Abstracts

OBJECTIVE: Evaluate the Glasgow outcome scale (GOS) at discharge (GOS-HD) as a prognostic indicator in patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI). METHOD: Retrospective data were collected of 45 patients, with Glasgow coma scale <8, age 25±10 years, 36 men, from medical records. Later, at home visit, two measures were scored: GOS-HD (according to information from family members) and GOS LATE (12 months after TBI). RESULTS: At discharge, the ERG showed: vegetative state (VS) in 2 (4%), severe disability (SD) in 27 (60%), moderate disability (MD) in 15 (33%) and good recovery (GR) in 1 (2%). After 12 months: death in 5 (11%), VS in 1 (2%), SD in 7 (16%), MD in 9 (20%) and GR in 23 (51%). Variables associated with poor outcome were: worse GOS-HD (p=0.03), neurosurgical procedures (p=0.008) and the kind of brain injury (p=0.009). CONCLUSION: The GOS-HD was indicator of prognosis in patients with severe TBI.

brain Injuries; Glasgow coma scale; Glasgow outcome scale; prognosis

OBJETIVO: Avaliar a escala de resultados de Glasgow (ERG) à alta hospitalar (ERG-ALTA) como indicador prognóstico em pacientes com traumatismo cranioencefálico (TCE). MÉTODO: Dados retrospectivos de 45 pacientes (36 homens), com escala de coma de Glasgow <8, idade 25±10 anos, foram coletados do prontuário médico. Posteriormente, em visita domiciliar, foram pontuadas duas medidas: ERG-ALTA (de acordo com informações de familiares) e ERG TARDIA (após 12 meses do TCE). RESULTADOS: Por ocasião da alta hospitalar, a ERG evidenciou: estado vegetativo (EV) em 2 (4%); incapacidade grave (IG) em 27 (60%), incapacidade moderada (IM) em 15 (33%) e boa recuperação (BR) em 1 (2%). Após 12 meses: morte em 5 (11%), EV em 1 (2%), IG em 7 (16%), IM em 9 (20%) e BR em 23 (51%). Variáveis associadas com má evolução foram: pior ERG-ALTA (p=0,03); procedimentos neurocirúrgicos (p=0,008) e o tipo de lesão cerebral (p=0,009). CONCLUSÃO: A ERG-ALTA foi indicador adequado de prognóstico tardio em pacientes com TCE grave.

traumatismos encefálicos; escala de coma de Glasgow; escala de resultado de Glasgow; prognóstico

ARTICLE

Glasgow outcome scale at hospital discharge as a prognostic index in patients with severe traumatic brain injury

Escala de resultados de Glasgow por ocasião da alta hospitalar como indicador prognóstico em pacientes com traumatismo cranioencefálico grave

Rosmari A.R.A. OliveiraI; Sebastião AraújoII; Antonio L.E. FalcãoII; Silvia M.T.P. SoaresI; Carolina KosourIII; Desanka DragosavacII; Eliane A. CintraIV; Ana Paula D. CardosoII; Rosana A. ThiesenIII

IProfessor, Faculty of Physiotherapy, Pontifical University Catholic of Campinas (PUC-Campinas), Campinas SP, Brazil

IIAssistant Professor, Department of Surgery, State University of Campinas (UNICAMP), Campinas SP, Brazil

IIIPhysiotherapist, Hospital of Clinics, UNICAMP, Campinas SP, Brazil

IVRegistered Nurse, Intensive Care Unit, Hospital of Clinics, UNICAMP, Campinas SP, Brazil

Correspondence Correspondence: Rosmari Aparecida Rosa Almeida de Oliveira Rua Alfredo Vieira Alves 33 / Residencial Shangrilá 13098-608 Campinas SP - Brasil E-mail: rrosmari@terra.com.br

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE: Evaluate the Glasgow outcome scale (GOS) at discharge (GOS-HD) as a prognostic indicator in patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI).

METHOD: Retrospective data were collected of 45 patients, with Glasgow coma scale <8, age 25±10 years, 36 men, from medical records. Later, at home visit, two measures were scored: GOS-HD (according to information from family members) and GOS LATE (12 months after TBI).

