CASE REPORT

Fractures in connection with an atypical form of craniodiaphyseal dysplasia: case report of a boy and his mother

Ali Al KaissiI,II; Robert CsepanII; Jochen G. HofstaetterIII; Klaus KlaushoferI; Rudolf GangerII; Franz GrillII

IHanusch Hospital of WGKK and AUVA Trauma Centre Meidling, First Medical Department, Ludwig Boltzmann Institute of Osteology, Viena, Austria

IIOrthopaedic Hospital of Speising, Paediatric Department, Vienna, Austria

IIIMedical University of Vienna, Vienna General Hospital, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Vienna/Austria

INTRODUCTION

Craniodiaphyseal dysplasia is a severe disorder characterized by distinctive facial dysmorphisms, including prominent zygomatic bones, broadening of the center of the face, hypertelorism, a small upturned tip of the nose and massive hyperostosis and sclerosis of the skull and facial bones. The sclerosis is severe and is referred to as ''leontiasis ossea'' (leonine faces), and the bone deposition causes progressive stenosis of the craniofacial foramina (1-5).

The skull and facial hyperostosis result in an increasing head circumference, paranasal bossing, nasal bridge distortion and an alteration in the orbital alignment. Radiographic features consist of osteosclerosis and hyperostosis of the skull and facial bones and, to a lesser degree, the diaphyses of the tubular bones. There is often secondary optic atrophy and deafness, and epilepsy and mental retardation have both been reported (6,7).

Familial osteoectasia with macrocranium and hyperphosphatasia are features encountered in juvenile Paget's disease (juvenile deforming cortical hyperostosis) (7). Genotypical diseases of familial osteoectasia are characterized by Cushingoid facies, limb deformities (from generalized osteoporosis) and retarded growth (8,9).

CASE DESCRIPTION

Patient I

A two-year-old boy was referred to our department because of a distal diaphyseal fracture of the left femur. He was the first child of non-consanguineous parents. At birth, his weight, length and OFC were at approximately the 25th percentile. His mother was a 26-year-old primagravida with no history of spontaneous abortions, stillbirths or neonatal mortalities who was married to a 27-year-old unrelated man.

At birth, the child presented with plagiocephaly for which he was treated with a cranial band (Care band); he wore this for 23 hours per day until the age of one year. At that time, no skull radiographs were taken, and the pediatricians considered his case to be a deformational non-syndromic plagiocephaly.

His subsequent course of development included motor delay, although other developmental skills were within the normal range. There was no history of visual, auditory or other neurological symptoms. There was no history of anorexia, weight loss or muscular hypotonia.

Examination at the age of two years showed a pleasant boy with mild and unnoticeable facial dysmorphic features, with frontal bossing and slight facial asymmetry associated with incomplete auricular folding. Leontiasis ossea and or Cushingoid facies/macrocephaly, retarded growth and muscular hypotonia were not evident (Table 1).

Neurological, ophthalmological, and auditory evaluations were normal, and there was no history of seizures or non-motor developmental delay. Audiometric evaluation excluded peripheral hearing loss. Ophthalmological examination revealed normal vision with no strabismus or other eye problems. Musculo-skeletal examination revealed relative ligamentous hyperlaxity associated with patellar instability. Thoraco-lumbar scoliosis of 32 degrees was evident.

A skeletal survey was conducted at the age of two years. A lateral skull radiograph showed marked cranial osteosclerosis and hyperostosis; the facial bones and base of the skull were severely hyperostosed. An anteroposterior skull radiograph showed facial bone hyperostosis (Figure 1). An anteroposterior radiograph of the thorax showed thick, broad and sclerosed ribs; the medial two-thirds of the clavicles were hyperostosed; thoraco-lumbar scoliosis of 32 degrees was present secondary to hemivertebrae along T8-10, and only 11 ribs were present (Figure 2A).

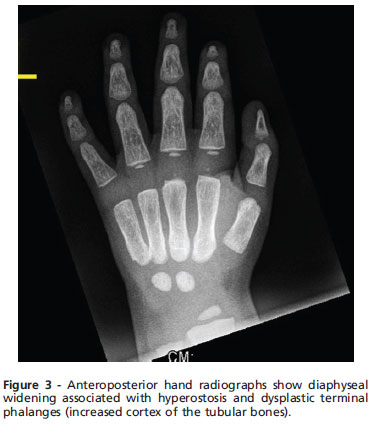

Anteroposterior radiographs of the pelvis and the femora revealed diaphyseal hyperostosis associated with distal diaphyseal fracture of the left femur and a stress/fatigue fracture of the mid-diaphysis of the right femur (Figure 2B). An anteroposterior hand radiograph showed diaphyseal widening associated with hyperostosis and dysplastic terminal phalanges (increased cortex of the tubular bones) (Figure 3). CT imaging was planned to further delineate additional abnormalities. Axial reformatted CT scans revealed bilateral narrowing of the optic canal (Figure 4).

