Abstract

The Xingu River has one of the most diverse fish faunas in the Amazon region. Loricariidae stands out as the most diverse family in the basin, comprising more than 60 species distributed over 26 genera. Species of Loricariidae are some of the most economically valued in the ornamental market worldwide. The loss of fishing environments in Altamira region due to dam impacts is driving a shift of ornamental fishing to areas upstream, among which are included the Xingu River and Iriri River Extractive Reserve Areas. Thus, the objective of this work was to inventory fish species with ornamental potential in these extractive reserves to serve as a baseline to help guide the future management of ornamental fishing in those areas. Thirty-two species of Loricariidae were collected in these reserves through either free diving or diving with compressed air. The composition of species varied according to the sampling method and area. The majority of species found in the reserves are also found in the impacted areas of Belo Monte near Altamira. The study areas showed high diversity of fish species in rapids environments, suggesting that this area could serve as an additional source of income for the residents of these reserves.

Keywords:

Conservation units; Fish diversity; Ornamental fishery; Sustainable management

Resumo

O rio Xingu possui umas das mais diversas ictiofaunas da região Amazônica. Loricariidae destaca-se como a família mais diversa nessa bacia, compreendendo mais de 60 espécies distribuídas em 26 gêneros. As espécies de Loricariidae estão entre as mais valorizadas economicamente no mercado ornamental mundial. A perda de ambientes de pesca na região de Altamira devido aos impactos das barragens está provocando uma mudança da pesca ornamental para áreas a montante, entre as quais estão incluídas as áreas das Reservas Extrativistas do Rio Xingu e do Rio Iriri. Assim, o objetivo deste trabalho foi o de inventariar espécies de peixes com potencial ornamental nestas reservas extrativistas para servir de linha de base para ajudar a orientar o gerenciamento futuro da pesca ornamental nestas áreas. Trinta e duas espécies de Loricariidae foram coletadas nestas reservas através de mergulho livre ou mergulho com ar comprimido. A composição das espécies variou de acordo com o método de amostragem e a área de conservação. A maioria das espécies encontradas nas reservas também são encontradas nas áreas impactadas de Belo Monte, perto de Altamira. As áreas de estudo mostraram grande diversidade de espécies de peixes em ambientes rápidos, sugerindo que esta área poderia servir como uma fonte adicional de renda para os residentes destas reservas.

Palavras-chave:

Diversidade de peixes; Manejo sustentável; Pesca ornamental; Unidades de Conservação

INTRODUCTION

The Xingu River is notable for being the fourth biggest tributary in the Amazon Basin (Goulding et al., 2003Goulding M, Barthem R, Ferreira E. The Xingu and Tapajós rivers: clearwater reflections. In: Goulding M, Barthem R, Ferreira E, editors. The Smithsonian Atlas of the Amazon. Washington and London: Smithsonian Books, 2003. p.135–45. ) and having the most extensive network of rapids in the world (Sawakuchi et al., 2015Sawakuchi AO, Hartmann GA, Sawakuchi HO, Pupim FN, Bertassoli DJ, Parra M et al. The Volta Grande do Xingu: reconstruction of past environments and forecasting of future scenarios of a unique Amazonian fluvial landscape. Sci Dril. 2015; 20:21–32. https://doi.org/10.5194/sd-20-21-2015

https://doi.org/10.5194/sd-20-21-2015...

). The richness of Xingu fishes is among the highest in the Amazon region, comprising approximately 502 species in the entire basin (Dagosta, de Pinna, 2019Dagosta F, de Pinna M. The fishes of the Amazon: distribution and biogeographical patterns, with a comprehensive list of species. B Am Mus Nat Hist. 2019; (431):1–163. https://doi.org/10.1206/0003-0090.431.1.1

https://doi.org/10.1206/0003-0090.431.1....

); 50 of which are endemic to the Xingu (Zuanon, 1999Zuanon JAS. História natural da ictiofauna de corredeiras do Rio Xingu, na região de Altamira, Pará. [PhD Thesis]. São Paulo: Universidade Estadual de Campinas; 1999. Available from: http://bdtd.ibict.br/vufind/Record/CAMP_518e0559dbba98f24df044290e046b26

http://bdtd.ibict.br/vufind/Record/CAMP_...

; Sabaj-Pérez, 2015Sabaj-Pérez MH. Where the Xingu bends and will soon break. Am Sc. 2015; 103(6):395–403. https://doi.org/10.1511/2015.117.395

https://doi.org/10.1511/2015.117.395...

).

Among the Xingu’s fishes, Loricariidae is one of the most diverse families, accounting for 60 species belonging to 26 genera (Camargo et al., 2012Camargo M, Carvalho Jr J, Estupinãn RA. Peixes Comerciais da Ecorregião Aquática Xingu-Tapajós. In: Ecorregiões Aquáticas Xingu-Tapajós. Edition: CETEM/CNPq. 2012. p.175–92. Available from: http://mineralis.cetem.gov.br/bitstream/cetem/816/1/CCL00670012%20%281%29.pdf

http://mineralis.cetem.gov.br/bitstream/...

; Camargo et al., 2013Camargo M, Junior HG, Sousa LM, Rapp Py-Daniel L. Loricariids oh the Middle Rio Xingu. 2º ed., Hanover, Germany: Panta Rhei. 2013. p.211–14.), inhabiting the myriad rocky rapids, channels, islands, and different substrate matrices. Some Loricariidae species in the region are among the most important in the ornamental fish market; according to Araújo, (2016)Araújo JG. Economia e pesca de espécies ornamentais do Rio Xingu, Pará, Brasil. [Master Dissertation]. Belém: Universidade Federal do Pará; 2016. Available from: http://www.ppgeap.propesp.ufpa.br/ARQUIVOS/dissertacoes/2016/PPGEAP_Dissertac%CC%A7a%CC%83o_Janayna%20Galv%C3%A3o%20de%20Ara%C3%BAjo_2016.pdf

http://www.ppgeap.propesp.ufpa.br/ARQUIV...

, it is the group that attracts the most commercial interest in the region, being an important source of income for local fishermen.

Due to combinations of overharvesting for the ornamental fish trade and habitat destruction, some species of Loricariidae have become threatened (Batista et al., 2004Batista VS, Isaac VJ, Viana JP. Exploração e manejo dos recursos pesqueiros da Amazônia. In: Rufino ML, editor. A pesca e os recursos pesqueiros na Amazônia brasileira. Manaus: IBAMA/ProVárzea; 2004. p.63–151. Available from: https://www.pesca.pet/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Ruffino_2004.pdf

https://www.pesca.pet/wp-content/uploads...

; Roman, 2011Roman APO. Biologia reprodutiva e dinâmica populacional de Hypancistrus zebra Isbrücker & Nijssen, 1991 (Siluriformes, Loricariidae), no rio Xingu, Amazônia brasileira. [Master Dissertation]. Belém: Universidade Federal do Pará; 2011. Available from: http://repositorio.ufpa.br/jspui/handle/2011/3499

http://repositorio.ufpa.br/jspui/handle/...

