Abstract

Objective:

This study describes a quantitative and qualitative methodology to assess hedonic responses to sweet stimulus in healthy newborns.

Methods:

A descriptive, cross-sectional, observational study, with healthy newborns (up to 24 h of life), between 37 and 42 gestational weeks, vaginally born and breastfed previously to all tests. The evaluation of the newborns reactions was performed by hedonic facial expression analysis, characterized by facial expressions with rhythmic serial tongue protrusion after neutral or sweet solution intake. Initially, 1 mL of water solution was provided to the newborn, followed by a 1-minute recording. Afterwards, the same amount of 25% sucrose solution was provided, performing a second recording. The concordance between researchers was analyzed by the Bland-Altman statistical method.

Results:

A total of 100 newborns (n = 49 males, n = 51 females; mean lifetime = 15 h 12 min ± 6 h 29 min) were recorded for neutral and sucrose solution intake, totaling 197 videos (n = 3 missing in the water treatment). These videos were double-blind analyzed and the test revealed a 90% concordance between the two trained researchers, in relation to both solutions. The intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.99 for both solutions, with a significant increase in frequency of hedonic expressions evoked by sucrose solution intake.

Conclusions:

These results confirm that the proposed method has an efficient power to detect significant differences between neutral and sucrose stimuli. In conclusion, this evaluation method of hedonic facial reactions in newborns reflects the response to a specific taste.

KEYWORDS

Newborn; Facial expression; Sucrose

Resumo

Objetivo:

Descrever quantitativamente e qualitativamente uma metodologia para avaliar as respostas faciais hedônicas, em recém-nascidos saudáveis, ao estímulo doce.

Métodos:

Trata-se de um estudo descritivo, transversal e observacional, com recém-nascidos saudáveis (com até 24 horas de vida), entre 37-42 semanas gestacionais, nascidos por parto vaginal e alimentados previamente aos testes. A avaliação das reações hedônicas dos recémnascidos foi considerada pelas expressões faciais com séries rítmicas de protrusões de língua após a ingestão de solução neutra ou doce. Inicialmente, 1 mL de solução neutra (água) foi fornecida para o recém-nascido, seguido de uma filmagem de 1 minuto. Sequencialmente, a mesma quantidade de solução de sacarose 25% foi fornecida, realizando-se uma segunda gravação. A concordância entre os pesquisadores foi analisada pelo método estatístico de Bland-Altman.

Resultados:

Um total de 100 recém-nascidos (n = 49 do sexo masculino, n = 51 do sexo feminino, tempo de vida média = 15 h 12 min ± 6 h 29 min) foram registrados para a ingestão de solução neutra e de sacarose, totalizando 197 vídeos (n = 3 perdas para o tratamento água). Estes vídeos foram analisados em duplo-cego e o teste revelou uma concordância de 90%, para ambas as soluções, entre os pesquisadores treinados. O coeficiente de correlação intraclasse foi de 0,99 para as duas substâncias, com um aumento significativo nas frequências das expressões faciais hedônicas evocadas pela ingestão de sacarose.

Conclusões:

Estes resultados confirmam que o método proposto possui poder estatístico eficiente para detectar diferenças entre estímulos neutros e sacarose. Em conclusão, este método de avaliação de reações faciais hedônicas em recém-nascidos reflete a resposta para um gosto específico.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Recém-nascido; Expressão facial; Sacarose

Introduction

Evidence suggests that affective reactions reflect the quality of pleasant or unpleasant events, since newborns have essentially two patterns of facial expressions to taste: positive emotional reaction - hedonic, or negative emotional reaction - disgust. The sweet taste of sugar usually draws positive affective patterns, such as a "nozzle" lip-shape and a rhythmic series of tongue protrusion movements. These movements are accompanied by relaxation of facial muscles.11 Steiner JE, Glaser D, Hawilo ME, Berridge KC. Comparative expression of hedonic impact: affective reactions to taste by human infants and other primates. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2001;25:53-74. Some studies have reported that the experience of a taste during intrauterine life could improve the acceptance of foods with the same taste in childhood.22 Mennella JA. Flavour programming during breast-feeding. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;639:113-20.

3 Mennella JA, Pepino MY, Reed DR. Genetic and environmental determinants of bitter perception and sweet preferences. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e216-22.

4 Mennella JA, Griffin CE, Beauchamp GK. Flavor programming during infancy. Pediatrics. 2004;113:840-5.-55 Mennella JA, Jagnow CP, Beauchamp GK. Prenatal and postnatal flavor learning by human infants. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E88. The automatic responses to stimulus can be innate, such as in sweet taste,66 Beauchamp GK, Moran M. Dietary experience and sweet taste preference in human infants. Appetite. 1982;3:139-52. and may change during the course of life, depending on the type of in utero exposure, among other factors before and after birth.22 Mennella JA. Flavour programming during breast-feeding. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;639:113-20.,77 Beauchamp GK, Mennella JA. Early flavor learning and its impact on later feeding behavior. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:S25-30. The child's facial expression resulting from a sweet taste is an example of a positive affective reaction behavior.11 Steiner JE, Glaser D, Hawilo ME, Berridge KC. Comparative expression of hedonic impact: affective reactions to taste by human infants and other primates. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2001;25:53-74.,88 Steiner JE. The gustofacial response: observation on normal and anencephalic newborn infants. Symp Oral Sens Percept. 1973;:254-78. In addition, hedonic expressions reflect the activity of specific mesolimbic systems,99 Peciña S, Smith KS, Berridge KC. Hedonic hot spots in the brain. Neuroscientist. 2006;12:500-11. which are also activated after visualization of tasty foods.1010 Volkow ND, Fowler JS. Addiction, a disease of compulsion and drive: involvement of the orbitofrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:318-25. As variations in this circuit's responsiveness may predict the risk for weight gain,1111 Stice E, Yokum S, Bohon C, Marti N, Smolen A. Reward circuitry responsivity to food predicts future increases in body mass: moderating effects of DRD2 and DRD4. Neuroimage. 2010;50:1618-25. behavioral alterations could also indicate a risk for overeating and/or overweight in the future.