RESULTS: At discharge, the ERG showed: vegetative state (VS) in 2 (4%), severe disability (SD) in 27 (60%), moderate disability (MD) in 15 (33%) and good recovery (GR) in 1 (2%). After 12 months: death in 5 (11%), VS in 1 (2%), SD in 7 (16%), MD in 9 (20%) and GR in 23 (51%). Variables associated with poor outcome were: worse GOS-HD (p=0.03), neurosurgical procedures (p=0.008) and the kind of brain injury (p=0.009).

CONCLUSION: The GOS-HD was indicator of prognosis in patients with severe TBI.

Key words: brain Injuries, Glasgow coma scale, Glasgow outcome scale, prognosis.

RESUMO

OBJETIVO: Avaliar a escala de resultados de Glasgow (ERG) à alta hospitalar (ERG-ALTA) como indicador prognóstico em pacientes com traumatismo cranioencefálico (TCE).

MÉTODO: Dados retrospectivos de 45 pacientes (36 homens), com escala de coma de Glasgow <8, idade 25±10 anos, foram coletados do prontuário médico. Posteriormente, em visita domiciliar, foram pontuadas duas medidas: ERG-ALTA (de acordo com informações de familiares) e ERG TARDIA (após 12 meses do TCE).

RESULTADOS: Por ocasião da alta hospitalar, a ERG evidenciou: estado vegetativo (EV) em 2 (4%); incapacidade grave (IG) em 27 (60%), incapacidade moderada (IM) em 15 (33%) e boa recuperação (BR) em 1 (2%). Após 12 meses: morte em 5 (11%), EV em 1 (2%), IG em 7 (16%), IM em 9 (20%) e BR em 23 (51%). Variáveis associadas com má evolução foram: pior ERG-ALTA (p=0,03); procedimentos neurocirúrgicos (p=0,008) e o tipo de lesão cerebral (p=0,009).

CONCLUSÃO: A ERG-ALTA foi indicador adequado de prognóstico tardio em pacientes com TCE grave.

Palavras-Chave: traumatismos encefálicos, escala de coma de Glasgow, escala de resultado de Glasgow, prognóstico.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) has been increasing in civilian population in a direct relationship to technological development, especially due to the great number of motor vehicle accidents and urban violence. Nowadays it represents a serious public health problem, carrying high levels of morbidity and mortality and expressive social-economic impacts1-3.

In Brazil, statistical data regarding traumatic injuries are not clear, but seems to indicate that about 84.4% of traffic and urban violence victims have some degree of associated TBI4. In 1998, 20,000 deaths secondary to motor vehicle accidents were registered, and 60% of the survivors have shown some degree of definitive sequelae. Economical burden has been estimated to be greater than two billion dollars/year5, mainly due to the fact that TBI victims are generally young adults, in their most productive life phase, thus seriously compromising their professional capacity and health quality.

The early identification of brain injury severity is extremely important in TBI patients since many secondary damages can be prevented or minimized by applying correct therapeutic maneuvers, reducing, in this way, their adverse effects in the final patient outcome1,6.

For an adequate pre-hospital management, emergency medical services has been extensively improved, not only by incorporation of new technologies, but also by training and continuous education of health care professionals, according to national and international advanced trauma life support guidelines.

At hospital admission in the emergency room, besides application of Glasgow coma scale (GCS), these patients must be routinely evaluated by means of an extensive and careful clinical neurological examination and subsidiary tests that can guide their correct management, thus avoiding critical and irreversible lesions7,8. However, not withstanding the most careful management of these victims, from pre-hospital care to post-hospital discharge rehabilitation, it has been observed that TBI is responsible for serious sequelae, and this fact justifies more detailed researches to investigate their long-term outcome with the aim to prevent or mitigate them.

In this way, the Glasgow outcome scale (GOS), described by Jennett and Bond9 in 1975, has been extensively employed to outcome evaluation of TBI patients take into consideration their physical, social and cognitive sequelae10-13. Despite some controversies regarding GOS reliability, it is widespread used to evaluate long-term outcome of severe brain injured patients14.

In the international medical literature some investigations that have applied the GOS to evaluate TBI patients' outcome are found15-20. However, in Brazil, reports in this field are scarce. In addition, to our knowledge, there was not a single investigation that has employed GOS at hospital discharge (GOS-HD) as a tool to estimate long-term prognosis in severe TBI patients.

