ABSTRACT

Bean weevil [Acanthoscelides obtectus Say (Coleoptera: Bruchidae)] is considered the main storage pest of the bean crop. Its control is performed mainly by chemical treatment, which has potential to cause resistance in pests, as well as environmental contamination. This study aimed at evaluating the insecticidal and repellent effect of Salvia officinalis L. essential oil against bean weevil. The doses used for the insecticidal test were: 0 L t-1, 0.5 L t-1, 1.0 L t-1, 1.5 L t-1, 2.5 L t-1 and 5.0 L t-1 of bean grains. For the mortality test, the experimental design was completely randomized, in a 6 × 7 (dose × time) factorial scheme, with five replications. The number of dead insects was counted at 2, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h after the insect introduction. The repellency test was conducted in arenas, under a completely randomized design, using the same doses applied to evaluate the insecticidal effect. Counts were performed 24 h after the introduction of insects. The insecticidal effect of the S. officinalis essential oil on A. obtectus resulted in mortality rates higher than 95 %, after 6 h of insect introduction, for all doses tested. Repellency effect was also detected for all doses tested.

KEY-WORDS:

Acanthoscelides obtectus; Phaseolus vulgaris L.; storage pests; bioactive plants

RESUMO

O caruncho do feijão [Acanthoscelides obtectus Say (Coleoptera: Bruchidae)] é considerado a principal praga de armazenagem da cultura do feijão, sendo o seu controle realizado, principalmente, por meio de tratamento químico, o qual possui potencial para causar resistência em pragas, bem como contaminação ambiental. Objetivou-se avaliar o efeito inseticida e repelente do óleo essencial de Salvia officinalis L. sobre o caruncho do feijão. As doses testadas para o ensaio inseticida foram: 0 L t-1; 0,5 L t-1; 1,0 L t-1; 1,5 L t-1; 2,5 L t-1; e 5,0 L t-1 de grãos de feijão. Para o teste de mortalidade, o delineamento experimental utilizado foi o inteiramente casualizado, em esquema fatorial 6 x 7 (dose x tempo), com cinco repetições. A contagem do número de insetos mortos foi realizada às 2, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72 e 96 h após a introdução dos insetos. O teste de repelência foi conduzido em arenas, sob delineamento inteiramente casualizado, sendo utilizadas as mesmas doses citadas para avaliar o efeito inseticida. As contagens foram realizadas 24 h após a introdução dos insetos. O efeito inseticida do óleo essencial de S. officinalis sobre A. obtectus resultou em taxas de mortalidade superiores a 95 %, após 6 h da introdução dos insetos, para todas as doses testadas. Efeito de repelência também foi constatado para todas as doses testadas.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE:

Acanthoscelides obtectus; Phaseolus vulgaris L.; pragas de armazenagem; plantas bioativas

INTRODUCTION

Brazil is one of the world's major producers of beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). For this reason, the crop has an economic and social importance for many farmers, since it can be grown in different regions of the country (Smiderle et al. 2014SMIDERLE, E. C. et al. Tamanho de parcelas experimentais para a seleção de genótipos na cultura do feijoeiro. Comunicata Scientiae, v. 5, n. 1, p. 51-58, 2014.).

Insect pests attack different developmental stages of beans in the field, as well as in storage. The bean weevil (Acanthoscelides obtectus) is a pest that occurs mainly in temperate regions and has a potential for cross infestation, causing direct losses in grain quantity and quality, and indirect losses as vectors of storage fungi (Gallo et al. 2002GALLO, D. et al. Entomologia agrícola. Piracicaba: Fealq, 2002., Lorini et al. 2010LORINI, I. et al. Principais pragas e métodos de controle em sementes durante o armazenamento: série sementes. Londrina: Embrapa Soja, 2010.).

Chemical methods are commonly used to control A. obtectus in stored grains. Phosphine is the main molecule used for controlling bean weevil. However, chemical control is associated with the increase in resistance of storage pests, and has a high potential to cause environmental pollution and poisoning, especially in the applicants (Soares et al. 2009SOARES, M. A. et al. Controle biológico de pragas em armazenamento: uma alternativa para reduzir o uso de agrotóxicos no Brasil? Unimontes Científica, v. 11, n. 1, p. 52-59, 2009.). Furthermore, the adoption of alternative control methods is important, given the increasing demands for high quality food exempted from the application of chemical inputs, and the increase in organic areas and agroecological farming (Lima Júnior et al. 2012LIMA JÚNIOR, A. F. et al. Controle de pragas de grãos armazenados: uso e aplicação de fosfetos. Revista Faculdade Montes Belos, v. 5, n. 4, p. 180-194, 2012.).