There are different methods in the literature to evaluate the hedonic responses to gustatory stimuli in children. In the early 1970s, Steiner was the pioneering author in studies about affective reactivity with the publication of illustrations of the facial reactions in newborns evoked by the sweet, salty, sour, and bitter tastes.88 Steiner JE. The gustofacial response: observation on normal and anencephalic newborn infants. Symp Oral Sens Percept. 1973;:254-78.,1212 Steiner JE. Discussion paper: innate, discriminative human facial expressions to taste and smell stimulation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1974;237:229-33. In 1976, Crook and Lipsitt conducted four experiments about the effects of brief intraoral fluid stimulation upon the non-nutritive sucking rhythm of newborns.1313 Crook CK, Lipsitt LP. Neonatal nutritive sucking: effects of taste stimulation upon sucking rhythm and heart rate. Child Dev. 1976;47:518-22. Beauchamp and Moran, in 1982, studied the sucrose preference at birth determined by allowing ad libitum consumption of sucrose and water solutions during brief presentations, according to the dietary record.66 Beauchamp GK, Moran M. Dietary experience and sweet taste preference in human infants. Appetite. 1982;3:139-52. Ganchrow et al., in 1983, evaluated newborns' facial expressions recorded by video after oral stimulation with distilled water and sucrose, urea, and quinine hydrochloride.1414 Ganchrow JR, Steiner JE, Daher M. Neonatal facial expressions in response to different qualities and intensities of gustatory stimulation in response to different qualities and intensities of gustatory stimuli. Infant Behav Dev. 1983;6:473-84. In 1988, Rosenstein and Oster evaluated videotaped facial expressions based on the Facial Action Coding System adapted for infants (Baby FACS) evoked by sucrose, sodium chloride, citric acid, and quinine hydrochloride.1515 Rosenstein D, Oster H. Differential facial responses to four basic tastes in newborns. Child Dev. 1988;59:1555-68. In 1993, Porges and Lipsitt analyzed the gustatory-vagal hypothesis regarding neonatal responsivity to gustatory stimulation.1616 Porges SW, Lipsitt LP. Neonatal responsivity to gustatory stimulation: the gustatory-vagal hypothesis. Infant Behav Dev. 1993;16:487-94. In this sense, taste reactivity research demonstrated that sucrose evoked hedonic patterns (e.g., lip smacking and rhythmic series of tongue protrusion, accompanied by relaxation of the facial muscles and an occasional smile).11 Steiner JE, Glaser D, Hawilo ME, Berridge KC. Comparative expression of hedonic impact: affective reactions to taste by human infants and other primates. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2001;25:53-74.,1717 Berridge KC. Measuring hedonic impact in animals and infants: microstructure of affective taste reactivity patterns. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:173-98.,1818 Smith KS, Berridge KC. Opioid limbic circuit for reward: interaction between hedonic hotspots of nucleus accumbens and ventral pallidum. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1594-605. Recently, in 2015, Zacche Sa et al. analyzed facial responses to basic tastes among newborns of women with and without gestational diabetes mellitus.1919 Zacche Sa A, Silva JR, Alves JG. Facial responses to basic tastes in the newborns of women with gestational diabetes mellitus. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:1687-90. Some of these studies recorded facial expressions through filming techniques, allowing a precise evaluation of the frequency of hedonic and aversive reactions, as well as its duration. Of all the aforementioned research, some of these investigations11 Steiner JE, Glaser D, Hawilo ME, Berridge KC. Comparative expression of hedonic impact: affective reactions to taste by human infants and other primates. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2001;25:53-74.,88 Steiner JE. The gustofacial response: observation on normal and anencephalic newborn infants. Symp Oral Sens Percept. 1973;:254-78.,1212 Steiner JE. Discussion paper: innate, discriminative human facial expressions to taste and smell stimulation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1974;237:229-33.,1414 Ganchrow JR, Steiner JE, Daher M. Neonatal facial expressions in response to different qualities and intensities of gustatory stimulation in response to different qualities and intensities of gustatory stimuli. Infant Behav Dev. 1983;6:473-84.

15 Rosenstein D, Oster H. Differential facial responses to four basic tastes in newborns. Child Dev. 1988;59:1555-68.-1616 Porges SW, Lipsitt LP. Neonatal responsivity to gustatory stimulation: the gustatory-vagal hypothesis. Infant Behav Dev. 1993;16:487-94.,1919 Zacche Sa A, Silva JR, Alves JG. Facial responses to basic tastes in the newborns of women with gestational diabetes mellitus. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:1687-90. can be compared to the present manuscript. However, this study methodologically resembles only that of Ganchrow et al. in 1983, with a larger sample size.1414 Ganchrow JR, Steiner JE, Daher M. Neonatal facial expressions in response to different qualities and intensities of gustatory stimulation in response to different qualities and intensities of gustatory stimuli. Infant Behav Dev. 1983;6:473-84. It is noteworthy that in all these comparative studies, there was no report of statistical analysis between the two researchers. In this sense, this research aimed to describe a quantitative and qualitative methodology able to assess the hedonic responses to sweet stimulus in healthy newborns analyzed by double-blinded, trained researchers, using the Bland-Altman statistical method.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional, observational study, presenting a descriptive manuscript focusing on an adapted method from studies by Berridge, Steiner, and Ganchrow11 Steiner JE, Glaser D, Hawilo ME, Berridge KC. Comparative expression of hedonic impact: affective reactions to taste by human infants and other primates. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2001;25:53-74.,1414 Ganchrow JR, Steiner JE, Daher M. Neonatal facial expressions in response to different qualities and intensities of gustatory stimulation in response to different qualities and intensities of gustatory stimuli. Infant Behav Dev. 1983;6:473-84.,1717 Berridge KC. Measuring hedonic impact in animals and infants: microstructure of affective taste reactivity patterns. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:173-98. to assess the facial reactions to sweet taste in newborns. Data was collected from November 2010 to May 2012, in a hospital (Grupo Hospitalar Conceição - GHC) located in Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, which assists the Unified Health System.