In this way, the main objective of the present study was to evaluate if GOS-HD can be employed as a long-term prognostic index in severe TBI patients.

METHODS

The research protocol was approved by Institutional Ethics Research Review Board (Certificate nº 301/2000) at University of Campinas (UNICAMP), São Paulo, Brazil.

The investigation was carried out in two phases: the first one, retrospective, at the Hospital of Clinics-UNICAMP, with patients' selection from our intensive care unit (ICU) data bank, as previously reported by Falcão et al.6, and getting information from their medical records; and the second one, prospective, including an interview with patients and/or their relatives and performing a detailed clinical neurological evaluation of those who stayed alive.

Forty five severe TBI patients admitted to our ICU were selected from our data bank, according to the following inclusion criteria: age >13 years, both genders, GCS <8 at hospital admission, survival to hospital discharge and an elapsed time >12 months from the TBI at the second phase (prospective one). Exclusion criteria included those lost for late clinical neurological evaluation and those who denied their informed consent to take part in the clinical investigation.

GOS was applied as a tool for neurological evaluation of the TBI patients, both retrospectively, at hospital discharge (GOS-HD), and prospectively, at least one year after TBI (GOS-LATE). According to GOS, TBI patients were classified as: dead (D), vegetative state (VS), severe disability (SD), moderate disability (MD) and good recovery (GR)9.

It is highlighted that GOS was evaluated at both moments (hospital discharge and later) only by one person (the main investigator - Oliveira), as suggested by Anderson, Housley and Jones21 and Hellawel, Signorini and Pentland22.

In the first phase of the study, the patients were selected based on our ICU data bank as previously reported by Falcão et al.6. For those patients who fulfilled inclusion criteria, additional data were obtained from their hospital medical records and registered in a specific form, including: patient's identification, TBI cause, admission GCS, type of brain lesion according to CT scan and hospital outcome. GOS-HD was estimated according to patient's neurological status at hospital discharge.

The patients selected in the first phase of the study (and/or their relatives) were then contacted and invited to participate in the second phase of the investigation, either in hospital dependences or at their homes, as feasible.

In this second phase (prospective one), as long as the patients or their relatives have given their informed consent, a second specific form was filled with data obtained by means of a structured interview and a clinical neurological evaluation performed by the main author. The patients were then classified according to GOS, now denominated GOS-LATE.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using of a computational program Statistical Analysis System (SAS), for Windows, version 8.2. Descriptive analysis was done by constructing frequency tables for categorical variables and position and dispersion measures for continuous variables. To verify the existence of associations or to compare proportions between selected variables, χ2, McNemar, or Fisher's exact tests were employed as fitted. To verify the most important factors that have influenced patients' outcome, logistic regression analysis was employed. Mann-Whitney test was employed to compare continuous or ordered variables between two groups, and Kruskal-Wallis test to compare them between three groups. The results were considered statistically significant when p<0.05.

RESULTS

Forty-five patients composed the study population with 36 men (80%) and 9 women (20%), aging 24.6±10.4 years (mean±SD; median=20 years), and 73% of them were single.

The main TBI causes were: car accidents (47%), motorcycle accidents (27%), accidental falls (11%), pedestrian-automobile accident (9%), assault injuries (4%) and gunshot wounds (2%).

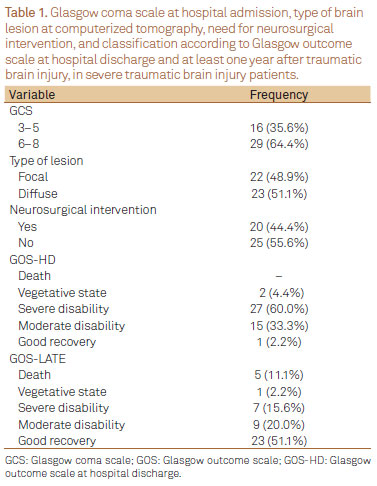

GCS at hospital admission, the type of acute brain lesion at CT scan (focal or diffuse), the need for neurosurgical interventions, and patients' classification according to GOS at hospital discharge (GOS-HD) and at later evaluation (GOS-LATE) are shown in Table 1.