Other investigations included an abdominal ultrasound and metabolic tests to examine calcium, phosphorous, and vitamin B metabolism, which were normal; normal karyograms for the parents and the proband were also obtained. Nevertheless, the alkaline phosphatase level was five times greater than normal in the proband. Hormonal investigations included thyroid, adrenocorticotropic and growth hormones, all of which were normal. We treated the diaphyseal fractures via spica casting.

Patient II

A 26-year-old-woman (the mother of patient I) had a history of a diaphyseal fracture of the right femur a few years prior with appropriate operative treatment. On examination, she manifested mild facial features similar to those seen in patient I, including frontal bossing and a wide frontal area with a depressed nasal bridge and a large nose. She also presented with incomplete folding of the external ears, similar to that noted in patient I. Her family history was unremarkable. An anteroposterior lower extremity (retrospective) radiograph showed mild diaphyseal hyperostosis associated with a mid-diaphyseal fracture and locked intramedullary nailing (Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

Craniotubular dysplasias such as CDD are characterized by severe condensing hyperostosis of the craniofacial skeleton and the diaphyses of the long bones, along with short stature, mental retardation and an unfavorable prognosis. The main clinical feature is macrocephaly (dolichocephaly) (1-4). The characteristic leonine appearance is due to marked thickening of the cranial, nasal, and maxillary bones (5); other features include a high forehead, prominent zygomatic bones, broadening of the center of the face, hypertelorism, exophthalmos, strabismus, a small upturned tip of the nose, a prominent jaw, an open-mouth nasal obstruction, a prominent mandible, dental malocclusion, and compression of the cranial nerves leading to progressive loss of vision and hearing. Distinctive radiographic features include marked thickening and sclerosis of the cranial and facial bones with obliteration of the paranasal sinuses and mastoid cells. There is also increased density of the vertebral arches and thickening and diffuse sclerosis of the clavicles and, to a lesser extent, the ribs. In the pelvis, there is some sclerosis of the sacroiliac joints. In the limbs, a homogeneous opacity of the diaphyses of the long bones, which have a cylindrical appearance due to cortical thickening, is often observed. The small tubular bones of the hands and feet are also involved (6,7).

Idiopathic hyperphosphatasia (IH) is a metabolic bone disease characterized by increased bone resorption by osteoclasts due to an increase their number, size and resorbing activity. The disease starts with a lytic phase, which is followed by compensatory increased activity of osteoblasts (sclerotic phase). The bone turnover rate progressively increases, reaching up to 20 times the normal levels. This results in increased bone formation, in which the resulting bone is weaker highly vascular and disorganized (9). Increased alkaline phosphatase does not imply that the disease is due to excess enzyme; in fact, the cause of the lack of primary bone transformation into mature lamellar bone is unknown. Idiopathic hyperphosphatasia is characterized by increased serum alkaline phosphatase [5-20 times greater than normal]. Increased acid phosphatase is also observed, but it is less marked and is an inconsistent finding (10). A diagnosis of IH is ultimately made through imaging and laboratory findings. Radioisotope bone scanning is the most sensible method for detecting early lesions. The disease etiology remains uncertain, but genetic, environmental and viral infections are considered the most likely causes (11).

The differential diagnosis of our patient includes other forms of cranio-tubular dysplasias, such as CDD, craniometaphyseal dysplasia, Camurati-Engelmann disease, Worth type endosteal hyperostosis, Van Buchem disease, sclerosteosis, Lenz-Majewski syndrome, hyperostosis, dysplasia, and IH (7). We postulate that our current patient and his mother manifest a variant of cranio-tubular dysplasia that is consistent with but not diagnostic for CDD.

Sclerosing bone disorders can be subdivided according to their clinical and radiological presentations, the primary affected cell type and the cellular pathways involved. Osteoclast-rich osteopetrosis and related disorders have been related in most cases to mutations in genes required for osteoclast function. More recently, osteoclast-poor forms of osteoporosis have been described as being connected to factors that govern osteoclast differentiation.

Osteosclerosis and hyperostosis in the long bones refer to trabecular and cortical thickening, respectively. Similarly, cranial hyperostosis describes an enlargement of the affected skull bones, while in cranial sclerosis, the bones appear more radio-opaque but are of normal size. Because high bone mass can arise from either reduced bone resorption or increased bone formation, the sclerosing bone disorders can be subdivided into osteoclast and osteoblastrelated entities. Increased bone mass is often a diagnostic challenge. In the absence of an obvious hereditary context, osteocondensation secondary to a concomitant pathology, particularly to a neoplastic disorder, should be excluded (12).