Among the alternatives to control this pest, the essential oils extracted from plants stand out with confirmed efficiency. Hypothenemus hampei Ferrari (Coleoptera, Scolytidae) has been controlled using Schinus terebinthifolius essential oil (Santos et al. 2013SANTOS, M. R. A. et al. Composição química e atividade inseticida do óleo essencial de Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi (Anacardiaceae) sobre a broca-do-café (Hypothenemus hampei) Ferrari. Revista Brasileira de Plantas Medicinais, v. 15, n. 4, p. 757-762, 2013.) and Zabrotes subfaciatus Boheman (Coleoptera: Bruchidae) using Laurus nobilis essential oils (Silva et al. 2013SILVA, J. F. et al. Extratos vegetais para o controle do caruncho-do-feijão Zabrotes subfaciatus (Boheman 1833) (Coleoptera:Bruchidae). Revista Verde de Agroecologia e Desenvolvimento Sustentável, v. 8, n. 3, p. 1-5, 2013.). Moreover, due to the fact that essential oils are composed of different substances, they can be important tools for insect resistance management, since these compounds may act on different physiological routes of the insect (Bakkali et al. 2008BAKKALI, F. et al. Biological effects of essential oils: a review. Food and Chemical Toxicology, v. 46, n. 1, p. 446-475, 2008., Regnault-Roger et al. 2012REGNAULT-ROGER, C. et al. Essential oils in insect control: low-risk products in a high-stakes world. Annual Review of Entomology, v. 57, n. 1, p. 405-424, 2012.).

Salvia officinalis L. has the potential for essential oil extraction, and it can be cultivated under Brazilian soil and weather conditions. The insecticide potential of S. officinalis has been already verified in Spodoptera littoralis Boisduval (Noctuidae: Lepidoptera) (Souguir et al. 2013SOUGUIR, S. et al. Cultivated aromatic plants against Spodoptera littoralis (Boisd). Journal of Plant Protection Research, v. 53, n. 4, p. 388-391, 2013.). However, there are few studies on S. officinalis essential oil activity on insects. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated its acaricide potential on Tetranychus urticae (Acari: Tetranychidae) and fungicide activity against Alternaria spp. and Phakopsora pachyrhizi (Dellavalle et al. 2011DELLAVALLE, P. D. et al. Antifungal activity of medicinal plant extracts against phytopathogenic fungus Alternaria spp. Chilean Journal of Agricultural Research, v. 71, n. 2, p. 231-239, 2011., Borges et al. 2013BORGES, D. I. et al. Efeito de extratos e óleos essenciais de plantas na germinação de urediniósporos de Phakopsora pachyrhizi. Revista Brasileira de Plantas Medicinais, v. 15, n. 3, p. 325-331, 2013., Laborda et al. 2013LABORDA, R. et al. Effects of Rosmarinus officinalis and Salvia officinalis essential oils on Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae). Industrial Crops and Products, v. 48, n. 1, p. 106-110, 2013.).

In this context, the present study aimed at evaluating the insecticide and repellent effects of S. officinalis essential oil on bean weevil (A. obtectus).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The experiment was conducted at the Universidade Federal da Fronteira Sul, in Erechim, Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil, in January 2014, in BOD chambers with 25 ºC ± 2 ºC and relative humidity (RH) of 70 % ± 10 %, with a 12-h photoperiod.

Plants were collected in the Alto Uruguai region and shade dried until constant weight. Then, the essential oil was extracted by hydrodistillation, using a Clevenger apparatus, with extraction time of 2 h.

The insects used were obtained by laboratory rearing conducted in glass pots covered with fabric and maintained in BOD chamber at 25 ºC ± 2 ºC, under relative humidity of 70 % ± 10 %. Creole bean grains were used as substrate, free from treatment with insecticides and disinfected in ultrafreezer at -50 ºC, for 48 h.

The mortality test was conducted under completely randomized design, in a 6 × 7 (dose × time) factorial scheme, with five replications. For the test, 20 g samples of bean grains were put in plastic pots (6.8 cm diameter and 7 cm height). Subsequently, pure essential oil was applied on the grains, using an automatic pipettor, at doses of 0 µL 20 g-1, 10 µL 20 g-1, 20 µL 20 g-1, 30 µL 20 g-1, 50 µL 20 g-1 and 100 µL 20 g-1 of grains, which correspond to values equivalent to 0.0 L t-1, 0.5 L t-1, 1.0 L t-1, 1.5 L t-1, 2.5 L t-1 and 5.0 L t-1 of grains, respectively. Uniform oil distribution to the grains was achieved by hand shaking, for 1 min. After applying the essential oil, 20 unsexed adult insects, aged between 20 and 40 days, were put in each pot. Dead weevils were counted and recorded at 2, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h after insect introduction. The data were adjusted as described by Abbott (1925)ABBOTT, W. S. A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. Journal of Economic Entomology, v. 18, n. 1, p. 265-267, 1925., with results expressed as percentage of dead insects.

