ABSTRACT

New data concerning the management of autoimmune liver diseases have emerged since the last single-topic meeting sponsored by the Brazilian Society of Hepatology to draw recommendations about the diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), overlap syndromes of AIH, PBC and PSC and specific complications and topics concerning AIH and cholestatic liver diseases. This manuscript updates those previous recommendations according to the best evidence available in the literature up to now. The same panel of experts that took part in the first consensus document reviewed all recommendations, which were subsequently scrutinized by all members of the Brazilian Society of Hepatology using a web-based approach. The new recommendations are presented herein.

HEADINGS:

Autoimmune hepatitis, diagnosis; Autoimmune hepatitis, therapy; Sclerosing cholangitis, diagnosis; Sclerosing cholangitis, therapy; Biliary liver cirrhosis, diagnosis; Biliary liver cirrhosis, therapy; Medical societies

RESUMO

Desde a publicação em 2015 das recomendações da Sociedade Brasileira de Hepatologia sobre a prevenção e tratamento de doenças hepáticas autoimunes, novos dados baseados em evidências científicas foram publicados na literatura, mudando o diagnóstico e tratamento da hepatite autoimune (HAI), colangite biliar primária (CBP), colangite esclerosante primária (CEP), síndromes de sobreposição de HAI, CBP e CEP e o manejo de complicações específicas além de outros tópicos relativos à HAI e doenças hepáticas colestáticas. Este manuscrito atualiza as recomendações anteriores de acordo com as melhores evidências disponíveis na literatura até o momento. O mesmo painel de experts que participou da primeira diretriz revisou todas as recomendações de acordo com os dados publicados na literatura e elaborou um manuscrito submetido subsequentemente à apreciação e revisão de todos os membros da Sociedade Brasileira de Hepatologia via homepage da sociedade. As recomendações finais atualizadas foram condensadas no presente documento.

DESCRITORES:

Hepatite autoimune, diagnóstico; Hepatite autoimune, terapia; Colangite esclerosante, diagnóstico; Colangite esclerosante, terapia; Cirrose hepática biliar, diagnosis; Cirrose hepática biliar, terapia; Sociedades médicas

INTRODUCTION

The Brazilian Society of Hepatology published evidence-based recommendations for the management of autoimmune liver diseases (ALD) in December 2015 issue of Archives of Gastroenterology following a consensus meeting held in São Paulo, Brazil, on October 18th, 201411. Bittencourt PL, Cançado EL, Couto CA, Levy C, Porta G, Silva AE, et al. Brazilian society of hepatology recommendations for the diagnosis and management of autoimmune diseases of the liver. Arq Gastroenterol. 2015;52 (Suppl 1):15-46.. The first version covered diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) and their overlap syndromes, the management of specific complications of cholestasis, such as pruritus, fatigue and hypercholesterolemia, and special controversial topics including management of recurrent cholangitis, prevention and management of biliary tract tumors in PSC and liver transplantation (LT) for AIH, PSC and PBC. Since then, a large amount of data concerning the diagnosis and treatment of ALD have emerged in the medical literature and even primary biliary cirrhosis have been properly renamed as primary biliary cholangitis22. Beuers U, Gershwin ME, Gish RG, Invernizzi P, Jones DEJ, Lindor K, et al. Changing nomenclature for PBC: from ‘cirrhosis’ to ‘cholangitis’. J Hepatol. 2015;63:1285-7.. Therefore, the Brazilian Society of Hepatology sponsored another meeting in December 2018 to update the aforementioned recommendations. An organizing committee of five experts, the same who took part in the 1rst consensus meeting, submitted to the previous panel all topics to be reviewed according to the best-evidence available in literature using MEDLINE. All updated recommendations were discussed by the organizing committee and were further scrutinized by all members of the Brazilian Society of Hepatology using a web-based approach. Most of those updated recommendations were based on new data published since 201533. Methodology Manual for ACC/AHA Guideline Writing Committees: Methodologies and Policies from the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines. April; 2006. 2006.

4. Gronbaek L, Vilstrup H, Pedersen L, Christensen K, Jepsen P. Family occurrence of autoimmune hepatitis: A Danish nationwide registry-based cohort study. J Hepatol. 2018;69:873-7.

5. Wong GW, Yeong T, Lawrence D, Yeoman AD, Verma S, Heneghan MA. Concurrent extrahepatic autoimmunity in autoimmune hepatitis: implications for diagnosis, clinical course and long-term outcomes. Liver Int. 2017;37:449-57.

6. Cancado ELR, Abrantes-Lemos CP, Terrabuio DRB. The importance of autoantibody detection in autoimmune hepatitis. Front Immunol. 2015;6:222.

7. Vergani D, Alvarez F, Bianchi FB, Cançado EL, MacKay IR, Manns MP, et al. Liver autoimmune serology: a consensus statement from the committee for autoimmune serology of the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. J Hepatol. 2004;41:677-83.

8. Zachou K, Gampeta S, Gatselis NK, Oikonomou K, Goulis J, Manoussakis MN, et al. Anti-SLA/LP alone or in combination with anti-Ro52 and fine specificity of anti-Ro52 antibodies in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Liver Int . 2015;35:660-72.

9. Liaskos C, Bogdanos DP, Rigopoulou EI. Antibody responses specific for soluble liver antigen co-occur with R0-52 antibodies in patients with autoimmune hepatitis (abstract). J Hepatol. 2007;46 (Suppl 1):S250.

10. Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D, Baumann U, Czubkowski P, Debray D, Dezsofi A, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Pediatric Autoimmune Liver Disease: ESPGHAN Hepatology Committee Position Statement. Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66:345-60.

11. Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, Parés A, Dalekos GN, Krawitt EL, et al. Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:169-76.

12. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Autoimmune Hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2015;63:971-1004.

13. Kanzler S, Gerken G, Löhr H, Galle PR, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH, Lohse AW. Duration of immunosuppressive therapy in autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2001;34:354-5.

14. Couto CA, Bittencourt PL, Porta G, Abrantes-Lemos CP, Carrilho FJ, Guardia BD, et al. Antismooth muscle and antiactin antibodies are indirect markers of histological and biochemical activity of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2014;59:592-600.

15. Terrabuio DRB, Diniz MA, Falcão LTM, Guedes ALV, Nakano LA, Evangelista AS, et al. Chloroquine Is Effective for Maintenance of Remission in Autoimmune Hepatitis: Controlled, Double-Blind, Randomized Trial. Hepatol Commun. 2018;3:116-28.

16. Tomasulo P. LactMed-new NLM database on drugs and lactation. Med Ref Serv Q. 2007;26:51-8.

17. Ponticelli C, Moroni G. Fetal toxicity of immunosuppressive Drugs in Pregnancy. J Clin Med 2018;7. Pii: E552.

18. Dave M, Elmunzer BJ, Dwamena BA, Higgins PD. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: meta-analysis of diagnostic performance of MR cholangiopancreatography. Radiology 2010;256:387-96.

19. Aabakken L, Karlsen TH, Albert J, Arvanitakis M, Chazouilleres O, Dumonceau JM, et al. Role of endoscopy in primary sclerosing cholangitis: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) and European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2017;49:588-608.

20. Razumilava N, Gores GJ, Lindor KD. Cancer surveillance in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2011;54:1842-52.

21. Weismüller TJ, Trivedi PJ, Bergquist A, Imam M, Lenzen H, Ponsioen CY; International PSC Study Group. Patient Age, Sex, and Inflammatory Bowel Disease Phenotype Associate With Course of Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1975-84.

22. Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis, Part 2: cancer risk, prevention and surveillance. Tabibian JH, Ali AH, Lindor KD. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;14:427-32.