The convenience sample included only healthy newborns, up to 24 h of life, at 37-42 gestational weeks, vaginally delivered and breastfed before all treatments. Children of mothers who did not sign the informed consent, cases of maternal diseases (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, HIV), and newborns who were not exclusively breastfed were excluded from sample. Maternal and newborn data were collected from medical records and from the prenatal child health handbook.

All procedures performed in this study involved human participants and were in accordance to the ethical standards of GHC research Ethics Committee and to the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments.

Hedonic reactions or positive emotional facial reactions

The newborns' positive affective facial reaction assessments were performed by hedonic facial expression analysis, characterized by serial and rhythmic tongue protrusion through fresh or neutral solution intake.11 Steiner JE, Glaser D, Hawilo ME, Berridge KC. Comparative expression of hedonic impact: affective reactions to taste by human infants and other primates. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2001;25:53-74.,88 Steiner JE. The gustofacial response: observation on normal and anencephalic newborn infants. Symp Oral Sens Percept. 1973;:254-78.,1212 Steiner JE. Discussion paper: innate, discriminative human facial expressions to taste and smell stimulation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1974;237:229-33.

Initially, 1 mL of neutral solution (deionized water) was provided to the newborn, followed by a 1 min recording. After this first recording, a second filming was performed after 1 mL of water + 25% sucrose solution was administrated. It is emphasized that the neutral solution was first provided to all newborns, and that sucrose recordings were performed only after water testing. All solutions were administrated orally, pressing the newborns' masseter muscle lightly, opening their mouths and allowing administration. The facial expressions were recorded continuously through 1 min, with a 20-cm distance between the camera and the newborn, under natural light inside the hospital room.

A Cyber-Shot DSC-S500 camera (Sony®, Tokyo, Japan), with 6.0 mega pixels and 30 frames per second, was used for recording all tests. Newborns were placed in a comfortable position, without crying, near their mothers. Before water recordings, they were previously breastfed. After the tests, mothers were oriented toward the practice of newborn oral care, as well as encouraged to practice exclusive breastfeeding through explanations of its importance and benefits for both the mother and the baby.

Solutions

Deionized water was used as a neutral solution and the sucrose solution was composed of 1 mL of deionized water containing 0.25 g of sucrose - modified from Steiner et al. in 2001 and Ayres et al. in 2012.11 Steiner JE, Glaser D, Hawilo ME, Berridge KC. Comparative expression of hedonic impact: affective reactions to taste by human infants and other primates. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2001;25:53-74.,2020 Ayres C, Agranonik M, Portella AK, Filion F, Johnston CC, Silveira PP. Intrauterine growth restriction and the fetal programming of the hedonic response to sweet taste in newborn infants. Int J Pediatr. 2012;2012:6573-9.

Solutions were produced by a compounding pharmacy. The deionized water was subjected to three purification processes: sediment removal, bacteria elimination, and total elimination of micronutrients. All solutions were individually packaged in a bottle dropper; labeled with the name of the solution, quantity, and expiry date; and finally sealed and individually wrapped in a plastic bag. These solutions were produced daily and delivered on the same morning, since data collection was performed in the afternoons. In this interval, all solutions were kept under refrigeration at 2-8 °C, as their validity was restricted to 24 h after preparation. If not used during this period, solutions were discarded. All recipients were opened in the presence of the mother, immediately prior to the testing moment. At the testing time, they were kept at room temperature (between 15 °C and 25 °C).

Video analysis

All 1-minute videos were firstly analyzed at a normal speed by two trained researchers, to verify whether there were hedonic facial expressions during the one-minute recording. Later, all records were evaluated frame-by-frame using Windows Media Player software (Microsoft®, WA, USA), slowing the speed to better detect hedonic facial expressions. Every second was composed of 30 frames, totalling 1800 frames per 60 seconds. The frequency of facial reactions in 2-s intervals was recorded for 1 min of continuous shooting. Facial expressions representing hedonic reactions or positive affective reactions were considered. For example, for each hedonic facial expression or tongue protrusion, a frequency was registered. For the analysis of these results, the sums of all 60-s records were calculated.11 Steiner JE, Glaser D, Hawilo ME, Berridge KC. Comparative expression of hedonic impact: affective reactions to taste by human infants and other primates. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2001;25:53-74.,1717 Berridge KC. Measuring hedonic impact in animals and infants: microstructure of affective taste reactivity patterns. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:173-98.

Hedonic reactions were characterized by facial expressions such as lip suctions and rhythmic tongue-protrusion movements.88 Steiner JE. The gustofacial response: observation on normal and anencephalic newborn infants. Symp Oral Sens Percept. 1973;:254-78. Videos were analyzed by two double-blinded, trained researchers, both trained by another researcher who had already used this technique.

Sample size estimation

Martin Bland and Doug Altman, authors of the statistical test to assess agreement between evaluators (concordance analysis using the Bland-Altman method), state that for an adequate accuracy it is important to evaluate 100 individuals, corresponding to a 95% confidence interval and a 0.34 standard error of deviation.2121 Bland JM, Altman DG. Agreed statistics: measurement method comparison. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:182-5.

Statistical methods

Symmetric data were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) and asymmetric data were expressed as median and interquartile ranges. To evaluate the agreement between the two raters, a concordance between Bland-Altman method was applied. This methodology evaluates the correlation between two variables (X and Y) starting from a graphical view based on a scatter plot of the difference of the two variables (X − Y) and their average (X + Y/2). In this chart, it is possible to visualize the bias (how the differences derivate from zero), the error (dispersion of the points around the mean), the outliers, and possible trends.2121 Bland JM, Altman DG. Agreed statistics: measurement method comparison. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:182-5. In order to complement these analyses, an intraclass coefficient (ICC) was also estimated. To compare the frequency of hedonic facial expressions, values evoked by water and sucrose solutions were analyzed by the Wilcoxon test. All data were evaluated using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, Inc. version 18.0, IL, USA), version 18.0. The level of significance was set at 5% for all analyses.