The repellency test was conducted in arenas under completely randomized design, with five replications. Each arena consisted of six plastic pots (6.8 cm diameter and 7 cm height) arranged symmetrically and diagonally to a central pot, and interconnected by plastic tubes (Figure 1). The doses were the same used to evaluate the insecticide effect and each replicate consisted of one arena (Mazzonetto & Vendramim 2003MAZZONETTO, F.; VENDRAMIM, J. D. Efeito de pós de origem vegetal sobre Acanthoscelides obtectus (Say) (Coleoptera: Bruchidae) em feijão armazenado. Neotropical Entomology, Londrina, v. 32, n. 1, p. 145-149, 2003., Procópio et al. 2003PROCÓPIO, S. O. et al. Bioatividade de diversos pós de origem vegetal em relação a Sitophilus zeamais Most. (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Ciência e Agrotecnologia, v. 27, n. 6, p. 1231-1236, 2003., Tavares & Vendramim 2005TAVARES, M. A. G. C.; VENDRAMIM, J. D. Bioatividade da erva-de-santa-maria, Chenopodium ambrosioides L., sobre Sitophilus zeamais Mots. (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Neotropical Entomology, v. 34, n. 2, p. 319-323, 2005.).

In each pot (1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6), 20 g of bean grains pre-impregnated with each oil dose were randomly deposited. Oil application on the grain was conducted in the same way as described for the mortality test. Then, in the central pot (C), 50 adult insects not sexed, aged between 20 and 40 days, were introduced. The evaluation was performed 24 h after insect introduction. The number of insects present in each pot was counted and the results expressed as percentage of repellency. Furthermore, the repellency data were evaluated using the Preference Index (PI), as proposed by Procópio et al. (2003)PROCÓPIO, S. O. et al. Bioatividade de diversos pós de origem vegetal em relação a Sitophilus zeamais Most. (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Ciência e Agrotecnologia, v. 27, n. 6, p. 1231-1236, 2003., described by the following equation:

where: PI = -1.00 to -0.10: plant test repellent; PI = -0.10 to +0.10: plant test neutral; PI = +0.10 to +1.00: plant test attractive.

Mortality and repellency percentage data were submitted to analysis of variance by the F test, with the Statistica 10.0 software. Mortality data were analyzed employing the response surface methodology, with the Table Curve 3D 4.0 software. The percent repellency results were submitted to regression analysis, with the Sigma Plot 10.0 software.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The results showed that the S. officinalis essential oil has insecticidal effect on A. obtectus. According to the response surface graph (Figure 2), insect mortality was high for all doses. Mortality varied with varying exposure time. Regardless of the dose used, A. obtectus mortality was not satisfactory before 2 h of exposure into impregnated beans. However, from 6 h, exposure mortality rates were higher than 95 % for all doses tested.

Acanthoscelides obtectus mortality after Salvia officinalis essential oil application. Z = 100.21 - 9.19/X + 3.13 * LnY - 4.21/X2 - 2.62 * (LnY)2 + 10.42 * LnY/X - 0.90/ X3 + 0.45 * (LnY)3 - 2.18 * (LnY)2/X + 1.87 * LnY/X2, with R2 = 0.71 and p < 0.0001, where: X = dose, Y = time, Z = mortality.

A. obtectus mortality rates higher than 95 % were also observed by Santos et al. (2007)SANTOS, M. R. A. et al. Atividade inseticida do óleo essencial de Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi sobre Acanthoscelides obtectus Say e Zabrotes subfasciatus Boheman. Porto Velho: Embrapa Rondônia, 2007. 48 h after the application of Schinus terebinthifolius essential oil with dilutions higher than 10-2, and by Savaris et al. (2012)SAVARIS, M. et al. Atividade inseticida de Cunila angustifolia sobre adultos de Acanthoscelides obtectus em laboratório. Ciencia y Tecnología, v. 5, n. 1, p. 1-5, 2012. after 24 h of Cunila angustifolia essential oil application at doses greater than 0.001 mL cm-2. Campos et al. (2014)CAMPOS, A. C. T. de et al. Atividade repelente e inseticida do óleo essencial de carqueja doce sobre o caruncho do feijão. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental, v. 18, n. 8, p. 861-865, 2014. observed, after 2 h of insect infestation, a mortality rate higher than 95 %, when Baccharis articulata essential oil at a dose of 5.0 L t-1 of grains was applied.

The insecticidal action mechanism of essential oils can occur in different ways, causing mortality, deformations in different developmental stages and repellency (Knaak & Fiúza 2010KNAAK, N.; FIÚZA, L. M. Potencial dos óleos essenciais de plantas no controle de insetos e micro-organismos. Neotropical Biology and Conservation, v. 5, n. 2, p. 120-132, 2010.). The toxic effect of essential oils involves many factors, such as the toxins entrance point, which can occur by inhalation routes, ingestion and contact (Regnault-Roger 1997REGNAULT-ROGER, C. The potential of botanical essential oils for insect pest control. Integrated Pest Management Reviews, v. 2, n. 1, p. 25-34, 1997.). Therefore, the toxicity caused to insects probably occurred through contact action of the essential oil and inhalation, because adult A. obtectus does not feed. In addition, the insecticidal action can be directly related to the monoterpenes present in the essential oil, which act mainly on the insect acetylcholinesterase inhibition (Viegas Júnior 2003VIEGAS JÚNIOR, C. Terpenos com atividade inseticida: uma alternativa para o controle químico de insetos. Química Nova, v. 26, n. 3, p. 390-400, 2003.).