23. Karlsen TH, Folseraas T, Thorburn D, Vesterhus M. Primary sclerosing cholangitis - a comprehensive review. J Hepatol. 2017;67:1298-323.

24. Brand M, Bizos D, O’Farrell P Jr. Antibiotic prophylaxis for patients undergoing elective endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010.

25. Hirschfield GM, Beuers U, Corpechot C, Invernizzi P, Jones D, Marzioni M, et al. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: The diagnosis and management of patients with primary biliary cholangitis. European Association for the Study of the Liver. J Hepatol. 2017;67:145-50.

26. Lindor KD, Bowlus CL, Boyer J, Levy C, Mayo M. Primary Biliary Cholangitis: 2018 Practice Guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2019;69:394-419.

27. Corpechot C, Carrat F, Poujol-Robert A, Gaouar F, Wendum D, Chazouilleres O, et al. Noninvasive elastography-based assessment of liver fibrosis progression and prognosis in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2012;56:198-208.

28. Corpechot C, El Naggar A, Poujol-Robert A, Ziol M, Wendum D, Chazouilleres O, et al. Assessment of biliary fibrosis by transient elastography in patients with PBC and PSC. Hepatology. 2006;43:1118-24.

29. Corpechot C. Utility of Noninvasive Markers of Fibrosis in Cholestatic Liver Diseases. Clin Liver Dis. 2016;20:143-58.

30. Lammers WJ, Hirschfield GM, Corpechot C, Nevens F, Lindor KD, Janssen HL, et al; Global PBC Study Group. Development and Validation of a Scoring System to Predict Outcomes of Patients With Primary Biliary Cirrhosis Receiving Ursodeoxycholic Acid Therapy. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1804-12.

31. Carbone M, Sharp SJ, Flack S, Paximadas D, Spiess K, Adgey C, et al. The UK-PBC Risk Scores: Derivation and validation of a scoring system for long-term prediction of end-stage liver disease in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2016;63:930-50.

32. Corpechot C, Chazouilleres O, Poupon R. Early primary biliary cirrhosis: biochemical response to treatment and prediction of long-term outcome. J Hepatol. 2011;55:1361-67.

33. Corpechot C, Chazouillères O, Rousseau A, Guyader D, Habersetzer F, Mathurin P, et al. A 2-year multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of bezafibrate for the treatment of primary biliary cholangitis in patients with inadequate biochemical response to ursodeoxycholic acid therapy (Bezurso). J Hepatol. 2017;66:S89.

34. Corpechot C, Chazouillères O, Rousseau A, Le Gruyer A, Habersetzer F, Mathurin P, et al. A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Bezafibrate in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2171-81.

35. Buckley L, Guyatt G, Fink HA, Cannon M, Grossman J, Hansen KE, et al. American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Prevention and Treatment of Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:1521-37.

36. Guanabens N, Monegal A, Cerda D, Muxi A, Gifre L, Peris P, et al. Randomized trial comparing monthly ibandronate and weekly alendronate for osteoporosis in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2013;58:2070-8.

37. Czaja AJ. Acute and acute severe (fulminant) autoimmune hepatItis. Dig Dis Sci 2013;5:897-914.

38. Yeoman AD, Westbrook RH, Zen Y, Bernal W, Al-Chalabi T, Wendon JA, et al. Prognosis of acute severe autoimmune hepatitis (AS-AIH): The role of corticosteroids in modifying outcome. J Hepatol, 2014;61:876-82.

39. Weiler-Normann C, Lohse AW. Acute autoimmune hepatitis: Many open questions. Editorial. J Hepatol. 2014;61:727-29.

40. Theocharidou E, Heneghan MA. Con: Steroids Should Not Be Withdrawn in Transplant Recipients With Autoimmune Hepatitis. Liver Transpl. 2018;24:1113-8.

41. Hirschfield GM, Dyson JK, Alexander GJM, Chapman MH, Collier J, Hübscher S, et al. The British Society of Gastroenterology /UK-PBC primary biliary cholangitis treatment and management guidelines. Gut. 2018;67:1568-94.

42. Montano-Loza AJ, Hansen BE, Corpechot C, Roccarina D, Thorburn D, Trivedi P, et al.; Global PBC Study Group. Factors Associated With Recurrence of Primary Biliary Cholangitis After Liver Transpl antation and Effects on Graft and Patient Survival. Gastroenterology . 2019;156:96-107.

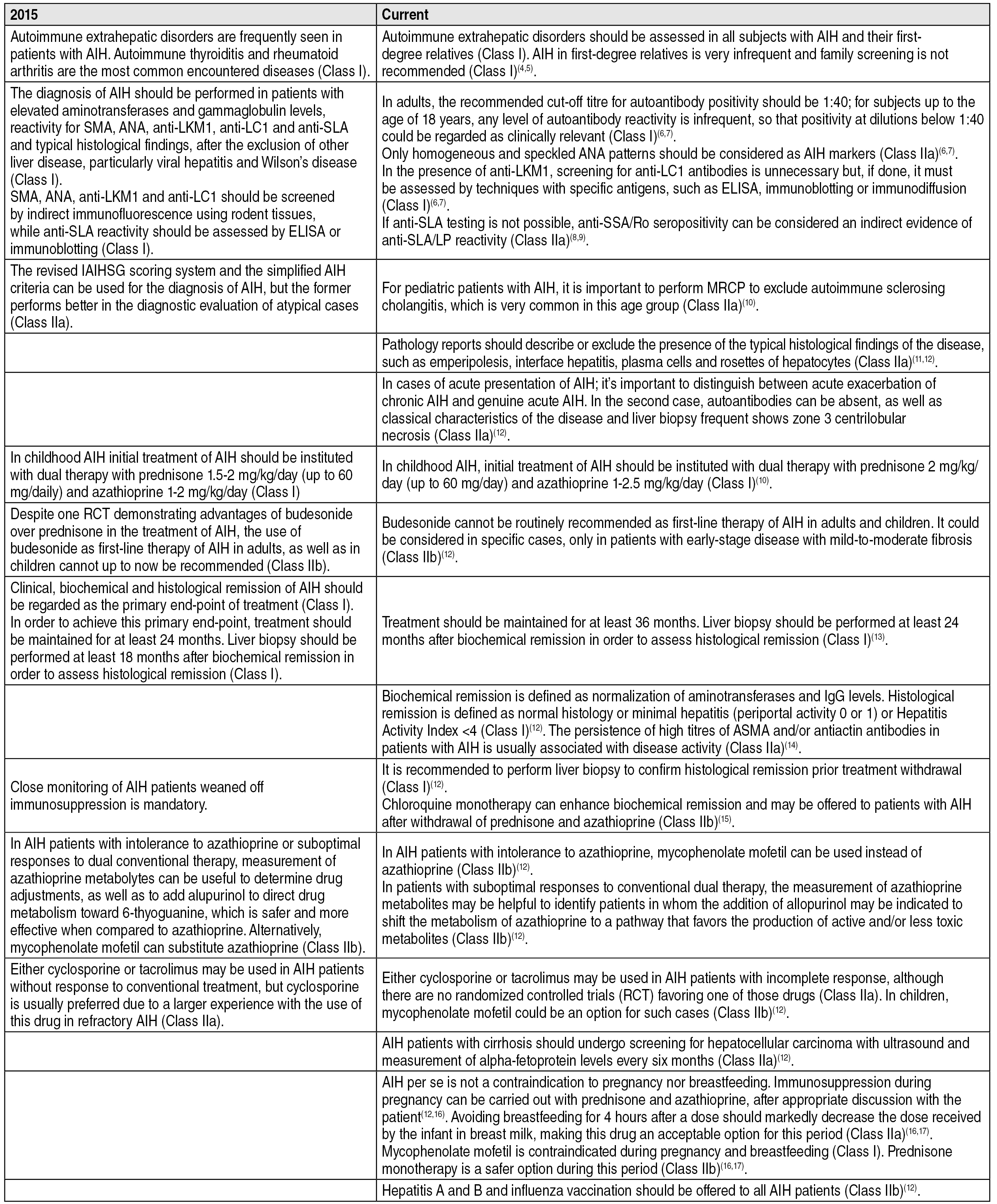

43. Martin EF, Levy C. Timing, management, and outcomes of liver transplantation in Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. Semin Liv Dis. 2017;37:305-13.-4444. Chandok N, Watt KD. Burden of De Novo Malignancy in the Liver Transpl ant Recipient. Liver Transplantation. 2012;18:1277-89., which are briefly summarized in FIGURES 1,2,3,4,5,6,7. The present manuscript is the final version of the document followed by the recommendations, which were graded according to the grading system adopted by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, as outlined below33. Methodology Manual for ACC/AHA Guideline Writing Committees: Methodologies and Policies from the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines. April; 2006. 2006.:

