Abstract

Analysts frequently label the BRICS grouping of states (Brazil, India, Russia, China, and South Africa) as primarily an economic club emphasising economic performances as primary objectives. Co-operation of international groupings are rarely, if ever, set within the context of their access to maritime interests, security, and benefits. A second void stems from the lack of emphasis upon the economic benefits of secured maritime domains. In this vein, a common, but neglected aspect of the BRICS grouping’s power and future influence resides in their maritime domains, the value of which ultimately depends upon the responsible governance and use of ocean territories. The maritime interests of BRICS countries only become meaningful if reinforced by maritime security governance and co-operation in the respective oceans. Presently China and India seem to dominate the maritime stage of BRICS, but the South Atlantic is an often overlooked space. For BRICS the value of the South Atlantic stems from how it secures and unlocks the potential of this maritime space through co-operative ventures between Brazil, South Africa as a late BRICS partner, and West African littoral states in particular. Unfortunately, BRICS holds its own maritime tensions, as member countries also pursue competing interests at sea.

Keywords

Africa; Brazil; BRICS; Maritime Security; South Atlantic; South Africa

Introduction

Contemporary maritime thought prioritises matters that underpin the use of the oceans in more constructive ways, underlines the importance of co-operation, and manages the oceans in a way that promotes sustainability (Petrachenko 2012Petrachenko, Donna. 2012. ‘Australia’s approach to the conservation and sustainable use of marine eco systems’. Australian Journal of Marine and Ocean Affairs, 4(3): 74–76.: 74). It is against this backdrop that BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) evolved in 2010 to BRICS (to include South Africa), and while the continental or landward profile of BRICS caught much of the attention, the five-nation grouping also comprised a noteworthy maritime domain (Onyekwena, Taiwo and Uneze 2014Onyekwena, Chukwuka, Olumide Taiwo and Eberechukwu Uneze. 2014. ‘South Africa in BRICS: A bilateral trade analysis’. Occasional Paper 181, South African Institute for International Affairs. April.: 6). The oceanic tie draws increasing attention from a range of actors, as they realise that ocean wealth is becoming central to what is traditionally exploited on land. When the economic value, which is calculated to be as high as USD 24 trillion – equal to the seventh largest economy on earth – is integrated with the value of the oceans, a potential arises that state and other actors can no longer neglect (World Wildlife Forum 2015World Wildlife Forum. 2015. Reviving the Ocean Economy. The case for action 2015. World Wildlife Forum Report.: 7).

A maritime BRICS receives scant attention in the literature and narratives that depict the general BRICS agenda. Whether as a central or a secondary focus in BRICS debates, the maritime theme remains low-key. This article therefore attempts to highlight the maritime province of BRICS as a neglected field by emphasising its geographic expanse, its maritime security concerns, and the overlooked importance of the South Atlantic Ocean. The aim is to draw attention to a domain of BRICS that holds some promise for its emergent role and influence, in the South Atlantic in particular. This account offers four discussion themes on the maritime domain of BRICS. First, some thought is given to the BRICS agenda in light of arguments attempting to map out its role as an international grouping. Secondly, the BRICS-maritime nexus is explored to frame the scope of its maritime landscapes. Thirdly, some views on contemporary maritime security and followed fourthly, by the overlooked South Atlantic dimension of BRICS and its advantages on offer. The article concludes with some elements of critique stances before offering a brief summary of the discussion.

Perspectives on the BRICS agenda

Reviews of BRICS offer insight on an international entity with political and economic influence that represents a normative alternative to the dynamics upholding the international political and economic order. BRICS evolved by way of a collective drive of its members who incidentally also play leading roles in their regions, namely South America, South Asia, East Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Arctic, as well as Southern Africa. Five BRICS summits since 20091 1 A sixth summit took place in Brazil (2014) and the Seventh in Russia during July 2015, when discussions around the New Development Bank seems to have dominated the agenda. map out elements of the BRIC/BRICS agenda or aspirations that increasingly frame BRICS as a player willing able to influence global politico-economic agendas. The latter agendas have been dominated for some time by states functioning individually or as members of international institutions2 2 These summits took place in Russia (2009), Brazil (2010), China 2011, India (2012), South Africa (2013). (Coning, Mandrup and Odgaard 2015Coning, Cedric Thomas Mandrup de and Liselotte Odgaard (eds). 2015. The BRICS and Coexistence. An Alternative Vision of World Order. Oxon: Routledge.: 26–29). Political and economic agendas shape much of the BRICS profile on the international scene, and from a realist perspective BRICS as a rising power entity touches on the revisionist-status quo framework of changes in the international system. Revisionism refers to changing power relations and dominance in the international system of relations between member states. The revisionist phenomenon assumes lesser to more revolutionary and even radical patterns of change as sought out by competing members (Buzan 1991Buzan, Barry. 1991. People States and Fear: An Agenda for International Security Studies in the post-Cold War Era. New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf.: 303). Even if only inferred, or deliberate, BRICS member countries hold the potential to change the status quo, or elements underpinning present power relations in the international system. This becomes more viable if BRICS can amicably harness maritime opportunities in the often-neglected South Atlantic, as well as draw upon the full geographic spectrum of their combined maritime assets.

While the political challenge to the current world order turns increasingly upon the rise of China versus the US, and is visible in contestations and rhetoric about maritime matters in the Western Pacific, two related aspects also play a role. The first is how the challenge is encapsulated within BRICS and particularly how energetic each member embraces or rejects the attributed Revisionist-Status Quo contest (Coning, Mandrup and Odgaard 2015Coning, Cedric Thomas Mandrup de and Liselotte Odgaard (eds). 2015. The BRICS and Coexistence. An Alternative Vision of World Order. Oxon: Routledge.: 2–3). While all five members often find themselves cast into a monolithic anti-Western mould, it is debatable whether they all practise such dealings in the real world of international relations. A second less power-infused and more idealist argument entails the pluralist outlook upon roles of entities other than states, and them being driven by the economic imperative in particular and more in line with the BRICS-economic perspective, a perspective that questions the low-key attention to the maritime side of matters.

Economic power looms large in the international system of states and is a significant tool of statecraft (Hough 2013Hough, Peter. 2013. Understanding Global Security. 3rd edn. Oxon: Routledge.: 106–107). While Coning, Mandrup and Odgaard (2015Coning, Cedric Thomas Mandrup de and Liselotte Odgaard (eds). 2015. The BRICS and Coexistence. An Alternative Vision of World Order. Oxon: Routledge.: 3), for example, promote the co-existence theory for explaining dynamics driving BRICS, the economic argument for the rise, status, and future position of BRICS remains relevant as well. It is difficult to frame BRICS as a drive for economic or political power, as both co-exist in a symbiotic way. Shifting from attributed economic power towards political influence is an inescapable dynamic, and the latent economic accelerators harboured within BRICS support its growing influence upon the political rules governing the international system (Kraska 2011Kraska, James. 2011. Maritime Power and the Law of the Sea: Expeditionary Operations in World Politics. Oxford: OUP.: 160–161). Such an economic drive requires of BRICS to also harness maritime opportunities for growth and development embedded in its sovereign waters and claimed maritime zones (The World Bank 2016World Bank. 2016. Oceans, fisheries and coastal economies. Brief 9, April 2016. At http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/environment/brief/oceans [Accessed on 14 May 2016].

http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/enviro...

).

Conflict, competition, and co-operation form indelible nuances in the rise of actors as individual or collective entities (Narlikar 2013Narlikar, Amrita. 2013. ‘Introduction: Negotiating the rise of new powers’. International Affairs, 89(3): 561–576.: 562–563). BRICS reflects conflict, co-operation and competition, but as a rising group, the BRICS grouping of states stimulates debate on its meaning, agenda, future status, and influence upon the international system. Governance, revisionism, power, South–South solidarity, polarity shifts, institutionalism, and competition or co-existence continue to mark the literature. BRICS is influential, but seemingly not immune to the harsh world of international politics and economic uncertainty (Hiscock and Ho 2014Hiscock, Mary and Io Ho, 2014. ‘Conclusions: The BRICS ascending, decline or plateau?’ In Io Ho and Mary Hiscock (eds), The rise of BRICS in the global political economy: Changing paradigms. Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 308-312.: 308). This reality heightens the imperative of opportunities previously neglected, and for a maritime BRICS the South Atlantic is one such opportunity given the power dynamics of the Indian and Western Pacific oceans.

How BRICS responds to the political and economic prospects of a ‘maritime BRICS’ in all probability also moulds political and economic agendas some attribute to BRICS. Whether co-existence, stark revisionism, or competition, a maritime nexus plays out as is further explained in the following section.