). A complete understanding of the conservation status of many of the discussed species, though, is hindered by the fact that many species and/or phenotypically and genetically distinct populations have still not been described taxonomically and are poorly understood both biologically and ecologically. As a result, it has not been possible to establish guidelines for managing these economic resources (Torres et al., 2008Torres M, Giarrizzo T, Carvalho-Júnior J, Aviz D, Ataíde M, Andrade M. Diagnóstico, tendência, potencial e políticas públicas da estrutura institucional para o desenvolvimento da pesca ornamental. In: Diagnóstico da pesca e da aquicultura do Estado do Pará. Belém: 2008; 5:45–54. Available from: https://elibrary.tips/edoc/nucleo-de-altos-estudos-amazonicos.html

https://elibrary.tips/edoc/nucleo-de-alt...

).

The ornamental fish fishery in the Xingu River basin began in the late 1980s, when unemployed dredge miners started to use their diving equipment to capture fish associated to the bottom (Barthem, 2001Barthem RB. Componente biota aquática. In: Capobianco JPR, Veríssimo A, Moreira A, Sawer D, Ikeda S, Pinto LP, editors. Biodiversidade na Amazônia Brasileira: avaliação e ações prioritárias para a conservação, uso sustentável e repartição de benefícios. São Paulo: Estação Liberdade: Instituto Socioambiental, 2001. p.60–78.). The ornamental fisheries on the Xingu River is focused mainly on Loricariidae, supported by the high species richness of this family on the basin (more than 60 species) and great demand for this family in the international aquarium market (Prang, 2007Prang G. An industry analysis of the freshwater ornamental fishery with particular reference to the supply of Brazilian freshwater ornamentals to the UK market. UAKARI. 2007; 3(1):7–51. ; Ramos et al., 2015Ramos FM, Araújo MLG, Prang G, Fujimoto RY. Ornamental fish of economic and biological importance to the Xingu River. Braz J Biol. 2015; 75(3 suppl 1):95–98. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.02614BM

https://doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.02614B...

; Araújo et al., 2017Araújo JG, Santos MAS, Rebello FK, Isaac VJ. Cadeia comercial de peixes ornamentais do rio Xingu, Pará, Brasil. B Inst Pesca. São Paulo, 2017; 43(2):297–307. https://doi.org/10.20950/1678-2305.2017v43n2p297

https://doi.org/10.20950/1678-2305.2017v...

). Prior to the implementation of the Belo Monte Hydroelectric Power Plant (HPP), the Xingu River Basin ornamental Loricariidae fishery extended from the mouth of Xingu River, at Porto de Moz, upstream to São Félix do Xingu in the middle Xingu River, in addition to the lower stretch of the Iriri River. Historically, the highest concentration of ornamental fishing was in the region of the Volta Grande do Xingu, near the city of Altamira. According to several studies as well as fishermen observations, loricariid diversity in the Xingu region has already been impacted by the completion and operation of the Belo Monte HPP. Many environments, including rapids, deeper channels, and floodplain habitats are being lost, and previously clean substrates required by loricariids are being covered in silt and sediment (Sabaj-Pérez, 2015Sabaj-Pérez MH. Where the Xingu bends and will soon break. Am Sc. 2015; 103(6):395–403. https://doi.org/10.1511/2015.117.395

https://doi.org/10.1511/2015.117.395...

; Sawakuchi et al., 2015Sawakuchi AO, Hartmann GA, Sawakuchi HO, Pupim FN, Bertassoli DJ, Parra M et al. The Volta Grande do Xingu: reconstruction of past environments and forecasting of future scenarios of a unique Amazonian fluvial landscape. Sci Dril. 2015; 20:21–32. https://doi.org/10.5194/sd-20-21-2015

https://doi.org/10.5194/sd-20-21-2015...

; Lees et al., 2016Lees AC, Peres CA, Fearnside PM, Schneider M, Zuanon JAS. Hydropower and the future of Amazonian biodiversity. Biodivers Conserv. 2016; 25:451–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-016-1072-3

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-016-1072-...

).

The especially severe impact of Belo Monte on habitats from which ornamental fishes were collected in the Altamira region is forcing the ornamental fisheries to relocate upstream. According to de Francesco, Carneiro, (2015)de Francesco A, Carneiro C. Atlas dos impactos da UHE Belo Monte sobre a pesca. São Paulo: Instituto Sócio Ambiental; 2015. p.1–54. Available from: https://ox.socioambiental.org/sites/default/files/ficha-tecnica/node/202/edit/2018-06/atlas-pesca-bm.pdf

https://ox.socioambiental.org/sites/defa...

, fisheries areas have already been displaced to further upstream from the main dam, causing territorial conflicts among fishermen. This situation, as well as an increase in local demand, are pushing fishermen into some Sustainable Use Conservation Areas (CA), specifically those upstream of the area affected by Belo Monte. Studies performed in two extractive reserves (RESEX in Portuguese) of the Xingu and Iriri Rivers have reported that residents and officials in these regions are concerned about the increased extractive pressure inside the reserves, specially by non-residents (ICMBio, 2010Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio). Plano de manejo da reserva extrativista do rio Iriri, Altamira – PA [Internet]. 2010. Available from: https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/stories/imgs-unidades-coservacao/PM%20Resex%20do%20Rio%20Iriri%202011.pdf

https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/...

, 2012Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio). Plano de manejo participativo da reserva extrativista rio Xingu, Altamira – PA [Internet]. 2012. Available from: https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/stories/imgs-unidades-coservacao/PM-RESEX-Rio-Xingu-2012.pdf

https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/...

). The collection and commerce of natural goods on Sustainable Use Conservation Areas can be allowed, since management plans have been settled between the residents and the official regulatory agencies (Brasil, 2011Brasil Ministério do Meio Ambiente (MMA). SNUC – Sistema Nacional de Unidades de Conservação da Natureza: Lei nº 9.985, de 18 de julho de 2000; Decreto nº 4.340, de 22 de agosto de 2002; Decreto nº 5.746, de 5 de abril de 2006. Plano Estratégico Nacional de Áreas Protegidas: Decreto nº 5.758, de 13 de abril de 2006. Brasília: MMA; 2011. 76p.). These plans are proven to be a good way to preserve a given area, as the local residents control who can or cannot harvest in the reserve. A mandatory step to begin the management plan discussions is to have a list of the species of the area. As such, the objective of this study was to inventory species of Loricariidae in the Xingu and Iriri River RESEXes. Although not a major study goal, we also explored potential influences of methods of collection and differences among Loricariidae composition on the two protected areas. This study thus establishes a baseline for further studies of the sustainable extraction of ornamental fishes in the in the Xingu and Iriri River RESEXes.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Sampling sites. This research was undertaken in two Sustainable Use Conservation Areas (CA), both located in the Terra do Meio region, an area consisting of various protected areas between the Xingu and Iriri Rivers in the state of Pará, Brazil (Fig. 1). This region exhibits enormous environmental and social diversity and holds significant importance with respect to cultural heritage due to the presence of extractive, river-dependent, and indigenous populations (ICMBio, 2012Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio). Plano de manejo participativo da reserva extrativista rio Xingu, Altamira – PA [Internet]. 2012. Available from: https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/stories/imgs-unidades-coservacao/PM-RESEX-Rio-Xingu-2012.pdf

https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/...

).