GCS at hospital admission versus GOS-LATE

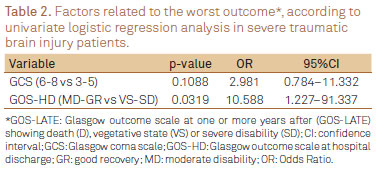

There was no association between categorical GCS at hospital admission (3-5 versus 6-8) and worst outcome according to GOS-LATE (Fisher exact test; p=0.2747). GCS at hospital admission was also not indicative of worst prognosis by univariate logistic regression analysis (p=0.1088) (Table 2).

GOS-HD versus GOS-LATE

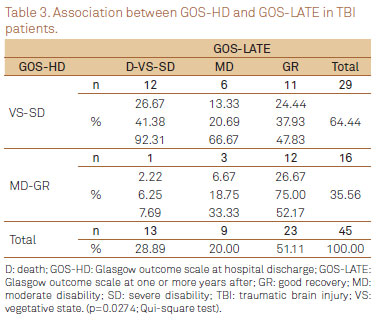

From 64% (29/45) of patients initially classified by GOS-HD as VE and SD, 41% (12/29) remained within this classification by GOS-LATE. However, amongst patients classified as MD or GR (15 and 1, respectively) by GOS-HD, significant improvement was observed, and GOS-LATE has shown GR in 75% of them (12/16). There was a positive and significantly association between GOS-HD and GOS-LATE (χ2 test; p=0.0274). As well, the univariate logistic regression analysis has shown that a worst classification by the GOS-HD was significantly indicative of pour late outcome (p=0.0319) (Table 3).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis

By the application of multivariate logistic regression analysis, as shown in Table 4, it was found that patients classified as MD and GR by GOS-HD have had a greater chance of better outcome according to GOS-LATE when compared to patients initially classified as VS or SD (OR=12.049; 95%IC 1.252-15.989; p=0.0312).

DISCUSSION

National and international epidemiological data have shown that TBI mainly affects young and male healthy people19,23,24. Indeed, in the present investigation, accordingly to these reports, TBI was seen more frequently in young males in a 4:1 proportion in relation to females. The mean patients' age was 24 years, corresponding to their most potentially productive life phase, as emphasized by Brandt et al.23. In accordance with another clinical reports, the main cause of TBI was motor vehicle accidents (74% of the cases)18,24,25.

The socioeconomic impact of TBI was also very impressive, as long as in the present investigation it was observed that almost 50% of the injured patients have shown some degree of long-term neurological sequelae or have been dead according to GOS-LATE.

GOS has been widespread used due to its practicality, simplicity and sensibility, and has been recommended by many experts as a tool to uniformize data and to allow adequate comparisons between results obtained during long-term evaluation of TBI patients26.

In the investigation carried by Wilson, Pettigrew and Teasdale27, including 135 patients, GOS applied at hospital discharge has offered evidence that 97.8% of the patients have shown some degree of neurological disability, with relevant social and economical impact, as long as 40.4% of the patients remained classified as VS or SD one year after the initial TBI. In the present investigation, every patient has shown some degree of neurological disability at hospital discharge. Surprisingly, at least one year later, 71.1% of them have improved, and were classified as MD or GR by GOS-LATE, indicating a substantially better neurological condition than that reported by Wilson, Pettigrew and Teasdale27.

In the literature, many authors have applied GOS to evaluate long-term outcome of TBI patients. Amongst them, it's highlighted the investigation of Jiang et al.28, that evaluated 846 patients with GCS <8 at hospital admission one year after TBI, and found 31.6% of GR, 14.1% MD, 24.3% SD, 0.6% VS and 29.4% dead by GOS classification.

In the present investigation, when the results obtained by GOS-HD were correlated with those measured by GOS-LATE, it was observed a better neurological improvement in patients classified as MD and GR by GOS-HD when compared to those that were graded as VS and SD at the same time (GOS has remained unchanged in 41.4% of them). However, it wasn't possible to estimate the real time needed for patients to accomplish this improvement, as long as they were evaluated by GOS-LATE in many different times elapsed from the initial brain injury.