The BRICS maritime nexus

Geographically BRICS countries are coastal states from three continents with interconnecting oceans as an important physical nexus. The maritime connection implies competition and co-operation within BRICS, as well as with other maritime actors (state and non-state) to promote responsible use of the oceans and maritime governance (Kornegay 2013aKornegay, Francis. 2013a. ‘South Africa, the South Atlantic and the IBSA-BRICS equation: The Transatlantic state in transition’. Austral: Brazilian Journal of Strategy and International Relations, 2(3): 75–100.: 78). As a global commons, oceans are there for all to use in a competitive or co-operative manner and preferably within the ambit of the United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Kraska, however, views BRICS as a catalyst for disputing rules governing the international system, and in this regard he extends the suggested challenge to UNCLOS and its regulatory impact on sound ocean governance. Some BRICS members challenge the liberal framework for the use of the ocean and that one power (the USA) is expected to uphold regional and global order at sea (Kraska 2011Kraska, James. 2011. Maritime Power and the Law of the Sea: Expeditionary Operations in World Politics. Oxford: OUP.: 419). As BRICS members respond to the maritime interests at stake, they are bound to push for norm changes in their favour (Kraska 2011Kraska, James. 2011. Maritime Power and the Law of the Sea: Expeditionary Operations in World Politics. Oxford: OUP.: 417), although this does not imply rejecting UNCLOS as the dominant international paradigm. Such changes require collective action, and as BRICS members occupy five of the top 16 largest maritime Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ’s), concerted action from BRICS members to benefit more from their vast maritime domains is to be expected (Kraska 2011Kraska, James. 2011. Maritime Power and the Law of the Sea: Expeditionary Operations in World Politics. Oxford: OUP.: 114).

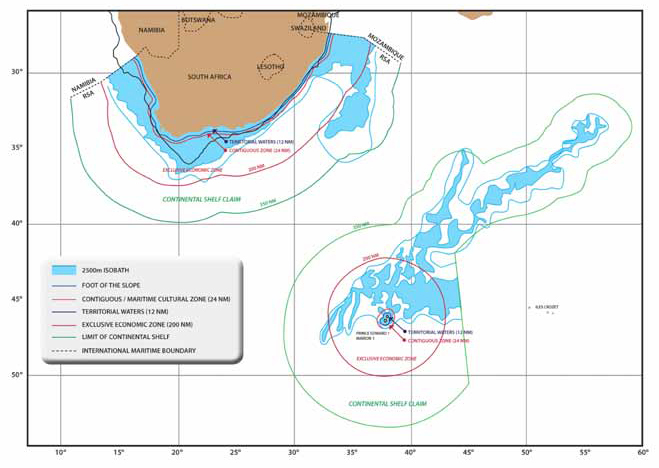

Vivero and Mateos (2010Vivero, Juan L Suárez de and Juan Rodrıguez Mateos. 2010. ‘Ocean governance in a competitive world: The BRIC countries as emerging maritime powers – building new geopolitical scenarios’. Marine Policy, 34(5):967–978.) present an overview of the BRIC maritime profile by emphasising their combined maritime territory, but also geopolitics as an indelible maritime component. As shown in Figure 1, the four BRIC countries collectively hold potential influence over the Arctic Sea (Russia) the Western Pacific (China and Russia), the Indian Ocean (India), and the western sphere of the South Atlantic (Brazil) (Vivero and Mateos 2010Vivero, Juan L Suárez de and Juan Rodrıguez Mateos. 2010. ‘Ocean governance in a competitive world: The BRIC countries as emerging maritime powers – building new geopolitical scenarios’. Marine Policy, 34(5):967–978.: 970–972). Even without South African membership, the authors estimated that by 2010 BRIC already represented a future economic entity of note and one with political power to follow in its wake. Even the initial BRIC grouping (before South African membership) harboured the potential of becoming a major player through its influence (real and potential) over important maritime settings, facilities, and future opportunities.

South Africa’s BRICS membership since 2011 in part designates the country as a declared gateway for BRICS to enter the African continent (Boulle and Chella 2014Boulle, Laurence and Jessie Chella. 2014. ‘The case of South Africa’. In Vai Io Lo and Mary Hiscock (eds), The Rise of the BRICS in the Global Political Economy: Changing Paradigms? Joining the BRICs. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 99–122.: 105). South Africa’s geostrategic location, its economy compared to the rest of Africa, its leadership role on the continent, as well as its membership of IBSAMAR (India-Brazil-South Africa Maritime) and IBSA (India-Brazil-South Africa Dialogue Forum),3 along with its leading role in the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS), all served to solidify the logic of South Africa’s BRICS membership (Kornegay 2013bKornegay, Francis. 2013b. ‘Laying the BRICS of a new world order: A conceptual scenario’. In Francis Kornegay and Narnia Bohler-Muller (eds), Laying the BRICS of a new global order: From Yekaterinburg 2009 to Ethekwini 2013, Pretoria: Africa Institute of South Africa, pp. 1–36.: 22). Here one finds an early, but underdeveloped maritime logic and an important maritime territorial ambit that accompanied the country’s membership (depicted as ZAF in Figure 1).

The void in the South American–Southern Atlantic nexus with that of China and India to the east became less accentuated with South Africa’s maritime domain covering roughly 4,340,000 km2. South African maritime territories and economic claims stretch into the south-western Indian Ocean, the Southern Ocean, and the South Atlantic (See Figure 1 and Figure 2) (Department of Defence of South Africa 2014Department of Defence of South Africa (RSA). 2014. South African Defence Review 2014. 25 March.: 6–3). Adding South Africa’s eastern and western maritime territories and economic zones, as reflected in Figure 1, lowers Brazil’s insularity and builds out the South Atlantic as another maritime zone of interest to a concentric maritime rim land for BRICS (Vivero and Mateos 2010Vivero, Juan L Suárez de and Juan Rodrıguez Mateos. 2010. ‘Ocean governance in a competitive world: The BRIC countries as emerging maritime powers – building new geopolitical scenarios’. Marine Policy, 34(5):967–978.: 970). In BRICS, one thus finds a grouping of states from the Global South with maritime territories and claimed economic zones reaching from the Arctic Sea, eastward through the Western Pacific, the Indian Ocean around southern Africa and into the South Atlantic Ocean.

Of interest is that in the immediate aftermath of joining BRICS, South Africa deployed a small task force in 2011 to patrol the waters off northern Mozambique in the south-western Indian Ocean (Martin 2014Martin, Guy. 2014. ‘Operation Copper now only with SA and Mozambique’. DefenceWeb, 20 March. At http://www.defenceweb.co.za/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=34071:operation-copper-now-only-with-sa-and-mozambique&catid=108:maritime-security. [Accessed on 21 October 2014].

http://www.defenceweb.co.za/index.php?o...

). Operation Copper reflects a maritime response by the South African government to prevent the possible southward migration of the piracy threat off Somalia, where other BRICS members had several naval platforms engaged in anti-piracy operations. By 2013, however, South Africa also declared its intent to deploy a naval vessel along the western shore of the Southern African Development Community (SADC)4

4

Angola, Botswana, DR Congo, Lesotho, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Madagascar, Namibia, Seychelles, South Africa, Swaziland, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

in the Atlantic to help stem a possible spill-over to the south of the deteriorating maritime security situation in the Gulf of Guinea (DefenceWeb 2014DefenceWeb. 2014. ‘Africa’s West Coast is next Navy anti-piracy deployment’. 25 September. At http://www.defenceweb.co.za/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=36370&catid=108&Itemid=233. [Accessed on 23 May 2016].

http://www.defenceweb.co.za/index.php?o...

). By 2016, South Africa repeated in the Defence Minister’s Budget Speech (11 May 2016) its intent to co-operate with countries like Namibia and Angola to contain piracy threats off the African west coast, offering leeway to co-operate even more closely with Brazil and its South Atlantic outreach towards West Africa.

The 2014 South African Defence Review emphasises South Africa’s maritime territories by accentuating size, location, and resources. The latest Defence Review articulates South Africa’s maritime importance as a location along the major Cape Sea Route for trade, an EEZ of 1,553,000 km2, with a further extension of the continental shelf submitted to the UN (Department of Defence of South Africa 2014Department of Defence of South Africa (RSA). 2014. South African Defence Review 2014. 25 March.: 63–64). South Africa is also obliged to co-operate on maritime matters within the 15-member SADC grouping and the African Union with its declared maritime agenda encapsulated by the 2050 Africa’s Integrated Maritime Strategy. South Africa is also perhaps the only country in the region displaying elements of ‘being maritime’ in pursuit of national security by physically protecting its trade routes, co-operating to promote regional maritime security, and actively partaking in African and other international maritime regimes and arrangements to promote maritime security governance off eastern and western Africa (Department of Defence of South Africa 2011Department of Defence of South Africa (RSA). 2011. Address by L N Sisulu, (MP) minister of defence and military veterans at the SADC extraordinary meeting on regional anti-piracy strategy. 25 July.).

