 2005. Geomicrobiology in oceanography: microbe-mineral interactions at and below the seafloor. Trends Microbiol 13: 449-455.).

Oil is a complex mixture of recalcitrant and toxic substances (Wilkinson et al. 2002Wilkinson S, Nicklin S and Faull JL. 2002. Biodegradation of fuel oils and lubricants: Soil and water bioremediation options. In: Singh VP and Stapleton RD (Eds), Progress in Industrial Microbiology 36: 69-100.) and is able to disrupt cellular homeostasis (Sikkema et al. 1995Sikkema J, Bont JA and Poolman B. 1995. Mechanisms of membrane toxicity of hydrocarbons. Microbiol Rev 59: 201-222., Crapez 2001Crapez MAC. 2001. Efeitos de hidrocarbonetos de petróleo na biota marinha. In: MORAES R, CRAPEZ MAC, PFEIFFER W, FARINA M, BAINY A AND TEIXEIRA V (Eds), Efeitos dos Poluentes em Organismos Marinhos, São Paulo: Arte e Ciência-Vilipress, p. 255-270.). Some microorganisms utilize oil as a carbon and energy source (Crapez et al. 2001, Ron and Rosenberg 2002Ron EZ and Rosenberg E. 2002. Biosurfactants and oil bioremediation. Curr Opin Biotechnol 13: 249-252.), and oil degradation is a multi-step process in which each step is performed via distinct processes performed by different functional groups from various microbial organisms (Dalby et al. 2008Dalby AP, Kormas KAR, Christaki U and Karayanni H. 2008. Cosmopolitan heterotrophic microeukaryotes are active bacterial grazers in experimental oil-polluted systems. Environ Microbiol 10: 47-56.).

Despite the ecological importance of protists in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, relatively little is known about their role in hydrocarbon degradation compared to the reported role of bacteria. A more detailed knowledge of the role of protists in microbial interactions with hydrocarbons is essential to trace and model the fate of hydrocarbon contaminants in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems.

This work aims to study the influence of oil (Light Arabian oil) on bacteria isolated from three seaweed samples and protists isolated from the sediment of Guanabara Bay during a 96 hour bioassay.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Area

Guanabara Bay is located in the state of Rio de Janeiro in Southeast Brazil, between 22°40′-23°00′S latitude and 043°00′–043°18′W longitude. It is one of the largest bays along the Brazilian coastline and has an area of approximately 384 km2 including its islands. The bay has a complex bathymetry with a relatively flat central channel that is 400 m wide that stretches more than 5 km into the bay and is defined by the 30 misobath. The deepest point of the bay (58 m) is located within this channel (Kjerfve et al. 1997Kjerfve B, Ribeiro CA, Dias GTM, Filippo A and Quaresma VS. 1997. Oceanographic characteristics of an impacted coastal bay: Baia de Guanabara, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Cont Shelf Res 17: 1609-1643.). According to the same authors, north of the Rio de Janeiro -Niterói Bridge, the channel loses its characteristic features as the bay rapidly becomes shallower due to high rates of sedimentation, with an average depth of 5.7 m, which has accelerated in the past century due to anthropogenic activities in the catchment area.

The drainage basin of Guanabara Bay has an area of 4,080 km2 and consists of 32 separate sub-watersheds (Kjerfve et al. 1997Kjerfve B, Ribeiro CA, Dias GTM, Filippo A and Quaresma VS. 1997. Oceanographic characteristics of an impacted coastal bay: Baia de Guanabara, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Cont Shelf Res 17: 1609-1643.). However, only six of the rivers are responsible for 85% (JICA 1994) of the 100 m3.s–1 of the total mean annual freshwater input. Currently, 11 million inhabitants live in the greater Rio de Janeiro metropolitan area, which discharges tons of untreated sewage directly into the bay (Carreira et al. 2002Carreira RS, Wagener ALR, Readman JW, Fileman TW, Macko SA and Veiga A. 2002. Change in the sedimentary organic carbon pool of a fertilized tropical estuary, Guanabara Bay, Brazil: an elemental, isotopic and molecular marker approach. Mar Chem 79: 207-227.). There are more than 12,000 industries located in the drainage basin accounting for 25% of the organic pollution released into the bay. The bay also hosts two oil refineries along its shore that process 7% of the national oil. At least 2,000 commercial ships dock in the port of Rio de Janeiro every year, making it the second largest harbor in Brazil. The bay is also the homeport of two naval bases, a shipyard, and a large number of ferries, fishing boats, and yachts (FEEMA 1990). Recently, the chronically stressed environment has selected microorganisms able to cleave toxic compounds and form inter- or intra-specific microbial consortia to improve their survival (Crapez 2001Crapez MAC. 2001. Efeitos de hidrocarbonetos de petróleo na biota marinha. In: MORAES R, CRAPEZ MAC, PFEIFFER W, FARINA M, BAINY A AND TEIXEIRA V (Eds), Efeitos dos Poluentes em Organismos Marinhos, São Paulo: Arte e Ciência-Vilipress, p. 255-270., Crapez 2002Crapez MAC. 2002. Bactérias marinhas. In: Pereira RC and Soares-Gomes A (Eds), Biologia Marinha, Rio de Janeiro: Interciência, p. 81-101., Fontana et al. 2006Fontana LF, Silva FS, Krepsky N, Barcelos MA and Crapez MAC. 2006. Natural attenuation of aromatic hydrocarbon from sandier sediement in Boa Viagem, Guanabra Bay, RJ, Brazil. Geochimica Brasiliensis 20: 78-86, 2006., Krepsky et al. 2007Krepsky N, Fontana LF, Silva FS and Crapez MAC. 2007. Alternative methodology for biossurfactant production. Braz J Biol 67: 117-124.).