Located in Pará, in the north of the Xingu River Basin, the Iriri River RESEX was established by Brazilian Federal Decree on June 5, 2006. It consists of roughly 398,000 hectares and has 285 residents, according to 2009 census (ICMBio, 2010Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio). Plano de manejo da reserva extrativista do rio Iriri, Altamira – PA [Internet]. 2010. Available from: https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/stories/imgs-unidades-coservacao/PM%20Resex%20do%20Rio%20Iriri%202011.pdf

https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/...

).

The Xingu River RESEX is also located in Pará and was created by Brazilian Federal Decree on June 5, 2008. It has an area of approximately 303,841 hectares and 298 residents as of August 2011 (ICMBio, 2012Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio). Plano de manejo participativo da reserva extrativista rio Xingu, Altamira – PA [Internet]. 2012. Available from: https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/stories/imgs-unidades-coservacao/PM-RESEX-Rio-Xingu-2012.pdf

https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/...

).

The Iriri and the Xingu rivers drain the Brazilian Shield and are considered clear water rivers with rocky bottom and similar water parameters: pH 6.5-7.2, conductivity 20 µS, visibility varying from 0 (rainy season) to 3 m (dry season). The Iriri River at most parts is shallower than the Xingu River, leading to warmer temperatures (up to average 34°C compared to 32°C of Xingu in dry season).

Data collection and analysis. The collection and use of animals complied with Brazilian animal welfare laws, guidelines and policies as approved by SISBIO License #52313-1. Fishes were collected in 2016 over two different periods: the rainy season (January and February), and the dry season (August and September). The collections alternated between the reserves and lasted 17 days each; as such, there were two expeditions to each RESEX. Field collections were focused on the family Loricariidae, given its relevance to the fishermen of this region due to the high prices of these fishes on the ornamental market.

The first collections took place in the rainy season. In every locality, two local fishermen collected ornamental fishes, using cast nets and compressed-air diving equipment. A total of 39 points were sampled in the Iriri RESEX and 40 in the Xingu RESEX in the rainy season. In the dry season, fishes were collected by free diving, with only cast nets and “vaquetas” (a wooden stick instrument, produced by the fishermen). Collections were performed by local fishermen who were at liberty to choose their collection points, thereby prioritizing local ecological knowledge. In the dry season, 14 and 23 points were sampled in the Iriri and Xingu River RESEXes, respectively.

Although collection methods differed between seasons, all dives were conducted in environments with rocky substrates and were standardized by time. Most dives lasted about one hour.

In the rainy season, collected fishes were packed in plastic bags, separated by sample, tagged, and afterward euthanised with clove oil and fixed in a 10% formaldehyde solution. In the dry season, most fishes were sorted and identified while still in the field, then released afterward. Some specimens were sacrificed and processed as in the rainy season. All voucher specimens are deposited at Laboratório de Ictiologia de Altamira (LIA) fish collection of the Federal University of Pará, Altamira Campus.

In the laboratory, fishes were identified to the lowest taxonomic level possible. Identifications were based on specific literature sources; whenever necessary, specialists for each group were consulted. The L-number code (a parataxonomical system coined by German magazine Deutsche Aquarien- und Terrarien-Zeitschrift - DATZ) was utilized to refer to undescribed morphospecies in some cases. Afterward, samples were separated into groups (for species and sample point), transferred to 70% alcohol, and catalogued.

In order to evaluate the specificity and fidelity of each species for each RESEX, an indicator value (IndVal) was calculated (Dufrêne, Legendre, 1997Dufrêne M, Legendre P. Species assemblages and indicator species: the need for a flexible asymmetrical approach. Ecol Monogr. 1997; 67(3):345–66. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9615(1997)067[0345:SAAIST]2.0.CO;2

https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9615(1997)0...

), with values varying from 0 to 100, where numbers closest to 100 meaning more specificity and fidelity to each variable.

After evaluating whether the composition of the species varied based on the collection method, a Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA) was performed (Anderson, 2001Anderson MJ. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001; 26(1):32–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9993.2001.01070.pp.x

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9993.2001...

), using a significance threshold of p = 0.05. An independent sample t-test was used to test for differences in the richness of the collected species by location and different collection methods utilized. To test for differences in species composition on the two reserves, a permutational multivariate dispersion test (PERMDISP) and a PERMANOVA were performed (Anderson, 2001Anderson MJ. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001; 26(1):32–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9993.2001.01070.pp.x

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9993.2001...

), using a significance threshold of p = 0.05. In order to graphically visualize the differences in species composition, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was employed (Legendre, Legendre, 2012Legendre P, Legendre L. Numerical Ecology. Developments in Environmental Modelling. Vol. 24: Elsevier; 2012.); a Hellinger transformation was overlaid using a Decostand function, in order to remove the arch effect in biotic communities (Legendre, Gallagher, 2001Legendre P, Gallagher ED. Ecologically meaningful transformations for ordination of species data. Oecologia. 2001; 129(2):271–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420100716

https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420100716...

). All analyses were performed in the program R, using the packages Indcspecies (IndVal), Vegan with Adonis and Bray Curtis method (PERMANOVA), Betadisper (PERMDISP), and RDA (composition PCA) functions (R Core Team, 2016R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing, Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2016. Available from: https://www.r-project.org/

https://www.r-project.org/...

).

RESULTS

In total, 6,059 individual fishes were collected, of which 3,232 were preserved and deposited in the LIA fish collection. The remaining fishes were returned alive to where they were collected as described above. The collected samples were assigned to 32 species or morphotypes of Loricariidae (Tab. 1).

List of registered species and number of collected specimens in the Xingu and Iriri River RESEXes.

Out of the total, 24 species were found in both RESEXes, whereas only 3 and 5 were exclusive to the Iriri and Xingu River RESEXes, respectively (Fig. 2).

Venn diagram showing the compositions of the Loricariidae species found in both extractive reserves.

When comparing the two sampling methods, eleven species presented significant IndVal values for free diving (by apnea) while two species for air compressed diving (Tab. 2).

When taking into account drainage in the RESEXes, A. feldbergae, P. pirarara, A. ranunculus, and Ancistrus sp.4 were more representative of the Iriri River RESEX, reaching IndVal values of 85.3, 48.2, 30.7 and 30.7, respectively. On the other hand, the species that best represented the Xingu River RESEX were Ancistrus cf. ranunculus L255, P. sabaji, and B. chrysolomus, with values of up to 64.8, 40.9, and 33.1, respectively (Tab. 3).

Indicator values (IndVal) of the species, taking into account drainage in the Xingu and Iriri River RESEXes.

In relation to the richness of the species, there were significant differences between the samples, both based on free diving (x = 8.48) and diving with compressed air (x = 5.71). On average, there was more variation when comparing the richness of three species using the free diving method (t = 5.88, df = 113, p < 0.01). However, species richness didn’t vary significantly between the reserves (t = 1.311, df = 113, p = 0.09).