Results

The newborns' average life was 15 h 12 min ± 6 h 29 min hours and minutes. Among the 100 newborns evaluated, 49% were male and 51% were female. Birth weight average was 3274.9 ± 439.85 g, with 39 ± 1 weeks of gestational age. The mean maternal age was 23 ± 6 years.

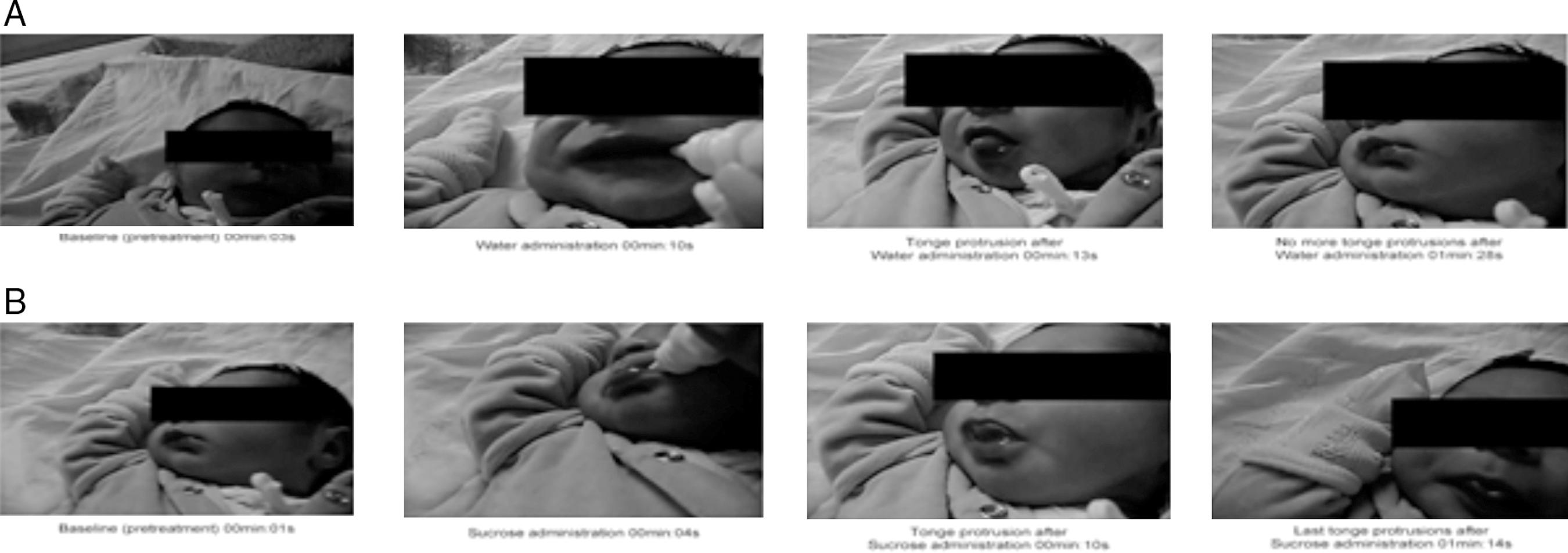

A total of 100 newborns were recorded for neutral (water) and sucrose solution intake, generating 197 videos (n = 3 missing data for the water treatment). Fig. 1 displays four newborns sequences for neutral (Fig. 1A) and sucrose (Fig. 1B) solutions.

Newborn facial expressions to neutral (water, A) and (B) sucrose solutions. (A) Characteristic newborn facial expression to neutral solution (water). (B) Characteristic newborn facial expression to sucrose solution, exhibiting tongue protrusions (designated as hedonic reaction when performed in rhythmic series). Previously to the administration of both solutions (water and sucrose), all newborns showed no spontaneous facial hedonic responses. The intake of both solutions induced hedonic reaction expressions, but the sucrose solution evoked higher frequencies of hedonic reaction expressions in relation to intake of the neutral solution.Photos representing newborn's baseline (pre-treatment), during solution administration, first (if it occurred) and last protrusion after solution administration (in minutes and seconds).

