Abstract

This paper argues that the concept of social accountability can be useful to explain the transparency and accountability policies adopted by international organizations (IOs). Social accountability is understood as the contributions of civil society actors in the functioning of IOs. In international politics, the recent development of IOs' accountability mechanisms has been challenged by the absence of a world government and the impact of inter-state power relations on the decision-making process of international organizations. The presence of civil society actors can reduce the gap between international organizations and citizens affected by their activities. This article resorts to a specific case study: the World Bank Inspection Panel. The analysis revealed the role of civil society actors in the creation, operation and outcomes of this institution. This analysis shows that the concept of social accountability can be adequate to explain not only the Inspection Panel, but other mechanisms recently developed by international organizations.

Democracy; social accountability; international organizations; inspection panel; World Bank

The current debate on the quality of democracies generated a debate on the performance of political institutions in order to ascertain to what extent they would be compatible with the management of the complex problems of the contemporary world. It is within these assessments that the concepts of transparency and accountability have become relevant. In international politics, this same debate on the quality of democracy had repercussions on the analysis of the possibilities of democratizing international organizations (IOs)1 1 See, in this regard, Buchanan and Keohane, 2006; Fox, 2000 and 2007; Grant and Keohane, 2005; Held, 2004; Hollyer, Rosendorff and Vreeland, 2011; Keohane, 2003, 2006, and 2011; Keohane and Nye, 2003; Keohane, Macedo and Moravcsik, 2009; Moravscik, 2004; among others. . Thus, the use of concepts such as transparency and accountability to assess international organizations is nothing more than transposing the broader debate on the quality of national democracies into the international sphere.

Attempts to democratize international organizations face the characteristic complexity of international politics: absence of global governance, complex interdependence, and increased levels of interaction between state and non-state actors. Therefore, analyzing and operationalizing democratic accountability has become a complex task for these organizations (KEOHANE, 2006KEOHANE, Robert O. (2006), Accountability in world politics. Scandinavian Political Studies. Vol. 29, Nº 02, pp. 75-87.; NYE, 2001NYE Jr., Joseph (2001), Globalization's democratic deficit: how to make international institutions more accountable. Foreign Affairs. Vol. 80, Nº 04. pp. 431-435.; WOODS and NARLIKAR, 2001WOODS, Ngaire e NARLIKAR, Amrika (2001), Governance and the accountability: the WTO, the IMF, and the World Bank. International Social Science Journal. Vol. 53, Nº 170, pp. 569-583.). This article sustains that the concept of social accountability can be appropriate to develop empirical studies on the accountability of IOs. This concept emerged from the democratic experiences of Latin America, characterized by the weakness of traditional accountability mechanisms (such as elections and checks and balances). These experiences have shown the role of played by organized sectors of civil society seeking to exercise influence and control over those responsible for decision-making. These actors can activate a network of intrastate control agencies (PERUZZOTTI and , 2002PERUZZOTTI, Enrique and SMULOVITZ, Catalina (2002), Controlando la política: ciudadanos y medios en las democracias Latinoamericanas. Edited by PERUZZOTTI, Enrique and SMULOVITZ, Catalina. Buenos Aires: Grupo Editorial Temas. 325 pp.., p. 02). In international politics, the weakness of existing accountability mechanisms can also be compensated for by the actions of civil society, which is manifested in the defense of collective interests and contributes to reducing the gap between IOs and the citizens of the national states, as pointed out by Robert Dahl (1994)Dahl, Robert (1994), A democratic dilemma: system effectiveness versus citizen participation. Political Science Quarterly. Vol. 109, Nº 01, pp. 23-34. when discussing the experience of European integration in the early 1990s.

This article argues that the notion of social accountability can be useful to understand the mechanisms of accountability adopted by international organizations, since civil society actors may indeed contribute to the functioning of IOs. In order to develop the argument, the article will resort to a specific case study capable of revealing how social accountability works in practice and its challenges. The study examines the World Bank Inspection Panel, established in 1993, and used by two of the five World Bank Group institutions: IBRD (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development) and the International Development Association (IDA)2 2 The reference to the World Bank in the course of the article refers to two of the five institutions of the World Bank Group: IBRD (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development) and IDA (International Development Association). The other three institutions of the World Bank Group are: the International Finance Corporation (IFC); the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA); and the International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes. When the purpose is to name the five institutions, the term World Bank Group will be used. . The study departs from the literature on accountability in political theory and international politics and examines the World Bank's Panel and documents and reports produced by this organization. The purpose is to identify how civil society actors behaved in the creation, operation and results of the Inspection Panel from 1993 to 2015, so as to demonstrate the adequacy of the concept of social accountability and its application in international politics.

The article is divided into five main sections, in addition to the introduction and the final considerations. The first presents the concepts of accountability in political theory. The second questions the use of concepts in the analysis of international organizations. The third describes the World Bank Inspection Panel. The fourth identifies the civil society contributions to the creation as well as 1996 and 1999 revisions of the Inspection Panel. The fifth identifies the presence of civil society actors as requesters of inspection requests and argues that the concept of social accountability has become instrumental in interpreting the Inspection Panel and other accountability mechanisms developed by international organizations.

Accountability in political theory

Accountability is a polysemous concept, with various meanings and uses in many areas, such as administration, economics, and politics. For the purposes of this article, it refers specifically to the use of the term in the theory and practice of the latter field. As a starting point, therefore, accountability must be defined.

A comprehensive concept, accountability is an integral part of any procedural definition of democracy (SCHMITTER, 1999SCHMITTER, Phillipe C. (1999), The limits of horizontal accountability. In: The self-restraining state: power and accountability in new democracies. Edited by SCHEDLER, Andreas; DIAMOND, Larry, and PLATTNER, Marc F.. London: Lynne Riemer. pp. 59-62.), as it encompasses two articulated and fundamental elements for this regime: accountability and responsiveness of political actors. The first is directly related to the availability of information about the acts practiced by the agents that operate in the state sphere. It is related, therefore, to the instruments of greater or lesser transparency of government. Responsiveness, in turn, means that the preferences of the constituents are effectively considered in the work of those who hold positions in the state bureaucracy. Accountable agencies, institutions and governments are therefore transparent and responsive to society and citizens. In this sense, the discussion about accountability answers an essential question: who controls the controller?

For these constitutive elements to be operationalized, democratic societies have built a series of institutional mechanisms, which traditionally comprise two types of accountability, horizontal and vertical. Guillermo O'Donnell's analyses (1998O'DONNELL, Guillermo (1998), Accountability horizontal e novas poliarquias. Lua Nova. Nº 44, pp. 27-54.; 2000O’DONNELL, Guillermo (2000), Further thoughts on Horizontal Accountability. In: Workshop on “Institutions, Accountability, and Democratic Governance in Latin America”. Notre Dame: Kellogg Institute for International Studies/University of Notre Dame, May 8-9. Draft.) help in the conceptualization of these two types of accountability.

As its name suggests, horizontal accountability is constituted by the controls that agencies of the three branches of government - legislative, executive and judicial - exercise on each other. Of course, the effectiveness of these controls is a function of the symmetry of power and of the relative autonomy of each of these branches in relation to the other two. Multiple mechanisms, organs and/or structures can be cited in this type, such as courts of accounts, parliamentary committees of inquiry, presidential veto, judicial power to judge the acts of other branches, and so on. In this sense, horizontal accountability takes place within government and is closely related to the checks and balances of the American pluralist tradition that dates, at least, from the 'Federalist Papers'.

Vertical accountability is exercised by the constituents over the incumbents, by the voters over the elected. Its main mechanism is, therefore, the elections. The assumption in this case is that citizens would tend to reward good political actors and punish the bad ones by voting; thus, vertical accountability involves actors both within and outside government. It is necessary to emphasize that O'Donnell (2006)O’DONNELL, Guillermo (2006), Notes on various accountabilities and their interrelations. In: Enforcing the rule of law: social accountability in the new Latin American democracies. Edited by PERUZZOTTI, Enrique and SMULOVITZ, Catalina. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 334-343. classifies the media and the civil society actions focused on accountability in this type, considering them as limited in their absence of formal enforcement power – this is the reason why in this section of the article, such actions will be qualified as part of a social type of accountability.