In addition, Heiden et al.29 were more systematic in their follow-up of TBI patients. These authors, in a prospective study, have evaluated 213 patients one, six and twelve months after TBI applying GOS. They reported the most prevalent GOS classification found at the end of the first month after TBI was SD, and that 16% of the patients were in VS. After six months, 68% of them have shown some neurological improvement (MD and GR were prevalent). At one year after TBI, GOS has shown that 35% of the patients were in MD-GR, 13% in SD- VS and 52% were dead.

Although in the medical literature it could be found many studies that have employed GOS for the long-term follow-up of TBI patients' outcome24,25,28-30, the correlation between GOS-HD and GOS-LATE is scarcely reported31.

As a prognostic index tool, GOS-HD has shown to be highly useful in this investigation, indicating a possibility of later neurological outcome improvement 12 times higher in those patients classified as MD and GR when compared to those that have shown VS and SD (p=0.0312). This is an important finding as it opens some doors for the development of rehabilitation programs aiming to limit or minimize the serious sequelae that are often seen after TBI, condition that has been more and more frequently found in civilian life. Unhappily, this line of investigation has scarcely been reported or discussed worldwide.

Study limitations

Amongst many important limitations of the present investigation that could be responsible for some findings' bias, two of them must be highlighted. First, a retrospective methodology was employed for patients' selection, and only 10% of TBI victims admitted to our ICU during the period selected for data gathering were found for prospectively evaluation. Second, no reliable recordings could be retrieved to clearly known if the selected patients have been undergoing or not to a systematic neurological rehabilitation program just after hospital discharge.

In conclusion, in these severe TBI patients GOS-HD has shown to be a useful long-term prognostic index. Additionally, factors like the type of brain lesion, the need for neurosurgical interventions, the presence of pneumonia and increasing age had also been associated with poor long-term outcome.

ACKNOWLEGDMENTS

We are grateful to Prof. Dr. Renato G.G. Terzi, Department of Surgery, FCM-UNICAMP, for his support in the development of the present investigation, and to Cleide Aparecida Moreira Silva, Research Committee, FCM-UNICAMP, for her assistance in the statistical analysis of data.

Received 06 October 2011

Received in final form 13 January 2012

Accepted 20 January 2012

Conflict of interest: There is no conflict of interest to declare.

- 1. Becker DP, Miller JD, Ward JD, Greenberg RP, Young HF, Sakalas R. The outcome from severe head injury with early diagnosis and intensive management. J Neurosurg 1977;47:491-502.

- 2. Foulkes MA, Eisenberg HM, Jane JA, et al. The traumatic coma data bank design, methods and baseline characteristics. J Neurosurg 1991;75:8-13.

- 3. Arreola-Risa C, Mock CN, Padilha D, Cavazos L, Maier RV, Jurkovich GJ. Trauma care system in urban Latin America: the priorities should be pre-hospital and emergency room management. J Trauma 1995;39:457-462.

- 4. Camargo ABM, Ortiz LP, Fonseca LAM. Evolução da mortalidade por acidentes e violência em áreas metropolitanas. In: Monteiro CA (editor). Velhos e novos males da saúde no Brasil: a evolução do país e suas doenças. São Paulo: HUCITEC; 1995:256-267.

- 5. Mantovani M, Fraga GP. Estudo crítico dos óbitos no trauma: experiência da UNICAMP. In: Freire ECS (editor). Trauma: a doença dos séculos. São Paulo: Atheneu; 2001:2851-2861.

- 6. Falcão ALE, Araújo S, Dragosavac D, et al. Cerebral hemometabolism: variability in the acute phase of traumatic coma. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2000;58:877-882.

- 7. Chesnut MD. Implications of the guidelines for the management of severe head injury for the practicing neurosurgeon. Surg Neurol 1998;50:187-193.

- 8. Finfer SR, Cohen J. Severe traumatic brain injury. Ressuscitation 2001;48:77-90.

- 9. Jennett B, Bond M. Assessment of outcome after severe brain damage: a practical scale. Lancet 1975;1:480-484.

- 10. Stocchetti N, Zanaboni C, Colombo, et al. Refractory intracranial hypertension and "second-tier" therapies in traumatic brain injury. Intensive Care Med 2008;34:461-467.