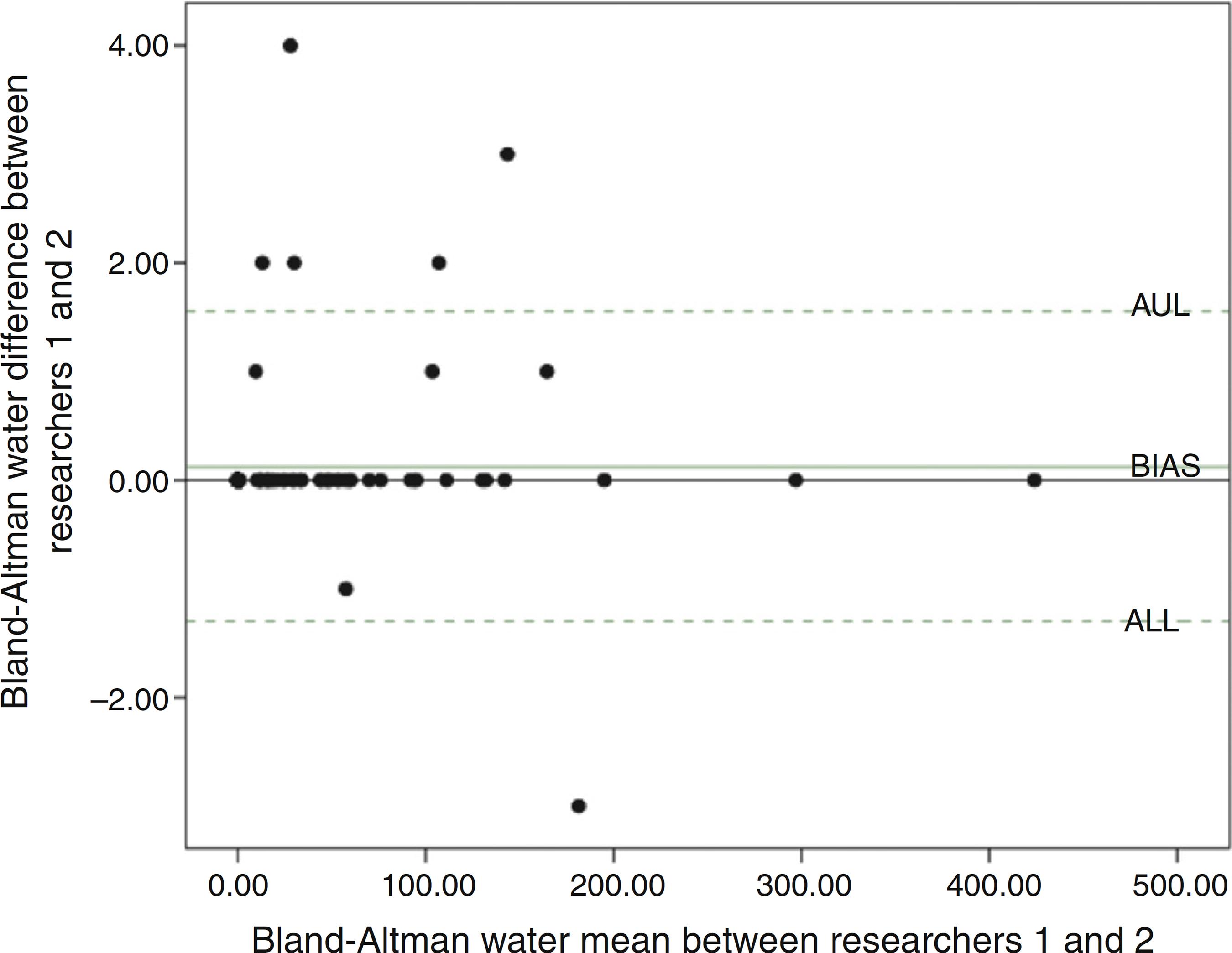

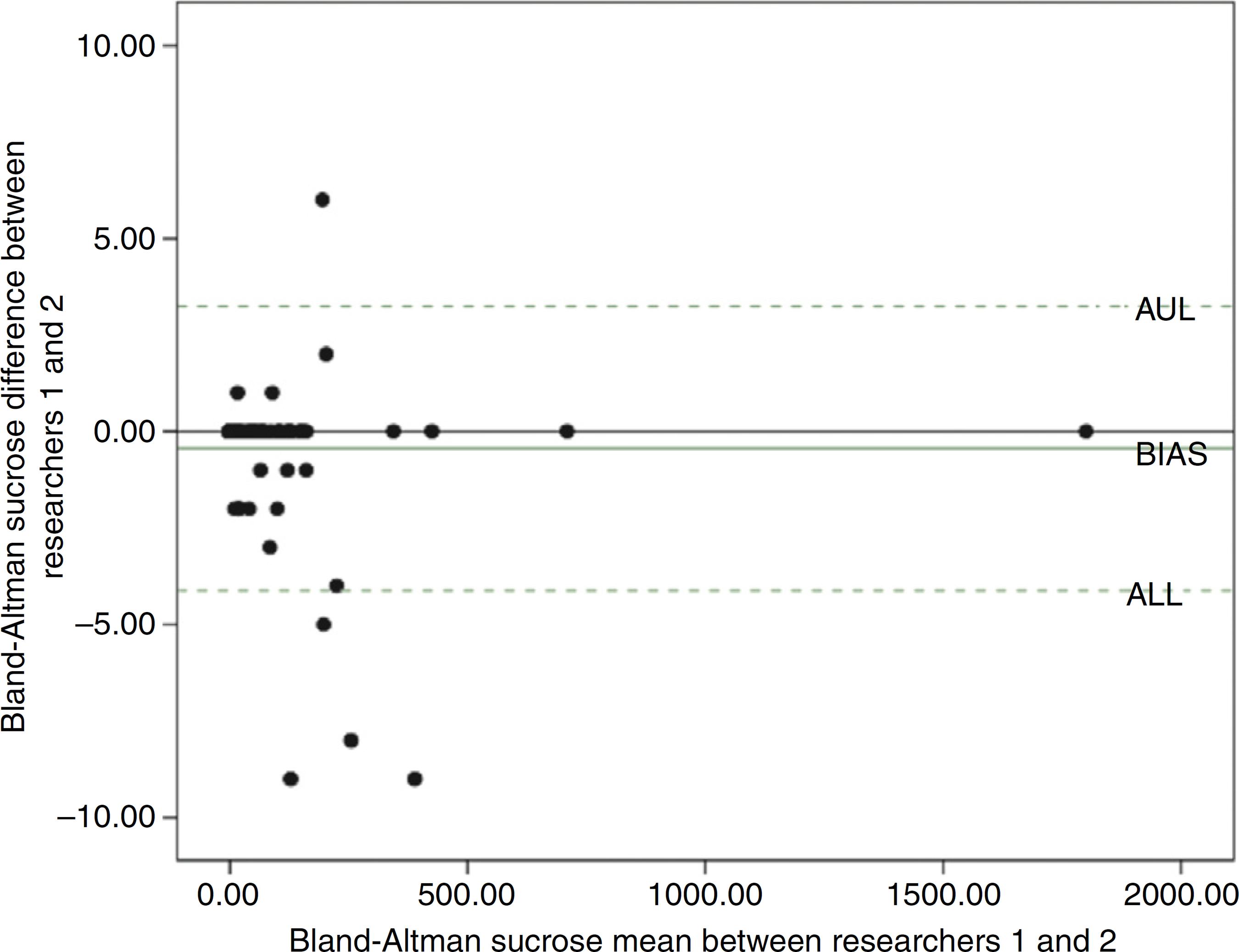

The Bland-Altman test indicated agreement between researchers, both in relation to the water solution (Fig. 2) and the sucrose solution (Fig. 3). Through 95% agreement limits, it was observed that there was an agreement in more than 90% of the data.