The literature on the subject presents an expressive set of limitations in the functioning of accountability mechanisms, especially in the new polyarchies of the so-called third wave of democratization. In the case of horizontal accountability, the authoritarian tradition in which the executive historically prevails over other branches, especially at the subnational levels of government, hampers the proper operation of checks and balances (O'DONNELL, 2000O’DONNELL, Guillermo (2000), Further thoughts on Horizontal Accountability. In: Workshop on “Institutions, Accountability, and Democratic Governance in Latin America”. Notre Dame: Kellogg Institute for International Studies/University of Notre Dame, May 8-9. Draft.; SCHMITTER, 1999)SCHMITTER, Phillipe C. (1999), The limits of horizontal accountability. In: The self-restraining state: power and accountability in new democracies. Edited by SCHEDLER, Andreas; DIAMOND, Larry, and PLATTNER, Marc F.. London: Lynne Riemer. pp. 59-62..

Authors such as José María Maravall (1999)MARAVALL, José Maria (1999), Accountability and manipulation. In: Democracy, accountability, and representation. Edited by PRZEWORSKI, Adam; STOKES, Suzan C., and MANIN, Bernard. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 154-196. and John Ferejohn (1999)FEREJOHN, John (1999), Accountability and authority: toward a theory of political accountability. In: Democracy, accountability, and representation. Edited by PRZEWORSKI, Adam; STOKES, Suzan C., and MANIN, Bernard. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 131-153. point out that effective vertical accountability in any political system is practically impossible. The combination of fiduciary mandate, information asymmetry favorable to political agents, and episodic elections entails a relatively high degree of independence of the political agent's action from the voter who ultimately nominated him. A disconnection between campaign commitments and effective action in the offices is produced, because, when pushed to the limit, the politician can argue that the circumstances in which such commitments were made change and cause changes in courses of action. Proponents of this position argue that the politician's fear of the voter is too diffuse to ensure that he has his will in fact considered, leaving him awaiting the next election. In environments marked by deficits in civic culture, this situation is aggravated. Jonathan Fox (2000)FOX, Jonathan (2000), Civil society and political accountability: propositions for discussion. Paper. Presented at Institutions, accountability and democratic governance in Latin America. The Helen Kellogg Institute for International Studies. University of Notre Dame., for example, uses the term reverse vertical accountability to designate the strong tendency in these societies for politicians to control voters, either by patronage or by violence.

Beyond these limits, horizontal and vertical types are insufficient to account for the performance of non-state actors in the operationalization of accountability. In view of that, Catalina Smulovitz and Enrique Peruzzotti (2000)SMULOVITZ, Catalina and PERUZZOTTI, Enrique (2000), Societal accountability in Latin America. Journal of Democracy. Vol. 01, Nº 04, pp. 147-158. propose the concept of social accountability, which "involves actions carried out by actors with different degrees of organization who are recognized as legitimate claimants of rights" (SMULOVITZ and PERUZZOTTI, 2000SMULOVITZ, Catalina and PERUZZOTTI, Enrique (2000), Societal accountability in Latin America. Journal of Democracy. Vol. 01, Nº 04, pp. 147-158., p. 03). This is, therefore, the social control exercised outside the state sphere by actors of civil society and the media. Among the actions that comprise this type, the authors cite: the application of strategies of pressure and denunciation; the transformation of local issues into regional, national or international issues (something very close to what Elmer Schattschneider (1960)SHATTSCHNEIDER, Elmer E. (1960), The semisovereign people: a realist's view of democracy in America. Boston: Wadsworth. 180 pp.. calls expansion of the scope of conflicts); and the threat of harm the reputation of political agents and organizations that act inappropriately.

One might object that actions that comprise strategies such as those listed above would not properly be accountability mechanisms, as there is no direct power of investigation, sanction and punishment. However, as the concept formulators themselves state, the main reason for the existence of these actions is precisely to trigger or increase the functioning of traditional vertical and horizontal accountability mechanisms. In addition to the obvious limits of transposing the analysis of the traditional dimensions and mechanisms for the analysis of IOs according to their specificities, it is plausible to recognize the differences in social accountability, because it is built outside the traditional institutions of national states. In this sense, the article proposes that this is a valid tool to analyze to what extent international organizations are porous, that is, accountable, to the demands and pressures of civil society actors.

Accountability in international organizations

In international politics, existing accountability mechanisms operate in a context characterized by the absence of a world government, which limits the possibility of functioning of these mechanisms. For Grant and Keohane (2005)GRANT, Ruth W. and KEOHANE, Robert (2005), Accountability and abuses of power in world politics. The American Political Science Review. Vol. 99, Nº 01, pp. 29-44. and Keohane (2006)KEOHANE, Robert O. (2006), Accountability in world politics. Scandinavian Political Studies. Vol. 29, Nº 02, pp. 75-87., international organizations develop actions that affect people in various parts of the world. Therefore, they must face the challenge of creating accountability mechanisms through which they can establish closer links with citizens, non-state actors and national governments affected by their decisions.

For Grant and Keohane (2005)GRANT, Ruth W. and KEOHANE, Robert (2005), Accountability and abuses of power in world politics. The American Political Science Review. Vol. 99, Nº 01, pp. 29-44., current debates are focused on claims to improve accountability and limit abuses of power in international politics. From these debates, relevant questions have emerged, such as: 01. how should we think about international accountability when there is no global democracy? 02. who should be responsible and according to what standards? (GRANT and KEOHANE, 2005GRANT, Ruth W. and KEOHANE, Robert (2005), Accountability and abuses of power in world politics. The American Political Science Review. Vol. 99, Nº 01, pp. 29-44., p. 29). The answer to these questions implies recognizing that there is a distinction between two models of accountability that can be identified in international politics: participation and delegation. The two models raise a third crucial question in assessing accountability mechanisms in international politics: who has the right to control the holder of power? (GRANT and KEOHANE, 2005GRANT, Ruth W. and KEOHANE, Robert (2005), Accountability and abuses of power in world politics. The American Political Science Review. Vol. 99, Nº 01, pp. 29-44., p. 31). In the participation model, holders of power are evaluated by those affected by their actions. In the delegation model, performance is evaluated by those who entrust power to the holders, that is, the national states (GRANT and KEOHANE, 2005GRANT, Ruth W. and KEOHANE, Robert (2005), Accountability and abuses of power in world politics. The American Political Science Review. Vol. 99, Nº 01, pp. 29-44., pp. 32-33).

Robert Dahl (1999DAHL, Robert (1999), Can international organizations be democratic? A skeptic's view. In: Democracy's edges. Edited by SHAPIRO, Ian and HACKER-CORDÓN, Casiano. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 19-36., p. 19) argued that international organizations are incapable of sustaining democratic deliberation and decision and therefore cannot be democratic. Without incorporating Dahl's skepticism, other authors have questioned the evaluation of democracy in international organizations. This is the case, for example, of Andrew Moravcsik (2004MORAVSCIK, Andrew (2004), Is there a 'democratic deficit' in world politics? A framework for analysis. Government and Opposition. Vol. 39, Nº 02, pp. 336-363., pp. 336-337), who raised a central issue for contemporary international politics: 'would global governance be democratically legitimate or would it suffer from a democratic deficit?' When one considers the distance between citizens and IOs, there would be, in fact, a democratic deficit (MORAVCSIK, 2004MORAVSCIK, Andrew (2004), Is there a 'democratic deficit' in world politics? A framework for analysis. Government and Opposition. Vol. 39, Nº 02, pp. 336-363., p. 336). This is also suggested by Woods and Narlikar (2001WOODS, Ngaire e NARLIKAR, Amrika (2001), Governance and the accountability: the WTO, the IMF, and the World Bank. International Social Science Journal. Vol. 53, Nº 170, pp. 569-583., p. 573). For these authors, this deficit does not preclude the functioning of accountability mechanisms in international politics. In order to analyze them properly, however, it is necessary to recognize the specific conditions under which these mechanisms function in international politics. People elect politicians in the domestic sphere who form governments, which in turn appoint ministers who are members of and select delegations which will represent the states in the WTO (World Trade Organization) or in other international organizations (WOODS and NARLIKAR, (2001)WOODS, Ngaire e NARLIKAR, Amrika (2001), Governance and the accountability: the WTO, the IMF, and the World Bank. International Social Science Journal. Vol. 53, Nº 170, pp. 569-583.. Therefore, the model of delegation of power by Grant and Keohane (2005)GRANT, Ruth W. and KEOHANE, Robert (2005), Accountability and abuses of power in world politics. The American Political Science Review. Vol. 99, Nº 01, pp. 29-44. prevails. Delegation to IOs involves the weight of states in shaping the direction of organizations, in providing key resources for their activities and in decision-making.