According to Pierozan et al. (2009)PIEROZAN, M. K. et al. Chemical characterization and antimicrobial activity of essential oils of Salvia L. species. Ciência e Tecnologia de Alimentos, v. 29, n. 4, p. 764-770, 2009., the oil from S. officinalis cultivated in southern Brazil has as major compounds α-thujone, camphor and 1,8-cineol. Thus, the insecticidal action exerted by the S. officinalis essential oil against A. obtectus is possibly associated with the presence of these compounds.

The α-thujone compound is classified as a neurotoxic pesticide (Ratra et al. 2001RATRA, G. S. et al. Role of human GABAA receptor β3 subunit in insecticide toxicity. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, v. 172, n. 1, p. 233-240, 2001.). The insecticidal activity of this compound was demonstrated by Rojht et al. (2009)ROJHT, H. et al. Insecticidal activity of four different substances against larvae and adults of sycamore lace bug (Corythucha ciliata [Say], Heteroptera, Tingidae). Acta Agriculturae Slovenica, v. 93, n. 1, p. 31-36, 2009. on Corythucha ciliata Say (Heteroptera: Tingidae), Pavlidou et al. (2004)PAVLIDOU, V. et al. Insecticidal and genotoxic effects of essential oils of greek sage, Salvia fruticosa, and mint, Mentha pulegium, on Drosophila melanogaster and Bactrocera oleae (Diptera: Tephritidae). Journal of Agricultural and Urban Entomology, v. 21, n. 1, p. 39-49, 2004. on Drosophila melanogaster Fallén (Diptera: Drosophilidae) and Bactrocera oleae Rossi (Diptera: Tephritidae), and Creed et al. (2015)ROSSI, Y. E.; PALACIOS, S. M. Insecticidal toxicity of Eucalyptus cinerea essential oil and 1,8-cineole against Musca domestica and possible uses according to the metabolic response of flies. Industrial Crops and Products, v. 63, n. 1, p. 133-137, 2015. on Cydia pomonella Linnaeus (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae).

The insecticidal effect of the Rosmarinus officinalis essential oil, which has 20.8 % of camphor, was observed on A. obtectus by Papachristos et al. (2004)PAPACHRISTOS, D. P. et al. The relationship between the chemical composition of three essential oils and their insecticidal activity against Acanthoscelides obtectus (Say). Pest Management Science, v. 60, n. 1, p. 514-520, 2004.. In addition, studies by Lamiri et al. (2001)LAMIRI, A. et al. Insecticidal effects of essential oils against Hessian fly, Mayetiola destructor (Say). Field Crop Research, v. 71, n. 1, p. 9-15, 2001. on the control of Mayetiola destructor Say (Diptera: Cecidomyiideae) and Chu et al. (2010)CHU, S. S. et al. Insecticidal activity and chemical composition of the essential oil of Artemisia vestita from China against Sitophilus zeamais. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology, v. 38, n. 1, p. 489-492, 2010. on Sitophilus zeamais Linnaeus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), with the application of the Artemisia herba-alba (60.8 % camphor) and Artemisia vestita (11.3 % camphor) essential oils, respectively, showed the camphor insecticidal action.

The pesticide action of the 1,8-cineole compound was found in studies by Lima et al. (2011)LIMA, R. K. et al. Chemical composition and fumigant effect of essential oil of Lippia sidoides Cham. and monoterpenes against Tenebrio molitor (L.) (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). Ciência e Agrotecnologia, v. 35, n. 4, p. 664-671, 2011. on Tenebrio molitor Linnaeus (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) and Rossi & Palacios (2015)ROSSI, Y. E.; PALACIOS, S. M. Insecticidal toxicity of Eucalyptus cinerea essential oil and 1,8-cineole against Musca domestica and possible uses according to the metabolic response of flies. Industrial Crops and Products, v. 63, n. 1, p. 133-137, 2015. on Musca domestica Linnaeus (Diptera: Muscidae). Moreover, 1,8-cineole has proven insecticidal effect on Callosobruchus maculatus Fabricius (Coleoptera: Bruchidae), Rhyzopertha dominica Fabricius (Coleoptera: Bostrychidae) and Sitophilus oryzae Linnaeus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) (Aggarwal et al. 2001AGGARWAL, K. K. et al. Toxicity of 1,8-cineole towards three species of stored product coleopterans. International Journal of Tropical Insect Science, v. 21, n. 2, p. 155-160, 2001.). Against A. obtectus, the study by Bittner et al. (2008)BITTNER, M. L. et al. Effects of essential oils from five plant species against the granary weevils Sitophilus zeamais and Acanthoscelides obtectus (Coleoptera). Journal of the Chilean Chemical Society, v. 53, n. 1, p. 1455-1459, 2008. showed that the Gomortega Keule essential oil, whose composition has about 35 % of 1,8-cineole, caused a mortality rate of 100 %, after 96 h, when applying the dose of 8 µL L air-1 in fumigation.

