Abstracts

INTRODUCTION:

Most cancer patients are treated with chemotherapy, and peripheral neuropathy is a serious and common clinical problem affecting patients undergoing cancer treatment. However, the symptoms are subjective and underdiagnosed by health professionals. Thus, it becomes necessary to develop self-report instruments to overcome this limitation and improve the patient's perception about his medical condition or treatment.

OBJECTIVE:

Translate and culturally adapt the Brazilian version of the Pain Quality Assessment Scale, constituting a useful tool for assessing the quality of neuropathic pain in cancer patients.

METHOD:

The procedure followed the steps of translation, back translation, analysis of Portuguese and English versions by a committee of judges, and pretest. Pretest was conducted with 30 cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy following internationally recommended standards, and the final versions were compared and evaluated by a committee of researchers from Brazil and MAPI Research Trust, the scale's creators.

RESULTS:

Versions one and two showed 100% semantic equivalence with the original version. Back-translation showed difference between the linguistic translation and the original version. After evaluation by the committee of judges, a flaw was found in the empirical equivalence and idiomatic equivalence. In pretest, two people did not understand the item 12 of the scale, without interfering in the final elaboration.

CONCLUSION:

The translated and culturally adapted instrument is now presented in this publication, and currently it is in the process of clinical validation in Brazil.

Neuropathy; Chemotherapy; Self-report instruments; Translation; Cross-cultural adaptation

INTRODUÇÃO:

a maioria dos pacientes com câncer são tratados com quimioterápicos e a neuropatia periférica é um problema clínico sério e comum que afeta os pacientes em tratamento oncológico. Entretanto, tais sintomas são subjetivos sendo subdiagnosticado pelos profissionais de saúde. Assim, torna-se necessário o desenvolvimento de instrumentos de autorrelato para superar essa limitação e melhorar a percepção do paciente sobre o seu tratamento ou condição clínica.

OBJETIVO:

traduzir e adaptar transculturalmente a versão brasileira do Pain Quality Assessment Scale (PQAS), constituindo em um instrumento útil de avaliação da qualidade da dor neuropática em pacientes com câncer.

MÉTODO:

o procedimento seguiu as etapas de tradução, retrotradução, análise das versões português e inglês por um comitê de juízes e pré-teste. O pré-teste foi realizado em 30 pacientes com câncer em tratamento quimioterápico seguindo normas internacionalmente recomendadas, sendo as versões finais comparadas e avaliadas por comitê de pesquisadores brasileiros e da MAPI Research Trust, originadores da escala.

RESULTADOS:

as versões um e dois apresentaram 100% de equivalência semântica com a versão original. Na retrotradução houve diferenças na tradução linguística com a versão original. Após a avaliação do Comitê de Juízes, foi encontrada uma falha na equivalência empírica e na equivalência idiomática. No pré-teste, duas pessoas não entenderam o item 12 da escala, sem interferir na elaboração final da mesma.

CONCLUSÃO:

o instrumento agora traduzido e adaptado transculturalmente é apresentado nessa publicação e, atualmente, encontra-se em processo de validação clínica no Brasil.

Neuropatia; Quimioterapia; Instrumentos de auto-relato; Tradução; Adaptação transcultural

Introduction

Painful experiences are exactly alike. People use the word 'pain' to describe a wide variety of sensations and experiences arising from various etiologies Although the pain intensity or magnitude is the most evaluated characteristic on clinical experience and scientific research, currently we know that people can feel the same pain intensity, but with different qualities.11. Jensen MP, Galer BS, Gammaitomi AR, et al. The Pain Quality Assessment Scale (PQAS) and Revised Pain Quality Assessment Scale (PQAS-R): Manual and User Guide; 2010. Mapi Research Trust website (http://www.mapi-trust.org).

http://www.mapi-trust.org...