- 11. Schirmer-Milkalsen K, Vik A, Gisvold SE, Skandsen T, Hynne H, Klepstad P. Severe head injury: control of physiological variables, organ failure and complications in the intensive care unit. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2007;51:1194-1201.

- 12. Rondina C, Videtta W, Petroni G, et al. Mortality and morbidity from moderate to severe traumatic brain injury in Argentina. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2005;20:368-376.

- 13. Kilaru S, Garb J, Emhoff T, et al. Long-term functional status and mortality of elderly patients with severe head injuries. J Trauma 1996;41:957-963.

- 14. Wilson JTL, Pettigrew LEL, Teasdale GM. Structured interviews for the Glasgow Outcome Scale and the Extended Glasgow Outcome Scale: guideline for their use. J Neurotrauma 1998;15:573-585.

- 15. Levati A, Farina ML, Vecchi G, Rossanda M, Marrubini MB. Prognosis of severe head injuries. J Neurosurg 1982;57:779-783.

- 16. Gennarelli TA, Spielman GM, Langfitt TW, et al. Influence of the type of intracranial lesion on outcome from severe head injury. J Neurosurg 1982;56:26-32.

- 17. Asikainen I, Kaste M, Sarna S. Predicting late outcome for patients with traumatic brain injury refirred to a rehabilitation program: a study of 508 Finnish patients 5 years or more after injury. Brain Inj 1998;12:95-107.

- 18. Prat R, Calatayud-Maldonado V. Prognostic factors in posttraumatic severe diffuse brain injury. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1998;140:1257-1261.

- 19. Gómez PA, Lobato RD, Boto GR, De la Lama A, González PJ, de la Cruz J. Age and outcome after severe head injury. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2000;142:373-381.

- 20. Boto GR, Gómez PA, De la Cruz J, Lobato RD. Factores pronósticos en el traumatismo craneoencefálico grave. Neurocirugia (Astur) 2004;15:233-247.

- 21. Anderson SI, Housley AM, Jones PA, Slattery J, Miller JD. Glasgow outcome scale: an inter-rater realiability study. Brain Inj 1993;7:309-317.

- 22. Hellawell DJ, Signorini DF, Pentland B. Simple assessment of outcome after acute brain injury using the Glasgow Outcome Scale. Scand J Rehabil Med 2000;32:25-27.

- 23. Brandt AR, Feres Junior H, Fernandes Junior CJ, Akamine N. Traumatismo cranioencefálico. In: Knobel E (editor). Condutas no paciente grave. 2nd ed. São Paulo: Atheneu; 1999:855-876.

- 24. Dantas-Filho VP, Falcão ALE, Sardinha LA, Facure JJ, Araújo S, Terzi RG. Technical aspects of intracranial pressure monitoring by subarachnoid method in severe head injury. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2001;59:895-900.

- 25. Falcão ALE, Dantas-Filho VP, Sardinha LA, et al. Highlighting intracranial pressure monitoring in patients with severe acute brain trauma. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 1995;53:390-394.

- 26. Langfitt TW. Measuring the outcome from head injuries. J Neurosurg 1978;48:673-678.

- 27. Wilson JT, Pettigrew LE, Teasdale GM. Emotional and cognitive consequences of head injury in relation to the Glasgow outcome scale. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;69:204-209.

- 28. Jiang JY, Gao GY, Li WP, Yu MK, Zhu C. Early indicators of prognosis in 846 cases of severe traumatic brain injury J Neurotrauma 2002;19:869-874.

- 29. Heiden JS, Small R, Caton W, Weiss M, Kurze T. Severe head injury. Clinical assessment and outcome. Phys Ther 1983;63:1946-1951.

- 30. MRC CRASH Trial Collaborators, Perel P, Arango M, et al. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: practical prognostic models based on large cohort of international patients. BMJ 2008;336:425-429.

- 31. Skandsen T, Kvistad KA, Solheim O, Strand IH, Folvik M, Vik A. Prevalence and impact of diffuse axonal injury in patients if moderate and severe head injury: a cohort study of early magnetic resonance imaging findings and 1-year outcome. J Neurosurg 2010;113:556-563.

Correspondence:

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

14 Aug 2012 -

Date of issue

Aug 2012

History

-

Received

06 Oct 2011 -

Accepted

20 Jan 2012 -

Reviewed

13 Jan 2012