Abstracts

OBJECTIVES: Familial caregivers of demented patients suffer from high levels of burden of care, but the literature is sparse regarding the prevalence and predictors of burnout in this group. Burnout is composed of three dimensions: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP) and reduced personal accomplishment (RPA). We aimed to investigate the associations between burnout dimensions and the caregivers' and patients' sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. METHODS: This study is cross-sectional in design. Caregivers (N = 145) answered the Maslach Burnout Inventory, Beck Depression Inventory, Beck Anxiety Inventory and a Sociodemographic Questionnaire. Patients (N = 145) were assessed with the Mini Mental State Examination, Functional Activities Questionnaire, Neuropsychiatric Inventory, and Clinical Dementia Rating Scale. RESULTS: High levels of EE were present in 42.1% of our sample, and DP was found in 22.8%. RPA was present in 38.6% of the caregivers. The caregivers' depression and the patients' delusions remained the significant predictors of EE. CONCLUSIONS: The presence of caregiver depression and patient delusions should always be part of the multidisciplinary evaluation of dementia cases.

Caregiver; Burden of Care; Burnout; Depression; Dementia

OBJETIVOS: Os cuidadores familiares de pacientes com demência sofrem de altos níveis de sobrecarga de cuidados, mas a literatura referente a prevalência e os fatores preditores de burnout neste grupo é escassa. O burnout é composto por três dimensões: exaustão emocional (EE), despersonalização (DP) e reduzida realização pessoal (RRP). Nós temos como objetivo investigar as associações existentes entre as dimensões do burnout e as características clínicas e sóciodemográficas dos cuidadores e dos pacientes com demência. MÉTODOS: O estudo possui um delineamento transversal. Os cuidadores (N = 145) responderam ao Inventário de Burnout de Maslach, Inventário de Depressão de Beck, Inventário de Ansiedade de Beck, e um Questionário Sócio-Demográfico. Os pacientes (N = 145) foram avaliados através do Mini Exame do Estado Mental, Questionário de Atividades Funcionais, Inventário Neuropsiquiátrico e a Escala de Estadiamento Clínico das Demências. RESULTADOS: Altos níveis de EE foram encontrados em 42,1%, e de DP em 22,8% da amostra. RRP esteve presente em 38,6% dos cuidadores. A depressão dos cuidadores, e os delírios dos pacientes foram os principais fatores preditores de EE. CONCLUSÕES: A presença de depressão nos cuidadores, e de delírios nos pacientes devem sempre fazer parte da avaliação multidisciplinar da demência.

Cuidador; Sobrecarga de cuidados; Burnout; Depressão; Demência

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Burnout in familial caregivers of patients with dementia

Burnout em cuidadores familiares de pacientes com demência

Annibal TruzziI,II; Letice ValenteI; Ingun UlsteinII; Eliasz EngelhardtI; Jerson LaksI; Knut EngedalII

ICenter for Alzheimer's Disease, Institute of Psychiatry, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

IICenter for Ageing and Health, Department of Geriatric Medicine, Oslo University Hospital, Norway

Corresponding author Corresponding author: Annibal Truzzi Center for Alzheimer's Disease, Institute of Psychiatry, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Av. Venceslau Brás, 71 Fundos Rio de Janeiro - RJ - Brasil CEP: 22290-140. Phone: (+55 21) 3873-5540, 3873-5507. Fax: (+55 21) 2543-3101 E mail: atruzzi@hotmail.com

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVES: Familial caregivers of demented patients suffer from high levels of burden of care, but the literature is sparse regarding the prevalence and predictors of burnout in this group. Burnout is composed of three dimensions: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP) and reduced personal accomplishment (RPA). We aimed to investigate the associations between burnout dimensions and the caregivers' and patients' sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

METHODS: This study is cross-sectional in design. Caregivers (N = 145) answered the Maslach Burnout Inventory, Beck Depression Inventory, Beck Anxiety Inventory and a Sociodemographic Questionnaire. Patients (N = 145) were assessed with the Mini Mental State Examination, Functional Activities Questionnaire, Neuropsychiatric Inventory, and Clinical Dementia Rating Scale.