The above argument only takes on meaning if viewed in terms of a larger setting, such as maritime contributions to a blue or maritime understanding of BRICS. BRICS holds both real and potential power by way of its access to ocean resources brought about by its combined maritime territories. As a flow and a stock resource, the sea becomes a multiplier to BRICS members to be utilised individually, as well as collectively. The fundamental matter at play is to unlock the oceans’ potential on offer, and promoting maritime security is crucial.

Maritime security: then and now

As an input, maritime security during times of peace in particular draws upon the ends, ways, and means that actors employ to mitigate threats and vulnerabilities at sea. As an output, maritime security is expected to offer safe resource harvesting, a medium of transport without interference, the sea as an area of sovereignty to benefit member states, and a medium to extend, or gain, influence and ideas.5 5 Maritime sovereignty is not akin to that on land and is more circumscribed by the law of the sea. Article 2, Part 2 of UNCLOS frames different maritime zones and countries have different rights and responsibilities over maritime zones as territorial seas, economic zones, and the high seas. Littoral countries have territorial waters of 12 nm over which they have sovereignty and rights akin to their landward sovereignty. Littoral countries also have the right to claim up to 120 nm as their EEZ, and this claim must be recognised or contested in court by other countries, but UNCLOS determines country rights and responsibilities, as it does for the high seas. Collectively, inputs and outputs ideally bring about conditions of good order at sea that Bateman, Ho and Chan (2009Bateman, Sam Joshua Ho and Jane Chan. 2009. Good order at sea in Southeast Asia. RSISS Policy Paper. S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, April, p. 7.: 7) outline as ensuring ‘[…] the safety and security of shipping and permit[ing] countries to pursue their maritime interests and develop their marine resources in an ecologically sustainable and peaceful manner in accordance with international law.’ A growing number of threats such as piracy, potential terrorism, criminality, insurgency spilling offshore, and illegal practices by an ever-growing host of state and non-state perpetrators undermine maritime security. Speller highlights this threat migration by setting it within the extended range of threats characterised by diversity, unpredictability, and transnational and asymmetric features that maritime threats now display (Speller 2014Speller, Ian. 2014. Understanding Naval Warfare. Oxon: Routledge.: 151). The irregular and largely non-state threat landscape plays out amidst a growing understanding of the sea as a primary medium for development, but one checked by areas of bad order at sea.

Elements of a more forward-looking maritime security agenda place less focus on coercive diplomacy and threats in favour of responsible management towards which naval forces must contribute. The latter approach is visible in, for example, the aspects of multidisciplinarity reflected in contemporary marine policy, marine science, economics, and security (Herbert-Burns, Bateman and Lehr 2009Herbert-Burns, Rupert, Sam Bateman and Peter Lehr (eds). 2009. Lloyds MIU Handbook of Maritime Security. Boca Raton FL: CRC Press.: xix). Understanding the multiplicity at play, bad order at sea often depicts its own complexity as security, jurisdiction, policing, or humanitarian threats and vulnerabilities intersect at sea amidst a growing understanding by governments and business of the dangers involved. Unfortunately, each avenue requires and generates a different set of management or resolution options towards which navies have to contribute (Bueger 2015Bueger, Christian. 2015. ‘From dusk to dawn. Maritime domain awareness in South East Asia’. Contemporary Southeast Asia, 37(2): 157–182.: 160). Similar to landward threats, threats at sea require reactions, depict roles for an array of security actors or agencies, and call for better measures to contain threats against safer use of the oceans. While the threat for BRICS in the South China Sea is confrontational with a naval emphasis, in the Indian Ocean it leans towards softer threats to good order at sea and power competition, while the South Atlantic offers the most peaceful domain in the maritime make-up of BRICS.

Maritime trade depends upon safe and secure oceans, and the introduction of new safety and security regimes, protocols, and codes underline the norm of safe and secure oceans. Lloyds, however, points out that operationally all does not automatically fall into place (Herbert-Burns, Bateman and Lehr 2009Herbert-Burns, Rupert, Sam Bateman and Peter Lehr (eds). 2009. Lloyds MIU Handbook of Maritime Security. Boca Raton FL: CRC Press.: xxiii). The reality of layered progress plays out in the Western Indian Ocean where advanced, upcoming, and minimalist maritime countries have been co-operating since 2007/8 in an effort to subdue the piracy threat. Maritime security beyond the piracy fixation became more complex as a result of its dynamic threat profile, as well as the array of responses devised by states and organisations below and above the state level (Bueger 2013Bueger, Christian. 2013. ‘Communities of security practice at work? Emerging African maritime security regime’. African Security, 6(3-4): 297-316.: 298). While the piracy threat stimulated most of the responses, the growing realisation of how the maritime commons ties into the economic, developmental, and political agendas of groupings such as BRICS generated more critical thinking on maritime security in order to cover the expanse of threats. The narrow focus of antipiracy does not cover all maritime crime threats. Thus there is a call for more co-operation to deal with the growing expanse of maritime threats in need of attention. Infrastructure at sea, resource harvesting (living and non-living), avoiding conflict, and preserving the sea both as an environment protected from pollution and overuse and a future environment for humanity increasingly serve to secure the sea as a flow and stock resource through responsible stewardship.

With regard to BRICS and its maritime territories as stepping stones for its socio-economic agendas in particular, maritime security threats outlined earlier and responses call for attention. If 2010 marks the birth of BRICS, the date also overlaps with a shift in understanding and response to matters of maritime security. Lloyds broadly sets out this more forward-looking understanding of a new maritime security environment along the lines of industry sectors faced with more threats and larger sets of legal, regional, and national responses (Herbert-Burns, Bateman and Lehr 2009Herbert-Burns, Rupert, Sam Bateman and Peter Lehr (eds). 2009. Lloyds MIU Handbook of Maritime Security. Boca Raton FL: CRC Press.: xxiii). In 2010, Vivero and Mateos (2010Vivero, Juan L Suárez de and Juan Rodrıguez Mateos. 2010. ‘Ocean governance in a competitive world: The BRIC countries as emerging maritime powers – building new geopolitical scenarios’. Marine Policy, 34(5):967–978.) also set BRIC (although the same goes for BRICS) within the ambit of the aforementioned newer maritime security thought. Competitiveness, knowledge, and innovation co-exist alongside leadership, new technologies, and energy security as contours of contemporary maritime security dynamics. Maritime security thinking based upon unfamiliar threats and more creative responses takes shape within the extent to which BRICS countries (upcoming Brazil and South Africa in particular) implicitly or explicitly understand their progress and collective influence in maritime terms. Although the Russian, Chinese, and Indian national interests have long maritime histories, Brazilian national interest has perhaps less so, and South Africa’s stance on its maritime connection must move beyond mere statements and intentions (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2012: 49). As a result, South Africa and Brazil have more conceptual and operational room for manoeuvre to secure the South Atlantic through innovative measures and dynamics less driven by power and competition.

Ocean governance is an international responsibility6 6 Ocean governance refers to the rights and obligations of state parties to attend to their rights and obligations in the oceans and in particular as outlined by UNCLOS. Of particular importance are matters related to the sustained and responsible use of the oceans, its importance to world futures, and oceans also becoming problem areas that must be policed, managed and resolved. (Bateman 2016Bateman, Sam. 2016. ‘Maritime security governance in the Indian Ocean’. Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, 12(1): 6.: 6) and all the more influenced by countries other than traditional power actors in the international system, and here BRICS countries feature prominently (Vivero and Mateos 2010Vivero, Juan L Suárez de and Juan Rodrıguez Mateos. 2010. ‘Ocean governance in a competitive world: The BRIC countries as emerging maritime powers – building new geopolitical scenarios’. Marine Policy, 34(5):967–978.: 974). Aspirations of good governance suppose economic prosperity to sustain the reforms that culminate in high-quality public goods to societies (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2012Bertelsmann Stiftung. 2012. Governance capacities in the BRICS. Sustainable governance indicators. Gutersloh (Germany): Bertelsmann Stiftung.: 5). For BRICS countries with their territorial waters and claimed economic zones, this argument pertains to maritime governance in pursuit of the economic benefit oceans offer. Maintaining maritime security and bringing to fruition new thoughts on policies, regimes, and codes to govern the oceans are set to play a determining role. China and India’s economic growth through energy security and secured trade by sea also become subject to new ‘rules’ of responsibility. South Africa with its limited maritime capability to pursue good order at sea in its ocean territories must remain in step, even regionally. Brazil must also ensure maximum benefit from its offshore oil and gas possessions in the southern Atlantic under new maritime regimes and as a reliable BRICS member, but also help to promote maritime security over a wider ambit of the South Atlantic. In essence, BRICS countries have significant maritime territories individually and collectively, but the advantages can no longer only be harnessed under the competitive banner of winner takes all. Collective responsibilities to benefit more and sustainability to benefit longer have become the guiding intelligence (United Nations 2012: 30).