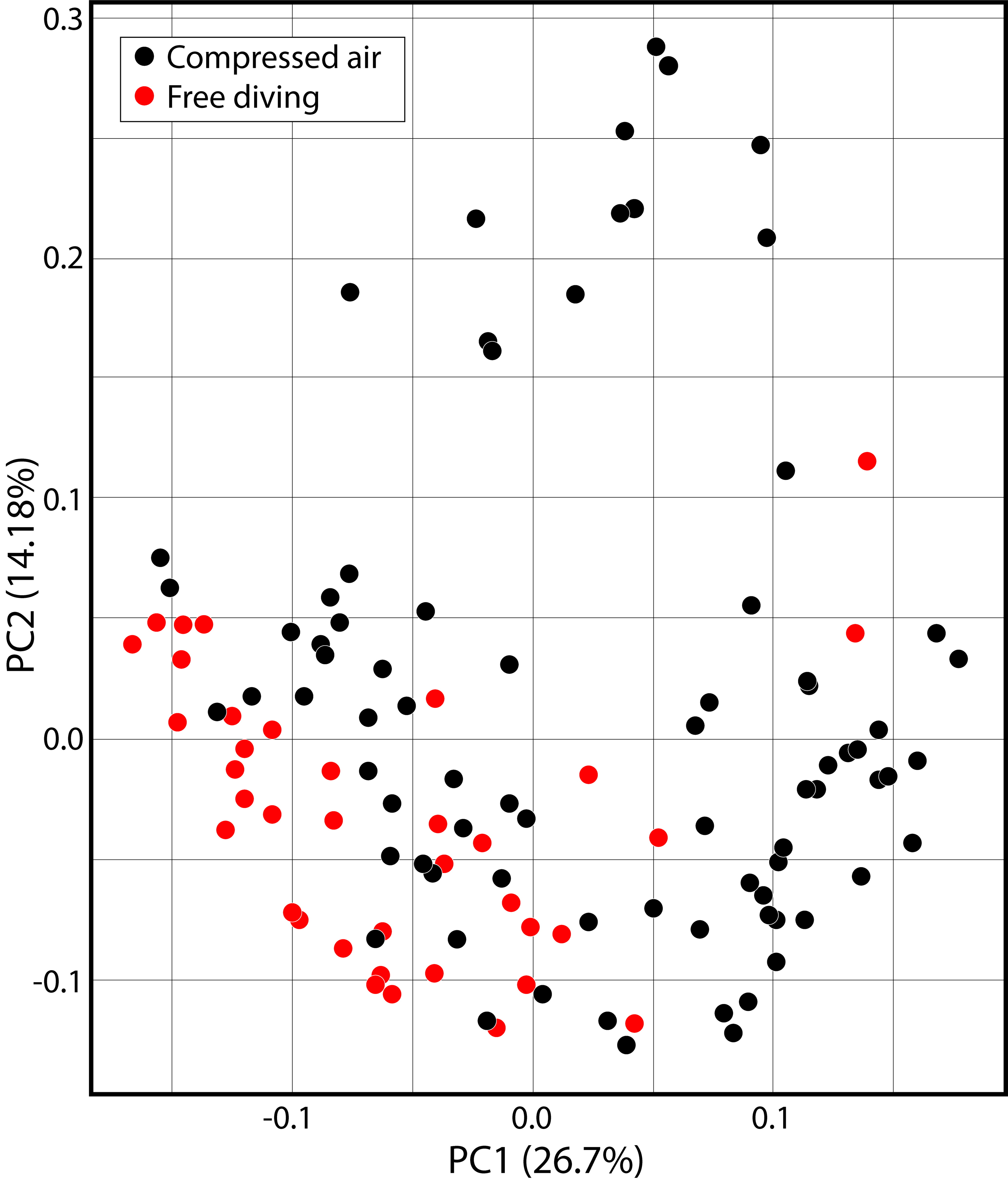

The composition of species changed depending on the method of capture (R² = 0.09; p < 0.01) (Fig. 3). Ancistrus sp.5, Hypostomus gr. cochliodon, Rineloricaria sp. were only collected by free diving, whereas the Ancistrus sp.1, Ancistrus sp.4, Ancistrus sp.6, and Hopliancistrus xikrin were only collected using compressed-air diving equipment.

Principal component analysis (PCA) for composition of ornamental fish species based on the method of capture (Hellinger transformation), considering the two extractive reserves.

The PERMDISP showed that the variation in composition within the reserves does not differ (F = 0.002; p = 0.974). However, the PERMANOVA analysis showed that the species composition was significantly different between the reserves (F = 10.381; p < 0.001). Spectracanthicus punctatissimus, B. xanthellus, and A. feldbergae from the Iriri River RESEX and Parancistrus aurantiacus, Ancistrus. cf. ranunculus L255 and S. zuanoni from the Xingu River RESEX made the greatest contributions to compositional differences found between the two reserves (Fig. 4).

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of fish composition in the drainages of both the Xingu and Iriri River RESEXes (Hellinger transformation). Only species names that made greatest contributions to compositional differences are shown.

DISCUSSION

According to Herbert et al., (2010)Herbert ME, McIntyre PB, Doran PJ, Allan JD, Abell R. Terrestrial reserve networks do not adequately represent aquatic ecosystems. Conserv Biol. 2010; 24(4):1002–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01460.x

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010...

, freshwater biodiversity in protected areas in Brazil is still poorly understood, with very few studies addressing these areas. Until now, no research had been completed on the ichthyofauna of the Conservation Areas of Middle Xingu. Management plans for these CAs currently lack data on the diversity and richness of the ichthyofauna in rapids environments. However, they do contain statements from fishermen that ornamental fish species richness is high in the area, and that these species were regularly captured in these areas before the reserves were created (ICMBio, 2010Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio). Plano de manejo da reserva extrativista do rio Iriri, Altamira – PA [Internet]. 2010. Available from: https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/stories/imgs-unidades-coservacao/PM%20Resex%20do%20Rio%20Iriri%202011.pdf

https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/...

, 2012Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio). Plano de manejo participativo da reserva extrativista rio Xingu, Altamira – PA [Internet]. 2012. Available from: https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/stories/imgs-unidades-coservacao/PM-RESEX-Rio-Xingu-2012.pdf

https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/...

).

In this study, 32 Loricariidae species were captured across the two reserves. This value represents approximately 60% of the total Loricariidae species already registered in the Xingu River Basin (Sabaj-Pérez, 2015Sabaj-Pérez MH. Where the Xingu bends and will soon break. Am Sc. 2015; 103(6):395–403. https://doi.org/10.1511/2015.117.395

https://doi.org/10.1511/2015.117.395...

). The majority of species found in both CAs are also found downstream in the Volta Grande area, which nowadays are experiencing severe alterations from the Belo Monte hydroelectric complex. Some species, however, are unique to the reserves, like Ancistrus cf. ranunculus L255, Ancistrus sp.2, Ancistrus sp.5, and Ancistrus sp.6. A study performed in the Madeira River indicated a diverse environment of 71 Loricariidae species (Torrente-Vilara et al., 2013Torrente-Vilara G, Queiroz LJ, Ohara WM. Um breve histórico sobre o conhecimento da fauna de peixes do Rio Madeira. In: Queiroz LJ, Torrente-Vilara G, Ohara WM, Pires THS, Zuanon J, Doria CRC, organizers. Peixes do Rio Madeira - Vol. I. São Paulo: Dialeto Latin American Documentary; 2013. p.19–25.). Meanwhile, Anjos et al., (2008)Anjos HDB, Zuanon J, Braga TMP, Sousa KNS. Fish, upper Purus River, state of Acre, Brazil. Check List. 2008; 4(2):198–213.https://doi.org/10.15560/4.2.198

https://doi.org/10.15560/4.2.198...