Comparison of past and current recommendations for management of autoimmune hepatitis. 44. Gronbaek L, Vilstrup H, Pedersen L, Christensen K, Jepsen P. Family occurrence of autoimmune hepatitis: A Danish nationwide registry-based cohort study. J Hepatol. 2018;69:873-7.

5. Wong GW, Yeong T, Lawrence D, Yeoman AD, Verma S, Heneghan MA. Concurrent extrahepatic autoimmunity in autoimmune hepatitis: implications for diagnosis, clinical course and long-term outcomes. Liver Int. 2017;37:449-57.

6. Cancado ELR, Abrantes-Lemos CP, Terrabuio DRB. The importance of autoantibody detection in autoimmune hepatitis. Front Immunol. 2015;6:222.

7. Vergani D, Alvarez F, Bianchi FB, Cançado EL, MacKay IR, Manns MP, et al. Liver autoimmune serology: a consensus statement from the committee for autoimmune serology of the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. J Hepatol. 2004;41:677-83.

8. Zachou K, Gampeta S, Gatselis NK, Oikonomou K, Goulis J, Manoussakis MN, et al. Anti-SLA/LP alone or in combination with anti-Ro52 and fine specificity of anti-Ro52 antibodies in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Liver Int . 2015;35:660-72.

9. Liaskos C, Bogdanos DP, Rigopoulou EI. Antibody responses specific for soluble liver antigen co-occur with R0-52 antibodies in patients with autoimmune hepatitis (abstract). J Hepatol. 2007;46 (Suppl 1):S250.

10. Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D, Baumann U, Czubkowski P, Debray D, Dezsofi A, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Pediatric Autoimmune Liver Disease: ESPGHAN Hepatology Committee Position Statement. Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66:345-60.

11. Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, Parés A, Dalekos GN, Krawitt EL, et al. Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:169-76.

12. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Autoimmune Hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2015;63:971-1004.

13. Kanzler S, Gerken G, Löhr H, Galle PR, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH, Lohse AW. Duration of immunosuppressive therapy in autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2001;34:354-5.

14. Couto CA, Bittencourt PL, Porta G, Abrantes-Lemos CP, Carrilho FJ, Guardia BD, et al. Antismooth muscle and antiactin antibodies are indirect markers of histological and biochemical activity of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2014;59:592-600.

15. Terrabuio DRB, Diniz MA, Falcão LTM, Guedes ALV, Nakano LA, Evangelista AS, et al. Chloroquine Is Effective for Maintenance of Remission in Autoimmune Hepatitis: Controlled, Double-Blind, Randomized Trial. Hepatol Commun. 2018;3:116-28.

16. Tomasulo P. LactMed-new NLM database on drugs and lactation. Med Ref Serv Q. 2007;26:51-8.-1717. Ponticelli C, Moroni G. Fetal toxicity of immunosuppressive Drugs in Pregnancy. J Clin Med 2018;7. Pii: E552.

Comparison of past and current recommendations for management of primary sclerosing cholangitis. 1818. Dave M, Elmunzer BJ, Dwamena BA, Higgins PD. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: meta-analysis of diagnostic performance of MR cholangiopancreatography. Radiology 2010;256:387-96.

19. Aabakken L, Karlsen TH, Albert J, Arvanitakis M, Chazouilleres O, Dumonceau JM, et al. Role of endoscopy in primary sclerosing cholangitis: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) and European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2017;49:588-608.

20. Razumilava N, Gores GJ, Lindor KD. Cancer surveillance in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2011;54:1842-52.

21. Weismüller TJ, Trivedi PJ, Bergquist A, Imam M, Lenzen H, Ponsioen CY; International PSC Study Group. Patient Age, Sex, and Inflammatory Bowel Disease Phenotype Associate With Course of Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1975-84.

22. Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis, Part 2: cancer risk, prevention and surveillance. Tabibian JH, Ali AH, Lindor KD. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;14:427-32.-2323. Karlsen TH, Folseraas T, Thorburn D, Vesterhus M. Primary sclerosing cholangitis - a comprehensive review. J Hepatol. 2017;67:1298-323.

Comparison of past and current recommendations for endoscopic treatment of primary sclerosing cholangitis. 1919. Aabakken L, Karlsen TH, Albert J, Arvanitakis M, Chazouilleres O, Dumonceau JM, et al. Role of endoscopy in primary sclerosing cholangitis: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) and European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2017;49:588-608.

20. Razumilava N, Gores GJ, Lindor KD. Cancer surveillance in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2011;54:1842-52.

21. Weismüller TJ, Trivedi PJ, Bergquist A, Imam M, Lenzen H, Ponsioen CY; International PSC Study Group. Patient Age, Sex, and Inflammatory Bowel Disease Phenotype Associate With Course of Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1975-84.

22. Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis, Part 2: cancer risk, prevention and surveillance. Tabibian JH, Ali AH, Lindor KD. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;14:427-32.

23. Karlsen TH, Folseraas T, Thorburn D, Vesterhus M. Primary sclerosing cholangitis - a comprehensive review. J Hepatol. 2017;67:1298-323.-2424. Brand M, Bizos D, O’Farrell P Jr. Antibiotic prophylaxis for patients undergoing elective endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010.

Comparison of past and current recommendations for management of primary biliary cholangitis. 2525. Hirschfield GM, Beuers U, Corpechot C, Invernizzi P, Jones D, Marzioni M, et al. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: The diagnosis and management of patients with primary biliary cholangitis. European Association for the Study of the Liver. J Hepatol. 2017;67:145-50.

26. Lindor KD, Bowlus CL, Boyer J, Levy C, Mayo M. Primary Biliary Cholangitis: 2018 Practice Guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2019;69:394-419.

27. Corpechot C, Carrat F, Poujol-Robert A, Gaouar F, Wendum D, Chazouilleres O, et al. Noninvasive elastography-based assessment of liver fibrosis progression and prognosis in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2012;56:198-208.

28. Corpechot C, El Naggar A, Poujol-Robert A, Ziol M, Wendum D, Chazouilleres O, et al. Assessment of biliary fibrosis by transient elastography in patients with PBC and PSC. Hepatology. 2006;43:1118-24.

29. Corpechot C. Utility of Noninvasive Markers of Fibrosis in Cholestatic Liver Diseases. Clin Liver Dis. 2016;20:143-58.

30. Lammers WJ, Hirschfield GM, Corpechot C, Nevens F, Lindor KD, Janssen HL, et al; Global PBC Study Group. Development and Validation of a Scoring System to Predict Outcomes of Patients With Primary Biliary Cirrhosis Receiving Ursodeoxycholic Acid Therapy. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1804-12.