A deepened maritime nexus for BRICS

BRICS brings countries and their regions into closer proximity to form a virtual region (Boulle and Chella 2014Boulle, Laurence and Jessie Chella. 2014. ‘The case of South Africa’. In Vai Io Lo and Mary Hiscock (eds), The Rise of the BRICS in the Global Political Economy: Changing Paradigms? Joining the BRICs. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 99–122.:101). Although South Africa’s inclusion is often frowned upon, the maritime nexus it brings is an important, but overlooked contribution, in particular regarding the South Atlantic. Critics point to South Africa’s small economic footprint, the country not being a global player, it’s human security agendas clashing with Chinese and Russian policies, and Nigeria being the better contender as South Africa does not represent Africa (Olivier 2013: 400). From a maritime angle, however, the landward gateway into Africa can hardly function in the absence of the maritime pathway based on sound maritime governance. The argument of a region also brings Southern Africa and its maritime territory into focus (Boulle and Chella 2014Boulle, Laurence and Jessie Chella. 2014. ‘The case of South Africa’. In Vai Io Lo and Mary Hiscock (eds), The Rise of the BRICS in the Global Political Economy: Changing Paradigms? Joining the BRICs. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 99–122.: 106). South Africa is, for example, the only BRICS member that is truly bi-coastal in nature, and its role in continental Africa turns upon the maritime access it affords to the south-western Indian Ocean and the South Atlantic (Kornegay 2013aKornegay, Francis. 2013a. ‘South Africa, the South Atlantic and the IBSA-BRICS equation: The Transatlantic state in transition’. Austral: Brazilian Journal of Strategy and International Relations, 2(3): 75–100.: 80). The BRICS maritime nexus ultimately runs via national maritime territories, claimed economic zones, and the high seas to connect centres of production and consumption and thus the imperative of security at sea to support an interconnected system of sea trade for BRICS members (Borchard 2014Borchard, Heiko. 2014. Maritime security at risk. Trends, future threat vectors and capability requirements. Lucerne: Sandfire.: 8).

Till’s (2013Till, Geoffrey. 2013. Seapower. A Guide for the Twenty-First Century. Oxon: Routledge.: 27) argument about a global system based on sea trade accentuates the importance of the oceans as a flow and stock resource. However, Till avers that it is a system that also needs to be taken care of by way of good order at sea during times of peace (Till 2013Till, Geoffrey. 2013. Seapower. A Guide for the Twenty-First Century. Oxon: Routledge.: 27). Borchard (2014Borchard, Heiko. 2014. Maritime security at risk. Trends, future threat vectors and capability requirements. Lucerne: Sandfire.: 34) supports Till’s emphasis when he outlines very particular aspects of protection that collectively enhance maritime security through ongoing Maritime Security Sector reform – a matter in step with new maritime security thinking mentioned earlier. In addition, transformation of multiple maritime security sectors is necessary to promote or benefit from co-operation. Co-operation to profit more but also to protect and sustain are two fundamentals bound to eventually inform and underpin the BRICS maritime nexus, but one demanding higher levels of responsibility. Economic and development arguments dominate debates about the future growth and development of the world, and BRICS as an economic block from the developing world can hardly escape this connection (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2012Bertelsmann Stiftung. 2012. Governance capacities in the BRICS. Sustainable governance indicators. Gutersloh (Germany): Bertelsmann Stiftung.: 10–11). Governance as an imperative for economic progress within the block must be understood to include maritime governance and not only landward concerns.

BRICS countries own the largest single and combined fleets of fishing and trade vessels that sail the oceans, highlighting the importance of co-operating towards secure sea lanes across the oceans and upholding the rules that regulate these highways. While Borchard (2014Borchard, Heiko. 2014. Maritime security at risk. Trends, future threat vectors and capability requirements. Lucerne: Sandfire.: 21–22), for example, points out the general growth of maritime trade by way of shipping flows and growth in particular, as well as aspects such as harbours and container freight, Vivero and Mateos (2010Vivero, Juan L Suárez de and Juan Rodrıguez Mateos. 2010. ‘Ocean governance in a competitive world: The BRIC countries as emerging maritime powers – building new geopolitical scenarios’. Marine Policy, 34(5):967–978.: 972) tie these to BRIC(S) and the rise of container mega-ports, of which 21 out of the top 100 are found in Brazil (1), China (17), India (2), and Russia (1) amidst rapid growth rates in their handling of cargo. Mega-containerisation is impressive, but its most essential need is securing the sea as a flow resource for optimal trading in containerised goods, but also strategic goods such as energy resources.

Energy is not only a central tenet of the future economic status of BRICS members, but also a critical object of security. In this vein Borchard (2014Borchard, Heiko. 2014. Maritime security at risk. Trends, future threat vectors and capability requirements. Lucerne: Sandfire.), for example, flags the risk of a simultaneously rising threat landscape alongside the deeper understanding of benefits the sea holds. As a stock resource, according to Abdenur and Souza Neto (2013aAbdenur, Adriana and Danilo Marcondes de Souza Neto. 2013a. Brazil’s maritime strategy in the south Atlantic. The nexus between security and resources. Occasional Paper no 161. Global Powers and Africa Programme, South African institute of International Affairs. November.: 7) the maritime node for BRICS probably resides in energy resources at sea off the Brazilian coast, while Till (2013Till, Geoffrey. 2013. Seapower. A Guide for the Twenty-First Century. Oxon: Routledge.: 319–320) tags the pressure from China for control over maritime territory housing potential oil reserves in the South China Sea with South Africa showing a renewed drive for oil and gas exploration off its south Atlantic coastline (South African Government News Agency 2015: 2). As a flow resource for energy, India and China are major players. Their demand for oil and gas still require an uninterrupted flow from dispersed sources in, for example, South America, where Brazil is perhaps the main stabilising entity for the South Atlantic. This dependence upon imported energy sources (China 50%+ and India 76%) implies reliance upon secure sea lanes and protected infrastructure at sea (International Energy Agency 2012: 6; 2014International Energy Agency. 2012. Oil and gas security. Emergency response from IEA countries. Paris: OECD/IEA.: 540). The latter’s sea lanes and deposits reach beyond their immediate regions or territorial waters given that both have geographically diversified oil flows by sea. India and China thus have vital interests in safe and secure international sea lanes for their energy needs in particular (Noel 2014Noël, Pierre. 2014. ‘Asia’s energy supply and maritime security’. Survival: Global Politics and Strategy, 56(3):201–216.: 204–205). Securing energy resources within BRICS, or ensuring flows toward BRICS, or bringing new energy hubs onto line all hold a maritime security nexus. For example, secured oil fields off Brazil, access to upcoming African oil fields off West Africa, and the flow of crude from Brazil and the Gulf of Guinea bring together the maritime security, energy security, and economic prospects of BRICS members. The aforementioned energy triad also highlights the potential contribution of a stable South Atlantic Ocean in energy flows to BRICS members.

Living and other marine resources are not unlimited, and pressure mounts to control the quest of countries. Some resources are on the decline, and the dangers of over-exploitation are well known, as stated so explicitly at the Rio+20 meeting in Brazil in 2012 (United Nations 2012United Nations. 2012. Report of the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 20–22 June.: 30–32). Geography determines broadly, or very particularly in some cases, who gets what from the sea. Ultimately, maritime sovereignty over territorial waters through jurisdiction stems from who can enforce jurisdiction to control access to resources and responsible and safe exploitation. Controlled access (whether self-imposed or coerced) is particularly relevant in the 21st century, as the exploitation of weak maritime governance for criminal purposes is growing rapidly. In addition, threats to profitable resources and other attributes of the sea have become the essence of the risks confronting countries dependent upon harvesting and moving resources and products by sea (National Research Council 2008National Research Council of the United States of America (NRC). 2008. Maritime security partnerships. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.: 17–18). In spite of some actions to the contrary, as explained towards the end of the discussion, it is in the interest of BRICS to help ensure good order at sea either physically, virtually, or by proxy, but preferably within the ambit of UNCLOS.