For David Held (2004HELD, David (2004), Democratic accountability and political effectiveness from a cosmopolitan perspective. Government and Opposition. Vol. 39, Nº 02, pp. 364-391., pp. 369-370), there is in fact a deficit of accountability related to two interrelated difficulties: on the one hand, power imbalances between Member States and, on the other hand, imbalances between states and non-state actors in the shaping and development of global public policies. Multilateral organizations need to be representative of the States involved, but they rarely are. In addition, there should be agreements to enable dialogue and consultation between the State and non-state actors. These conditions occur only partially in multilateral decision-making bodies. In IOs, there is a problem of representation that appears in international negotiations, in which developed countries are able to send a delegation with a team of negotiators and experts on negotiation issues, while developing countries can send only one representative (HELD, 2004HELD, David (2004), Democratic accountability and political effectiveness from a cosmopolitan perspective. Government and Opposition. Vol. 39, Nº 02, pp. 364-391.).

This set of problems raised by Held (2004)HELD, David (2004), Democratic accountability and political effectiveness from a cosmopolitan perspective. Government and Opposition. Vol. 39, Nº 02, pp. 364-391. appears in the experiences of accountability in international politics. In these experiences, the participation model proposed by Grant and Keohane (2005)GRANT, Ruth W. and KEOHANE, Robert (2005), Accountability and abuses of power in world politics. The American Political Science Review. Vol. 99, Nº 01, pp. 29-44. is more difficult to achieve because it involves that the populations affected by the decisions of the IOs have some direct impact on these decisions. The delegation model, therefore, can work better through accountability mechanisms such as the World Bank Inspection Panel and through civil society activities at different levels (local, national, and international). Such action may partly offset the power imbalances in IOs, as Held (2004)HELD, David (2004), Democratic accountability and political effectiveness from a cosmopolitan perspective. Government and Opposition. Vol. 39, Nº 02, pp. 364-391. noted above.

Then, the concept of social accountability can be useful to think about the experiences of democratization existing in international politics. Civil society actors are pressing the horizontal control agencies to initiate investigations and to monitor the behavior of public officials. It is, therefore, an important dimension of accountability in democracies, especially in those situations where traditional mechanisms do not function properly. This is what can be observed in international politics, in which the mechanisms of accountability created by IOs have limitations. Therefore, it can be argued that the social dimension of accountability would put the IO's efforts into action to seek accountability to the publics affected by their decisions and activities. The World Bank's experience in this regard is relevant for the purposes of analysis.

Before doing so, however, it is necessary to make explicit what civil society under the terms of this article means. For Cohen and Arato (1994)COHEN, Jean L. and ARATO, Andrew (1994), Civil society and political theory. Cambridge: MIT Press. 800 pp.., the civil society is constituted as a space of autonomy of diversified actors in opposition to the coercive logic of the state and of the market. According to Cohen and Arato (1994)COHEN, Jean L. and ARATO, Andrew (1994), Civil society and political theory. Cambridge: MIT Press. 800 pp.., civil society actors seek to promote participatory and deliberative processes through which they can influence the economy and the state and develop their capacity to control both. They are involved in the defense of numerous social and environmental causes, such as the guarantee of diffuse rights (gender, ethnic, ecological, etc), the respect for indigenous peoples, the protection of the environment, and others.

Civil society groups a set of actors such as social movements, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), labor unions, varied types of civil and community associations and individuals. Civil society expresses itself, therefore, both through organized and not organized ways; it is possible to find references to these expressions in several works (GOHN, 2014GOHN, Maria da Glória (2014), A sociedade brasileira em movimento: vozes das ruas e seus ecos políticos e sociais. Cadernos CRH. Vol. 27, Nº 71, pp. 431-441.; LAVALLE, CASTELLO and BICHIR, 2004LAVALLE, Adrián G.; CASTELLO, Graziela, and BICHIR, Renata M. (2004), Quando novos atores saem de cena: continuidades e mudanças na centralidade dos movimentos sociais. Política & Sociedade. Vol. 03, Nº 05, pp. 35-53.; MAIA, 2006MAIA, Rouseley C. M. (2006), Mídia e diferentes dimensões da accountability. E-Compós. Vol. 07, pp. 02-27.). Civil society's subjects can articulate themselves through local grassroots actions, forming networks of local, national and international actors around common themes (issue networks) and are mobilized around different causes and objectives. In the experience of the Inspection Panel, civil society actors with the characteristics described above predominate. In spite of the importance of other connections between the World Bank and private foundations – such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations --, these connections will not be explored in this article, considering that the nature and interests of these foundations do not fit the profile of the actors that use the Inspection Panel. Philanthropic foundations, such as the Bill & Melinda Gates, establish another type of relationship with the Bank, involving donations to social projects, according to the analysis of João Márcio Mendes Pereira (2014PEREIRA, João Márcio Mendes (2014), As ideias do poder e o poder das ideias: o Banco Mundial como ator político-intelectual. Revista Brasileira de Educação. Vol. 19, Nº 56, pp. 77-100., pp. 79-81)3 3 For a detailed analysis of the extensive relationships built by the Bank, see PEREIRA, 2014. .

In the following sections, the Inspection Panel will be examined, taking into account the theoretical issues raised in these first two sections of the article.

A brief description of the Inspection Panel

This section aims at describing and presenting the Inspection Panel, which was established in 1993. In its original proposal, the Panel became one of the most advanced accountability mechanisms developed by an international institution4 4 The World Bank Group has several accountability mechanisms, such as the Compliance Advisor/Ombudsman (CAO), which targets the private sector. The CAO was created in 1999 following a series of consultations with shareholders, business people and NGOs. It operates within the framework of the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA). For an analysis of these other accountability mechanisms of the World Bank Group, see Ebrahim and Herz, 2007, pp. 07-09; Woods and Narlikar, 2001, among others. (WOODS and NARLIKAR, 2001WOODS, Ngaire e NARLIKAR, Amrika (2001), Governance and the accountability: the WTO, the IMF, and the World Bank. International Social Science Journal. Vol. 53, Nº 170, pp. 569-583., p. 576). The Executive Board5 5 In organizational terms, the president of the World Bank Group holds the most important position in the organization's structure. The presidency can influence the choice of "the managing director, the various vice presidents, the chief financial officer, the chief economist, and the unit directors. This select group is called Senior Management" (GUIMARÃES, 2012, p. 82). The organization is governed by five Executive Boards, one for each institution, formed today by 25 directors. However, the same Executive Directors attend the five institutions (GUIMARÃES, 2012, p. 83). For a more detailed description of the Bank's organizational structure, see Guimarães, 2012, pp. 82-85. created the Panel to be an independent vehicle for projects funded by the International Development Association (IDA) or the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) to be subject of inspection requests capable of showing that the harm is the result of procedural failures and of the application of the policies of these two financial institutions. The application can be filed in any language, by a civil society actor, by a representative of the affected people, and even by one of the Bank's Executive Officers.

In organizational terms, the Panel consists of three members of different nationalities appointed by the President of the Bank after consulting the Board of Executive Directors. They are appointed for a five-year term by the Board. The Panel's Establishment Resolution6

6

Resolution nº IBRD 93/10 and Resolution nº IDA 93-6. The full text of the Resolution is available in World Bank, 2009: Appendix VI.

settled the need to: 01. Appoint a staff member to be the Executive Secretary; 02. have sufficient budgetary resources to carry out the activities of the Panel. The Secretariat provides operational and administrative support and assists Panel members in the processing of requests for inspection, in the investigations and in the enquiries made by the requesters. The Secretariat is responsible for: 01. organizing and participating in advocacy activities, such as political discussions, conferences and information workshops; 02. disseminating information related to the Panel and its activities through publications and in the media; providing general research and logistical support to Panel members (WORLD BANK, 2015bWORLD BANK (2015b), The Inspection Panel – Annual report – July 1, 2014-June 30, 2015. Available at ˂http://goo.gl/p1DmC0˃. Accessed on December 18, 2015.

http://goo.gl/p1DmC0...

, p.15).

To be registered, an inspection request must meet the following eligibility criteria: 01. requesters must prove that they live in areas affected by IBRD or IDA Projects or Programs or that they represent affected persons; 02. requesters must allege that there has been social or environmental harm generated by the projects or that they may occur in the future; 03. requesters need to show that the harm generated was due to the violation, by the Bank, of its policies and procedures7

7

On the Bank's safeguard policies, see Bank World, 2012a.