RESULTS: High levels of EE were present in 42.1% of our sample, and DP was found in 22.8%. RPA was present in 38.6% of the caregivers. The caregivers' depression and the patients' delusions remained the significant predictors of EE.

CONCLUSIONS: The presence of caregiver depression and patient delusions should always be part of the multidisciplinary evaluation of dementia cases.

Descriptors: Caregiver; Burden of Care; Burnout; Depression; Dementia.

RESUMO

OBJETIVOS: Os cuidadores familiares de pacientes com demência sofrem de altos níveis de sobrecarga de cuidados, mas a literatura referente a prevalência e os fatores preditores de burnout neste grupo é escassa. O burnout é composto por três dimensões: exaustão emocional (EE), despersonalização (DP) e reduzida realização pessoal (RRP). Nós temos como objetivo investigar as associações existentes entre as dimensões do burnout e as características clínicas e sóciodemográficas dos cuidadores e dos pacientes com demência.

MÉTODOS: O estudo possui um delineamento transversal. Os cuidadores (N = 145) responderam ao Inventário de Burnout de Maslach, Inventário de Depressão de Beck, Inventário de Ansiedade de Beck, e um Questionário Sócio-Demográfico. Os pacientes (N = 145) foram avaliados através do Mini Exame do Estado Mental, Questionário de Atividades Funcionais, Inventário Neuropsiquiátrico e a Escala de Estadiamento Clínico das Demências.

RESULTADOS: Altos níveis de EE foram encontrados em 42,1%, e de DP em 22,8% da amostra. RRP esteve presente em 38,6% dos cuidadores. A depressão dos cuidadores, e os delírios dos pacientes foram os principais fatores preditores de EE.

CONCLUSÕES: A presença de depressão nos cuidadores, e de delírios nos pacientes devem sempre fazer parte da avaliação multidisciplinar da demência.

Descritores: Cuidador; Sobrecarga de cuidados; Burnout; Depressão; Demência.

Introduction

The burden of care for the families of patients with dementia is now considered a major healthcare issue, due to the increasing number of persons with dementia worldwide and also because much of the caregiving responsibility falls upon family members.1 More than half of the familial caregivers of patients with dementia report that they suffer from some kind of burden, which is frequently associated with depression, anxiety, higher physical morbidity and mortality in this group.2,3

The burden of care is a heterogeneous concept, and a distinction between the objective burden, which refers to the economic impact and the time spent in care, and the subjective burden, or the caregiver's emotional responses, has been proposed to describe the burden of care more effectively.4 A Brazilian study found that close kinship between patient and caregiver, the duration of the caregiver role and the patient's neuropsychiatric symptoms were the main predictors of the burden of care in a sample of 49 familial caregivers of patients with dementia.5

The chronic stress associated with the burden of caring for someone with dementia makes caregivers prone to burnout. Familial caregivers usually do not share their responsibilities with other family members, which may contribute to emotional exhaustion.2 Strenuous caregiving tasks may be more manageable when they are implemented in a detached and impersonal manner.6 The absence of positive feedback both from the patient and society contribute to caregivers' low sense of self-accomplishment.7

The concept of burnout includes not only the pure stress dimension associated with the burden of care but also the critical aspects of the relationship people establish with their occupation. Although early burnout studies did involve workers in services related to social and healthcare occupations, there are few studies of burnout in familial caregivers of patients with dementia.