Physically it remains the responsibility of BRICS governments to employ naval and other policing assets such as coast guards to contribute visibly to safeguarding sea lines of communication unilaterally, or in a co-operative fashion. China, Russia and India are, for example, engaging in programmes to grow their naval capabilities to secure their maritime territories and respond to more immediate and close threats to their waters (Veen 2012Veen, Ed. 2012. The sea: Playground of the superpowers. On the maritime strategy of superpowers. The Hague Center for Strategic Studies. The Hague No 13/3/12.: 89). They also undertake longer-range missions such as supporting international naval responses against piracy in the Western Indian Ocean (Medcalf 2010Medcalf, Rory. 2010. ‘Unselfish giants? The impact of China and India as security contributors in Asia’. Discussion Notes, University of New South Wales, July.: 4–5). Drawing this out to the South Atlantic, naval activities are visible as well, but as discussed in the following section, these activities are often superseded by the ‘realpolitik’ of some BRICS members in the Indian Ocean and Pacific Ocean which places the south Atlantic in the shadows.

Keeping in step with responsible ocean governance, maritime domain awareness is increasingly also a function of secured digital infrastructure under the sea or on systems on vessels traversing the oceans. Size and distance characterise the maritime interests of BRICS members given their locations and thus the importance of the virtual options on offer. Virtual good order through cyber technologies and infrastructure at sea transpires in that countries that house it are obliged to protect the cyber-infrastructure in their waters and ensure its safety. Countries and their vessels at sea (owned or not) benefit collectively from the information and subsequent domain awareness such infrastructure offers. Borchard (2014Borchard, Heiko. 2014. Maritime security at risk. Trends, future threat vectors and capability requirements. Lucerne: Sandfire.: 23–24) notes the importance of digital sea lanes for the optimal functioning of the maritime trade regime and becoming an integral element of infrastructure at sea to be maintained and protected in order to optimise the operation of the maritime trade system. All five BRICS members are important landing points and maritime conduits for subsea cables passing through their waters. They also have large commercial fleets dependent on the digital infrastructure of the fleets or that below the ocean. In combination with landward infrastructure, one finds a burgeoning of ways and means for countries to maintain virtual awareness as an element of maritime domain awareness and promoting maritime security partnerships. The technologies on land, at sea, and in space are integrated to such an extent that they promote maritime security, and this is visible in how naval forces for example, managed to build a ‘digital’ image of piracy off the Horn of Africa (Bueger and Leander 2014Bueger, Christian and Anna Leander 2014. Technological solutions to the piracy problem: Lessons learned from counter-piracy off the Horn of Africa, Piracy-Studies.Org, Research Portal for Maritime Security, Copenhagen Business School, 26 May 2014. At http://piracy-studies.org/2014/technological-solutions-to-the-piracy-problem-lessons-learned-from-counter-piracy-off-the-horn-of-africa/. [Accessed on 25 February 2015].

http://piracy-studies.org/2014/technolog...

). Given the maritime expanses of BRICS, digital security enhancement is a critical link to maintain order, and particularly so for Brazil and South Africa, who face the vast South Atlantic with limited naval assets and who are best positioned to fly the BRICS banner at sea.

By proxy, one finds that it is well within the BRICS architecture to harness the geographic locations of members to promote good order at sea over extended maritime domains. In a sense this is akin to local sea control over areas deemed important through inclusive or participatory good order at sea (Till 2013Till, Geoffrey. 2013. Seapower. A Guide for the Twenty-First Century. Oxon: Routledge.: 39). Direct and indirect control over the waters surrounding BRICS members collectively represent maritime zones connecting international waters stretching from the south Atlantic past southern Africa to India and towards China and Russian waters (See Figure 1). Although not contiguous, members can depend upon territorial and claimed economic zones under the jurisdiction of a member state, or some measure thereof. Whether as maritime way stations or as staging areas for collective responses or as hubs that other members need to be less concerned about, proximate good order at sea is beneficial to a ‘blue’ BRICS. In this vein, the South Atlantic again features prominently given the absence of the blue water navies of Russia, China, and India, and thus less intrusion from the USA, which act as catalysts for a more placid South Atlantic. Thus the notion of a blue BRICS is given deeper meaning by the participatory activities of Brazil and South Africa in the absence of more aggressive big powers in the South Atlantic.

Blue BRICS: bringing in the South Atlantic

South Africa’s inclusion completes an important link in the maritime logic of BRICS and with regard to the South Atlantic in particular. The maritime gateway to the South Atlantic, however, must be operationalised and South Africa and Brazil take the lead – however embryonic this partnership might appear. The absence of South African–Brazilian tensions due to distance and the absence of conflicting national interests promote amicable co-operation. Co-operation is thus afforded more room to take root and develop. The Brazil–South Africa nexus to the South Atlantic is subsequently more reflective of the rational framework of co-operation given the interest in economic growth and partnerships around common interests and threat reduction.7 7 The rationalist framework promotes co-operation or the potential for co-operation between states as opposed to competition and power balances based upon coercion or the threat thereof promoted by the more realist theories.

While the Indian Ocean and Western Pacific off China is a hive of power competition involving three prominent BRICS members (India, China, and now also Russia), the South Atlantic is rather untouched, but simultaneously an attractive opportunity for interference by state and non-state actors (Rahkra 2015: 62–63). Although India has an annual presence in the South Atlantic by way of IBSAMAR, China does not. China’s navy has visited the South African four times in the recent past, but exercised with the South African Navy for the first time in 2016 in the South Atlantic under the BRICS banner (Wingrin 2016Wingrin, Dean. ‘South African and Chinese navies increase collaboration’, DefenceWeb. 17 May. At http://www.defenceweb.co.za/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=43520&catid=74&Itemid=30. [Accessed on 16 February 2017].

http://www.defenceweb.co.za/index.php?o...

). Although not akin to Chinese Naval presence in the Western Indian Ocean, which functions as part of their Far Seas maritime outlook,8

8

Chinese naval presence in the Western Indian Ocean emanates primarily from a direct threat to Chinese shipping and trade transiting the Western Indian Ocean. As for the South Atlantic, Chinese interests are more akin to supporting Chinese Multi-National Corporations, Chinese outlook of (Chinese) people first, investment protection, and promoting security as part of the Chinese and BRICS interests in Africa.

the 2016 exercise must be understood in terms of the earlier mention of physical, proxy, and virtual maritime security awareness for the sake of Chinese and BRICS interests (Chun 2013Chun, Zhang. 2013. ‘A promising partnership between BRICS and Africa: A Chinese perspective.’ In Sven Grim (ed), The BRICS Summit 2013: Is the road from Durban leading to Africa? The China Monitor Special Edition. Centre for Chinese Studies, Stellenbosch, pp. 30–37.: 33–34). China’s expatriate population in Africa and its trade and energy interests are formative matters in how China views its foreign interests, with people recently featuring more prominently as a matter of national interest and to be secured in distant locations (Chun 2013Chun, Zhang. 2013. ‘A promising partnership between BRICS and Africa: A Chinese perspective.’ In Sven Grim (ed), The BRICS Summit 2013: Is the road from Durban leading to Africa? The China Monitor Special Edition. Centre for Chinese Studies, Stellenbosch, pp. 30–37.: 34). A Chinese naval base in the South Atlantic is rumoured as well, with Namibia (Walvis Bay) noted as the possible location for a more permanent Chinese naval presence in these very distant seas if one denotes it within the Chinese ambit of its maritime expansion (O’Brien 2015O’Brien, Robert. 2015. ‘China’s next move: A naval base in the South Atlantic?’ China and East Asia, National Security and Defence, Pacific Council on International Policy. At: https://www.pacificcouncil.org/newsroom/chinas-next-move-naval-base-south-atlantic. [Accessed on 22 February 2017].

https://www.pacificcouncil.org/newsroom/...

). The views on and activities in the case of the South Atlantic take shape amidst trans-Atlantic and Latin-African goodwill in addition to traditional and cultural ties between Brazil and Africa that reinforce the collective maritime interest of the two BRICS members towards the eastern fringes.