In this study, sediments at three different locations were sampled (Fig. 1). Site 1 is located in the northwest of the bay at Ilha do Governador (22°46.589′ S, 43°11.424′ W). This site has fine sand, coarse silt, a total organic carbon value near 5.2% of the sediment dry weight, and an input of 458 g.C.m–2. year–1 of organic matter (Carreira et al., 2002Carreira RS, Wagener ALR, Readman JW, Fileman TW, Macko SA and Veiga A. 2002. Change in the sedimentary organic carbon pool of a fertilized tropical estuary, Guanabara Bay, Brazil: an elemental, isotopic and molecular marker approach. Mar Chem 79: 207-227.).

Site 2 is located in the east of the bay at São Gonçalo's eutrophic river (22°51.064′ S, 43°06.697′ W). This site has medium silt and large space heterogeneity in sediment properties. The organic carbon measured was approximately 1.6% in this sediment (Carreira et al. 2002Carreira RS, Wagener ALR, Readman JW, Fileman TW, Macko SA and Veiga A. 2002. Change in the sedimentary organic carbon pool of a fertilized tropical estuary, Guanabara Bay, Brazil: an elemental, isotopic and molecular marker approach. Mar Chem 79: 207-227.).

Site 3 is located at the entrance of the bay (22°59′01.1″S, 43° 04′59.8″ W). This site has moderately well-sorted medium sand and a very low percentage of total organic carbon, ranging from 0.82-3.1% (Carreira et al. 2002Carreira RS, Wagener ALR, Readman JW, Fileman TW, Macko SA and Veiga A. 2002. Change in the sedimentary organic carbon pool of a fertilized tropical estuary, Guanabara Bay, Brazil: an elemental, isotopic and molecular marker approach. Mar Chem 79: 207-227.).

Medium and Selection of Protists

The sediment samples were prepared according to Dragesco and Dragesco-Kernéis (1986)Dragesco J and Dragesco-Kernéis A. 1986. Ciliés libres de l'Afrique intertropicale. Introduction à connaissance et à l'etude des ciliés. Faune Tropicale 26: 1-559. 3-4 hours after sampling. When free-living protists excysted, they were stored at 30°C for the maintenance of living bacteria and the short microbial loop (Fenchel 1987Fenchel T. 1987. Ecology of Protozoa: The Biology of Free-living Phagotrophic Protists. Berlin: Springer, 197 p., Krepsky et al. 2007Krepsky N, Fontana LF, Silva FS and Crapez MAC. 2007. Alternative methodology for biossurfactant production. Braz J Biol 67: 117-124.). All protist specimens were selected using glass micropipettes after six months of incubation. The protists were maintained in the laboratory in liquid medium containing coarse powdered rice at room temperature (Dragesco and Dragesco-Kernéis 1986Dragesco J and Dragesco-Kernéis A. 1986. Ciliés libres de l'Afrique intertropicale. Introduction à connaissance et à l'etude des ciliés. Faune Tropicale 26: 1-559.). The identification of the protists was performed with a light microscope (Dragesco and Dragesco-Kernéis 1986Dragesco J and Dragesco-Kernéis A. 1986. Ciliés libres de l'Afrique intertropicale. Introduction à connaissance et à l'etude des ciliés. Faune Tropicale 26: 1-559.), a BX 41 from Olympus, using the Protargol technique (Silva-Neto 2000Silva-Neto ID. 2000. Improvement of silver impregnation technique (Protargol) to obtain morphological features of protists ciliates, flagellates and opalinates. Rev Bras Biol 60: 451-459.).

Medium and Selection of Bacterial Consortia

The bacterial consortia were sampled from the surface of the seaweeds Caulerpa racemosa (Forsskål) (Agardh 1873), Laurencia obtusa (Huds) (Lamouroux 1813), and Dictyota menstrualis (Hoyt) (Shnetter et al. 1987), according to Silva et al. (2005)Silva FS, Krepsky N, Teixeira VL and Crapez MAC. 2005. Estímulo da produção de biossurfactante por extrato da alga vermelha Digenea simplex (WULFEN) C. AGARDH em comunidades bacterianas da praia de Boa Viagem (RJ). In: Série Livros 10 do Museu Nacional do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro: Museu Nacional do Rio de Janeiro, p. 469-483.. They were maintained according to Krepsky et al. (2007)Krepsky N, Fontana LF, Silva FS and Crapez MAC. 2007. Alternative methodology for biossurfactant production. Braz J Biol 67: 117-124., and oil was the source of both carbon and energy (Silva et al. 2005Silva FS, Krepsky N, Teixeira VL and Crapez MAC. 2005. Estímulo da produção de biossurfactante por extrato da alga vermelha Digenea simplex (WULFEN) C. AGARDH em comunidades bacterianas da praia de Boa Viagem (RJ). In: Série Livros 10 do Museu Nacional do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro: Museu Nacional do Rio de Janeiro, p. 469-483.). Throughout the manuscript, the bacterial consortia are termed BCr (C. racemosa), BLo (L. obtusa) and BDm (D. menstrualis).