Burnout is usually observed as a psychosocial syndrome that appears in response to chronic and interpersonal stressors in the work environment. Burnout is composed of three dimensions: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP) or cynicism and reduced personal accomplishment (RPA). EE refers to a lack of energy and enthusiasm and the draining of one's emotional resources. Depersonalization refers to the development of an indifferent, impersonal or cynical attitude between oneself and the service recipient. RPA is a tendency to perceive one's work negatively or as ineffective.6

There is now a growing body of data supporting the view that familial caregivers of patients with dementia may also suffer from burnout.8-10 According to the literature, limitations in one's social life, poor health indicators and the lack of a positive outlook in caregiving are reported to be strong predictors of burnout in familial caregivers of patients with dementia.7,8,10,11 Recently, a study conducted by Takai et al.12 found that caregiver burnout and depression were the most significant factors associated with the caregiver's low quality of life.12

The associations between the three burnout dimensions and the caregiver's clinical and sociodemographic characteristics are less studied. A study conducted by Ylmaz et al.11 found that the severity of the caregiver's anxiety and the patient's functional decline were the main predictors of EE. Additionally, a submissive approach by the caregiver, their level of education and caring for a female patient were related to RPA. Finally, this study found a significant association between the patient's depression and the caregiver's DP.11 We have not found any studies from Latin America that were aimed at investigating burnout's three dimensions among familial caregivers of patients with dementia.

Based on the findings from the literature, we hypothesized that caregivers who report any physical or emotional morbidity, particularly anxiety and depression, and those who take care of more functionally impaired patients may present with higher EE. Moreover, caregivers who take care of patients with severe neuropsychiatric symptoms may report higher EE and DP. Finally, caregivers of female patients will present with a lower sense of personal accomplishment.

We investigated the relationships among the three dimensions of burnout and both the caregivers' and the patients' sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

Methods

Sample

The data came from a convenient sample of 145 caregiver and dementia outpatient dyads, which were consecutively included in a cross-sectional study. All evaluations were carried out by a geriatric psychiatrist and a neuropsychologist.

All patients were being treated at the Center for Alzheimer's Disease of the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro between 2005 and 2010.

Caregivers had to be older than 18 years old and have at least weekly face-to-face contact with the patient. Only familial caregivers were eligible to participate in the study. Otherwise no inclusion or exclusion criteria were applied.

Patients were men and women with a mean age of 76.4 (SD = 6.9) years and a diagnosis of either possible or probable Alzheimer's disease (AD) according to the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke - Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association, Vascular Dementia (VaD) according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and Association Internationale pour la Recherche et l'Enseignement en Neuroscience, and Mixed Dementia according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - Fourth Edition.13-15 Of the 145 patients, 89 had AD, 25 had VaD, and 31 had a mixed diagnosis.

Measurements

Caregivers

Burnout was measured with the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), a 22-item self-rating scale concerning the 3 dimensions of burnout: EE (9 items), DP (5 items) and RPA (8 items). The frequency of each item was scored from 0 (never) to 6 (every day), which gives a maximum score on EE of 54, on DP of 30, and on RPA of 40.16 The Brazilian Portuguese version of the MBI used in this study, as well as the cutoff scores, were adapted from a previous study performed in Brazil.17 A study conducted by Carlotto et al.18 that aimed to analyze the psychometric characteristics of the MBI found that the three factors explained 55.7% of the total variation of the sample's answers. Furthermore, the authors found that the three factors of the MBI had an internal consistency that was considered moderate to high.18

A brief self-administered sociodemographic questionnaire was developed by the authors to collect general sociodemographic data, such as age, gender, marital status, family relationship, education history and time as caregiver, and subjective health status data. Caregivers were asked to respond yes or no to the questions inquiring as to whether they suffered from six common emotional symptoms (sadness, anxiety, insomnia, irritability, fatigue, wish to die) and their history of psychiatric treatment and use of psychotropic drugs.