31. Carbone M, Sharp SJ, Flack S, Paximadas D, Spiess K, Adgey C, et al. The UK-PBC Risk Scores: Derivation and validation of a scoring system for long-term prediction of end-stage liver disease in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2016;63:930-50.

32. Corpechot C, Chazouilleres O, Poupon R. Early primary biliary cirrhosis: biochemical response to treatment and prediction of long-term outcome. J Hepatol. 2011;55:1361-67.

33. Corpechot C, Chazouillères O, Rousseau A, Guyader D, Habersetzer F, Mathurin P, et al. A 2-year multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of bezafibrate for the treatment of primary biliary cholangitis in patients with inadequate biochemical response to ursodeoxycholic acid therapy (Bezurso). J Hepatol. 2017;66:S89.-3434. Corpechot C, Chazouillères O, Rousseau A, Le Gruyer A, Habersetzer F, Mathurin P, et al. A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Bezafibrate in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2171-81.

Comparison of the 2015 and current strategies for the management of complications of cholestasis: osteoporosis and osteopenia. 3535. Buckley L, Guyatt G, Fink HA, Cannon M, Grossman J, Hansen KE, et al. American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Prevention and Treatment of Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:1521-37.-3636. Guanabens N, Monegal A, Cerda D, Muxi A, Gifre L, Peris P, et al. Randomized trial comparing monthly ibandronate and weekly alendronate for osteoporosis in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2013;58:2070-8.

Comparison of the 2015 and current strategies for the screening of liver and biliary tract cancer in primary sclerosing cholangitis. 2020. Razumilava N, Gores GJ, Lindor KD. Cancer surveillance in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2011;54:1842-52.,2222. Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis, Part 2: cancer risk, prevention and surveillance. Tabibian JH, Ali AH, Lindor KD. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;14:427-32.

Comparison of the 2015 and current strategies for the management of liver transplantation (LT) for autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. 1212. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Autoimmune Hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2015;63:971-1004.,2525. Hirschfield GM, Beuers U, Corpechot C, Invernizzi P, Jones D, Marzioni M, et al. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: The diagnosis and management of patients with primary biliary cholangitis. European Association for the Study of the Liver. J Hepatol. 2017;67:145-50.,3737. Czaja AJ. Acute and acute severe (fulminant) autoimmune hepatItis. Dig Dis Sci 2013;5:897-914.

38. Yeoman AD, Westbrook RH, Zen Y, Bernal W, Al-Chalabi T, Wendon JA, et al. Prognosis of acute severe autoimmune hepatitis (AS-AIH): The role of corticosteroids in modifying outcome. J Hepatol, 2014;61:876-82.-3939. Weiler-Normann C, Lohse AW. Acute autoimmune hepatitis: Many open questions. Editorial. J Hepatol. 2014;61:727-29.,4040. Theocharidou E, Heneghan MA. Con: Steroids Should Not Be Withdrawn in Transplant Recipients With Autoimmune Hepatitis. Liver Transpl. 2018;24:1113-8.,4141. Hirschfield GM, Dyson JK, Alexander GJM, Chapman MH, Collier J, Hübscher S, et al. The British Society of Gastroenterology /UK-PBC primary biliary cholangitis treatment and management guidelines. Gut. 2018;67:1568-94.,4242. Montano-Loza AJ, Hansen BE, Corpechot C, Roccarina D, Thorburn D, Trivedi P, et al.; Global PBC Study Group. Factors Associated With Recurrence of Primary Biliary Cholangitis After Liver Transpl antation and Effects on Graft and Patient Survival. Gastroenterology . 2019;156:96-107.,4343. Martin EF, Levy C. Timing, management, and outcomes of liver transplantation in Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. Semin Liv Dis. 2017;37:305-13.,4444. Chandok N, Watt KD. Burden of De Novo Malignancy in the Liver Transpl ant Recipient. Liver Transplantation. 2012;18:1277-89.

-

Class I: conditions for which there is evidence and/or general agreement that a given diagnostic evaluation, procedure or treatment is beneficial, useful, and effective.

-

Class II: conditions for which there is conflicting evidence and/or a divergence of opinion about the usefulness/efficacy of a diagnostic evaluation, procedure or treatment.

-

Class IIa: weight of evidence/opinion is in favor of usefulness/efficacy.

-

Class IIb: usefulness/efficacy is less well established by evidence/opinion.

-

Class III: conditions for which there is evidence and/or general agreement that a diagnostic evaluation, procedure/treatment is not useful/effective and, in some cases, may be harmful.

UPDATE OF RECOMMENDATIONS

I. AUTOIMMUNE HEPATITIS

Ia. AIH: Clinical manifestations

-

AIH primarily affects women of all ages and races, but mostly between 5 and 25 years of age, in a 4:1 ratio. In the majority of cases, patients with AIH have unrecognized chronic liver disease with acute hepatitis-like symptoms, but signs and symptoms of advanced chronic liver disease may also be present. Less frequently, patients do not show any symptoms, or develop fulminant hepatic failure (FHF). Consequently, its diagnosis should be considered in any patient with liver disease, at any age (Class IIa).

-

Autoimmune extrahepatic disorders, particularly autoimmune thyroiditis and rheumatoid arthritis, are frequently detected in patients with AIH and should be assessed in all subjects with this diagnosis (Class I).

-

AIH in first-degree relatives of patients with the disease is very infrequent, thus, family screening is not recommended (Class I).

Ib. AIH: Diagnosis

-

The diagnosis of AIH should be performed in patients with elevated aminotransferases and gammaglobulin levels, reactivity for anti-smooth muscle (SMA), antinuclear (ANA), anti-liver kidney microsome type 1 (anti-LKM1), anti-liver cytosol type 1 (anti-LC1) and anti-soluble liver antigen (anti-SLA) antibodies, and typical histological findings, after the exclusion of other liver diseases, particularly viral hepatitis and Wilson’s disease (Class I).

-

SMA, ANA, anti-LKM1 and anti-LC1 should be detected by indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) using rodent tissues, while anti-SLA reactivity should be assessed by ELISA or immunoblotting (Class I).

-

In adults, the recommended cut-off titre for autoantibody positivity should be 1:40, since low titres can also be found in healthy subjects and patients with other liver diseases. In children, the recommended cut-off titre for autoantibody positivity should be 1:20 for ANA and SMA or 1:10 for anti-LKM1 (Class I).

-

Only homogeneous and speckled ANA patterns should be considered as AIH markers (Class IIa).

-

In cases of positive results for anti-LKM1, testing for anti-LC1 antibodies is unnecessary but, if done, it must be assessed by techniques with specific antigens, such as ELISA, immunoblotting or immunodiffusion (Class I).

-

If anti-SLA testing is not possible, anti-SSA/Ro seropositivity can be considered an indirect evidence of anti-SLA/LP reactivity, since more than 70% of patients have concomitant reactivity (Class IIa).

-

The revised International AIH Group (IAIHG) scoring system and the simplified AIH criteria can be used for the diagnosis of AIH, but the former works better for diagnostic evaluation of atypical cases (Class IIa). For pediatric patients with AIH, it is important to do a magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) to exclude autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis, which is very common in this age group (Class IIa).

-

Liver biopsy, whenever possible, should be considered in patients with AIH for histological diagnosis and prognostic assessment. It may not be entirely necessary in patients with classical full-blown disease; however, it should be performed in all atypical cases, such as AIH in men, absence of classical serological markers or hypergammaglobulinemia and reactivity to antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA) (Class IIb). Pathology reports should describe or exclude the presence of the typical histological findings of the disease, such as emperipolesis, interface hepatitis, plasma cells and rosettes of hepatocytes.

-

It is important to distinguish between acute exacerbation of chronic AIH and genuine acute AIH without chronic histological changes. In the latter, autoantibodies as well as classical characteristics of the disease can be absent, and liver biopsy frequently show zone III centrilobular necrosis (Class IIa).