Bioassay

The organic carbon or biomass (µgC.cm–3) of the protists and the bacteria BCr, BLo and BDm were quantified according to Gomes et al. (2007)Gomes EAT, Santos VSD, Tenenbaum DR and Villac MC. 2007. Protozooplankton characterization of two contrasting sites in a tropical coastal ecosystem (Guanabara Bay, RJ). Braz J Oceanogr 55: 29-38., Mauclaire et al. (2003)Mauclaire L, Pelza O, Thullnera M, Abrahamb W and Zeyer J. 2003. Assimilation of toluene carbon along a bacteria-protist food chain determined by 13C-enrichment of biomarker fatty acids. J Microbiol Methods 55: 635-549., Carlucci et al. (1986)Carlucci AF, Craven DB, Robertson KJ and Williams PM. 1986. Surface-film microbial populations: diel amino acid metabolism, carbon utilization, and growth rates. Mar Biol 92: 289-297. and Kepner and Pratt (1994)Kepner RL and Pratt JR. 1994. Use of fluorochromes for direct enumeration of total bacteria in environmental samples: past and present. Microbiol Rev 58: 603-615., respectively. The bioassay was performed at 0, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h at room temperature (Krepsky et al. 2007Krepsky N, Fontana LF, Silva FS and Crapez MAC. 2007. Alternative methodology for biossurfactant production. Braz J Biol 67: 117-124.) in absence of oil. In the bioassay including oil (treatment group), 1 mL of oil was added (Light Arabian oil, from PETROBRAS S.A) and the sample was incubated with shaking for 1 minute (Krepsky et al. 2007Krepsky N, Fontana LF, Silva FS and Crapez MAC. 2007. Alternative methodology for biossurfactant production. Braz J Biol 67: 117-124.). The control groups were analyzed protists with or without consortia. The bacterial proportion, including the capsule that forms the biofilm, and the bacterial cell size were measured with an Olympus microscope, model BX 41, using the phase contrast, PH3 filter (1000 X) (Madigan et al. 2004Madigan TM, Martinko JM and Parker J. 2004. Hábitat microbianos, ciclos de nutrientes e interacciones con plantas y animales. In: Microbiología de los microorganimos, 10th ed., Madri: Prentice Hall, p. 624-687.).

Statistical Analyses

The data were analyzed with Statisoft Statistica 7, using ANOVA and MANOVA tests to analyze the carbon and biofilm results, respectively. Organic carbon data were transformed with arc-sen. Data were considered significant at p≤0.05.

RESULTS

The sediment samples from Guanabara Bay did not contain vegetative protists. They appeared after 3 weeks of laboratory incubation. In the northwest of the bay, at Ilha do Governador (site 1), Cryptomonadida(Senn 1900) was isolated (Kugrens et al. 2000Kugrens P, Lee R and Hill DR. 2000. Flagellated. In: LEE JJ, LEEDALE GF AND BRADBURY P (Eds), The illustrated guide to the protozoa, 2nd ed., Lawrence: Society of Protozoologists, p. 1111-1250.). In the east of the bay, at São Gonçalo's eutrophic river, (site 2), Cryptomonadida and Scuticociliatida (Small 1967) were isolated (Lynn and Small 2000Lynn DH and Small E. 2000. Ciliophora. In: LEE JJ, LEEDALE GF AND BRADBURY P (Eds), The illustrated guide to the protozoa, 2nd ed., Lawrence: Society of Protozoologists, p 371-676.). At the entrance of the bay, Cryptomonadida and two different ciliate species, Euplotes sp.1 and Euplotes sp.2, were isolated (Lynn and Small 2000Lynn DH and Small E. 2000. Ciliophora. In: LEE JJ, LEEDALE GF AND BRADBURY P (Eds), The illustrated guide to the protozoa, 2nd ed., Lawrence: Society of Protozoologists, p 371-676.).

At site 1, Cryptomonadida produced 1.5 µgC.cm–3 (48 h) of biomass in the bioassay control, but in the presence of oil, it only produced 0.4 µgC.cm–3 (24 h). At site 2, Cryptomonadida and Scuticociliatida produced 0.7 µgC.cm–3 (72 h) of biomass in the bioassay control, but in the presence of oil, they produced 0.4 µgC.cm–3 (96 h). At site 3, Cryptomonadida, Euplotes sp.1 and Euplotes sp.2 produced 6.0 µgC.cm–3 of biomass in the bioassay control, but this value was reduced to 0.7 µgC.cm–3 in the presence of oil. The highest biomass was generally observed at the end of the bioassay (72-96 h) (Fig. 2a).