, identified Loricariidae as the second richest family, at 11 total species, in a compositional study of fishes in the upper Purus River, specifically in two tributaries, the Caeté and Macapá rivers, in the state of Acre, Brazil. Ferreira et al., (2011)Ferreira E, Zuanon J, Santos G, Amadio S. A ictiofauna do Parque Estadual do Cantão, Estado do Tocantins, Brasil. Biota Neotrop. 2011; 11(2):277–84. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1676-06032011000200028

https://doi.org/10.1590/S1676-0603201100...

came to the same conclusion after recording 23 species in a survey of the Araguaia River, in Cantão State Park in Tocantins, near the border with Pará.

Of all the species in this study, 8 were registered for only one reserve or the other, with 3 for the Iriri River RESEX and 5 for the Xingu River RESEX. This fact highlights the importance of creating multiple conservation areas in sub-basins that are near each other, as not all species of a given region can be found in just one CA.

Few of the exclusive species have been taxonomically named yet, the majority of which might be new species without any scientific record. This precludes inferences on endemicity of these species to this region, but it does indicate the need to continue studying the area. However, given that the CAs are in different sub-basins, some of the species could, in fact, be exclusive to one reserve or the other. The Xingu River is known for its high rates of endemism (Sabaj-Pérez, 2015Sabaj-Pérez MH. Where the Xingu bends and will soon break. Am Sc. 2015; 103(6):395–403. https://doi.org/10.1511/2015.117.395

https://doi.org/10.1511/2015.117.395...

; Sawakuchi et al., 2015Sawakuchi AO, Hartmann GA, Sawakuchi HO, Pupim FN, Bertassoli DJ, Parra M et al. The Volta Grande do Xingu: reconstruction of past environments and forecasting of future scenarios of a unique Amazonian fluvial landscape. Sci Dril. 2015; 20:21–32. https://doi.org/10.5194/sd-20-21-2015

https://doi.org/10.5194/sd-20-21-2015...

; Winemiller et al., 2016Winemiller KO, McIntyre PB, Castello L, Fluet-Chouinard E, Giarrizzo T, Nam S et al. Balancing hydropower and biodiversity in the Amazon, Congo, and Mekong. Science. 2016; 351(6269):128–29. Available from https://science.sciencemag.org/content/351/6269/128/tab-pdf

https://science.sciencemag.org/content/3...

; Dagosta, de Pinna, 2019Dagosta F, de Pinna M. The fishes of the Amazon: distribution and biogeographical patterns, with a comprehensive list of species. B Am Mus Nat Hist. 2019; (431):1–163. https://doi.org/10.1206/0003-0090.431.1.1

https://doi.org/10.1206/0003-0090.431.1....

; Jézéquel et al., 2020Jézéquel C, Tedesco PA, Bigorne R, Maldonado-Ocampo JA, Ortega H, Hidalgo M et al. A database of freshwater fish species of the Amazon Basin. Sci Data. 2020; 7(96):1–09. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-0436-4

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-0436-...

). For example, Ancistrus cf. ranunculus L255 was collected only in the Xingu River RESEX, thereby reinforcing the results from previous, unpublished research that showed that this species has a limited distribution in the Xingu River upstream from its confluence with the Iriri River.

Despite of the strong selectivity towards Loricariidae during all sampling sessions, the composition of the captured species varies depending on the method used. According to Carvalho Júnior et al., (2009)Carvalho-Júnior JR, Carvalho NASS, Nunes JLG, Camões A, Bezerra MFC, Santana AR et al. Sobre a pesca de peixes ornamentais por comunidades do rio Xingu, Pará-Brasil: relato de caso. Bol Inst Pesca. 2009; 35(3):521–30. Available from: https://www.pesca.sp.gov.br/35_3_521-530.pdf

https://www.pesca.sp.gov.br/35_3_521-530...

, diving with an air compressor allows for the capture of species that live at greater depths, regardless of the time of year. In addition, this method provides more diving time, which could lead to a greater number of collected species. Meanwhile, free diving allows for capturing species in shallower environments; these are performed preferentially in dry periods (Mesquita, Isaac-Nahum, 2015Mesquita EMC, Isaac-Nahum VJ. Traditional knowledge and artisanal fishing technology on the Xingu River in Pará, Brazil. Braz J Biol. 2015; 75(3 suppl 1):138–57. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.01314BM

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.0131...

).

Contrary to what fishermen commonly argue, our study found a greater richness of species captured through free diving compared to compressed air dives. In this case, other factors might have impacted our results. For example, the free divers were residents of the area, meaning that they knew the region, whereas those who dived using compressed air were not from the reserves, but were knowledgeable, experienced fishermen who were selected due to their skills in diving with a compressor in another areas. In addition, the seasonal bias needs also to be accounted. Free diving was conducted mainly in the dry season and compressed air diving in the rainy season. Espírito-Santo et al., (2009)Espírito-Santo HMV, Magnusson WE, Zuanon J, Mendonça FP, Landeiro VL. Seasonal variation in the composition of fish assemblages in small Amazonian forest streams: evidence for predictable changes. Freshwater Biol. 2009; 54(3):536–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.2008.02129.x

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.2008...

studied the Ducke Reserve, near the city of Manaus, Amazonas, and found that fish species richness and numbers of individuals captured were greater in the dry season, with a different composition and abundance observed depending on the season. Such results can also be found when considering river seasonality (Copatti et al., 2009Copatti CE, Zanini LG, Valente A. Ictiofauna da microbacia do rio Jaguari, Jaguari/RS, Brasil. Biota Neotrop. 2009; 9(2):179–86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1676-06032009000200017

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1676-06032009...

). The rapids portions of the Xingu River diminish during dry periods, thereby comparably affecting the habitats of the studied species. This might lead to a greater abundance and richness of species concentrated in a smaller area. That being said, Loricariidae species are dependent on the substrate, given that all their food sources are from the flora and fauna found in this habitat (Reis et al., 2003Reis RE, Kullander SO, Ferraris CJ Jr, editors. Check list of the freshwater fishes of South and Central America. Porto Alegre: Edipucrs; 2003.; Lujan et al., 2012Lujan NK, Winemiller KO, Armbruster JW. Trophic diversity in the evolution and community assembly of loricariid catfishes. BMC Evol Biol. 2012; 12(124):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-12-124

https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-12-124...

). Collection conditions in the rainy season are worse: the transparency of the water is severally reduced and because the capture of loricariids while diving is mostly visual, collections are negatively affected during this period. However, the comparison of efficiency of each sampling method was not a major goal of this study design and we suggest that a proper comparison (with delimited number of sampling and replicates by each method) should be the goal of a future study.

The reserves are located on different rivers, each one having a myriad of rapids and backwaters of their own, serving as geographical barriers that might limit migration and promote speciation. These geographical barriers, according to Silva et al., (2016)Silva JC, Gubiani ÉA, Piana PA, Delariva RL. Effects of a small natural barrier on the spatial distribution of the fish assemblage in the Verde River, Upper Paraná River basin, Brazil. Braz J Biol. 2016; 76(4):851–63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.01215

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.0121...