Ic. AIH: Management and treatment of adulthood and pediatric AIH

-

Initial treatment of AIH in adults should start with dual therapy with azathioprine and prednisone in doses of 30 mg/day and 50 mg/day respectively, in the absence of known contraindications for the use of those drugs (Class I). In childhood AIH, dual therapy with prednisone 2 mg/kg/day (up to 60 mg/day) and azathioprine 1-2.5 mg/kg/day is also recommended (Class I).

-

Despite the lack of data to guide drug adjustments during immunosuppressive therapy of AIH, it is suggested to taper the dose of prednisone at monthly intervals and to progressively increase the dose of azathioprine to achieve biochemical remission with as minimal side effects as possible of both drugs (Class I).

-

The range of maintenance dose of prednisone and azathioprine are respectively, 7.5-15 mg/day and 75-150 mg/day, not exceeding doses of azathioprine above 2 mg/kg/day. Maintenance doses of those immunosuppressive drugs in children are usually 2.5-5 mg/day for prednisone and up to 2 mg/kg/day for azathioprine (Class IIb).

-

It is suggested to begin prednisone monotherapy in AIH patients with contraindications to azathioprine therapy. Treatment in adults should begin with prednisone 60 mg/day with subsequent tapering to 40 mg/day and then 30 mg/day every two weeks. The corticosteroid dose should be decreased more gradually afterwards to maintenance levels not higher than 20 mg/day. In children, doses of corticosteroids should be tapered to achieve biochemical remission with minimal side effects (Class IIb).

-

Despite one randomized controlled trial RCT demonstrated the benefits of budesonide in the treatment of AIH, the use of this drug as first-line therapy for AIH in adults, as well as in children, is not routinely recommended. It is considered in specific cases, such as corticosteroids intolerance or severe side effects, only in patients with early-stage disease with mild-to-moderate fibrosis (Class IIb).

-

Clinical, biochemical and histological remission of AIH should be regarded as the primary end-point of treatment (Class I). To achieve this primary end-point, treatment should be maintained for at least 36 months. Liver biopsy should be performed at least 24 months after biochemical remission to assess histological remission (Class I).

-

Biochemical remission is defined as normalization of aminotransferases and IgG levels. Histological remission is defined as normal histology or minimal hepatitis (periportal activity 0 or 1) or Hepatitis Activity Index <4 (Class I). The persistence of high titres of SMA and/or antiactin antibodies in patients with AIH is usually associated with disease activity (Class IIa).

-

In patients with clinical, biochemical and histological remission, treatment withdrawal may be tried, after discussion of the benefits and risks with the patient. Close monitoring of aminotransferases and liver function is recommended, especially in the first 12 months after treatment withdrawal (Class I).

-

It is recommended to perform liver biopsy to confirm histological remission prior treatment withdrawal (Class I).

-

Azathioprine monotherapy in doses up to 2 mg/kg/day may be used as permanent maintenance therapy in those subjects not willing to stop treatment (Class IIa).

-

Chloroquine monotherapy can enhance biochemical remission and may be offered to patients with AIH after withdrawal of prednisone and azathioprine (Class IIb).

-

In AIH patients with intolerance to azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) can be used instead (Class IIb).

-

In patients with suboptimal responses to conventional dual therapy, the assessment of azathioprine metabolites may be helpful to increase treatment response, avoid drug toxicity and monitor treatment adherence. In the presence of low 6-thioguanine levels and/or high levels of 6-methylmercaptopurine, the addition of allopurinol may be permitted in sites with local expertise and resources, to shift the metabolism of the azathioprine to a pathway that favors the production of active and/or less toxic metabolites (Class IIb).

-

In patients with incomplete response, promising alternative drugs include calcineurin inhibitors (Class IIa). Either cyclosporin or tacrolimus may be used in AIH patients due to the absence of RCTs favoring one of those drugs (Class IIa). In children, MMF can be an option for such cases (Class IIb).

-

AIH patients with cirrhosis should undergo testing for hepatocellular carcinoma with ultrasound and measurement of alphafetoprotein levels every six months (Class IIa).

-

AIH per se is not a contraindication to pregnancy nor to breastfeeding. Immunosuppression during pregnancy can be carried out with prednisone and azathioprine, after appropriate discussion with the patient, due to the low risk of fetal teratogenicity seen with azathioprine. Avoiding breastfeeding for 4 hours after a dose should markedly decrease the dose received by the infant through breast milk, making this drug an acceptable option for this period (Class IIa). MMF is contraindicated during pregnancy and breastfeeding due to increased risk of fetal malformations (Class I). Prednisone monotherapy is a safer option during pregnancy and breastfeeding (Class IIb).

-

Hepatitis A and B and influenza vaccination should be offered to all AIH patients (Class IIb).

II. PRIMARY SCLEROSING CHOLANGITIS

IIa. PSC - Diagnosis

-

Patients with cholestasis of unknown cause, particularly in the absence of AMA should undergo MRCP to rule out PSC (Class I).

-

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) can be considered if MRCP is non-diagnostic or contraindicated, in patients with persistent clinical suspicion of PSC. The risks of ERC have to be weighed against the potential benefit with regard to surveillance and treatment recommendations (Class IIa).

-

Liver biopsy should be considered in those subjects with normal MRCP under suspicion of small-duct PSC. Histology is not required for diagnosis of patients with large-duct PSC by MRCP. However, it may be needed to assess the presence of PSC with features of AIH, in those subjects with disproportionally higher aminotransferases levels more than five times the upper limit of normal (Class Ib).

-

Colonoscopy is recommended for patients with PSC at diagnosis and every 3-5 years, irrespective of the presence of symptoms. Multiple biopsies are recommended even if the endoscopic appearance of the colonic mucosa is normal (Class Ia).

-

Patients with the diagnosis of concurrent IBD should be submitted to annual colonoscopic testing for colorectal neoplasia. In sites with appropriate expertise and resources, it is recommended to consider chromoendoscopy to improve surveillance (Class Ib).

-

Adults with diagnosis of PSC should have IgG-4 serum levels measured to rule out IgG-4 cholangitis, for appropriate management.

IIb. PSC: Pharmacological treatment

-

After detailed discussion of risks and benefits of therapy, and about the limitations of available data, adult patients with PSC can consider the use of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) in intermediate doses (17-23 mg/kg/day) (Class IIb).

-

Patients with PSC on treatment with UDCA should be regularly monitored with clinical examination and liver tests, to assess response to therapy and to identify possible disease progression (Class I).

-

In patients treated with UDCA, (17-23 mg/kg/day) normalization or significant reduction of serum levels of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) suggests better prognosis (Class II). There is no evidence that UDCA should be discontinued in the absence of response, except when the progression of the disease is possibly related to UDCA itself (Class II).

-

There is no sufficient evidence to recommend the use of fibrates or other pharmacological alternatives as specific therapies for PSC (Class IIb).

-

Immunosuppression with corticosteroids alone or in combination with azathioprine can be considered in cases of PSC with AIH-like characteristics and for the treatment of PSC associated IgG4 (Class I).

-

There is no evidence that the use of UDCA reduces the risk of developing colon cancer or gallbladder cancer in patients with PSC (Class III).

-

Pregnancy is generally well tolerated in women with compensated PSC, but there are reports of increased risk of preterm birth (Class II). The use of UDCA can be considered during pregnancy, preferably after the first quarter (Class II).

IIc. PSC: Endoscopic treatment

-

Endoscopic treatment can be indicated in sites with expertise in therapeutic ERC in subjects with PSC with dominant strictures (Class IIb).