Most cancer patients are treated with chemotherapy. Bone marrow suppression and renal and neurologic toxicity are the most common adverse events seen after the use of chemotherapeutic agents for treating malignancies and the main reasons for anticancer treatment discontinuation or changing the treatment regimen. The neurotoxicity, involving both the peripheral and the central nervous system, tends to occur early and persist even with the chemotherapy reduction or discontinuation.22. Quasthoff S, Hartung HP. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. J Neurol. 2002;249:9-17 [review]., 33. Stillman M, Cata JP. Management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2006;10: 279-87., 44. Cavaletti G, Marmiroli P. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:657-66., 55. Windebank AJ, Grisold W. Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2008;13:27-46 [review].,66. Smith EM, Cohen JA, Pett MA, et al. The validity of neurop-athy and neuropathic pain measures in patients with cancer receiving taxanes and platinums. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38: 133-42.and77. Naleschinski D, Baron R, Miaskowski C. Identification and treat-ment of neuropathic pain in patients with cancer. Pain Clin Updates. 2012;XX.

Currently, the interest in the subjective perceptions of patients about the intensity and the effects of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) increased, and several self-report instruments are being developed to assess the patient's perception of his/her treatment or medical condition.44. Cavaletti G, Marmiroli P. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:657-66., 66. Smith EM, Cohen JA, Pett MA, et al. The validity of neurop-athy and neuropathic pain measures in patients with cancer receiving taxanes and platinums. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38: 133-42., 77. Naleschinski D, Baron R, Miaskowski C. Identification and treat-ment of neuropathic pain in patients with cancer. Pain Clin Updates. 2012;XX., 88. Cavaletti G, Frigeni B, Lanzani F, et al. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity assessment: a critical revision of the currently available tools. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46: 479-94., 99. Ferreira KA, Teixeira MJ, Mendonza TR, et al. Validation of brief pain inventory to Brazilian patients with pain. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:505-11.,1010. Sasane M, Tencer T, French A, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a review. J Support Oncol. 2010;8:E15-21.and1111. Ferreira KASL, William NW Jr, Mendonza TRK, et al. Traduc¸ão para a Língua Portuguesa do M.D. Anderson Symptom Inven-tory - head and neck module (MDASI-H&N). Rev Bras Cir Cabec¸a Pescoc¸o. 2008;37:109-13.

Among the self-report instruments used in clinical practice there is the Pain Quality Assessment Scale (PQAS) (Fig. 1). PQAS is nonspecific for CIPN, but derives from a scale called Neurophatic Pain Scale (NPS). The NPS was developed to assess distinct pain qualities associated with neuropathic pain, the first instrument specifically designed for this purpose.1212. Galer BS, Jensen MP. Development and preliminary validation of a pain measure specific to neuropathic pain: the neuropathic pain scale. Neurology. 1997;48:332-8. The scale includes two items that assess the overall dimensions of intensity and intolerable pain, plus eight items in which specific qualities of neuropathic pain are described as: 'sharp', 'hot', 'poorly localized, 'cold', 'sensitive as raw wound', 'itchy', 'superficial' and 'deep'.1212. Galer BS, Jensen MP. Development and preliminary validation of a pain measure specific to neuropathic pain: the neuropathic pain scale. Neurology. 1997;48:332-8. Later, it was necessary to add 10 descriptors related to the quality of pain ('sensitive as a wound', 'numbness', 'shocks', 'tingling', 'radiating', 'pounding', 'like a toothache', 'sting', 'cramp-like', and 'weight' type) increasing the NPS content validity and three items related to the temporality of pain ('constant with intermittent increases', 'intermittent', or 'constant with fluctuation'), which was useful to evaluate both neuropathic and non-neuropathic pain;11. Jensen MP, Galer BS, Gammaitomi AR, et al. The Pain Quality Assessment Scale (PQAS) and Revised Pain Quality Assessment Scale (PQAS-R): Manual and User Guide; 2010. Mapi Research Trust website (http://www.mapi-trust.org).

http://www.mapi-trust.org...

, 1313. Jensen MP, Gammaitoni AR, Olaleye DO, et al. The pain quality assessment scale: assessment of pain quality in carpal tunnel syndrome. J Pain. 2006;11:823-32., 1414. Victor TW, Jensen MP, Gammaitoni AR, et al. The dimensions of pain quality: factor analysis of the pain quality assessment scale. Clin J Pain. 2008;24:550-5.,1515. Waterman C, Victor TW, Jensen MP, et al. The assessment of pain quality: an item response theory analysis. J Pain. 2010;11:273-9.and1616. Wampler MA, Miaskowski C, Hamel K, et al. The modified total neuropathy score: a clinically feasible and valid measure of taxane-induced peripheral neuropathy in women breast cancer. J Support Oncol. 2006;4:W9-16. thus, originating the PQAS. Although useful, this scale has not been validated for Brazil yet.