, could be an important factor in determining the composition of the ichthyofauna. The Iriri River has a complex regional slope, in addition to the significant variations in water level across seasons (ICMBio, 2010Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio). Plano de manejo da reserva extrativista do rio Iriri, Altamira – PA [Internet]. 2010. Available from: https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/stories/imgs-unidades-coservacao/PM%20Resex%20do%20Rio%20Iriri%202011.pdf

https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/...

). Furthermore, the Xingu River has morphological characteristics and a substrate composition that fundamentally affects its aquatic ecology and biodiversity (Sawakuchi et al., 2015Sawakuchi AO, Hartmann GA, Sawakuchi HO, Pupim FN, Bertassoli DJ, Parra M et al. The Volta Grande do Xingu: reconstruction of past environments and forecasting of future scenarios of a unique Amazonian fluvial landscape. Sci Dril. 2015; 20:21–32. https://doi.org/10.5194/sd-20-21-2015

https://doi.org/10.5194/sd-20-21-2015...

). These local structural characteristics work together with regional and historical factors in determining how fish species congregate, meaning that different habitats can lead to different combinations (Súarez, 2008Súarez YR. Variação espacial e temporal na diversidade e composição de espécies de peixes em riachos da bacia do rio Ivinhema, alto rio Paraná. Biota Neotrop. 2008; 8(3):197–204. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-40142010000100015

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-4014201000...

).

Furthermore, this study identified several species that are classified as vulnerable by the Brazil Red Book of Threatened Species of Fauna, such as S. aureatus and S. pariolispos (ICMBio, 2018Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio). Livro Vermelho da Fauna Brasileira Ameaçada de Extinção. Vol. I, 1th ed., Brasília: ICMBio/MMA; 2018. Available from: https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/stories/comunicacao/publicacoes/publicacoes-diversas/livro_vermelho_2018_vol1.pdf

https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/...

). The presence of these species in protected areas demonstrates the importance of conducting an inventory of ichthyofauna such as the one we conducted here. Information about diversity of an area is required to make qualified decisions about the management of natural areas (Silveira et al., 2010Silveira LF, Beisiegel BM, Curcio FF, Valdujo PH, Dixo M, Verdade VK et al. What use do Fauna Inventorie serve? Estud Av. 2010; 24(68):173–207. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-40142010000100015

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-40142010...

). The detection of Scobinancistrus aureatus in the Iriri River RESEX is very interesting, as previous research had restricted its distribution to the middle and lower portions of the Xingu River (Camargo et al., 2004Camargo M, Giarrizzo T, Isaac V. Review of the geographic distribution of fish fauna of the Xingu River basin, Brazil. Ecotropica. 2004; 10:123–47. Available from: https://mamiraua.org.br/entos/682b5dbf3fd22e70ea0f8b16083a0bff.pdf

https://mamiraua.org.br/entos/682b5dbf3f...

), and the species had only been found between Cachoeira do Espelho and the rapids of Belo Monte (Camargo et al., 2013Camargo M, Junior HG, Sousa LM, Rapp Py-Daniel L. Loricariids oh the Middle Rio Xingu. 2º ed., Hanover, Germany: Panta Rhei. 2013. p.211–14.). As such, this observation considerably increases the known distribution of this species and can contribute to new discussions about its conservation status.

Of the 32 Loricariidae species that were inventoried, 16 are already being sold in the ornamental market, with local market prices ranging from 0.20 to 100.00 Brazilian Reais per animal (Araújo, 2016Araújo JG. Economia e pesca de espécies ornamentais do Rio Xingu, Pará, Brasil. [Master Dissertation]. Belém: Universidade Federal do Pará; 2016. Available from: http://www.ppgeap.propesp.ufpa.br/ARQUIVOS/dissertacoes/2016/PPGEAP_Dissertac%CC%A7a%CC%83o_Janayna%20Galv%C3%A3o%20de%20Ara%C3%BAjo_2016.pdf

http://www.ppgeap.propesp.ufpa.br/ARQUIV...

), or 0.08 to 40.00 USD on 2015 currency. Nevertheless, few species fall in the higher part of this range (Gonçalves et al., 2009Gonçalves AP, Camargo M, Carneiro CC, Camargo ATP, Paula GJX, Giarrizzo T. A pesca de peixes ornamentais. In: Camargo M, Ghilardi R, editors. Entre a terra, as águas e os pescadores do médio rio Xingu: uma abordagem ecológica. Belém, Pará: 2009. p.235–64.; Camargo et al., 2012Camargo M, Carvalho Jr J, Estupinãn RA. Peixes Comerciais da Ecorregião Aquática Xingu-Tapajós. In: Ecorregiões Aquáticas Xingu-Tapajós. Edition: CETEM/CNPq. 2012. p.175–92. Available from: http://mineralis.cetem.gov.br/bitstream/cetem/816/1/CCL00670012%20%281%29.pdf

http://mineralis.cetem.gov.br/bitstream/...

). The environmental changes resulting from the Belo Monte Hydroelectric Plant have negatively affected many fishing areas that are important in the Volta Grande region and that sustained the ornamental fish market in Altamira and the region for decades. This loss of fishing areas near Altamira city is increasing the fishing pressures in protected areas upstream, with the RESEX regions being a new alternative for ornamental fisheries. However, these actions need to be closely monitored and a Management Plan must be created to regulate the use of the natural resources inside the reserves. The use of protected areas by non-resident fishermen can generate escalating conflicts and the reserve’s residents are seeking regulations that protect their rights to the use of this resource. We recommend that fishing areas should be delimited with participation of local villagers and be rotated to avoid overfishing inside the reserves. Exploitation of fisheries resources in the reserve areas should be for the residents only.

The income of the residents of these reserves is based on forest products, like Brazil nuts, latex, and fish for human consumption, among other goods. These products have a strong seasonal availability. Brazil nut, for example, are harvested during the rainy season, whereas fishing for food is more common in the dry season. Ornamental fishing could be another option to complement the incomes of the families who live in the reserves. Nonetheless, additional biological and ecological research is necessary, so that the life history and population dynamics of species within these CAs can be understood. This would allow these species to be managed sustainably, with as little an impact as possible on the fish population of the rapids of the region.

Protected areas have been a pillar of conservation throughout the world. However, their effectiveness and importance have not been adequately evaluated (Gaston et al., 2008Gaston KJ, Sarah FJ, Cantú-Salazar L, Cruz-Piñón G. The ecological performance of protected areas. Annu Rev Ecol Evol S. 2008; 39:93–113. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.39.110707.173529

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys....

). Our results contribute to the understanding of the extent to which protected areas could be essential to maintaining the ichthyofauna of the Xingu region, thereby, reinforcing the importance of creating different protected areas throughout the basin. Such reserves could help preserve the regions distinctive ichthyofauna by maintaining the species in these environments. Inventories such as conducted by this study are needed to provide a baseline understanding of diverse natural resources and help guide the development, delimitation, and management of Conservation Areas to protect those resources.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio) for their logistical and financial support during the sample collection process the Fundação Amazônia de Amparo a Estudos e Pesquisas (FAPESPA) for the master’s scholarship funding. In addition, we ackonwledge Paulo Trindade (UFPA, Belém), Nayana Marques (INPA), Madoka Ito (INPA), and Douglas Bastos (INPA) for their contributions to the collection process. The expeditions were partially financed by Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq 486376/2013-3). Finally, many thanks to the fishermen for their willingness to help collect the specimens and, finally, to the residents of the extractive reserves for welcoming us into their homes.