Brazil has launched particular programmes to promote security in the South Atlantic. First, more unilateral actions in Brazil’s national interests reflect strategic, budgetary, and military focus areas with a naval emphasis for a better physical presence as well as deterrence at sea. The latter finds expression through co-operation with France on nuclear technologies for nuclear attack submarines and their strategic deterrence value. In addition, softer geographic measures such as the expansion of national waters for resource access and national ambitions also play a role, but both require a diplomacy-naval power backdrop (Abdenur and Souza Neto 2013aAbdenur, Adriana and Danilo Marcondes de Souza Neto. 2013a. Brazil’s maritime strategy in the south Atlantic. The nexus between security and resources. Occasional Paper no 161. Global Powers and Africa Programme, South African institute of International Affairs. November.: 5–6). The resource boom of the second decade of the 21st century also stimulated the drive for securing benefits, as do external interferences. Thus Brazil has an interest in preventing the South Atlantic from becoming subject to the power posturing in, for example, the Indian Ocean (Abdenur and Souza Neto 2013bAbdenur, Adriana and Danilo Marcondes de Souza Neto. 2013b. ‘Brazil’s maritime strategy in the South Atlantic: The nexus between security and resources’. In International Security: Brazil Emerging in the Global Security Order. Konrad Adenauer Stiftung. 28 November: 173–184.: 176). While Brazil extends its national influence over the South Atlantic through naval and other national claims, these measures have limits – a matter addressed in part through growing relationships with African countries.

BRICS ties Brazil and South Africa into a co-operative partnership through old and new arrangements. Old arrangements stem from their collective history, as well as earlier agreements like IBSAMAR, IBSA, and similar agreements between Brazil, India, and South Africa (Abdenur and Souza Neto 2013aAbdenur, Adriana and Danilo Marcondes de Souza Neto. 2013a. Brazil’s maritime strategy in the south Atlantic. The nexus between security and resources. Occasional Paper no 161. Global Powers and Africa Programme, South African institute of International Affairs. November.: 12). In addition, with South Africa located at the crossing between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, the resultant maritime confluence of the two oceans promotes naval co-operation for stability and security in the South Atlantic and to the east towards the Western Indian Ocean (Kornegay 2013aKornegay, Francis. 2013a. ‘South Africa, the South Atlantic and the IBSA-BRICS equation: The Transatlantic state in transition’. Austral: Brazilian Journal of Strategy and International Relations, 2(3): 75–100.: 79, 85). IBSA solidifies more recent ties between three BRICS partners (Brazil, India, South Africa) with a primary focus to the south of Africa, implicating Brazil and South Africa as partners to promote maritime security in the South Atlantic. New ways become apparent from how South Africa and Brazil now both extend their ties towards West Africa across the south Atlantic. Brazil is particularly interested in opposing non-traditional threats in the South Atlantic and those holding economic security consequences (Abdenur and Souza Neto 2013bAbdenur, Adriana and Danilo Marcondes de Souza Neto. 2013b. ‘Brazil’s maritime strategy in the South Atlantic: The nexus between security and resources’. In International Security: Brazil Emerging in the Global Security Order. Konrad Adenauer Stiftung. 28 November: 173–184.: 176). Containing non-traditional threats through maritime domain awareness requires co-operative partnerships and thus the outreach to African actors on the eastern fringes of the South Atlantic (Walker 2015Walker, Timothy. 2015. Enhancing maritime domain awareness in Africa. Policy Brief 97. Institute for Security Studies October 2015.: 2).

Brazil’s outreach to countries off West Africa in particular establishes a footprint across the South Atlantic. Angola, Guinea Bissau, and other former Portuguese colonies receive close attention due to the common language–colonial link. Namibia is also tied into the outreach, with the main focus being naval and to assist with training matters to empower Namibia in extending sovereignty over its maritime resources (Abdenur and Souza Neto 2013aAbdenur, Adriana and Danilo Marcondes de Souza Neto. 2013a. Brazil’s maritime strategy in the south Atlantic. The nexus between security and resources. Occasional Paper no 161. Global Powers and Africa Programme, South African institute of International Affairs. November.: 11). The West African outreach also overlaps with the volatile Gulf of Guinea. By 2016 crime in the Gulf of Guinea had become a primary threat to shipping traversing this region and those harvesting marine resources, and held a real potential to spill south towards South Africa – a threat already identified during 2014 (DefenceWeb 2014DefenceWeb. 2014. ‘Africa’s West Coast is next Navy anti-piracy deployment’. 25 September. At http://www.defenceweb.co.za/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=36370&catid=108&Itemid=233. [Accessed on 23 May 2016].

http://www.defenceweb.co.za/index.php?o...

). It is thus not surprising that some view South African involvement in promoting security in the South Atlantic and with regard to the Gulf of Guinea in particular as a foreign policy priority for the 21st century (Lalbahadur, Du Plessis and Grobbelaar 2015Lalbahadur, Aditi, Rudolp Du Plessis and Neuma Grobbelaar. 2015. South Africa’s foreign policy priorities for the 21st century: A closer look at the potential co-operation in the South Atlantic zone. South African Institute for International Affairs, written for Polity.org.za. 21 May. At http://www.polity.org.za/print-version/south-africas-foreign-policy-priorities-for-the-21st-century-a-closer-look-at-the-potential-for-co-operation-in-the-south-atlantic-zone-2015-05-21. [Accessed 23 May 2016].

http://www.polity.org.za/print-version/s...

). Although not backed by significant naval measures, South African government statements increasingly recognise the inevitable turn to the sea and the western littoral in particular.

South Africa’s Operation Phakisa holds that untapped marine resources stand to contribute greatly to the South African GDP by developing and refining matters on marine transport, manufacturing, offshore oil and gas exploration, aquaculture, and marine protection services, as well as governance (South African Government News Agency 2014South African Government News Agency. 2014. ‘Operation Phakisa to move SA forward’. 19 July. At http://www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/operation-phakisa-move-sa-forward. [Accessed on 10 January 2015].

http://www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/op...

: 2). Within the broader debate often characterised by Africa’s neglect of its ocean territories, South Africa’s declared intent holds promise for BRICS of an interest-driven custodianship towards order and security at sea off its southernmost partner. At the continental level, Africa has also adjusted its landward fixation to tighten up on maritime security to harness the potential embedded in the oceans. In this manner, South Africa offers not only a maritime gateway into continental Africa, but also one extending west into the South Atlantic and thus an initiative to augment the drive from Brazil and a common set of objectives.

South Africa holds membership of SADC and thus ties to Namibia, Angola, and DR Congo as regional partners. South Africa and Angola are two major players and with Nigeria further north house the two largest oil production and resources on the African continent (Yoon 2016Yoon, Sangwon. 2016. ‘Nigeria and Angola’s ratings cut by Moody’s following review’, Mail and Guardian Africa, 30 April. At: http://mgafrica.com/article/2016-04-30-africas-largest-oil-producers-nigeria-and-angolas-ratings-cut-by-moodys-following-review. [Accessed on 30 May 2016].

http://mgafrica.com/article/2016-04-30-a...

). African and other arrangements to promote awareness and ultimately security in the South Atlantic have particular significance. Important is the South African membership of maritime arrangements up the western coast of Africa, such as the Benguela Current Convention (BCC of 2013) with Namibia and Angola to preserve and secure the use of resources in the regions and extend its benefits to citizens. In addition, South Africa is also a member of the AU and subscribes to the AIMS 2050 maritime strategy to secure and responsibly use ocean resources off Africa. South Africa also holds membership of the 1986 Zone of Peace and Cooperation of the South Atlantic (ZPSCA) with South American and West African members. Although perhaps dormant, in conjunction with IBSA/IBSAMAR, BCC, ECOWAS, and SADC, as well as the AU, this offers conduits for interstate co-operation on maritime security in the South Atlantic (Lalbahadur, Du Plessis and Grobbelaar 2015Lalbahadur, Aditi, Rudolp Du Plessis and Neuma Grobbelaar. 2015. South Africa’s foreign policy priorities for the 21st century: A closer look at the potential co-operation in the South Atlantic zone. South African Institute for International Affairs, written for Polity.org.za. 21 May. At http://www.polity.org.za/print-version/south-africas-foreign-policy-priorities-for-the-21st-century-a-closer-look-at-the-potential-for-co-operation-in-the-south-atlantic-zone-2015-05-21. [Accessed 23 May 2016].

http://www.polity.org.za/print-version/s...

).

South Africa faces the duality of having to split its strategic focus between two oceans and thus its maritime resources as well (Royeppen and Kornegay 2015Royeppen, Andrea and Francis Kornegay. 2015. ‘Southern Africa and the Indian Ocean-South Atlantic nexus: Blue economy and prospects for regional cooperation’. Global Insight, No. 119, Institute for Global Dialogue.: 3). A definite decision on where to place its maritime thrust is thus unavoidable, and for the moment the operational execution remains in the Mozambique Channel. This operational reality hovers in the shadows of a growing South African concern with events off West Africa and its BRICS/IBSA ties with Brazil across the South Atlantic. South Africa’s geographic position and its maritime zones contribute to the BRICS maritime landscape, but it is also the BRICS member closest to Brazil and with an Atlantic seaboard (Pereira 2013Pereira, Analucia. 2013. ‘The South Atlantic, Southern Africa and South America: Cooperation and development’. Austral: Brazilian Journal of Strategy and International Relations, 2(4): 31–35.: 41). Alongside political expressions of a greater interest in events along the Afro-Atlantic coastline, with a limited naval capability, South Africa is at least symbolically and verbally tied to the South Atlantic for promoting maritime security as a BRICS member.