Kim et al. recently discovered mutations c.61G>A (Val21Met) and c>61G.T (Val21Leu) in two children with CDD and concluded that CDD is the most severe form of sclerotic bone disease, and it is part of a spectrum of disease caused by mutations in SOST (13). None of the above-mentioned reports described femoral fractures as a presenting abnormality in patients with CCD.

The blood supply of the femoral shaft is from both endosteal and periosteal blood vessels. The endosteal supply is typically derived from two nutrient vessels that enter the femur from a posteromedial direction. The periosteal capillaries supply the outer 25%-30% of cortical bone and are most prominent in the areas of muscular attachments to the femoral shaft. These two circulatory systems, together with the metaphyseal complex of vessels, are interconnected to provide a strong vascular supply that allows rapid fracture repair (14,15).

Cranio-tubular dysplasias include a wide variety of symptoms and vary in their age of onset from infancy to childhood. Interestingly, neither the proband nor his mother showed the typical characteristic phenotypic features of CDD, IH or any other form of cranio-tubular dysplasias/dysostosis.

Finally, we wish to stress that an etiological understanding of patients with unusual or atypical phenotypic and skeletal abnormalities, in combination with an assimilation of the natural history of the disease, are the cornerstones that allow the orthopedic surgeons, radiologists, physicians and neurologists to intervene on the affected areas and provide appropriate care for the patient.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank our colleagues at the European Skeletal Dysplasia Panel and Prof. Andrea Superti-Furga Leenaards, Professor of Pediatrics, University of Lausanne, Medecin-chef and Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois (CHUV) for their continuous help and support. Accredited site for registration: Our clinical research is registered with the Medical University of Vienna (EK Nr.921/2009).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Kaissi AA, Ganger R, Grill F drafted the manuscript and analyzed the data. Csepan R and Klaushofer K participated in the coordination of the study. Hofstaetter JG participated in the coordination and design. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

Email: ali.alkaissi@osteologie.at

Tel.: +43 01 80 182

- 1. Halliday J. A rare case of bone dystrophy. Br J Surg. 1949;37(145):52-63.

- 2. Gorlin RJ, Spranger J, Koszalka MF. Genetic craniotubular bone dysplasias and hyperostoses: a critical analysis. BDOAS. 1969;5(4):79-95.

- 3. Brueton LA, Winter RM. Cardiodiaphyseal dysplasia. J Med Genet. 1990;27(11):701-6, http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jmg.27.11.701

- 4. Gorlin RJ. Craniotubular bone disorders. Pediatr Radiol. 1994;24(6):392-406, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02011904

- 5. De Souza O. Leontiasis ossea. Porto Alegre (Brazil), Faculdade de Medic Rev. Dos Cursos. 1927;13:47.

- 6. Kirkpatrick DB, Rimoin DL, Kaitila I, et al. The craniotubular bone modelling disorders: a neurosurgical introduction to rare skeletal dysplasias with cranial nerve compression. Surg Neurol. 1977;7(4):221-32.

- 7. Spranger JW, Brill PW, Poznanski A. 2000. Bone dysplasias. An atlas of genetic disorders of skeletal development. 2nd ed. New York, Oxford University Press, 2002.

- 8. Lancu TC, Almagor G, Friedman E, Hardoff R, Front D. Chronic familial hyperphosphatasemia. Radiology. 1978;129(3):669-76.

- 9. Moncrieff AA. A chronic progressive osteopathy with hyperphosphatasia. Proc R Soc. Med. 1962;55:238-9.

- 10. Moncrieff AA. A chronic progressive osteopathy with hyperphosphatasia. 1962. Proc R Soc. Med. 55:238-9.

- 11. Joshi SR, Ambbore S, Butala N, Patvardhan M,Kulkarni M, Pai B, et al. Paget' disease fromWestern India. J Assoc Physicians India. 2006;54:535-8.

- 12. Josse RG, Hanley DA, Kendler D, Ste Marie LG, Adachi JD, Brown J. Diagnosis and treatment of Paget's disease of bone. Clin Invest Med. 2007;30(5):210-23.

- 13. Marie-Christine de Vernejoul and Uwe Kornak. Heritable sclerosing bone disorders Presentations and new molecular mechanisms. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1192:269-77, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05244.x

- 14. Kim SJ, Bieganski T, Sohn YB, Kozlowski K, Semënov M, Okamoto N, et al. Identification of signal peptide domain SOST mutations in autosomal dominant craniodiaphyseal dysplasia. Hum Genet. 2011;129(5):497-502, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00439-011-0947-3

- 15. Aiello LC, Dean C. An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy. London: Academic Press; 1990.

- 16. Loder RT, O'Donnell PW, Feinberg JR. Epidemiology and mechanisms of femur fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26(5):561-6.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

02 Jan 2013 -

Date of issue

Dec 2012