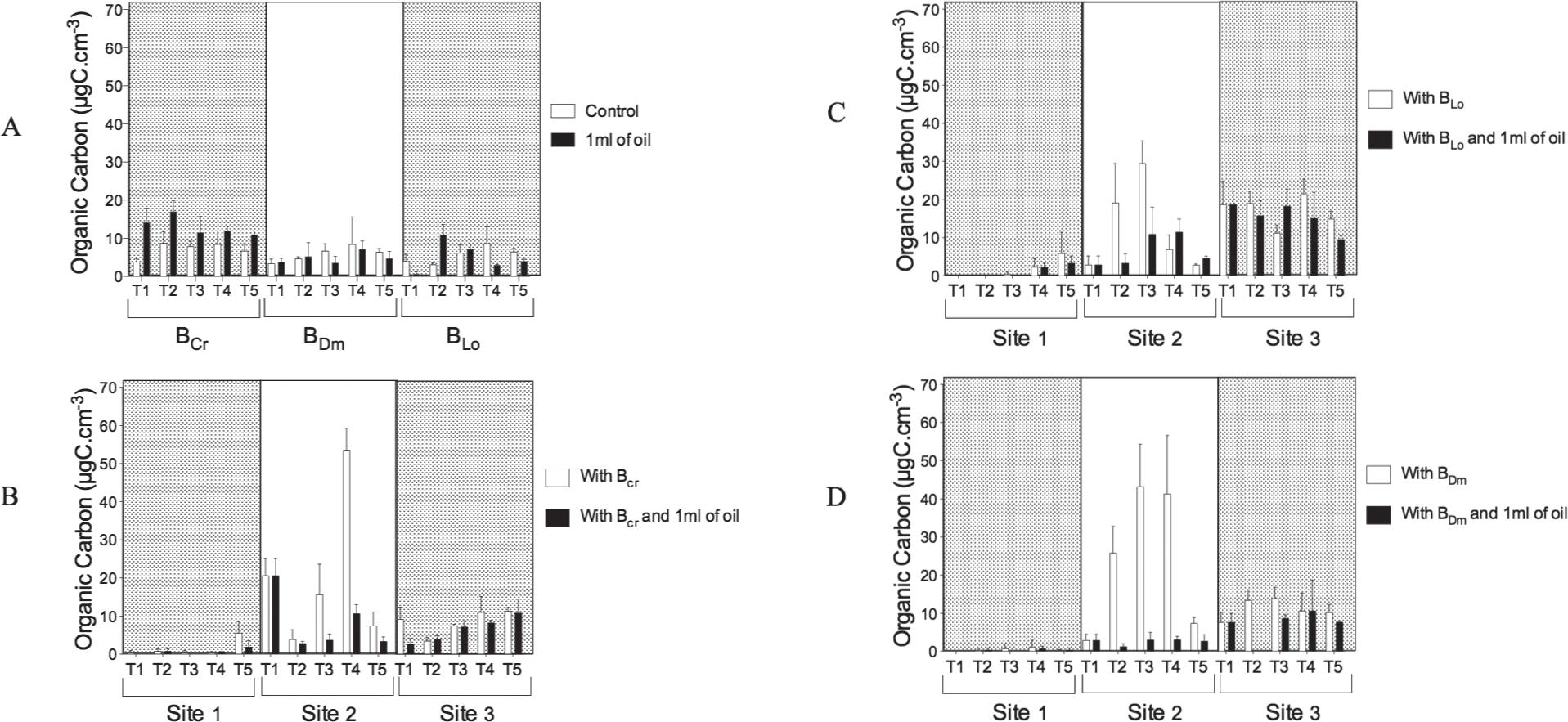

Biomass from protists sampled from Guanabara Bay under influence of Bacterial consortia sampled from seaweed and oil. A-Control; B-With BCr; C-With BDm; D-With BLo.

On the surface of C. racemosa(BCr), L. obtusa (BLo) and D. menstrualis (BDm) bacterial consortia, hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria was observed. The bacterial organic carbon values for the bioassay control were 8.4, 8.4 and 8.6 µgC.cm–3 produced by BCr in 96 h, and by BLo and BDm in 72 h, respectively. In the presence of oil, the organic carbon produced by BCr, BLo and BDm was 17.0 µgC.cm–3 in 24 h, 7.1 µgC.cm–3 in 72 h and 10.9 µgC.cm–3 in 24 h, respectively (Fig. 3a).

Biomass from Bacterial consortia sampled from seaweed under influence of protists sampled from Guanabara Bay and oil. A-Control; B-With BCr; C-With BDm; D-With BLo.

At site 1, Cryptomonadida in contact with the bacterial consortia showed enhanced biomass at the end of the bioassay. In the presence of BCr, BLo and BDm, Cryptomonadida produced 5.0, 6.0 and 0.2 µgC.cm–3 of biomass, respectively, but in the presence of oil, Cryptomonadida produced 2.0, 3.3 and 0.4 µgC.cm–3, respectively, at 96 h (Fig. 2b, c, d).

At site 1, the organic carbon produced by BCr and BLo was 5.5 and 5.9 µgC.cm–3 of biomass at 96 h. BDm produced 1.1 µgC.cm–3 of biomass in 72 h, but in the presence of oil, BCr, BLo and BDmproduced 1.8 and 3.3 µgC.cm–3 at 96 h and 0.7 µgC.cm–3 at 72 h, respectively (Fig. 3b, c, d).

At site 2, Cryptomonadida and Scuticociliatida in the presence of both BCr and BLo produced 1.2 µgC.cm–3 at 72 and 48 h. In the presence of BDm, Cryptomonadida and Scuticociliatida produced 2.2 µgC.cm–3of biomass at 72 h. In the presence of oil, their biomass was reduced to 0.0 µgC.cm–3 in the presence of BCr, and 0.37 µgC.cm–3 in the presence of BLo after 48 h and BDm at 72 h (Fig. 2b, c, d).

At site 2, the bacterial organic carbon produced by BCr was 53.53 µgC.cm–3 of biomass at 72 h, and the carbon produced by BLo and BDm was 29.5 and 43.0 µgC.cm–3 of biomass after 48 h, respectively. However, in the presence of oil, BCr, BLo and BDm produced 10.57, 11.47 and 3.05 µgC.cm–3 at 72 h, respectively (Fig. 3b, c, d).

Cryptomonadida, Euplotes sp.1 and Euplotes sp.2 at site 3 in the presence of BCr or BLo produced a protist organic biomass of 1.9 and 1.1 µgC.cm–3 of biomass at 72 h, respectively. In the presence of BDm, Cryptomonadida, Euplotes sp.1 and Euplotes sp.2 produced 1.5 µgC.cm–3 of biomass at 24 h. In the presence of oil, they produced 1.9 and 0.4 µgC.cm–3 of biomass in the presence of BCr or BLo at 72 h, respectively, and 0.4 µgC.cm–3 after 48 h with BDm (Fig. 2b, c, d).

At site 3, the organic carbon produced by BCr, BLoand BDm was 11.35, 21.34 and 13.90 µgC.cm–3 of biomass at 96, 72 and 48 h, but in the presence of oil, BCr, BLo and BDm produced 10.78, 18.21 and 10.64 µgC.cm–3 at 96, 48 and 72 h, respectively (Fig. 3b, c, d).

At the end of the bioassay, the size of the BCr, BLo and BDm biofilm was 1.5 µm (48 h), 1.5 µm (72 h) and 1.5 µm (72 h), respectively; however, in the presence of oil, the capsule size was 1.7 µm (96 h), 1.6 µm (24 h) and 1.8 µm (24 h), respectively. The BCr, BLo and BDm cell size was 2.5 µm (96 h), 2.0 µm (72 h) and 2.0 µm (48 h), but in the presence of oil, the cell size was 2.3 µm (72 h), 2.2 µm (72 h) and 2.3 µm (96 h), respectively (Fig. 4a, b, c).