We further assessed the caregivers' mental health with the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), which is a self-administered instrument with 21 items that cover the most frequent anxiety symptoms observed in clinical practice. Each item was scored 0, 1, 2 or 3, with higher scores denoting an increasing severity of symptoms. The Brazilian Portuguese validated version of the BAI was administered.19

Lastly, we also asked the caregivers to fill in the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), a 21-item self-rating scale that covers a variety of depressive symptoms, including feelings of sadness, concerns about the future, suicidal ideation, tearfulness, sleep, fatigue, loss of interest, worries about health, sexual interest, appetite, weight loss and general enjoyment. Each item was rated 0, 1, 2 and 3, with higher scores denoting an increasing severity of symptoms. The Brazilian version of the BDI was employed.20

Patients

Patient age and gender were recorded, and measurements of their mental and functional abilities were conducted.

The Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) was used to assess global mental function. The MMSE is a 30-item scale that evaluates five cognitive domains with a maximum score of 30 points, including orientation to time and place (10 points), registration of three words (3 points), attention and calculation (5 points), recall of three words (3 points) and language (8 points). The MMSE version used in the study was translated and validated for Brazilian Portuguese.21

The severity of dementia was assessed by the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR), which ranges from 0 for healthy people, 0.5 for questionable dementia and 1, 2 and 3 for mild, moderate and severe dementia, respectively, as defined in the scale. Six domains are rated, and the total rating can also be applied, generating an aggregate score of each individual area. In this case, the maximum and most severe score was.18 We employed the validated Brazilian Portuguese version of the CDR.22

The ability to function in daily living was assessed by the Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ). The FAQ is a 10-item scale that assesses instrumental and basic functional capacities in older people, each of which is rated on a four-point scale (0 being normal and 3 incapable), with a maximum score being 30 points (severely disabled).23 The FAQ has been recommended as a useful instrument to assess functional abilities in the elderly Brazilian population.24

Finally, we applied the Neuropsychiatric Inventory-10 items version (NPI-10) to measure neuropsychiatric symptoms often observed in patients with dementia. The NPI assesses 10 behavioral disturbances: delusions, hallucinations, dysphoria, anxiety, agitation/aggression, euphoria, disinhibition, irritability/lability, apathy and aberrant motor behavior. Severity and frequency are independently assessed in this instrument, and the total score is given as the frequency x severity with a maximum score of 120 that indicates the worst score. We employed the Brazilian Portuguese version of the NPI.25

Ethical issues

A full description of the study was given to the patients and their caregivers. Explicit consent was required for enrollment, and caregivers were asked to sign the informed consent form stating that they would agree to provide their own information, as well as the patient's clinical and sociodemographic information. This procedure was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro.

Statistical analysis

All variables were inspected for normality before analysis. Depending on the distribution, Student's t-test and the Mann-Whitney U test were performed as initial comparisons of both the patient's and the caregiver's sociodemographic and clinical characteristics according to burnout dimensions. For this purpose, continuously distributed explanatory variables, such as age, BDI, BAI, FAQ, MMSE and NPI scores, were dichotomized by their median score.

Spearman's rank correlation was used to assess the relationships between the continuous variables, such as the burnout dimensions and the caregiver's and patient's clinical variables. We also wanted to investigate multicollinearity between the continuous variables.

We planned to carry out six multiple linear regression analyses with backward stepping using the three dimensions of burnout as dependent variables. The caregiver's characteristics that were of significance in the binary analyses were used as explanatory variables in addition to age and gender in three of the analyses, whereas patient characteristics that were significantly related to burnout were used as explanatory variables in the last three models. Data were analyzed using SPSS statistical package 16.0.