REFERENCES

- Anderson MJ. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001; 26(1):32–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9993.2001.01070.pp.x

» https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9993.2001.01070.pp.x - Anjos HDB, Zuanon J, Braga TMP, Sousa KNS. Fish, upper Purus River, state of Acre, Brazil. Check List. 2008; 4(2):198–213.https://doi.org/10.15560/4.2.198

» https://doi.org/10.15560/4.2.198 - Araújo JG. Economia e pesca de espécies ornamentais do Rio Xingu, Pará, Brasil. [Master Dissertation]. Belém: Universidade Federal do Pará; 2016. Available from: http://www.ppgeap.propesp.ufpa.br/ARQUIVOS/dissertacoes/2016/PPGEAP_Dissertac%CC%A7a%CC%83o_Janayna%20Galv%C3%A3o%20de%20Ara%C3%BAjo_2016.pdf

» http://www.ppgeap.propesp.ufpa.br/ARQUIVOS/dissertacoes/2016/PPGEAP_Dissertac%CC%A7a%CC%83o_Janayna%20Galv%C3%A3o%20de%20Ara%C3%BAjo_2016.pdf - Araújo JG, Santos MAS, Rebello FK, Isaac VJ Cadeia comercial de peixes ornamentais do rio Xingu, Pará, Brasil. B Inst Pesca. São Paulo, 2017; 43(2):297–307. https://doi.org/10.20950/1678-2305.2017v43n2p297

» https://doi.org/10.20950/1678-2305.2017v43n2p297 - Barthem RB Componente biota aquática. In: Capobianco JPR, Veríssimo A, Moreira A, Sawer D, Ikeda S, Pinto LP, editors. Biodiversidade na Amazônia Brasileira: avaliação e ações prioritárias para a conservação, uso sustentável e repartição de benefícios. São Paulo: Estação Liberdade: Instituto Socioambiental, 2001. p.60–78.

- Batista VS, Isaac VJ, Viana JP Exploração e manejo dos recursos pesqueiros da Amazônia. In: Rufino ML, editor. A pesca e os recursos pesqueiros na Amazônia brasileira. Manaus: IBAMA/ProVárzea; 2004. p.63–151. Available from: https://www.pesca.pet/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Ruffino_2004.pdf

» https://www.pesca.pet/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Ruffino_2004.pdf - Brasil Ministério do Meio Ambiente (MMA). SNUC – Sistema Nacional de Unidades de Conservação da Natureza: Lei nº 9.985, de 18 de julho de 2000; Decreto nº 4.340, de 22 de agosto de 2002; Decreto nº 5.746, de 5 de abril de 2006. Plano Estratégico Nacional de Áreas Protegidas: Decreto nº 5.758, de 13 de abril de 2006. Brasília: MMA; 2011. 76p.

- Camargo M, Giarrizzo T, Isaac V. Review of the geographic distribution of fish fauna of the Xingu River basin, Brazil. Ecotropica. 2004; 10:123–47. Available from: https://mamiraua.org.br/entos/682b5dbf3fd22e70ea0f8b16083a0bff.pdf

» https://mamiraua.org.br/entos/682b5dbf3fd22e70ea0f8b16083a0bff.pdf - Camargo M, Carvalho Jr J, Estupinãn RA. Peixes Comerciais da Ecorregião Aquática Xingu-Tapajós. In: Ecorregiões Aquáticas Xingu-Tapajós. Edition: CETEM/CNPq. 2012. p.175–92. Available from: http://mineralis.cetem.gov.br/bitstream/cetem/816/1/CCL00670012%20%281%29.pdf

» http://mineralis.cetem.gov.br/bitstream/cetem/816/1/CCL00670012%20%281%29.pdf - Camargo M, Junior HG, Sousa LM, Rapp Py-Daniel L Loricariids oh the Middle Rio Xingu. 2º ed., Hanover, Germany: Panta Rhei. 2013. p.211–14.

- Carvalho-Júnior JR, Carvalho NASS, Nunes JLG, Camões A, Bezerra MFC, Santana AR et al Sobre a pesca de peixes ornamentais por comunidades do rio Xingu, Pará-Brasil: relato de caso. Bol Inst Pesca. 2009; 35(3):521–30. Available from: https://www.pesca.sp.gov.br/35_3_521-530.pdf

» https://www.pesca.sp.gov.br/35_3_521-530.pdf - Copatti CE, Zanini LG, Valente A. Ictiofauna da microbacia do rio Jaguari, Jaguari/RS, Brasil. Biota Neotrop. 2009; 9(2):179–86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1676-06032009000200017

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1676-06032009000200017 - Dagosta F, de Pinna M. The fishes of the Amazon: distribution and biogeographical patterns, with a comprehensive list of species. B Am Mus Nat Hist. 2019; (431):1–163. https://doi.org/10.1206/0003-0090.431.1.1

» https://doi.org/10.1206/0003-0090.431.1.1 - Dufrêne M, Legendre P. Species assemblages and indicator species: the need for a flexible asymmetrical approach. Ecol Monogr. 1997; 67(3):345–66. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9615(1997)067[0345:SAAIST]2.0.CO;2

» https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9615(1997)067[0345:SAAIST]2.0.CO;2 - Espírito-Santo HMV, Magnusson WE, Zuanon J, Mendonça FP, Landeiro VL. Seasonal variation in the composition of fish assemblages in small Amazonian forest streams: evidence for predictable changes. Freshwater Biol. 2009; 54(3):536–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.2008.02129.x

» https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.2008.02129.x - Ferreira E, Zuanon J, Santos G, Amadio S. A ictiofauna do Parque Estadual do Cantão, Estado do Tocantins, Brasil. Biota Neotrop. 2011; 11(2):277–84. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1676-06032011000200028

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S1676-06032011000200028 - de Francesco A, Carneiro C. Atlas dos impactos da UHE Belo Monte sobre a pesca. São Paulo: Instituto Sócio Ambiental; 2015. p.1–54. Available from: https://ox.socioambiental.org/sites/default/files/ficha-tecnica/node/202/edit/2018-06/atlas-pesca-bm.pdf

» https://ox.socioambiental.org/sites/default/files/ficha-tecnica/node/202/edit/2018-06/atlas-pesca-bm.pdf - Gaston KJ, Sarah FJ, Cantú-Salazar L, Cruz-Piñón G. The ecological performance of protected areas. Annu Rev Ecol Evol S. 2008; 39:93–113. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.39.110707.173529

» https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.39.110707.173529 - Gonçalves AP, Camargo M, Carneiro CC, Camargo ATP, Paula GJX, Giarrizzo T. A pesca de peixes ornamentais. In: Camargo M, Ghilardi R, editors. Entre a terra, as águas e os pescadores do médio rio Xingu: uma abordagem ecológica. Belém, Pará: 2009. p.235–64.

- Goulding M, Barthem R, Ferreira E. The Xingu and Tapajós rivers: clearwater reflections. In: Goulding M, Barthem R, Ferreira E, editors. The Smithsonian Atlas of the Amazon. Washington and London: Smithsonian Books, 2003. p.135–45.