Bacterial proportions measured during oil degradation. A-Total size; B-Bacterial capsula size; C-Bacterial cell size.

Statistical analyses showed significant differences between the biomass of protists and bacteria (ANOVA, p≤0.05), but their biomasses were significantly linked at 48 and 72 h of the bioassay (Tukey test, p<0.05). The organic carbon produced by protists was not significantly affected in the bioassays by the presence of oil (Tukey test, p>0.05).

The quantity of organic carbon produced by the bacteria BCr, BLo and BDm was significantly different. The bacterial carbon from BCr and BDm showed significant differences in the bioassay in the presence of protists and oil (Tukey test, p<0.05). Oil also significantly affected the bacterial length in the bioassays (MANOVA, p<0.05).

DISCUSSION

Free-living protists are very common in bodies of water (Fenchel 1987Fenchel T. 1987. Ecology of Protozoa: The Biology of Free-living Phagotrophic Protists. Berlin: Springer, 197 p., Sigee 2005Sigee DC. 2005. Freshwater microbiology: biodiversity and dynamic interactions of microorganisms in the aquatic environment. West Sussex: J Wiley & Sons, 537 p.). Scuticociliatida, Cryptomonadida and Hipotrichea are very common in eutrophized bodies of water, such as the Guanabara Bay (Slàdeček 1973Slàdeček V. 1973. System of water quality from the biological point of view. Arch Hydrobiol Beih Ergebn Limno 7: 1-218., Foissner et al. 1995Foissner W, Berger H, Blatterer H and Kohmann F. 1995. In: Taxonomische und ökologische revision der ciliaten des saprobiensystems - Band IV: Gymnostomates, Loxodes. Munich: Informationsberichte des Bayer Landesamtes für Wasserwirtschaft, 540 p., Paiva and Silva-Neto 2004Paiva TS and Silva-Neto ID. 2004. Ciliate protists from Cabiúnas lagoon (Restinga de Jurubatiba, Macaé, Rio de Janeiro) with emphasis on water quality indicator species and description of Oxytrichamarcili sp. Braz J Biol 64: 465-478.).

In the bioassay controls, protists showed a reduced ability to live in the presence of oil, and their associated bacteria did not utilize oil as a source of carbon and energy (Zarda et al. 1998Zarda B, Mattison G, Hess A, Hahn D, Höhener P and zeyer J. 1998. Analysis of bacterial and protozoan communities in an aquifer contaminated with monoaromatic hydrocarbons. FEMS Micro Ecol 27: 141-152., Mauclaire et al. 2003Mauclaire L, Pelza O, Thullnera M, Abrahamb W and Zeyer J. 2003. Assimilation of toluene carbon along a bacteria-protist food chain determined by 13C-enrichment of biomarker fatty acids. J Microbiol Methods 55: 635-549.).

The hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria C. racemosa(BCr), L. obtusa(BLo) and D. menstrualis(BDm) emulsify hydrocarbon-water mixtures, which enable them to grow on the oil droplets (Crapez 2002Crapez MAC. 2002. Bactérias marinhas. In: Pereira RC and Soares-Gomes A (Eds), Biologia Marinha, Rio de Janeiro: Interciência, p. 81-101., Krepsky et al. 2007Krepsky N, Fontana LF, Silva FS and Crapez MAC. 2007. Alternative methodology for biossurfactant production. Braz J Biol 67: 117-124., Rahman et al. 2003Rahman KSM, Rahman TJ, Kourkoutas Y, Petsas I, Marchant R and Banat IM. 2003. Enhanced bioremediation of n-alkane in petroleum sludge using bacterial consortium amended with rhamnolipid and micronutrients. Bioresour Technol 90: 159-168.). These emulsification properties have also been demonstrated to enhance hydrocarbon degradation in the environment, making them potential tools for oil spill pollution control (Banat 1995Banat IM. 1995. Biosurfactants production and possible uses in microbial enhanced oil recovery and oil pollution remediation: A Review Biores Tech 51: 1-12., Krepsky et al. 2007Krepsky N, Fontana LF, Silva FS and Crapez MAC. 2007. Alternative methodology for biossurfactant production. Braz J Biol 67: 117-124.).

The hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria are cosmopolitan, and seaweed offers a suitable place for bacterial establishment (Atlas 1995Atlas RM. 1995. Petroleum biodegradation and oil spill bioremediation. Mar Pollut Bull 31: 178-182., Armstrong et al. 2000Armstrong E, Rogerson A and Leftley JW. 2000. The abundance of heterotrophic protists associated with intertidal seaweeds. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 50: 415-424.). Seaweeds offer a large surface for the settlement of bacteria, oxygen and dissolved organic matter (Armstrong et al. 2000Armstrong E, Rogerson A and Leftley JW. 2000. The abundance of heterotrophic protists associated with intertidal seaweeds. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 50: 415-424., Sigee 2005Sigee DC. 2005. Freshwater microbiology: biodiversity and dynamic interactions of microorganisms in the aquatic environment. West Sussex: J Wiley & Sons, 537 p.). On the other hand, the bacteria consume the organic matter, releasing carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus and provide defense against pollutants, such as oil and aromatic compounds, and epiphytic organisms (Bell et al. 1974Bell W, Lang JM and Michell R. 1974. Selective stimulation of marine bacteria by algal extracellular products. Limnol Oceanogr 19: 833-839., Atlas 1995Atlas RM. 1995. Petroleum biodegradation and oil spill bioremediation. Mar Pollut Bull 31: 178-182., Sigee 2005Sigee DC. 2005. Freshwater microbiology: biodiversity and dynamic interactions of microorganisms in the aquatic environment. West Sussex: J Wiley & Sons, 537 p.).