-

Dominant stricture is defined as a stenosis with a diameter <1.5 mm in the common bile duct or <1 mm in a hepatic duct based on ERC findings (Class I).

-

Ductal sampling (brush cytology and/or endobiliary biopsies) during ERCP is recommended for all patients with PSC and dominant strictures to exclude cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) (Class IIb). Brush cytology combined with fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) increases test sensitivity and should be performed if available (Class I).

-

Routine administration of prophylactic antibiotics before ERC in patients with PSC is recommended (Class IIb).

-

ERC with balloon dilatation is the recommended approach in symptomatic patients with PSC and dominant stricture (Class I). Stent placement after dilation is not routinely recommended as it can increase the risk of bacterial cholangitis (Class III). Stenting may be necessary for a short period of time in cases of severe strictures (Class IIa).

IId. PSC: Diagnostic and therapeutic implications in children

-

Insufficient reports of PSC in children make it impossible to establish evidence-based recommendations for the management of the disease within the pediatric age group (Class I).

-

Clinical manifestations are similar to those observed in adults. Dominant strictures and CCA is rarely seen. On the contrary, AIH and PSC overlap is much more common (Class IIa).

-

MRCP is the procedure of choice for diagnosis of PSC in children. Liver biopsy can be considered to rule out other common causes of secondary sclerosing cholangitis (Class IIa).

-

Colonoscopy should be performed to assess concurrent inflammatory bowel disease (Class IIa).

-

There is insufficient data concerning treatment options for PSC.

III. PRIMARY BILIARY CHOLANGITIS:

IIIa. PBC: Diagnosis

-

AASLD criteria should be adopted for initial evaluation of PBC patients (Class I).

-

PBC diagnosis is established when two of the following criteria are met: sustained elevation of ALP; presence of AMA or other PBC-specific autoantibodies (including sp100 or gp210, if AMA is negative) and liver biopsy demonstrating non-suppurative destructive cholangitis and destruction of interlobular bile ducts.

-

Regarding autoantibodies: AMA titers ≥1:80 are considered significant. Anti-M2 antibodies should be tested either if AMA is negative or if the titre of AMA is <1:80 or its pattern is not typical (Class I).

-

Testing for ANA and pattern characterization [nuclear dots (sp100) or nuclear envelope (gp210)] by indirect immunofluorescence in HEp-2 cells or by immunoblotting and ELISA can be requested in AMA negative patients, to assess for PBC-specific ANAs (Class IIa).

-

Liver biopsy is recommended in AMA-negative patients and/or when associated liver disease is suspected (Class I).

-

Non-invasive methods for staging are under investigation and cannot be routinely recommended, but transient elastography can be used as a prognostic tool. The role of serial measurements as an endpoint is under evaluation (Class IIb).

IIIb. PBC: Treatment with UDCA

-

All patients with PBC and elevated serum ALP should be treated with UDCA 13-15 mg/kg/day, even if asymptomatic at presentation (Class I).

-

If use of bile acid sequestrants is necessary for treatment of pruritus, UDCA should be administered 4 hours prior to or after its ingestion (Class I).

-

Response to therapy should be evaluated after 1 year of treatment. This may be done by different approaches (Class IIa).

IIIc. PBC: Treatment of patients with inadequate response to UDCA

-

There is no agreement with regards to the best criteria to determine biochemical response to UDCA. Given costs and ease to use, we suggest using Paris II criteria (FA ≥1.5X ULN or AST ≥1.5X ULN or BT >1 mg/dL) (Class IIa).

-

Biochemical response should be evaluated after 1 year of treatment with UDCA to assess prognosis and determine need for adjuvant therapy (Class IIa).

-

Clinicians may use the UK-PBC score or the GLOBE PBC score after 1 year of therapy with UDCA to help determine who needs adjuvant therapy (Class IIa).

-

There is no consensus with respect to treatment of patients with incomplete response to UDCA. We recommend assessing patients’ compliance with therapy and considering alternative or concomitant diagnoses. A liver biopsy may be needed at the hepatologist’s discretion (Class IIa).

-

Benzafibrate 400 mg/day associated with UDCA can be considered as an off-label alternative for patients with PBC and inadequate response to UDCA (Class IIb), but the use of fibrates is discouraged in patients with decompensated liver disease (Child- Pugh-Turcotte B or C) (Class IIa).

-

Budesonide may be considered in patients with PBC, stage I-II and incomplete response to UDCA, especially if there is marked inflammatory activity (Class IIb).

IV. OVERLAP SYNDROMES OF AUTOIMMUNE DISEASES OF THE LIVER

-

Autoimmune diseases of the liver should be categorized according to their predominant features as AIH, PBC, PSC and small-duct PSC. Overlap syndromes should not be viewed as distinct diagnostic entities (Class I).

-

In the presence of relevant overlapping clinical, laboratory, histological and cholangiographic features of more than one ALD in the same patient, the diagnosis should be based on the predominating disease: AIH, PBC, PSC or small-duct PSC with the addition of the presence of features of another ALD (Class IIb).

-

IAIHSG diagnostic criteria should not be used to diagnose overlap of AIH with either PBC or PSC (Class IIa).

-

Patients with AIH with features of either PBC or PSC and vice versa should be referred to sites with expertise in diagnosis and treatment of ALD (Class IIb).

-

Paris criteria can be useful to characterize AIH-PBC overlap, but they are not entirely validated to be used in clinical practice (Class IIb).

-

Patients with PSC and PBC with features of AIH should be considered for treatment with immunosuppressants (Class IIb).

-

Combined treatment of UDCA and immunosuppression can be considered for patients with AIH with features of PBC (Class IIb).

V. PRURITUS

-

Pruritus is frequently observed in PBC and PSC, and tend to decrease in frequency and intensity with disease progression to cirrhosis (Class I).

-

Treatment of pruritus should be gradual until resolution or improvement of symptoms, using 1st line drugs such as cholestyramine (4-16 g/daily), 2nd line drugs such as rifampicin (150-600 mg/daily), 3rd line drugs such as naltrexone (12.5-50 mg/daily) and 4th line drugs such as sertraline (50-100 mg/daily) (Class I- IIa).

-

The presence of refractory pruritus should be considered in the presence of failure to control itching under maximal doses of cholestyramine, rifampicin, naltrexone and sertraline (Class I).

-

Antihistamines and UDCA cannot not be recommended for treatment of pruritus, with the exception of UDCA in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (Class I).

-

Due to its effect in pruritus, fibrates may be employed for treatment of pruritus in patients with PBC and PSC (Class IIa).

VI. FATIGUE AND HYPERCHOLESTEROLEMIA

-

Fatigue is frequently observed in cholestatic liver diseases, particularly PBC (Class I).

-

Diagnosis of depression, anemia, hypothyroidism and fatigue-inducing drugs should be excluded (Class IIa).

-

There is no approved treatment for fatigue and symptom remission after LT is uncertain (Class IIb).

-

Frequent bed rest, avoidance of sleep deprivation and psychological support are important in the management of fatigue (Class IIa).

-

Hyperlipidemia with high total cholesterol, LDL and HDL-cholesterol is frequently found in subjects with cholestasis, particularly in PBC (Class I).

-

There is no data to support higher risk of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events in subjects with cholestasis (Class IIb).

-

Statins, when required, are considered safe and effective for treatment of hyperlipidemia in cholestatic liver diseases (Class IIb).

VII. OSTEOPOROSIS AND OSTEOPENIA

-

Bone densitometry is the gold-standard test for diagnosis of bone loss and should be performed in subjects with history of spontaneous fractures, chronic use of corticosteroids, diagnosis of PBC and PSC, under evaluation for or after LT and advanced cirrhosis or cholestasis irrespective of etiology, with additional risk factors for bone loss (Class I).