Results

Characteristics of the caregiver-patient dyads are shown in Table 1. The majority of the caregivers were middle-aged married daughters of the patients. The mean time as a caregiver was 3.8 (SD = 2.7) years. Approximately 23% (N = 33) of the caregivers reported using any psychotropic drug and the most commonly used drug class was benzodiazepines (48.8%) followed by antidepressants (32.6%), herbal supplements (14%) and mood stabilizers (4.6%). More than half of the caregivers reported recently suffering from some emotional morbidity in the brief self-administered sociodemographic questionnaire; anxiety was the most reported emotional symptom (55%). Using the recommended cutoff point of 26 or more for the presence of high EE on the MBI, EE was reported to be present in 42.1% of the caregivers. When using the cutoff point of 9 or more for high DP, this dimension of burnout was present in 22.8% of the caregivers. Reduced personal accomplishment was present in 38.6% of the sample using the recommended cutoff point of 33 or less for this dimension.

In the 145 caregivers, 33.8% did not experience any clinically significant burnout dimension. Burnout, defined as high levels of EE, DP, and low RPA, was present in 6.9% of our sample. High EE and low RPA were found in 19.3%, high EE and DP in 13.1%, and high DP and low RPA in 11.7% of the caregivers.

Most of the patients were females (64%) with mild or severe dementia according to the CDR. Using the NPI-10, we found that the most common neuropsychiatric symp- toms were apathy (74%), agitation (43%), aberrant motor behavior (43%), depression (38%), anxiety (36%) and irritability (32%).

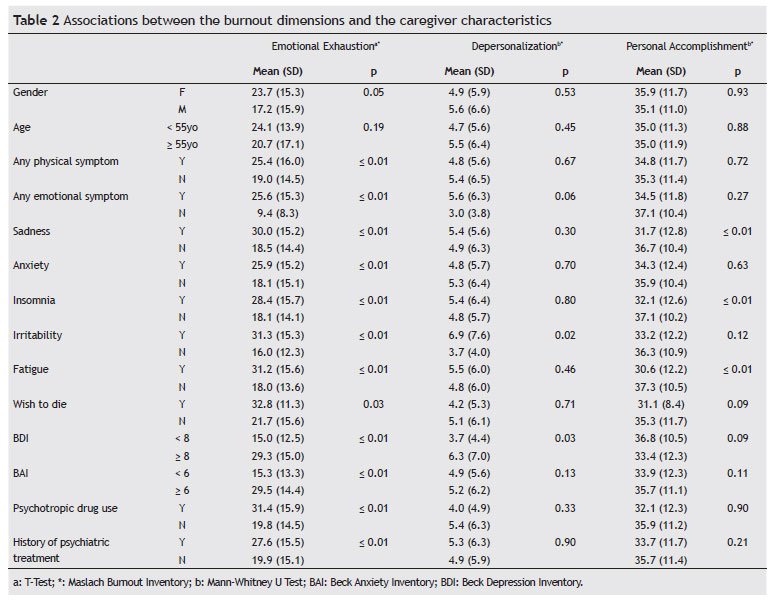

The associations between the three burnout dimensions and the caregiver's characteristics are summarized in Table 2. Several significant associations were found between EE and the caregivers' characteristics. Female caregivers were more emotionally exhausted than male caregivers (p < 0.05). Caregivers who reported any physical symptoms in addition to emotional symptoms, including sadness, anxiety, insomnia, irritability, and fatigue, presented higher EE scores than those who did not report physical symptoms (p < 0.01). Those who reported a "wish to die" also presented with higher EE scores (p < 0.05). There was a statistically significant association between higher BDI and BAI scores with higher EE scores in caregivers (p < 0.01).

The only significant associations between DP and the caregiver characteristics were irritability and a higher BDI score (p < 0.05), whereas those who reported suffering from sadness, insomnia and fatigue had lower personal accomplishment scores (p < 0.01).