However, South Africa is also dependent upon the rationalist outlook of building partnerships, co-operation, and international cooperation with countries like Brazil, Angola, and Nigeria to promote the South Atlantic as a zone of peace and co-operation (Pereira 2013Pereira, Analucia. 2013. ‘The South Atlantic, Southern Africa and South America: Cooperation and development’. Austral: Brazilian Journal of Strategy and International Relations, 2(4): 31–35.: 40). Brazil also features in South African Foreign Policy as a country with which to build and maintain co-operative ties, which the BRICS membership reinforces (Lalbahadur, Du Plessis and Grobbelaar 2015Lalbahadur, Aditi, Rudolp Du Plessis and Neuma Grobbelaar. 2015. South Africa’s foreign policy priorities for the 21st century: A closer look at the potential co-operation in the South Atlantic zone. South African Institute for International Affairs, written for Polity.org.za. 21 May. At http://www.polity.org.za/print-version/south-africas-foreign-policy-priorities-for-the-21st-century-a-closer-look-at-the-potential-for-co-operation-in-the-south-atlantic-zone-2015-05-21. [Accessed 23 May 2016].

http://www.polity.org.za/print-version/s...

: 3). For South Africa, it is about co-operation to counter maritime threats and piracy in particular, as well as access to the ocean economy. Both ideas aim at bringing the blue economy into the South African economic architecture in a more deliberate and structured way – but South Africa can do neither on its own (Lalbahadur, Du Plessis and Grobbelaar 2015Lalbahadur, Aditi, Rudolp Du Plessis and Neuma Grobbelaar. 2015. South Africa’s foreign policy priorities for the 21st century: A closer look at the potential co-operation in the South Atlantic zone. South African Institute for International Affairs, written for Polity.org.za. 21 May. At http://www.polity.org.za/print-version/south-africas-foreign-policy-priorities-for-the-21st-century-a-closer-look-at-the-potential-for-co-operation-in-the-south-atlantic-zone-2015-05-21. [Accessed 23 May 2016].

http://www.polity.org.za/print-version/s...

: 4). The more constructive side to this need is that South Africa, Brazil and countries along the south Atlantic coast all have overlapping needs in terms of more maritime security to draw more successfully upon the ocean economy. For both South Africa and Brazil, it is economics that forms the nexus amidst the growing interests in the oceans and what transpires on land (Lalbahadur, Du Plessis and Grobbelaar 2015Lalbahadur, Aditi, Rudolp Du Plessis and Neuma Grobbelaar. 2015. South Africa’s foreign policy priorities for the 21st century: A closer look at the potential co-operation in the South Atlantic zone. South African Institute for International Affairs, written for Polity.org.za. 21 May. At http://www.polity.org.za/print-version/south-africas-foreign-policy-priorities-for-the-21st-century-a-closer-look-at-the-potential-for-co-operation-in-the-south-atlantic-zone-2015-05-21. [Accessed 23 May 2016].

http://www.polity.org.za/print-version/s...

: 2). As a result the common threat landscape, mutual needs in terms of maritime security for safe and secure access to marine and other resources, safe maritime transport routes, and infrastructure, alongside both dormant and operational multilateral arrangements for co-operation, shape opportunities to secure the South Atlantic landscape.

A competitive Blue BRICS: advantages in the South Atlantic

The idea of a blue BRICS is not without its stumbling blocks and opposition. Whereas much of the above pertains to the softer security aspect of the BRICS maritime connection, a certain competition and even threat environment constituted by other state actors coexists with the co-operative security realm argued above.

China’s rise towards a future superpower holds disturbing indicators of possible military confrontation and one hardly exclusive of naval ambitions. Trade, growth, the role of maritime trade routes, and the rise of economic zones on the coast turned Chinese defence attention off-shore and the imperative to raise its naval profile in defence against aggression from the sea, protect national sovereignty, and safeguard maritime rights (Veen 2012Veen, Ed. 2012. The sea: Playground of the superpowers. On the maritime strategy of superpowers. The Hague Center for Strategic Studies. The Hague No 13/3/12.: 37; Kynge et al 2017). The Chinese Navy’s primary role is to deter or outfight threats to its national sovereignty, particularly to settle territorial disputes with neighbours in the South China Sea. However, protecting or defending its sea lines of communication that sustain its economic growth has become an important contemporary focus of naval attention, the absence of which could severely hamper progress of China’s naval profile (Veen 2013: 43). Exploiting the use of the sea in an uninterrupted manner thus serves as a self-sustaining process for the navy and the economy to promote China’s development. China, however, is slipping into an increasingly confrontational situation in the South China Sea and one strongly backed by Russia. Actions to press home its claims over contested waters show more aggressiveness that is bound to upset its UNCLOS stances, some Asian neighbours, and the USA (Guinto 2014Guinto, Joel. 2014. ‘China builds artificial islands in the South China Sea’. Bloomberg Business, 19 June. At http://www.bloomberg.com/bw/articles/2014-06-19/china-builds-artificial-islands-in-south-china-sea. [Accessed on 26 May 2015].

http://www.bloomberg.com/bw/articles/201...

). Within BRICS, China unfortunately also has a less than amicable relationship with India, the other rising power in BRICS, and one characterised by maritime competition. Then there is the 2015 Chinese fishing trawler incident in waters of South Africa, a fellow BRICS member, which resulted in the SA Navy entering the chase and fines imposed on the flotilla of Chinese vessels. The incident ironically coincided with a visiting Chinese naval task force arriving in Cape Town, South Africa.

India views stability in the Indian Ocean as a priority. India’s economic rise is sea dependent, its long coast line connecting with the Indian Ocean, which explains India’s focus on this particular ocean region. The Indian Navy serves to have a both foreign and onshore influence and to support a host of economic activities unfolding in the Indian Ocean. India’s view of keeping the Indian Ocean free of foreign influence and possible military confrontation is challenged by the roles of Pakistan and China and their intrusions into this maritime region (Veen 2013: 49). This competition with naval undertones holds an element of inter-BRICS tensions, but the Indian Ocean remains important for China, India, and South Africa through their physical littoral presence and geographical proximity, and for naval purposes. Unfortunately the Indian preference for the Indian Ocean as a neutral zone is contradicted by matters involving fellow BRICS members. The Pakistani–Indian rivalry now represents a Chinese intrusion as well. Along with Chinese ventures into the Indian Ocean through its String of Pearls strategy and Chinese naval task groups operating in China’s Far Seas (the Western Indian Ocean) this all contradicts the amicable face of BRICS that one finds at the annual BRICS Summits (Veen 2013: 49).

Finally, critics aver that BRICS is probably not the foremost strategic matter for its members. Nor will one find disproportionate time and national resources dedicated to BRICS matters. BRICS members are not overtly committed to revisionist collective action as the looseness or networked nature of BRICS and few binding rules to override complexities each member faces have become the reigning approach. Diversity rather than congruence characterises the political, economic, and social make-up of BRICS members and thus the looseness that one observes. The status quo of the international system is still beneficial to all (Stuenkel 2016Stuenkel, Oliver. 2016. ‘Book Review: “BRICS: A very short introduction” by Andrew F. Cooper’. Post-Western World, 6 August. At http://www.postwesternworld.com/2016/08/06/review-introduction-andrew/. [Accessed on 14 February 2017].

http://www.postwesternworld.com/2016/08...

), and given the focus of this article, this argument is equally relevant to the notion of a maritime BRICS where UNCLOS remains the norm (albeit contested at times) to guide how BRICS members decide to tap into the advantages on offer from its connecting oceans. The disequilibrium between BRICS members is perhaps least contentious between South Africa and Brazil across the South Atlantic and thus the leeway for co-operation on and across the sea. However, Brazil faces its own dilemmas ranging from critique of its foreign policy led even military-led drive into the south Atlantic to competition with BRICS members like China and India vying for position in Africa to its own limited capabilities and domestic pressures about its south Atlantic–Africa focus (Souza Neto 2013Souza Neto, Danilo Marcondes de. 2013. ‘Contemporary Brazil–Africa relations: Bilateral strategies and engagement with other BRICS.’ In Sven Grim (ed), The BRICS Summit 2013: Is the road from Durban leading to Africa? The China Monitor Special Edition. Centre for Chinese Studies, Stellenbosch, pp. 6–12.: 8–9).