. Requesters do not need to detail the policies violated by the Bank. The Panel will identify those policies if the request meets the eligibility criteria; 04. requesters must finally demonstrate that they have attempted to present their requests to the Bank Management and have not received satisfactory responses (WORLD BANK, 2003WORLD BANK (2003), Responsabilidade e transparência no Banco Mundial – O Painel de Inspeção – 10 anos. Washington: BIRD. 186 pp.., p. 07). In addition to these elements, the request cannot be formulated for a loan that is no longer active. The loan must have less than 95% of the amounts disbursed. Upon receipt of an inspection request, the Panel forwards it to the World Bank Management requesting a response to the requesters. The Management has 21 days to submit a response, and then the Panel makes a review, also within 21 days, in which determines the eligibility of both the requesters and the inspection request. The Panel then submits its Eligibility Report and the recommendation on the investigation to the Board of Executive Directors for approval. If the Board of Executive Directors approves the investigation, the request is admitted and the Panel initiates a full investigation with no time limit. After the Report is submitted by the Panel, the Management has six weeks to present to the Board its recommendations on the subject matter of investigation. It is the responsibility of the Board of Executive Directors to make the final decision on what should be done based on the results of the full investigation and on the Bank Management's recommendations (WORLD BANK, 2009WORLD BANK (2009), Responsabilização no Banco Mundial – O Painel de Inspeção aos 15 anos. Available at ˂http://goo.gl/p1DmC0˃. Accessed on December 18, 2015.

http://goo.gl/p1DmC0...

, pp. 217-218).

In the next two sections, the role of civil society actors in the creation, operation and results of the Inspection Panel over the past 22 years is identified. There are at least two forms of civil society involvement in the Inspection Panel: 01. in the establishment of the Inspection Panel and in its 1996 and 1999 revisions, when advocated against revisions that sought to reduce the Panel's functions; 02. in the functioning of the Panel, particularly at local and national levels, contributing to the formulation of requests for inspection and seeking to influence the Bank's adoption of action plans and/or corrective measures to mitigate the negative social and environmental impacts of Projects financed by the WB. These forms of action will be then examined.

Civil society in the creation and revisions of the Panel

In 1993, the position of the United States, favorable to the Bank's institutional reforms, created conditions for the success of the campaigns carried out by civil society in favor of a greater accountability of this international organization. Endowed with their own interests and autonomy before states and international organizations, civil society actors used the positive environment produced by the United States' position to make their goal of increasing the Bank's accountability. Guimarães (2012)GUIMARÃES, Feliciano de Sá (2012), Os burocratas das organizações financeiras internacionais: um estudo comparado entre o Banco Mundial e o FMI. Rio de Janeiro: FGV Editora. 228 pp.. considers that, internally, the Management's diagnosis showed that the efficiency of the organization's programs would be greater if criticisms and suggestions from the actors of the organized civil society were incorporated8 8 For a more detailed analysis of the relationship between NGOs and the Bank, see Schulte-Schlemmer, 2001; Pereira, 2011 and 2015; and Guimarães, 2012. . At the same time, the more intense pressures of these actors for World Bank reforms in the 1990s led to the adoption of the strategy of incorporating civil society into the organization. The purpose of this strategy, adopted by the Bank's presidency, was not only to listen to the criticism and recommendations of the social actors, but to co-opt them to limit the losses generated by the criticisms to the organization (see PEREIRA, 2015PEREIRA, João Márcio Mendes (2015), Continuidade, ruptura ou reciclagem? Uma análise do programa político do Banco Mundial após o Consenso de Washington. Dados. Vol. 58, Nº 02, pp. 461-498., p. 469). The presidency of James Wolfensohn was able to accomplish this goal, as shown by the analysis of João Márcio Mendes Pereira (2011PEREIRA, João Márcio Mendes (2011), A 'autorreforma' do Banco Mundial durante a gestão Wolfensohn (1995-2005): iniciativas, direção e limites. Tempo. Vol. 17, Nº 31, pp. 177-206., pp. 203-204). For Pereira (2011)PEREIRA, João Márcio Mendes (2011), A 'autorreforma' do Banco Mundial durante a gestão Wolfensohn (1995-2005): iniciativas, direção e limites. Tempo. Vol. 17, Nº 31, pp. 177-206., the need for a revision of the functions of the World Bank and the IMF (International Monetary Fund) was under discussion in the early 1990s. For the Bank's presidency, therefore, it was necessary to ensure the survival of the World Bank Group's own financial institutions amid the White House's and civil society's 'crossfire'.

In addition to this general context, two specific episodes contributed to explaining the origins of the Inspection Panel. The first was the Wapenhans Report (submitted to the Executive Board in November 1992), which revealed, among other things, that 37% of Bank-financed projects were unsatisfactory (UDALL, 1998UDALL, Lori (1998), The World Bank and Public Accountability: Has Anything Changed? In: The struggle for accountability: the World Bank, NGOs, and grassroots movements. Edited by BROWN, L. David and FOX, Jonathan A.. Cambridge: The MIT Press, pp. 391-436., p. 401). The report examined 1,300 ongoing projects in 113 countries and identified poor project quality across all sectors from 1981 to 1991, showing that only 22% of the reviewed projects were in compliance with the World Bank standards (see PEREIRA, 2015PEREIRA, João Márcio Mendes (2015), Continuidade, ruptura ou reciclagem? Uma análise do programa político do Banco Mundial após o Consenso de Washington. Dados. Vol. 58, Nº 02, pp. 461-498., p. 473). The report blamed the so-called 'culture of approval' within the Bank. Since McNamara's Presidency (1968-1981), the staff received career promotions according to the number of loans approved (see SCHULTE-SCHLEMMER, 2001SCHULTE-SCHLEMMER, Sabine (2001), The impact of civil society on the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization: the case of the World Bank. ILSA Journal of International and Comparative Law. Vol. 07, Nº 02, pp. 400-428., p. 416; GUIMARÃES, 2012GUIMARÃES, Feliciano de Sá (2012), Os burocratas das organizações financeiras internacionais: um estudo comparado entre o Banco Mundial e o FMI. Rio de Janeiro: FGV Editora. 228 pp.., p. 86). The Wapenhans Report generated an action plan prepared by the Management in July 1993, in which increasing civil society participation in project design and implementation was recommended (SCHULTE-SCHLEMMER, 2001SCHULTE-SCHLEMMER, Sabine (2001), The impact of civil society on the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization: the case of the World Bank. ILSA Journal of International and Comparative Law. Vol. 07, Nº 02, pp. 400-428., pp. 412-413). This plan also recommended the Bank's need to adopt a reliable independent judgment mechanism on specific operations - such as an inspection panel - as they could lead to implementation problems (SCHULTE-SCHLEMMER, 2001SCHULTE-SCHLEMMER, Sabine (2001), The impact of civil society on the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization: the case of the World Bank. ILSA Journal of International and Comparative Law. Vol. 07, Nº 02, pp. 400-428., p. 413).

The second episode refers to the investigations on the Narmada project (Sardar Sarovar Dam and Power Project), in West India. The civil society campaign around this project contributed to the creation of the Morse Commission, which strongly criticized the Bank's performance in the areas of environment and resettlement of populations displaced by the construction of energy projects (UDALL, 1998UDALL, Lori (1998), The World Bank and Public Accountability: Has Anything Changed? In: The struggle for accountability: the World Bank, NGOs, and grassroots movements. Edited by BROWN, L. David and FOX, Jonathan A.. Cambridge: The MIT Press, pp. 391-436., p. 394). For Lori Udall (1998UDALL, Lori (1998), The World Bank and Public Accountability: Has Anything Changed? In: The struggle for accountability: the World Bank, NGOs, and grassroots movements. Edited by BROWN, L. David and FOX, Jonathan A.. Cambridge: The MIT Press, pp. 391-436., p. 394), the Narmada project was the catalyst for the creation of the Inspection Panel. In addition, the report revealed the Bank's difficulties in involving local communities in the process of economic development and in hearing their requests (UDALL, 1998)UDALL, Lori (1998), The World Bank and Public Accountability: Has Anything Changed? In: The struggle for accountability: the World Bank, NGOs, and grassroots movements. Edited by BROWN, L. David and FOX, Jonathan A.. Cambridge: The MIT Press, pp. 391-436.. As the Bank did not pay attention to the conclusions of the Report and did not suspend the transfer of funding to the project, the mobilization of NGOs based in Washington played an important role, as they articulated some initiatives within the US Congress to demand greater accountability from the Bank. To this end, they had the support of American Congressman Barney Frank (Democratic Party), chair of the Subcommittee on Development, Finance, Trade and Monetary Policy, and of Sydney Key (Academic), who ran the staff of this Subcommittee. Both were particularly receptive to the model of an Inspection Panel submitted by two Washington-based NGOs: the 'Environmental Defense Fund' and the 'Center for International Environmental Law'. This proposal envisioned the creation of a permanent three-member body to conduct the investigations of the requesters, with an independent budget for its activities and for providing the conditions so the team could travel to the places where the investigations would be carried out (CLARK, 2003CLARK, Dana (2003), Understanding the World Bank Inspection Panel. In: Demanding accountability: civil society claims and the World Bank Inspection Panel. Edited by CLARK, Dana; FOX, Jonathan, and TREAKLE, Kay. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 01-24., p. 07). The Inspection Panel was created at the same time that the US Congress approved the replenishment of IDA, with the proviso of continuing to follow the results of the Bank-approved reforms.