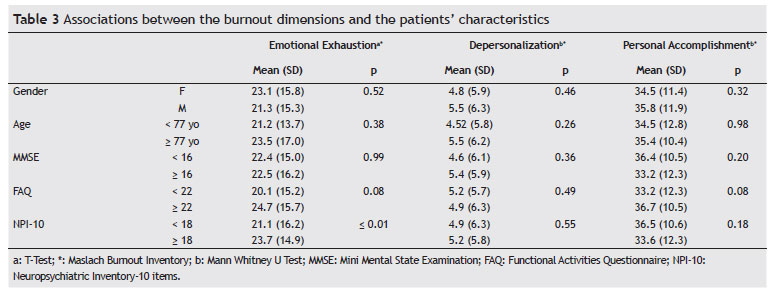

The associations between burnout dimensions and the patient characteristics are summarized in Table 3. Only the total NPI score was associated with higher levels of EE (p < 0.01).

Before carrying out the regression analyses, we conducted two correlation analyses, one between the three dimensions of burnout and one between the possible explanatory variables of burnout. The highest correlation between the three dimensions of burnout was between EE and DP (Spearman rho 0.33), indicating that the three dimensions are independent of each other. In the correlation analyses of the caregiver characteristics, we found that the BDI score was strongly correlated to BAI (Spearman rho 0.69), indicating that these two variables are not independent of each other. Therefore, we decided to exclude the BAI from the linear regression analyses. Otherwise, no variables showed a higher correlation than 0.5.

According to the results in Tables 2 and 3, the three burnout dimensions were associated with more than one explanatory variable. Therefore, we carried out three linear regression analyses with the patient and the caregiver characteristics as explanatory variables. Only one model showed significant associations. Using EE as the dependent variable and the caregivers' characteristics, as well as the patients' NPI-10 subitems, as explanatory variables, six variables remained in this linear regression analysis with an explained variance of 44% (Table 4). The NPI delusion subitem (β = 0.17, p < 0.05) and the BDI (β = 0.53; p < 0.01) were both significantly associated with the caregivers' EE.

Discussion

This study showed that the caregiver's depression is strongly associated with EE in familial caregivers of patients with dementia. We also found that among the patient characteristics, delusions were the strongest predictor of caregiver EE.

Most of the caregivers in our sample were daughters of the patients, and the next most frequent group included spouses. This finding is consistent with previous studies conducted in Brazil, which found that daughters were the primary caregivers of patients with dementia.5,26 Female caregivers reported higher EE scores compared to male caregivers. According to the literature, women tend to score higher on EE, whereas men often score higher on DP.6 This difference is probably due to gender role stereotypes, as men appear less likely to express their negative feelings than female caregivers.7

Emotional exhaustion was the most reported burnout dimension in our sample. Matsuda (2001) also found higher levels of EE in his sample of 67 familial caregivers of patients with dementia.27 EE is the main burnout dimension and reflects the stress dimension of this syndrome. The strenuous physical and emotional demands that dementia caregivers face due to the caregiving tasks appear to drain their emotional resources and may ultimately lead to feelings of energy depletion.6

In our study, we found that caregivers who reported any physical or emotional symptoms presented higher levels of EE. This group often presents with high physical and emotional morbidity due to chronic stress, and nearly half of them suffer from significant emotional distress that may require mental health treatment.3,10,28

Neuropsychiatric symptoms are one of the main patient factors contributing to caregiver stress.1 Likewise, we found that caregivers of patients with more severe behavioral symptoms according to the NPI-10 scored higher on EE evaluations. The study conducted by Moscoso et al.31 found a significant association between the burden of care and the NPI score in a sample of 31 caregivers and patients with AD.31 Particularly, we found that delusions were a significant predictor of caregiver EE. Matsumoto et al. (2007) also found a significant correlation between delusions and caregiver distress. According to these authors, each neuropsychiatric symptom imposes a different impact on the caregiver burden, which does not depend on its frequency and severity.29

Our results showed that caregivers who reported irritability and more severe depressive symptoms according to the BDI had higher DP scores. Although the associations between the BDI and DP were not significant in the linear regression model, it may be that the adoption of an indifferent attitude towards the patients might help those caregivers who are depressive to make their demands more manageable.