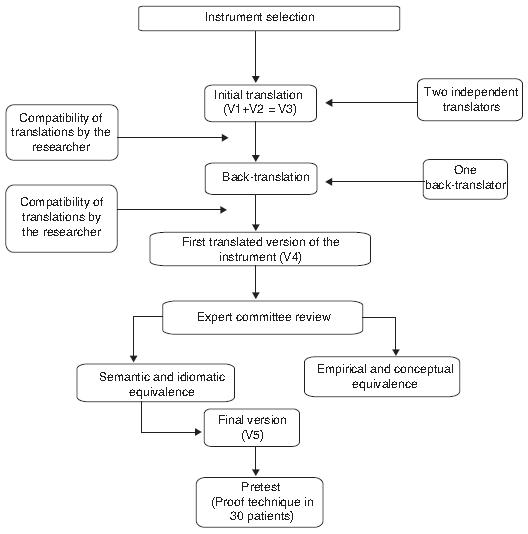

Flowchart showing the steps of translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Pain Quality Assessment Scale (PQAS) at a referral hospital for cancer in Brazil.

Thus, the aim of this study was to translate and cross-culturally adapt the PQAS into Portuguese of Brazil in order to provide clinicians and researchers with a tool for assessing the quality of neuropathic pain in patients undergoing chemotherapy in a cancer referral public hospital.

Materials and methods

PQAS comprises 20 items of global assessment of pain severity and its inconveniences, two spatial aspects of pain, and 16 different qualities of pain. Although the items have similar characteristics with more than one measure, their best ability is to capture the qualities or domains affected by the pain treatment. Each item uses a verbal numerical scale, in which 0 = no pain or no sensation and 10 = the worst pain imaginable. As mentioned above, pain is assessed using two global domains (pain severity and discomfort caused by it), two spatial domains (deep or surface) and 16 quality domains (sharp, hot, poorly localized, cold, sensitive as raw wound, 'mosquito bite', sting, numbness, shock, tingling, cramp, radiating, pounding, 'like a toothache', and weight). Additionally, PQAS also has an item that assesses the temporal pattern of pain (intermittent without pain at other times, minimal pain all the time with exacerbation periods, and constant pain that does not change very much from one moment to another).11. Jensen MP, Galer BS, Gammaitomi AR, et al. The Pain Quality Assessment Scale (PQAS) and Revised Pain Quality Assessment Scale (PQAS-R): Manual and User Guide; 2010. Mapi Research Trust website (http://www.mapi-trust.org).

http://www.mapi-trust.org...

, 1313. Jensen MP, Gammaitoni AR, Olaleye DO, et al. The pain quality assessment scale: assessment of pain quality in carpal tunnel syndrome. J Pain. 2006;11:823-32., 1414. Victor TW, Jensen MP, Gammaitoni AR, et al. The dimensions of pain quality: factor analysis of the pain quality assessment scale. Clin J Pain. 2008;24:550-5.,1515. Waterman C, Victor TW, Jensen MP, et al. The assessment of pain quality: an item response theory analysis. J Pain. 2010;11:273-9.and1616. Wampler MA, Miaskowski C, Hamel K, et al. The modified total neuropathy score: a clinically feasible and valid measure of taxane-induced peripheral neuropathy in women breast cancer. J Support Oncol. 2006;4:W9-16.

PQAS translation and adaptation were performed following the internationally recommended standards.1717. Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, et al. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25:3186-91. PQAS was translated into Portuguese by two Brazilians who are fluent in English and Portuguese, which generated two independent versions (V1 and V2). These two versions were evaluated by the Brazilian researchers who developed a third version (V3). The third version was then subjected to back-translation into English, performed by a physician fluent in Portuguese and English, who was unaware of the original instrument and the translation purpose, which produced an English version (V4).17 17. Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, et al. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25:3186-91.and1818. Fumimoto H, Kobayashi K, Chang C-HE, et al. Cross-cultural vali-dation of an international questionnaire, the general measure of the functional assessment of cancer therapy scale (FACT-G), for Japanese. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:701-9.