The pressure from NGOs was made effective by IDA's reliance on replenishment. IDA has three sources of funding, according to João Márcio Mendes Pereira (2011PEREIRA, João Márcio Mendes (2011), A 'autorreforma' do Banco Mundial durante a gestão Wolfensohn (1995-2005): iniciativas, direção e limites. Tempo. Vol. 17, Nº 31, pp. 177-206., p. 185)9 9 See footnote 27 in Pereira (2011). : voluntary donations from richer member countries, repayment of credits provided to borrowers and transferences from IBRD and IFC. Voluntary donations from countries such as the United States are IDA's main source of funds. These donations are made every three years through negotiated replenishments among 30 donor countries. The United States, the main donor, approves its contribution to IDA annually. Therefore, the US Congress was used as an important space for pressure from Washington-based NGOs.

It is also possible to identify the performance of civil society in the Inspection Panel revisions10 10 The full text of the Panel Revisions is available in World Bank, 2009: Appendices VII and VIII. . The first revision was made in 1996 and was already foreseen in the Panel's Rules of Procedure. NGOs and academics were able to send suggestions, including the possibility for international and local NGOs to submit requests for inspection, even if they were not representing rights or interests of affected people. Requests for inspection would be made in the name of the general interest. This suggestion was not accepted by the Management. The main revision carried out in 1996 was related to the Panel's ability to conduct a preliminary assessment of the alleged harm in the inspection request to ascertain whether there has been a violation of the Bank's policies and whether a full investigation would be required.

The second revision was carried out in 1999 based on the efforts of a working group set up by the Bank's Executive Board. This group was supposed to present a proposal without the participation of actors outside the Bank, such as NGOs. Criticism of this methodology led the Executive Board to invite academics and NGO representatives to comment on the proposal and to participate in an open discussion with members of the Board (SCHULTE-SCHLEMMER, 2001SCHULTE-SCHLEMMER, Sabine (2001), The impact of civil society on the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization: the case of the World Bank. ILSA Journal of International and Comparative Law. Vol. 07, Nº 02, pp. 400-428., pp. 416-417). In this way, civil society was given space to follow the Panel revision process, presenting proposals that would be approved by the Executive Board. The most important one, passed in 1999, established that if the Panel recommended an investigation, the Board should authorize the initiation of such an investigation, unless the request for inspection would not meet the eligibility criteria. This amendment addressed the interests of civil society, which recommended the need for full Panel investigations that would serve as a basis for the Management to present an Action Plan. The Board should therefore rely on the Panel's recommendations, which would define the admissibility of requests (SCHULTE-SCHLEMMER, 2001SCHULTE-SCHLEMMER, Sabine (2001), The impact of civil society on the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization: the case of the World Bank. ILSA Journal of International and Comparative Law. Vol. 07, Nº 02, pp. 400-428., pp. 416-417). This revision strengthened the Panel by making it responsible for recommending or not the initiation of full and detailed investigations.

In short, civil society actors played an important role in the Panel's creation and, particularly, in its second revision in 1999. They contributed to strengthening the role of the Panel in 1999 and to sustaining the need for full investigations whose purpose would be to reveal problems of compliance. In the next section, how civil society operates in the functioning of the Panel is examined.

Civil society in the functioning of the Inspection Panel

The Inspection Panel is seen as a mechanism to give voice to local communities and to citizens located, especially, in developing countries, affected by environmental and social impacts generated by the Bank-financed projects (BARLAS and TASSONI, 2015BARLAS, Dilek e TASSONI, Tatiana (2015), Improving service delivery through voice and accountability: the experience of the World Bank Inspection Panel. In: Improving delivery in development: the role of voice, social contract, and accountability. Edited by WOUTERS, Jan; NINIO, Alberto; DOHERTY, Teresa, and CISSÉ, Hassane. Washington: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. pp. 475-493.; BARROS, 2001BARROS, Flavia Lessa de (2001), Bancando o desafio: para 'inspecionar' o Painel de inspeção do Banco Mundial. In: Banco Mundial, participação, transparência e responsabilização. Edited by BARROS, Flavia Lessa de. Brasília: Rede Brasil sobre Instituições Financeiras Multilaterais. pp. 15-34.; BUNTAINE, 2015BUNTAINE, Mark T. (2015), Accountability in global governance: civil society claims for environmental performance at the World Bank. International Studies Quarterly. Vol. 59, pp. 99–111.; CLARK, 2003CLARK, Dana (2003), Understanding the World Bank Inspection Panel. In: Demanding accountability: civil society claims and the World Bank Inspection Panel. Edited by CLARK, Dana; FOX, Jonathan, and TREAKLE, Kay. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 01-24.; EBRAHIM and HERZ, 2007EBRAHIM, Alnoor and HERZ, Steve (2007), Accountability in complex organizations: World Bank responses to civil society. Working Paper. HBS Working Paper, October.; LUKAS, 2015LUKAS, Karin (2015), The Inspection Panel of The World Bank: an effective extrajudicial complaint mechanism? In: Improving delivery in development: the role of voice, social contract, and accountability. Edited by WOUTERS, Jan; NINIO, Alberto; DOHERTY, Teresa, and CISSÉ, Hassane. Washington: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. pp. 531-544.; NIELSON and TIERNEY, 2003Nielson, Daniel and Tierney, Michael (2003), Delegation to international organizations: agency theory and World Bank environmental reform. International Organization. Vol. 57, Nº 02, pp. 241-276.; WONG and MAYER, 2015WONG, Yvonne e MAYER, Benoit (2015), The World Bank's Inspection Panel: a tool for accountability? In: Improving delivery in development: the role of voice, social contract, and accountability. Edited by WOUTERS, Jan; NINIO, Alberto; DOHERTY, Teresa, and CISSÉ, Hassane. Washington: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. pp. 495-530.).

Nevertheless, the lack of information from the local population and the technical nature of the process lead the requesters to seek the assistance of experts, such as lawyers, and even specialists from civil society (TREAKLE, FOX and CLARK, 2003Treakle, Kay; FOX, Jonathan, and CLARK, Dana (2003), Lessons learned. In: Demanding accountability: civil society claims and the World Bank Inspection Panel. Edited by CLARK, Dana; FOX, Jonathan, and TREAKLE, Kay. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 247-278., p. 266,. The drafting of a request is not a simple task, since it requires determining whether there has been a violation of the Bank policies. To do this, one needs to understand what they are and how to contact the Inspection Panel. The problem of the lack of knowledge about the existence of this mechanism of accountability and how to use it is also pointed out in the World Bank documents (WORLD BANK, 2009WORLD BANK (2009), Responsabilização no Banco Mundial – O Painel de Inspeção aos 15 anos. Available at ˂http://goo.gl/p1DmC0˃. Accessed on December 18, 2015.

http://goo.gl/p1DmC0...

; WORLD BANK/CAO/MIGA/IFC, 2015WORLD BANK/CAO/MIGA/IFC (2015), Civil society engagement with the independent accountability mechanisms: analysis of environmental and social issues and trends. Available at ˂http://goo.gl/p1DmC0˃. Accessed on December 18, 2015.

http://goo.gl/p1DmC0...

). In addition to the efforts of the Panel itself, civil society actors seek to make this mechanism and its operation more accessible to affected people by helping to make it known and, at the same time by: 01. assisting in the elaboration of the request; 02. liaising with Panel members who will conduct on-site investigations; 03. facilitating the transparency of the Panel through pressure to disseminate the documents and the results of the investigations; 04. exercising wide publicity and campaign in the media to denounce the Bank's failures and demanding measures to repair the environmental and social harm generated by the projects.