The lack of resources and positive feedback from the care recipient are associated with caregiver RPA.6,7 In our study, caregivers who reported irritability, sadness, fatigue and insomnia had a lower sense of personal accomplishment. It seems plausible that such symptoms may interfere with the caregiver's sense of effectiveness. It may be difficult for caregivers to feel personally accomplished when feeling sad, fatigued and having difficulties sleeping. More studies focusing on the predictive value of these symptoms on caregiver RPA using a standard instrument are needed.

Burnout, and particularly EE, has been observed as related to depression in the caregivers of demented patients.9-11 In our study, depression was a strong predictor of EE. Although there is an overlap of symptoms between EE and depression, such as fatigue, irritability and diminished enthusiasm, the discriminant validity between the two syndromes has been established in several studies. According to the literature, burnout is an occupationally related condition, whereas depression is a more pervasive and context-free syndrome.6,30

Several limitations of our study which merit consideration include the fact that our sample derived from a psychogeriatric reference center with a multidisciplinary staff where patients are believed to suffer more mental health morbidity, which does not allow us to generalize our conclusions. Furthermore, male caregivers were underrepresented in our study, and the absence of a control group in our sample prevents further comparisons. The clinical data collected from the brief self-administered sociodemographic questionnaire, which is not a validated structured instrument, also constitute a limitation of the study. Finally, the cross-sectional design of our study does not allow us to make any causal inferences regarding the identified associations.

Conclusions

The caregivers' depression and the patients' delusions are highly associated with EE in familial caregivers of patients with dementia. We believe that our findings highlight the importance of addressing not only the patients' neuropsychiatric symptoms but also the caregivers' depression because they are an important source of the caregivers' emotional exhaustion. We believe that the early identification of caregivers who are more prone to develop burnout is necessary to improve their engagement in dementia care and, consequently, both the caregivers' and patients' quality of life.

Acknowledgments

This study received financial support from the Research Council of Norway.

Received on October 28, 2011; accepted on February 2, 2012

- 1. Etters L, Goodall D, Harrison BE. Caregiver burden among dementia patient caregivers: A review of the literature. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008;20:423-8.

- 2. Schulz R, Martire LM. Family caregiving of persons with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12:240-9.

- 3. Ulstein I, Wyller T, Engedal K. High scores on the Relative Stress Scale, a marker of possible psychiatric disorder in family carers of patients with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(3):195-202.

- 4. Farcnik K, Persyko MS. Assessment, measures and approaches to easing caregiver burden in Alzheimer's disease. Drugs Aging. 2002;19:203-15.

- 5. Garrido R, Menezes PR. Impact on caregivers of elderly patients with dementia treated at a psychogeriatric service. Rev Saude Publica. 2004;28(6):835-41.

- 6. Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397-422.

- 7. Hubbell L, Hubbell K. The burnout risk for male caregivers in providing care to spouses afflicted with Alzheimer's disease. J Health Hum Serv Adm. 2002;25:115-32.

- 8. Almberg B, Grafstrom M, Winblad B. Caring for a demented elderly person - burden and burnout among caregiving relatives. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25:109-16.

- 9. Truzzi A, Souza W, Bucasio E, Berger W, Figueira I, Engelhardt E, Laks J. Burnout in a sample of Alzheimer's disease caregivers in Brazil. Eur J Psychiat. 2008;22:151-60B.

- 10. Takai M, Takahashi M, Iwamitsu Y, Ando N, Okazaki S, Nakajima K, Oishi S, Miyaoka H. The experience of burnout among home caregivers of patients with dementia: relations to depression and quality of life. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;49:e1-5.

- 11. Yilmaz A, Turan E, Gundogar D. Predictors of burnout in the family caregivers of Alzheimer's disease: Evidence from Turkey. Australas J Ageing. 2009;28:16-21.

- 12. Takai M, Takahashi M, Iwamitsu Y, Oishi S, Miyaoka H. Subjective experiences of family caregivers of patients with dementia as predictive factors of quality of life. Psychogeriatrics. 2011;11:98-104.