Furthermore, the association between 1,8-cineole and camphor compounds promotes synergistic effect, thereby increasing the penetration of these components in the cuticle of insects (Tak & Isman 2015TAK, J.; ISMAN, M. B. Enhanced cuticular penetration as the mechanism for synergy of insecticidal constituents of rosemary essential oil in Trichoplusia ni. Scientific Reports, v. 5, n. 1, p. 1-10, 2015.).

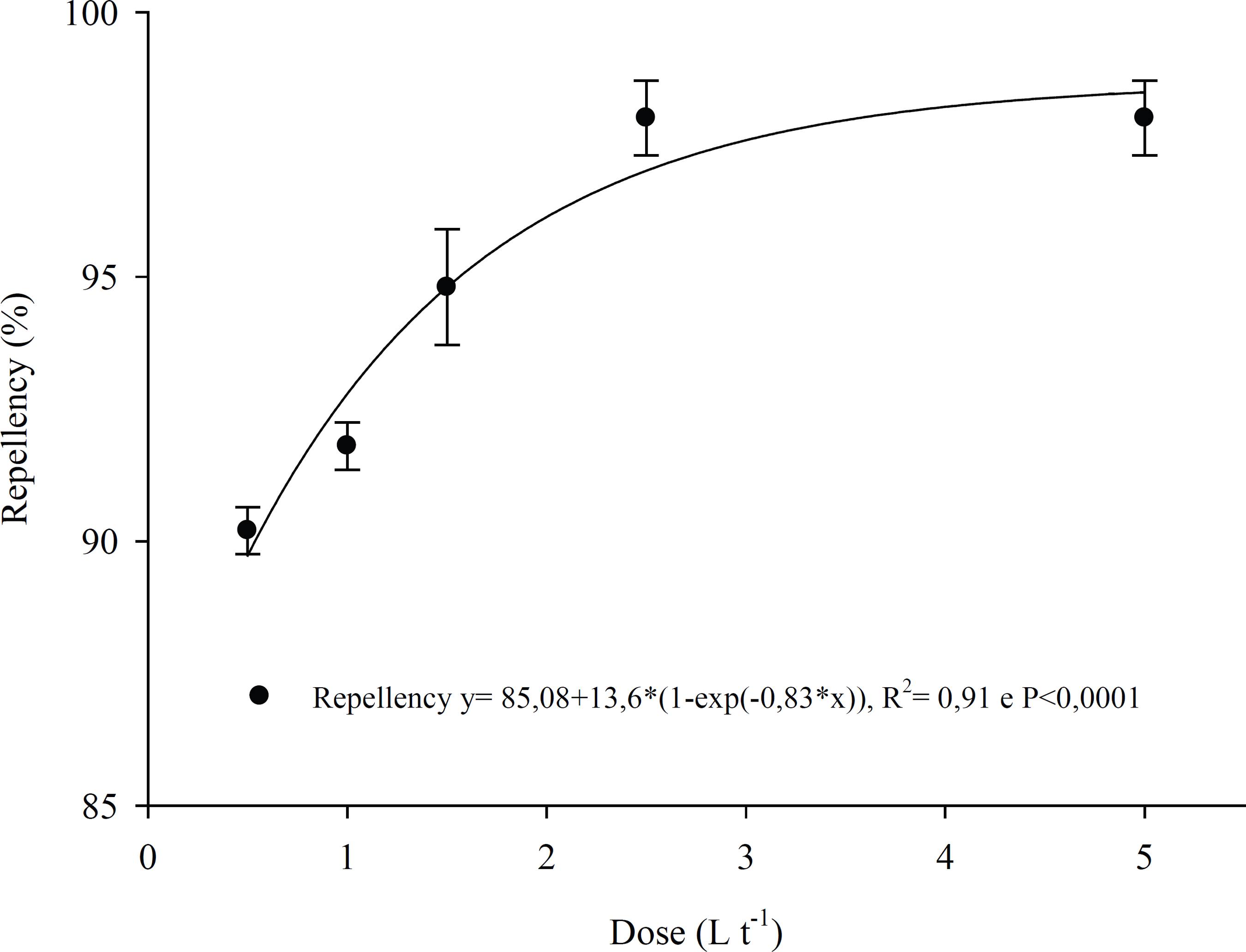

According to the Preference Index, all doses of S. officinalis essential oil tested showed repellency for A. obtectus. The higher the dose the higher the repellency rate (Figure 3).