Civil society actors thus contribute to the functioning of the Bank's main horizontal accountability mechanism11

11

The Inspection Panel can be characterized as a horizontal accountability mechanism of the World Bank, as Woods and Narlikar (2001, p. 576) argue, because it was created to be independent and with monitoring functions of IBRD and IDA. These functions approximate the horizontal accountability agencies mentioned by G. O'Donnell (1998).

. Data on participation and direct involvement of civil society in the Inspection Panel are revealing of the role of these actors, particularly NGOs, civil and community associations and individuals. According to data from the Panel's website12

12

See http://goo.gl/3abpKh.

, from 1994 (year in which the first request for inspection was made) to June 2015, the Panel received 103 requests for inspection (see WORLD BANK, Panel Cases, 2015aWORLD BANK (2015a), Panel cases. The Inspection Panel. Available at ˂http://goo.gl/3abpKh˃. Accessed on July 20, 2015.

http://goo.gl/3abpKh...

). For the purpose of identifying the presence of civil society in these requests, all cases available on the Panel's website will be considered until June 2015, when the period for the Panel's annual report (from July 2014 to June 2015) was closed (see WORLD BANK, 2015bWORLD BANK (2015b), The Inspection Panel – Annual report – July 1, 2014-June 30, 2015. Available at ˂http://goo.gl/p1DmC0˃. Accessed on December 18, 2015.

http://goo.gl/p1DmC0...

). Some requests refer to the same project. This is the case of projects in Panama, India, Albania, Argentina and Brazil, which received two inspection requests. The same project in India received three requests. The Panel treats each separately. For this reason, the authors have chosen to consider them individually. Data for the 103 cases were tabulated in a database whose construction was guided by a set of variables, described in Table 01 below. From this set of variables, crosses and analyses were performed in addition to the descriptive statistics, which were corroborated by the argument of this article.

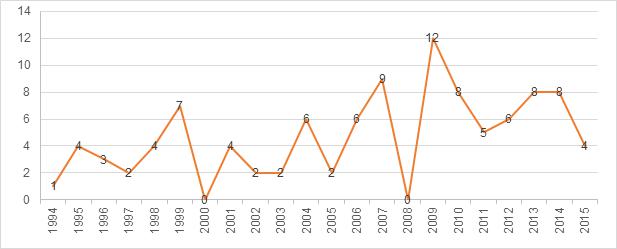

Graph 01 below shows the evolution of the number of inspection requests submitted per year (N = 103). There is a slight increase in the number of requests in the period 2009 to 2015. Data show an average of 7.2 requests per year for this particular period in contrast to the overall Panel average of 4.6. However, the number of cases presents a very uneven distribution throughout the period considered in this research (1994 to June 2015).

Of the 103 requests considered here, 102 were submitted by civil society actors (requesters). These actors include: 01. local and national NGOs; 02. civil and community associations; and 03. individuals, such as local residents and representatives of the interests of the populations affected by the projects. One case was filed by a private company and was rejected by the Panel. For the purposes of this analysis, we classified actors in three main types: 01. company; 02. individuals; 03. civil society organizations. It is also important to note that most requests, formulated with the participation of civil society organizations, involve local actors and grassroots movements. Table 02 below summarizes the information on the types of requesters.

With regard to the admissibility of requests, it can be seen on Graph 02 that 59 cases (or 57% of the total) were admitted by the Panel or generated revisions by the Bank's Management. The remaining requests were not registered or admitted for investigation (44 cases or 43% of the total). Admissibility is understood here as: 01. cases that have generated detailed investigation by Panel members; and 02. requests that led the Bank to propose revisions to the projects before authorizing full investigations. The practice of proposing action plans prior to the investigation was more frequent prior to the Panel's second revision, but was only completely removed by the Bank's Management after 1999. These requests could be included among the admitted cases, as the Management acknowledged the need for: 01. proposing revisions in the projects prior to the full investigation; or 02. canceling funding for compliance problems (as in case 01, for example). This datum shows how civil society acted with the purpose of contributing to force the Bank to investigate or adopt revisions in the projects. It also reveals how the Bank proved to be permeable to requesters. Graph 02 summarizes data on the admissibility of requests.

Regarding the results obtained by the requesters, it is possible to note that, in 52% of the 103 cases, the World Bank accepted to adopt action plans and/or corrective measures. Graph 03 summarizes this information. Among these measures, some examples can be cited: 01. improvement of consultation processes with local communities; 02. implementation of new programs and resources to benefit or compensate affected persons; 03. monitoring of social and environmental impacts; among others. As it might be expected, requests recently made are still under consideration by the Panel.

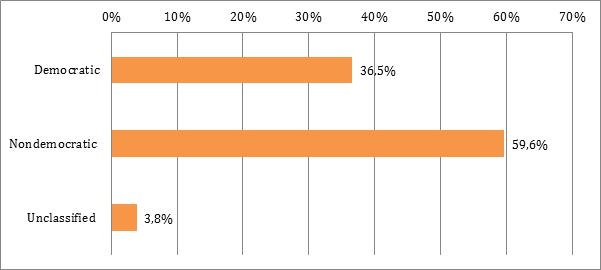

Most requests come from developing countries, located in Asia, Africa and Latin America. The political regimes of these countries are varied. In order to assess the national conditions in which requests are made, it is possible to use the Democracy Index 2015 of 'The Economist', which classified countries according to four types of political regimes, namely: 01. Full democracy; 02. Flawed democracy; 03. Hybrid regime; 04. Authoritarian. We decided to reduce this classification to a binary categorization: 01. Democratic Regime (Full Democracy + Flawed Democracy); and 02. Non-Democratic (Hybrid Regime + Authoritarian). Some requests are issued by local actors located in more than one country and refer to the same project. Among the five cases that fall into this situation, actors are from either democratic or non-democratic countries. These cases were considered as unclassified political regime. Graph 04 below summarizes the political regimes in which the civil society actors responsible for formulating the requests are located.

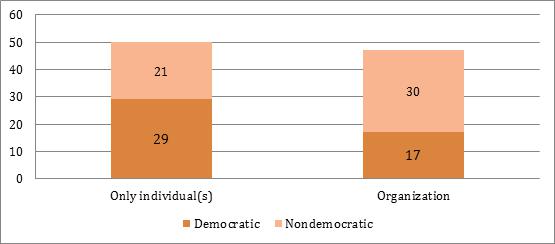

We also observed the extent to which political regimes interfere with the role of civil society in the formulation of requests. Graph 05, then, displays information on the intersection between political regimes and the type of request. Only cases in which the political regime could be classified were considered (98). The only case issued by a company was excluded because the objective was to evaluate the association between the political regime and the performance of civil society in the formulation of requests (N = 97).

As can be seen in Graph 05 above, actors from the so-called organized civil society (such as NGOs and civil and community associations) predominate in cases coming from undemocratic countries. Requests made by individuals or groups of individuals prevail in democratic countries. These data reveal that organized civil society is more active in contexts of authoritarianism, in which the local population is afraid to make requests. Authoritarian contexts can affect the type of requester as individuals fear reprisals from governments and companies operating in their country. This is the case, for example, with a request for inspection by an international NGO representing the local population of China (TREAKE, FOX and CLARK, 2003Treakle, Kay; FOX, Jonathan, and CLARK, Dana (2003), Lessons learned. In: Demanding accountability: civil society claims and the World Bank Inspection Panel. Edited by CLARK, Dana; FOX, Jonathan, and TREAKLE, Kay. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 247-278., p. 251). In order to avoid retaliation, people affected by the projects ask for their anonymity in the majority of cases or prefer the petition to be presented on their behalf by organized civil society actors. This datum shows that organized civil society contributes to monitor Bank-financed projects, especially in authoritarian contexts, where organized civil society acts with less risk of retaliation.

The information and data presented above show how civil society actions contributed to the operation (formulation of requests) and the results achieved by the Panel (initiation of investigation, adoption of action plans and/or corrective measures). These actions sought, among other objectives, to prevent the Panel from discharging its main investigative functions, collecting data and presenting recommendations for correcting Bank failures. The contributions of civil society have achieved mixed results. This article did not attempt to qualitatively evaluate the results achieved by the Inspection Panel, examining the content of each action plan, corrective action and revision, but to note that to some extent, the Inspection Panel has generated action plans, corrective measures and revisions with the participation of civil society. This reveals that the Panel worked, to some extent, within the limits imposed to a horizontal accountability mechanism of an international organization. Among these limits, it is necessary to consider: 01. the gap between the World Bank and citizens affected by projects funded by this organization; and 02. the imbalances in the distribution of power of international politics that generate reflexes on the decision-making process of the IOs and, consequently, interfere in the functioning of the mechanisms of accountability of these organizations.