-

Bone densitometry should be repeated every two to three years in subjects without bone loss at the first test. Annual re-evaluations are necessary in subjects with advanced cirrhosis, after LT or with the use of high doses of corticosteroids (Class I).

-

Use of WHO FRAX score is recommended for assessing fracture risk and guide therapy in patients with cholestatic ALD and AIH under corticosteroid treatment for more than three months (Class I).

-

Management of bone loss should involve lifestyle changes, including quit smoking, alcohol and excessive coffee drinking, practice of physical activity and a well balanced diet rich in calcium and vitamin D. (Class IIa).

-

Supplementation of calcium (1000-1500 mg/daily) and vitamin D (400-800 IU/daily) should be considered in patients with low risk of fractures or in association with bisphosphonates in subjects with moderate/high risk of fractures, according to WHO FRAX score (Class IIa).

-

Weekly alendronate and monthly ibandronate can be employed without distinction, but treatment adherence is better with ibandronate. Use with caution in subjects with esophageal varices and consider parenteral bisphosphonates in the aforementioned patients (Class IIa).

VIII. SPECIAL TOPICS

VIIIa. Recurrent cholangitis

-

Patients with recurrent cholangitis due to biliary tract disease, refractory or not, amenable to medical, endoscopic or surgical treatments should be included and prioritized in a liver transplantation waiting list (Class I).

-

MELD-exception points should be given to those patients with recurrent cholangitis in the presence of: a) two or more episodes of cholangitis in at least six months; b) one episode of recurrent cholangitis with extrahepatic sepsis, severe sepsis or septic shock (not associated with biliary tract procedures) or c) due to infection with multiresistant bacteria (Class IIa).

-

Antibiotic prophylaxis should be given to those patients with PSC or with any other disease associated with biliary obstruction undergoing ERC in order to prevent cholangitis, particularly in the presence of inadequate biliary drainage (Class IIa).

VIIIb. Screening of liver and biliary tract cancer

-

Patients with PSC are at increased risk for hepatobiliary neoplasias, particularly CCA and gallbladder cancer (Class I).

-

In the absence of evidence-based data, ultrasound should be performed at least yearly for assessment of CCA in association with measurement of CA19-9 levels (Class IIb). MRCP should be performed in those patients with suspected CCA based on clinical and laboratory findings (Class IIb). ERC with brushing cytology or endobiliary biopsies are recommended to establish the diagnosis of biliary tract cancer (Class IIb).

-

Screening for gallbladder cancer should be performed with yearly ultrasound in subjects with PSC. Cholestycstectomy is recommended for gallbladder polyps >8 mm. Smaller polyps need to be monitored closely with serial ultrasounds. The surgical indication should consider the cost-benefit ratio between the risk of clinical decompensation and the high incidence of gallbladder neoplasia in this population (Class IIa).

-

Screening for hepatocelular carcinoma should be performed every six months in subjects with cirrhosis due to PSC (Class IIa).

VIIIc. Liver transplantation (LT) for AIH, PBC and PSC

-

Patients with AIH, PSC and PBC, as well as with other liver diseases should be referred for LT in the presence of complications of portal hypertension and liver failure assessed by the MELD score (Class I).

-

Intractable pruritus and refractory recurrent cholangitis should be considered a priority, with extra-MELD points awarded to subjects with PBC and PSC (Class I).

-

LT is not recommended to the management of AIH refractory to treatment in the absence of complications of liver failure and portal hypertension (Class IIa).

-

LT may be justified for those patients with decompensation of liver disease due to flares of AIH caused by poor adherence to treatment or spontaneous disease reactivation. In those cases, drug adjustments should be initially employed with care, due to the higher risk for infection. In the absence of improvement, LT should be considered (Class IIb).

-

Use of prognostic scores for indication of LT for PSC and PBC still requires better validation. At the present time, MELD remains the best score for indication of LT and organ allocation (Class IIa).

-

When LT is considered for AIH, withdrawal or dose reduction of immunosuppressive therapy may be employed when LT appears to be imminent (Class IIb).

-

Maintenance of UDCA in subjects with PSC and PBC in the waiting list for LT is controversial, since its impact on the survival of those patients with end-stage liver disease is probably negligible (Class IIb).

-

In subjects with acute liver failure under suspicion for AIH, after exclusion of other causes of liver disease, even in the absence of autoantibodies, initiation of immunosuppressive therapy should be attempted if there is no evidence of active infection. Based on experts’ opinion, use of oral or intravenous prednisolone may be attempted, but the dosage still needs to be better established (Class IIa). Treatment should be re-evaluated in five to seven days and corticosteroids should be discontinued in the absence of clinical and laboratory improvement. LT should not be postponed in this setting (Class IIb).

-

Subjects undergoing LT for AIH should receive higher doses of immunosuppression after LT, with two or three drugs. The need for maintenance of low doses of corticosteroids indefinitely is controversial in the literature and should be considered in patients with repeated episodes of acute cellular rejection and in those with a high risk of disease recurrence after LT, such as significant inflammatory activity in the explant, high levels of IgG in the immediate pre-transplant, disagreement of HLA-DR3 between donor and recipient (positive receptor/negative donor) (Class IIa).

-

Protocol liver biopsies may increase the diagnosis of AIH recurrence after LT in patients without clinical and biochemical signs of liver disease but, in this setting, the benefit of treatment is unclear and the decision must be individualized on a case-by-case basis (Class IIb). To this date, the role of protocol liver biopsies in PBC and PSC is even less clear and can not be recommended (Class IIb).

-

Cyclosporine-based immunosuppression should be considered for subjects undergoing LT for PBC, since the use of tacrolimus has been associated with an increased rate of recurrent PBC (Class IIa).

-

Recurrent PBC is only rarely clinically relevant; there is insufficient data to recommend preemptive usage of UDCA but it appears to improve liver biochemistry and delay histological progression of recurrent disease. The influence of UDCA on the natural history of recurrent PBC still needs to be determined (Class IIb).

-

Patients with PSC and IBD should continue to undergo annual colonoscopy after LT, due to the increased risk of colonic neoplasia (Class IIa).

REFERENCES

-

1Bittencourt PL, Cançado EL, Couto CA, Levy C, Porta G, Silva AE, et al. Brazilian society of hepatology recommendations for the diagnosis and management of autoimmune diseases of the liver. Arq Gastroenterol. 2015;52 (Suppl 1):15-46.

-

2Beuers U, Gershwin ME, Gish RG, Invernizzi P, Jones DEJ, Lindor K, et al. Changing nomenclature for PBC: from ‘cirrhosis’ to ‘cholangitis’. J Hepatol. 2015;63:1285-7.

-

3Methodology Manual for ACC/AHA Guideline Writing Committees: Methodologies and Policies from the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines. April; 2006. 2006.

-

4Gronbaek L, Vilstrup H, Pedersen L, Christensen K, Jepsen P. Family occurrence of autoimmune hepatitis: A Danish nationwide registry-based cohort study. J Hepatol. 2018;69:873-7.

-

5Wong GW, Yeong T, Lawrence D, Yeoman AD, Verma S, Heneghan MA. Concurrent extrahepatic autoimmunity in autoimmune hepatitis: implications for diagnosis, clinical course and long-term outcomes. Liver Int. 2017;37:449-57.

-

6Cancado ELR, Abrantes-Lemos CP, Terrabuio DRB. The importance of autoantibody detection in autoimmune hepatitis. Front Immunol. 2015;6:222.

-

7Vergani D, Alvarez F, Bianchi FB, Cançado EL, MacKay IR, Manns MP, et al. Liver autoimmune serology: a consensus statement from the committee for autoimmune serology of the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. J Hepatol. 2004;41:677-83.