The equivalence of each item in the original English version, in the English version resulting from the back-translation (V4), and in the third version in Portuguese (V1 + V2 = V3) were reviewed by an expert committee formed by a multidisciplinary team (physician, nurse, psychologist, physiotherapist), who knew the topic researched, the purpose of the instrument, and the concepts to be analyzed. The experts' work was to detect possible differences in the translations, compare the terms and words together, identifying whether the scale items were related or not to the concepts measured in the original instrument. The descriptors accepted by at least 80% of the experts were considered as having an appropriate translation. From the experts' opinions, the final version of the instrument (V5) was developed.1717. Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, et al. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25:3186-91.and1818. Fumimoto H, Kobayashi K, Chang C-HE, et al. Cross-cultural vali-dation of an international questionnaire, the general measure of the functional assessment of cancer therapy scale (FACT-G), for Japanese. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:701-9.

The decisions made by this committee were based on the equivalence between the source and target version in four aspects:

-

a) Semantic equivalence: knowing if the translated words have the same meaning; if multiple meanings come from a particular item, and if there were grammatical difficulties in translation.

-

b) Idiomatic equivalence: equivalent expressions were formulated in the target version, avoiding difficulties in translating colloquialisms and idioms.

-

c) Empirical Equivalence: terms in the questionnaire were replaced by similar terms which are used in our culture of origin, seeking to capture daily life experiences.

-

d) Conceptual equivalence: it was observed if the words had different meanings across cultures, replacing the inadequate terms. 17, 18 and 19

Consensus was reached on all items, with the presence of all translators on the committee, providing a good understanding immediately.1717. Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, et al. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25:3186-91.and1818. Fumimoto H, Kobayashi K, Chang C-HE, et al. Cross-cultural vali-dation of an international questionnaire, the general measure of the functional assessment of cancer therapy scale (FACT-G), for Japanese. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:701-9.

After choosing the final version (V5), the pre-test was conducted with 30 patients undergoing chemotherapy at a referral hospital for oncology in Brazil after signing the informed consent. They completed the questionnaire, were asked what they thought of each item, and choose the best answer.1717. Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, et al. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25:3186-91.and1818. Fumimoto H, Kobayashi K, Chang C-HE, et al. Cross-cultural vali-dation of an international questionnaire, the general measure of the functional assessment of cancer therapy scale (FACT-G), for Japanese. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:701-9.

Semantic equivalence was performed under the coordination of the MAPI Research Trust, Lyon, France, researchers who drafted the original PQAS with the main investigator participation.

Results

The final Brazilian version of the PQAS resulted from the back-translation and experts' review and is being submitted to an evaluation of its psychometric properties in an ongoing study by the pain team of the University Hospital, a referral center in Brazil.

During the preparation of the V1 and V2 versions, we observed 100% semantic agreement among translators. In item 4, in which we asked how dull your pain feels?-the word "dull" was translated as "indefinida" (undefined) on these two versions, which did not persist after the experts review.

In back-translation, we saw differences in language translation with the original version. In item 1, the word 'intense' in the original was back-translated as 'severe'. In item 2, 'like a spike' was replaced by 'like a needle' and 'the most sharp' by 'the most prickling'. All other items are summarized in Table 1.

During the expert committee evaluation, there were no differences in semantic and conceptual equivalence. As previously mentioned, the word 'dull' in item 4 was translated as 'undefined' in versions 1 and 2. However, such expression was judged as having little information about the patient's painful feature in our native language, which was identified as a gap in empirical equivalence. Thus, it was replaced by the term 'poorly localized', best exemplifying this quality of pain in our regional population.

The experts also identified colloquialisms and idioms that could interfere with the correct description of the quality of pain in our population, such as in item 1 with 'nenhuma dor' (no pain at all) in V1 and 'sem dor' (no pain) in V2, the term 'sem dor' (no pain) was chosen for the final version. This fact results in a change in idiomatic equivalence. After completion of this phase, version 5 of the instrument was generated. Table 2 and Table 3 show the other terms.

During the pre-test, in which patients are asked to choose between the terms, only in item 12 two people did not choose because they did not understand the scale sense. In other terms, 100% of patients reported understanding the items chosen without any difficulty.