In summary, the South Atlantic offers more indicators of stability for any notion of a blue BRICS. One must set the pessimism of the above against the absence of competitive and confrontational relations between BRICS members over the South Atlantic. The drive for co-operation and prevention, as well as building new partnerships to secure the South Atlantic, is perhaps the harbinger of the most stable sector of BRICS, and within its regions as well. In spite of domestic political disturbances in Brazil in particular noted by Seabra (2016Seabra, Pedro. 2016. Brazil as a Security Actor in Africa: Reckoning and Challenges ahead. GIGA Focus Latin America no. 7. German Institute of Global and Area Studies. December.: 5–7), South Africa, Brazil, and the South Atlantic also set the pace for the responsible and co-operative use of the ocean within the BRICS that aligns with thinking on how to exploit the oceans in a responsible and a sustainable manner. In this regard, the outreach to West Africa, and co-operation with India, recognises the importance of multilateralism in building a maritime zone of peace through physical, virtual and proxy measures.

Concluding remarks

BRICS has stimulated an ongoing debate about its future roles and impact in the international system. Much of the debate takes shape around its politico-economic influences, its rise as a counter to the international status quo, and how it could reconfigure matters directing the international system. BRICS also houses an important maritime domain in its geostrategic make-up, one remaining marginal in the debates that contemplate the role and influence of the BRICS grouping. Given its ocean territories that stretch from the Arctic Sea past China through the Indian Ocean to the South Atlantic off Brazil and South Africa, any discussion on the rise and influence of BRICS in the international system can hardly be credible if it excludes the maritime zones of BRICS.

In simple terms, the landward impression of BRICS upon analysts and decision-makers is augmented by the maritime nexus of BRICS through its location astride important ocean regions of the world. More important is how BRICS converts the latent economic potential housed in its maritime domains towards developmental outcomes in its respective member states. Of critical importance is whether BRICS can convert its envisaged economic influence that rests upon its access to and intelligent use of maritime assets to political power and influence in the international system in a collaborative way and steer away from competition and, in particular, confrontation. From the discussion, it appears that Brazil and South Africa’s co-operation in the South Atlantic holds the potential to secure this southernmost component of a blue BRICS in more amicable and collaborative ways than those found to the east in the Indian Ocean and confrontational actions in the Western Pacific. As for the latter, it is China with its challenges to reigning maritime regimes that appears as an important catalyst to upset the notion of a blue BRICS.

Notes

-

1

A sixth summit took place in Brazil (2014) and the Seventh in Russia during July 2015, when discussions around the New Development Bank seems to have dominated the agenda.

-

2

These summits took place in Russia (2009), Brazil (2010), China 2011, India (2012), South Africa (2013).

-

3

IBSA: an international grouping to promote international co-operation between Brazil, India, and South Africa. IBSAMAR: a series of naval exercises between Brazil, India, and South Africa.

-

4

Angola, Botswana, DR Congo, Lesotho, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Madagascar, Namibia, Seychelles, South Africa, Swaziland, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

-

5

Maritime sovereignty is not akin to that on land and is more circumscribed by the law of the sea. Article 2, Part 2 of UNCLOS frames different maritime zones and countries have different rights and responsibilities over maritime zones as territorial seas, economic zones, and the high seas. Littoral countries have territorial waters of 12 nm over which they have sovereignty and rights akin to their landward sovereignty. Littoral countries also have the right to claim up to 120 nm as their EEZ, and this claim must be recognised or contested in court by other countries, but UNCLOS determines country rights and responsibilities, as it does for the high seas.

-

6

Ocean governance refers to the rights and obligations of state parties to attend to their rights and obligations in the oceans and in particular as outlined by UNCLOS. Of particular importance are matters related to the sustained and responsible use of the oceans, its importance to world futures, and oceans also becoming problem areas that must be policed, managed and resolved.

-

7

The rationalist framework promotes co-operation or the potential for co-operation between states as opposed to competition and power balances based upon coercion or the threat thereof promoted by the more realist theories.

-

8

Chinese naval presence in the Western Indian Ocean emanates primarily from a direct threat to Chinese shipping and trade transiting the Western Indian Ocean. As for the South Atlantic, Chinese interests are more akin to supporting Chinese Multi-National Corporations, Chinese outlook of (Chinese) people first, investment protection, and promoting security as part of the Chinese and BRICS interests in Africa.

References

- Abdenur, Adriana and Danilo Marcondes de Souza Neto. 2013a. Brazil’s maritime strategy in the south Atlantic. The nexus between security and resources. Occasional Paper no 161. Global Powers and Africa Programme, South African institute of International Affairs. November.

- Abdenur, Adriana and Danilo Marcondes de Souza Neto. 2013b. ‘Brazil’s maritime strategy in the South Atlantic: The nexus between security and resources’. In International Security: Brazil Emerging in the Global Security Order. Konrad Adenauer Stiftung. 28 November: 173–184.

- Bateman, Sam Joshua Ho and Jane Chan. 2009. Good order at sea in Southeast Asia. RSISS Policy Paper. S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, April, p. 7.

- Bateman, Sam. 2016. ‘Maritime security governance in the Indian Ocean’. Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, 12(1): 6.

- Bertelsmann Stiftung. 2012. Governance capacities in the BRICS. Sustainable governance indicators. Gutersloh (Germany): Bertelsmann Stiftung.

- Borchard, Heiko. 2014. Maritime security at risk. Trends, future threat vectors and capability requirements. Lucerne: Sandfire.

- Boulle, Laurence and Jessie Chella. 2014. ‘The case of South Africa’. In Vai Io Lo and Mary Hiscock (eds), The Rise of the BRICS in the Global Political Economy: Changing Paradigms? Joining the BRICs. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 99–122.

- Bueger, Christian. 2013. ‘Communities of security practice at work? Emerging African maritime security regime’. African Security, 6(3-4): 297-316.

- Bueger, Christian. 2015. ‘From dusk to dawn. Maritime domain awareness in South East Asia’. Contemporary Southeast Asia, 37(2): 157–182.

- Bueger, Christian and Anna Leander 2014. Technological solutions to the piracy problem: Lessons learned from counter-piracy off the Horn of Africa, Piracy-Studies.Org, Research Portal for Maritime Security, Copenhagen Business School, 26 May 2014. At http://piracy-studies.org/2014/technological-solutions-to-the-piracy-problem-lessons-learned-from-counter-piracy-off-the-horn-of-africa/. [Accessed on 25 February 2015].

» http://piracy-studies.org/2014/technological-solutions-to-the-piracy-problem-lessons-learned-from-counter-piracy-off-the-horn-of-africa/. - Buzan, Barry. 1991. People States and Fear: An Agenda for International Security Studies in the post-Cold War Era. New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- Coning, Cedric Thomas Mandrup de and Liselotte Odgaard (eds). 2015. The BRICS and Coexistence. An Alternative Vision of World Order. Oxon: Routledge.

- Chun, Zhang. 2013. ‘A promising partnership between BRICS and Africa: A Chinese perspective.’ In Sven Grim (ed), The BRICS Summit 2013: Is the road from Durban leading to Africa? The China Monitor Special Edition. Centre for Chinese Studies, Stellenbosch, pp. 30–37.

- DefenceWeb. 2014. ‘Africa’s West Coast is next Navy anti-piracy deployment’. 25 September. At http://www.defenceweb.co.za/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=36370&catid=108&Itemid=233. [Accessed on 23 May 2016].

» http://www.defenceweb.co.za/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=36370&catid=108&Itemid=233. - Department of Defence of South Africa (RSA). 2014. South African Defence Review 2014. 25 March.

- Department of Defence of South Africa (RSA). 2011. Address by L N Sisulu, (MP) minister of defence and military veterans at the SADC extraordinary meeting on regional anti-piracy strategy. 25 July.

- Guinto, Joel. 2014. ‘China builds artificial islands in the South China Sea’. Bloomberg Business, 19 June. At http://www.bloomberg.com/bw/articles/2014-06-19/china-builds-artificial-islands-in-south-china-sea. [Accessed on 26 May 2015].

» http://www.bloomberg.com/bw/articles/2014-06-19/china-builds-artificial-islands-in-south-china-sea. - Herbert-Burns, Rupert, Sam Bateman and Peter Lehr (eds). 2009. Lloyds MIU Handbook of Maritime Security. Boca Raton FL: CRC Press.

- Hiscock, Mary and Io Ho, 2014. ‘Conclusions: The BRICS ascending, decline or plateau?’ In Io Ho and Mary Hiscock (eds), The rise of BRICS in the global political economy: Changing paradigms. Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 308-312.