Protists release some nitrogen and/or phosphorus-containing compounds when preying on inactive bacterial cells (Hahn and Höfle 2001Hahn MW and Höfle MG. 2001. Grazing of protozoa and it's eject on populations of aquatic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 35: 113-121., Kujawinski et al. 2002Kujawinski EB, Farrington JW and Moffett JW. 2002. Evidence for grazing-mediated production of dissolved surface-active material by marine protists. Mar Chem 77: 133-144., Matz and Jürgens 2001Matz C and Jürgens K. 2001. Effects of hydrophobic and electrostatic cell surface properties of bacteria on feeding rates of heterotrophic nanoflagellates. Appl Environ Microbiol 67: 814-820.). Protist feeding rates can be affected by characteristics of the prey particles, such as electrostatic charge (Hammer et al. 1999Hammer A, Gruttner C and Schumann R. 1999. The effect of electrostatic charge of food particles on capture efficiency by Oxyrrhis marina Dujardin (dinoflagellate). Protist 150: 375-382.), cell shape (Kolaczyk and Wiackowski 1997Kolaczyk A and Wiackowski K. 1997. Induced defense in the ciliate Euplotes octocarinatus is reduced when alternative prey are available to the predator. Acta Protozool 36: 57-61.) and exopolymer secretions (Liu and Buskey 1999Liu H and Buskey EJ. 1999. The exopolymer secretions (EPS) layer surrounding Aureoumbra lagunensis cells affects growth, grazing and behavior of protozoa. Limnol Oceanogr 45: 1187-1191.).

During the bioassays, the hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria BCr, BLo and BDm showed significant size differences in the bioassays in the presence and absence of oil. These differences manifested in the increasing size of the biofilm. The biofilms contain bacteria depositing exopolysaccharides (EPS), which exhibit amphiphilic properties allowing these macromolecules to interface with hydrophobic substrates, such as hydrocarbons. These macromolecules effectively increase the solubility of aromatic hydrocarbons and enhance their biodegradation by the microbial community (Pacwa-Płociniczak et al. 2011Pacwa-Płociniczak M, Plaza GA, Piotrowska-Seget Z and Cameotra SS. 2011. Environmental applications of biosurfactants: Recent Advances Int J Mol Sci 12: 633-654., Gutierrez et al. 2013Gutierrez T, Berry D, Yang T, Mishamandani S, Mckay L, Teske A and Aitken MD. 2013. Role of Bacterial Exopolysaccharides (EPS) in the Fate of the Oil Released during the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill. PLoS One 8(6): e67717. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0067717

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.006...

).

In the presence of oil, the production of a biofilm with surfactant activity (Krespsky et al. 2007) and an increase in cell size resulted in an increase in the biomass of the bacteria BCr, BLo, BDm and a decrease in the biomass of Scuticociliatida, Cryptomonadida (site 2), Euplotes sp. and Cryptomonadida, (site 3), suggesting a reduction in grazing and a decrease in the transfer of carbon to higher trophic levels. Site 2 had high concentrations of coprostanol due to the input of sewage from the city of São Gonçalo (Carreira et al. 2001Carreira R, Wagener ALR, Fileman T and Readman JW. 2001. Distribuição de coprostanol (5β(H)-colestan-3β-OL) em sedimentos superficiais da Baía de Guanabara: indicador da poluição recente por esgotos domésticos. Quim Nova 24: 37-42.), which selects the microorganisms capable of living in environments with high concentrations of organic matter.

In environments polluted by oil, such as site 1, hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria and their predators, such as Cryptomonadida, are selected (Crapez et al. 2001). The growth of the hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria BCr, BLo and BDm was followed by the growth of grazing Cryptomonadida. Site 1 is the nearest to the REDUC oil refinery, and sediment samples may be classified as moderately to highly contaminated (250 to 500 µg.kg–1 total PAH) (Silva et al. 2007Silva TF, Azevedo DA and Aquino Neto FR. 2007. Distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface sediments and waters from Guanabara Bay, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J Braz Chem Soc 18: 628-637.).

CONCLUSIONS

Protists were not found in a vegetative form, which is most likely linked to environmental pollution.

Oil pollution selects the hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria, and this resulted in an increase in the biomass of Cryptomonadida at site 1, suggesting a transfer of carbon to higher trophic levels.

Site 2 was polluted by sewage, which prevented Cryptomonadida survival in the presence of oil, suggesting a bottom-up effect.

Although hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria showed an increase in cell size and produced a biofilm with surfactant activity, the biomass of Scuticociliatida, Cryptomonadida (site 2), Euplotes sp. and Cryptomonadida(site 3) decreased. These sites showed no significant contribution of oil to select hydrocarbon-degrading microorganisms or oil-resistant protists.

The authors wish to thank Antônio de Paula Filho from the IQ institute (UFRJ) and Camila M. da Silva, who mediated the transfer of Light Arabian oil from PETROBRAS to UFF. This study was supported by grants from the Brazilian Petroleum Agency (ANP) and its scholarship program (PRH-11), grants from Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

REFERENCES

- Armstrong E, Rogerson A and Leftley JW. 2000. The abundance of heterotrophic protists associated with intertidal seaweeds. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 50: 415-424.

- Atlas RM. 1995. Petroleum biodegradation and oil spill bioremediation. Mar Pollut Bull 31: 178-182.

- Banat IM. 1995. Biosurfactants production and possible uses in microbial enhanced oil recovery and oil pollution remediation: A Review Biores Tech 51: 1-12.

- Bell W, Lang JM and Michell R. 1974. Selective stimulation of marine bacteria by algal extracellular products. Limnol Oceanogr 19: 833-839.

- Buck KR, Barry JP and Simpson AGB. 2000. Monterey Bay cold seep biota: Euglenozoa with chemoautotrophic bacterial epibionts. Eur J Protistol 36: 117-126.