Despite this small difference, the originators of the scale decided that there was semantic concordance between the two translations, and that the validation process could be started.

Discussion

The main objective of this study was achieved with the successful translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the PQAS into Portuguese.

Among the various adverse events resulting from chemotherapy, CIPN remains the diagnosis in later stages of the disease with moderate to severe symptoms of sensory and/or motor neuropathy, when the quality of life of these individuals is already compromised both physically and emotionally. Thus, we chose to validate the PQAS in this population of patients who often report tingling, stinging or burning, numbness, pinpricks and bilateral shock-like sensations in hands and feet as symptoms resulting from CIPN in early stages of the disease. Furthermore, the absence of a gold standard instrument to identify this disease further hinders any possibility of prevention and appropriate treatment.1010. Sasane M, Tencer T, French A, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a review. J Support Oncol. 2010;8:E15-21.

Other studies, which compared the effects of different pain treatments for patients with similar qualities of pain, reported effects both similar and different for certain qualities, depending on the studied population and treatment.11. Jensen MP, Galer BS, Gammaitomi AR, et al. The Pain Quality Assessment Scale (PQAS) and Revised Pain Quality Assessment Scale (PQAS-R): Manual and User Guide; 2010. Mapi Research Trust website (http://www.mapi-trust.org).

http://www.mapi-trust.org...

One study compared the effects of 5% lidocaine patch with corticoid injection alone in carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS). The results showed a decrease in tingling, numbness, unpleasant sensation, deep ache, electric-like, intense, superficial, sharp, burning, and unpleasant sensations in both treatments, with greater effects on pounding and numbness with the lidocaine patch99. Ferreira KA, Teixeira MJ, Mendonza TR, et al. Validation of brief pain inventory to Brazilian patients with pain. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:505-11.. In the group of neuropathic pain patients with postherpetic neuralgia and diabetic neuropathy, a combination of oxycodone and pregabalin showed significant improvement in freezing cold pain, although the combination of pregabalin and placebo had improved burning and sharp pain.11. Jensen MP, Galer BS, Gammaitomi AR, et al. The Pain Quality Assessment Scale (PQAS) and Revised Pain Quality Assessment Scale (PQAS-R): Manual and User Guide; 2010. Mapi Research Trust website (http://www.mapi-trust.org).

http://www.mapi-trust.org...

The results of these studies suggest the efficacy of various pharmacological treatments for certain qualities of pain in patients with specific diagnoses. Thus, the translation and cross-cultural adaptation of PQAs and its subsequent validation will provide a useful tool for this purpose in our population.

The development of the V1 and V2 versions was not difficult. However, the physician who performed the back-translation reported difficulty to finish it, as he represents a different specialty from the researched topic, in addition to the fact that many terms that refer to painful conditions are not easy to express exactly the quality of the pain the patient feels. This generated more reliability to this stage of the research, as the back-translated version was deemed compatible by the originators of the scale.

The pretest phase is necessary for the completion of the translation and cultural adaptation process of the scales. During the study, it was necessary to give more extensive explanations of some terms due to the low educational level of the population surveyed. In a study conducted in Japan,1818. Fumimoto H, Kobayashi K, Chang C-HE, et al. Cross-cultural vali-dation of an international questionnaire, the general measure of the functional assessment of cancer therapy scale (FACT-G), for Japanese. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:701-9. patients reported problems regarding the understanding of items, some being considered irrelevant, diverging from this study where such action was not necessary. There was no problem with the scale creators' authorization to start the process of its translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and validation.

During data collection, the questionnaire was completed through an interview via clinician/researcher and patient using only pencil and paper. Patients took about 15 minutes on average to answer the questionnaire for the first time. At other times, this time was longer. After realizing that this could be a complicating factor for the questionnaire application in the routine of crowded offices, a small training among researchers was conducted. Thus, the interview was conducted with more simple and easy to understand terms, as most patients had a more elementary level of education. It was then possible to reduce the interview time to 8-10 minutes without compromising the visit time and achieving patient satisfaction. However, it is known that patients have difficulty expressing painful symptoms, especially when they are associated with CIPN.1010. Sasane M, Tencer T, French A, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a review. J Support Oncol. 2010;8:E15-21. This may explain the difficulty faced by patients to complete the questionnaire.