Bland-Altman dispersion chart representing inter-rater agreement in relation to neutral solution (water). AUL, agreement upper limit; ALL, agreement lower limit.

Bland-Altman dispersion chart representing inter-rater agreement in relation to sucrose solution. AUL, agreement upper limit; ALL, agreement lower limit.

Previously to the administration of both solutions (water and sucrose), all newborns showed no spontaneous facial hedonic responses. Total hedonic responses evoked by neutral solution (water) was scored 0 for both researchers (researcher 1: median = 0.0, 25th percentile = 0.0, 75th percentile = 48.5; researcher 2: median = 0.0, 25th percentile = 0.0, 75th percentile = 48.5). On the other hand, hedonic responses evoked by sucrose solution were scored 17 and 16.0 for both researchers, respectively (researcher 1: median = 17.0, 25th percentile = 0.0, 75th percentile = 98.0; researcher 2: median = 16.0, 25th percentile = 0.0, 75th percentile = 96.8). The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for all analyses was 0.99 for both (p ≤ 0.001).

Comparing hedonic facial frequency values between neutral and sucrose solutions, an increase in hedonic facial expression evoked by the sucrose solution (p = 0.004) was observed. This result confirms that this methodology displays power to detect differences between sucrose and neutral stimuli (Fig. 4).

Frequencies of hedonic expressions in response to neutral (water) or sucrose solutions. Hedonic facial frequencies were increased in response to sucrose solution, compared to the neutral solution (p = 0.004). The box represents the interquartile (IQ) range. The whiskers are lines that extend from the upper and lower edge of the box. A line across the box indicates the median. Outliers are cases with values between 1.5 and 3 times the IQ range (̊). Extremes are cases with values more than 3 times the IQ range (*).

Discussion

To the best of authors' knowledge, this is the first Brazilian protocol showing an assessment method description for newborns' (up to 24 h of life) affective facial reactions through sweet taste stimulus involving recorded facial expression analysis. This study represents national comparative research (by two researchers blinded to the solutions analyzed - water and sucrose) using a detailed methodology for the qualification of hedonic facial reactions. This study provides a national scientific protocol with reliable reproducibility, considering the degree of statistical agreement between the two researchers, confirmed by the Bland-Altman method. It was observed that the sweet solution evoked hedonic reactions in infants and that facial expression is an important measure to evaluate possible hedonic responses. The statistical inter-rater agreement confirms that this method is an effective protocol for measuring the hedonic impact of sweet taste in newborns.

Some researchers have recorded facial expressions from photographs, thus analyzing affective reactions of infants and animals.88 Steiner JE. The gustofacial response: observation on normal and anencephalic newborn infants. Symp Oral Sens Percept. 1973;:254-78.,1212 Steiner JE. Discussion paper: innate, discriminative human facial expressions to taste and smell stimulation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1974;237:229-33. With available technology, researchers were able to videotape facial expressions through recordings, which allowed an accurate assessment of facial expression variables (e.g., frequency, duration), such as hedonic and aversive reactions. Furthermore, this method allows for reducing the video speed and evaluating parameters frame-by-frame. It is also possible to identify the hedonic responses to taste stimuli in rodents and primates. Additionally, Mennella et al. described that fetuses exhibit hedonic responses through facial expressions for tastes, even before birth.2222 Mennella JA, Johnson A, Beauchamp GK. Garlic ingestion by pregnant women alters the odor of amniotic fluid. Chem Senses. 1995;20:207-9. Some authors have already studied children's response to sucrose stimulus, suggesting that an early experience to sweetened water intake could maintain a preference for sucrose solutions later in life.66 Beauchamp GK, Moran M. Dietary experience and sweet taste preference in human infants. Appetite. 1982;3:139-52. These expressions induced by tastes produce feelings, as this parameter refers only to taste quality, not measuring its intensity. Facial expressions are affective reactions for a specific taste hedonic impact/response, reflecting the pleasure feeling of a particular taste. Additionally, it is not possible to assess the substance offered only by its sensory quality. A salty taste, for example, could extract a positive reaction in the same way that a sweet taste does. On the other hand, a sour, bitter, or very salty taste could extract similar negative reactions. However, a trained researcher could assess whether a child liked a taste based on facial expression, considering this as a positive (hedonic) or a negative (aversive) reaction.1717 Berridge KC. Measuring hedonic impact in animals and infants: microstructure of affective taste reactivity patterns. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:173-98.

In 2009, Schwartz et al. assessed the acceptance of tastes and their developmental changes over the first year, compared to acceptance for all tastes and reactivity to the overall flavor.2323 Schwartz C, Issanchou S, Nicklaus S. Developmental changes in the acceptance of the five basic tastes in the first year of life. Br J Nutr. 2009;102:1375-85. The acceptance of tastes (sweet, salty, bitter, sour, and umami) was evaluated in three groups (45 subjects) with ages of 3, 6, and 12 months. In all ages, the acceptance during the first year and the most preferred taste was confirmed by the sweet and salty taste. Facial reactions to umami were neutral. Sour and bitter tastes were the least accepted. By improving the knowledge of the acceptance of a certain taste, a better understanding of feeding behavior in childhood is provided, which could reflect the eating behavior in adulthood.

Focusing on the study of facial expressions, studies have shown that some taste components induces similar facial reactions among all primates, such as "gapes" for bitter flavors, or serial and rhythmic tongue protrusions for sweets.11 Steiner JE, Glaser D, Hawilo ME, Berridge KC. Comparative expression of hedonic impact: affective reactions to taste by human infants and other primates. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2001;25:53-74.,1717 Berridge KC. Measuring hedonic impact in animals and infants: microstructure of affective taste reactivity patterns. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:173-98.,1818 Smith KS, Berridge KC. Opioid limbic circuit for reward: interaction between hedonic hotspots of nucleus accumbens and ventral pallidum. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1594-605. Another study aimed to compare the facial responses to tastes among newborns of women with and without gestational diabetes mellitus. The tastes were evaluated by glucose, sodium chloride, citric acid, and quinine hydrochloride administrations; 0.2 mL of solution over the dorsal surface of the tongue. In this study, the newborns had their faces and facial responses recorded were coded according to the Baby FACS, in which newborns of mothers with gestational diabetes mellitus seem to prefer the taste of salt.1919 Zacche Sa A, Silva JR, Alves JG. Facial responses to basic tastes in the newborns of women with gestational diabetes mellitus. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:1687-90.