- Carlucci AF, Craven DB, Robertson KJ and Williams PM. 1986. Surface-film microbial populations: diel amino acid metabolism, carbon utilization, and growth rates. Mar Biol 92: 289-297.

- Caron DA and Goldman JC. 1990. Protozoan nutrient regeneration. In: Capriulo GM (Ed), Ecology of Marine Protozoa, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 283-306.

- Carreira R, Wagener ALR, Fileman T and Readman JW. 2001. Distribuição de coprostanol (5β(H)-colestan-3β-OL) em sedimentos superficiais da Baía de Guanabara: indicador da poluição recente por esgotos domésticos. Quim Nova 24: 37-42.

- Carreira RS, Wagener ALR, Readman JW, Fileman TW, Macko SA and Veiga A. 2002. Change in the sedimentary organic carbon pool of a fertilized tropical estuary, Guanabara Bay, Brazil: an elemental, isotopic and molecular marker approach. Mar Chem 79: 207-227.

- Christaki U, Van Wambeke F and Dolan JR. 1999. Nanoflagellates (mixotrophs, heterotrophs, and autotrophs) in the oligotrophic eastern Mediterranean: standing stocks, bacterivory and relationships with bacterial production. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 181: 297-307.

- Crapez MAC. 2001. Efeitos de hidrocarbonetos de petróleo na biota marinha. In: MORAES R, CRAPEZ MAC, PFEIFFER W, FARINA M, BAINY A AND TEIXEIRA V (Eds), Efeitos dos Poluentes em Organismos Marinhos, São Paulo: Arte e Ciência-Vilipress, p. 255-270.

- Crapez MAC. 2002. Bactérias marinhas. In: Pereira RC and Soares-Gomes A (Eds), Biologia Marinha, Rio de Janeiro: Interciência, p. 81-101.

- Dalby AP, Kormas KAR, Christaki U and Karayanni H. 2008. Cosmopolitan heterotrophic microeukaryotes are active bacterial grazers in experimental oil-polluted systems. Environ Microbiol 10: 47-56.

- Dolan JR. 1997. Phosphorus and ammonia excretion by planktonic protists. Mar Geol 139: 109-122.

- Dragesco J and Dragesco-Kernéis A. 1986. Ciliés libres de l'Afrique intertropicale. Introduction à connaissance et à l'etude des ciliés. Faune Tropicale 26: 1-559.

- Edwards KJ, Bach W and McCollom TM. 2005. Geomicrobiology in oceanography: microbe-mineral interactions at and below the seafloor. Trends Microbiol 13: 449-455.

- Feema 1990. Projeto de recuperação gradual da Baía de Guanabara, v. 1. Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Estadual de Engenharia do Meio Ambiente, 203 p.

- Fenchel T. 1987. Ecology of Protozoa: The Biology of Free-living Phagotrophic Protists. Berlin: Springer, 197 p.

- Foissner W, Berger H, Blatterer H and Kohmann F. 1995. In: Taxonomische und ökologische revision der ciliaten des saprobiensystems - Band IV: Gymnostomates, Loxodes. Munich: Informationsberichte des Bayer Landesamtes für Wasserwirtschaft, 540 p.

- Fontana LF, Silva FS, Krepsky N, Barcelos MA and Crapez MAC. 2006. Natural attenuation of aromatic hydrocarbon from sandier sediement in Boa Viagem, Guanabra Bay, RJ, Brazil. Geochimica Brasiliensis 20: 78-86, 2006.

- Gomes EAT, Santos VSD, Tenenbaum DR and Villac MC. 2007. Protozooplankton characterization of two contrasting sites in a tropical coastal ecosystem (Guanabara Bay, RJ). Braz J Oceanogr 55: 29-38.

- Guerra LV, Savergnini F, Silva FS, Bernardes MC and Crapez MAC. 2011. Biochemical and microbiological tools for the evaluation of environmental quality of a coastal lagoon system in Southern Brazil. Braz J Biol 71: 461-468.

- Gutierrez T, Berry D, Yang T, Mishamandani S, Mckay L, Teske A and Aitken MD. 2013. Role of Bacterial Exopolysaccharides (EPS) in the Fate of the Oil Released during the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill. PLoS One 8(6): e67717. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0067717

» https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0067717 - Hahn MW and Höfle MG. 2001. Grazing of protozoa and it's eject on populations of aquatic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 35: 113-121.

- Hammer A, Gruttner C and Schumann R. 1999. The effect of electrostatic charge of food particles on capture efficiency by Oxyrrhis marina Dujardin (dinoflagellate). Protist 150: 375-382.

- Jica 1994. The study on recuperation of the Guanabara Bay ecosystem, vol 8. Japan International Cooperation Agency, Kokusai Kogyo Co., Ltd., Tokyo.

- Jumars PA, Penry DL, Baross JA, Perry MJ and Frost BW. 1989. Closing the microbial loop: dissolved carbon pathway to heterotrophic bacteria from incomplete ingestion, digestion and absorption in animals. Deep-Sea Res 36: 483-495.

- Kjerfve B, Ribeiro CA, Dias GTM, Filippo A and Quaresma VS. 1997. Oceanographic characteristics of an impacted coastal bay: Baia de Guanabara, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Cont Shelf Res 17: 1609-1643.

- Kepner RL and Pratt JR. 1994. Use of fluorochromes for direct enumeration of total bacteria in environmental samples: past and present. Microbiol Rev 58: 603-615.

- Kolaczyk A and Wiackowski K. 1997. Induced defense in the ciliate Euplotes octocarinatus is reduced when alternative prey are available to the predator. Acta Protozool 36: 57-61.

- Krepsky N, Fontana LF, Silva FS and Crapez MAC. 2007. Alternative methodology for biossurfactant production. Braz J Biol 67: 117-124.