Although there is no gold standard process to be strictly followed by all researchers in order to perform a translation and cross-cultural adaptation, three steps are essential: translation/back-translation, expert committee review, and pretest. All three steps in this study were rigorously monitored.1818. Fumimoto H, Kobayashi K, Chang C-HE, et al. Cross-cultural vali-dation of an international questionnaire, the general measure of the functional assessment of cancer therapy scale (FACT-G), for Japanese. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:701-9.

Thus, the Brazilian version of PQAS is now translated and culturally adapted and, after its validation (currently in progress by the Pain Research Group at the University Hospital, a referral center in Brazil), it will certainly be a useful tool for clinicians and researchers to evaluate the signs and symptoms of different qualities of pain, neuropathic or not, helping to elucidate the painful mechanism, evaluate the effectiveness of treatment of different diseases, and especially in the early detection of sensory symptoms in patients at risk of developing more serious stages of CIPN.

References

-

1Jensen MP, Galer BS, Gammaitomi AR, et al. The Pain Quality Assessment Scale (PQAS) and Revised Pain Quality Assessment Scale (PQAS-R): Manual and User Guide; 2010. Mapi Research Trust website (http://www.mapi-trust.org).

» http://www.mapi-trust.org -

2Quasthoff S, Hartung HP. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. J Neurol. 2002;249:9-17 [review].

-

3Stillman M, Cata JP. Management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2006;10: 279-87.

-

4Cavaletti G, Marmiroli P. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:657-66.

-

5Windebank AJ, Grisold W. Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2008;13:27-46 [review].

-

6Smith EM, Cohen JA, Pett MA, et al. The validity of neurop-athy and neuropathic pain measures in patients with cancer receiving taxanes and platinums. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38: 133-42.

-

7Naleschinski D, Baron R, Miaskowski C. Identification and treat-ment of neuropathic pain in patients with cancer. Pain Clin Updates. 2012;XX.

-

8Cavaletti G, Frigeni B, Lanzani F, et al. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity assessment: a critical revision of the currently available tools. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46: 479-94.

-

9Ferreira KA, Teixeira MJ, Mendonza TR, et al. Validation of brief pain inventory to Brazilian patients with pain. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:505-11.

-

10Sasane M, Tencer T, French A, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a review. J Support Oncol. 2010;8:E15-21.

-

11Ferreira KASL, William NW Jr, Mendonza TRK, et al. Traduc¸ão para a Língua Portuguesa do M.D. Anderson Symptom Inven-tory - head and neck module (MDASI-H&N). Rev Bras Cir Cabec¸a Pescoc¸o. 2008;37:109-13.

-

12Galer BS, Jensen MP. Development and preliminary validation of a pain measure specific to neuropathic pain: the neuropathic pain scale. Neurology. 1997;48:332-8.

-

13Jensen MP, Gammaitoni AR, Olaleye DO, et al. The pain quality assessment scale: assessment of pain quality in carpal tunnel syndrome. J Pain. 2006;11:823-32.

-

14Victor TW, Jensen MP, Gammaitoni AR, et al. The dimensions of pain quality: factor analysis of the pain quality assessment scale. Clin J Pain. 2008;24:550-5.

-

15Waterman C, Victor TW, Jensen MP, et al. The assessment of pain quality: an item response theory analysis. J Pain. 2010;11:273-9.

-

16Wampler MA, Miaskowski C, Hamel K, et al. The modified total neuropathy score: a clinically feasible and valid measure of taxane-induced peripheral neuropathy in women breast cancer. J Support Oncol. 2006;4:W9-16.

-

17Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, et al. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25:3186-91.

-

18Fumimoto H, Kobayashi K, Chang C-HE, et al. Cross-cultural vali-dation of an international questionnaire, the general measure of the functional assessment of cancer therapy scale (FACT-G), for Japanese. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:701-9.

-

19Aaronson N, Alonso J, Burnam A, et al. Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: attributes and review criteria. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:193-205.

-

☆

Institution: Instituto Maranhense de Oncologia Aldenora Bello.

Annex. Portuguese final version of the PainQuality Assessment Scale (PQAS)

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

Jan-Feb 2016

History

-

Received

09 Aug 2013 -

Accepted

30 Oct 2013