- Herbert ME, McIntyre PB, Doran PJ, Allan JD, Abell R. Terrestrial reserve networks do not adequately represent aquatic ecosystems. Conserv Biol. 2010; 24(4):1002–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01460.x

» https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01460.x - Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio). Plano de manejo da reserva extrativista do rio Iriri, Altamira – PA [Internet]. 2010. Available from: https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/stories/imgs-unidades-coservacao/PM%20Resex%20do%20Rio%20Iriri%202011.pdf

» https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/stories/imgs-unidades-coservacao/PM%20Resex%20do%20Rio%20Iriri%202011.pdf - Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio). Plano de manejo participativo da reserva extrativista rio Xingu, Altamira – PA [Internet]. 2012. Available from: https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/stories/imgs-unidades-coservacao/PM-RESEX-Rio-Xingu-2012.pdf

» https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/stories/imgs-unidades-coservacao/PM-RESEX-Rio-Xingu-2012.pdf - Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio). Livro Vermelho da Fauna Brasileira Ameaçada de Extinção. Vol. I, 1th ed., Brasília: ICMBio/MMA; 2018. Available from: https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/stories/comunicacao/publicacoes/publicacoes-diversas/livro_vermelho_2018_vol1.pdf

» https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/images/stories/comunicacao/publicacoes/publicacoes-diversas/livro_vermelho_2018_vol1.pdf - Jézéquel C, Tedesco PA, Bigorne R, Maldonado-Ocampo JA, Ortega H, Hidalgo M et al A database of freshwater fish species of the Amazon Basin. Sci Data. 2020; 7(96):1–09. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-0436-4

» https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-0436-4 - Lees AC, Peres CA, Fearnside PM, Schneider M, Zuanon JAS Hydropower and the future of Amazonian biodiversity. Biodivers Conserv. 2016; 25:451–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-016-1072-3

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-016-1072-3 - Legendre P, Gallagher ED. Ecologically meaningful transformations for ordination of species data. Oecologia. 2001; 129(2):271–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420100716

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420100716 - Legendre P, Legendre L. Numerical Ecology. Developments in Environmental Modelling. Vol. 24: Elsevier; 2012.

- Lujan NK, Winemiller KO, Armbruster JW. Trophic diversity in the evolution and community assembly of loricariid catfishes. BMC Evol Biol. 2012; 12(124):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-12-124

» https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-12-124 - Mesquita EMC, Isaac-Nahum VJ. Traditional knowledge and artisanal fishing technology on the Xingu River in Pará, Brazil. Braz J Biol. 2015; 75(3 suppl 1):138–57. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.01314BM

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.01314BM - Prang G An industry analysis of the freshwater ornamental fishery with particular reference to the supply of Brazilian freshwater ornamentals to the UK market. UAKARI. 2007; 3(1):7–51.

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing, Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2016. Available from: https://www.r-project.org/

» https://www.r-project.org/ - Ramos FM, Araújo MLG, Prang G, Fujimoto RY. Ornamental fish of economic and biological importance to the Xingu River. Braz J Biol. 2015; 75(3 suppl 1):95–98. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.02614BM

» https://doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.02614BM - Reis RE, Kullander SO, Ferraris CJ Jr, editors Check list of the freshwater fishes of South and Central America. Porto Alegre: Edipucrs; 2003.

- Roman APO. Biologia reprodutiva e dinâmica populacional de Hypancistrus zebra Isbrücker & Nijssen, 1991 (Siluriformes, Loricariidae), no rio Xingu, Amazônia brasileira. [Master Dissertation]. Belém: Universidade Federal do Pará; 2011. Available from: http://repositorio.ufpa.br/jspui/handle/2011/3499

» http://repositorio.ufpa.br/jspui/handle/2011/3499 - Sabaj-Pérez MH Where the Xingu bends and will soon break. Am Sc. 2015; 103(6):395–403. https://doi.org/10.1511/2015.117.395

» https://doi.org/10.1511/2015.117.395 - Sawakuchi AO, Hartmann GA, Sawakuchi HO, Pupim FN, Bertassoli DJ, Parra M et al The Volta Grande do Xingu: reconstruction of past environments and forecasting of future scenarios of a unique Amazonian fluvial landscape. Sci Dril. 2015; 20:21–32. https://doi.org/10.5194/sd-20-21-2015

» https://doi.org/10.5194/sd-20-21-2015 - Silva JC, Gubiani ÉA, Piana PA, Delariva RL. Effects of a small natural barrier on the spatial distribution of the fish assemblage in the Verde River, Upper Paraná River basin, Brazil. Braz J Biol. 2016; 76(4):851–63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.01215

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.01215 - Silveira LF, Beisiegel BM, Curcio FF, Valdujo PH, Dixo M, Verdade VK et al What use do Fauna Inventorie serve? Estud Av. 2010; 24(68):173–207. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-40142010000100015

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-40142010000100015 - Súarez YR. Variação espacial e temporal na diversidade e composição de espécies de peixes em riachos da bacia do rio Ivinhema, alto rio Paraná. Biota Neotrop. 2008; 8(3):197–204. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-40142010000100015

» https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-40142010000100015 - Torrente-Vilara G, Queiroz LJ, Ohara WM. Um breve histórico sobre o conhecimento da fauna de peixes do Rio Madeira. In: Queiroz LJ, Torrente-Vilara G, Ohara WM, Pires THS, Zuanon J, Doria CRC, organizers. Peixes do Rio Madeira - Vol. I. São Paulo: Dialeto Latin American Documentary; 2013. p.19–25.

- Torres M, Giarrizzo T, Carvalho-Júnior J, Aviz D, Ataíde M, Andrade M. Diagnóstico, tendência, potencial e políticas públicas da estrutura institucional para o desenvolvimento da pesca ornamental. In: Diagnóstico da pesca e da aquicultura do Estado do Pará. Belém: 2008; 5:45–54. Available from: https://elibrary.tips/edoc/nucleo-de-altos-estudos-amazonicos.html

» https://elibrary.tips/edoc/nucleo-de-altos-estudos-amazonicos.html - Winemiller KO, McIntyre PB, Castello L, Fluet-Chouinard E, Giarrizzo T, Nam S et al Balancing hydropower and biodiversity in the Amazon, Congo, and Mekong. Science. 2016; 351(6269):128–29. Available from https://science.sciencemag.org/content/351/6269/128/tab-pdf

» https://science.sciencemag.org/content/351/6269/128/tab-pdf - Zuanon JAS. História natural da ictiofauna de corredeiras do Rio Xingu, na região de Altamira, Pará. [PhD Thesis]. São Paulo: Universidade Estadual de Campinas; 1999. Available from: http://bdtd.ibict.br/vufind/Record/CAMP_518e0559dbba98f24df044290e046b26

» http://bdtd.ibict.br/vufind/Record/CAMP_518e0559dbba98f24df044290e046b26

ADDITIONAL NOTES

-

HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE

Lucena MDL, Pereira TS, Gonçalves AP, Silva KD, Sousa LM. Diversity of Loricariidae (Actinopterygii: Siluriformes) assemblages in two Conservation Areas of the Middle Xingu River, Brazilian Amazon, and their suitability for sustainable ornamental fisheries. Neotrop Ichthyol. 2021; 19(2):e200100. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-0224-2020-0100

Edited-by

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

09 July 2021 -

Date of issue

2021

History

-

Received

14 Nov 2020 -

Accepted

14 June 2021