Although the preference for sweet substances exists in newborns, standard experiences with sweet foods and drinks during development could be modulated. Besides, few studies have investigated the direct relationship between eating sweets and their real effect on the appetite for sweet tastes in newborns.44 Mennella JA, Griffin CE, Beauchamp GK. Flavor programming during infancy. Pediatrics. 2004;113:840-5.

5 Mennella JA, Jagnow CP, Beauchamp GK. Prenatal and postnatal flavor learning by human infants. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E88.

6 Beauchamp GK, Moran M. Dietary experience and sweet taste preference in human infants. Appetite. 1982;3:139-52.-77 Beauchamp GK, Mennella JA. Early flavor learning and its impact on later feeding behavior. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:S25-30. Studies that investigated the neural basis for sensory pleasure related to food designated some brain sub-regions as "hedonic hotspots," which are encephalic areas capable of amplifying causally positive affective reactions to sweet tastes in response to certain neurobiological and neurochemical stimuli (e.g., orexin, opioids, palatable foods, and sweet tastes), generating "liking" or "pleasurable" feelings.99 Peciña S, Smith KS, Berridge KC. Hedonic hot spots in the brain. Neuroscientist. 2006;12:500-11.,2424 Castro DC, Berridge KC. Advances in the neurobiological bases for food 'liking' versus 'wanting'. Physiol Behav. 2014;136:22-30.

25 Castro DC, Berridge KC. Opioid hedonic hotspot in nucleus accumbens shell: mu, delta, and kappa maps for enhancement of sweetness "liking" and "wanting". J Neurosci. 2014;34:4239-50.-2626 Ho CY, Berridge KC. An orexin hotspot in ventral pallidum amplifies hedonic 'liking' for sweetness. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:1655-64. These hedonic mechanisms are at least partially distinct from mesocorticolimbic circuitry, a biological pathway that generates motivation for eating and the "wanting" feeling.2424 Castro DC, Berridge KC. Advances in the neurobiological bases for food 'liking' versus 'wanting'. Physiol Behav. 2014;136:22-30.,2525 Castro DC, Berridge KC. Opioid hedonic hotspot in nucleus accumbens shell: mu, delta, and kappa maps for enhancement of sweetness "liking" and "wanting". J Neurosci. 2014;34:4239-50. The current evidence suggests that "hedonic hotspots" exist in limbic brain structures, being capable of increasing the hedonic impact of natural sensory rewards, like palatable and sweet tastes. In this sense, these access points are found in nucleus accumbens (particularly its medial shell area),2424 Castro DC, Berridge KC. Advances in the neurobiological bases for food 'liking' versus 'wanting'. Physiol Behav. 2014;136:22-30.,2525 Castro DC, Berridge KC. Opioid hedonic hotspot in nucleus accumbens shell: mu, delta, and kappa maps for enhancement of sweetness "liking" and "wanting". J Neurosci. 2014;34:4239-50. ventral pallidum,2626 Ho CY, Berridge KC. An orexin hotspot in ventral pallidum amplifies hedonic 'liking' for sweetness. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:1655-64. and parabrachial nucleus.2424 Castro DC, Berridge KC. Advances in the neurobiological bases for food 'liking' versus 'wanting'. Physiol Behav. 2014;136:22-30. Besides, some regions could amplify the sweet hedonic impact, expressing increased "liking/pleasure" reactions for the taste of sucrose.2626 Ho CY, Berridge KC. An orexin hotspot in ventral pallidum amplifies hedonic 'liking' for sweetness. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:1655-64.

As reported by Kringelbach and Berridge, eating behavior is one of the basic life pleasures, which could be modulated by what is eaten or enjoyed in different ways (e.g., liking and disliking).2727 Leonard BE. Pleasures of the Brain Edited by Morten L. Kringelbach, Kent C. Berridge, Oxford University Press, Oxford. pp 343, ISBN: 978-0-533102-8. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 2010;25:429. These personal differences are linked to the individual learning of liking and disliking a specific taste, in addition to an innate preference predisposed to the basic tastes. Some extrinsic, intrinsic, and individual factors may contribute to taste preference, as they are associated to subjective experiences or modulated by hunger/satiety states.2828 Small DM, Zatorre RJ, Dagher A, Evans AC, Jones-Gotman M. Changes in brain activity related to eating chocolate: from pleasure to aversion. Brain. 2001;124:1720-33. This subjective taste perception is produced by different signals to the central nervous system areas.2929 Kringelbach ML. The human orbitofrontal cortex: linking reward to hedonic experience. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:691-702.,3030 Small DM. Flavor is in the brain. Physiol Behav. 2012;107:540-52. Taken together, these data support important information focusing on the representation of taste preference in the central nervous system.

Affective reactivity to taste as a tool for measuring hedonic functions by test could be applied as a useful and objective tool for measurement of liking/pleasure hedonic reactions in response to palatable food, based on the quantification of different taste-induced orofacial affective reactions.11 Steiner JE, Glaser D, Hawilo ME, Berridge KC. Comparative expression of hedonic impact: affective reactions to taste by human infants and other primates. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2001;25:53-74.

This research presents some limitations, such as not having added in the sample newborns who were more than 24 h away from mothers in the hospital rooming. Additionally, another limitation concerns the substances studied. As mentioned before, other substances than sucrose (e.g., salty, sour, or bitter tastes) could be used in this assessment. However, this research's focus was on facial hedonic reactions evoked by sucrose, justifying its specific use. Thus, despite these limitations, the authors can highlight some important features of this research protocol: this study was national comparative research (by two researchers blinded to the substances analyzed-water and sucrose) using a detailed methodology for hedonic facial reaction quantification, using an adequate newborn sample size. Only exclusively breastfed newborns were included in this sample; all newborns were breastfed previously to the treatments. This research provides a national scientific protocol with reliable reproducibility of findings, considering the degree of statistical agreement between the two researchers, confirmed by the Bland-Altman method.