Repellency Index of Salvia officinalis essential oil on Acanthoscelides obtectus, according to the Preference Index (-1.00 to -0.10 = plant test repellent; -0.10 to +0.10 = plant test neutral; +0.10 to +1.00 = plant test attractive).

The regression model shows an increase in the percentage of insect repellency with increasing doses of S. officinalis essential oil (Figure 4). All doses obtained repellency rates above 90 %, 24 h after insect inoculation.

Percentage of repellency of Acanthoscelides obtectus after application of Salvia officinalis essential oil.

Jumbo et al. (2014)JUMBO, L. O. V. et al. Potential use of clove and cinnamon essential oils to control the beanweevil, Acanthoscelides obtectus Say, in small storage units. Industrial Crops and Products, v. 56, n. 1, p. 27-34, 2014. also observed a repellent action against A. obtectus with the application of Cinnamomum zeylanicum essential oil at doses of 46.8 µL kg-1 and 122.4 µL kg-1 in beans. Likewise, Papachristos & Stamopoulos (2002)PAPACHRISTOS, D. P.; STAMOPOULOS, D. C. Repellent, toxic and reproduction inhibitory effects of essential oil vapours on Acanthoscelides obtectus (Say) (Coleoptera: Bruchidae). Journal of Stored Products Research, v. 38, n. 1, p. 117-128, 2002. found that the essential oils of Mentha microphylla, Mentha viridis, Lavandula hybrida and Rosmarinus officinalis promoted repellency on A. obtectus. Campos et al. (2014)CAMPOS, A. C. T. de et al. Atividade repelente e inseticida do óleo essencial de carqueja doce sobre o caruncho do feijão. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental, v. 18, n. 8, p. 861-865, 2014. observed repellency of Baccharis trimera essential oil on A. obtectus at doses above 0.5 L t-1.

The repellent activity caused by essential oils in insects is mainly due to the major compounds present in its composition (Knaak & Fiúza 2010KNAAK, N.; FIÚZA, L. M. Potencial dos óleos essenciais de plantas no controle de insetos e micro-organismos. Neotropical Biology and Conservation, v. 5, n. 2, p. 120-132, 2010.), through contact action, interacting with the insect integument, as well as acting in digestive and neurological enzymes (Soares et al. 2012SOARES, C. S. A. et al. Atividade inseticida de óleos essenciais sobre Macrosiphum euphorbiae (Thomas) (Hemiptera: Aphididae) em roseira. Revista Brasileira de Agroecologia, v. 7, n. 1, p. 169-175, 2012.). Thus, the S. officinalis essential oil repellent action on A. obtectus can also be attributed to the presence of α-thujone, camphor and 1,8-cineole compounds. Furthermore, the synergistic effect between camphor and 1,8-cineole could increase the penetration of these constituents in the insect integument, as aforementioned.

According to Nerio et al. (2010)NERIO, L. S. et al. Repellent activity of essential oils: a review. Bioresource Technology, v. 101, n. 1, p. 372-378, 2010., the camphor compound has a high repellent activity on insects. Zhang et al. (2014)ZHANG, N. et al. Insecticidal, fumigant, and repellent activities of sweet wormwood oil and its individual components against red imported fire ant workers (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Journal of Insect Science, v. 14, n. 241, p. 1-6, 2014. found that, when camphor was applied alone, it had a repellent effect on Solenopsis invicta Buren (Hymenoptera: Formicidae).

Tampe et al. (2015)TAMPE, J. et al. Repellent effect and metabolite volatile profile of the essential oil of Achillea millefolium against Aegorhinus nodipennis (Hope) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Neotropical Entomology, v. 44, n. 1, p. 279-285, 2015. showed that the α-thujone compound presented a repellent effect when applied alone on Aegorhinus nodipennis Hope (Coleoptera: Curculionidae).

Aggarwal et al. (2001)AGGARWAL, K. K. et al. Toxicity of 1,8-cineole towards three species of stored product coleopterans. International Journal of Tropical Insect Science, v. 21, n. 2, p. 155-160, 2001. concluded that 1,8-cineole showed repellency rates higher than 70 % on C. maculatus and R. dominica, at the dose of 4 µL mL-1, 1 h after application. However, there are few studies about the effects of these compound on A. obtectus, thus underlining the importance of further research in this context.

CONCLUSIONS

-

The Salvia officinalis essential oil has insecticide and repellent effects on Acanthoscelides obtectus.

-

Doses of S. officinalis essential oil greater than 0.5 L t-1 of grains increase mortality rates above 95 %, 6 h after application.

-

S. officinalis essential oil applied with 0.5 L t-1 of grains induces a repellency rate above 90 % for A. obtectus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the assistance of the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul (FAPERGS), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Capes) and Financiadora de Estudos e Projetos (Finep).