-

8Zachou K, Gampeta S, Gatselis NK, Oikonomou K, Goulis J, Manoussakis MN, et al. Anti-SLA/LP alone or in combination with anti-Ro52 and fine specificity of anti-Ro52 antibodies in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Liver Int . 2015;35:660-72.

-

9Liaskos C, Bogdanos DP, Rigopoulou EI. Antibody responses specific for soluble liver antigen co-occur with R0-52 antibodies in patients with autoimmune hepatitis (abstract). J Hepatol. 2007;46 (Suppl 1):S250.

-

10Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D, Baumann U, Czubkowski P, Debray D, Dezsofi A, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Pediatric Autoimmune Liver Disease: ESPGHAN Hepatology Committee Position Statement. Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66:345-60.

-

11Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, Parés A, Dalekos GN, Krawitt EL, et al. Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48:169-76.

-

12European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Autoimmune Hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2015;63:971-1004.

-

13Kanzler S, Gerken G, Löhr H, Galle PR, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH, Lohse AW. Duration of immunosuppressive therapy in autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2001;34:354-5.

-

14Couto CA, Bittencourt PL, Porta G, Abrantes-Lemos CP, Carrilho FJ, Guardia BD, et al. Antismooth muscle and antiactin antibodies are indirect markers of histological and biochemical activity of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2014;59:592-600.

-

15Terrabuio DRB, Diniz MA, Falcão LTM, Guedes ALV, Nakano LA, Evangelista AS, et al. Chloroquine Is Effective for Maintenance of Remission in Autoimmune Hepatitis: Controlled, Double-Blind, Randomized Trial. Hepatol Commun. 2018;3:116-28.

-

16Tomasulo P. LactMed-new NLM database on drugs and lactation. Med Ref Serv Q. 2007;26:51-8.

-

17Ponticelli C, Moroni G. Fetal toxicity of immunosuppressive Drugs in Pregnancy. J Clin Med 2018;7. Pii: E552.

-

18Dave M, Elmunzer BJ, Dwamena BA, Higgins PD. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: meta-analysis of diagnostic performance of MR cholangiopancreatography. Radiology 2010;256:387-96.

-

19Aabakken L, Karlsen TH, Albert J, Arvanitakis M, Chazouilleres O, Dumonceau JM, et al. Role of endoscopy in primary sclerosing cholangitis: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) and European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2017;49:588-608.

-

20Razumilava N, Gores GJ, Lindor KD. Cancer surveillance in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2011;54:1842-52.

-

21Weismüller TJ, Trivedi PJ, Bergquist A, Imam M, Lenzen H, Ponsioen CY; International PSC Study Group. Patient Age, Sex, and Inflammatory Bowel Disease Phenotype Associate With Course of Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1975-84.

-

22Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis, Part 2: cancer risk, prevention and surveillance. Tabibian JH, Ali AH, Lindor KD. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;14:427-32.

-

23Karlsen TH, Folseraas T, Thorburn D, Vesterhus M. Primary sclerosing cholangitis - a comprehensive review. J Hepatol. 2017;67:1298-323.

-

24Brand M, Bizos D, O’Farrell P Jr. Antibiotic prophylaxis for patients undergoing elective endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010.

-

25Hirschfield GM, Beuers U, Corpechot C, Invernizzi P, Jones D, Marzioni M, et al. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: The diagnosis and management of patients with primary biliary cholangitis. European Association for the Study of the Liver. J Hepatol. 2017;67:145-50.

-

26Lindor KD, Bowlus CL, Boyer J, Levy C, Mayo M. Primary Biliary Cholangitis: 2018 Practice Guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2019;69:394-419.

-

27Corpechot C, Carrat F, Poujol-Robert A, Gaouar F, Wendum D, Chazouilleres O, et al. Noninvasive elastography-based assessment of liver fibrosis progression and prognosis in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2012;56:198-208.

-

28Corpechot C, El Naggar A, Poujol-Robert A, Ziol M, Wendum D, Chazouilleres O, et al. Assessment of biliary fibrosis by transient elastography in patients with PBC and PSC. Hepatology. 2006;43:1118-24.

-

29Corpechot C. Utility of Noninvasive Markers of Fibrosis in Cholestatic Liver Diseases. Clin Liver Dis. 2016;20:143-58.

-

30Lammers WJ, Hirschfield GM, Corpechot C, Nevens F, Lindor KD, Janssen HL, et al; Global PBC Study Group. Development and Validation of a Scoring System to Predict Outcomes of Patients With Primary Biliary Cirrhosis Receiving Ursodeoxycholic Acid Therapy. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1804-12.

-

31Carbone M, Sharp SJ, Flack S, Paximadas D, Spiess K, Adgey C, et al. The UK-PBC Risk Scores: Derivation and validation of a scoring system for long-term prediction of end-stage liver disease in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2016;63:930-50.

-

32Corpechot C, Chazouilleres O, Poupon R. Early primary biliary cirrhosis: biochemical response to treatment and prediction of long-term outcome. J Hepatol. 2011;55:1361-67.

-

33Corpechot C, Chazouillères O, Rousseau A, Guyader D, Habersetzer F, Mathurin P, et al. A 2-year multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of bezafibrate for the treatment of primary biliary cholangitis in patients with inadequate biochemical response to ursodeoxycholic acid therapy (Bezurso). J Hepatol. 2017;66:S89.

-

34Corpechot C, Chazouillères O, Rousseau A, Le Gruyer A, Habersetzer F, Mathurin P, et al. A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Bezafibrate in Primary Biliary Cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2171-81.

-

35Buckley L, Guyatt G, Fink HA, Cannon M, Grossman J, Hansen KE, et al. American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Prevention and Treatment of Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:1521-37.

-

36Guanabens N, Monegal A, Cerda D, Muxi A, Gifre L, Peris P, et al. Randomized trial comparing monthly ibandronate and weekly alendronate for osteoporosis in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2013;58:2070-8.

-

37Czaja AJ. Acute and acute severe (fulminant) autoimmune hepatItis. Dig Dis Sci 2013;5:897-914.

-

38Yeoman AD, Westbrook RH, Zen Y, Bernal W, Al-Chalabi T, Wendon JA, et al. Prognosis of acute severe autoimmune hepatitis (AS-AIH): The role of corticosteroids in modifying outcome. J Hepatol, 2014;61:876-82.

-

39Weiler-Normann C, Lohse AW. Acute autoimmune hepatitis: Many open questions. Editorial. J Hepatol. 2014;61:727-29.

-

40Theocharidou E, Heneghan MA. Con: Steroids Should Not Be Withdrawn in Transplant Recipients With Autoimmune Hepatitis. Liver Transpl. 2018;24:1113-8.

-

41Hirschfield GM, Dyson JK, Alexander GJM, Chapman MH, Collier J, Hübscher S, et al. The British Society of Gastroenterology /UK-PBC primary biliary cholangitis treatment and management guidelines. Gut. 2018;67:1568-94.

-

42Montano-Loza AJ, Hansen BE, Corpechot C, Roccarina D, Thorburn D, Trivedi P, et al.; Global PBC Study Group. Factors Associated With Recurrence of Primary Biliary Cholangitis After Liver Transpl antation and Effects on Graft and Patient Survival. Gastroenterology . 2019;156:96-107.

-

43Martin EF, Levy C. Timing, management, and outcomes of liver transplantation in Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. Semin Liv Dis. 2017;37:305-13.

-

44Chandok N, Watt KD. Burden of De Novo Malignancy in the Liver Transpl ant Recipient. Liver Transplantation. 2012;18:1277-89.

-

Disclosure of funding: no funding received

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

26 Aug 2019 -

Date of issue

Apr-Jun 2019

History

-

Received

14 May 2019 -

Accepted

04 June 2019