The gap between the Bank and national citizens tends to generate the accountability deficit pointed out by David Held (2004)HELD, David (2004), Democratic accountability and political effectiveness from a cosmopolitan perspective. Government and Opposition. Vol. 39, Nº 02, pp. 364-391.. This deficit is partly offset by actions by civil society capable of establishing mediations between the citizens, the Bank, the Member States and those responsible for the decision-making of that organization. These mediations can be observed: 01. in the activities of international NGOs in Washington; and 02. in the requests submitted to the Inspection Panel, in which civil society was present, as can be seen from the data presented above. For Brown and Fox (1998bBROWN, L. David and FOX, Jonathan (1998b), Assessing the impact of NGO advocacy campaigns on World Bank. In: The struggle for accountability: the World Bank, NGOs, and grassroots movements. Edited by BROWN, L. David and FOX, Jonathan A.. Cambridge: The MIT Press. pp. 485-551., p. 529), the pressure exerted by civil society actors can deliver results in accordance with their ability to overcome the resistance imposed by the Executive Board, which has fundamental decision-making capacity and represents national governments. The World Bank, like other IOs, tends to be accountable to the Member States, as noted by Woods and Narlikar (2001WOODS, Ngaire e NARLIKAR, Amrika (2001), Governance and the accountability: the WTO, the IMF, and the World Bank. International Social Science Journal. Vol. 53, Nº 170, pp. 569-583., pp. 572-573). Civil society seeks, however, to influence the behavior of States and make them sensitive to the demands of greater accountability. Of course, the results of the action of civil society depend on existing political regimes. However, even in countries governed by authoritarian regimes it is possible to identify the presence of social actors in the formulation of requests to the Panel, as was shown in Graph 05. Civil society's role in monitoring is essential to inform states about the performance of IOs and to keep them more accountable for their actions. In this way, the most powerful states will have the elements to impose sanctions on organizations (such as suspending on lending) and to ensure that the actions they take fail to produce negative social and environmental impacts (BUNTAINE, 2015BUNTAINE, Mark T. (2015), Accountability in global governance: civil society claims for environmental performance at the World Bank. International Studies Quarterly. Vol. 59, pp. 99–111., p. 100).

Civil society therefore has three lines of action: 01. it exerts pressure on the decision-making process of the IOs to create and maintain accountability mechanisms; 02. it pressures national states, especially the most powerful, to lead them to recognize and validate such mechanisms. This is what occurred in the Inspection Panel's creation and revisions, as shown in this article; finally, 03. civil society pressures the national governments of countries where there are Bank-financed projects and whose undesirable social and environmental impacts, when occur, need to be reported. Civil society actors contribute to the functioning of the Panel, seeking to influence the behavior of the Bank and take it to the adoption of revisions in the projects with the purpose of minimizing negative social and environmental impacts.

Considering the three lines of action listed above, studies on accountability in international politics cannot disregard the role of civil society in the functioning of accountability mechanisms of international organizations. In these studies, the concept of social accountability is adequate to the development of empirical studies.

Final considerations

The concept of social accountability was designed to examine accountability, especially in those democratic experiences where traditional accountability mechanisms fail or prove to be insufficient. This is what O'Donnell (1998O'DONNELL, Guillermo (1998), Accountability horizontal e novas poliarquias. Lua Nova. Nº 44, pp. 27-54., p. 28) observed when examining the countries which, according to him, had 'weak or intermittent' horizontal accountability. To a certain extent, international politics is similar to the reality of democracies in these countries (part of them located in Latin America). The democratic experiences of these countries allow us to assess the problems and limits of accountability in international politics. For Dahl (1994Dahl, Robert (1994), A democratic dilemma: system effectiveness versus citizen participation. Political Science Quarterly. Vol. 109, Nº 01, pp. 23-34., 1999DAHL, Robert (1999), Can international organizations be democratic? A skeptic's view. In: Democracy's edges. Edited by SHAPIRO, Ian and HACKER-CORDÓN, Casiano. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 19-36.), democracy is unlikely present at the international level. His 'skepticism' was expressed in his 1994 article when he examined the supranational political institutions of the European integration process, stating, in a nutshell, that there is no possibility of democracy outside nation-states. The authors of the concept of social accountability presented an alternative to the functioning of accountability in the democracies of Latin America by highlighting the role of civil society and the media in the operation of accountability mechanisms. It is plausible to transpose this analysis to international politics for two main reasons, among others: 01. because of the significant expansion of social actors in international politics, which seek to increase their influence in various themes and in various power spaces, such as IOs (NYE and KEOHANE, 1971NYE Jr., Joseph and KEOHANE, Robert (1971), Transnational relations and world politics: an introduction. International Organization. Vol. 25, Nº 03, pp. 329-349.; MERLE, 1981)MERLE, Marcel (1981), Sociologia das relações internacionais. Brasília: Editora Universidade de Brasília. 384 pp... They are actors with their own interests and resources that seek to influence the decision-making processes in national states and IOs; 02. because of the possibility of these actors to contribute to attenuate (but not eliminate) the democratic deficit (MORAVSCIK, 2004)MORAVSCIK, Andrew (2004), Is there a 'democratic deficit' in world politics? A framework for analysis. Government and Opposition. Vol. 39, Nº 02, pp. 336-363. of international politics, considering the practical difficulties to operationalize accountability.

In concrete terms, the experience of the Inspection Panel has shown that social actors contribute to the functioning of one of the main mechanisms of accountability of IOs. This experience shows the possibility of transposing to international politics the argument used by Peruzzotti and Smulovitz (2002PERUZZOTTI, Enrique and SMULOVITZ, Catalina (2002), Controlando la política: ciudadanos y medios en las democracias Latinoamericanas. Edited by PERUZZOTTI, Enrique and SMULOVITZ, Catalina. Buenos Aires: Grupo Editorial Temas. 325 pp.., 2006PERUZZOTTI, Enrique and SMULOVITZ, Catalina (2006), Enforcing the rule of law: social accountability in the new Latin American democracies. Edited by PERUZZOTTI, Enrique and SMULOVITZ, Catalina. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. 362 pp..) to highlight the importance of social accountability. In other words, Peruzzotti and Smulovitz (2006)PERUZZOTTI, Enrique and SMULOVITZ, Catalina (2006), Enforcing the rule of law: social accountability in the new Latin American democracies. Edited by PERUZZOTTI, Enrique and SMULOVITZ, Catalina. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. 362 pp.. and O'Donnell (2006)O’DONNELL, Guillermo (2006), Notes on various accountabilities and their interrelations. In: Enforcing the rule of law: social accountability in the new Latin American democracies. Edited by PERUZZOTTI, Enrique and SMULOVITZ, Catalina. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 334-343. consider the social dimension articulated with the horizontal dimension of accountability, as the actions of civil society actors can put into operation horizontal accountability agencies. This was observed in the experience of the Inspection Panel, in which civil society actors contribute to compensate for the limitations of the WB's horizontal accountability mechanisms by monitoring the behavior of states and the Bank itself. For the above reasons, it is pertinent to think of the use of the concept of Peruzzotti and Smulovitz (2002PERUZZOTTI, Enrique and SMULOVITZ, Catalina (2002), Controlando la política: ciudadanos y medios en las democracias Latinoamericanas. Edited by PERUZZOTTI, Enrique and SMULOVITZ, Catalina. Buenos Aires: Grupo Editorial Temas. 325 pp.., 2006PERUZZOTTI, Enrique and SMULOVITZ, Catalina (2006), Enforcing the rule of law: social accountability in the new Latin American democracies. Edited by PERUZZOTTI, Enrique and SMULOVITZ, Catalina. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. 362 pp..) to analyze other mechanisms of horizontal accountability, created and maintained by international organizations.

In summary, this article started from the recognition of the theoretical difficulties to operationalize the accountability in international organizations and to interpret it analytically. It also defended the use of the concept of social accountability for the development of new empirical studies. It would be pertinent, then, to examine other mechanisms of accountability of international organizations to identify the modalities of civil society performance in each of them. Studying these modalities can provide clues to qualify the participation of civil society in these mechanisms. This task may inspire future research based on the concept of social accountability applied to the study of attempts at democratization of international organizations.

References

- BARLAS, Dilek e TASSONI, Tatiana (2015), Improving service delivery through voice and accountability: the experience of the World Bank Inspection Panel. In: Improving delivery in development: the role of voice, social contract, and accountability. Edited by WOUTERS, Jan; NINIO, Alberto; DOHERTY, Teresa, and CISSÉ, Hassane. Washington: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. pp. 475-493.