REFERENCES

- ABBOTT, W. S. A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. Journal of Economic Entomology, v. 18, n. 1, p. 265-267, 1925.

- AGGARWAL, K. K. et al. Toxicity of 1,8-cineole towards three species of stored product coleopterans. International Journal of Tropical Insect Science, v. 21, n. 2, p. 155-160, 2001.

- BAKKALI, F. et al. Biological effects of essential oils: a review. Food and Chemical Toxicology, v. 46, n. 1, p. 446-475, 2008.

- BITTNER, M. L. et al. Effects of essential oils from five plant species against the granary weevils Sitophilus zeamais and Acanthoscelides obtectus (Coleoptera). Journal of the Chilean Chemical Society, v. 53, n. 1, p. 1455-1459, 2008.

- BORGES, D. I. et al. Efeito de extratos e óleos essenciais de plantas na germinação de urediniósporos de Phakopsora pachyrhizi. Revista Brasileira de Plantas Medicinais, v. 15, n. 3, p. 325-331, 2013.

- CAMPOS, A. C. T. de et al. Atividade repelente e inseticida do óleo essencial de carqueja doce sobre o caruncho do feijão. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental, v. 18, n. 8, p. 861-865, 2014.

- CHU, S. S. et al. Insecticidal activity and chemical composition of the essential oil of Artemisia vestita from China against Sitophilus zeamais. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology, v. 38, n. 1, p. 489-492, 2010.

- CREED, C. et al. Artemisia arborescens ''Powis Castle'' extracts and α-thujone prevent fruit infestation by codling moth neonates. Pharmaceutical Biology, v. 1, n. 1, p. 1-7, 2015.

- DELLAVALLE, P. D. et al. Antifungal activity of medicinal plant extracts against phytopathogenic fungus Alternaria spp. Chilean Journal of Agricultural Research, v. 71, n. 2, p. 231-239, 2011.

- GALLO, D. et al. Entomologia agrícola Piracicaba: Fealq, 2002.

- JUMBO, L. O. V. et al. Potential use of clove and cinnamon essential oils to control the beanweevil, Acanthoscelides obtectus Say, in small storage units. Industrial Crops and Products, v. 56, n. 1, p. 27-34, 2014.

- KNAAK, N.; FIÚZA, L. M. Potencial dos óleos essenciais de plantas no controle de insetos e micro-organismos. Neotropical Biology and Conservation, v. 5, n. 2, p. 120-132, 2010.

- LABORDA, R. et al. Effects of Rosmarinus officinalis and Salvia officinalis essential oils on Tetranychus urticae Koch (Acari: Tetranychidae). Industrial Crops and Products, v. 48, n. 1, p. 106-110, 2013.

- LAMIRI, A. et al. Insecticidal effects of essential oils against Hessian fly, Mayetiola destructor (Say). Field Crop Research, v. 71, n. 1, p. 9-15, 2001.

- LIMA JÚNIOR, A. F. et al. Controle de pragas de grãos armazenados: uso e aplicação de fosfetos. Revista Faculdade Montes Belos, v. 5, n. 4, p. 180-194, 2012.

- LIMA, R. K. et al. Chemical composition and fumigant effect of essential oil of Lippia sidoides Cham. and monoterpenes against Tenebrio molitor (L.) (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). Ciência e Agrotecnologia, v. 35, n. 4, p. 664-671, 2011.

- LORINI, I. et al. Principais pragas e métodos de controle em sementes durante o armazenamento: série sementes. Londrina: Embrapa Soja, 2010.

- MAZZONETTO, F.; VENDRAMIM, J. D. Efeito de pós de origem vegetal sobre Acanthoscelides obtectus (Say) (Coleoptera: Bruchidae) em feijão armazenado. Neotropical Entomology, Londrina, v. 32, n. 1, p. 145-149, 2003.

- NERIO, L. S. et al. Repellent activity of essential oils: a review. Bioresource Technology, v. 101, n. 1, p. 372-378, 2010.

- PAPACHRISTOS, D. P. et al. The relationship between the chemical composition of three essential oils and their insecticidal activity against Acanthoscelides obtectus (Say). Pest Management Science, v. 60, n. 1, p. 514-520, 2004.

- PAPACHRISTOS, D. P.; STAMOPOULOS, D. C. Repellent, toxic and reproduction inhibitory effects of essential oil vapours on Acanthoscelides obtectus (Say) (Coleoptera: Bruchidae). Journal of Stored Products Research, v. 38, n. 1, p. 117-128, 2002.

- PAVLIDOU, V. et al. Insecticidal and genotoxic effects of essential oils of greek sage, Salvia fruticosa, and mint, Mentha pulegium, on Drosophila melanogaster and Bactrocera oleae (Diptera: Tephritidae). Journal of Agricultural and Urban Entomology, v. 21, n. 1, p. 39-49, 2004.