Considering the results, the hedonic facial reactions in newborns reflect the hedonic impact for this specific taste, allowing this methodology to be applied in early life, but in already responsive stages. The authors speculate that hedonic responses through facial expressions are related to the feeling of pleasure due to taste, allowing this direct relation to be interpreted as a greater food consumption of this taste type later in life. More evidence concerning this neural pleasure/reward circuitry relationship is necessary, since it is capable of modifying food intake by "liking/pleasure" responses to foods or tastes, without considering the nutritional balance or nutritional needs. As reward pathways are involved, other pleasurable stimuli may replace the specific consumption of palatable foods that acts through these routes.

-

FundingSupported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Brazil.

-

☆

Please cite this article as: Ayres C, Ferreira CF, Bernardi JR, Marcelino TB, Hirakata VN, Silva CH, et al. A method for the assessment of facial hedonic reactions in newborns. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2017;93:253-9.

References

-

1Steiner JE, Glaser D, Hawilo ME, Berridge KC. Comparative expression of hedonic impact: affective reactions to taste by human infants and other primates. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2001;25:53-74.

-

2Mennella JA. Flavour programming during breast-feeding. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;639:113-20.

-

3Mennella JA, Pepino MY, Reed DR. Genetic and environmental determinants of bitter perception and sweet preferences. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e216-22.

-

4Mennella JA, Griffin CE, Beauchamp GK. Flavor programming during infancy. Pediatrics. 2004;113:840-5.

-

5Mennella JA, Jagnow CP, Beauchamp GK. Prenatal and postnatal flavor learning by human infants. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E88.

-

6Beauchamp GK, Moran M. Dietary experience and sweet taste preference in human infants. Appetite. 1982;3:139-52.

-

7Beauchamp GK, Mennella JA. Early flavor learning and its impact on later feeding behavior. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:S25-30.

-

8Steiner JE. The gustofacial response: observation on normal and anencephalic newborn infants. Symp Oral Sens Percept. 1973;:254-78.

-

9Peciña S, Smith KS, Berridge KC. Hedonic hot spots in the brain. Neuroscientist. 2006;12:500-11.

-

10Volkow ND, Fowler JS. Addiction, a disease of compulsion and drive: involvement of the orbitofrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:318-25.

-

11Stice E, Yokum S, Bohon C, Marti N, Smolen A. Reward circuitry responsivity to food predicts future increases in body mass: moderating effects of DRD2 and DRD4. Neuroimage. 2010;50:1618-25.

-

12Steiner JE. Discussion paper: innate, discriminative human facial expressions to taste and smell stimulation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1974;237:229-33.

-

13Crook CK, Lipsitt LP. Neonatal nutritive sucking: effects of taste stimulation upon sucking rhythm and heart rate. Child Dev. 1976;47:518-22.

-

14Ganchrow JR, Steiner JE, Daher M. Neonatal facial expressions in response to different qualities and intensities of gustatory stimulation in response to different qualities and intensities of gustatory stimuli. Infant Behav Dev. 1983;6:473-84.

-

15Rosenstein D, Oster H. Differential facial responses to four basic tastes in newborns. Child Dev. 1988;59:1555-68.

-

16Porges SW, Lipsitt LP. Neonatal responsivity to gustatory stimulation: the gustatory-vagal hypothesis. Infant Behav Dev. 1993;16:487-94.

-

17Berridge KC. Measuring hedonic impact in animals and infants: microstructure of affective taste reactivity patterns. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:173-98.

-

18Smith KS, Berridge KC. Opioid limbic circuit for reward: interaction between hedonic hotspots of nucleus accumbens and ventral pallidum. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1594-605.

-

19Zacche Sa A, Silva JR, Alves JG. Facial responses to basic tastes in the newborns of women with gestational diabetes mellitus. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:1687-90.

-

20Ayres C, Agranonik M, Portella AK, Filion F, Johnston CC, Silveira PP. Intrauterine growth restriction and the fetal programming of the hedonic response to sweet taste in newborn infants. Int J Pediatr. 2012;2012:6573-9.

-

21Bland JM, Altman DG. Agreed statistics: measurement method comparison. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:182-5.

-

22Mennella JA, Johnson A, Beauchamp GK. Garlic ingestion by pregnant women alters the odor of amniotic fluid. Chem Senses. 1995;20:207-9.

-

23Schwartz C, Issanchou S, Nicklaus S. Developmental changes in the acceptance of the five basic tastes in the first year of life. Br J Nutr. 2009;102:1375-85.

-

24Castro DC, Berridge KC. Advances in the neurobiological bases for food 'liking' versus 'wanting'. Physiol Behav. 2014;136:22-30.

-

25Castro DC, Berridge KC. Opioid hedonic hotspot in nucleus accumbens shell: mu, delta, and kappa maps for enhancement of sweetness "liking" and "wanting". J Neurosci. 2014;34:4239-50.

-

26Ho CY, Berridge KC. An orexin hotspot in ventral pallidum amplifies hedonic 'liking' for sweetness. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:1655-64.

-

27Leonard BE. Pleasures of the Brain Edited by Morten L. Kringelbach, Kent C. Berridge, Oxford University Press, Oxford. pp 343, ISBN: 978-0-533102-8. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 2010;25:429.

-

28Small DM, Zatorre RJ, Dagher A, Evans AC, Jones-Gotman M. Changes in brain activity related to eating chocolate: from pleasure to aversion. Brain. 2001;124:1720-33.

-

29Kringelbach ML. The human orbitofrontal cortex: linking reward to hedonic experience. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:691-702.

-

30Small DM. Flavor is in the brain. Physiol Behav. 2012;107:540-52.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

May-Jun 2017

History

-

Received

25 Nov 2015 -

Accepted

20 June 2016