- BARROS, Flavia Lessa de (2001), Bancando o desafio: para 'inspecionar' o Painel de inspeção do Banco Mundial. In: Banco Mundial, participação, transparência e responsabilização Edited by BARROS, Flavia Lessa de. Brasília: Rede Brasil sobre Instituições Financeiras Multilaterais. pp. 15-34.

- BROWN, L. David and FOX, Jonathan A. (1998a), Accountability within transnational coalitions. In: The struggle for accountability: the World Bank, NGOs, and grassroots movements. Edited by BROWN, L. David and FOX, Jonathan A.. Cambridge: The MIT Press. pp. 439-483.

- BROWN, L. David and FOX, Jonathan (1998b), Assessing the impact of NGO advocacy campaigns on World Bank. In: The struggle for accountability: the World Bank, NGOs, and grassroots movements. Edited by BROWN, L. David and FOX, Jonathan A.. Cambridge: The MIT Press. pp. 485-551.

- BUCHANAN, Allen and KEOHANE, Robert O. (2006), The legitimacy of global governance institutions. Ethics & International Affairs Vol. 20, Nº 04, pp. 405-437.

- BUNTAINE, Mark T. (2015), Accountability in global governance: civil society claims for environmental performance at the World Bank. International Studies Quarterly Vol. 59, pp. 99–111.

- CLARK, Dana (2003), Understanding the World Bank Inspection Panel. In: Demanding accountability: civil society claims and the World Bank Inspection Panel. Edited by CLARK, Dana; FOX, Jonathan, and TREAKLE, Kay. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 01-24.

- COHEN, Jean L. and ARATO, Andrew (1994), Civil society and political theory Cambridge: MIT Press. 800 pp..

- Dahl, Robert (1994), A democratic dilemma: system effectiveness versus citizen participation. Political Science Quarterly Vol. 109, Nº 01, pp. 23-34.

- DAHL, Robert (1999), Can international organizations be democratic? A skeptic's view. In: Democracy's edges Edited by SHAPIRO, Ian and HACKER-CORDÓN, Casiano. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 19-36.

- EBRAHIM, Alnoor and HERZ, Steve (2007), Accountability in complex organizations: World Bank responses to civil society. Working Paper HBS Working Paper, October.

- FEREJOHN, John (1999), Accountability and authority: toward a theory of political accountability. In: Democracy, accountability, and representation Edited by PRZEWORSKI, Adam; STOKES, Suzan C., and MANIN, Bernard. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 131-153.

- FOX, Jonathan (2000), Civil society and political accountability: propositions for discussion. Paper Presented at Institutions, accountability and democratic governance in Latin America. The Helen Kellogg Institute for International Studies. University of Notre Dame.

- FOX, Jonathan (2007), The uncertain relationship between transparency and accountability. Development in Practice Vol. 17, Nº 04–05, pp. 663-671.

- GOHN, Maria da Glória (2014), A sociedade brasileira em movimento: vozes das ruas e seus ecos políticos e sociais. Cadernos CRH Vol. 27, Nº 71, pp. 431-441.

- GRANT, Ruth W. and KEOHANE, Robert (2005), Accountability and abuses of power in world politics. The American Political Science Review Vol. 99, Nº 01, pp. 29-44.

- GUIMARÃES, Feliciano de Sá (2012), Os burocratas das organizações financeiras internacionais: um estudo comparado entre o Banco Mundial e o FMI. Rio de Janeiro: FGV Editora. 228 pp..

- HELD, David (2004), Democratic accountability and political effectiveness from a cosmopolitan perspective. Government and Opposition Vol. 39, Nº 02, pp. 364-391.

- HOLLYER, James R.; ROSENDORFF, B. Peter, and VREELAND, James Raymond (2011), Democracy and transparency. Journal of Politics Vol. 73, Nº 04, pp. 1191-1205.

- KEOHANE, Robert O. (2003), Global governance and democratic accountability. In: Taming globalization: frontiers of governance. Edited by HELD, David e KOENIG-ARCHIBUGI, Mathias. Cambridge: Polity Press. pp. 130-159.

- KEOHANE, Robert O. (2006), Accountability in world politics. Scandinavian Political Studies Vol. 29, Nº 02, pp. 75-87.

- KEOHANE, Robert O. (2011), Global governance and legitimacy. Review of International Political Economy Vol. 18, Nº 01, pp. 99–109.

- KEOHANE, Robert O. and NYE, Joseph S. (2003), Redefining accountability for global governance. In: Governance in a global economy: political authority in transition. Edited by KAHLER, Miles and LAKE, David. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 386-411.

- KEOHANE, Robert; MACEDO, Stephen, and MORAVCSIK, Andrew (2009), Democracy-enhancing multilateralism. International Organization, Vol. 63, Nº 01, pp. 01-31.

- LAVALLE, Adrián G.; CASTELLO, Graziela, and BICHIR, Renata M. (2004), Quando novos atores saem de cena: continuidades e mudanças na centralidade dos movimentos sociais. Política & Sociedade Vol. 03, Nº 05, pp. 35-53.

- LUKAS, Karin (2015), The Inspection Panel of The World Bank: an effective extrajudicial complaint mechanism? In: Improving delivery in development: the role of voice, social contract, and accountability. Edited by WOUTERS, Jan; NINIO, Alberto; DOHERTY, Teresa, and CISSÉ, Hassane. Washington: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. pp. 531-544.

- MAIA, Rouseley C. M. (2006), Mídia e diferentes dimensões da accountability. E-Compós Vol. 07, pp. 02-27.

- MARAVALL, José Maria (1999), Accountability and manipulation. In: Democracy, accountability, and representation Edited by PRZEWORSKI, Adam; STOKES, Suzan C., and MANIN, Bernard. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 154-196.

- MERLE, Marcel (1981), Sociologia das relações internacionais Brasília: Editora Universidade de Brasília. 384 pp..

- MORAVSCIK, Andrew (2004), Is there a 'democratic deficit' in world politics? A framework for analysis. Government and Opposition Vol. 39, Nº 02, pp. 336-363.

- Nielson, Daniel and Tierney, Michael (2003), Delegation to international organizations: agency theory and World Bank environmental reform. International Organization Vol. 57, Nº 02, pp. 241-276.

- NYE Jr., Joseph (2001), Globalization's democratic deficit: how to make international institutions more accountable. Foreign Affairs Vol. 80, Nº 04. pp. 431-435.

- NYE Jr., Joseph and KEOHANE, Robert (1971), Transnational relations and world politics: an introduction. International Organization Vol. 25, Nº 03, pp. 329-349.

- O'DONNELL, Guillermo (1998), Accountability horizontal e novas poliarquias. Lua Nova Nº 44, pp. 27-54.

- O’DONNELL, Guillermo (2000), Further thoughts on Horizontal Accountability. In: Workshop on “Institutions, Accountability, and Democratic Governance in Latin America”. Notre Dame: Kellogg Institute for International Studies/University of Notre Dame, May 8-9. Draft.

- O’DONNELL, Guillermo (2006), Notes on various accountabilities and their interrelations. In: Enforcing the rule of law: social accountability in the new Latin American democracies. Edited by PERUZZOTTI, Enrique and SMULOVITZ, Catalina. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 334-343.

- PEREIRA, João Márcio Mendes (2011), A 'autorreforma' do Banco Mundial durante a gestão Wolfensohn (1995-2005): iniciativas, direção e limites. Tempo Vol. 17, Nº 31, pp. 177-206.

- PEREIRA, João Márcio Mendes (2014), As ideias do poder e o poder das ideias: o Banco Mundial como ator político-intelectual. Revista Brasileira de Educação Vol. 19, Nº 56, pp. 77-100.

- PEREIRA, João Márcio Mendes (2015), Continuidade, ruptura ou reciclagem? Uma análise do programa político do Banco Mundial após o Consenso de Washington. Dados Vol. 58, Nº 02, pp. 461-498.

- PERUZZOTTI, Enrique and SMULOVITZ, Catalina (2002), Controlando la política: ciudadanos y medios en las democracias Latinoamericanas. Edited by PERUZZOTTI, Enrique and SMULOVITZ, Catalina. Buenos Aires: Grupo Editorial Temas. 325 pp..

- PERUZZOTTI, Enrique and SMULOVITZ, Catalina (2006), Enforcing the rule of law: social accountability in the new Latin American democracies. Edited by PERUZZOTTI, Enrique and SMULOVITZ, Catalina. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. 362 pp..