- PIEROZAN, M. K. et al. Chemical characterization and antimicrobial activity of essential oils of Salvia L. species. Ciência e Tecnologia de Alimentos, v. 29, n. 4, p. 764-770, 2009.

- PROCÓPIO, S. O. et al. Bioatividade de diversos pós de origem vegetal em relação a Sitophilus zeamais Most. (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Ciência e Agrotecnologia, v. 27, n. 6, p. 1231-1236, 2003.

- RATRA, G. S. et al. Role of human GABAA receptor β3 subunit in insecticide toxicity. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, v. 172, n. 1, p. 233-240, 2001.

- REGNAULT-ROGER, C. et al. Essential oils in insect control: low-risk products in a high-stakes world. Annual Review of Entomology, v. 57, n. 1, p. 405-424, 2012.

- REGNAULT-ROGER, C. The potential of botanical essential oils for insect pest control. Integrated Pest Management Reviews, v. 2, n. 1, p. 25-34, 1997.

- ROJHT, H. et al. Insecticidal activity of four different substances against larvae and adults of sycamore lace bug (Corythucha ciliata [Say], Heteroptera, Tingidae). Acta Agriculturae Slovenica, v. 93, n. 1, p. 31-36, 2009.

- ROSSI, Y. E.; PALACIOS, S. M. Insecticidal toxicity of Eucalyptus cinerea essential oil and 1,8-cineole against Musca domestica and possible uses according to the metabolic response of flies. Industrial Crops and Products, v. 63, n. 1, p. 133-137, 2015.

- SANTOS, M. R. A. et al. Atividade inseticida do óleo essencial de Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi sobre Acanthoscelides obtectus Say e Zabrotes subfasciatus Boheman Porto Velho: Embrapa Rondônia, 2007.

- SANTOS, M. R. A. et al. Composição química e atividade inseticida do óleo essencial de Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi (Anacardiaceae) sobre a broca-do-café (Hypothenemus hampei) Ferrari. Revista Brasileira de Plantas Medicinais, v. 15, n. 4, p. 757-762, 2013.

- SAVARIS, M. et al. Atividade inseticida de Cunila angustifolia sobre adultos de Acanthoscelides obtectus em laboratório. Ciencia y Tecnología, v. 5, n. 1, p. 1-5, 2012.

- SILVA, J. F. et al. Extratos vegetais para o controle do caruncho-do-feijão Zabrotes subfaciatus (Boheman 1833) (Coleoptera:Bruchidae). Revista Verde de Agroecologia e Desenvolvimento Sustentável, v. 8, n. 3, p. 1-5, 2013.

- SMIDERLE, E. C. et al. Tamanho de parcelas experimentais para a seleção de genótipos na cultura do feijoeiro. Comunicata Scientiae, v. 5, n. 1, p. 51-58, 2014.

- SOARES, C. S. A. et al. Atividade inseticida de óleos essenciais sobre Macrosiphum euphorbiae (Thomas) (Hemiptera: Aphididae) em roseira. Revista Brasileira de Agroecologia, v. 7, n. 1, p. 169-175, 2012.

- SOARES, M. A. et al. Controle biológico de pragas em armazenamento: uma alternativa para reduzir o uso de agrotóxicos no Brasil? Unimontes Científica, v. 11, n. 1, p. 52-59, 2009.

- SOUGUIR, S. et al. Cultivated aromatic plants against Spodoptera littoralis (Boisd). Journal of Plant Protection Research, v. 53, n. 4, p. 388-391, 2013.

- TAK, J.; ISMAN, M. B. Enhanced cuticular penetration as the mechanism for synergy of insecticidal constituents of rosemary essential oil in Trichoplusia ni. Scientific Reports, v. 5, n. 1, p. 1-10, 2015.

- TAMPE, J. et al. Repellent effect and metabolite volatile profile of the essential oil of Achillea millefolium against Aegorhinus nodipennis (Hope) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Neotropical Entomology, v. 44, n. 1, p. 279-285, 2015.

- TAVARES, M. A. G. C.; VENDRAMIM, J. D. Bioatividade da erva-de-santa-maria, Chenopodium ambrosioides L., sobre Sitophilus zeamais Mots. (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Neotropical Entomology, v. 34, n. 2, p. 319-323, 2005.

- VIEGAS JÚNIOR, C. Terpenos com atividade inseticida: uma alternativa para o controle químico de insetos. Química Nova, v. 26, n. 3, p. 390-400, 2003.

- ZHANG, N. et al. Insecticidal, fumigant, and repellent activities of sweet wormwood oil and its individual components against red imported fire ant workers (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Journal of Insect Science, v. 14, n. 241, p. 1-6, 2014.

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

Apr-Jun 2016

History

-

Received

Mar 2016 -

Accepted

June 2016