- Kugrens P, Lee R and Hill DR. 2000. Flagellated. In: LEE JJ, LEEDALE GF AND BRADBURY P (Eds), The illustrated guide to the protozoa, 2nd ed., Lawrence: Society of Protozoologists, p. 1111-1250.

- Kujawinski EB, Farrington JW and Moffett JW. 2002. Evidence for grazing-mediated production of dissolved surface-active material by marine protists. Mar Chem 77: 133-144.

- Laybourn-Parry J, Mell EM and Roberts EC. 2000. Protozoan growth rates in Antarctic lakes. Polar Biol 23: 445-451.

- Liu H and Buskey EJ. 1999. The exopolymer secretions (EPS) layer surrounding Aureoumbra lagunensis cells affects growth, grazing and behavior of protozoa. Limnol Oceanogr 45: 1187-1191.

- Lynn DH and Small E. 2000. Ciliophora. In: LEE JJ, LEEDALE GF AND BRADBURY P (Eds), The illustrated guide to the protozoa, 2nd ed., Lawrence: Society of Protozoologists, p 371-676.

- Madigan TM, Martinko JM and Parker J. 2004. Hábitat microbianos, ciclos de nutrientes e interacciones con plantas y animales. In: Microbiología de los microorganimos, 10th ed., Madri: Prentice Hall, p. 624-687.

- Matz C and Jürgens K. 2001. Effects of hydrophobic and electrostatic cell surface properties of bacteria on feeding rates of heterotrophic nanoflagellates. Appl Environ Microbiol 67: 814-820.

- Mauclaire L, Pelza O, Thullnera M, Abrahamb W and Zeyer J. 2003. Assimilation of toluene carbon along a bacteria-protist food chain determined by 13C-enrichment of biomarker fatty acids. J Microbiol Methods 55: 635-549.

- Nagata T and Kirchman DL. 1992a. Release of dissolved organic matter by heterotrophic protozoa: implications for microbial food webs. Archiv fuer Hydrobiologie, Beiheft Ergebnisse Limnologie 35: 99-109.

- Nagata T and Kirchman DL. 1992b. Release of macromolecular organic complexes by heterotrophic marine flagellates. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 83: 233-240.

- Pacwa-Płociniczak M, Plaza GA, Piotrowska-Seget Z and Cameotra SS. 2011. Environmental applications of biosurfactants: Recent Advances Int J Mol Sci 12: 633-654.

- Paiva TS and Silva-Neto ID. 2004. Ciliate protists from Cabiúnas lagoon (Restinga de Jurubatiba, Macaé, Rio de Janeiro) with emphasis on water quality indicator species and description of Oxytrichamarcili sp. Braz J Biol 64: 465-478.

- Pedros-Alio C, Calderon-Paz I, Maclean MH, Medina G, Marrase C, Gasol JM and Guixa-Boixereu N. 2000. The microbial food web along salinity gradients. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 32: 143-155.

- Rahman KSM, Rahman TJ, Kourkoutas Y, Petsas I, Marchant R and Banat IM. 2003. Enhanced bioremediation of n-alkane in petroleum sludge using bacterial consortium amended with rhamnolipid and micronutrients. Bioresour Technol 90: 159-168.

- Ron EZ and Rosenberg E. 2002. Biosurfactants and oil bioremediation. Curr Opin Biotechnol 13: 249-252.

- Scott FJ, Davidson AT and Marchant HJ. 2001. Grazing by the Antarctic sea ice ciliate Pseudocohnilembus. Polar Biol 24:127-131.

- Sherr EB and Sherr BF. 1994. Bacterivory and herbivory: key roles of phagotrophic protists in pelagic food webs. Microb Ecol 28: 223-235.

- Sigee DC. 2005. Freshwater microbiology: biodiversity and dynamic interactions of microorganisms in the aquatic environment. West Sussex: J Wiley & Sons, 537 p.

- Sikkema J, Bont JA and Poolman B. 1995. Mechanisms of membrane toxicity of hydrocarbons. Microbiol Rev 59: 201-222.

- Silva FS, Krepsky N, Teixeira VL and Crapez MAC. 2005. Estímulo da produção de biossurfactante por extrato da alga vermelha Digenea simplex (WULFEN) C. AGARDH em comunidades bacterianas da praia de Boa Viagem (RJ). In: Série Livros 10 do Museu Nacional do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro: Museu Nacional do Rio de Janeiro, p. 469-483.

- Silva FS, Santos ES, Laut LLM, Sanchez-Nuñes ML, Fonseca EM, Baptista-Neto JA, Mendonça-Filho JG and Crapez MAC. 2010. Geomicrobiology and Biochemical Composition of Two Sediment Cores from Jurujuba Sound - Guanabara Bay – SE Brazil. Anu Inst Geocienc 33:73-84.

- Silva-Neto ID. 2000. Improvement of silver impregnation technique (Protargol) to obtain morphological features of protists ciliates, flagellates and opalinates. Rev Bras Biol 60: 451-459.

- Silva TF, Azevedo DA and Aquino Neto FR. 2007. Distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface sediments and waters from Guanabara Bay, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J Braz Chem Soc 18: 628-637.

- Slàdeček V. 1973. System of water quality from the biological point of view. Arch Hydrobiol Beih Ergebn Limno 7: 1-218.

- Wilkinson S, Nicklin S and Faull JL. 2002. Biodegradation of fuel oils and lubricants: Soil and water bioremediation options. In: Singh VP and Stapleton RD (Eds), Progress in Industrial Microbiology 36: 69-100.

- Zarda B, Mattison G, Hess A, Hahn D, Höhener P and zeyer J. 1998. Analysis of bacterial and protozoan communities in an aquifer contaminated with monoaromatic hydrocarbons. FEMS Micro Ecol 27: 141-152.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

June 2014

History

-

Received

20 June 2012 -

Accepted

2 Sept 2013