- 13. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of department of health and human services task force on Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939-44.

- 14. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Press; 1994.

- 15. Roman GC, Tatemichi TK, Erkinjuntti T, Cummings JL, Masdeu JC, Garcia JH, Amaducci L, Orgogozo JM, Brun A, Hofman A et al. Vascular dementia: diagnostic criteria for research studies. Report of the NINDS-AIREN International Workshop. Neurology. 1993;43(2):250-60.

- 16. Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologist Press; 1996.

- 17. Benevides-Pereira AMT. Burnout: O processo de adoecer pelo trabalho. In: Benevides-Pereira AMT, editor. Burnout: Quando o trabalho ameaça o bem estar do trabalhador. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo; 2002, pp. 21-91.

- 18. Carlotto MS, Camara SG. Propriedades psicométricas do Maslach Burnout Inventory em uma amostra multifuncional. Estud psicol. 2007;24(3):325-32.

- 19. Cunha JA. Manual das versões em português das escalas Beck. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo; 2001.

- 20. Gorestein C, Andrade L. Validation of a Portuguese version of the Beck Depression Inventory and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory in Brazilian subjects. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1996;29:453-57.

- 21. Bertolucci PHF, Brucki SMD, Campacci SR, Juliano Y. O mini exame do estado geral em uma população geral - impacto da escolaridade. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 1994;52:1-7.

- 22. Maia ALG, Godinho C, Ferreira ED, Almeida V, Schuh A, Kaye J, Chaves MLF. Aplicação da versão brasileira da escala de avaliação clínica da demência (Clinical Dementia Rating - CDR) em amostras de pacientes com demência. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2006;64:485-9.

- 23. Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH, Chance JM, Filis S. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol. 1982;37:323-29.

- 24. Nitrini R, Caramelli P, Bottino CMC, Damasceno BP, Brucki SMD, Anghinah R. Diagnóstico de doença de Alzheimer no Brasil: avaliação cognitiva e funcional. Recomendações do Departamento Científico de Neurologia Cognitiva e do Envelhecimento da Academia Brasileira de Neurologia. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2005;63:713-9.

- 25. Camozzato AL, Kochhann R, Simeoni C, Konrath CA, Pedro Franz A, Carvalho A, Chaves ML. Reliability of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) for patients with Alzheimer's disease and their caregivers. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20:383-93.

- 26. Cassis SVA, Karnakis T, Moraes TA, Curiati JAE, Quadrante ACR, Magaldi RM. Correlation between burde non caregiver and clinical characteristics os patients with dementia. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2007;53(6):497-501.

- 27. Matsuda N. For the betterment of the family care for the aged with dementia. Kobe J Med Sci 2001;47:123-9.

- 28. Grossberg TG. Diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer's disease. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:3-7.

- 29. Matsumoto N, Ikeda M, Fukuhara R, Shinagawa S, Ishikawa T, Mori T, Toyota Y, Matsumoto T, Adachi H, Hirono N, Tanabe H. Caregiver burden associated with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in elderly people in the local community. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;23(4):219-24.

- 30. Bakker AB, Shaufeli WB, Demerouti E, Janssen PPM, Van Der Hulst R, Brouwer J. Using equity theory to examine the difference between burnout and depression. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2000;13:247-68.

- 31. Moscoso MA, Marques RCG, Ribeiz SRI, Santos L, Bezerra DM, Filho WJ, Nitrini R, Bottino CMC. Profile of caregivers of Alzheimer's disease patients attended at a reference center for cognitive disorders. Dement Neuropsychol. 2007;1(4):412-7.

Corresponding author:

Publication Dates

-

Publication in this collection

16 Jan 2013 -

Date of issue

Dec 2012

History

-

Received

28 Oct 2011 -

Accepted

02 Feb 2012